Abstract

Studies in human populations consistently demonstrate an interaction between nicotine and ethanol use, each drug influencing the use of the other. Here we present data and review evidence from animal studies that nicotine influences operant self-administration of ethanol. The operant reinforcement paradigm has proven to be a behaviorally relevant and quantitative model for studying ethanol-seeking behavior. Exposure to nicotine can modify the reinforcing properties of ethanol during different phases of ethanol self-administration, including acquisition, maintenance, and reinstatement. Our data suggest that non-daily intermittent nicotine exposure can trigger a long-lasting increase in ethanol self-administration. The biological basis for interactions between nicotine and ethanol is not well understood but may involve the stress hormone systems and adaptations in the mesolimbic dopamine system. Future studies that combine operant self-administration with techniques for monitoring or manipulating in vivo neurophysiology may provide new insights into the neuronal mechanisms that link nicotine and alcohol use.

Keywords: Nicotine, Ethanol, Dopamine, Operant reinforcement, Stress hormone

1. Introduction

Nicotine and alcohol (ethanol) are the two most commonly abused drugs worldwide and account for over 9 million deaths per year combined [1,2]. The positive correlations between nicotine and alcohol use are well documented [3–7]. In young adults, both regular smokers and non-regular (non-dependent) smokers are more vulnerable to binge drinking than non-smokers [5,8,9]. Nicotine may also enhance some of the subjective rewarding effects of alcohol—and vice versa [10–13]. Nicotine use can also influence alcohol drinking in a more long-term context. Early age tobacco use increases the risk of developing alcohol use disorders later in life [14–17]. Therefore, studies in human populations demonstrate a potent and multidimensional interaction between nicotine and alcohol use.

Consistent with the human literature, animal studies have shown that exposure to nicotine can increase subsequent ethanol self-administration [18–22]. However, the results have been mixed, with studies also reporting that nicotine has no effect or even decreases ethanol self-administration [23–25]. We will review the evidence that nicotine increases ethanol self-administration by highlighting studies that use operant reinforcement to study the interaction. The concept of reinforcement has guided our current theories of drug abuse and addiction and represents a quantitative approach for studying motivated alcohol-seeking behavior [26,27]. Although alcohol exposure clearly influences aspects of nicotine reward and cigarette smoking behavior [10,28–30], few animal studies have explored this interaction using an operant self-administration model. Therefore, alcohol’s influence over nicotine use will not be discussed in detail.

Nicotine and ethanol act upon diverse molecular targets throughout the central nervous system, but these drugs also share common pharmacological actions [31,32]. It is hypothesized that common modulation of the mesolimbic dopamine (DA) and brain stress hormone systems contributes to the interactions between nicotine and ethanol [33–35]. The mesolimbic DA system is a key target of drugs of abuse, and dysregulation of the DA system is implicated in the development of addiction [36,37]. Blunted DA transmission has been associated with increased susceptibility to drug and alcohol abuse [38,39]. Consistent with these results, our recent work shows that pre-exposure to nicotine increases ethanol self-administration and decreases the responsiveness of the DA system to ethanol [22]. These interactions involve and may arise via activation of the stress hormone systems and subsequent changes in inhibitory neurotransmission [22].

2. Operant reinforcement as a model of ethanol self-administration

Originating from the pioneering work of Thorndike [40], the concept of operant reinforcement dates back to the early 20th century. A reinforcer can be defined as any consequence (or event) that increases the probability of an organism repeating a specific (operant) behavior. In rodents, typical operant behavior includes lever-press and nose-poke responses, which can be measured and analyzed experimentally. Therefore, operant reinforcement, by definition, is a quantitative approach for studying behavior.

Early animal studies of ethanol reinforcement in the 1950’s and 60’s have evolved to examine various components of behavior associated with ethanol self-administration [41–45]. The following is a brief description of different aspects of ethanol self-administration that have been studied using the operant reinforcement paradigm, which we will expand upon in later sections. The development of ethanol reinforcement generally involves two phases of behavior that can be examined experimentally: the acquisition phase and the maintenance phase [46]. The acquisition phase refers to the initial exposure periods, during which time patterns of ethanol self-administration and preference are not yet fully established. During acquisition, ethanol is often introduced (or faded) into a sweetened drinking solution gradually over days to minimize ethanol’s aversive stimulus properties [47]. Acquisition of ethanol self-administration can also be achieved using nonfading procedures that keep the ethanol content of the drinking solution constant from day to day [48,49]. In either case, there is a brief period at the beginning of training that requires the animal to adjust to the taste and sensory cues of the ethanol solution. After this adjustment period, the levels of ethanol intake and preference tend to become more consistent, which has been referred to as the maintenance phase of ethanol self-administration. After ethanol self-administration is established, other dimensions of human alcohol use can also be modeled. For example, relapse has been modeled in rodents using withdrawal and reinstatement procedures [20,50].

In addition to the oral route of reinforcement, motivation to consume ethanol has also been measured using other approaches, including intragastric, intravenous, and intracranial self-administration [51–54]. These alternative approaches lack some of the face validity of oral self-administration but offer other experimental advantages. For example, the pharmacological and behavioral effects of ethanol can be studied apart from the taste and odor cues of ethanol, which can be aversive; these approaches also provide a more consistent ethanol dose across test subjects. Intracranial self-administration has proven useful for identifying specific brain regions involved ethanol reinforcement. In summary, operant self-administration is a valuable tool for examining different quantitative aspects of ethanol-seeking behavior under controlled laboratory conditions [26,55].

3. Nicotine exposure influences operant ethanol self-administration

Making use of the operant self-administration approach, several animal studies have examined the effect of nicotine treatment on the development of ethanol reinforcement, including during periods of acquisition, maintenance, and reinstatement. The results have not always been consistent, but the weight of evidence suggests that exposure to nicotine can escalate subsequent ethanol self-administration depending on the experimental conditions.

