Abstract

Marked overlap between the HIV and injection drug use epidemics in St. Petersburg, Russia, puts many people in need of health services at risk for stigmatization based on both characteristics simultaneously. The current study examined the independent and interactive effects of internalized HIV and drug stigmas on health status and health service utilization among 383 people with HIV who inject drugs in St. Petersburg. Participants self-reported internalized HIV stigma, internalized drug stigma, health status (subjective rating and symptom count), health service utilization (HIV care and drug treatment), sociodemographic characteristics, and health/behavioral history. For both forms of internalized stigma, greater stigma was correlated with poorer health and lower likelihood of service utilization. HIV and drug stigmas interacted to predict symptom count, HIV care, and drug treatment such that individuals internalizing high levels of both stigmas were at elevated risk for experiencing poor health and less likely to access health services.

Keywords: Stigma, Injection drug use, HIV, Health, Health services, Russia

Introduction

Russia has one of the world’s largest populations of people who inject drugs, estimated at over 1.8 million [1], with 83,000 projected to be living in St. Petersburg alone [2]. HIV has been a rapidly growing epidemic in the St. Petersburg community of people who inject drugs throughout the first part of this century [3–6], with prevalence plateauing at approximately 60 % only in the past three to 4 years [7]. Understanding factors that contribute to declines in health status and combating barriers to health service utilization among people with HIV who inject drugs are important for maximizing the wellbeing of this group and potentially stemming transmission to others. This is especially true in St. Petersburg, where continuing HIV transmission among people who inject drugs is central to sustaining the epidemic and expanding its penetration into the general public [8].

Stigma has received increasing attention as a health risk factor and an obstacle to service utilization among people with HIV [9–13] and people who inject drugs [14–17]. Stigma refers to a personal trait or mark that serves as the basis for social devaluation and discrediting [18]. It occurs when identified human differences are deemed undesirable and lead to separation, status loss, and discrimination in a social, economic, and political power context [19]. Individuals who possess a stigmatized characteristic may not only perceive or anticipate negative treatment by other people, but may also come to endorse the stigma associated with that status themselves. Internalized stigma (“self-stigma”), which occurs when the negative attitudes and feelings associated with a socially devalued characteristic are adopted and self-applied by individuals who possess that characteristic, has been identified as a pathway through which societal stigma may impact health outcomes [9, 20].

Attitudinal studies in Russia have highlighted pervasive stigma directed toward both people with HIV [21–23] and people who inject drugs [24, 25] as well as the potential deterrent effect of HIV and drug stigmas on service utilization [12, 13, 24–26]. Fear of confidentiality being breached and anticipated harm to personal and professional relationships are among the most common barriers to care reported by people with HIV in St. Petersburg [12]. People who use drugs face similar social penalties and barriers to care, which are structurally reinforced: Access to drug treatment in Russia typically requires formal registration as a drug user and monitoring for 5 years following treatment, during which time quality of life can be significantly compromised by restrictions on employment, licensure to drive, and military service. Registration itself is perceived to mark people who use drugs as social outcasts and render them vulnerable to police harassment if confidentiality is breached [24]. Thus, both HIV and drug stigmas may interfere with health service utilization in Russia, causing deleterious health consequences for affected communities given the healthcare needs associated with HIV and injection drug use.

Despite the concurrence of HIV and drug use epidemics in Russia and in other regions throughout the world, limited research has examined internalized HIV and drug stigmas as coexisting or interactive influences on health status or health service utilization [27–29]. Consistent with the intersectionality perspective, which asserts that social statuses are interdependent and shape the meaning and experience of one another [30], multiple internalized stigmas have the potential to operate interactively, with one exacerbating or otherwise modifying the effect of another [28]. For example, Earnshaw and colleagues [28] examined the interaction of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma as related to depression among people with HIV who had a recent history of drug use (broadly defined) in New York City (United States). A significant interaction between the two forms of stigma was identified, indicating that internalized HIV stigma was only predictive of depression when it coexisted with high levels of internalized drug stigma. To our knowledge, the interaction of internalized HIV and drug stigmas as related to physical health status and health service utilization has yet to be explored. Clarifying the additive or interactive impact of these two stigmas on physical health status and health service utilization is critical to adequately assessing the nature and scope of stigma and to designing appropriately nuanced interventions to maximize health and treatment access for the many people with HIV who inject drugs.

The objective of the current study was to examine the relationships of internalized HIV and drug stigmas—independently and interactively—to physical health status (symptom count and subjective health rating) and health service utilization (regular HIV care and drug treatment) among people with HIV who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia. We hypothesized that internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma would both be negatively associated with health status and service utilization outcomes. Moreover, because of the added burden potentially posed by internalizing multiple stigmas and consistent with past findings of an interactive effect between internalized HIV and drug stigmas relative to mental health [28], we hypothesized that the relationship between internalized HIV stigma and health status/service utilization outcomes would be stronger among individuals higher in internalized drug stigma and weaker among individuals lower in internalized drug stigma (i.e., that internalized drug stigma would moderate the effects of internalized HIV stigma).

Methods

Participants and Procedure

Participants were recruited via respondent-driven sampling as part of a larger study on social factors affecting HIV prevalence and access to services among people who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia, and Kohtla-Järve, Estonia (see also [27, 31, 32]). Adults who reported injection drug use in the past 4 weeks were eligible to participate. The current analysis was restricted to participants who were HIV-positive (verified by rapid oral HIV testing) and living in St. Petersburg. Within the St. Petersburg sample, all measures were translated and administered in Russian during private face-to-face interviews in proximity to vans dispatched by a non-governmental agency to provide outreach services such as needle exchange, condom distribution, counseling, HIV and hepatitis C testing/counseling, and medical referrals to people who use drugs and other vulnerable populations. The interviews were conducted by three staff members of NGO-Stellit, all of whom had received at least master’s-level training in conducting social science research. Following the interviews, participants underwent rapid oral HIV testing and then received post-test counseling conducted by trained outreach staff. Data collection occurred between November 2012 and June 2013 within 7 of the 18 districts of St. Petersburg. Districts were initially identified by local service providers based on knowledge of existing drug user communities. Of those identified, two central, three peripheral, and two outlying districts were selected to be geographically representative of the metropolitan community. Participants were compensated for participation and recruitment with telephone gift cards worth $20 and $10, respectively, in US currency. All study procedures were approved by institutional review boards at Yale University and NGO-Stellit prior to inception.

