Abstract

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most common type of dementia, but early and accurate diagnosis remains challenging. Previously, a panel of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) biomarker candidates distinguishing AD and non-AD CSF accurately (> 90%) was reported. Furthermore, a multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) assay based on nano liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (nLC-MS/MS) was developed to help validate putative AD CSF biomarker candidates including proteins from the panel. Despite the good performance of the MRM assay, wide acceptance may be challenging because of limited availability of nLC-MS/MS systems laboratories. Thus, here, a new MRM assay based on conventional LC-MS/MS is presented. This method monitors 16 peptides representing 16 (of 23) biomarker candidates that belonged to the previous AD CSF panel. A 30-times more concentrated sample than the sample used for the previous study was loaded onto a high capacity trap column, and all 16 MRM transitions showed good linearity (average R2 = 0.966), intra-day reproducibility (average coefficient of variance (CV) = 4.78%), and inter-day reproducibility (average CV = 9.85%). The present method has several advantages such as a shorter analysis time, no possibility of target variability, and no need for an internal standard.

Keywords: Alzheimer's disease, cerebrospinal fluid, biomarker, multiple reaction monitoring

Introduction

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive neurodegenerative dementia and the sixth leading cause of death in the United States. More than 5.2 million Americans (about 96% are older than age 65) are estimated to live with AD.1 Considering the growing incidence of AD and related dementias, the estimated costs of caring for people in the US with these diseases will increase from $214 billion in 2014 to $1.2 trillion in 2050. 1 Five drugs to delay the progress of cognitive decline are currently available to AD patients and managing early AD patients with these drugs is known to be more effective than at later stages of the disease.1–3 Thus, it is critical to diagnose AD at its earliest stage, but a definitive AD diagnosis is not yet available.4 As a result, there is significant effort being made to develop molecular tests using various biological fluids with particular interest in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) because of its proximity to brain.5–17 We previously reported a panel of AD CSF biomarker candidates that showed 93% sensitivity and 90% specificity to differentiate AD CSF and non-AD CSF using two-dimensional gel electrophoresis and matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time of flight tandem mass spectrometry (MALDI TOF/TOF MS).18 To help facilitate validation of those biomarker candidates of the panel, a nano liquid chromatography multiple reaction monitoring tandem mass spectrometry (nLC-MRM/MS) method targeting 24 peptides representing different AD CSF biomarker candidates reported in various studies (including our previous one18) was also developed.19 This method showed good linearity (average R2 = 0.969) and reproducibility (average coefficient of variance (CV) = 6.93%) for the MRM transitions. Nonetheless, there are challenges to the adoption of any nLC-based MRM method, because nano liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry (nLC-MS/MS) systems are relatively less common in laboratories because of their cost and expertise required to address issues with clogging, void volumes, leaks, and dead volumes.20 Additionally, some researchers have suggested that nLC-MS/MS may not be the best option for proteomics applications because of limited sample loading, a critical factor for the success of proteomics, and others.21–24

Here, a new version of the MRM assay that utilizes conventional LC-MS/MS instead of nLC-MS/MS is reported. This LC-MRM/MS method monitors 16 biomarker candidates that belonged to the previous AD CSF biomarker panel from non-depleted human CSF. A 30-times more concentrated sample than that used for our previous study based on nLC-MS/MS was loaded onto a high capacity trap column to compensate for the loss of LC-MS/MS sensitivity and all 16 MRM transitions showed good analytical performance. Additionally, this new method provides several advantages including a shorter analysis time, no possibility of target variability issues, and no need for an internal standard.

Materials and Methods

CSF sample preparation

This work has been approved by the University of Delaware Institutional Review Board. A pooled normal CSF sample was purchased from Biochemed Services (Winchester, VA, USA). The CSF was shipped on dry ice and stored at −70°C until needed. Buffer exchange was carried out prior to digesting the CSF proteins. Three mL of CSF sample was loaded onto an Amicon Ultra-4 10 kDa cutoff filter (Millipore, Billercia, MA, USA), and the volume was increased to 4 mL by adding 0.2 M ammonium bicarbonate. The filter unit was centrifuged at 7,500 ×g for 30 min, and the buffer exchange steps were repeated twice. The final retentate was transferred and dried by vacuum centrifugation. The dried residue, including the CSF proteins, was resuspended, denatured, and reduced with 100 µL 6.0 M urea (in 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate) and 5 µL of 200 mM dithiothreitol (DTT, in 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate) for an hour at room temperature (RT). A 20 µL aliquot of 200 mM iodoacetamide (in 0.1 M ammonium bicarbonate) was added, and the mixture was incubated for an hour at RT in the dark to alkylate the reduced proteins. After quenching the remaining iodoacetamide with 20 µL of 200 mM DTT for an hour at RT, the solution was mixed with 775 µL of 40 mM ammonium bicarbonate and 100 µL trypsin (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) dissolved (20 µg in 100 µL) in its dissolution buffer (Promega) for protein digestion. After a 14 h incubation of the solution at 37°C, 1 µL of 20% formic acid was added to terminate the digestion process. The resulting solution was dried by vacuum centrifugation and then dissolved in 1 mL 0.1% formic acid (the CSF digest sample). One mg of bovine alpha casein (CASA, Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was suspended, denatured, alkylated, digested, and dried following the same protocols mentioned above to prepare the internal standard solution. The dried digest was resuspended in 1 mL of 0.1% formic acid and spiked into the CSF digest sample to a specific concentration as an internal standard after a serial dilution (when appropriate).

