Abstract

The aim of our study is to investigate whether single-nucleotide dystrophin gene (DMD) variants associate with variability in cognitive functions in healthy populations. The study included 1240 participants from the Erasmus Rucphen family (ERF) study and 1464 individuals from the Rotterdam Study (RS). The participants whose exomes were sequenced and who were assessed for various cognitive traits were included in the analysis. To determine the association between DMD variants and cognitive ability, linear (mixed) modeling with adjustment for age, sex and education was used. Moreover, Sequence Kernel Association Test (SKAT) was used to test the overall association of the rare genetic variants present in the DMD with cognitive traits. Although no DMD variant surpassed the prespecified significance threshold (P<1 × 10−4), rs147546024:A>G showed strong association (β=1.786, P-value=2.56 × 10−4) with block-design test in the ERF study, while another variant rs1800273:G>A showed suggestive association (β=−0.465, P-value=0.002) with Mini-Mental State Examination test in the RS. Both variants are highly conserved, although rs147546024:A>G is an intronic variant, whereas rs1800273:G>A is a missense variant in the DMD which has a predicted damaging effect on the protein. Further gene-based analysis of DMD revealed suggestive association (P-values=0.087 and 0.074) with general cognitive ability in both cohorts. In conclusion, both single variant and gene-based analyses suggest the existence of variants in the DMD which may affect cognitive functioning in the general populations.

INTRODUCTION

The dystrophin gene (DMD) is localized on the X chromosome. Variants in DMD have been recognized as a cause of the most common form of muscular dystrophy during childhood, Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD).1 This fatal, X-linked disorder leads to progressive muscle weakness and less well-described non-progressive central nervous system (CNS) manifestations.2

A consistent finding among patients with DMD is the reduction in full-scale intelligence quotient. Although most individuals are not intellectually disabled, risk for cognitive impairment is increased among affected males and up to 30% of patients have intellectual disability.3, 4, 5 Apart from intellectual abilities, frequently reported neurocognitive function impairment has been published.6 Deficits in short-term memory, executive functions, visuospatial ability, as well as deficits in some aspect of attention, problems with narrative, linguistic and reading skills have been described, irrespective of general intelligence.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 Moreover, a higher incidence of different neuropsychiatric disorders, such as autism spectrum, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorders and social behavior problems has been revealed among affected males.13, 14, 15, 16, 17

The impact of DMD on cognitive ability in cognitively healthy populations has not been studied to the best of our knowledge; therefore, in the current study we aim to investigate whether single-nucleotide DMD variants associate with variability in cognitive functions in general populations, suggesting loci in the DMD contributing to cognition, besides genuine DMD variants.

Materials and METHODS

Study populations

Our study population consisted of subjects from Erasmus Rucphen Family (ERF) and Rotterdam Study (RS). ERF is a family-based study that includes inhabitants of a genetically isolated community in the South-West of the Netherlands, studied as part of the Genetic Research in Isolated Population (GRIP) program.18 Study population includes ~3000 individuals who are living descendants of 22 couples who had at least six children baptized in the community church. All data were collected between 2002 and 2005. The population shows minimal immigration and high inbreeding; therefore, frequency of rare alleles is increased in this population. All participants gave informed consent, and the Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus University Medical Centre approved the study.

The RS is a prospective, population study from a well-defined Ommoord district in the Rotterdam city that investigates the occurrence and determinants of diseases in the elderly.19 The cohort was initially defined in 1990 among ~7900 persons who underwent a home interview and extensive physical examination at the baseline and during follow-up rounds every 3–4 years. Cohort was extended in 2000 and 2005.19 RS is an outbred population, predominantly of Dutch origin. The Medical Ethics Committee of the Erasmus Medical Center, Rotterdam, approved the study. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection procedure

Participants from both cohorts underwent extensive neuropsychological examination. In ERF study, different cognitive domains were assessed using Dutch validated battery of neuropsychological tests.20,21 We focused on neurocognitive domains which are known to be affected in patients with DMD.8, 9, 10, 11, 12 General cognitive ability was assessed with the Dutch Adult Reading Test (DART). Memory function was measured with a word learning test from which immediate recall and learning scores were derived while executive function was assessed with the Trail Making Test (TMT) parts A and B22 and verbal fluency tests.22 Visuospatial ability was assessed with the WAIS-III block-design subtest.

In the RS, global cognitive function was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination text (MMSE) test, while executive function and information processing speed were assessed with the Letter-Digit Substitution Task (LDST),23 the Word Fluency Test (WFT)24 and the abbreviated Stroop test.25 Examination was performed at baseline (MMSE) and during follow-up rounds (MMSE, LDST and WTF).

Participants from the both cohorts who had dementia or clinical stroke were excluded from the analysis as these conditions can influence neuropsychological assessment.

