Abstract

Objectives:

To investigate the association between Kaposi's sarcoma-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (KS-IRIS) and mortality, with the use of glucocorticoids in HIV-infected individuals.

Design:

Case–control study.

Methods:

We reviewed the medical records of 145 individuals with HIV-associated Kaposi's sarcoma receiving antiretroviral therapy. The association of different variables with KS-IRIS and Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality was explored by univariate and multivariate analyses. The main exposure of interest was the use of glucocorticoids. We also compared the time to KS-IRIS and the time to death of individuals treated with glucocorticoids vs. those nontreated with glucocorticoids, and the time to death of individuals with KS-IRIS vs. those without KS-IRIS by hazards regression.

Results:

Sixty of 145 individuals received glucocorticoids (41.4%) for the management or suspicion of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia. Fifty individuals had KS-IRIS (37%). The use of glucocorticoids was more frequent in individuals with KS-IRIS than in those without KS-IRIS (54.9 vs. 36.47%, P = 0.047). Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality occurred in 17 cases (11.7%), and glucocorticoid use was more frequent in this group (76.47 vs. 36.7%, P = 0.003). Glucocorticoid use was a risk factor for mortality (adjusted odds ratio = 4.719, 95% confidence interval = 1.383–16.103, P = 0.0132), and was associated with shorter periods to KS-IRIS (P = 0.03) and death (P = 0.0073). KS-IRIS was a risk factor for mortality (P = 0.049).

Conclusion:

In HIV-infected individuals, the use of glucocorticoids is a risk factor for KS-IRIS and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated mortality. In addition, KS-IRIS is a risk factor for mortality. Therefore, glucocorticoid administration in this population requires careful consideration based on individualized risk–benefit analysis.

Keywords: AIDS, antiretroviral therapy, glucocorticoids, HIV, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome, Kaposi, sarcoma

Introduction

Kaposi's sarcoma is caused by infection with the human herpes virus 8 (HHV-8), and disease progression involves a process of viral oncogenesis within a permissive context of deregulated cytokines and immunosuppression [1]. Although the incidence and mortality associated with Kaposi's sarcoma have decreased with the use of antiretroviral therapy (ART), Kaposi's sarcoma remains the most common malignancy in HIV-infected population [2]. What is more, almost 20% of Kaposi's sarcoma patients in pooled African cohorts and 8.5% in a London cohort developed Kaposi's sarcoma-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (KS-IRIS). In resource-limited settings, this condition is a frequent cause of morbidity and mortality [3].

Multiple case reports indicate that administration of systemic glucocorticoids to HIV-infected individuals accelerates clinical progression of Kaposi's sarcoma [4–9]. However, there are no published studies showing the real impact of glucocorticoids on the development or clinical worsening of Kaposi's sarcoma in HIV-infected population. Our institution is a national referral centre for respiratory diseases, with a large number of HIV-infected individuals requiring the use of glucocorticoids for the treatment of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (PCP). By consequence, it is an ideal place for assessing the association between Kaposi's sarcoma morbidity and mortality with the use of glucocorticoids in the context of HIV infection. This is the first case–control study reporting the use of glucocorticoids as a risk factor for KS-IRIS and for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated mortality in HIV-infected individuals.

Patients and methods

Study population

This study was conducted at the Department of Research in Infectious Diseases at the National Institute of Respiratory Diseases, a national referral centre in Mexico City. Individuals attending our institution frequently have PCP or Mycobacterium tuberculosis pneumonia, so they usually receive antibiotics and glucocorticoids for the treatment of such infections. We retrospectively reviewed the medical records of individuals with HIV infection and associated Kaposi's sarcoma, who started ART between January 2008 and August 2014 at our institution. The main outcomes of interest were KS-IRIS and Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality. The main exposure of interest was the use of glucocorticoids.

Case definitions for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

Diagnosis of IRIS was based on the consensus criteria of the International Network for the Study of HIV-Associated IRIS [10], specified as follows: response to ART by receiving HIV ART and virologic response with more than 1 log10 copies/ml decrease in HIV RNA; clinical deterioration of an infectious or inflammatory condition temporally related to ART initiation (<1 year); and inability to explain symptoms by expected clinical course of a previously recognized and successfully treated infection, medication side-effect or toxicity, treatment failure and complete nonadherence.

