Abstract

Bacteria of the genus Myroides (Myroides spp.) are rare opportunistic pathogens. Myroides sp. infections have been reported mainly in China. Myroides sp. is highly resistant to most available antibiotics, but the resistance mechanisms are not fully elucidated. Current strain identification methods based on biochemical traits are unable to identify strains accurately at the species level. While 16S ribosomal RNA (rRNA) gene sequencing can accurately achieve this, it fails to give information on the status and mechanisms of antibiotic resistance, because the 16S rRNA sequence contains no information on resistance genes, resistance islands or enzymes. We hypothesized that obtaining the whole genome sequence of Myroides sp., using next generation sequencing methods, would help to clarify the mechanisms of pathogenesis and antibiotic resistance, and guide antibiotic selection to treat Myroides sp. infections. As Myroides sp. can survive in hospitals and the environment, there is a risk of nosocomial infections and pandemics. For better management of Myroides sp. infections, it is imperative to apply next generation sequencing technologies to clarify the antibiotic resistance mechanisms in these bacteria.

Keywords: Myroides sp., Antibiotic resistance, Identification methods, 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing, Next generation sequencing

1. Introduction

The genus Myroides (Myroides spp.) comprises yellow-pigmented, non-motile, Gram-negative, rod-like bacteria (Holmes et al., 1977; Cho et al., 2011) that release a fruity odor during growth (Holmes et al., 1977). The first strain, Stutzer, of the genus Myroides was isolated from the stools of patients with intestinal infections (Holmes et al., 1977) and was assigned the species name Flavobacterium odoratum (Stutzer and Kwaschnina, 1929). For easier clinical recognition, the bacteriological features, pigmentation, biochemical characteristics, and antimicrobial profiles of 10 isolates were examined (Holmes et al., 1977). Myroides spp. were found to be non-fermentative organisms resistant to many antibiotics (Holmes et al., 1977). In 1996, after extensive polyphasic taxonomic analysis of 19 strains of F. odoratum, the genus Myroides was established and included two species, M. odoratus and M. odoratimimus (Vancanneyt et al., 1996). Later, more strains were isolated from forest soil (strain TH-19(T), named M. xuanwuensis sp. nov. (Zhang et al., 2014)), seawater (strain JS-08(T), named M. marinus sp. nov. (Cho et al., 2011), strain SM1(T), named M. pelagicus sp. nov. (Yoon et al., 2006)), deep-sea sediment (strain D25T (Zhang et al., 2008)), human saliva (strain MY15T, named M. phaeus sp. nov. (Yan et al., 2012)), as well as strains from urine, sputum, surgical exudate (Andreoni, 1986), and patients’ matter (Table 1). Thus, Myroides spp. are widely distributed in nature (Mammeri et al., 2002; Ktari et al., 2012; Suganthi et al., 2013; Ravindran et al., 2015).

Table 1.

Summary of reported infections by Myroides sp.

| Patient No. | Age (year)/gender | Underlying diseases or reasons | Site of isolation | Antibiotic resistance status | Treatment strategy | Outcome | Reference |

| 1 | 87/M | Trauma, old age | Wound | Resistant to all antibiotics except ciprofloxacin. Sensitive to trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | iv ciprofloxad | Favorable | Sun and Zhang, 2006 |

| 2 | 34/F | Hydatid cyst of liver | Drainage | Resistant to neomycin, streptomycin, gentamicin, ampicillin, tobramycin. Sensitive to norfloxacin | Norfloxacin | Favorable | An, 1992 |

| 3 | 2/M | Young age | CSF | Resistant to cefazolin, penicillin, chloramphenicol. Sensitive to ampicillin, polymyxin, kanamycin, erythromycin, neomycin | ND | ND | Shi and Zhou, 1993 |

| 4 | 71/M | Chronic bronchitis, old age | Sputum | Resistant to meropenem, imipenem, ampicillin, cefradine, tobramycin, cephalothin, amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, ampicillin-shubatan, ceftriaxone, gentamicin, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, piperacillin. Sensitive to cefepime, levofloxacin | ND | ND | Guo and Liu, 2011 |

| 5 | 30/F | Burn | Blood, central venous catheter, urine | Sensitive to amikcin, norfloxacin | Amikacin | Favorable | Wu, 1998 |

| 6 | 28/F | Injury and surgery | Wound | Resistant to gentamicin, sulfamethoxazole, ciprofloxacin, cefoperazone-sulbactam, tetracycline, tobramycin, cefoperazone, cefepime, imipenem, piperacillin-tazobactam, cefoselis, amikacin, piperacillin, levofloxacin, netilmicin, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, aztreonam, ampicillin-sulbactam. Sensitive to minocycline. Moderately sensitive to meropenem | Debridement, skin transplantation, iv cefperazone-sulbactam and oral minocycline for 3 d, then oral minocycline for another 3 d | Cured | Hu et al., 2013 |

| 7 | 76/M | Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and heart failure, old age | Blood, wound | Resistant to piperacillin, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefepime, aztreonam, imipenem, meropenem, amikacin, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, ampicillin-sulbactam, cefoperazone-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam | Oral minocycline for 9 d | Cured | Huang et al., 2014 |

| 8 | 4/M | None | Blood | Resistant to ampicillin, ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin, piperacillin tazobactam, aztreonam, cefazolin, cefoxitin, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, azole cefepime, ceftazidime, ceftriaxone, cefepime | Piperacillin and tobramycin for 14 d | Cured | Huang and Lin, 2003 |

| 9 | 58/ND | Diabetes mellitus complicated by heel bursitis | Drainage | Sensitive to cefoperazone and amikacin | Incision and drainage, cefoperazone and amikacin for several days (more than 3 d) | Cured | Yang and Wang, 2001 |

| 10 | 28/F | None | Pus | Resistant to kanamycin, penicillin, erythromycin. Sensitive to ceftriaxone, norfloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Abscess incision drainage and norfloxacin and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Cured | Song et al., 1995 |