Genotyping/sequencing

The exomes of 1336 individuals from the ERF population were sequenced ‘in-house' at the Center for Biomics of the Cell Biology Department of the Erasmus MC, The Netherlands, using the Agilent version V4 capture kit (Agilent Technologies, Santa Clara, CA, USA) on an Illumina Hiseq2000 sequencer (Illumina, San Diego, CA, USA) using the TruSeq Version 3 protocol (Illumina). The sequence reads were aligned to the human genome build 19 (hg19) using BWA and the NARWHAL pipeline.26,27 The aligned reads were processed further using the IndelRealigner, MarkDuplicates and TableRecalibration tools from the Genome Analysis Toolkit (GATK) and Picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net). Genetic variants were called using the Unified Genotyper tool of the GATK. About 1.4 million single-nucleotide variants (SNVs) were called and after removing the low quality variants (QUAL<150) we retrieved 577 703 SNVs in 1309 individuals. Further, for prediction of the functionality of the variants, annotations were performed using the SeattleSeq database (http://snp.gs.washington.edu/SeattleSeq Annotation131).

In the RS, exomes of 1764 individuals from the RS-I population were sequenced using the Nimblegen SeqCap EZ V2 capture kit (Roche NimbleGen, Madison, WI, USA) on an Illumina Hiseq2000 sequencer and the TruSeq Version 3 protocol. The sequences reads were aligned to the hg19 using Burrows-Wheeler Aligner.27 Subsequently, the aligned reads were processed further using Picard (http://picard.sourceforge.net), SAMtools28 and GATK.29 Genetic variants were called using Unified Genotyper Tool from GATK. Samples with low concordance to genotyping array (<95%), low transition/transversion ratio (<2.3) and high heterozygote to homozygote ratio (>2.0) were removed from the data. The final data set consisted of 903 316 SNVs in 1524 individuals.

Statistical analysis

Baseline descriptive analysis was performed with SPSS version 17 (IBM, New York, NY, USA). Deviation from normality of cognitive functions was assessed by histograms and P-P plots. As the ERF study includes related individuals, all single variants in DMD were tested for association applying additive linear-mixed modeling with the ‘mmscore' function adjusting for age, sex and education in the GenABEL library of the R software.30 The ‘mmscore' function uses the relationship matrix estimated from genomic data in the linear mixed model to correct for relatedness among the samples. Additionally, for the most interesting results gender stratified analysis was also performed. As most of these cognitive tests are correlated (the Pearson correlation coefficient ranged from 0.219 to 0.670), to adjust for multiple testing we first calculated the effective number of independent tests using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix using the Matrix Spectral Decomposition (matSpDlite) software,31 finally Bonferroni correction was applied for the effective number of independent tests. The same strategy was also adopted for modeling linkage disequilibrium between the SNVs of the DMD. Considering the number of independent cognitive tests and independent variants, the significance threshold was set to 0.05/(4 independent cognitive tests × 124 independent variants)=1.00 × 10−04, whereas suggestive threshold was set to 1/(4 independent cognitive tests × 124 independent variants)=2 × 10−3. SNVs were coded 0, 1, 2 for genotypes AA, AB, BB in females, respectively, and 0, 2 for genotypes A, B in males.

Since sequencing is likely to reveal several variants that may be population specific, we also performed the gene-based Sequence Kernel Association Test (SKAT), a test specifically designed to analyze rare sequence variation in a specific gene/region.32 Assessing the joint effect of multiple variants within the gene/region, the SKAT is proposed as a more powerful approach for rare variants than a classical single variant analysis and several burden tests.32 The significance threshold for gene-wise analysis was set to 0.05/4 independent cognitive tests=0.0125, while the suggestive threshold was set to 1/4 independent test=0.25.

To assess the relationship between the SNVs outside the protein-coding regions with gene expression in the tissue, we used the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project database.33

The data were deposited in the GWAS Central database, under the accession number HGVST1824 (http://www.gwascentral.org/study/HGVST1824).

RESULTS

General characteristics of the studied populations are shown in Table 1. The mean age in ERF was 48 years and 39% of the participants were males while mean age in RS was around 68 years and 44% of the participants were males. Around 30% of participants in the ERF study had only primary education compared with around 36% subjects in the RS.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the study populations.

| ERF | RS baseline | RS follow-up | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N | 1241 | 1464 | 902 |

| Age | 47.9 (14.4) | 68.1 (9.4) | 72.0 (7.1) |

| Gender (% of males) | 39.3% | 44.3% | 44.8% |

| Education (% of only primary education) | 29.8% | 35.6% | 29.3% |

| Cognitive tests | |||

| Dutch Adult Reading Test, mean (SD) | 58.56 (20.31) | ||

| AVLT—Immediate recall, mean (SD) | 4.37 (1.69) | ||

| AVLT—Learning, mean (SD) | 33.55 (9.01) | ||

| Ratio TMT-B/TMT-A, mean (SD) | 2.68 (1.02) | ||

| Verbal fluency, mean (SD) | 61.66 (18.21) | ||

| Block-design test, mean (SD) | 8.24 (2.77) | ||

| Mini-mental state examination, mean (SD) | 27.7 (1.8) | 27.7 (2.0) | |

| Letter-Digit Substitution Task, mean (SD) | 27.0 (7.2) | ||

| Word Fluency Test, mean (SD) | 21.3 (5.5) | ||

Abbreviations: AVLT, Auditory Verbal Learning Test; ERF, Erasmus Rucphen Family; N, number of participants; RS, Rotterdam Study; TMT-A, TMT-B, Trail Making Test parts A and B.

Number of SNVs in the DMD discovered by exome sequencing was 165 in the ERF and 482 in the RS (Supplementary Table 1). Around 70% of variants in the DMD had minor allele frequency (MAF) lower than 0.05 in ERF compared with around 98% of variants in the RS.

