Abstract

Elasmobranchs are one of the most diverse groups in the marine realm represented by 18 orders, 55 families and about 1200 species reported, but also one of the most vulnerable to exploitation and to climate change. Phylogenetic relationships among main orders have been controversial since the emergence of the Hypnosqualean hypothesis by Shirai (1992) that considered batoids as a sister group of sharks. The use of the complete mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) may shed light to further validate this hypothesis by increasing the number of informative characters. We report the mtDNA genome of the bonnethead shark Sphyrna tiburo, and compare it with mitogenomes of other 48 species to assess phylogenetic relationships. The mtDNA genome of S. tiburo, is quite similar in size to that of congeneric species but also similar to the reported mtDNA genome of other Carcharhinidae species. Like most vertebrate mitochondrial genomes, it contained 13 protein coding genes, two rRNA genes and 22 tRNA genes and the control region of 1086 bp (D-loop). The Bayesian analysis of the 49 mitogenomes supported the view that sharks and batoids are separate groups.

Keywords: Bonnethead, Mitogenome, Phylogeny, Hypnosqualea hypothesis

Abbreviations: ATP, Adenosine triphosphate; bp, Base pairs; CO, Cytochrome oxidase; Cytb, Cytochrome B; D-loop, Control region; mt, Mitochondrial; myr, Million years; ML, Maximum likelihood; ND, Nicotine adenine dehydrogenase; PCR, Polymerase chain reaction; rRNA, Ribosomal RNA; tRNA, Transference RNA

Highlights

-

•

The bonnethead shark mitogenome is quite similar in size to that of other Carcharhinidae species

-

•

Larger mitogenomes were observed for species from the most basal lineages

-

•

The ND2 gene showed the highest mean number of nucleotide differences at the inter-generic level within Carcharhiniformes

-

•

The Bayesian analysis of 49 Elasmobranch mitogenomes supported the view that sharks and batoids are separate groups

1. Introduction

Sharks are one of the oldest groups in nature with a diversification dated to have occurred 460–300 million years (myr) ago (Heinicke et al., 2009). As a consequence, sharks are one of the most diverse taxa in the marine realm, playing an important role in the ecosystems due to their position as top- or mid-level predators. This highlights the importance of diversity and the value of evolutionary studies regarding sharks since many species are exploited by humans around the world (Dulvy et al., 2014). Phylogenetic relationships at several levels ranging from superorders to families, or even genera within families, are still controversial. Although it has been widely accepted that modern sharks (Neoselachia) are monophyletic, the relationships among the four main superordinal groups (Galeomorphii, Squalomorphii, Squatinomorphii and Rajomorphii), and the arrangement of orders within these groups remain unsolved. As an example, whereas Bigelow and Schroeder (1948) suggested that batoids are a separate group from sharks, more recent morphological evidence provided by Shirai (1992) placed batoids as a group derived from sharks, which is known as the “hypnosqualean” hypothesis. Nevertheless, although most molecular studies suggest rejection of the hypnosqualean hypothesis, these studies are based on single nuclear or mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) genes or a set of sequences ranging from 2.4 to 5.8 kb (B45_Douady et al., 2003, B75_Winchell et al., 2004, B63_Naylor et al., 2005). Likewise, within orders some morphological studies have placed Squalomorphs and Squatinimorphs as the orbitostylic group, based on the sharing of a potential synapomorphy; a projection from the upper-jaw cartilage inside of the ocular orbit (Maisey, 1980).

Similarly, the systematic position of orders within Galeomorphii is unsolved; whereas morphological studies with no exception place Lamniformes as sister order of Carcharhiniformes (B38_Compagno, 1973, B42_de Carvalho, 1996), some molecular studies places Orectolobiformes as the sister group of Carcharhiniformes (Vélez-Suazo and Agnarsson, 2011). However, other studies confirm Lamniformes as the sister group of Carcharhiniformes (B45_Douady et al., 2003, B64_Naylor et al., 2012). Furthermore, within Carcharhiniformes there are some unsolved relationships as there are some families probably paraphyletic such as the hammerhead sharks, Sphyrnidae (Lim et al., 2010).

Many molecular phylogenies up to date are based on the use of individual genes. However, with the advent of Next Generation Sequencing (NGS) protocols, databases for species' complete mtDNA genomes have increased notably and the analyses of mitogenomes are providing new insights on phylogenetic reconstruction (Qin et al., 2015).

The bonnethead shark Sphyrna tiburo, is seasonally distributed within estuarine, coastal, and continental shelf waters in the western Atlantic from North Carolina, U.S. to southern Brazil, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean, including the eastern Pacific from southern California, USA to Ecuador (Compagno, 1984). Some studies based on acoustic and conventional tagging in estuarine waters of the Gulf of Mexico coast of Florida have suggested that S. tiburo is a long-term resident within a specific estuary, with low dispersal among different estuaries (B56_Heupel et al., 2006, B2_Bethea and Grace, 2013). The proclivity of individuals to remain or return for extended periods to areas where they were born is one of the main criteria for philopatry (Feldheim et al., 2014). These nursery areas are critical for protection of neonates and young juveniles and for subsequent recruitment into the adult population. Assessing genetic differences between populations is constrained by the use of single/individual genes because of the low genetic variation that characterizes mtDNA in elasmobranchs. The use of longer sequences or whole mtDNA genomes will increase the number of informative characters and thus our capability for defining phylogeographic patterns or philopatric signals in this species.

In this study we report the complete mitochondrial genome of S. tiburo using a protocol based on next generation sequencing and compared the resultant mitogenome with mtDNA genome sequences of other 48 shark and ray species including representatives from the orders Carcharhiniformes, Lamniformes, Orectolobiformes, Heterodontiformes, Pristiophoriformes, Rajiformes, Rhinobatiformes, Myliobatiformes, Torpediniformes and Pristiformes in order to assess the phylogenetic relationships between sharks and rays but also within Galeomorphii.

2. Materials and methods

A muscle tissue biopsy of bonnethead was obtained from commercial fishing boats operating in Campeche Mexico, and stored in the Laboratorio de Genética de Organismos Acuáticos at the Instituto de Ciencias del Mar y Limnología, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM). The genomic DNA was isolated using Wizard Genomics DNA Purification Kit (PROMEGA®).

For the library preparation the DNA was sheared by sonication with Bioruptor ® and the KAPA BIOSYSTEMS® library preparation protocol with slight modifications was followed. In brief, fragmented DNA was ligated to Illumina universal TruSeq adapters containing eight custom nucleotide indexes (Faircloth and Glenn, 2012). Fragments were size selected in a ~ 250–450 bp range and enriched through PCR, purified and normalized. A library for sequencing in Illumina MiSeq v3 600 cycle kit was prepared to produce paired-end 300 nucleotide reads at the Genomics Facility from the University of Georgia (UGA).

