Abstract

Objective:

To examine the association between the level of Internet addiction and suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in South Korean adolescents, focusing on the roles of family structure and household economic status.

Methods:

Data from 221 265 middle and high school students taken from the 2008–2010 Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey were used in this study. To identify factors associated with suicidal ideation/attempts, multiple logistic regression analysis was performed. The level of Internet use was measured using the simplified Korean Internet Addiction Self-assessment Tool.

Results:

Compared with mild users of the Internet, high-risk users and potential-risk users were more likely to report suicidal ideation (nonuser, odds ratio [OR] 1.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] 1.05 to 1.15; potential risk, OR 1.49, 95% CI: 1.36 to 1.63; high risk OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.10) or attempts (nonuser, OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.42; potential risk, OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.38; high risk, OR 1.91, 95% CI 1.71 to 2.14). The nonuser group also had a slightly higher risk of suicidal ideation/attempts compared with mild users. This association appeared to vary by perceived economic status and family structure.

Conclusions:

Our study suggests that it is important to attend to adolescents who are at high risk for Internet addiction, especially when they do not have parents, have stepparents, or perceive their economic status as either very low or very high.

Keywords: suicidal ideation, suicidal attempts, Internet addiction, family structure, economic status, adolescent, South Korea

Abstract

Objectif:

Examiner l’association du taux de dépendance à Internet avec l’idéation suicidaire et les tentatives de suicide chez les adolescents sud-coréens, en mettant l’accent sur les rôles de la structure familiale et du statut économique du ménage.

Méthodes:

Les données de 221 265 élèves de l’école intermédiaire et secondaire, tirées de l’enquête en ligne de 2008–2010 sur le comportement à risque des jeunes coréens (KYRBWS) ont servi à cette étude. Pour identifier les facteurs associés à l’idéation suicidaire et aux tentatives de suicide, une analyse de régression logistique multiple a été effectuée. Le taux d’utilisation d’Internet a été mesuré à l’aide de l’instrument coréen simplifié d’auto-évaluation de la dépendance à Internet (échelle KS).

Résultats:

Comparativement aux utilisateurs modérés d’Internet, les utilisateurs « à risque élevé » et « à risque potentiel » étaient plus susceptibles de déclarer une idéation suicidaire (non-utilisateur, RC = 1,10; IC à 95% 1,05 à 1,15; « à risque potentiel », RC = 1,49; IC à 95% 1,36 à 1,63; « à risque élevé », RC = 1,94; IC à 95% 1,79 à 2,10) ou des tentatives de suicide (non-utilisateur, RC = 1,33; IC à 95% 1,25 à 1,42; « à risque potentiel », RC = 1,20; IC à 95% 1,04 à 1,38; « à risque élevé », RC = 1,91; IC à 95% 1,71 à 2,14). Le groupe des non-utilisateurs avait aussi un risque légèrement plus élevé d’idéation suicidaire et de tentatives de suicide que les utilisateurs modérés. Cette association semblait varier selon la structure familiale et le statut économique perçus.

Conclusions:

Notre étude suggère qu’il est important de s’occuper des adolescents qui sont à risque élevé de dépendance à Internet, surtout quand ils n’ont pas de parents, qu’ils ont des beaux-parents, ou qu’ils perçoivent leur statut économique comme étant très faible ou très élevé.

Clinical Implications

The unique feature of this study is that it differentiates between Internet nonuser and Internet user groups.

The analyses indicated that associations between the level of Internet use and suicidal ideation/attempts were statistically significant influences of economic status and family structure; interestingly, the J-shaped trends were shown.

To clarify the levels at which Internet use relieves stress and at which it does not, precise measurement strategies should be developed, and additional research linking these features to suicidality is needed.

Limitations

The study used cross-sectional data, which precludes inferences regarding causal relationships.

The study subjects may have underreported or overreported personal characteristics in a socially acceptable manner.

Since the survey was taken at school, a selection bias may exist.

