ABSTRACT

Broadly neutralizing antibodies isolated from infected patients who are elite neutralizers have identified targets on HIV-1 envelope (Env) glycoprotein that are vulnerable to antibody neutralization; however, it is not known whether infection established by the majority of the circulating clade C strains in Indian patients elicit neutralizing antibody responses against any of the known targets. In the present study, we examined the specificity of a broad and potent cross-neutralizing plasma obtained from an Indian elite neutralizer infected with HIV-1 clade C. This plasma neutralized 53/57 (93%) HIV pseudoviruses prepared with Env from distinct HIV clades of different geographical origins. Mapping studies using gp120 core protein, single-residue knockout mutants, and chimeric viruses revealed that G37080 broadly cross-neutralizing (BCN) plasma lacks specificities to the CD4 binding site, gp41 membrane-proximal external region, N160 and N332 glycans, and R166 and K169 in the V1-V3 region and are known predominant targets for BCN antibodies. Depletion of G37080 plasma with soluble trimeric BG505-SOSIP.664 Env (but with neither monomeric gp120 nor clade C membrane-proximal external region peptides) resulted in significant reduction of virus neutralization, suggesting that G37080 BCN antibodies mainly target epitopes on cleaved trimeric Env. Further examination of autologous circulating Envs revealed the association of mutation of residues in the V1 loop that contributed to neutralization resistance. In summary, we report the identification of plasma antibodies from a clade C-infected elite neutralizer that mediate neutralization breadth via epitopes on trimeric gp120 not yet reported and confer autologous neutralization escape via mutation of residues in the V1 loop.

IMPORTANCE A preventive vaccine to protect against HIV-1 is urgently needed. HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins are targets of neutralizing antibodies and represent a key component for immunogen design. The mapping of epitopes on viral envelopes vulnerable to immune evasion will aid in defining targets of vaccine immunogens. We identified novel conformational epitopes on the viral envelope targeted by broadly cross-neutralizing antibodies elicited in natural infection in an elite neutralizer infected with HIV-1 clade C. Our data extend our knowledge on neutralizing epitopes associated with virus escape and potentially contribute to immunogen design and antibody-based prophylactic therapy.

INTRODUCTION

Broadly neutralizing antibodies (BNAbs) target trimeric envelope glycoprotein (Env) spikes of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). Characterization of the BNAbs has provided key clues toward the design and development of both prophylactic and therapeutic vaccines (1–6). A small proportion of individuals chronically infected with HIV-1 develop BNAbs (7–14), and the isolation of several broad and potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) from such individuals with distinct molecular specificities to viral envelope protein has been reported (15–23). The cross-neutralizing serum antibodies obtained from such individuals (also referred to as elite neutralizers), which have considerable breadth, target epitopes on structurally conserved regions of Env such as the CD4 binding site (CD4bs) (22, 24–26), V1V2, including glycan moieties (19, 20, 27, 28), the gp120-gp41 interface (18, 29), and the membrane-proximal external regions (MPER) (16, 30–32). Several studies have indicated that the variable regions within HIV-1 gp120 contain epitopes targeted by autologous antibodies as well as BNAbs (33–40). Recently the V1V2 region has been linked to the development of broadly cross-neutralizing (BCN) antibodies (35, 41), and the residues between 160 and 172 (notably R166S/K or K169A) in V1V2 have been demonstrated to be associated with virus escape from autologous antibody response (35). Recent studies have further indicated that BCNAb development in vivo is associated with antibody affinity maturation and coevolution of virus, resulting in a considerable degree of somatic hypermutations (19, 20, 23, 26, 35, 42–50). Such information is crucial for the design and development of suitable Env-based immunogens capable of eliciting broad and potent cross-neutralizing antibodies through vaccination.

While a number of studies on the molecular specificities of broadly neutralizing antibodies obtained from African clade C-infected individuals have been reported (9, 37, 51–62), knowledge on immune evasion in Indian clade C-infected elite neutralizers is very limited (63).

In the present study, we examined plasma samples obtained from two hundred asymptomatic and antiretroviral therapy (ART) naive Indian HIV-infected donors and identified plasma with cross-neutralizing antibodies. The molecular specificities of plasma antibodies obtained from an HIV-1 clade C-infected elite neutralizer was characterized in detail that displayed exceptional neutralization breadth across clades of different geographical origins. Interestingly, we found that neutralization breadth was associated with the presence of unique epitopes on the trimeric gp120.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics statement.

The blood samples were collected under the IAVI Protocol G study from slow-progressing ART naive HIV-1-positive donors from Nellore District of the state of Andhra Pradesh, southern India, by trained clinicians at the YRG Care Hospital following approval and clearance from the Institutional Review Board (IRB) and the Ethics Committee. The serum and plasma samples collected were shipped to the HIV Vaccine Translational Research Laboratory, Translational Health Science and Technology Institute, for further assessment and research on the neutralizing antibody response.

Plasmids, viruses, antibodies, proteins, and cells.

Plasmids encoding HIV-1 envelopes representing distinct clades are shown in Table 1. Monoclonal antibodies used in the study and TZM-bl cells were procured from the NIH AIDS Research and Reagents Reference program and from the IAVI Neutralizing Antibody Consortium (NAC). 293T cells were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). Plasmid DNA encoding BG505-SOSIP.664-D7324, its purified cleaved trimeric protein (64), and pcDNA5-FRT BG505 furin A (65) were kindly provided by John Moore, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. Purified gp120 TripleMut core protein (66) was obtained from Richard Wyatt, The Scripps Research Institute, through the NAC. HIV-2 7312A and its chimeric constructs were provided by Lynn Morris, NICD, Johannesburg, South Africa.

TABLE 1.

Neutralization breadth of Protocol G G37080 plasma samples collected at two different time points tested against panel of 57 Env-pseudotyped viruses

Purification of monomeric and trimeric Env proteins.

Codon-optimized gp120 plasmid encoding clade C 4-2.J41 (67, 68) gp120 was cloned in pcDNA 3.1/V5-His-TOPO vector and transfected into 293T cells using polyethyleneimine (PEI). Supernatants containing soluble gp120 were filtered through 0.45-μm-pore-size filters and subsequently purified using nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid (Ni-NTA) agarose matrix (Qiagen Inc.) by elution with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 300 mM imidazole (pH 8.0). The purified monomeric gp120 protein was extensively dialyzed with PBS (pH 7.4), concentrated using Amicon ultracentrifugal filters (Millipore Inc.) with a 30-kDa cutoff, and stored at −80°C until further use.

The trimeric BG505-SOSIP.664 protein was purified using 293F cells essentially as described by Sanders et al. (69). Briefly, the 293F cells were transfected with plasmid DNA encoding both BG505-SOSIP.664 gp140 envelope and furin (65). Supernatant containing soluble BG505-SOSIP.664 gp140 was harvested 72 to 96 h posttransfection, filtered, and passed through a lectin agarose column obtained from Galanthus nivalis (Sigma Inc.). The nonspecifically bound proteins then were washed in PBS (pH 7.4) supplemented with 0.5 M NaCl. The bound proteins then were eluted using 0.5 M methyl α-d-mannopyranoside, extensively dialyzed with 1× PBS, and concentrated. BG505-SOSIP.664 was further purified by Sephadex G-200 size exclusion chromatography (AKTA; GE). Trimeric protein fractions were collected and pooled, their quality was assessed by running in blue native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (BN-PAGE), and they were favorably assessed for their ability to bind to only neutralizing and not to nonneutralizing and MPER-directed monoclonal antibodies as described elsewhere (64) by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Depletion of plasma antibodies by monomeric gp120 and trimeric gp140 Env proteins.

Purified soluble monomeric 4-2.J41 gp120 and trimeric BG505 SOSIP.664 proteins, in addition to the MPER peptide (C1C; encoding clade C sequence) (70), were used for the depletion of plasma antibodies where purified proteins were covalently coupled to tosylactivated MyOne Dynabeads (Life Technologies Inc.) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Briefly, 30 mg of beads was coupled with 1 mg of both monomeric and trimeric Env proteins in coupling buffer [0.1 M NaBO4, 1 M (NH4)2SO4; pH 9.4] overnight at 37°C for 16 to 24 h. Proteins bound to magnetic beads were separated from unbound proteins using a DynaMag 15 magnet (Life Technologies, Inc.). Beads bound to Env proteins next were incubated with blocking buffer (PBS [pH 7.4], 0.1% bovine serum albumin [BSA; Sigma], and 0.05% Tween 20) at 37°C to block the unbound sites. The antigenic integrity of both 4-2.J41 monomeric gp120 and BG505-SOSIP.664 bound to the beads was assessed for their ability to bind VRC01 and 4E10 MAbs (for monomeric gp120) and PGT121, F105, and 4E10 MAbs (for BG505-SOSIP.664) by flow cytometry (FACSCanto; Becton and Dickinson, Inc.).

For depletion studies, G37080 plasma was diluted to 1:50 in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) containing 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 500 μl of diluted plasma was incubated with 20 μl of beads at room temperature for 45 min. Unbound plasma antibodies were separated from those that were bound to protein-coated beads using a DynaMag 15 magnet as described above. This step was repeated 4 to 5 times for the depletion of plasma antibodies by monomeric gp120 and 10 to 12 times in the case of BG505-SOSIP.664-coated beads. As a negative control, G37080 plasma antibodies were depleted with uncoated beads in parallel. In addition to ELISA, the percent depletion of G37080 plasma antibodies was assessed by examining the sequential decrease in binding of protein-coated beads with depleted plasma antibodies by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). PGT121 MAb was taken as a positive control for checking depletion by BG505-SOSIP.664 trimeric Env.

gp120 and gp140 ELISA.

For gp120 ELISA, a high-binding polystyrene microtiter plate (Nunc, Inc.) was coated with 100 μl of monomeric 4-2.J41 gp120 (1 μg/ml) in binding buffer containing 0.1 M NaHCO3 (pH 8.6) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The gp120-plate was washed once with 1× PBS (pH 7.4) and blocked with 5% nonfat milk for 90 min at 37°C. The plate then was washed three times with 1× PBS followed by the addition of 100 μl of MAbs, as well as the depleted and undepleted plasma antibodies at different dilutions, and incubated for 1 h at room temperature. The wells of the ELISA plate were washed four times with PBS containing 0.1% Tween 20 (PBST), followed by the addition of 100 μl of 1:3,000-diluted horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated anti-human IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch, Inc.), and further incubated for 45 min at room temperature. Unbound conjugates were removed by washing with PBST, and color was developed by the addition of 100 μl of 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine (TMB) (Life Technologies, Inc.) substrate. Absorbance was measured at 450 nm in a spectrophotometer.

