Abstract

Meiotic recombination is believed to produce greater genetic variation despite the fact that deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)-replication errors are a major source of mutations. In some vertebrates, mutation rates are higher in males than in females, which developed the theory of male-driven evolution (male-biased mutation). However, there is little molecular evidence regarding the relationships between meiotic recombination and male-biased mutation. Here we tested the theory using the frog Rana rugosa, which has both XX/XY- and ZZ/ZW-type sex-determining systems within the species. The male-to-female mutation-rate ratio (α) was calculated from homologous sequences on the X/Y or Z/W sex chromosomes, which supported male-driven evolution. Surprisingly, each α value was notably higher in the XX/XY-type group than in the ZZ/ZW-type group, although α should have similar values within a species. Interestingly, meiotic recombination between homologous chromosomes did not occur except at terminal regions in males of this species. Then, by subdividing α into two new factors, a replication-based male-to-female mutation-rate ratio (β) and a meiotic recombination-based XX-to-XY/ZZ-to-ZW mutation-rate ratio (γ), we constructed a formula describing the relationship among a nucleotide-substitution rate and the two factors, β and γ. Intriguingly, the β- and γ-values were larger and smaller than 1, respectively, indicating that meiotic recombination might reduce male-biased mutations.

Keywords: meiotic recombination, male-biased mutation, male-driven evolution, sex chromosome, mutation rate, germ cell

1. Introduction

Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA)-replication errors during germline cell division are the primary source of mutations transmitted to the next generation. In most vertebrate species, germ cells undergo a greater number of divisions in males, during spermatogenesis, than in females, during oogenesis. In the 1940s, Haldane [1] reported that the majority of human mutations might be of paternal origin. In the 1980s, Miyata et al. [2] provided molecular evidence for male-biased mutations through DNA sequence analysis on X sex chromosomes and autosomes in mammals, which have an XX/XY-type sex determination system (male heterogamety). The theory that mutations arise more frequently in males than females is called ‘male-driven evolution’ [2,3]. This was verified in the 1990s in birds, which have a ZZ/ZW-type sex determination system (female heterogamety) [4]. Since then, molecular support for male-driven evolution has been provided in a few avian species, in several mammalian species [5], and in salmonid fish [6].

This evidence was obtained using formulae describing the relationship of the nucleotide-substitution rate (K) and the male-to-female mutation-rate ratio (α), which might reflect DNA-replication errors on homologous sequences between heterogametic sex chromosomes (X and Y or Z and W chromosomes) or between a sex chromosome and an autosome [2]. In the XX/XY-type sex-determining system, the probabilities that females and males can transmit X chromosomes are 2/3 and 1/3, respectively. However, Y chromosomes are always carried by males. Thus, the relative mutation frequency per generation for X and Y chromosomes are represented by (αXY + 2)/3 and αXY, respectively. Then, αXY could be estimated from the measurements of the nucleotide-substitution rate of Y chromosomes (KY) relative to that of X chromosomes (KX), KY/KX ratio (3αXY/(αXY + 2)). By contrast, males or females have two Z chromosomes or one Z and one W chromosome, respectively, in the ZZ/ZW-type system. Because relative mutation frequencies per generation for Z and W chromosomes are shown by (2αZW + 1)/3 and 1, respectively, αZW could be calculated from KZ/KW = (2αZW + 1)/3. The α values should be greater than 1 in the case of the theory of male-driven evolution (male-biased mutation). In fact, the estimated values of α in various homologous sequences of several species range from 2 to 7; this variation might be due to differences in such factors as genomic region, species-dependent generation time, and the number of germ-cell divisions [5]. At present, the significance of the variations in α values with regard to species diversity or continuity is largely unknown.

