Abstract

Background

Blood stream infections are major cause of morbidity and mortality in children in developing countries. The emerging of causative agents and resistance to various antimicrobial agents are increased from time to time. The main aim of this study was to determine the bacterial agents and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns among children suspected of having septicemia.

Methods

A cross sectional study involved about 201 pediatric patients (≤ 12 years) was conducted from October 2011 to February 2012 at pediatric units of TikurAnbessa Specialized Hospital and Yekatit 12 Hospital. Standard procedure was followed for blood sample collection, isolate identifications and antimicrobial susceptibility testing.

Results

Among 201 study subjects 110 (54.7%) were males. Majority 147 (73.1%) of them were neonates (≤ 28 days). The mean length of hospital stay before sampling was 4.29 days. Out of the 201 tested blood samples, blood cultures were positive in 56 (27.9%).Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria constituted 29(51.8%) and 26(46.4%), respectively. The most frequent pathogen found was Staphylococcus aureus 13 (23.2%), followed by Serratia marcescens 12(21.4%), CoNS 11(19.6%), klebsiella spp 9(16%) and Salmonella spp 3(5.4%). Majority of bacterial isolates showed high resistance to Ampicillin, Penicillin, Co-trimoxazole, Gentamicin and Tetracycline which commonly used in the study area.

Conclusion

Majority of the isolates were multidrug resistant. These higher percentages of multi-drug resistant emerged isolates urge us to take infection prevention measures and to conduct other large studies for appropriate empiric antibiotic choice.

Keywords: Addis Ababa, Antimicrobial susceptibility, Blood culture, Children, Septicemia

1.Background

Sepsis is a systemic illness caused by microbial invasion of normally sterile parts of the body. It is a serious, life-threatening infection that gets worse very quickly due to the spread of microorganisms and their toxins in the blood. It can arise from infections throughout the body, including infections in the lungs, abdomen, and urinary tract [1, 2]. Blood stream infections are very common in the pediatric age groups which are one of the common causes of morbidity and mortality in neonates and children [3]. Infants and children are among the most vulnerable population groups to contract illnesses because of their weak immune barrier. Illnesses associated with bloodstream infections range from self-limiting infections to life threatening sepsis, multiple organ failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation that requires rapid and aggressive antimicrobial treatment. The incidence of bacteremia in children varies widely. About 20–50% positivity has been reported by many studies. In general sepsis is a medical emergency that requires timely detection and identification of blood borne pathogens with urgent rational antibiotics therapy [4, 5, 6, 7].

In the management of sepsis in pediatric age group, empirical antibiotic therapy should be unit-specific and determined by the prevalent spectrum of etiological agents and their antibiotic sensitivity pattern [8, 9].The early signs and symptoms of septicemia can vary from site to site[10]. It is therefore important to carry out investigations to confirm pediatric sepsis for timely detection and identification of blood stream pathogens.

Blood is normally a sterile site, a blood culture have a high positive predictive value and is a key component for an accurate diagnosis of blood stream infections and an appropriate choice of antibiotics that is important for subsequent management of septic newborns and children [11]. For selecting empiric therapy, many factors should be considered including the kind of pathogen that is most probably the cause of the infection according to age, gender, risk factors and antibiotic susceptibility pattern. Thus, rapid detection and identification of clinically relevant microorganisms in blood cultures is very essential and determination of antimicrobial susceptibility pattern for rapid administration of antimicrobial therapy has been shown to reduce the morbidity and mortality associated with blood stream infections. Therefore, blood culture remains the mainstay of investigation of definitive diagnosis and management of blood stream infection in infants and children, despite recent advances in the molecular diagnosis of bacterial sepsis [12, 13, 14]. Antibiotic sensitivity pattern to common pathogen has been changing from day to day and it is important to have latest information as this is essential in guiding local empirical choice of antibiotics. Hence, the result of the present study provides knowledge on the etiologic agents of pediatric septicemia and its rational use of antibiotics.

2. Methods

Study design and data collection

A hospital based cross-sectional study was conducted at pediatric units of Tikur Anbessa Specialized University Hospital and Yekatit-12 Hospital in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia from October 2011 to February 2012. Sample size was calculated based on previous prevalence study among children suspected of septicemia in Addis Ababa [15, 16]. Accordingly about 201 children (≤ 12 years) who admitted to either of the pediatric ward or examined at pediatric emergency OPD for sepsis were recruited in this study. A predefined data collection tool was used to extract all socio-demographic data and other relevant information such as weight, previous antibacterial therapy, and application of indwelling medical device, hospitalization period, co-morbidities, outcome, clinical signs and symptoms of sepsis for each patient. Appropriate treatment was initiated after collection of blood and admitted children were followed until discharge or death.

