Supplemental Digital Content is Available in the Text.

Article first published online 7 March 2016.

Key Words: dose adjustment, dose escalation, disease flare, adalimumab, pediatric Crohn's disease

Abstract

Background:

The efficacy of adalimumab in inducing and maintaining remission in children with moderately to severely active Crohn's disease was shown in the IMAgINE 1 trial (NCT00409682). As per protocol, nonresponders or patients experiencing flare(s) on every other week (EOW) maintenance dosing could escalate to weekly dosing; we aimed to determine the therapeutic benefits of weekly dose escalation in this subpopulation.

Methods:

Week 52 remission and response rates were assessed in patients who escalated to weekly dosing from their previous EOW schedule, which was according to randomized treatment dose (higher dose [HD] adalimumab [≥40 kg, 40 mg EOW; <40 kg, 20 mg EOW] or lower dose [LD; ≥40 kg, 20 mg EOW; <40 kg, 10 mg EOW]). Adverse events were reported for patients remaining on EOW dosing and patients receiving weekly dosing.

Results:

Escalation to weekly dosing occurred in 48/95 (50.5%) patients randomized to LD and 35/93 (37.6%) patients randomized to HD adalimumab (P = 0.076). Week 52 remission and response rates were 18.8% and 47.9% for patients receiving LD adalimumab weekly and 31.4% and 57.1% for patients receiving HD adalimumab weekly, respectively (LD versus HD, P = 0.19 for remission; P = 0.41 for response). Adverse event rates were similar for patients receiving EOW and weekly adalimumab.

Conclusions:

Weekly adalimumab dosing was clinically beneficial for children with Crohn's disease who experienced nonresponse or flare on EOW dosing. No increased safety risks were observed with weekly dosing.

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease that is characterized by mucosal inflammation of the gastrointestinal tract with periods of relapse and remission. CD affects adults, adolescents, and children, although pediatric CD is often associated with a more complicated and aggressive disease course.1 Current therapeutic strategies aim at attaining durable maintenance of remission, with similar treatment goals for children as for adults: disease remission, improved quality of life, and avoidance of disease complications leading to surgery. However, normalization of growth and pubertal development remain unique to the pediatric age group.

The introduction of anti–tumor necrosis factor (TNF) therapy for adult and pediatric CD has had a significant impact on the management of the disease.2 Adalimumab is approved worldwide for the treatment of CD in adult patients and was recently approved in the United States for the treatment of moderately to severely active CD and in the European Union for severely active CD in pediatric patients, aged 6 to 17 years, who have had an inadequate response to conventional therapy.3,4 In the pivotal study IMAgINE 1, after a 4-week induction regimen, two double-blind maintenance dose regimens (lower dose [LD] and higher dose [HD]) were evaluated for safety and efficacy in children aged 6 to 17 years, inclusive, with moderately to severely active CD.5 Both dose regimens successfully induced and maintained remission (in 33.5% of patients overall, with no significant difference between the LD and HD regimens). Furthermore, >80% of patients enrolled in the trial responded to therapy within four weeks of treatment.5 Notably, infliximab-naive patients achieved greater remission and response rates than infliximab-experienced patients, with the infliximab-naive patients in the HD groups achieving the highest rates of remission and response.5

Although maintenance therapy with anti-TNF biologics has been shown to provide clinical benefits for patients with CD, a loss of response to treatment has been observed over time.6,7 Results from the Randomized controlled Evaluation of Adalimumab in treatment of Chronic plaque psoriasis of the Hands and feet (REACH) study in children with CD and from studies of adult patients with CD have shown that dose optimization modalities, such as increasing the dose or decreasing the time between doses, can be an effective strategy to recapture response for patients who lost response to anti-TNF therapy.2,8,9 Specifically, adjustment to weekly adalimumab dosing has been shown to be a benefit for adults with CD and ulcerative colitis who have lost response or had an inadequate response to therapy.10,11 Comparable data for pediatric patients with CD treated with adalimumab have not been described. Because patients in IMAgINE 1 who experienced nonresponse or flare to every other week adalimumab maintenance dosing could escalate to weekly dosing, we assessed the efficacy and safety of escalating to weekly dosing in children with CD. The predictors of escalation to weekly dosing were also examined.