LC-MS/MS and LC-MRM/MS

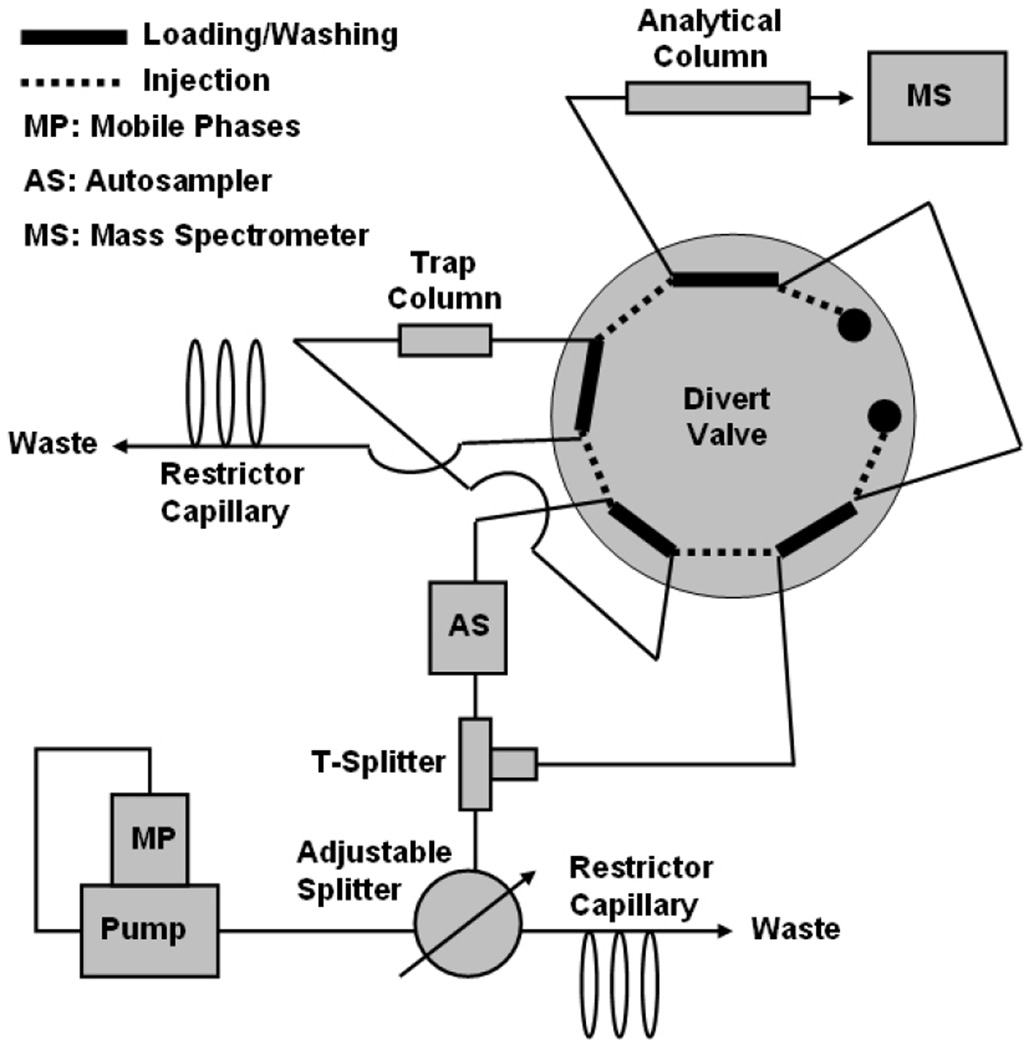

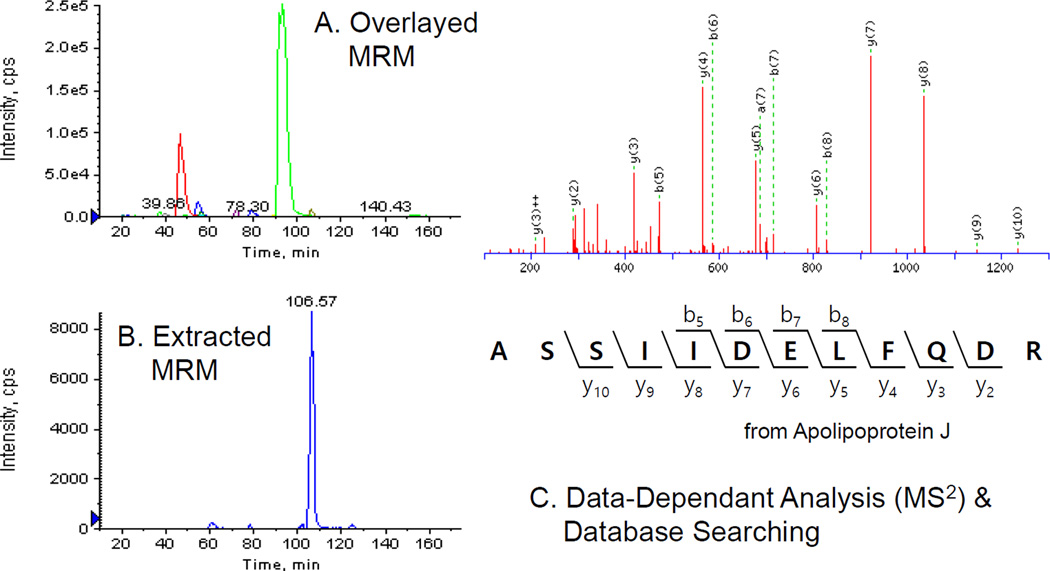

A portion of the digested sample was separated on an Agilent 1100 LC system (Santa Clara, CA, USA). First, the digested sample was loaded onto an Agilent Zorbax 300SB C18 trap column (0.3 × 5 mm, 5 µm, flow rate of 8 µL/min) or a Phenomenex Security Guard C18 column (Torrance, CA, USA) (3 × 4 mm, 5 µm, flow rate of 200 µL/min) for on-line desalting (2% aqueous acetonitrile solution with 0.1% formic acid, for 15 min). The desalted peptides were transferred to an Agilent Zorbax 300SB C18 analytical column (0.3 × 250 cm, 5 µm, flow rate of 5 uL/min) and separated over a gradient of 2–50% acetonitrile with 0.1% formic acid for 160 min. An ASI QuickSplit adjustable flow splitter (Richmond, CA, USA) was employed in the LC system between the pump and the T union (Figure 1) because the pump used in the system could not support a flow rate < 100 µL/min. Additionally, the use of the T-union connecting the adjustable splitter, the auto sampler, and the divert valve port, switched to the trap column or to the analytical column, allows non-disturbed flow through the analytical column and the ESI needle during on-line desalting without an additional pump (Figure 1). The eluent from the analytical column was directly introduced into an AB/SCIEX QTRAP MS/MS system (Foster City, CA, USA) through a turbospray source (AB/SCIEX, gas 1 at 14 psi and spray voltage of 4.5 kV). Data-dependent scan mode (the acquisition of MS/MS spectra of the four most intense ions in a survey scan (full MS scan or MRM), Figure 2) was used by Analyst v1.4.2 software (AB/SCIEX) for mass spectrometry. The acquired data were searched within the NCBInr protein database using the Mascot search engine (v. 2.2, Matrix Science, Boston, MA, USA) to