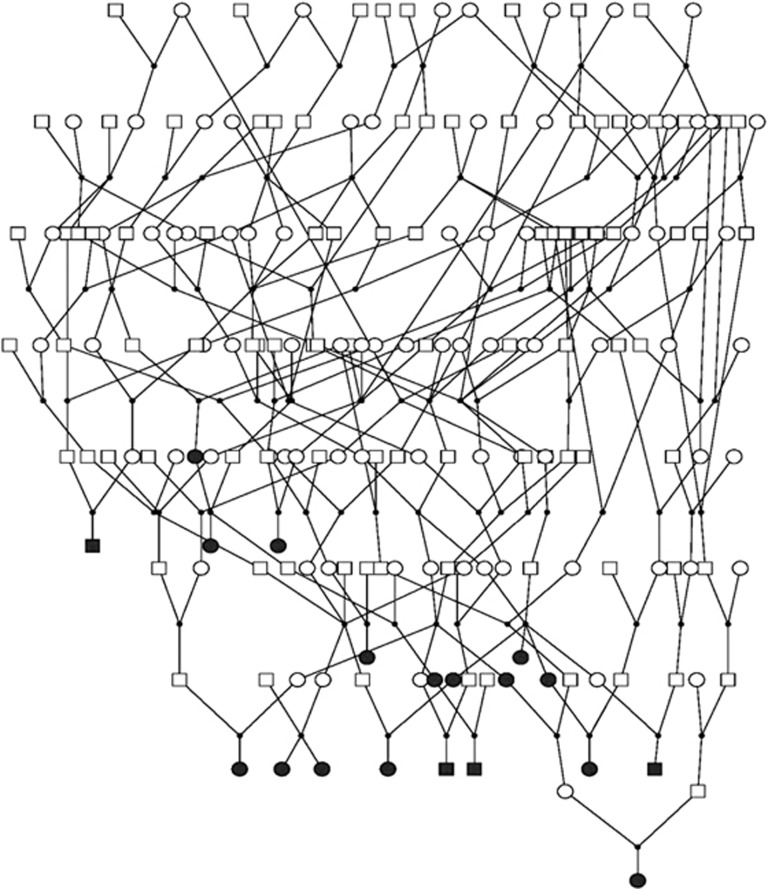

The results of the association analysis between SNVs in the DMD and cognitive functions with nominal level of significance in ERF study are presented in Table 2. Although none of the findings surpassed multiple testing correction using a Bonferroni threshold of 1.00 × 10−04, strong association was observed between rs147546024:A>G (β=1.786, P-value=2.56 × 10−04) and the block-design test. Gender stratified analysis showed nominally significant association in both genders (β=1.796, P-value=0.009 in males and β=1.623, P-value=0.018 in females). This rare (A→G) variant with MAF of 0.011 was localized in the intron 1 of the DMD (chrX.hg19:g.33146086A>G) and although being highly conserved over species (conservation score GERP=4.08) has an unknown effect on the protein. On the basis of localization, we studied the relationship of this variant with gene expression in human tissues GTEx database but no significant eQTLs were found for this variant. The family-based design of the ERF study allowed us to check whether all the carriers (n=24) of this variant were closely related. All carriers were connected to each other in 10 generations (Figure 1).

Table 2. Association of DMD variants with cognitive abilities in ERF study.

| Cognitive test | Name | Genomic positiona | Reference allele | Variant allele | N | Effect | SE | Nominal P-value | MAF | HWE P-value | PolyPhen prediction | GERP conservation score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General cognitive ability | ||||||||||||

| Dutch Adult Reading Test | rs72470515 | 32716133 | G | C | 1222 | 3.839 | 1.456 | 8.59E−03 | 0.042 | 0.392 | Unknown | 0.018 |

| rs72470514 | 32716132 | G | T | 1225 | 3.226 | 1.419 | 2.35E−02 | 0.043 | 0.392 | Unknown | −1.75 | |

| rs1800278 | 31496426 | T | C | 1225 | −3.448 | 1.528 | 2.45E−02 | 0.035 | 1 | 0.281 | 1.66 | |

| rs41305353 | 31496431 | T | A | 1225 | −3.448 | 1.528 | 2.45E−02 | 0.035 | 1 | 0.981 | 5.4 | |

| rs183429765 | 31838024 | C | T | 1225 | −9.496 | 4.213 | 2.47E−02 | 0.004 | 1 | Unknown | −1.47 | |

| rs17338590 | 31497369 | T | C | 1146 | −3.246 | 1.530 | 3.44E−02 | 0.034 | 0.006 | Unknown | −0.067 | |

| rs16989970 | 31950056 | G | A | 1215 | −3.053 | 1.460 | 3.72E−02 | 0.038 | 0.161 | Unknown | 4.25 | |

| rs17309542 | 32614065 | A | G | 1225 | −1.815 | 0.882 | 4.03E−02 | 0.124 | 0.081 | Unknown | 2.76 | |

| rs5927082 | 32591811 | A | G | 1225 | −1.639 | 0.798 | 4.07E−02 | 0.160 | 0.499 | Unknown | 2.12 | |