Procedures

The retrospective review of medical records included sociodemographic variables such as age, sex and risk factors for HIV infection. Variables from the clinical domain included time elapsed between HIV and Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis; delay of ART (defined as >3 months of ART initiation after Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis); total duration of ART at Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis (defined as time from ART initiation to Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis); time to KS-IRIS (defined as >2 weeks and ≤12 months of ART at KS-IRIS diagnosis); ART regimens (use of nonnucleoside analogues, protease inhibitors or other); Kaposi's sarcoma localization (cutaneous, mucocutaneous or visceral); type of cutaneous lesion (macule, plaque or tumour); use of systemic glucocorticoids; opportunistic infections at Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis; unmasking or paradoxical KS-IRIS; use of chemotherapy (regimen, cycles and response); and Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality. Determinations of HIV-RNA load, CD4+ and CD8+ T-cell counts were performed at diagnosis of HIV, Kaposi's sarcoma and KS-IRIS.

Statistical analysis

The association of variables with outcomes of interest was explored by using univariate analysis. We used Fisher's exact test for binomial variables and Student's t test for continuous variables. The outcomes evaluated were KS-IRIS and Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality. A two-sided P value <0.05 was considered to be significant. Only variables with a P value <0.05 in univariate analyses were included in multivariate analyses for KS-IRIS and Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were obtained using logistic regression analyses. The main exposure of interest was the use of glucocorticoids. We also performed survival analyses of the time to KS-IRIS and time to death comparing individuals treated with glucocorticoids vs. those nontreated with glucocorticoids, by using a Cox proportional hazards regression model. Additionally, we compared the time to death of individuals with KS-IRIS vs. those without KS-IRIS. These analyses were carried out with R statistical software (v3.2.0; R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the ‘survival’ (v2.38) package.

Results

During the period between January 2008 and August 2014, 169 individuals were diagnosed with HIV-associated Kaposi's sarcoma at our institution. Of those, 24 were deemed ineligible for this study because they were not receiving ART before or at Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis and would not be a suitable population for the study of IRIS. We thus included 145 individuals who started ART during the aforementioned period and had a clinical and histological diagnosis of Kaposi's sarcoma. Of those, five were women (3.45%). The median age of individuals at Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis was of 32 years [interquartile range (IQR), 28–39]; 63 had mucocutaneous Kaposi's sarcoma (43.4%); nine had visceral Kaposi's sarcoma (6.2%); 73 had visceral and mucocutaneous Kaposi's sarcoma (50.3%); 102 had a concomitant opportunistic infection (70.3%); 51 received chemotherapy (35.2%); 60 received glucocorticoids (41.4%); the median CD4+ cell count at Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis was 90.5 cells/μl (IQR, 34.5–160.7); the median CD8+ cell count at Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis was 586.5 cells/μl (IQR, 275.5–1057) and the median HIV load at Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis was 60 805 (IQR, 171.7–313,717.7).

IRIS could not be assessed in 10 individuals because of insufficient follow-up. By consequence, they were not included in the IRIS analyses. Of the remaining 135 individuals, 50 developed KS-IRIS (37%). Of those, 17 had unmasking IRIS (12.6%) and 33 had paradoxical IRIS (24.4%). Median time to KS-IRIS was 60 days (IQR, 30–97.5). Fifty-eight individuals (42.96%) were treated with glucocorticoids, and 27 of those developed IRIS (46.55%). In the group nontreated with glucocorticoids, 23 individuals developed IRIS (29.87%). Seventeen individuals died, and 13 of those had received glucocorticoids (76.5%). All deaths were associated with Kaposi's sarcoma.

Kaposi's sarcoma-associated immune reconstitution inflammtory syndrome is associated with the use of glucocorticoids

