Abstract

Jail inmates represent a high-risk, multi-need population. Why do some jail inmates not access available programs and services? Drawn from a longitudinal study, 261 adults were assessed shortly upon incarceration and re-assessed prior to transfer or release from a county jail. Of the participants in need of treatment, 18.5% did not participate in any formal treatment programs or religious programs and services. Untreated inmates were disproportionately young and male and less likely to report pre-incarceration cocaine dependence. Treatment participation varied little as a function of race or symptoms of mental illness. The most common reason for non-participation was the belief that one would not be around long enough to participate in programs. Other reasons were both institution-related and person-related in nature, including doubts about treatment efficacy, stigma concerns, lack of motivation, and lack of programs, especially addressing mental illness.

Jail inmates represent a high-risk, multi-need population. Reported rates of mental illness and pre-incarceration substance abuse vary depending on what aspect of the criminal justice system is sampled, but by any measure, this is a population in need of treatment. For example, the Bureau of Justice Statistics (2006) estimates that, of the 2.4 million people currently incarcerated in the U.S., 56% of State prisoners, 45% of Federal prisoners, and 64% of jail inmates suffer from a diagnosable mental illness. Using more conservative criteria, Magaletta, Diamond, Faust, Daggett, Camp (2009) estimated that 15% of newly committed federal inmates required some level of service to address mental illness. Regarding substance use, Belenko and Peugh (2005) estimated that 82% of state prison inmates are “substance involved” and in a study of state prison inmates, Peters, Greenbaum, Edens, Carter, and Oritz (1998) found that 56% met criteria for a substance use disorder in the 30 days prior to incarceration. In our own assessment of jail inmates recently incarcerated on felony charges, 76.5% exhibited clinically significant symptoms of mental illness and/or substance abuse problems (Drapalski, Youman, Stuewig, & Tangney, 2009). Co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders are especially high. Belenko, Lang and O’Connor (2003) found that 66% of felony drug offenders reported clinically significant psychiatric symptoms. Thus, the need for mental health and substance abuse treatment is high. Moreover, simply by virtue of being incarcerated, many jail inmates are in crisis, facing a multitude of problems upon incarceration and further challenges upon release, including limited housing, employment, and educational opportunities; disrupted family relationships and other social support networks; and the stigma of being an “ex-con.” Behind bars, with time on their hands, facing myriad existing and future challenges, why do some jail inmates not access available programs and services? What barriers inhibit some inmates from participating in jail programs and treatment?

Person-Related and Treatment-Related Barriers to Treatment

Saunders, Zygowicz, and D’Angelo (2006) distinguished between two types of barriers to treatment seeking -- person-related barriers (cognitive and emotional factors – e.g., negative attitudes towards treatment, fear of stigma) and treatment-related barriers (availability, cost, and treatment format). In their study of a community sample in need of alcohol treatment, Saunders, et al. (2006) found that person-related barriers were most commonly endorsed as reasons for not seeking treatment. In contrast, in a national telephone survey regarding mental health treatment, Farberman (1997) found that treatment-related barriers (e.g. cost, lack of insurance coverage) were most commonly endorsed as reasons for not seeking treatment for emotional concerns. This distinction between treatment-related and person-related barriers is an important one, especially in terms of approaches to reducing or removing barriers to treatment. Reducing person-related barriers requires addressing individual attitudes and beliefs whereas reducing treatment-related barriers requires a more systemic approach.

Barriers to treatment within the incarcerated population

Barriers to treatment for the incarcerated population differ somewhat from those in the community. Many treatment-related barriers common in community settings, such as cost, lack of insurance, and transportation (Dearing & Twaragowski, 2010) are irrelevant to inmates, while there are other barriers specific to the correctional environment (Mitchell & Latchford, 2010; Morgan, Rozycki & Wilson, 2004).

Correctional facilities are not generally treatment oriented in nature, resources are limited, and thus appropriate treatment programs are often simply not available (Belenko & Peugh, 2005). Treatment availability is especially likely to be limited in local jails as opposed to state and federal prisons (Taxman, Perdoni & Harrison, 2007), and in smaller as opposed to larger jails (Steadman & Veysey, 1997). Appropriate treatment is often not available for certain subgroups of inmates, such as the severely mentally ill (Lamb, Weinberger & Gross, 2004) and inmates with co-occurring disorders (Belenko, Lang & O’Connor, 2003; Peters, LeVasseur & Chandler, 2004). Even when programs are offered, there may be long wait lists for appropriate services.

In addition, there may be person-related barriers specific to the correctional environment. For instance, inmates in need of treatment may have confidentiality concerns, concerns regarding the potential for information to be used against them by correctional officials, and a lack of trust in therapists and other treatment providers (Mitchell & Latchford, 2010; Morgan, Rozycki & Wilson, 2004).

Little research has systematically examined inmates’ reasons for not participating in treatment and services. A few studies have examined inmates’ perceptions of mental health services and perceived barriers to treatment (e.g., Mitchell & Latchford, 2010; Morgan, Rozycki & Wilson, 2004), but these studies focused on inmates in general, not specifically those in need of treatment and not those who chose not to engage in treatment. The current study is unique in focusing specifically on inmates in need of treatment for mental health or substance abuse concerns, including separate analyses of the subgroup of inmates of greatest interest – those in need who did not make use of relevant treatment and services of any kind.