3.1. Nicotine and the acquisition of ethanol self-administration

The acquisition period of drug and alcohol seeking provides a critical window for analysis of the basic mechanisms that could drive more complex behaviors associated with chronic drug use. However, the effect of nicotine exposure on the acquisition of ethanol reinforcement has not been studied extensively [22,56]. In an early study, nicotine was administered daily by minipump beginning as a pretreatment prior to ethanol exposure and continuing for weeks during ongoing ethanol self-administration [56]. Rats treated with nicotine showed increased operant responding for ethanol (+10% sucrose) compared to the control, but the amount of ethanol actually consumed (g/kg) was not significantly different between the groups. The reason for this discrepancy is unclear but could be related to subtle changes in behavior arising from the chronically implanted minipump. On the other hand, the nicotine treatment also appeared to increase sucrose preference prior to ethanol self-administration, which limits the interpretation of these findings because the ethanol solution contained a mixture of sucrose.

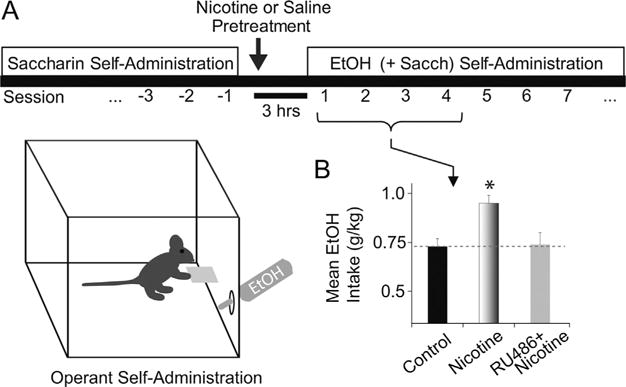

We recently showed that nicotine pretreatment selectively increases operant ethanol self-administration during the acquisition of drinking behavior in Long-Evans rats [22]. After establishing stable responses to saccharin (0.125%, w/v), the rats were pretreated with nicotine (0.4 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline 3 h prior to the first ethanol self-administration session (Fig. 1A). The nicotine pretreatment caused a significant increase in ethanol (+saccharin) intake that lasted for approximately 6 days compared to the saline control (Fig. 1B). Importantly, the nicotine pretreatment did not alter saccharin intake, suggesting that nicotine did not cause a general increase in locomotor or hedonic behavior but was specific to ethanol under these conditions.

Fig. 1.

A single nicotine pretreatment increases the acquisition of operant ethanol self-administration. (A) Schematic illustration of the self-administration procedure used previously by Doyon et al. [22]. Rats were trained to respond for saccharin (0.125%, w/v) during daily 45-min operant sessions. After establishing baseline saccharin preference, we injected the rats with either saline or nicotine (0.4 mg/kg, i.p.) 3 h before an initial ethanol self-administration session. The ethanol solutions consisted of 2–8% ethanol (v/v) faded into the solution over 8 days of training. (B) Compared to the saline control, nicotine pretreatment significantly increased mean ethanol intake during first 4–6 self-administration sessions. *Significantly different from the saline control by ANOVA with repeated measures, n = 15–23 rats per group. Pretreatment with RU486 (40 mg/kg, i.p.) prior to nicotine prevented the increase in ethanol self-administration mediated by nicotine pretreatment (n = 12 rats).

Adapted from Doyon et al. (2013, Neuron 79:530–40) [22] and re-published with permission from Cell Press.

A few caveats should be considered. The discrepancies between the two studies above may arise from different nicotine pretreatment schedules (acute vs. continuous exposure) and different routes of administration (intraperitoneal vs. subcutaneous). In addition, we recommend screening the animals for their saccharin (or sucrose) preference prior to testing. Preferences for sweeteners can vary widely between individual rodents, and it is important to use cohorts that have a comparable distribution of preferences prior to the transition to ethanol for the most consistent results. Alternatively, future experiments should also examine the effect of nicotine on self-administration of an unsweetened ethanol solution, as the sweetener is a potential confound. Our unpublished data indicate that repeated nicotine pretreatment (daily i.p. injections over 14 days) can increase subsequent ethanol self-administration with and without the addition of saccharin (a non-nutritive sweetener). More work is needed to understand how these different variables influence the development of nicotine-induced ethanol self-administration.

A novel finding from the study by Doyon et al. is that the effect of nicotine on acquisition of ethanol self-administration was blocked by pretreatment with RU486, a stress hormone receptor antagonist (Fig. 1B). Activation of stress hormone systems has been associated with increased ethanol self-administration [57,58]. Stress hormone systems participate in the pharmacological effects of nicotine [59,60], but there is little information on whether neuroendocrine signaling induced by nicotine contributes to interactions with ethanol. This new finding suggests that acute nicotine administration activates the glucocorticoid stress hormone system to increase ethanol self-administration [22]. Nicotine can produce either anxiolytic or anxiogenic effects depending on the dose [61]; therefore, the influence of nicotine over early ethanol drinking could be due in part to nicotine’s anxiogenic properties.

3.2. Nicotine and the maintenance of ethanol self-administration

In terms of operant ethanol self-administration that is already established or maintained, several studies have examined ethanol intake in response to nicotine exposure [20,21,24,25,62,63]. In these studies, the nicotine was administered to rats by repeated subcutaneous injections prior to daily self-administration sessions. Overall, the evidence indicates that nicotine treatment can increase operant ethanol self-administration. For example, three different labs have shown that moderate to high doses of nicotine (0.2–0.8 mg/kg) increase operant responding and ethanol intake in three different rat strains [20,21,62,63]. However, a few studies have also reported that repeated nicotine exposure decreases ethanol intake or has no effect on it [24,25]. If there were methodological differences between studies, it is not apparent which one (or combination) contributed to these results. The studies employed comparable rat strains and nicotine doses, and the nicotine pretreatment was administered at a similar time (15–30 min) prior to the ethanol self-administration session. One possibility is that increases in ethanol intake after nicotine pretreatment might require longer self-administration sessions to observe the increase [64]. Most studies that report increased ethanol intake used 60-min self-administration sessions, whereas the studies by Samson and colleagues used 30-min sessions. In addition, differences in the schedule of reinforcement (fixed-ratio vs. response requirement) could also factor into these results. In summary, under certain conditions, repeated daily nicotine pretreatment can increase ethanol intake during the maintenance phases of self-administration, but more work is needed to understand the basis for some discrepancies in the literature.

