Abstract

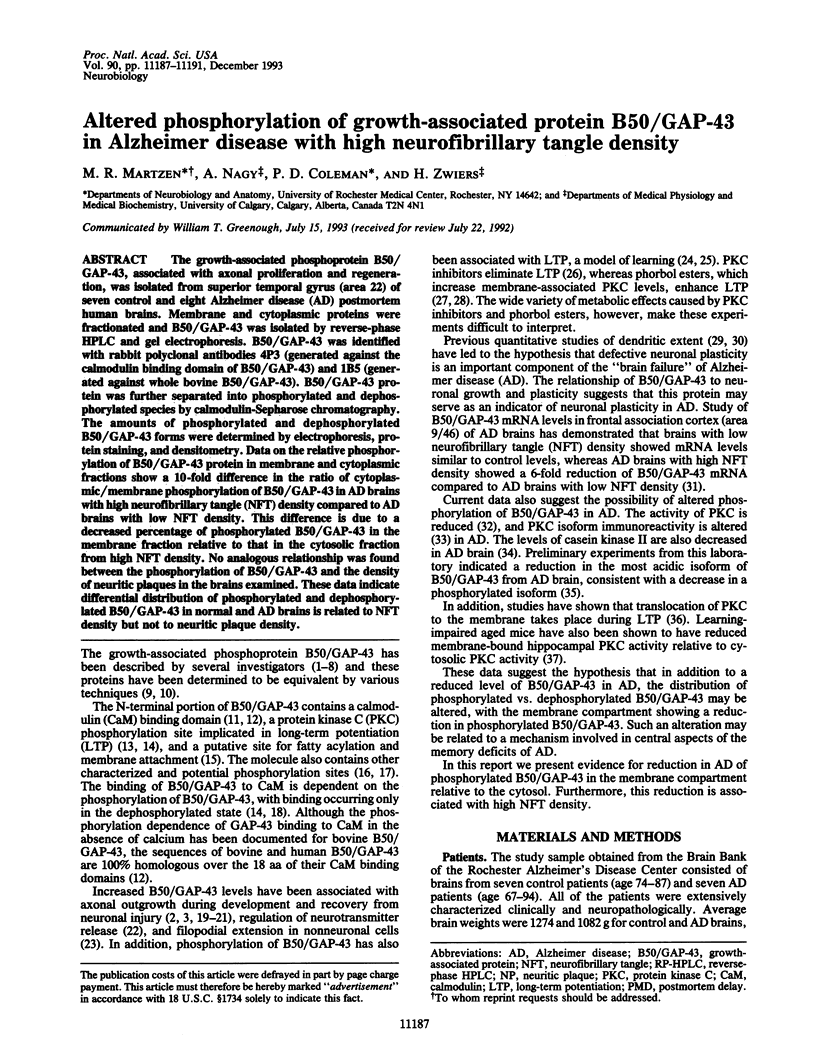

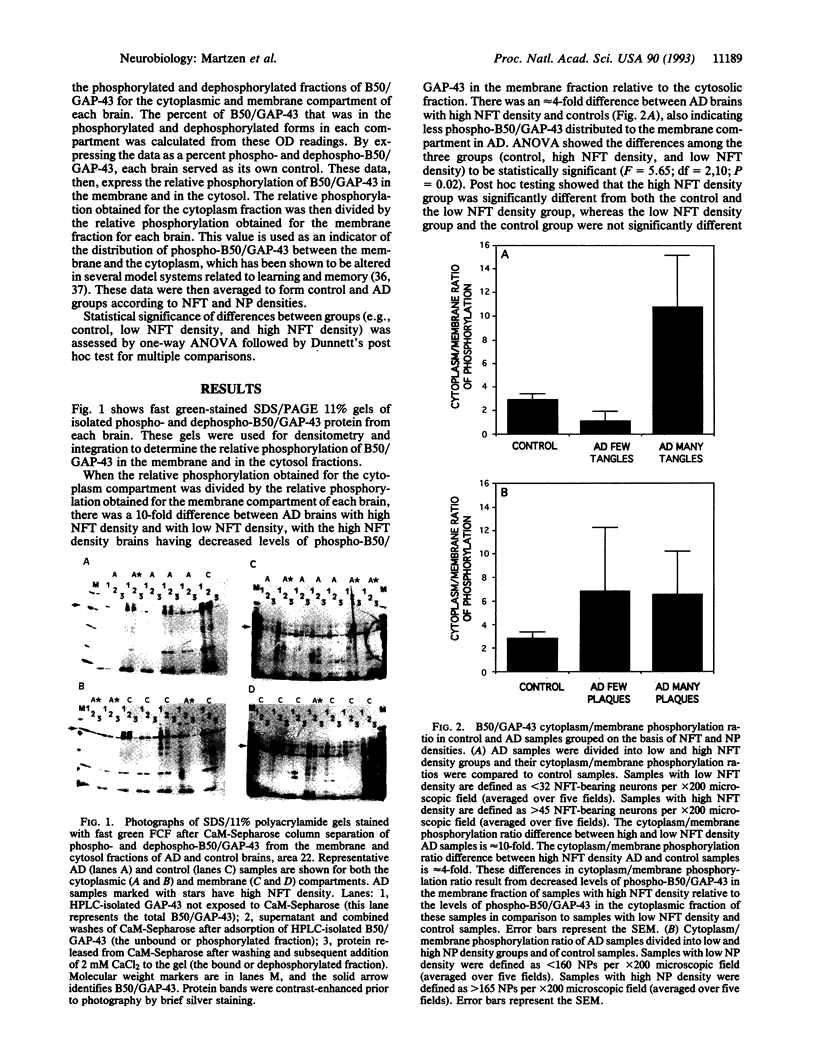

The growth-associated phosphoprotein B50/GAP-43, associated with axonal proliferation and regeneration, was isolated from superior temporal gyrus (area 22) of seven control and eight Alzheimer disease (AD) postmortem human brains. Membrane and cytoplasmic proteins were fractionated and B50/GAP-43 was isolated by reverse-phase HPLC and gel electrophoresis. B50/GAP-43 was identified with rabbit polyclonal antibodies 4P3 (generated against the calmodulin binding domain of B50/GAP-43) and 1B5 (generated against whole bovine B50/GAP-43). B50/GAP-43 protein was further separated into phosphorylated and dephosphorylated species by calmodulin-Sepharose chromatography. The amounts of phosphorylated and dephosphorylated B50/GAP-43 forms were determined by electrophoresis, protein staining, and densitometry. Data on the relative phosphorylation of B50/GAP-43 protein in membrane and cytoplasmic fractions show a 10-fold difference in the ratio of cytoplasmic/membrane phosphorylation of B50/GAP-43 in AD brains with high neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) density compared to AD brains with low NFT density. This difference is due to a decreased percentage of phosphorylated B50/GAP-43 in the membrane fraction relative to that in the cytosolic fraction from high NFT density. No analogous relationship was found between the phosphorylation of B50/GAP-43 and the density of neuritic plaques in the brains examined. These data indicate differential distribution of phosphorylated and dephosphorylated B50/GAP-43 in normal and AD brains is related to NFT density but not to neuritic plaque density.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Alexander K. A., Cimler B. M., Meier K. E., Storm D. R. Regulation of calmodulin binding to P-57. A neurospecific calmodulin binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1987 May 5;262(13):6108–6113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander K. A., Wakim B. T., Doyle G. S., Walsh K. A., Storm D. R. Identification and characterization of the calmodulin-binding domain of neuromodulin, a neurospecific calmodulin-binding protein. J Biol Chem. 1988 Jun 5;263(16):7544–7549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen T. J., Luetje C. W., Heideman W., Storm D. R. Purification of a novel calmodulin binding protein from bovine cerebral cortex membranes. Biochemistry. 