In addition, existing studies of inmates examining treatment barriers have focused on the male prison population. It is unclear whether these results would generalize to jail populations and/or to incarcerated females. The distinction between jails and prisons is an important one. Whereas state and federal prisons house post-trial inmates with relatively lengthy known sentences, local jails serve as the “front door” of the U.S. correctional system. This is where arrestees arrive, where they are first processed, where they await trial and sentence, and where they serve out relatively short terms (e.g., less than one year, although this varies somewhat by state). So length of stay is much shorter and much more unpredictable in jails as opposed to prison, presenting some unique treatment challenges. At the same time, jail-based treatment is important to public health and safety. Far more people pass through local jails than prisons. For example, in 2010, 12,875,062 inmates were released from local jails (Minton, 2010) vs. a 2009 study counting 729,295 released from prisons (West et al., 2010). In short, jail inmates have a direct and immediate impact on the community.

The Current Study

The current study was designed to examine barriers to treatment participation among jail inmates with clinically significant mental health and substance dependency problems. In doing so, this study addresses the issue of why jail inmates in need often do not seek or receive help for mental health concerns, even when common treatment-related barriers (such as cost, time, and transportation) are removed.

Treatment as defined for this study included mental health and substance abuse services such as support groups, psychoeducational groups, and substance abuse groups. In addition, because individuals in need of psychological services may opt for (and are often referred to) more informal sources of help, such as churches and the clergy (Matthews, Corrigan, Smith, & Aranda, 2006; El-Khoury, Dutton, Goodman, Engel, Belamaric, & Murphy, 2004; Bermúdez, Kirkpatrick, Hecker, & Torres-Robles, 2010), religious services and programs (e.g. Bible, Quran study) were considered as treatment resources for the purposes of this study.

The specific aims of this study were (a) to determine the percentage of jail inmates with clinically significant symptoms of psychological disorders and/or substance dependency who do not participate in programs or treatment, (b) to assess whether non-treatment participating inmates differed by gender, ethnicity and/or type of clinical symptoms from their peers in need who did access programs and services; and (c) to identify the most common barriers to treatment while incarcerated as perceived by those who did not access treatment.

Methods

Participants

Participants were 261 adults (180 males and 81 females) held on felony charges in a 1100 bed county jail located just outside Washington, DC. These data were gathered as part of a larger on-going longitudinal study of moral emotions and criminal recidivism (Tangney, Mashek & Stuewig, 2007). Because an interest of the larger project was the effectiveness of short-term interventions, selection criteria were developed to identify incoming inmates likely to serve at least 4 months (i.e., long enough to complete the 5 session baseline assessment and to have the opportunity to request and engage in at least some jail programs and services). Thus, selection criteria were (1) either (a) sentenced to a term of 4 months or more, or (b) arrested and held on at least one felony charge other than probation violation, with no bond or greater than $7,000 bond, (2) assigned to the jail’s medium and maximum security “general population” (e.g., not in solitary confinement owing to safety and security issues, not in a separate forensics unit for actively psychotic inmates), and (3) sufficient language proficiency to complete study protocols in English or Spanish.

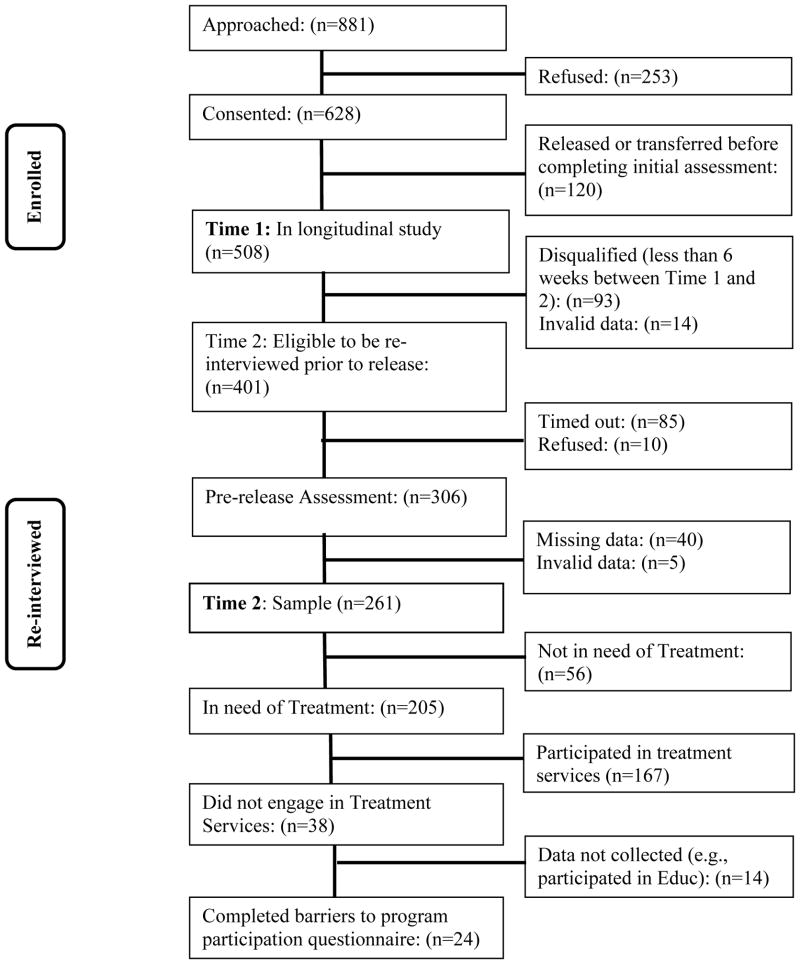

All procedures were reviewed and approved by the GMU Human Subjects Review Board. Eligible inmates were provided with a description of the longitudinal study and assured of the voluntary and confidential nature of the project. (A Certificate of Confidentiality from DHHS was secured to ensure the confidentiality of the data). Of the 881 inmates approached 628 consented (71%); 508 completed valid essential portions of the initial assessment (i.e. were not transferred or released to bond before the assessments could be completed) and were followed longitudinally. Participants received a $15 – $18 honorarium for the 5 session baseline assessment and a $25 honorarium for completing the pre-transfer or pre-release interview.

