Abstract

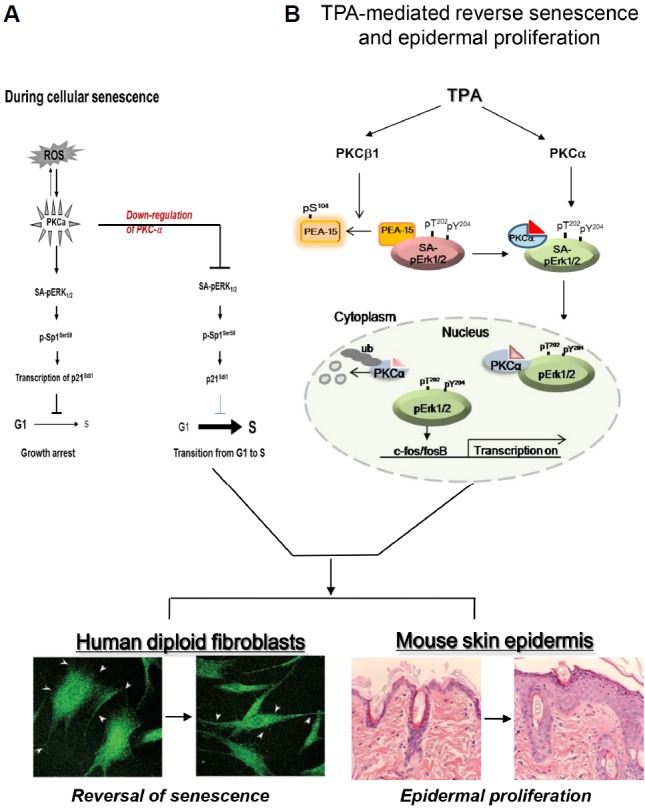

The mechanism by which 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) bypasses cellular senescence was investigated using human diploid fibroblast (HDF) cell replicative senescence as a model. Upon TPA treatment, protein kinase C (PKC) α and PKCβ1 exerted differential effects on the nuclear translocation of cytoplasmic pErk1/2, a protein which maintains senescence. PKCα accompanied pErk1/2 to the nucleus after freeing it from PEA-15pS104 via PKCβ1 and then was rapidly ubiquitinated and degraded within the nucleus. Mitogen-activated protein kinase docking motif and kinase activity of PKCα were both required for pErk1/2 transport to the nucleus. Repetitive exposure of mouse skin to TPA downregulated PKCα expression and increased epidermal and hair follicle cell proliferation. Thus, PKCα downregulation is accompanied by in vivo cell proliferation, as evidenced in 7, 12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA)-TPA-mediated carcinogenesis. The ability of TPA to reverse senescence was further demonstrated in old HDF cells using RNA-sequencing analyses in which TPA-induced nuclear PKCα degradation freed nuclear pErk1/2 to induce cell proliferation and facilitated the recovery of mitochondrial energy metabolism. Our data indicate that TPA-induced senescence reversal and carcinogenesis promotion share the same molecular pathway. Loss of PKCα expression following TPA treatment reduces pErk1/2-activated SP1 biding to the p21WAF1 gene promoter, thus preventing senescence onset and overcoming G1/S cell cycle arrest in senescent cells.

Keywords: HDF, PKCα, PKCβ1, SA-pErk1/2, tumor promotion

INTRODUCTION

A failure to induce epithelial cell senescence can significantly increase the risk of carcinogenic progression in both human and animals (Collado et al., 2005; Vernier et al., 2011). In fact, benign prostate hyperplasia, lung adenoma, intraductal neoplasia of the pancreas, skin papilloma, and other similar conditions can be successfully protected from cancer progression by oncogene-induced senescence, with cellular senescence functioning as a critical barrier that inhibits cancer progression. One of the characteristic features of senescent cells is the cytoplasmic sequestration of senescence-associated pErk1/2 (SA-pErk1/2), as opposed to G-actin accumulation in senescent cell nuclei (Lim et al., 2000). Potential mechanisms underlying the failure of pErk1/2 to translocate to the nucleus following growth factor stimulation include the inactivation of protein phosphatase 1 and 2A and MKP3/DUSP6 by reactive oxygen species (ROS) that accumulate in senescent human diploid fibroblasts (HDF) (Kim et al., 2003). However, when these senescent cells are exposed to 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate (TPA) for 8 h, the morphology of the old cells changes to resemble that of young cells, and there is a reversal in the expression of senescence markers, resulting in G1/S progression and cell proliferation (Kim and Lim, 2009; Kwak et al., 2004; Lee et al., 2015).

Treating senescent cells with TPA triggers the rapid dissociation of SA-pErk1/2 from the phosphoprotein enriched in astrocytes (PEA-15) and induces pErk1/2 translocation to the nucleus (Lee et al., 2015). In fact, TPA treatment or RNA interference-mediated knockdown of PKCα expression significantly induces the proliferation of old HDF cells (Kim and Lim, 2009). Collectively, these findings strongly support PKCα having a direct role in reversing senescent cell phenotypes. Indeed, PKCα is a mediator of G2/M cell cycle arrest and cellular senescence via the induction of p21WAF1 expression in the asynchronously growing non-small cell lung cancer cells (Oliva et al., 2008) and in primary cultures of HDF cells (Kim and Lim, 2009). Considering that TPA initially activates PKC isozymes and then downregulates their expression (Lu et al., 1998), the findings mentioned above strongly suggest that PKCα downregulation might promote the reversal of primary culture HDF cell senescence. To the best of our knowledge, there are no published studies reporting that TPA reverses senescence phenotypes by downregulating PKC isozymes in both cultured cells and animal models. Moreover, we investigated the reversal of gene expression profiles by performing RNA sequencing following TPA treatment and also validated mitochondrial respiration and metabolism.

The PKC protein family is divided into 4 subfamilies (conventional, novel, atypical, and distant) based on their cofactor requirements (Clemens et al., 1992; Nishizuka, 1995). Traditionally, PKC is known as a high affinity intracellular receptor for phorbol ester, a potent tumor promoter. Phorbol esters directly activate PKC, indicating that PKC is critically involved in growth control. Thus, it is widely accepted that PKC has a pivotal role in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation (Clemens et al., 1992; Nishizuka, 1992). Phorbol esters trigger longer PKC activation than physiological regulators: prolonged vs. transient PKC activation is an important distinction that may form the basis for phorbol ester-induced tumor promotion (Jaken, 1990; Nishizuka, 1992). Upon stimulation, PKCα translocates from the cytosol to particulate fractions (Buchner, 1995). We have observed that the stimulation of HDF cells with TPA activates PKCα, PKCβ 1 and PKCη (Kim and Lim, 2009), consequently the isozymes moving from cytosol to particulate fractions in HDF cells. This suggested that PKC might have an important role in senescence, whereas the exact roles of PKC isozymes in reversal of senescence and carcinogenesis have not yet been reported.

The activity, but not amount, of PKCα is higher in the senescent cells than in the young cells due to the accumulation of ROS, which stimulates SA-pErk1/2 and p21WAF1 transcription to help maintain senescence (Kim and Lim, 2009). Indeed, the treatment of HepG2 cells with TPA induces PKCα activation along with Erk1/2 signaling and growth inhibition (Wen-Sheng and Jun-Ming, 2005), implying that all factors regulating the mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) signaling pathway are involved in the activation of PKCα in response to TPA (Alexandropoulos et al., 1993; Thomas et al., 1992). To achieve their effects, these signals have to reach the nucleus after activation; thus, Buchner (1995) suggested several possibilities for PKC-mediated signal transduction into the nucleus. On the other hand, signal transduction to the nucleus might also be accomplished by the nuclear translocation of PKC itself via a nuclear pore complex following activation in the cytoplasm and phorbol ester-stimulated Erk1 via protein-tyrosine/threonine kinase activation (Alessandrini et al., 1992).

The MAPK pathway regulates various physiologic functions, including cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis (Chang and Karin, 2001; Pearson et al., 2001). In addition, ERK1 and ERK2, the terminal elements of this pathway, activate transcription factors (e.g., c-fos and Elk-1) in the nucleus upon their phosphorylation (Cruzalegui et al., 1999; Kazi and Soh, 2008). Therefore, pErk1/2 must translocate to the nucleus to activate downstream transcription factors in response to various stimuli, and a significant fraction (≥ 50%) of pErk1/2 can be found in the nucleus within 10 min of stimulation with a growth factor and phorbol ester (Chen et al., 1992). The redistribution of pErk1/2 is regulated by its interaction with various proteins, including PEA-15 (Camps et al., 1998; Menice et al., 1997), which directly binds to Erk1/2 or pErk1/2 in vitro and in vivo (Araujo et al., 1993). Through this activity, PEA-15 indirectly contributes to the maintenance of cellular senescence, and its phosphorylation at S104 blocks its interaction with ERK (Krueger et al., 2005; Renganathan et al., 2005; Vaidyanathan et al., 2007). Through this activity, PEA-15 indirectly contributes to the maintenance of cellular senescence, and its phosphorylation at S104 blocks its interaction with ERK. The above findings prompted us to explore how PKC isozymes and Erk1/2 interact to reverse senescence and promote carcinogenesis following TPA stimulation, with a focus on the differential activities of PKCα and PKCβ1. In addition, we investigated changes in the kinetics of PKC degradation during the early and late stages of reverse senescence in response to TPA. Our results show that PKCβ1 activity dissociates SA-pErk1/2 from PEA-15 and that PKCα functions as a carrier protein facilitating pErk1/2 translocation to senescent cell nuclei. The PKCα kinase domain and its MAPK docking motif were both required for nuclear translocation of SA-pErk1/2 in senescent cells. PKCα degradation within the nucleus occurred in conjunction with pErk1/2 inactivation, resulting in the proliferation of senescent HDF cells and CD1 mouse epidermal cells following the application of skin carcinogenesis-inducing 7, 12-dimethylbenz(a)anthracene (DMBA)/TPA. These data imply that the molecular changes observed during tumor promotion are similar to the changes that occur upon senescence reversal following TPA stimulation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

TPA and 7, 12-dimethylbenz[a]anthracene (DMBA) were purchased from Sigma (USA). Antibodies to pErk1/2, Erk1/2, PEA-15pS104 and PEA-15 were from Cell Signaling (USA); against PKCβ1, Lamin B1, HA, ubiquitin (Ub) and α-tubulin were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (USA); against PKCα from Novus Biologicals (Littleton, USA). Active forms of PKCα and PKCβ1, and PKC activators were purchased from Millipore (USA).