3.3. Intermittent nicotine and the maintenance of ethanol self-administration

Non-daily, intermittent cigarette users represent a significant segment of the smoking population [65–67]. Although it is often observed in young adults and in individuals attempting to quit smoking, intermittent cigarette use has become the norm for a substantial proportion of smokers [68–71]. Particularly in young adults, non-daily cigarette use is a risk factor for alcohol abuse and binge-patterns of drinking [5,8,9]. However, there is very little information from animal studies regarding the interaction between intermittent nicotine exposure and ethanol self-administration. One study followed rats exposed to nicotine during adolescence and measured their daily ethanol consumption as adults in response to nicotine re-exposure [72]. The results showed that re-exposure to nicotine in adulthood increased (non-operant) ethanol self-administration, compared to the control group that received nicotine for the first time.

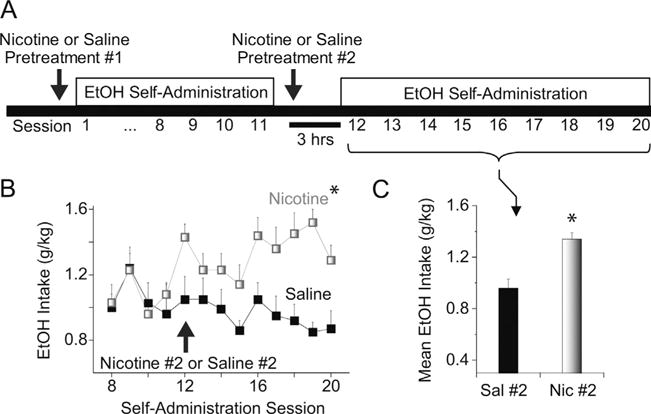

Extending the results shown in Fig. 1, we tested the hypothesis that re-exposure to nicotine increases operant ethanol self-administration. We maintained a subset of rats from the nicotine pretreatment group on a schedule of ethanol self-administration (Fig. 2A). The effect of nicotine pretreatment on ethanol self-administration, shown in Fig. 1, subsequently waned over several days and the two groups became indistinguishable (as indicated by intakes during the first 4 self-administration sessions shown in Fig. 2B). We subsequently re-exposed the rats to a second nicotine treatment, which was administered 3 h prior the next ethanol self-administration session. The second nicotine exposure potently increased ethanol self-administration on the day of the test and over the course of subsequent self-administration sessions as compared to the saline pretreatment control group (Fig. 2B). ANOVA indicated a significant between-group effect of time over the 9 days of drinking [group: F(1,15) = 24.28, p < 0.01]. During this 9-day period, the ethanol self-administration levels of individual rats fluctuated considerably from one day to the next.

Fig. 2.

Re-exposure to nicotine increases ethanol self-administration. (A) Schematic illustration of the paradigm used for nicotine treatment and ethanol self-administration. We followed a cohort of rats from Fig.1. These rats were maintained on operant self-administration of 8% ethanol (+0.125% saccharin) and then re-exposed to either nicotine or saline approximately two weeks later (Nicotine #2 or Saline #2). (B) For the rats initially exposed to nicotine (Nicotine #1), re-exposure to nicotine (3 h prior to self-administration, Nicotine #2) significantly increased subsequent ethanol intake over 9 drinking sessions (Sessions 12–20, lightly shaded squares). *Significantly different from the saline pretreatment control by ANOVA with repeated measures. (C) Mean ethanol intake over 9 self-administration sessions for nicotine and saline pretreatment groups.

*Significantly different by t-test, n = 7–10 rats per group.

We also examined the effect of acute nicotine pretreatment on a third group of rats with prior self-administration training (data not shown). In these subjects, a single nicotine exposure failed to increase ethanol intake significantly over time, consistent with previous studies showing that the stimulatory effect of the nicotine pretreatment requires more than one exposure to observe [20,21]. The reason for this lack of efficacy is unclear but could be related to the fact that the animals were no longer drug-naïve. The results suggest that different mechanisms govern the interactions between nicotine and ethanol during acquisition and maintenance phases of ethanol self-administration.

3.4. Nicotine and the reinstatement of ethanol self-administration

Relapse to alcohol use, even after prolonged periods of abstinence, remains a major problem in the treatment of alcohol use disorders [73]. Alcohol relapse is linked to different factors that can induce craving, including alcohol-related stimulus cues and exposure to stress [74,75]. Given the high prevalence of smoking among alcoholics, understanding how nicotine exposure influences alcohol relapse could significantly impact the treatment of alcohol use disorders.

Using reinstatement as a model for alcohol relapse, researchers have examined whether prior nicotine exposure promotes the reinstatement of ethanol-seeking behavior [20,76,77]. In studies of ethanol reinstatement, operant ethanol self-administration behavior is extinguished by making ethanol unavailable and the animals are later re-tested to determine if operant behavior is reinstated. Note that the ethanol reinstatement paradigm is typically a measure of operant responses (or ethanol-seeking behavior) and not ethanol consumption. In the studies by Le and colleagues, the rats were pretreated with nicotine during ethanol self-administration and then re-exposed to nicotine prior to the reinstatement session. Under these conditions, re-exposure to nicotine significantly increased ethanol-seeking (lever-press) behavior compared to control animals [20,76]. Other results demonstrate that even a single exposure to nicotine is sufficient to reinstate ethanol-seeking behavior [77]. In these studies, the nicotine pretreatment did not increase operant responses on the inactive lever or responses for water, ruling out a general effect on locomotor activity.

A study by Hauser et al. [77] is intriguing because the effect of nicotine pretreatment was time-sensitive. That is, the nicotine pretreatment only increased reinstatement behavior when administered 4 h in advance of the test and not when administered just prior to the test. Consistent with these results, as well as increased ethanol self-administration, our recent studies [22] also revealed multiple changes in ethanol’s pharmacological effects when nicotine was administered 3–15 h prior to testing. In most studies, nicotine pretreatment occurs within 30 min of the ethanol self-administration period, and during this time, some unwanted side effects from the stress of the nicotine injection could influence the animal’s normal behavior. Therefore, the time lag between the pretreatment and the drinking session should be considered carefully. Whether these time dependent effects of nicotine exposure on subsequent ethanol intake occur in humans has not been thoroughly explored. However, one study found that pretreatment with transdermal nicotine, beginning 3 h prior to ethanol drinking, enhanced the subjective positive effects associated with ethanol [12].