Inmates were eligible for the pre-release or pre-transfer interview if they remained at the jail for a minimum of 6 weeks following the baseline assessment (thus allowing time to request and enroll in treatment and services). Of the 508 participants who completed baseline assessment, 401(79%) were eligible for the pre-release or pre-transfer interview. Many participants did not qualify for the pre-release assessment because they were released prior to the 6 week mark. Additionally, several participants did not qualify for pre-release assessment due to having invalid data based on the PAI infrequency and inconsistency scales at the baseline assessment. Sample retention is diagrammed in Figure 1. We re-interviewed 306 of the 401 (76%) inmates eligible for a pre-release or pre-transfer interview. The most common reason for not completing the interview was an unscheduled release due to a court appearance or due to bond out. Among those re-interviewed, several participants completed abbreviated versions of the interview or only completed a portion of the full version, leading to missing data on program participation. Several participants were determined to have invalid data based on the PAI infrequency and inconsistency scales at the pre-release assessment, and thus were removed from analyses, resulting in a final sample of 261 participants. Attrition analyses (comparing eligible individuals who were re-interviewed vs. those who were not) evaluated baseline differences on 34 variables from a variety of domains including demographics (e.g. sex, education), mental health (e.g. schizophrenia, borderline), psychological (e.g. shame, self-control), criminality (e.g. criminal history, psychopathy), and substance dependence symptoms (e.g. alcohol, opiates). Attrition analyses indicated no differences beyond what would be expected by chance1.

Figure 1.

Sample Retention.

The sample was diverse in terms of ethnicity: 47.5% were African-American, 36.8% were Caucasian, 5% were Hispanic, 1.9% were Asian/Pacific Islander, and 8.9% were other. The average age of participants was 32.8 years (SD = 9.9; range of 18 to 69 years). The average education of participants was 11.7 years (SD = 2.1; range of 5 to 19 years).

Measures

Psychopathology

Clinically significant levels of mental illnesses were assessed with the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI; Morey, 1991), a 344 item self-report measure that yields 11 clinical scales, four validity scales, five treatment scales, and two interpersonal scales. For the purpose of this study, participants with one or more T-scores ≥ 70 on the PAI clinical scales of depression (DEP), anxiety (ANX), schizophrenia (SCZ), mania (MAN), borderline features (BPD), paranoia (PAR), somatization (SOM) and each subscale of the Anxiety Related Disorders scale including phobias (ARDP),obsessive compulsive symptoms (ARDO), and traumatic stress (ARDS) were determined to have clinically significant symptoms; 57% of participants (53.2% of women and 58.7% of men) met this criterion. More detail on symptomotology for the total sample and by gender can be found in Drapalski, Youman, Stuewig and Tangney (2009) and by race, see Youman, Drapalski, Stuewig, Bagley and Tangney (2010).

Substance Use and Dependence Symptoms were assessed using Simpson and Knight’s (1998) Texas Christian University: Correctional Residential Treatment Form, Initial Assessment (TCU-CRTF). Specifically, four scales were created to assess symptoms of dependency on alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and opiates in the year prior to incarceration. Each scale was composed of items that assess symptoms in each of the DSM-IV-TR (APA, 2000) substance dependence domains (e.g., for the domain of tolerance participants answered the question “How often did you find that your usual number of drinks had much less effect on you or that you had to drink more in order to get the effect you wanted?”). For domains with multiple items, responses were averaged and a total score was computed by taking the mean across the domains (α = .92 to .98). To select those “in need,” in keeping with DSM guidelines, participants who endorsed any symptoms in three or more of the domains for any substance were included in the analyses; 66.8% of participants (65.4% of women and 67.4% of men) met this criterion.

Program/Treatment Involvement including participation in support groups, alcohol/ substance abuse groups, psychoeducational groups, and religious services and religious study was obtained via interviews just prior to inmates’ transfer or release. Of primary interest is participation (or non-participation) in services aimed specifically at treating mental health and alcohol and substance dependency. For the purpose of the current study this includes support groups, psychoeducational groups and alcohol/drug abuse services. Support group programs include jail support groups and process-oriented psychotherapy groups (open to all inmates). Psychoeducational groups included those groups focused on teaching specific behavioral and/or cognitive skills such as conflict resolution, anger management, or parenting skills. Alcohol and drug services included groups and programs aimed at providing skills and/or support to help participants stay sober such as AA, NA, and individual or group substance abuse treatment. Religious services and groups were also available for participants, and although these programs were less focused on treatment for mental health and substance dependence issues, they were included as representative of informal treatment options. Participation in educational programs, such as GED classes, occupational training, and college courses was deemed to be unrelated to treatment of mental health and substance abuse and was therefore excluded from analyses.

Inmates who did not participate in any programs during their period of incarceration were asked, “What were your reasons for not participating in any programs?” They were then read a list of 9 reasons why some people may not participate and were asked to endorse items that were true for them. These items included: “I had participated in all the programs before”, “I didn’t think any of the programs would be helpful”, “I didn’t feel like doing anything”, “ I wasn’t accepted into the programs I wanted”, “I was embarrassed to face the staff or volunteers”, “I didn’t think I would be around long enough to participate in programs”, “I didn’t know what programs were offered”, “ The programs I wanted weren’t offered”, and “I was put on a waiting list and never got in”.