Cell culture

HDF cells were isolated in our laboratory from the foreskin of 1–4 years old boys and maintained in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM, Invitrogen/GIBCO, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS; Invitrogen). The cell line preparation was undertaken with the understanding and written consent of each subject, and the study methodologies conformed to the standards set by the Declaration of Helsinki. The obtained normal tissues were used after informed written consent according to the regulation of Institutional Review Board at the Ajou University Hospital. The subjects were not injured or abused during the study. All tissues were immediately used after resection and the prepared cells were maintained more than 6 months in order to make the replicatively senescent cells (doubling time over 14 days). To perform the planned experiments, the primary cultures of various passages stored at the liquid nitrogen tanks were revived before use for the experiments. To examine the primary cultures, karyotyping was performed with HDF young and HDF old cells and the chromosome arrangements were analyzed under the microscope (Olympus, BX50F-3) with Cytovision 3.92 (Applied Imaging, England). Number of population doublings and their doubling times were calculated by the published equations (Kim and Lim, 2009). HDF young cells, mid-old and old cells used in this study represent doubling time of around 26 h, around 4–10 days and over 14 days, respectively. Huh7 cells were obtained from Japanese Collection of Research Bioresources Cell Bank (Japan) and cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% FBS. All cells used in this study were maintained in 5% CO2 incubator at 37°C.

Cell fractionation

Cells were harvested, washed with ice cold 1× PBS, and then lysed in 250 μl of TD buffer [25 mM Tris base (pH 8.0), 2.0 mM MgCl2, 0.25% v/v Nonident P40, 0.5 mM DTT, 1.0 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μg/ml PMSF, 1.0 mM Na3VO4, 1.0 mM NaF] for 5 min at room temperature (RT). The lysates were centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 5 min and the supernatant was collected as cytoplasmic fraction. The pellets were suspended in 125 μl of BL buffer [10 mM Tris (pH 8.0), 0.4 M LiCl, 0.5 mM DTT, 1.0 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μg/ml PMSF, 1.0 mM Na3VO4, 1.0 mM NaF] for 5 min, and followed by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 20 min to remove cell debris, and used as nuclear fraction. Protein concentration of each sample was assessed by BioRad protein assay kit (USA).

Immunoblot (IB) analysis

Cells were solubilized in RIPA buffer [50 mM Tris/HCl (pH 7.5), 150 mM NaCl, 1.0% Nonidet P40, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% deoxycholic acid, 1.0 μg/ml leupeptin, 100 μg/ml PMSF, 1.0 mM Na3VO4, 1.0 mM NaF], cleared by centrifugation at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C, and then 40 μg of the lysates (per lane) were resolved on 10–15% SDS-PAGE in 25 mM Tris/glycine buffer. The protein bands were transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride membrane and then treated with 5% non-fat skim milk in PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBST) for 1 h before incubation with antibodies overnight at 4°C, and then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies for 1 h. ECL (Amersham Biosciences, UK) was employed to visualize the bands.

Immunoprecipitation (IP)

Immunoprecipitation was performed with cell lysates (∼1.0 mg protein) in the modified RIPA buffer (without 0.1% SDS from RIPA) by the standard method. Whole cell lysates were pre-cleared with protein G-agarose beads (Invitrogen) for 1 h at 4°C before precipitation for 4 h with primary antibodies at 4°C. The immunoprecipitates were washed 5 times with IP buffer, and then subjected to IB analysis.

Immunocytochemistry (ICC)

Cells on cover slips (18 mm × 18 mm) in 6-well plates were washed twice with 1 × PBS before fixation with 4% paraformaldehyde for 15 min, permeabilized with 0.05% Triton X-100 (diluted in 1×PBS) for 15 min, and then subjected to blocking with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 0.05% Triton X-100 at 4°C for 2 h. The cells were incubated overnight with primary antibody at 4°C, with secondary antibody at 4°C for 2 h, and then stained with 4% 6-diamidino-2-phenylindole (DAPI, 1.0 μg/ml) for 5 min at RT before mounting with Mowiol medium (Hoeschst Celanese, USA) containing antifade 1,4-diazabicyclo [2,2,2]octane (Aldrich, USA). Expressions of pErk1/2, PKCα, PKC mutants, PKCβ1 and ubiquitin (Ub) were detected using monoclonal or polyclonal primary antibodies along with Alexa 488 or Alexa 594 conjugated secondary antibodies. Data acquisition under fluorescence microscope was done by Axio-Vision with software package (Carl Zeiss MicroImaging GmbH, Germany), and Images were analyzed by Eclipse Ti (Nikon, Japan) or A1 confocal microscope (Japan).

Two stage skin carcinogenesis

CD-1 male mice (7 week old) purchased from ORIENT BIO Inc (Korea) were acclimatized in the animal house of Ajou University animal facilities for 3 weeks before shaving the hair. TPA (5 μg/200 μl acetone) was topically applied on the back skin of the mice for 2 weeks (twice/week) with or without DMBA (100 μg/200 μl acetone) initiation 1 week before TPA treatment according to the protocol (Abel et al., 2009). Mice were sacrificed on 3 days of the TPA final treatment, and then the back skin was surgically removed and embedded in the O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek, USA) for frozen section or fixed in 10% formalin solution for paraffin embedding. Paraffin sections were cut (4 μm thickness), and processed for hematoxylin–eosin (H&E) staining according to the described method (Devanand et al., 2014). All of the animal procedures were followed by Ajou University Institutional Review Board.

Immunofluorescence (IF) study

Frozen sections (10 μm thickness) fixed at RT for 15 min were incubated in 0.3% H2O2 in PBS for 10 min to block endogenous peroxidase activity, and then incubated in 0.05% Triton X-100 containing 10% BSA for 40 min at RT before washing 3 times with 1× PBS. The rest of the procedures followed the method described under the above immunocytochemistry. PKCα was detected using monoclonal antibody along with Alexa 488 conjugated goat-anti mouse IgG as a secondary antibody.

GST-pull down and in vitro kinase-IB analyses

Recombinant GST-PEA-15 proteins were expressed in E.coli strain BL21 (DE3) and purified to homogeneity using glutathione agarose 4B beads (Incospharm, Korea). The GST- or GST-PEA-15-conjugated glutathione agarose 4B beads were washed twice with kinase buffer [50 mM HEPES, (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM DTT, 2.5 mM EGTA, protease inhibitors and phosphatase inhibitors], and then in vitro kinase assay was initiated with 100–200 ng of GST-PEA-15, 400 μM ATP and 0.1 μg PKCβ1 enzyme (Millipore, USA) in 10 μl of the buffer. Reaction mixtures were incubated at 30°C for 30 min, and then terminated by adding SDS sample buffer with subsequent boiling for 5 min. Enzyme activity was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and immunoblotting with anti-pPEA-15S104 (AssaybioTech, USA) or anti-GST (Santa Cruz) antibodies. GST was employed as a control substrate of the assay.

siRNA transfection

siRNAs against PKCα (siPKCα) were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology, siPKCβ1 (Sense - 5′ CAUUACAUUUCAAACUUUAUU 3′, Antisense - 5′ UAAAGUUUGAAAUGUAAUGUU 3′) from Genolution Pharmaceuticals (Asan Institute for Life Sciences, Korea), and control siRNAs (siControl) were from DHARMACON (USA). HDF old cells cultured on a cover slip (18 mm × 18 mm) in 6-well plates were transfected with siRNAs and oligofectamine (Invitrogen) for 4–6 h. After 48 h, the cells were treated with either DMSO (0.01%) or TPA (50 ng/ml) for 30 min before subjected to ICC or IB analyses.

Plasmid transfection

Huh7 cells cultured in 6-well plates (5 × 104 cells/well) or 100 mm dishes (2 × 105 cells/well) were transiently transfected with 2 or 10 μg of pHACE (vector), wt-PKCα or mt-PKCα (R159,161G) using Fugene (Promega, USA), and then subjected to ICC or cell fractionations into nuclei and cytoplasm in 48 h of transfection.

Site-directed mutagenesis

To confirm the interaction of PKCα with pErk1/2, three different PKCα mutants [MAPK docking motif (R159, 161G) double mutant, kinase dead PKCα (KD-PKCα) and catalytically active PKCα (CA-PKCα)] were prepared along with wild type PKCα (Supplementary Fig. S3A). MAPK docking motif in the regulatory and catalytic domains of PKCα was predicted and searched by using website http://elm.eu.org and based on the published reports (Bardwell et al., 2001; Yang et al., 1998). Arginine residues at 159 and 161 in the regulatory domain of PKCα were mutated to glycine (R159, 161G) by using QuikChange II site--directed mutagenesis kits (Stratagene, USA) according to the manufacturer’s recommendations. Wild type PKCα-HA plasmid in pHACE vector was used as a template and the specific mutation was confirmed by DNA sequencing.