| 11 | 24 d/M | Neonate | Blood | Resistant to penicillin, chloramphenicol, carbenicillin, streptomycin, cefazolin. Sensitive to amikacin, erythromycin, ampicillin, benzylpencilline | Ampicillin, and oxacillin for 19 d | Cured | Wang and Su, 1992 |

| 12 | 11 d/M | Preterm birth | Blood, CSF | Resistant to ampicillin, cefazolin, gentamicin, cefoperazone, cefotaxime, cefatrizine, ceftazidime. Sensitive to amikacin, piperacillin, ampicillin, sulbactam-cefoperazone | Antimicrobial treatment for 5 d (the antibiotic was not described) | Failed | Zhang and Zhang, 1996 |

| 13 | 69/F | Lung cancer and surgery, old age | Pleural effusion and sputum | Resistant to tobramycin, gentamicin, ampicillin, erythromycin, clindamycin, tetracycline. Sensitive to amikacin, tobramycin, ceftriaxone | Antimicrobial treatment, but not described in detail | Died | Song, 2005 |

| 14 | 10 months/F | Child | Blood | Sensitive gentamicin, tobramycin, cephalexin, sulbactam-cefoperazone, ceftriaxone | Cefoperazone, tobramycin for 10 d | Cured | Zhao, 2000 |

| 15 | 60/M | Common bile duct stones | Blood, bile, peritoneal effusion | Resistant to tobramycin. Sensitive to piperacillin, cefoperazone, amikacin, gentamicin, ceftriaxone, cefotaxime | Amikacin and cefoperazone | Cured | Meng et al., 1999 |

| 16 | 44/F | None | Blood, bone marrow | Sensitive to norfloxacin, ciprofloxacin, cefazolin, amikacin, ceftazidime | ND | ND | Geng et al., 2000 |

| 17 | 67/M | Old age | Sputum (this strain was isolated with Serratia marcescens, Acinetobacter lwoffi) | Resistant to ampicillin, piperacillin cefazolin, cefuroxime, cefotaxime, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, aztreonam, gentamicin, norfloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | Antimicrobial treatment, but not described in detail | Cured | Liu and He, 2001 |

| 18 | 45/M | None | Urine | Resistant to ampicillin, amikacin, azithromycin | Application of cefoperazone, cefotaxime, nitrofurantoin, and tobramycin for 3 weeks | Cured | Wuer et al., 2000 |

| 19 | N/A | ND | Blood, sputum, bile, cerebrospinal fluid, urine, all these three isolates were from patients (no further details were available) | All 12 isolates were resistant to erythromycin, penicillin, streptomycin, ampicillin, oxacillin, piperacillin, carbenicillin | N/A | N/A | Li and Zhao, 1995 |

| 20 | ND | Chronic nephritis | Urine | Two isolates were resistant to meropenem. All three isolates were resistant to ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, cefuroxime, cefotetan, ceftriaxone, aztreonam, gentamicin, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, ampicillin, piperacillin, cefazolin, cefuroxime axetil, ceftazidime, cefepime, imipenem, amikacin, tobramycin, levofloxacin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole | One isolate was sensitive to meropenem | ND | Li et al., 2010 |

| 21 | ND | Diabetes mellitus | |||||

| 22 | ND/F | Cervical cancer | |||||

| 23 | 61/F | Coma, cerebral hemorrhage | Sputum | N/A | Ceftazidine, chloramphenicol, penicillin G, gentamicin by atomization inhalation, ketoconazole by nasal feeding | Died | Jin and Xiao, 1995 |

| 24 | 49/M | Chronic alcohol misuse | Blood | Intermediately sensitive to imipenem | Treatment with amoxicillin-clavulanic acid was changed to ciprofloxacin, imipenem-cilastatin used for 10 d, then oral ciprofloxacin for 21 d | Cured | Bachmeyer et al., 2007 |

| 25 | 55/F | Liver cirrhosis bilateral lower extremity cellulitis and open wounds | Blood, wound | Resistant to amikacin, gentamicin, tobramycin, aztreonam, ceftriaxone, ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, vancomycin. Intermediately sensitive to piperacillin-tazobactam, cefepime, imipenem, and cilastatin | iv vancomycin, piperacillin-tazobactam, and levofloxacin for 18 h, then iv imipenem-cilastatin, daptomycin, clindamycin, then imipenem-cilastatin and doxycycline | Died | Crum-Cianflone et al., 2014 |

| 26 | 13/M | Soft tissue infection | Pus | Resistant to piperacillin-tazobactam, aztreonamaminoglycosides. Intermediately susceptible to imipenem. Sensitive to all quinolones tested, cotrimoxazole, chloramphenicol, and amoxicillin-clavulanic acid | Drainage of osteolytic lesions combined with iv ciprofloxacin for 10 d and continued with oral ciprofloxacin for an additional 10 d | Cured | Maraki et al., 2012 |

| 27 | 48/F | Cystitis (contaminated) | Urine | Fully resistant to streptomycin, gentamicin, kanamycin, ampicillin, carbenicillin, tetracycline, polymyxin B. Fully resistant or moderately resistant to sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, cephaloridine, erythromycin, chloramphenicol. Moderately sensitive to nalidixic acid | N/A | N/A | Holmes et al., 1977 |

| 28 | 34/M | Infected cut finger | Wound | ||||

| 29 | 59/F | ND | Urine | ||||

| 30 | ND/ND | Urinary retention | Urine | ||||

| 31 | ND/ND | Further details are not available | Urine | ||||

| 32 | ND/ND | Varicose ulcer | Wound | ||||

| 33 | 76/F | Leg ulcer | Ulcer | ||||

| 34 | 67/F | Breast lump | Urine | ||||

| 35 | 48/M | Chronic renal insufficiency | Urine | ||||

| 36 | 66/M | Urinary tract infection | Urine | Resistant to all β-lactam and non-β-lactam antibiotics tested, including imipenem, vancomycin, ciprofloxacin, chloramphenicol, tigecycline, rifampicin | Imipenem, colistin | Failure | Ktari et al., 2012 |

| 37 | 44/M | Bladder colonization | Urine | No treatment | Favorable | ||

| 38 | 44/M | Urine | No treatment | Favorable | |||

| 39 | 47/M | Urine | No treatment | Favorable | |||

| 40 | 77/M | Urinary tract infection | Urine | Ifampicinþ ciprofloxacin | Cured | ||

| 41 | 65/M | Urine | Ifampicinþ ciprofloxacin | Cured | |||

| 42 | 80/M | Urine | Ifampicinþ ciprofloxacin | Cured | |||

| 43 | 59/M | Urinary tract infection | Urine | Resistant to amikacin, gentamicin, imipenem, meropenem, cefazolin, ceftazidime, cefotaxime, cefepime, aztreonam, ampicilllin, piperacillin, amoxicillin-clavulanate, ampicillin-sulbactam, piperacillin-tazobactam, colistin, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, chloramphenicol, ciprofloxacin, levofloxacin, moxifloxacin, tetracycline | Levofloxacin was used only temporarily and orally | Failure | Our case |

