Abstract

Background & objectives:

Japanese encephalitis (JE) is the leading cause of viral encephalitis in Asia. The first major JE outbreak occurred in 1978 and since 1981 several outbreaks had been reported in the Cuddalore district (erstwhile South Arcot), Tamil Nadu, India. Entomological monitoring was carried out during January 2010 - March 2013, to determine the seasonal abundance and transmission dynamics of the vectors of JE virus, with emphasis on the role of Culex tritaeniorhynchus and Cx. gelidus.

Methods:

Mosquito collections were carried out fortnightly during dusk hours in three villages viz. Soundara Solapuram, Pennadam, Erappavur of Cuddalore district. Mosquitoes were collected during dusk for a period of one hour in and around the cattle sheds using oral aspirator and torch light. The collected mosquitoes were later identified and pooled to detect JE virus (JEV) infection by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA).

Results:

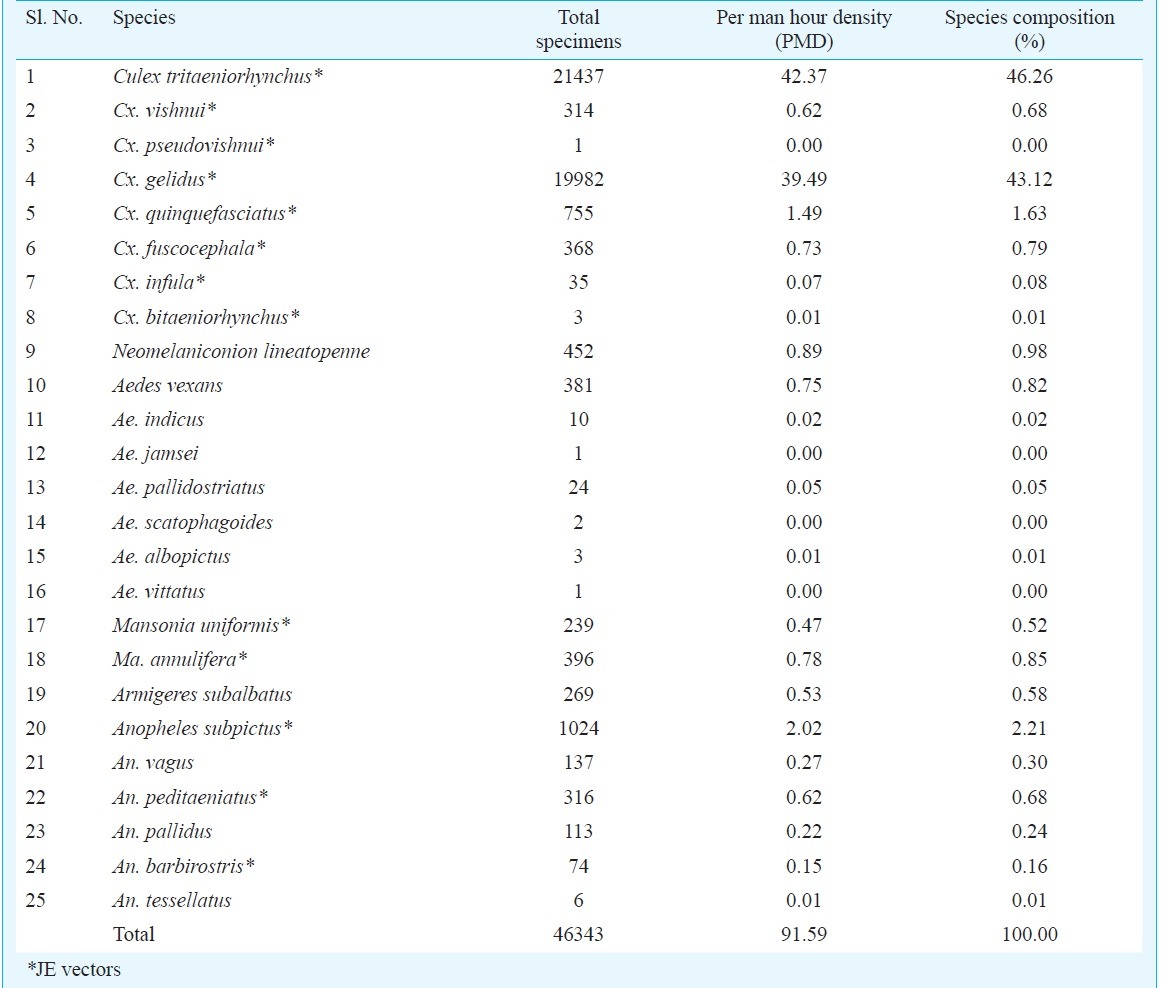

A total of 46,343 mosquitoes comprising of 25 species and six genera were collected. Species composition included viz, Cx. tritaeniorhynchus (46.26%), Cx. gelidus (43.12%) and other species (10.62%). A total of 17,678 specimens (403 pools) of Cx. gelidus and 14,358 specimens (309 pools) of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus were tested, of which 12 pools of Cx. gelidus and 14 pools of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus were positive for JE virus antigen. The climatic factors were negatively correlated with minimum infection rate (MIR) for both the species, except mean temperature (P<0.05) for Cx. gelidus.

Interpretation & conclusions:

High abundance of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus and Cx. gelidus was observed compared to other mosquito species in the study area. Detection of JEV antigen in the two species confirmed the maintenance of virus. Appropriate vector control measures need to be taken to reduce the vector abundance.

Keywords: Culex gelidus, Cuddalore district, Cx. tritaeniorhynchus, ELISA, JEV, MIR

Japanese encephalitis (JE), a mosquito-borne viral encephalitis is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality all through the world, especially in Asia with temperate and subtropical or tropical climate1 with 30,000-50,000 cases reported annually including 10,000 deaths2. The fatality rate ranges from 10 to 30 per cent and up to 50 per cent of those who recover may be left with neurological deficit3. The geographical expansion of JE virus (JEV) in Asia shows the ability of arboviruses to rapidly extend their distributions. The virus is transmitted through a zoonotic cycle between mosquitoes, pigs and water birds, such as Pond Herons (Ardeola grayi) and Little Egrets (Bubulcus ibis), which play a significant role in the JEV transmission4. Pigs are important for pre-epizootic amplification of virus, although a few epidemics have been reported in their absence. Humans and horses are incidentally infected and are the dead-end hosts of the virus, due to low level and transient viraemia5.