In addition, researchers have also examined the effect of nicotine pretreatment on subsequent ethanol intake (g/kg) during reinstatement of operant self-administration, but the results are inconclusive [78]. In this study, rats were exposed to nicotine (0.1–0.8 mg/kg, s.c.) for 5 days during a forced abstinence period prior to reinstatement (analogous to extinction). During reinstatement testing, the rats that were pretreated with nicotine showed increased ethanol intake compared to their own baseline measurements. However, there did not appear to be a statistical between-group difference when comparing the nicotine pretreatment groups with the controls that received saline, particularly during the first week of ethanol reinstatement. To extend this work, future studies could employ classic reinstatement models [20,50] to simultaneously measure ethanol intake in response to nicotine pretreatment.

4. Nicotine exposure influences the pharmacological effects of ethanol

Overall, the literature provides substantial evidence that nicotine exposure can modify operant ethanol self-administration under different models of ethanol-seeking behavior. However, the biological basis for the interaction between nicotine and ethanol remains elusive. Nicotine may influence alcohol use by modifying the function of neural substrates that are common to both drugs, including the mesolimbic DA system and the stress hormone systems associated with glucocorticoids and corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF) [33–35]. Recent studies have begun to reveal possible mechanisms and neural targets that are involved during this complex interaction. The nicotine and ethanol interaction has been shown to activate a set of interconnected brain structures involved in stress and reward processing, including the ventral tegmental area (VTA), nucleus accumbens, dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, and extended amygdala [63].

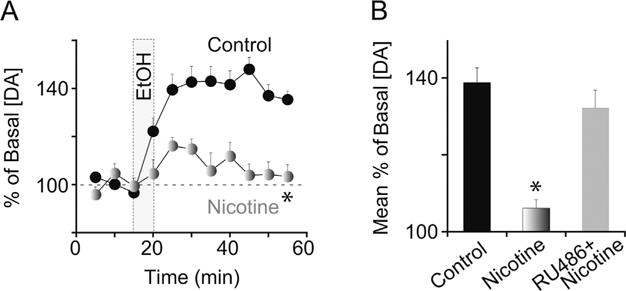

4.1. Nicotine pretreatment diminishes the sensitivity of the DA system to ethanol

Pretreatment with nicotine has been shown to decrease the responsiveness of the DA system to ethanol [22,79]. We have shown that pretreatment with nicotine (3–40 h prior to testing) decreases the amplitude and the time course of ethanol-induced DA signals in the VTA and the nucleus accumbens when compared to control animals pretreated with saline [22]. A key finding from this study is that pretreatment with RU486 (a glucocorticoid/progesterone receptor antagonist) prevented subsequent changes in ethanol-induced DA release (Fig. 3A and B). RU486 was effective when administered either by systemic injection or by local microinfusion into the VTA, indicating that stress hormone signaling in the VTA is partly required for nicotine to alter ethanol’s pharmacological effects on the DA system.

Fig. 3.

Nicotine pretreatment attenuates ethanol-induced DA release via glucocorticoid signaling. (A) Rats were pretreated with nicotine (0.4 mg/kg, i.p.) or saline 15 h prior to in vivo ethanol administration (1.5 g/kg, i.v.; shaded vertical bar). Changes in [DA] were measured in 5-min intervals using microdialysis with HPLC. *Significantly different from the control by ANOVA with repeated measures. (B) Pretreatment with RU486 (40 mg/kg, i.p.) prior to nicotine prevented the blunted DA response mediated by nicotine pretreatment. The saline control group includes subjects that received RU486 alone 15 h prior to ethanol. *Significantly different from the saline pretreatment control by ANOVA with repeated measures, n = 9–16 rats per group.

Adapted from Doyon et al. (2013, Neuron 79:530–40) [22] and re-published with permission from Cell Press.

4.2. Nicotine pretreatment enhances ethanol-induced GABA release onto DA neurons

To understand the cellular and synaptic basis for nicotine’s interaction with ethanol, we performed electrophysiological recordings from DA neurons identified in VTA brain slices [22]. DA neuron activity is strongly regulated by inhibitory (GABA) synaptic input and excitatory (glutamate) synaptic input [80]. Therefore, we hypothesized that nicotine pretreatment (followed by ethanol) disrupted the balance between the inhibitory and excitatory synaptic inputs that regulate DA neurons and their responses to ethanol.

To test this hypothesis, we measured GABAergic and glutamatergic synaptic transmission onto DA neurons in response to ethanol [22]. Acute nicotine pretreatment did not significantly alter ethanol-induced glutamatergic synaptic transmission onto DA neurons compared to the control. However, compared to the control group, pretreatment with nicotine potentiated ethanol-induced GABA release onto DA neurons almost 3 fold, as indicated by an increase in spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic currents (sIPSCs) on DA neurons and by a decrease in the paired-pulse ratio of evoked IPSCs. Moreover, the increase in GABA release was mediated by stress hormone signals, as RU486 (a glucocorticoid/progesterone receptor antagonist) pretreatment prevented nicotine from increasing ethanol-induced GABA release.

In summary, these results provide evidence that the combination of nicotine pretreatment and subsequent ethanol exposure can enhance GABA release onto DA neurons, thereby decreasing the responsiveness of the DA system to ethanol. A role for GABA signaling in the motivation to consume ethanol is supported by studies showing that local inhibition of GABA signaling within the DA system decreases ethanol self-administration [81,82]. The lasting consequences of acute nicotine exposure on ethanol self-administration and ethanol-induced DA signaling could be mediated by nicotine’s activation of the stress hormone system. However, the cellular and system-level mechanisms through which nicotine and stress hormones could influence GABA/DA function are poorly understood.

4.3. Stress hormones, the DA system, and ethanol self-administration

To determine the basis for nicotine and ethanol interactions, future studies should investigate how stress hormone signals converge on the DA system to influence drug-seeking behavior. The hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis and the brain stress systems associated with glucocorticoids and CRF are critically involved in homeostasis and the physiological responses to stress. It is well documented that drugs of abuse, including nicotine and alcohol, activate the stress systems [83]. Chronic alcohol use is linked to long-term alterations in stress hormone signaling, including blunted responses to stress within the HPA axis [57,74,84,85].