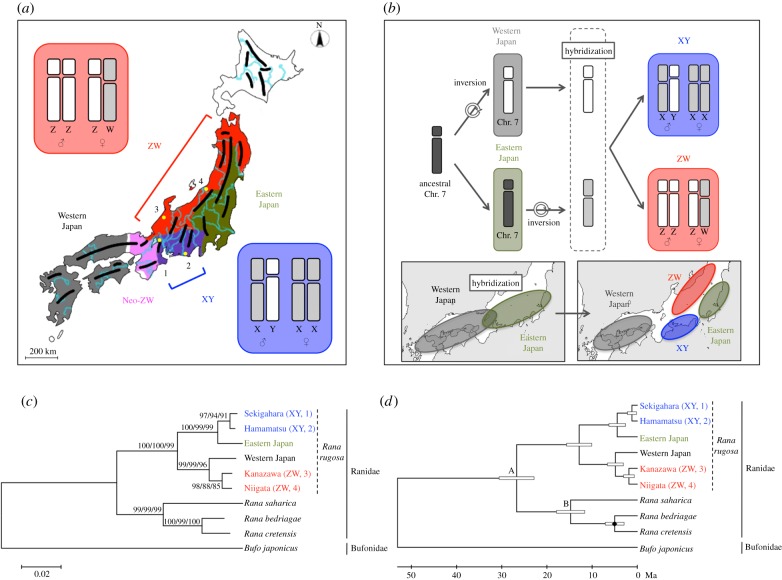

In Japan, the frog Rana rugosa can be divided into five genetic groups, which are called ‘Western Japan’, ‘Eastern Japan’, ‘XY’, ‘ZW’, and ‘Neo-ZW’ groups. In the first three groups, sex is determined by an XX/XY-type system, while the remaining two groups have a ZZ/ZW-type system (figure 1a) [7–10]. It is rare to find distinct sex-determining systems within a single species. From analyses of chromosomal structures, artificial crossing, and phylogeny for this species, Miura et al. [7] proposed that a pericentromeric inversion on ancestral chromosome 7 led to chromosome 7 in the Western Japan group, which corresponds to the original type of Z and Y sex chromosomes. Another inversion on chromosome 7 in Eastern Japan formed the original type of W and X sex chromosomes. The hybridization between the ancestors of the Western Japan and Eastern Japan groups produced the XY and ZW groups (figure 1b). In other words, the four X, Y, Z, and W sex chromosomes share the same origin at chromosome 7; the Z and Y or the W and X chromosomes are derived from chromosome 7 from the Western or Eastern Japan group, respectively. There are morphological differences between the X and Y chromosomes or the Z and W chromosomes because of the two inversions: both the XY and ZW groups have heteromorphic sex chromosomes in males and females, respectively (figure 1b). A second hybridization between the ancestors of the Western Japan and XY groups might have led to the birth of the Neo-ZW group [10]. Therefore, this species can be useful for various studies, including investigations of the evolutionary relationships between sex-determining genes and systems, genetic and population diversity, and sex-bias of mutations.

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic tree analyses based on mitochondrial nucleotide sequences of four genetic groups in Rana rugosa. (a) The distribution of five R. rugosa genetic groups in Japan [7]. Specimens were collected from Sekigahara (1) and Hamamatsu (2) for the XY group, and from Kanazawa (3) and Niigata (4) for the ZW group. The black and blue/green bent lines represent big mountain ranges and large rivers, respectively. (b) The evolutionary scenario of the X/Y and Z/W sex chromosomes. An inversion on the ancestral chromosome 7 led to chromosome 7 in the Western Japan group, which was the original type of Z and Y sex chromosomes. Another inversion on chromosome 7 in Eastern Japan formed the original type of W and X sex chromosomes. The hybridization between the ancestors of the Western Japan and Eastern Japan groups produced the XY and ZW groups. (c) The maximum likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree based on nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA genes. Bufo japonicus was used as an outgroup. A best-fit nucleotide-substitution model was selected by model selection. The same topology was obtained using neighbour-joining (NJ) and maximum-parsimony (MP) analyses. Numerals at each node denote the NJ/ML/MP bootstrap percentage values of 1 000 replications. (d) A time-calibrated ML phylogenetic tree based on the nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA genes. To calibrate the molecular clock, the divergence time between R. bedriagae and R. cretensis was fixed at 5 million years ago (Ma). White box, 95% confidence interval; black diamond, calibration point.

To verify sex-biased mutation rates in an amphibian species and find clues to explain the variety of α values found in mammalian and avian species, we compared the α values in five sex-linked homologous sequences in the XY and ZW groups of R. rugosa. We detected male-biased mutations in both the XY group with the XX/XY-type system and ZW group with ZZ/ZW-type system; this is the first verification of the theory of male-driven evolution in an amphibian species. We also found that the α values in the XY group were higher than in the ZW group for all the regions examined. To explain this difference, we modified the formula for male-driven evolution by defining a replication-based male-to-female mutation-rate ratio (β) and a meiotic recombination-based XX-to-XY or ZZ-to-ZW mutation-rate ratio (γ). Based on our observation of male germ-cell meiosis and estimated γ values, our findings suggest that meiotic recombination plays a role in reducing mutations formed by DNA-replication errors in germ cells.

2. Material and methods

(a). Frogs

Male and female frogs were collected from each R. rugosa population in Japan. Details are supplied in the electronic supplementary material.

