Abstract

IMPORTANCE

Serious illness impairs function and threatens survival. Patients facing serious illness value shared decision making, yet few decision aids address the needs of this population.

OBJECTIVE

To perform a systematic review of evidence about decision aids and other exportable tools that promote shared decision making in serious illness, thereby (1) identifying tools relevant to the treatment decisions of seriously ill patients and their caregivers, (2) evaluating the quality of evidence for these tools, and (3) summarizing their effect on outcomes and accessibility for clinicians.

EVIDENCE REVIEW

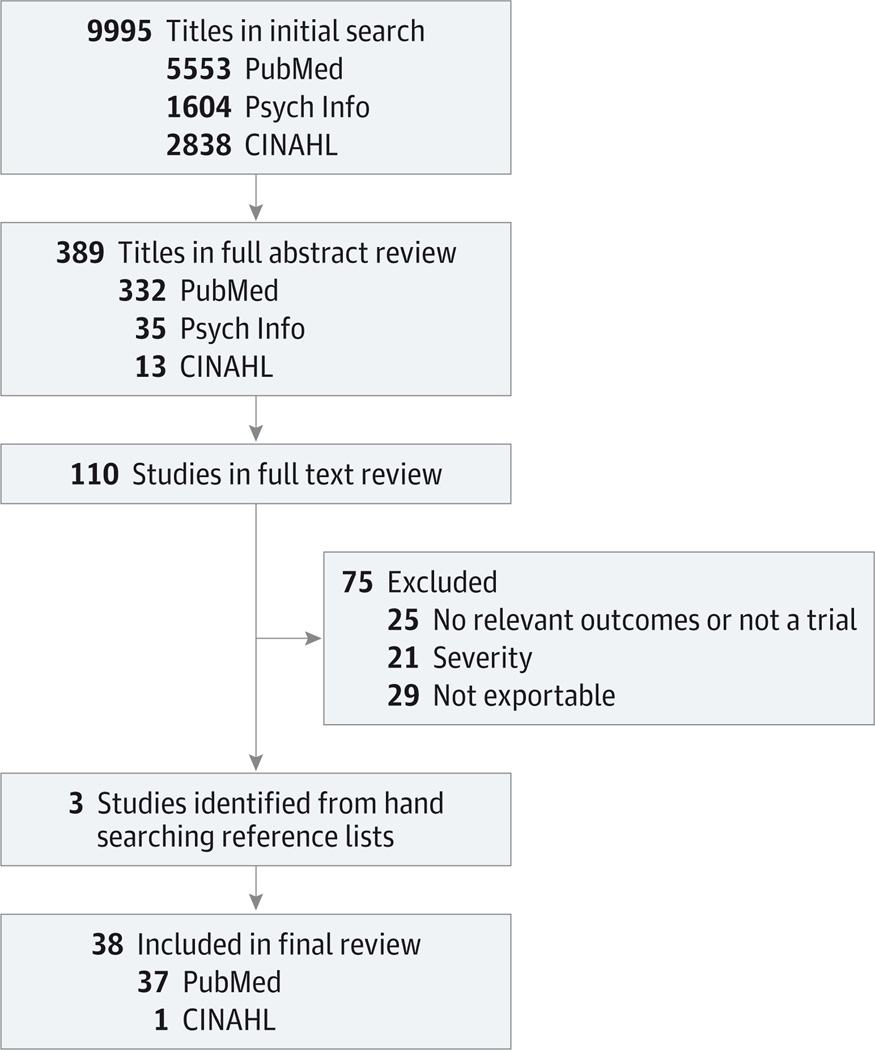

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychInfo from January 1, 1995, through October 31, 2014, and identified additional studies from reference lists and other systematic reviews. Clinical trials with random or nonrandom controls were included if they tested print, video, or web-based tools for advance care planning (ACP) or decision aids for serious illness. We extracted data on the study population, design, results, and risk for bias using the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria. Each tool was evaluated for its effect on patient outcomes and accessibility.

FINDINGS

Seventeen randomized clinical trials tested decision tools in serious illness. Nearly all the trials were of moderate or high quality and showed that decision tools improve patient knowledge and awareness of treatment choices. The available tools address ACP, palliative care and goals of care communication, feeding options in dementia, lung transplant in cystic fibrosis, and truth telling in terminal cancer. Five randomized clinical trials provided further evidence that decision tools improve ACP documentation, clinical decisions, and treatment received.

CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE

Clinicians can access and use evidence-based tools to engage seriously ill patients in shared decision making. This field of research is in an early stage; future research is needed to develop novel decision aids for other serious diagnoses and key decisions. Health care delivery organizations should prioritize the use of currently available tools that are evidence based and effective.

Serious illness raises the stakes for engaging patients and families in health care decisions.1–3 Patients with serious illness include those with critical life-threatening illness, advanced stages of major chronic diseases, or multimorbidity and frailty. They confront debilitating symptoms and impending threats to function, decisional capacity, and survival. Patients, caregivers, and health care practitioners identify communication and shared decision making as essential components of good care in serious illness.2 However, poor quality of communication between patients and practitioners limits the patients’ knowledge of prognosis and treatment options, management of symptoms, and use of treatments consistent with their preferences.4,5

Structured tools are a novel method to improve knowledge transfer and promote patient engagement in health care choices. Tools that use print, video, or web-based media are designed to share information about an illness and promote informed decisions about treatment. These tools are not a substitute for clinical communication, but are intended to prepare and empower patients and their families for shared decision making with clinicians. Some tools are designed to improve the patients’ knowledge about clinical issues. Other tools are formal decision aids, which are more highly structured to address the risks and benefits of and alternatives to treatment and are designed to prepare patients for their role in key decisions.6 Randomized clinical trials (RCTs) have shown that decision aids improve the quality and efficiency of decision making, increase comprehension and decisional participation, and decrease decisional conflict.7Despite the importance of shared decision making in serious illness, most formal decision aids have addressed the needs of healthier outpatients, and a recent Cochrane review excluded advance care planning (ACP) tools.8