Blood culture and antibacterial sensitivity

Using aseptic technique about 2–5 ml of blood was obtained after cleaning the venous site with 70% alcohol and subsequently by 10% povidone iodine solution. About 1–3 ml of venous blood were immediately inoculated into BACTEC PEDS Plus/F culture vials containing enriched broth (Soybean-Casein Digest broth with resins) and incubated in BACTEC 9050 blood culture instrument (Beckton-Dickenson, USA) at 35.5°C±1.5°C for 5 days. The remaining 1–2 ml blood was used for complete blood count. Microbial growth that could be detected by flag and audible sound of the instrument was sub-cultured on 5% blood agar, chocolate agar and MacConkey agar plates and was incubated at 37°C for 18–24 h for bacterial isolation. The blood and MacConkey agar plates were incubated aerobically while chocolate agar were incubated in microaerophilic atmosphere (5–10% CO2) using a candle jar [17, 18, 19]. Identification of culture isolates were done according to standard bacteriological techniques and their characteristic appearance on their respective media, Gram smear technique, hemolytic activity on sheep blood and rapid bench tests such as catalase, coagulase and optochin tests for Gram positive bacteria were used. In case of Gram negative bacteria API20E (Biomerieux, France) was used and followed by serological identification for Salmonella species. Finally, the Kirby-Bauer diffusion method was used to test the susceptibility of the isolates on Muller-Hinton agar according to procedures of Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute (CLSI 2010) [20]. For Gram positive bacteria discs tested included; Ampicillin (10μg), Cefoxitin (30μg), Ciprofloxacin (5μg), Clindamycin (2μg), Erythromycin (15μg), Chloroamphinicole (30μg), Penicillin (10U), Vancomycin (30μg), Gentamicin (10μg), Ceftriaxone (5μg), Sulphamethaxazole/trimethoprim (25μg) and Tetracycline (30μg). For Gram negatives Ampicillin (10μg), Nalidixic acid (30μg), Cefoxitin (30μg), Ceftriaxone (30μg), Ciprofloxacin (5μg), Gentamicin (10μg), Chloroamphinicole (30μg), Sulphamethaxazole/trimethoprim (25μg) and Tetracycline (30μg) discs were used. The reference strains used as control for disc diffusion testing and BACTEC PEDS Plus/F culture media were S. aureus (ATCC-25923), P. aeruginosa (ATCC-27853), E. coli (ATCC-25922), Haemophilus influenzae (ATCC-49247), Streptococcus pneumoniae (ATCC-49029) and Enterococus fecalis (ATCC-29212).

Data analysis

Data were entered, cleared, and analyzed using SPSS version-19 software package and MS excel 2007. Statistical test between dependent and independent variables was done using Chi squared test (χ2) and odds ratio to test the strength of association. Where the numbers in a cell was less than five, a Fisher’s exact test was used. Logistic regression analysis was used to identify factors independently associated with bacteraemia. The Hosmer–Lemeshow test was used to test the final model for goodness-of-fit. P-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethical considerations

Approval for this study was obtained from Department of Medical Laboratory Science Departmental Research and Ethics Review Committee (DRERC Addis Ababa University, AHRI/ALERT Ethics Review Committee (AAERC) and National Ethics Review Committee (NERC). Prior to data collection, necessary support letter from the study sites and written informed consent from the parents or legal guardians of each eligible case were obtained.

3. Results

Characteristic of study population

During the study period 201 blood samples from clinically suspected cases of pediatric septicemia were obtained. Of this, 110 (54.7%) were males resulting in an overall male to female ratio of 1.2:1. The median age of the participants was five days with a range of one day to twelve years from which the majority 147 (73.1 %) of them were neonates, the median weight was 3.0kg. The majority (94.5%) of blood culture specimens were obtained from in-patients (patients decided to be admitted or already admitted at time of sampling). Among admitted cases the mean length of hospital stay from the date of admission to blood sample collection for culture was 4.29 days with a range of 1 to 78 days. Indwelling medical device such as intravenous (IV) usage were observed in 129 (64.2%) of the study participants [Table 2].

Table 2.

Background characteristics and blood culture results in children suspected of having sepsis