Measures

Sociodemographic Characteristics

Participants reported sociodemographic characteristics, including age (years, computed based on reported birth year); gender (male or female); formal education completed (less than secondary education, secondary education, vocational education, any higher education); and financial status (comfortable/coping with present income, difficult to cope with present income, very difficult to cope with present income).1

Health/Behavioral History

Participants reported their frequency of injection drug use (number of days used) over the past 28 days. They also reported their age at the time that they first injected a drug for non-medical purposes, which was used to calculate time since first injection drug use (years), as well as the month and year that they were first told that they were HIV-positive, which was used to calculate time since HIV diagnosis (years). For descriptive purposes, sexual behavior was also examined in terms of intercourse with one or more partners of the same sex, other sex, both sexes, or neither sex (i.e., no intercourse) in the past 6 months.

Internalized Stigma

Internalized HIV stigma was measured with the six-item Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale [34]. Given that conceptualization of this scale was rooted in Goffman’s classic theory of social stigma [18], encompassing dimensions of stigma that are not exclusive to HIV/AIDS, six parallel items measuring internalized drug stigma were created for this study by replacing HIV status with drug user status. We intentionally used parallel items with identical response scales and scoring procedures to permit direct comparisons between the two measures. These items were field-tested in Russian during formative pilot work to ensure comprehensibility and internal consistency. The original items, which focus on status concealment and self-blame surrounding HIV-positive status, were particularly adaptable to drug user status given the similarity of drug user status as a potentially concealable stigmatized identity. Sample items include: “It is difficult to tell people about my HIV infection” (“It is difficult to tell people about being a drug user”) and “I sometimes feel worthless because I am HIV positive” (“I sometimes feel worthless because I am a drug user”). For both sets of items, participants rated their agreement using a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) as opposed to the dichotomous scale (agree vs. disagree) used in the original measure. Items were coded so that higher scores reflected higher internalized stigma and mean scores were calculated for both internalized HIV stigma (Cronbach’s α = 0.89) and internalized drug stigma (Cronbach’s α = 0.91).

Health Status

Participants provided a current subjective health rating based on the visual analog scale (VAS) of the EQ-5D-3L ([35, 36]; see also http://www.euroqol.org/). The EQ-5D-3L is a standardized measure of health status developed by an interdisciplinary research team (The EuroQol Group) for international use. The VAS is a single-item, thermometer-like scale ranging from 0 (worst health state you can imagine) to 100 (best health state you can imagine). The VAS has previously demonstrated sensitivity to CD4+ lymphocyte count and antiretroviral use among people with HIV [37, 38] and has been used as a standalone measure in public health research [39]. Symptom count was determined from the number of symptoms participants reported currently experiencing of the following: tiredness/fatigue, fever, chills, weight loss, nightly sweating, appetite loss, cough that lasted over 2 weeks, blood in sputum, chest pain, and swollen lymph nodes. This measure was developed by a panel of public health and infectious disease expert physicians who routinely treat people with HIV who use drugs; the measure was developed as part of a health survey conducted in several Eastern European countries by the Estonian National Institute for Health Development [40]. The measure was originally selected given the inclusion of Estonian participants in the larger study, and was also used with the Russian participants included in the substudy presented here to enable between-group comparisons.

Health Service Utilization

Participants reported whether or not they received regular HIV care, defined as visiting an HIV physician at least once per 6 months (i.e., the recommended timeframe in Russia for routine immunological monitoring of patients not on antiretroviral medication). They also indicated whether they received drug treatment (“drug abuse treatment/substitution treatment”) in the past 12 months. Both time frames comply with evidence-based guidelines suggesting researchers use a 1-year maximum recall period for self-reported health service utilization; although shorter recall periods (e.g., 3 or 6 months) are generally preferable, a 1-year period has been deemed appropriate for medical care that is rarely used and/or likely to be salient (such as drug treatment among our target population; [41]).

Analyses

Frequencies, means, standard deviations, and medians were calculated to describe the sample and measures of interest. Bivariate correlations were performed using Pearson correlation coefficients (also known as point-biserial correlation coefficients for continuous/dichotomous variable pairs or phi coefficients for dichotomous/dichotomous pairs). Linear regressions adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and financial status) and health/behavioral history (frequency of injection drug use, time since first injection drug use, and time since HIV diagnosis) were used to investigate main and interaction effects of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma on health status (subjective health rating and symptom count). Logistic regressions adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and health/behavioral history were performed to examine main and interaction effects of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma on health service utilization (regular HIV care and drug treatment). Internalized stigma variables and covariates were centered for all regression analyses. Initial models were tested without interaction terms to detect main effects; interaction terms were added in subsequent models. When significant interaction effects were identified, follow-up simple slopes analysis [42] was performed to probe the effect of internalized HIV stigma at high and low levels of internalized drug stigma. Because there are no established benchmark scores demarcating levels of stigma for the continuous measures of stigma employed, relatively high and low levels were defined as 1 standard deviation above and below the mean for simple slopes analysis as recommended [42]. Adjusted odds ratios (AORs) reported in the text are shown with 95 % confidence intervals in brackets.

Results

Sample Characteristics

Of the total sample of St. Petersburg participants (n = 811), 47.2 % (n = 383) were living with HIV and completed both internalized HIV and drug stigma measures. Frequencies pertaining to sociodemographic characteristics, health/behavioral history, health status, and health service utilization are presented in Table 1. Participants were predominantly male and ranged in age from 20 to 51 years (M = 32.42, SD = 4.20; Mdn = 32.0). Few had completed any higher education and most reported some degree of financial difficulty. Daily or near-daily injection drug use and longstanding use (initiation more than 10 years ago) were both commonly reported. Time since HIV diagnosis ranged from less than 1 year to 16 years (M = 5.51, SD = 3.42; Mdn = 5.0). Most participants reported intercourse with one or more partners of the other sex in the past 6 months, whereas same-sex intercourse was rarely indicated. Subjective health rating (on a 0–100 scale) ranged from 5 to 95 (M = 58.93, SD = 14.49; Mdn = 60.0) and symptom count (out of 10 possible symptoms) ranged from 0 to 9 (M = 2.60, SD = 2.38; Mdn = 2.0).2 Less than a third of participants reported receiving regular HIV care and about one in ten participants reported undergoing drug treatment in the past 12 months.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics of 383 people with HIV who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia

| Sociodemographics | Percentagea (n) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| ≤29 years | 25.8 % (99) |