| rs5927083 | 32591931 | T | C | 1225 | −1.639 | 0.798 | 4.07E−02 | 0.160 | 0.499 | Unknown | −1.32 | |

| rs72468656 | 32459449 | A | G | 1221 | −8.105 | 4.089 | 4.82E−02 | 0.006 | 1 | Unknown | 3.9 | |

| rs72466537 | 31165350 | G | C | 1225 | −2.814 | 1.428 | 4.96E−02 | 0.042 | 0.105 | Unknown | 2.83 | |

| Memory | ||||||||||||

| AVLT—Immediate recall | rs1800279 | 31496398 | T | C | 1228 | 0.311 | 0.138 | 3.04E−02 | 0.035 | 0.282 | 0.01 | 2.92 |

| 23:32715801 | 32715801 | G | A | 1221 | 0.836 | 0.408 | 4.85E−02 | 0.003 | 1 | Unknown | 2.84 | |

| AVLT—Learning | 23:32715801 | 32715801 | G | A | 1221 | 6.139 | 2.015 | 2.93E−03 | 0.003 | 1 | Unknown | 2.84 |

| rs2293667 | 31224881 | A | G | 1228 | 1.161 | 0.472 | 1.62E−02 | 0.076 | 0.467 | Unknown | 1.29 | |

| rs2293668 | 31224684 | G | A | 1228 | 1.161 | 0.472 | 1.62E−02 | 0.076 | 0.467 | Unknown | 3.96 | |

| rs2293666 | 31224994 | G | A | 1194 | 1.145 | 0.468 | 1.70E−02 | 0.077 | 0.141 | Unknown | 3.65 | |

| 23:31838262 | 31838262 | A | G | 1228 | −7.458 | 3.541 | 3.97E−02 | 0.001 | 1 | Unknown | −1.35 | |

| rs1800279 | 31496398 | T | C | 1228 | 1.419 | 0.685 | 4.30E−02 | 0.035 | 0.282 | 0.01 | 2.92 | |

| Executive | ||||||||||||

| Ratio TMT-B/TMT-A | rs7891425 | 32361033 | C | T | 1223 | −0.101 | 0.048 | 3.99E−02 | 0.140 | 0.072 | Unknown | 5.36 |

| rs56094071 | 32430503 | A | T | 1202 | −0.098 | 0.048 | 4.55E−02 | 0.149 | 0.570 | Unknown | 5.15 | |

| Verbal fluency | rs72468668 | 32486917 | T | G | 1225 | 7.426 | 3.124 | 2.12E−02 | 0.007 | 1 | Unknown | 2.06 |

| rs72470511 | 32663417 | G | A | 1229 | −8.246 | 3.758 | 3.34E−02 | 0.004 | 1 | Unknown | 2.15 | |

| rs12837503 | 32404249 | A | G | 1229 | −4.038 | 1.993 | 4.95E−02 | 0.018 | 1 | Unknown | −5.13 | |

| Visuospatial | ||||||||||||

| Block-design test | rs147546024 | 33146086 | A | G | 1211 | 1.786 | 0.470 | 2.56E−04 | 0.011 | 1 | Unknown | 4.08 |

| rs72470511 | 32663417 | G | A | 1218 | −2.144 | 0.629 | 1.01E−03 | 0.004 | 1 | Unknown | 2.15 | |

| rs183429765 | 31838024 | C | T | 1220 | −1.673 | 0.650 | 1.32E−02 | 0.004 | 1 | Unknown | −1.47 | |

| 23:32834523 | 32834523 | A | G | 1220 | −2.513 | 1.043 | 2.03E−02 | 0.002 | 1 | Unknown | 0.531 | |

Abbreviations; AVLT, Auditory Verbal Learning Test; DMD, dystrophin gene; GERP, the program that generates the conservation score; HWE, Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium; MAF, minor allele frequency; N, number of individuals; SE, standard error; TMT-A, TMT-B, Trail Making Test parts A and B. The most significant finding is printed in bold.

Genomic positions are according to hg19 assembly.

Figure 1.

Carriers of the SNV that achieved the strongest association in the ERF. Carriers are indicated in black.

