Abstract

Background: Racial disparities in health across the United States remain, and in some cities have worsened despite increased focus at federal and local levels. One approach to addressing health inequity is community-based participatory research (CBPR).

Objectives: The purpose of this paper is to describe the develop ment of an ongoing community–physical therapy partnership focused on physical activity (PA), which aims to improve the health of African-American community members and engage physical therapist (PT) students in CBPR.

Methods: Three main research projects that resulted from an initial partnership-building seed grant include (1) community focus groups, (2) training of community PA promoters, and (3) pilot investigation of PA promoter effectiveness.

Lessons Learned: Results from each project informed the next. Focus groups findings led to development of a PA pro moter training curriculum. PA promoters were accepted by the community, with potential to increase PA. Focus on the community issue of PA fostered and sustained the partnership.

Conclusions: Community and academic partners benefitted from funding, structure, and time to create meaningful, trusting, and sustainable relationships committed to improving health. Engaging PT students with community residents provided learning opportunities that promote respect and appreciation of the social, economic, and environmental context of future patients.

Keywords: Community-based participatory research, community health partnerships, health disparities, process issues, physical activity, physical therapy

Racial disparities in health across the United States remain and in some cities (e.g., Chicago) have worsened despite increased focus at federal and local levels.1–4 One approach to addressing health inequity is CBPR, in which community members participate as partners in research and are invested in responding to and disseminating the results. CBPR’s collaborative relationships between community and academic partners share a focus on health concerns of importance to the community.5,6 Building these meaningful and productive partnerships takes time to develop trust and commitment from both organizations.5,6

Of Chicago’s 77 community areas, Austin is the most densely populated with over 98,514 residents. It is 90% African American and 24% of Austin residents live below the poverty line.7 The Westside Health Authority (WHA), established in 1988, is the primary community health organization committed to using the capacity of local residents to improve the health and well-being of Austin residents across the lifespan. WHA has a long history of successful community-based, action-oriented, coalition building beginning with its organizing efforts to stop a local hospital from closing. Furthermore, while working with academics and foundations, it has trained community members to conduct health research in Austin since 1992.8 Based on results from this work, WHA implemented its Body and Soul program, which initially addressed the health concerns of African-American men, but with success the program expanded to include services for women and youth.

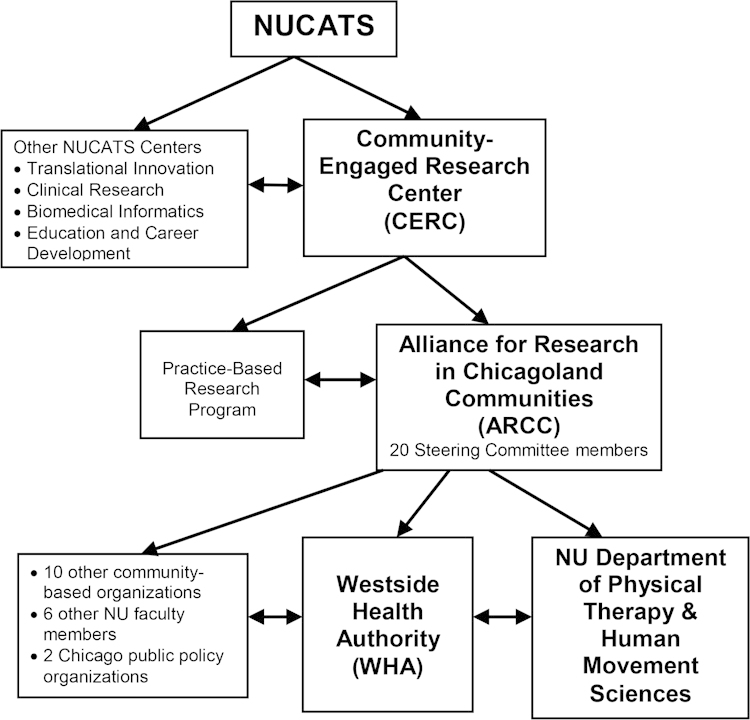

The Northwestern University Clinical and Translational Science Institute (NUCATS), established in 2007 through a grant from the National Institutes of Health (NIH), includes five centers, one of which is the community-engaged research center (CERC). CERC is committed to improving community health by facilitating collaborative research partnerships that include Chicago-area organizations, community-based clinicians, and Northwestern University (NU) academic partners. One key program of CERC is the Alliance for Research in Chicagoland Communities (ARCC). ARCC’s mission is “growing equitable and collaborative partnerships between Chicago area communities and NU for research that leads to measurable improvement in community health.” The authors of this paper are Steering Committee members of ARCC (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Northwestern University Clinical and Translation Science Institute (NUCATS)