Binding of antibodies to BG505-SOSIP.664-D7324 trimeric protein was assessed essentially as described by Sanders et al. (69) in a sandwich ELISA. Briefly, a high-binding microtiter plate (Nunc, Inc.) first was coated with D7324 antibody at 10 μg/ml (Aalto Bio Reagents, Dublin, Ireland) followed by blocking extra unbound sites with 5% nonfat milk for 90 min at 37°C. One hundred microliters of BG505.664-D7324 trimeric protein (300 ng/ml) then was added and incubated for 45 min at room temperature. The extent of binding of G37080 plasma antibodies compared to that of known neutralizing monoclonal antibodies was assessed by the addition of primary and HRP-conjugated secondary anti-human antibody as described above.

Neutralization assay.

Neutralization assays were carried out using TZM-bl cells as described before (68). Briefly, Env-pseudotyped viruses were incubated with various dilutions of depleted plasma antibodies and incubated for an hour at 37°C in a CO2 incubator under humidified conditions, and subsequently 1 × 104 TZM-bl cells were added to the mixture in the presence of 25 μg/ml DEAE-dextran (Sigma, Inc.). The plates were further incubated for 48 h, and the degree of virus neutralization was assessed by measuring relative luminescence units (RLU) in a luminometer (Victor X2; PerkinElmer Inc.).

Amplification, cloning, and mutagenesis of autologous HIV-1 env genes.

Autologous complete env genes were obtained from G37080 plasma as described previously, with slight modifications (68). Briefly, viral RNA was extracted using a high-pure viral RNA kit (Roche Inc.) by following manufacturer's protocol, and cDNA was prepared by reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) using a Superscript III first-strand synthesis kit (Invitrogen Inc.). rev-gp160 env genes were amplified using a Phusion high-fidelity DNA polymerase (New England BioLabs Inc.). The gp160 amplicons were purified and ligated into pcDNA 3.1/V5-His-TOPO (Invitrogen Inc.) vector. Chimeric Env proteins were prepared by overlapping PCR, and point substitutions were made with a QuikChange II kit (Agilent Technologies Inc.) by following the manufacturer's protocol and as described previously (71).

Preparation of envelope-pseudotyped viruses.

Pseudotyped viruses were prepared by the cotransfection of envelope-expressing plasmid with an env-deleted HIV-1 backbone plasmid (pSG3ΔEnv) into 293T cells in 6-well tissue culture plates using a FuGENE6 transfection kit (Promega Inc.). Cell supernatants containing pseudotyped viruses were harvested 48 h posttransfection and then stored at −80°C until further use. The infectivity assays were done in TZM-bl cells (1 × 105cells/ml) containing DEAE-dextran (25 μg/ml) in 96-well microtiter plates, and the infectivity titers were determined by measuring the luciferase activity using Britelite luciferase substrate (PerkinElmer Inc.) with a Victor X2 luminometer (PerkinElmer Inc.).

RESULTS

Identification of an elite neutralizer with HIV-1 clade C infection whose plasma showed exceptional neutralization breadth.

The present study, under IAVI Protocol G, was designed (i) to screen and identify plasma antibodies obtained from Indian donors chronically infected with HIV-1 clade C, with substantial breadth toward neutralizing cross-clade HIV-1 primary variants, and (ii) to elucidate the molecular specificities associated with neutralization breadth. Our hypothesis was that given the genetic distinctness of clade C viruses of Indian and non-Indian origin, as well the likely differences in host genetics between populations and their ancestral origins associated with the modulation of humoral immune responses, the specificities of antibodies developed in vivo associated with neutralization breadth and potency would be different.

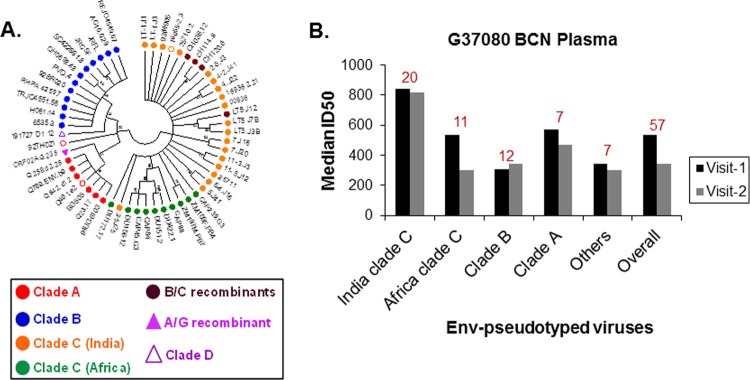

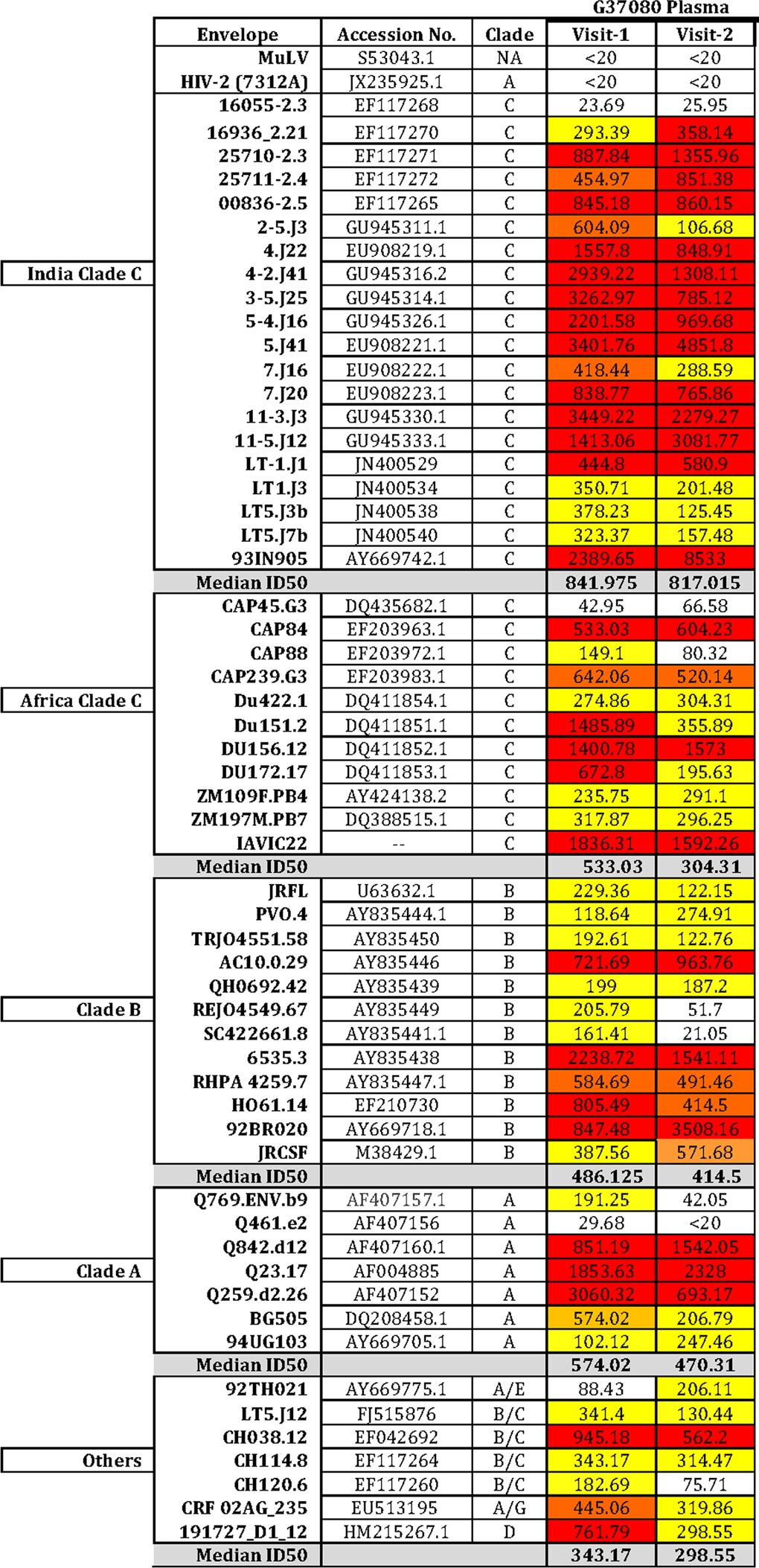

Through screening of two hundred plasma samples obtained from chronically infected ART naive Indian patients against a panel of 57 pseudoviruses containing Envs of distinct clades and geographical origins (Fig. 1A), we identified one donor (G37080) whose plasma showed exceptional neutralization breadth. Donor G37080 serum neutralized >90% of the 57 different pseudoviruses tested, with a median 50% inhibitory dose (ID50) value of 533.03 (Table 1 and Fig. 1B).

FIG 1.

(A) Genetic divergence of amino acid sequences of 57 HIV-1 Env (gp160) pseudoviruses used to assess neutralization breadth and potency of G37080 BCN plasma. The maximum likelihood bootstrapped consensus phylogenetic tree was constructed using the Jones-Taylor-Thornton (JTT) substitution model with 50 bootstrapped replicates in Mega 5.2. Bootstrapped values are shown at the nodes of each branch. Hollow circles represent envelopes (16055-2.3 and 92TH021) resistant to neutralization by G37080 BCN plasma. (B) Neutralization breadth of the G37080 BCN plasma obtained at visit 1 and visit 2 were assessed against pseudotyped viruses expressing HIV-1 Env representing different clades and origins. Neutralization titers (median ID50 values) were obtained by titrating Env-pseudotyped viruses against G37080 plasma samples. Values at the top of each bar graph indicate the number of viruses belonging to each clade/origin tested.