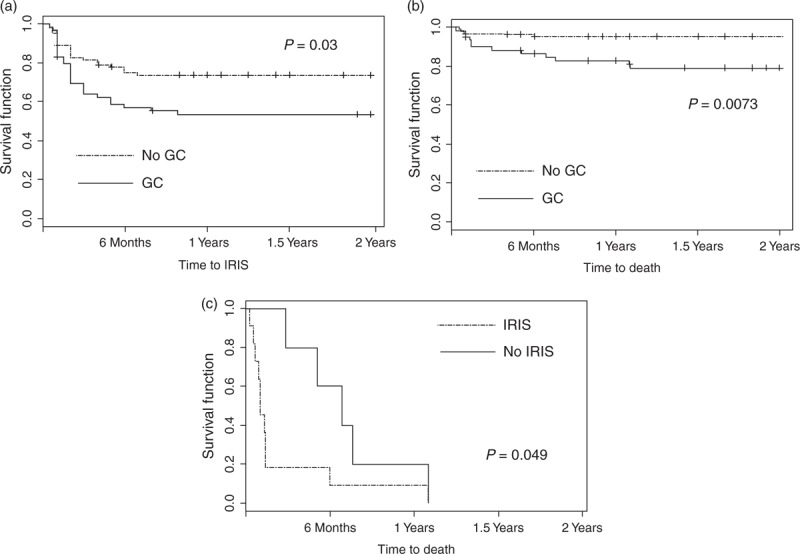

All variables included in the univariate and multivariate analyses are listed in Table 1. The univariate analysis indicated that glucocorticoid use was more frequent in individuals with KS-IRIS than in those without KS-IRIS (54.9 vs. 36.47%, P = 0.0474). After adjusting for possible confounding variables, glucocorticoid use was still a risk factor for the development of KS-IRIS (unadjusted OR = 2.045, 95% CI = 1.005–4.16, P = 0.0484; adjusted OR = 2.3622, 95% CI = 1.0838–5.149, P = 0.0306). Individuals treated with glucocorticoids had a significantly higher hazard ratio for KS-IRIS than those nontreated with glucocorticoids (P = 0.03; Fig. 1a).

Table 1. Association of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated mortality with the use of glucocorticoids.

| Univariate analyses | ||||||

| Variable | KS-IRIS (N = 135, % or mean) | KS mortality (N = 145, % or mean) | ||||

| KS-IRIS (N = 50) | Non-KS-IRIS (N = 85) | P | Death (N = 17) | Survival (N = 128) | P | |

| Male gender | 100% | 96.47% | 0.2952 | 88.00% | 97.66% | 0.1049 |

| Age at KS Dx | 31.46 | 34.84 | 0.0216 a | 34.29 | 33.36 | 0.7798 |

| MSM | 94.00% | 81.18% | 0.0428 a | 70.59% | 87.50% | 0.0747 |

| ART delay (months) | 11.33 | 16.46 | 0.3734 | 7.27 | 17.37 | 0.0585 |

| Visceral KS | 42.00% | 38.82% | 0.7202 | 70.59% | 35.16% | 0.0074 a |

| Glucocorticoid use | 54.90% | 36.47% | 0.0474 a | 76.47% | 36.72% | 0.0030 a |

| Mycobacterium sp | 42.00% | 28.23% | 0.1305 | 41.18% | 31.25% | 0.4192 |

| CD4+ cell count at KS Dx | 147.32 | 103.25 | 0.0474 a | 115.29 | 124.08 | 0.7696 |

| HIV load at KS Dx | 278,744 | 308,834 | 0.7757 | 67,824 | 311,816 | 0.00003 a |

| OIs | 76.00% | 69.41% | 0.4362 | 70.59% | 70.31% | 1 |

| Multivariate analyses | ||||||

| Variable | KS-IRIS (N = 135) | KS mortality (N = 145) | ||||

| OR | 95% CI | P | OR | 95% CI | P | |

| Glucocorticoid use (unadjusted) | 2.045 | 1.005–4.160 | 0.0484 a | 5.601 | 1.727–18.170 | 0.0041 a |

| Glucocorticoid use b | 2.362 | 1.0838–5.149 | 0.0306 a | 4.719 | 1.383–16.103 | 0.0132 a |

| MSM b | 4.192 | 1.017–17.281 | 0.0473 a | NA | NA | NA |

| CD4+ at KS Dx b | 1.004 | 1.001–1.008 | 0.0104 a | NA | NA | NA |

| Visceral KS | NA | NA | NA | 3.551 | 1.076–11.72 | 0.0376 a |

ART delay, more than 3 months of ART initiation after KS diagnosis; ART, antiretroviral therapy; CD4+ and CD8+ counts are expressed in cells/μl; CI, confidence interval; Dx, diagnosis; KS, Kaposi's sarcoma; KS-IRIS, Kaposi's sarcoma-associated immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; OI, opportunistic infection; OR, odds ratio.

aA two-sided P value ≤0.05 was considered to be significant. Only significant variables in univariate analyses were included in multivariate models. NA, not applied to the multivariate model.

bAdjusted values.