A relationship between WHA and the NU Department of Physical Therapy and Human Movement Sciences (PTHMS) started in 2004, when a faculty member contacted WHA after reading a journal article describing a hospital–community teaching partnership between WHA and a large public hospital in Chicago.9 Hospital medical residents learned about health disparities from WHA community health advocates (CHAs), who discussed their health care experiences and gave a guided tour of their community. The PTHMS faculty member invited the CHAs to share their experiences in small group discussions with first-year PT students. This introduced the academic authors of this paper (Healey and Huber) to WHA and the work done in the Austin community.

During the same time period, WHA disseminated findings in a local newspaper from their National Center of Minority Health and Health Disparities grant that addressed health disparities (Community Healthy Lifestyles Project, C-HeLPRFA-MD-05-002). Reed (the community co-author of this paper) was a contributing author of the C-HeLP grant and has been a nurse consultant with WHA since 2003. The CBPR academic partner for C-HeLP was from NU School of Medicine and a key component of the project was to train the CHAs in CBPR. Eight CHAs, trained by C-HeLP in survey research design and methods, conducted a health assessment of more than 300 Austin households. In addition, the CHAs learned small group facilitation skills in topics related to nutrition, PA, and emotional well-being.10 The C-HeLP survey identified lack of PA—especially among older adults—as a health issue.

CERC identified WHA and their experienced CHAs as a potential partner for community engagement. CHAs, sometimes referred to as community health workers, have worked in low-income, ethnic minority communities to improve access to care, knowledge, health status, and behavior change.11 Healey and Huber realized that the previous relationship between WHA and PTHMS could be expanded to a broader collaboration to meet the health care needs of Austin residents and provide additional learning opportunities for PT students and faculty while engaging with the community through service-learning activities. CHAs previously spent time sharing their experiences with PT students; however, service learning could allow for a structured reciprocal experience to combine addressing community needs with academic education.12 Two individuals from WHA, the C-HeLP project manager (J. Lewis) and a long-time and current consultant to the organization (C. Kohrman), met with Healey and Huber and collaboratively identified opportunities to work together on increasing PA in the Austin community. WHA and PTHMS acknowledged that they would like to seek out funding opportunities to foster an equitable working relationship.

Seifer identified time spent in CBPR partnerships as essential in developing relationships, building trust, and engaging in participatory application of the research processes.13 The two community and two academic individuals applied for and were awarded a 2009–2010 CERC ARCC Partnership-Building Seed Grant, which provided structure and commitment to developing the community-academic relationship over time. The purposes of this paper are to describe (1) the development of the ongoing partnership between WHA and PTHMS (WHA/PTHMS), which aims to improve the health of Austin residents and (2) the engagement of students in CBPR, which aims to expand their learning and development as future health professionals.

Methods

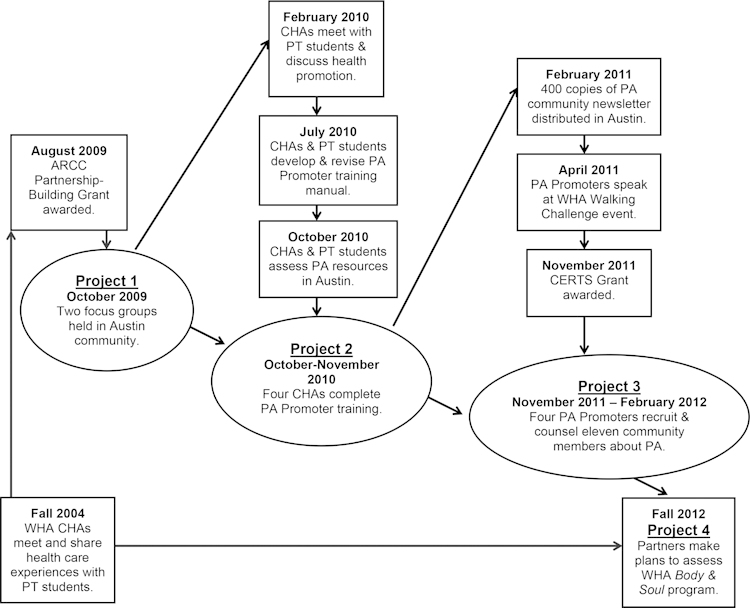

This section describes the methods and results for three main research projects that resulted from the initial Partnership-Building Seed Grant and illustrate the partnership’s growth as well as describe how students were involved in community activities and research. A timeline of partnership activities leading to and following each project is found in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Timeline of Partnership Activities