RNA-sequencing analysis

The integrity of RNAs isolated from HDF senescent cells treated with TPA for 8 h and 24 h, or DMSO control, was confirmed by bioanalyzer with an Agilent RNA 6000 Pico Kit (Agilent, USA), and then mRNA sequencing library was prepared by TruSeq stranded mRNA sample preparation kit (Illumina, USA) according to manufacturer’s instruction. The functional category analyses of the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) were performed by DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncifcrf.gov), Enrichr (http://amp.pharm.mssm.edu/Enrichr/) or PANTHER (http://pantherdb.org/) tools. The DEGs were selected with the significance level of p < 0.001 or false discovery rate < 0.05 after multiple testing corrections for the compared conditions, TPA 8 h vs. 0 h (DMSO control) and TPA 24 h vs. 0 h (DMSO control).

Real-time PCR analysis

Total cellular RNAs were extracted with RNAiso Plus (TaKaRa Bio, Japan), and cDNAs were synthesized with RNA 1.0 μg and reverse transcription kit (Invitrogen). The cDNAs were amplified with specific primers and SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) under the conditions by using CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio Rad, USA): Initial activation at 95°C for 15 min, followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 20 s and 60°C for 40 s. Primers used for assays were listed in Table 1. To quantify transcriptional activity, 18S rRNA expression was measured as a control.

Table 1.

Primers used for real-time PCR analyses

| Gene | Primer | |

|---|---|---|

| P21waf1 | Forward | 5′-CGACTGTGATGCGCTAATGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CCGTTTTCGACCCTGAGAG-3′ | |

| FH (fumarate hydratase) | Forward | 5′-CCATGTTGCTGTCACTGTCGGAGG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-CATACCCTATATGAGGATTGAGAG-3′ | |

| IDH1 (isocitrate dehydrogenase) | Forward | 5′-ACCAATCCCATTGCTTCCATTTTT-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TCAAGTTTTCTCCAAGTTTATCCA-3′ | |

| IDH2 (isocitrate dehydrogenase 2) | Forward | 5′-CAGGAGATCTTTGACAAGCAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-ATGAGGTCTTGGTTCCCATC-3′ | |

| MDH2 (malate dehydrogenase 2) | Forward | 5′-GCTCTGCCACCCTCTCCATG-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TTTGCCGATGCCCAGGTTCTTCTC-3′ | |

| 18S rRNA | Forward | 5′-GGAGAGGGAGCCTGAGAAAC-3′ |

| Reverse | 5′-TCGGGAGTGGGTAATTTGC-3′ |

Determination of ATP content

Total amount of ATP in HDF cells were measured by using ATP determination kit produced by Molecular Probes (Invitrogen) based on the described method (Candas et al., 2013) with slight modification. Young and old HDF cells were incubated for 24 h before trypsinization, and the cells harvested by centrifugation at 4,800 × g for 5 min at 4°C were resuspended in 1% trichloroacetic acid/4 mM EDTA solution. ATP extraction was performed by incubating the cells for 10 min on ice and then centrifuged at 12,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C to harvest supernatant for ATP measurement. Concentration of protein in the pellets were measured by vigorous vortexing in RIPA buffer and discarding the debris after centrifugation for 20 min. Level of ATP luminescence was measured by using BioTek Synergy 2 microplate reader and the contents of ATP were calculated based on the standard curves obtained from known amounts of ATP. Concentration of ATP was normalized by amount of protein isolated from used cells.

Statistical analysis

All data were presented as means ± S.D and analyzed by 1-way ANOVA for comparison between multiple groups using SPSS. Probability values less than 0.05 were considered as statistically significant.

RESULTS

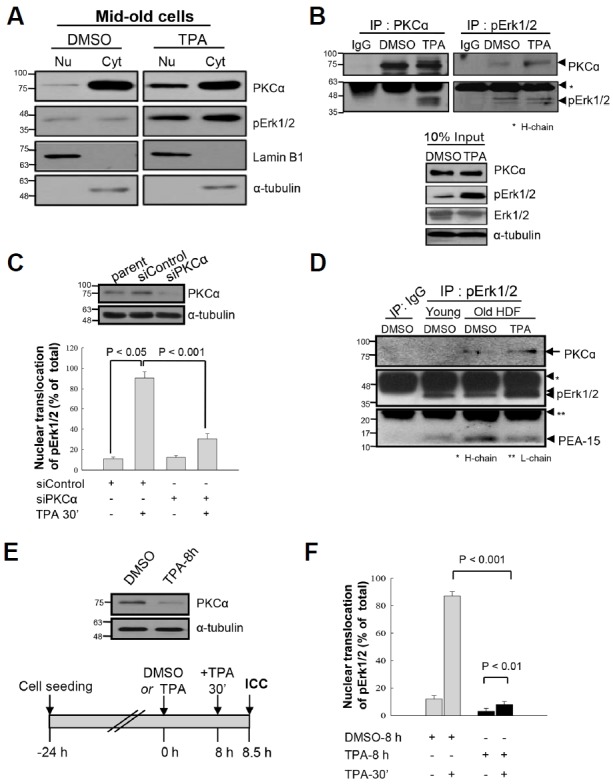

PKCα is required for pErk1/2 translocation to the HDF cell nucleus in response to TPA stimulation

To assess the TPA-mediated activation and re-distribution of PKC isoforms, senescent HDF cells were fractionated and subjected to immunoblot (IB) analysis. TPA treatment significantly increased PKCα and pErk1/2 translocation to the cell nucleus (Fig. 1A), whereas PKCβ1 localization did not change despite the increase of pErk1/2 in the cell nuclear fraction (Supplementary Figs. S1A–1C). To evaluate whether pErk1/2 translocation was physically coupled with PKCα localization, HDF cells with or without TPA treatment were subjected to coimmunoprecipitation (IP) and IB analyses with anti-pErk1/2 and anti-PKCα antibodies. Figure 1B shows increased interaction between PKCα and pErk1/2 after TPA treatment despite the same quantity of PKCα being present in the 10% inputs of the DMSO- and TPA-treated cells. These results suggest the cotranslocation of PKCα with pErk1/2. Indeed, the knockdown of PKCα expression significantly reduced pErk1/2 translocation after TPA treatment (Fig. 1C, p < 0.001), indicating a role for PKCα in pErk1/2 translocation. Conversely, no interaction between pErk1/2 and PKCβ1 was observed by in vivo IP assay (Supplementary Fig. S1D). Based on our evidence that TPA treatment reduces tethering of SA-pErk1/2 to PEA-15 in the cytoplasm of old HDF cells (Lee et al., 2015), interactions between pErk1/2, PEA-15, and PKCα were evaluated by IP and IB analyses. The results showed that in old, but not young, cells, pErk1/2 was bound to PEA-15 prior to TPA stimulation. However, pErk1/2 interacted with PKCα upon TPA treatment (Fig. 1D). When temporal changes in the nuclear translocation of PKCα and pErk1/2 were evaluated by immunocytochemical assay (ICC), translocation was observed to be significant at 30 min and maintained until 8 h after TPA treatment compared with that of control cells treated with DMSO (Supplementary Fig. S2B). Translocation was accompanied by a change in cell shape from large and flat to small and sharp (Supplementary Fig. S2A). The protein expression of PKCα, but not Erk1/2 and PEA-15, was almost undetectable at 8 h after stimulation (Supplementary Fig. S2C). When PKCα expression was depleted by TPA pretreatment for 8 h (Fig. 1E), nuclear translocation of pErk1/2 stimulated by TPA re-stimulation for 30 min was significantly reduced (Fig. 1F, p < 0.001, 2nd and 4th bars), although some response was still observed (Fig. 1F, p < 0.01 vs. DMSO 8.5 h). These data strongly suggest the regulation of pErk1/2 translocation by PKCα upon the TPA stimulation of senescent cells.

Fig. 1.

Expression of PKCα is required for translocation of pErk1/2 to nuclei of HDF cells in response to TPA. (A) HDF mid-old cells were treated with either DMSO (0.01%) or TPA (50 ng/ml) for 30 min and the nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions of the cells were subjected to immunoblot analysis using anti-PKCα and anti-pErk1/2 antibodies. TPA treatment significantly increased the amounts of PKCα and pErk1/2 in the particulate fraction, compared with DMSO treatment. Lamin B1 and α-tubulin expressions were employed as markers of nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions. (B) To evaluate whether pErk1/2 translocation to nuclei was accompanied with PKCα or not, co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) analysis was performed with anti-pErk1/2 and anti-PKCα antibodies. As shown in the 10% input, TPA increased pErk1/2 level, however, the protein expression of PKCα was independent of TPA treatment for 30 min (lower panel). Based on the co-IP data (upper panels), the amount of pErk1/2 immunoprecipitates was the same in the DMSO and TPA treatment cells, whereas interaction of PKCα with pErk1/2 was clearly increased by TPA treatment. (C) To test whether PKCα protein is required for the TPA-induced pErk1/2 translocation or not, knockdown of PKCα expression was employed by transfection of siRNAs with or without TPA treatment for 30 min, and the degree of pErk1/2 translocation was examined by immunocytochemistry (ICC). TPA treatment markedly increased translocation of pErk1/2 into nuclei (p < 0.05), however, the effect of TPA was clearly reduced by knockdown of PKCα expression (p < 0.001), indicating the requirement of PKCα protein for the pErk1/2 translocation to nuclei. Senescent HDF cells with pErk1/2 in nuclei were counted and presented by % of total cells (lower panel). Upper panel shows knockdown of PKCα expression after transfection of siRNAs. The same experiments were performed more than 3 times and counted more than 100 old cells per each experiment. (D) To evaluate the interactions among PKCα, pErk1/2 and PEA-15 in HDF old cells, IP was performed with anti-pErk1/2 antibody. The constitutive interaction between SA-pErk1/2 and PEA-15 in old cells was significantly higher than that of the young cells, whereas it was reduced after TPA treatment up to the young cell level, in contrast to the increased interaction between pErk1/2 and PKCα. The data suggest the mutually exclusive interaction of SA-pErk1/2 with either PEA-15 or PKCα upon TPA treatment in senescent cells. IP with IgG reveals specific binding of pErk1/2 to PKCα or PEA-15. (E, F) To further confirm the effect of PKCα protein on the TPA-induced nuclear translocation of pErk1/2, senescent HDF cells were treated again with TPA for 30 min after TPA pretreatment for 8 h, and then ICC with anti-pErk1/2 antibody was performed. The 8 h-TPA pretreatment significantly reduced PKCα expression [upper panel in (E)] along with the significant reduction of the 30 min-TPA effect on the pErk1/2 translocation as compared with that of the 8 h-DMSO pretreatment [p < 0.001, (F)]. However, the cells still maintained TPA effect on the pErk1/2 translocation [p < 0.01, (F)].