Procedures

Shortly after incarceration, participants completed the Personality Assessment Inventory (PAI; Morey, 1991) and the TCU-CRTF assessment of substance use and dependence using “touch-screen” computers that require minimal familiarity with computers (e.g., no keyboard, no mouse). In addition to presenting questionnaire items visually, the computer read each item aloud to all participants via headphones, thus accommodating participants with limited reading proficiency. Shortly prior to transfer or release from the jail, participants were administered questions regarding treatment and program participation via face-to-face interviews. Regarding confidentiality, interviews and computer-assisted assessments were conducted in the privacy of professional visiting rooms, used by attorneys, or secure classrooms.

Results

Percentage of Inmates in Need not Receiving Treatment

A total of 205 (79.5%) participants were determined to be in need of treatment based on PAI and TCU-CRTF scores. Of those in need, 66.7% participated in formal mental health or substance abuse treatment. Specifically, 41.9% participated in psychoeducational groups, 21.1% in support groups, and 42.4% in drug or alcohol abuse treatment groups (typically volunteer-led 12-step groups). In addition, 55.4% of participants in need attended religious services or some sort of religious group.

A total of 18.5% of all inmates with symptoms of mental illness or substance dependence, or both, did not participate in any of the formal treatment programs or religious programs and services available to them during their period of incarceration. The vast majority of inmates in need who did not participate in any form of treatment were men (25.4% men vs. 3.2% of women inmates in need), χ2 (1, N = 205) = 14.21, p =.000. Because it was not unusual for inmates to participate in more than one program, we conducted separate analyses for each type of treatment, evaluating whether the percentage of inmates who participated in the program vs. not significantly differed by gender. Within formal treatment options, female inmates in need participated at a significantly higher rate than males in need in psychoeducational groups, χ2 (1, N = 203) = 18.81, p = .000, and support groups, χ2 (1, N = 204) = 8.23, p =.004. Females in need did not participate in drug and alcohol programs at a significantly higher rate than males in need, χ2 (1, N = 203) = 3.64, p =.056. Females were also significantly more likely to attend religious services, χ2 (1, N = 204) =17.62, p = .000 and religious groups χ2 (1, N = 204) = 20.96, p = .000. (For a report on gender differences in treatment seeking as opposed to participation in this sample, see Drapalski, Youman, Stuewig, & Tangney, 2009.)

A series of Chi-square analyses comparing participation rates for Caucasian, African American and Hispanic inmates in need found no significant differences, except in participation in drug and alcohol programs. Hispanic inmates participated at a significantly higher rate than Caucasian and African American inmates, χ2 (2, N = 186) = 6.86, p = .032; 76.9% of Hispanic inmates in need of treatment (N = 10) participated in drug or alcohol treatment compared to 38.8% of African American inmates (N = 38), and 45.3% of Caucasian inmates (N = 34). In sharp contrast to community samples, regardless of ethnicity, inmates in need participated at similar rates for most types of treatment programs (for a report on race differences in treatment seeking as opposed to participation see Youman, Drapalski, Stuewig, Bagley, & Tangney, 2010).

We also conducted a series of one-way ANOVAs examining whether treatment participation differed by inmate age. Inmates in need who did not participate in any type of treatment program were significantly younger (M = 28.76 years, SD = 7.37) than those that did participate in any treatment (M = 33.71 years, SD = 9.64; F = 8.83, p = .003). In fact, the mean age of those inmates who did not participate was younger for all treatment and service options, save for a non-significant trend in the same direction for participation in religious groups.

Bivariate (point biserial) correlations examined the relationship between mental health and substance dependence symptoms and treatment participation (see Table 1). Treatment participation varied little in terms of mental health symptoms. Depression was positively related only to participation in support groups while anxiety was positively correlated with formal treatment involvement. Symptoms of mania and schizophrenia were unrelated to participation in treatment or services. Symptoms of borderline personality disorder were positively associated with involvement in formal treatment programs, especially drug/alcohol programs. Surprisingly, somatic complaints were positively related to involvement in formal and informal treatment participation, such as support programs, drug and alcohol programs, and religious groups. Symptoms of traumatic stress were associated with participation in formal programs as well as support groups and religious groups.

Table 1.

Correlations between Mental Health Symptoms/Substance Dependence Symptoms and Treatment Participation.

| No Treatment | Formal Treatment | Psych-ed. Groups | Support Groups | Drug/Alcohol Programs | Religious Programs | Religious Services | Religious Groups | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression symptoms | −.09 | .13 | .05 | .15* | .07 | .04 | −.03 | .09 |

| Anxiety symptoms | −.11 | .15* | .08 | .09 | .11 | .03 | −.05 | .08 |

| Mania symptoms | .02 | −.02 | .02 | −.03 | .06 | .02 | −.01 | .07 |

| Schizophrenia symptoms | −.06 | .11 | .04 | .12 | .10 | .00 | −.04 | .04 |

| Borderline Personality symptoms | −.14 | .21** | .08 | .12 | .19** | .00 | −.08 | .08 |

| Somatization symptoms | −.13 | .15* | .05 | .18* | .17* | .18* | .13 | .19** |

| Obsessive Compulsive symptoms | .03 | .01 | .07 | .04 | .00 | .02 | −.01 | .00 |