The total reads were quality filtered, assembled and annotated in Geneious® 7.1.5 using as reference the mtDNA genome of Sphyrna lewini (accession NC022679). We report the first complete sequence of the mitochondrial genome of bonnethead S. tiburo, obtained by NGS methods.

Our laboratory has assembled the complete mitogenome of other shark species as Sphyrna zygaena (KM489157), Carcharhinus leucas (KJ210595), Carcharhinus falciformis (KF801102) and Carcharodon carcharias (KJ934896). We used these mitogenomes and others available in GenBank (Table 1), to perform phylogenetic analyses comparing the orders of the subclasses Elasmobranchii; Carcharhiniformes, Lamniformes, Orectolobiformes and Heterodontiformes (Galeomorphii), Hexanchiformes, Squaliformes, Priostiophorifomes and Squatiniformes (Squalimorphii), Myliobatiformes, Rajiformes, Torpediformes and Pristiformes (Batoidea), and including the mtDNA genome of Callorhinchus milii (Chimaeriformes) as external group. A total of 49 mitogenomes were analyzed.

Table 1.

Elasmobranch species used in this study. Mitochondrial genomes from Pacific (PAC) and Gulf of Mexico (GM) individuals of Carcharhinus leucas.

| Order/species | Family | mtDNA size | GB ref. # | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carcharhiniformes | ||||

| Carcharhinus leucas (PAC) | Carcharhinidae | 16,704 | NC023522 | Chen et al. (2015b) |

| Carcharhinus leucas (GM) | Carcharhinidae | 16,702 | KJ210595 | Díaz-Jaimes et al. (2014) |

| Carcharhinus macloti | Carcharhinidae | 16,701 | NC024862 | Chen et al. (2014a) |

| Carcharhinus sorrah | Carcharhinidae | 16,707 | NC023521 | Chen et al. (2015c) |

| Carcharhinus acronotus | Carcharhinidae | 16,719 | NC024055 | Yang et al. (2014a) |

| Carcharhinus plumbeus | Carcharhinidae | 16,706 | NC024596 | Blower and Ovenden (2014) |

| Carcharhinus falciformis | Carcharhinidae | 16,680 | KF801102 | Galván-Tirado et al. (2014) |

| Carcharhinus obscurus | Carcharhinidae | 16,706 | NC020611 | Blower et al. (2013) |

| Carcharhinus melanopterus | Carcharhinidae | 16,706 | NC024284 | Chen et al. (2014b) |

| Carcharhinus amblyrhyncoides | Carcharhinidae | 16,705 | NC023948 | Feutry et al. (2014) |

| Prionace glauca | Carcharhinidae | 16,705 | NC022819 | Chen et al. (2015d) |

| Glyphis garricki | Carcharhinidae | 16,702 | NC023361 | Feutry et al. (2015) |

| Glyphis glyphis | Carcharhinidae | 16,701 | KF006312 | Chen et al. (2014c) |

| Galeocerdo cuvier cuvier | Carcharhinidae | 16,703 | NC022193 | Chen et al. (2014d) |

| Scoliodon macrorhynchos | Carcharhinidae | 16,693 | JQ693102 | Chen et al. (2014e) |

| Sphyrna zygaena | Sphyrnidae | 16,731 | KM489157 | Bolaño-Martínez et al. (2014) |

| Sphyrna lewini | Sphyrnidae | 16,726 | NC022679 | Chen et al. (2015a) |

| Sphyrna tiburo | Sphyrnidae | 16,723 | KM453976 | This study |

| Mustelus griseus | Triakidae | 16,754 | NC023527 | Chen et al. (2014f) |

| Mustelus manazo | Triakidae | 16,707 | NC000890 | Cao et al. (1998) |

| Scyliorhinus canicula | Scyliorhinidae | 16,697 | NC001950 | Delabre et al. (1998) |

| Lamniformes | ||||

| Carcharodon carcharias | Lamnidae | 16,744 | NC022415 | Chang et al. (2014a) |

| Lamna ditropis | Lamnidae | 16,699 | NC024269 | Chang et al. (2014b) |

| Isurus oxyrinchus | Lamnidae | 16,701 | NC022691 | Chang et al. (2015a) |

| Isurus paucus | Lamnidae | 16,704 | NC024101 | Chang et al. (2014c) |

| Cetorhinus maximus | Cetorhinidae | 16,670 | NC023266 | Hester et al. (2013) |

| Carcharias taurus | Odontaspididae | 16,773 | NC023520 | Chang et al. (2015b) |

| Alopias pelagicus | Alopiidae | 16,692 | NC022822 | Chen et al. (2015e) |

| Alopias superciliosus | Alopiidae | 16,719 | NC021443 | Chang et al. (2014d) |

| Megachasma pelagios | Megachasmidae | 16,694 | NC021442 | Chang et al. (2014e) |

| Mitsukurina owstoni | Mitskurinidae | 17,743 | NC011825 | Unpublished |

| Orectolobiformes | ||||

| Orectolobus japonicus | Orectolobidae | 16,706 | KF111729 | Chen et al. (2015f) |

| Rhyncodon typus | Rhincodontidae | 16,875 | NC023455 | Alam et al. (2014) |

| Chiloscyllium griseum | Hemiscylliidae | 16,755 | NC017882 | Chen et al. (2013) |

| Chiloscyllium plagiosum | Hemiscylliidae | 16,726 | NC012570 | Unpublished |

| Chiloscyllium punctatum | Hemiscylliidae | 16,703 | NC016686 | Chen et al. (2014g) |

| Heterodontiformes | ||||

| Heterodontus francisci | Heterodontidae | 16,708 | NC003137 | Arnason et al. (2001) |

| Heterodontus zebra | Heterodontidae | 16,720 | NC021615 | Chen et al. (2014h) |

| Squatiniformes | ||||

| Squatina formosa | Squatinidae | 16,690 | NC025328 | Corrigan et al. (2014) |

| Squatina japonica | Squatinidae | 16,689 | NC024276 | Chai et al. (2014) |

| Squaliformes | ||||

| Squalus acanthias | Squalidae | 16,738 | NC002012 | Rasmussen and Arnason (1999) |

| Cirrhigaleus australis | Squalidae | 16,543 | KJ128289 | Yang et al. (2014b) |

| Pristiophoriformes | ||||

| Pristiophorus japonicus | Pristiophoridae | 18,430 | NC024110 | Unpublished |

| Hexanchiformes | ||||

| Hexanchus griseus | Hexanchidae | 17,405 | KF894491 | Unpublished |

| Myliobatiformes | ||||

| Gymnura poecilura | Gymnuridae | 17,874 | NC_024102 | Chen et al. (2014i) |

| Torpediformes | ||||

| Narcine entemedor | Narcinidae | 17,081 | KM386678 | Castillo-Paez et al. (2014) |

| Rajiformes | ||||

| Rhinobatos schlegelii | Rhinobatidae | 16,780 | NC023951 | Chen et al. (2014j) |

| Zearaja chilensis | Rajidae | 16,909 | KJ913073 | Vargas-Caro et al. (2014) |

| Pristiformes | ||||

| Anoxypristis cuspidata | Pristidae | 17,243 | NC026307 | Chen et al. (2015g) |

| Chimaeriformes | ||||

| Callorhinchus milii | Callorhinchidae | 16,769 | NC014285 | Inoue et al. (2010) |