identify peptides/proteins at a confidence interval ≥ 95% (Figure 2) and also verified manually. All analyses were carried out in triplicate. Three different kinds of target MRM transition candidates (transitions transferred from our previous nLC-MRM/MS method,19 transitions extracted from experimental observations previously reported18 and then confirmed by our LC-MS/MS runs, and transitions generated in silico) were tested by LC-MRM/MS of the CSF digest sample. Verified transitions (transitions successfully identified by LC-MRM/MS) were merged into the final LC-MRM/MS method, and the list of target biomarker candidates (including MRM transitions) and the internal standard included in the method are given in Table 1. The transitions were intended to measure alterations in specific peptides from a given protein believed to be diagnostic18 rather than alterations in intact proteins.

Figure 1.

Instrument configuration. An adjustable flow splitter was utilized to support the reduced mobile phase flow rate. Mobile phase flow through the analytical column and the electrospray ionization needle was maintained during the on-line desalting step without an additional liquid chromatography pump due to the T-union connecting the adjustable splitter, the auto sampler, and the divert valve port, which could be switched to the trap column or to the analytical column.

Figure 2.

Representative data acquisition/analysis results. Eluent delivered into a mass spectrometer was scanned in the full scan mode or the multiple reaction monitoring mode (overlay of chromatogram, A and an extracted ion chromatogram, B). MS2 spectra of the four most intense ions in a survey scan were acquired and peptide/protein identification was carried out through a database search of MS2 data acquired (C).

Table 1.