| Variables | Culture Positive (n=56) No. (%) |

OR (95%CI) | P= value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex

| |||

| Female (91) | 26(46.4) | ||

|

|

|

||

| Male (110) | 30(53.6) | 1.283(0.627–2.625) | 0.494 |

|

|

|

||

| Age | |||

|

|

|||

| ≤28 days (147) | 46(82.1) | 0.784 | |

|

|

|||

| >28 days–2 years (29) | 5(8.9) | 0.330(0.013–8.258) | 0.500 |

|

|

|||

| >2–12 years (25) | 5(8.9) | 0.494(0.031–7.820) | 0.617 |

|

|

|||

| Weight | |||

|

|

|||

| 2.5–4kg (87) | 30(53.6) | 0.010 | |

|

|

|||

| <1.5kg (17) | 9(16.1) | 29.136(2.035–417.253) | 0.013 |

|

|

|||

| 1.5–2.5kg (50) | 11(19.6) | 79.006(4.434–1407.755) | 0.003 |

|

|

|||

| >4kg (47) | 6(10.7) | 19.131(1.164–314.512) | 0.039 |

|

| |||

| Length of Hospital stay

| |||

| ≤10 days (134) | 32(57.1) | ||

|

|

|||

| >10 days (67) | 24(42.9) | 0.599(0.170–0.841) | 0.547 |

|

|

|||

| Indwelling medical device | |||

|

|

|

||

| No (72) | 22 (69.3) | ||

|

|

|

||

| Yes (129) | 34(60.7) | 1.317(0.590–2.940) | 0.501 |

|

|

|

||

| Pre-sample antibiotic history | |||

|

|

|

||

| No (102) | 24(42.9) | ||

|

| |||

| Yes (99) | 32(57.1) | 0.610(0.283–1.313) | 0.206 |

|

| |||

| Co-morbidities

| |||

| No (149) | 45(80.4) | 0.794 | |

|

| |||

| Pneumonia (17) | 3(5.4) | 0.202(0.010–4.133) | 0.299 |

|

|

|||

| Cancer/leukemia (14) | 4(7.1) | 0.160(0.006–4.153) | 0.270 |

|

|

|||

| Meningitis (9) | 1(1.8) | 1.949(0.024–37.340) | 0.978 |

|

|

|

||

| Chronic heart disease (9) | 2(3.6) | 0.099(0.002–4.479) | 0.234 |

|

|

|

||

| Osteomyelitis (1) | 1(1.8) | 0.460(0.013–15.718) | 0.666 |

|

| |||

| White Blood Cell count/mm3

| |||

| 5000–20000 (144) | 38(67.9) | 0.859 | |

|

|

|||

| <5000 (9) | 3(5.4) | 1.128(0.503–2.526) | 0.770 |

|

|

|||

| >20000 (48) | 15(26.8) | 1.702(0.248–11.674) | 0.588 |

|

| |||

| Neutrophil count (%)

| |||

| 30–60 (80) | 19(33.9) | 0.755 | |

|

|

|||

| <30 (23) | 6(10.7) | 0.834(0.375–1.855) | 0.655 |

|

|

|||

| >60 (98) | 31(55.4) | 0.660(0.204–2.141) | 0.489 |

|

| |||

| Platelet count/mm3

| |||

| 1.5–4.0×l05 (125) | 27(48.2) | 0.071 | |

|

|

|||

| <150,000 (56) | 21(37.5) | 0.322(0.096–1.082) | 0.067 |

|

|

|||

| >400,0003 (20) | 8(14.3) | 0.644(0.178–2.335) | 0.503 |

The clinical features which usually rule out sepsis and help to request for blood culture and initiation of proper empirical management in pediatric sepsis cases are summarized in Table 1. Of the 201 patients investigated for blood stream infections, the commonest clinical finding was tachypenea 104 (51.7%). It followed by fever (auxiliary temp>37.5°C), feeding/sucking failure, hypothermia (Temp < 36°C), tachycardia and cough which was observed in 96 (47.8%), 91 (45.3%), 79 (39.3%), 71 (35%) and 39 (19.4%), respectively. More than one clinical features of sepsis were observed in the majority of the study subjects. Among the present clinical features lethargy (OR=3.125; 95%CI =1.020–9.572 and P= 0.046) was found to be significantly associated with positive blood culture as analyzed by logistic binary regression.

Table 1.

Clinical features of 201 children investigated for blood stream infections

| Clinical features | Total N (%) |

Culture positive (N=56) |

Odds Ratio (95%CI) |

P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tachypenea | 104(51.7) | 32(57.1) | 1.659 (0.739–3.727) | 0.220 |

| Fever(>37.5°C) | 96(47.8) | 23(41.1) | 1.095 (0.369–3.251) | 0.871 |

| Failure to feed/suck | 91(45.3) | 22(39.3) | 0.557 (0.278–1.116) | 0.099 |

| Hypothermia(<36°C) | 79(39.5) | 26(46.4) | 1.800(0.595–5.447) | 0.298 |

| Tachycardia | 71(35.3) | 21(37.5) | 0.665(0.285–1.555) | 0.347 |

| Cough | 39(19.4) | 6(10.7) | 0.208(0.057–0.755) | 0.017 |

| Vomiting | 32(15.9) | 9(16.1) | 1.617(0.514–5.089) | 0.411 |

| Apnea | 29(14.4) | 7(12.5) | 1.189(0.421–3.353) | 0.744 |

| Respiratory distress | 29(14.4) | 10(17.9) | 1.684(0.675–4.204) | 0.264 |

| Jaundice | 27(13.4) | 10(17.9) | 1.881 (0.744–4.756) | 0.182 |

| Lethargy | 25(12.4) | 9(5.4) | 3.125 (1.020–9.572) | 0.046 |

| Diarrhea | 16(8) | 5(8.9) | 1.640 (0.391–6.873) | 0.499 |

| Abdominal destination | 9(4.5) | 3(5.4) | 1.044(0.199–5.481) | 0.960 |

| Seizures | 6(3) | 3(5.4) | 1.651(0.264–10.339) | 0.592 |

| Shock/Coma | 6(3) | 1(1.8) | 0.317(0.028–3.621) | 0.355 |

| Abnormal CNS | 5(2.5) | 2(3.6) | 4.889(0.514–46.482) | 0.167 |

Factors associated with positive blood culture

We had seen different demographic and clinical characteristic factors such as gender, age groups, weight at enrolment, length of hospital stay before sampling, history of indwelling medical device, history of antibiotic usage before sampling, existence of co-morbidities and some hematological parameters of the 201 study subjects [Table 2]. When we evaluate and compare blood culture confirmed sepsis cases characteristics with that of culture negative, weight at enrollment were significantly statistically associated with culture proven septicemia. On the other hand children at lower weight of their age at enrolment found to be more prone to acquire culture proven sepsis as compared to children with considerably normal and high weight.