Suicide is a worldwide health issue. In South Korea, 38.7 people commit suicide every day on average. South Korea’s suicide rate is the highest among the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.1 The suicide attempt rate in South Korea was 26.0 per 100 000 in 2010, but it rapidly increased to 31.7 per 100 000 in 2011. In 2012, the rate decreased to 28.1 per 100 000 but remained the highest suicide attempt rate worldwide.2,3 Furthermore, since 2010, the primary cause of death among South Korean adolescents has been suicide, making it a major social issue.2,4

Internet use is recognized as an essential part of modern life. Adolescents have embraced the Internet as a tool that provides diverse opportunities for communication, education, and entertainment.5 Internet use has increased dramatically globally, with the number of Internet users worldwide reaching more than 2.9 billion in 2014.6 South Korea is the most highly digitalized country among OECD nations. In 2014, 81.6% of the population used the Internet.7 After a series of crimes and deaths related to Internet addiction, the South Korean government recognized Internet addiction as a social and public health problem. Therefore, the government developed the Korean Internet Addiction Self-assessment Tool (KS scale) and distributed it to schools for use in screening for addicted Internet users.8

Intentionally killing oneself can indicate not only a personal crisis but also deterioration of the social context in which an individual lives.9 In particular, the family unit is one of the most important factors contributing to adolescents’ emotional well-being. Adolescents who live in dysfunctional family structures and those whose families are not emotionally supportive are more likely to be socially maladjusted and to show self-destructive behaviors such as suicide10–15 and depression.14,15 Both economic status and family structure are associated with deviant behaviors in adolescents.16,17 Case and empirical studies of Internet addiction have shown that it has adverse effects on the individual’s psychological well-being,18–20 social engagement,21,22 self-esteem,21,23 family relationships,21,24 and marital relationships.21

Speculation in the media often links suicide ideation/attempts to the Internet. However, few studies have examined the association between Internet addiction and suicidal ideation/attempts, and the few that have addressed this topic have used small sample sizes.25–27 To our knowledge, there are no other previous studies comparing an Internet user group and a nonuser group. Our interest in this study lies in how the suicidal ideation/attempts in Internet addiction group are affected by adolescents’ social context: family structure and household status. Thus, this study used a nationally representative sample to examine the effects of Internet use on adolescent suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, comparing an Internet user group to a nonuser group and focusing on the impact of family structure and perceived household economic status. Specifically, the aim was to identify adolescents at high suicidal risk and to use this information for suicide prevention.

Methods

Source of Data

This study used data from the 2008–2010 Korea Youth Risk Behavior Web-based Survey (KYRBWS). The KYRBWS is a cross-sectional survey that has been conducted annually since 2005 by the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC) to monitor South Korean health-related behavior among adolescents. A stratified multistage cluster-sampling design was used to obtain a nationally representative sample of middle and high school adolescents for the survey. The survey’s target population is 7th- to 12th-grade adolescents in South Korea. It includes a number of questions (131 questions in 2008, 129 in 2009, and 128 in 2010) assessing demographic characteristics and 14 areas of health-risk behaviors, including cigarette smoking, alcohol consumption, obesity, physical activity, eating habits, injury prevention, sexual behaviors, mental health, oral health, allergic disorders, personal hygiene, Internet addiction, drug abuse, and health equity.

A total of 223 532 adolescents (75 238 in 2008, 75 066 in 2009, and 73 238 in 2010) have completed the survey. The overall response rate was 95.1% in 2008, 97.6% in 2009, and 97.7% in 2010. Any respondents who did not give their age (n = 2276) or who had only a mother and did not live with her (n = 1) were excluded from the study. A total of 221 265 eligible participants (74 451 in 2008, 74 192 in 2009, and 72 622 in 2010) were included in the analysis. The KYRBWS was approved by the KCDC Institutional Review Board, and all participants provided written informed consent (2014-06EXP-02-P-A).

Assessment and Measurement of Variables

The outcome variables, suicidal ideation and suicide attempts, were assessed through responses to 2 questions: “In the last 12 months, have you ever seriously considered suicide?” and “In the last 12 months, have you ever attempted suicide?”

The primary variable of interest (i.e., the level of Internet use) was assessed by adolescents’ response to the question, “During the last 30 days, how many hours did you spend per day using the Internet, on average?” and by the simplified KS scale, which was used in the 2008–2010 KYRBWS. The KS scale, developed by the Korean National Information Society Agency in 2008,8,28 consists of 20 questions categorized in 6 domains to assess the level of Internet addiction: disturbance of adaptive functions, positive anticipation, withdrawal, virtual interpersonal relationships, deviant behaviors, and tolerance. Each question was scored on 4-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 4 (always); higher scores indicated higher Internet addiction risk. The total score was calculated by adding the scores for each question. The reliability of the KS scale was established for the elementary school (Cronbach’s alpha score: 0.89) and junior and senior school students (Cronbach’s alpha score: 0.91),8 and the Cronbach’s alpha score in the current study was 0.92. Students who did not use the Internet on weekdays or weekends were placed in the nonuser group. Those who used the Internet were divided into 3 groups based on cutoff points for scores on the KS scale: mild user (47 points or fewer), potential risk for addiction (48-52 points), and high risk for addiction (53 points or more).