No systematic review, to our knowledge, has synthesized the evidence for communication tools and decision aids in serious illness. We therefore sought to assess the quality and accessibility of decision aids and tools for ACP designed to empower and improve the care of patients with serious illness. To meet this objective, we conducted a systematic review of published clinical trials of decision aids and ACP tools to promote shared decision making in serious illness. The goals of this study are to (1) identify tools relevant to the needs of treatment decision making by seriously ill patients and their caregivers, (2) evaluate the quality of evidence for these tools, and (3) summarize their effect on patient-centered outcomes and accessibility of tools for clinicians.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

We searched PubMed, CINAHL, and PsychInfo from January1, 1995, through October 31, 2014, and identified additional studies from reference lists and relevant systematic reviews. Our electronic search strategy included the following terms using text word (tw) or MeSH fieldtags:(brochure*[tw]ORpamphlet*[tw]ORbooklet*[tw]ORcom-municationtool*[tw]OR DVD*[tw]OR multi-media[tw] OR multime-dia[tw]OR Decision Aid*[tw] OR Internet[MeSH] OR website*[tw]OR web site*[tw] OR videotape recording[MeSH] OR videodisc recording[MeSH] OR video-audio media[publication type]) AND (terminal[tw] OR chronic[tw] OR advanced[tw] OR severity[tw] OR severe[tw] OR failure*[tw] OR end stage[tw] OR endstage[tw] OR dying[tw] OR Intensive Care Units[MeSH] OR intensive care[tw] OR ICU[tw] ORhospice*[tw])AND(Patient[MeSH]OR Patient[tw]OR patients[tw] OR family[MeSH] ORfamily[tw]ORfamiliesORson[tw] OR sons[tw] OR daughter*[tw] OR parent[tw] OR parents[tw] OR spouse[tw] OR spouses[tw] OR husband*[tw] OR wife[tw] OR wives[tw] OR caregiver*[tw]).

Study Selection

This systematic review includes published nonrandomized clinical trials and RCTs that test decision tools intended for use by patients and their caregivers. Studies were included if they tested tools to improve treatment decision making for patients living with serious illness. Decision tools were included whether or not they met the International Patient Decision Aid Standards Collaboration definition for decision aids, that is, tools that present treatment options in a balanced and evidence-based manner.8 Tools were included if they were structured for use by the patient or family caregiver without immediate clinician support. For instance, we excluded interventions that required communication training for clinicians or extensive patient coaching. Formats included print, video, or web-based decision tools. Content had to be relevant for communication about major treatment decisions in serious illness. Included studies could be from any health care setting or country if they were written in English and amenable to quality analysis. Given the early stage of this field of research, we accepted randomized or nonrandomized controls and diverse outcomes and lengths of follow-up.

We defined an eligible patient population as adults living with advanced-stage or potentially life-limiting diseases, including critical illness, metastatic cancer, advanced stages of renal or liver disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cystic fibrosis, systolic congestive heart failure, human immunodeficiency virus infection and/or AIDS, or advanced neurodegenerative diseases, such as Parkinson disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or dementia. Studies were excluded if they addressed prevention or stable chronic disease at an early stage. Because communication and decision making differ greatly for children, we included only interventions for patients 18 years or older.

Two of us (D.M. and L.C.H.) reviewed all titles and abstracts and excluded abstracts that did not address patients with serious illness. Two of us (C.A.A. and L.C.H.) independently reviewed all the remaining abstracts and excluded observational studies, studies of patients with insufficient illness severity, or studies of nonexportable interventions. At least 2 of us then examined each full article of the remaining published studies to determine final inclusion and exclusion. Any disagreements were resolved by consensus discussion. Additional studies were accepted after hand searching reference lists of the included studies and asking content experts for additional suggestions.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We created a standardized data extraction instrument to prepare evidence tables. This instrument followed the CONSORT criteria9,10 and the Transparent Reporting of Evaluations With Nonrandomized Designs (TREND) criteria.11 Data extraction included study design and the type of control or comparison group; target population and severity of illness; primary and secondary outcome measures; reported results; and intervention type categorized as ACP for a future decision or support for a current clinical decision.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Two of us (C.A.A. and L.C.H.) analyzed the studies’ risk for bias based on the presence or absence of the following 8 elements: randomization with or without allocation concealed, blinding of outcome assessment, blinding of participants, specification of outcomes, specification of inclusion criteria, greater than 75% completion of outcome data, adjustment for confounding, and intention-to-treat analysis. Analysis followed the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) criteria used in Cochrane systematic reviews.12,13 Studies meeting 5 or more of these criteria were assessed as high quality (GRADE A) with a low risk for bias; those meeting 3 to 4 criteria, as intermediate quality (GRADE B) with a medium risk for bias; and those meeting 0 to 2 criteria, as lower quality (GRADE C) with a high risk for bias. To reduce bias in reporting, one of us (C.A.A.) led the review of studies authored by investigators conducting this systematic review. We used the PRISMA checklist to design and report the study.14

To summarize the potential clinical impact of each decision tool, we developed categories to describe the degree of change in patient-centered outcomes. Interventions that lead to improvement in patient outcomes of symptom distress, satisfaction, or quality of life or changes in treatment experiences were termed high impact. Tools with evidence of patient or caregiver behavioral changes or actual treatment choices were termed moderate impact. Tools with no effect on outcomes or those addressing intermediate outcomes, such as change in knowledge or attitudes, were termed lesser impact. To describe the accessibility of each tool, we searched the published studies and the Internet for information on how to view and use the tool and whether it was free or had to be purchased.