Summary of targets in the MRM assay based on LC-MS/MS.

| Target Codes | Targeted Proteins | Signature Peptides | Preca (m/z) |

Fragb (m/z) |

CEc (V) | RTd (min) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Albumin 1 | Albumin-1 | LVNEVTEFAK | 575.3 | 694.4 | 33.8 | 46 |

| Albumin 123 | Albumin-1/albumin-2/albumin-3 | AVMDDFAAFVEK | 671.8 | 171.1 | 38.6 | 93 |

| Albumin 3 (N) | Albumin-3 | EFNAETFTFHADTCTLSEK | 754.0 | 850.4 | 36.2 | 89 |

| a-1-antitrypsin 1 (N) | α-1-antitrypsin-1/ α-1-antitrypsin-2 |

TLNQPDSQLQLTTGNGLFLSEGLK | 858.8 | 963.5 | 40.8 | 98 |

| a-1-antitrypsin 2 | α-1-antitrypsin-2 | LSITGTYDLK | 555.8 | 201.1 | 32.8 | 55 |

| Apo E (N) | Apolipoprotein E | SWFEPLVEDMQR | 769.0 | 185.0 | 43.4 | 105 |

| Apo J 1 (N) | Apolipoprotein J-1 | ELDESLQVAER | 644.8 | 215.1 | 37.2 | 40 |

| Apo J 23 | Apolipoprotein J-2/ Apolipoprotein J-3 |

ASSIIDELFQDR | 697.3 | 922.4 | 39.9 | 106 |

| CC 3 | Complement component 3 | LVAYYTLIGASGQR | 756.4 | 902.5 | 42.8 | 75 |

| Fibrin b | Fibrin β | HQLYIDETVNSNIPTNLR | 709.7 | 827.5 | 34.2 | 63 |

| IG HC | Immunoglobulin heavy chain | NQVSLTCLVK | 581.3 | 820.5 | 34.1 | 56 |

| IG LC (N) | Immunoglobulin light chain | SGTASVVCLLNNFYPR | 899.4 | 923.5 | 50.0 | 112 |

| Plasminogen NT (N) | Plasminogen | WELCDIPR | 544.6 | 216.1 | 27.0 | 69 |

| Transthyretin 1 | Transthyretin-1 | TSESGELHGLTTEEEFVEGIYK | 819.1 | 189.1 | 39.0 | 90 |

| Transthyretin 12 (N) | Transthyretin-1/ Transthyretin-2 |

GSPAINVAVHVFR | 684.0 | 307.1 | 33.1 | 65 |

| VDBP (N) | Vitamin D-binding protein | VPTADLEDVLPLAEDITNILSK | 790.1 | 209.1 | 37.8 | 146 |

| CASA | Bovine α-casein (internal standard) | HQGLPQEVLNENLLR | 587.3 | 644.4 | 28.8 | 73 |

Precursor ion in a MRM transition;

Fragment ion in a MRM transition;

Collision energy for a MRM transition;

Retention time

Results and Discussion

Instrument configuration

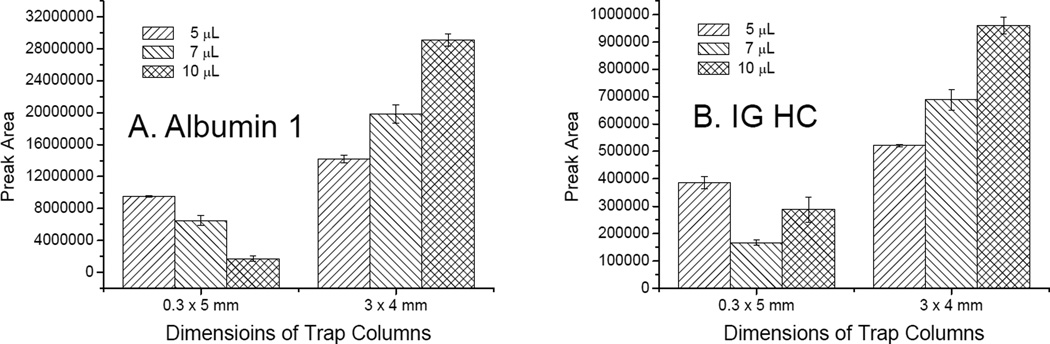

The previous MRM method targeting AD CSF biomarker candidates was based on nLC-MS/MS.19 To develop a method based on conventional LC-MS/MS, the flow rate through the analytical column was set at 5 µL/min and then a 0.3 mm ID column applicable at a flow rate of 5 µL/min was chosen as the analytical column. However, the LC pump used was not designed to reliably support a stable 5 µL/min flow; therefore, an adjustable flow splitter (Figure 1) was used. Additionally, to keep mobile phase flowing through the analytical column and the ESI needle during on-line desalting without employing another LC pump, the adjustable splitter, the auto sampler, and the diver valve port (which could be switched to the trap column or to the analytical column) were connected by a T-union (Figure 1). Because the mobile phase flow through the column and the needle was never disturbed during sample analyses, it stably maintained the chromatography and ionization environments. Two targets (albumin 1 and immunoglobulin heavy chain, IG HC) showed non-quantitative results from preliminary performance tests of three different volume injections (5, 7, and 10 µL) of the CSF digest sample (bars on left sides of Figure 3A and 3B). As the retention times of both peptides were relatively short (46 minutes for albumin 1 and 56 minutes for IG HC, Table 1), their retention in the trap column during sample injection and on-line desalting may have been an issue. To test this, the same volumes of the same sample were tested through a system in which the 0.3 × 5 mm trap column was replaced with a 3 × 4 mm guard column. As shown in the bars on the right sides of Figure 3A and 3B, the two targets showed quantitative responses. The reason for the unexpected responses of the two targets observed in the system remains unclear, but the capacity of the trap column may have been an issue. Thus, a new set up with a 3 × 4 mm trap column was employed for subsequent studies.