Institutional review board approval was received from NU for all three projects. When obtaining consent, research investigators provided a verbal overview of the project in a group or one-on-one format, allowed time for questions and answers, and provided a consent form copy to participants. Two individuals declined to participate in project three owing to the time commitment; otherwise, all invited community residents consented in projects one and two.

Project One

This project focused on concerns about low levels of PA in Austin and ways to assist in the development of community interventions using results from the C-HeLP research study. This project used focus group methods to describe community members’ attitudes about PA. Four previously trained CHAs from C-HeLP were recruited. The CHAs were paid for collaborating with the project investigators in developing the focus group questions, recruitment of Austin residents by personal contact, and discussion of results. Participants were paid for attending the focus groups. Two students participated in this project as research assistants. They presented an overview of physical therapy to the CHAs and were responsible for assisting in the focus group data collection, data analysis, and discussion with CHAs about results and next steps.

Two focus groups were held on separate evenings at WHA lasting 1½ to 2 hours. The focus groups were co-facilitated by WHA community (Lewis and Kohrman) and PTHMS investigators (Healy and Huber). A total of 22 participants attended: 16 women and 6 men; average age was 70.6 years (range, 62–91). The academic partners analyzed the transcribed audiotapes and developed codes and a preliminary set of themes. Community investigators, academic investigators, and CHAs met over 3 months to interpret the findings. Four themes emerged and are italicized and described below.

Participants described a healthy person as having a healthy mind; being free from illness or has disease under control; eats right; comes from a healthy family; and can get out and go where they want or do what they want. One participant stated, “I have a friend in her 90s, she is out all the time out in the street.” When asked about what they do to stay healthy, participant responses focused on watching what they eat; getting rest and relaxation; and being active or exercising, as exemplified by this quote, “I don’t know about exercising . . . I know staying busy.”

Participants were knowledgeable about PA in their community. They knew where to go in Austin, identified a wide variety of activities as exercise or PA including unique activities (working on cars, motor cycles, small engines), and recognized specific benefits of exercise. These individuals also reported environmental barriers. Safety and maintenance of outdoor areas of parks were concerns, one participant noted, “There are no accessible washrooms . . . the water fountains don’t work . . . you can’t get into the building until 8:30 or 9:00.”

Family and social support were both barriers and facilitators of PA according to focus group participants. Family responsibilities take priority and may preclude being active or exercising. One participant stated, “Even though I know it would be better for my health, the other people and things that they need to do set a priority over mine.” However, family and social networks also facilitated PA, with children motivating parents and grandparents.

The focus group participants provided rich information about PA in their lives, which enhanced WHA/PTHMS partners’ understanding. The CHAs and WHA/PTHMS investigators reviewed the focus group findings, and together decided to train community peers who would influence their social contacts to become more active.

Project Two

This project was based on the results from the focus groups and discussion with the CHAs, who suggested a peer-based approach to increasing PA. The goals of this project were to (1) develop and evaluate the effectiveness of a PA promoter training curriculum, (2) perform a PA resource inventory in Austin, and (3) develop and disseminate a PA community newsletter.

The CHAs from project one collaborated with five students in determining content for a PA promoter training curriculum that would benefit the community. These CHAs were the first group of Austin residents to go through the three 2-hour PA promoter trainings conducted over 3 weeks. The 56-page training curriculum covered topics related to the benefits of PA, ways to increase PA in daily life, types of structured exercise, and how to help others overcome barriers.14 The CHAs were paid for their time to complete the training from PTHMS research funds. Evaluation of the curriculum included verbal and written feedback on the content and methods after each training session and a pre- and post-curriculum content quiz.

