Abstract

One hundred and twenty five years ago, Roy and Sherrington made the seminal observation that neuronal stimulation evokes an increase in cerebral blood flow.1 Since this discovery, researchers have attempted to uncover how the cells of the neurovascular unit—neurons, astrocytes, vascular smooth muscle cells, vascular endothelial cells and pericytes—coordinate their activity to control this phenomenon. Recent work has revealed that ionic fluxes through a diverse array of ion channel species allow the cells of the neurovascular unit to engage in multicellular signaling processes that dictate local hemodynamics.

In this review we center our discussion on two major themes: (1) the roles of ion channels in the dynamic modulation of parenchymal arteriole smooth muscle membrane potential, which is central to the control of arteriolar diameter and therefore must be harnessed to permit changes in downstream cerebral blood flow, and (2) the striking similarities in the ion channel complements employed in astrocytic endfeet and endothelial cells, enabling dual control of smooth muscle from either side of the blood–brain barrier. We conclude with a discussion of the emerging roles of pericyte and capillary endothelial cell ion channels in neurovascular coupling, which will provide fertile ground for future breakthroughs in the field.

Keywords: Ion channels, calcium signaling, calcium channels, potassium channels, transient receptor potential channels, neurovascular coupling, functional hyperemia, cerebral blood flow, neurovascular unit, parenchymal arteriole, pial artery, smooth muscle, endothelium, astrocytic endfoot, cerebrovascular resistance

Introduction

To support ongoing function, neurons must extract oxygen and glucose from the cerebral circulation on an as-needed basis. The continuous supply of nutrients to match local demand is made possible by neurovascular coupling (NVC). The NVC signaling cascade recruits multiple cell types to link neuronal activity to a rise in local blood flow—a phenomenon termed functional hyperemia—thus providing the energy substrates required to satisfy the enhanced metabolic requirements of active neurons. A number of mechanisms have evolved in parallel to ensure the fidelity of neurovascular communication, and many of these are dependent on ion channel signaling. Ion channels are also important contributors to the control of basal cerebral arteriolar tone, which sets the resting level of brain perfusion and permits dynamic changes in blood flow to match variations in local neuronal activity.

If the NVC cascade is impaired or cerebrovascular tone is pathologically altered, cerebral blood flow is compromised and neuronal dysfunction ensues. Cerebral blood flow is disturbed in a range of disorders, including Alzheimer’s disease,2 hypertension,3 stroke,4 diabetes,5 and CADASIL (cerebral autosomal dominant arteriopathy with subcortical infarcts and leukoencephalopathy).6 Thus, a fuller understanding of how cerebrovascular tone and functional hyperemia are controlled may unearth new treatment options for brain disorders with a vascular component.

In this review, our primary focus is on neurovascular ion channel signaling at the level of the parenchymal arteriole, where the influence of signaling molecules released from astrocytic endfeet on arteriolar diameter and blood flow is well established. We explore two major themes. First, we examine the ion channels that facilitate tight control of smooth muscle (SM) membrane potential (Vm) and thus the contractile state (tone) of these cells. Second, we focus on the marked similarity in ion channel expression and signaling between astrocytic endfeet and endothelial cells (ECs), which exert dual control of SM tone from parenchymal and luminal sides of the vessel wall, respectively. Our discussion centers on studies examining ion channel signaling in vivo and in acutely isolated, intact ex vivo preparations. Where relevant, we compare parenchymal arterioles with vessels from other circulatory beds. We conclude with an exploration of a growing frontier of research: the control of cerebral blood flow at the capillary level. Here we highlight the known roles of ion channels in pericytes and capillary ECs, which likely have an important role in conducting signals from deep within the capillary bed upstream to parenchymal arterioles. The major ion channels reviewed are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Expression and function of key ion channels in astrocytic endfeet, and ECs and SMCs of parenchymal arterioles.

| Astrocytic Endfeet | Notes, References | Parenchymal Endothelium | Notes, References | Parenchymal Smooth muscle | Notes, References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Membrane potential (mV) | −87 | In vivo, cell soma.7 | −35 to −40? | Not measured. Inferred from observations that EC-SMC Vm is nearly equivalent in hamster feed arteries.8 | −35 to −40 | In situ, 40 mm Hg.9,10 |

| Ca2+ channels | ||||||

| IP3R | + | Ca2+ wave generation.11 | +? | Not directly tested. Mediates Ca2+ signaling in other arteries.12 | +? | Not directly tested. UTP evokes Ca2+ waves in pial arteries.13 |

| RyR | – | Not present.11 | –? | Not directly tested. Not present in other arterioles. | + | Ca2+ waves in situ at 40 mm Hg. Ca2+ sparks in response to H+.14 |

| VDCC | –? | Nifedipine inhibition of Ca2+ waves.15 | –? | Not directly tested. Not present in other arterioles. | + | Depolarization-evoked Ca2+ entry leading to constriction.9 |

| TRPV4 | + | Ca2+ entry and wave propagation.16 | +? | Not directly tested. Present in pial endothelium.17,18 | + | Ca2+ influx.19 |

| TRPC6/M4 | n.d. | – | No effect of endothelium removal on TRPM4 responses.20 | + | TRPM4 contributes to myogenic tone.20 Both C6 and M4 contribute to tone in pial arteries.21 | |

| K+ channels | ||||||

| BK | + | Vasoactive K+ release.22,23 | – | Not present in acutely isolated cells.10 | + | Present in situ. Low basal activity at 40 mm Hg.10 |

| SK | – | Not detected.24 | + | Present in acutely isolated cells.10 | – | No effect of NS309 after endothelial removal.10 |

| IK | + | Detected in processes and endfeet. Engaged in NVC.24 | + | Present in acutely isolated cells.10 | – | No effect of NS309 after endothelial removal.10 |

| Kv | –? | Not directly tested. Membrane depolarization sufficient to engage Kv is unlikely to occur. | – | No voltage-activated currents after SK/IK blockade.10 | + | Tonically active in situ at 40 mm Hg. Resists constriction.25 |

| KIR2 | +? | Not directly observed in endfeet, but expressed by astrocytes.26 | + | Present in other arterioles.27 Preliminary data indicates present in parenchymal endothelium.26 | + | Activated by extracellular K+.22,23,28,29 |

Summary of the expression of ion channels involved in neurovascular coupling (NVC) in native preparations of astrocytic endfeet, parenchymal arteriole ECs and SMCs. Studies in culture systems were not considered. Question marks are used to highlight inferences drawn in cases where channels have not been directly observed in a particular cell type.

EC-SMC Vm: endothelial cell/smooth muscle cell membrane potential; VDCC: voltage-dependent calcium channel; TRP: Transient receptor potential; BK: large-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel; SK: small-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel; IK: intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channel; Kv: Voltage-dependent potassium channel; n.d.: no data.

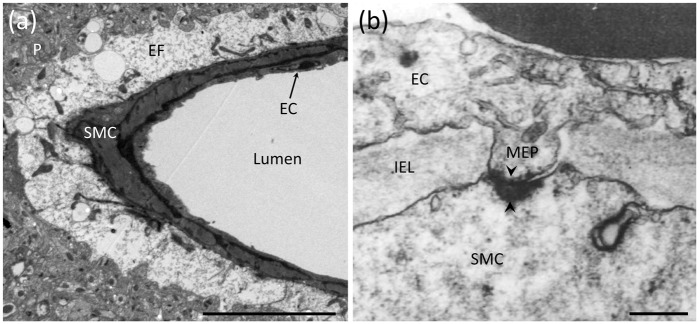

The neurovascular unit

The neurovascular unit (NVU) consists of neurons, astrocytes and the cells of parenchymal arterioles, which consist of a single layer of SM cells (SMCs) surrounding the endothelium (Figure 1a). Parenchymal arterioles originate from pial (surface) vessels and penetrate into the brain, where they become almost completely encased by astrocytic endfeet.30,31 This positions endfeet to act as intermediates between neurons and the vasculature. Similarly, endothelial membrane extensions project through fenestrations in the internal elastic lamina and basement membrane of arterioles to directly contact SMCs (Figure 1b). These structures—termed myoendothelial projections (MEPs)—not only provide direct contact between these two cell types through gap junctions but also offer a unique intracellular and extracellular microdomain signaling environment for controlling vascular tone. In contrast, direct cell–cell contact has not been observed between astrocytic endfeet and SMCs, although the membranes of these cells are closely opposed. Each parenchymal arteriole supplies a large territory of downstream capillaries, an anatomical organization that positions parenchymal arterioles as bottlenecks to the entry of blood into the brain.32 Therefore, control of parenchymal arteriole diameter by NVC mechanisms is of vital importance to the regulation of downstream blood flow.

Figure 1.

Anatomical features of the NVU and MEPs. (a) Electron micrograph depicting astrocytic endfeet (EF) enveloping a parenchymal arteriole with a single layer of SMCs and underlying ECs. Adjacent to the endfeet is the brain parenchyma (P) containing neuronal and astrocytic processes. Scale bar: 10 µm. (b) A MEP site through a fenestration in the internal elastic lamina (IEL) between an EC and SMC in a human parenchymal arteriole. Black arrowheads indicate a myoendothelial gap junction. Scale bar: 250 nm. Reproduced with permission from Aydin et al.33

The ionic composition in the NVU establishes the basal conditions for controlling cerebral blood flow

The choroid plexuses produce cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), which fills the ventricles and the subarachnoid space and circulates from the latter into the brain parenchyma via the Virchow-Robin space, taking a paravascular route through the ‘glymphatic’ system.34 The composition of CSF is distinct from that of plasma (see Table 2, reproduced from Brown et al.35). Thus, with the luminal surface of ECs exposed to plasma and the parenchymal surface of SMCs bathed in CSF, SMCs and ECs experience extracellular milieus with different ionic compositions. The concentrations of ions in these extracellular compartments dictate their equilibrium potentials and, by extension, both ion channel activity and Vm. This, in turn, influences the level of resting SM tone and tissue perfusion. Variations in local ion concentrations during neuronal activity modulate the SM Vm, thereby exerting a powerful effect on parenchymal arteriolar diameter; this is the central relationship underlying the dynamic regulation of cerebral blood flow.