Numerous studies have demonstrated a functional connection between the stress hormone systems and the DA circuits that enable motivated behavior. Rodents will learn to self-administer biologically relevant doses of glucocorticoids, indicating a role for glucocorticoids in reinforcement [86]. Glucocorticoid and CRF receptors in the mesolimbic system regulate DA signaling and different forms of motivated behavior, including reward and stress related behavior [22,87–90]. Evidence suggests that increased ethanol self-administration in response to nicotine involves glucocorticoid signaling in the DA system [22], but this hypothesis has not been directly tested. Local administration of glucocorticoids into the DA target regions has been shown to increase ethanol intake [91]. What remains unknown is the effect of local infusions of glucocorticoid antagonists into the VTA or the nucleus accumbens on nicotine-induced ethanol self-administration, which would help to resolve this question.

The nicotine-ethanol interaction may also involve CRF signaling in the VTA and in the extended amygdala structures. A recent study provides evidence that increased CRF signaling is associated with chronic nicotine exposure and withdrawal [92]. The results also suggested that CRF signaling mediates alterations in GABAergic transmission onto DA neurons after nicotine withdrawal. CRF receptors within the central amygdala mediate important pharmacological effects of ethanol on GABA transmission [93,94], and alterations in CRF signaling could contribute to excessive ethanol use and ethanol withdrawal [58,95,96]. CRF neurons in the central amygdala and in other extrahypothalamic regions can potentially modulate ethanol-induced DA signaling because CRF neurons project directly to the VTA DA centers [97,98]. In support, recent studies show that inhibition of CRF receptors in the VTA reduces ethanol self-administration in both rats and mice [99]. In summary, the hypothesis that nicotine could influence ethanol self-administration via glucocorticoid or CRF activity within the DA systems is intriguing but requires direct experimentation for confirmation, which is currently lacking.

5. Conclusions and future directions

Consistent with the human literature, most operant self-administration studies in rodents provide evidence that nicotine can increase subsequent ethanol intake. The evidence arises from studies using different reinforcement paradigms that model distinct stages in the development of ethanol-seeking behavior, including studies of acquisition, maintenance, and reinstatement. In human populations, ad libitum access to natural and drug-based rewards is not the norm, and a certain amount of effort or expense is required to procure the reward. Therefore, operant reinforcement has obvious face validity because it measures an animal’s willingness to work for rewards, such as ethanol. However, future studies should continue to develop behavioral models that more closely mimic human nicotine and alcohol usage. For example, modeling non-daily, intermittent nicotine use is a promising new direction to determine the effect of nicotine on ethanol self-administration. Additional studies are also needed to understand the basis for discrepancies in the effects of nicotine on ethanol intake. Several factors may influence this interaction and should be carefully considered, including the timing of nicotine exposure, the length of the self-administration session, and the schedule of reinforcement.

Nicotine and ethanol have complex pharmacological profiles and act upon targets throughout the nervous system. Therefore, it is likely that multiple mechanisms and different brain regions give rise to the reinforcing effects of the nicotine and ethanol combination, as recent studies suggest [63]. Repeated exposure to nicotine will induce neuroadaptations independent of those from ethanol (and vice versa), which could obscure the fundamental processes involved in the interaction. The acquisition period is a useful time frame to study potential mechanisms because the animal is in a drug-naïve state. On the other hand, different mechanisms may emerge after long-term drug exposures that are better measured with chronic models of self-administration. Recent evidence that nicotine engages the stress hormone systems to influence ethanol self-administration and DA signaling could have implications in the broader field of stress and ethanol interactions. It will be important to investigate whether similar mechanisms participate in the effect of nicotine on other phases of ethanol-seeking behavior, particularly during withdrawal and reinstatement.

In conclusion, a challenge facing the field is to link nicotine’s actions with specific cellular, circuit, and system level events that influence ethanol’s behavioral and pharmacological effects. When combined with operant self-administration, in vivo techniques for measuring or manipulating neural transmission, such as in vivo electrophysiology and electrochemistry, as well as behavioral optogenetics, could provide new types of information.

Acknowledgments

The authors and this work are supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health, NIDA DA09411 and NINDS NS21229.