Figure 3.

Comparisons of different trap columns. Peak area values represent those of albumin 1 (A) and immunoglobulin heavy chain (IG HC) (B) from different volume (5, 7, and 10 µL) multiple reaction monitoring assays of the digested cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample (n = 3) using different trap columns (0.3 × 5 mm column and a 3 × 4 mm column).

Test of LC-MRM/MS performance

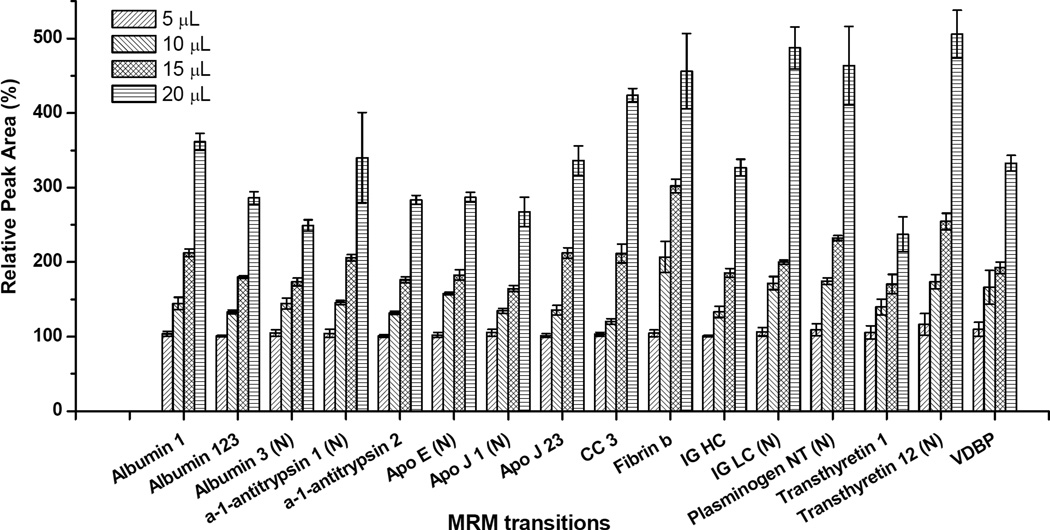

Sixteen targets were included in the final LC-MRM/MS method (Table 1). Four different volumes (5, 10, 15, and 20 µL) of the CSF digest sample were analyzed to evaluate the quantitative linearity and reproducibility of the method. Such an experiment makes it possible to measure different levels of all targets changing over a known amount.19 The resulting changes in peak areas for individual targets were measured, and all 16 MRM transitions showed good quantitative linearity and reproducibility (average R2 = 0.966 ± 0.030 and average CV = 4.78 ± 3.35%, Figure 4 and Table 2). The range of target peak areas was about four orders of magnitude in each analysis (data not shown). Additionally, we analyzed the same sample twice, separated by 4 days, to evaluate inter-day reproducibility of the method. As shown in Table 2, CV values of all transitions were < 20% (average CV = 9.85 ± 3.91%). Thus, we observed good reproducibility of the method even after changing the instrument set up.

Figure 4.

Relative peak areas of individual multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) targets from different volume (5, 10, 15, and 20 µL) MRM assays of the digested cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) sample (n = 3) using a 3 × 4 mm trap column

Table 2.

Comparisons between runs without internal standard and runs with an internal standard (a tryptic digest peptide (HQGLPQEVLNENLLR) from bovine α-casein)

| Targets | Runs without internal standard | Runs with internal standard | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R2 (NIS)a | Intra-day CV (NIS)b, (%) |