Table 2.

The composition of plasma and cerebrospinal fluid.

| Plasma | CSF | |

|---|---|---|

| Na+ (mM) | 155 | 151 |

| K+ (mM) | 4.6 | 3.0 |

| Mg2+ (mM) | 0.7 | 1.0 |

| Ca2+ (mM) | 2.9 | 1.4 |

| Cl− (mM) | 121 | 133 |

| HCO3− (mM) | 26.2 | 25.8 |

| Glucose (mM) | 6.3 | 4.2 |

| Amino acids (mM) | 2.3 | 0.8 |

| pH | 7.4 | 7.4 |

| Osmolality (mosmol.Kg H2O−1) | 300 | 305 |

| Proteina (mg 100 g−1) | 6500 | 25 |

Rabbit CSF; all other values are for dog CSF. Reproduced from Brown et al.,35 with permission.

Part I: control of the smooth muscle membrane potential is central to the control of cerebral blood flow

The key role of the voltage-dependent Ca2+ channel as a membrane potential biosensor

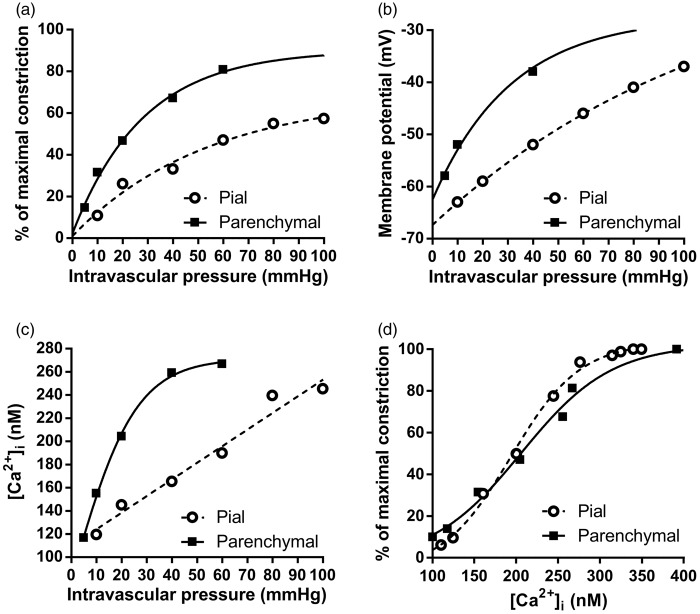

The Vm of SM exerts profound control over cerebral artery diameter.9,36 In isolated parenchymal arterioles, a graded increase in intravascular pressure, for example from 5 mm Hg to 40 mm Hg, causes graded Vm depolarization from approximately –60 mV to –40 mV, an elevation in intracellular calcium ([Ca2+]i) from ∼120 nM to ∼250 nM, and approximately 50% constriction9 (Figure 2). In contrast, Vm hyperpolarization to –60 mV causes near-maximal vasodilation (i.e. almost equivalent to the passive diameter of the vessel).9,36 The depolarization/vasoconstriction to increasing pressure is termed the ‘myogenic response’ and is an intrinsic property of small resistance arterioles from a range of vascular beds.37 In brain arterioles, the myogenic response is particularly important for cerebral autoregulation, in which vessels constrict or relax to maintain a constant level of brain perfusion despite varying peripheral blood pressure.30 Therefore, myogenic regulation sets the level of resting perfusion, while also providing a baseline tone from which arterioles can dilate or constrict in response to factors released during neuronal activity. As such, myogenic mechanisms can be viewed as the foundation upon which NVC mechanisms are constructed.

Figure 2.

Relationships between intravascular pressure, vessel diameter, [Ca2+]i and Vm in pial arteries and parenchymal arterioles. (a) One fundamental difference between vessels of the cerebral circulation is that parenchymal arterioles develop more tone in response to lower intravascular pressure compared to pial arteries. (b) The phenomenon in A is linked to the parenchymal arteriole SM Vm, which is more depolarized in response to lower pressure compared to pial arteries. (c) Increases in [Ca2+]i in response to increasing intravascular pressures are greater in parenchymal arterioles than in pial arteries owing to higher voltage-dependent calcium channel (VDCC) activity caused by the greater degree of SMC cell depolarization, as illustrated in (b). (d) There is no difference in the sensitivity of the SM contractile apparatus to Ca2+ between pial arteries and parenchymal arterioles, indicating that the difference in the pressure-constriction relationship between these two types of vessels is due to the difference in SM Vm in response to pressure. Data were re-plotted from ref.9 Parenchymal arteriole Vm data were obtained from F. Dabertrand (personal communication) and from Nystoriak et al.9 and Hannah et al.10

Pial arteries on the surface of the brain develop less myogenic tone in response to pressure compared with parenchymal arterioles, despite the fact that the relationship between SM [Ca2+]i and constriction is identical in both of these types of vessel (see Figure 2d). This is because parenchymal arteriole SM is more depolarized than pial SM at lower pressures (Figure 2b) and thus exhibits a greater influx of Ca2+ (Figure 2c) and greater constriction (Figure 2a). The molecular arrangement that leads to the higher sensitivity of parenchymal arterioles to pressure has not yet been elucidated but likely involves a loss of negative feedback control of the SM Vm by Ca2+ spark-BK channel interactions (see ‘Ryanodine Receptors in Smooth Muscle’, below).

L-type VDCCs are the key voltage sensors in vascular SM.38 These channels translate changes in the Vm into alterations in [Ca2+]i and thereby adjust the contractile state of the cell. Their central importance is evidenced by the fact that Vm changes induced by pressure or other agents have no effect on vascular tone in the presence of VDCC inhibitors,36 highlighting the vital role of Ca2+ entry through L-type VDCCs in vasoconstriction. Parenchymal arteriolar myocytes express L-type VDCCs composed of pore-forming CaV1.2 α1C-subunits and associated α2δ-, β- and γ-subunits.9,39 Recent studies have also presented evidence for the expression and function of T-type VDCCs in SMCs of pial arteries.40,41 However, no contribution of T-type channels to either [Ca2+]i or arteriolar tone has been shown at physiological pressures in isolated parenchymal arterioles.9

Neurovascular signaling mediators that converge on the SM utilize a variety of mechanisms to drive changes in Vm. Critically, this leads to either (1) closure of VDCCs (in the case of membrane hyperpolarization), a fall in global [Ca2+]i and vasodilation or (2) depolarization and an increase in VDCC open probability (Po), causing an increase in [Ca2+]i and vasoconstriction.38,42 Thus, tuning the SM Vm to modulate Ca2+ entry through VDCCs is the key mechanism for controlling the diameter of parenchymal arterioles and rapidly influencing cerebral blood flow.

A role for smooth muscle transient receptor potential channels in myogenic depolarization: evidence from pial and parenchymal arterioles

Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are a diverse family of cation-permeable channels activated by a wide range of stimuli.43 Members of the TRP family share an overall structural similarity, forming tetrameric homomeric or heteromeric channels from subunits containing six transmembrane domains. TRP channels are broadly classified on the basis of sequence homology into six subfamilies in mammals: TRPA (ankyrin), TRPC (classic or canonical), TRPM (melastatin), TRPML (mucoliptin), TRPP (polycystin) and TRPV (vanilloid).44 Most of these channels act as routes for the entry of Ca2+, although some, such as a subset of TRPM channels, primarily mediate Na+ entry. For a comprehensive overview of TRP channels in the vasculature, see Earley and Brayden.45

Mounting evidence suggests that intravascular pressure or vasoconstrictor agonists can cause Vm depolarization through the activation of TRP channels in pial artery myocytes; this, in turn, increases the activity of VDCCs and promotes vasoconstriction. TRPV4, TRPC3, TRPC6 and TRPM4 channels have all been identified in pial SM,46–49 and recent studies indicate that pressure causes depolarization through activation of TRPM4 and TRPC6 channels. Monovalent cation-permeable TRPM4 channels, though impermeable to Ca2+ ions,44 are activated by sarcoplasmic reticulum (SR) 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptor (IP3R)-mediated Ca2+ release events in pial artery myocytes.50 This results in an influx of Na+ through TRPM4, which can be measured as a transient inward cation current (TICC).50 Pressure-induced constriction of ex vivo cerebral arteries requires functional TRPM4 channels,46 and blocking TRPM4 causes almost maximal vasodilation of pressurized arteries,51 suggesting that these channels are vitally important for the myogenic response. Similarly, activation of TRPC6 channels, which have a Ca2+:Na+ permeability ratio of ∼6:1,52 is another contributor to pressure-induced constriction of isolated pial arteries, as evidenced by the fact that knockdown of TRPC6 using antisense oligonucleotides attenuates the myogenic response.47 A recent study,21 conducted in isolated myocytes and pressurized pial arteries, unifies the contributions of TRPC6 and TRPM4 into a single mechanism for myogenic constriction. Here, pressure-induced activation of phospholipase C (PLC) γ1 liberates IP3 and diacyl glycerol (DAG). Subsequently, DAG activates TRPC6 channels directly and the resulting Ca2+ influx across the sarcolemma acts synergistically with IP3 to activate IP3Rs, releasing Ca2+ from the SR that then activates TRPM4 channels to depolarize the membrane.21