References

- 1.WHO. Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiFranza JR, Guerrera MP. Alcoholism and smoking. J Stud Alcohol. 1990;51(2):130–135. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1990.51.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller NS, Gold MS. Comorbid cigarette and alcohol addiction epidemiology and treatment. J Addict Dis. 1998;17(1):55–66. doi: 10.1300/J069v17n01_06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Weitzman ER, Chen YY. The co-occurrence of smoking and drinking among young adults in college: national survey results from the United States. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;80(3):377–386. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barrett SP, Tichauer M, Leyton M, Pihl RO. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration in non-dependent male smokers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81(2):197–204. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dani JA, Harris RA. Nicotine addiction and comorbidity with alcohol abuse and mental illness. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1465–1470. doi: 10.1038/nn1580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harrison EL, Desai RA, McKee SA. Nondaily smoking and alcohol use, hazardous drinking, and alcohol diagnoses among young adults: findings from the NESARC. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2008;32(12):2081–2087. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00796.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell ML, Bozec LJ, McGrath D, Barrett SP. Alcohol and tobacco co-use in nondaily smokers: an inevitable phenomenon? Drug Alcohol Rev. 2012;31(4):447–450. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2011.00328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Glautier S, Clements K, White JA, Taylor C, Stolerman IP. Alcohol and the reward value of cigarette smoking. Behav Pharmacol. 2015;197(2):144–154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose JE, Brauer LH, Behm FM, Cramblett M, Calkins K, Lawhon D. Psychopharmacological interactions between nicotine and ethanol. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6(1):133–144. doi: 10.1080/14622200310001656957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kouri EM, McCarthy EM, Faust AH, Lukas SE. Pretreatment with transdermal nicotine enhances some of ethanol’s acute effects in men. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75(1):55–65. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.King AC, Epstein AM. Alcohol dose-dependent increases in smoking urge in light smokers. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2005;29(4):547–552. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000158839.65251.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grant BF. Age at smoking onset and its association with alcohol consumption and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. J Subst Abus. 1998;10(1):59–73. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chen X, Unger PJB, Palmer MD, Weiner CA, Wong Johnson MM, et al. Prior cigarette smoking initiation predicting current alcohol use evidence for a gateway drug effect among California adolescents from eleven ethnic groups. Addict Behav. 2002;27(5):799–817. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4603(01)00211-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jensen MK, Sorensen TI, Andersen AT, Thorsen T, Tolstrup JS, Godtfredsen NS, et al. A prospective study of the association between smoking and later alcohol drinking in the general population. Addiction. 2003;98(3):355–363. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.2003.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Riala K, Hakko H, Isohanni M, Jarvelin MR, Rasanen P. Teenage smoking and substance use as predictors of severe alcohol problems in late adolescence and in young adulthood. J Adolesc Health. 2004;35(3):245–254. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blomqvist O, Ericson M, Johnson DH, Engel JA, Soderpalm B. Voluntary ethanol intake in the rat: effects of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor blockade or subchronic nicotine treatment. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;314(3):257–267. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(96)00583-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Smith BR, Horan JT, Gaskin S, Amit Z. Exposure to nicotine enhances acquisition of ethanol drinking by laboratory rats in a limited access paradigm. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142(4):408–412. doi: 10.1007/s002130050906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Le AD, Wang SA, Juzytsch Harding W. Nicotine increases alcohol self-administration and reinstates alcohol seeking in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;168(1–2):216–221. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1330-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bito-Onon JJ, Simms JA, Chatterjee S, Holgate J, Bartlett SE. Varenicline, a partial agonist at neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, reduces nicotine-induced increases in 20% ethanol operant self-administration in Sprague-Dawley rats. Addict Biol. 2011;16(3):440–449. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2010.00309.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Doyon WM, Dong Y, Ostroumov A, Thomas AM, Zhang TA, Dani JA. Nicotine decreases ethanol-induced dopamine signaling and increases self-administration via stress hormones. Neuron. 2013;79(3):530–540. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2013.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dyr W, Koros E, Bienkowski P, Kostowski W. Involvement of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the regulation of alcohol drinking in Wistar rats. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34(1):43–47. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.1.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nadal R, Samson HH. Operant ethanol self-administration after nicotine treatment and withdrawal. Alcohol. 1999;17(2):139–147. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(98)00045-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sharpe AL, Samson HH. Repeated nicotine injections decrease operant ethanol self-administration. Alcohol. 2002;28(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/s0741-8329(02)00238-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gonzales RA, Job MO, Doyon WM. The role of mesolimbic dopamine in the development and maintenance of ethanol reinforcement. Pharmacol Ther. 2004;103(2):121–146. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Everitt BJ, Robbins TW. Neural systems of reinforcement for drug addiction: from actions to habits to compulsion. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8(11):1481–1489. doi: 10.1038/nn1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Griffiths RR, Bigelow GE, Liebson I. Facilitation of human tobacco self-administration by ethanol: a behavioral analysis. J Exp Anal Behav. 1976;25(3):279–292. doi: 10.1901/jeab.1976.25-279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mitchell SH, de Wit H, Zacny JP. Effects of varying ethanol dose on cigarette consumption in healthy normal volunteers. Behav Pharmacol. 1995;6(4):359–365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sayette MA, Martin CS, Wertz JM, Perrott MA, Peters AR. The effects of alcohol on cigarette craving in heavy smokers and tobacco chippers. Psychol Addict Behav. 2005;19(3):263–270. doi: 10.1037/0893-164X.19.3.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dani JA, Bertrand D. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors and nicotinic cholinergic mechanisms of the central nervous system. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2007;47:699–729. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.47.120505.105214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dopico AM, Lovinger DM. Acute alcohol action and desensitization of ligand-gated ion channels. Pharmacol Rev. 2009;61(1):98–114. doi: 10.1124/pr.108.000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Funk D, Marinelli PW, Le AD. Biological processes underlying co-use of alcohol and nicotine: neuronal mechanisms, cross-tolerance, and genetic factors. Alcohol Res Health. 2006;29(3):186–192. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Larsson A, Engel JA. Neurochemical and behavioral studies on ethanol and nicotine interactions. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2004;27(8):713–720. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2003.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doyon WM, Thomas AM, Ostroumov A, Dong Y, Dani JA. Potential substrates for nicotine and alcohol interactions: a focus on the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system. Biochem Pharmacol. 2013;86(8):1181–1193. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Luscher C, Malenka RC. Drug-evoked synaptic plasticity in addiction: from molecular changes to circuit remodeling. Neuron. 