Results

Of the initial 9995 titles identified by the search strategy, 389 met our criteria for full abstract review, and 110 met our criteria for full text review. Seventy-five studies were excluded, and 3 additional titles were included from hand searching reference lists. In total, 38 articles met all inclusion criteria (Figure).

Figure.

Literature Search and Selection

Seventeen of the included studies were RCTs, and the remaining 21 studies were trials with a small pilot or preintervention-postintervention study design. Six of the RCTs tested tools for ACP for future decisions, and 11 tested tools to support immediate treatment choices.

Small Pilot and Preintervention-Postintervention Studies

The 21 pilot studies7,15–34 were designed to examine feasibility and to provide preliminary evidence for newly developed decision tools (Table 1). Seven pilot trials tested ACP tools for future decisions,15,23–27,34 and 14 tested tools to support patient engagement in current decisions.7,16–22,28–33 Seven of the pilot trials15–19,21,22 have been followed by published RCTs,35–42 and a search of trial registries revealed that 2 additional studies7,20 are being tested in clinical trials.

Table 1.

Small Pilot and Preintervention-Postintervention Studies

| Source | Intervention and Study Population Description | Follow-up RCT |

|---|---|---|

| Decision Making Tools for ACP | ||

| Braun et al,23 2006 | Booklets on 5 end-of-life topics to be targeted to the elderly | NA |

| Hickman et al,34 2014 | Video and web-based interactive education regarding completion of advance directive |

NA |

| Hossler et al,24 2010 | Interactive, computer- based tool on ACP for patients with ALS |

NA |

| Enguidanos et al,25 2011 | Brochure on African Americans and hospice care for outpatients with chronic illnesses |

NA |

| Schiff et al,26 2009 | Booklet on ACP for elderly hospitalized patients | NA |

| Schubart et al,27 2012 | Computer-based tool about ACP for elderly outpatients | NA |

| Volandes et al,15 2008 | Two-minute video showing features of advanced dementia and goals of care for elderly Latino outpatients |

Volandes et al,35 2009; Volandes et al,36 2009; and Volandes et al,37 2011 |

| Decision Making Tools to Support Current Choices | ||

| Brundage et al,28 2000 | Booklet with descriptions of treatment options for advanced NSCLC and adverse effects |

NA |

| Cox et al,7 2012 | Ten-page booklet describing chronic critical illness to aid families of patients in the ICU |

Study in progress and recruiting, https://clinicaltrials.gov |

| Dales et al,29 1999 | Booklet with accompanying audio portion about MV in severe COPD |

NA |

| Deep et al,16 2010 | Two-minute video showing features of advanced dementia and goals of care for families of patients with advanced dementia |

Volandes et al,35 2009; Volandes et al,36 2009; and Volandes et al,37 2011 |

| Leighl et al,17 2008 | Twenty-five–page booklet on lung cancer treatment and outcomes for patients with advanced NSCLC |

Leighl et al,38 2011 |

| Matlock et al,30 2014 | Booklet on palliative care, including importance of ACP and clarifying goals and wishes for inpatients undergoing evaluation by a palliative care team |

NA |

| McCannon et al,18 2012 | Three-minute video on CPR and mechanical ventilation for families of critically ill patients |

Epstein et al,39 2013 |

| Mitchell et al,19 2001 | Audiobooklet addressing feeding options for families of patients with advanced dementia |

Hanson et al,40 2011 |

| Sepucha et al,31 2009 | Thirty-minute video with booklet that addresses living with metastatic breast cancer |

NA |

| Smith et al,32 2011 | Printed booklet with review of diagnoses, prognosis, treatment options, and adverse effects for advanced malignant disease |

NA |

| Sudore et al,20 2014 | Easy-to-read, culturally appropriate, interactive, website that includes a 5-step ACP process and the use of how-to videos that model ACP behavior. The program is focused on teaching elderly patients how to identify what is most important in life, how to communicate that with others, and how make informed medical decisions. |

Study in progress and recruiting, https://clinicaltrials.gov |

| Snyder et al,21 2013 | Printed booklet written at sixth-grade level on advanced dementia and feeding options for families of these patients |

Hanson et al,40 2011 |

| Volandes et al,22 2012 | Six-minute video depicting the following 3 possible levels of care: full, limited, or comfort focus for patients with advanced cancer |

El-Jawahri et al,41 2010; Volandes et al,42 2012 |

| Wilson et al,33 2005 | Booklet with audio portion describing COPD and MV for Canadian outpatients with severe COPD |

NA |

Abbreviations: ACP, advance care planning; ALS, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; ICU, intensive care unit; MV, manual ventilation; NA, not applicable; NSCLC, non–small cell lung cancer; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

RCTs of Decision Tools for ACP

Six RCTs35–37,43–45 tested 4 different ACP tools, including a short video, a low-health-literacy print tool, a workbook, and a website. Within this group, nearly all studies were of high quality and targeted out- patient populations (Table 2). All but 1 tool improved patient knowledge,35–37,43,44 and 2 tools had an effect on clinical decisions.43,44

Table 2.