Despite these major advances in our understanding, the mechanism by which pressure activates TRP channels has not been firmly established. In addition to the possibility that TRP channels directly sense membrane deformation,53 they may be attached to other cellular structures that respond to pressure, such as the cytoskeleton.54 Alternatively, upstream mechanosensitive signaling elements may transduce physical forces into second messenger signaling (such as PLC activation),21 which is then detected by TRP channels.55 These possibilities, which are not mutually exclusive, have recently been reviewed in detail.56

In contrast to the vasoconstriction associated with TRPC6 and TRPM4 activation, SM TRPV4 channels, which are non-selective but possess a high permeability to Ca2+, have been implicated in vasodilatory mechanisms in pial arteries.49 According to this mechanism, reported by Earley et al., epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) activate TRPV4 channels, which conduct Ca2+ into the cell and enhance ryanodine receptor (RyR)-mediated Ca2+ spark activity (see below),49 resulting in vasodilation.57

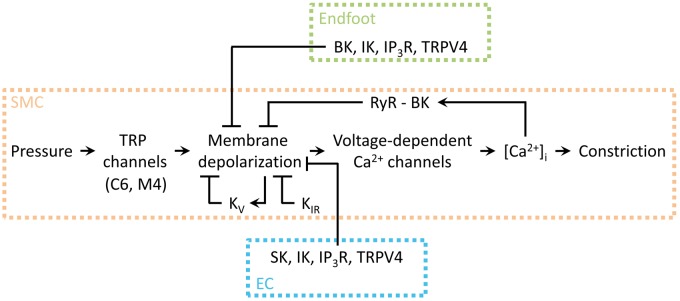

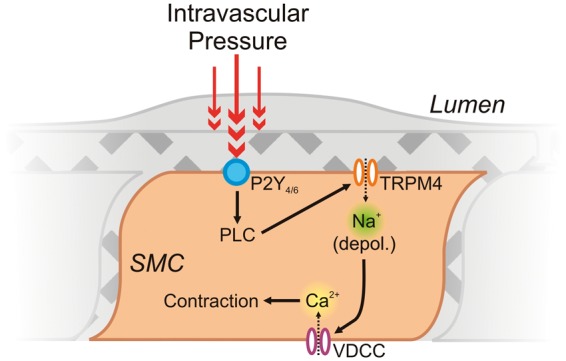

The studies described above were conducted using pial arteries. Recently, Li et al.20 pioneered the exploration of SM TRP channel contributions to myogenic tone in parenchymal arterioles. In keeping with their myogenic role in pial arteries, TRPM4 channels were found to be vitally important for the development of tone in isolated arterioles from this vascular bed. Here, TRPM4 activation and membrane depolarization lies downstream of direct mechanoactivation of purinergic P2Y4 and P2Y6 Gq-type G-protein coupled receptors (GqPCRs) and consequent stimulation of PLC activity by intravascular pressure,20,58,59 suggesting that mechanisms similar to those reported for pial arteries may also be at play in parenchymal arterioles (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

The central roles of SM TRPM4 channels and VDCCs in myogenic constriction of parenchymal arterioles. Intravascular pressure (∼40 mm Hg60) activates Gq-coupled P2Y receptors on the SM, leading to PLC activation. Through an as-yet-undefined pathway in parenchymal arterioles (see text for insights from pial arteries21), PLC activation leads to a depolarizing Na+ influx through TRPM4, triggering Ca2+ influx through VDCCs and leading to myocyte contraction.20

Ryanodine receptors in smooth muscle: Ca2+-release channels that oppose myogenic constriction

Although extracellular Ca2+ entry through VDCCs has a central role in the delivery of Ca2+ for SM contraction, Ca2+ release from the SR through RyRs has the opposite effect.61 Thus, Ca2+ in SM has a dichotomous role, with distinct Ca2+ signaling modalities either promoting or opposing vasoconstriction.

RyRs are homotetrameric assemblies located on the sarco-/endoplasmic reticulum (SR/ER) in many cell types. They are gated by Ca2+ and modulated by Mg2+, ATP, calmodulin and FK506-binding proteins as well as by phosphorylation by protein kinases such as protein kinase A (PKA), Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent kinase II and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG).62 Ca2+ release through RyRs can lead to two types of signal: waves and sparks. Ca2+ waves are propagating events with considerable spatial spread that result from Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release (CICR), a process whereby the presence of a sufficiently high concentration of local Ca2+ evokes Ca2+ release from nearby RyRs and/or IP3Rs in the SR membrane. This released Ca2+ then evokes further release from adjacent channels; the process repeats, leading to a regenerative Ca2+ wave that propagates along the SR. The role of Ca2+ waves in vascular SM is not fully understood, although waves in pial arteries may contribute to myogenic tone development, particularly at lower pressures.63 In contrast, Ca2+ sparks are highly localized, brief events mediated by the simultaneous opening of several clustered RyRs that cause local Ca2+ to reach micromolar concentrations.61,64,65 In pial artery SM, sparks occur at physiological pressures (60 mm Hg).66 In these vessels, and a range of other vascular beds, large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels are localized in the sarcolemma adjacent to SR RyR Ca2+ spark sites. These channels are activated by sparks, releasing K+ and resulting in a spontaneous transient outward current (STOC) that causes a brief hyperpolarization.61 In the pial circulation, this process acts as a negative feedback on membrane depolarization and Ca2+ entry through VDCCs61,67 and thus is an important determinant of arteriolar tone.

In contrast to pressurized pial arteries, where Ca2+ spark activity is a prominent feature, spark activity is absent in the SM of ex vivo pressurized (40 mm Hg) parenchymal arterioles; instead, asynchronous ryanodine-sensitive Ca2+ waves are the predominant form of Ca2+ signal here.14 However, the RyR Ca2+ spark-BK channel STOC signaling architecture is still present and can be engaged under certain circumstances,14 making this a potential target for neurovascular signaling mediators. Dabertrand and co-workers14 demonstrated this principle by acidifying artificial CSF from pH 7.4 to pH 7.0, which converted SM RyR-sensitive Ca2+ waves to sparks in parenchymal arterioles. The resultant increase in spark activity opposed pressure-induced vasoconstriction and led to a rapid and sustained vasodilation that was sensitive to both ryanodine and the BK channel blocker paxilline in a non-additive manner.14 It is presently unclear why Ca2+ sparks do not occur under basal (experimental) conditions in isolated parenchymal arterioles, but this observation may help to explain why these arterioles develop higher tone at lower pressures compared with pial arteries. Indeed, one possibility is that RyRs in parenchymal arterioles have a higher basal open probability than their counterparts in pial arteries.68 Such higher basal sensitivity to Ca2+ could lead to the preferential generation of waves rather than sparks in parenchymal arterioles, leaving an absence of the hyperpolarizing influence of spark-STOC signaling and higher tone. This contrasts with pial arteries, where basal spark-STOC signaling activity acts as a negative feedback that resists SM membrane depolarization, resulting in lower tone at the same pressure.

IP3 receptors

IP3Rs are ubiquitous ligand-gated Ca2+-permeable channels located in the membrane of the SR/ER.69 To date, IP3R signaling in parenchymal arteriole SM has not been examined, but in pial arteries, UTP-induced PLC activation has been linked to IP3R-dependent Ca2+ waves that lead to vasoconstriction.13 Moreover, Xi and co-workers identified a possible physical interaction of IP3Rs with TRPC3 in pial SM that was independent of SR Ca2+ release. The resultant cation current was demonstrated to promote vasoconstriction in response to endothelin-1.48 Since TRPC3 channels do not participate in pressure-induced constriction,70 this interaction might be important for receptor activation-induced constriction of cerebral arteries. As previously noted, pial SM IP3R activation leads to depolarizing TRPM4 currents.21 Since TRPM4 channels have a similar role in parenchymal arterioles,20 IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signaling is a likely candidate for mediating activation of TRPM4 channels here as well. IP3Rs are also involved in activation of the Ca2+-dependent transcription factor NFATc3 and subsequent regulation of pial SM gene expression.71

K+ channels in smooth muscle

The resting Vm of SM (−35 to −45 mV) indicates that the ratio of K+ permeability (pK) to the permeability of other ionic species (assuming a collective reversal potential of 0 mV) is around 0.5–0.8:1.26 Thus, the SM Vm is quite positive to the K+ equilibrium potential (EK), which is approximately −103 mV in CSF (assuming 3 mM extracellular K+ and 140 mM intracellular K+). These basal conditions mean that the activation of K+ channels can impart a major hyperpolarizing influence on cerebral SM, and thereby exert rapid and robust control over vascular diameter.