Follow-up plasma sample from this donor (G37080) subsequently was obtained after 8 months to assess whether the neutralization breadth and potencies, along with their molecular specificities, were retained and/or improved, as we expected that during the course of disease, the breadth and potency of neutralizing antibodies broadens through somatic hypermutations (72) and/or clonal selection processes. As shown in Fig. 1B and Table 1, follow-up plasma antibodies of donor G37080 (referred to as the visit 2 samples) were found to exhibit neutralization breadth comparable to that of visit 1 plasma. Overall, G37080 BCN plasma was found to potently neutralize pseudoviruses containing Indian clade C Env with a neutralization score of 2.5 (13). Furthermore, the neutralization sensitivity of Env-pseudotyped viruses was found to be correlated with the serum IgG (data not shown), suggesting that the broad neutralization was associated with IgG-specific responses. Taken together, our data indicate that a strong humoral immune response to HIV-1 was mounted in donor G37080 and was maintained over time.

Evidence that G37080 BCN plasma antibodies do not target epitopes in CD4bs, MPER, and known glycan and nonglycan residues in variable domains of Env.

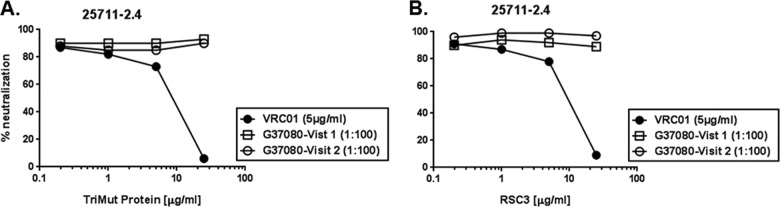

We first examined whether the G37080 BCN plasma contains antibodies directed to the CD4bs on Env. Plasma samples obtained from both visits were pretreated with 25 μg/ml of TripleMut core protein (66), which was a concentration that we found to inhibit the neutralization of 25711-2.4 pseudovirus by VRC01 MAb by >95%. Pretreated plasma subsequently was used to neutralize pseudovirus 25711-2.4 Env, and as shown in Fig. 2, no perturbation of G37080 neutralizing activity was observed against pseudovirus 25711-2.4. A similar observation was made when these plasma antibodies were pretreated with RSC3 core protein (22). In addition, the G37080 BCN plasma antibodies were found to efficiently neutralize IgG1b12- and VRC01-resistant viruses (data not shown). Our data indicated that the G37080 BCN plasma antibodies do not contain CD4bs-directed neutralizing antibodies.

FIG 2.

Assessing dependence of G37080 BCN antibodies to CD4 binding site (CD4bs) region of HIV-1 Env. G37080 BCN plasma samples and VRC01 MAb (concentrations that neutralized 25711-2.4 by >80%) preincubated with different concentrations, as indicated, with TripleMut core (A) and RSC3 (B) proteins were examined for their ability to neutralize 25711-2.4 Env pseudotyped virus in a TZM-bl cell neutralization assay. Note that while VRC01 preabsorbed with both TripleMut and RSC3 proteins showed inhibited neutralization of 25711-2.4 in a dose-dependent manner, no such effect was observed with G37080 BCN plasma, indicating the absence of CD4bs-directed neutralizing antibodies.

To elucidate whether the BCN plasma antibodies are directed to MPER in gp41, we used HIV-2/HIV-1 chimeric viruses (73) that expressed minimal residues of HIV-1 MPER containing epitopes required for MPER-directed MAbs, such as 2F5, 4E10, Z13e, and 10E8. As shown in Table 2, the G37080 BCN plasma from both visits was found to show modest neutralization of HIV-2 expressing HIV-1 clade C MPER (7312-C1C), with ID50 values of 306.42 and 371.02, respectively. We also found that the depletion of G37080 plasma with a clade C MPER peptide (C1C) completely abolished the sensitivity of 7312A-C1C virus to G37080 plasma (Table 3). Our data suggest that although the G37080 BCN plasma neutralized 7312-C1C, the presence of MPER-directed antibodies was not associated with neutralization breadth.

TABLE 2.

Examination of specificity of G37080 plasma antibodies obtained at both visits to HIV Env

| HIV type | Region | Fold decrease in ID50a for plasma at visit: |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | ||

| HIV-1 Env mutants | |||

| HIV-1 25711-2.4 N160A | V2 | 1.02 | <1 |

| HIV-1 25711-2.4 R166A | <1 | <1 | |

| HIV-1 25711-2.4 K169E | <1 | <1 | |

| HIV-1 93IN905 R166A | <1 | <1 | |

| HIV-1 93IN905 K169A | <1 | <1 | |

| HIV-1 25711-2.4 N332A | V3 | 1.52 | <1 |

| HIV-1 CAP239.G3 N332A | 1.35 | 1.32 | |

| HIV-2/HIV-1 chimera | Region of HIV-1 | ID50 | ID50 |

| HIV-2 7312A | HIV-2 wild type | <20 | <20 |

| HIV-2 7312A-C1C | Clade C MPER | 306.42 | 371.02 |

| HIV-2 7312A-C3 | 2F5 epitope | <20 | <20 |

| HIV-2 7312A-C4 | 4E10, Z13e1, and 10E8 epitopes | 334.34 | 371.27 |

| HIV-2 7312A-C6 | 4E10 minimal epitope | <20 | 223.90 |

| HIV-2 7312A-C7 | 2F5 minimal epitope | <20 | <20 |

ID50 values refer to the reciprocal dilution that conferred 50% neutralization of viruses in a TZM-bl assay. Assays were done in duplicate and were repeated more than three times.

TABLE 3.

Degree of shift in sensitivity of Env-pseudotyped viruses to G37080 BCN plasma depleted with monomeric and trimeric Envs and C1C peptide

| Env-pseudotyped virus | Fold reduction in neutralization (ID50)a |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| gp140 trimer (BG505-SOSIP.664) | gp120 monomer (4-2.J41) | MPER (C1C peptide) | |

| 25710-2.3 | >10.30 | 1.3 | 0.83 |

| 25711-2.4 | >8.52 | 1.4 | 1.44 |

| 3-5.J25 | >7.85 | 0.9 | 0.84 |

| 4-2.J41 | 12.11 | 1.1 | 1.04 |

| IAVI_C22 | >15.92 | 1.2 | 1.18 |

| 92BR020 | >35.08 | 1.1 | 1.34 |

| 93IN905 | 3.41 | 1.2 | 0.94 |

| JRCSF | >8.75 | 0.5 | 0.93 |

| Q23.17 | >23.28 | 1.0 | 0.98 |

| Du156.12 | >15.73 | 0.8 | 1.61 |

| HVTR-PG80v1.eJ7 | >10.03 | 0.9 | 1.12 |

| HVTR-PG80v1.eJ19 | >15.60 | 0.5 | 1.18 |

| HIV-2 7312A-C1C | >10 | ||

Fold reduction in virus neutralization was obtained by comparing the neutralization titer (ID50 values) of panel viruses against undepleted and depleted G37080 plasma. ID50 values are reciprocal dilutions at which the undepleted and depleted plasma conferred 50% neutralization of the Env-pseudotyped viruses in TZM-bl cells.

We next investigated whether the plasma antibodies of the donor G37080 target residues in variable loops, particularly in V1V2 and V3 regions, which have been shown in several studies to be epitopes targeted by BCN antibodies on HIV-1 Env. We first tested the extent of neutralization by G37080 BCN plasma antibodies of Env-pseudotyped viruses lacking glycans at positions 160 (N160) and 332 (N332) in the V2 region and V3 base, respectively, and also R166 and K169 in the V2 region, which are major targets of recently identified broad and potent neutralizing monoclonal antibodies. In order to test this, two clade C Envs (25711-2.4 and CAP239.G3), containing N160A and N332A substitutions, were tested (Table 2). Our data indicate that the pseudoviruses containing Env expressing the N160 or N332 substitution have sensitivities identical to those of G37080 plasma antibodies. Similar observations were found with R166A and K169A in the 93IN905 Env backbone. Taken together, our observations indicate that G37080 BCN plasma antibodies did not utilize these residues in V2 and V3 regions for neutralization breadth; these have been identified as important epitopes recognized by broadly neutralizing antibodies elicited in clade C infection as described before (35, 41, 56).

Association of neutralization breadth of G37080 plasma with recognition of conformational epitopes on cleaved trimeric Env but not with that in monomeric gp120 or MPER.

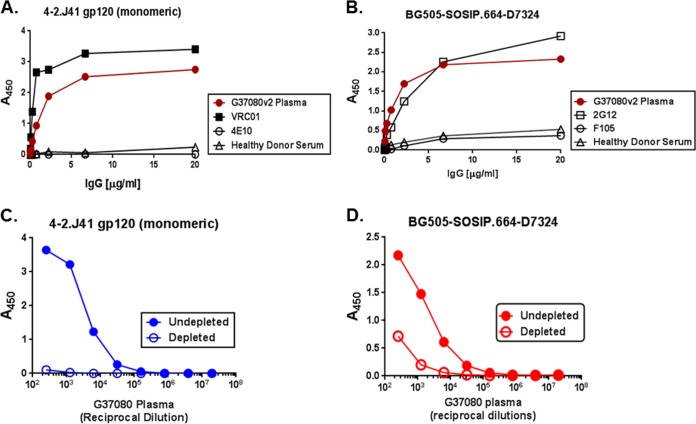

In order to examine whether broad neutralization conferred by the G37080 plasma antibodies was through the recognition of epitopes on monomeric gp120 or cleaved near-native Env trimers, we tested the binding of G37080 serum IgG to monomeric 4-2.J41 gp120 and soluble gp140 (BG505-SOSIP.664) by ELISA. We found that in addition to the monomeric 4-2.J41 gp120 (Fig. 3A), G37080 serum polyclonal IgG was found to efficiently bind to the BG505 SOSIP.664-D7324 soluble trimeric Env (Fig. 3B), indicating that the G37080 plasma primarily contains neutralizing antibodies that target epitopes on cleaved Env trimers.

FIG 3.

Binding of G37080 BCN plasma IgG to 4-2.J41 monomeric gp120 (A) and BG505-SOSIP.664-D7324 cleaved trimeric gp140 (B) soluble proteins was assessed by ELISA. IgG purified from HIV-negative healthy donor and known MAbs were used as controls. The extent of binding of the depleted and undepleted G37080 BCN plasma with magnetic beads coated with 4-2.J41 monomeric gp120 (C) and BG505-SOSIP.664 cleaved trimeric gp140 to their respective proteins by ELISA. Note that binding to trimeric protein by ELISA was assessed by using BG505-SOSIP.664 tagged with the D7324 epitope to maintain the native conformation of trimeric Env as described before (69).