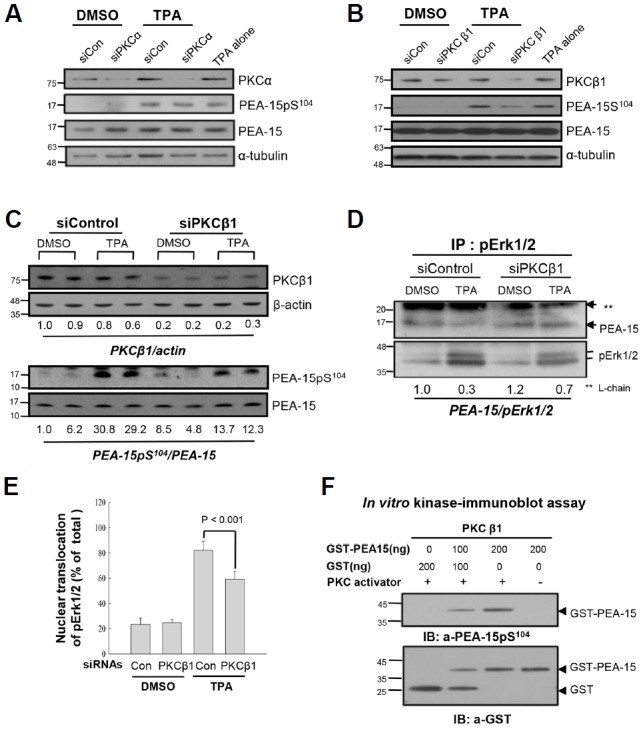

PKCβ1, but not PKCα, regulates PEA-15 phosphorylation at S104 in response to TPA, causing PEA-15 to dissociate from pErk1/2 in old HDF cells

Because there is no information on which PKC isoform(s) phosphorylate(s) PEA-15 at residue S104, either PKCα or PKCβ1 expression was knocked down using specific small interfering (si) RNAs, and PEA-15pS104 expression was determined by IB analysis. Transfection of old HDF cells with siPKCα failed to reduce PEA-15pS104 expression after TPA treatment (Fig. 2A), whereas transfection with siPKCβ1 significantly downregulated PEA-15pS104 (Fig. 2B). These data suggest that PKCβ1 is an in vivo kinase for PEA-15pS104. Furthermore, when PKCβ1 expression was reduced by siPKCβ1 transfection (from 0.6–1.0 to 0.2–0.3 seen with siControl), the TPA-stimulated PEA-15pS104 level was also reduced to 12.3–13.7 compared with 29.2–30.8 in the siControl-treated cells, indicating a reduction in TPA-induced PEA-15pS104 following PKCβ1 knockdown (Fig. 2C). Moreover, IP-IB analysis showed that PKCβ1 knockdown also failed to dissociate PEA-15 from binding to pErk1/2 after TPA treatment (0.7 vs. 0.3) (Fig. 2D). Thus, PKCβ1 probably contributes to PEA-15 phosphorylation on residue S104 after TPA treatment. It should be noted that TPA-induced pErk1/2 translocation was inhibited 25% by PKCβ1 knockdown (Fig. 2E), indicating a partial influence of PKCβ1 on the TPA-induced nuclear translocation of pErk1/2 after dissociation from PEA-15pS104. Moreover, in vitro kinase and IB analyses using a recombinant protein substrate and purified enzyme revealed that PKCβ1 catalyzes GST-PEA-15 phosphorylation on residue S104 in the presence of a PKC activator (Fig. 2F). These data further support PKCβ1 as the in vivo kinase phosphorylating PEA-15 on residue S104.

Fig. 2.

PKCβ1, not PKCα, regulates phosphorylation of PEA-15 at S104 in response to TPA, which dissociates pErk1/2 from PEA-15 in HDF old cells. (A) To explore PKC isozymes which regulate PEA-15pS104, knockdown of PKCα was performed by transfection of senescent HDF cells with siRNAs to PKCα (siPKCα) for 48 h, and the cells were treated with DMSO or TPA for 30 min before IB analysis. The scrambled siRNAs (siCon) and α-tubulin were used as controls for transfection and immunoblot analyses, respectively. Note persistence of PEA-15pS104 after TPA treatment in the siPKCα transfected cells similar to the TPA alone treated cells, indicating not so significant effect of PKCα on the regulation of PEA-15 phosphorylation. (B) To investigate effect of PKCβ1 on the TPA-mediated phosphorylation of PEA-15 at S104, senescent HDF cells were transfected with siRNAs to PKCβ1 (siPKCβ1) for 48 h and then treated with TPA for 30 min. The cell lysates were analyzed by IB with anti-PKCβ1, anti-PEA-15pS104 or anti-PEA-15 antibodies. Note downregulation of PEA-15 phosphorylation after knockdown of PKCβ1 compared with that of the control. siCon and α-tubulin were used as controls for transfection and immunoblot analyses, respectively. (C) To confirm the role of PKCβ1 in the regulation of PEA-15 phosphorylation, degradation of PKCβ1 was manipulated by transfection with siPKCβ1 for 48 h and then changes of PEA-15pS104 by TPA treatment for 30 min were measured based on the amount of PEA-15 expression. PKCβ1 expression was downregulated up to 20–30% than that of the siCon, based on actin expression (PKCβ1/actin; 0.2–0.3 vs.1.0), whereas TPA-induced PEA-15 phosphorylation was reduced more than 50% by knockdown of PKCβ1 (PEA-15pS104/PEA-15 ratio; 12.3–13.7 vs. 30). (D) To evaluate whether knockdown of PKCβ1 regulates interaction of pErk1/2 with PEA-15 or not, HDF old cells transfected with either siCon or siPKCβ1 were treated with TPA for 30 min and then the cell lysates were subjected to IP-IB analysis. TPA treatment significantly reduced interaction of pErk1/2 with PEA-15 (0.3 vs. 1.0), however, it was recovered in part by transfection of siPKCβ1 than that of the siCon (0.7 vs. 0.3). The data strongly suggest in vivo regulation of PEA-15 phosphorylation at S104 residue by PKCβ1 in response to TPA. (E) To explore whether PKCβ1-induced PEA-15pS104 regulates nuclear translocation of pErk1/2 in response to TPA, more than 500 old cells were captured and the cells with pErk1/2 in nuclei were counted under the microscope. Bars represent the means ± SD after 3 independent experiments. TPA-induced nuclear translocation of pErk1/2 was significantly reduced by transfection with siPKCβ1 compared with that of the siControl (p < 0.001), indicating that PKCβ1 is active in the regulation of pErk1/2 translocation to nuclei via PEA-15 phosphorylation at S104 residue. (F) To evaluate activity of PKC isozyme regulating PEA-15pS104, in vitro kinase assay was performed for 30 min at 30°C with GST-PEA-15 as a substrate and PKCβ1 with or without PKC activator. PEA-15 phosphorylation at S104 residue was determined by immunoblot analysis with anti-PEA-15pS104antibody. PKCβ1 activity was increased in the substrate concentration dependent manner in the presence of PKC activator. Hybridization of the reaction mixture with anti-GST antibody showed proteins loaded into each reaction.

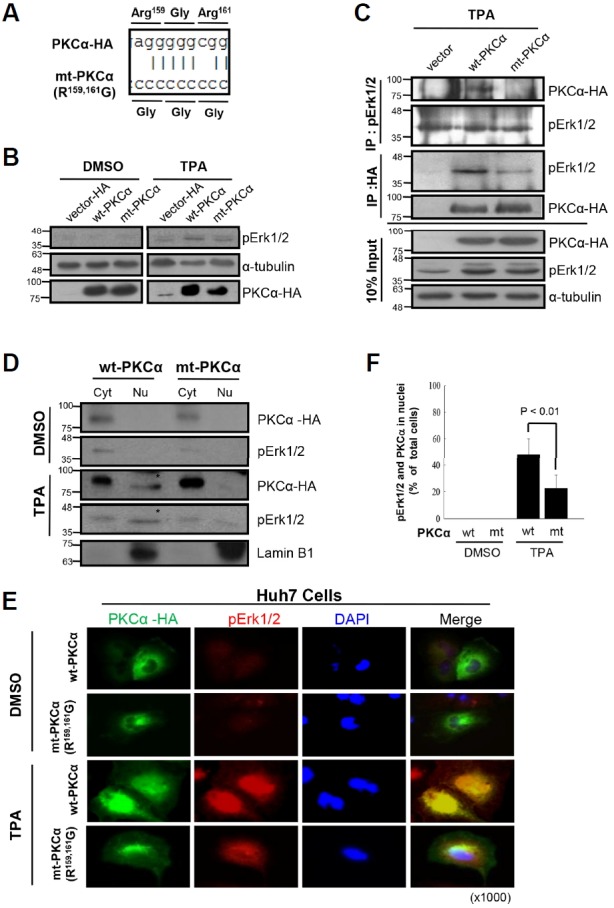

Both regulatory and catalytic domains of wild-type PKCα are required for pErk1/2 translocation to the nucleus in senescent cells after TPA treatment

