Abstract

This paper considers the potential relationship between providing care for grandchildren and retirement, among women nearing retirement age. Using 47,444 person-wave observations from the Health and Retirement Study (HRS), we find the arrival of a new grandchild is associated with a more than eight percent increase in the retirement hazard despite little overall evidence of a care/retirement interaction. We document that while family characteristics seem to be the most important factors driving the care decision, they are also important determinants of retirement. In contrast, while financial incentives such as pensions and retiree health insurance have the largest influence on retirement, the opportunity cost associated with outside income seems to have little effect on whether or not a grandmother provides care. There is little evidence of substitution between caring for grandchildren versus providing care for elderly parents or engaging in volunteer activities; grandchild care is instead taken on as an additional responsibility. Our findings suggest that policies aimed at prolonging worklife may need to consider grandchild care responsibilities as a countervailing factor while those policies focused on grandchild care may also affect elderly labor force composition.

Keywords: Aging, Grandparents/Grandparenthood, Health and Retirement Study, Labor Force Participation

I. Introduction

This paper investigates whether caring for a grandchild might influence women’s retirement decisions and conversely if women’s retirement might influence their propensity to provide care for a grandchild, especially in response to a grandchild’s birth.1 The importance of this question is underscored in a 2010 article surveying work-family research over the previous decade (Bianchi and Milkie 2010):

“The aging of the Baby Boom generation, now poised to retire in the next decade, suggests the need for increased attention to issues that surround family caregiving across households (to frail parents and adult children and grandchildren) and the intersection of this type of caregiving with changing work statuses (e.g., retirement or reduced labor force participation, a spouse’s retirement).”

Although historically the economics literature on the elderly has not focused on care work responsibilities for grandchildren (an exception is Cardia and Ng 2003), there is evidence that it is an area of growing interest (Bengsten 2001). Over at least the past three decades, the number of grandparents participating in grandchild care has been increasing – a phenomenon documented with a wide range of data sources (e.g., Fuller-Thomson et al. 1997, and Guzman 2004, using the National Survey of Families and Households; Yang and Marcotte 2007, using the Panel Study of Income Dynamics; Taylor et al. 2010, using a Pew Research Survey; Laughlin 2010, using the Survey of Income and Program Participation).2 As with caring for parents, more of the burden of caring for grandchildren falls on women (Soldo and Hill 1995), motivating our focus on grandmothers in this paper. In addition, more than 50% of grandmothers living near (i.e., not coresident) to their grandchildren under age 13 reported providing childcare assistance, with an even higher percentage (64%) of employed grandmothers reporting affirmatively (Guzman 2004). There is also evidence that grandparent care is an especially prevalent form of care for pre-school aged children (Laughlin 2010; Luo et al. 2012).

More recently, the prevalence of grandparents providing care has increased as a result of the financial crisis that began in the United States in 2007-8, generating renewed interest in the role grandparent caring plays in helping out the middle generation (Taylor et al. 2010). Early evidence of this phenomenon was documented in Jendrek (1993), who found that of grandmothers caring for grandchildren in a non-custodial relationship, over 60% cited the employment of the grandchild's parents and/or wanting to help the grandchild's parents financially as reasons for providing care.

Yet very little evidence exists regarding whether and how care responsibilities for grandchildren might affect grandmothers’ retirement. Instead, much of the literature on the interaction between care work and retirement focuses on retirement decisions in the context of caring for elderly parents or infirm spouses (Coile 2004; Gustman and Steinmeier 2004; Ilchuk 2009). For other types of care arrangements, e.g., caring for either young children or elderly parents, retirement considerations largely have been ignored. As a result, the role of grandchild care responsibilities in influencing retirement plans and decisions remains unexplored.

In fact, early literature on retirement decisions did not consider familial responsibilities at all but instead concentrated largely on economic and financial considerations such as the effects of pensions and Social Security (e.g., Gustman and Steinmeier 1986; Stock and Wise 1990), as well as individual characteristics such as health (e.g., McGarry 2004). Subsequent economic research highlighted the complexity of retirement decisions and the role that both financial and nonfinancial factors might play in influencing such decisions (see, Lumsdaine 1996 and Lumsdaine and Mitchell 1999, and references therein). In particular, it emphasized that if factors such as care work influence the retirement decision, their omission from a retirement model could result in an overestimated impact of proposed changes in the included factors (e.g., pensions, health insurance). From a policy perspective, therefore, recognizing the interplay between increasing demand for care work and retirement decisions may inform evaluations of proposed policy changes. We consider the specific example of grandchild care work in this context.

This paper aims to explore the interaction between grandchild care and retirement. In many respects, the need to provide care for grandchildren may have a different impact on the retirement decision than when spousal or dependent child caregiving is involved. For example, Pozzebon and Mitchell (1989) attribute evidence of delayed retirement among working women when their spouse is in poor health to the need to retain employer-provided health insurance coverage. Such health insurance considerations are less likely to influence the retirement decision when the care work responsibility is toward a grandchild or elderly parent (who typically would not be covered by the potential care provider’s employer-provided health insurance).

An examination of the relationship between the decision to care for a grandchild and the decision to retire can help inform our understanding of how the demographic composition of the labor force may change in the future and determine whether policies to promote later retirement may have either limited effect or unintended care work consequences. We consider the following questions in this paper using a neoclassical economic approach: (1) does caring for grandchildren influence the odds of women’s retirement and vice versa?, (2) what socioeconomic, demographic, or health factors influence these decisions?, (3) how does the birth of a grandchild affect the odds of women’s retirement and does this effect vary according to the grandmother’s age, proximity, health, or the birth order of the grandchild? A variety of additional questions (e.g., what factors influence transition probabilities of starting or stopping the provision of care) are considered in an earlier version of this paper (Lumsdaine and Vermeer 2014).

II. Data and Methods

A. Data

The Health and Retirement Study (HRS) is an ideal dataset with which to consider the care patterns of women on the verge of retirement.3 Begun in 1992, the HRS is a biennial survey of individuals who were born between 1931 and 1941 (and hence were roughly between ages 51 and 61 in 1992) and their spouses. It surveyed over 12,600 individuals and contained over 5,800 variables at its inception, with detailed information on family structure, financial assets, health, and expectations. An excellent description of the development of the HRS is provided by Juster and Suzman (1995); a more recent publication further summarizes many features of this important survey (National Institute on Aging 2007). A number of subpopulations were oversampled as part of the HRS survey design; we therefore use household sampling weights unless otherwise noted.

We construct our sample from all the women that were aged 51-61 during any of the first eight waves because this age-range coincides with the target range defined in wave 1 of the dataset, aimed at capturing the transition to retirement.

1. Sample Construction, by wave

We briefly describe the sample construction including sample size, continuation, new entrants, and attrition, for each wave. The sample is constructed by sequentially omitting observations that met the following selection criteria: (1) male, (2) outside of the target 51-61 age range in both the current and all previous waves, that is we exclude those whose age at first entry was >61 and those who in the current wave are <51, (3) missing information on family/child characteristics, (4) missing income information, (5) missing other key explanatory variables.