Family structure was identified from adolescents’ answers to questions regarding the presence of family members (father, stepfather, mother, and stepmother) in the home. Having both a father and a mother was categorized as both biological parents, and having either a father or a mother was categorized as single parent. Having 1 biological parent and 1 stepparent or having a stepfather or stepmother only was categorized as stepparent. Orphaned students were placed in a separate category.

We adjusted for other covariates representing the study participants’ sociodemographic characteristics (gender, school year, school type, school performance, perceived academic performance, residential type, and survey year) and mental health and related health-risk indicators (depression, awareness of stress, substance/ alcohol/tobacco use, and subjective sleep sufficiency) when analyzing the relationship between Internet addiction level and suicidal ideation and suicidal attempt of study participants. All of the covariates were examined by the response to the each corresponding question.

Statistical Analysis

Descriptive analyses were used to examine the distribution of general characteristics of the study population. Each categorical variable was examined by the frequencies and row percentages and performing χ2 tests to identify significant correlations between variables. Multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to identify associations of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts with Internet addiction in relation to family structure and household economic status. In addition, we formed a combined variable using categories of family structure/household economic status and Internet addiction level, then performed multiple logistic regression analysis. All estimates were calculated based on sample weights, which were evaluated by taking into consideration the sampling rate, response rate, sex, and school type and grade proportion of the reference population. The analysis was adjusted for the complex sample design of the survey. All calculated P values were 2 sided, and P values <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.3 (SAS, Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

General Characteristics of the Study Participants

Data of 221 265 participants were analyzed in this study. Of these, 19% reported suicidal ideation and 4.7% reported a suicide attempt in past 12 months from their survey year. Regarding the level of Internet addiction, significantly higher proportions of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts were found among high-risk, potential-risk, and nonuser students compared with mild users (P < 0.001). In the analysis of suicidal ideation, all examined variables except school year or survey year were significantly associated, whereas in the analysis of suicide attempts, all variables were significantly associated (Table 1).

Table 1.

General characteristics of the sample by suicidal ideation and attempt (omitted version; unit: n [weight %]).

| Suicidal Ideation (n = 221 265) | Suicidal Attempt (n = 221 625) | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Yes | No | P Value | Yes | No | P Value | ||||||

| Level of Internet use | ||||||||||||

| Nonuser | 32 199 | 6661 | (20.6) | 25 538 | (17.9) | <0.0001 | 2047 | (6.3) | 30 152 | (93.7) | <0.0001 | |

| Mild user | 178 289 | 31 683 | (17.8) | 146 606 | (82.2) | 7319 | (4.0) | 170 970 | (96.0) | |||

| Potential risk | 5015 | 1482 | (30.0) | 3533 | (70.0) | 354 | (6.8) | 4661 | (93.2) | |||

| High risk | 5762 | 2260 | (39.6) | 3502 | (60.4) | 743 | (12.8) | 5019 | (87.2) | |||

| Gender | ||||||||||||

| Male | 115 869 | 17 599 | (15.3) | 98 270 | (84.7) | <0.0001 | 4049 | (3.5) | 111 820 | (96.5) | <0.0001 | |

| Female | 105 396 | 24 487 | (23.3) | 80 909 | (76.7) | 6414 | (6.0) | 98 982 | (94.0) | |||

| School year | ||||||||||||

| 7th grade | 37 886 | 7243 | (19.4) | 30 643 | (80.6) | 0.3739 | 2120 | (5.7) | 35 766 | (94.3) | <0.0001 | |

| 8th grade | 38 098 | 7269 | (19.2) | 30 829 | (80.8) | 2013 | (5.2) | 36 085 | (94.8) | |||

| 9th grade | 37 925 | 7309 | (19.1) | 30 615 | (80.9) | 1867 | (4.8) | 36 058 | (95.2) | |||

| 10th grade | 36 843 | 6989 | (18.8) | 29 854 | (81.2) | 1670 | (4.5) | 35 173 | (95.5) | |||

| 11th grade | 36 591 | 6847 | (18.7) | 29 744 | (81.3) | 1527 | (4.0) | 35 064 | (96.0) | |||