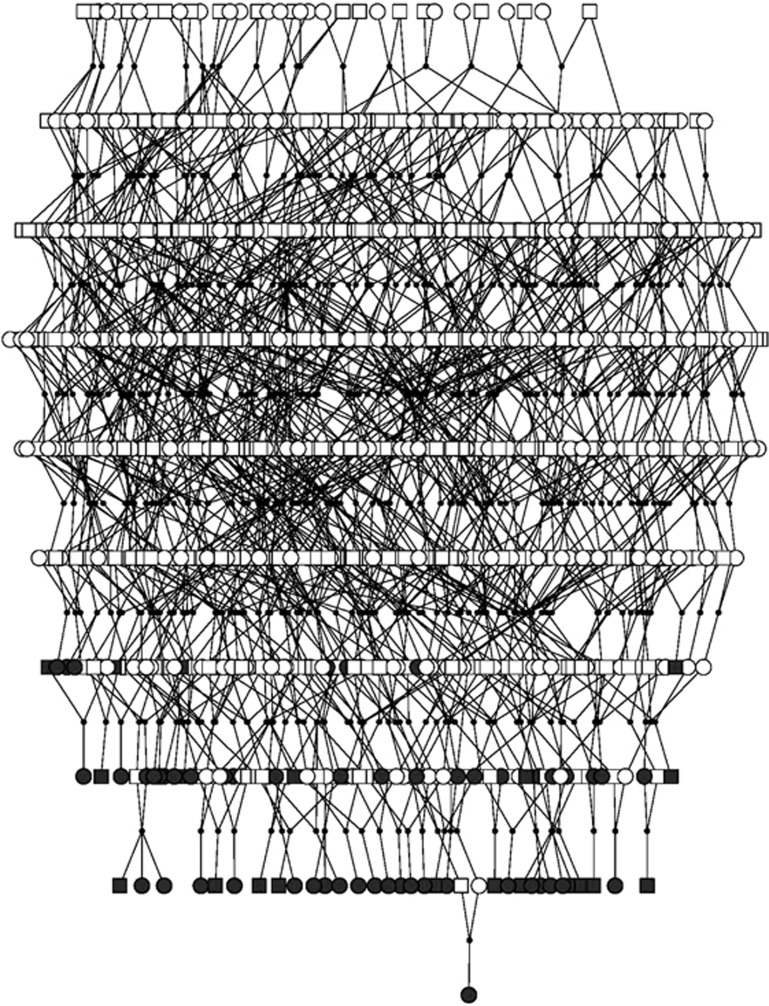

Next, we explored the association of rs147546024:A>G in the population-based study (RS). Even though rs147546024:A>G is a previously identified genetic variation in dbSNP database (present in 6 copies in 1000 Genomes with an MAF of 0.004) it was not present in RS and was not in linkage disequilibrium with any of the other SNVs of DMD. This prompted us to look for overlapping variants between the two studies. Among 34 overlapping variants we identified the most interesting overlapping finding that is shown in Table 3. Among these variants, rs1800273 (chrX.hg19:g.31986607G>A) had similar MAF in both studies (0.038 in the ERF and 0.033 in the RS), similar effect size and same direction of the effect in both cohorts and was suggestively associated with block-design test in the ERF study (β=−0.424, P-value=0.066) and with MMSE in RS (β=−0.465, P-value=0.002) (Table 3). This G→A variant is localized in exon 45 of the DMD and is classified as a missense variant with a predicted damaging effect on the protein (PolyPhen score=0.99, conservation score GERP=2.52). This variant is present in 23 copies in 1000 Genomes with an MAF of 0.014. All carriers of the variant in the ERF were connected to each other (Figure 2).

Table 3. Overlapping variant in both cohorts.

| Name | Genomic positiona | N | Reference allele | Variant allele | Effect | SE | P-value | MAF | PolyPhen prediction | GERP conservation score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ERF | |||||||||||

| Block-design test | rs1800273 | 31986607 | 1220 | G | A | −0.424 | 0.222 | 0.066 | 0.038 | 0.999 | 2.52 |

| RS | |||||||||||

| MMSE | rs1800273 | 31986607 | 1418 | G | A | −0.465 | 0.151 | 0.002 | 0.033 | 0.999 | 2.52 |

Abbreviations: ERF, Erasmus Rucphen Family; GERP, the program that generates the conservation score; MAF, minor allele frequency; MMSE, mini-mental state examination; N, number of individuals; RS, Rotterdam study; SE, standard error.

Genomic positions are according to hg19 assembly.

Figure 2.

Carriers of the overlapping SNV in the ERF. Carriers are indicated in black.

In the gene-based analysis using SKAT suggestive associations (P-values 0.087 and 0.074) were also observed both in ERF and in RS for DART and MMSE, respectively.

DISCUSSION

The aim of this study was to investigate possible impact of genetic variants in the DMD on cognitive ability in the general population. Even though none of the DMD variants surpassed the prespecified significance threshold, rs147546024:A>G was suggestively associated with block-design test in ERF, whereas rs1800273:G>A was nominally associated with MMSE test in the RS and marginally associated with block-design test in ERF.

rs147546024:A>G is localized in the intron 1196 bp far from the promoter of full-length protein isoform (Dp427p), which is expressed predominantly in the Purkinje cells of the hippocampus. The frequency of this variant in 1000 Genomes was observed to be 0.005 in individuals of European origin compared with ERF where the frequency was 0.011. This enrichment is expected due to genetic drift and isolation of the ERF population.18 Functional prediction of this variant showed high conservation score and unknown effect on the protein while gene expression analysis found no significant eQTLs in various human tissues. Interestingly, the rare allele of rs147546024:A>G was associated with better cognitive performance on block-design test which is designed to assess visuospatial ability. Similar to some studies which have described a sex difference in cognitive ability with a male advantage on the spatial domains,34 our study confirmed slight, but not significant, higher scoring of males on block-design test. It is known that better performance on block-design test is associated with autistic spectrum disorder35, 36, 37 and DMD is recognized as one of susceptibility genes for autism disorder.38,39 Suppression of the global configuration to process the information in a detailed manner, essential for this test, is described as a main characteristic of autistic patients.40, 41, 42, 43