Table 1 details the application of these criteria for each wave. The largest sample reduction occurs as a result of the first two criteria; out of the wave 1 sample of 12,652 individuals, we drop 46.4% due to the first criterion (that the individual be female) and another 13.5% due to the second criterion (that the individual be between ages 51-61 at entry into our sample).4 Only 0.6% of the omissions are due to the other three criteria, resulting in 39.6% admissible observations (5,004 individuals). Applying these selection criteria across all waves, we use 32.1% of all observations, and delete only slightly over 1% due to missing information; 41.9% are dropped due to not being female. An additional 25.6% are dropped because they both are not within the 51-61 age range in the current wave, nor have they ever been within the 51-61 age range in any of the previous waves. Once an individual is within the 51-61 age range (i.e., once they are “admitted” into our sample), they remain in the sample.5 Attrition between waves is quite low; on average more than 91% of our admissible sample in each wave continues onto the next wave.

Table 1.

Sample Construction, by wave

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | W5 | W6 | W7 | W8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Usable sample, previous wave | 5004 | 5,070 | 5,125 | 6,005 | 6,037 | 6,065 | 7,071 | |

| - Lost since previous wave | −492 | −428 | −446 | −513 | −522 | −441 | −562 | |

| Carry over into current wave | 4,512 | 4,642 | 4,679 | 5,492 | 5,515 | 5,624 | 6,509 | |

| % retained from previous wave | 90.2% | 91.6% | 91.3% | 91.5% | 91.4% | 92.7% | 92.1% | |

| Total individuals current wave | 12,652 | 19,642 | 17,991 | 21,384 | 19,579 | 18,167 | 20,129 | 18,469 |

| - Not female | −5,868 | −8,227 | −7,479 | −8,959 | −8,112 | −7,458 | −8,350 | −7,584 |

| - Not between ages 51-61* | −1,710 | −6,189 | −5,179 | −6,228 | −5,262 | −4,458 | −4,409 | −3,537 |

| - Missing family/children information | −5 | −73 | −120 | −62 | −79 | −128 | −220 | −215 |

| - Missing income information | −53 | −78 | −84 | −127 | −83 | −53 | −64 | −58 |

| - Missing other explanatory variables | −12 | −5 | −4 | −3 | −6 | −5 | −15 | −8 |

| Final admissible sample this wave: | 5,004 | 5,070 | 5,125 | 6,005 | 6,037 | 6,065 | 7,071 | 7,067 |

| (1) Carry over from last wave | 4,512 | 4,642 | 4,679 | 5,492 | 5,515 | 5,624 | 6,509 | |

| (2) Newly added this wave | 5,004 | 558 | 483 | 1,326 | 545 | 550 | 1,447 | 558 |

| Cumulative total sample: | 5,004 | 10,074 | 15,199 | 21,204 | 27,241 | 33,306 | 40,377 | 47,444 |

Abbreviated definition. The exact definition of this criterion is that an individual “either was >61 at first entry into the survey or whose age in the current wave is <51”. Therefore, if an individual is deemed “admissible” in an earlier wave (i.e., in addition to meeting the other criteria, they have met the age 51-61 criterion in an earlier wave), they continue to be included in subsequent waves, even if they age beyond the 51-61 age range. As noted in the paper, a large proportion of the observations deleted due to this criterion are respondents that were part of the original Assets and Health Dynamics of the Oldest Old (AHEAD) survey, that sampled people born prior to 1923 and their spouses. Consistent with the HRS sampling design regarding the addition of cohorts, if a respondent is initially deemed inadmissible due to being younger than 51, she joins the analysis sample upon reaching 51.

The number of admissible women we use for each wave is highlighted in bold in the middle of the table. For example, from our initial wave 1 sample of 5,004 women (obtained by applying the five criteria specified above), 492 of these individuals were not re-interviewed in the second wave (i.e., had died or were lost to follow-up). To the remaining 4,512 (line labeled (1) in the table) were added 558 new entrants (line labeled (2) in the table) for a total wave 2 sample of 5,070 individuals. In 1998 (wave 4), the HRS was expanded to include two additional cohorts, the Children of the Depression (CODA) cohort born between 1924 and 1930, and the War Baby cohort born between 1942 and 1947. Because some members of the latter cohort fall into our sample age range of 51-61, there is a large increase in our analysis sample at wave 4. There is a similar large increase in 2004 (wave 7), when the Early Baby Boomer cohort was added to the survey. The eight waves are cumulated into a pooled sample, representing 9,367 unique women across 47,444 person-wave observations.

2. Main variables of interest

In this section, we describe the main variables of interest in our analysis.

Caring for Grandchildren

For analysis of care status, we consider those women that are caring for grandchildren (the caring “treatment” group), those that have grandchildren but are not providing care (the caring “at risk” group), and those that do not have grandchildren (the caring “control” group, i.e., those that are not yet “at risk” for care work). The HRS questions about how much time was spent caring for grandchildren changed slightly across the waves. In wave 1, the questionnaire asked whether an individual spent more than 100 hours caring for a grandchild in the past 12 months and, if the answer was yes, how many hours were spent. In wave 2, the questionnaire asked the same question but with a lower threshold of 50 hours. In waves 3 and beyond, the questionnaire asked the following question:

“Did you (or your husband/or your wife/or your partner/…/or your late husband/or your late wife/or your late partner) spend 100 or more hours in total (since Previous Wave Interview Month-Year/in the last two years) taking care of (grand or great-grandchildren/grandchildren)?”

and if the answer was yes, how many hours were spent by each person (respondent and spouse) individually. We define caring for grandchildren as responses of more than 336 hours in waves 1 and 2 and responses of more than 672 (twice 336) in later waves, in order to use data comparable to more than 336 hours per year across all waves.6 We choose a higher (than 50 or 100 hours) threshold of 336 hours per year in an attempt to distinguish potential reporting error by grandparents who may have had a grandchild visit for a two-week vacation. The sample breakdown by grandparent status and birth of grandchildren is shown in Table 2a.

Table 2a.