| Phobia symptoms | −.05 | .07 | −.04 | .07 | .05 | .05 | .02 | .06 |

| Traumatic Stress symptoms | −.11 | .15* | .10 | .14* | .04 | .12 | .02 | .16* |

| Paranoia symptoms | −.01 | −.05 | −.02 | .14* | −.06 | .02 | .02 | −.02 |

| Alcohol dependence symptoms | −.05 | .02 | −.06 | .06 | .10 | .03 | −.01 | .06 |

| Marijuana dependence symptoms | .11 | −.09 | −.12 | −.00 | −.03 | −.06 | −.11 | −.04 |

| Cocaine dependence symptoms | −.15* | .24** | .12 | .19** | .27*** | .01 | .04 | .09 |

| Opiate dependence symptoms | −.14* | .18** | .03 | .02 | .19** | .07 | .11 | .04 |

| Comorbid MH/SA | −.15* | .08 | .01 | .03 | .20** | .02 | .04 | .03 |

Note. N = 199–204

p < .05

p < .01

p < .001

Symptoms of paranoia were also associated with participation in support groups. Symptoms of substance dependence, especially dependence on cocaine and opiates, were closely linked to treatment participation. Symptoms of cocaine dependence were positively related to involvement in formal treatment programs, especially support groups and drug/alcohol treatment; opiate dependence was associated with formal treatment participation, especially drug/alcohol treatment. More generally, inmates in need who did not participate in any treatment were significantly less likely to have cocaine and opiate dependency symptoms. In contrast, symptoms of dependence on alcohol and marijuana were unrelated to participation in treatment and religious programs, and in fact, although not significant, symptoms of marijuana dependence was negatively correlated with participation in all programs.

Reasons for not participating in treatment while incarcerated

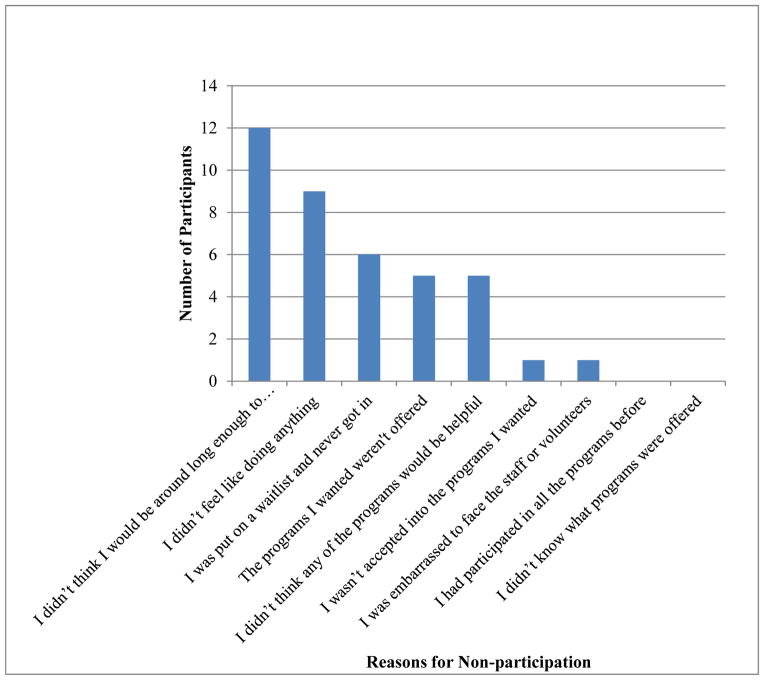

A total of 24 participants with a need for treatment (23 male and one female) answered questions regarding the reasons they did not participate in any of the formal or informal treatment options available to them during their period of incarceration (see Figure 2). The most common reason was the belief that he or she wouldn’t be incarcerated long enough to participate in treatment or programs (N = 12; 50%). Inmates in need who indicated they did not participate because they believed they wouldn’t be incarcerated long enough were, in fact, incarcerated about half the number of days (M = 111 days, SD = 50) relative to non-participants who did not endorse this reason (M = 221 days, SD = 138; t (22) = 2.59, p = .02). Even so, the average length of incarceration for this group was sufficiently long (about 3.5 months) to engage in some treatment and services. Other reasons for not participating in treatment and services were being put on a waitlist indefinitely (N = 6; 35%), not feeling like doing anything (N = 9; 38%), believing that none of the programs would be helpful (N = 5; 21%), and because the programs wanted were not offered (N = 5; 21%). Only one inmate endorsed that he or she was not accepted into the desired program(s) (4%) and one inmate endorsed being embarrassed to face staff or volunteers (4%). None of the inmates endorsed that they had participated in all of the programs before, or that they were unaware of the programs that were offered as reasons for not participating.

Figure 2. Jail Inmates’ Reasons for Non-Participation in Programs (N = 24).

Note: Categories are not mutually exclusive, as participants could report multiple reasons.

Differences in Reasons Given for Non-Participation in Treatment by Symptom Type

Were reasons for not participating associated with type of symptom, among the 24 inmates in need of treatment who did not participate? Given the small sample size and associated power limitations, these must be considered pilot results. We noted correlations below p < .10, which translates into an effect size of roughly r > .35 (with the exception of the item about waitlists), and excluded the four barriers with minimal variance. As shown in Table 2, “I didn’t think any of the programs would be helpful” was associated with less mental illness symptoms in general but more symptoms of alcohol dependence. “I didn’t feel like doing anything” was associated specifically with having opiate dependence symptoms. Inmates who believed they would not be around long enough to participate in programs were less likely to have symptoms of mania and paranoia. “The programs I wanted weren’t offered” was associated with symptoms of depression and somatic complaints, as well as fewer symptoms of substance dependence, specifically alcohol dependence. Those who endorsed “I was put on a waiting list and never got in” were also less likely to have phobia and alcohol dependence symptoms.

