Introduction

In a change from longstanding practice, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) recently began suppressing substance abuse-related claims in the Medicare and Medicaid Research Identifiable Files.1,2 This change was enacted to comply with a decades-old federal regulation barring third party payers from releasing information from federally funded substance abuse treatment programs without patient consent.3

CMS removes any claim containing a diagnostic or procedure code related to substance abuse, meaning that the entire encounter captured by the claim is deleted (including all diagnosis and procedure codes).1,4 Therefore, important diagnoses linked to substance abuse might also be suppressed.

We examined the association between implementation of the CMS suppression policy and rates of diagnoses for non-substance abuse conditions in Medicaid data.

Methods

We received Medicaid data for 2000-2006 prior to implementation of the suppression policy (i.e. containing substance abuse codes) and data for 2007-2010 after the policy was enacted, allowing comparison of data without vs with claim suppression. Use of this de-identified database was approved by Partners Institutional Review Board and the need for informed consent was waived.

Based on all diagnosis fields for ICD-9 CM codes, we calculated annual inpatient and outpatient rates (per 100,000 patients utilizing inpatient and outpatient services, respectively) of diagnoses for 6 conditions that commonly co-occur with substance abuse (hepatitis C, human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], cirrhosis, tobacco use, depression, anxiety) and 4 conditions unrelated to substance abuse (type II diabetes, stroke, hypertension, kidney disease).

Segmented linear regression models allowing for first-order autocorrelation were used to test for changes in the rate of each condition in the years after suppression was implemented. Models included a term for the baseline trend (2000-2006) and terms to estimate changes in level and trend after implementation of suppression procedures (2007-2010). For each parameter, 95% Confidence Intervals (CI) were calculated and a 2-sided Wald test was conducted. P-values <0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Analyses were performed in SAS v9.4 (SAS Institute Inc.).

Results

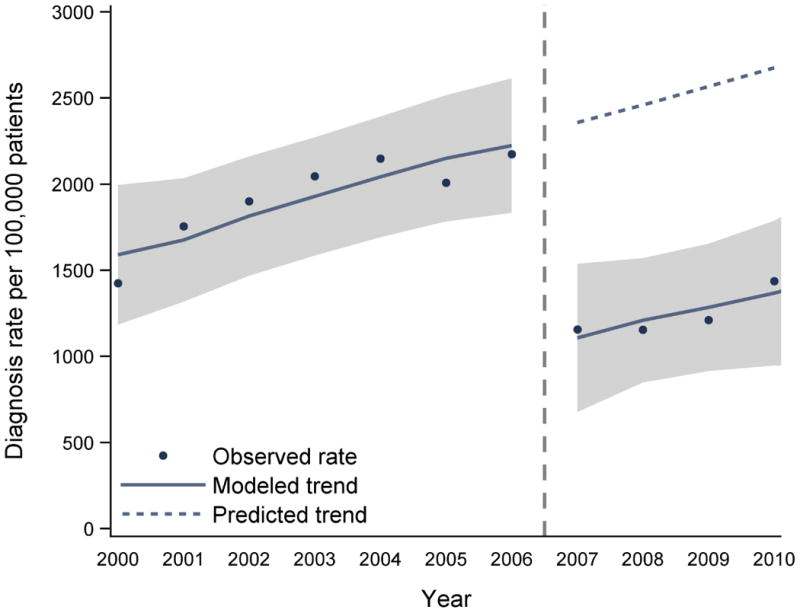

Over the 11-year study, there were 63 million inpatient and 13.6 billion outpatient claims. For inpatient diagnoses, regression models showed a statistically significant negative level change (i.e., immediate reduction in the first year affected by suppression) for conditions commonly co-occurring with substance abuse (Table). Relative to rates observed in 2006, there was an immediate reduction in the 2007 inpatient diagnosis rates (per 100,000 patients) of 56.7% for hepatitis C (-1,233 [95% CI -1,588 to -908]; p<0.001) (displayed in Figure), 51.3% for tobacco use (-5,015 [-6,073 to -3,957]; p<0.001), 48.9% for cirrhosis (-675 [-864 to -486]; p<0.001), 38.4% for depression (-2,712 [-4,377 to -1,047]; p=0.02), 26.6% for anxiety (-795 [-1,220 to -371]; p=0.01), and 24.0% for HIV (-498 [-665 to -330]; p<0.001).