METHODS

Study Design

IMAgINE 1 (NCT00409682) was a 52-week, phase 3, randomized, double-blind trial that assessed the efficacy and safety of 2 induction doses and 2 maintenance regimens of adalimumab in patients 6 to 17 years old with moderately to severely active CD. The primary results have been published previously.5 Briefly, pediatric patients with a diagnosis of CD for ≥12 weeks before study screening and Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index (PCDAI) >30 received open-label induction of adalimumab at weeks 0/2 according to body weight (patients weighing ≥40 kg received 160/80 mg, whereas patients weighing <40 kg received 80/40 mg) despite being treated with concurrent oral corticosteroids and azathioprine or monotherapy with azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, or methotrexate. At week 4, patients were randomized according to body weight to double-blind HD (≥40 kg received 40 mg every other week, <40 kg received 20 mg every other week) or LD (≥40 kg received 20 mg every other week, <40 kg received 10 mg every other week) adalimumab. Patients with previous exposure to infliximab were permitted to enroll in IMAgINE 1. All doses of CD-related therapy were to remain stable throughout the study, except for immunomodulators (azathioprine, 6-mercaptopurine, and methotrexate), which could be discontinued at or after week 26 at the discretion of the investigator. Corticosteroids could be tapered after week 4 for patients achieving clinical response (PCDAI decrease ≥15 points compared with baseline score).

Beginning at week 12, patients who met the protocol-defined criteria for flare or nonresponse could escalate from blinded every other week dosing to blinded weekly dosing, continuing with the same blinded dose, either HD or LD adalimumab. After at least 8 weeks of blinded weekly dosing, and not before week 20, patients with continued flare or nonresponse could move to open-label weekly HD adalimumab (≥40 kg received 40 mg weekly, <40 kg received 20 mg weekly). Flare was defined as an increase in PCDAI score ≥15 points compared to that of week 4 and PCDAI >30. Nonresponse was defined as 2 consecutive visits at least 2 weeks apart without a PCDAI decrease ≥15 points compared with the baseline score.

Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted with the approval of an independent ethics committee or an institutional review board for each site and in accordance with the guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonisation and ethical principles originating in the Declaration of Helsinki. All participating patients provided their written informed consents.

Data Analysis

Remission (PCDAI ≤10) and response (a PCDAI decrease by ≥15 points from baseline) at week 52 were assessed in patients who escalated to blinded weekly dosing, according to maintenance dose. This efficacy analysis was limited to patient data from study participants who escalated to blinded weekly dosing; therefore, patient data collected while the study participants received open-label weekly dosing were not included in the analysis. Patients who remained on blinded every other week dosing were analyzed separately for safety comparison. A subgroup analysis of previous infliximab use, concomitant immunomodulator use at baseline, concomitant corticosteroid use at baseline, baseline disease severity (PCDAI ≥40 versus PCDAI <40), disease duration (≤3 years versus >3 years), and sex was also performed.

Clinical Assessment

Clinical remission and response were assessed at weeks 4, 26, and 52. Adverse events were monitored throughout the study and recorded from the first dose until 70 days after the last adalimumab dose. Serum was collected at fixed time points of baseline and weeks 2, 4, 16, 26, and 52 to determine adalimumab trough concentration, and at baseline and weeks 16, 26, and 52 to determine antibodies to adalimumab. Both were measured by an in-house enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay.

Statistical Analysis

Week 52 remission and response rates were analyzed using nonresponder imputation, in which patients who discontinued from the study before week 52, those with missing PCDAI, or those who moved to open-label weekly dosing were considered not to have achieved remission or response. Fisher's exact test was used to compare patient demographics and baseline characteristics between treatment dose groups and between patients who escalated to blinded weekly dosing and those who remained on every other week dosing. Chi-square test was used to compare week 52 efficacy between treatment groups and between subgroups of patients who escalated to weekly dosing. Logistic regression was used to determine predictors of escalating to weekly dosing. Baseline variables assessed were sex, corticosteroid use, immunomodulator use, and previous infliximab use. Week 4 variables assessed at randomization were age, weight, C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration, PCDAI, remission, response, treatment dose, and adalimumab trough level. Adalimumab trough serum concentration at week 4 was compared between patients who escalated to weekly dosing and those who remained on every other week dosing using one-way analysis of variance. The effect of escalation to weekly dosing on adalimumab serum trough concentrations was evaluated by comparing the last serum trough concentration before dose escalation to the first trough level after dose escalation for patients with available data at both time points. Trough levels were not systematically obtained at the time of flare or dose escalation.