Smooth muscle inwardly rectifying K+ channels: Targets of endfoot K+ release

A modest elevation of external K+ is a rapid and powerful vasodilator of pial arteries and parenchymal arterioles.22,23 For example, raising K+ from 3 mM to 8 mM hyperpolarizes the SM in isolated pressurized parenchymal arterioles to near the new EK of −76 mV, and causes maximum vasodilation.22 For this to occur, K+ permeability has to increase more than 50-fold; this is achieved through activation of SM inwardly rectifying K+ (KIR) channels.26

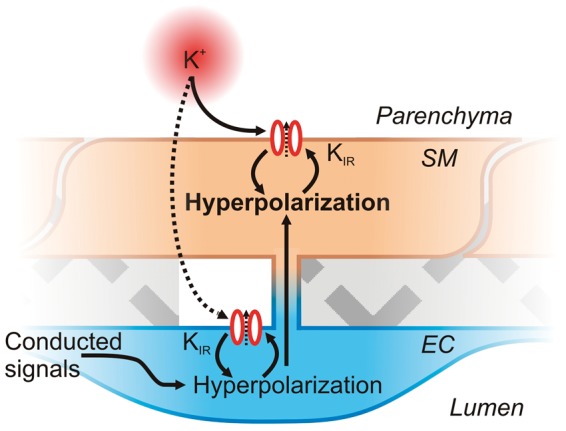

KIR channels, which form tetramers composed of two-transmembrane α-subunits, can be distinguished by their rectification properties.72 The KIR subtypes expressed in parenchymal arterioles have yet to be definitively established, but the pharmacological sensitivity of the parenchymal SM KIR current to Ba2+ ions in situ22,28 is consistent with the presence of functional KIR2-containing channels. In addition, mRNA data indicate the expression of KIR2.1 and KIR2.2 isoforms in rat parenchymal arterioles.28 In pial arteries, knockout of KIR2.1, but not KIR2.2, completely ablates the dilatory response of vessels to small increases in extracellular K+,29 suggesting a principal role for the KIR2.1 subtype. Furthermore, downregulation of SM KIR2.1 expression leads to impairment of K+-mediated dilation of rat parenchymal arterioles,28 strongly suggesting that KIR2.1 is of similar central importance in these smaller vessels. KIR2 family members are strongly rectifying and are activated by hyperpolarization and external K+, with their half-activation voltage corresponding to EK.73 At potentials positive to EK, outward K+ current through KIR channels progressively declines with depolarization as a result of intracellular polyamine block.74 As described previously, at basal extracellular K+ (3 mM), EK is approximately −103 mV and the SM Vm is about −35 to −40 mV.9,10 Under these conditions, KIR channel activity is very low.26 K+ is released from neurons and from endfoot BK channels during NVC (see below), and raising K+ by a small amount (e.g., to 8 mM) leads to rapid unblock of KIR channels and an enormous increase in KIR conductance.26 The ensuing increase in K+ permeability drives the SM Vm to the new EK (−76 mV with 8 mM [K+]o), in the process promoting even greater KIR channel activation by virtue of their steep voltage dependence.26 This ∼40 mV hyperpolarization closes VDCCs and leads to maximal vasodilation, making KIR activation by K+ released during neuronal activity a powerful mechanism for increasing local cerebral blood flow. The stark hyperpolarizing effect of K+ on parenchymal SM Vm likely also involves KIR channels located on the underlying endothelium, for which there exists preliminary evidence.26 Here, K+ may diffuse through the SM, or hyperpolarizing signals could be conducted upstream from capillaries (see below), to activate EC KIR channels. This would promote EC hyperpolarization which can be transmitted via gap junctions to reinforce SM hyperpolarization, further amplifying KIR channel activation and locking Vm at EK (Figure 4). For an extended discussion of K+-induced activation of parenchymal arteriole KIR channels in the control of cerebral blood flow, see Longden et al.26

Figure 4.

Feed-forward hyperpolarization of SMCs by KIR channel activation by K+ and Vm. A small amount of K+ released from neurons or astrocytes during neuronal activity may activate KIR channels on the SM and possibly also diffuse to KIR channels on ECs. Activation of KIR channels initiates membrane hyperpolarization, in the process promoting further KIR channel activation to amplify hyperpolarization and lead to Vm reaching EK. EC hyperpolarization, either due to K+ activation of KIR or resulting from conducted signaling from downstream capillaries, could also be transmitted to the SMs by gap junctions, further amplifying SMC hyperpolarization.

KIR subunits are also components of ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels, which are found in many peripheral vascular beds. KATP channels, composed of KIR6.1 or 6.2 with one of four types of auxiliary sulfonylurea (SUR) receptors, are weakly rectifying and their gating is determined by local concentrations of intracellular nucleotides.72 KATP channels composed of KIR6.1 and KIR6.2 plus SUR2B subunits are expressed in basilar and middle cerebral pial arteries75 and may play a role in the dilatory responses of large surface arterioles to hypoxia76 and acidosis.77 However, these channels appear to be absent from the SM of parenchymal arterioles, as evidenced by a lack of vasodilatory response to the KATP channel opener cromakalim.14

Ca2+-activated K+ channels: the hyperpolarizing influence of smooth muscle BK channel activity can be exploited by NVC mediators

The Ca2+-activated potassium (KCa) channel family is divided into three subgroups: small-conductance (SK) channels consisting of KCa2.1 (SK1), 2.2 (SK2) and 2.3 (SK3) isoforms, the intermediate-conductance (KCa3.1; IK) channel and the large conductance (KCa1.1; BK) channel.78 BK channel α-subunits possess six transmembrane domains with an extended intracellular C-terminus. These subunits gain their Ca2+-sensitivity from C-terminal regions, termed the Ca2+-bowl and the RCK (regulator of conductance for K+) domain. Four α-subunits associate with four β-subunits, the latter of which modulate the overall gating properties of the channel. α-subunits also possess a functional voltage sensor in their S4 region whose sensitivity is modified by local Ca2+ as well as by phosphorylation by a number of intracellular enzymes, making these channels responsive to a diverse range of intracellular stimuli.79

In line with observations in other vascular beds, parenchymal myocytes express functional BK channels, but do not express SK or IK channels.10 In contrast to their important role in opposing pressure-induced constriction in pial artery SM,67 BK channels contribute only modestly to parenchymal arteriolar tone.10 However, these channels represent a key target for many putative NVC mediators (e.g. EETs, nitric oxide and prostaglandins), which may harness BK channel activity to bring about membrane hyperpolarization.

KV channels exert a tonic hyperpolarizing influence on the smooth muscle membrane potential

Voltage-dependent potassium (KV) channels constitute the largest subfamily of the K+ channel superfamily.80 Functional channels are formed from four six-transmembrane α-subunits, either homo- or heteromeric, plus additional β-subunits.81 Rat parenchymal arterioles express mRNA for KV1.2 and KV1.5 α-subunits.25 Inhibiting KV channels in parenchymal arterioles causes a significant constriction, indicating that these channels provide a hyperpolarizing K+ efflux that opposes vasoconstriction at physiological pressures.25 Similarly, pial arteries express protein for KV1.2 and KV1.5 subtypes, which are thought to assemble into heterotetramers; these channels are tonically active in isolated pressurized pial arteries.82 Figure 5 provides an overview of the ion channel influences on SM Vm, the balance of which determines arteriolar tone at any given point.

Figure 5.

Schematic illustration of the central role of SM Vm in cerebrovascular constriction. Arrowheads indicate a stimulatory effect, whereas flat lines indicate a negative influence. TRP channel activity is engaged by pressure, which depolarizes the membrane and increases VDCC activity, leading to an increase in [Ca2+]i and constriction. Membrane depolarization directly stimulates KV channels, which mediate hyperpolarizing currents that, in turn, exert a negative feedback on depolarization; smooth muscle KIR channel activation also counteracts depolarization. Under certain conditions, elevated [Ca2+]i can induce RyR-mediated Ca2+ sparks, which couple to BK channels to hyperpolarize the membrane and limit depolarization. Astrocytic endfoot and endothelial signaling acts to hyperpolarize the SM membrane. The balance of these signaling elements controls Ca2+ entry into the myocyte and thus the contractile state of the cell. Adapted from Dabertrand et al.83

Part II: dual control of arteriolar smooth muscle by the endothelium and astrocytic endfeet

Both the endothelium and astrocytic endfeet share a number of common features that allow them to control Vm and the contractile state of the SM sandwiched between them. Each cell type exhibits local modulated Ca2+ signals, which lead to the release of a similar complement of vasoactive substances onto the SM. In keeping with this theme, astrocytes and ECs also express a highly similar repertoire of ion channel species.

The astrocyte cell membrane possesses a large passive K+ conductance and a negative resting potential, typically measured in the −70 to −80 mV range in brain slice electrophysiological recordings.84–86 One recent study using intracellular microelectrodes to record at the level of the astrocytic soma in vivo determined that the resting Vm was approximately −87 mV.7,8 Although parenchymal endothelial Vm has yet to be directly measured, dual microelectrode recordings from ECs and SM in hamster feed arteries showed that the Vm of these two cell types were very nearly equivalent.8 Moreover, measurements performed on peripheral arterioles using a range of preparations and techniques8,12,87–89 have established that endothelial resting Vm is between approximately −30 and – 45 mV. Thus, it is likely that parenchymal endothelial resting Vm lies within this range, closely matching that of the electrically connected overlying SM.