JE was endemic in Cuddalore district, Tamil Nadu till the end of 1991, since then the situation improved6. Apart from the primary JEV vector Culex tritaeniorhynchus, Cx. gelidus is an important secondary vector in India particularly in south East Asia7. In Cuddalore district, natural vertical transmission of JE virus in Cx. gelidus has been recorded8. This species is widespread in the oriental region including India9. The mosquito immatures are usually found in ground pools containing weed, marshy tracts, etc10. It has been reported as a voracious biter of humans, but also prefers to feed on large domestic animals11.

Cx. tritaeniorhynchus belongs to the subgenus Culex and genus Culex, which is the primary vector of JE and a member of Cx. vishnui subgroups. Cx. gelidus breed in a variety of freshwater habitats including polluted waters sometimes with considerable organic matter12. There were eight JEV isolations made from Cx. gelidus in India13. Of these, five were from Cuddalore district in Tamil Nadu and three from Mandya district in Karnataka State. The presence of the mosquito vectors of JEV, and the existence of amplifying hosts in close proximity to humans, favours virus transmission.

In this study entomological parameters were longitudinally monitored for a period of three years, with an objective to determine the seasonal abundance of JEV vectors and the virus infection status.

Material & Methods

Three villages in Cuddalore district, viz. Soundara solapuram, Erappavur and Pennadam were selected, and mosquitoes were collected fortnightly from January 2010 to March 2013. The villages were selected based on its previous history of JE outbreaks during the period 1981-2006, when there were 2870 cases with 1263 deaths, as reported by Deputy Directorate of Health Services, Cuddalore and National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme (NVBDCP), New Delhi14. The climate is characterized by a yearly range of temperature of 15 to 38°C, and has humid weather with relative humidity of >75 per cent. Summer season lasts from March to June, followed by southwest monsoon ending in September. The months of October and November constitute the main northeast monsoon season. The period from December to February is relatively cool. The Soundara Solapuram (S.S.Puram) and Pennadam are double rice crop areas, while Erappavur village is a rain fed crop area. In the three study villages, animals were tethered in close proximity to humans. The pigsties were present adjacent to human dwellings and cattle sheds.

Entomological collection: Mosquitoes were collected for one hour after sun set during dusk hours using oral aspirators and torch lights, particularly in and around the cattle sheds. The mosquitoes collected were transported alive to the laboratory of Centre for Research in Medical Entomology, Madurai. They were anaesthetized using diethyl ether, and the species identification was carried out using standard taxonomic keys and descriptions10,14,15. The relative density of female mosquitoes was estimated as the number of females collected per man hour and was denoted as PMD (per man hour density).

