Abstract

Studies of varicella-zoster virus (VZV) tropism for T cells support their role in viral transport to the skin during primary infection. Multiparametric single-cell mass cytometry demonstrates that, instead of preferentially infecting skin-homing T cells, VZV alters cell signaling and remodels surface proteins to enhance T cell skin trafficking. Viral proteins dispensable in skin, such as that encoded by open reading frame 66, are necessary in T cells. Interference with VZV T cell tropism may offer novel strategies for drug and vaccine design.

INTRODUCTION

Varicella-zoster virus (VZV) is a human alphaherpesvirus that causes varicella as the primary infection, while reactivation from latency in sensory ganglion neurons results in zoster. During primary infection with the virus, respiratory inoculation is followed by viremia and a vesicular rash. The possibility that VZV is a lymphotropic virus came from early evidence detecting VZV genomic DNA in peripheral blood mononuclear cells with lymphocytic morphology during acute varicella (1). Our model of VZV infection proposes that lymphoid tissues of the upper respiratory tract, including tonsils and other structures of Waldeyer's ring, provide an opportunity for VZV to infect T cells because respiratory epithelial cells, the presumed initial site of VZV replication, overlie and penetrate these tissues. Dendritic cells are also susceptible to VZV and may enhance viral transport to lymphoid tissues (2). Each of the widely distributed lesions of varicella is likely the result of viral transfer to the skin by a single infected T cell, as supported by the monomorphic genotypes of VZV isolates from skin lesions (3).

VZV infects differentiated primary human T cells.

Consistent with the proposed model, we found that VZV readily infects tonsil T cells in vitro (4). Furthermore, human CD4 and CD8 T cells within thymus/liver xenografts in SCID mice are highly susceptible to VZV and infectious virions are formed and released from T cells infected in vivo (5–7). Notably, VZV does not induce fusion between T cells, which is significantly different from the process of cell fusion and polykaryocyte formation that occurs in skin. To prove that T cells have the capacity for efficient viral transfer, VZV-infected T cells were injected into the circulation of SCID mice engrafted with human skin xenografts (8). T cells exited across the human capillary endothelial cells that form the microvasculature in skin xenografts within 24 h, and typical VZV skin lesions were observed over the subsequent 10 to 21 days, in keeping with the known varicella incubation period. Notably, the slow progression of lesion formation resulted from an unexpectedly vigorous innate immune response of skin epidermal cells. The VZV-positive tonsil T cells expressed CD69, a T cell activation marker, together with cutaneous leukocyte antigen (CLA) and chemokine receptor 4 (CCR4), markers that are associated with skin homing, and phorbol ester-mediated stimulation of T cells promoted susceptibility of the cells to VZV, indicating a role for T cell activation in supporting VZV replication. Thus, these studies broadly suggested that VZV infects tonsil T cells with properties that promote trafficking to the skin, thereby enhancing the likely transfer of the virus to skin sites of replication and opportunities for VZV transmission to other susceptible hosts.

VZV remodels T cells during infection.