Grandchild status, by wave

| By wave | W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | W5 | W6 | W7 | W8 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No grandchildren | 1,141 | 1,136 | 940 | 1,263 | 1,225 | 1,181 | 1,515 | 1,408 |

| Grandmothers | 3,863 | 3,934 | 4,185 | 4,742 | 4,812 | 4,884 | 5,556 | 5,659 |

| (a) First grandchild born since last wave | 163 | 232 | 165 | 139 | 164 | 175 | 196 | |

| (b) Other grandchild born since last wave | 1,499 | 1,544 | 1,323 | 1,615 | 1,549 | 1,386 | 1,685 | |

| (c) No grandchildren born since last wave | 2,272 | 2,409 | 3,254 | 3,058 | 3,171 | 3,995 | 3,778 | |

| Cumulative, across waves | ||||||||

| No grandchildren | 1,141 | 2,277 | 3,217 | 4,480 | 5,705 | 6,886 | 8,401 | 9,809 |

| Grandchildren, no care work | 2,942 | 6,046 | 9,508 | 13,387 | 17,464 | 21,550 | 26,139 | 30,872 |

| Caring for grandchildren | 921 | 1,751 | 2,474 | 3,337 | 4,072 | 4,870 | 5,837 | 6,763 |

New Grandchild

The use of grandparents for childcare assistance is particularly high when the grandchildren are of pre-school age (Laughlin 2010). Because the age of the grandchildren is not reported in HRS, we construct a dummy variable for the arrival of a “new grandchild” as a proxy measure, equal to one if a (first or additional) grandchild has been born during the two years since the previous wave. This variable is included in our estimation to allow for the possibility that the arrival of a new grandchild may alter care work and retirement intentions, and their interaction, to a larger degree initially than as the grandchild ages. Across all waves, nearly 25% of the person-wave observations had grandchildren born during the sampling period; more than 10% of these had first-grandchildren born. On average in each wave, 1,691 women have grandchildren born and of these, 176 are new grandmothers (women who experienced the birth of their first grandchild).

Retired

For this variable, we use a RAND HRS variable, derived from the HRS employment status variable, where respondents were able to report being retired in addition to other employment statuses. The RAND variable classifies an individual as retired if this response was selected, regardless of whether other statuses, such as working, disabled, etc., were also selected. Table 2b shows the retirement status of the sample, cumulated across waves.

Table 2b.

Retirement status, by wave

| W1 | W2 | W3 | W4 | W5 | W6 | W7 | W8 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-retired | 4,642 | 9,105 | 13,260 | 17,942 | 22,421 | 26,594 | 31,416 | 35,923 |

| Retired | 362 | 969 | 1,939 | 3,262 | 4,820 | 6,712 | 8,961 | 11,521 |

| % retired | 7.2% | 9.6% | 12.8% | 15.4% | 17.7% | 20.2% | 22.2% | 24.3% |

Looking across all the waves in the sample provides an overview of the richness of our longitudinal dataset versus the baseline (wave 1) sample. Because the individuals in the first wave are 51-61, few of them are retired at baseline. The availability of subsequent waves enables us to further investigate the factors that affect the transition into retirement and in particular, how retirement plans change with the arrival of grandchildren and/or care responsibilities. For example, of the 5,004 women in wave 1, 7.2% are already retired while over the whole sample (47,444 person-wave observations), 24.3% are retired.

3. Key explanatory variables

Work Status and Job Characteristics

Six categories of employment status are included in our analysis. The variable Part-retired is a dichotomous variable equal to one if the answer to the RAND HRS question, ‘At this time do you consider yourself to be completely retired, partly retired, or not retired at all?’, is “partly retired” and zero otherwise. Similarly, Self-employed is equal to one when the response to the RAND HRS question: ‘do you work for someone else, are you self-employed, or what?’ (regarding the current main job) is “self-employed”. The other employment status variables (also dichotomous measures) are derived from the RAND HRS variable that divides the response to the question on employment status into mutually exclusive categories:

Work FT is equal to one if the respondent is working full-time, defined as working for more than 35 hours per week and more than 36 weeks per year, and zero otherwise.

Work PT is equal to one if the respondent is working part-time and zero otherwise.

Unemployed is equal to one if the respondent is unemployed and zero otherwise.

Out of LF is equal to one if the respondent is not in the labor force and zero otherwise.

We additionally include two variables designed to capture whether the individual has flexibility with respect to the hours she works. Can cut hrs is a dichotomous measure equal to one if either: (a) the answer to the question ‘Could you reduce the number of hours in your regular work schedule?’ is yes, (b) the respondent is self-employed, or (c) the respondent reports that her hours vary a lot from week to week; otherwise it is zero. Hrs/week is the average number of hours worked per week on the respondent’s main job.

Demographic Characteristics

The demographic characteristics are variables available in or constructed from the RAND HRS and are dichotomous variables equal to one if the condition is true and zero otherwise. These variables include: Black, Hispanic, and Married. The Age variable indicates the age of the respondent in years at the end of each interview, constructed by RAND as the age at the date on the end of the interview relative to the respondent birth date. The Education variable is constructed using the “highest degree” variable since it is consistently defined across all waves. Because the available level of granularity of the higher-level degrees varies across waves, we include only the following set of dichotomous measures (equal to one if the variable name is the highest degree obtained: High School (or passing a high school equivalency exam), Associate, Bachelor, Grad/Prof (equal to one if the highest level of education attained is a graduate degree, e.g., MA, MBA, PhD, MD, JD).

Income and Wealth

For the variables in this section we use the constructed income variables from the RAND HRS data. The RAND HRS dataset consists of imputations of all asset and income types using a consistent method. A detailed description of the method used is given in the RAND HRS documentation (St. Clair et al. 2010). All variables in this section are reported in nominal dollars and are transformed via logarithm to reduce the effect of large outliers. These are: Earnings (the sum of a respondent’s wage, bonus / overtime pay, commissions, tips, second job or military reserve earnings, professional practice or trade income), Family Income (the total income of the respondent and her spouse), House value (the value of the house less mortgages and home loans), and Liquid wealth (the aggregated value of all non-housing assets, e.g., checking and savings accounts, CDs, savings bonds, T-bills, stocks and bonds, minus debt).

We also include pension and annuity income as a separate variable (Pen/Ann wlth, the sum of the respondent’s income from all pensions and annuities) to capture possible differences in the likelihood of labor force exit as a result of such cash flows.

Family Characteristics

The fourth set of variables considers family arrangements. Some family characteristics, such as the number of grandchildren or the care responsibilities of the respondent, are available in the RAND enhanced fat files. However, family data in HRS that pertain to an ‘other person’ observation (such as characteristics of the respondents’ children) are not yet included in the RAND enhanced fat files for each wave and are therefore obtained from HRS directly. In addition to the overall number of living children (#children) and grandchildren (#grandchildren), we include the number of children still living at home or temporarily away at school (#live@home) and four attributes of the subset of children who themselves have children (and therefore might need help with grandchild care), specifically the number that: (a) are married (#Kids married), (b) male (#Kids male), (c) own their own home (#Kids house), and (d) work full-time (#Kids work FT). Note that these four variables are conditional on having children (i.e., they reference the parents of the grandchildren). For those women that do not have grandchildren, these variables take a value of zero, regardless of whether or not they have children.

The HRS does not separately track how near each of the grandchildren lives to the grandparent, other than through coresidence (Coresident GC).7 In order to approximate the proximity of the grandchildren, we construct the following two dichotomous measures: One < 10 miles (equal to one if at least one child -- that also has at least one child -- lives within 10 miles) and All < 10 miles (equal to one if all the children that have at least one child live within 10 miles).

Finally we have two dummy variables that measure alternative types of altruistic behavior. The variable CareParent is a dichotomous variable equal to one if a question like the following8 is answered affirmatively “How about another kind of help. Have you [or your (husband/partner)] spent 100 or more hours in the past 12 months helping your parent(s) (or stepparents) with basic personal needs like dressing, eating, and bathing?” Similarly, the dichotomous variable Volunteer is equal to one if the respondent did volunteer work totaling 100 hours or more for religious, educational, health-related or other charitable organizations, and zero otherwise.