Culture results

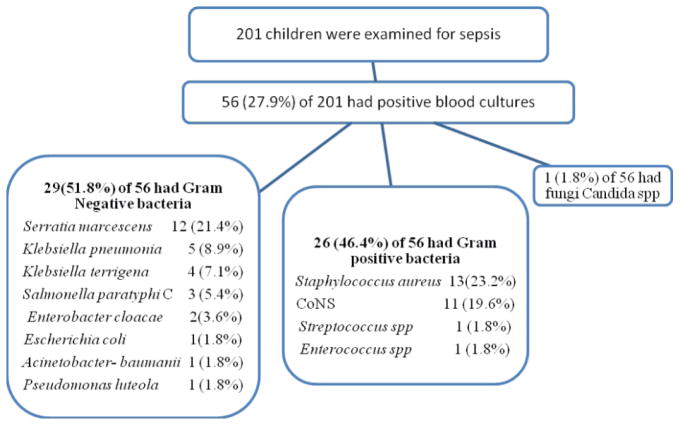

Of 201 children with clinical sepsis positive blood culture was found in 56 (27.9%). Among the 56 cases with blood culture confirmed sepsis 30 (53.6%) were males. The majority 46 (82.1%) of them were neonates (≤ 28 days). The Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria accounted for 26 (46.4%) and 29 (51.8%), respectively. The commonest Gram positive bacterial isolates were Staphylococcus aureus 13 (23.2%) and Coagulase negative Staphylococci (CoNS) 11 (19.6%), while Enterococcus spp and Streptococcus spp accounts only one isolate each. Among Gram negative bacterial isolates the most predominate organisms were Serratia marcesence 12 (21.4%) followed by Klebseiella spp 9 (16%) (Klebsiella pneumoniaeand Klebsiella terrigena), 3 (5.4%) Salmonella spp and 2 (3.6%) Enterobacter cloacae while Escherichia coli, Acinetobacter baumanniand Pseudomonas luteola were only accounts one isolate each as shown in fig. 1. With the exception of few Staphylococcus aureus (4) and CoNS (3) as well as Escherichia coli, Streptococcus spp and Candida spp, all other organisms were identified from neonates.

Fig. 1.

Study enrollment chart and isolates recovered from blood cultures of 56 children

Antimicrobial resistance of blood culture isolates

Antimicrobial agents were used before and after blood culture results. Out of the 201 patients included in this study 99 (49.3%) had received antibiotic empirically before 72 hours of sampling. Of the 99 patients who were treated with empiric antibiotics, 32 (32.3%) had positive blood culture. Ampicillin and Gentamicin were among the most common empirically used antibiotics during our study. The resistance patterns of isolates from blood culture against 13 antimicrobial agents are presented in Table 3. The highest degree of resistance in Staphylococcus aureus was seen against Penicillin 92.3% followed by Ampicillin 84.6%, Co-trimoxazole 61.5% and Tetracycline 53.8%. CoNS isolates were 100% resistant to Ampicillin, 81.8% to Penicillin and Co-trimoxazole each. Serratia marcescens was found to be 100% resistance to Ampicillin followed by Gentamicin, Tetracycline and Co-trimoxazole (91.7% each) on the other hands it was 100% sensitive to Ciprofloxacin and Nalidixic acid. For Klebsiella spp, Ampicillin, Gentamicin and Ceftriaxone, the common empirically used agents for sepsis, were 100% resistance followed by Co-trimoxazole 77.8% and Tetracycline 55.5%. Salmonella spp was 100% resistant to Ampicillin, Chloramphinicol, Gentamicin, Tetracycline, Co-trimoxazole and Ceftriaxone in other ways it was 100% sensitive to Ciprofloxacin, Nalidixic acid and Cefoxitin. For Enterobacter cloacae, Ampicillin, Tetracycline, Co-trimoxazole and Ceftriaxone were 100% resistance while 100% sensitive to Ciprofloxacin, Nalidixic acid, Cefoxitin, Chloramphinicol and Gentamicin. Multidrug resistance (resistant to three or more antibiotics) was observed among 92.7% (51 of 55) of Gram positive and Gram negative bacterial isolates. Among the tested antibiotics the highest degree of resistance was seen against Penicillin, Ampicillin, Gentamicin, Tetracycline and Co-trimoxazole. The overall range of resistance for different antibiotics was from 0% to 100%.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial resistance pattern of bacteria isolated from blood culture

| Resistance Proportion of Bacterial isolates (R%)