Participant feedback on the curriculum delivery was positive overall. Although pre- and post-training quiz scores that assessed PA knowledge were mixed, the CHAs received a Certificate of Achievement as a PA Promoter on completion of their training and their informal and formal feedback was used to revise the initial training curriculum.

The PA resource inventory of four Chicago Park District or Senior Services sites used the International Council on Active Aging Facility Inventory and was jointly conducted by students and PA promoters.15 The students and PA promoters created and distributed 400 copies of a PA community newsletter at a variety of Austin locations and through the promoters’ social networks. Information from the PA resource inventory and newsletter were used as resources for the PA promoters. Five months post-training, the PA promoters participated in the first WHA 5K walking challenge kickoff event held at a local park district to introduce them and create awareness of their goals.

Project Three

The academic investigators led this project, but the work was supported by WHA. During this time, one of the community investigators took on another role at another organization. However, the WHA executive director was committed to maintaining a relationship with PTHMS, so the academic investigators suggested conducting a pilot investigation of the effectiveness of the PA promoters that involved two students and four PA promoters. The four trained PA promoters (two from the initial training program and two newly trained community members) recruited two to three community volunteers each and counseled them weekly for 3 months on the benefits of PA and ways to increase activity level. Changes in the volunteers’ PA behaviors were assessed through accelerometry data, self-report surveys, and physiologic measures. Data were collected at the start and end of the PA promoter counseling intervention. Monthly meetings with the PA promoters were held during the study to discuss counseling strategies.

The PA promoters recruited eleven participants (8 women, 3 men; average age 66.5 years; range, 54–81). The PA promoters were paid $100 monthly for 3 months for their recruitment efforts and counseling sessions. Outcome measures pre- and post-intervention were the 6-minute walk test (6MWT),16,17 Short Form Health Survey,18 Self-Efficacy for Exercise Scale,19 and accelerometer measures for 1 consecutive week.

Outcome measures were not significant except the average 6MWT distance, which increased by 91.6 meters (greater than a minimally clinically important difference).20 Accelerometry data showed that 93% of time was spent in sedentary behavior and 7% in light, with negligible periods of moderate/vigorous activity. Accelerometry results in this small sample revealed the need to focus on reducing sedentary behavior. As a result of this pilot study, we found that contact with PA promoters led to a clinically meaningful increase in 6MWT (a proxy for functional capacity) with the potential to increase PA in this community. Final results of the project were presented to the PA promoters, study participants and WHA health promotions director.

Projects two and three were research projects the students completed as part of their PT educational requirements. In addition to these research roles, multiple students volunteered to participate in community-based activities sponsored by WHA, including walking activities, screening of middle-aged and older adults, and school-based PA programming. These students signed up to participate based on announcements made by faculty members or their peers.

Lessons Learned

In project one, a lesson learned by community partners was their significant contribution in recruiting focus group participants. CHAs and community investigators liked the shared responsibility of interpreting pilot data to shape the future research directions of the partnership. Academic partners’ original plans for implementing PA interventions changed as a result of CHA input—actively listening to and responding to the community voice was an important lesson learned.

In project two, the PA promoter training curriculum provided Austin CHAs the tools needed to deliver general health and fitness information to their neighbors. They were recognized as a community resource. A lesson learned by the community partner was the need to have clear expectations of the academic partner—this led to the discussion to develop a memorandum of understanding (MOU) to outline the expectations of themselves and research partners in future projects. A lesson learned by the academic and student partners was importance of effective communication methods; frequent and reliable communication is a necessity.

In project three, lessons learned by the PA promoters were challenges in recruitment and retention of research study participants. Investigators encouraged CHAs to recruit participants, but the CHAs found the recruitment process difficult. CHAs reported they would like the recruitment process to be a shared responsibility with academic investigators in the future. The challenges may have been a result of the change in the community investigator and the time it took for the new investigator to establish a relationship with the CHAs. Key community stakeholders (CHAs) and community investigators committed to research are important to ensure community involvement in research projects. Although there were staffing changes at WHA, they were committed to understanding the efficacy of the PA promoter project to find best practices to improve the health of Austin residents. Institutional commitment of the community and academic partners is an important component to ensure that relationships are maintained, even if individual investigators are no longer with the institution.