Table 2.

Correlations between Symptoms and Reasons given for not Participating in Any Treatment Options.

| I didn’t think any of the programs would be helpful | I didn’t feel like doing anything | I didn’t think I would be around long enough to participate in programs | The programs I wanted weren’t offered | I was put on a waiting list and never got in | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any mental health symptoms | −.42* | .25 | −.19 | .06 | −.06 |

| Depression symptoms | −.03 | .29 | −.01 | .48* | .19 |

| Anxiety symptoms | .00 | .30 | .05 | .34 | .06 |

| Mania symptoms | −.12 | .02 | −.44* | −.13 | .11 |

| Schizophrenia symptoms | −.34 | .32 | −.20 | .32 | .07 |

| Borderline Personality symptoms | −.06 | .34 | −.10 | .22 | .04 |

| Somatization symptoms | −.13 | −.25 | −.25 | .48* | −.16 |

| Obsessive Compulsive symptoms | −.23 | .01 | −.22 | .19 | .08 |

| Phobia symptoms | −.10 | .01 | .08 | −.05 | −.41 |

| Traumatic Stress symptoms | −.24 | .03 | −.19 | .16 | −.24 |

| Paranoia symptoms | −.24 | .07 | −.40+ | .28 | .10 |

| Any symptoms of Substance Dependence | .31 | .07 | .03 | −.41+ | −.13 |

| Alcohol dependence symptoms | .37+ | .10 | .06 | −.38+ | −.44+ |

| Marijuana dependence symptoms | −.09 | −.06 | −.25 | −.33 | −.03 |

| Cocaine dependence symptoms | .24 | −.06 | .01 | −.30 | −.20 |

| Opiate dependence symptoms | .32 | .41+ | .10 | .25 | .17 |

| Comorbid MH/SA | −.08 | .30 | −.13 | −.29 | −.24 |

Note. N = 23–24, except for “I was put on a waiting list and never got in” where N = 16–17.

p < .10

p < .05

Discussion

Why do some jail inmates in need of mental health and/or substance abuse treatment remain untreated when many common barriers to treatment found in the community at large (such as cost, lack of insurance coverage, and transportation difficulties) are not present? This study examined the characteristics of the “untreated” and their perceptions of the most common barriers to treatment seeking in a jail environment.

The Untreated: Young and Male

Slightly more than 18% of inmates in need were untreated, meaning they did not participate in any of the treatment options or religious programs available during incarceration. Individuals in the untreated group were far more likely to be male. Although not unexpected, as there is a good deal of research indicating that women in general are more likely than men to participate in treatment and services (Faust & Magaletta, 2010; Mackenzie, Gekoski, & Knox, 2006; Perlick & Manning, 2006), the high rates of female participation (96.6%) in the current study is striking given that – as is typical of local jails -- the site where this research was conducted is primarily a male facility, with treatment and services tailored toward male inmates. Yet, in this sample of inmates in need of services, the untreated were overwhelmingly male. The results suggest that the removal of logistic and practical barriers (e.g., cost, time, transportation) may greatly increase the likelihood of females in need obtaining treatment, whereas other person-related barriers remain for males in need. Research in the help-seeking literature suggests that men underutilize mental health services due to factors such as self-reliance, tendency to minimize problems, distrust of caregivers and need for privacy (Mansfield, Addis, & Courtenay, 2005; Dearing & Twaragowski, 2010) – each of which is apt to be especially salient in a jail or prison context. Thus, enhanced efforts to actively screen incoming inmates for mental health and substance use problems are needed, in place of treatment delivery systems that rely heavily on self-referral. Moreover, efforts to engage male inmates in treatment may be more effective to the degree that outreach is sensitive to these personal barriers.

In this jail-based study, untreated inmates in need were younger than those who participated in treatment. Research on the implications of age for help-seeking in community settings is mixed (Dearing & Twaragowski, 2010). However, in a study of requests for psychiatric services among federal prison inmates (Diamond, Magaletta, Harzke & Baxter, 2008), male non-requestors were younger than male requestors (with an analogous non-significant trend among female inmates). Thus, in addition to expanded screening, clinicians working in correctional settings may wish to consider developing special programs targeting younger inmates or special outreach efforts aimed at younger individuals in need. To further inform such efforts, future research utilizing qualitative methods could explore reasons why younger inmates do not engage in treatment. For example, it may be that young people entering the correctional context are especially concerned with being perceived as weak, and they may worry that seeking treatment may be seen as a sign of weakness.

Much previous research has shown racial/ethnic disparities in treatment utilization such that ethnic minorities seek and utilize treatment less often than majority whites (Alegria, Canino, Rios, Vera, Calderon, Rusch, et al., 2002; Alvidrez, 1999; Diala, Muntaner, Walrath, Nickerson, LaVeist, & Leaf, 2000), however as described and discussed in greater detail in Youman, et al., (2010), no such differences in treatment participation were observed in this sample of jail inmates in need of treatment or services. In fact, Hispanic inmates in need of treatment participated in drug and alcohol treatment at higher rates than their peers.