|

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Antimicrobial drugs | S.aureus | S.marcescens | CoNS | Klebsiella Spp | Salmonella spp | E. cloacae | Other GNB- | Other GPB- |

| N=13 | N=12 | N=11 | N=9 | N=3 | N=2 | N=3 | N=2 | |

|

| ||||||||

| Penicillin | 92.3 | ND* | 81.8 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | 100 |

|

| ||||||||

| Ampicillin | 84.6 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

|

| ||||||||

| Clindamycin | 0 | ND* | 0 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | 0 |

|

| ||||||||

| Erythromycin | 30.8 | ND* | 54.5 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | 0 |

|

| ||||||||

| Chloramph. | 7.7 | 25 | 36.4 | 44.4 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 50 |

|

| ||||||||

| Ciprofloxacin | 30.8 | 0 | 18.2 | 44.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

|

| ||||||||

| Vancomycin | 15.4 | ND* | 18.2 | ND* | ND* | ND* | ND* | 0 |

|

| ||||||||

| Cefoxitin | 38.5 | 33.3 | 54.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 66.7 | 50 |

|

| ||||||||

| Gentamycin | 30.8 | 91.7 | 36.4 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 100 | 50 |

|

| ||||||||

| Tetracycline | 53.8 | 91.7 | 45.5 | 55.5 | 100 | 100 | 66.7 | 100 |

|

| ||||||||

| SXT**** | 61.5 | 91.7 | 81.8 | 77.8 | 100 | 100 | 66.7 | 0 |

|

| ||||||||

| Ceftriaxone | 46.2 | 16.7 | 27.3 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 50 |

|

| ||||||||

| Nalidixic acid | ND* | 0 | ND* | 44.4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ND* |

ND*: Not done R%: Proportion of Resistance SXT****: Sulphamethaxozol/Trimethoprim; GNB**: Gram negative bacteria (Acinetobacter baumanii, Escherichia.coli, and Pseudomonas leutole) GPB***: Gram positive bacteria (Enterococcus spp and Streptococcus. spp).

4. Discussion

Despite advances in diagnosis and treatment, bacterial sepsis remains a major cause of pediatric morbidity and mortality, particularly among neonates in developing countries. The causative agents of sepsis and their antibiotic susceptibility patterns also become varied from time to time and from place to place. Detection of bacteria in blood has an important role in diagnosis for a febrile patient; to establish the presence of infection, to reassure the clinician about the chosen empirical therapy, and to provide up-to date information on the local etiologic patterns and antibiotic sensitivities as this will guide the clinician in the management of the patient. Therefore for the effectual management of septicemia in children, study of bacteriological profile along with the antimicrobial sensitivity pattern plays a great role. The present study included 201 pediatric patients from the neonatal to 12 years of age with two or more clinical signs and symptoms of sepsis. Although not statistically significant tachypenea (51.7%) were among the most prevalent clinical signs and symptoms in our study and followed by fever (47.8%), failure to feed/suck (45.3%), hypothermia (39.5%), tachycardia (35.3%) and cough (19.4%). However lethargy were statistically significant indicator of sepsis in the present study (P=0.046). This is inconsistent with the previously done studies in which temperature instability, poor feeding and respiratory distress were predominating [21, 22].

In this study, out of 201 children who visited the study sites with suspicious of septicemia during the study period, blood culture confirmed septicemia was 56 (27.9%). These findings are consistent with reports from other studies done in Lahore (27.9%) [23], Cameroon (28.3%) [24] and Nigeria (22%) [25]; but it is higher than the study done in Tanzania (13.4%) [26], Uganda (17.1%) [27], Nepal (4.2%) [28] and Ethiopia (7.7%) [22]. This difference might be due to difference in blood culture system, age of children, infection prevention practice or the increment of multidrug resistant organisms for different reasons or variation in study sites and time of the studies. It may be also due to the emerging of a number of pathogens being as a nosocomial or community acquired. Among 56 blood culture isolates, 26 (46.4%) had sepsis with Gram positive bacteria and 29 (51.8%) with Gram negative bacteria of which 27 (93.1%) belonged to Enterobacteriaceae family. The remaining one of the isolate was yeast (Candida spp). Out of the positive cultures only 3.6% were done on an outpatient basis which may be insinuating that clinicians readily admit patients when there is an indication for septicemia that evidenced by physical condition of the child.

In this study, the rate of isolation was found highest among newborns 46 (31.3%), while the other age groups of this study accounts only for 10 (18.5%) of positive blood culture within age groups. The higher rate of bacterial isolation among neonates compared to other pediatric age groups may be related to immaturity of the immune system at birth; hence they are more vulnerable to infections. This result is consistent with other studies done among neonates in Ethiopia (28%) [22] and Cameroon (34.9%) [24]. On the other hand, a relatively high rate of positive blood culture was reported among neonates in NICU of TikurAnbessa Specialized Hospital (44.7%) [22], Gondar (63%) [29] and Nepal (64%) [28]. A possible explanation for this might be that the difference in time variation or epidemiological difference of etiological agents or infection prevention practice.