Fig. 1.

Kaplan–Meier survival curves.

(a) Time to IRIS for individuals treated with glucocorticoids (solid line), and individuals nontreated with glucocorticoids (dotted line). (b) Time to death for individuals treated with glucocorticoids (solid line), and individuals nontreated with glucocorticoids (dotted line). (c) Time to death regardless of glucocorticoid use for individuals without IRIS (solid line), and individuals with IRIS (dotted line). Only individuals experiencing Kaposi's sarcoma-associated death were included. Time 0 corresponded to Kaposi's sarcoma diagnosis. Vertical tick marks indicate right censoring. IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome.

Use of glucocorticoids is a risk factor for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated mortality

The univariate analysis indicated that glucocorticoids use was more frequent in individuals who experienced Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality than in survivors (76.5 vs. 36.7%, P = 0.003). In the multivariate analysis, glucocorticoids use remained a significant risk factor for Kaposi's sarcoma-associated mortality (crude OR = 5.601, 95% CI = 1.727–18.170, P = 0.004; adjusted OR = 4.719, 95% CI = 1.383–16.103, P = 0.0132). Time to death was significantly shorter for individuals treated with glucocorticoids than for those nontreated with glucocorticoids (P = 0.0073; Fig. 1b). In addition, KS-IRIS was a risk factor for mortality regardless of glucocorticoid use (P = 0.049; Fig. 1c).

Discussion

As far as we know, this is the first case–control study reporting the use of glucocorticoids as a risk factor for KS-IRIS and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated mortality in HIV-infected individuals. Some independent risk factors for KS-IRIS reported in the literature are detectable plasma HHV-8 DNA; haematocrit less than 30%; clinical Kaposi's sarcoma at pre-ART visit [11]; CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts less than 50 cells/μl [12]; ART alone as Kaposi's sarcoma treatment; T1 Kaposi's sarcoma stage; plasma HIV-1 RNA more than 5 log10 copies/ml [3] and tumour-associated oedema [13]. However, exposure to glucocorticoids therapy was not reported in these studies.

Mortality associated with Kaposi's sarcoma has been reported as 32.8% in individuals developing KS-IRIS and 11.1% in non-IRIS individuals, with a 3.3-fold higher mortality in African individuals compared with European individuals [3]. Factors previously associated with mortality include KS-IRIS; lack of chemotherapy; CD4+ T-lymphocyte counts less than 200 cells/μl before ART initiation; and a detectable HHV-8 load. To our knowledge, the association of glucocorticoid use with Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality has not been evaluated before. Our study has shown four-fold odds of Kaposi's sarcoma-related mortality in individuals receiving glucocorticoids, after controlling for possible confounding factors. Glucocorticoid therapy has also been clinically associated with development of Kaposi's sarcoma in non-HIV-related diseases such as transplant recipients [14,15]; rheumatic disorders [16,17]; asthma [18]; lung cancer [19]; dermatologic diseases [20,21]; atopic dermatitis [22]; ulcerative colitis [23]; glomerulonephritis [24,25] and many other clinical conditions of iatrogenic immunosuppression. In most cases, withdrawal of immunosuppressive therapies leads to Kaposi's sarcoma remission, but not in the case of HIV-infected individuals [7].

Numerous mechanisms could potentially explain the association of glucocorticoids with Kaposi's sarcoma disease progression. Steroids are anti-inflammatory drugs that seem to inhibit most of the major components of inflammation. If glucocorticoids suppress natural killer cell activity, and these cells play an important role against cancer, glucocorticoids might give rise to aberrations in the immune surveillance, which may lead to subsequent conditions favourable to oncogenesis. In addition, it is well known that exogenous glucocorticoids stimulate directly the proliferation of Kaposi's sarcoma spindle cells by modulating their glucocorticoids receptor expression [26] and HHV-8 activation [27]. Indirect stimulation of Kaposi's sarcoma growth with the use of exogenous glucocorticoids has also been reported, such as upregulation of oncostatin M and IL-6/sIL-6R acting as growth factors for Kaposi's sarcoma cells [28]; and blockade of transforming growth factor-β, an autocrine inhibitory factor for Kaposi's sarcoma [29].