RCTs of Decision Tools for ACP

| Source | Study Population | Intervention and Control | Evidence of Effect on Patient-Centered Outcomes |

Rating and Accessibility of the Toola |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pearlman et al,44 2005 | 280 Outpatients aged ≥55 y with chronic illness Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: 52-page workbook Your Life, Your Choices on ACP and 30-min visit with social worker Control: packet of advance directive forms |

Moderate impact Increased patient report of ACP discussions after index visit (64% vs 28%; P < .001); increased ACP-related notes written by the clinicians (48% vs 23% of the medical records, respectively; P = .001) |

GRADE B Free online (http://www.rihlp.org) |

| Sudore et al,43 2007 |

205 Outpatients aged ≥50 y in an urban medical clinic Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: 12-page advance directive document modified for low health literacy, available in English or Spanish Control: Standard California advance directive |

Moderate impact Improved ease of use and understanding (69.1% vs 48.7%; P < .001) Increased completion of advance directives in 6 mo (18.5% vs 7.7%; P = .03) |

GRADE A Free online (http://www.iha4health.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/CAHCD_English_no_Script_3.14.13.pdf) |

| Vogel et al,45 2013 |

35 Outpatients with stages III and IV ovarian cancer Severity of illness: moderate to severe |

Intervention: website information on ovarian cancer, shared decision making, advance directive completion, and palliative care consultation Control: usual care, clinical documents available on a website |

Lesser impact No effect on completion of advance directives (P = .220) No effect on palliative care consultation (P = .440) |

GRADE C Not accessible |

| Vola ndes et al,35 2009 | 200 Outpatients aged ≥65 y Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: verbal description followed by a 2-min video showing features of advanced dementia Control: verbal description of advanced dementia |

Lesser impact Increased choice of comfort care as primary goal (86% vs 64%; P = .003) |

GRADE: A Clinicians may purchase online (http://www.acpdecisions.org/) |

| Volandes et al,36 2009 | 14 Outpatients aged ≥65 y Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: verbal description followed by a 2-min video showing features of advanced dementia Control: verbal description of advanced dementia |

Lesser impact Increased concordance between patients and surrogates (100% vs 33%; P = .015) |

GRADE A Clinicians may purchase online (http://www.acpdecisions.org/) |

| Volandes et al,37 2011 | 76 Rural outpatients aged ≥ 65 y Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: verbal description followed by a 2-min video showing features of advanced dementia Control: verbal description of advanced dementia |

Lesser impact Increased choice of comfort care as primary goal (91% vs 72%; P < .001) Decreased choice of life-prolonging care as primary goal (0 vs 16%; P = .047). |

GRADE A Clinicians may purchase online (http://www.acpdecisions.org/) |

Abbreviations: ACP, advance care planning; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

GRADE ratings are explained in the Data Synthesis and Analysis subsection of the Methods section.

Three high-quality (GRADE A) clinical trials tested a 2-minute video developed by Volandes et al35–37 on features of advanced dementia to inform ACP discussions, should individuals develop this health condition. Each study tested the video in different outpatient populations. The largest of these 3 trials35 enrolled 200 outpatients 65 years and older and found that viewing the video resulted in a significant increase in patients reporting that they would choose comfort as their primary goal for a future health state of advanced dementia (86% vs 64%; P = .003). Another study37 examined 76 rural outpatients and demonstrated an increased choice of comfort as their primary goal for advanced dementia (91% vs 72%; P < .001). A third study of 14 outpatients older than 6 years36 demonstrated increased concordance between patients and their surrogates after viewing the video (100% vs 33%; P = .02). These trials examined immediate preference change, but they did not examine outcomes such as documentation of preferences or discussion of preferences with health care practitioners.

The remaining 3 ACP studies43–45 tested the effect of 3 different tools on the expression and documentation of treatment preferences. One high-quality (GRADE A) RCT by Sudore et al43 examined an advance directive that was modified for patients with lower health literacy and found it improved ease of use when compared with a standard advance directive document (69.1% vs 48.7%; P < .001). Six months later, those patients who used the literacy-adjusted advance directive were more likely to have completed a written directive (18.5% vs 7.7%; P = .03). The RCT by Pearlman et al44 was of intermediate quality (GRADE B). The authors examined an ACP workbook and found a significant increase in the discussion of ACP with health care practitioners (64% vs 28%; P < .001) and in documentation of living wills (48% vs 23%; P < .001). Finally, a poor-quality small RCT45 tested a website to promote ACP and palliative care consultation for women with ovarian cancer. This small study found no effect of the website tool on advance directive completion or palliative care consultation.

RCTs of Decision Tools for Current Treatment

Eleven RCTs38–42,46–51 tested decision tools to support current treatment choices in serious illness. All but 1 study49 improved knowledge (Table 3). Three tools40,46,47 also provided evidence of improved clinical communication or choice of treatments.

Table 3.

RCTs of Decision Tools for Current Treatment

| Source | Study Population | Intervention and Control | Evidence of Effect on Patient-Centered Outcomes | Rating and Accessibility of the Toola |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clayton et aI,46 2007 | 174 Australian outpatients with advanced cancer Severity of illness: moderate to severe |

Intervention: 16-page booklet “Asking Questions Can Help: An Aid for People Seeing the Palliative Care Team” with 112 questions on end-of-life care that can be discussed with a physician Control: usual care |

Moderate impact Patients in intervention group asked 2.31 times more questions (95% CI, 1.68–3.18; P < .001) of clinicians, discussed more items (17.6 vs 12.7; P = .002), and spent more time per visit (37.8 vs 30.5 min) No change in anxiety or information need at 3 wk |

GRADE A Free online (http://www.psych.usyd.edu.au/cemped/docs/comms_Bookletl.pdf) |

| El-Jawahri et al,41 2010 | 50 Outpatients with malignant glioma Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: narrative about choice of 3 levels of medical care followed by a 6-min video depicting elements of life-prolonging, limited care and comfort focus Control: narrative descriptions only |

Lesser impact Increased choice for comfort care (91% vs 22%; P < .0001) |

GRADE A Clinicians may purchase online (http://www.acpdecisions.org/) |

| Epstein et al,39 2013 | 56 Ambulatory outpatients with progressive pancreatic or hepatobiliary cancer Severity of illness: severe |

Intervention: 3-min video on CPR and MV Control: narrative description of CPR and MV |