The PKCα domains that interact with pErk1/2, were investigated in Huh7 cells, and the potential MAPK docking motifs within the PKCα molecule were predicted by computer simulation. Using site-specific mutation analysis, PKCα mutant constructs mt(R159,161G)-PKCα, kinase-dead PKCα, constitutively active PKCα, and wild-type (wt) PKCα were prepared (Supplementary Fig. S3A). All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing analysis (Fig. 3A). Confocal microscopy showed that each transfected construct significantly increased PKCα fluorescence in the particulate fraction of TPA-treated Huh7 cells; however, Erk1/2 activation and translocation only occurred in cells transfected with wt-PKCα. These data suggested that PKCα kinase activity and the regulatory domain were required for pErk1/2 translocation. This possibility was confirmed by ICC and reciprocal IP analyses (Supplementary Fig. S3B; Figs. 3B and 3C). The importance of the pErk1/2 docking motif within the PKCα regulatory domain was further evaluated using cell fractionation and IB analyses (Fig. 3D) and ICC after transfection of Huh7 cells with PKCα constructs (Fig. 3E). Both wt-PKCα and mt (R159,161G)-PKCα activated Erk1/2 following TPA stimulation; however, pErk1/2 and PKCα nuclear translocation were reduced by 60% in the mt(R159,161G)-PKCα expressing cells as compared with that in wt-PKCα expressing cells (Fig. 3F). These results indicate that TPA-induced Ekr1/2 phosphorylation was regulated by the PKCα catalytic domain, whereas pErk1/2 nuclear translocation required a PKCα regulatory domain containing wild-type R159 and 161 residues.

Fig. 3.

Both regulatory and catalytic domains of wt-PKCα are required for pErk1/2 translocation to nuclei in response to TPA. (A) To evaluate the effect of MAPK docking motif of PKCα on the pErk1/2 translocation, site-directed mutagenesis was employed; therefore, R159 and R161 residues were double-mutated to glycine, and the mt(R159,161G)-PKCα was confirmed by DNA sequencing. (B) IB analysis. To evaluate in vivo effect of PKCα on Erk1/2 phosphorylation, Huh7 cells were transiently transfected with wt-PKCα (PKCα-HA), mt(R159,161G)-PKCα or vector control (pcDNA3-HA) for 48 h, and then treated with either TPA or DMSO for 30 min before subjected to IB analysis. In vivo expressions of wt-PKCα and mt(R159,161G)-PKCα were confirmed by anti-HA antibody. Note mutation-independent phosphorylation of Erk1/2 by overexpressed PKCα in response to TPA. (C) Co-IP and IB analyses. To explore the effect of PKCα mutation at R159,161 residue on the interaction with pErk1/2, co-IP with anti-pErk1/2 and anti-HA antibodies were performed. Note significant reduction of pErk1/2 interaction with mt-PKCα than that of the wt-PKCα after TPA treatment, indicating the role of R159,161 residue in the interaction with pErk1/2. (D) IB analyses showing co-translocation of wt-PKCα, but not mt-PKCα, with pErk1/2 into nuclear fractions. Huh7 cells transfected with either wt-PKCα or mt-PKCα were treated with DMSO (0.01%) or TPA (50 ng/ml) for 30 min and then the fractions were subjected to IB analyses. Note the expressions of PKCα and pErk1/2 in the nuclear fraction of wt-PKCα, but not mt-PKCα, transfected cells. (E) Confocal microscope findings revealing co-translocation of pErk1/2 with wt-PKCα in Huh7 cells. Note partially reduced translocation of pErk1/2 in the mt-PKCα expresser compared with the wt-PKCα after TPA treatment. However, there is no significant translocation by DMSO treatment. (F) To confirm the effect of mt(R159,161G)-PKCα on the TPA-induced pErk1/2 translocation, ICC was performed with anti-pErk1/2 and anti-PKCα antibodies and counted the cells with nuclear pErk1/2 and PKCα; TPA-induced pErk1/2 translocation was significantly reduced by overexpression of mt(R159,161G)-PKCα compared with that of the wt-PKCα (p < 0.01). The data further support the role of regulatory domain of PKCα as a MAPK docking motif and the effect of their interaction on the nuclear translocation of pErk1/2. Data represent means ± SD after two independent experiments with duplicates.

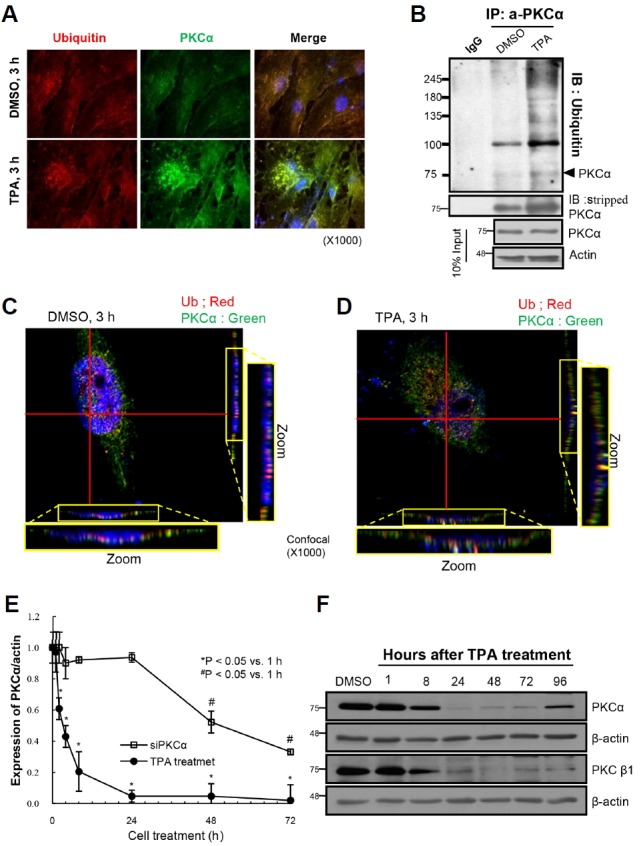

TPA rapidly degrades PKCα in senescent cell nuclei, and its regeneration is a delayed response

To characterize TPA-mediated PKCα downregulation in the senescent cell nuclei, old HDF cells were subjected to ICC using an anti-ubiquitin antibody. Under immunofluorescence microscope, ubiquitin and PKCα were found to be co-localized in the nuclei of TPA-treated cells (Fig. 4A) together with an increase in PKCα-ubiquitin ladders following cell treatment with MG132 (Fig. 4B). To further evaluate ubiquitin-mediated PKCα degradation in the cell nucleus, a Z-stack analysis was performed and viewed under confocal microscope. The presence of ubiquitin and PKCα was further confirmed by merged fluorescence in the TPA-treated cell nuclei (Fig. 4D) but not in the DMSO-treated cell nuclei (Fig. 4C). Therefore, we tested the kinetics of PKCα degradation in old HDF cells using either transfection with siPKCα or TPA treatment. As shown in Fig. 4E, the loss of PKCα expression was much faster after TPA treatment than after siPKCα transfection. This observation agrees with our previous report that old HDF cell proliferation is higher after TPA treatment than after siRNA transfection (Lee et al., 2015). Moreover, in these cells, the temporal changes in PKCα expression after TPA treatment for 8 h and 24 h (Fig. 4F) align with the morphologic and cytoskeletal changes observed after 8 h and 20 h of TPA treatment (Fig. 3 in Kwak et al., 2004). The partial regeneration of PKCα expression was observed at 96 h after a single treatment with TPA (Fig. 4F), indicating that PKCα regeneration is a delayed event as opposed to its very rapid degradation after initial TPA treatment. Collectively, these data strongly imply that PKCα downregulation allows senescent cells to undergo a senescence process reversal.

Fig. 4.

TPA rapidly degrades PKCα in nuclei of senescent cells, whereas its regeneration is so delayed. To examine the fate of PKCα after TPA stimulation in nuclei of senescent cells, ICC and IP-IB analyses were performed in the presence and absence of proteasome inhibitor, MG132. (A) TPA treatment significantly increased fluorescence of PKCα in the nuclei of senescent HDF cells in 3 h, indicating nuclear translocation of PKCα in the cells. In addition, the fluorescence derived from ubiquitin and PKCα was co-localized in the nuclei of the cells. (B) IP with anti-PKCα antibody and IB with anti-ubiquitin antibody showed polyubiquitination of PKCα after TPA + MG132 treatment as compared with that of the DMSO + MG132 treatment (upper panel) along with the slight accumulation of PKCα protein in the TPA + MG132 treated cells than the control (middle panel). The 10% input shows equal loading of the proteins for IP analysis (lower panels). (C) Confocal microscope findings revealing the separate location of PKCα and ubiquitin molecules in the nuclei of HDF cells in 3 h of DMSO treatment. However, TPA treatment induced co-translocation of PKCα and ubiquitin molecules in nuclei of the cells treated with TPA for 3 h (D), when scrutinized by Z-section. Note the red (Ub) and the green (PKCα) dots in the cells treated with DMSO, whereas the dots were co-localized upon treatment of HDF cells with TPA. (E) To investigate the kinetic changes of PKCα degradation by either TPA or siRNAs, old HDF cells were harvested at the indicated times and then the degree of PKCα expression was measured by IB analyses. Expressions of PKCα relative to that of the 0 h were calculated, and then plotted against hours of cell treatment. PKCα expression was persistent until 24 h after siPKCα transfection, whereas it was significantly reduced in 2 h of TPA treatment. The rapid degradation of PKCα in response to TPA was presented as the means ± SD of the 4 independent experiments and the kinetic changes of PKCα after siPKCα transfection was presented as the means ± SD of 3 independent experiments. Note significant difference of the PKCα kinetics induced by TPA treatment and by siPKCα transfection. (F) Immunoblot analyses showing the degradation and regeneration of PKC isozymes after single treatment of old HDF cells with TPA. Note significant downregulation of PKCα and PKCβ1 in 8 h and the complete lost in 24 h until 72 h. PKCα was regenerated in 96 h of TPA single treatment.