Treatment participation varied little in terms of specific types of mental health symptoms. Symptoms of substance dependence (especially on dependence on cocaine and opiates) distinguished between those in need who did and did not participate in treatment. Inmates reporting pre-incarceration symptoms of cocaine and opiate dependence were more likely to request and engage in treatment and services, relative to their peers. A link between drug use and treatment seeking was also observed in Diamond, et al.’s (2008) study of federal prison inmates. As discussed in greater detail below, differential treatment availability may be one reason treatment participation varied as a function of substance dependence symptoms but not psychological problems. As in most local jail settings, few mental health services were available for inmates suffering from psychological distress, whereas more options were available to those with substance abuse concerns.

Reasons for Non-participation

Clearly there are treatment needs not being met for some inmates with mental health and substance dependence problems. This study is unique in exploring the reasons why incarcerated offenders in need of intervention do not participate in the treatment options available to them.

First, it is apparent the facility in which the research was conducted had done a creditable job in providing information about the various services available to inmates. None of the inmates in need who did not participate in programs or services indicated that they were unaware of the treatment options available and none stated that they had already participated in all of the services provided. Reasons endorsed by the untreated were both institution-related and person-related in nature suggesting that the untreated fall into two categories: those who are reluctant to participate in treatment and those who are willing and motivated but unable to participate in treatment for a variety of reasons. Inmates reluctant to participate are more likely to cite person-related barriers, while those unable to participate in treatment are more likely to cite institution-related barriers.

Person-related Barriers: Those Reluctant to Participate in Treatment

Those reluctant to participate in treatment include inmates who were concerned about the stigma of treatment and those who had a lack of motivation for treatment. “Not feeling like doing anything” was most likely to be cited as a barrier by those inmates with opiate dependence problems. Increasing motivation and underscoring the effectiveness of treatment may help to reduce the barriers to treatment for those untreated inmates. For example, practitioners may find it useful to employ brief, cost-effective motivational interviewing procedures (Miller & Rollnick, 2002) with inmates identified as being in need by screening measures.

Institution-related Barriers: Those Unable to Participate in Treatment

In contrast to those who were reluctant to participate in treatment, there were untreated inmates who cited reasons indicating they were unable to participate in treatment. This suggests that if services were more available or better tailored to specific treatment needs, some offenders in need would be likely to participate. In particular, inmates high in depression and somatic symptoms were more likely to indicate they did not participate because the programs they wanted were not offered. And indeed, the range of forensic services was limited. Increasing the number of programs targeted to meet specific mental health needs may help increase treatment participation among inmates in need. Here, too, routine screening followed up by assignment to short-term evidence based treatments (e.g., manualized cognitive-behavioral interventions) may be especially helpful in short-term jail settings.

Notably, inmates with substance dependence problems, especially alcohol problems, were less likely to indicate that the programs they wanted weren’t offered, and inmates with alcohol dependence symptoms were less likely to indicate they were waitlisted and thus could not get into treatment. Like many large jails, the setting in which this study was conducted had an active 12-step program staffed by volunteers from the community, in addition to a small intensive addictions program. In contrast, few programs specifically addressed mental health concerns. Thus, there was a substantial gap between need and available treatment options in the domain of mental health, a gap evident across jails, nationally (Taxman, et al., 2007).

Time-related Barriers: Perceptions of Limited Time to Engage in Treatment

The most common reason given for not participating in any treatment was the belief that one would not be around long enough to participate in programs. Follow up analyses indicated there was some basis for this perception. Inmates in need who endorsed this reason did, in fact, have shorter periods of incarceration than those inmates who did not endorse it. But on average, they were incarcerated for a sufficient period of time (111 days) to make use of treatment options. Providing more short-term treatment options or more frequent scheduling of groups and services, as well as emphasizing the availability of current programs and services (especially for those inmates expecting shorter terms of incarceration) could help increase treatment participation.

Study limitations and directions for future research

Several limitations of this study should be noted. The sample was limited to felony inmates of one jail (adult detention center), and thus excluded inmates charged with or convicted of solely misdemeanor offenses. Inmates who participated in religious services only were classified as having engaged in treatment and services and were not therefore administered questions regarding barriers to program involvement. Due to the small number of inmates in the untreated group (24 participants), analysis regarding barriers to treatment was limited. It remains unclear whether the barriers for treatment for men and women are different or whether reasons for not participating differ across racial groups. In addition, the reasons provided to the untreated group of inmates were limited, and therefore some barriers remain unaddressed. Finally, the data gathered did not distinguish between inmates who participated in treatment services on a consistent and ongoing basis from those who attended a single session. There is evidence that treatment completion and compliance among this population is also quite low. This is an important direction for future research.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by Grant #R01 DA14694 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse to June P. Tangney. We are grateful for the assistance of inmates who participated in our study.

Footnotes

More detailed findings are available from the corresponding author upon request.

Contributor Information

Candace Reinsmith Meyer, Email: drcmeyer@gmail.com, Clinical Psychologist, Private Practice, 491-B Carlisle Drive, Herndon, VA 20170

June P. Tangney, Email: jtangney@gmu.edu, Professor, George Mason University, Department of Psychology, George Mason University, 4400 University Dr., Fairfax VA 22030

Jeffrey Stuewig, Email: jstuewig@gmu.edu, Research Associate Professor, George Mason University, Department of Psychology, George Mason University, 4400 University Dr., Fairfax VA 22030

Kelly Moore, Email: kmoorei@gmu.edu, Doctoral Student in Clinical Psychology, George Mason University, Department of Psychology, George Mason University, 4400 University Dr., Fairfax VA 22030