M: male; F: female; N/A: not applicable; ND: not described; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; iv: intravenous injection

Myroides sp. is a rare opportunistic pathogen (Schröttner et al., 2014). Nevertheless, management of Myroides sp. infection is troublesome due to its high resistance to most antibiotics (as summarized in Table 1). For accurate strain identification of Myroides sp., current diagnostic methods, such as the Vitek Jr. system (Vitek Systems, bioMerieux) (Spanik et al., 1998), are based on bacteriological and biochemical characteristics, and can determine Myroides sp. at the species level in most cases. However, they and 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequencing (16S rRNA sequencing), a standardized bacterial strain identification method (Yoon et al., 2006; Zhang X.Y. et al., 2008; Zhang Z.D. et al., 2014) still not widely applied in Chinese hospitals, fail to provide any information on the status and mechanisms of antibiotic resistance in Myroides sp. Whole genome sequencing technologies could address these questions, and should be applied to Myroides sp. promptly.

2. Antibiotic resistance status of clinical Myroides sp. infections

Myroides sp. infections are rare. By searching the PubMed database of English literature using “Myroides” or “Flavobacterium odoratum” as key words, only a few reports could be found. In immunocompetent people, primary infections by Myroides sp. have been rarely reported, such as a case of M. odoratimimus cellulitis resulting from a pig bite in an immunocompetent child (Maraki et al., 2012). However, secondary infections can frequently arise when human immunity is impaired, such as post catheterization (Holmes et al., 1977; Spanik et al., 1998), in patients with cancer (Holmes et al., 1977; Spanik et al., 1998; Song, 2005) or diabetes mellitus (Yang and Wang, 2001), and in neonates (Wang and Su, 1992; Zhang and Zhang, 1996; Zhao, 2000). Myroides sp. can cause soft tissue infection (Benedetti et al., 2011), cellulitis (Bachmeyer et al., 2007), necrotizing fasciitis (Crum-Cianflone et al., 2014), ventriculitis (Macfarlane et al., 1985), and urinary tract infections (Yağci et al., 2000). M. odoratimimus even caused an outbreak of urinary tract infection in a hospital (Ktari et al., 2012).

By using the same key words to search the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) database, we found that most reports of Myroides or F. odoratum infections contained a single case (Table 1). Two papers reported 23 (Table 2) and 11 strains (Table 3), respectively.

Table 2.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of 23 strains of Myroides sp. using the K-B method

| Site of isolation (total samples of positive isolation) | Antibiotic | R | I | S |

| Sputum (8); | Amikacin | 5 | 10 | 8 |

| Urine (6) | Cefazolin | 11 | 9 | 3 |

| Blood (4); | Cefoperazone | 9 | 9 | 5 |

| CSF (3); | Sulfamethoxazole | 4 | 10 | 9 |

| Bile (2) | Sulfadiazine | 5 | 7 | 11 |

| Ceftazidime | 10 | 6 | 7 | |

| Erythrocin | 3 | 10 | 10 | |

| Azithromycin | 4 | 9 | 10 |

Translated from Lan and Bao (2009) with permission of the authors. K-B method: Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method; CSF: cerebrospinal fluid; R: resistant; I: immediately sensitive; S: sensitive

Table 3.

Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of 11 strains of Myroides sp. isolated from urine using Oxoid culture medium

| Patient information | Antibiotic | R | I | S |

| 2–76 years (average 53 years), 9 males, 2 females. All patients suffered from urinary retention or urinary tract stones, but none of them had symptoms of urinary tract infection or other discomfort. In nine urinarily catheterized patients, the urinary culture when the catheter was in situ was Myroides sp. positive, but the urinary testing showed no WBC in these urinary samples, and pus cells were found in only three of them. The urinary culture of Myroides sp. became negative after removal of urinary catheter in these nine urinarily catheterized patients even though they were not treated. | Ampicillin | 11 | 0 | 0 |

| Piperacillin | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cefuroxime | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Cefoperazone-sulbactam | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ceftazidine | 10 | 1 | 0 | |

| Cefepime | 10 | 1 | 0 | |

| Aztreonam | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Imipenem | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Meropenem | 11 | 0 | 0 | |

| Levofloxacin | 8 | 3 | 0 | |

| Ciprofloxacin | 9 | 2 | 0 | |

| Trimethoprim-sulphamethoxazole | 0 | 0 | 11 | |

| Amikacin | 11 | 0 | 0 |

Translated from Chen et al. (2009) with permission of Chin. J. Pract. Med. Tech. R: resistant; I: immediately sensitive; S: sensitive; WBC: white blood cell

From Tables 1, 2, and 3, we conclude that Myroides spp. are resistant to broad antibiotics, and that their extensive antibiotic resistance has resulted in treatment failure and fatalities. We observed a case in July 2009 in which a patient presented with a post-injury urinary tract infection caused by M. odoratimimus strain PR63039 (Table 1, our case). Using antibiotic sensitivity testing (AST), the strain was found to be resistant to ampicillin, amoxicillin, clavulanate, amikacin, aztreonam, chloramphenicol, cephalosporin, imipenem, gentamycin, levofloxacin, meropenem, shubatan, sulfamethoxazole, tetracycline, ciprofloxacin, and tazobactam. Even though many antibiotics, such as cefazolin oxime, amikacin, tetracycline, moxifloxacin, ciprofloxacin, and nitrofurantoin, were administered to the patient for 47 d, the infection was not cured.