RESULTS

Patient Disposition and Baseline Demographics

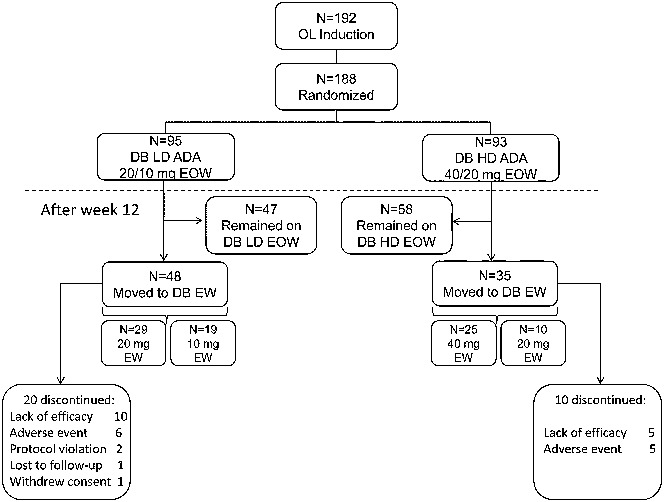

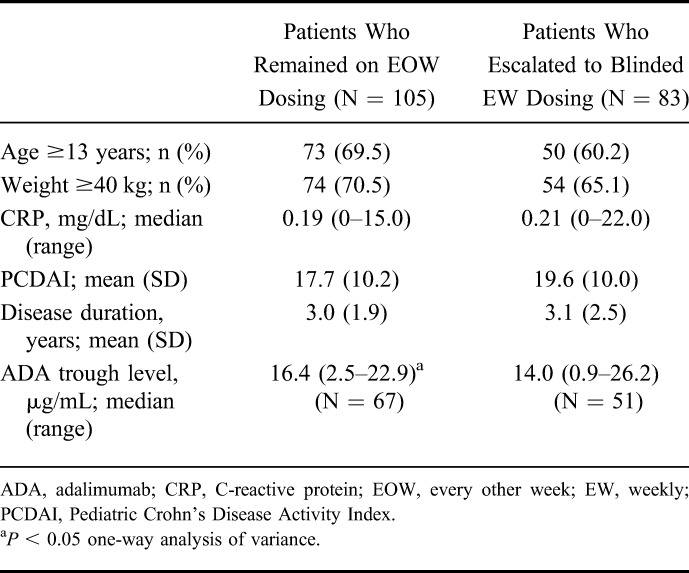

Patient disposition and primary reason for discontinuation are shown in Figure 1. A total of 83/188 (44.1%) patients escalated to blinded weekly dosing, namely 50.5% (48/95) of patients receiving LD adalimumab and 37.6% (35/93) of patients receiving HD adalimumab (P = 0.076). Baseline demographics and disease characteristics for patients who escalated to blinded weekly dosing and those who remained on every other week dosing are shown in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Disposition and flow of patients in IMAgINE 1. Primary reasons for discontinuation are shown. ADA, adalimumab; DB, double-blind; EOW, every other week; EW, weekly; HD, higher dose; LD, lower dose; OL, open-label.