Health

We control for health using two relatively basic measures. Health is the self-assessed health status of the respondent (on a scale of one to five, with one being the best health) while Disabled is a dichotomous variable, constructed from the question on employment status in the RAND enhanced fat files.

Spouse Variables

Because an individual’s decisions regarding care work and retirement may be influenced by (or jointly determined with) those of her spouse, we also include variables that capture spousal characteristics – whether the spouse is working full- or part-time (FulltimeSP and Parttime SP, respectively), disabled (DisabledSP), retired (RetiredSP) – constructed analogously to the respondent characteristics. Health SP is a dichotomous variable based on the self-assessed health status of the spouse (on a scale of one to five, with one being the best health), set equal to one if the self-assessed health status response is equal to four (“fair”) or five (“poor”) and zero otherwise. The original variable (with five options) is available in the RAND HRS data.

These variables are equal to zero for persons who are unmarried.

Pension and Health Insurance Variables

The final set of variables considers pension and health insurance factors that might influence attachment to one's job. In the RAND HRS dataset is a variable that shows the types of pension plans in which the respondent is included. From that, we construct three separate dichotomous measures: Have DB plan (equal to one if the respondent has only a defined benefit type of plan for her current job), Have DC plan (equal to one if the respondent has only a defined contribution type of plan for her current job), and Exp pension (equal to one if the respondent has any pension plan at all, whether a DB, DC or both, and therefore expects to receive pension benefits in the future).

Four health insurance variables are constructed from a single categorical variable in the RAND HRS dataset and are equal to one if the condition holds and zero otherwise: Emp. HI (the respondent has health insurance coverage through either her own or her spouse's employment plan), Ret. HI (the respondent has retiree health insurance coverage under any employer-provided plan, either her own or her spouse’s), Own HI (the respondent's health insurance coverage is from her own employment plan only, and Spouse HI plan (the respondent's health insurance coverage is from her spouse's employment plan only). We additionally use the HRS data to construct the Paymore variable, equal to one if the respondent will have to pay an additional premium for health insurance if she retirees. If the individual currently has health insurance coverage but does not report access to retiree coverage, the value of this variable is one.

B. Methods

The theoretical approach we take (described in more detail in Lumsdaine and Vermeer 2014) is a neoclassical economic approach, as used by Becker (1976, 1981) to characterize aspects of family behavior (e.g., fertility, divorce) as the result of economic decisions, in the context of a life-cycle framework that recognizes intertemporal tradeoffs. The life-cycle model often has been used in the economics literature in the context of retirement decisions (e.g., Gustman and Steinmeier 1986, Pozzebon and Mitchell 1989, Stock and Wise 1990) to explicitly capture the economic tradeoff between allocating more time to paid work and less time to non-paid-work activity (and as a result earning more) versus allocating less time to paid work and more time to non-paid-work activity (but having less income as a result). Early life-cycle models of retirement focused solely on financial factors as determinants of the retirement decision but more recent studies have incorporated nonpecuniary factors such as health and caring responsibilities. It is therefore an appealing model to use to consider the time and financial tradeoffs between working for pay and caring for grandchildren, yet to date it has not been used to explore this question. We follow McGarry (2006) in assuming that (in the context of providing parent care), “A potential caregiver maximizes a standard utility function by comparing the marginal value of providing an hour of care with the value of an hour spent working or enjoying leisure,” and that an altruistic care provider (in our context, a grandmother) derives utility from her own consumption of both market goods and leisure, as well as her family's (and specifically her grandchildren's) well-being. In other words, at a given point in time, an individual chooses a retirement date R which maximizes her utility, U=f[C(R), L(R), Uf(R)], where utility is a positive function of planned future consumption (C), years spent outside of paid employment (L), and family utility (Uf), all of which are functions of a variety of covariates (such as age, health status, income, etc.). The time spent outside of paid employment is divided into two forms, CG+NCG, representing the sum of time spent caring (CG) for grandchildren and time spent in any other unpaid activity (NCG, i.e., not caring for grandchildren, although it could include other forms of care). The benefit of this formulation is that it recognizes the fact that the desirability of the two unpaid categories can differ without having to specify how (i.e., whether positively or negatively) they differ. Utility is maximized subject to the budget constraint equating consumption with the present discounted value of income over the balance of the individual's life (this includes income from own earnings, social security, pensions, assets, etc.) plus the present discounted value of nonlabor income.

Following Pozzebon and Mitchell (1989), the model assumes that: (1) the employment and care work decisions of other members of the family (in our case, the individual's children and spouse) are taken as given, and (2) it is necessary to designate a planning date for computation of income projections. Due to the nature of the data, it is assumed that the planning date is the date of survey interview on which the data were collected. While this assumption is not particularly desirable (it is more standard, in dynamic models, to assume that the planning date is a fixed age or horizon for all individuals), we use it in this setting as we cannot observe the true planning date. In addition, while prospective grandparents may exert indirect influence on the fertility of their children, it is assumed that the children's fertility decisions are independent of the grandmother’s employment status and retirement decision.

We begin by documenting the relationship between care status and work and computing transition probabilities between various work/caregiving states.9 Cox proportional hazard models (Cox 1984) are used to estimate the times to retirement and caring for grandchildren, that is, in both cases we assume the rates of retirement and caring λi(t) at age t, i = retirement, caring, are given by: λi(t;X) = exp(Xβ) λ0i(t), where λ0i(t) is the baseline hazard function when (without loss of generality) X=0. In other words, the log relative hazard is linear in a set of explanatory variables, X. The baseline sample consists of the subsample of individuals who are either (a) not retired (for the retirement hazard) or (b) not caring for grandchildren (to estimate the caring hazard). This model is estimated using unweighted observations since there is a lack of consensus regarding incorporation of weights in the estimation of a Cox model when the weights are time-varying (as they are in the HRS). The Cox proportional hazard model is preferable to a probit model since it recognizes the dynamic option-value nature of the life-cycle decision (that is, by remaining in the current state, an individual retains the “option” to leave the non-care work or non-retirement states under more advantageous terms at a later age; see, for example, Stock and Wise 1990). While a joint (or a family) model of caring for grandchildren and retirement decision-making is perhaps even more desirable, it is well-known that such models are typically quite complex and hence require substantial simplifying assumptions for tractability (e.g., Cardia & Ng, 2003).