2011;69(4):650–663. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sulzer D. How addictive drugs disrupt presynaptic dopamine neurotransmission. Neuron. 2011;69(4):628–649. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Volkow ND, Wang GJ, Fowler JS, Logan J, Hitzemann R, Ding YS, et al. Decreases in dopamine receptors but not in dopamine transporters in alcoholics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1996;20(9):1594–1598. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1996.tb05936.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martinez D, Gil MR, Slifstein DR, Hwang Y, Perez Huang A, et al. Alcohol dependence is associated with blunted dopamine transmission in the ventral striatum. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58(10):779–786. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thorndike EL. A proof of the law of effect. Science. 1933;77(1989):173–175. doi: 10.1126/science.77.1989.173-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sidman M. Technique for assessing the effects of drugs on timing behavior. Science. 1955;122(3176):925. doi: 10.1126/science.122.3176.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Weiss B, Laties VG. Effects of amphetamine, chlorpromazine, pentobarbital, and ethanol on operant response duration. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1964;144:17–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doyon WM, York JL, Diaz LM, Samson HH, Czachowski CL, Gonzales RA. Dopamine activity in the nucleus accumbens during consummatory phases of oral ethanol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2003;27(10):1573–1582. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000089959.66222.B8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Samson HH, Slawecki CJ, Sharpe AL, Chappell A. Appetitive and consummatory behaviors in the control of ethanol consumption: a measure of ethanol seeking behavior. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1998;22(8):1783–1787. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Arnold JM, Roberts DC. A critique of fixed and progressive ratio schedules used to examine the neural substrates of drug reinforcement. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1997;57(3):441–447. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(96)00445-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lynch WJ, Nicholson KL, Dance ME, Morgan RW, Foley PL. Animal models of substance abuse and addiction: implications for science, animal welfare, and society. Comp Med. 2010;60(3):177–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samson HH. Initiation of ethanol reinforcement using a sucrose-substitution procedure in food- and water-sated rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 1986;10(4):436–442. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.1986.tb05120.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Carrillo J, Howard EC, Moten M, Houck BD, Czachowski CL, Gonzales RA. A 3-day exposure to 10% ethanol with 10% sucrose successfully initiates ethanol self-administration. Alcohol. 2008;42(3):171–178. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2008.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Simms JA, Bito-Onon JJ, Chatterjee S, Bartlett SE. Long-Evans rats acquire operant self-administration of 20% ethanol without sucrose fading. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2010;35(7):1453–1463. doi: 10.1038/npp.2010.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Katner SN, Magalong JG, Weiss F. Reinstatement of alcohol-seeking behavior by drug-associated discriminative stimuli after prolonged extinction in the rat. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1999;20(5):471–479. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00084-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Windisch KA, Kosobud AE, Czachowski CL. Intravenous alcohol self-administration in the P rat. Alcohol. 2014;48(5):419–425. doi: 10.1016/j.alcohol.2013.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Waller MB, McBride WJ, Gatto GJ, Lumeng L, Li TK. Intragastric self-infusion of ethanol by ethanol-preferring and -nonpreferring lines of rats. Science. 1984;225(4657):78–80. doi: 10.1126/science.6539502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lyness WH, Smith FL. Influence of dopaminergic and serotonergic neurons on intravenous ethanol self-administration in the rat. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1992;42(1):187–192. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(92)90465-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rodd ZA, RL, Melendez RI, Bell KA, Kuc Y, Murphy Zhang JM, et al. Intracranial self-administration of ethanol within the ventral tegmental area of male Wistar rats: evidence for involvement of dopamine neurons. J Neurosci. 2004;24(5):1050–1057. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1319-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Panlilio LV, Goldberg SR. Self-administration of drugs in animals and humans as a model and an investigative tool. Addiction. 2007;102(12):1863–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Clark A, Lindgren S, Brooks SP, Watson WP, Little HJ. Chronic infusion of nicotine can increase operant self-administration of alcohol. Neuropharmacology. 2001;41(1):108–117. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00037-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vendruscolo LF, Barbier E, Schlosburg JE, Misra KK, Whitfield TW, Jr, Logrip ML, et al. Corticosteroid-dependent plasticity mediates compulsive alcohol drinking in rats. J Neurosci. 2012;32(22):7563–7571. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0069-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Funk CK, O’Dell LE, Crawford EF, Koob GF. Corticotropin-releasing factor within the central nucleus of the amygdala mediates enhanced ethanol self-administration in withdrawn, ethanol-dependent rats. J Neurosci. 2006;26(44):11324–11332. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3096-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okada S, Shimizu T, Yokotani K. Extrahypothalamic corticotropin-releasing hormone mediates (−)-nicotine-induced elevation of plasma corticosterone in rats. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;473(2–3):217–223. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01966-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Tucci S, Cheeta S, Seth P, File SE. Corticotropin releasing factor antagonist: alpha-helical CRF(9–41), reverses nicotine-induced conditioned, but not unconditioned, anxiety. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2003;167(3):251–256. doi: 10.1007/s00213-003-1403-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.File SE, Cheeta S, Irvine EE, Tucci S, Akthar M. Conditioned anxiety to nicotine. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2002;164(3):309–317. doi: 10.1007/s00213-002-1219-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Le AD, Corrigall WA, Harding JW, Juzytsch W, Li TK. Involvement of nicotinic receptors in alcohol self-administration. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2000;24(2):155–163. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2000.tb04585.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Leao RM, Cruz FC, Vendruscolo LF, de Guglielmo G, Logrip ML, Planeta CS, et al. Chronic nicotine activates stress/reward-related brain regions and facilitates the transition to compulsive alcohol drinking. J Neurosci. 2015;35(15):6241–6253. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3302-14.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Le AD. Effects of nicotine on alcohol consumption. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2002;26(12):1915–1916. doi: 10.1097/01.ALC.0000040963.46878.5D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wortley PM, Husten CG, Trosclair A, Chrismon J, Pederson LL. Nondaily smokers: a descriptive analysis. Nicotine Tob Res. 2003;5(5):755–759. doi: 10.1080/1462220031000158753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Schane RE, Glantz SA, Ling PM. Nondaily and social smoking: an increasingly prevalent pattern. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(19):1742–1744. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Pierce JP, White MM, Messer K. Changing age-specific patterns of cigarette consumption in the United States, 1992–2002: association with smoke-free homes and state-level tobacco control activity. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(2):171–177. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Owen N, Kent P, Wakefield M, Roberts L. Low-rate smokers. Prev Med. 1995;24(1):80–84. doi: 10.1006/pmed.1995.1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Hennrikus DJ, Jeffery RW, Lando HA. Occasional smoking in a Minnesota working population. Am J Public Health. 1996;86(9):1260–1266. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.9.1260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hassmiller KM, Warner KE, Mendez D, Levy DT, Romano E. Nondaily smokers: who are they? Am J Public Health. 