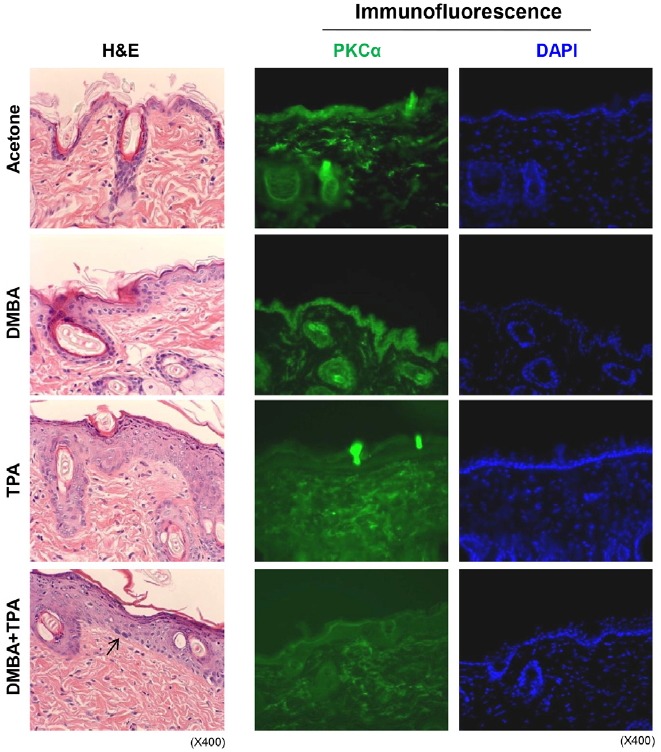

PKCα degradation accompanies epidermal proliferation in CD1 mice in response to repetitive TPA treatment

To confirm our hypothesis that TPA-induced degradation of PKCα might stimulate proliferation and induce senescence process reversal in senescent cells and that similar events may also occur during the promotion stage of carcinogenesis, CD-1 mice were subjected to DMBA initiation and subsequent topical applications of TPA (twice/week) for 2 weeks. Excised skin tissues were examined by immunohistochemistry and IF analyses (Fig. 5). After vehicle treatment and a DMBA single treatment, no proliferation was observed in the basal layer of the skin epidermis by hematoxylin and eosin staining. However, repetitive TPA treatment induced acanthosis of the epidermis and hair follicles independent of DMBA initiation. Treatment with DMBA plus TPA induced the formation of abnormal cells with hyperchromatic nuclei (arrow) in the basal layer. Labeling with an anti-PKCα antibody followed by immunofluorescent staining of serial tissue sections revealed a loss of PKCα expression along with increased cell proliferation in the epidermis of TPA-treated mice. The loss of PKCα expression in the epidermis persisted for 20 weeks with repetitive treatment (data not shown). These in vivo data strongly support our assumption that the loss of PKCα expression initiates cell proliferation independent of carcinogen-induced initiation, implying that the senescent cells that contain DNA segments with chromatin alterations reinforcing senescence (Rodier et al., 2011) might be more susceptible to both carcinogenesis and reverse senescence phenomenon.

Fig. 5.

Degradation of PKCα expression accompanies with epidermal proliferation in CD1 mice in response to repetitive TPA treatment. In order to evaluate in vivo effect of TPA on the loss of PKCα expression and subsequent regulation of cell proliferation, immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence analyses were employed in CD1 male mice (9 week-old) by using topical treatment with TPA for 2 weeks (twice/week) with or without DMBA pretreatment on the back skin once. Mice were sacrificed in 3 days of the final treatment with TPA. (A) H&E staining (x400): Acetone treated mouse skin shows one or two layered epidermis. DMBA single treated skin shows two or three layered epidermis. TPA treated mouse skin shows marked acanthosis of epidermis and hair follicles. DMBA + TPA treated mouse skin shows marked acanthosis with hyperchromatic nuclei in the basal cell layer (arrow). (B) Immunofluorescence staining: PKCα is expressed in the epidermis and hair follicles of the acetone and the DMBA alone treated CD1 mice, whereas it was focally expressed in dermis of the groups. On the other hand, PKCα expression was significantly lost in the epidermis and hair follicles of the TPA treated and the DMBA + TPA treated mice skin. The fluorescence was rather nonspecifically diffuse in the dermis. DAPI shows nuclei present in the epidermis and hair follicles.

RNA sequence analyses support the senescence reversal program observed in old HDF cells after TPA treatment

To confirm the senescence reversal in old HDF cells in response to TPA, RNA sequence analysis was performed using mRNAs isolated from old HDF cells treated with TPA for 8 h and 24 h, and cells treated with DMSO as a control. The most variable 1,000 genes were subjected to unsupervised clustering, and the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the 2 selected conditions were analyzed using Cuffdiff software, with significance thresholds of p < 0.001 or a false discovery rate < 0.05 after multiple corrections. A heat map was generated by hierarchical clustering of the up- and down-regulated DEG values of 222 out of the 1000 genes analyzed (Supplementary Fig. S4A). The changes in gene expression observed at TPA-8 h and TPA-24 h treatment relative to DMSO treatment (0 h) are presented as a gene ontology analysis in Tables 2 and 3, respectively. All data strongly supported the occurrence of cell cycle progression, along with the morphological and cytoskeletal changes in senescent cells linked with reduced focal adhesion to extracellular matrix. Thus, the flat and large senescent cells began to look like younger cells. The change was clearer on the heat map generated by the hierarchical clustering of 53 DEGs (Supplementary Fig. S4B).

Table 2.

Gene ontology analyses of the significantly up-regulated genes in the HDF old cells treated with TPA for 8 h and 24 h, based on the DMSO control, obtained by RNA sequencing.

| Term | Count | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPA 8 h vs. 0 h in old HDFs (up-regulation) | GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0042127∼regulation of cell proliferation | 13 | 0.002404 |

| GO:0008284∼positive regulation of cell proliferation | 8 | 0.011902 | ||

| GO:0051726∼regulation of cell cycle | 6 | 0.048291 | ||

| GO:0040007∼growth | 5 | 0.02407 | ||

| GO:0010628∼positive regulation of gene expression | 8 | 0.058907 | ||

| GO:0045893∼positive regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent | 7 | 0.066019 | ||

| GO:0031328∼positive regulation of cellular biosynthetic process | 12 | 0.002474 | ||

| GO:0043069∼negative regulation of programmed cell death | 10 | 2.86E-04 | ||

| GO:0006916∼anti-apoptosis | 7 | 0.001457 | ||

| GO:0006469∼negative regulation of protein kinase activity | 7 | 1.31E-05 | ||

| GO:0043407∼negative regulation of MAP kinase activity | 5 | 6.07E-05 | ||

| GO:0006954∼inflammatory response | 8 | 0.003291 | ||

| GO:0006955∼immune response | 11 | 0.007953 | ||

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005125∼cytokine activity | 10 | 2.54E-04 | |

| GO:0008083∼growth factor activity | 7 | 0.055948 | ||

| GO:0004175∼endopeptidase activity | 8 | 0.639307 | ||

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005615∼extracellular space | 17 | 1.17E-06 | |

| GO:0044421∼extracellular region part | 19 | 5.18E-06 | ||

| GO:0005576∼extracellular region | 27 | 2.46E-05 | ||

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04060:Cytokine-cytokine receptor interaction | 9 | 2.51E-04 | |

| hsa04630:Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 6 | 0.003358 | ||

| TPA 24 h vs. 0 h in old HDFs (up-regulation) | GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0006874∼cellular calcium ion homeostasis | 4 | 0.021492 |

| GO:0008544∼epidermis development | 4 | 0.021799 | ||

| GO:0006875∼cellular metal ion homeostasis | 4 | 0.025678 | ||

| GO:0030005∼cellular di-, tri-valent inorganic cation homeostasis | 4 | 0.037309 | ||

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005125∼cytokine activity | 4 | 0.028158 | |

| GO:0004857∼enzyme inhibitor activity | 6 | 0.002098 | ||

| GO:0030414∼peptidase inhibitor activity | 5 | 0.001745 | ||

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0005576∼extracellular region | 24 | 1.65E-07 | |

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04630:Jak-STAT signaling pathway | 3 | 0.054783 |

Table 3.