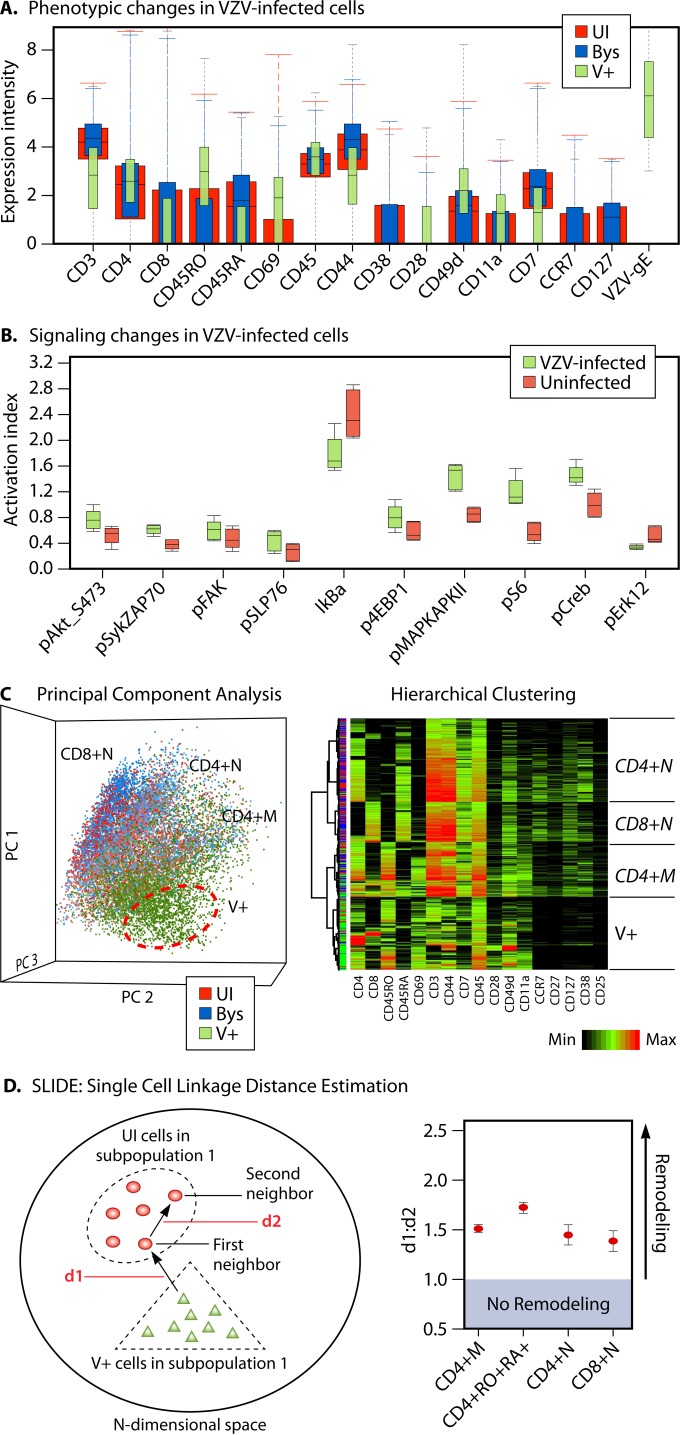

To better understand the molecular mechanisms underlying VZV T cell tropism, we adapted the novel method of single-cell mass spectrometry to study VZV takeover of T cells (9–12). In this first study examining virus-host cell interactions by this method, we simultaneously measured 40 parameters, including cell surface and signaling proteins from single cells by using metal isotope-labeled antibodies; time of flight mass cytometry (CyTOF) made it possible to quantify the expression of each protein in many thousands of VZV-infected and uninfected (UI) tonsil T cells (12). The proteome profile in VZV-infected cells was compared to that of UI T cells and bystander (Bys) T cells, as distinguished from virus-infected (V+) T cells, by VZV glycoprotein E expression. The data sets from millions of T cells were stringently analyzed by using various statistical and data analysis programs, including spanning tree progression analysis of density-normalized events (SPADE), principal-component analysis (PCA), hierarchical clustering, and single-cell linkage using distance estimation (SLIDE) (12). Strikingly, these experiments demanded a paradigm shift in our model of VZV pathogenesis because the data disproved our earlier theory that VZV preferentially infects CD4+ memory T cells with skin-homing characteristics in a one-step process. Instead, multiparametric single-cell analyses revealed that VZV actively remodels T cells into activated skin-homing infected T cells in a multistep process by inducing or altering (depending on the basal state of the cells) the expression of multiple intracellular phosphoproteins and cell surface proteins (Fig. 1A and B). We found that VZV orchestrates a continuum of changes in surface and intracellular proteins within heterogeneous naive and memory CD4 and CD8 T cell populations, regardless of their basal state, that cannot be detected by averaged measurements obtained by standard methods. Multiparametric analysis of single cells is also essential because there is no one “skin-homing” marker on human T cells that could be measured to prove this functional consequence of VZV infection; both enhanced expression and reduced expression of several surface proteins are needed to elicit a skin trafficking profile. Further, simultaneous measurement of multiple phosphoproteins along with surface proteins made it possible to show that VZV activates known T cell signaling pathways typically triggered through the T cell receptor binding to its cognate antigens, thereby modulating cell surface properties. As determined by robust reiterative statistical analysis of cell surface proteins, the infected T cells exhibited unique characteristics, which at the bulk level included downregulation of CD3, CD7, CD27, CD127, CD44, and CD38 and upregulation of CD69, CD279, CCR4, CLA, and CXCR5 (Fig. 1C). Intriguingly, the profile resembled that of cutaneous T cell lymphoma (CTCL) cells that also traffic to the skin and generate characteristic CTCL lesions (13). Since VZV infects 10 to 15% of T cells (in vitro), it was critical to determine if the uniqueness of the infected T cells stemmed from the preferential infection of a rare population of T cells or from remodeling of T cells, a novel single-cell statistical method, SLIDE, was designed to assess homogeneity between cells by measuring the absolute “distance” (based on combinatorial expression of surface markers) between each infected cell and its nearest neighbor UI cell. Determining