| 12th grade | 33 923 | 6429 | (19.1) | 27 494 | (80.9) | 1266 | (3.7) | 32 657 | (96.3) | |||

| Perceived household economic status | ||||||||||||

| High | 61 330 | 10 404 | (17.1) | 50 926 | (82.9) | <0.0001 | 2700 | (4.4) | 58,630 | (95.6) | <0.0001 | |

| Middle | 104 751 | 17 483 | (16.8) | 87 268 | (83.2) | 3931 | (3.7) | 100,820 | (96.3) | |||

| Low | 55 184 | 14 199 | (25.7) | 40 985 | (74.3) | 3832 | (6.9) | 51,352 | (93.1) | |||

| Frequent depression for more than 2 wk | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 83 732 | 33 611 | (40.0) | 50 121 | (60.0) | <0.0001 | 9077 | (10.6) | 74 655 | (89.4) | <0.0001 | |

| No | 137 533 | 8475 | (6.3) | 129 058 | (93.7) | 1386 | (1.0) | 136 147 | (99.0) | |||

| Stress awareness | ||||||||||||

| Yes | 96 667 | 31 375 | (32.4) | 65 292 | (67.6) | <0.0001 | 8161 | (8.3) | 88 506 | (91.7) | <0.0001 | |

| No | 124 598 | 10 711 | (8.7) | 113 887 | (91.3) | 2302 | (1.8) | 122 296 | (98.2) | |||

| Family structure | ||||||||||||

| Both biological parents | 187 539 | 34 282 | (18.3) | 153 257 | (81.7) | <0.0001 | 8000 | (4.2) | 179,539 | (95.8) | <0.0001 | |

| Stepparent | 17 098 | 3861 | (22.9) | 13 237 | (77.1) | 1236 | (7.4) | 15,862 | (92.6) | |||

| Single parent | 12 466 | 2876 | (22.9) | 9590 | (77.1) | 834 | (6.5) | 11,632 | (93.5) | |||

| Orphaned | 4162 | 1067 | (26.5) | 3095 | (73.5) | 393 | (9.9) | 3769 | (90.1) | |||

| Total | 221 265 | 42 086 | (19.0) | 179 179 | (81.0) | 10 463 | (4.7) | 210,802 | (95.3) | |||

Adjusted Odds Ratios for Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts

To examine the associations of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts with other variables, a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed (Table 2). All variables were used simultaneously in the analysis. With respect to suicidal ideation, compared with the reference group, which was mild users, the odds ratios for suicidal ideation were higher for all other levels of Internet use (nonuser, OR 1.10, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.15; potential risk, OR 1.49, 95% CI 1.36 to 1.63; high risk, OR 1.94, 95% CI 1.79 to 2.10). Similar results were shown for suicide attempts, except that the nonuser group (OR 1.33, 95% CI 1.25 to 1.42) was more likely to attempt suicide than was the potential-risk group (OR 1.20, 95% CI 1.04 to 1.38). The distribution of odds ratios for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts by level of Internet use showed a J-shaped relationship. In addition, the odds ratios were higher at younger ages. Adolescents who described their perceived economic status as either high or low showed higher odds ratios for both ideation and attempts than did the group with midlevel economic status. In terms of family structure, adolescents in the stepparent and no-parent groups showed higher odds ratios than did the other two groups.

Table 2.

Factors associated with suicidal ideation and attempt (omitted version; unit: OR [95% CI]).

| Suicidal Ideation | Suicidal Attempt | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of Internet use | ||||

| Nonuser | 1.10 | (1.05 to 1.15) | 1.33 | (1.25 -1.42) |

| Mild user | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Potential risk | 1.49 | (1.36 to 1.63) | 1.20 | (1.04 to 1.38) |

| High risk | 1.94 | (1.79 to 2.10) | 1.91 | (1.71 to 2.14) |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Female | 1.45 | (1.39 to 1.51) | 1.62 | (1.51 to 1.73) |

| School year | ||||

| 7th grade | 1.83 | (1.71 to 1.94) | 2.87 | (2.58 to 3.19) |

| 8th grade | 1.64 | (1.54 to 1.74) | 2.33 | (2.10 to 2.60) |

| 9th grade | 1.49 | (1.40 to 1.58) | 1.91 | (1.72 to 2.12) |

| 10th grade | 1.27 | (1.20 to 1.34) | 1.54 | (1.38 to 1.72) |

| 11th grade | 1.17 | (1.11 to 1.24) | 1.28 | (1.16 to 1.41) |

| 12th grade | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Perceived household economic status | ||||