The sequences of the complete mitogenomes were aligned using the MUSCLE application available at Geneious® 7.1.5 with 8 iterations. From the alignment we obtained the positions of each gene, tRNA, rRNA, and control region. We evaluated the appropriate model of substitution in JModelTest obtaining the GTR + I + G as the most probable model. We obtained a graph of the consensus sequence (Fig. 1), as well as the graphical representation of the sequence alignment using Geneious version 7.1 created by Biomatters available from http://www.geneious.com. We also made a graphical comparison of the S. tiburo mitogenome with other shark mitogenomes available in GenBank (Table 1) through a BLAST using the CGView Comparison Tool (CCT) (Grant et al., 2012) (Fig. 2).

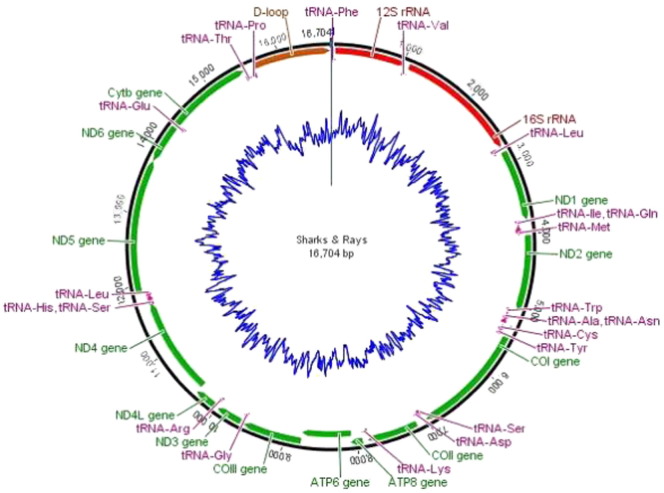

Fig. 1.

Gene organization map of the consensus sequence from the alignment of multiple shark and ray species. The protein-coding genes, tRNAs, rRNAs and non-coding regions are shown in different colors. The blue ring in the middle shows GC contents.

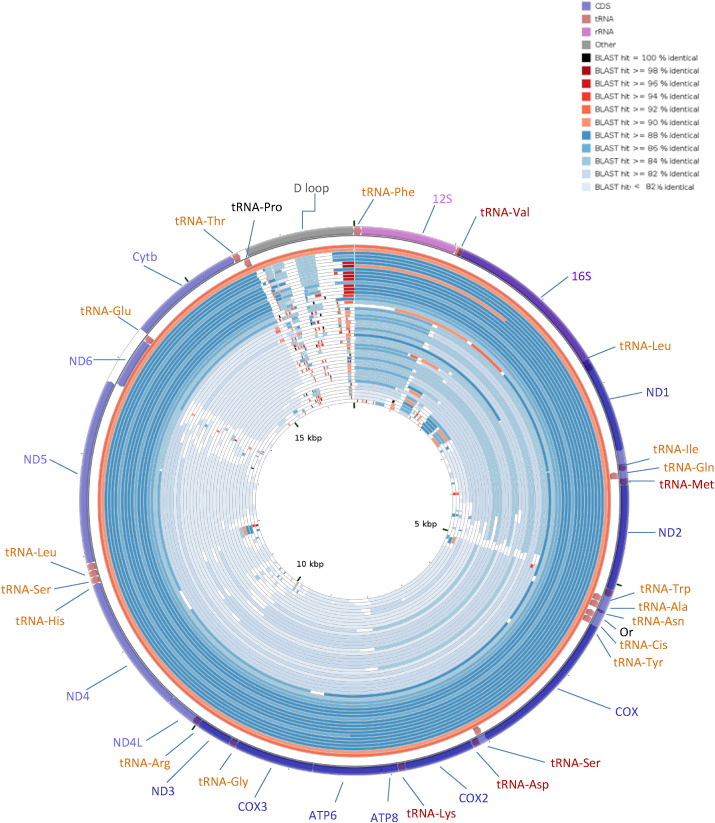

Fig. 2.

Graphical representation of the alignment results showing nucleotide identity between S. tiburo mitogenome and other 48 shark species, the first two external mitogenomes in red corresponds to S. lewini and S. zygaena respectively, followed by Carcharhinus sorrah, C. macloti, C. amblyrhynchoides, C. falciformis, C. plumbeus, C. acronotus, C. melanopterus, C. obscurus, Galeocerdo cuvier, Prionace glauca, Glyphis glyphis, G. garriki, Mustelus griseus, M. manazo, Scoliodon macrorhinchus, C. leucas, Alopias pelagicus, Charcharias taurus, A. supercilliosus, Heterodontus francisci, Cetorhinus maximus, Mitsukurina owstoni, Lamna ditropis, Orectolobus japonicus, Scyliorhinus canicula, Chiloscyllium punctatum, Heterodontus zebra, Isurus paucus, Carcharodon carcharias, Rhyncodon typus, Cirrhigaleus australis, Megachasma pelagios, Squalus acanthias, Chiloscyllium griseum, Isurus oxyrinchus, Chiloscyllium plagiosum, Squatina Formosa, S. japónica, Pristiophorus japonicus, Hexanchus griseus, Rhinobatos schlegelii, Anoxypristis cuspidata, Zearaja chilensis, Narcine entemedor, Gymnura poecilura, and Callorhinchus milii.