the ratio of the distance between infected and UI T cells (d1) to the distance between closely related UI T cells (d2) revealed that a majority of the infected T cells exhibited a ratio of >1, indicating remodeling as a result of virus infection (Fig. 1D). The efficiency of remodeling observed in naive T cells was similar to that observed in VZV-infected memory T cells. While most programs for CyTOF data analysis use dimension reduction approaches coupled with visualization tools designed for large-scale data sets, SLIDE enables statistical analysis based on assessment of the profile of each single cell.

FIG 1.

VZV T cell tropism. High-dimensional multiparametric analysis of single T cells by mass cytometry revealed that VZV infection induces bidirectional changes in surface and intracellular signaling proteins, enhancing properties that promote trafficking of infected T cells to skin sites of replication and lesion formation (12). (A) Boxplots showing the expression intensity of multiple cell surface proteins that were measured simultaneously in UI (red), Bys (blue), and V+ (green) T cells. In contrast to the UI T cells that were cocultured with UI HELF, the Bys T cells were exposed to VZV during coculture but remained UI, as determined by VZV gE expression. The error bars indicate the distribution of the data, and the black line inside each box indicates the median value of expression intensity. (Republished from reference 12 with permission of the publisher.) (B) The boxplots shown denote the activation indexes (AIs) of the signaling proteins tested in VZV-infected T cells compared to the AI of UI T cells (n = 5). The AI was calculated as a product of the intensity. Changes in the AI of signaling proteins were determined in different T cell subpopulations; the boxplots show those observed in CD4 memory T cells. (C) PCA (Partek Genomics Suite software) of UI, Bys, and V+ T cells revealed that the UI and Bys cells were broadly distributed into three predominant subpopulations—CD4 memory (CD4+ M), CD4 naive (CD4+ N), and CD8 naive (CD8+ N) as indicated (left side), while the VZV-infected T cells formed a distinct cell cloud. The PCA data are shown as a scatterplot where each dot represents a cell belonging to the UI (red), Bys (blue), or V+ (green) group. (Republished from reference 11 with permission of the publisher.) Similar to the PCA data, hierarchical clustering (right side) also revealed three major subpopulations in the UI and Bys T cells, while the V+ cells clustered separately. In the heat map representation of the hierarchical clustering analysis, each row represents a cell and each column represents a protein. The intensity of expression of multiple proteins in a given cell can be visualized on the basis of the color scale; the dendrogram on the left indicates the distance or similarity between the cells (rows). (Republished from reference 12 with permission of the publisher.) (D) A schematic diagram of the SLIDE algorithm is shown (left) along with a remodeling summary plot (right) that denotes the average d1/d2 ratio (y axis) observed in four different T cell subpopulations (x axis). Changes in the expression of phenotypic markers were quantified by SLIDE in each of the different CD4 and CD8 memory and naive subpopulations to provide mathematical evidence for remodeling of T cells by VZV. SLIDE revealed that a majority of the infected cells were remodeled to exhibit a skin-homing profile, thereby allowing migration of the infected cells to the skin.