| High | 1.07 | (1.03 to 1.11) | 1.27 | (1.18 to 1.37) |

| Middle | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Low | 1.31 | (1.26 to 1.36) | 1.35 | (1.26 to 1.44) |

| School performance | ||||

| High | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Middle | 1.03 | (0.98 to 1.09) | 1.07 | (1.00 to 1.16) |

| Low | 1.00 | (0.95 to 1.05) | 1.24 | (1.16 to 1.33) |

| Frequent depression for more than 2 wk | ||||

| No | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Yes | 6.85 | (6.62 to 7.09) | 7.10 | (6.56 to 7.69) |

| Stress awareness | ||||

| No | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Yes | 2.84 | (2.74 to 2.94) | 2.42 | (2.26 to 2.59) |

| Family structure | ||||

| Both biological parents | 1.00 | — | 1.00 | — |

| Stepparent | 1.14 | (1.08 to 1.21) | 1.36 | (1.23 to 1.5) |

| Single parent | 1.04 | (0.98 to 1.11) | 1.12 | (1.01 to 1.24) |

| Orphaned | 1.23 | (1.10 to 1.38) | 1.36 | (1.14 to 1.62) |

All variables in the table were simultaneously adjusted in the logistic regression model.

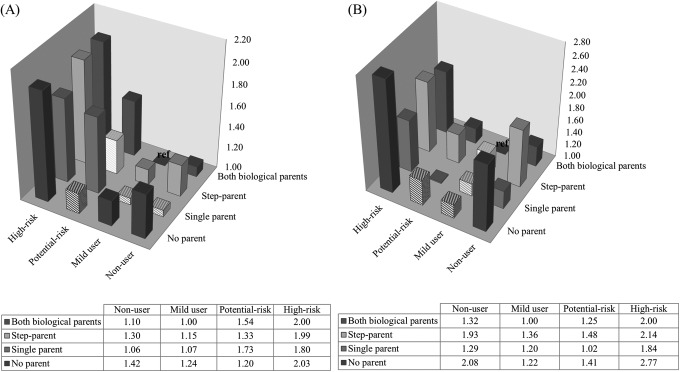

Association of Internet Use with Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts by Family Structure

Based on the results of previous studies of the relationship of family structure with suicidal ideation/attempts10–17 and with Internet addiction,21,22,24 it seemed that family structure acts as an effect modifier in the association between Internet addiction and suicidal ideation/attempts. As we mentioned in the Methods section, combined variables was formed and a multiple logistic regression analysis was performed. This analysis showed that most of the odds ratios were higher in the no-parent group. In addition, the nonuser, stepparent, and no-parent groups also had high odds ratios. Furthermore, adolescents categorized as showing high-risk Internet use had the highest odds ratios of all groups in all family structure groups. The high-risk, no-parent group had the highest odds ratios for suicidal ideation and suicide attempts of any group (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Adjusted odds ratios for suicidal ideation and attempts by level of Internet use in family structure. (A) Adjusted odds ratio for suicidal ideation. (B) Adjusted odds ratio for suicide attempts. *Solid bars represent odds ratios with P < 0.05; striped bars represent odds ratios that are not statistically significant. **Adolescents who are Internet mild users with both biological parents are the reference group.

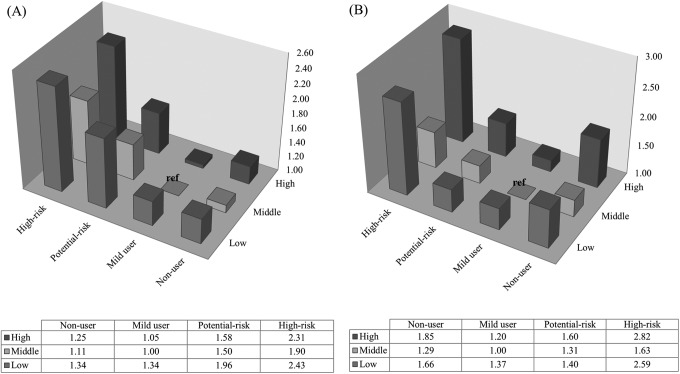

Association of Internet Use with Suicidal Ideation and Suicide Attempts by Perceived Household Economic Status