| 30–39 years | 68.4 % (262) |

| ≥40 years | 5.7 % (22) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 20.9 % (80) |

| Male | 79.1 % (303) |

| Formal education completed | |

| Less than secondary education | 9.7 % (37) |

| Secondary education (through 11th grade) | 31.6 % (121) |

| Vocational education | 50.1 % (192) |

| Any higher education | 8.6 % (33) |

| Financial status (n = 380) | |

| Comfortable/coping with present income | 22.6 % (86) |

| Difficult to cope with present income | 63.4 % (241) |

| Very difficult to cope with present income | 13.9 % (53) |

| Health/behavioral history | |

| Frequency of injection drug use (past 28 days) | |

| 1–7 days | 5.7 % (22) |

| 8–14 days | 13.8 % (53) |

| 15–21 days | 26.9 % (103) |

| 22–28 days | 53.5 % (205) |

| Time since first injection drug use (n = 382) | |

| ≤5 years | 1.0 % (4) |

| 6–10 years | 18.0 % (69) |

| 11–15 years | 50.8 % (194) |

| ≥16 years | 30.1 % (115) |

| Time since HIV diagnosis (n = 376) | |

| < 1 year | 6.9 % (26) |

| 1–5 years | 47.6 % (179) |

| 6–10 years | 34.6 % (130) |

| 11+ years | 10.9 % (41) |

| Sexual behavior (past 6 months) | |

| Same-sex intercourse only | 0.0 % (0) |

| Other-sex intercourse only | 77.0 % (295) |

| Both same-sex and other-sex intercourse | 0.3 % (1) |

| No intercourse | 22.7 % (87) |

| Health status | |

| Subjective health rating (0–100; n = 382) | |

| 1–25 | 1.0 % (4) |

| 26–50 | 35.3 % (135) |

| 51–75 | 53.7 % (205) |

| 76–100 | 9.9 % (38) |

| Symptom countb (0–10; n = 382) | |

| 0 | 35.1 % (134) |

| 1–5 | 49.7 % (190) |

| 6–10 | 15.2 % (58) |

| Health service utilization | |

| Regular HIV care (1 + visits/6 months; n = 380) | 32.4 % (123) |

| Drug treatment (1 + times in past 12 months) | 11.2 % (43) |

Percentage reflects full sample (N = 383) unless otherwise noted

Number of current symptoms of the following: tiredness/fatigue, fever, chills, weight loss, nightly sweating, appetite loss, cough that lasted > 2 weeks, blood in sputum, chest pain, swollen lymph nodes

Bivariate Correlations

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics (mean, standard deviation, and median) and bivariate correlations for internalized stigma, health status, and health service utilization variables. Internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma were positively correlated with each other and were correlated with all outcomes in the expected direction: Higher internalized stigma was associated with poorer subjective health, a higher number of symptoms, not receiving regular HIV care, and not receiving drug treatment in the past 12 months.

Table 2.

Descriptive statistics and bivariate correlations for internalized stigma, health status, and health service utilization measures among people with HIV who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia

| Measure | N | M | SD | Mdn | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 Internalized HIV stigma | 383 | 3.45 | 0.99 | 3.50 | – | |||||

| 2 Internalized drug stigma | 383 | 3.37 | 1.01 | 3.67 | .53** | – | ||||

| 3 Subjective health rating | 382 | 58.93 | 14.49 | 60.00 | −.24** | −.34** | – | |||

| 4 Symptom count | 382 | 2.60 | 2.38 | 2.00 | .39** | .43** | −.51** | – | ||

| 5 Regular HIV care (1 + visits/6 months) | 380 | – | – | – | −.42** | −.36** | .42** | −.38** | – | |

| 6 Drug treatment (1 + times in past 12 months) | 383 | – | – | – | −.14** | −.13* | .01 | −.15** | .19** | – |

p < .05,

p < .01

Health Status Regression Analyses

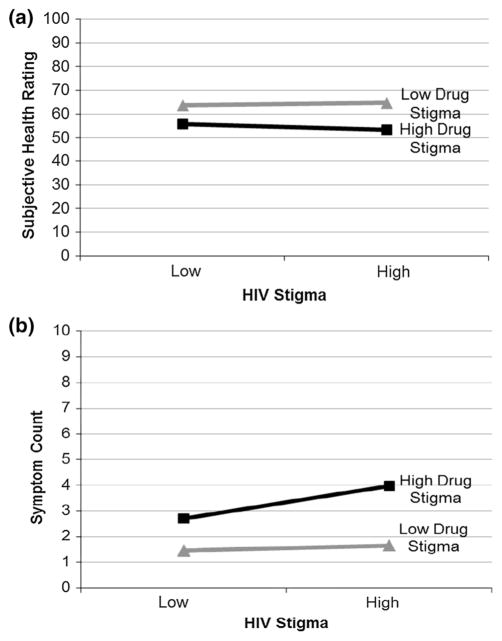

Linear regression analyses were conducted to examine main and interaction effects of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma on health status (subjective health rating and symptom count), adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and financial status) and health/behavioral history (frequency of injection drug use, time since first injection drug use, and time since HIV diagnosis). Results from the initial model predicting subjective health rating revealed no main effect of internalized HIV stigma, but a significant main effect of internalized drug stigma. When the interaction term was added to the model, no significant interaction effect was detected (see Table 3; Fig. 1a).

Table 3.

Linear regression models of main and interaction effects of internalized HIV and drug stigmas on health status among people with HIV who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia

| Variable | a. Subjective health rating (n = 371)

|

b. Symptom count (n = 371)

|

||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a

|

Model 2a

|

Model 1a

|

Model 2a

|

|||||||||

| b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | b | SE | p | |

| Internalized HIV stigma | −0.41 | 0.92 | .654 | −0.39 | 0.92 | .669 | 0.37 | 0.14 | .009 | 0.37 | 0.14 | .010 |

| Internalized drug stigma | −4.62 | 0.86 | <.001 | −4.77 | 0.67 | <.001 | 0.84 | 0.13 | <.001 | 0.89 | 0.13 | <.001 |

| Internalized HIV stigma × internalized drug stigma | −0.87 | 0.75 | .247 | 0.27 | 0.12 | .021 | ||||||

Models adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and financial status) and health/behavioral history (frequency of injection drug use, time since first injection drug use, and time since HIV diagnosis)

Fig. 1.

Internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma interaction models predicting subjective health rating (a non-significant interaction) and symptom count (b significant interaction), statistically adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and financial status) and social/behavioral history (frequency of injection drug use, time since first use, and time since HIV diagnosis). Stigma variables and covariates (dummy coded as needed) were mean-centered prior to analyses. High and low stigma values represent mean values ± 1 standard deviation

Results from the initial model predicting symptom count revealed significant main effects of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma. When the interaction term was added to the model, a significant interaction effect was detected (see Table 3). Simple slopes analysis indicated that HIV stigma was not significantly associated with symptom count at low levels (−1 SD) of internalized drug stigma, b = 0.09, SE = 0.19, p = .617, but was significantly positively associated with symptom count at high levels (+1 SD) of internalized drug stigma, b = 0.64, SE = 0.19, p = .001. Thus, higher internalized HIV stigma was related to more symptoms among people who experienced high (but not low) internalized drug stigma (see Fig. 1b).

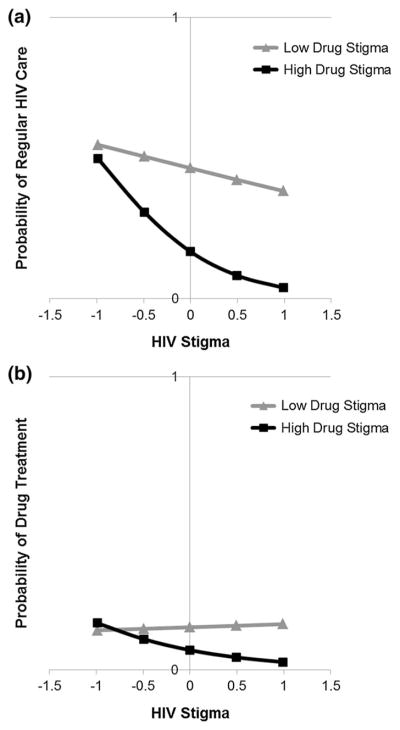

Health Service Utilization Regression Analyses

Logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine main and interaction effects of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma on health service utilization (regular HIV care and past-year drug treatment), adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and financial status) and health/behavioral history (frequency of injection drug use, time since first injection drug use, and time since HIV diagnosis). Results from the initial model predicting regular HIV care revealed significant main effects of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma. When the interaction term was added to the model, a significant interaction effect was detected (see Table 4). Simple slopes analysis indicated that internalized HIV stigma was not significantly associated with regular HIV care at low levels (−1 SD) of internalized drug stigma, b = −0.34, SE = 0.21, AOR = 0.71 [0.48, 1.07], p = .104, but was significantly negatively associated with regular HIV care at high levels (+1 SD) of internalized drug stigma, b = −1.62, SE = 0.30, AOR = 0.20 [0.11, 0.36], p <.001. Thus, higher internalized HIV stigma was related to a lower likelihood of receiving regular HIV care among people who also experienced high (but not low) internalized drug stigma (see Fig. 2a).

Table 4.

Logistic regression models of main and interaction effects of internalized HIV and drug stigmas on health service utilization among people with HIV who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia

| Variable | a. Regular HIV Care (n = 369)

|

b. Drug Treatment (n = 372)

|

||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1a

|

Model 2a

|

Model 1a

|

Model 2a

|

|||||||||||||||||

| b | SE | AOR | [95% CI] | p | b | SE | AOR | [95% CI] | p | b | SE | AOR | [95% CI] | p | b | SE | AOR | [95% CI] | p | |

| Internalized HIV stigma | −0.83 | 0.17 | 0.44 | [0.31, 0.61] | <.001 | −0.98 | 0.19 | 0.38 | [0.26, 0.54] | <.001 | −0.37 | 0.22 | 0.69 | [0.45, 1.05] | .086 | −0.46 | 0.21 | 0.63 | [0.41, 0.96] | .032 |

| Internalized drug stigma | −0.47 | 0.16 | 0.63 | [0.46, 0.85] | .002 | −0.73 | 0.18 | 0.48 | [0.34, 0.67] | <.001 | −0.25 | 0.21 | 0.78 | [0.52, 1.18] | .246 | −0.42 | 0.22 | 0.66 | [0.42, 1.01] | .058 |

| Internalized HIV stigma × internalized drug stigma | −0.64 | 0.17 | 0.53 | [0.38, 0.75] | <.001 | −0.50 | 0.20 | 0.61 | [0.41, 0.90] | .012 | ||||||||||

AOR adjusted odds ratio, CI confidence interval

Models adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and financial status) and health/behavioral history (frequency of injection drug use, time since first injection drug use, and time since HIV diagnosis)

Fig. 2.

Estimated probabilities of regular HIV care (a significant interaction) and past-year drug treatment (b significant interaction) based on internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma interaction models, statistically adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics (age, gender, education, and financial status) and social/behavioral history (frequency of injection drug use, time since first use, and time since HIV diagnosis). Stigma variables and covariates (dummy coded as needed) were mean-centered prior to analyses. High and low drug stigma values represent mean value ± 1 standard deviation

Results from the initial model predicting drug treatment over the past 12 months revealed non-significant main effects for both internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma. When the interaction term was added to the model, a significant interaction effect was detected (see Table 4). Simple slopes analysis indicated that internalized HIV stigma was not significantly associated with drug treatment at low levels (−1 SD) of internalized drug stigma, b = 0.04, SE = 0.26, AOR = 1.05 [0.62, 1.75], p = .868, but was significantly negatively associated with drug treatment at high levels (+1 SD) of internalized drug stigma, b = −0.97, SE = 0.32, AOR = 0.38 [0.20, 0.72], p = .003. Thus, higher internalized HIV stigma was related to a lower likelihood of receiving drug treatment in the past 12 months among people who also experienced high (but not low) internalized drug stigma (see Fig. 2b).

Discussion

Stemming the spread of HIV among people who inject drugs in Russia and maximizing the health status and health service utilization of those who are already infected necessitate understanding barriers to care at multiple levels. Whereas Russian health policies such as mandatory drug use registration and prohibition of opioid substitution therapy may reflect and reinforce stigma at structural and social levels, our findings suggest that internalization of negative social attitudes can also adversely impact health at the individual level. Internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma were negatively associated with health status and health service utilization among people with HIV who use drugs in St. Petersburg: At the bivariate level, both forms of internalized stigma were associated with poorer self-rated health, higher symptom count, lower likelihood of receiving regular HIV care, and lower likelihood of receiving drug treatment within the past year. Moreover, an interaction effect between internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma was evident for three of four outcomes, such that high internalized HIV stigma was more strongly related to symptom count, HIV care, and drug treatment at high vs. low levels of internalized drug stigma.