Inter-day CV (NIS)c, (%) |

R2 (IS)d | Intra-day CV (IS)e, (%) |

Inter-day CV (IS)f, (%) |

|

| Albumin 1 | 0.987 | 3.63±1.40 | 7.82 | 0.990 | 2.99±1.84 | 7.23 |

| Albumin 123 | 0.987 | 1.58±1.00 | 5.88 | 0.986 | 2.45±0.88 | 6.11 |

| Albumin 3 (N) | 0.958 | 3.83±0.98 | 7.59 | 0.963 | 4.91±3.79 | 8.72 |

| a-1-antitrypsin 1 (N) | 0.917 | 6.74±7.57 | 8.38 | 0.964 | 6.97±1.92 | 9.72 |

| a-1-antitrypsin 2 | 0.991 | 1.99±0.32 | 9.78 | 0.989 | 2.72±1.24 | 8.33 |

| Apo E (N) | 0.964 | 2.60±1.16 | 9.63 | 0.980 | 2.67±1.38 | 11.25 |

| Apo J 1 (N) | 0.978 | 4.17±2.34 | 4.68 | 0.978 | 2.78±1.54 | 6.86 |

| Apo J 23 | 0.967 | 4.13±1.56 | 7.31 | 0.986 | 4.02±2.16 | 7.72 |

| CC 3 | 0.991 | 3.48±1.70 | 8.83 | 0.892 | 5.12±1.89 | 8.28 |

| Fibrin b | 0.905 | 7.14±3.99 | 19.41 | 0.891 | 8.94±5.78 | 15.36 |

| IG HC | 0.993 | 3.25±1.91 | 15.19 | 0.972 | 3.87±2.92 | 13.38 |

| IG LC (N) | 0.978 | 4.43±1.99 | 14.39 | 0.970 | 9.35±7.14 | 16.94 |

| Plasminogen NT (N) | 0.971 | 5.66±4.60 | 6.45 | 0.976 | 3.31±1.22 | 4.91 |

| Transthyretin 1 | 0.907 | 8.37±1.04 | 9.90 | 0.868 | 7.66±1.99 | 11.21 |

| Transthyretin 12 (N) | 0.989 | 7.16±3.73 | 13.62 | 0.714 | 8.47±1.98 | 10.61 |

| VDBP | 0.967 | 7.37±4.79 | 8.81 | 0.923 | 6.89±3.76 | 11.56 |

| Average | 0.966 ±0.030 | 4.78±3.35 | 9.85±3.91 | 0.940 ±0.072 | 5.21±3.62 | 9.89±3.32 |

R2 value from different volume (5, 7, 10, and 20 µL) runs of the digested CSF sample without internal standard (n = 3)

Mean of individual CV values (%) within triplicate runs per each volume (5, 7, 10, and 20 µL) of the digested CSF sample without internal standard

CV value (%) from four day runs of the digested CSF sample without internal standard (7 µL, n = 3)

R2 value from runs of four digested CSF samples which differ only in bovine α-casein digest amount spiked (CSF-CASA 0.8, CSF-CASA 1.1, CSF-CASA 1.6 and CSF-CASA 3.2, 7 µL, n = 3)

Mean of individual CV values (%) within triplicate runs per each bovine α-casein digest-spiked CSF sample (CSF-CASA 0.8, CSF-CASA 1.1, CSF-CASA 1.6 and CSF-CASA 3.2, 7 µL, n = 3)

CV value (%) from four day runs of the bovine α-casein digest-spiked CSF digest sample (CSF-CASA 1.6, 7 µL, n = 3)

Performance test of the LC-MRM/MS method employing the internal standard

A tryptic peptide (HQGLPQEVLNENLLR) from CASA was used as the internal standard after spiking the CASA tryptic digest into the CSF digest sample to determine the need for an internal standard. Four CSF samples that differed only in the CASA digest amount (0.8 [CSF-CASA 0.8], 1.1 [CSF-CASA 1.1], 1.6 [CSF-CASA 1.6], and 3.2 µg [CSF-CASA 3.2] in each 200 µL of sample, respectively) were tested and inter-day reproducibility (4-day interval) of the method with the internal standard was also measured using the CSF-CASA 1.6 sample. Each target peak area was normalized by that of the internal standard, but normalization did not significantly improve quantitative linearity, intra-day reproducibility, or inter-day reproducibility (Table 2). Thus, we concluded that the present LC-MRM/MS method does not require the use of an internal standard.

Comparison of LC-MRM/MS with nLC-MRM/MS

The LC-MRM/MS method was compared with our previous nLC-MRM/MS method (Table 3).19 Due to the lower sensitivity of LC and ESI than that of nLC and nESI,25–27 a 30-fold higher concentration of sample was needed for LC-MRM/MS than that in nLC-MRM/MS. From tests using other diluted samples, a confirmed identity of some targets was not available (data not shown). Low sensitivity also affected the fewer targets included in the LC-MRM/MS method, but the difference was limited to two transitions (16 in the present method vs. 18 in the previous method). Despite the lower sensitivity, the LC-MRM/MS method has several advantages over the nLC-MRM/MS method. First, total analysis time of the present method was 160 minutes, compared to 200 minutes with the nLC method (two 100-minute runs/sample). Additionally, while some target peptides in the previous method had a possible issue with variability, such as non-specifically cleaved peptides and miss-cleaved peptides, all target peptides in the present method were free of the variability issue (Table 1). Last, the LCMRM/ MS method does not require an internal standard. Even without the internal standard, the LC-MRM/MS method showed no significant deficit in analytical performance compared with that of the nLC-MRM/MS method employing regional standards. An additional advantage is that the portion of MRM transitions that showed CV values < 10% in the present method was 91.4%. This was slightly larger than that of our previous nLC-MRM/MS method (89.6%)19 and much larger than that of Hunter and Anderson's nLC-MRM/MS study on non-depleted plasma (20–50%).28 Therefore, results from the present study support excellent analytical performance of the LC-MRM/MS method.