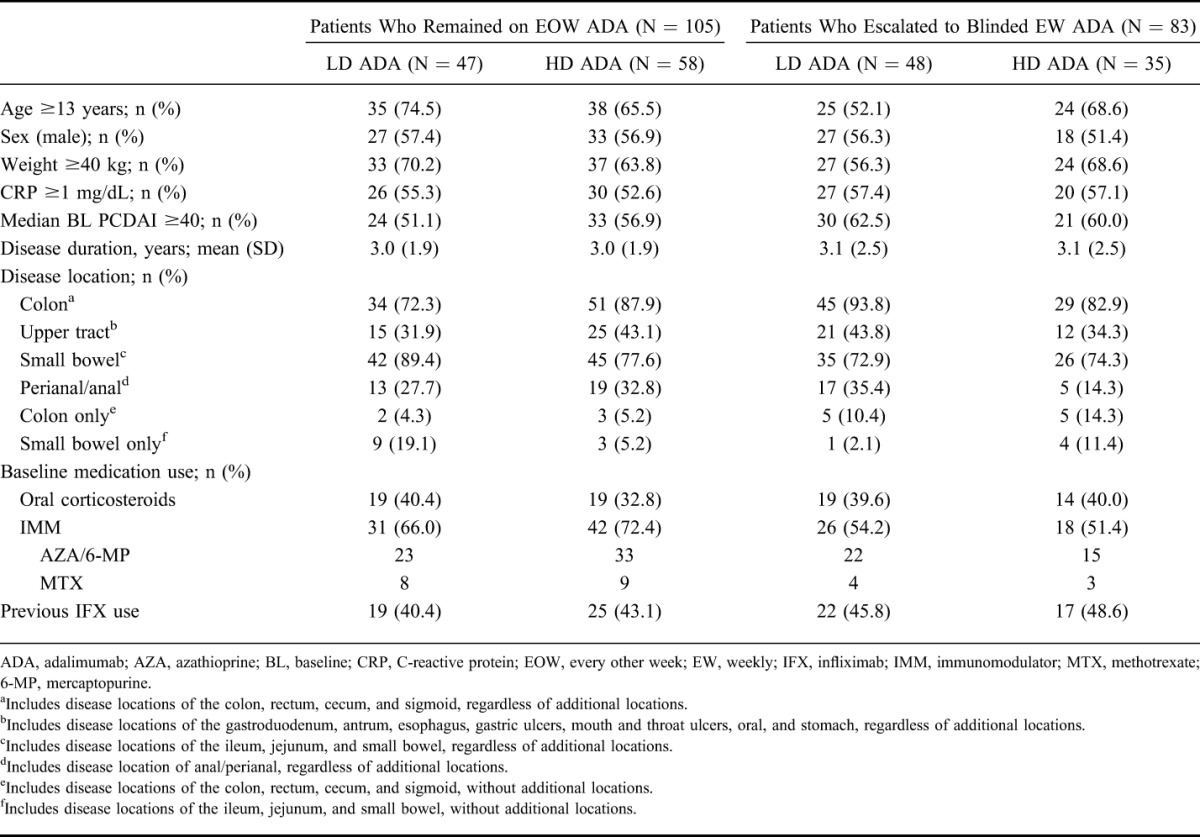

TABLE 1.

Baseline Demographics and Disease Characteristics in Patients Who Remained on Every Other Week or Escalated to Blinded Weekly Dosing

Timing of Dose Escalation

The proportion of patients who escalated to blinded weekly dosing at different times during the study was similar between the patients receiving LD and HD adalimumab (P = 0.74); 39.6% (19/48) and 34.3% (12/35) of patients escalated at week 12, 29.2% (14/48) and 37.1% (13/35) of patients escalated between weeks 12 and 26, and 31.3% (15/48) and 28.6% (10/35) of patients escalated between weeks 26 and 52 in the LD and HD groups, respectively.

Efficacy of Adalimumab in Patients Who Escalated to Blinded Weekly Dosing

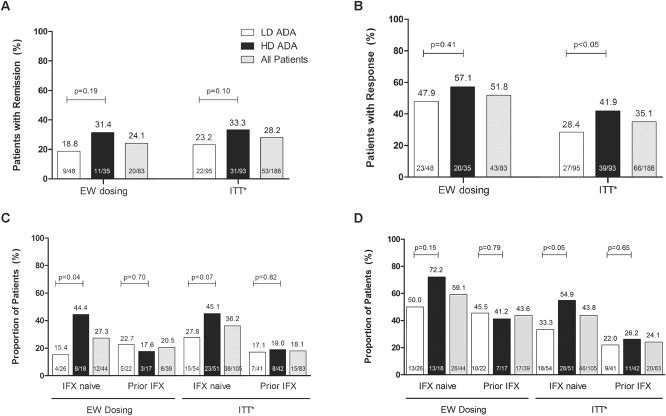

Week 52 remission and response rates in patients who escalated to blinded weekly dosing are shown in Figure 2. Of the 83 patients who escalated to blinded weekly dosing, 24.1% achieved remission and 51.8% achieved response (Fig. 2A, B). No statistically significant differences between LD and HD adalimumab were observed in remission or response rates for patients who escalated to blinded weekly dosing (Fig. 2A, B). Rates of remission and response after escalation were similar to those reported for the intent-to-treat population of IMAgINE 1 (28.2% remission, 35.1% response; Fig. 2A, B). Of note, patients in the intent-to-treat population who escalated to weekly dosing were considered as nonremitters or nonresponders. An analysis of remission within the LD and HD groups revealed that the highest rate of remission occurred in those who escalated to 40 mg weekly (data not shown). In subgroup analyses by previous infliximab status, a significantly higher percentage of infliximab-naive patients in the HD group achieved remission at week 52 than infliximab-naive patients in the LD group (Fig. 2C). No significant difference was observed between the LD and HD groups in infliximab-experienced patients (Fig. 2C, D). Overall, in all patients who dose escalated, no significant difference in the rate of remission was observed between infliximab-naive and infliximab-experienced patients at week 52 (27.3% naive versus 20.5% experienced, P = 0.47; Fig. 2C). Additionally, response rates at week 52 (59.1% naive versus 43.6% experienced, P = 0.16) were similar between infliximab-naive and infliximab-experienced patients in each dose group (Fig. 2D). Additional subgroup analyses of patients who escalated to weekly dosing are shown in Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/IBD/B232. No significant differences in remission rates were observed between treatment groups or between the various subgroups at week 52. Patients who escalated to blinded weekly dosing and used immunomodulators at baseline had a statistically significantly higher response rate at week 52 (28/44, 63.6%) than patients who did not use immunomodulators at baseline and escalated to blinded weekly dosing (15/39, 33.5%, P = 0.022). No significant differences were observed in week 52 response rates in the other subgroups assessed (see Supplementary Table 1, Supplemental Digital Content 1, http://links.lww.com/IBD/B232).