In the present study there was no significant difference between males and females in the overall blood culture growth positive rate (males 27.3% vs females 28.6%, P = 0.838). This finding is in agreement with report from Nigeria (males 21.10% and females 23. 38% [25], although the age of patients in that study ranged from 0–5 years. On the other hands, this finding does not agree with several other studies who had reported high culture positivity in males as compared to females [23, 28, 30, 31]. The reason for this difference is unclear and need further study with large sample size.

The frequency of isolation of Gram negative and Gram positive bacteria from blood culture in this study was 51.8% and 46.4%, respectively. This finding is similar to several other studies in Lahore (50.1% vs 47.5%) [23], Uganda (58% vs 42%) [27] and Addis Ababa (56.3% vs 43.7%) [21]. In contrast to the present finding, high Gram positive bacteria were reported by other studies done in Cameroon (56.2% versus 43.8%) [24], Tanzania (82.1% vs 17.9%) [26] and Gondar (70.2% vs 29.8%) [29]. The difference might be related to the difference in the practice of using medical device for which some Gram positive bacteria are directly associated or due to geographical variations.

The most predominant Gram positive bacteria identified in this study were Staphylococcus aureus (23.2%). In support to our study, other studies in Jimma [32], Jordan [30], Nepal [28] and Nigeria [25] also reported Staphylococcus aureus as the most common cause of septicemia. CoNS were the second most prevalent Gram positive bacteria (19.6%). Out of this, the highest rate (14.3%) was observed in neonates. Similar finding was also reported from Jimma (22.9%) [32]. However, our current finding is different from previous findings in Gondar (33.3%) [29], Addis Ababa (7.7%) [21] and Tanzania (67.4%) [26]. CoNS have long been considered as non-pathogenic and were rarely reported to cause severe infections. However, as a result of the combination of increased use of intravascular devices and increased number of hospitalized immunocompromised patients, CoNS have become the major cause of nosocomial bloodstream infections [24, 26, 31, 32]. In children from whom multiple blood cultures could not be applied the decision for CoNS as pathogen is relied on the observation of clinical features of sepsis, follow up the prognosis and also on the laboratory markers like time for positivity [33].

The most common Gram negative bacteria identified in this study were Serrratiamarcescens (21.4%). It is also the second most predominant cause of septicemia in our study next to S. aureus. As it was reported by other authors S. marcescenscan cause rapidly spreading outbreaks of severe and potentially fatal infections in neonatal units. It is an important nosocomial pathogen, especially in NICU, and it may cause serious infections, including sepsis, meningitis, and pneumonia, with significant associated morbidity and mortality in newborns [34]. Similarly, all isolates (21.4%) of S. marcescens were identified from NICU in our study. This was the highest finding when compared with other previous studies in Ethiopia [21]. This may be due to these bacteria emerging as nosocomial pathogen in the area of NICU. Although the source of this bacteria is not known clearly by our study as reported by other authors it may be transmitted to neonates through parenteral nutrition, skin cleansers, breast milk, breast pumps, soap and disinfectant dispensers, ventilators and air conditioning ducts or spread via contact with the patient during care [34, 35]. Over all, this finding is evidence for the change of organisms over time and difference in different geographic areas that are associated with pediatric sepsis.

Klebsiella (19%) such as Klebsiella pneumoniae (8.9%) and Klebsiella terrigena (7.1%) were the second predominantly identified Gram negative bacteria. The finding of K. pneumoniaewas in agreement with report from Jordan [30], Nepal [28]), and Cameroon [24]. On the other hand, this is a lower finding when compared with other studies on neonatal sepsis by Ghiorghis (38%) [20] and Shitaye et al (37% for K. pneumoniaeand 2.2% for K. terrigena) in Ethiopia [21] and in Gaza which reported 25.5% K. terrigena[36] as the causative agents of neonatal sepsis. Enterobacter cloacae blood stream infections also accounted for 3.6% in our study. This finding was in agreement with study done in Gondar (2.6%) [29] and Cameroon (5.5%) [24].

Septicemia caused by Salmonella spp accounted for 3 (5.4%) in our study. All three non-typhoidal Salmonella isolates were Salmonella paratyphi group C1 and were isolated from neonates. Our study is similar with study results by Abrhaet al in Jimma (8.6%) [32]. However this finding was lower compared with previously reported blood culture results from Defense Hospital in Addis Ababa (57%) [21]. This may be due to difference in the nature of the study participants as in our case majority of the patients were inpatients while in their cases the participating were from outpatients.