The reports analyzed in Table 1 reveal that the antibiotic resistance of Myroides sp. varies among strains isolated from different sources. For example, a strain from a patient suffering from a hydatid cyst of the liver was sensitive to norfloxacin (An, 1992), but another strain isolated from pulmonary infection patient was reported to be resistant to norfloxacin (Liu and He, 2001). Two strains isolated from patients with cellulitis and a leg amputation, respectively (Hu et al., 2013; Crum-Cianflone et al., 2014) were resistant to ciprofloxacin, while another two isolated from trauma and septicemia patients, respectively, were sensitive to ciprofloxacin (Geng et al., 2000; Sun and Zhang, 2006).

Why is there so much variation in the antibiotic resistance profiles of Myroides sp. strains isolated from different sources In our opinion, the subtypes and genotypes of Myroides sp. might have a great influence on their sensitivity to certain antibiotics. Therefore, it is imperative to obtain accurate information on strain subtype and genotype.

3. Preliminary opinions on the antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Myroides sp.

In China, there have been no reports on the antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Myroides sp. Although several foreign researchers have investigated this topic, very little information is available. Hummel et al. (2007) showed that the β-lactamase gene was responsible for the variable patterns of resistance to β-lactam antibiotics and the decreased susceptibility to carbapenems of different Myroides sp. strains. In a study investigating a number of clinical cases involving systemic infections, Mammeri et al. (2002) claimed that resistance to β-lactams was due to the production of the chromosome-encoded β-lactamases TUS-1 and MUS-1 in M. odoratus and M. odoratimimus. The β-lactamases produced by Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria play a vital role in resistance against β-lactam antibiotics. However, their study showed that the β-lactamases TUS-1 and MUS-1 could only partly explain the intrinsic resistance of Flavobacteriaceae species to β-lactams. Also, a common observation was that these Escherichia coli expressed metalloenzymes were much less resistant to β-lactam than those of primitive origin (Mammeri et al., 2002). Even Flavobacteriaceae and Myroides sp. belong to the same family, the mechanism of resistance conferred by TUS-1 and MUS-1 in Flavobacteriaceae species cannot be assumed to operate in Myroides sp. Then, why does Flavobacteriaceae serve as a source for a variety of metalloenzymes As observed for other environmental species, this might be due to the combined biosynthesis of carbapenem derivatives and hydrolyzing β-lactamases (Mammeri et al., 2002).

Suganthi et al. (2013) investigated whether the antibiotic sensitivity of plasmid-containing M. odoratimimus SKS05-GRD was correlated with the plasmid or was chromosomally-mediated. They revealed that resistance to kanamycin, amikacin, and gentamicin was plasmid-mediated, and that resistance to ampicillin, cefadroxil, cefoperazone, ceftazidine, ceftriaxone, and netillin was chromosomally-mediated. The Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) family is closely related to resistance to carbapenem in a variety of pathogens and the KPC gene is located in a plasmid. However, Myroides sp. WX2856, obtained from an abdominal abscess (Kuai et al., 2011), harbored a KPC-2 carbapenemase, but the KPC-2 gene might not be located on a plasmid as in K. pneumoniae. Do these results suggest the possibility of interspecies transmission of the KPC-2 gene This aspect needs further investigation.

On the other hand, there are several known features of antibiotic resistance mechanisms in bacteria from the same family of Myroides, such as in F. indologenes, now named Chryserobacterium indologenes (Tian and Wang, 2010). First, resistance transfer factors (R-factors) in the cytoplasm determine the bacteria’s resistance to antibiotics. R-factor plasmids can carry and transfer a variety of resistance genes among bacteria. In addition, the thick outer membrane and its low permeability, resulting from multidirectional mutations, and the active discharge system of the bacterial cell membrane of C. indologenes confer inherent multi-drug resistance. The bacteria also produce a β-lactamase with a broad spectrum of β-lactam hydrolytic activity (Tian and Wang, 2010).

Thus, it is apparent that the antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Myroides sp. are unclear and deserve further investigation.

4. Present diagnostic methods do not clarify the antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Myroides sp.

In clinical diagnostic laboratories, traditional bacterial identification methods primarily rely on testing biological traits and biochemical characteristics, and include microscopic inspection and metabolic testing of isolated and cultured bacteria. These methods have shown that Myroides spp. do not have flagella, release a fruity fragrance, are yellow, oxidase-positive, urea- and indole-negative, and are unable to oxidize sugar (Li and Zhao, 1995; Chen et al., 2009). However, the bacterial strain can be preliminarily identified only as Myroides sp., as further strain type designations cannot be determined using these traditional methods. Nearly all cases of Myroides sp. infections reported in China have used these traditional identification approaches, and did not describe any Myroides sp. subtypes. Using these traditional identification methods, the M. odoratimimus strain PR63039 isolated in our case was first identified as Pseudomonas putida, then as M. odoratimimus, and as the Acinetobacter calcoaceticus-baumannii complex, at different time points throughout the 47 d of the patient’s hospitalization. It was finally confirmed as M. odoratimimus by 16S rRNA sequencing. This case also indicates that these traditional identification methods may not correctly diagnose the strain type.

Recently, other microorganism strain identification technologies have been developed, including VITEK 2 (bioMerieux VITEK-2, France), matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS), 16S rDNA sequencing, and another more frequently used nomenclature, 16S rRNA sequencing (Table 4). VITEK 2, a routine laboratory method, can help to discriminate among genera but not among species. MALDI-TOF MS and 16S rDNA sequencing/16S rRNA sequencing can be used to identify species and are more frequently used for research purposes (Lee et al., 2014; Schröttner et al., 2014). According to Schröttner et al. (2014), the genus Myroides was reliably identified in tests of 22 isolates using VITEK 2. 16S rDNA sequencing further revealed that they shared ≥97% homology, enough for a reliable identification at the species level. Yoon et al. (2006) applied 16S rRNA sequencing successfully to clarify the phylogenetic position of Myroides sp. strain SM1T, isolated from seawater in Thailand.