FIGURE 2.

Week 52 efficacy for patients who moved to weekly dosing and for the intent-to-treat population of IMAgINE 1 by treatment dose and all patients. Intent-to-treat analysis by treatment dose was previously reported in Hyams et al.5 A, Remission (PCDAI ≤10). B, Response (decrease in PCDAI ≥15 points from baseline). C, Remission by previous infliximab use. D, Response by previous infliximab use. *Intent-to-treat remission and response rates presented in Hyams et al5 and reprinted with permission from Elsevier. ADA, adalimumab; EW, weekly; HD, higher dose; IFX, infliximab; ITT, intent-to-treat; LD, lower dose; PCDAI, Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index.

Predictors of Dose Escalation

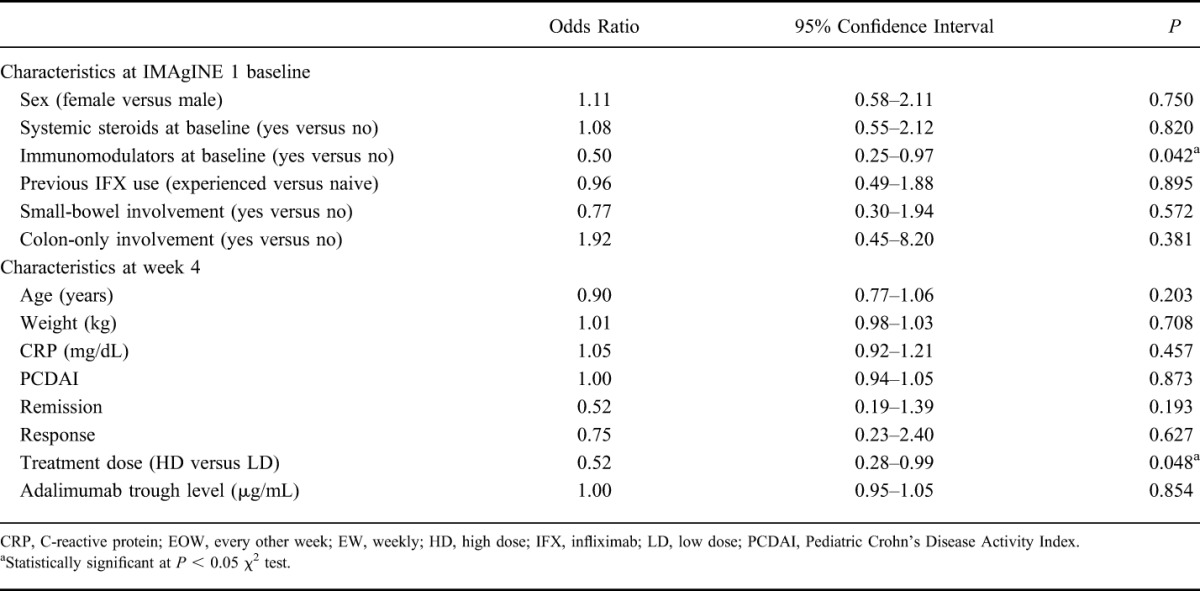

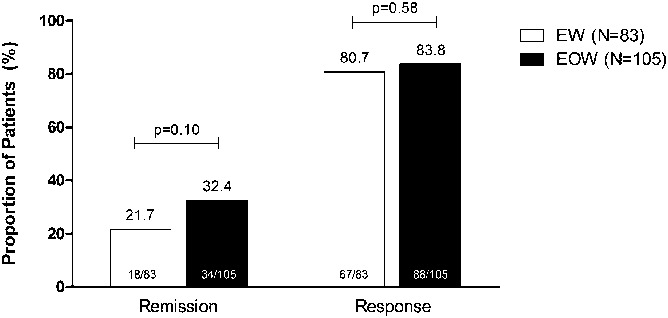

When baseline characteristics were used to predict the likelihood of dose escalation, patients who used immunomodulators at baseline (Table 1) were significantly less likely to escalate to weekly dosing than patients who did not use immunomodulators at baseline (odds ratio 0.50; P = 0.042, 95% confidence interval = 0.25–0.97) (Table 2). None of the other baseline characteristics, including disease location, were found to be associated with dose escalation. Among week 4 demographic or clinical variables, treatment dose was a significant predictor, with patients receiving HD less likely to escalate to weekly dosing than patients receiving LD adalimumab (odds ratio 0.52; P = 0.048, 95% confidence interval = 0.28–0.99). No other week 4 variables, including CRP, PCDAI, and remission and response status at randomization, were significant predictors of escalating to weekly dosing (Table 2). Patients who remained on every other week dosing had similar response rates at week 4 compared with those who escalated to blinded weekly dosing after week 12, although the remission rate at week 4 in patients who never dose escalated was numerically higher (Fig. 3). Median serum adalimumab trough levels at week 4 were statistically significantly higher in patients who remained on every other week dosing compared with patients who later escalated to weekly dosing (16.4 and 14.0 μg/mL, respectively, P < 0.05) (Table 3); however, this was not significant in multivariate analyses.