A partitioned Bayesian phylogenetic analysis excluding tRNAswas conducted with parallel version of Mr. Bayes 3.0b4 (Ronquist and Huelsenbeck, 2003) using 20,000 burn-in and 50,000,000 of generations. The unlink option was selected and also the gamma-shaped rate variation option, to allow each partition to run with its own set of parameters. Likewise a tree inference using a maximum likelihood (ML) algorithm in the partitioned data excluding tRNAs, was also made using the software RAxML-HPC v. 8 (Stamatakis, 2014) with the GTRCAT model, and 100 bootstrap replicates. We used an individual representative of Chimaeriformes (C. milii) as an external group. In order to identify those genes containing the higher number of variable sites useful to address divergence at the inter-generic level within Carcharhiniformes as well as the inter-specific level within the Carcharhinidae family, the mean number of differences at the nucleotide level for individual mtDNA genes was estimated.

3. Results and discussion

3.1 Genome structure and genetic variation

In this study we report the complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the bonnethead shark S. tiburo (GenBank accession number KM453976) of a specimen collected from Campeche, Gulf of Mexico. A total of 2,402,505 X2 paired reads were obtained, which after filtered and assembled resulted in the complete genome sequence containing 16,723 nucleotides. The S. tiburo mitogenome is quite similar in size to that of the congeneric species, S. lewini (16,726 bp; Table 2) (Chen et al., 2015a) and S. zygaena (16,731; Bolaño-Martínez et al., 2014) but also similar to the reported mtDNA genome of other Carcharhinidae species (range 16,680–16,754; Table 1). Like most vertebrate mitochondrial genomes, it contained 13 protein coding genes, two rRNA genes and 22 tRNA genes and the control region of 1086 bp (D-loop) (Table 2). All genes are arranged in a similar fashion as most of vertebrate mitogenomes (Fig. 1) and for most of them the starting codon (ATG) was identified with the exception of the CO subunit I (COI) gene which had GTG as starting codon. For most genes the stop codon (TAA) was identified except for some genes whereas incomplete codons were contained for ND2, ND3, ND4, ND6 (T-), and Cytb (TA-).

Table 2.

Comparison between mitogenomes of Sphyrna tiburo and S. lewini.

|

Sphyrna

tiburo |

Sphyrna

lewini |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | From (bp) | To (bp) | Size (bp) | Gene | From (bp) | To (bp) | Size (bp) |

| tRNAPhe | 1 | 72 | 72 | tRNAPhe | 1 | 71 | 70 |

| 12SrRNA | 73 | 1025 | 953 | 12S rRNA | 72 | 1027 | 955 |

| tRNAVal | 1026 | 1097 | 71 | tRNAVal | 1028 | 1099 | 71 |

| 16SrRNA | 1098 | 2768 | 1670 | 16S rRNA | 1100 | 2768 | 1.668 |

| tRNALeu | 2769 | 2843 | 74 | tRNALeu | 2769 | 2843 | 74 |

| ND1 | 2844 | 3818 | 974 | ND1 | 2844 | 3818 | 974 |

| tRNAIle | 3819 | 3887 | 68 | tRNAIle | 3819 | 3887 | 68 |

| tRNAGln | 3889 | 3960 | 71 | tRNAGln | 3889 | 3960 | 71 |

| tRNAMet | 3961 | 4029 | 68 | tRNAMet | 3961 | 4029 | 68 |

| ND2 | 4030 | 5074 | 1044 | ND2 | 4030 | 5074 | 1044 |

| tRNATrp | 5075 | 5145 | 70 | tRNATrp | 5075 | 5145 | 70 |

| tRNAAla | 5147 | 5215 | 68 | tRNAAla | 5147 | 5215 | 68 |

| tRNAAsn | 5216 | 5288 | 72 | tRNAAsn | 5216 | 5288 | 72 |

| tRNACys | 5323 | 5388 | 65 | tRNACys | 5324 | 5390 | 66 |

| tRNATyr | 5390 | 5459 | 69 | tRNATyr | 5392 | 5461 | 69 |

| COI | 5461 | 7017 | 1556 | COI | 5463 | 7019 | 1556 |

| tRNASer | 7018 | 7088 | 70 | tRNASer | 7020 | 7090 | 70 |

| tRNAAsp | 7092 | 7161 | 69 | tRNAAsp | 7094 | 7163 | 69 |

| COII | 7169 | 7859 | 690 | COII | 7171 | 7861 | 690 |

| tRNALys | 7860 | 7933 | 73 | tRNALys | 7862 | 7935 | 73 |

| ATP8 | 7935 | 8102 | 167 | ATP8 | 7937 | 8104 | 167 |

| ATP6 | 8093 | 8775 | 682 | ATP6 | 8095 | 8777 | 682 |

| COIII | 8776 | 9561 | 785 | COIII | 8778 | 9563 | 785 |

| tRNAGly | 9564 | 9633 | 69 | tRNAGly | 9566 | 9635 | 69 |

| ND3 | 9634 | 9982 | 348 | ND3 | 9636 | 9984 | 348 |

| tRNAArg | 9983 | 10,052 | 69 | tRNAArg | 9985 | 10,054 | 69 |

| ND4L | 10,053 | 10,349 | 296 | ND4L | 10,055 | 10,351 | 296 |

| ND4 | 10,343 | 11,723 | 1380 | ND4 | 10,345 | 11,725 | 1380 |

| tRNAHis | 11,724 | 11,792 | 68 | tRNAHis | 11,726 | 11,794 | 68 |

| tRNASer | 11,793 | 11,860 | 67 | tRNASer | 11,795 | 11,861 | 66 |

| tRNALeu | 11,861 | 11,932 | 71 | tRNALeu | 11,862 | 11,933 | 71 |

| ND5 | 11,933 | 13,762 | 1829 | ND5 | 11,934 | 13,763 | 1829 |

| ND6 | 13,758 | 14,279 | 521 | ND6 | 13,759 | 14,280 | 521 |

| tRNAGlu | 14,278 | 14,347 | 69 | tRNAGlu | 14,281 | 14,350 | 69 |

| Cyt B | 14,352 | 15,496 | 1144 | Cyt B | 14,353 | 15,497 | 1144 |

| tRNAThr | 15,497 | 15,568 | 71 | tRNAThr | 15,498 | 15,569 | 71 |

| tRNAPro | 15,571 | 15,639 | 68 | tRNAPro | 15,572 | 15,640 | 68 |

| D-loop | 15,640 | 16,731 | 1091 | D-loop | 15,641 | 16,726 | 1085 |

3.2 Genome length and gene divergence across the compared shark species

In general although all shark mitogenomes exhibited high similarities in size among species (Fig. 2), larger mitogenomes were observed for species from the most basal lineages, with the Japanese sawshark Pristiophorus japonicus (Squatiniformes) having the largest mtDNA genome (18,430 bp) followed by longtail butterfly ray Gymnura poecilura (17,874 bp) (Myliobatiformes) and the goblin shark Mitsukurina owstoni (17,743 bp) (Lamniformes). Among orders, the mtDNA genome was larger in the Squatiniformes (mean 17,018 ± 792.7), followed by Lamniformes (16,813.9 ± 327.7), Orectolobiformes (16,753 ± 71.3), Heterodontiformes (16,714 ± 8.5) and Carcharhiniformes (16,708.5 ± 15.3). Within the Carcharhiniformes, an important difference in size between the genus Carcharhinus (16,703.5 ± 10.2) and Sphyrna (16,726.7 ± 4.04) was observed. The main differences in mtDNA genome sizecorrespond to the high content of tandem repeats characterizing the control region in elasmobranchs (Castro et al., 2007; Poorvliet and Hoarau, 2013) which has been reported also for teleost fishes (B72_Stärner et al., 2004, B19_Chen et al., 2004).