IV. Results

A. The Link Between Caring for Grandchildren and Work

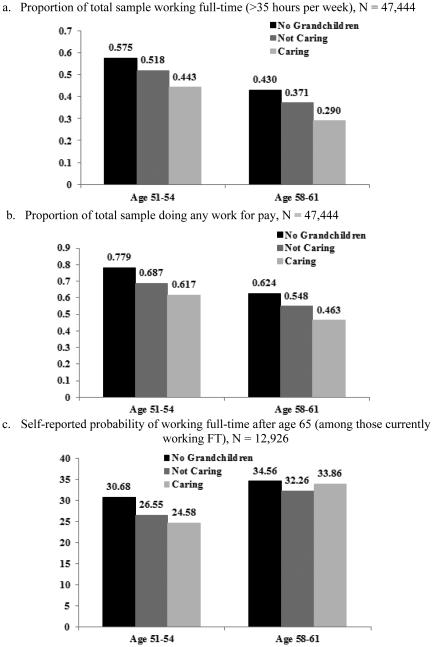

Figure 1 establishes the link between labor force participation and caring for grandchildren among women in two different age categories, separately for those without grandchildren, those with grandchildren but not providing care, and grandmothers who are caring for their grandchildren. In the top figure, the fraction of women working full-time is shown; in the middle one, the fraction working for pay. The bottom figure gives the average self-reported probability of working full-time beyond age 65, for the subsample of women that are working full-time when surveyed. Within each age group, having grandchildren and further, providing care for them, is associated both with decreased labor force attachment and lower expectations about future attachment. These differences are more pronounced at younger ages (51-54) -- those caring for grandchildren in this age group work for pay about 10% less than non-caring grandmothers and 21% less than those without grandchildren -- but they are also evident in the older age group. The divergence in labor force attachment between caring grandmothers and their non-caring counterparts is even more pronounced when considering full-time work and the older age group (58-61); among these individuals, those caring for grandchildren are nearly 22% less likely to be working full-time than non-caring grandmothers and 33% less likely to be working full-time than those without grandchildren.

Figure 1.

Female labor force attachment, by age, care status

B. Transitions

Because we retain individuals throughout all waves even when they age beyond 61, the overall sample (of 47,444 person-wave observations) consists of more than 79% grandmother observations. Using the approach taken in McGarry's (2006) paper on caring for elderly parents, rather than track the transitions of a single cohort, we stack the information for all grandmothers from all eight waves of our sample to consider transitions among the following four states: (1) working (not retired) and not caring for grandchildren, (2) caring only, (3) retired only, and (4) retired and caring. In addition to providing an elegant representation of the transitions into and out of both caring and work, the McGarry (2006) paper provides a natural comparison to our results in order to highlight potential differences between the effects of grandchild care versus parent care responsibilities; we discuss these differences at the end of this section.

Table 3 considers transitions into and out of various work/caring states from one wave (time t) to the next (time t+1) for individuals who were grandmothers at time t, so that each row of the table represents the transitions from the state in the first column to each of the four possible states (columns 2 to 5). This yields a sample of 29,053 transition observations. Not surprisingly, there is a fair amount of persistence in all four states (the diagonal of the table), with more than 67% of the sample remaining in the same state as they were in the previous wave. The persistence in caring states (the 2nd and 4th elements of the diagonal) is much lower, roughly half that in the non-caring states (the 1st and 3rd elements of the diagonal), regardless of retirement status. Further, there is evidence of substantial movement into and out of both the retirement and the caring states. While 11.6% of the sample retired between consecutive waves (the sum of the first and third rows of columns 4 and 5, divided by the total number of observations), less than half as many, 5%, “unretired”, that is, they engaged in paid work after having reported themselves as retired in the previous wave (the sum of rows five and seven, columns 2 and 3). Therefore, for at least some of the sample, there is evidence that retirement is not an absorbing state. There is similarly evidence of transitions into and out of caring for grandchildren. While 8.8% began caring between consecutive waves, another 10.2% stopped caring from one wave to the next.

Table 3.

Transitions between retirement and care work, sample of grandmothers

| Time t+1 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| Time t |

not retired /

not providing care |

caring only |

retired

only |

retired /

caring |

Total |

|

not retired / not providing

care |

|||||

| Number | 13,444 | 1,741 | 2,500 | 269 | 17,954 |

| Percent of row | 76.0 | 9.8 | 12.7 | 1.4 | 100.0 |

| caring only | |||||

| Number | 2,018 | 1,661 | 319 | 276 | 4,274 |

| Percent of row | 47.0 | 40.9 | 6.5 | 5.6 | 100.0 |

| retired only | |||||

| Number | 1,063 | 123 | 4,124 | 412 | 5,722 |

| Percent of row | 18.3 | 2.3 | 72.3 | 7.1 | 100.0 |

| retired / caring | |||||

| Number | 147 | 121 | 474 | 361 | 1,103 |

| Percent of row | 13.0 | 10.5 | 42.9 | 33.7 | 100.0 |

|

| |||||

| Total | 16,672 | 3,646 | 7,417 | 1,318 | 29,053 |

Note: Percents are weighted values, counts are unweighted.

The majority of our observations are either “not retired and not providing care” (17,954 out of the 29,053, or 61.8% of the sample, computed as the number of observations in the first row of the table divided by the total number of transitions) or “retired only” (5,722, the third row of the table, or 19.7% of the sample). While more than three-quarters (76%) of those working (not retired) and not providing care continue in this state, nearly 10% of these individuals assume caring responsibilities without leaving the labor force altogether. The remaining 14% retire, with about 10% of those retiring also beginning care work around the same time as the retirement transition (i.e., between the same waves). These proportions are consistent with McGarry’s (2006) study of caring for elderly parents. There, 78.6% of those working and not providing care continued in that state, while nearly 7% assumed care responsibilities without leaving the labor force, and 14.5% retired. The proportion of those retiring that also began providing care around the same time was similarly 10%.

C. Proportional Hazard Results

1. Caring for Grandchildren

Table 4 contains results from the estimation of the Cox proportional hazard models used to estimate non-care work and non-retirement survival, assuming the individual is currently not providing care or not retired, respectively. All independent variables in both regressions are as of the preceding wave, that is, variables in wave t-1 are used to estimate the probability that failure occurs at time t. For ease of interpretation, hazard ratios are reported; coefficient estimates and associated robust standard errors are available from the authors on request. A hazard ratio greater than one means that an individual is more likely to provide care (column 1) or retire (column 2), with higher values of that explanatory variable. Conversely, a ratio less than one implies that the individual is less likely to provide care or retire, respectively.

Table 4.