Table 3.

Comparisons of the present MRM assay based on LC-MS/MS with the previous MRM assay based on nLC-MS/MS [19]

| The previous MRM assay based on nLC-MS/MS [19] |

The present MRM assay based on LC-MS/MS |

|

|---|---|---|

| Relative concentration of a sample solutiona |

1 | 30 |

| The number of targets included in the assay |

18 | 16 |

| The total analysis time | 200 minutes (100 minutes/run×2 runs) |

160 minutes |

| Requirement of internal standards | Yes | No |

| Quantitative linearity (R2) | 0.933±0.018 | 0.966±0.030 |

| Intra-day reproducibility (CV %) | 6.93±5.48 | 4.78±3.35 |

| Inter-day reproducibility (CV %) | 8.01±3.21 | 9.85±3.91 |

| The portion of transitions which have CV<10% |

89.6% | 91.4% |

Relative concentration of a sample compared to the concentration of the sample used in the previous MRM assay based on nLC-MS/MS

Conclusions

An LC-MRM/MS method to monitor 16 peptides representing AD biomarker candidates from non-depleted human CSF was developed. The unique instrumental configuration available in most analytical laboratories and the MRM assay made it possible to obtain good analytical performance (quantitative linearity, intra-day reproducibility, and inter-day reproducibility). Additionally, the present method had several advantages, including a short analysis time, no possibility of target variability, and no need for an internal standard. Therefore, the method presented here has potential not only to facilitate validation of previously reported putative AD biomarker candidates but also to be a new diagnostic method for AD.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the National Institutes of Health (R01MH59926, 2P20RR016472, 5P30RR031160), the New York State Office of Science, Technology, and Academic Research, and the Institute for the Study of Aging for support of this work.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

None

References

- 1. [Accessed 30 June 2015];Alzheimer's Association. 2014 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures. 2015 http://www.alz.org/downloads/Facts_Figures_2014.pdf.

