Abstract

A major focus of the American College of Epidemiology’s Policy Committee has been to review the translation of epidemiologic evidence into policy by developing case studies. This article summarizes crosscutting policy process lessons across the eight cases developed to date through two workshops held in 2009 and 2011. A framework for evidence-based public health policy has emerged to suggest that process, content and outcomes are all needed to help move policy forward. The most readily and apparent contributions from epidemiologists are towards content and outcomes activities and while this is apparent in all of the case studies presented, much of the 2011 workshop discussion focused on six process issues. Policy and process issues are not well incorporated into current epidemiologic training, and controversy remains over the role of the epidemiologist as an advocate for policy changes. As these case studies show, epidemiologic evidence impacts policy to address emerging public health problems yet few epidemiologists are formally trained in the domains to support policy development. As we continue to learn from current policy efforts we encourage the incorporation of these case studies and the emerging experience within epidemiologic training programs.

In order to better understand the policy process, a major focus of the American College of Epidemiology’s Policy Committee has been a series of symposia designed to review the translation of epidemiologic evidence into policy. The Committee has sponsored two special workshops resulting in a set of eight case studies. The first cases were published in June 2010, and this issue of the Annals of Epidemiology reports four new case studies. Previous cases covered a wide range of public health issues including compensation of veterans (1), regulation of secondhand smoke (2), blood alcohol limits for drivers (3), and physical activity in school (4). The four new cases address health disparities, cancer screening, HIV prevention among Latinos, and the National Salt Reduction Initiative (5). This article highlights key findings from the new case studies, and summarizes some crosscutting policy process lessons across all eight cases.

The importance of moving epidemiologic evidence into policy and practice is no longer a debate (6–8), but the question remains as to how to effectively impact policy change aligned with the knowledge we generate? A framework for evidence-based public health policy has emerged to suggest that process, content and outcomes are all needed to help move policy forward (9). The most readily and apparent contributions from epidemiologists in this schema are towards content and outcomes activities and while this is apparent in all the case studies presented, much of the discussion of workshop participants focused on process issues. Process issues are not well incorporated into current epidemiologic training and there remains controversy over the role of the epidemiologist as an advocate for policy changes and what that means (8, 10). Spasoff lists key elements of policy development and argues that epidemiology is central to each element, including policy choices, policy implementation and policy evaluation (11). It is interesting that some identified barriers to implementing effective public health policy involve scientists being isolated from the policy process, not wanting to get involved in a complex and time consuming policy process, not understanding the process and not having the skills to impact the process (10). It is also noteworthy that an element known to facilitate policy formulation is personal communication (12). It is clear that as a discipline we need to learn from past and ongoing efforts to influence policy, that different models will arise within different contexts and that the interface between individuals in the discipline and the policy process will be context dependent as shown here and by others (13).

The most important ingredient for success in moving epidemiologic evidence into policy seems to be placing a high priority on a specific issue and recognizing that this decision needs to be followed by a strong and long-term multidisciplinary team approach. Alone, epidemiologists are unlikely to be effective in creating policy, but as members of teams they may have diverse roles; particularly in identifying and quantifying issues, monitoring and evaluating outcomes of programs and policies.

According to Kingdon’s model, the policy content and the policy process are both important (14) He argues that policies move forward when elements of three “streams” come together. These streams are very distinct, and, when coupled together increase the odds of a policy being adopted. The first of these is the definition of the problem (e.g., epidemiologic data showing a high rate of HIV/AIDS). The second is the development of potential policies to solve that problem (e.g., identification of policy measures to achieve an effective HIV prevention strategy). Finally, there is the role of politics and public opinion, factors both inside and outside of government that influence the policymaking process (e.g., interest groups supporting or opposing the policy). Policy change occurs when a “window of opportunity” opens and the three streams push policy change through. Among the three phases (problem definition, policy development, politics/public opinion), epidemiologists probably play the most significant role in the problem definition phase and a supporting role in the policy development stage.

At the core of any policy change is the need for a strong understanding of the epidemiologic data, a critical evaluation of its strengths and weakness, transparency of that evaluation and the emergence of a compelling story that can be translated to a nonscientific audience. A multifaceted approach involves understanding the constituency that is affected by the issue and engaging key players in discussion of the issue. These players then become effective members of a team, assisting in the policy analysis necessary to bridge the gap between evidence and change. The team can then develop a more complete and compelling story directed to the target audience, build the network of stakeholders and media connections and create a broad consensus for change. The epidemiologist can focus solely on content contribution or become a part of the entire process.

These case studies have a number of characteristics in common that made each situation effective. In all examples, a key group chose to focus on one specific change for which there is epidemiologic evidence supporting the health benefits of this change. While any one change is multifactorial in nature, focusing on the most important or compelling issues supporting that change, and not digressing into the full spectrum of potential health benefits, appears to provide teams with the most likely chance for success. This also allows advocacy groups to mobilize around the issue (e.g., the American Cancer Society aligning with a policy to reduce cancer mortality).