Another biologically interesting finding while searching for overlapping variants in both studies was the missense G→A variant, rs1800273:G>A, which we found associated with block-design test in ERF and the test of global cognitive ability (MMSE) in RS. This variant was observed at a frequency of 0.033 in the individuals of European origin and absent in those of African and Asian origin. Localized in exon 45 of the DMD, this variant was classified as a missense variant with a predicted damaging effect on the protein. Since the DMD has three upstream and four intragenic promoters that control expression of full-length (Dp427c, Dp427m and Dp427p) and short protein isoforms (Dp260, Dp140, Dp116 and Dp71), exon 45 is present in the four different isoforms (Dp427c, Dp427m, Dp427p and Dp260) among which Dp427c and Dp427p are expressed in the brain.44 The Dp427c is expressed predominantly in neurons of the cortex and the CA regions of the hippocampus. It has been shown that this form of protein dystrophin colocalizes with inhibitory GABA receptor clusters at the postsynaptic membranes of hippocampal and neocortical pyramidal neurons where the synapse function is modulated.45, 46, 47, 48 According to various studies this dystrophin isoform has a stabilizing effect on the GABA receptors by limiting their lateral diffusion outside the synapse.49,50 Importance of GABA receptors for the regulation of cognition, emotion and memory is increasingly being recognized.51,52 The Dp427p is expressed in the cerebellar and hippocampal Purkinje cells and in the cortical brain.53,54 However, exon 45 does not affect three shorter DMD isoforms (Dp140, Dp116 and Dp71) which are known to be associated with cognitive function in DMD.55,56 rs1800273:G>A was detected earlier in DMD patients and is present in the Leiden Muscular dystrophy database.57 Since majority of DMD patients have cognitive impairment, the association of rs1800273:G>A with DMD may represent association with cognitive impairment. However, the presence of this variant and lack of the dystrophin protein—which can by itself lead to cognitive impairment—would make it difficult to study the separate effect of this variant in DMD patients.

One of the difficulties that our study had to deal with is heterogeneity in classification of phenotypes. Even though various cognitive tests are used in the studied populations, different cognitive domains can be compared since they are correlated. Therefore, moderate correlation (the Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.429, P-value<0.0001) between visuospatial ability and global cognition ability in the ERF, as well as correlation (the Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.460, P-value<0.0001) between visuospatial ability and executive function which is recognized as a central domain of cognitive functioning58,59 allow us to compare association of the most interesting overlapping variant with block-design test in the ERF and MMSE test in the RS.

The majority of variants called in our study were rare variants. Even though there is growing evidence that rare variants contribute to etiology of different complex traits, the search for rare variants is very difficult and challenging. Standard methods used to test for association with single common genetic variants are not powerful enough for the analysis of rare variants.60, 61, 62 Therefore with the available sample size, our study had limited power to detect association. This we attempted to overcome using the recently proposed gene-based analysis (SKAT) design for rare variant analysis.32 Assessing the cumulative effect of multiple variants in DMD implied only suggestive P-value for both cohorts. Still like other approaches that deal with rare variants this approach also has limitations in terms of power but suggestive P-values generated by SKAT pointed out that variants in the DMD may affect cognitive functioning in healthy populations.

In conclusion, analyzing the sequence variants in the exon of DMD in two cognitively healthy cohorts we find evidence of association of DMD with cognitive functioning in healthy individuals. Larger studies are required for confirmation.

Acknowledgments

Erasmus Rucphen Family study: The ERF study as a part of EUROSPAN (European Special Populations Research Network) was supported by European Commission FP6 STRP grant number 018947 (LSHG-CT-2006-01947) and also received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Program (FP7/2007–2013)/grant agreement HEALTH-F4-2007-201413 by the European Commission under the program ‘Quality of Life and Management of the Living Resources' of 5th Framework Program (no. QLG2-CT-2002-01254). High-throughput analysis of the ERF data was supported by joint grant from Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research and the Russian Foundation for Basic Research (NWO-RFBR 047.017.043). Exome sequencing analysis in ERF was supported by the ZonMw grant (project 91111025). We are grateful to all study participants and their relatives, general practitioners and neurologists for their contributions and to P Veraart for her help in genealogy, J Vergeer for the supervision of the laboratory work and P Snijders for his help in data collection. Dina Vojinovic is supported by the Ministry of Science of Serbia (grant number 175083). Najaf Amin is supported by the Hersenstichting Nederland (project number F2013(1)-28).

Rotterdam study: The generation and management of GWAS genotype data for the Rotterdam Study are supported by the Netherlands Organisation of Scientific Research NWO Investments (nr. 175.010.2005.011 and 911-03-012). This study is funded by the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (014-93-015; RIDE2), the Netherlands Genomics Initiative (NGI)/Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO) project nr. 050-060-810 and Netherlands Consortium for Healthy Ageing (NCHA). We thank Pascal Arp, Mila Jhamai, Marijn Verkerk, Lizbeth Herrera and Marjolein Peters for their help in creating the GWAS database, and Karol Estrada and Maksim V Struchalin for their support in creation and analysis of imputed data. The Rotterdam Study is funded by Erasmus Medical Center and Erasmus University, Rotterdam, Netherlands Organization for the Health Research and Development (ZonMw), the Research Institute for Diseases in the Elderly (RIDE), the Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the Ministry for Health, Welfare and Sports, the European Commission (DG XII), and the Municipality of Rotterdam. We are grateful to the study participants, the staff from the Rotterdam Study and the participating general practitioners and pharmacists.