IP3Rs and TRPV4 play central roles in Ca2+ signaling in the endothelium and endfoot

In contrast to the RyR-mediated Ca2+ signaling that predominates in SM, Ca2+ release through IP3Rs has a key role in communication to the SM by both the parenchymal endothelium and astrocytic endfeet. Although the mechanisms by which extracellular Ca2+ ions enter the endothelium and endfoot remain unsettled, it is unlikely that VDCCs contribute to Ca2+ influx in either cell type. Instead, local Ca2+ entry through TRPV4 channels has been shown to be important in both ECs90 and astrocytes.16

IP3Rs

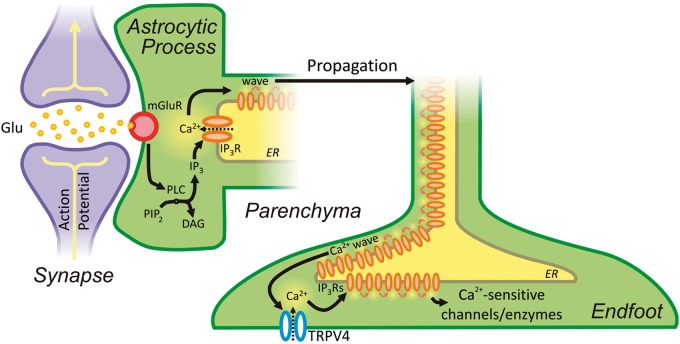

Astrocytes are equipped with a range of neurotransmitter receptors,91 enabling them to respond to a diverse array of neuronal signaling molecules. Glutamate is the predominant excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain, and the prevailing view is that astrocytes detect glutamatergic neuronal activity through Gq-coupled metabotropic glutamate receptors (mGluRs) expressed on processes that contact synapses.92 According to this model, activation of these GqPCRs causes the hydrolysis of phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) by PLC, resulting in the production of IP3 and DAG.93 IP3, in turn, acts on IP3Rs to increase their sensitivity to [Ca2+]i and increase Ca2+ efflux from the ER (Figure 6). The IP3R2 isoform is thought to be primarily responsible for the release of Ca2+ from astrocytic intracellular stores in hippocampal and cortical astrocytes, as some studies have observed that ablation of the gene encoding this channel attenuates GqPCR-stimulated and neuronal activity-evoked astrocytic Ca2+ signaling.94–96 Further studies, using IP3R2-knockout mice, have raised questions about the role of IP3R-mediated astrocytic Ca2+ signaling in the control of cerebral blood flow, reporting that functional hyperemia is unaffected in these mice.97,98 While these studies raise the intriguing possibility of IP3R2-independent NVC, their broader conclusion—that astrocytic Ca2+ signaling is dispensable for NVC and functional hyperemia—is premature and directly contradicts a substantial body of evidence to the contrary. For example, several laboratories have firmly established that uncaging Ca2+ or IP3 in astrocytic endfeet leads to diameter changes in the adjacent arteriole in brain slices and in vivo in both rats and mice.23,11,99–101 It should also be noted that retention of NVC upon IP3R2 knockout is not a universal finding95; a recent study of IP3R2-knockout mice using brain slices and in vivo preparations identified a diverse range of persistent astrocytic Ca2+ signaling events, localized mainly to fine processes and endfeet rather than somata.102 Further recent studies have confirmed that astrocytic, fast Ca2+ transients that occur in the cell soma, fine processes, and endfeet reliably precede functional hyperemia in adult mice in vivo.103,104 Thus, it appears that astrocytes from IP3R2-knockout mice do continue to engage in Ca2+ signaling, perhaps due to compensatory upregulation of other IP3R isoforms, likely on a spatial and temporal scale that previous studies were unable to detect.

Figure 6.

Neurovascular communication is initiated by neuronal activity, which drives the production of IP3 by PLC, in turn initiating a propagating Ca2+ wave. Ca2+ waves arriving at the endfoot activate TRPV4 channels in a positive-feedback loop that further enhances their spread, ultimately leading to the stimulation of Ca2+-sensitive ion channels and enzymes.

The astrocytic ER extends into the endfoot, as evidenced by the fact that both electrical field stimulation and direct photolysis of caged-IP3 evoke Ca2+ release in endfoot processes adjacent to arterioles.11 Thus, it is thought that the presence of sufficiently high concentrations of IP3 generated in response to neuronal activity evoke regenerative CICR, leading to a Ca2+ wave that propagates into the astrocytic endfoot.11 Arriving Ca2+ waves stimulate the production and/or release of numerous vasoactive molecules, which cause vasodilation and a resultant increase in local cerebral blood flow. Consistent with this, astrocytes in brain slices respond to electrical and pharmacological mGluR stimulation with an elevation in Ca2+.11,105–107 These findings, which were obtained in juvenile animals, are compatible with an interesting recent study reporting that expression of Gq-coupled mGluRs is prominent in cortical and hippocampal astrocytes of young mice but is lost in adulthood.107 However, the implication of this latter study—that expression of these receptors is a transient, developmental phenomenon—must be weighed against functional evidence that mGluR-mediated Ca2+ signaling in astrocytes is known to occur in adult animals in vivo.99,108 These seemingly irreconcilable observations suggest that the signaling cascade leading to astrocytic Ca2+ waves may be more complex than currently conceived—particularly in mature animals107—and indicate that further work is needed to fully understand this phenomenon.

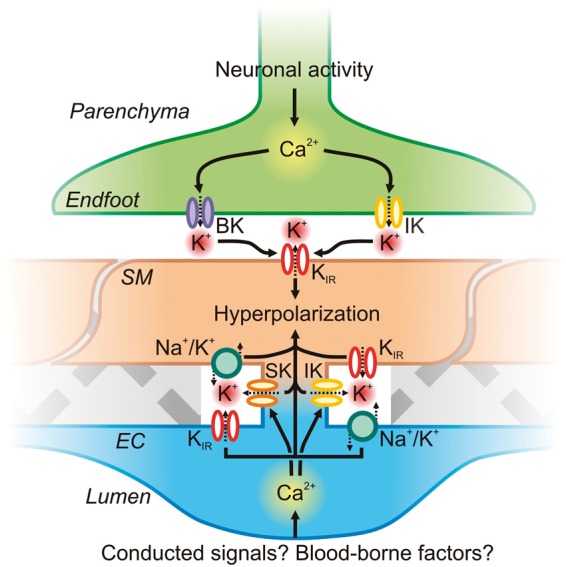

Given that the overlying SM acts as a barrier to immediate neuronal or astrocytic communication, it is unlikely that parenchymal arteriolar endothelium is directly stimulated during NVC. However, it is plausible that conducted signaling from capillary ECs (see below) could lead to parenchymal arteriole EC engagement.109 In ECs of small arteries of the periphery, Ca2+ release through IP3Rs is well-established as an important signaling step leading to vasodilation. In particular, brief, high-amplitude, IP3R-mediated Ca2+ signals localized specifically to MEP microdomains—termed Ca2+ pulsars—activate local IK channels, causing K+ efflux and hyperpolarization.12 This hyperpolarization can then be transmitted via gap junctions directly to the underlying SM; the released K+ may also amplify hyperpolarization by activating local KIR channels and/or Na+/K+ ATPase pumps on the endothelium and/or SM110 (Figure 7). Although currently unexplored, it is highly likely that this same signaling modality exists in parenchymal arteriole ECs, and if so, this could conceivably be engaged by conducted or blood-borne signals to further sculpt blood flow responses.

Figure 7.

Astrocytic endfoot and EC KCa channel influences on SM Vm. Astrocytic Ca2+ waves initiated by neuronal activity can activate BK and IK channels directly on the endfoot. K+ accumulates in the restricted extracellular space, activating SM KIR channels. Subsequent K+ efflux through these channels hyperpolarizes the SM membrane, which decreases VDCC open probability and thereby lowers global [Ca2+]i to promote vasorelaxation. On the luminal side of the SM, the endothelium may be engaged during neurovascular coupling (for example by conducted signaling from the capillary bed or by luminal factors such as altered shear), leading to an increase in EC Ca2+ that could engage IK and/or SK channels in MEP microdomains to drive EC membrane hyperpolarization and also raise local K+. EC membrane hyperpolarization could then be transmitted via gap junctions to the overlying SM. EC and SM KIR channels and Na+/K+ ATPase pumps could also respond to released K+ to amplify hyperpolarization.

TRPV4 channels

In addition to the well-studied IP3-mediated waves described above, recent evidence indicates that spatially restricted astrocytic Ca2+ signals are also vital for the astrocyte to carry out its diverse roles, including the control of cerebral blood flow. Several studies have identified TRPV4 channels in astrocytes.16,111 TRPV4 channels are enriched in astrocytic processes and endfeet adjacent to blood vessels and the glia limitans.111 Dunn et al.16 recently studied the contribution of TRPV4 signaling to endfoot Ca2+ handling during NVC. This study identified spatially restricted TRPV4-mediated Ca2+-entry events that couple to endfoot IP3Rs and then propagate throughout the endfoot as a Ca2+ wave16 (Figure 6). Inhibition of TRPV4 prior to neuronal stimulation was shown to substantially reduce the magnitude of the evoked endfoot Ca2+ transient, suggesting that TRPV4 is an important contributor to endfoot Ca2+ entry during neurovascular signaling. Although these channels can be activated by EETs, Dunn and co-workers found no evidence for EET-mediated activation of TRPV4 during neuronal activity. Instead, the authors proposed that IP3R-mediated Ca2+ release engages Ca2+-sensitive TRPV4 channels in the endfoot membrane, stimulating further Ca2+ entry into the cytosol to help propagate the wave. These data also raise the intriguing possibility of TRPV4 activation by local physical forces.55,112 For example, mechanical activation of TRPV4 by diameter changes in blood vessels could lead to endfoot Ca2+ increases that then either feedback to modulate vessel diameter and blood flow113 or propagate in retrograde fashion towards the astrocyte soma, where they might influence signaling to neurons.16,114

In ECs of mesenteric arteries, Ca2+-entry events mediated by the gating of individual TRPV4 channels—termed ‘TRPV4 sparklets’—act as powerful regulators of vascular tone.90 Here, endothelial Ca2+ entry though TRPV4 evoked by synthetic agonists primarily activates IK channels leading to vasodilation.90 In the cerebral circulation, TRPV4 channels have been identified in the endothelium of the isolated middle cerebral (pial) arteries, where they contribute to Ca2+ entry in response to stimulation of purinergic GqPCRs with UTP.17 Similarly, Hamel and co-workers18 recently confirmed the presence of functional TRPV4 channels in the endothelium of pressurized posterior cerebral (pial) arteries, showing that these channels link muscarinic receptor stimulation (with acetylcholine) to IK and SK channel activation. In the mesenteric endothelium, TRPV4 is co-localized with other signaling molecules at MEP sites,90 where cooperative gating among TRPV4 channels in a four-channel cluster is enhanced by localized concentrations of A-kinase anchoring protein (AKAP) 150.115 Similarly, TRPV4 is also found at MEPs in cremaster arterioles.116 This same clustered organization may also occur at MEPs in cerebral arteries/arterioles, a hypothesis supported by preliminary evidence.117 To date, TRPV4 expression and function have not been explored in the parenchymal endothelium, but given its importance in mesenteric and pial ECs, this channel is a likely candidate for mediating Ca2+ entry into ECs in parenchymal arterioles as well.