- 2.Doody RS, Stevens JC, Beck C, Dubinsky RM, Kaye JA, Gwyther L, Mohs RC, Thal LJ, Whitehouse PJ, DeKosky ST, Cummings JL. Practice parameter: management of dementia (an evidence-based review). Report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2001;56:1154–1166. doi: 10.1212/wnl.56.9.1154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gifford DR, Cummings JL. Evaluating dementia screening tests. Neurology. 1999;52:224–227. doi: 10.1212/wnl.52.2.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnold SE, Hyman BT, Flory J, Damaiso AR, Van Hoesen GW. The topographical and neuroanatomical distribution of neurofibrillary tangles and neuritic plaques in the cerebral cortex of patients with Alzheimer's disease. Cereb Cortex. 1991;1:103–116. doi: 10.1093/cercor/1.1.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rohlff C. Proteomics in molecular medicine: Applications in central nervous systems disorders. Electrophoresis. 2000;21:1227–1234. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1522-2683(20000401)21:6<1227::AID-ELPS1227>3.0.CO;2-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Davidsson P, Westman-Brinkmalm A, Nilsson CL, Lindbjer M, Paulson L, Andreasen N, Sjogren M, Blennow K. Proteome analysis of cerebrospinal fluid proteins in Alzheimer patients. Neuroreport. 2002;13:611–615. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200204160-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carrette O, Demalte I, Scherl A, Yalkinoglu O, Corthals G, Burkhard P, Hochstrasser DF, Sanchez JC. A panel of cerebrospinal fluid potential biomarkers for the diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease. Proteomics. 2003;3:1486–1494. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200300470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Romeo MJ, Espina V, Lowenthal M, Espina BH, Petricoin EF, Liotta LA. CSF proteome: a protein repository for potential biomarker identification. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2005;2:57–70. doi: 10.1586/14789450.2.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdi F, Quinn JF, Jankovic J, McIntosh M, Leverenz JB, Peskind E, Nixon R, Nutt J, Chung K, Zabetian C. Detection of biomarkers with a multiplex quantitative proteomic platform in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with neurodegenerative disorders. J Alzheimers Dis. 2006;9:293–348. doi: 10.3233/jad-2006-9309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu Y, Hosseini A, Kauwe JSK, Gross J, Cairns NJ, Goate AM, Fagan AM, Townsend RR, Holtzman DM. Identification and validation of novel CSF biomarkers for early stages of Alzheimer's disease. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2007;1:1373–1384. doi: 10.1002/prca.200600999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simonsen AH, McGuire J, Podust VN, Davies H, Minthon L, Skoog I, Andreasen N, Wallin A, Waldemar G, Blennow K. Identification of a novel panel of cerebrospinal fluid biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2008;29:961–968. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhang J, Sokal I, Peskind ER, Quinn JF, Jakovic J, Kenney C, Chung KA, Millard SP, Nutt JG, Montine TJ. CSF Multianalyte Profile Distinguishes Alzheimer and Parkinson Diseases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2008;129:526–529. doi: 10.1309/W01Y0B808EMEH12L. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mares J, Kanovsky P, Herzig R, Stejskal D, Vavrouskova J, Hlustik P, Vranova H, Burval S, Zapletalova J, Pidrman V, Obereigneru R, Suchy A, Vesely J, Podivinsky J, Urbanek K. The assessment of beta amyloid, tau protein and cystatin C in the cerebrospinal fluid: laboratory markers of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurol Sci. 2009;30:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s10072-008-0005-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Choi YS, Choe LH, Lee KH. Recent cerebrospinal fluid biomarker studies of Alzheimer's disease. Expert Rev Proteomics. 2010;7:919–929. doi: 10.1586/epr.10.75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pannee J, Portelius E, Oppermann M, Atkins A, Hornshaw M, Zegers I, Hojrup P, Minthon L, Hansson O, Zetterberg H, Blennow K, Gobom J. A selected reaction monitoring (SRM)-based method for absolute quantification of Aβ38, Aβ40, and Aβ42 in cerebrospinal fluid of Alzheimer’s disease patients and healthy controls. J Alzheimers Dis. 2013;33:1021–1032. doi: 10.3233/JAD-2012-121471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Struyfs H, Van Broeck B, Timmers M, Fransen E, Sleegers K, Van Broeckhoven C, De Deyn PP, Streffer JR, Mercken M, Engelborghs S. Diagnostic Accuracy of Cerebrospinal Fluid Amyloid-β Isoforms for Early and Differential Dementia Diagnosis. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45:813–822. doi: 10.3233/JAD-141986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leuzy A, Carter SF, Chiotis K, Almkvist O, Wall A, Nordberg A. Concordance and Diagnostic Accuracy of [11C]PIB PET and Cerebrospinal Fluid Biomarkers in a Sample of Patients with Mild Cognitive Impairment and Alzheimer's Disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2015;45:1077–1088. doi: 10.3233/JAD-142952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finehout EJ, Franck Z, Choe LH, Relkin N, Lee KH. Cerebrospinal fluid proteomic biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease. Ann Neurol. 2007;61:120–129. doi: 10.1002/ana.21038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi YS, Hou S, Choe LH, Lee KH. Targeted human cerebrospinal fluid proteomics for the validation of multiple Alzheimer's disease biomarker candidates. J Chromatogr B. 2013;930:129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noga M, Sucharski F, Suder P, Silberring J. A practical guide to nano-LC troubleshooting. J Sep Sci. 2007;30:2179–2189. doi: 10.1002/jssc.200700225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Eriksson J, Fenyo D. Improving the success rate of proteome analysis by modeling protein-abundance distributions and experimental designs. Nat Biotechnol. 2007;25:651–655. doi: 10.1038/nbt1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pan S, Rush J, Peskind ER, Galasko D, Chung K, Quinn J, Jankovic J, Leverenz JB, Zabetian C, Pan C, Wang Y, Oh JH, Gao J, Zhang J, Montine T, Zhang J. Application of targeted quantitative proteomics analysis in human cerebrospinal fluid using a liquid chromatography matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight tandem mass spectrometer (LC MALDI TOF/TOF) platform. J Proteome Res. 2008;7:720–730. doi: 10.1021/pr700630x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pes O, Preisler J. Off-line coupling of microcolumn separations to desorption mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr A. 2010;1217:3966–3977. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2010.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tao D, Xhu G, Sun L, Ma J, Liang Z, Zhang W, Zhang L, Zhang Y. Serially coupled microcolumn reversed phase liquid chromatography for shotgun proteomic analysis. Proteomics. 2009;9:2029–2036. doi: 10.1002/pmic.200800649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilm M, Mann M. Analytical properties of the nanoelectrospray ion source. Anal Chem. 1996;68:1–8. doi: 10.1021/ac9509519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Choi YS, Wood TD. Polyanilin-coated nanoelectrospray emitters treated with hydrophobic polymers at the tip. Rapid Commun Mass Spectrom. 2007;21:2101–2108. doi: 10.1002/rcm.3068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aguilar MI. HPLC of Peptides and Proteins: Methods and Protocols. Totowa, NJ: Humana Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Anderson L, Hunter CL. Quantitative mass spectrometric multiple reaction monitoring assays for major plasma proteins. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:573–588. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500331-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]