Our findings support and extend past research documenting a link between the interaction of internalized HIV and drug stigmas and adverse health outcomes in two ways. First, we demonstrated the interactive effects in a different domain of health. Whereas Earnshaw and colleagues [28] focused on the interaction between internalized HIV and drug stigmas relative to mental health status,3 we examined these potentially interacting stigmas relative to physical health status and health service utilization. Similar to Earnshaw and colleagues’ [28] finding of a stronger positive association between internalized HIV stigma and mental health symptoms at high vs. low levels of internalized drug stigma, we found that the relationships between internalized HIV stigma and physical health symptoms, regular HIV care, and drug treatment were stronger at high levels of internalized drug stigma.

Second, we demonstrated the potential robustness of the interactive effects of internalized HIV and drug stigmas on health by exploring these effects within a very different cultural context than did Earnshaw and colleagues [28]. Russia and the US differ in the intensity of stigma associated with HIV and drug use, in medical systems, and in their programmatic approaches to addressing HIV and drug use [22, 24, 45–47]. However, despite cultural differences between our Russian sample and Earnshaw and colleagues’ US-based sample, a similar pattern of relationships emerged between internalized HIV and drug stigmas and health. Additional research is needed to determine whether these interactive effects of internalized HIV and drug stigmas on health extend to other cultural contexts; such research could also help to identify factors that moderate the nature or strength of these interactive effects.

Our findings are particularly alarming given the social distribution of the HIV epidemic within and beyond Russia. Worldwide, HIV disproportionately infects groups that are already socially marginalized, including not only people who use drugs, but also people who engage in sex work, men who have sex with men, and transgender women [48, 49]. Consequently, many people with HIV are at risk for internalizing multiple forms of stigma, which our findings suggest could interfere with their engagement with medical care and related support services. Beyond the direct impact to the individual, HIV infection that is not medically managed can also increase the risk of transmission to an individual’s sex and drug use partners.

That internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma were not simply additive, but interactive in their relationship to health status and service utilization outcomes highlights the enhanced risk potentially faced by people living in Russia who internalize both forms of stigma. Further research exploring the implications of other forms of internalized stigma, such as internalized sexism and heterosexism, and their interactive effects on the health status and healthcare of people with HIV who inject drugs is needed to determine whether the observed results are applicable to other stigma combinations.

Examining additive and interactive effects of different dimensions of stigma—including internalized stigma, anticipated stigma (stigma consciousness), and enacted stigma (discrimination experiences)—could also provide a fuller picture of the impact of stigma on health status and health service utilization among people with HIV who inject drugs and other marginalized groups. US-based theoretical and empirical work has suggested that these various dimensions of stigma may differentially impact health and health service utilization among people with HIV or other stigmatized conditions [20, 50, 51]. In other research based on the same Russian sample of people with HIV who inject drugs as described in the current study, we found that internalized stigma and anticipated stigma exerted unique effects when considered simultaneously in models predicting depression and symptom count, whereas only internalized stigma exerted a unique effect relative to other health status and health service utilization outcomes tested [27]. When parallel models were explored with our Estonian sample of people with HIV who inject drugs, no additive effects were found and neither anticipated nor internalized stigma were independent predictors for most outcomes examined [27]. These different patterns of effects in Russian vs. Estonian samples underscore the importance of cultural context and the need to explore the independent and interactive effects of internalized HIV and drug stigmas on health in other geographic locations.

In addition to using statistical interactions to probe stigma intersections, methodological approaches that consider multiple stigmatized identities simultaneously and assess the unique, “blended” forms of stereotypes and discrimination that they may evoke could be useful. For instance, researchers have identified unique stereotypes that Black women confront due to their race and gender in combination [52, 53] and have suggested that Black women encounter “racialized sexual harassment” or “gendered racism” that is distinct from common conceptions of either racism or sexism alone [54, 55]. Similarly, people with HIV who use drugs may confront and internalize stereotypes and discrimination that are specific to this particular combination of social statuses, and development and utilization of measures that are sensitive to this experience could yield unique insights relative to health status and health service utilization. These quantitative approaches could be complemented by qualitative methods.

Future research is also warranted to understand the implications of identity characteristics for the observed findings. Previous theoretical and empirical work has posited that characteristics of a stigmatized identity—such as its prominence or centrality to self-concept—may moderate the relationship between internalized stigma and psychological distress [56–59]. Among people with concealable stigmatized identities (e.g., drug use, mental illness, experience of violence/assault), internalized stigma about a given identity has been found to be particularly distressing if that identity is highly central to a person’s self-definition [57]. Although findings have been mixed regarding the modifying effect of identity centrality on the relationship between stigma and (di)stress for non-concealable stigmatized identities (e.g., race [58, 59]), people with HIV who use drugs are generally able to conceal both identities [60], and thus centrality of one or both may exacerbate the negative consequences of internalized stigma on health observed in the current study.

Just as stigma manifests at structural, interpersonal, and individual levels, interventions aimed at combating stigma and its potential detrimental impact on health status and health service utilization in Russia can be implemented at multiple levels. Structurally, health policy reform that supports harm reduction services (e.g., needle exchange) and low-threshold access to HIV care in Russia may diminish negative messaging perceived and subsequently internalized, or buffer its impact on health status and health service utilization. In addition, less negative media portrayals of people with HIV and people who use drugs—and people who are members of both groups—may help to mitigate felt and internalized stigma among people with HIV who inject drugs [60].

Implementation of stigma reduction efforts specifically within healthcare settings may also improve medical service utilization among people with HIV who use drugs in Russia. Active outreach that encourages engagement in care ought to be enacted to connect these individuals to the HIV and drug treatment services they need to maximize their health and, potentially, protect that of their drug-using and sexual partners. Previous qualitative research with people with HIV in St. Petersburg has underscored the importance of perceived quality of medical staff/services and trust in one’s doctor as determinants of health service utilization [12]. Strengthening protocols to protect patients’ private health information within clinical care settings, communicating the value placed on such confidentiality to patients, and supporting patient–provider relationship-building over time through continuity of care may help to reduce the fears of confidentiality being breached and distrust of doctors commonly expressed as barriers to care by socially marginalized groups in Russia [12, 13]. Clinical training that promotes non-judgmental, patient-centered care and sensitizes clinicians and other staff members to the unique needs of people with HIV who inject drugs may promote retention once a relationship within the healthcare system has been established. In both medical and mental health settings, training on stigma and stigma reduction may be beneficial for all members of the care team.