Expression of Ca2+ targets in astrocytic endfeet and the endothelium

KCa channels and K+ signaling: a mechanism for bi-directional control of parenchymal arteriole diameter

Among the key targets of endfoot Ca2+ increases are KCa channels. There is good evidence for the functional expression of BK channels in the endfoot membrane adjacent to underlying parenchymal arterioles.22,118 Astrocytes also express IK channels on processes and endfeet, whereas evidence for the functional expression of SK channels in astrocytes is currently lacking.24 During neurovascular communication, IP3-mediated Ca2+ waves arriving at the endfoot stimulate the opening of BK,22,23 and possibly IK,24 channels. K+ ions then accumulate in the extracellular nano-space between the endfoot and SM.22,23 This increase in local K+ concentration induces hyperpolarization and relaxation of the SM through activation of myocyte (and possibly endothelial26) KIR channels22 (Figure 7). In addition to being supported by in situ and in vivo experimental data,22,23 a number of the features of this mechanism have been confirmed using computational modeling.119–111

The magnitude of the neuronally evoked endfoot Ca2+ increase dictates relative BK channel activity and thus the concentration of K+ released into the nano-space between endfeet and arterioles. Notably, K+ can promote vasodilation or vasoconstriction depending on its concentration, inducing dilation at <20 mM through activation of KIR channels, and constriction at higher concentrations through depolarization of the SM and activation of VDCCs.23 Accordingly, the degree of Ca2+ elevation in the astrocytic endfoot is a vital determinant of the polarity of the vascular response. This was demonstrated in experiments showing that endfoot Ca2+ levels could be manipulated by varying the intensity of electrical field stimulation or by carefully controlling uncaging of Ca2+ directly in the endfoot. Ca2+ levels less than ∼500 nM consistently caused dilation, whereas higher concentrations induced constriction. Both dilations and constrictions were sensitive to block by paxilline, supporting a model in which K+ release through endfoot BK channels mediates both vasodilation and vasoconstriction, depending on the intensity of the stimulus.24

In contrast to astrocytic endfeet, the parenchymal endothelium expresses IK and SK channels, which contribute to basal parenchymal arteriole tone.10 SK and IK channels share a common topology, consisting of homomeric tetramers composed of four six-transmembrane α-subunits associated with intracellular Ca2+-binding calmodulin subunits at their C-terminal domains.79 This renders these channels exquisitely sensitive to changes in [Ca2+]i.122 Their vestigial voltage sensor, which contains fewer charged amino acids in the S4 transmembrane domain than that of KV channels, means that SK and IK channels are voltage-insensitive.123 Hannah et al.10 reported that blocking IK and SK channels in isolated pressurized parenchymal arterioles caused substantial vasoconstriction, and this same manipulation decreased resting cortical cerebral blood flow by 15% in vivo. Conversely, activation of these channels with NS309 maximally dilated isolated arterioles and greatly enhanced cortical cerebral blood flow, highlighting the role of these channels as powerful controllers of parenchymal arteriolar tone.10 In contrast, isolated, pressurized middle cerebral arteries do not constrict to IK and SK channel inhibition, suggesting that these channels are not tonically active under basal conditions in larger surface arteries.124 In mesenteric arteries, the SK3 subtype has been identified at MEPs and EC-EC borders.125 The loss of apamin-sensitive KCa currents in mesenteric ECs from an SK3 gene suppression mouse confirms that this is the primary SK isoform for the regulation of vascular tone.126 SK2 is also present in ECs, but appears to be restricted to peri-nuclear regions of the cell, whereas SK1 is not present.127

Engagement of SK and IK channels is dependent on [Ca2+]i; thus, the above observations suggest a level of tonic endothelial Ca2+ signaling in parenchymal arterioles in situ and in vivo. Extrapolating from mesenteric arteries, where IP3-mediated Ca2+ pulsars activate IK channels within MEPs12 and thereby contribute to the control of vascular tone, it is possible to suggest that this same signaling architecture is present in the parenchymal circulation. If further studies establish that this is the case, K+ released through IK and SK channel activation by Ca2+ pulsars would be predicted to couple to local KIR channel and Na+/K+ ATPase activation, which could act as an amplification mechanism to hyperpolarize the membrane and drive vasorelaxation110 (Figure 7).

Arachidonic acid metabolites

One early proposal128 was that neuronally evoked Ca2+ waves activate Ca2+-sensitive cytosolic phospholipase A2 in astrocytes, mobilizing arachidonic acid (AA) from membrane phospholipid pools and leading to subsequent metabolism of AA to EETs by cytochrome P450 2C11 enzymes. The four possible EET regioisomers—5,6-, 8,9-, 11,12- and 14,15-EET—act as short-range signaling hormones, dilating cerebral arteries in situ129 and contributing to the control of cerebral blood flow in vivo.130

EETs are synthesized by astrocytes in culture,131 and cytochrome P450 2C11 mRNA has been detected in perivascular astrocytes.130 Astrocyte-derived EETs could potentially act in either an autocrine or paracrine manner to open endfoot132 or SM133 BK channels, respectively. In the case of endfoot BK channels, this would cause the release of K+, which could then stimulate SM KIR channel activity.132 If EETs diffuse to the SM, they could open BK channels to hyperpolarize the membrane directly.133 The mechanism of EET action at BK channels involves ADP-ribosylation of Gsα subunits,134 resulting in an increase in channel activity.134 Astrocyte-derived EETs could also promote vasodilation through actions on TRPV4 channels in the endothelium,17,18 myocytes,19,49 and/or endfeet.16 Despite these possibilities, recent in vivo data argue against a direct contribution of endfoot-derived EETs to SM relaxation during NVC, as vasodilation evoked by uncaging Ca2+ directly in astrocytic endfeet in vivo was insensitive to cytochrome P450 blockade.99 These observations suggest that the mechanism underlying the contribution of astrocyte-derived EETs to NVC is more complex and indirect than was first envisioned.

AA liberated by PLA2 can also serve as a substrate for the production of vasoactive prostaglandins (PGs). In this reaction, the dual peroxidase-cyclooxygenase actions of cyclooxygenase (COX) enzymes initially metabolize AA to PGG2 followed by the rapid conversion of this intermediate to PGH2. PGH2 is metabolized by cytochrome P450 enzymes to a range of PG products. Of these, PGE2 has been proposed to play a role in NVC.105 In this model, PGE2 is liberated from the endfoot to act upon E-prostanoid (EP) receptors on SMCs. Notably, EP4 receptors are Gs-coupled GPCRs, and stimulation of these receptors leads to activation of PKA, which can produce vasodilation.135 However, recent studies have raised questions about the astrocytic involvement in the vasodilatory response to COX products. One group reported that COX-1 and -2 are expressed in astrocytes in juvenile rat hippocampal-neocortical slices and showed that pharmacological blockade of COX activity inhibited in situ vasodilations evoked by mGluR agonists and astrocyte Ca2+ uncaging.136 However, another group found that COX-1 mRNA was expressed in only 10% of rat cortical astrocytes, whereas COX-2 was absent.137 This same group recently identified a sub-population of COX-2 expressing pyramidal neurons as the primary cell type able to synthesize PGE2, which reportedly acts through Gs-coupled EP2 and EP4 receptors to produce hyperemia.137,138 However, a fundamental issue is raised by a recent study showing that application of PGE2 directly to isolated, pressurized parenchymal arterioles from both rat and mouse evoked constriction rather than dilation, through activation of EP1 receptors, suggesting that PGE2 is unlikely to act as a direct mediator of NVC on parenchymal arteriole smooth muscle.139 However, this does not rule out PGE2-mediated vasodilatory effects through indirect actions on neurons139 or on the capillary endothelium.

Liberation of AA from plasma membrane phospholipids by PLA2 also occurs in the endothelium. In contrast to astrocytes, the endothelium has been clearly demonstrated to possess abundant COX-1 and PGI2 synthase enzymes.140 PGI2 derived from the activities of these enzymes is the primary vasodilatory PG liberated from the endothelium in response to a variety of stimuli, including agonists of muscarinic, bradykinin and purinergic receptors.141,142 Similar to the actions of PGE2 on EP receptors, PGI2 activates Gs-coupled I prostanoid receptors on SMCs, evoking PKA-mediated vasodilation.140 Although, PGI2 and its analogues do relax cerebral arteries and arterioles,143 preliminary evidence from mouse brain slices suggests that PGI2 is not involved in signaling during NVC.144

The parenchymal endothelium is also a likely source of EETs, as ECs produce these molecules in a range of vascular beds.145,146 Moreover, cerebral arteries and arterioles dilate in response to direct EET application.129,147 However, to our knowledge, the endothelial production of these molecules has yet to be directly investigated in parenchymal arterioles. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to speculate that endothelial EETs could influence blood flow by interacting with a range of ion channels in the parenchymal NVU, such as myocyte10 or astrocytic22,132 BK channels or endothelial,17,18 SM49,19 and astrocytic16 TRPV4 channels. EET-mediated Ca2+ influx through endothelial TRP channels148 could also contribute to endothelial SK and IK channel activation and membrane hyperpolarization.