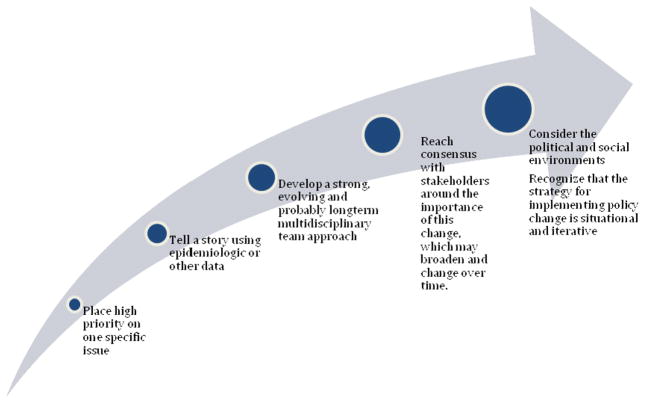

The type of epidemiologic data needed to make change may be quite simple. Descriptive patterns based on local data can provide a powerful impetus for local change as described by (Strathee et al., current issue). In this situation, a prevention strategy for the health issue of concern was readily available once the local problem was identified. In contrast, complex study designs are essential when the behaviors in question have not previously been demonstrated to be efficacious, when new evidence on behaviors emerges, and when weak associations are in play. Routes in which epidemiologic data may inform various types of policy decisions are discussed in (Carter-Pokras et al., current issue). Historically, a body of literature is necessary to guide decisions. However, matching the short time horizon between the interests of policy makers to the longer term efforts of researchers is a barrier to implementing effective public health policy (10). An understanding of the processes of policymaking (summarized in Figure 1) may help align the activities of researchers more closely with those in a position to develop and implement policies.

Figure 1.

Understanding policy processes

Having a consensus on a single critical element to direct a group effort towards change, the next step(s) become reaching a consensus around the importance of this change across a broader community of stakeholders. As pointed out in the cancer screening case study (Deppen et al., current issue) this process can be on a continuum and the stakeholders may change along this continuum. In the process of reaching a consensus with various agencies and organizations, key individuals emerge and become a part of your team. They are your eyes and ears to the world that cares about the issue. Using key players to assist in helping you understand the issue in the agencies and communities for which your issue is important will allow you to better evaluate and adjust your strategy for change. By developing a team approach, you accomplish a number of things. First, you don’t need to feel you are working in isolation and you multiply the labor force to get the job done. Second, your analysis will have the benefit of multiple perspectives that will inform the approach you take and improve the story you tell. While the role of advocacy is sometimes controversial for epidemiologists, you can provide needed information to other team members to affect policy even if you are not directly involved as an advocate.

The complexity and strategy for implementing policy change is situational and the role epidemiologists play in the policy debate is distinctly different depending on the maturity of the underlying science and the level of the policy debate as characterized by (Deppen et al., current issue). The risks and benefits associated with the recommendation or change need to be considered and must be transparent. Policy actions with known risks, such as ionizing radiation associated with mammography, have different trade-offs than preventive policy actions such as zoning ordinances that promote farmers markets within food deserts.

Political and communication environments are important and can be unpredictable. For example, the political environment around healthcare reform when the new breast cancer screening guidelines were announced may have heightened media and public reaction to the recommendations. The topic area, narrowness of the question, and general public acceptance of the information may impact the ability to effect change. For example, the National Salt Reduction Initiative is working with well established and accepted data relating salt intake to blood pressure and hypertension (Appel, current issue), making the rationale for salt reduction more straightforward while implementation strategies are proving more elusive.

As these case studies show, epidemiologic evidence impacts policy to address emerging public health problems yet few epidemiologists are formally trained in the domains to support policy development. As we continue to learn from our current policy efforts we need to incorporate this knowledge into training programs (8, 15). Table 1 focuses on policy training needs in epidemiology assuming that programs continually update curricula for novel analytic methods and new and emerging statistical methods that apply to the field (in particular with survey data), and that continuing education efforts are made to educate epidemiologists who have completed their formal training. Training may have multiple effects: directly help that subset of the discipline who elect to become involved in policy efforts at any stage of the process; help individuals focus research questions more concretely on impactful questions and provide a basis for epidemiologists to understand and minimize barriers to policy translation. Together these are results that may allow the field to quickly translate findings into informed policy and in so doing impact the health of the public. We encourage the incorporation of these case studies and the emerging experience within epidemiologic training programs.

Table 1.