(b). Construction of molecular phylogenetic trees and estimation of divergence time

Phylogenetic analyses were performed using the integrated tool MEGA5 [11]. DNA sequences were aligned using MUSCLE [12], and gaps (insertions/deletions) were removed. A molecular clock test of the mitochondrial sequence tree was performed by comparing the ML value for the given topology with and without the molecular clock constraints under the Tamura-Nei model. To calibrate the molecular clock, the divergence between R. bedriagae and R. cretensis was used as the calibration point [13]. The divergence time was estimated to be 5 million years ago (Ma) based on the palaeogeographical event, the isolation of the island of Crete from the neighbouring mainland (Peloponnesos).

(c). Meiotic chromosome preparation and Giemsa staining

Meiotic chromosomes were prepared according to the method of Schmid et al. [14]. Details are supplied in the electronic supplementary material.

(d). Formulae for male-driven evolution and recombination

We constructed a new formula for male-driven evolution, based on the formula described by Miyata et al. [2]: β was defined as the male-to-female mutation-rate ratio driven by DNA-replication errors, and γ was set as the XX-to-XY or ZZ-to-ZW mutation-rate ratios, which are affected by meiotic recombination. The relative mutation frequencies per generation of sex chromosomes in the modified formulae were as follows: (βXY + 2γXY)/3 for X chromosomes, βXY for Y chromosomes, (2βZWγZW + 1)/3 for Z chromosomes, and 1 for W chromosome. The relationships among α, β, and γ are as follows: αXY = βXY/γXY in XX/XY systems and αZW = βZWγZW in ZZ/ZW systems.

3. Results

(a). Phylogenetic analysis of mitochondrial DNA for 12S and 16S rRNA from four Rana rugosa genetic groups

To clarify the genetic relationships among the Western Japan group, Eastern Japan group, Kanagawa and Niigata populations of the ZW group, and Sekigahara and Hamamatsu populations of the XY group in R. rugosa, their phylogenetic tree was constructed using about 0.8 kb sequences of the mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA genes with R. bedriagae, R. cretensis, R. saharica, and Bufo japonicus by the ML method (figure 1c). The four R. rugosa groups were clearly divided into two major phylogenetic clusters, in which the branches showed very high statistical support: the two populations of the XY group and the Eastern Japan group were in one cluster, and the two populations of the ZW group and the Western Japan group in the other (figure 1c). This result suggested that the mitochondrial DNA of the XY and ZW groups was derived from that of the Eastern Japan and Western Japan groups, respectively. Importantly, each population of the XY or ZW group was substantially separated in the tree. The same topology was observed in three phylogenetic trees constructed using the NJ, ML, and MP methods.

(b). Estimation of divergence time for the Rana rugosa populations

To estimate divergence times based on the mitochondrial sequences of 12S and 16S rRNAs in the R. rugosa populations, we tested the molecular clock by comparing the ML value for the given topology with and without the molecular clock (electronic supplementary material, table S2). The null hypothesis of an equal evolutionary rate throughout the tree was not rejected at a 5% significance level (p = 0.932). Next, we estimated the divergence time of each node in figure 1d based on the assumption that the divergence between R. cretensis and R. bedriagae occurred at 5 Ma [13]. The split between the Western Japan and Eastern Japan groups occurred at 12.9 (95% confidence interval (CI): 10.1–15.7) Ma. The hybridization between the ancestors of these two groups produced the XY and ZW groups at 4.4 (95% CI: 2.6–6.3) and 4.8 (95% CI: 3.0–6.6) Ma, respectively (electronic supplementary material, table S3). The divergences between Sekigahara and Hamamatsu populations or Kanazawa and Niigata populations occurred at 1.2 (95% CI: 0.5–1.9) or 1.9 (95% CI: 0.7–3.0) Ma, respectively.

(c). The Y/Z and X/W chromosomes originated from chromosome 7 of the Western Japan or Eastern Japan groups, respectively