We next examined whether binding of the G37080 plasma antibodies to epitopes on cleaved BG505-SOSIP.664 trimeric envelope was associated with neutralization breadth. For this, we tested the ability of G37080 plasma antibodies depleted of both monomeric and trimeric Envs, as well as of MPER peptides, to neutralize a set of Env-pseudotyped viruses, which were found to be sensitive to this particular plasma sample. Purified 4-2.J41 monomeric gp120, BG505-SOSIP.664 trimeric gp140, and C1C MPER peptide bound to the magnetic beads were used to deplete G37080 plasma antibodies as described in Materials and Methods. The depleted BCN G37080 antibodies first were assessed for their binding to 4-2.J41 gp120 monomers, BG505-SOSIP.664-D7324, and C1C peptide and compared to undepleted plasma antibodies by ELISA. As shown in Fig. 3C and D, G37080 plasma depleted with monomeric gp120 and trimeric gp140, respectively, had significantly reduced binding activity against the respective soluble proteins. Similar observation was made with MPER peptide (data not shown). The depleted plasma antibodies subsequently were assessed for neutralization activity using a panel of 12 Env-pseudotyped viruses that were susceptible to untreated G37080 plasma antibodies as mentioned above. As shown in Table 3, depletion with 4-2.J41gp120 monomer and C1C peptide did not show any change in neutralization breadth of G37080 plasma antibodies, while depletion with BG505-SOSIP.664 showed a significant reduction in virus neutralization. Similar observations were made with the BG505-SOSIP.664-depleted PGT121 and C1C peptide-depleted 4E10 MAbs, which lost the ability to efficiently neutralize Env-pseudotyped viruses (16055 and ZM233.6) and HIV-2/HIV-1 (7312A-C1C) chimeric virus compared to their undepleted counterparts (data not shown), validating our data. Interestingly, C1C peptide-depleted G37080 plasma failed to neutralize HIV-2/HIV-1 (7312A-C1C) chimeric virus, indicating that the presence of residual traces of MPER-directed antibodies (as shown in Table 2) is not responsible for neutralization breadth. Furthermore, the examination of sensitive (25711-2.4) and resistant (16055-2.3 and CAP45.G3) chimeric Envs indicated that the BCN G37080 plasma antibodies predominantly target epitopes in the V1V2 region (Table 4) in gp120. Our data clearly indicate a correlation between neutralization breadth and binding of the G37080 BCN plasma antibodies to the conformational epitopes on cleaved trimeric gp120, likely in the V1V2 region; however, we do not rule out the possibility that this BCN plasma targets other discontinuous epitopes in gp120 but not in MPER.

TABLE 4.

Dissection of specificity for autologous neutralization resistance

| Chimera and point mutant | Neutralization potency (ID50) |

|

|---|---|---|

| Fold changea | Effectb | |

| PG80v1.eJ7 Env backbone | ||

| V1V2 loop | ||

| PG80v2.eJ38 (V1V2) in v1.eJ7 | 45.75 | Decrease |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (V1) in v1.eJ7 | 27.97 | Decrease |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (V2) in v1.eJ7 | 1.35 | No effect |

| Point mutations | ||

| PG80v1.eJ7 (D133N) | 3.25 | Decrease |

| PG80v1.eJ7 (S143G) | 0.87 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ7 (D133N + S143G) | 2.88 | Decrease |

| PG80v1.eJ7 (T147P) | 8.21 | Decrease |

| PG80v1.eJ19 Env backbone | ||

| V1V2 loop | ||

| PG80v2.eJ38(V1V2) in v1.eJ19 | 23.05 | Decrease |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (V1) in v1.eJ19 | 28.61 | Decrease |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (V2) in v1.eJ19 | 1.87 | Increase |

| Point mutations | ||

| PG80v1.eJ19 (D133N) | 2.51 | Decrease |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (T139A) | 0.99 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (T139A + T140D) | 2.64 | Increase |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (N143G) | 1.38 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (T139A + T140D + N143G) | 2.16 | Increase |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (T145P) | 3.24 | Decrease |

| PG80v2.eJ38 Env backbone | ||

| V1V2 loop | ||

| PG80v1.eJ7 (V1V2) in v2.eJ38 | 26.56 | Increase |

| PG80v1.eJ7 (V1) in v2.eJ38 | 49.62 | Increase |

| PG80v1.eJ7 (V2) in v2.eJ38 | 1.07 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ19(V1V2) in v2.eJ38 | 12.81 | Increase |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (V1) in v2.eJ38 | 37.60 | Increase |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (V2) in v2.eJ38 | 0.94 | No effect |

| Other regions in gp120 | ||

| PG80v1.eJ7 (V3C3) in v2.eJ38 | 0.84 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ7 (V3C3V4C4) in v2.eJ38 | 0.90 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ7 (C4V5C5) in v2.eJ38 | 1.08 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (V3C3) in PG80v2.eJ38 | 1.09 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (V3C3V4C4) in PG80v2.eJ38 | 1.15 | No effect |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (C4V5C5) in PG80v2.eJ38 | 0.96 | No effect |

| Point mutations | ||

| PG80v1.eJ19 V1 (T139A+T140D) in v2.eJ38 | 53.91 | Increase |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (N133D) | 4.72 | Increase |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (G143S) | 0.94 | No effect |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (N133D+G143S) | 3.63 | Increase |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (P147T) | 4.11 | Increase |

| Heterologous Env chimera | ||

| V1V2 loop | ||

| 16055-2.3 (25711-2.4 V1V2) | 18.38 | Increase |

| 25711-2.4 (16055-2.3 V1V2) | 2.03 | Decrease |

| CAP45 (25711-2.4 V1V2) | 16.84 | Increase |

| 25711-2.4 (CAP45-V1V2) | 10.54 | Decrease |

Fold changes in reciprocal dilution of plasma mediating 50% virus neutralization (ID50).

Fold increase or decrease in neutralization titer (ID50 values).

Mutations in V1 region confer resistance to autologous viruses to the G37080 plasma antibodies.

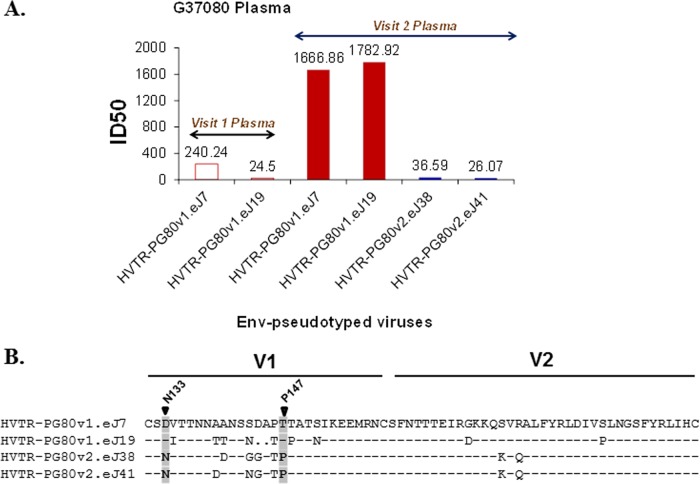

In order to decipher the specificity of the G37080 plasma antibodies, we examined the degree of susceptibility of pseudoviruses prepared using env genes amplified from contemporaneous autologous G37080 plasma obtained at the baseline and follow-up visits. As shown in Fig. 4A, both of the Env proteins obtained from visit 2 plasma (HVTR-PG80v2.eJ38 and HVTR-PG80v2.eJ41) were found to be resistant to its contemporaneous plasma antibodies, while Env proteins obtained from visit 1 plasma (HVTR-PG80v1.eJ7 and HVTR-PG80v1.eJ19) were found to be modestly sensitive to visit 2 autologous G37080 plasma antibodies. To facilitate mapping G37080 BCN antibody specificity, we prepared chimeric Envs between a sensitive (HVTR-PG80v1.eJ7 and HVTR-PG80v1.eJ19) and a resistant (HVTR-PG80v2.eJ38) autologous Env by first swapping the V1V2 regions, as their amino acid sequences differed maximally in this region (Fig. 4B). As shown in Table 4, the insertion of the V1V2 sequences of HVTR-PG80v1.eJ7 and HVTR-PG80v1.eJ19 into HVTR-PG80v2.eJ38 conferred Env-pseudotyped viruses expressing HVTR-PG80v2.eJ38 Env with sensitivity to G37080 visit 2 plasma antibodies enhanced by >25- and >12-fold, respectively. Conversely, the neutralization susceptibilities of the Env-pseudotyped viruses expressing HVTR-PG80v1.eJ7 and HVTR-PG80v1.eJ19, which contained HVTR-PG80v2.eJ38 V1V2 sequence corresponding to visit 2 G37080 plasma, were found to be reduced by >45- and >23-fold, respectively. We noted that alterations of regions other than the V1V2 loop in the autologous Env did not confer any change in neutralization sensitivity (Table 4). To further specify residues in the V1V2 loop associated with neutralization sensitivity and resistance of autologous Envs, chimeric Envs and point mutants were prepared and tested for their degree of modulation in susceptibility to autologous G37080 plasma obtained from the second visit. As shown in Table 4, we found that the V1 sequence, but not the V2 sequence, of the sensitive Envs (HVTR-PG80v1.eJ7 and HVTR-PG80v1.eJ19) increased sensitivity to G37080 BCN plasma antibodies by >50 and >37-fold, respectively, when transferred to the resistant HVTR-PG80v2.eJ38 Env. In agreement with this result, V1 of HVTR-PG80v2.eJ38, when transferred into the sensitive Envs described above, increased neutralization resistance by >27- and >28-fold, respectively, to the G37080 visit 2 BCN plasma antibodies. We observed that the removal of a glycan at the 138 position in V1 (T140D) in HVTR-PG80v1.eJ19 mediated the enhanced sensitivity of this Env to G37080 plasma by 2.64-fold (Table 4). Concurrent with this observation, we found that the alteration of the V1 region of PG80v1.eJ19 with the T140D substitution in PG80v2.eJ38 Env exhibited enhanced susceptibility compared to that of the PG80v2.eJ38 Env chimera containing the PG80v1.eJ19 V1 loop, as shown in Table 4. Our data indicate that N138 glycan masks the PG80v1.eJ19 Env from being efficiently neutralized by the autologous plasma compared to that of its contemporaneous counterpart, PG80v1.eJ7 Env. Fine scanning of V1 regions of the autologous Envs further revealed that the N133 glycan motif and P147 residues in the PG80v2.eJ38 Env played a significant role in neutralization resistance to G37080 BCN autologous plasma antibodies (Fig. 4B). Interestingly, all of the V1 chimeras as well as the point mutants showed sensitivities to PG9 MAb comparable to those of their wild types (Table 5), indicating that the shifts in neutralization susceptibilities were not due to changes in Env conformation. Moreover, we noted that both the sensitive and the resistant autologous Envs contain T332 in the V3 base, clearly indicating that the absence of N332 was not associated with resistance to autologous neutralization. Similar observations were made with respect to N160, R166, and K169 amino acid residues, further consolidating that the neutralization conferred by G37080 BCN plasma antibodies was not associated with antibody targeting these epitopes in autologous Envs, and is likely the case for all of the Envs tested against G37080 plasma antibodies.