Gene ontology analyses of the significantly down-regulated genes in the HDF old cells treated with TPA for 8 h and 24 h, based on the DMSO control, obtained by RNA sequencing.

| Term | Count | P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TPA 8 h vs. 0 h in old HDFs (down-regulation) | GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0048705∼skeletal system morphogenesis | 3 | 0.010597 |

| GO:0006493∼protein amino acid O-linked glycosylation | 2 | 0.034557 | ||

| GO:0010324∼membrane invagination | 3 | 0.037542 | ||

| GO:0006897∼endocytosis | 3 | 0.037542 | ||

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0030247∼polysaccharide binding | 4 | 0.001861 | |

| GO:0001871∼pattern binding | 4 | 0.001861 | ||

| GO:0008201∼heparin binding | 3 | 0.011865 | ||

| GO:0030246∼carbohydrate binding | 4 | 0.018571 | ||

| GO:0005539∼glycosaminoglycan binding | 3 | 0.021203 | ||

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0044421∼extracellular region part | 5 | 0.041449 | |

| BIOCARTA_Pathway | h_LDLpathway:Low-density lipoprotein (LDL) pathway during atherogenesis | 2 | 0.004175 | |

| TPA 24 h vs. 0 h in old HDFs (down-regulation) | GOTERM_BP_FAT | GO:0006873∼cellular ion homeostasis | 6 | 0.008503 |

| GO:0055082∼cellular chemical homeostasis | 6 | 0.009074 | ||

| GO:0007010∼cytoskeleton organization | 6 | 0.015732 | ||

| GO:0007155∼cell adhesion | 7 | 0.030208 | ||

| GO:0022610∼biological adhesion | 7 | 0.030391 | ||

| GOTERM_MF_FAT | GO:0005198∼structural molecule activity | 8 | 0.003887 | |

| GO:0005509∼calcium ion binding | 9 | 0.00835 | ||

| GO:0005516∼calmodulin binding | 4 | 0.010365 | ||

| GO:0046873∼metal ion transmembrane transporter activity | 5 | 0.021059 | ||

| GO:0015267∼channel activity | 5 | 0.043363 | ||

| GO:0022803∼passive transmembrane transporter activity | 5 | 0.043687 | ||

| GOTERM_CC_FAT | GO:0031012∼extracellular matrix | 6 | 0.006373 | |

| GO:0005626∼insoluble fraction | 9 | 0.00715 | ||

| GO:0000267∼cell fraction | 10 | 0.010283 | ||

| GO:0005624∼membrane fraction | 8 | 0.019534 | ||

| GO:0005911∼cell-cell junction | 4 | 0.027414 | ||

| GO:0042383∼sarcolemma | 3 | 0.022226 | ||

| KEGG_PATHWAY | hsa04514:Cell adhesion molecules (CAMs) | 4 | 0.008906 |

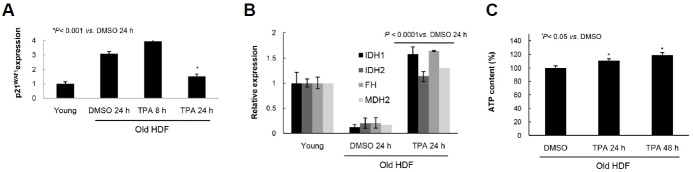

TPA-induced senescence reversal reduces senescence marker expression and increases mitochondrial metabolism and oxidative phosphorylation

To assess whether the TPA-induced changes in senescent cell morphology and gene expression were accompanied by changes in cell physiology and metabolism, p21WAF1 expression was measured by real-time PCR analysis after TPA treatment. As shown in Fig. 6A, the level was significantly reduced 24 h after TPA treatment. In addition, the mitochondrial citric acid cycle-regulating enzymes IDH, IDH2, FH, and MDH2 were all markedly increased in the old HDF cells after 24 h of TPA stimulation (Fig. 6B). Finally, mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation was also significantly increased along with ATP generation after TPA treatment but not after DMSO treatment (Fig. 6C). These data indicate that reverse senescence includes not only changes in gene expression and cell physiology, but also in energy metabolism in response to TPA stimulation.

Fig. 6.

TPA-induced reversal of senescence changes expressions of molecular markers and mitochondrial respiration. (A) Real time PCR analysis showing the significant inhibition of p21WAF1 expression in HDF old cells in 24 h of TPA treatment. (B) Marked increase of the mitochondrial enzymes regulating TCA cycle in 24 h of TPA treatment in HDF old cells. Note significant increases of the isocitrate dehyrogenase 1 and 2 (IDH, IDH2), mitochondrial fumarate hydratase (FH), and mitochondrial isoform 1 precursor of malate dehydrogenase (MDH2). (C) Increase of ATP level in HDF old cells in response to TPA treatment compared with that of the DMSO treatment.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that PKC is a receptor for tumor-promoting phorbol esters (Kikkawa et al., 1983) that translocates from the cell cytosol to particulate fractions upon stimulation (Buchner, 1995). However, the fate and the role of PKC isozyme nuclear translocation during cell senescence and carcinogenesis remain largely unknown. In the present study, we investigated the differential functions of PKCα and PKCβ1, with a focused on the senescence reversal in old HDF cells. Our results confirmed that the loss of PKCα in epithelial cells is also observed in in vivo carcinogenesis. In fact, TPA-activated PKCβ1 dissociates SA-pErk1/2 from PEA-15 by phosphorylating PEA-15 at S104, which releases pErk1/2 to interact with the regulatory domain of wt-PKCα prior to nuclear translocation. PKCα is rapidly ubiquitinated and degraded in the cell nucleus prior to pErk1/2 inactivation; thus, freeing pErk1/2 to participate in the cell proliferation program (Fig. 7). As previously reported, there is no difference in the level of PKCα and PKCβ1 expression between the young and senescent HDF cells; however, kinase activity is significantly greater in the senescent cells than in the young cells (Kim and Lim, 2009). Also, there is a substantial accumulation of ROS within the senescent cells relative to the young cells (Kim et al., 2003). From a mechanistic viewpoint, the contributions of the nuclear ubiquitination of PKCα to the regulation of senescence reversal may be explained in part by our previous report that the activated and abundant concentrations of PKCs might induce Erk1/2 phosphorylation and subsequent activation of SP1 at residue S59, increasing p21WAF1 transcription during the senescence process (Fig 7A). Indeed, tethering pErk1/2 to PEA-15 in the cytoplasm maintains senescence until the degradation of PKCα following TPA treatment (Lee et al., 2015). Treating HDF cells once with TPA significantly down-regulates PKCα concentrations between 8 and 96 h after exposure (Figs. 4E and 4F). This process indicates that TPA-induced nuclear translocation of PKCα and SA-pErk1/2 and subsequent PKCα degradation in the nucleus might be essential for the reversal of senescence, thus representing a barrier that must be overcome for malignant transformation of mammalian cells (Campisi, 2005; Wright and Shay, 2001). It is established that HDF cells, which were derived from the foreskin, do not express the p16INK4a gene and that the absence of the p16INK4a/pRB signaling pathway allows senescence reversal in HDF cells (Beausejour et al., 2003). Thus, cytoplasmic sequestration of pErk1/2 by PEA-15 might represent an important mechanism for maintaining cellular senescence and resistance to mitogenic signals in senescent HDF cells (Lee et al., 2015). The PKCβ1-mediated release of pErk1/2 from PEA-15 and subsequent PKCα degradation shown in the present study might be a prerequisite for senescence reversal and epidermal proliferation in vivo (Fig. 7B). The in vivo and in vitro phosphorylation of PEA-15 at S104 by PKCβ1 was confirmed by knockdown of PKCβ1 expression with siRNA transfection and kinase assay-IB analysis (Fig. 2). Although PKCα also phosphorylates GST-PEA-15 at S104 residue in vitro (data not shown), the discrepancy between results might be because of the direct phosphorylation of GST by PKCα (Rodriguez et al., 2005) and the higher affinity of PKCβ1 for PEA-15 S104 than for PKCα (Nishikawa et al., 1997). Despite the translocation of activated PKC isozymes into various cell particulate fractions, the present results clearly indicate that translocated PKCα molecules are degraded in the old HDF cell nuclei upon TPA treatment, triggering further reactions that reverse senescence. This notion is well supported by our previous reports demonstrating that knockdown of PKCα expression (Kim and Lim, 2009) or treatment with TPA significantly induces the proliferation of old HDF cells.

Fig. 7.

PKCα and PKCβ1 plays differentially in the nuclear translocation of pErk1/2 upon TPA treatment which regulates reversal of senescence phenotypes. (A) During replicative senescence, highly accumulated ROS triggers activation of PKC isozymes without their protein expression, which leads to the induction of p21WAF1 ex-pression through the activations of Erk1/2 and Sp1 transcription factor. However, knockdown of PKCα isoform by transfection with siRNAs reverses senescence program and rather induces cell proliferation after overcome the G1/S arrest. The diagram has been reported by the authors (Kim and Lim, 2009). (B) PKCβ1 activated by TPA regulates in vivo phosphorylation of PEA-15 at S104 residue, which triggers dissociation of SA-pErk1/2 (Senescence Associated-pErk1/2) sequestered in cytoplasm from PEA-15. TPA-stimulated PKCα binds to SA-pErk1/2 released from PEA-15pS104 and then translocated to nuclei of the cells. In the nucleus, pErk1/2 is released from PKCα after its ubiquitination, which triggers a series of gene expression that participates in reversal of the large and flat senescence cells to the actively growing young cells. TPA-induced series of gene expression can be shared by tumor promoting response in skin, which resulted in epidermal proliferation.

Based on our transfection analyses, the PKCα catalytic domain is sufficient for Erk1/2 activation in response to TPA (Supplementary Fig. S3B). However, TPA-induced pErk1/2 translocation requires the wt-PKCα MAPK interaction domain (Figs. 3D–3F), indicating that PKCα functions in pErk1/2 nuclear trans-location and phosphorylation. Indeed, PKCα, PKCβ1, and PEA-15 have independent roles in facilitating the nuclear trans-location of SA-pErk1/2, which induces senescence reversal upon TPA stimulation. The basal activity of PKCα and PKCβ1 is much higher in senescent cells than in young cells despite there being no difference in the levels of protein expression (Kim and Lim, 2009), with conditions maintained in a steady state in the senescent cells. We speculate that PKC isozyme stimulation by TPA and PKCα degradation in senescent cells may represent events that prime the cells for senescence reversal through pErk1/2 activation in senescent cell nuclei. Thus, the delayed regeneration of PKCα after TPA treatment (Fig. 4F) might provide an environment to stimulate cell proliferation, facilitate old cells to overcome an active senescence program, and undergo malignant transformation upon carcinogen initiation along with epidermal proliferation (Fig. 5). Indeed, the reversal of cellular senescence induced by TPA was well supported by the significant recovery of mitochondrial metabolism and ATP generation after 24 h of TPA treatment as compared with that in the DMSO control (Fig. 6).