The Y/Z and X/W chromosomes might have originated from the Western Japan and Eastern Japan groups, respectively [7,9]. To verify this evolutionary scenario, we cloned and identified homologous (orthologous and paralogous) nucleotide sequences of five sex chromosome-linked regions from the Sekigahara and Hamamatsu populations in the XY group and from the Kanazawa and Niigata populations in the ZW group, and the corresponding regions from the Western Japan and Eastern Japan groups. More than three clones from each ZZ or XX individual and about 10 clones from each ZW and XY individual were sequenced. We found that all of the ZZ- or XX-derived clones from each individual have the same sequence. About half of the ZW- or XY-derived sequences were identical to the ZZ- or XX-derived ones from each corresponding population, while the remaining clones had a few different sequences from them. Then we recognized the different sequences as the W- or Y-linked ones. In addition, we confirmed the Z, W, X, and Y allele sequences based on sequence information of the genes from gynogenetic diploid embryos of ZZ, WW, XX, and YY; the YY embryos were gynogenetically produced from a WY female hybrid between a ZW female and XY male [15]. Sequences cloned from R. nigromaculata were used as an outgroup. The four genes, Sox3 (Sry-type HMG box 3), Tl encoding the ADP/ATP translocase, Ar encoding androgen receptor, and Sf-1 encoding steroidogenic factor-1 had been mapped on the X, Y, Z, and W sex chromosome in R. rugosa [16,17]. Then we cloned not only the coding regions of Sox3 and Tl, but also the non-exon regions including Ar intron 5 and Sf-1 intron 2, and Sox3 5′-flanking regions. Higher mutation rates were expected in the non-exon sequences than in the exon ones. After sequence determination, we analysed 921 bp of the Sox3 coding region, 752 bp of the Tl coding region, 1.5–3.3 kbp of the Ar intron 5, about 1.6 kbp of the Sf-1 intron 2, and 2.3–3.3 kbp of the 5′-flanking region of Sox3. Phylogenetic trees were constructed for these five regions using the 11 XY, ZW, and autosomal sequences as described above, using the NJ, ME, and ML methods (electronic supplementary material, figure S1). Overall, the bootstrap values obtained between the R. rugosa populations were low; the populations appeared to have diverged more recently than the XY and ZW groups in R. rugosa (figure 1b). Very similar topologies were obtained among four of the five trees, but the topology for the Ar intron 5 was somewhat different. In the four similar trees, there were two main clusters. One included the sequences from the autosome of Western Japan and the Y/Z sex chromosomes of the Sekigahara, Hamamatsu, Niigata, and Kanazawa populations. The other cluster contained the sequences from Eastern Japan and the X/W sex chromosomes of the four populations. All five trees, including the tree for the Ar intron 5, were similar in that the cluster containing the Y/Z sequences was clearly distinct from the cluster containing the X/W sequences. These results were consistent with the evolutionary scenario of sex chromosome differentiation in the XY and ZW groups [7].

(d). Male-driven evolution is supported in both the XX/XY- and ZZ/ZW-type sex-determining systems in Rana rugosa, with larger α values in the XY group than the ZW group

To clarify whether the mutations in R. rugosa were male- or female-biased, we first calculated the nucleotide-substitution rates (K) of the X-, Y-, Z-, and W-linked sequences in the five regions and the combined sequences by pairwise comparisons between the Sekigahara and Hamamatsu populations in the XY group or between the Kanazawa and Niigata populations in the ZW group (electronic supplementary material, table S4). Mating does not seem to have occurred between the Sekigahara and Hamamatsu populations in the XY groups or between the Kanazawa and Niigata populations in the ZW group for approximately 1–2 Myr (figure 1d; electronic supplementary material, table S3), because of the geographical barrier of distance between the populations (figure 1a). The mutation rates in the noncoding sequences of Ar intron 5, Sf-1 intron 2, and the Sox3 5′-flanking region tended to be higher than in the coding sequences of Sox3 and Tl. Importantly, the values for KY or KZ were substantially higher than for KX or KW in almost all of the regions, although KZ was equal to KW in the Sox3 coding sequence. Next, we estimated the male-to-female rate ratio (α) and the 95% CI of the formula as described in the Introduction section [2,3]. We found that all of the α values for the five regions, except for the Sox3 coding sequences in the ZW group, were greater than 1, indicating male-biased mutations. In the combined sequences, KY/KX, KZ/KW, αXY, and αZW were 2.6 (95% CI: 1.2–4.0), 3.0 (95% CI: 1.9–4.2), 12.5 (95% CI: 1.3–∞), and 4.0 (95% CI: 2.4–5.7), respectively. Because the topology of the Ar intron 5 was somewhat curious as mentioned in subsection (c), we also calculated them in combined sequences without the Ar region: KY/KX, KZ/KW, αXY, and αZW were 2.5 (95% CI: 1.1–3.9), 1.7 (95% CI: 0.9–2.4), 10.2 (95% CI: 1.2–∞), and 2.0 (95% CI: 0.9–3.1), respectively. We obtained similar results with and without Ar intron 5. These findings indicated that the theory of male-driven evolution was supported in both the XY and ZW groups, that is, in the XX/XY- and ZZ/ZW-type sex-determining systems in R. rugosa. Intriguingly, the αXY values were higher than the corresponding αZW values in all of the regions.