S. tiburo had a similar size for the mtDNA genome as its congeneric species, S. lewini and S. zygaena. However within Carcharhiniformes, representatives of the Sphyrnidae family (genus Sphyrna sp.) had a slightly larger mtDNA genome (mean 16,727 ± 4.04) than representatives of the Carcharhinidae family (16,702 ± 8.5) (genus Carcharhinus, Galeocerdo, Glyphis, Prionace and Scoliodon) as resulted of a short insertion of 44 bp in the control region.

The alignment of the 48 representative sharks and rays species of the main elasmobranch orders (Fig. 2) allowed the identification of several informative mtDNA regions at different levels of phylogenetic analyses (e.g. ranging from the inter-generic level to the inter-specific level).

At the inter-generic level within Carcharhiniformes, the average of the mean number of nucleotide differences among sequences of the representative species (14) of five genera (Sphyrna, Carcharhinus, Galeocerdo, Glyphys, and Scoliodon), showed informative sites for some portions of the mtDNA genome; specifically the control region showed an average number of nucleotide differences (dxy) of 0.194, followed by genes ND2 (dxy = 0.153), Cytb (dxy = 0.151), and ND5 (dxy = 0.145). Although the control region showed a higher number of differences, it was characterized by several large portions of gaps among genera. In turn, ND2 has been used widely to assess phylogenetic relationships at the family level for elasmobranchs (Naylor et al., 2005), although genes ND4, Cytb and COI have been also used to evaluate relationships at the same level (Vélez-Zuazo and Agnarsson, 2011 and references therein).

At the inter-specific level within genus Carcharhinus, the most variable genes were ND2 (dxy = 0.091), ND5 (dxy = 0.09) and ND4 (dxy = 0.089) whereas the control region displayed among the lower variation (dxy = 0.050) similar to that of COI (dxy = 0.052). Based on analyses of the complete mtDNA genome of the speartooth shark Glyphis glyphis, of individuals from several river drainages of Australia (Feutry et al., 2014), the mtDNA genes ND5, ND2 and 12S, were identified also as informative at the intra-specific level (between populations) whereas the control region showed a lower amount of informative sites and was not informative for population differentiation. Similar results were reported for the zebra shark, Stegostoma fasciatum where the ND4 was the most informative gene at the intra-specific level as compared with the mtDNA control region (Dudgeon et al., 2009). Due to its faster mutational rate, the usefulness of the ND2 gene to address genetic divergence/phylogenetic questions at inter- and intra-specific level has been emphasized by Naylor et al. (2005, 2012), using a wide number of elasmobranch species.

3.3 Phylogenetic relationships

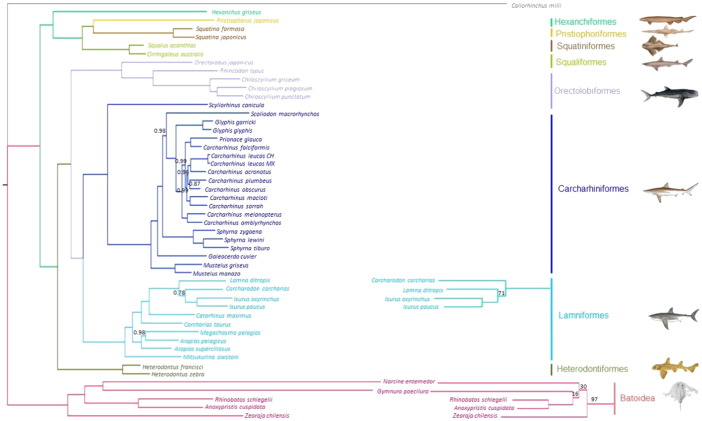

The mitogenomes of 48 shark and ray species representing the Galeomorphii, Squalomorphii, Squatinomorphii and Rajomorphii elasmobranch superorders were compared using C. milii (Chimaeriformes) as external group (Fig. 3). In general, by using the whole mtDNA genome the Bayesian and ML tree phylogenies were consistent with most molecular studies using individual mtDNA and/or nuclear genes (B45_Douady et al., 2003, B75_Winchell et al., 2004, B63_Naylor et al., 2005, B74_Vélez-Zuazo and Agnarsson, 2011), but differ from studies based on morphological data in supporting the main hypotheses. For example both, Bayesian and ML tree topologies were coincident on placing batoids (Rajidae (Pristiformes (Torpediformes, Myliobatiformes))), as sister group of sharks, rejecting the Hypnosqualea hypothesis of Shirai (1992) which suggested that Batoids are derived from sharks (see Douady et al., 2003 and references therein). The mitogenome evidence supported the previous hypothesis based on morphological data separating Batoids from sharks (Bigelow and Schroeder, 1948, 1953) and is also consistent with most of the molecular evidence showed by Duoady et al. (2003), Winchell et al. (2004) and Naylor et al. (2005) based on the analysis of 2.4–5.8 kbp including mtDNA and nuclear (Rag gene) data. Likewise, the monophyly of modern sharks or “Neoselachian” but with some differences in the arrangement of the 4 monophyletic superorders proposed by Compagno (1977) was clearly identified. The monophyly for three elasmobranch superorders as suggested by Maisey (1984) that organized neoselachians into three groups, the first based on the orbitostylic jaw suspension (Hexanchiformes, Squaliformes, Pristiophoriformes and Squatiniformes), the galeomorphs (Heterodontiformes, Orectolobiformes, Lamniformes and Carcharhiniformes) and batoids (skates and rays) and differs from the point of view of Compagno (1977) who placed Squatiniformes as a separated group of Squalimorfes and proposed four superorders (galeomorphs, squalomorphii, squatinimorphii and batoids) was confirmed. As a result, the monophyly for Squalimorphii was confirmed with the inclusion of Squatinimorfes, supporting the group with the orbitostylic jaw suspension (Hexanchiformes (Squaliformes (Squatiniformes, Pristiophoriformes))) according to the proposal of Maisey (1984) (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Left: Bayesian phylogenetic tree using whole mtDNA for sharks and rays showing the posterior probability values for branches (branches without numbers are values equal to 1.0). Right: Clades of the Maximum Likelihood tree which differ from the Bayesian analyses, only bootstrap values below 100% are shown.