Cox Proportional Hazard Models (hazard ratios reported)

| Failure: Caring for Grandchildren N=25,497 |

Failure: Retirement N=26,621 |

|

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| (# of failures = 1,678) | (# of failures = 3,223) | |

| Caring for Grandchildren | 1.096† | |

| Retired | 1.065 | |

| New grandchild | 1.697*** | 1.085* |

| Work status and job | ||

| Part-retired | 0.946 | 1.667*** |

| Work FT | 0.875 | 1.052 |

| Work PT | 0.915 | 1.139 |

| Unemployed | 0.976 | 1.324 |

| Out of LF | 1.224 | 1.202 |

| Can cut hrs | 1.010 | 0.888** |

| Self-employed | 1.085 | 1.201* |

| Hrs/week | 1.003 | 0.995* |

| Demographics | ||

| Black | 1.298*** | 1.094† |

| Hispanic | 1.087 | 0.921 |

| Married | 1.042 | 0.975 |

| Age | 0.938*** | 1.135*** |

| High school | 1.038 | 1.101* |

| Associate | 1.300* | 1.114 |

| Bachelor | 1.049 | 1.195* |

| Grad/Prof | 0.653** | 1.355*** |

| Income and wealth | ||

| Earnings | 1.000 | 1.041*** |

| Family income | 0.986 | 0.982 |

| House value | 0.999 | 1.006 |

| Liquid wealth | 0.993† | 1.009** |

| Pen/Ann wlth | 1.013 | 1.030*** |

| Family characteristics | ||

| #children | 1.015 | 0.972* |

| #live@home | 1.000 | 0.890*** |

| #kids married | 0.992 | 0.950* |

| #kids male | 0.941* | 0.998 |

| #kids house | 0.957 | 1.055* |

| #kids work FT | 1.141*** | 0.999 |

| One < 10 miles | 1.944*** | 0.903* |

| All < 10 miles | 1.242** | 1.056 |

| #grandchildren | 0.993 | 1.014** |

| Coresident GC | 1.525*** | 1.106 |

| Altruism, Health, Spouse | ||

| Care parent | 1.152† | 1.086 |

| Volunteer | 1.118† | 1.025 |

| Health | 0.943* | 1.067*** |

| Disabled | 0.718** | 1.405*** |

| Health SP | 0.985 | 0.931 |

| Disabled SP | 1.201 | 1.213* |

| Fulltime SP | 0.954 | 0.892† |

| Parttime SP | 0.764 | 0.934 |

| Retired SP | 0.986 | 1.272*** |

| Pension/Health Insurance | ||

| Have DB plan | 0.979 | 1.262** |

| Have DC plan | 0.968 | 0.899 |

| Exp pension | 0.902 | 1.385*** |

| Emp. HI | 0.871 | 0.795* |

| Ret HI | 1.093 | 1.551*** |

| Own HI | 1.053 | 1.160 |

| Spouse HI plan | 1.228 | 1.228* |

| Paymore | 1.060 | 0.998 |

| Log Pseudo Likelihood | −13.363.1 | −25,721.2 |

Note: In order to be included in the regression, women need to be in the sample for a minimum of two consecutive waves. Independent variables are measured at time t-1 (i.e., as of the previous wave). We do not use weights in the Cox Proportional Hazard regression. If a respondent is between ages 51-61 in an earlier wave, she continues to be included in the subsequent wave, even if she ages beyond 61. Non-retired/Non-caregivers that re-enter the sample at a later time (after they drop out of the sample due to missing observations) are only included in the sample if they are still non-retired/not providing care. Robust standard errors are used to determine levels of significance; the symbols

denote significance at the .1 probability level

denote significance at the .05 probability level

denote significance at the .01 probability level

denote significance at the <0.001 probability level

There is little evidence that the propensity to provide care for grandchildren depends on retirement or any other labor force status. While those that are retired are nearly seven percent more likely to provide grandchild care than those that are not, the difference is not significant. Neither do pecuniary factors appear to influence the propensity to provide care; none of the income/wealth or pension/health insurance variables are significant.10 In contrast, the birth of a grandchild (even to those that are already grandmothers) is strongly associated with new care work responsibilities (Vandel et al. 2003, document significant variation in the types of grandparent care provided during the first three years of infancy).

Those women that have new grandchildren born are 69.7% more likely to be providing care for grandchildren two years later, relative to those that had no new grandchildren born; this increased propensity is even higher than for individuals that have coresident grandchildren (more than 52% more likely to be providing care than those who do not). Each additional year of age is associated with a more than six percent lower propensity to provide care for grandchildren, while those grandmothers that have attained the highest educational level are almost 35% less likely.

One interpretation of why the arrival of a new grandchild is associated with caring despite retirement not being a significant determinant is that grandmother caring may be more demand driven than supply driven.11 Consistent with this interpretation, the results show that family characteristics have the greatest influence on the propensity to provide care for grandchildren, even after controlling for the grandmother’s own characteristics. Each additional child that works full-time is associated with a 14% increase in the likelihood that a grandmother is caring for her grandchildren. Those who have at least one child living within a ten mile radius are nearly twice as likely (94% more) to assist with grandchild care responsibilities. In contrast, each additional male child is associated with a nearly six percent lower likelihood of caring for one’s grandchildren. There is little evidence of either altruistic complementarity or substitutability; the care hazard between those that engage in other volunteer work or care for infirmed parents or parents-in-law is only different from that of those who do not at the 10% level of significance. Those that are in worse health or those that are disabled are less likely to be care providers (about 6% and 28%, respectively).

2. Labor Force Participation

The second column of Table 4 contains results from the estimation of a Cox proportional hazard model exploring the relationship between work survival of an individual and several explanatory variables. We study the time between when a working woman first enters the sample until she retires and investigate whether caring responsibilities influence the retirement timing. The main variables of interest are the caring and grandchild variables. As with the care results, hazard ratios are reported.

Having additional grandchildren or a new grandchild born between two subsequent waves increases the probability of retirement by 1.4 percent and 8.5 percent, respectively, but having other care responsibilities (either for grandchildren or parents) does not appear to affect the probability of retirement in a significant way.12 Workers that are older, disabled or in poorer health, partly retired or self-employed, have a retired or disabled spouse or are more highly educated are more likely to retire, while those that have jobs where they are able to reduce their weekly hours or that already work fewer hours are less likely to retire. In addition to the result that caring responsibilities influence retirement timing, we find strong evidence that many family characteristics affect the likelihood of retiring. Although having more children that own their own home is associated with a 5.5 percent increase in the probability of retiring, having more children, more children living at home, more children who are married, or at least one child living nearby is associated with a significantly lower probability of retiring.

Higher earnings, liquid wealth or pension income is also significantly associated with a higher probability of retirement; even larger effects result from pension and health insurance variables, emphasizing the well-documented incentive effects associated with such variables (e.g., Gruber and Madrian 1995; Stock and Wise 1990). Individuals that expect a pension, have a defined benefit plan or have retiree health insurance obtained through their own or their spouse’s employer are between 25% and 55% more likely to retire. In addition, women that have employer-provided health insurance are more than 20% less likely to retire, a result that is consistent with the concept of “job-lock” that has been discussed extensively in the economics literature (see, e.g., Gruber and Madrian 2002 and references therein).

V. Discussion and Conclusions

This paper has considered the relationship between caring for grandchildren and the timing of women’s retirement. We find little evidence that care work is related to the opportunity cost associated with outside income. In particular, job characteristics such as being able to reduce hours or the existence of pension or health insurance benefits seem to be unrelated to the likelihood of caring for grandchildren. Instead, caring for grandchildren is strongly related to both the grandmothers’ health and disability statuses, her demographic characteristics, and the characteristics of her children. In addition, the arrival of a new grandchild greatly increases the likelihood of providing care, consistent with the literature that documents strong demand for care in the early years of a grandchild’s life. We find little evidence of substitution between caring for grandchildren and caring for elderly parents or engaging in volunteer activities.