(e). Lack of chiasmata in the interstitial regions between homologous chromosomes at meiotic metaphase I in the XY and ZZ spermatocytes of Rana rugosa males

In several frog species belonging to Neobatrachia, there does not appear to be any pairing between homologous chromosomes except at terminal regions in the male meiotic germ cells [18]. To confirm that the same is true for R. rugosa, we observed chromosomes in meiotic metaphase I of male Hamamatsu and Mutsu frogs in the XY and ZW groups, respectively (figure 2). All 13 bivalents formed ring- or rod-shaped configurations with no chiasmata in the interstitial regions, in both the XY and ZZ males. One paired rod-shaped bivalent was observed in the XY males, but not in the ZZ males (figure 2, arrow); this pair probably consisted of the X and Y chromosomes.

Figure 2.

Restricted pairing of homologous chromosomes in the XY and ZZ males of Rana rugosa. Chromosomes at meiotic metaphase I were prepared using mature Hamamatsu and Mutsu males from the XY and ZW groups, respectively, and were stained with Giemsa. A representative among 18 or 33 pictures of a male from the Hamamatsu or Mutsu population, respectively, are shown. Note that there was no pairing between homologous chromosomes except at terminal regions in all the pictures. An arrow indicates an X−Y sex chromosome pair. Scale bar, 10 µm. (Online version in colour.)

4. Discussion

In this study, we first performed phylogenetic analysis using nucleotide sequences of the mitochondrial 12S and 16S rRNA genes from four groups, the Eastern Japan group, the Western Japan group, the XY group (Sekigahara and Hamamatsu populations), and the ZW group (Kanazawa and Niigata populations) in R. rugosa. The neo-ZW group was not used, because the recent ancestors of the Western Japan and XY groups might have led to the birth of the Neo-ZW group [10]. As shown in figure 1c, the Sekigahara and Hamamatsu populations in the XY group or the Kanazawa and Niigata populations in the ZW group were most closely related, but could be separated from each other in all three trees using the NL, ML, and MP methods. This result suggests that there is a restricted gene flow between the two populations of the same group. Mountain ranges and big rivers might cause reproductive isolation in anuran amphibians (figure 1a). Then we verified that the Y/Z or X/W chromosomes in the XY and ZW groups were derived from chromosome 7 of the Western or Eastern Japan groups, respectively, through phylogenetic analysis using mitochondrial DNA (figure 1) and sex-linked sequences (electronic supplementary material, figure S1), supporting the evolutional scenario of the X/Y and Z/W sex chromosomes as shown in figure 1b. By verification of the history of the Y/Z and X/W chromosomes in R. rugosa (figure 1), the molecular mechanisms for male-driven evolution can be investigated through homologous sequences in the distinct heterogametic sex-determining systems within the species. The theory of male-driven evolution is supported in both XX/XY-type mammalian and ZZ/ZW-type avian species [5]. However, it would make little sense to compare the male-to-female mutation-rate ratio (α) between XX/XY-type and ZZ/ZW-type species, because the target sequences have no homologous relationships. In addition, each species has a different germline history. Here, we not only showed male-driven evolution in both XX/XY-type and ZZ/ZW-type R. rugosa systems, which is the first finding in amphibians, but also observed that the α values were significantly higher in the XY than in the ZW group (electronic supplementary material, table S4). This difference is intriguing, because the number of germ-cell divisions during gametogenesis should be very similar in these two groups within the same species. In other words, the values of αXY and αZW should be very similar if α were affected mainly by germ-cell replication.