Clinicians should be taught to consider the implications of social stress associated with multiple marginalized statuses in relation to the client’s presenting problems, including the risks that exist beyond the independent effects of those statuses, as indicated by our findings. The concept of “comorbidity” commonly applied in diagnostic models can be applied when considering an individual’s internal experience of stigma, in that two or more forms of internalized stigma can be co-occurring afflictions and may overlap and modify one another. Ultimately, this internal experience has implications for an individual’s health and behavior, and consideration of only one form of stigma will yield an incomplete case conceptualization and inadequate treatment plan. Thus, just as a clinician would assess for comorbidities when addressing a health concern, he or she could probe for stigma experienced on multiple bases, including those not immediately obvious from the client’s physical presentation or medical history, such as sexual orientation. Although thoroughly assessing and addressing multiple forms of stigma may not be feasible for a busy medical practitioner, other clinical staff or partnering mental health professionals could take the lead on this; the St. Petersburg AIDS Center routinely includes mental health professionals as part of the care team.

At the interpersonal level, previous research has indicated that perceived support from family, friends, and others living with HIV can facilitate engagement in care among people with HIV in St. Petersburg [12]. Thus, encouraging newly diagnosed individuals to selectively disclose their status to trusted others in their social network and/or providing access to anonymous sources of support (e.g., online forums for people with HIV) could be beneficial.

At the individual level, strategies designed to diminish the impact of internalized stigma on health and health service utilization ought to be integrated within mental health services and tailored according to stigma comorbidities. Acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT), an approach that teaches individuals to be mindful of their negative thoughts and feelings and to modify the function of those thoughts and feelings (i.e., their impact on behavior), has demonstrated preliminary success in reducing internalized stigma and shame, improving psychosocial wellbeing [61], and lowering drug use [62] among people who use drugs. This approach could be adapted and prove beneficial for people who use drugs and are also living with HIV. Additional research is needed to understand the magnitude and impact of both consciously recognized (explicit) and unconsciously endorsed (implicit) dimensions of internalized stigma within this group, as both could independently and adversely affect wellbeing [63] and may demand an adapted or intensified approach to therapy.

Opportunities for implementation of the recommended stigma reduction techniques in St. Petersburg may emerge as funding and research/community collaborations continue to develop. The St. Petersburg AIDS Center, which has been tasked with providing HIV care free of charge to the city’s residents, has been responsive to the identified demand for improved and expanded HIV services. For example, a recent grant from American International Health Alliance supported the formation of a partnership between the AIDS Center and Yale University that led to the establishment of the Baltic AIDS Training and Education Center—St. Petersburg and the creation of six decentralized clinics to make it easier for patients to access HIV treatment (www.aiha.com/en/WhatWeDo/HIV-AIDS_RusTCS.asp; [64]). Recognizing the complex circumstances and treatment needs of the patients that it serves and the community members it aims to engage in the future, the AIDS Center has also integrated psychological and substance abuse counseling into the menu of services it offers. Advances such as these yield optimism for continued improvement in HIV health service delivery in St. Petersburg and evolving policies and practices that are sensitive to the challenges faced by people with HIV who use drugs on account of their multiply marginalized status.

Findings of the current study should be interpreted in light of the following limitations. First, data are cross-sectional and therefore causality cannot be inferred. Thus, while we have discussed internalized stigma as a factor contributing to health status and health service utilization, it is also possible that these “outcomes” contribute to internalized stigma or that other factors contribute to both. For example, experiencing symptoms related to either HIV or drug use may exacerbate negative sentiments associated with that condition, thereby enhancing internalized stigma. Second, we examined only two forms of stigma, HIV and drug use, though participants in our sample may have internalized other forms of stigma as well that enhanced their vulnerability to negative health and health service utilization outcomes, such as stigma based on their socioeconomic status or gender. Although we adjusted for sociodemographic characteristics in our analyses, inclusion of stigma measures specific to these alternate statuses (or combinations thereof) will be important for future research on stigma and health status/service utilization. Third, the internalized drug stigma and symptom count measures administered in this study have not been previously validated; thus, caution should be exercised in interpreting associated results. Fourth, as health status and health service utilization were measured via self-report, the accuracy of this information is vulnerable to errors in recall and response bias. Finally, although the nature of the interaction between HIV and drug stigmas relative to health status/service utilization outcomes was generally consistent with the nature of that interaction relative to mental health in a New York City-based study [28], we observed some differences in HIV and drug stigma main effects on health status/service utilization relative to our Estonian sample [27]. Thus, generalizability of the additive and interactive effects that we identified here to other cultural contexts and across health status/service utilization outcomes should not be assumed. For example, given the similar availability of low-threshold HIV care and harm reduction services in New York City and Estonia, HIV and drug stigmas may have a lesser impact on health service utilization in New York City (as was found in Estonia) than was observed in Russia. More research on people with HIV who use drugs is needed to establish overarching patterns and understand cultural nuances.

Results of this study demonstrate the relevance of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma to the health status and healthcare of people with HIV who use drugs and highlight the detrimental impact of their simultaneous occurrence. Researchers and clinicians should be cognizant of the interactive effects of stigma potentially faced by other multiply marginalized groups and tailor study designs and interventions to be sensitive to this complexity.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Award Number R01-DA029888 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) and Award Number P30-MH062294 from the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH). Sarah K. Calabrese was supported by Award Numbers K01-MH103080 and T32-MH020031 from the NIMH. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIDA, NIMH, or the National Institutes of Health. The authors are grateful to participants for their generous contribution to the study.

Footnotes

For financial status, we assessed perceived economic strain rather than an objective indicator such as annual income because participants reported diverse living situations and levels of financial independence. Additionally, previous research has suggested that subjective measures of socioeconomic status may predict self-rated health more strongly than objective measures [33].

For reference, we also calculated descriptive health characteristics among HIV-negative people who inject drugs from our larger Russian sample: Subjective health rating (on a 0–100 scale) ranged from 20 to 100 (M = 69.21, SD = 14.33; Mdn = 70.0; n = 365) and symptom count (out of 10 possible symptoms) ranged from 0 to 8 (M = .95, SD = 1.75; Mdn = 0.0; n = 364).