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Supplementary Information accompanies this paper on European Journal of Human Genetics website (http://www.nature.com/ejhg)

Supplementary Material

References

- Hoffman EP, Brown Jr RH. Kunkel LM: Dystrophin: the protein product of the Duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 1987; 51: 919–928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson JL, Head SI, Rae C, Morley JW: Brain function in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Brain 2002; 125: 4–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cotton S, Voudouris NJ, Greenwood KM: Intelligence and Duchenne muscular dystrophy: full-scale, verbal, and performance intelligence quotients. Dev Med Child Neurol 2001; 43: 497–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emery AEH: Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Oxford University Press: Oxford; New York, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Cotton SM, Voudouris NJ, Greenwood KM: Association between intellectual functioning and age in children and young adults with Duchenne muscular dystrophy: further results from a meta-analysis. Dev Med Child Neurol 2005; 47: 257–265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sollee ND, Latham EE, Kindlon DJ, Bresnan MJ: Neuropsychological impairment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1985; 7: 486–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyrulnik SE, Fee RJ, De Vivo DC, Goldstein E, Hinton VJ: Delayed developmental language milestones in children with Duchenne's muscular dystrophy. J Pediatr 2007; 150: 474–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wicksell RK, Kihlgren M, Melin L, Eeg-Olofsson O: Specific cognitive deficits are common in children with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2004; 46: 154–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton VJ, De Vivo DC, Nereo NE, Goldstein E, Stern Y: Poor verbal working memory across intellectual level in boys with Duchenne dystrophy. Neurology 2000; 54: 2127–2132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinton VJ, Fee RJ, Goldstein EM, De Vivo DC: Verbal and memory skills in males with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Dev Med Child Neurol 2007; 49: 123–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mento G, Tarantino V, Bisiacchi PS: The neuropsychological profile of infantile Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Clin Neuropsychol 2011; 25: 1359–1377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D'Angelo MG, Lorusso ML, Civati F et al: Neurocognitive profiles in Duchenne muscular dystrophy and gene mutation site. Pediatr Neurol 2011; 45: 292–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perronnet C, Vaillend C: Dystrophins, utrophins, and associated scaffolding complexes: role in mammalian brain and implications for therapeutic strategies. J Biomed Biotechnol 2010; 2010: 849426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriksen JG, Vles JS: Neuropsychiatric disorders in males with duchenne muscular dystrophy: frequency rate of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), autism spectrum disorder, and obsessive—compulsive disorder. J Child Neurol 2008; 23: 477–481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu JY, Kuban KC, Allred E, Shapiro F, Darras BT: Association of Duchenne muscular dystrophy with autism spectrum disorder. J Child Neurol 2005; 20: 790–795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohane IS, McMurry A, Weber G et al: The co-morbidity burden of children and young adults with autism spectrum disorders. PLoS One 2012; 7: e33224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamura AMY, Kumagai T, Suzuki Y, Miura K: Various central nervous system involvements in dystrophinopathy: clinical and genetic considerations. No To Hattatsu 2008; 40: 10–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pardo LM, MacKay I, Oostra B, van Duijn CM, Aulchenko YS: The effect of genetic drift in a young genetically isolated population. Ann Hum Genet 2005; 69: 288–295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofman A, Darwish Murad S, van Duijn CM et al: The Rotterdam Study: 2014 objectives and design update. Eur J Epidemiol 2013; 28: 889–926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sleegers K, Roks G, Theuns J et al: Familial clustering and genetic risk for dementia in a genetically isolated Dutch population. Brain 2004; 127: 1641–1649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Pardo LM, Schuur M et al: The apolipoprotein E gene and its age-specific effects on cognitive function. Neurobiol Aging 2010; 31: 1831–1833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitan RM: The relation of the trail making test to organic brain damage. J Consult Psychol 1955; 19: 393–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW: Neuropsychological Assessment, 4th ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Welsh KA, Butters N, Mohs RC et al: The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part V. A normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology 1994; 44: 609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golden CJ: Identification of brain disorders by the Stroop Color and Word Test. J Clin Psychol 1976; 32: 654–658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brouwer RW, van den Hout MC, Grosveld FG, van Ijcken WF: NARWHAL, a primary analysis pipeline for NGS data. Bioinformatics 2012; 28: 284–285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R: Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 1754–1760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A et al: The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009; 25: 2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKenna A, Hanna M, Banks E et al: The Genome Analysis Toolkit: a MapReduce framework for analyzing next-generation DNA sequencing data. Genome Res 2010; 20: 1297–1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aulchenko YS, Ripke S, Isaacs A, van Duijn CM: GenABEL: an R library for genome-wide association analysis. Bioinformatics 2007; 23: 1294–1296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Ji L: Adjusting multiple testing in multilocus analyses using the eigenvalues of a correlation matrix. Heredity (Edinb) 2005; 95: 221–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu MC, Lee S, Cai T, Li Y, Boehnke M, Lin X: Rare-variant association testing for sequencing data with the sequence kernel association test. Am J Hum Genet 2011; 89: 82–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Consortium TG: The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 