It is generally believed that mutation rates are mainly affected by DNA-replication errors. Other contributing factors include DNA methylation, GC content, and recombination. Although we compared the GC content of the regions used in this study, there were no significant differences among the X-, Y-, Z-, and W-linked sequences from the two XY and ZW populations and the Western and Eastern Japan-derived sequences in all of the five genomic regions (data not shown). During meiosis, recombination usually occurs in homozygotic chromosomes (X–X and Z–Z), but it is restricted in heterozygotic chromosomes (X–Y and Z–W). Interestingly, in several frog species belonging to the Rana, Hyla, and Bufo genera, there appears to be no pairing between homologous chromosomes except in the terminal regions during male germ-cell meiosis, resulting in low crossover [18]. Recently, Guerrero et al. [19] indicated very little recombination in male germ cells in Hyla genera, which could maintain homomorphism in the X–Y chromosomes. It is also reported that the recombination rates in germ cells are much lower in males than in females in R. nigromaculata, R. brevipoda, and R. temporaria [20,21]. In this study, we showed that chiasmatas did not occur in the interstitial regions between homologous chromosomes, including the pair of Z chromosomes, in male gonads of the ZW groups of R. rugosa (figure 2). This observation suggests that chromosomal crossover does not occur in most regions of the Z chromosomes, including the Z-linked genes Sox3, Tl, Ar, and Sf-1. In fact, these four genes were mapped to the interstitial regions of the Z chromosome by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis [16,17]. Meiotic recombination during chromosomal crossover should be closely related to the elimination or fixation of DNA-replication errors occurring during mitosis in germ cells [22]. The αZW values calculated by conventional methods for the ZW group of R. rugosa (electronic supplementary material, table S4) should mainly reflect replication errors, since there would be few recombination events between the Z-chromosome DNA regions analysed in this study. By contrast, the αXY values in the XY group could be affected not only by DNA-replication errors, but also by DNA recombination on chiasmata between the homologous X chromosomes.

Miyata et al. [2] defined α as a male-to-female mutation rate, which might mainly reflect DNA-replication errors in view of a greater number of divisions in male germ cells than in female germ cells (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). By consideration of meiotic recombination discussed above, we modified the conventional formula of sex-biased mutations for male-driven evolution by subdividing α into two new factors, β and γ, β was defined as a ratio of the replication-based male-to-female mutation rate, which would mainly reflect the difference of DNA-replication errors between male and female germ-cell mitosis (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). By contrast, γ was set as an XX-to-XY or ZZ-to-ZW mutation-rate ratio, which is affected by meiotic recombination differences between the homogeneous (XX or ZZ) and heterogeneous (XY or ZW) sex chromosomes (electronic supplementary material, figure S2). In the XX/XY-type sex-determining system, meiotic recombination can occur at various sites of the two X chromosomes in females, but at restricted sites within the region of the X–Y pairing in males. Then, we set the relative mutation frequency per generation for X and Y chromosomes as (βXY + 2γXY)/3 and βXY, respectively (figure 3). In the ZZ/ZW-type system, we constructed another formula for Z and W chromosomes as (2βZWγZW + 1)/3 and = 1, respectively (figure 3). αXY and αZW in the conventional formula turn out to be equal to βXY/γXY or βZWγZW in the XX/XY-type or ZZ/ZW-type systems, respectively (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Conventional and modified formulae for male-driven evolution and/or recombination in XX/XY and ZZ/ZW systems. (Online version in colour.)

We next investigated the nucleotide-substitution rates in the XY and ZW groups in R. rugosa using our proposed formulae. As mentioned, there should be almost no difference in DNA-replication errors within the two groups in the same species. Therefore, we postulated that βXY was equal to βZW with our formula. Because meiotic recombination should rarely occur between the Z–Z and Z–W chromosomes in the ZW group, we set γZW = 1. Under these conditions, the replication-based βZW values in the modified formula were equal to the αZW values calculated using the conventional formula. Under these assumptions, that is, βXY = βZW, γZW = 1, and βZW = αZW, we estimated β and γXY (table 1). The β values for the five regions, except for the Sox3 coding sequences, were greater than 1, indicating that the replication-based mutations were male-biased (table 1). Importantly, all of the γXY values calculated were smaller than 1 (table 1). This result suggests that meiotic recombination between the X–X chromosomes reduces mutations by male-biased DNA-replication errors on the X chromosomes in male germ cells. The γXY values ranged from 0.1 to 0.6; these variations might have been caused by chromosomal region/position-dependent differences in meiotic-recombination frequency. In any case, this modified formula may shed light on an opposing relationship between replication-based, male-driven evolution and meiotic recombination (figure 3 and electronic supplementary material, figure S2). Moreover, this formula may be useful for understanding how recombination in germline cells is involved in mutations transmitted to the next generation in other organisms. It will be interesting to address this question using several model animals with mutants for meiotic recombination, or fruit flies, whose males have no meiotic recombination [23,24].

Table 1.