Lesser impact No change in CPR or ventilator preferences Trend in ACP documentation at 1 mo (40% vs 15%; P = .07) No change in CPR or MV knowledge |

GRADEB Clinicians may purchase online (http://www.acpdecisions.org/) |

| Hanson et al,40 2011 | 256 Patients in nursing homes aged ≥65 y with advanced dementia Severity of illness: severe |

Intervention: audio or printed information on dementia and feeding options Control: usual care |

Moderate impact Decreased decisional conflict at 3 mo (DCS score, 1.65 vs 1.97; P < .001) Increased frequency of communication with health care practitioners at 3 mo (46%vs 33%; P= .04) Increase in use of dysphagia diet at 3 mo (89% vs 76%; P = .04) |

GRADE A Free online (http://www.med.unc.edu/pcare/resources/feedingoptions) |

| Leighl et al,38 2011 | 207 Outpatients with metastatic colorectal cancer in Canada and Australia Severity of illness: moderate to severe |

Intervention: booklet with video that reviews goals of palliative treatment with and without chemotherapy Control: usual care |

Lesser impact No change in choice to undergo chemotherapy at 1 to 2 wk No change in decisional conflict or satisfaction Greater increase in knowledge (16% vs 5% increase; P < .001) |

GRADE A Not available |

| Meropol et al,48 2013 | 743 Outpatients with known metastatic solid tumors Severity of illness: moderate to severe |

Intervention: communication skills training in a 15-min online module that addressed how to prepare for an initial oncology visit and what questions to ask Control: link to the National Cancer Institute website |

Lesser impact Increase in overall satisfaction with communication at 3 mo Increase in ease of decision making (P < .01) and with actual decision (P< .001) No change in decisional conflict |

GRADEB Not available |

| Peele et al,47 2005 | 432 Outpatients with breast cancer s/p surgery and eligible for adjuvant therapy Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: online tool estimating prognosis with and without adjuvant therapy Control: general informational pamphlet |

Moderate impact Decreased choice of adjuvant therapy (P < .05) |

GRADEB Not available |

| Stirling et al,49 2012 | 31 Community-dwelling caregivers of patients with dementia in Australia Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: workbook with information about community services for the elderly, respite care, and trajectory of decline in dementia Control: usual care |

No impact No change in decisional conflict, knowledge, or treatment preferences |

GRADEB Not available |

| Vandemheen et al,50 2009 | 151 Outpatients in Canada and United States with CF with FEV1 < 40% predicted Severity of illness: severe |

Intervention: print and online aid on CF and lung transplant Control: usual care |

Lesser impact Improved knowledge (P < .001) and realistic expectations (P < .001) Reduced decisional conflict (DCS score, 11.6 vs 20.4; P = .0007) No change in transplant choice at 12 mo |

GRADE A Free online (http://decisionaid.ohri.ca/docs/das/CF_Australia.pdf) |

| Volandes et al,42 2012 | 101 Patients aged ≥ 65 years newly admitted to skilled nursing facilities in Boston area Severity of illness: moderate |

Intervention: narrative about 3 levels of medical care (life prolonging, limited care, and comfort focus) followed by a 6-min video depicting these Control: narrative descriptions only |

Lesser impact Increased choice for comfort care (80% vs 57% stated they would choose comfort measures; P = .02) |

GRADE A Clinicians may purchase online (http://www.acpdecisions.org/) |

| Yun et al,51 2011 | 444 Caregivers of terminally ill patients with cancer in Korea Severity of illness: severe |

Intervention: video “Patients Want to Know the Truth” with booklet discussing disclosure of terminal status to patients and intrafamily communication Control: National Cancer Institute video and booklet on cancer pain management |

Lesser impact No change in decision to discuss terminal prognosis Decrease in decisional conflict initially (P = .008) and at 6 mo (P = .031) Decreased caregiver depression initially (P = .007) and at 6 mo (P = .008) |

GRADE A Not available |

Abbreviations: ACP, advance care planning; CF, cystic fibrosis; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DCS, Decisional Conflict Scale; FEV,, forced expiratory volume in the first second of expiration; GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; MV, manual ventilation; RCT, randomized clinical trial; s/p, status post.

GRADE ratings are explained in the Data Synthesis and Analysis subsection of the Methods section.

Seven of these studies38,39,41,46–48,51 involved populations with advanced cancer. One high-quality (GRADEA) study of outpatients with advanced cancer by Clayton et al46 found that a booklet prompting communication about prognosis and palliative care led to significantly more patient questions asked during an initial palliative care visit (2.31 times more questions; P < .001). Another large high-quality (GRADE A) study by Leighl et al38 examined the impact of a 15-minute online module intended to help patients with metastatic cancer prepare for an initial oncology visit. Although no change in decisional conflict or choice of palliative chemotherapy was observed, the authors noted an increase in satisfaction with (P = .03) and ease of decision making (P < .01).

In a large high-quality (GRADE A) study by Yun et al,51 a booklet assisting family members with the decision about disclosure of terminal status to Korean patients with cancer offered no change in the decision to discuss a terminal prognosis, but a significant decrease in decisional conflict (P = .008) and caregiver depression (P = .007) occurred. Further, both benefits were sustained at 6 months (P = .03 and P = .008, respectively).51

An intermediate-quality (GRADE B) study by Peele et al47 showed that an online decision tool decreased the choice for adjuvant chemotherapy with limited medical benefits in patients with breast cancer (P < .05). In a large study of intermediate quality (GRADE B), Meropol et al48 tested an online training module to prepare patients with advanced cancer for their first oncology visit. This intervention improved patients’ satisfaction with and ease in decision making.