Based on susceptibility tests in the present study; multi-drug resistance (resistant to three or more commonly used drugs) was observed in most of the isolates (92.7%) in our study. Similarly other studies also reported high multi drug resistance for blood culture isolates [32, 37]. The most common resistance was seen to Ampicillin in almost all isolated bacteria. Staphylococcus aureus was the most resistant to Penicillin (92.3%) followed by Ampicillin (84.6%), Co-trimoxazole (61.5%) and Tetracycline (53.8%). This finding is similar with other investigators as reported by Mehta et al. [14]. Out of the 13 isolated Staphylococcus aureus 38.5% were resistance to Cefoxitin which indicates Methicillin resistance Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) [20, 38]. In support of our finding, Yusuf et al [31] and Latifet al [23] reported 41.7% and 31.25% MRSA, respectively. None of Serratia marcescens were resistant to Ciprofloxacin and Nalidixic acid, while low resistance was seen against Ceftriaxone (16.7%) and Chloramphinicol (25%). High resistance was observed to Ampicillin (100%), Gentamicin, Tetracyline and Cotrimoxazole (91.7 % for each). Salmonella spp was found to be the most sensitive to Ciprofloxacin, Nalidixic acid and Cefoxitin. On the other hand, all the three Salmonella isolates were 100% resistant to Ampicillin, Chloramphinicol, Gentamicin, Tetracycline, Co-trimoxazole and Ceftriaxone. Over all, Ciprofloxacin and Nalidixic acid were comparatively the most effective drugs against the tested Gram negative bacteria, while Vancomycin and Clindamycin were most effective to Gram positives. In support of our finding, other previous study in Gondar [29], Addis Ababa [21], Tanzania [26] and Uganda [27] demonstrated better effectiveness of Ciprofloxacin however it is contraindicated in children.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the present study showed that blood stream infection constituted about 27.9%. Staphylococcus aureus and Serratia marcescens were the most common isolates identified from blood culture in the current study. The most obvious finding of this study is that most of the isolates were multi-drug resistant. The detection of multi-drug resistant isolates may further limit therapeutic options so that it calls for further studies to determine the most feasible combination of antibiotics for the management of blood stream infection in children.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the technical support provided by the members of the Departments of Bacteriology and Pediatrics units of TikurAnbessa Specialized and Yekatit 12 Hospitals. We also thank Mr Yoseph Kenea, for his excellence statistic support. This work was supported by AHRI/ALERT and Department of Medical Laboratory Sciences AAU.