Nitric oxide: NVC mediator or modulator?

Another commonly touted Ca2+-dependent NVC mediator is nitric oxide (NO). However, the potential contribution of NO is complex and its actual role remains uncertain. NO derived from both neuronal and endothelial sources has been implicated in the control of cerebral blood flow,149–151 whereas it is generally accepted that astrocytes do not generate NO under normal conditions. NO activates guanylate cyclase, leading to the production of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP).152 Cyclic GMP, in turn, is a substrate for PKG, which interacts with multiple downstream effectors. Considering ion channel targets alone, PKG activity can modulate the phosphorylation status of BK channels, leading to an increase in their activity,153,154 and may act through similar mechanisms to inhibit VDCCs.155 Cyclic GMP can increase RyR-mediated Ca2+ spark frequency,57 and NO may also decrease IP3-mediated Ca2+ release through the actions of cGMP and PKG.156 In the parenchymal NVU, NO from either eNOS or nNOS could interact with guanylate cyclase in both astrocytes157 and SM158 to increase the activity of BK channels in these respective cell types. Signaling to SM VDCCs or RyRs would also be predicted to promote vasodilation and increased blood flow. Moreover, because NO-cGMP-PKG signaling has been reported to inhibit TRPV4 channels (alone159 or when complexed with TRPC1160 or TRPP2161), endothelial and endfoot Ca2+ signaling could also be affected.

Recent work has identified a contribution of eNOS signaling to resting tone in isolated pressurized middle cerebral arteries and parenchymal arterioles,124 but whether NO is actively recruited during NVC is controversial.149,162,163 However, emerging evidence supports the concept of endothelial engagement during NVC through the release of parenchymal factors that increase eNOS activity.164,165 A study by LeMaistre-Stobart and co-workers165 reported that astrocytic release of D-serine, in combination with glutamate, may activate endothelial N-methyl D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors, which conduct Na+ and Ca2+ into the cell. This could then stimulate eNOS, increasing the production of NO and causing vasodilation of arterioles through the actions of NO on the adjacent SMCs.165 In support of this model, this same group previously demonstrated that endothelial NMDA-receptor activation dilates isolated middle cerebral arteries and brain slice parenchymal arterioles through an eNOS-dependent mechanism.164 However, the functional expression of NMDA receptors in native parenchymal endothelium is yet to be confirmed.

The next frontier: what are the roles of capillary EC and pericyte ion channels in the control of blood flow in the brain microcirculation?

Capillaries vastly outnumber parenchymal arterioles and are intimately associated with neurons and astrocytes, and are also covered by pericytes. Approximately 90% of capillaries have pericytes,166 which cover an estimated 37% of the endothelial surface area.167 This angioarchitecture suggests that capillary ECs and pericytes play an important role in communicating neuronal activity from the capillary bed to upstream arterioles to modulate blood flow into the deep microcirculation. Indeed, recent work from the Attwell laboratory, conducted in brain slices and in vivo, suggested that hyperemia is initiated at the level of pericytes before being conducted upstream to arterioles.168 These authors demonstrated that brain capillary pericytes are capable of both contraction (in response to noradrenaline) and relaxation in response to exogenous agonists and—importantly—neuronal activity.168,169 Of particular note, glutamate, NMDA or neuronal stimulation evoked a ∼30 pA hyperpolarizing current in pericytes patch-clamped in situ, thought to underlie pericyte relaxation. The ion channel mediating this hyperpolarization was not firmly identified, although the authors suggest it is highly likely to conduct K+.168 Interestingly, only 25–30% of brain pericytes respond to contractile stimuli,169 suggesting a sub-population of non-contractile pericytes.

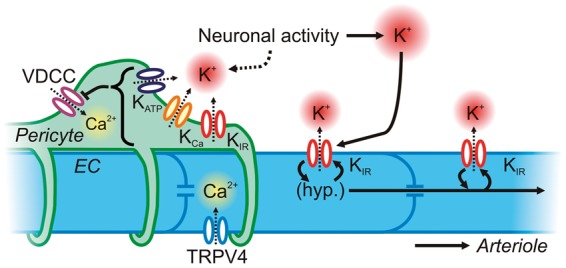

To date ion channel expression and function have not been well explored in brain pericytes, but more is known about retinal pericytes. Relevant in this context, retinal pericytes are known to possess VDCCs,170,171 endowing them with an avenue through which Vm changes can modulate intracellular Ca2+ and adjust the contractile state of the cell. Retinal pericytes also possess KIR channels,172 KCa (BK and SK) channels173,174 and, in contrast to parenchymal SM, KATP channels.175 If this complement of K+ channels is also present in brain pericytes, they could be harnessed by a variety of signaling pathways – for example external K+ activation of KIR channels – to produce membrane hyperpolarization and relaxation in response to neuronal activity, thereby modulating capillary blood flow (Figure 8). Notably, the ion channel expression profiles of contractile and non-contractile pericytes are likely to differ substantially, reflecting different roles for each subclass of pericytes—an area that requires further exploration. Readers are directed to Hamilton et al.176 for a more comprehensive review of the literature on pericyte ion channel expression and function.

Figure 8.

Neurovascular communication at the capillary level. Capillary ECs possess KIR and TRPV4 channels, which can hyperpolarize the membrane and allow Ca2+ into the cytosol, respectively. KIR channels may endow capillary ECs with the ability to sense K+ released by neuronal activity and to conduct a regenerative, retrograde hyperpolarization by virtue of the voltage-dependence of KIR channels. This will lead to rapid upstream dilation of parenchymal arterioles and pial arteries. Pericytes cover more than one-third of the capillary surface area and express VDCCs as a major pathway for the delivery of Ca2+ for contraction. They also express KATP, KCa and KIR channels, which could be recruited through various mechanisms triggered by neuronal activity to drive membrane hyperpolarization and induce pericyte relaxation. Collectively, ion channels in both ECs and pericytes may provide the means to finely control blood flow deep within the vascular tree.

Less still is known about native ion channels functionally expressed in brain capillary ECs, but preliminary work indicates that these cells possess both KIR and TRPV4 channels, but unexpectedly lack SK and IK channels and KATP channels.177 This repertoire, although incompletely characterized, equips capillaries with a molecular toolkit for detecting local changes in K+ concentration during neuronal activity and responding with robust hyperpolarization; it also provides a pathway for the elevation of intracellular Ca2+. Membrane hyperpolarization and propagating intercellular Ca2+ waves are prominent features of conducted signaling along arterioles,178 which is primarily enabled by the endothelial lining.179 Therefore, capillary KIR and TRPV4 channels may endow capillaries with the ability to rapidly communicate to upstream arterioles and pericytes—indeed the endothelium has been suggested as an efficient electrical pathway linking pericytes in the retina180—to finely tune blood flow in the deep microcirculation (Figure 8).

Conclusion

The cells of the NVU express a diverse array of ion channels that engage in intra- and intercellular signaling to control the diameter of parenchymal arterioles and modulate cerebral blood flow. There are close similarities in ion channel expression and function between astrocytic endfeet and ECs, leading to parallels in the signaling mechanisms employed by both cell types to control SM Vm, vascular tone and blood flow. Any defect—for example the accumulation of perivascular deposits such as occurs in Alzheimer’s disease or CADASIL6—could impair ion channel signaling during NVC. As the field progresses and the roles of ion channel signaling in the control of cerebral blood flow are more clearly defined, future studies will likely establish NVU ion channel dysregulation and NVC impairment as important mechanisms in a broad range of cerebrovascular disease states.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge Drs. F Dabertrand, T Dalsgaard, A Gonzales and N Villalba for insightful discussions.

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article:

This work was supported by the American Heart Association (TAL, award IDs: 12POST12090001, 14POST20480144), the Totman Medical Research Trust (MTN), Fondation Leducq (MTN), and National Institutes of Health (P20-RR-16435, P01-HL-095488, R01-HL-121706, R37-DK-053832 to MTN).