Our study was not designed to replicate the findings of Earnshaw et al. [28], so it did not include the same measure of mental health status [43]. We did, however, perform exploratory linear regression analyses of main and interaction effects of internalized HIV stigma and internalized drug stigma on mental health status using an alternate measure [44]. Adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics and health/behavioral history, main effects of both internalized HIV stigma, b = 0.55, SE = 0.27, p = .045, and internalized drug stigma, b = 0.55, SE = 0.26, p = .032 emerged, linking both stigmas to poorer mental health, but no significant interaction effect was detected when the interaction term was added to the model, b = 0.28, SE = 0.22, p = .218.

References

- 1.Mathers BM, Degenhardt L, Phillips B, Wiessing L, Hickman M, Strathdee SA, et al. Global epidemiology of injecting drug use and HIV among people who inject drugs: a systematic review. Lancet. 2008;372(9651):1733–45. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61311-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heimer R, White E. Estimation of the number of injection drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;109(1–3):79–83. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Niccolai LM, Verevochkin SV, Toussova OV, White E, Barbour R, Kozlov AP, et al. Estimates of HIV incidence among drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia: continued growth of a rapidly expanding epidemic. Eur J Pub Health. 2011;21(5):613–9. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckq115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Niccolai LM, Toussova OV, Verevochkin SV, Barbour R, Heimer R, Kozlov AP. High HIV prevalence, suboptimal HIV testing, and low knowledge of HIV-positive serostatus among injection drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Behav. 2010;14(4):932–41. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9469-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Abdala N, Carney JM, Durante AJ, Klimov N, Ostrovski D, Somlai AM, et al. Estimating the prevalence of syringe-borne and sexually transmitted diseases among injection drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. Int J STD AIDS. 2003;14:697–703. doi: 10.1258/095646203322387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaboltas AV, Toussova OV, Hoffman IF, Heimer R, Verevochkin SV, Ryder RW, et al. HIV prevalence, sociodemographic and behavioral correlates and recruitment methods among injection drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia. JAIDS. 2006;41:657–63. doi: 10.1097/01.qai.0000220166.56866.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eritsyan K, Heimer R, Barbour R, Odinokova V, White E, Rusakova MM, et al. Individual-level, network-level and city-level factors associated with HIV prevalence among people who inject drugs in eight Russian cities: A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2013;3(6):e002645. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2013-002645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mills HL, White E, Colijn C, Vickerman P, Heimer R. HIV transmission from drug injectors to partners who do not inject, and beyond: Modelling the potential for a generalized heterosexual epidemic in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2013;133(1):242–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Earnshaw VA, Bogart LM, Dovidio JF, Williams DR. Stigma and racial/ethnic HIV disparities: moving toward resilience. Am Psychol. 2013;68(4):225–36. doi: 10.1037/a0032705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Logie C, Gadalla TM. Meta-analysis of health and demographic correlates of stigma towards people living with HIV. AIDS Care. 2009;21(6):742–53. doi: 10.1080/09540120802511877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolitski RJ, Pals SL, Kidder DP, Courtenay-Quirk C, Holtgrave DR. The effects of HIV stigma on health, disclosure of HIV status, and risk behavior of homeless and unstably housed persons living with HIV. AIDS Behav. 2009;13(6):1222–32. doi: 10.1007/s10461-008-9455-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kelly J, Amirkhanian Y, Yakovlev A, Musatov V, Meylakhs A, Kuznetsova A, et al. Stigma reduces and social support increases engagement in medical care among persons with HIV infection in St. Petersburg, Russia. J Int AIDS Soc. 2014;17(4 Suppl 3):19618. doi: 10.7448/IAS.17.4.19618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King EJ, Maman S, Bowling JM, Moracco KE, Dudina V. The influence of stigma and discrimination on female sex workers’ access to HIV services in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(8):2597–603. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0447-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lang K, Neil J, Wright J, Dell CA, Berenbaum S, El-Aneed A. Qualitative investigation of barriers to accessing care by people who inject drugs in Saskatoon, Canada: perspectives of service providers. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2013;8:35. doi: 10.1186/1747-597X-8-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simmonds L, Coomber R. Injecting drug users: a stigmatised and stigmatising population. Int J Drug Policy. 2009;20(2):121–30. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lang K, El-Aneed A, Berenbaum S, Dell CA, Wright J, McKay ZT. Qualitative assessment of crisis services among persons using injection drugs in the city of Saskatoon. J Subst Use. 2013;18(1):3–11. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Latkin C, Srikrishnan AK, Yang C, Johnson S, Solomon SS, Kumar S, et al. The relationship between drug use stigma and HIV injection risk behaviors among injection drug users in Chennai, India. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2010;110(3):221–7. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goffman E. Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster, Inc; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Link BG, Phelan JC. Conceptualizing stigma. Ann Rev Sociol. 2001;27:363–85. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 2009;13:1160–77. doi: 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balabanova Y, Coker R, Atun RA, Drobniewski F. Stigma and HIV infection in Russia. AIDS Care. 2006;18(7):846–52. doi: 10.1080/09540120600643641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.McCrae RR, Costa PT, Martin TA, Oryol VE, Senin IG, O’Cleirigh C. Personality correlates of HIV stigmatization in Russia and the United States. J Res Personal. 2007;41(1):190–6. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lioznov D, Nikolaenko S, editors. HIV-related stigma among intravenous drug users in St. Petersburg, Russia; 6th International AIDS Society Conference on HIV Pathogenesis, Treatment and Prevention; Rome, Italy. 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bobrova N, Rhodes T, Power R, Alcorn R, Neifeld E, Krasiukov N, et al. Barriers to accessing drug treatment in Russia: a qualitative study among injecting drug users in two cities. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82(Suppl 1):S57–63. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(06)80010-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rhodes T, Platt L, Sarang A, Vlasov A, Mikhailova L, Monaghan G. Street policing, injecting drug use and harm reduction in a Russian city: a qualitative study of police perspectives. J Urban Health. 2006;83(5):911–25. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9085-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tkatchenko-Schmidt E, Renton A, Gevorgyan R, Davydenko L, Atun R. Prevention of HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users in Russia: opportunities and barriers to scaling-up of harm reduction programmes. Health Policy. 2008;85(2):162–71. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burke SE, Calabrese SK, Dovidio JF, Levina OS, Uusküla A, Niccolai LM, et al. A tale of two cities: stigma and health outcomes among people with HIV who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia and Kohtla-Järve, Estonia. Soc Sci Med. 2015;130:154–61. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Cunningham CO, Copenhaver MM. Intersectionality of internalized HIV stigma and internalized substance use stigma: implications for depressive symptoms. J Health Psychol. 2013 doi: 10.1177/1359105313507964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li X, Wang H, He G, Fennie K, Williams AB. Shadow on my heart: a culturally grounded concept of HIV stigma among chinese injection drug users. J Assoc Nurses AIDS Care. 2012;23(1):52–62. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am Psychol. 2009;64(3):170–80. doi: 10.1037/a0014564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cepeda JA, Niccolai LM, Lyubmova A, Kershaw T, Levina OS, Heimer R. High-risk behaviors after icarceration among people who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;147:196–202. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cepeda JA, Vetrova MV, Liubimova AI, Levina OS, Heimer R, Niccolai LM. Community reentry challenges after release from prison among people who inject drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia. Int J Prison Health. doi: 10.1108/IJPH-03-2015-0007. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Singh-Manoux A, Marmot MG, Adler NE. Does subjective social status predict health and change in health status better than objective status? Psychosom Med. 2005;67(6):855–61. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188434.52941.a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):87–93. doi: 10.1080/09540120802032627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brooks RA. EuroQol: the current state of play. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 1996;37(1):53–72. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(96)00822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.The EuroQol Group. EuroQol-a new facility for the measurement of health-related quality of life. Health Policy. 1990;16(3):199–208. doi: 10.1016/0168-8510(90)90421-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathews WC, May S. EuroQol (EQ-5D) measure of quality of life predicts mortality, emergency department utilization, and hospital discharge rates in HIV-infected adults under care. Health Qual life Outcomes. 2007;5:5. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-5-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nglazi MD, West SJ, Dave JA, Levitt NS, Lambert EV. Quality of life in individuals living with HIV/AIDS attending a public sector antiretroviral service in Cape Town, South Africa. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:676. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-676. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Woodhall S, Eriksson T, Nykanen AM, Huhtala H, Rissanen P, Apter D, et al. Impact of HPV vaccination on young women’s quality of life—a five year follow-up study. Eur J Contracept Reprod Health Care. 2011;16(1):3–8. doi: 10.3109/13625187.2010.536921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karnite A, Uusküla A, Luizov A, Rusev A, Talu A, Upite E, et al. Assessment on HIV and TB knowledge and the barriers related to access to care among vulnerable groups: Report on a cross-sectional study among injecting drug users. Estonia. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhandari A, Wagner T. Self-reported utilization of health care services: improving measurement and accuracy. Med Care Res Rev. 2006;63(2):217–35. doi: 10.1177/1077558705285298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Irwin M, Artin KH, Oxman MN. Screening for depression in the older adult: criterion validity of the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(15):1701–4. doi: 10.1001/archinte.159.15.1701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Berwick DM, Murphy JM, Goldman PA, Ware JE, Jr, Barsky AJ, Weinstein MC. Performance of a five-item mental health screening test. Med Care. 1991;29(2):169–76. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Burki T. Russia’s drug policy fuels infectious disease epidemics. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(4):275–6. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(12)70072-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sullivan LE, Metzger DS, Fudala PJ, Fiellin D. Decreasing international HIV transmission: the role of expanding access to opioid agonist therapies for injection drug users. Addiction. 2005;100:150–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2004.00963.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.U.S. Office of National AIDS Policy. [Accessed 23 May 2015];National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. 2010 Available at: https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/uploads/NHAS.pdf.