Student Engagement

Lessons learned by the community included acknowledging that it takes time for students to cultivate relationships with community members. Community members find it difficult to relate to students, given students’ inability to spend significant time outside the classroom. Community members built better relationships with PT students who volunteered in year 1 of their program at WHA special events, then engaged in the research process in projects two and three. Community members understand that student educational programs are 3 years long; therefore, student engagement is limited to this time. However, members appreciate consistent time spent with students while they are in their program of study, preferably on a consistent weekly or monthly basis. An important component of trust and relationship building was the consistent presence of the academic partners throughout the three projects as they engaged students at various stages of study. It may be advantageous for student programs to include volunteer or service-learning hours early in a program of study to begin to form relationships even before the students engage in formal research or practice projects. In this way, students have experiences with the community throughout their educational program, which allows them to contribute to the community while also building their capacity as future health professionals.21

Next Steps

Lack of trust and respect is well-described in CBPR literature as a potential area of tension and barrier to creating and sustaining successful collaboratives.5 Building long-lasting relationships takes time, but academic partners were still surprised by the lack of concrete outcomes and feelings of mutual trust after several years of effort. WHA and PTHMS leadership were aware of and supported the relationship between the director of health promotions and faculty members, but a formal agreement of understanding between the two organizations was not in place. An MOU between WHA and PTHMS leadership to ensure organizational commitment of both parties was established in late 2012. The MOU details a framework for academic/student and community engagement to manage the fluid role of academic students and community staff. We wanted to ensure that the CBPR approach was accepted within WHA and that students are required to have consistent volunteer hours throughout their course of study before and after they engage in a formal research project. Increased time together, open discussion of partner perspectives, and agreement on shared goals all promoted the trusting and sustainable relationship that currently exits. Maintaining this relationship requires attention to development and adherence to CBPR principles.22 Overall, major principles of CBPR noted by Parker and co-workers23 were achieved.

Managing transitions within the partnership for community and academics was challenging. WHA hosted nine students during the course of the three projects owing to their transition through courses and progression through school and nearly 20 total at various health fairs. The primary WHA partner, the director of health promotions, changed three times since 2009. Additionally, a community advisory board on PA in Austin will be convened by WHA to provide additional perspectives and ensure all academic, community partner, and community stakeholder voices are heard.22

Students’ comments throughout their experiences in Austin reflected a deeper appreciation and respect for the social, economic, and environmental context of their future patients. We believe their community engagement has shaped their future practice. However, formal assessment of students’ perspectives and attitudes related to their experiences was not done. Academic and community partners plan to assess change in students’ perceptions over time on their professional roles in the community, impact on career, and working in a diverse community.24 Review of student perspectives after their community experiences will help to identify factors influencing their professional preparation.

The funding from ARCC has been critical to the development of this partnership. Funding for community members, academic faculty, staff involvement, and purchasing project or organizational equipment is important when considering sustainability. We were fortunate in initial support from ARCC, which provided structured time and regular meetings to work toward shared project goals. We recently received additional financial support for our partnership though Community-Engaged Research Team Support (CERTS), an NIH-funded NUCATS grant. CERTS facilitated monthly meetings and further defined research questions and approaches focused on WHA’s Body and Soul program, which is the basis of the partnership’s upcoming project four.

Conclusions

Initial projects built the partners knowledge of each other and community and academic capacity. WHA and Austin residents working with the academic partners were critical to obtaining knowledge of the community. The projects started with small, achievable goals and as trust in the partners’ commitment developed we have become more deeply engaged with a broader number of activities. We have become reliant on each other for volunteers; community members come to class to discuss their life experiences and the students are essential manpower for community events. WHA and PTHMS are committed to this partnership and believe that health professions student engagement in the community is a powerful learning experience in understanding and respecting the social, economic, and environmental context of future practice to improve health outcomes in underserved communities. We also believe that CBPR and the engagement of student health workers can improve health outcomes in underserved communities and, specifically in this case, improve the PA of Austin residents.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the Austin residents, WHA CHAs, PA promoters—especially Ms. Orlean Huntley, who shared her views on her roles in all three projects, and the PT students who have been involved with and contributed to the partnership. The authors especially thank Claire Kohrman, PhD, for her continued community work in Austin, for bringing us together, and for her helpful feedback and suggestions to this manuscript.