Consistent with previous literature, our results show that some of the most important factors that affect the retirement decision are financial incentives such as pensions and retiree health insurance. This finding corroborates the results from traditional retirement models that do not include nonpecuniary factors such as unpaid care work. In addition, both poor health and disability increase the probability of retirement, as does having a disabled or retired spouse. Even controlling for these factors, however, having a new grandchild additionally increases the probability of retirement by more than eight percent, an effect similar in magnitude to the health effect. In contrast, there is little evidence that caring for parents or grandchildren directly increases the probability of retirement beyond the new grandchild effect; in both cases the results are not statistically significant at the 95% level of confidence.

There are a number of possible explanations for our finding that the arrival of a new grandchild increases the propensity to be caring and/or retired by so much. In addition to such caring providing a possible new attractive alternative to paid work, it may be indicative of a response to demand from the middle generation so that they may participate more fully in the labor market, as noted in the National Alliance for Caregiving and AARP (2009) study, and Taylor et al. (2010). Indeed we find a positive association between the number of children that are working full-time and the probability of caring for grandchildren. In addition, our finding that those who can reduce the number of hours they work are less likely to be retired indicates a desire to stay working in the face of such additional demand, consistent with results of Pavalko and Henderson (2006). This suggests that flexible work arrangements may mitigate any retirement effects that are associated with caring for grandchildren.

Our findings suggest a number of interesting policy implications. First, policies aimed at extending the years spent working (such as are being discussed in the context of shoring up the social security trust fund and addressing the challenges associated with an aging population) may have limited effect if retirement decisions are primarily driven by family considerations such as the arrival of a new grandchild or health deterioration. Second, it is possible that policies that address childcare needs of younger generations may reduce informal care demands on those of retirement age and hence keep the older generation in the workforce longer (i.e., either working until an older age or working more hours). Whether or not this is the case depends largely on whether retirement to provide caregiving is a necessity or a choice; that remains a topic for future research.

In summary, our results contribute to the literature that has examined the interaction between care work and labor force participation, by specifically examining women caring for grandchildren in the context of the retirement decision. Taken together, our findings suggest that labor force participation is the more dominant activity. When we consider transitions of retirement-age women who are both working and caring for grandchildren, we find that women are nearly eight times more likely to give up caring responsibilities than they are work responsibilities. We also find, however, that the arrival of a new grandchild, as well as a number of other family attributes, significantly affects the probability of women’s retirement, even after controlling for financial and health effects that more typically have been associated with influencing the retirement decision. Our results show that not only are family characteristics most important to the grandchild care decision, they are also important to the retirement decision.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Preliminary research for this paper was initiated while the first author was a National Fellow at the Hoover Institution, Stanford University. The collaboration for this paper is the result of a research internship at American University for the second author. Financial support for the first author from the National Institute on Aging, grant numbers R03-AG14173 and R03-AG043010, and for the second author from Stichting A.A. van Beek-Fonds, is gratefully acknowledged. We also thank Rachel Friedberg, Ed Lazear, Chris Ruhm, David Wise, and seminar participants at American University, Columbia University, Dartmouth College, Erasmus University, the Hoover Institution, the NBER Summer Institute on Aging, and the NETSPAR International Pension Workshop for helpful conversations and suggestions on this topic. We are especially grateful to Kathleen McGarry for her input and expertise on the dataset and to Mike Bader, Seth Gershenson, Alan Gustman, Elvira Sojli, Wing Wah Tham, three anonymous referees and the Editor for their very helpful comments on this paper.

Footnotes

As noted by Luo et al. (2012), “Grandchild care can take several forms.” Throughout this paper, we use the terms “care”, “caring”, “caregiving”, and “care work” interchangeably to describe the act of providing childcare assistance (including babysitting) for grandchildren, and the terms “carers”, “careworkers”, and “caregivers” for those who provide such care. We recognize that the conventions regarding the description of such contributions has changed over the past decades and do not intend for our descriptors to convey any particular preference for one versus the other. In particular in this paper they should be interpreted as equally emphasizing the value of such contributions.

Questions on grandparent caring were added to the long form of the decennial census for the first time in 2000 (Simmons and Dye 2003).

As a condition of use, we note, “The HRS (Health and Retirement Study) is sponsored by the National Institute on Aging (grant number NIA U01AG009740) and is conducted by the University of Michigan.” Where possible, we use the RAND HRS data files (St. Clair et al. 2010) for their ease of use and consistency of variables across waves. As of the initial writing of this paper, the family section variables had not been included in the RAND HRS data files but were for the most part in the associated Enhanced Fat Files. For the few explanatory variables where RAND data were not available (e.g., family variables such as children's characteristics) we merged data across waves using the raw HRS data.

While at first glance the reduction due to this second criterion seems large, it is important to remember that the current version of the HRS reflects the merging of the original (1992) HRS sample with the Assets and Health Dynamics of the Oldest Old (AHEAD) survey. The latter survey consisted of individuals born prior to 1923 (and hence were age 70+ when first surveyed in 1993), and their spouses. This population was presumed by the survey designers to be retired and hence was not asked many of the questions used in our analysis. It is also important to note that due to the longitudinal nature of the dataset, the same (over age 70) individuals are omitted in each wave to which they respond. Specifically, of 17,293 unique women in the overall sample (e.g., all individuals after application of the first criterion), 4,619 correspond to the AHEAD survey and 881 do not belong to any of the existing cohorts as a result of being too young. Of the remaining 11,793 women, 9,367 are included in our analysis sample (79.4%). For more details on the structure and sampling design of the HRS, see the online HRS documentation, available at hrsonline.osr.umich.edu/sitedocs/surveydesign.pdf and hrsonline.isr.umich.edu/sitedocs/userg.HRSSAMP.pdf.

The HRS sampling design is to add cohorts as they reach age 51. Our approach therefore corresponds to how additional cohorts are added into the HRS (see next paragraph); in particular, first spousal observations whose birth years corresponded to the new cohort are taken as members and then additional participants are recruited to round out (i.e., make representative) the new cohort.

Note that a variety of types of grandchild care are captured by this definition, including babysitting and coresidence both with and without the grandchild’s parent. Luo et al. 2012 distinguish between different types using the categories “babysitting”, “multigeneration household”, and “skipped-generation household” and document care transitions into and out of each type. As our main focus is on the interaction between caring responsibilities, however they may arise, and retirement, we employ the coarser single definition in our analysis.

There is also not a separate variable for grandchild coresidence in all waves -- therefore we construct this variable by first considering whether children live in the home and secondly whether those children have children.

This question is taken from the wave 1 (1992) questionnaire; the exact wording of the question has changed slightly over the years. For example, more recent surveys reference “since the previous interview on [date]” rather than asking about time spent in the past 12 months.

Descriptive statistics showing the bivariate relationships between all our covariates and the key variables of interest are contained in an earlier version of this paper, Lumsdaine and Vermeer (2014), Appendix A2.

Liquid wealth is significant at the 90% level of confidence, however.

Our finding is also consistent with the literature that notes especially strong demand for grandparent care when the grandchild is of pre-school age (e.g., Luo, et al. 2012). We are grateful to our anonymous referees for suggesting this interpretation.