Estimation of β and γ in the XX/XY- and ZZ/ZW-type systems in Rana rugosa. β, replication-based male-to-female mutation-rate ratios; γ, recombination-based XX-to-XY or ZZ-to-ZW mutation-rate ratios; α, male-to-female mutation-rate ratio; n.d, not determined. βXY and βZW are equal within the species. γZW is set as 1 because meiotic recombination did not appear to occur in the ZW group of Rana rugosa in the five genomic regions examined.

| conventional formula | modified formula |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| sex chromosome constitution | α (αXY≠αZW) | β (βXY= βZW) | γXY and γZW | |

| Sox3 | XX/XY | 10.1 | 1.0 | 0.1 |

| coding | ZZ/ZW | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1 |

| Tl | XX/XY | 4.0 | 2.5 | 0.6 |

| coding | ZZ/ZW | 2.5 | 2.5 | 1 |

| Ar | XX/XY | 34.7 | 13.6 | 0.4 |

| intron 5 | ZZ/ZW | 13.6 | 13.6 | 1 |

| Sf-1 | XX/XY | ∞ | 11.4 | n.d. |

| intron 2 | ZZ/ZW | 11.4 | 11.4 | 1 |

| Sox3 | XX/XY | 6.5 | 2.0 | 0.3 |

| 5′-flanking region | ZZ/ZW | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1 |

| combined | XX/XY | 12.5 | 4.0 | 0.3 |

| sequence | ZZ/ZW | 4.0 | 4.0 | 1 |

| combined sequence | XX/XY | 10.2 | 2.0 | 0.2 |

| except for Ar intron 5 | ZZ/ZW | 2.0 | 2.0 | 1 |

In general, meiotic recombination is believed to produce greater genetic variation, which could confer a more flexible capacity for survival and/or propagation against environmental changes. Muller [25] proposed that meiotic recombination of the sexual reproduction system could eliminate deleterious mutations from populations. Our findings in this study suggest that recombination in meiosis could counteract DNA-replication errors in mitosis occurring during gametogenesis. In other words, recombination might protect against or balance the accumulation of mutations in germ cells. In fact, deletional mutations have accumulated in the Y chromosomes of most mammals and in the W chromosomes of most birds, because a system of DNA repair through homologous recombination might not function [26,27]. Even on autosomes, meiotic recombination might neutralize replication-based male-driven evolution, although we could not verify this possibility in our system. Nevertheless, our study may improve our understanding of the advantages of sexual and asexual reproductive systems.

In the future, we will verify our hypothesis that meiotic recombination contributes to the reduction of DNA-replication errors occurring in male germ cells by using several individuals in each population of the XY, ZW, Western Japan, or Eastern Japan group in the species.

5. Conclusion

We supported the theory of male-driven evolution (male-biased mutation) in an amphibian species R. rugosa having both XX/XY- and ZZ/ZW-type sex determination systems. Moreover, we propose a new formula describing the relationship among a nucleotide-substitution rate, a replication-based male-to-female mutation-rate ratio, and a meiotic recombination-based XX-to-XY/ZZ-to-ZW mutation-rate ratio. The analysis using this formula indicated that meiotic recombination might mainly reduce male-biased mutations derived from DNA-replication errors occurring in male germ cells.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr Kei Tamura (Kitasato University) for helpful discussions.

Ethics

The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Kitasato University approved all the experimental procedures involving the frog R. rugosa and R. nigromaculata. This study used only frogs.

Data accessibility

See the electronic supplementary material.

Authors' contributions

S.M., M.I., and I.M. designed the study and wrote the manuscript. S.M., M.O., H.O., K.M., N.T., and I.M. performed the experiments and analyses. All authors read and approved the final manuscripts.

Competing interests

We have no competing interests.

Funding

This work was supported by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology (22132003 to M.I.).