Viral determinants of VZV T cell tropism.

Evaluation of VZV recombinants with mutations of the viral genome that block expression or alter subdomains of viral proteins provides information about how viral determinants influence T cell infection, as summarized in Table 1. Of the VZV glycoproteins, gE is essential and is typically expressed as a heterodimer with gI; both gE and gI traffic to cell membranes and are virion envelope components. While amino acid residues 51 to 187 of gE are critical for infection of T cell xenografts in vivo, the cysteine-rich region between amino acids 208 and 236, necessary for gE-gI heterodimer formation, was dispensable for tonsil T cell infection. Although gE binds to the insulin-degrading enzyme (IDE), blocking gE-IDE binding does not affect T cell xenograft infection, indicating that this interaction does not mediate VZV T cell entry. The gE cytoplasmic domain has a YAGL endocytosis motif essential for replication, whereas the trans-Golgi network (TGN)-targeting motif AYRV and an “acid cluster” phosphorylation motif, SSTT, are not (14). Titers were lower, but infectious virus was recovered from most T cell xenografts infected with the AYRV mutant, indicating that correct TGN localization of gE contributed to but was not required for T cell tropism in vivo; SSTT residues were dispensable. When VZV gE-gI binding is prevented or gI is deleted, gE maturation and expression on plasma membranes are disrupted, VZV virions are not detected in post-Golgi compartments, and T cell xenograft infection is blocked (15).

TABLE 1.

Effects of selected mutations in viral proteins on VZV infection of tonsil T cells and T cell xenografts in the SCID mouse model

| Mutation | Tonsil T cells | T cell xenograftsa |

|---|---|---|

| Glycoproteins gE and gI | ||

| gE aab 51–187 (unique N terminus) | − | |

| Δcys (gI binding) | NLc | |

| gE aa 27–90 (IDE binding) | NL | ++ |

| gE AYRV (TGN targeting) | ± | |

| gE SSTT | + | |

| ΔgI | − | |

| Regulatory/tegument proteins | ||

| ORF47-C (C-terminal deletion) | − | |

| ORF47D-N (kinase motif mutation) | − | |

| ORF66S (stop codon mutant) | + | |

| ORF66 G102A (kinase domain) | ± | |

| Δ63 (single-copy deletion) | ++ | |

| ORF63 T171 (phosphorylation) | ++ | |

| ORF63 S181 (phosphorylation) | ++ | |

| ORF63 S185 (phosphorylation) | ++ | |

| ΔORF10 | ++ | |

| ΔORF11 | NL | |

| ΔORF12 | NL | |

| ΔORF10/11/12 | NL | |

| pOka | ++ | |

| vOka | ++ |

++, equal to intact VZV; ±, impaired; −, no replication.

aa, amino acids.

NL, normal compared to intact VZV.

As in other herpesviruses, viral proteins present in the VZV virion tegument have regulatory functions. The two VZV-encoded serine-threonine kinases encoded by open reading frame 47 (ORF47), which is conserved among the herpesviruses, and ORF66, which is found only in the alphaherpesviruses, are tegument/regulatory proteins (16, 17). ORF47 kinase activity is required for infection of T cell xenografts and for virion assembly and release from T cells (18). While dispensable, the ORF66 protein, specifically, its kinase activity, was required for robust VZV virion formation in T cells and to protect infected T cells from apoptosis and inhibit innate IFN-mediated cell defenses (6, 7). In contrast to their critical functions in skin pathogenesis, ORF10 and ORF11 tegument proteins were dispensable for VZV T cell tropism (19). In addition, functions of the immediate-early regulatory protein IE63 that depend upon its usual phosphorylation were not required in T cell xenografts (20). Comparative analyses of these protein functions underscore differential requirements and the need for complete virion assembly and release from T cells, whereas spread by cell-cell fusion can occur in skin despite impaired replication.