Table 4.

Comparison of the present approaches for strain identification of Myroides sp.*

| Method | Trait |

| VITEK2 | Only suitable to identify bacteria at the genus level, not at the species level |

| MALDI-TOF MS | Able to distinguish between M. odoratus and M. odoratimimus |

| 16S rDNA sequencing/16S rRNA sequencing | Able to distinguish microorganisms at the species level |

| Whole genome sequencing | Able to identify the microorganism and provide the bioinformatics of microorganism |

5. Whole genome sequencing is a feasible way to investigate the antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Myroides sp.

In the past decade, many next generation sequencing platforms have been developed, such as 454 invented in 2004 (Margulies et al., 2005), Illumina Solexa in 2006 (Bentley, 2006), SOLiD in 2007 (Chi, 2008), Ion Torrent in 2011 (Rothberg et al., 2011), and PacBio in 2012 (Koren et al., 2012). This has led to a rapid increase in the sequencing of whole genomes of microorganisms, including eukarya, bacteria, archaea, and viruses. These sequences have been deposited in the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) RefSeq genome collection database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genome) (Tatusova et al., 2015). In 2014, over 10 000 microbial genomes were released (Tatusova et al., 2015). Along with the next generation platforms, whole-genome analysis of multi-drug resistance mechanisms has emerged.

For example, A. baumannii is a common cause of fatal nosocomial infections because of its extensive antibiotic resistance. Genomic sequencing revealed comprehensive drug-resistance mechanisms, such as a 41.6-kb closely related antibiotic resistance island in the chromosome (Huang et al., 2012), the horizontally transmittable carbapenem resistance gene (bla OXA-23) containing a plasmid (in isolate MDR-TJ, with 454 Titanium) among different A. baumannii strains (Huang et al., 2012; Lee et al., 2013), a list of antimicrobial resistance-associated genes (with 454 and SOLiD) (Rolain et al., 2013), a diversified resistance gene list (with Illumina Hiseq2000) (Tan et al., 2013), and longitudinally evolved antibiotic resistance gene mutations and mutational pathways under pressure from the antibiotic colistin (with 454 Titanium) (Snitkin et al., 2013). Since its invention by Rothberg et al. (2011), Ion Torrent sequencing technology has been successfully applied to complete genomic sequencing, such as in Clostridium sp. BL8 (with Ion Torrent PGM™) (Marathe et al., 2014), and clear characterization of drug-resistant genes, such as in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Daum et al., 2014). Results can be obtained within five days, comparable to the turnaround time required by current drug sensitivity testing (DST) (Daum et al., 2014). PacBio single-molecule real-time technology has frequently been used to perform whole-genome sequencing of many microorganisms, such as Neisseria gonorrhea (with the PacBio RSII platform), a Gram-negative β proteobacterium responsible for the sexually transmitted infection gonorrhea (Abrams et al., 2015).

Yet, little genomic information about Myroides sp. is available. A brief description of the genomes of M. odoratus DSM 2801 and CIP 103059 was found in genome database of NCBI (Table 5), but this was not suitable for studying its drug-resistance mechanisms. Recently, the genome sequencing of the urethral catheter isolate Myroides sp. A21 was completed (Burghartz et al., 2015). The sequence contained 3650 protein-coding sequences (CDSs), 136 RNA-coding genes, and eight copies of the rRNA gene cluster, of which three were resolved as a direct repeat of two rRNA gene clusters. The presence of 106 transfer RNAs (tRNAs) and six noncoding RNAs (ncRNAs) was also predicted. By comparing the genome sequence of Myroides sp. A21 with those of M. odoratimimus CCUG 10230 and M. odoratus DSM 2801, 293 unique CDSs were found in the A21 genome (Burghartz et al., 2015). In addition, five genomic islands were predicted by Island Viewer analysis (Burghartz et al., 2015). However, as the antibiotic treatment history was not described and the antibiotic resistance status of this strain was not given, the antibiotic resistance mechanisms could not be analyzed from the data.

Table 5.

Reported RefSeq genome of Myroides odoratus CIP 103059 and DSM 2801

| Strain | Name | RefSeq | INSDC | Size (Mb) | Total number of genes | Total number of proteins | rRNA | tRNA | Other genes | GC content (%) | Pseudogenes |

| CIP 103059 | Master WGS | NZ_AGZJ00000000.1 | AGZJ00000000.1 | 4.23 | 3773 | 3631 | 10 | 67 | 1 | 35.8 | 64 |

| DSM 2801 | NZ_CM001437.1 | CM001437.1 | 4.3 | 3838 | 3695 | 9 | 74 | 1 | 35.8 | 59 |

Cited from GenBank assembly accession: GCA_000243275.1 and GCA_000297875.1. INSDC: International Nucleotide Sequence Database Collaboration

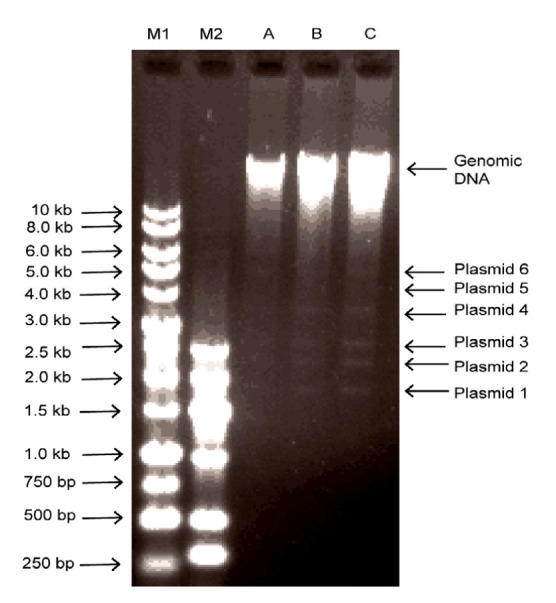

To study these aspects in our M. odoratimimus strain PR63039, we extracted its genomic DNA. Agarose gel electrophoresis results from several experiments revealed that it might harbor at least six different types of plasmids which could be related to antibiotic resistance (Fig. 1). However, the exact number of plasmid type needs further confirmation. Many bacterial drug-resistance genes are plasmid- or chromosome-mediated, but we did not know which mechanism was operating in Myroides sp. The genome of strain PR63039 was sequenced using an Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine. We generated 610 contigs and 4221 open reading frames. The total sequence numbers with Gene Ontology (GO) and Clusters of Orthologous Groups (COG) of protein were 2741 and 1026, respectively. However, we could not completely assemble the genome and plasmids, so the multi-drug resistance mechanisms of strain PR63039 still could not be clarified. We are now using PacBio single-molecule real-time technology in the hope of generating a complete genome sequence of both the chromosome and plasmids, to elucidate the mechanisms of resistance and pathogenesis of this strain.