References

- Alegria M, Canino G, Rios RL, Vera M, Calderon J, Rusch D, et al. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alvidrez J. Ethnic variations in mental health attitudes and service use among low-income African American, Latina, and European American young women. Community Mental Health Journal. 1999;35:515–530. doi: 10.1023/a:1018759201290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4. Washington, DC: Author; 2000. text revision. [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Lang MA, O’Connor LA. Self-reported psychiatric treatment needs among felony drug offenders. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice. 2003;19:9–29. [Google Scholar]

- Belenko S, Peugh J. Estimating drug treatment needs among state prison inmates. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2005;77:269–281. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bermúdez JM, Kirkpatrick DR, Hecker L, Torres-Robles C. Describing Latinos families and their help-seeking attitudes: Challenging the family therapy literature. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. 2010;32:155–172. [Google Scholar]

- Dearing RL, Twaragowski C. The social psychology of help seeking. In: Maddux JE, Tangney JP, editors. Social Psychological Foundations of Clinical Psychology. New York: Guilford; 2010. pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- Diala CC, Muntaner C, Walrath C, Nickerson KJ, LaVeist TA, Leaf PJ. Racial differences in attitudes toward seeking professional mental health care and in the use of services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2000;70:455–464. doi: 10.1037/h0087736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diamond PM, Magaletta PR, Harzke AJ, Baxter J. Who requests psychological services upon admission to prison? Psychological Services. 2008;5:97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Drapalski A, Youman K, Stuewig J, Tangney JP. Gender differences in jail inmates’ symptoms of mental illness, treatment history and treatment seeking. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 2009;19:193–206. doi: 10.1002/cbm.733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Khoury M, Dutton M, Goodman LA, Engel L, Belamaric RJ, Murphy M. Ethnic differences in battered women’s formal help-seeking strategies: A focus on health, mental health, and spirituality. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 2004;10:383–393. doi: 10.1037/1099-9809.10.4.383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farberman RK. Public attitudes about psychologists and mental health care: Research to guide the American Psychological Association public education campaign. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 1997;28:128–136. [Google Scholar]

- Faust E, Magaletta PR. Factors predicting levels of female inmates’ use of psychological services. Psychological Services. 2010;7:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- James DJ, Glaze LE. Mental health problems of prison and jail inmates. Washington, DC: Bureau of Justice Statistics; 2006. NCJ213600. [Google Scholar]

- Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, Gross BH. Mentally ill persons in the criminal justice system: Some perspectives. Psychiatric Quarterly. 2004;75:107–126. doi: 10.1023/b:psaq.0000019753.63627.2c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackenzie CS, Gekoski WL, Knox VJ. Age, gender, and the underutilization of mental health services: The influence of help-seeking attitudes. Aging & Mental Health. 2006;10:574–582. doi: 10.1080/13607860600641200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magaletta PR, Diamond PM, Faust E, Daggett DM, Camp SD. Estimating the mental illness component of service needs in corrections: Results from the Mental Health Prevalence Project. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2009;36:229–244. [Google Scholar]

- Mansfield AK, Addis ME, Courtenay W. Measurement of men’s help-seeking: Development and evaluation of the Barriers to Help Seeking Scale. Psychology of Men & Masculinity. 2005;6:95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Matthews AK, Corrigan PW, Smith BM, Aranda F. A qualitative exploration of African American’s attitudes toward mental illness and mental illness treatment seeking. Rehabilitation Education. 2006;20:253–268. [Google Scholar]

- Miller WR, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing: Preparing people for change. 2. New York: The Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell J, Latchford G. Prisoner perspectives on mental health problems and help-seeking. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry & Psychology. 2010;21:773–788. [Google Scholar]

- Morey LC. Personality Assessment Inventory – Professional Manual. Florida, USA: Psychological Assessment Resources, Inc; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan RD, Rozycki AT, Wilson S. Inmate perceptions of mental health services. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice. 2004;35:389–396. [Google Scholar]

- Perlick DA, Manning LN. Overcoming stigma and barriers to mental health treatment. In: Grant JE, Potenza MN, editors. Textbook of men’s mental health. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc; 2006. pp. 389–417. [Google Scholar]

- Peters RH, Greenbaum PE, Edens JF, Carter CR, Ortiz MM. Prevalence of DSM-IV substance abuse and dependence disorders among prison inmates. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse. 1998;24:573–587. doi: 10.3109/00952999809019608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters RH, LeVasseur ME, Chandler RK. Correctional treatment for co-occurring disorders: Results of a national survey. Behavioral Sciences & the Law. 2004;22:563–584. doi: 10.1002/bsl.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saunders SM, Zygowicz KM, D’Angelo BR. Person-related and treatment-related barriers to alcohol treatment. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2006;30:261–270. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson DD, Knight K. TCU data collection forms for correctional residential treatment. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University, Institute of Behavioral Research; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Steadman HJ, Veysey BM. National Institute of Justice Research in Brief, NCJ 162207. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs; 1997. Providing services for jail inmates with mental disorders. Retrieved from https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles/162207.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Tangney JP, Mashek D, Stuewig J. Working at the social-clinical-community-criminology interface: The George Mason University Inmate Study. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology. 2007;26:1–21. doi: 10.1521/jscp.2007.26.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taxman FS, Perdoni ML, Harrison LD. Drug treatment services for adult offenders: The state of the state. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment. 2007;32:239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jsat.2006.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Youman K, Drapalski A, Stuewig J, Bagley K, Tangney JP. Race differences in psychopathology and disparities in treatment seeking: Community and jail-based treatment seeking patterns. Psychological Services. 2010;7:11–26. doi: 10.1037/a0017864. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]