JE virus detection: The captured mosquitoes were segregated and pooled by species ranging from 5 to 50 per pool, and preserved at -196°C in liquid nitrogen. They were screened for JEV infectivity by enzyme linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA)16,17,18. Antigen-capture ELISA using monoclonal antibody (MAb) 6B4A10 [reactive against all viruses in Japanese encephalitis/West Nile/St Louis excephalitis/Murray Valley encephalitis (JE/WN/SLE/MVE) complex] was used as capture antibody and monoclonal antibody peroxidase conjugate SLE MAB 6B6C-1(reactive against all flaviviruses) as detector antibodies (Supplied by Dr T. F. Tsai, Centres for Disease Control and Prevention, Fort Collins Co., USA)8,19. All the Flavi virus positive samples were confirmed by Toxo IFA using JE specific MAb 112 (Supplied by Dr Kimura Kuroda, Metropolitan institute of neuroscience, Tokyo)8,20. Virus infection rate in mosquitoes was expressed as minimum infection rate (MIR) per 1,000 females tested [MIR= No. of positive pools/Total no. of mosquito specimens tested x 1000]21.

Meteorological data: The meteorological parameters like maximum and minimum temperature, rainfall, relative humidity and wind speed during the study period were collected from the Regional Research station at Vridhachalam, and the data were plotted against JE vector prevalence.

Statistical analysis was carried out to analyse multivariate analysis using SPSS 11.5 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, USA)

Results & Discussion

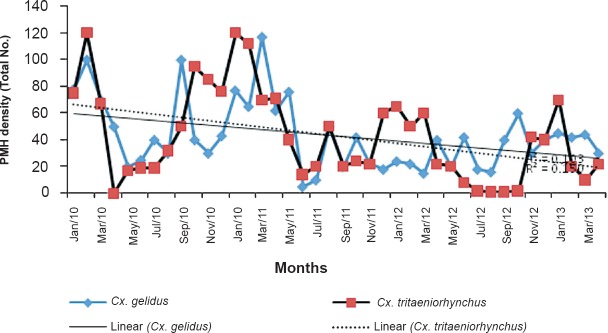

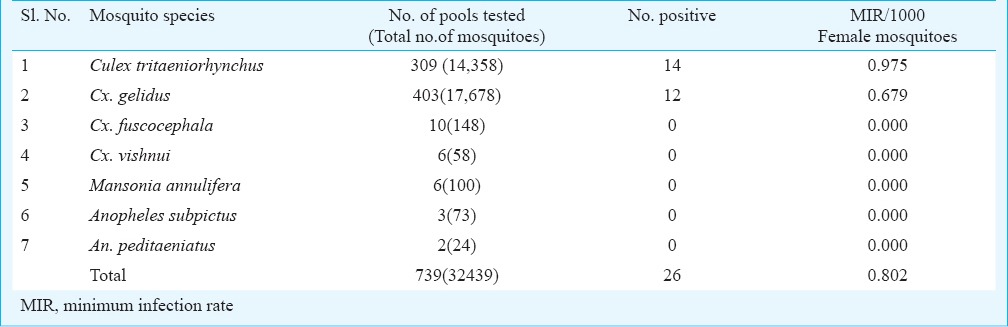

During January 2010 - March 2013, a total of 46,343 mosquitoes comprising 25 species were collected in the study area. Among Culicines, 21,437 were Cx. tritaeniorhynchus followed by Cx. gelidus (19,982), Cx. quinquefasciatus (755), Cx. fuscocephala (368), Mansonia annulifera (396), Cx. vishnui (314), Ma. uniformis (239), Cx. bitaeniorhynchus (3), Cx. pseudovishnui (1), Cx. infula (35). Among anophelines, Anopheles subpictus (1024), An. peditaeniatus (316), An. barbirostris (74) and 1399 of other anophelines were collected by spending 506 man hours. Of the total collection, Cx. tritaeniorhynchus constituted 46.26 per cent, while 43.12 per cent belonged to Cx. gelidus (Table I). The density of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus was highest during the first two years of the study (2010-2012), while in the third year, Cx. gelidus was collected in high numbers (Table I, Fig. 1).

Table I.

Mosquito fauna collection in Cuddalore district from January 2010 - March 2013

Fig. 1.

Changing scenario in the relative abundance of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus and Cx. gelidus.