TABLE 2.

Predictors of Escalating to Weekly Dosing (Logistic Regression Analysis)

FIGURE 3.

Proportion of patients with remission and response at week 4 in patients who remained on every other week dosing (black bars, N = 105) and who escalated to blinded weekly dosing after week 12 (white bars, N = 83). Nonresponder imputation analysis. EOW, every other week; EW, weekly.

TABLE 3.

Week 4 Characteristics at Randomization in Patients Who Remained on Every Other Week Dosing and Who Escalated to Blinded Weekly Dosing After Week 12

Adalimumab Trough Serum Concentration in Patients Who Escalated to Weekly Dosing

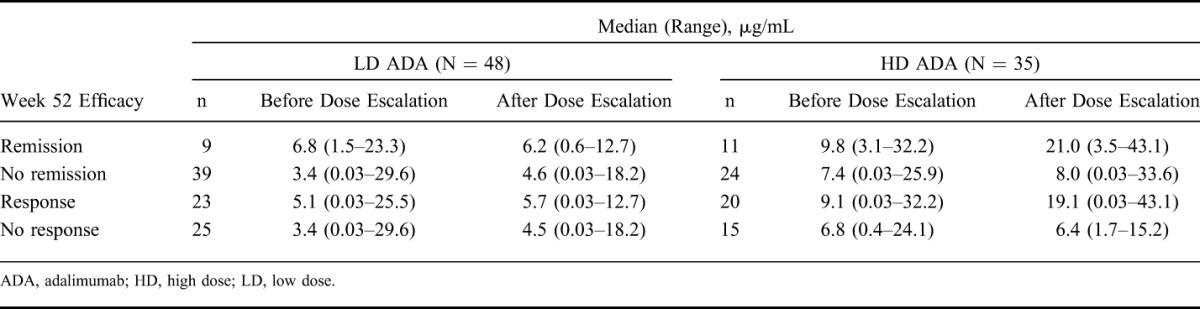

The median adalimumab trough serum concentration before and after escalation to weekly dosing (although not necessarily determined close to the time of escalation) by observed remission and response status at week 52 is shown in Table 4. The median (range) time difference between serum concentrations before and after escalation was 85 (57–245) days. For patients receiving HD adalimumab, numerically higher median adalimumab trough serum concentration was observed after dose escalation in patients who achieved remission or response at week 52 relative to patients who did not achieve these efficacy endpoints at week 52. No such numerical difference was seen for the LD dose-escalated group. As previously reported,5,12 6 patients developed anti-adalimumab antibodies during the study, 4 of whom escalated to blinded weekly dosing.

TABLE 4.

Median Serum Adalimumab Trough Concentration Before and After Escalation to Weekly Dosing by Dose and by Observed Week 52 Efficacy Category