Finally, within Galeomorphii, mtDNA genome sequences supported the association ((Lamniformes, Carcharhinifromes) Orectolobiformes) with Heterodontiformes in a basal position as suggested by de Carvalho (1996) and Shirai (1996) based on morphology and is also compatible with the molecular studies of Naylor et al. (2005) and Heincke et al. (2009) based on sequences of either the mtDNA and/or nuclear DNA, but differs from the views of Douady et al. (2003), Winchell et al. (2004), Human et al. (2006), Mallatt and Winchell (2007) and Vélez-Zuazo and Agnarsson (2011) who based on sequences of mtDNA and/or nuclear genes considered Lamniformes and Orectolobiformes as a sister group. Similarly, the mtDNA genome supported a sister relationship between Squatiniformes and Pristiophoriformes with Squaliformes being basal and Hexanchiformes as paraphyletic which is consistent with most of the molecular studies (B45_Douady et al., 2003, B63_Naylor et al., 2005, B62_Mallatt and Winchell, 2007 B57_Human et al., 2006, B74_Vélez-Zuazo and Agnarsson, 2011) but differs from the morphological evidence of Compagno (1973) and de Carvalho (1996) that found Pristioforiformes nested as sister group with Squaliformes and Batoidea respectively.

At the family level, it was not possible to confirm the monophyly for Carcharhinidae as the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier appeared as paraphyletic and Sphyrnidae, which was monophyletic, as sister taxa of Carcharhinidae. This arrangement was reported before by Vélez-Zuazo and Agnarsson (2011), and Naylor et al. (2012) based on sequences of several mtDNA genes. Finally, the monophyly for Lamnidae was confirmed with families ordered as follows; (Mitskurinidae (Alopiidae, Megachasmidae) (Odontaspididae (Cetorhinidae (Lamnidae))).

3.4 Conclusions

-

•

The mtDNA genome for Sphyrna tiburo was 16,723 bp, similar in size to that of other Sphyrnid sharks which were slightly longer than those of Carcharhinid sharks, containing similar number and arrangement of genes as most vertebrate mtDNAs.

-

•

The Bayesian and ML trees were similar to most of phylogenies based on molecular data and also to some other phylogenies based on morphological data confirming monophyly of Neoselachian and batoidea as sister group of sharks.

-

•

The ND2 gene was informative at several levels from the inter-generic to intra-specific, as suggested before. This information will be valuable to develop molecular markers to perform population genetic analyses directed to identify potentially key habitats as those used as nursery grounds.

Acknowledgments

We thank Nadia Sandoval Laurrabaquio, Elena Escatel Luna and Gabriela Martínez for sample collection and processing. This study was supported by the Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Investigación e Innovación Tecnológica, DGAPA-UNAM, grant IN208112.

References

- Alam M.T., Petit R.A., Read T.D., Dove A.D. The complete mitochondrial genome sequence of the world's largest fish, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus), and its comparison with those of related shark species. Gene. 2014;539:44–49. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.01.064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnason U., Gullberg A., Janke A. Molecular phylogenetics of gnathostomous (jawed) fishes: old bones, new cartilage. Zool. Scr. 2001;30:249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Bethea D.M., Grace M.A. SEDAR34-WP-04. SEDAR North Charleston SC; 2013. Tag and recapture data for Atlantic sharpnose, Rhizoprionodon terraenovae, and bonnethead shark, Sphyrna tiburo, in the Gulf of Mexico and US South Atlantic: 1998-2011. (19 pp) [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow H.W., Schroeder W.C. Sharks. In: Tee-Van J., Breder C.M., Hildebrand S.F., Parr A.E., Schroeder W.C., editors. Fishes of Western North Atlantic, Part 1. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1948. pp. 59–576. [Google Scholar]

- Bigelow H.W., Schroeder W.C. Sawfishes, guitarfishes, skates, and rays. In: Tee-Van J., Breder C.M., Hildebrand S.F., Parr A.E., Schroeder W.C., editors. Fishes of Western North Atlantic, Part 2. Yale University; New Haven, CT: 1953. pp. 1–514. [Google Scholar]