References

- 1.Haldane JB. 1947. The mutation rate of the gene for haemophilia, and its segregation ratios in males and females. Ann. Eugen. 13, 262–271. ( 10.1111/j.1469-1809.1946.tb02367.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Miyata T, Hayashida H, Kuma K, Mitsuyasu K, Yasunaga T. 1987. Male-driven molecular evolution: a model and nucleotide sequence analysis. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 52, 863–867. ( 10.1101/SQB.1987.052.01.094) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shimmin LC, Chang BH, Li WH. 1993. Male-driven evolution of DNA sequences. Nature 362, 745–747. ( 10.1038/362745a0) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ellegren H, Fridolfsson AK. 1997. Male-driven evolution of DNA sequences in birds. Nat. Genet. 17, 182–184. ( 10.1038/ng1097-182) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li WH, Yi S, Makova K. 2002. Male-driven evolution. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 12, 650–656. ( 10.1016/S0959-437X(02)00354-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ellegren H, Fridolfsson AK. 2003. Sex-specific mutation rates in salmonid fish. J. Mol. Evol. 56, 458–463. ( 10.1007/s00239-002-2416-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miura I, Ohtani H, Nakamura M, Ichikawa Y, Saitoh K. 1998. The origin and differentiation of the heteromorphic sex chromosomes Z, W, X, and Y in the frog Rana rugosa, inferred from the sequences of a sex-linked gene, ADP/ATP translocase. Mol. Biol. Evol. 15, 1612–1619. ( 10.1093/oxfordjournals.molbev.a025889) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ogata M, Lee JY, Kim S, Ohtani H, Sekiya K, Igarashi T, Hasegawa Y, Ichikawa Y, Miura I. 2002. The prototype of sex chromosomes found in Korean populations of Rana rugosa. Cytogenet. Genome Res. 99, 185–193. (doi:71592) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miura I. 2007. An evolutionary witness: the frog Rana rugosa underwent change of heterogametic sex from XY male to ZW female. Sex Dev. 1, 323–331. ( 10.1159/000111764) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogata M, Hasegawa Y, Ohtani H, Mineyama M, Miura I. 2008. The ZZ/ZW sex-determining mechanism originated twice and independently during evolution of the frog, Rana rugosa. Heredity (Edinb.) 100, 92–99. ( 10.1038/sj.hdy.6801068) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tamura K, Peterson D, Peterson N, Stecher G, Nei M, Kumar S. 2011. MEGA5: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis using maximum likelihood, evolutionary distance, and maximum parsimony methods. Mol. Biol. Evol. 28, 2731–2739. ( 10.1093/molbev/msr121) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Edgar RC. 2004. MUSCLE: a multiple sequence alignment method with reduced time and space complexity. BMC Bioinform. 5, 113 ( 10.1186/1471-2105-5-113) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lymberakis P, Poulakakis N, Manthalou G, Tsigenopoulos CS, Magoulas A, Mylonas M. 2007. Mitochondrial phylogeography of Rana (Pelophylax) populations in the Eastern Mediterranean region. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 44, 115–125. ( 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.03.009) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schmid M, Olert J, Klett C. 1979. Chromosome banding in Amphibia III. Sex chromosomes in Triturus. Chromosoma 71, 29–55. ( 10.1007/BF00426365) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Miura I, Ohtani H, Ogata M. 2012. Independent degeneration of W and Y sex chromosomes in frog Rana rugosa. Chromosome Res. 20, 47–55. ( 10.1007/s10577-011-9258-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uno Y, Nishida C, Yoshimoto S, Ito M, Oshima Y, Yokoyama S, Nakamura M, Matsuda Y. 2008. Diversity in the origins of sex chromosomes in anurans inferred from comparative mapping of sexual differentiation genes for three species of the Raninae and Xenopodinae. Chromosome Res. 16, 999–1011. ( 10.1007/s10577-008-1257-z) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miura I, Ezaz T, Ohtani H, Uno Y, Nishida C, Matsuda Y, Graves J. 2009. The W chromosome evolution and sex-linked gene expression in the Japanese frog Rana rugosa. In Sex chromosomes: genetics, abnormalities, and disorders, pp. 123–140. New York, NY: Nova Science Publishers, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morescalchi A. 1973. Amphibia. In Cytotaxonomy and vertebrate evolution, pp. 233–348. New York, NY: Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guerrero RF, Kirkpatrick M, Perrin N. 2012. Cryptic recombination in the ever-young sex chromosomes of Hylid frogs. J. Evol. Biol. 25, 1947–1954. ( 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2012.02591.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sumida M, Nishioka M. 1994. A pronounced sex difference when two linked loci of the Japanese brown frog Rana japonica are recombined. Biochem. Genet. 32, 361–369. ( 10.1007/BF02426898) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Matsuba C, Alho JS, Merilä J. 2010. Recombination rate between sex chromosomes depends on phenotypic sex in the common frog. Evolution 64, 3634–3637. ( 10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.01076.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Felsenstein J. 1974. The evolutionary advantage of recombination. Genetics 78, 737–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Orr-Weaver TL. 1995. Meiosis in Drosophila: seeing is believing. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 10 443–10 449. ( 10.1073/pnas.92.23.10443) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Singh B, Banerjee R. 1996. Spontaneous recombination in males of Drosophila bipectinata. J. Biosci. 21, 775–779. ( 10.1007/BF02704718) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Muller HJ. 1964. The relation of recombination to mutational advance. Mutat. Res. 106, 2–9. ( 10.1016/0027-5107(64)90047-8) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Graves JA. 2006. Sex chromosome specialization and degeneration in mammals. Cell 124, 901–914. ( 10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.024) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mank JE, Ellegren H. 2007. Parallel divergence and degradation of the avian W sex chromosome. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 389–391. ( 10.1016/j.tree.2007.05.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

See the electronic supplementary material.