Footnotes

Competing interests

We authors declare that we have no competing interests

References

- 1.Archibald LK, McDonald LC, Nwanyanwu O, Kazembe P, Dobbie H, Tokars J, et al. A Hospital-Based Prevalence Survey of Bloodstream Infections in Febrile Patients in Malawi: Implications for Diagnosis and Therapy. The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2000;181:1414–20. doi: 10.1086/315367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ogunleye VO, Ogunleye AO, Ajuwape ATP, Olawole OM, Adetosoye AI. Childhood Septicaemia Due To Salmonella Species in Ibadan, Nigeria. African Journal of Biomedical Research. 2005;8:131–4. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meremikwu MM, Nwachukwu CE, Asuquo AE, Okebe JU, Utsalo SJ. Bacterial isolates from blood cultures of children with suspected septicaemia in Calabar, Nigeria. BMC Infect Dis. 2005;5:110–5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-5-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garg A, Anupurba S, Garg J, Goyal RK, Sen MR. Bacteriological Profile and Antimicrobial Resistance of Blood Culture Isolates from a University Hospital. JIACM. 2007;8(2):139–43. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clapp DW. Developmental regulation of the immune system. Semin Perinatol. 2006;30(2):69–72. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wynn JL, Seed PC, Cotten CM. Does IVIg Administration Yield Improved Immune Function in Very Premature Neonates? J Perinatol. 2010;30(10):635–642. doi: 10.1038/jp.2009.197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma M, Yadav A, Yadav S, Goel N, Chaudhary U. Microbial Profile of Septicemia in Children. Indian Journal for the Practicing Doctor. 2008;5(4):9–10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Prabhu K, Bhat S, Rao S. Bacteriologic profile and antibiogram of blood culture isolates in a pediatric care unit. J Lab Physicians. 2010;2:85–88. doi: 10.4103/0974-2727.72156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Enrione MA, Powell KR. Sepsis, septic shock and systemic inflammatory response syndrome. In: Kleigman RM, Behraman RE, Jenson HB, Stanton BF, editors. Nelson textbook of paediatrics. 18. Philadelphia: WB Saunders; 2007. p. 1094. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nwadioha SI, Nwokedi EOP, Kashibu E, Odimayo MS, Okwori EE. A review of bacterial isolates in blood cultures of children with Septicemia in a Nigerian tertiary Hospital. Afr J Microbiol Res. 2010;4:222–5. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Buttery JP. Blood cultures in newborns and children: optimizing an everyday test. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2002;87:25–28. doi: 10.1136/fn.87.1.F25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Murty DS, Gyaneshwari M. Blood cultures in paediatric patients: A study of clinical impact. Indian Journal of Medical Microbiology. 2007;25(3):220–224. doi: 10.4103/0255-0857.34762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Corless CE, Guiver M, Borrow R, Edwards-Jones V, Fox AJ, Kaczmarski EB. Simultaneous detection of Neisseria meningitidis, Haemophilus influenzae, and Streptococcus pneumoniaein suspected cases of meningitis and septicemia using real-time PCR. J ClinMicrobiol. 2001;39:1553–8. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.4.1553-1558.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mehta M, Dutta P, Gupta V. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of blood isolates from a teaching hospital in North India. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2005;58:174–176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ghiorghis B, Geyid A, Haile M. Bacteraemia in febrile out-patient children. East Afr Med J. 1992;69(2):74–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Naing L, Winn T, Rusli BN. Practical Issues in Calculating the Sample Size for Prevalence Studies. Archives of Orofacial Sciences. 2006;1:9–14. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheesbrough M. District laboratory practice in tropical countries. 2. Vol. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 2000. pp. 124–5. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vandepitte J, Verhaegen J, Engbaek K, Rohner P, Piot P, Heuck CC. Basic laboratory procedures in clinical bacteriology. 2. 2003. pp. 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Murray B, Pfaller T. Manual of Clinical Microbiology. 6. American Society of Microbiology Press; Washington DC: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. 20th Informational Supplement. Wayne, PA: CLSI; 2010. Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. CLSI document M100-S20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shitaye D, Asrat D, Woldeamanuel Y, Worku B. Risk factors and etiology of neonatal sepsis in TikurAnbessa University Hospital, Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2010;48(1):11–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ghiorghis B. Neonatal sepsis in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a review of 151 bacteremic neonates. Ethiop Med J. 1997;35(3):169–76. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Latif S, Anwar MS, Ahmad AI. Bacterial pathogens responsible for blood stream infection (BSI) and pattern of drug resistance in A Tertiary Care Hospital of Lahore. Biomed BiochimActa. 2009;25:101–5. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamga HLF, Njunda Al, Nde PF, Assob JCN, Nsagha DS, Weledji P. Prevalence of Septicemia and Antibiotic Sensitivity Pattern of Bacterial isolates at the University Teaching Hospital, Yaoundé, Cameroon. Afr J ClnExperMicrobiol. 2011;12(1):2–8. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Omoregie R, Egbe CA, Ogefere HO, Igbarumah, Omijie RE. Effects of Gender and Seasonal Variation on the Prevalence of Bacterial Septicemia among Young Children in Benin City, Nigeria. Libyan J Med. 2009;4:153–157. doi: 10.4176/090206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moyo S, Aboud S, Kasubi M, Maselle SY. Bacteria isolated from bloodstream infections at a tertiary hospital in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania – antimicrobial resistance of isolates. S Afr Med J. 2010;100:835–838. doi: 10.7196/samj.4186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bachou H, Tylleskär T, Kaddu-Mulindwa DH, Tumwine JK. Bacteraemia among severely malnourished children infected and uninfected with the human immunodeficiency virus-1 in Kampala, Uganda. BMC Infectious Diseases. 2006;6:160. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-6-160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karki S, Rai GK, Manandhar R. Bacteriological Analysis and Antibiotic Sensitivity Pattern of Blood Culture Isolates in Kanti Children Hospital. J Nepal PaediatrSoc. 2010;30(2):94. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ali J, Kebede Y. Frequency of isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of bacterial isolates from blood culture, Gondar University teaching hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Ethiop Med J. 2008;46(2):155–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mohammad A. Bacteremia among Jordanian children at Princess Rahmah Hospital: Pathogens and antimicrobial susceptibility patterns. Iran J Microbiol. 2010;2:23–27. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yusuf A, Worku B. Descriptive cross –sectional study on neonatal sepsis in the Neonatal intensive care unit of TekurAnbessa Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Ethiopian Journal of Pediatrics and Child Health. 2010;6(6):175–82. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abrha A, Abdissa A, Beyene G, Getahun G, Girma T. Bacteraemia among Severely Malnourished Children in Jimma University Hospital, Ethiopia. Ethiop J Health Sci. 2011;21(3):40–54. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asangi SY, Mariraj J, Sathyanarayan MS, Nagabhushan, Rashmi Speciation of clinically significant Coagulase Negative Staphylococci and their antibiotic resistant patterns in a tertiary care hospital. Int J Biol Med Res. 2011;2(3):735–9. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mitt P, Kõljalg S, Lõivukene K, Sepp E, Lutsar I, Maimets M, et al. Laboratory markers to determine clinical significance of coagulase-negative staphylococci in blood cultures. Crit Care Clin. 2007;11(4):27. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fleisch F, Zimmermann-Baer U, Zbinden R, Bischoff G, Arlettaz R, Waldvogel K, et al. Three consecutive outbreaks of Serratiamarcescensin a neonatal intensive care unit. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34(6):767–73. doi: 10.1086/339046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Almuneef MA, Baltimore RS, Farrel PA, Reagan-Cirincione P, Dembry LM. Molecular typing demonstrating transmission of gram-negative rods in a neonatal intensive care unit in the absence of a recognized epidemic. Clin Infect Dis. 2001;32:220–7. doi: 10.1086/318477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Elamreen FA. Neonatal sepsis due to multidrug-resistant Klebsiellaterrigenain the neonatal intensive care unit in Gaza, Palestine. Critical Care. 2007;11(4):12. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fernandes CJ, Fernandes LA, Collignon P. Cefoxitin resistance as a surrogate marker for the detection of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J AntimicrobChemother. 2005;55:506–10. doi: 10.1093/jac/dki052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]