2003;93(8):1321–1327. doi: 10.2105/ajph.93.8.1321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Levy DE, Biener L, Rigotti NA. The natural history of light smokers: a population-based cohort study. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11(2):156–163. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Kemppainen H, Hyytia P, Kiianmaa K. Behavioral consequences of repeated nicotine during adolescence in alcohol-preferring AA and alcohol-avoiding ANA rats. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2009;33(2):340–349. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2008.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Heilig M, Egli M. Pharmacological treatment of alcohol dependence: target symptoms and target mechanisms. Pharmacol Ther. 2006;111(3):855–876. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KA, Bergquist K, Bhagwagar Z, Siedlarz KM. Enhanced negative emotion and alcohol craving, and altered physiological responses following stress and cue exposure in alcohol dependent individuals. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34(5):1198–1208. doi: 10.1038/npp.2008.78. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Mason BJ, Light JM, Escher T, Drobes DJ. Effect of positive and negative affective stimuli and beverage cues on measures of craving in non treatment-seeking alcoholics. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2008;200(1):141–150. doi: 10.1007/s00213-008-1192-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Le AD, Lo S, Harding S, Juzytsch W, Marinelli PW, Funk D. Coadministration of intravenous nicotine and oral alcohol in rats. Psychopharmacology. 2010;208(3):475–486. doi: 10.1007/s00213-009-1746-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hauser SR, Getachew B, Oster SM, Dhaher R, Ding ZM, Bell RL, et al. Nicotine modulates alcohol-seeking and relapse by alcohol-preferring (P) rats in a time-dependent manner. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2012;36(1):43–54. doi: 10.1111/j.1530-0277.2011.01579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lopez-Moreno JA, Trigo-Diaz JM, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Gonzalez Cuevas G, Gomez de Heras R, Crespo Galan I, et al. Nicotine in alcohol deprivation increases alcohol operant self-administration during reinstatement. Neuropharmacology. 2004;47(7):1036–1044. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Lopez-Moreno JA, Scherma M, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Gonzalez-Cuevas G, Fratta W, Navarro M. Changed accumbal responsiveness to alcohol in rats pretreated with nicotine or the cannabinoid receptor agonist WIN 55212-2. Neurosci Lett. 2008;433(1):1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2007.11.074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Marinelli M, Rudick CN, Hu XT, White FJ. Excitability of dopamine neurons: modulation and physiological consequences. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2006;5(1):79–97. doi: 10.2174/187152706784111542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Nie H, Rewal M, Gill TM, Ron D, Janak PH. Extrasynaptic delta-containing GABAA receptors in the nucleus accumbens dorsomedial shell contribute to alcohol intake. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(11):4459–4464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1016156108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Nowak KL, McBride WJ, Lumeng L, Li TK, Murphy JM. Blocking GABA(A) receptors in the anterior ventral tegmental area attenuates ethanol intake of the alcohol-preferring P rat. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1998;139(1–2):108–116. doi: 10.1007/s002130050695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Armario A. Activation of the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis by addictive drugs: different pathways, common outcome. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010;31(7):318–325. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Richardson HN, Lee SY, O’Dell LE, Koob GF, Rivier CL. Alcohol self-administration acutely stimulates the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis, but alcohol dependence leads to a dampened neuroendocrine state. Eur J Neurosci. 2008;28(8):1641–1653. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2008.06455.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Sinha R, Fox HC, Hong KI, Hansen J, Tuit K, Kreek MJ. Effects of adrenal sensitivity, stress- and cue-induced craving, and anxiety on subsequent alcohol relapse and treatment outcomes. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(9):942–952. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Piazza PV, Deroche V, Deminiere JM, Maccari S, Le Moal M, Simon H. Corticosterone in the range of stress-induced levels possesses reinforcing properties: implications for sensation-seeking behaviors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90(24):11738–11742. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.24.11738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Barrot M, Marinelli M, Abrous DN, Rouge-Pont F, Le Moal M, Piazza PV. The dopaminergic hyper-responsiveness of the shell of the nucleus accumbens is hormone-dependent. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12(3):973–979. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00996.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Butts KA, Weinberg J, Young AH, Phillips AG. Glucocorticoid receptors in the prefrontal cortex regulate stress-evoked dopamine efflux and aspects of executive function. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(45):18459–18464. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1111746108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Barik J, Marti F, Morel C, Fernandez SP, Lanteri C, Godeheu G, et al. Chronic stress triggers social aversion via glucocorticoid receptor in dopaminoceptive neurons. Science. 2013;339(6117):332–335. doi: 10.1126/science.1226767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wanat MJ, Bonci A, Phillips PE. CRF acts in the midbrain to attenuate accumbens dopamine release to rewards but not their predictors. Nat Neurosci. 2013;16(4):383–385. doi: 10.1038/nn.3335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Fahlke C, Hansen S. Effect of local intracerebral corticosterone implants on alcohol intake in the rat. Alcohol Alcohol. 1999;34(6):851–861. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/34.6.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grieder TE, Herman MA, Contet C, Tan LA, Vargas-Perez H, Cohen A, et al. VTA CRF neurons mediate the aversive effects of nicotine withdrawal and promote intake escalation. Nat Neurosci. 2014;17(12):1751–1758. doi: 10.1038/nn.3872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nie Z, Schweitzer P, Roberts AJ, Madamba SG, Moore SD, Siggins GR. Ethanol augments GABAergic transmission in the central amygdala via CRF1 receptors. Science. 2004;303(5663):1512–1514. doi: 10.1126/science.1092550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Roberto M, Cruz MT, Gilpin NW, Sabino V, Schweitzer P, Bajo M, et al. Corticotropin releasing factor-induced amygdala gamma-aminobutyric acid release plays a key role in alcohol dependence. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67(9):831–839. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Olive MF, Koenig HN, Nannini MA, Hodge CW. Elevated extracellular CRF levels in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis during ethanol withdrawal and reduction by subsequent ethanol intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002;72(1–2):213–220. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00748-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Lowery Gionta EG, Navarro CM, Li KE, Pleil JA, Cox Rinker BR, et al. Corticotropin releasing factor signaling in the central amygdala is recruited during binge-like ethanol consumption in C57BL/6J mice. J Neurosci. 2012;32(10):3405–3413. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6256-11.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Tagliaferro P, Morales M. Synapses between corticotropin-releasing factor-containing axon terminals and dopaminergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area are predominantly glutamatergic. J Comp Neurol. 2008;506(4):616–626. doi: 10.1002/cne.21576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Rodaros D, Caruana DA, Amir S, Stewart J. Corticotropin-releasing factor projections from limbic forebrain and paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus to the region of the ventral tegmental area. Neuroscience. 2007;150(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.09.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Hwa LS, Debold JF, Miczek KA. Alcohol in excess: CRF(1) receptors in the rat and mouse VTA and DRN. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2013;225(2):313–327. doi: 10.1007/s00213-012-2820-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]