As with family structure, an additional multiple logistic regression analysis was performed to examine the relationship between the combined variable of Internet addiction level and household economic status and suicidal ideation/attempt. With regard to suicidal ideation, most variables showed a J-shaped relationship such that the group who reported mid-level economic status had lower odds ratios than did those in the other economic status groups. For suicide attempts, most odds ratios were increased among adolescents with high or low perceived economic status. Furthermore, the odds ratios were increased in the high-risk and nonuser groups for all economic groups (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Adjusted odds ratio for suicidal ideation and attempts by level of Internet use in perceived household economic status. (A) Adjusted odds ratios for suicidal ideation. (B) Adjusted odds ratio for suicide attempts. *Solid bars represent odds ratios with P < 0.05; striped bars represent odds ratios that are not statistically significant. **Adolescents who are Internet mild users with a middle level of economic status are the reference group.

Discussion

In this study, we examined associations between the level of Internet use and suicidal ideation/attempts and by their family structure and economic status during 3 consecutive years. To our knowledge, this is the first study to differentiate between Internet nonuser and Internet user groups and to examine the association of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts with addictive Internet use using multivariate logistic analysis in a nationally representative sample. This is the key strength of this study. We expected to find a positive association between Internet use and suicidal ideation/attempt. We also expected that participants who were socially vulnerable, such as those in single-parent households, those who were orphaned, and those with low economic status, would spend more time on the Internet and have more suicidal ideation/attempt than others.

Consistent with our hypothesis, the study results suggested positive association between Internet use and suicidal ideation/attempt. However, there was an unexpected finding, which was that adolescents who did not use the Internet were more likely to report suicidal ideation and suicide attempts than were adolescents who used the Internet at a moderate level (about 2 h per day). These findings were reflected consistently in a J-shaped trend in nearly all results of this study. This result was different from those of previous studies that divided subjects into only 3 groups based on levels of Internet use.25,26

The outcome of this analysis shows similarities with previous studies, including the finding that parents’ remarriage had a greater effect on an adolescents’ distress and depression than did parents’ separation or divorce because of the lack of emotional support from the parent15 and that poor family functioning predicted the incidence of Internet addiction.29 Economic status was related both to suicidal ideation/attempts and to Internet addiction. This finding was also consistent with previous studies.30,31 However, one outcome differed from a previous study.30 In our study, perceived high economic status was associated with a greater likelihood of attempted suicide than was perceived low economic status. One possible explanation is that the parents of adolescents with high economic status may have more education, leading them to hold higher expectations for adolescents, which, in turn, places the students under considerable pressure to perform well in school. In South Korea, one of the main causes of suicide is the stress caused by demands for good school performance.2,4

Some of previous studies showed positive influences of the Internet.32 For instance, the Internet worked as one type of community,33 a promotor of involvement opportunities,34 relationship developer,35 and information provider.32 Not only Korean adolescents but also other adolescents usually use the Internet as their stress releaser. For example, social network services/sites are typical online communities where personal information is shared with other public information. Users interact with real-life friends or strangers with the same interests.36 The previously unreported J-shaped trend many suggest that nonexcessive use of the Internet has a positive influence. As we mentioned in the introduction, the Internet penetration rate in Korea was 81.6% in 2014. This rate takes into account only computer-accessed Internet. Nowadays, smartphones also make the Internet very accessible to adolescents. Thus, adolescents’ nonuse of the Internet in Korea is usually due to their household’s economic situation or to their own academic reasons. Both situations may increase stress and thereby eventually lead to depression, which could in turn increase the risk of suicidal ideation/attempt.

Adolescence is a period of identity formation, and confusion and frustration are common experiences. Also, usually, the motivation to regulate addictive behaviors is low, because adolescents often do not recognize their use as addictive. Even if they notice their addictive use, at that point the ability to regulate is compromised, which makes their addictive behavior chronic.37 Addiction implies psychological and physical dependence, which attempts to control depression and anxiety, and adolescents may reflect deep insecurities and feelings of inner emptiness.25 Several risk factors for suicide have been identified, including a sense of isolation, lack of social support, acute emotional distress, relational or social losses, and stressful life events.38 The results of this and previous studies suggest that adolescents are vulnerable to environmental influences,39 especially stressful events such as changes in family structure15 and socioeconomic status,30,40 and they may lead to addictive use of the Internet, which is a form of entertainment that is easy to access anytime and anywhere, as a way to manage stress.5 However, forcing adolescents not to use the Internet may place them in an even more stressful situation and could thereby expose them to higher risk of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts. Thus, it is very important to establish a stable and reliable environment for adolescents. In this context, it is important to not only block Internet use but also to provide guidance that fosters appropriate Internet use as a tool for relieving stress. This finding is different from those reported in other studies and must be considered carefully.