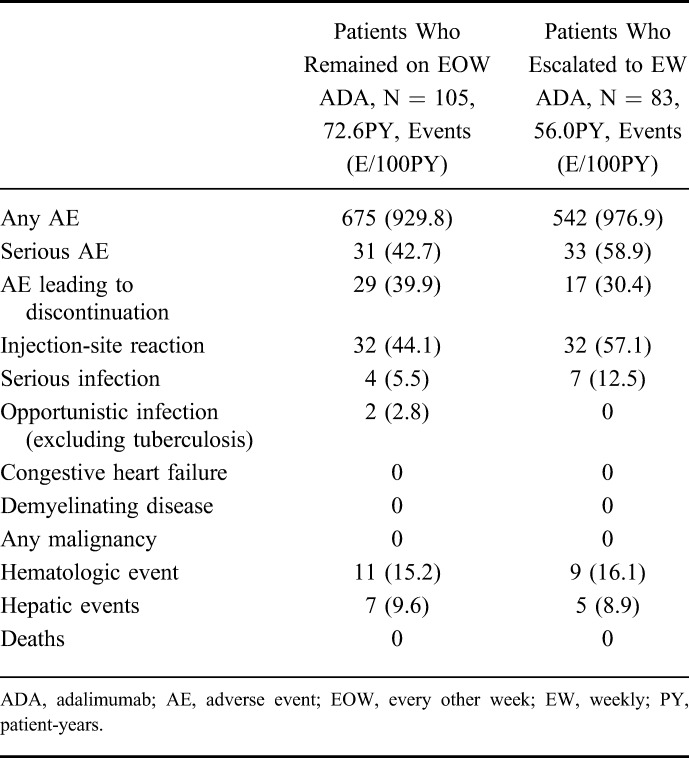

Safety

Treatment-emergent adverse events experienced during the double-blind maintenance period for patients who remained on every other week dosing and those who escalated to blinded weekly dosing are summarized in Table 5. Overall, the exposure-adjusted rate of any adverse event was similar between patients who remained on every other week dosing and those who escalated to blinded weekly dosing. Serious adverse events were mostly worsening of CD for patients receiving every other week or weekly dosing. Escalating to weekly dosing was not associated with an increased risk of adverse events, and no new safety signals were identified. No cases of tuberculosis, malignancy, or deaths were reported in IMAgINE 1. The serious infections observed in patients who dose escalated were abdominal and anal abscesses and device-related sepsis. Additionally, the overall safety profile of patients who escalated to double-blind weekly dosing was similar to that observed when these patients were receiving treatment every other week, with the exceptions of the exposure-adjusted rates of serious adverse events and adverse events leading to discontinuation, which were numerically higher after dose escalation, and hepatic events, which were numerically higher before dose escalation (see Supplementary Table 2, Supplemental Digital Content 2, http://links.lww.com/IBD/B233).

TABLE 5.

Summary of Treatment-Emergent Adverse Event Rates for Patients Who Remained on Every Other Week or Escalated to Weekly Dosing During the Double-Blind Maintenance Phase

DISCUSSION

The efficacy of adalimumab in inducing and maintaining remission with every other week dosing in children with CD was demonstrated in the IMAgINE 1 clinical trial.5 In this present analysis, we demonstrated that escalation to weekly dosing can be a beneficial treatment strategy for children with CD who lose response on every other week adalimumab maintenance dosing. At week 52, overall remission and response rates in patients who received weekly adalimumab dosing were 24.1% and 51.8%, respectively. These rates are similar to those observed for the intent-to-treat analysis in the IMAgINE 1 clinical trial.5 No significant differences in remission or response rates were observed between patients receiving LD or HD adalimumab; however, the proportions of patients achieving these endpoints were numerically higher in the HD-randomized treatment group. Furthermore, escalation to weekly dosing was not associated with increased safety risks.

The current European Crohn's and Colitis Organization/European Society for Paediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition consensus guidelines recommend dose optimization for patients losing response to therapy before switching biologic therapy.13 We demonstrated that patients losing response to treatment or not responding initially can achieve clinically meaningful remission rates at 1 year with weekly dosing, including patients with previous infliximab use. Although, numerically more infliximab-naive patients achieved remission and response than infliximab-experienced patients, no significant differences between the subgroups were observed. Furthermore, in our study, previous anti-TNF use was not associated with dose escalation, which has been shown to be a predictor in a pooled analysis of several pediatric and adult CD studies.14

Approximately half of the patients receiving LD adalimumab escalated to weekly dosing. Treatment dose at week 4 was the only statistically significant predictor of dose escalation; patients treated with HD adalimumab were less likely to escalate to weekly dosing than those treated with LD adalimumab. Additionally, in our study, the analysis of factors predicting dose escalation identified that patients using concomitant immunomodulators at baseline were less likely to require dose escalation. Although remission and response rates at week 4 were similar between patients regardless of baseline immunomodulator use, previously reported mean serum adalimumab levels were slightly higher in patients on concomitant immunomodulators (no immunomodulator use: 12.2 ± 6.32 μg/mL, immunomodulator use: 14.9 ± 6.98 μg/mL).12,15 The difference was not statistically significant, and the range of the concentrations in both groups largely overlapped. The role that baseline immunomodulator use plays in predicting dose escalation requires further study.

Results from the IMAgINE 1 study have shown that higher serum adalimumab concentrations were associated with greater levels of efficacy in pediatric CD.12 Similarly, in this analysis, we demonstrated that in patients who moved to weekly dosing and those who achieved remission or response at week 52 had higher serum adalimumab trough levels after dose escalation relative to patients who did not achieve these endpoints. Although treatment dose after week 4 was not a significant predictor of dose escalation, patients who moved to weekly dosing had significantly lower serum adalimumab trough levels at week 4 than patients who remained on every other week dosing, whereas the range of the values was similar between both groups. Additionally, the adalimumab trough level at week 4 was not an independent predictor of dose escalation later in the study, based on logistic regression analysis. Immunogenicity was low in the IMAgINE 1 study. As previously reported,5,12 only 6 patients developed anti-adalimumab antibodies during the study; these numbers are too small to make any conclusion regarding efficacy and anti-adalimumab antibodies.