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.Roy CS, Sherrington CS. On the regulation of the blood-supply of the brain. J Physiol 1890; 11: 85–158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Brien JT, Eagger S, Syed GM, et al. A study of regional cerebral blood flow and cognitive performance in Alzheimer's disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 1992; 55: 1182–1187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jennings JR, Muldoon MF, Ryan C, et al. Reduced cerebral blood flow response and compensation among patients with untreated hypertension. Neurology 2005; 64: 1358–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prunell GF, Mathiesen T, Svendgaard N-A. Experimental subarachnoid hemorrhage: cerebral blood flow and brain metabolism during the acute phase in three different models in the rat. Neurosurgery 2004; 54: 426–437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dandona P, James IM, Newbury PA, et al. Cerebral blood flow in diabetes mellitus: evidence of abnormal cerebrovascular reactivity. Br Med J 1978; 2: 325–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chabriat H, Joutel A, Dichgans M, et al. CADASIL. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 643–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mishima T, Hirase H. In vivo intracellular recording suggests that gray matter astrocytes in mature cerebral cortex and hippocampus are electrophysiologically homogeneous. J Neurosci 2010; 30: 3093–3100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emerson GG, Segal SS. Electrical coupling between endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells in hamster feed arteries: role in vasomotor control. Circ Res 2000; 87: 474–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nystoriak MA, O'Connor KP, Sonkusare SK, et al. Fundamental increase in pressure-dependent constriction of brain parenchymal arterioles from subarachnoid hemorrhage model rats due to membrane depolarization. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2011; 300: H803–812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hannah RM, Dunn KM, Bonev AD, et al. Endothelial SKCa and IKCa channels regulate brain parenchymal arteriolar diameter and cortical cerebral blood flow. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 21: 69–78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Straub SV, Bonev AD, Wilkerson MK, et al. Dynamic inositol trisphosphate-mediated calcium signals within astrocytic endfeet underlie vasodilation of cerebral arterioles. J Gen Physiol 2006; 128: 659–669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ledoux J, Taylor MS, Bonev AD, et al. Functional architecture of inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate signaling in restricted spaces of myoendothelial projections. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2008; 105: 9627–9632. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao G, Adebiyi A, Blaskova E, et al. Type 1 inositol 1,4,5-trisphosphate receptors mediate UTP-induced cation currents, Ca2+ signals, and vasoconstriction in cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2008; 295: C1376–1384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dabertrand F, Nelson MT, Brayden JE. Acidosis dilates brain parenchymal arterioles by conversion of calcium waves to sparks to activate BK channels. Circ Res 2012; 110: 285–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Filosa JA, Bonev AD, Nelson MT. Calcium dynamics in cortical astrocytes and arterioles during neurovascular coupling. Circ Res 2004; 95: e73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dunn KM, Hill-Eubanks DC, Liedtke WB, et al. TRPV4 channels stimulate Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release in astrocytic endfeet and amplify neurovascular coupling responses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013; 110: 6157–6162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marrelli SP, O'neil RG, Brown RC, et al. PLA2 and TRPV4 channels regulate endothelial calcium in cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2007; 292: H1390–1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang L, Papadopoulos P, Hamel E. Endothelial TRPV4 channels mediate dilation of cerebral arteries: impairment and recovery in cerebrovascular pathologies related to Alzheimer disease. Br J Pharmacol 2013; 170: 661–670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Baylie RL, Tavares M, Navedo M, et al. The role of TRPV4 in rat parenchymal arterioles. FASEB J 2010. 1033.2 (abstract). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Baylie RL, Tavares MJ, et al. TRPM4 channels couple purinergic receptor mechanoactivation and myogenic tone development in cerebral parenchymal arterioles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2014; 34: 1706–1714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gonzales AL, Yang Y, Sullivan MN, et al. A PLCγ1-dependent, force-sensitive signaling network in the myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries. Sci Signal 2014; 7: ra49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Filosa JA, Bonev AD, Straub SV, et al. Local potassium signaling couples neuronal activity to vasodilation in the brain. Nat Neurosci 2006; 9: 1397–1403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Girouard H, Bonev AD, Hannah RM, et al. Astrocytic endfoot Ca2+ and BK channels determine both arteriolar dilation and constriction. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2010; 107: 3811–3816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Longden TA, Dunn KM, Draheim HJ, et al. Intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium channels participate in neurovascular coupling. Br J Pharmacol 2011; 164: 922–933. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Straub SV, Girouard H, Doetsch PE, et al. Regulation of intracerebral arteriolar tone by Kv channels: effects of glucose and PKC. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2009; 297: C788–796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Longden TA, Nelson MT. Vascular inward rectifier K+ channels as external K+ sensors in the control of cerebral blood flow. Microcirculation 2015; 22: 183–196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Crane GJ, Walker SD, Dora KA, et al. Evidence for a differential cellular distribution of inward rectifier K channels in the rat isolated mesenteric artery. J Vasc Res 2003; 40: 159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Longden TA, Dabertrand F, Hill-Eubanks DC, et al. Stress-induced glucocorticoid signaling remodels neurovascular coupling through impairment of cerebrovascular inwardly rectifying K+ channel function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014; 111: 7462–7467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zaritsky JJ, Eckman DM, Wellman GC, et al. Targeted disruption of Kir2.1 and Kir2.2 genes reveals the essential role of the inwardly rectifying K+ current in K+-mediated vasodilation. Circ Res 2000; 87: 160–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cipolla MJ. The cerebral circulation, San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Simard M, Arcuino G, Takano T, et al. Signaling at the gliovascular interface. J Neurosci 2003; 23: 9254–9262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nishimura N, Schaffer CB, Friedman B, et al. Penetrating arterioles are a bottleneck in the perfusion of neocortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2007; 104: 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Aydin F, Rosenblum WI, Povlishock JT. Myoendothelial junctions in human brain arterioles. Stroke 1991; 22: 1592–1597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Iliff JJ, Wang M, Liao Y, et al. A paravascular pathway facilitates CSF flow through the brain parenchyma and the clearance of interstitial solutes, including Amyloid β. Sci Transl Med 2012; 4: 147ra111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Brown PD, Davies SL, Speake T, et al. Molecular mechanisms of cerebrospinal fluid production. Neuroscience 2004; 129: 955–968. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Knot HJ, Nelson MT. Regulation of arterial diameter and wall [Ca2+] in cerebral arteries of rat by membrane potential and intravascular pressure. J Physiol 1998; 508: 199–209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bayliss WM. On the local reactions of the arterial wall to changes of internal pressure. J Physiol 1902; 28: 220–231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nelson MT, Patlak JB, Worley JF, et al. Calcium channels, potassium channels, and voltage dependence of arterial smooth muscle tone. Am J Physiol 1990; 259: C3–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Catterall WA. Structure and regulation of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol 2000; 16: 521–555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kuo IY, Ellis A, Seymour VA, et al. Dihydropyridine-insensitive calcium currents contribute to function of small cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2010; 30: 1226–1239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abd El-Rahman RR, Harraz OF, Brett SE, et al. Identification of L- and T-type Ca2+ channels in rat cerebral arteries: role in myogenic tone development. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2013; 304: H58–H71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nelson MT, Quayle JM. Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 1995; 268: C799–C822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brayden JE, Earley S, Nelson MT, et al. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, vascular tone and autoregulation of cerebral blood flow. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2008; 35: 1116–1120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ramsey IS, Delling M, Clapham DE. An introduction to TRP channels. Annu Rev Physiol 2006; 68: 619–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Earley S, Brayden JE. Transient receptor potential channels in the vasculature. Physiol Rev 2015; 95: 645–690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Earley S, Waldron BJ, Brayden JE. Critical role for transient receptor potential channel TRPM4 in myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries. Circ Res 2004; 95: 922–929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Welsh DG, Morielli AD, Nelson MT, et al. Transient receptor potential channels regulate myogenic tone of resistance arteries. Circ Res 2002; 90: 248–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xi Q, Adebiyi A, Zhao G, et al. IP3 constricts cerebral arteries via IP3 receptor–mediated TRPC3 channel activation and independently of sarcoplasmic reticulum Ca2+ release. Circ Res 2008; 102: 1118–1126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Earley S, Heppner TJ, Nelson MT, et al. TRPV4 forms a novel Ca2+ signaling complex with ryanodine receptors and BKCa channels. Circ Res 2005; 97: 1270–1279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gonzales AL, Amberg GC, Earley S. Ca2+ release from the sarcoplasmic reticulum is required for sustained TRPM4 activity in cerebral artery smooth muscle cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2010; 299: C279–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Gonzales AL, Garcia ZI, Amberg GC, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of TRPM4 hyperpolarizes vascular smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 2010; 299: C1195–1202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dietrich A, Gudermann T. TRPC6. In: Flockerzi V, Nilius B. (eds). Transient receptor potential (TRP) channels, Heidelberg: Springer, 2007, pp. 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Maroto R, Raso A, Wood TG, et al. TRPC1 forms the stretch-activated cation channel in vertebrate cells. Nat Cell Biol 2005; 7: 179–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Becker D, Bereiter-Hahn J, Jendrach M. Functional interaction of the cation channel transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) and actin in volume regulation. Eur J Cell Biol 2009; 88: 141–152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Köhler R, Heyken WT, Heinau P, et al. Evidence for a functional role of endothelial transient receptor potential V4 in shear stress-induced vasodilatation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 2006; 26: 1495–1502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hill-Eubanks DC, Gonzales AL, Sonkusare SK, et al. Vascular TRP Channels: Performing Under Pressure and Going with the Flow. Physiology 2014; 29: 343–360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Porter VA, Bonev AD, Knot HJ, et al. Frequency modulation of Ca2+ sparks is involved in regulation of arterial diameter by cyclic nucleotides. Am J Physiol 1998; 274: C1346–1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Brayden JE, Li Y, Tavares MJ. Purinergic receptors regulate myogenic tone in cerebral parenchymal arterioles. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 2013; 33: 293–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nicholas RA, Watt WC, Lazarowski ER, et al. Uridine nucleotide selectivity of three phospholipase C-activating P2 receptors: identification of a UDP-selective, a UTP-selective, and an ATP- and UTP-specific receptor. Mol Pharmacol 1996; 50: 224–229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Baumbach GL, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Cerebral arteriolar structure in mice overexpressing human renin and angiotensinogen. Hypertension 2003; 41: 50–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Nelson MT, Cheng H, Rubart M, et al. Relaxation of arterial smooth muscle by calcium sparks. Science 1995; 270: 633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]