Several limitations of this study should be noted. First, this study used cross-sectional data, which precludes inferences regarding causal relationships. Many previous studies showed that self-harmful adolescents used the Internet more frequently compared with other adolescents. Also, more than 5 h of Internet use or online gaming per day was associated with suicidal ideation and planning.32 It is difficult to confirm a causal relationship between Internet use and suicidal ideation/attempt. Still, including our study’s results and those of previous studies, these results suggest a strong association between Internet use and suicidal ideation/attempt. Second, although the survey was administered online so as to guarantee subjects’ anonymity, adolescents may have underreported or overreported personal characteristics in a socially acceptable manner. Third, this study’s main dependent variables and several covariates, such as depression and substance abuse, were measured in single-item measurement. Additional studies with more refined measurements for these variables may be needed to confirm our study results. Finally, although this was a nationally representative sample and the response rate was high, respondents were sampled from among school students; thus, selection bias due to exclusion of homeschoolers, absentees, and other exceptional children may exist. However, elementary and middle school education is compulsory in South Korea, and enrollment in schools is very high, even among adolescents aged 15 to 19 years (ages 5 to 14 years: 99%; ages 15 to 19 years: 86%9). Thus, we believe that any bias due to the exclusion of adolescents who do not attend school would be minimal.

Despite these limitations, our study had several strengths. First, as mentioned above, this study used nationally representative data. Second, to our knowledge, this study was the first to differentiate between Internet nonuser and Internet user groups and to examine associations of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts with addictive Internet use.

Conclusions

Significant associations between adolescents’ suicidal ideation/attempts and their Internet use were identified, as well as the relationships of these associations to family structure and perceived household economic status. In general, the addictive use of the Internet negatively affects adolescents’ suicidal behavior. Our study results suggests that programs intended to reduce adolescents’ suicide attempts and their suicidal ideation at a population level should consider family structure and household economic status. Suicide prevention programs should pay more attention to adolescents with Internet addiction. A future study should develop an accurate measurement to clarify the levels at which Internet use relieves the stress and those at which it does not. To do so, relationships between other health risk factors and suicidal behavior must be examined, as does that between Internet use and addictive smartphone use.