Legends for supplementary figures

Acknowledgments

Authors greatly appreciate careful reading of this manuscript by Prof. Woon Ki Paik. This work was supported by the National Research Foundation (NRF) grant (No. 2013R1A2A2A 01005056) funded by the Korean government (MSIP), and the grants of the Korea Health technology R&D Project, Ministry of Health & Welfare, Republic of Korea (A121725) and the National R&D Program for Cancer Control, Ministry for Health and Welfare, Republic of Korea (131280).

Footnotes

Note: Supplementary information is available on the Molecules and Cells website (www.molcells.org).

REFERENCES

- Abel E.L., Angel J.M., Kiguchi K., DiGiovanni J. Multistage chemical carcinogenesis in mouse skin: fundamentals and applications. Nat. Protoc. 2009;4:1350–1362. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2009.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alessandrini A., Crews C.M., Erikson R.L. Phorbol ester stimulates a protein-tyrosine/threonine kinase that phosphorylates and activates the Erk-1 gene product. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1992;89:8200–8204. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.17.8200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexandropoulos K., Qureshi S.A., Foster D.A. Ha-Ras functions downstream from protein kinase C in v-Fps-induced gene expression mediated by TPA response elements. Oncogene. 1993;8:803–807. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo H., Danziger N., Cordier J., Glowinski J., Chneiweiss H. Characterization of PEA-15, a major substrate for protein kinase C in astrocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1993;268:5911–5920. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashendel C.L. The phorbol ester receptor: a phospholipid-regulated protein kinase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1985;822:219–242. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(85)90009-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardwell A.J., Flatauer L.J., Matsukuma K., Thorner J., Bardwell L. A conserved docking site in MEKs mediates high-affinity binding to MAP kinases and cooperates with a scaffold protein to enhance signal transmission. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:10374–10386. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010271200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beausejour C.M., Krtolica A., Galimi F., Narita M., Lowe S.W., Yaswen P., Campisi J. Reversal of human cellular senescence: roles of the p53 and p16 pathways. EMBO J. 2003;22:4212–4222. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchner K. Protein kinase C in the transduction of signals toward and within the cell nucleus. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995;228:211–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campisi J. Senescent cells, tumor suppression, and organismal aging: good citizens, bad neighbors. Cell. 2005;120:513–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Camps M., Nichols A., Gillieron C., Antonsson B., Muda M., Chabert C., Boschert U., Arkinstall S. Catalytic activation of the phosphatase MKP-3 by ERK2 mitogen-activated protein kinase. Science. 1998;280:1262–1265. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5367.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candas D., Fan M., Nantajit D., Vaughan A.T., Murley J.S., Woloschak G.E., Grdina D.J., Li J.J. CyclinB1/Cdk1 phosphorylates mitochondrial antioxidant MnSOD in cell adaptive response to radiation stress. J. Mol. Cell Biol. 2013;5:166–175. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjs062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang L., Karin M. Mammalian MAP kinase signalling cascades. Nature. 2001;410:37–40. doi: 10.1038/35065000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen R.H., Sarnecki C., Blenis J. Nuclear localization and regulation of erk- and rsk-encoded protein kinases. Mol. Cell Biol. 1992;12:915–927. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.3.915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clemens M.J., Trayner I., Menaya J. The role of protein kinase C isoenzymes in the regulation of cell proliferation and differentiation. J. Cell Sci. 1992;103:881–887. doi: 10.1242/jcs.103.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collado M., Gil J., Efeyan A., Guerra C., Schuhmacher A.J., Barradas M., Benguria A., Zaballos A., Flores J.M., Barbacid M., et al. Tumour biology: senescence in premalignant tumours. Nature. 2005;436:642. doi: 10.1038/436642a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cruzalegui F.H., Cano E., Treisman R. ERK activation induces phosphorylation of Elk-1 at multiple S/T-P motifs to high stoichiometry. Oncogene. 1999;18:7948–7957. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devanand P., Kim S.I., Choi Y.W., Sheen S.S., Yim H., Ryu M.S., Kim S.J., Kim W.J., Lim I.K. Inhibition of bladder cancer invasion by Sp1-mediated BTG2 expression via inhibition of DNA methyltransferase 1. FEBS J. 2014;281:5581–5601. doi: 10.1111/febs.13099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaken S. Protein kinase C and tumor promoters. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 1990;2:192–197. doi: 10.1016/0955-0674(90)90006-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazi J.U., Soh J.W. Induction of the nuclear protooncogene c-fos by the phorbol ester TPA and v-H-Ras. Mol. Cells. 2008;26:462–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikkawa U., Takai Y., Tanaka Y., Miyake R., Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C as a possible receptor protein of tumor-promoting phorbol esters. J. Biol. Chem. 1983;258:11442–11445. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Lim I.K. Phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated protein kinases 1 and 2 phosphorylate Sp1 on serine 59 and regulate cellular senescence via transcription of p21Sdi1/Cip1/Waf1. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:15475–15486. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808734200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H.S., Song M.C., Kwak I.H., Park T.J., Lim I.K. Constitutive induction of p-Erk1/2 accompanied by reduced activities of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A and MKP3 due to reactive oxygen species during cellular senescence. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:37497–37510. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M211739200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krueger J., Chou F.L., Glading A., Schaefer E., Ginsberg M.H. Phosphorylation of phosphoprotein enriched in astrocytes (PEA-15) regulates extracellular signal-regulated kinase-dependent transcription and cell proliferation. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2005;16:3552–3561. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E04-11-1007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak I.H., Kim H.S., Choi O.R., Ryu M.S., Lim I.K. Nuclear accumulation of globular actin as a cellular senescence marker. Cancer Res. 2004;64:572–580. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y.Y., Kim H.S., Lim I.K. Downregulation of PEA-15 reverses G1 arrest, and nuclear and chromatin changes of senescence phenotype via pErk1/2 translocation to nuclei. Cell. Signal. 2015;27:1102–1109. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2015.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lim I.K., Won Hong K., Kwak I.H., Yoon G., Park S.C. Cytoplasmic retention of p-Erk1/2 and nuclear accumulation of actin proteins during cellular senescence in human diploid fibroblasts. Mech. Ageing Dev. 2000;119:113–130. doi: 10.1016/s0047-6374(00)00167-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Z., Liu D., Hornia A., Devonish W., Pagano M., Foster D.A. Activation of protein kinase C triggers its ubiquitination and degradation. Mol. Cell Biol. 1998;18:839–845. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menice C.B., Hulvershorn J., Adam L.P., Wang C.A., Morgan K.G. Calponin and mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling in differentiated vascular smooth muscle. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25157–25161. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishikawa K., Toker A., Johannes F.J., Songyang Z., Cantley L.C. Determination of the specific substrate sequence motifs of protein kinase C isozymes. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:952–960. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Intracellular signaling by hydrolysis of phospholipids and activation of protein kinase C. Science. 1992;258:607–614. doi: 10.1126/science.1411571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. Protein kinase C and lipid signaling for sustained cellular responses. FASEB J. 1995;9:484–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliva J.L., Caino M.C., Senderowicz A.M., Kazanietz M.G. S-Phase-specific activation of PKC alpha induces senescence in non-small cell lung cancer cells. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:5466–5476. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707576200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearson G., Robinson F., Beers Gibson T., Xu B.E., Karandikar M., Berman K., Cobb M.H. Mitogen-activated protein (MAP) kinase pathways: regulation and physiological functions. Endocr. Rev. 2001;22:153–183. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.2.0428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renganathan H., Vaidyanathan H., Knapinska A., Ramos J.W. Phosphorylation of PEA-15 switches its binding specificity from ERK/MAPK to FADD. Biochem. J. 2005;390:729–735. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodier F., Munoz D.P., Teachenor R., Chu V., Le O., Bhaumik D., Coppe J.P., Campeau E., Beausejour C.M., Kim S.H., et al. DNA-SCARS: distinct nuclear structures that sustain damage-induced senescence growth arrest and inflammatory cytokine secretion. J. Cell Sci. 2011;124:68–81. doi: 10.1242/jcs.071340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez P., Mitton B., Kranias E.G. Phosphorylation of glutathione-S-transferase by protein kinase C-alpha implications for affinity-tag purification. Biotechnol Lett. 2005;27:1869–1873. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-3895-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S.M., DeMarco M., D'Arcangelo G., Halegoua S., Brugge J.S. Ras is essential for nerve growth factor- and phorbol ester-induced tyrosine phosphorylation of MAP kinases. Cell. 1992;68:1031–1040. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90075-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaidyanathan H., Opoku-Ansah J., Pastorino S., Renganathan H., Matter M.L., Ramos J.W. ERK MAP kinase is targeted to RSK2 by the phosphoprotein PEA-15. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:19837–19842. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704514104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vernier M., Bourdeau V., Gaumont-Leclerc M.F., Moiseeva O., Begin V., Saad F., Mes-Masson A.M., Ferbeyre G. Regulation of E2Fs and senescence by PML nuclear bodies. Genes Dev. 2011;25:41–50. doi: 10.1101/gad.1975111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen-Sheng W., Jun-Ming H. Activation of protein kinase C alpha is required for TPA-triggered ERK (MAPK) signaling and growth inhibition of human hepatoma cell HepG2. J. Biomed. Sci. 2005;12:289–296. doi: 10.1007/s11373-005-1210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright W.E., Shay J.W. Cellular senescence as a tumor-protection mechanism: the essential role of counting. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 2001;11:98–103. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(00)00163-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S.H., Yates P.R., Whitmarsh A.J., Davis R.J., Sharrocks A.D. The Elk-1 ETS-domain transcription factor contains a mitogen-activated protein kinase targeting motif. Mol. Cell Biol. 1998;18:710–720. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.2.710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.