The p-values on the caring for grandchildren and caring for parents variables are 0.052 and 0.203, respectively, so that while neither is statistically significant at the 95% level of confidence, the caring for grandchildren variable is significant at the 90% level of confidence. It is also possible that the lack of significance on the caring variable in the retirement equation reflects the censoring that occurs as a result of the new grandchild effect since when those grandmothers retire, they have reached “failure” in the Cox proportional hazard sense, meaning that their subsequent caregiving is no longer available to assist with identification of a retirement effect. To consider this possibility, we re-estimate the Cox proportional hazard model omitting the “new grandchild” variable. In this case, the p-value on the caring variable declines to 0.042; in addition, the coefficients on the other variables are qualitatively unchanged.

Contributor Information

Robin L. Lumsdaine, Kogod School of Business, American University, Washington, DC 20016-8044 National Bureau of Economic Research, 1050 Massachusetts Avenue, Cambridge, MA 02138; Network for Studies on Pensions, Aging and Retirement, Postbus 90153, 5000 LE Tilburg, The Netherlands.

Stephanie J.C. Vermeer, Roland Berger Strategy Consultants, World Trade Center, Strawinskylaan 581, 1077 XX Amsterdam, The Netherlands

References

- Becker GS. The Economic Approach to Human Behavior. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Becker GS. A Treatise on the Family. Harvard University Press; Cambridge, MA: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtson VL. Beyond the Nuclear Family: The Increasing Importance of Multigenerational Bonds. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2001;63:1–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi SM, Milkie MA. Work and Family Research in the First Decade of the 21st Century. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2010;72:705–725. [Google Scholar]

- Cardia E, Ng S. Intergenerational Time Transfers and Childcare. Review of Economic Dynamics. 2003;6:431–454. [Google Scholar]

- Coile C. Retirement Incentives and Couples' Retirement Decisions [Electronic version] Topics in Economic Analysis & Policy. 2004;4(1) article 17. Available at: http://www.bepress.com/bejeap/topics/vol4/iss1/art17 Accessed 12/21/10. [Google Scholar]

- Cox DR. Regression Models and Life-Tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series B (Methodological) 1984;63:187–220. [Google Scholar]

- Fuller-Thomson E, Minkler M, Driver D. A Profile of Grandparents Raising Grandchildren in the United States. The Gerontologist. 1997;37:406–411. doi: 10.1093/geront/37.3.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Madrian BC. Health Insurance Availability and the Retirement Decision. American Economic Review. 1995;85:938–948. [Google Scholar]

- Gruber J, Madrian BC. Health Insurance, Labor Supply, and Job Mobility: A Critical Review of the Literature. National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) working paper 8817.2002. [Google Scholar]

- Gustman A, Steinmeier T. A Structural Retirement Model. Econometrica. 1986;54:555–584. [Google Scholar]

- Gustman A, Steinmeier T. Social Security, Pensions and Retirement Behavior Within the Family. Journal of Applied Econometrics. 2004;19:723–738. [Google Scholar]

- Guzman L. Child Trends Research Brief Publication #2004-17. ChildTrends; Washington, DC: 2004. Grandma and Grandpa Taking Care of the Kids: Patterns of Involvement. [Google Scholar]

- Ilchuk S. Retirement Decisions of Women and Men in Response to Their Own and Spousal Health. Pardee RAND Graduate School; 2009. Unpublished PhD dissertation. [Google Scholar]

- Jendrek MP. Grandparents Who Parent Their Grandchildren: Effects on Lifestyle. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1993;55:609–621. [Google Scholar]

- Juster FT, Suzman R. An Overview of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30:S7–S56. [Google Scholar]

- Laughlin L. Current Population Reports: Household Economic Studies. U.S. Department of Commerce; Aug, 2010. Who's Minding the Kids? Child Care Arrangements: Spring 2005/Summer 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Lumsdaine RL. Factors Affecting Labor Supply Decisions and Retirement Income. In: Hanushek E, Maritato N, editors. Assessing Knowledge of Retirement Behavior. National Academy Press; Washington, DC: 1996. pp. 61–122. [Google Scholar]

- Lumsdaine RL, Mitchell OS. New Developments in the Economic Analysis of Retirement. In: Ashenfelter O, Card D, editors. Handbook of Labor Economics. Vol. 3. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 1999. pp. 3261–3307. [Google Scholar]

- Lumsdaine RL, Vermeer SJC. “Retirement Timing of Women and the Role of Care Responsibilities for Grandchildren,”. National Bureau of Economic Research working paper # 20756; 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, LaPierre TA, Hughes ME, Waite LJ. Grandparents Providing Care to Grandchildren: A Population-Based Study of Continuity and Change. Journal of Family Issues. 2012;33:1143–1167. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12438685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGarry K. Health and Retirement: Do Changes in Health Affect Retirement Expectations? Journal of Human Resources. 2004;39:624–648. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry K. Does Caregiving Affect Work? In: Wise D, Yashiro N, editors. Health Care Issues in the United States and Japan. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2006. pp. 209–228. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for Caregiving in collaboration with AARP Caregiving in the U.S. 2009. 2009 http://www.caregiving.org/data/Care_giving\_in\_the\_US\_2009\_full\_report.pdf accessed November 4, 2010.

- National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services . Growing Older in America: The Health and Retirement Study. NIH Publication; 2007. No. 07-5757. [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko EK, Henderson KA. Combining Care Work and Paid Work: Do Workplace Policies Make a Difference? Research on Aging. 2006;28(3):359–374. [Google Scholar]

- Pozzebon S, Mitchell OS. Married Women's Retirement Behavior. Journal of Population Economics, 2. 1989:39–53. doi: 10.1007/BF00599179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- St. Clair P, Blake D, Bugliari D, Chien S, Hayden O, Hurd M, Ilchuk S, Kung F-Y, Miu A, Panis C, Pantoja P, Rastegar A, Rohwedder S, Roth E, Carroll J, Zissimopoulos J. RAND HRS Data Documentation, Version J. Santa Monica; RAND Center for the Study of Aging, Labor & Population Program: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons T, Dye JL. Census 2000 Brief. U.S. Department of Commerce: 2003. Grandparents Living With Grandchildren: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Soldo BJ, Hill MS. Family Structure and Transfer Measures in the Health and Retirement Study: Background and Overview. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;63:s108–137. [Google Scholar]

- Stock JH, Wise DA. Pensions, the Option Value of Work, and Retirement. Econometrica. 1990;58:1151–1180. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P, Livingston G, Parker K, Wang W, Docketerman D. Since the Start of the Great Recession, More Children Raised by Grandparents. Pew Research Center; Washington, DC: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vandell DL, McCartney K, Owen MT, Booth C, Clarke-Stewart A. Variations in Child Care by Grandparents During the First Three Years. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2003;65:375–381. [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Marcotte DE. Golden Years? The Labor Market Effects of Caring for Grandchildren. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2007;69:1283–1296. [Google Scholar]