Fig. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of genomic DNA of Myroides odoratimimus strain PR63039

The genomic DNA of PR63039 was separated by gel electrophoresis using 0.75% (7.5 g/ml) agarose. The genomic DNA was about 23 kb in size. M1: 1 kb DNA marker; M2: DNA marker-G; A: 0.173 μg DNA; B: 0.273 μg DNA; C: 0.328 μg DNA. The genomic DNA was about 23 kb in size. Six different types of plasmids (1–6) were visible

All the infection reports from China indicated that Myroides sp. is a serious source of nosocomial infection and has the potential to cause a pandemic. The completion of the Myroides sp. genome sequence and detailed bioinformatics analysis are imperative for the understanding of its mechanisms of antibiotic resistance and pathogenesis.

6. Discussion and outlook

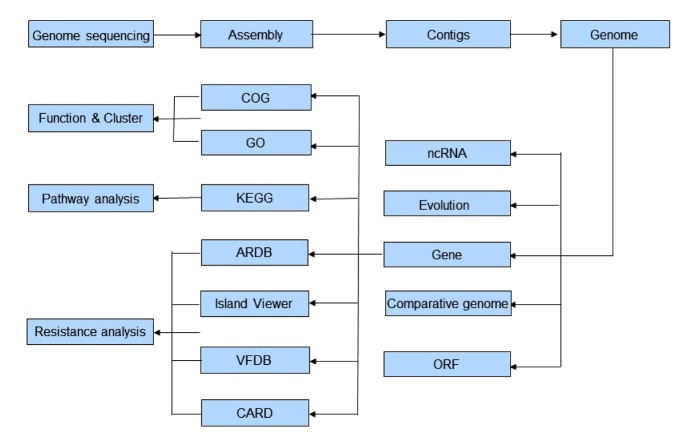

Myroides sp. is an opportunistic and extensively antibiotic-resistant pathogen. Infections have not been widely reported, though there have been many cases in China. As the antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Myroides sp. are still unclear, and in view of the risk of nosocomial infection and pandemics, novel technologies, such as whole genome sequencing and further bioinformatic analyses, should be applied urgently to Myroides sp. An outline of a strategy for whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic analyses is presented in Fig. 2. These analyses will also be helpful in developing appropriate management strategies. Moreover, whole genome sequencing might become a routine diagnosis method for all microbial infections in the near future.

Fig. 2.

Procedure of the strategy of whole genome sequencing and bioinformatics analyses

COG: Clusters of Orthologous Group; GO: Gene Ontology; KEGG: kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genome; ARDB: Antibiotic Resistance Genes Database; VFDB: Virulence Factor Database; CARD: Comprehensive Antibiotic Research Database; ncRNA: noncoding RNA; ORF: open reading frame

Footnotes

Project supported by the Huaqiao University Graduate Student Scientific Research Innovation Ability Cultivation Plan Projects, the Major Program of Department of Science and Technology of Fujian Province (No. 2012Y4009), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Xiamen (No. 3502Z20123036), the Xiamen Southern Oceanographic Center (No. 14GYY008NF08), the Construction Project for Yun Leung Laboratory for Molecular Diagnostics (No. 14X30127), the Technology Planning Projects of Quanzhou Social Development Fields (No. 2014Z24), and the Major Support Research Project of National Key Colleges Construction of Quanzhou Medical College (No. 2013A13), China

Compliance with ethics guidelines: Shao-hua HU, Shu-xing YUAN, Hai QU, Tao JIANG, Ya-jun ZHOU, Ming-xi WANG, and De-song MING declare that they have no conflict of interest.

This article does not contain any studies with human or animal subjects performed by any of the authors.