FIG 4.

(A) Neutralization susceptibility of autologous Envs to contemporaneous G37080 BCN plasma and its follow-up sample from the same donor. Neutralization titers (median ID50) were obtained by titrating pseudotyped viruses expressing autologous Envs obtained from visit 1 and follow-up G37080 plasma to contemporaneous plasma antibodies. Note that both of the Envs obtained from follow-up G37080 plasma (visit 2) were found to be resistant to contemporaneous autologous plasma, while Envs obtained from visit 1 G37080 plasma were found to be sensitive to follow-up plasma antibodies. (B) Alignment of V1V2 amino acid sequences of sensitive and resistant autologous Envs obtained at both visits was done by using seqpublish, available at the HIV Los Alamos database (www.hiv.lanl.gov). Key residues that mediate autologous neutralization resistance are highlighted.

TABLE 5.

Sensitivity of wild type, chimera, and point mutants of autologous Envs to PG9 MAb

| Env chimera and mutant | ID50 |

|---|---|

| PG80v1.eJ7 (wild type) | 0.12 |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (wild type) | 0.97 |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (T139A + T140D) | 0.77 |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (wild type) | 0.02 |

| PG80v1.eJ7 (V1) in v2.eJ38 | 0.04 |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (V1) in v2.eJ38 | 0.05 |

| PG80v1.eJ19 (V1) (T139A + T140D) in v2.eJ38 | 0.06 |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (N133D) | 0.01 |

| PG80v2.eJ38 (P147T) | 0.04 |

DISCUSSION

The identification of the molecular specificities of antibodies elicited in natural infection and that mediate neutralization breadth and potency is key in the design and development of suitable Env-based immunogens capable of eliciting similar antibody responses upon vaccination. In the present study, we characterized the molecular specificity of plasma antibodies obtained from an Indian elite neutralizer (G37080) infected with HIV-1 clade C that displayed exceptional cross-neutralization of different clades of distinct geographical origins. The G37080 plasma was found to contain the most broad and potent cross-neutralizing antibodies among the two hundred plasma samples obtained from Indian patients chronically infected with HIV-1. Plasma samples collected from the G37080 donor at two time points at 8 months apart showed similar neutralization breadth with modest increase in potency in the follow-up visit, indicating an association with the sustained maturation of antibody-producing B cells in this individual.

Since polyclonal plasma antibodies are not suitable for epitope mapping, we examined the specificity of the G37080 BCN plasma by making use of mutant viruses with specific point substitutions of known neutralizing epitopes with nonspecific amino acids and via depletion with monomeric and trimeric Envs in addition to MPER peptide. The G37080 plasma antibodies did not show dependence on the N160/K169 and N332 epitopes in the V2 apex and V3 base, respectively. Our data also are consistent with the target epitopes of the G37080 BCN antibodies being distinct from those which are recognized by 2G12 (74), PGT121-128 (17), and PGT130-131 and PGT135 (19) (e.g., residues at the following positions: 295, 297, 301, 332, 334, 386, 388, 392, 394, 448, and 450); thus, BCN G37080 antibodies appear to target a new epitope. Our data highlighting the N332-independent development of neutralizing antibodies in clade C-infected donor G37080 also differ from recent findings (57, 75–77) associating N332 with the development of broad and potent neutralizing antibody, especially in clade C infection in African donors. Moreover, recent studies indicating the role of K169 as a target of BCN antibodies obtained from a clade C-infected South African donor (41, 56) and the observation that vaccine-induced protection in the RV144 vaccine trial was associated with antibodies targeting epitopes, including K169 in the V2 apex (27, 78), prompted us to examine whether broad neutralization of the G37080 plasma antibodies also was dependent on the K169 epitope. In the present study, the neutralization potency of G37080 was unaffected by N160A/K169A knockout mutations, and we also observed that both sensitive and resistant autologous Envs obtained from both visits contain N160 and K169 in the V2 region. Hence, owing to the lack of association of neutralization breadth of the G37080 BCN antibodies with N160, K169, and N332 dependencies, our study further highlighted that there is a likelihood of differences in the development pathway of elicitation of broadly neutralizing antibodies in individuals infected with HIV-1 clade C, particularly those with ethnically distinct variants.

Wibmer et al. (41) recently demonstrated an association between the evolution of a broadly neutralizing antibody response in a clade C-infected donor with shifts in antibody specificities from the recognition of epitopes in V2 to the CD4bs. In the present study, the G37080 neutralizing plasma antibodies obtained from both visits were found not to be absorbed by the TripleMut (66, 79) and RSC3 (22) core proteins, which effectively absorb antibodies directed to the CD4bs. This result indicates a lack of development of CD4bs-directed neutralizing antibodies during the disease course in the G37080 donor. Additionally, the absence of MPER-directed antibodies from G37080 plasma was found, although a negligible antibody titer (1:300 reciprocal dilutions) to the HIV2/HIV1 (C1C) chimera was observed with plasma samples from both visits. However, the neutralization breadth of the G37080 plasma was not found to be associated with the presence of MPER-directed antibody. Nonetheless, we do not rule out the possibility that in the further course of infection, this donor may be able to develop MPER-directed antibodies.

Recent studies have shown that neutralizing antibodies that target conformational epitopes bind exclusively to the cleaved near-native trimeric Envs (15, 64, 80, 81). In the present study, we found that the absorption of G37080 plasma antibodies to soluble trimeric BG505-SOSIP.664 Env was associated with the depletion of neutralizing activity in G37080 BCN plasma. However, we do not rule out the possibility of the presence of 39F-, 19b-, and 14e-like nonneutralizing antibodies that were reported to bind to BG505-SOSIP.664 trimeric Env (69). Our findings indicate that the G37080 BCN antibodies target conformational epitopes in gp120. Our observation also highlights that native-like trimeric Envs, such as BG505-SOSIP.664, can be utilized in selecting antigen-specific memory B cells, as reported earlier (82), from donor G37080 toward isolation of MAb correlating with broad neutralization displayed by the plasma antibodies.

We made use of env clones obtained from autologous G37080 plasma from both time points to refine the fine specificity of the G37080 BCN plasma antibodies. By examining chimeric Envs and mutant viruses, we identified key residues in the V1 loop associated with neutralization resistance. Interestingly, the Env chimera and mutant viruses showed susceptibility to PG9 MAb comparable to that of their respective wild-type Envs, indicating that they did not alter Env conformation. We identified a glycan at the 133 position and a proline residue at the 147 position within the V1 loop of the resistant Env (PG80v2.eJ38) that were found to be associated with neutralization escape, which indicated that these are contact sites for the G37080 BCN plasma antibodies. Thus, from our study we conclude that changes in V1 loop sequence are associated with the escape of autologous viruses to the BCN G37080 plasma. Additionally, an examination of the degree of susceptibilities of pseudoviruses expressing chimeric heterologous Envs to the G37080 plasma revealed that the BCN plasma antibodies predominantly target epitopes in the V1V2 region in gp120. However, we do not rule out the possibility of the contribution of other discontinuous epitopes in gp120 in mediating neutralization breadth. The isolation and identification of monoclonal antibodies from this elite neutralizer donor (G37080) will help precisely map specific epitopes associated with neutralization breadth and potency.

In summary, we identified an HIV-1-infected elite neutralizer whose plasma showed exceptional neutralization breadth, and we provided evidence that it targets novel conformational epitopes on trimeric Env, predominantly in the V1V2 region, not reported previously. Moreover, the neutralization resistance of the autologous Envs to G37080 plasma is associated with substitutions of novel residues within the V1 loop that form the key contact points of the BCN plasma antibody. The identification of novel epitopes associated with broad neutralization of HIV-1, in particular the major circulating clade C strains, will significantly contribute to efforts toward effective immunogen design.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank all of the Protocol G study participants registered with YRG Care, Chennai, all of the research staff members at the Protocol G clinical center at YRG Care, Chennai, and all of the IAVI Protocol G team members. We sincerely thank Christopher Parks, IAVI Design and Development Laboratory, for providing valuable input in preparing the manuscript, and we also thank G. Balakrish Nair and Sudhanshu Vrati (THSTI), Shreyasi Chatterjee, and all of the HVTR laboratory members for support. We thank Albert Cupo, John P. Moore, and the members the SOSIP trimer HIVRAD team, Weill Cornell Medical College, New York, for providing us with BG505.SOSIP.664 plasmid DNA and purified protein. We thank David Montefiori, Lynn Morris, Pascal Poignard, and Richard Wyatt for making available many reagents used in our study. The following reagent was obtained through the NIH AIDS Reagent Program, Division of AIDS, NIAID, NIH, from John C. Kappes and Xiaoyun Wu: pSG3 env.

IAVI's work was made possible by generous support from many donors, including the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Denmark, Irish Aid, the Ministry of Finance of Japan, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the Netherlands, the Norwegian Agency for Development Cooperation (NORAD), the United Kingdom Department for International Development (DFID), and the United States Agency for International Development (USAID). The full list of IAVI donors is available at www.iavi.org. The contents are the responsibility of the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.

The International AIDS Vaccine Initiative has filed a patent relating to the autologous HIV-1 clade C envelope clones (J. Bhattacharya, S. Deshpande, S. Patil, R. Kumar, and B. K. Chakrabarti, U.S. patent application 62/254,971).