T cell tropism of live attenuated VZV vaccine.

VZV vaccines used for the prevention of varicella and zoster are derived from the parent Oka (pOka) virus, which was attenuated by passage in human and guinea pig embryo fibroblasts to generate vaccine Oka (vOka) (21). Clinically healthy individuals given vOka vaccines seldom have skin lesions, but these vaccines can cause disseminated infection with a varicella-like skin rash in immunocompromised individuals, suggesting that the method of pOka attenuation impaired vOka replication in skin but not in T cells. Inoculation of T cell xenografts with pOka and vOka showed that vOka retains wild-type infectivity for T cells, as predicted by clinical experience. Thus, viral functions required for T cell tropism are not affected by serial passage of VZV in fibroblasts, despite the marked effects on skin infection.

Summary.

Given its critical role in VZV pathogenesis, strategies used to disrupt VZV T cell tropism may mitigate the serious consequences of VZV infection in healthy and high-risk patients. A second-generation live attenuated VZV vaccine with mutations that selectively impair T cell infection would diminish the risk of dissemination in immunocompromised patients and, since T cells also transport VZV to sensory ganglia (22), reduce vaccine latency in healthy individuals. Further, high-throughput multiparametric techniques like single-cell mass cytometry can be applied successfully in the future to screen drug candidates for antiviral activity against the multifactorial changes that occur during the takeover of T cells by VZV.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the many postdoctoral fellows, graduate students, and research staff who have contributed to our studies of VZV pathogenesis and Garry Nolan, Gourab Mukherjee, Sean Bendall, and Adrish Sen for collaboration on our CyTOF study of VZV T cell infection.