2013; 45: 580–585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Voyer D, Voyer S, Bryden MP: Magnitude of sex differences in spatial abilities: a meta-analysis and consideration of critical variables. Psychol Bull 1995; 117: 250–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lord C, Rutter M, Goode S et al: Autism diagnostic observation schedule: a standardized observation of communicative and social behavior. J Autism Dev Disord 1989; 19: 185–212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caron MJ, Mottron L, Berthiaume C, Dawson M: Cognitive mechanisms, specificity and neural underpinnings of visuospatial peaks in autism. Brain 2006; 129: 1789–1802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah AFU: Why do autistic individuals show superior performance on the block design task? J Child Psychol Psychiatry 1993; 34: 1351–1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagnamenta AT, Holt R, Yusuf M et al: A family with autism and rare copy number variants disrupting the Duchenne/Becker muscular dystrophy gene DMD and TRPM3. J Neurodev Disord 2011; 3: 124–131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung RH, Ma D, Wang K et al: An X chromosome-wide association study in autism families identifies TBL1X as a novel autism spectrum disorder candidate gene in males. Mol Autism 2011; 2: 18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellicano E, Maybery M, Durkin K, Maley A: Multiple cognitive capabilities/deficits in children with an autism spectrum disorder: ‘weak' central coherence and its relationship to theory of mind and executive control. Dev Psychopathol 2006; 18: 77–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ropar D, Mitchell P: Susceptibility to illusions and performance on visuospatial tasks in individuals with autism. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2001; 42: 539–549. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rumsey JM, Hamburger SD: Neuropsychological findings in high-functioning men with infantile autism, residual state. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol 1988; 10: 201–221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Happe F, Frith U: The weak coherence account: detail-focused cognitive style in autism spectrum disorders. J Autism Dev Disord 2006; 36: 5–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muntoni F, Torelli S, Ferlini A: Dystrophin and mutations: one gene, several proteins, multiple phenotypes. Lancet Neurol 2003; 2: 731–740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lidov HG, Byers TJ, Watkins SC, Kunkel LM: Localization of dystrophin to postsynaptic regions of central nervous system cortical neurons. Nature 1990; 348: 725–728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekiguchi M, Zushida K, Yoshida M et al: A deficit of brain dystrophin impairs specific amygdala GABAergic transmission and enhances defensive behaviour in mice. Brain 2009; 132: 124–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kueh SL, Head SI, Morley JW: GABA(A) receptor expression and inhibitory post-synaptic currents in cerebellar Purkinje cells in dystrophin-deficient mdx mice. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 2008; 35: 207–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillend C, Billard JM: Facilitated CA1 hippocampal synaptic plasticity in dystrophin-deficient mice: role for GABAA receptors? Hippocampus 2002; 12: 713–717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fritschy JM, Schweizer C, Brunig I, Luscher B: Pre- and post-synaptic mechanisms regulating the clustering of type A gamma-aminobutyric acid receptors (GABAA receptors). Biochem Soc Trans 2003; 31: 889–892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Craig AM, Kang Y: Neurexin-neuroligin signaling in synapse development. Curr Opin Neurobiol 2007; 17: 43–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohler H: Role of GABAA receptors in cognition. Biochem Soc Trans 2009; 37: 1328–1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Millan MJ, Agid Y, Brune M et al: Cognitive dysfunction in psychiatric disorders: characteristics, causes and the quest for improved therapy. Nat Rev Drug Discov 2012; 11: 141–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holder E, Maeda M, Bies RD: Expression and regulation of the dystrophin Purkinje promoter in human skeletal muscle, heart, and brain. Hum Genet 1996; 97: 232–239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorecki DC, Monaco AP, Derry JM, Walker AP, Barnard EA, Barnard PJ: Expression of four alternative dystrophin transcripts in brain regions regulated by different promoters. Hum Mol Genet 1992; 1: 505–510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daoud F, Angeard N, Demerre B et al: Analysis of Dp71 contribution in the severity of mental retardation through comparison of Duchenne and Becker patients differing by mutation consequences on Dp71 expression. Hum Mol Genet 2009; 18: 3779–3794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor PJ, Betts GA, Maroulis S et al: Dystrophin gene mutation location and the risk of cognitive impairment in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. PLoS One 2010; 5: e8803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aartsma-Rus A, Van Deutekom JC, Fokkema IF, Van Ommen GJ, Den Dunnen JT: Entries in the Leiden Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutation database: an overview of mutation types and paradoxical cases that confirm the reading-frame rule. Muscle Nerve 2006; 34: 135–144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyake A, Friedman NP, Rettinger DA, Shah P, Hegarty M: How are visuospatial working memory, executive functioning, and spatial abilities related? A latent-variable analysis. J Exp Psychol 2005; 130: 532–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salthouse T: Relations between cognitive abilities and measures of executive functioning. Neuropsychology 2005; 19: 532–545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ladouceur M, Dastani Z, Aulchenko YS, Greenwood CM, Richards JB: The empirical power of rare variant association methods: results from sanger sequencing in 1998 individuals. PLoS Genet 2012; 8: e1002496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B, Leal SM: Methods for detecting associations with rare variants for common diseases: application to analysis of sequence data. Am J Hum Genet 2008; 83: 311–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madsen BE, Browning SR: A groupwise association test for rare mutations using a weighted sum statistic. PLoS Genet 2009; 5: e1000384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.