This analysis has a few limitations. First, dose escalation was restricted to 1 year and to double-blind treatment. Second, the decision to move to weekly dosing was based on prespecified PCDAI criteria and not due to serum adalimumab trough levels or anti-drug antibodies. Furthermore, additional clinical investigations such as imaging or biomarkers of inflammation, including fecal markers, were not collected at the time of dose adjustment. Of note, the analyses were post hoc. The present data, however, demonstrate that weekly adalimumab dosing is safe and a beneficial treatment option for pediatric patients who lose clinical response or do not respond to every other week dosing.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

AbbVie Inc. funded the study and the analysis, and reviewed and approved the publication for submission. Medical writing support was provided by Kristina Kligys, PhD, of AbbVie Inc., and Katie Groschwitz, PhD, of Complete Publication Solutions, LLC. AbbVie provided funding to Complete Publication Solutions for medical writing support.

M. C. Dubinsky reports having received consulting fees or honoraria and support for travel to meetings for study purposes from AbbVie. J. Rosh reports having received consulting fees from AbbVie, Janssen, Receptos, and Soligenix; speaker fees from AbbVie and Prometheus; and research support from AbbVie and Janssen (paid to his institution). W. A. Faubion reports having received consulting fees and fees for participation in review committees and advisory boards from AbbVie (paid to his institution) and support for travel to meetings for study purposes from AbbVie. J. Kierkus reports having received speaker fees from AbbVie and research support from AbbVie (paid to his institution). F. Ruemmele reports having received speaker fees from Schering-Plough, Nestlé, MeadJohnson, Ferring, MSD, Johnson & Johnson, and Centocor. J. S. Hyams reports having received consulting fees from Janssen Orthobiotech, AbbVie, TNI Biotech, EnteraHealth, Pfizer, Soligenix, Takeda, Avaxia, and Celgene; and speaker fees and payment for development of educational presentations from Janssen Orthobiotech. S. Eichner, Y. Li, B. Huang, N. M. Mostafa, A. Lazar, and R. B. Thakkar are AbbVie employees and may own AbbVie stock and/or options.

Footnotes

Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal's Web site (www.ibdjournal.org).

Author disclosures are available in the Acknowledgments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Pigneur B, Seksik P, Viola S, et al. Natural history of Crohn's disease: comparison between childhood- and adult-onset disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:953–961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hyams J, Crandall W, Kugathasan S, et al. Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:863–873; quiz 1165–1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Humira (Adalimumab). Full Prescribing Information. North Chicago, IL: AbbVie Inc.; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Humira—Summary of Product Characteristics. Available at: http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/21201/SPC/Humira+Pre-filled+Pen%2c+Pre-filled+Syringe+and+Vial/. Accessed August 8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hyams JS, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, et al. Safety and efficacy of adalimumab for moderate to severe Crohn's disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:365–374.e362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hyams JS, Lerer T, Griffiths A, et al. Long-term outcome of maintenance infliximab therapy in children with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2009;15:816–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hyams JS, Lerer T, Griffiths A, et al. Outcome following infliximab therapy in children with ulcerative colitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105:1430–1436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Katz L, Gisbert JP, Manoogian B, et al. Doubling the infliximab dose versus halving the infusion intervals in Crohn's disease patients with loss of response. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2012;18:2026–2033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kopylov U, Mantzaris GJ, Katsanos KH, et al. The efficacy of shortening the dosing interval to once every six weeks in Crohn's patients losing response to maintenance dose of infliximab. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33:349–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sandborn WJ, Colombel JF, Schreiber S, et al. Dosage adjustment during long-term adalimumab treatment for Crohn's disease: clinical efficacy and pharmacoeconomics. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:141–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wolf D, D'Haens G, Sandborn WJ, et al. Escalation to weekly dosing recaptures response in adalimumab-treated patients with moderately to severely active ulcerative colitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2014;40:486–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sharma S, Eckert D, Hyams JS, et al. Pharmacokinetics and exposure-efficacy relationship of adalimumab in pediatric patients with moderate to severe Crohn's disease: results from a randomized, multicenter, phase-3 study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:783–792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ruemmele FM, Veres G, Kolho KL, et al. Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1179–1207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Billioud V, Sandborn WJ, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Loss of response and need for adalimumab dose intensification in Crohn's disease: a systematic review. Am J Gastroenterol. 2011;106:674–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hyams J, Ruemmele F, Colletti RB, et al. Impact of concomitant immunosuppressant use on adalimumab efficacy in children with moderately to severely active Crohn's disease: results from IMAgINE 1. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:S-214. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.