Acknowledgments

No funding was provided for this research. The authors have declared that they have no competing or potential conflicts of interest. The English in this document has been checked by at least 2 professional editors, both native speakers of English. For a certificate, please see http://www.textcheck.com/certificate/FS1GFQ.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. DiClemente RJ, Bradley E, Davis TL, et al. Adoption and implementation of a computer-delivered HIV/STD risk-reduction intervention for African American adolescent females seeking services at county health departments: implementation optimization is urgently needed. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2013;63(Suppl 1):S66–S71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Statistics Korea. 2012. annual report on the cause of death statistics [press release]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Society at a glance 2014: OECD social indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Statistics Korea. 2013. annual report on the adolescent statistics. ]. Daejeon: Statistics Korea; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tsitsika A, Janikian M, Schoenmakers TM, et al. Internet Addictive Behavior in Adolescence: a cross-sectional study in seven European countries. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2014;17(8):528–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. International Telecommunication Union. World telecommunication/ ICT indicators database 2014. Geneva (Switzerland; ): International Telecommunication Union; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Statistics Korea. Statistics on Internet use. Daejon: Statistics Korea; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kim DI, Chung YJ, Lee EA, et al. Development of Internet addiction proneness scale-short form (KS scale). Korea Journal of Counseling. 2008;9(4):1703–1722. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Education at a glance 2013. Paris: OECD Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Barber BK, Erickson LD. Adolescent social initiative. J Adolesc Res. 2001;16(4):326–354. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Martin G, Rotaries P, Pearce C, et al. Adolescent suicide, depression and family dysfunction. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1995;92(5):336–344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Paradis AD, Giaconia RM, Reinherz HZ, et al. Adolescent family factors promoting healthy adult functioning: a longitudinal community study. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2011;16(1):30–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Shagle SC, Barber BK. Effects of family, marital, and parent-child conflict on adolescent self-derogation and suicidal ideation. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1993;55(4):964–974. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garnefski N, Diekstra RFW. Adolescents from one parent, stepparent and intact families: emotional problems and suicide attempts. J Adolesc. 1997;20(2):201–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lee K, Namkoong K, Choi WJ, et al. The relationship between parental marital status and suicidal ideation and attempts by gender in adolescents: results from a nationally representative Korean sample. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(5):1093–1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kokkevi A, Rotsika V, Arapaki A, et al. Adolescents’ self-reported suicide attempts, self-harm thoughts and their correlates across 17 European countries. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2012;53(4):381–389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Santelli JS, Lowry R, Brener ND, et al. The association of sexual behaviors with socioeconomic status, family structure, and race/ethnicity among US adolescents. Am J Public Health. 2000;90(10):1582–1588. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Chou C, Hsiao MC. Internet addiction, usage, gratification, and pleasure experience: the Taiwan college students’ case. Comput Educ. 2000;35(1):65–80. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ha JH, Yoo HJ, Cho IH, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity assessed in Korean children and adolescents who screen positive for Internet addiction. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(5):821–825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Sung J, Lee J, Noh HM, et al. Associations between the risk of internet addiction and problem behaviors among Korean adolescents. Korean J Fam Med. 2013;34(2):115–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Griffiths M. Does Internet and computer “addiction” exist? Some case study evidence. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2000;3(2):211–218. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Ko CH, Yen JY, Chen CS, et al. Predictive values of psychiatric symptoms for Internet addiction in adolescents: a 2-year prospective study. JAMA Ped. 2009;163(10):937–943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Armstrong L, Phillips JG, Saling LL. Potential determinants of heavier Internet usage. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies. 2000;53(4):537–550. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Christakis DA. Internet addiction: a 21st century epidemic? BMC Med. 2010;8(1):61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Kim KH, Ryu EJ, Chon MY, et al. Internet addiction in Korean adolescents and its relation to depression and suicidal ideation: a questionnaire survey. Int J Nurs Stud. 2006;43(2):185–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Lin IH, Ko CH, Chang YP, et al. The association between suicidality and Internet addiction and activities in Taiwanese adolescents. Compr Psychiatry. 2014;55(3):504–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Choi HI, Jon DI, Jung MH, et al. Suicidal behavior and Internet use in adolescent depression. Korean J Psychopharmacol. 2012;23(2):65–73. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Davis RA. A cognitive-behavioral model of pathological Internet use. Comput Hum Behav. 2001;17(2):187–195. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ko CH, Yen JY, Yen CF, et al. Factors predictive for incidence and remission of internet addiction in young adolescents: a prospective study. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2007;10(4):545–551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Lewis S, Johnson J, Cohen P, et al. Attempted suicide in youth: its relationship to school achievement, educational goals, and socioeconomic status. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1988;16(4):459–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Hur MH. Demographic, habitual, and socioeconomic determinants of Internet addiction disorder: an empirical study of Korean teenagers. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2006;9(5):514–525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Daine K, Hawton K, Singaravelu V, et al. The power of the web: a systematic review of studies of the influence of the Internet on self-harm and suicide in young people. PloS One. 2013;8(10):e77555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Baker D, Fortune S. Understanding self-harm and suicide websites. Crisis. 2008;29(3):118–122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smithson J, Sharkey S, Hewis E, et al. Problem presentation and responses on an online forum for young people who self-harm. Discourse Studies. 2011;13(4):487–501. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Eichenberg C. Internet message boards for suicidal people: a typology of users. Cyberpsychol Behav. 2008;11(1):107–113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Kuss DJ, Griffiths MD. Online social networking and addiction—a review of the psychological literature. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2011;8(9):3528–3552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wiers RW, Bartholow BD, van den Wildenberg E, et al. Automatic and controlled processes and the development of addictive behaviors in adolescents: a review and a model. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2007;86(2):263–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. World Health Organization. Public health action for the prevention of suicide: a framework. Geneva (Switzerland): WHO Document Production Services; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Maciejewski DF, Creemers HE, Lynskey MT, et al. Overlapping genetic and environmental influences on nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidal ideation: different outcomes, same etiology? JAMA Psychiatry. 2014;71(6):699–705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Lupien SJ, King S, Meaney MJ, et al. Child’s stress hormone levels correlate with mother’s socioeconomic status and depressive state. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;48(10):976–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]