- Blower D.C., Ovenden J.R. The complete mitochondrial genome of the sandbar shark Carcharhinus plumbeus. Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.926487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blower D.C., Hereward J.P., Ovenden J.R. The complete mitochondrial genome of the dusky shark Carcharhinus obscurus. Mitochondrial DNA. 2013;24:619–621. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.772154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolaño-Martínez N., Bayona-Vasquez N., Uribe-Alcocer M., Díaz-Jaimes P. The mitochondrial genome of the hammerhead Sphyrna zygaena. Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.982574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao Y., Waddell P.J., Okada N., Hasegawa M. The complete mitochondrial DNA sequence of the shark Mustelus manazo: evaluating rooting contradictions to living bony vertebrates. Mol. Biol. Evol. 1998;15:1637–1646. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo-Páez A., Del Río-Portilla M.A., Rocha-Olivares A. The complete mitochondrial genome of the giant electric ray, Narcine entemedor (Elasmobranchii: Torpediniformes) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.963800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castro A.L.F., Stewart B.S., Wilson S.G., Hueter R.E., Meekan M.G. Population genetic structure of Earth's largest fish, the whale shark (Rhincodon typus) Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:5183–5192. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03597.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai A., Yamaguchi A., Furumitsu K., Zhang J. Mitochondrial genome of Japanese angel shark Squatina japonica (Chondrichthyes: Squatinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.919463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Shao K.T., Lin Y.S., Fang Y.C., Ho H.C. The complete mitochondrial genome of the great white shark, Carcharodon carcharias (Chondrichthyes, Lamnidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25(5):357–3588. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.803092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Jang-Liaw N.H., Lin Y.S., Carlisle A., Hsu H.H., Liao Y.C., Shao K.T. The complete mitochondrial genome of the salmon shark, Lamna ditropis (Chondrichthyes, Lamnidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.892095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Chiang W.C., Lin Y.S., Jang-Liaw N.H., Shao K.T. Complete mitochondrial genome of the longfin mako shark, Isurus paucus (Chondrichthyes, Lamnidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.913145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Shao K.T., Lin Y.S., Ho H.C., Liao Y.C. The complete mitochondrial genome of the big-eye thresher shark, Alopias superciliosus (Chondrichthyes, Alopiidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25(4):290–2922. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.792072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Shao K.T., Lin Y.S., Chiang W.C., Jang-Liaw N.H. Complete mitochondrial genome of the megamouth shark Megachasma pelagios (Chondrichthyes, Megachasmidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25(3):185–187. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.792068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Jabado R.W., Lin Y.S., Shao K.T. The complete mitochondrial genome of the sand tiger shark, Carcharias taurus (Chondrichthyes, Odontaspididae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26(5):728–729. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.845761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang C.H., Shao K.T., Lin Y.S., Tsai A.Y., Su P.X., Ho H.C. The complete mitochondrial genome of the shortfin mako, Isurus oxyrinchus (Chondrichthyes, Lamnidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26(3):475–476. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.834430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen C.A., Anonuevo Ablan M.C., McManus J.W., Bell J.D., Tuan V.S., Cabanban A.S., Shao K.T. Variable numbers of tandem repeats (VNTRs), heteroplasmy, and sequence variation of the mitochondrial control region in the threespot dascyllus, Dascyllus trimaculatus (Perciformes: Pomacentridae) Zoological Studies. 2004;43:803–812. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Ai W., Ye L., Wang X., Lin C., Yang S. The complete mitochondrial genome of the grey bamboo shark (Chiloscyllium griseum) (Orectolobiformes: Hemiscylliidae): genomic characterization and phylogenetic. Acta Oceanologica Sinica. 2013;32:59–65. [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu M., Grewe P.M., Kyne P.M., Feutry P. Complete mitochondrial genome of the critically endangered speartooth shark Glyphis glyphis (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25:431–432. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.809443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Shen X.J., Arunrugstichai S., Ai W., Xiang D. Complete mitochondrial genome of the blacktip reef shark Carcharhinus melanopterus (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.919483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu M., Xiao J., Yang W., Peng Z. Complete mitochondrial genome of the hardnose shark Carcharhinus macloti (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.930836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Yu J., Zhang S., Ding W., Xiang D. Complete mitochondrial genome of the tiger shark Galeocerdo cuvier (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25:441–442. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.809450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Peng X., Zhang P., Yang S., Liu M. Complete mitochondrial genome of the spadenose shark (Scoliodon macrorhynchos) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25(2):91–92. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.784751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Peng Z., Pan L., Shi X., Cai L. Mitochondrial genome of the spotless smooth-hound Mustelus griseus (Carcharhiniformes: Triakidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.873908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Zhou Z., Pichai S., Huang X., Zhang H. Complete mitochondrial genome of the brownbanded bamboo shark Chiloscyllium punctatum. Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25(2):113–114. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.786710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Peng X., Huang X., Xiang D. Complete mitochondrial genome of the Zebra bullhead shark Heterodontus zebra (Heterodontiformes: Heterodontidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014;25(4):280–281. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.796514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Ai W., Xiang D., Shi X. Mitochondrial genome of the longtail butterfly ray Gymnura poecilura (Myliobatiformes: Gymnuridae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.913148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Ai W., Xiang D., Pan L., Shi X. Complete mitogenome of the brown guitarfish Rhinobatos schlegelii (Rajiformes, Rhinobatidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.892091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Xiang D., Ai W., Shi X. Complete mitochondrial genome of the blue shark Prionace glauca (Elasmobranchii: Carcharhiniformes) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26(2):313–314. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.825790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Xiang D., Ai W., Shi X. Complete mitochondrial genome of the pelagic thresher Alopias pelagicus (Lamniformes: Alopiidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26:323–324. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.830294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Xiang D., Xu Y., Shi X. Complete mitochondrial genome of the scalloped hammerhead Sphyrna lewini (Carcharhiniformes: Sphyrnidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26(4):621–622. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.834432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu M., Peng Z., Shi X. Mitochondrial genome of the bull shark Carcharhinus leucas (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26(6):813–814. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.855906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Peng Z., Cai L., Xu Y. Mitochondrial genome of the spot-tail shark Carcharhinus sorrah (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26(5):734–735. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.845764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Liu M., Xiang D., Ai W. Complete mitochondrial genome of the Japanese wobbegong Orectolobus japonicus (Orectolobiformes: Orectolobidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;25(1):153–154. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.819499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X., Kyne P.M., Pillans R.D., Feutry P. Complete mitochondrial genome of the endangered narrow sawfish Anoxypristis cuspidata (Rajiformes: Pristidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.1003898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Compagno L.J.V. Interrelationships of living elasmobranchs. Zool. J. Linnean Soc. 1973;53:15–61. [Google Scholar]

- Compagno L.J.V. Phylogenetic relationships of living sharks and rays. Am. Zool. 1977;17:303–322. [Google Scholar]

- Compagno L.J.V. FAO Fisheries Synopsis N° 125, 4 (1 and 2) 1984. Sharks of the world. An annotated and illustrated catalogue of sharks species known to date. (655 pp) [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan S., Yang L., Cosmann P.J., Naylor G.J. A description of the mitogenome of the endangered Taiwanese angelshark, Squatina formosa. Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.945568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Carvalho M.R. Higher-level elasmobranch phylogeny, basal squaleans, and paraphyly. In: Stassny M.L.J., Parenti L.R., Johnson G.D., editors. Interrelationships of Fishes. Academic Press; San Diego: 1996. pp. 35–62. [Google Scholar]