The study was conducted in a referral centre, and this represents a potential source of referral bias. Another limitation of this case–control study is derived from the retrospective design. As not all individuals had a complete examination before ART initiation, some of those with paradoxical KS-IRIS might have been erroneously included in the group with unmasking KS-IRIS. An additional study limitation is derived from the passive case-detection approach used for KS-IRIS diagnosis, as we were unable to differentiate individuals who had KS-IRIS due to ART-induced immune reconstitution, from those in whom the use of ART and glucocorticoids originated Kaposi's sarcoma exacerbation, and those in whom Kaposi's sarcoma exacerbation was only caused by the use of glucocorticoids. As the IRIS definition used here includes the inability to explain symptoms by a medication side-effect or toxicity, it is possible that individuals receiving glucocorticoids do not fulfil this criterion. In that case, the diagnosis of Kaposi's sarcoma-IRIS could be questioned in this study and in any other including individuals with Kaposi's sarcoma disease progression receiving glucocorticoids.

Conclusion

The association of glucocorticoid use with an increased incidence of Kaposi's sarcoma has only been documented in case reports. We found that in HIV-infected population, glucocorticoids use is a risk factor for KS-IRIS and Kaposi's sarcoma-associated mortality. Moreover, KS-IRIS is a risk factor for mortality. Therefore, particularly in HIV-infected individuals starting ART, administration of glucocorticoids should be made on a case-by-case basis after an assessment of risks and benefits, and under close monitoring for early detection of Kaposi's sarcoma lesions.