Table. Annual rates of diagnoses per 100,000 patients for selected conditions in Medicaid before and after suppression of substance abuse claims and results of segmented linear regression analysis.

| Inpatient diagnoses | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rates of diagnosesc | Model results | |||||||||||

| 2000 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | Level changee | 95% CI | p-value | Trend changef | 95% CI | p-value | |||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Related conditionsa | ||||||||||||

| Hepatitis C | 1,424 | 2,173 | 1,156 | 1,437 | -1,233 | -1,558 | -908 | < 0.001 | -21 | -157 | 114 | 0.77 |

| HIV | 3,058 | 2,076 | 1,254 | 1,428 | -498 | -665 | -330 | < 0.001 | 204 | 136 | 273 | < 0.001 |

| Cirrhosis | 1,362 | 1,381 | 779 | 894 | -675 | -864 | -486 | < 0.001 | 38 | -39 | 114 | 0.37 |

| Tobacco use | 5,274 | 9,768 | 5,872 | 8,735 | -5,015 | -6,073 | -3,957 | < 0.001 | 165 | -233 | 564 | 0.45 |

| Depression | 6,795 | 7,068 | 4,668 | 6,677 | -2,712 | -4,377 | -1,047 | 0.02 | 615 | -70 | 1,301 | 0.13 |

| Anxiety | 2,301 | 2,991 | 2,344 | 3,522 | -795 | -1,220 | -371 | 0.01 | 281 | 107 | 456 | 0.02 |

| Unrelated conditionsb | ||||||||||||

| Type II diabetes | 6,069 | 7,864 | 7,266 | 9,946 | -1,012 | -2,175 | 151 | 0.14 | 556 | 92 | 1,021 | 0.06 |

| Stroke | 1,088 | 884 | 885 | 1,250 | 71 | -58 | 199 | 0.32 | 144 | 93 | 195 | 0.002 |

| Hypertension | 11,531 | 13,534 | 11,864 | 16,726 | -2,193 | -4,343 | -43 | 0.09 | 1,251 | 392 | 2,110 | 0.03 |

| Kidney disease | 3,923 | 4,904 | 4,937 | 7,959 | -37 | -697 | 623 | 0.92 | 817 | 551 | 1,082 | < 0.001 |

|

|

||||||||||||

| Outpatient diagnoses | ||||||||||||

| Rates of diagnosesd | Model results | |||||||||||

| 2000 | 2006 | 2007 | 2010 | Level changee | 95% CI | p-value | Trend changef | 95% CI | p-value | |||

|

|

||||||||||||

| Related conditionsa | ||||||||||||

| Hepatitis C | 2,206 | 3,080 | 2,912 | 3,686 | -463 | -1,464 | 538 | 0.33 | 90 | -313 | 492 | 0.68 |

| HIV | 9,937 | 9,439 | 8,753 | 9,392 | -470 | -1,561 | 621 | 0.42 | 340 | -100 | 781 | 0.16 |

| Cirrhosis | 1,470 | 1,591 | 1,518 | 2,114 | -99 | -324 | 127 | 0.42 | 193 | 103 | 283 | 0.005 |

| Tobacco use | 1,510 | 3,807 | 4,105 | 7,384 | -5 | -271 | 261 | 0.97 | 809 | 683 | 936 | < 0.001 |

| Depression | 48,282 | 45,220 | 40,574 | 48,941 | -4,846 | -9,852 | 160 | 0.10 | 3,652 | 1,670 | 5,634 | 0.01 |

| Anxiety | 32,145 | 40,044 | 38,520 | 47,051 | -2,512 | -4,811 | -213 | 0.02 | 1,654 | 886 | 2,422 | 0.004 |

| Unrelated conditionsb | ||||||||||||

| Type II diabetes | 23,875 | 32,231 | 32,488 | 46,598 | 350 | -3,053 | 3,752 | 0.85 | 3,661 | 2,309 | 5,013 | 0.002 |

| Stroke | 5,569 | 4,420 | 4,445 | 5,937 | 577 | -210 | 1,363 | 0.20 | 725 | 412 | 1,039 | 0.004 |

| Hypertension | 26,337 | 32,180 | 32,308 | 47,917 | 499 | -3,842 | 4,841 | 0.83 | 4,549 | 2,797 | 6,301 | 0.002 |

| Kidney disease | 16,411 | 17,998 | 18,741 | 26,924 | 1,250 | -1,408 | 3,908 | 0.39 | 2,660 | 1,599 | 3,721 | 0.003 |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus

‘Related conditions’ are known to commonly co-occur with substance abuse disorders

‘Unrelated conditions’ are thought to be less directly related to substance abuse disorders

Estimated as number of inpatient diagnoses per 100,000 patients utilizing inpatient services

Estimated as number of outpatient diagnoses per 100,000 patients utilizing outpatient services

‘Level change’ is the instantaneous change in the baseline trend in the first year affected by suppression (2007)

‘Trend change’ is the change in annual trend of the diagnosis rate in the years affected by suppression (2007-2010).

Figure. Rate of inpatient Hepatitis C diagnoses and segmented linear regression results before and after CMS suppression.

Abbreviations: CMS, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

Note: the ‘predicted trend’ is the projected rate of diagnoses in the absence of the CMS suppression procedures, based on a continuation of the baseline trend.

Reductions in outpatient diagnosis rates were less pronounced. While all conditions that commonly co-occur with substance abuse had a negative level change, this decrease was only statistically significant for anxiety, with a 6.3% reduction (-2512 [-4,811 to -213]; p=0.02).

Discussion

Conditions unrelated to substance abuse appeared generally unassociated with CMS' suppression practices. However, implementation of the policy coincided with sudden and substantial decreases in the rates of inpatient diagnoses for conditions commonly co-occurring with substance abuse, while only anxiety showed significant reductions in outpatient diagnosis rates.

Underestimation of diagnoses has the potential to bias health services research studies and epidemiological analyses where affected conditions are outcomes or confounders. In studies of healthcare utilization, the number of missing claims may vary in a non-random fashion between groups defined by demographics, disease, or locality. Comparisons between groups may lead to spurious conclusions - a hospital that regularly admits substance abusers will have artificially low rates of re-admission, giving a false appearance of better performance.

A potential limitation is that the observations are susceptible to influence from secular trends, including changes in Medicaid eligibility, coding practices, or the true underlying prevalence of the medical conditions. However, the marked, immediate decline in inpatient rates of comorbidities related to substance abuse following the beginning of the suppression period suggests that our findings were likely the result of CMS' suppression policies.

Acknowledgments

Non-author contributions: The authors would like to thank Helen Mogun, MS (Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics, Brigham and Women's Hospital) for preparing the analytic datasets for this study and Cora Allen-Coleman, BA (Department of Statistics, University of Wisconsin-Madison) for her assistance in creating the Figure. As employees of the Division of Pharmacoepidemiology and Pharmacoeconomics at the time of the study conduct, both individuals were compensated for their work on the manuscript.

Funding/support: Kathryn Rough and Yoonyoung Park were supported by training grants from the Pharmacoepidemiology Program at the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Kathryn Rough was also supported by grant T32 AI007433 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Krista Huybrechts was supported by a career development grant K01MH099141 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Sonia Hernandez-Diaz was supported by R01MH100216 from the National Institute of Mental Health. Brian Bateman was supported by a career development grant K08HD075831 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development.

Footnotes

Author contributions: Kathryn Rough had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis.

Study concept and design: Rough, Bateman, Hernandez-Diaz, Huybrechts

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors

Statistical analysis: Rough, Park

Drafting the manuscript: Rough, Bateman

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors

Conflict of interest disclosures: The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Role of funding/sponsor: The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

References

- 1.Frakt AB, Bagley N. Protection or harm? Suppressing substance use data. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(20):1879–1881. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1501362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frakt AB. Addiction research and care collide with federal privacy rules. The New York Times. 2015 Apr 27; Available at: http://www.nytimes.com/2015/04/28/upshot/federal-push-for-privacy-hampers-addiction-research-and-care.html?rref=upshot&abt=0002&abg=1&_r=0.

- 3.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. 42 CFR Part 2: Confidentiality of Alcohol and Drug Abuse Patient Records. [Accessed May 6, 2015]; Available at: http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/text-idx?rgn=div5;node=42%3A1.0.1.1.2.

- 4.Research and Data Assistance Center. Redaction of Substance Abuse Claims. [Accessed August 31, 2015]; Available at: http://www.resdac.org/resconnect/articles/203.