1983 Sep 27;22(20):4615–4618. doi: 10.1021/bi00289a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel E. D., Byford M. F., Au D., Walsh K. A., Storm D. R. Identification of the protein kinase C phosphorylation site in neuromodulin. Biochemistry. 1990 Mar 6;29(9):2330–2335. doi: 10.1021/bi00461a017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Apel E. D., Litchfield D. W., Clark R. H., Krebs E. G., Storm D. R. Phosphorylation of neuromodulin (GAP-43) by casein kinase II. Identification of phosphorylation sites and regulation by calmodulin. J Biol Chem. 1991 Jun 5;266(16):10544–10551. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benowitz L. I., Lewis E. R. Increased transport of 44,000- to 49,000-dalton acidic proteins during regeneration of the goldfish optic nerve: a two-dimensional gel analysis. J Neurosci. 1983 Nov;3(11):2153–2163. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.03-11-02153.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan S. Y., Murakami K., Routtenberg A. Phosphoprotein F1: purification and characterization of a brain kinase C substrate related to plasticity. J Neurosci. 1986 Dec;6(12):3618–3627. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-12-03618.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chapman E. R., Au D., Alexander K. A., Nicolson T. A., Storm D. R. Characterization of the calmodulin binding domain of neuromodulin. Functional significance of serine 41 and phenylalanine 42. J Biol Chem. 1991 Jan 5;266(1):207–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggins P. J., Zwiers H. B-50 (GAP-43): biochemistry and functional neurochemistry of a neuron-specific phosphoprotein. J Neurochem. 1991 Apr;56(4):1095–1106. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1991.tb11398.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coggins P. J., Zwiers H. Evidence for a single protein kinase C-mediated phosphorylation site in rat brain protein B-50. J Neurochem. 1989 Dec;53(6):1895–1901. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1989.tb09259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dekker L. V., De Graan P. N., Oestreicher A. B., Versteeg D. H., Gispen W. H. Inhibition of noradrenaline release by antibodies to B-50 (GAP-43). Nature. 1989 Nov 2;342(6245):74–76. doi: 10.1038/342074a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz F., Ellis L., Pfenninger K. H. Nerve growth cones isolated from fetal rat brain. III. Calcium-dependent protein phosphorylation. J Neurosci. 1985 Jun;5(6):1402–1411. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.05-06-01402.