Funding Statement

This study was made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) through the IAVI, support from a THSTI-IAVI HIV Vaccine Design Program grant through the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, in part by a grant from the Department of Science and Technology, Government of India (DST/INT/SAFR/Mega-P3/2011 to J.B.), and in part by a DBT National Bioscience Research Award [BT/HRD/NBA34/01/2012-13(iv) to J.B.]. The funders had no role in study design, data collection and interpretation, or the decision to submit the work for publication.

REFERENCES

- 1.Caskey M, Klein F, Lorenzi JC, Seaman MS, West AP Jr, Buckley N, Kremer G, Nogueira L, Braunschweig M, Scheid JF, Horwitz JA, Shimeliovich I, Ben-Avraham S, Witmer-Pack M, Platten M, Lehmann C, Burke LA, Hawthorne T, Gorelick RJ, Walker BD, Keler T, Gulick RM, Fatkenheuer G, Schlesinger SJ, Nussenzweig MC. 2015. Viraemia suppressed in HIV-1-infected humans by broadly neutralizing antibody 3BNC117. Nature 522:487–491. doi: 10.1038/nature14411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Esparza J. 2013. A brief history of the global effort to develop a preventive HIV vaccine. Vaccine 31:3502–3518. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2013.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hraber P, Seaman MS, Bailer RT, Mascola JR, Montefiori DC, Korber BT. 2014. Prevalence of broadly neutralizing antibody responses during chronic HIV-1 infection. AIDS 28:163–169. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000000106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Klein F, Mouquet H, Dosenovic P, Scheid JF, Scharf L, Nussenzweig MC. 2013. Antibodies in HIV-1 vaccine development and therapy. Science 341:1199–1204. doi: 10.1126/science.1241144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koff WC, Russell ND, Walport M, Feinberg MB, Shiver JW, Karim SA, Walker BD, McGlynn MG, Nweneka CV, Nabel GJ. 2013. Accelerating the development of a safe and effective HIV vaccine: HIV vaccine case study for the decade of vaccines. Vaccine 31(Suppl 2):B204–B208. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2012.10.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ. 2013. Broadly neutralizing antibodies and the search for an HIV-1 vaccine: the end of the beginning. Nat Rev Immunol 13:693–701. doi: 10.1038/nri3516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braibant M, Brunet S, Costagliola D, Rouzioux C, Agut H, Katinger H, Autran B, Barin F. 2006. Antibodies to conserved epitopes of the HIV-1 envelope in sera from long-term non-progressors: prevalence and association with neutralizing activity. AIDS 20:1923–1930. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000247113.43714.5e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donners H, Willems B, Beirnaert E, Colebunders R, Davis D, van der Groen G. 2002. Cross-neutralizing antibodies against primary isolates in African women infected with HIV-1. AIDS 16:501–503. doi: 10.1097/00002030-200202150-00030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gray ES, Madiga MC, Hermanus T, Moore PL, Wibmer CK, Tumba NL, Werner L, Mlisana K, Sibeko S, Williamson C, Abdool Karim SS, Morris L. 2011. The neutralization breadth of HIV-1 develops incrementally over four years and is associated with CD4+ T cell decline and high viral load during acute infection. J Virol 85:4828–4840. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00198-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li Y, Svehla K, Louder MK, Wycuff D, Phogat S, Tang M, Migueles SA, Wu X, Phogat A, Shaw GM, Connors M, Hoxie J, Mascola JR, Wyatt R. 2009. Analysis of neutralization specificities in polyclonal sera derived from human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol 83:1045–1059. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01992-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Richman DD, Wrin T, Little SJ, Petropoulos CJ. 2003. Rapid evolution of the neutralizing antibody response to HIV type 1 infection. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 100:4144–4149. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0630530100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sather DN, Armann J, Ching LK, Mavrantoni A, Sellhorn G, Caldwell Z, Yu X, Wood B, Self S, Kalams S, Stamatatos L. 2009. Factors associated with the development of cross-reactive neutralizing antibodies during human immunodeficiency virus type 1 infection. J Virol 83:757–769. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02036-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simek MD, Rida W, Priddy FH, Pung P, Carrow E, Laufer DS, Lehrman JK, Boaz M, Tarragona-Fiol T, Miiro G, Birungi J, Pozniak A, McPhee DA, Manigart O, Karita E, Inwoley A, Jaoko W, Dehovitz J, Bekker LG, Pitisuttithum P, Paris R, Walker LM, Poignard P, Wrin T, Fast PE, Burton DR, Koff WC. 2009. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 elite neutralizers: individuals with broad and potent neutralizing activity identified by using a high-throughput neutralization assay together with an analytical selection algorithm. J Virol 83:7337–7348. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00110-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stamatatos L, Morris L, Burton DR, Mascola JR. 2009. Neutralizing antibodies generated during natural HIV-1 infection: good news for an HIV-1 vaccine? Nat Med 15:866–870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Falkowska E, Le KM, Ramos A, Doores KJ, Lee JH, Blattner C, Ramirez A, Derking R, MJ van Gils Liang CH, McBride R, von Bredow B, Shivatare SS, Wu CY, Chan-Hui PY, Liu Y, Feizi T, Zwick MB, Koff WC, Seaman MS, Swiderek K, Moore JP, Evans D, Paulson JC, Wong CH, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Sanders RW, Poignard P, Burton DR. 2014. Broadly neutralizing HIV antibodies define a glycan-dependent epitope on the prefusion conformation of gp41 on cleaved envelope trimers. Immunity 40:657–668. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang J, Ofek G, Laub L, Louder MK, Doria-Rose NA, Longo NS, Imamichi H, Bailer RT, Chakrabarti B, Sharma SK, Alam SM, Wang T, Yang Y, Zhang B, Migueles SA, Wyatt R, Haynes BF, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Connors M. 2012. Broad and potent neutralization of HIV-1 by a gp41-specific human antibody. Nature 491:406–412. doi: 10.1038/nature11544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Julien JP, Sok D, Khayat R, Lee JH, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Ramos A, Diwanji DC, Pejchal R, Cupo A, Katpally U, Depetris RS, Stanfield RL, McBride R, Marozsan AJ, Paulson JC, Sanders RW, Moore JP, Burton DR, Poignard P, Ward AB, Wilson IA. 2013. Broadly neutralizing antibody PGT121 allosterically modulates CD4 binding via recognition of the HIV-1 gp120 V3 base and multiple surrounding glycans. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003342. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Scharf L, Scheid JF, Lee JH, West AP Jr, Chen C, Gao H, Gnanapragasam PN, Mares R, Seaman MS, Ward AB, Nussenzweig MC, Bjorkman PJ. 2014. Antibody 8ANC195 reveals a site of broad vulnerability on the HIV-1 envelope spike. Cell Rep 7:785–795. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walker LM, Huber M, Doores KJ, Falkowska E, Pejchal R, Julien JP, Wang SK, Ramos A, Chan-Hui PY, Moyle M, Mitcham JL, Hammond PW, Olsen OA, Phung P, Fling S, Wong CH, Phogat S, Wrin T, Simek MD, Protocol G Principal Investigators, Koff WC, Wilson IA, Burton DR, Poignard P. 2011. Broad neutralization coverage of HIV by multiple highly potent antibodies. Nature 477:466–470. doi: 10.1038/nature10373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Walker LM, Phogat SK, Chan-Hui PY, Wagner D, Phung P, Goss JL, Wrin T, Simek MD, Fling S, Mitcham JL, Lehrman JK, Priddy FH, Olsen OA, Frey SM, Hammond PW, Kaminsky S, Zamb T, Moyle M, Koff WC, Poignard P, Burton DR. 2009. Broad and potent neutralizing antibodies from an African donor reveal a new HIV-1 vaccine target. Science 326:285–289. doi: 10.1126/science.1178746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walker LM, Simek MD, Priddy F, Gach JS, Wagner D, Zwick MB, Phogat SK, Poignard P, Burton DR. 2010. A limited number of antibody specificities mediate broad and potent serum neutralization in selected HIV-1 infected individuals. PLoS Pathog 6:e1001028. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu X, Yang ZY, Li Y, Hogerkorp CM, Schief WR, Seaman MS, Zhou T, Schmidt SD, Wu L, Xu L, Longo NS, McKee K, O'Dell S, Louder MK, Wycuff DL, Feng Y, Nason M, Doria-Rose N, Connors M, Kwong PD, Roederer M, Wyatt RT, Nabel GJ, Mascola JR. 2010. Rational design of envelope identifies broadly neutralizing human monoclonal antibodies to HIV-1. Science 329:856–861. doi: 10.1126/science.1187659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu X, Zhou T, Zhu J, Zhang B, Georgiev I, Wang C, Chen X, Longo NS, Louder M, McKee K, O'Dell S, Perfetto S, Schmidt SD, Shi W, Wu L, Yang Y, Yang ZY, Yang Z, Zhang Z, Bonsignori M, Crump JA, Kapiga SH, Sam NE, Haynes BF, Simek M, Burton DR, Koff WC, Doria-Rose NA, Connors M, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Mullikin JC, Nabel GJ, Roederer M, Shapiro L, Kwong PD, Mascola JR. 2011. Focused evolution of HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies revealed by structures and deep sequencing. Science 333:1593–1602. doi: 10.1126/science.1207532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diskin R, Scheid JF, Marcovecchio PM, West AP Jr, Klein F, Gao H, Gnanapragasam PN, Abadir A, Seaman MS, Nussenzweig MC, Bjorkman PJ. 2011. Increasing the potency and breadth of an HIV antibody by using structure-based rational design. Science 334:1289–1293. doi: 10.1126/science.1213782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Klein F, Gaebler C, Mouquet H, Sather DN, Lehmann C, Scheid JF, Kraft Z, Liu Y, Pietzsch J, Hurley A, Poignard P, Feizi T, Morris L, Walker BD, Fatkenheuer G, Seaman MS, Stamatatos L, Nussenzweig MC. 2012. Broad neutralization by a combination of antibodies recognizing the CD4 binding site and a new conformational epitope on the HIV-1 envelope protein. J Exp Med 209:1469–1479. doi: 10.1084/jem.20120423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheid JF, Mouquet H, Ueberheide B, Diskin R, Klein F, Oliveira TY, Pietzsch J, Fenyo D, Abadir A, Velinzon K, Hurley A, Myung S, Boulad F, Poignard P, Burton DR, Pereyra F, Ho DD, Walker BD, Seaman MS, Bjorkman PJ, Chait BT, Nussenzweig MC. 2011. Sequence and structural convergence of broad and potent HIV antibodies that mimic CD4 binding. Science 333:1633–1637. doi: 10.1126/science.1207227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao HX, Bonsignori M, Alam SM, McLellan JS, Tomaras GD, Moody MA, Kozink DM, Hwang KK, Chen X, Tsao CY, Liu P, Lu X, Parks RJ, Montefiori DC, Ferrari G, Pollara J, Rao M, Peachman KK, Santra S, Letvin NL, Karasavvas N, Yang ZY, Dai K, Pancera M, Gorman J, Wiehe K, Nicely NI, Rerks-Ngarm S, Nitayaphan S, Kaewkungwal J, Pitisuttithum P, Tartaglia J, Sinangil F, Kim JH, Michael NL, Kepler TB, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Nabel GJ, Pinter A, Zolla-Pazner S, Haynes BF. 2013. Vaccine induction of antibodies against a structurally heterogeneous site of immune pressure within HIV-1 envelope protein variable regions 1 and 2. Immunity 38:176–186. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pejchal R, Doores KJ, Walker LM, Khayat R, Huang PS, Wang SK, Stanfield RL, Julien JP, Ramos A, Crispin M, Depetris R, Katpally U, Marozsan A, Cupo A, Maloveste S, Liu Y, McBride R, Ito Y, Sanders RW, Ogohara C, Paulson JC, Feizi T, Scanlan CN, Wong CH, Moore JP, Olson WC, Ward AB, Poignard P, Schief WR, Burton DR, Wilson IA. 2011. A potent and broad neutralizing antibody recognizes and penetrates the HIV glycan shield. Science 334:1097–1103. doi: 10.1126/science.1213256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Blattner C, Lee JH, Sliepen K, Derking R, Falkowska E, de la Pena AT, Cupo A, Julien JP, van Gils M, Lee PS, Peng W, Paulson JC, Poignard P, Burton DR, Moore JP, Sanders RW, Wilson IA, Ward AB. 2014. Structural delineation of a quaternary, cleavage-dependent epitope at the gp41-gp120 interface on intact HIV-1 Env trimers. Immunity 40:669–680. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2014.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Morris L, Chen X, Alam M, Tomaras G, Zhang R, Marshall DJ, Chen B, Parks R, Foulger A, Jaeger F, Donathan M, Bilska M, Gray ES, Abdool Karim SS, Kepler TB, Whitesides J, Montefiori D, Moody MA, Liao HX, Haynes BF. 2011. Isolation of a human anti-HIV gp41 membrane proximal region neutralizing antibody by antigen-specific single B cell sorting. PLoS One 6:e23532. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nelson JD, Brunel FM, Jensen R, Crooks ET, Cardoso RM, Wang M, Hessell A, Wilson IA, Binley JM, Dawson PE, Burton DR, Zwick MB. 2007. An affinity-enhanced neutralizing antibody against the membrane-proximal external region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 recognizes an epitope between those of 2F5 and 4E10. J Virol 81:4033–4043. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02588-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zwick MB, Labrijn AF, Wang M, Spenlehauer C, Saphire EO, Binley JM, Moore JP, Stiegler G, Katinger H, Burton DR, Parren PW. 2001. Broadly neutralizing antibodies targeted to the membrane-proximal external region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 glycoprotein gp41. J Virol 75:10892–10905. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.22.10892-10905.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chaillon A, Braibant M, Moreau T, Thenin S, Moreau A, Autran B, Barin F. 2011. The V1V2 domain and an N-linked glycosylation site in the V3 loop of the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein modulate neutralization sensitivity to the human broadly neutralizing antibody 2G12. J Virol 85:3642–3648. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02424-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Doria-Rose NA, Georgiev I, O'Dell S, Chuang GY, Staupe RP, McLellan JS, Gorman J, Pancera M, Bonsignori M, Haynes BF, Burton DR, Koff WC, Kwong PD, Mascola JR. 2012. A short segment of the HIV-1 gp120 V1/V2 region is a major determinant of resistance to V1/V2 neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 86:8319–8323. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00696-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Doria-Rose NA, Schramm CA, Gorman J, Moore PL, Bhiman JN, DeKosky BJ, Ernandes MJ, Georgiev IS, Kim HJ, Pancera M, Staupe RP, Altae-Tran HR, Bailer RT, Crooks ET, Cupo A, Druz A, Garrett NJ, Hoi KH, Kong R, Louder MK, Longo NS, McKee K, Nonyane M, O'Dell S, Roark RS, Rudicell RS, Schmidt SD, Sheward DJ, Soto C, Wibmer CK, Yang Y, Zhang Z, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Mullikin JC, Binley JM, Sanders RW, Wilson IA, Moore JP, Ward AB, Georgiou G, Williamson C, Abdool Karim SS, Morris L, Kwong PD, Shapiro L, Mascola JR. 2014. Developmental pathway for potent V1V2-directed HIV-neutralizing antibodies. Nature 509:55–62. doi: 10.1038/nature13036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Harrington PR, Nelson JA, Kitrinos KM, Swanstrom R. 2007. Independent evolution of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 env V1/V2 and V4/V5 hypervariable regions during chronic infection. J Virol 81:5413–5417. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02554-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Moore PL, Gray ES, Choge IA, Ranchobe N, Mlisana K, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C, Morris L. 2008. The c3-v4 region is a major target of autologous neutralizing antibodies in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C infection. J Virol 82:1860–1869. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02187-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rusert P, Krarup A, Magnus C, Brandenberg OF, Weber J, Ehlert AK, Regoes RR, Gunthard HF, Trkola A. 2011. Interaction of the gp120 V1V2 loop with a neighboring gp120 unit shields the HIV envelope trimer against cross-neutralizing antibodies. J Exp Med 208:1419–1433. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sagar M, Wu X, Lee S, Overbaugh J. 2006. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 V1-V2 envelope loop sequences expand and add glycosylation sites over the course of infection, and these modifications affect antibody neutralization sensitivity. J Virol 80:9586–9598. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00141-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.van Gils MJ, Bunnik EM, Boeser-Nunnink BD, Burger JA, Terlouw-Klein M, Verwer N, Schuitemaker H. 2011. Longer V1V2 region with increased number of potential N-linked glycosylation sites in the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein protects against HIV-specific neutralizing antibodies. J Virol 85:6986–6995. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00268-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wibmer CK, Bhiman JN, Gray ES, Tumba N, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C, Morris L, Moore PL. 2013. Viral escape from HIV-1 neutralizing antibodies drives increased plasma neutralization breadth through sequential recognition of multiple epitopes and immunotypes. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003738. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Alter G, Barouch DH. 2015. Natural evolution of broadly neutralizing antibodies. Cell 161:427–428. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doores KJ, Kong L, Krumm SA, Le KM, Sok D, Laserson U, Garces F, Poignard P, Wilson IA, Burton DR. 2015. Two classes of broadly neutralizing antibodies within a single lineage directed to the high-mannose patch of HIV envelope. J Virol 89:1105–1118. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02905-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Doria-Rose NA, Joyce MG. 2015. Strategies to guide the antibody affinity maturation process. Curr Opin Virol 11:137–147. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Fera D, Schmidt AG, Haynes BF, Gao F, Liao HX, Kepler TB, Harrison SC. 2014. Affinity maturation in an HIV broadly neutralizing B-cell lineage through reorientation of variable domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:10275–10280. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1409954111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Horiya S, Bailey JK, Temme JS, Guillen Schlippe YV, Krauss IJ. 2014. Directed evolution of multivalent glycopeptides tightly recognized by HIV antibody 2G12. J Am Chem Soc 136:5407–5415. doi: 10.1021/ja500678v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mikell I, Stamatatos L. 2012. Evolution of cross-neutralizing antibody specificities to the CD4-BS and the carbohydrate cloak of the HIV Env in an HIV-1-infected subject. PLoS One 7:e49610. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0049610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sather DN, Carbonetti S, Malherbe DC, Pissani F, Stuart AB, Hessell AJ, Gray MD, Mikell I, Kalams SA, Haigwood NL, Stamatatos L. 2014. Emergence of broadly neutralizing antibodies and viral coevolution in two subjects during the early stages of infection with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 88:12968–12981. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01816-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wu X, Zhang Z, Schramm CA, Joyce MG, Do Kwon Y, Zhou T, Sheng Z, Zhang B, O'Dell S, McKee K, Georgiev IS, Chuang GY, Longo NS, Lynch RM, Saunders KO, Soto C, Srivatsan S, Yang Y, Bailer RT, Louder MK, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Mullikin JC, Connors M, Kwong PD, Mascola JR, Shapiro L. 2015. Maturation and diversity of the VRC01-antibody lineage over 15 years of chronic HIV-1 infection. Cell 161:470–485. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.03.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhu J, Ofek G, Yang Y, Zhang B, Louder MK, Lu G, McKee K, Pancera M, Skinner J, Zhang Z, Parks R, Eudailey J, Lloyd KE, Blinn J, Alam SM, Haynes BF, Simek M, Burton DR, Koff WC, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program, Mullikin JC, Mascola JR, Shapiro L, Kwong PD. 2013. Mining the antibodyome for HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies with next-generation sequencing and phylogenetic pairing of heavy/light chains. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:6470–6475. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1219320110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Basu D, Kraft CS, Murphy MK, Campbell PJ, Yu T, Hraber PT, Irene C, Pinter A, Chomba E, Mulenga J, Kilembe W, Allen SA, Derdeyn CA, Hunter E. 2012. HIV-1 subtype C superinfected individuals mount low autologous neutralizing antibody responses prior to intrasubtype superinfection. Retrovirology 9:76. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-9-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gray ES, Meyers T, Gray G, Montefiori DC, Morris L. 2006. Insensitivity of paediatric HIV-1 subtype C viruses to broadly neutralising monoclonal antibodies raised against subtype B. PLoS Med 3:e255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gray ES, Moody MA, Wibmer CK, Chen X, Marshall D, Amos J, Moore PL, Foulger A, Yu JS, Lambson B, Abdool Karim S, Whitesides J, Tomaras GD, Haynes BF, Morris L, Liao HX. 2011. Isolation of a monoclonal antibody that targets the alpha-2 helix of gp120 and represents the initial autologous neutralizing-antibody response in an HIV-1 subtype C-infected individual. J Virol 85:7719–7729. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00563-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Gray ES, Moore PL, Choge IA, Decker JM, Bibollet-Ruche F, Li H, Leseka N, Treurnicht F, Mlisana K, Shaw GM, Karim SS, Williamson C, Morris L. 2007. Neutralizing antibody responses in acute human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C infection. J Virol 81:6187–6196. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00239-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Gray ES, Taylor N, Wycuff D, Moore PL, Tomaras GD, Wibmer CK, Puren A, DeCamp A, Gilbert PB, Wood B, Montefiori DC, Binley JM, Shaw GM, Haynes BF, Mascola JR, Morris L. 2009. Antibody specificities associated with neutralization breadth in plasma from human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C-infected blood donors. J Virol 83:8925–8937. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00758-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Moore PL, Gray ES, Sheward D, Madiga M, Ranchobe N, Lai Z, Honnen WJ, Nonyane M, Tumba N, Hermanus T, Sibeko S, Mlisana K, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C, Pinter A, Morris L. 2011. Potent and broad neutralization of HIV-1 subtype C by plasma antibodies targeting a quaternary epitope including residues in the V2 loop. J Virol 85:3128–3141. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02658-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore PL, Gray ES, Wibmer CK, Bhiman JN, Nonyane M, Sheward DJ, Hermanus T, Bajimaya S, Tumba NL, Abrahams MR, Lambson BE, Ranchobe N, Ping L, Ngandu N, Abdool Karim Q, Abdool Karim SS, Swanstrom RI, Seaman MS, Williamson C, Morris L. 2012. Evolution of an HIV glycan-dependent broadly neutralizing antibody epitope through immune escape. Nat Med 18:1688–1692. doi: 10.1038/nm.2985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moore PL, Ranchobe N, Lambson BE, Gray ES, Cave E, Abrahams MR, Bandawe G, Mlisana K, Abdool Karim SS, Williamson C, Morris L. 2009. Limited neutralizing antibody specificities drive neutralization escape in early HIV-1 subtype C infection. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000598. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Overbaugh J, Morris L. 2012. The antibody response against HIV-1. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med 2:a007039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Rademeyer C, Moore PL, Taylor N, Martin DP, Choge IA, Gray ES, Sheppard HW, Gray C, Morris L, Williamson C. 2007. Genetic characteristics of HIV-1 subtype C envelopes inducing cross-neutralizing antibodies. Virology 368:172–181. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2007.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rong R, Bibollet-Ruche F, Mulenga J, Allen S, Blackwell JL, Derdeyn CA. 2007. Role of V1V2 and other human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope domains in resistance to autologous neutralization during clade C infection. J Virol 81:1350–1359. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01839-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rong R, Li B, Lynch RM, Haaland RE, Murphy MK, Mulenga J, Allen SA, Pinter A, Shaw GM, Hunter E, Robinson JE, Gnanakaran S, Derdeyn CA. 2009. Escape from autologous neutralizing antibodies in acute/early subtype C HIV-1 infection requires multiple pathways. PLoS Pathog 5:e1000594. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ringe R, Das L, Choudhary I, Sharma D, Paranjape R, Chauhan VS, Bhattacharya J. 2012. Unique C2V3 sequence in HIV-1 envelope obtained from broadly neutralizing plasma of a slow progressing patient conferred enhanced virus neutralization. PLoS One 7:e46713. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ringe RP, Sanders RW, Yasmeen A, Kim HJ, Lee JH, Cupo A, Korzun J, Derking R, van Montfort T, Julien JP, Wilson IA, Klasse PJ, Ward AB, Moore JP. 2013. Cleavage strongly influences whether soluble HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimers adopt a native-like conformation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 110:18256–18261. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1314351110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Chung NP, Matthews K, Kim HJ, Ketas TJ, Golabek M, de Los Reyes K, Korzun J, Yasmeen A, Sanders RW, Klasse PJ, Wilson IA, Ward AB, Marozsan AJ, Moore JP, Cupo A. 2014. Stable 293 T and CHO cell lines expressing cleaved, stable HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimers for structural and vaccine studies. Retrovirology 11:33. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-11-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Feng Y, McKee K, Tran K, O'Dell S, Schmidt SD, Phogat A, Forsell MN, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Mascola JR, Wyatt RT. 2012. Biochemically defined HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein variant immunogens display differential binding and neutralizing specificities to the CD4-binding site. J Biol Chem 287:5673–5686. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.317776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Boliar S, Das S, Bansal M, Shukla BN, Patil S, Shrivastava T, Samal S, Goswami S, King CR, Bhattacharya J, Chakrabarti BK. 2015. An efficiently cleaved HIV-1 clade C Env selectively binds to neutralizing antibodies. PLoS One 10:e0122443. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ringe R, Thakar M, Bhattacharya J. 2010. Variations in autologous neutralization and CD4 dependence of b12 resistant HIV-1 clade C env clones obtained at different time points from antiretroviral naive Indian patients with recent infection. Retrovirology 7:76. doi: 10.1186/1742-4690-7-76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sanders RW, Derking R, Cupo A, Julien JP, Yasmeen A, de Val N, Kim HJ, Blattner C, de la Pena AT, Korzun J, Golabek M, de Los Reyes K, Ketas TJ, van Gils MJ, King CR, Wilson IA, Ward AB, Klasse PJ, Moore JP. 2013. A next-generation cleaved, soluble HIV-1 Env trimer, BG505 SOSIP.664 gp140, expresses multiple epitopes for broadly neutralizing but not non-neutralizing antibodies. PLoS Pathog 9:e1003618. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tomaras GD, Binley JM, Gray ES, Crooks ET, Osawa K, Moore PL, Tumba N, Tong T, Shen X, Yates NL, Decker J, Wibmer CK, Gao F, Alam SM, Easterbrook P, Abdool Karim S, Kamanga G, Crump JA, Cohen M, Shaw GM, Mascola JR, Haynes BF, Montefiori DC, Morris L. 2011. Polyclonal B cell responses to conserved neutralization epitopes in a subset of HIV-1-infected individuals. J Virol 85:11502–11519. doi: 10.1128/JVI.05363-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Patil S, Choudhary I, Chaudhary NK, Ringe R, Bansal M, Shukla BN, Boliar S, Chakrabarti BK, Bhattacharya J. 2014. Determinants in V2C2 region of HIV-1 clade C primary envelopes conferred altered neutralization susceptibilities to IgG1b12 and PG9 monoclonal antibodies in a context-dependent manner. Virology 462-463:266–272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Teng G, Papavasiliou FN. 2007. Immunoglobulin somatic hypermutation. Annu Rev Genet 41:107–120. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genet.41.110306.130340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Gray ES, Moore PL, Bibollet-Ruche F, Li H, Decker JM, Meyers T, Shaw GM, Morris L. 2008. 4E10-resistant variants in a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 subtype C-infected individual with an anti-membrane-proximal external region-neutralizing antibody response. J Virol 82:2367–2375. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02161-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Trkola A, Purtscher M, Muster T, Ballaun C, Buchacher A, Sullivan N, Srinivasan K, Sodroski J, Moore JP, Katinger H. 1996. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol 70:1100–1108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Guttman M, Cupo A, Julien JP, Sanders RW, Wilson IA, Moore JP, Lee KK. 2015. Antibody potency relates to the ability to recognize the closed, pre-fusion form of HIV Env. Nat Commun 6:6144. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kong L, Lee JH, Doores KJ, Murin CD, Julien JP, McBride R, Liu Y, Marozsan A, Cupo A, Klasse PJ, Hoffenberg S, Caulfield M, King CR, Hua Y, Le KM, Khayat R, Deller MC, Clayton T, Tien H, Feizi T, Sanders RW, Paulson JC, Moore JP, Stanfield RL, Burton DR, Ward AB, Wilson IA. 2013. Supersite of immune vulnerability on the glycosylated face of HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein gp120. Nat Struct Mol Biol 20:796–803. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.2594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Sok D, Doores KJ, Briney B, Le KM, Saye-Francisco KL, Ramos A, Kulp DW, Julien JP, Menis S, Wickramasinghe L, Seaman MS, Schief WR, Wilson IA, Poignard P, Burton DR. 2014. Promiscuous glycan site recognition by antibodies to the high-mannose patch of gp120 broadens neutralization of HIV. Sci Transl Med 6:236ra263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Rolland M, Edlefsen PT, Larsen BB, Tovanabutra S, Sanders-Buell E, Hertz T, deCamp AC, Carrico C, Menis S, Magaret CA, Ahmed H, Juraska M, Chen L, Konopa P, Nariya S, Stoddard JN, Wong K, Zhao H, Deng W, Maust BS, Bose M, Howell S, Bates A, Lazzaro M, O'Sullivan A, Lei E, Bradfield A, Ibitamuno G, Assawadarachai V, O'Connell RJ, de Souza MS, Nitayaphan S, Rerks-Ngarm S, Robb ML, McLellan JS, Georgiev I, Kwong PD, Carlson JM, Michael NL, Schief WR, Gilbert PB, Mullins JI, Kim JH. 2012. Increased HIV-1 vaccine efficacy against viruses with genetic signatures in Env V2. Nature 490:417–420. doi: 10.1038/nature11519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chakrabarti BK, Feng Y, Sharma SK, McKee K, Karlsson Hedestam GB, Labranche CC, Montefiori DC, Mascola JR, Wyatt RT. 2013. Robust neutralizing antibodies elicited by HIV-1 JRFL envelope glycoprotein trimers in nonhuman primates. J Virol 87:13239–13251. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01247-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Burton DR, Mascola JR. 2015. Antibody responses to envelope glycoproteins in HIV-1 infection. Nat Immunol 16:571–576. doi: 10.1038/ni.3158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Pancera M, Wyatt R. 2005. Selective recognition of oligomeric HIV-1 primary isolate envelope glycoproteins by potently neutralizing ligands requires efficient precursor cleavage. Virology 332:145–156. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.10.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Sok D, van Gils MJ, Pauthner M, Julien JP, Saye-Francisco KL, Hsueh J, Briney B, Lee JH, Le KM, Lee PS, Hua Y, Seaman MS, Moore JP, Ward AB, Wilson IA, Sanders RW, Burton DR. 2014. Recombinant HIV envelope trimer selects for quaternary-dependent antibodies targeting the trimer apex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:17624–17629. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1415789111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]