Two studies39,41 examined 2 different video decision making tools for cancer patients. One intermediate-quality (GRADE B) study39 of a 3-minute video on cardiopulmonary resuscitation and mechanical ventilation assessed subsequent decisions by inpatients with late-stage gastrointestinal tract cancer, and they found no change in cardiopulmonary resuscitation or ventilation preferences. However, a high-quality (GRADE A) study41 testing a similar 6-minute video on the goals of care resulted in a large increase of choice of comfort measures (91% vs 22%; P < .001) in a population with malignant glioma. This 6-minute video was also shown to individuals who were newly admitted to nursing homes in another high-quality RCT,42 and more patients in the intervention group preferred comfort-oriented care (80% vs 57%; P = .02).

Two of the remaining studies40,49 addressed patients with advanced dementia. A high-quality (GRADE A) study by Hanson et al40 found that a decision making tool on feeding options in patients with advanced dementia in nursing homes led to significant decreases in decisional conflict (Decisional Conflict Scale52 score, 1.65 vs 1.97; P < .001) and increased the use of a dysphagia diet (89% vs 76%; P = .04). An intermediate-quality (GRADE B) Australian study by Stirling et al49 of a decision tool on supportive resources for dementia care did not find any change in decisional conflict or treatment preferences.

Finally, Vandemheen et al50 led a high-quality (GRADE A) study of a decision tool for patients with cystic fibrosis who were considering lung transplant and found that the tool increased knowledge and realistic expectations while decreasing decisional conflict (P < .001). However, the tool did not change the choice to undergo transplant at 12 months.50

Discussion

Key Findings

This study is, to our knowledge, the first systematic review of clinical tools to improve communication and decision making for patients facing serious illness. Seventeen RCTs, nearly all of moderate or high quality, form the primary body of evidence for these tools. Study results show that decision tools clearly improve patient knowledge and preparation for treatment choices, including ACP, palliative care and goals of care communication, feeding options in dementia, lung transplant in cystic fibrosis, and truth telling in terminal cancer.

Methodological Considerations

Although many trials do not measure outcomes beyond knowledge, 5 published decision tools40,43,44,46,47 provide evidence of an effect on clinical outcomes, changes in advance directive documentation, clinical decision making, and treatments received. Three of these tools have been tested in a high-quality RCT, including a tool to promote ACP for persons with low literacy,43 a booklet to prepare patients with advanced cancer to talk with a palliative care team,46 and a decision aid for feeding options in dementia.40 All 3 tools are currently available for free on the Internet.

The strongest evidence to promote ACP and to prepare patients for future choices supports 2 tools. The first tool is a video ACP tool available to clinicians from the developer that can assist discussions of treatment preferences for the future health state of patients with advanced dementia.35,37 The second tool is an advance directive documentation guide available for free on the Internet that is designed for patients with low health literacy.43

Several tools to support immediate clinical choices are available and evidence based. Most of these tools improve knowledge, and some are proven to change actual treatment decisions.38,39,41,46–48,51 Only 2 tools are standardized decision aids—one addressing feeding options in dementia care40 and one addressing advanced treatment choices in cystic fibrosis.50 Decision aids differ in important ways from other decision tools and meet formal standards for framing the presentation of medical information to patients in line with principles of shared decision making.6

This study makes a novel contribution to the existing literature by systematically reviewing exportable decision tools designed to empower patients and caregivers in decision making. However, these data have important limitations. Many study populations were small, leaving studies inadequately powered for meaningful results. Study populations all have serious illness, but diagnoses are heterogeneous and limit conclusions about application to specific diseases. More than half of the identified studies used convenience samples and followed a pre-intervention-postintervention study design. The nature of interventions designed to improve these outcomes often results in a non-blinded study design. We only searched for articles published since 1995, so we might have missed earlier articles. However, our review did not reveal any articles before 1998; therefore, this possibility seems less likely. Finally, this review is limited to published research. The analysis might have had a publication bias toward positive studies that could skew our review. However, some of the studies reviewed reported negative findings, so this possibility seems less likely.

Implications

Given the clear need to improve shared decision making in serious illness, improving this body of evidence should be a research priority. Research is needed to test decision aids for major serious illnesses, such as advanced heart failure or end-stage renal disease. Because the effect on knowledge is well established, future research needs to focus on outcomes measuring the effect of the change in knowledge on treatment decisions, receipt of care consistent with preferences, and satisfaction with care. Furthermore, decision aids for the seriously ill could reduce health care intensity and costs by decreasing unwanted major high-cost interventions or hospitalizations; these outcomes have not been studied.

Tools to promote patient engagement in treatment decisions are a policy priority in the United States since the passage of the Affordable Care Act.53 Therefore, investigators with proven tools may consider the importance of implementation research and effective dissemination strategies to ensure that clinicians and patients can truly benefit. Making proven decision tools available online or embedding them in electronic health record systems would be appropriate first steps. However, meaningful adoption of this novel practice may require peer leadership, incentives, new time and space in clinical settings, training, and feedback.

This body of evidence is promising, yet it lags far behind the rapid dissemination of tools—primarily for ACP—that are developed outside a clinical research framework. A recent review by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality54 combed scientific and gray literature sources to describe a multitude of published ACP tools that are diverse in quality and rarely supported by evidence of effectiveness or patient benefit. Unlike our study, that review excluded decision aids for current health care choices, which may be most relevant once serious illness develops. Healthcare organizations may be more successful at improving shared decision making if they demand decision tools with evidence of effectiveness. This phenomenon suggests a significant opportunity for collaboration in implementation, blending the best of decision science with the broad public reach of innovations in web-based technology.

Conclusions

A small but promising body of research demonstrates the clinical potential to improve patient engagement with tools to enhance decision making in serious illness. A small number of these tools are supported by evidence of their impact and are available for clinical practice. Future research should expand the work to new decisions in serious illness and emphasize outcomes beyond knowledge, such as care consistent with preferences and satisfaction with care.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by grant R01AG037483 from the National Institute on Aging (principal investigator, Dr Hanson).