The Body & Soul program described was supported by Advocate Bethany Community Health Fund. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH. Additional support was provided by NUCATS ARCC Seed Grant and Faculty Development Mini-Grant programs (www.ARCConline.net).

References

Orsi J, Amargellos-Anast H, Whitman S. Black-white health disparities in the United States and Chicago: A 15-year progress analysis. Am J Public Health. 2010;100:349–356. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2009.165407.

Safford M, Brown T, Muntner P, et al. Association of race and sex with risk of incident acute coronary heart disease events. JAMA. 2012;308:1768–1774. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14306.

Cullen M, Cummins C, Fuchs V. Geographic and racial variation in premature mortality in the U.S.: Analyzing the disparities. PLoS One. 2012;7:e32930. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0032930.

CDC Surveillance of health status in minority communities-racial and ethnic approaches to community health across the U.S. (REACH U.S.) risk factor survey, United States. MMWR. 2011;60(SS-6):1–42.

Israel B, Schulz A, Parker E, Becker A. Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annu Rev Public Health. 1998;19:173–202. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.19.1.173.

Israel B, Eng E, Schulz A, Parker E, editors. Methods in community-based participatory research for health. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2005.

Chicago Department of Public Health . Chicago Health and health systems project. Chicago: Author; 2006.

RWJ . Opening doors: A program to reduce sociocultural barriers to health care. Princeton (NJ): Robert Wood Johnson Foundation; 1998.

Jacobs E, Kohrman C, Lemon M, Vickers D. Teaching physicians-in-training to address racial disparities in health: a hospital-community partnership. Public Health Rep. 2003;118:349–356. doi: 10.1093/phr/118.4.349.

A community-based healthy lifestyles partnership . Bethesda (MD): National Center of Minority Health and Health Disparities; 2005–2008.

Swider SM. Outcome effectiveness of community health workers: An integrative literature review. Public Health Nurs. 2002;19(1):11–20. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1446.2002.19003.x.

Marcus MT, Taylor WC, Hormann MD, Walker T, Carroll D. Linking service-learning with community-based participatory research: An interprofessional course for health professional students. Nurs Outlook. 2011;59(1):47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.outlook.2010.10.001.

Seifer S. Building and sustaining community-institutional partnerships for prevention research: Findings from a national collaborative. J Urban Health. 2006;83:989–1003. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9113-y.

National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health Exercise & physical activityPublication No. 09-4258. Baltimore: Author; 2010.

International Council on Active Aging (ICAA) facility inventory [cited 2011 Nov 1]. Available from: http://www.icaa.cc/

Harada N, Chiu V, Stewart A. Mobility-related function in older adults: Assessment with 6-minute walk test. Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:558–567. doi: 10.1016/s0003-9993(99)90236-8.

American Thoracic Society (ATS) American Thoracic Society statement: Guidelines for the six-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:111–117. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.166.1.at1102.

Ware J, Kosinski M, Keller S. A 12-item short-form health survey: Construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34:220–233. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003.

Resnick B, Luigi D, Vogel A, Junaleepa p. Reliability and validity of the self-efficacy for exercise and outcome expectations for exercise scales with minority older adults. J Nurs Res. 2004;12:235–247. doi: 10.1891/jnum.12.3.235.

Dolmage T, Hill K, Evans R, Goldstein R. Has my patient responded? Interpreting clinical measurements such as the 6-minute walk test. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184:642–646. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201103-0497CC.

Hoppes S, Bender D, DeGrace BW. Service learning is a perfect fit for occupational and physical therapy education. J Allied Health. 2005;34:47–50.

Israel B, Krieger J, Vlahov D, et al. Challenges and facilitating factors in sustaining community-based participatory research partnerships: lessons learned from the Detroit, New York City and Seattle urban research centers. J Urban Health. 2006;83(6):1022–1040. doi: 10.1007/s11524-006-9110-1.

Parker EA, Israel BA, Williams M, et al. Examining the partnership process of a community-based participatory research project. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18:558–567. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.20322.x.

Community–Campus Partnerships for Health, Service Learning Resources . Methods and strategies for student assessment. San Francisco, CA: Author; 2001.

Contributor Information

William E. Healey, Department of Physical Therapy and Human Movement Sciences Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Monique Reed, Department of Physical Therapy and Human Movement Sciences Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine.

Gail Huber, Westside Health Authority; Rush University School of Nursing.