- 48.Baral SD, Poteat T, Strömdahl S, Wirtz AL, Guadamuz TE, Beyrer C. Worldwide burden of HIV in transgender women: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(3):214–22. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.UNAIDS. Global report: UNAIDS report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Earnshaw VA, Quinn DM. The impact of stigma in healthcare on people living with chronic illnesses. J Health Psychol. 2012;17(2):157–68. doi: 10.1177/1359105311414952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(5):1785–95. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ghavami N, Peplau LA. An intersectional analysis of gender and ethnic stereotypes: testing three hypotheses. Psychol Women Q. 2013;37(1):113–27. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stephens DP, Phillips LD. Freaks, gold diggers, divas, and dykes: the sociohistorical development of adolescent African American women’s sexual scripts. Sex Cult. 2003;7:3–49. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buchanan NT, Ormerod AJ. Racialized sexual harassment in the lives of African American women. Women Therapy. 2002;25(3–4):107–24. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carr ER, Szymanski DM, Taha F, West LM, Kaslow NJ. Understanding the link between multiple oppressions and depression among African American women. Psychol Women Q. 2014;38(2):233–45. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–97. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Quinn DM, Williams MK, Quintana F, Gaskins JL, Overstreet NM, Pishori A, et al. Examining effects of anticipated stigma, centrality, salience, internalization, and outness on psychological distress for people with concealable stigmatized identities. PLoS One. 2014;9(5):e96977. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0096977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sellers RM, Caldwell CH, Schmeelk-Cone KH, Zimmerman MA. Racial identity, racial discrimination, perceived stress, and psychological distress among African American young adults. J Health Soc Behav. 2003;44(3):302–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Burrow AL, Ong AD. Racial identity as a moderator of daily exposure and reactivity to racial discrimination. Self Identity. 2010;9(4):383–402. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Quinn DM, Earnshaw VA. Understanding concealable stigmatized identities: the role of identity in psychological, physical, and behavioral outcomes. Soc Issues Policy Rev. 2011;5(1):160–90. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Luoma JB, Kohlenberg BS, Hayes SC, Bunting K, Rye AK. Reducing self-stigma in substance abuse through acceptance and commitment therapy: model, manual development, and pilot outcomes. Addict Res Theory. 2008;16(2):149–65. doi: 10.1080/16066350701850295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hayes SC, Wilson KG, Gifford EV, Bissett R, Piasecki M, Batten SV, et al. A preliminary trial of twelve-step facilitation and acceptance and commitment therapy with polysubstance-abusing methadone-maintained opiate addicts. Behav Therapy. 2004;35:667–88. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rusch N, Corrigan PW, Todd AR, Bodenhausen GV. Implicit self-stigma in people with mental illness. J Nerv Mental Dis. 2010;198(2):150–3. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181cc43b5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Suvorova AV, Belyakov AN, Makhamatova AF, Ustinov AS, Levina OS, Tulupyey AL, et al. Comparison of satisfaction with care between two different models of HIV care delivery in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Care. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2015.1054337. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]