Acknowledgements

Author's contributions: G.R.T. contributed to study conception and design. M.F.S., M.C.I., Y.A.T. and C.E.O. participated in acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data. C.E.O. performed the statistical analysis. C.A.B. and M.F.S. drafted the manuscript. All authors were involved in the critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content, and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding: This work was supported by grants from the Mexican Government (Comisión de Igualdad de Género de la Honorable Cámara de Diputados de la LXII Legislatura de México). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. Hengge UR, Ruzicka T, Tyring SK, Stuschke M, Roggendorf M, Schwartz RA, et al. Update on Kaposi's sarcoma and other HHV8 associated diseases. Part 1: epidemiology, environmental predispositions, clinical manifestations, and therapy . Lancet Infect Dis 2002; 2:291–292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. International Collaboration on HIV Cancer. Highly active antiretroviral therapy and incidence of cancer in human immunodeficiency virus infected adults . J Natl Cancer Inst 2000; 92:1823–1830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Letang E, Lewis B, Borok M, Campbell TB, Naniche D, Newsom-Davis T, et al. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi sarcoma: higher incidence and mortality in Africa than in the UK . AIDS 2013; 27:1603–1613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schulhafer EP, Grossman ME, Fagin G, Bell KE. Steroid-induced Kaposi's sarcoma in a patient with pre-AIDS . Am J Med 1987; 82:313–317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Real FX, Krown SE, Koziner B. Steroid-related development of Kaposi's sarcoma in a homosexual man with Burkitt's lymphoma . Am J Med 1986; 80:119–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Gill PS, Loureiro C, Bernstein-Singer M, Rarick MU, Sattler F, Levine AM. Clinical effect of glucocorticoids on Kaposi sarcoma related to the acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) . Ann Intern Med 1989; 110:937–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Volkow PF, Cornejo P, Zinser JW, Ormsby CE, Reyes-Teran G. Life-threatening exacerbation of Kaposi's sarcoma after prednisone treatment for immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome . AIDS 2008; 22:663–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Valencia ME, Piedrafita V, Del Val D, Corcuera MT. Aggressive Kaposi's sarcoma related to corticosteroids or immune reconstitution syndrome? . Rev Clín Esp 2011; 211:321–322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Englert D, Seal P, Parsons C, Arbour A, Roberts E, 3rd, Lopez FA. Clinical case of the month: a 22-year-old man with AIDS presenting with shortness of breath and an oral lesion . J La State Med Soc 2014; 166:224–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. International Network for the Study of HIV-Associated IRIS. General case definition. Available at: http://www.inshi.umn.edu/definitions/General_IRIS/home.html [Accessed 30 January 2015] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Letang E, Almeida JM, Miró JM, Ayala E, White IE, Carrilho C, et al. Predictors of immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome-associated with Kaposi sarcoma in Mozambique: a prospective study . J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr 2010; 53:589–597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Müller M, Wandel S, Colebunders R, Attia S, Furrer H, Egger M, et al. IeDEA Southern and Central Africa. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome in patients starting antiretroviral therapy for HIV infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis . Lancet Infect Dis 2010; 10:251–261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bower M, Nelson M, Young AM, Thirlwell C, Newsom-Davis T, Mandalia S, Dhillon T. Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome associated with Kaposi's sarcoma . J Clin Oncol 2005; 23:5224–5228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Lesnoni La Parola I, Masini C, Nanni G, Diociaiuti A, Panocchia N, Cerimele D. Kaposi's sarcoma in renal-transplant recipients: experience at the Catholic University in Rome, 1988–1996 . Dermatology 1997; 194:229–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Aebischer MC, Zala LB, Braathen LR. Kaposi's sarcoma as manifestation of immunosuppression in organ transplant recipients . Dermatology 1997; 195:91–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Taniguchi T, Asano Y, Kawaguchi M, Kogure A, Mitsui H, Sugaya M, et al. Disseminated cutaneous and visceral Kaposi's sarcoma in a patient with rheumatoid arthritis receiving corticosteroids and tacrolimus . Mod Rheumatol 2011; 21:309–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Casoli P, Tumiati B. Kaposi's sarcoma, rheumatoid arthritis and immunosuppressive and/or corticosteroid therapy . J Rheumatol 1992; 19:1316–1317. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Krussmann A, Goerg R, Laberke HG, Weidner FO. Extensive metastatic Kaposi sarcoma in chronic immune suppressed bronchial asthma . Hautarzt 1993; 44:232–234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kato N, Harada M, Yamashiro K. Kaposi's sarcoma associated with lung cancer and immunosuppression . J Dermatol 1996; 23:564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaplan RP, Israel SR, Ahmed AR. Pemphigus and Kaposi's sarcoma . J Dermatol Surg Oncol 1989; 15:1116–1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boudhir H, Mael-Ainin M, Senouci K, Hassam B, Benzekri L. Kaposi's disease: an unusual side-effect of topical corticosteroids . Ann Dermatol Venereol 2013; 140:459–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Vandercam B, Lachapelle JM, Janssens P, Tennstedt D, Lambert M. Kaposi's sarcoma during immunosuppressive therapy for atopic dermatitis . Dermatology 1997; 194:180–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Rodriguez-Pelaez M, Fernandez-Garcia MS, Gutierrez-Corral N, de Francisco R, Riestra S, García-Pravia C, et al. Kaposi's sarcoma: an opportunistic infection by human herpesvirus-8 in ulcerative colitis . J Crohn's Colitis 2010; 4:586–590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Al-Brahim N, Zaki AH, El-Merhi K, Ahmad MS. Tonsillar Kaposi sarcoma in a patient with membranous glomerulonephritis on immunosuppressive therapy . Ear, Nose Throat J 2013; 92:E1–E4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Agbaht K, Pepedil F, Kirkpantur A, Yilmaz R, Arici M, Turgan C. A case of Kaposi's sarcoma following treatment of membranoproliferative glomerulonephritis and a review of the literature . Ren Fail 2007; 29:107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Guo WX, Antakly T. AIDS-related Kaposi sarcoma: evidence for direct stimulatory effect of glucocorticoid on cell proliferation . Am J Pathol 1995; 146:727–734. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hudnall SD, Rady PL, Tyring SK, Fish JC. Hydrocortisone activation of human herpes virus 8 viral DNA replication and gene expression in vitro . Transplantation 1999; 67:648–652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Murakami-Mori K, Mori S, Taga T, Kishimoto T, Nakamura S. Enhancement of gp130-mediated tyrosine phosphorylation of STAT3 and its DNA-binding activity in dexamethasone-treated AIDS-associated Kaposi's sarcoma cells: selective synergy between dexamethasone and gp130-related growth factors in Kaposi's sarcoma cell proliferation . J Immunol 1997; 158:5518–5526. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Cai J, Zheng T, Lotz M, Zang B, Masood R, Gill P. Glucocorticoids induce Kaposi's sarcoma cell proliferation through the regulation of transforming growth factor-beta . Blood 1997; 89:1491–1500. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]