References

- 1.Abrams AJ, Trees DL, Nicholas RA. Complete genome sequences of three Neisseria gonorrhoeae laboratory reference strains, determined using PacBio single-molecule real-time technology. Genome Announc. 2015;3(5):e01052–15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01052-15. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.01052-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.An RF. A strain of Flavobacterium odoratum isolated from liver hydatid postoperative drainage liquid. Lab Med. 1992;(01):7. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Andreoni S. Isolation of Flavobacterium odoratumfrom human matter. Quad Sclavo Diagn. 1986;22(3):318–329. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bachmeyer C, Entressengle H, Khosrotehrani K, et al. Cellulitis due to Myroides odoratimimus in a patient with alcoholic cirrhosis. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2007;33:97–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02590.x. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2230.2007.02590.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Benedetti P, Rassu M, Pavan G, et al. Septic shock, pneumonia, and soft tissue infection due to Myroides odoratimimus: report of a case and review of Myroides infections. Infection. 2011;39(2):161–165. doi: 10.1007/s15010-010-0077-1. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s15010-010-0077-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bentley D. Whole-genome re-sequencing. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 2006;16(6):545–552. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2006.10.009. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.gde.2006.10.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burghartz M, Bunk B, Spröer C, et al. Complete genome sequence of the urethral catheter isolate Myroides sp. A21. Genome Announc. 2015;3(2):e00068–15. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.00068-15. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/genomeA.00068-15) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen XC, Liang L, Lin W. Analysis of elven Myroides sp. isolates from urine culture. Chin J Pract Med Tech. 2009;16(9):691–692. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chi KR. The year of sequencing. Nat Methods. 2008;5(1):11–14. doi: 10.1038/nmeth1154. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nmeth1154) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cho SH, Chae SH, Im WT, et al. Myroides marinus sp. nov., a member of the family Flavobacteriaceae, isolated from seawater. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;61(Pt 4):938–947. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.024067-0. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.024067-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crum-Cianflone NF, Matson RW, Ballon-Landa G. Fatal case of necrotizing fasciitis due to Myroides odoratus . Infection. 2014;42(5):931–935. doi: 10.1007/s15010-014-0626-0. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s15010-014-0626-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Daum LT, Fischer GW, Sromek J, et al. Characterization of multi-drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis from immigrants residing in the USA using Ion Torrent full-gene sequencing. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142(6):1328–1333. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813002409. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0950268813002409) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Geng HQ, Li XL, Li S. Isolating and identifying a strain of Flavobacterium odoratum in blood and bone marrow. Cent Plains Med J. 2000;27(3):52. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo L, Liu XF. Separation of imipenem-resistant Flavobacterium odoratum from sputum in one case. Lab Med Clin. 2011;8(2):175–177. (in Chinese) (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1672-9455.2011.02.023) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Holmes B, Snell JJS, Lapage SP. Revised description, from clinical isolates, of Flavobacterium odoratum Stutzer and Kwaschnina 1929, and designation of the neotype strain. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1977;27(4):330–336. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00207713-27-4-330) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu XL, He JY, Fu PM, et al. Participation of clinical pharmacists in one case of bone tissue infection by multidrug-resistant Flavobacterium odoratum and review of the literature. China Pharm. 2013;24(30):2873–2875. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang H, Yang ZL, Wu XM, et al. Complete genome sequence of Acinetobacter baumannii MDR-TJ and insights into its mechanism of antibiotic resistance. J Antimicrob Chemoth. 2012;67(12):2825–2832. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks327. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/jac/dks327) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang YK, Yao Y, Wang J, et al. One case of cellulitis complicated with bacteremia caused by multidrug-resistant fungus genus. J Clin Lab. 2014;327(7):5607. (in Chinese) (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.13602/j.cnki.jcls.2014.07.26) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang YM, Lin Y. A case of Flavobacterium odoratum septicemia. Chin J Infect Dis. 2003;21(2):131. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hummel AS, Hertel C, Holzapfel WH, et al. Antibiotic resistances of starter and probiotic strains of lactic acid bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2007;73(3):730–739. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02105-06. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.02105-06) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jin ZC, Xiao ZM. A case of nosocomial infection by Myroides sp. Chin J Pract Intern Med. 1995;15(3):162. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 22.Koren S, Schatz MC, Walenz BP, et al. Hybrid error correction and de novo assembly of single-molecule sequencing reads. Nat Biotechnol. 2012;30(7):693–700. doi: 10.1038/nbt.2280. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nbt.2280) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ktari S, Mnif B, Koubaa M, et al. Nosocomial outbreak of Myroides odoratimimus urinary tract infection in a Tunisian hospital. J Hosp Infect. 2012;80(1):77–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2011.09.010. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jhin.2011.09.010) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kuai S, Huang LH, Pei H, et al. Imipenem resistance due to class A carbapenemase KPC-2 in a Flavobacterium odoratum isolate. J Med Microbiol. 2011;60(Pt 9):1408–1409. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.029660-0. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/jmm.0.029660-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lan ZC, Bao GJ. The culture, isolation, identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of 23 strains of Myroides sp. Chin Commun Dr. 2009;11(14):162. (in Chinese) (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.3969/j.issn.1007-614x.2009.14.181) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MH, Chen TL, Lee YT, et al. Dissemination of multidrug-resistant Acinetobacter baumannii carrying Bla OxA-23 from hospitals in central Taiwan. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2013;46(6):419–424. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2012.08.006. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jmii.2012.08.006) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee MJ, Jang SJ, Li XM, et al. Comparison of rpoB gene sequencing, 16S rRNA gene sequencing, gyrB multiplex PCR and the VITEK2 system for identification of Acinetobacter clinical isolates. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;78(1):29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.07.013. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2013.07.013) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li CY, Zhao TL. Isolation, identification and drug sensitivity results of 12 strains of Flavobacterium odoratum . Shanghai J Med Lab Sci. 1995;10(12):96. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li H, Li Y, Xian X, et al. Three isolates of Myroides sp. from middle urinary tract. Clin Focus. 2010;25(13):1125. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu ZY, He Y. A case of pulmonary infection caused by Clay Shah Ray Prandlofs real bacteria and Flavobacterium odoratum . Pract Med Technol. 2001;8(3):175. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 31.Macfarlane DE, Baum-Thureen P, Crandon I. Flavobacterium odoratum ventriculitis treated with intraventricular cefotaxime. J Infect. 1985;11(3):233–238. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(85)93228-1. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0163-4453(85)93228-1) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mammeri H, Bellais S, Nordmann P. Chromosome-encoded β-lactamases TUS-1 and MUS-1 from Myroides odoratus and Myroides odoratimimus (formerly Flavobacterium odoratum), new members of the lineage of molecular subclass B1 metalloenzymes. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2002;46(11):3561–3567. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.11.3561-3567.2002. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.46.11.3561-3567.2002) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maraki S, Sarchianaki E, Barbagadakis S. Myroides odoratimimus soft tissue infection in an immunocompetent child following a pig bite: case report and literature review. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012;16(4):390–392. doi: 10.1016/j.bjid.2012.06.004. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2012.06.004) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marathe NP, Shetty SA, Lanjekar VB, et al. Genome sequencing of multidrug resistant novel Clostridium sp. BL8 reveals its potential for pathogenicity. Gut Pathog. 2014;6(1):30. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-6-30. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1757-4749-6-30) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Margulies M, Egholm M, Altman WE, et al. Genome sequencing in microfabricated high-density picolitre reactors. Nature. 2005;437:376–380. doi: 10.1038/nature03959. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature03959) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Meng XX, Xu XF, Lang QL. Flavobacterium and Escherichia coli were isolated from the blood, bile, ascites at the same time. Shanghai Med Test J. 1999;14(6):372. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ravindran C, Varatharajan GR, Raju R, et al. Infection and pathogenecity of Myroides odoratimimus (NIOCR-12) isolated from the gut of grey mullet (Mugil cephalus (Linnaeus, 1758)) Microb Pathog. 2015;88:22–28. doi: 10.1016/j.micpath.2015.08.001. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.micpath.2015.08.001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rolain JM, Diene SM, Kempf M, et al. Real-time sequencing to decipher the molecular mechanism of resistance of a clinical pan-drug-resistant baumannii isolate from Marseille, France. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2013;57(1):592–596. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01314-12. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AAC.01314-12) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rothberg JM, Hinz W, Rearick TM, et al. An integrated semiconductor device enabling non-optical genome sequencing. Nature. 2011;475(7356):348–352. doi: 10.1038/nature10242. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1038/nature10242) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schröttner P, Rudolph WW, Eing BR, et al. Comparison of VITEK2, MALDI-TOF MS, and 16S rDNA sequencing for identification of Myroides odoratus and Myroides odoratimimus . Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2014;79(2):155–159. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.02.002. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2014.02.002) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shi WF, Zhou KQ. Isolation of a strain of Flavobacterium odoratum from cerebrospinal fluid. Shanghai J Med Lab Sci. 1993;8(4):211. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 42.Snitkin ES, Zelazny AM, Gupta J, et al. Genomic insights into the fate of colistin resistance and Acinetobacter baumannii during patient treatment. Genome Res. 2013;23(7):1155–1162. doi: 10.1101/gr.154328.112. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/gr.154328.112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Song CG. One case of severe iatrogenic pulmonary infection caused by Flavobacterium odoratum . Chin J Hosp Infect. 2005;15(10):1141. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 44.Song KY, Zhang HW, Zhang XY. A case of chewing muscle abscess caused by Flavobacterium odoratum . Shanghai Med Test J. 1995;10(4):245. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 45.Spanik S, Trupl J, Krcmery V. Nosocomial catheter-associated Flavobacterium odoraturn bacteraemia in cancer patients. J Med Microbiol. 1998;47(2):183. doi: 10.1099/00222615-47-2-183. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00222615-47-2-183) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Stutzer M, Kwaschnina A. Aussaaten aus den Fäzes des Menschen gelbe Kolonien bildende Bakterien (Gattung Flavobacterium u.a.) Zentralbl Bakteriol Parasitenkd Infektionskr Hyg Abt 1 Orig. 1929;113:219–225. (in German) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Suganthi R, Priya TS, Saranya A, et al. Relationship between plasmid occurrence and antibiotic resistance in Myroides odoratimimus SKS05-GRD isolated from raw chicken meat. World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2013;29(6):983–990. doi: 10.1007/s11274-013-1257-9. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11274-013-1257-9) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sun XH, Zhang CL. A strain of Flavobacterium odoratum isolated from wounds in one case of traumatic patient. Chin Commun Dr. 2006;12(8):82. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tan SY, Chua SL, Liu Y, et al. Comparative genomic analysis of rapid evolution of an extreme-drug-resistant baumannii clone. Genome Biol Evol. 2013;5(5):807–818. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evt047. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/gbe/evt047) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tatusova T, Ciufo S, Federhen S, et al. Update on RefSeq microbial genomes resources. Nucleic Acids Res. 2015;43(D1):D599–D605. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku1062. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/nar/gku1062) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tian GZ, Wang XL. Advances in the study of Flavobacterium indologenes . J Pathog Biol. 2010;5(2):134–136. (in Chinese) (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.13350/j.cjpb.2010.02.018) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Vancanneyt M, Segers P, Torck U, et al. Reclassification of Flavobacterium odoratum (Stutzer 1929) strains to a new genus, Myroides, as Myroides odoratus comb. nov. and Myroides odoratimimus sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46(4):926–932. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/00207713-46-4-926) [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang YL, Su FM. A case of neonatal septicemia caused by Flavobacterium odoratum . Lab Med. 1992;(4):248. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 54.Wu GM. Flavobacterium odoratum was detected from a burn patient blood and many other parts. Shanghai J Med Lab Sci. 1998;13(1):34. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wuer GL, Aisi KE, Gu HE. One cases Flavobacterium odoratum isolated from urine separation. J Clin Lab. 2002;20(1):44. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Yağci A, Cerikçioğlu N, Kaufmann ME, et al. Molecular typing of Myroides odoratimimus (Flavobacterium odoratum) urinary tract infections in a Turkish hospital. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2000;19(9):731–732. doi: 10.1007/s100960070001. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s100960070001) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yan S, Zhao N, Zhang XH. Myroides phaeus sp. nov., isolated from human saliva, and emended descriptions of the genus Myroides and the species Myroides profundi Zhang et al. 2009 and Myroides marinus Cho et al. 2011. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2012;62(Pt 4):770–775. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.029215-0. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.029215-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yang JH, Wang LY. A case of Flavobacterium odoratum wound infection. Pract Med Technol. 2001;8(7):542. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Yoon J, Maneerat S, Kawai F, et al. Myroides pelagicus sp. nov., isolated from seawater in Thailand. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2006;56(Pt 8):1917–1920. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.64336-0. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.64336-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang BC, Zhang JT. Neonatal sepsis associated with meningitis and strain identification of Flavobacterium odoratum . Tianjin Med. 1996;24(3):181–182. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zhang XY, Zhang YJ, Chen XL, et al. Myroides profundi sp. nov., isolated from deep-sea sediment of the southern Okinawa Trough. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2008;287(1):108–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01299.x. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1574-6968.2008.01299.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhang ZD, He LY, Huang Z, et al. Myroides xuanwuensis sp. nov., a mineral-weathering bacterium isolated from forest soil. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2014;64(Pt 2):621–624. doi: 10.1099/ijs.0.056739-0. (Available from: http://dx.doi.org/10.1099/ijs.0.056739-0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zhao SQ. One case of children with Flavobacterium odoratum septicemia. New Med. 2000;31(8):482–483. (in Chinese) [Google Scholar]