REFERENCES

- 1.Koropchak CM, Solem SM, Diaz PS, Arvin AM. 1989. Investigation of varicella-zoster virus infection of lymphocytes by in situ hybridization. J Virol 63:2392–2395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abendroth A, Morrow G, Cunningham AL, Slobedman B. 2001. Varicella-zoster virus infection of human dendritic cells and transmission to T cells: implications for virus dissemination in the host. J Virol 75:6183–6192. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6183-6192.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quinlivan MA, Gershon AA, Nichols RA, La Russa P, Steinberg SP, Breuer J. 2006. Vaccine Oka varicella-zoster virus genotypes are monomorphic in single vesicles and polymorphic in respiratory tract secretions. J Infect Dis 193:927–930. doi: 10.1086/500835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ku CC, Padilla JA, Grose C, Butcher EC, Arvin AM. 2002. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human tonsillar CD4+ T lymphocytes that express activation, memory, and skin homing markers. J Virol 76:11425–11433. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.22.11425-11433.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moffat JF, Stein MD, Kaneshima H, Arvin AM. 1995. Tropism of varicella-zoster virus for human CD4+ and CD8+ T lymphocytes and epidermal cells in SCID-hu mice. J Virol 69:5236–5242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schaap A, Fortin JF, Sommer M, Zerboni L, Stamatis S, Ku CC, Nolan GP, Arvin AM. 2005. T-cell tropism and the role of ORF66 protein in pathogenesis of varicella-zoster virus infection. J Virol 79:12921–12933. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.20.12921-12933.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schaap-Nutt A, Sommer M, Che X, Zerboni L, Arvin AM. 2006. ORF66 protein kinase function is required for T-cell tropism of varicella-zoster virus in vivo. J Virol 80:11806–11816. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00466-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ku CC, Zerboni L, Ito H, Graham BS, Wallace M, Arvin AM. 2004. Varicella-zoster virus transfer to skin by T cells and modulation of viral replication by epidermal cell interferon-alpha. J Exp Med 200:917–925. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bendall SC, Nolan GP, Roederer M, Chattopadhyay PK. 2012. A deep profiler's guide to cytometry. Trends Immunol 33:323–332. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.02.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bendall SC, Simonds EF, Qiu P, ADAmir el, Krutzik PO, Finck R, Bruggner RV, Melamed R, Trejo A, Ornatsky OI, Balderas RS, Plevritis SK, Sachs K, Pe'er D, Tanner SD, Nolan GP. 2011. Single-cell mass cytometry of differential immune and drug responses across a human hematopoietic continuum. Science 332:687–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1198704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sen N, Mukherjee G, Arvin AM. 2015. Single cell mass cytometry reveals remodeling of human T cell phenotypes by varicella zoster virus. Methods 90:85–94. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2015.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sen N, Mukherjee G, Sen A, Bendall SC, Sung P, Nolan GP, Arvin AM. 2014. Single-cell mass cytometry analysis of human tonsil T cell remodeling by varicella zoster virus. Cell Rep 8:633–645. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willemze R, Jaffe ES, Burg G, Cerroni L, Berti E, Swerdlow SH, Ralfkiaer E, Chimenti S, Diaz-Perez JL, Duncan LM, Grange F, Harris NL, Kempf W, Kerl H, Kurrer M, Knobler R, Pimpinelli N, Sander C, Santucci M, Sterry W, Vermeer MH, Wechsler J, Whittaker S, Meijer CJ. 2005. WHO-EORTC classification for cutaneous lymphomas. Blood 105:3768–3785. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-09-3502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moffat J, Mo C, Cheng JJ, Sommer M, Zerboni L, Stamatis S, Arvin AM. 2004. Functions of the C-terminal domain of varicella-zoster virus glycoprotein E in viral replication in vitro and skin and T-cell tropism in vivo. J Virol 78:12406–12415. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.22.12406-12415.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moffat J, Ito H, Sommer M, Taylor S, Arvin AM. 2002. Glycoprotein I of varicella-zoster virus is required for viral replication in skin and T cells. J Virol 76:8468–8471. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.16.8468-8471.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Erazo A, Kinchington PR. 2010. Varicella-zoster virus open reading frame 66 protein kinase and its relationship to alphaherpesvirus US3 kinases. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 342:79–98. doi: 10.1007/82_2009_7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ng TI, Grose C. 1992. Serine protein kinase associated with varicella-zoster virus ORF 47. Virology 191:9–18. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(92)90161-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moffat JF, Zerboni L, Sommer MH, Heineman TC, Cohen JI, Kaneshima H, Arvin AM. 1998. The ORF47 and ORF66 putative protein kinases of varicella-zoster virus determine tropism for human T cells and skin in the SCID-hu mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 95:11969–11974. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.20.11969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Che X, Reichelt M, Sommer MH, Rajamani J, Zerboni L, Arvin AM. 2008. Functions of the ORF9-to-ORF12 gene cluster in varicella-zoster virus replication and in the pathogenesis of skin infection. J Virol 82:5825–5834. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00303-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baiker A, Bagowski C, Ito H, Sommer M, Zerboni L, Fabel K, Hay J, Ruyechan W, Arvin AM. 2004. The immediate-early 63 protein of varicella-zoster virus: analysis of functional domains required for replication in vitro and for T-cell and skin tropism in the SCIDhu model in vivo. J Virol 78:1181–1194. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.3.1181-1194.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gershon AA. 2001. Live-attenuated varicella vaccine. Infect Dis Clin North Am 15:65–81. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5520(05)70268-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zerboni L, Sen N, Oliver SL, Arvin AM. 2014. Molecular mechanisms of varicella zoster virus pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 12:197–210. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]