Role of the Funder/Sponsor: The funding source had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Drs Austin and Hanson had full access to all the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Mohottige, Sudore, Smith, Hanson.

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Austin, Mohottige, Smith, Hanson.

Drafting of the manuscript: Austin, Mohottige, Sudore, Hanson.

Critical revision of the manuscript for important

intellectual content: Austin, Sudore, Smith, Hanson.

Obtained funding: Hanson.

Administrative, technical, or material support: Sudore, Hanson.

Study supervision: Hanson.

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr Hanson has received funding from the National Institute of Nursing Research, the National Institute on Aging, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, and the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute; serves as Vice Chair for Research for the American Geriatrics Society; and provides consulting for Research Triangle Institute on hospice and palliative care quality measurement science. Dr Sudore has received support from the US Department of Veterans Affairs, grant R01AG045043-01 from the National Institute on Aging, and the Patient Centered Outcomes Research Institute. Dr Smith has received support from the American Federation for Aging Research and grant K23 AG040772 from the National Institute on Aging. None of the listed disclosures provide direct funding relevant to this study. No other disclosures were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Rao JK, Anderson LA, Inui TS, Frankel RM. Communication interventions make a difference in conversations between physicians and patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Med Care. 2007;45(4):340–349. doi: 10.1097/01.mlr.0000254516.04961.d5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA. Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. JAMA. 2000;284(19):2476–2482. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scheunemann LP, McDevitt M, Carson SS, Hanson LC. Randomized, controlled trials of interventions to improve communication in intensive care: a systematic review. Chest. 2011;139(3):543–554. doi: 10.1378/chest.10-0595. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.ellowes D, Wilkinson S, Moore P. Communication skills training for health care professionals working with cancer patients, their families and/or carers. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004(2):CD003751. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003751.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barnes S, Gardiner C, Gott M, et al. Enhancing patient-professional communication about end-of-life issues in life-limiting conditions: a critical review of the literature. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2012;44(6):866–879. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elwyn G, O’Connor A, Stacey D, et al. International Patient Decision Aids Standards (IPDAS) Collaboration Developing a quality criteria framework for patient decision aids: online international Delphi consensus process. BMJ. 2006;333(7565):417. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38926.629329.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cox CE, Lewis CL, Hanson LC, et al. Development and pilot testing of a decision aid for surrogates of patients with prolonged mechanical ventilation. Crit Care Med. 2012;40(8):2327–2334. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3182536a63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.O’Connor AM, Bennett CL, Stacey D, et al. Decision aids for people facing health treatment or screening decisions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(3):CD001431. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001431.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boutron I, Moher D, Altman DG, Schulz KF, Ravaud P, CONSORT Group Extending the CONSORT statement to randomized trials of nonpharmacologic treatment: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2008;148(4):295–309. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-148-4-200802190-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Campbell MK, Elbourne DR, Altman DG, CONSORT Group CONSORT statement: extension to cluster randomised trials. BMJ. 2004;328(7441):702–708. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7441.702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Des Jarlais DC, Lyles C, Crepaz N, TREND Group Improving the reporting quality of nonrandomized evaluations of behavioral and public health interventions: the TREND statement. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(3):361–366. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.3.361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Kunz R, Vist GE, Falck-Ytter Y, Schünemann HJ, GRADE Working Group What is “quality of evidence” and why is it important to clinicians? BMJ. 2008;336(7651):995–998. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39490.551019.BE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Higgins JP, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, et al. Cochrane Bias Methods Group; Cochrane Statistical Methods Group. The Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2011;343:d5928. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volandes AE, Ariza M, Abbo ED, Paasche-Orlow M. Overcoming educational barriers for advance care planning in Latinos with video images. J Palliat Med. 2008;11(5):700–706. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deep KS, Hunter A, Murphy K, Volandes A. “It helps me see with my heart”: how video informs patients’ rationale for decisions about future care in advanced dementia. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(2):229–234. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2010.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leighl NB, Shepherd FA, Zawisza D, et al. Enhancing treatment decision-making: pilot study of a treatment decision aid in stage IV non-small cell lung cancer. Br J Cancer. 2008;98(11):1769–1773. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6604395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McCannon JB, O’Donnell WJ, Thompson BT, et al. Augmenting communication and decision making in the intensive care unit with a cardiopulmonary resuscitation video decision support tool: a temporal intervention study. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(12):1382–1387. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mitchell SL, Tetroe J, O’Connor AM. A decision aid for long-term tube feeding in cognitively impaired older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49(3):313–316. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2001.4930313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sudore RL, Knight SJ, McMahan RD, et al. A novel website to prepare diverse older adults for decision making and advance care planning: a pilot study. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(4):674–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Snyder EA, Caprio AJ, Wessell K, Lin FC, Hanson LC. Impact of a decision aid on surrogate decision-makers’ perceptions of feeding options for patients with dementia. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2013;14(2):114–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Volandes AE, Levin TT, Slovin S, et al. Augmenting advance care planning in poor prognosis cancer with a video decision aid: a preintervention-postintervention study. Cancer. 2012;118(17):4331–4338. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Braun KL, Karel H, Zir A. Family response to end-of-life education: differences by ethnicity and stage of caregiving. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2006;23(4):269–276. doi: 10.1177/1049909106290243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hossler C, Levi BH, Simmons Z, Green MJ. Advance care planning for patients with ALS: feasibility of an interactive computer program. Amyotroph Lateral Scler. 2011;12(3):172–177. doi: 10.3109/17482968.2010.509865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Enguidanos S, Kogan AC, Lorenz K, Taylor G. Use of role model stories to overcome barriers to hospice among African Americans. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(2):161–168. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schiff R, Shaw R, Raja N, Rajkumar C, Bulpitt CJ. Advance end-of-life healthcare planning in an acute NHS hospital setting: development and evaluation of the Expression of Healthcare Preferences (EHP) document. Age Ageing. 2009;38(1):81–85. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afn235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schubart JR, Levi BH, Camacho F, Whitehead M, Farace E, Green MJ. Reliability of an interactive computer program for advance care planning. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(6):637–642. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brundage MD, Feldman-Stewart D, Dixon P, et al. A treatment trade-off based decision aid for patients with locally advanced non-small cell lung cancer. Health Expect. 2000;3(1):55–68. doi: 10.1046/j.1369-6513.2000.00083.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dales RE, O’Connor A, Hebert P, Sullivan K, McKim D, Llewellyn-Thomas H. Intubation and mechanical ventilation for COPD: development of an instrument to elicit patient preferences. Chest. 1999;116(3):792–800. doi: 10.1378/chest.116.3.792. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matlock DD, Keech TA, McKenzie MB, Bronsert MR, Nowels CT, Kutner JS. Feasibility and acceptability of a decision aid designed for people facing advanced or terminal illness: a pilot randomized trial. Health Expect. 2014;17(1):49–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2011.00732.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sepucha KR, Ozanne EM, Partridge AH, Moy B. Is there a role for decision aids in advanced breast cancer? Med Decis Making. 2009;29(4):475–482. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09333124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Smith TJ, Dow LA, Virago EA, Khatcheressian J, Matsuyama R, Lyckholm LJ. A pilot trial of decision aids to give truthful prognostic and treatment information to chemotherapy patients with advanced cancer. J Support Oncol. 2011;9(2):79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.suponc.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson KG, Aaron SD, Vandemheen KL, et al. Evaluation of a decision aid for making choices about intubation and mechanical ventilation in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;57(1):88–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2004.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hickman RL, Jr, Lipson AR, Pinto MD, Pignatiello G. Multimedia decision support intervention: a promising approach to enhance the intention to complete an advance directive among hospitalized adults. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2014;26(4):187–193. doi: 10.1002/2327-6924.12051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Volandes AE, Paasche-Orlow MK, Barry MJ, et al. Video decision support tool for advance care planning in dementia: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;338:b2159. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Volandes AE, Mitchell SL, Gillick MR, Chang Y, Paasche-Orlow MK. Using video images to improve the accuracy of surrogate decision-making: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2009;10(8):575–580. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2009.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Volandes AE, Ferguson LA, Davis AD, et al. Assessing end-of-life preferences for advanced dementia in rural patients using an educational video: a randomized controlled trial. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(2):169–177. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Leighl NB, Shepherd HL, Butow PN, et al. Supporting treatment decision making in advanced cancer: a randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with advanced colorectal cancer considering chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(15):2077–2084. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Epstein AS, Volandes AE, Chen LY, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a cardiopulmonary resuscitation video in advance care planning for progressive pancreas and hepatobiliary cancer patients. J Palliat Med. 2013;16(6):623–631. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2012.0524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hanson LC, Carey TS, Caprio AJ, et al. Improving decision-making for feeding options in advanced dementia: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59(11):2009–2016. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2011.03629.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.El-Jawahri A, Podgurski LM, Eichler AF, et al. Use of video to facilitate end-of-life discussions with patients with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(2):305–310. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.7502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Volandes AE, Brandeis GH, Davis AD, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a goals-of-care video for elderly patients admitted to skilled nursing facilities. J Palliat Med. 2012;15(7):805–811. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2011.0505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sudore RL, Landefeld CS, Barnes DE, et al. An advance directive redesigned to meet the literacy level of most adults: a randomized trial. Patient Educ Couns. 2007;69(1–3):165–195. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2007.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pearlman RA, Starks H, Cain KC, Cole WG. Improvements in advance care planning in the Veterans Affairs System: results of a multifaceted intervention. Arch Intern Med. 2005;165(6):667–674. doi: 10.1001/archinte.165.6.667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Vogel RI, Petzel SV, Cragg J, et al. Development and pilot of an advance care planning website for women with ovarian cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2013;131(2):430–436. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.08.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Clayton JM, Butow PN, Tattersall MH, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a prompt list to help advanced cancer patients and their caregivers to ask questions about prognosis and end-of-life care. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25(6):715–723. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.7827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Peele PB, Siminoff LA, Xu Y, Ravdin PM. Decreased use of adjuvant breast cancer therapy in a randomized controlled trial of a decision aid with individualized risk information. Med Decis Making. 2005;25(3):301–307. doi: 10.1177/0272989X05276851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Meropol NJ, Egleston BL, Buzaglo JS, et al. A Web-based communication aid for patients with cancer: the CONNECT Study. Cancer. 2013;119(7):1437–1445. doi: 10.1002/cncr.27874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stirling C, Leggett S, Lloyd B, et al. Decision aids for respite service choices by carers of people with dementia: development and pilot RCT. BMC Med nform Decis Mak. 2012;12:21. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Vandemheen KL, O’Connor A, Bell SC, et al. Randomized trial of a decision aid for patients with cystic fibrosis considering lung transplantation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180(8):761–768. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200903-0421OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yun YH, Lee MK, Park S, et al. Use of a decision aid to help caregivers discuss terminal disease status with a family member with cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(36):4811–4819. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.3870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15(1):25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.The Affordable Care Act. [Accessed December 30, 2013];Title III, Section 3506. http://www.hhs.gov/healthcare/rights/law/index.html.

- 54.Butler M, Ratner E, McCreedy E, Shippee N, Kane RL. Decision aids for advance care planning: an overview of the state of the science. Ann Intern Med. 2014;161(6):408–418. doi: 10.7326/M14-0644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]