Policy Training Needs of Epidemiologists

| 2011 Policy Case Review | 2006 Congress of Epidemiology Survey1 | Mid-Level Applied EpidemiologistCompetency2 |

|---|---|---|

| Evaluation methods |

|

Skill Domain 1 – Assessment and analysis Skill Domain 4- Community dimensions of practice |

| Mediation analysis |

|

Skill Domain 1 - Assessment and analysis |

| Mixed methods |

|

Skill Domain 1 - Assessment and analysis Skill Domain 2 - Basic Public Health Sciences Skill Domain 4 - Community Dimensions of Practice Skill Domain 5 - Cultural Competency |

| Multilevel analysis |

|

Skill Domain 1 - Assessment and analysis |

| Provide experiences and collaborations outside of the discipline |

|

Skill Domain 1 – Assessment and analysis Skill Domain 2 – Basic Public Health Sciences Skill Domain 4- Community dimensions of practice Skill Domain 5- Cultural competency Skill Domain 7 - Leadership and Systems Thinking |

| Learn how to tell the story, ask the right questions and frame solutions |

|

Skill Domain 1 – Assessment and analysis Skill Domain 2 - Basic Public Health Sciences Skill Domain 3 - Communication, Skill Domain 4 - Community Dimensions of Practice Skill Domain 5 - Cultural competency Skill Domain 6 - Financial and operational planning and management Skill Domain 8 - Policy development |

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge comments from participants of the April 2011 American College of Epidemiology policy committee meeting in St. Louis, Missouri. We also acknowledge funding support from the American College of Epidemiology and Washington University in St. Louis (Division of Public Health Sciences) for the April 2011 meeting.

List of Abbreviations

- HIV

Human immunodeficiency virus

- AIDS

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Samet JM, McMichael GH, 3rd, Wilcox AJ. The use of epidemiological evidence in the compensation of veterans. Ann Epidemiol. 2010 Jun;20(6):421–7. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Widome R, Samet JM, Hiatt RA, Luke DA, Orleans CT, Ponkshe P, Hyland A. Science, prudence, and politics: the case of smoke-free indoor spaces. Ann Epidemiol. 2010 Jun;20(6):428–35. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mercer SL, Sleet DA, Elder RW, Cole KH, Shults RA, Nichols JL. Translating evidence into policy: lessons learned from the case of lowering the legal blood alcohol limit for drivers. Ann Epidemiol. 2010 Jun;20(6):412–20. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Burgeson CR, Fisher MC, Ness RB. Translating epidemiology into policy to prevent childhood obesity: the case for promoting physical activity in school settings. Ann Epidemiol. 2010 Jun;20(6):436–44. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McGuire S Institute of Medicine. Strategies to Reduce Sodium Intake in the United States. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Adv Nutr. 2010 Nov;1(1):49–50. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rothman KJ, Poole C. Science and policy making. Am J Public Health. 1985 Apr;75(4):340–1. doi: 10.2105/ajph.75.4.340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Foxman B. Epidemiologists and public health policy. J Clin Epidemiol. 1989;42(11):1107–9. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(89)90052-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weed DL, Mink PJ. Roles and responsibilities of epidemiologists. Ann Epidemiol. 2002 Feb;12(2):67–72. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00302-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brownson RC, Chriqui JF, Stamatakis KA. Understanding evidence-based public health policy. Am J Public Health. 2009 Sep;99(9):1576–83. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.156224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brownson RC, Royer C, Ewing R, McBride TD. Researchers and policymakers: travelers in parallel universes. Am J Prev Med. 2006 Feb;30(2):164–72. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Spasoff RA. Epidemiologic methods for health policy. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Innvaer S, Vist G, Trommald M, Oxman A. Health policy-makers’ perceptions of their use of evidence: a systematic review. J Health Serv Res Policy. 2002 Oct;7(4):239–44. doi: 10.1258/135581902320432778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitman SSAM, Benjamins M, editors. Urban health: combating disparities with local data. New York, New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kingdon JW. Agendas, Alternatives, and Public Policies. New York: Addison-Wesley Educational Publishers, Inc; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brownson RC, Kelly CM, Eyler AA, Carnoske C, Grost L, Handy SL, Maddock JE, Pluto D, Ritacco BA, Sallis JF, Schmid TL. Environmental and policy approaches for promoting physical activity in the United States: a research agenda. J Phys Act Health. 2008 Jul;5(4):488–503. doi: 10.1123/jpah.5.4.488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Carter-Pokras OD, Spirtas R, Bethune L, Mays V, Freeman VL, Cozier YC. The training of epidemiologists and diversity in epidemiology: findings from the 2006 Congress of Epidemiology survey. Ann Epidemiol. 2009 Apr;19(4):268–75. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2009.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention/Council of State and Territorial Epidemiologists. Tier 2: Mid-Level Epidemiologist. 2008. Competencies for Applied Epidemiologists in Governmental Public Health Agencies. version 1.2. [Google Scholar]