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiri K. F., Pfenninger K. H., Willard M. B. Growth-associated protein, GAP-43, a polypeptide that is induced when neurons extend axons, is a component of growth cones and corresponds to pp46, a major polypeptide of a subcellular fraction enriched in growth cones. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1986 May;83(10):3537–3541. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.10.3537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodnight R. Aspects of protein phosphorylation in the nervous system with particular reference to synaptic transmission. Prog Brain Res. 1982;56:1–25. doi: 10.1016/S0079-6123(08)63766-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Routtenberg A., Lovinger D. M. Selective increase in phosphorylation of a 47-kDa protein (F1) directly related to long-term potentiation. Behav Neural Biol. 1985 Jan;43(1):3–11. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(85)91426-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene J. H., Jacobson R. D., Snipes G. J., McGuire C. B., Norden J. J., Freeman J. A. A protein induced during nerve growth (GAP-43) is a major component of growth-cone membranes. Science. 1986 Aug 15;233(4765):783–786. doi: 10.1126/science.3738509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene J. H., Willard M. Axonally transported proteins associated with axon growth in rabbit central and peripheral nervous systems. J Cell Biol. 1981 Apr;89(1):96–103. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.1.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skene J. H., Willard M. Changes in axonally transported proteins during axon regeneration in toad retinal ganglion cells. J Cell Biol. 1981 Apr;89(1):86–95. doi: 10.1083/jcb.89.1.86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spencer S. A., Schuh S. M., Liu W. S., Willard M. B. GAP-43, a protein associated with axon growth, is phosphorylated at three sites in cultured neurons and rat brain. J Biol Chem. 1992 May 5;267(13):9059–9064. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zuber M. X., Goodman D. W., Karns L. R., Fishman M. C. The neuronal growth-associated protein GAP-43 induces filopodia in non-neuronal cells. Science. 1989 Jun 9;244(4909):1193–1195. doi: 10.1126/science.2658062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwiers H., Wiegant V. M., Schotman P., Gispen W. H. ACTH-induced inhibition of endogenous rat brain protein phosphorylation in vitro: structure activity. Neurochem Res. 1978 Aug;3(4):455–463. doi: 10.1007/BF00966327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]