- Delarbre C., Spruyt N., Delmarre C., Gallut C., Barriel V., Janvier P., Laudet V., Gachelin G. The complete nucleotide sequence of the mitochondrial DNA of the dogfish, Scyliorhinus canicula. Genetics. 1998;150:331–344. doi: 10.1093/genetics/150.1.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Jaimes P., Uribe-Alcocer M., Hinojosa-Alvarez S., Sandoval-Laurrabaquio N., Adams D.H., García De León F.J. The complete mitochondrial DNA of the bull shark (Carcharhinus leucas) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.913157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douady C.J., Dosay M., Shivji M.S., Stanhope M.J. Molecular phylogenetic evidence refuting the hypothesis of Batoidea (rays and skates) as derived sharks. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2003;26:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s1055-7903(02)00333-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudgeon C.L., Broderick D., Ovenden J.R. IUCN classification zones concord with, but underestimate, the population genetic structure of the zebra shark Stegostoma fasciatum in the Indo-West Pacific. Mol. Ecol. 2009;18:248–261. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2008.04025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulvy N.K., Fowler S.L., Musick J.A. Extinction risk and conservation of the world's sharks and rays. eLife. 2014;3 doi: 10.7554/eLife.00590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faircloth B.C., Glenn T.C. Not all sequence tags are created equal: designing and validating sequence identification tags robust to indels. PLoS One. 2012;7(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldheim K.A., Gruber S.H., DiBattista J.D., Babcock E.A., Kessel S.T., Hendry A.P., Pikitch E.K., Ashley M.V., Chapman D.D. Two decades of genetic profiling yields first evidence of natal philopatry and long-term fidelity to parturition sites in sharks. Mol. Ecol. 2014;23:110–117. doi: 10.1111/mec.12583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feutry P., Pillans R.D., Kyne P.M., Chen X. Complete mitogenome of the graceful shark Carcharhinus amblyrhynchoides (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.892094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feutry P., Grewe P.M., Kyne P.M., Chen X. Complete mitogenomic sequence of the critically endangered northern river shark Glyphis garricki (Carcharhiniformes: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2015;26(6):855–856. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.861428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galván-Tirado C., Hinojosa-Alvarez S., Diaz-Jaimes P., Marcet-Houben M., García-De-León F.J. The complete mitochondrial DNA of the silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.878922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant J.R., Arantes A.S., Stothard P. Comparing thousands of circular genomes using CGView comparison tool. BMC Genomics. 2012;13:202. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-13-202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinicke M.P., Naylor G.J.P., Hedges S.B. Cartilaginous fishes (Chondrichthyes) In: Hedges S.B., Kumar S., editors. The Timetree of Life. Oxford University Press; New York: 2009. p. 320. [Google Scholar]

- Hester J., Atwater K., Bernard A., Francis M., Shivji M.S. The complete mitochondrial genome of the basking shark Cetorhinus maximus (Chondrichthyes, Cetorhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2013 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.845762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heupel M.R., Simpfendorfer C.A., Collins A.B., Tyminski J.P. Residency and movement patterns of bonnethead sharks, Sphyrna tiburo, in a large Florida estuary. Environ. Biol. Fish. 2006;76:47–67. [Google Scholar]

- Human B.A., Owen E.P., Compagno L.J.V., Harley E.H. Testing morphologically based phylogenetic theories within the cartilaginous fishes with molecular data, with special reference to the catshark family (Chondrichthyes; Scyliorhinidae) and the interrelationships within them. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2006;39:384–391. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue J.G., Miya M., Lam K., Tay B.H., Danks J.A., Bell J., Walker T.I., Venkatesh B. Evolutionary origin and phylogeny of the modern holocephalans (Chondrichthyes: Chimaeriformes): a mitogenomic perspective. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2010;27:2576–2586. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msq147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim D.D., Motta P., Mara K., Martin A.P. Phylogeny of hammerhead sharks (family Sphyrnidae) inferred from mitochondrial and nuclear genes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2010;55:572–579. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisey J.G. An evaluation of jaw suspension in sharks. Am. Mus. Novit. 1980;2706:1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Maisey J.G. Higher elasmobranch phylogeny and biostratigraphy. Zool. J. Linnean Soc. 1984;82:33–54. [Google Scholar]

- Mallatt J., Winchell C.J. Ribosomal RNA genes and deuterostome phylogeny revisited: more cyclostomes, elasmobranchs, reptiles, and a brittle star. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2007;43:1005–1022. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2006.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naylor G.J.P., Ryburn J.A., Fedrigo O., López J.A. Phylogenetic relationships among the major lineages of modern elasmobranchs. In: Hamlett W.C., Jamieson B.G.M., editors. Reproductive Biology and Phylogeny. Vol. 3. Science Publishers, Inc.; Enfield, NH: 2005. pp. 1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Naylor G.J.P., Caira J.N., Jensen K., Rosana K.A.M., White W.T., Last P.R. A sequence based approach to the identification of shark and ray species and its implications for global elasmobranch diversity and parasitology. Bull. Am. Mus. Nat. Hist. 2012;367 (262 pp) [Google Scholar]

- Poorvliet M., Hoarau G. The complete mitochondrial genome of the spinetail devilray, Mobula japonica. Mitochondrial DNA. 2013;24:28–30. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2012.716051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin J., Zhang Y., Zhou X., Kong X., Wei S., Ward R.D., Zhang A. Mitochondrial phylogenomics and genetic relationships of closely related pine moth (Lasiocampidae: Dendrolimus) species in China, using whole mitochondrial genomes. BMC Genomics. 2015;16:428–439. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1566-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rasmussen A.S., Arnason U. Phylogenetic studies of complete mitochondrial DNA molecules place cartilaginous fishes within the tree of bony fishes. J. Mol. Evol. 1999;48:118–123. doi: 10.1007/pl00006439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronquist F., Huelsenbeck J.P. MRBAYES 3: Bayesian phylogenetic inference under mixed models. Bioinformatics. 2003;19:1572–1574. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btg180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shirai S. Hokkaido University Press; Sapporo: 1992. Squalean Phylogeny: A New Framework of “Squaloid” Sharks and Related Taxa. 151 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Shirai S. Phylogenetic interrelationships of Neoselachians (Chondrichthyes: Euselachii) In: Stiassny M.L.J., Parenti L.R., Johnson G.D., editors. Interrelationships of Fishes. Academic Press San Diego; 1996. pp. 9–34. [Google Scholar]

- Stamatakis A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014;30(9):1312–1313. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stärner H., Pahlsson C., Lindén M. Tandem repeat polymorphism and heteroplasmy in the mitochondrial DNA control region of threespine stickleback (Gasterosteus aculeatus) Behavior. 2004;51:1357–1369. [Google Scholar]

- Vargas-Caro C., Bustamante C., Bennett M.B., Ovenden J.R. The complete validated mitochondrial genome of the yellownose skate Zearaja chilensis (Guichenot 1848) (Rajiformes, Rajidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.945530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vélez-Zuazo X., Agnarsson I. Shark tales: a molecular species-level phylogeny of sharks (Selachimorpha, Chondrichthyes) Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2011;58:207–217. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winchell C.J., Martin A.P., Mallatt J. Phylogeny of elasmobranchs based on LSU and SSU ribosomal RNA genes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2004;31:214–224. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Matthes-Rosana K.A., Naylor G.J. Complete mitochondrial genome of the blacknose shark Carcharhinus acronotus (Elasmobranchii: Carcharhinidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.878928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L., Matthes-Rosana K.A., Naylor G.J. Determination of complete mitochondrial genome sequence from the holotype of the southern Mandarin dogfish Cirrhigaleus australis (Elasmobranchii: Squalidae) Mitochondrial DNA. 2014 doi: 10.3109/19401736.2014.908360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]