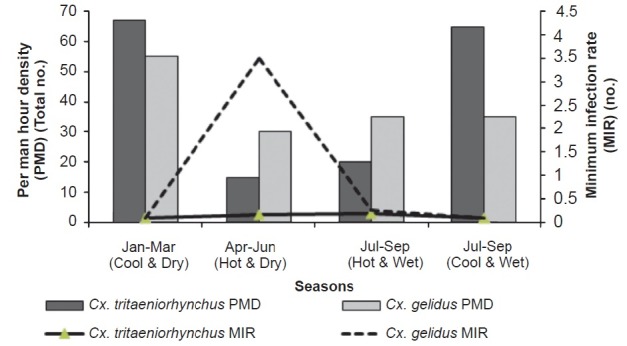

The whole year was grouped into four seasons viz.; January - March (Hot & wet), April-June (Hot & dry), July-September (Cool & dry), and October - December (Cool & wet). The abundance of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus was higher in cool and wet, and cool and dry seasons. Similarly, the abundance of Cx. gelidus was high during hot and wet, and hot and dry seasons. The MIR during hot and dry season was highest (3.185). The possibility of JEV transmission by Cx. gelidus was more during this period compared to other three seasons. The MIR of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus was 0.092 during January - March (Hot & wet) followed by 0.139 during April-June (Hot & dry), 0.184 in July-September (Cool & dry) and 0.081 in October - December (Cool & wet) (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Seasonal abundance of Cx. tritaeniorhychus and Cx. gelidus.

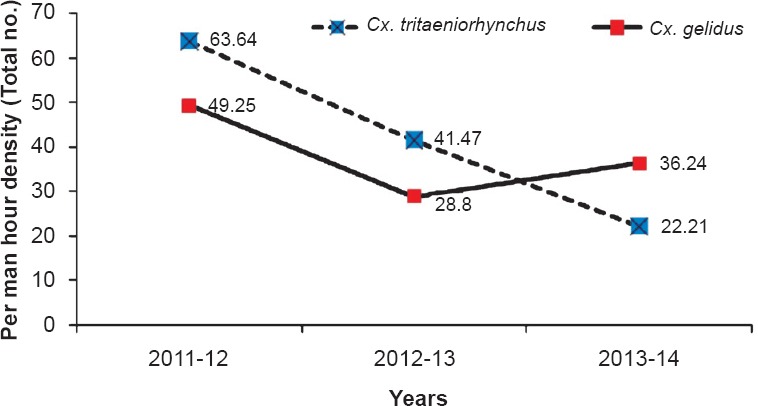

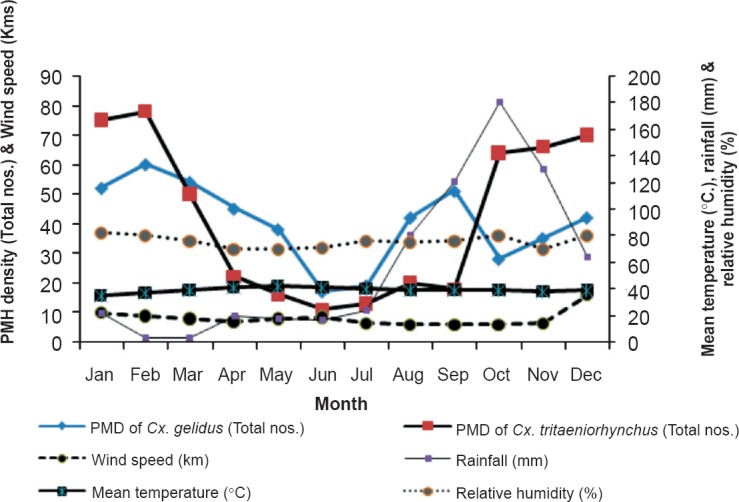

The rainfall was lower during the year 2012-2013, as compared to first two years of the study. The effect of reduced rainfall was reflected in the density of Cx. gelidus. The per man hour density of Cx. gelidus showed a declining trend. The R2 value for PMD of Cx. gelidus was found to be 0.103 and for Cx. tritaeniorhynchus it was 0.150. Generally rainfall and PMD of Cx. gelidus and Cx. tritaeniorhynchus showed negative correlation. During the period January 2010-July 2010, the per man hour density (PMD) ranged from 17.63 to 97.67 and similar trend was observed in 2011 and 2012 also. During November 2010, the rainfall was 654.90mm and PMD was 28.17. It was noted that the PMD reached a peak following one or two months of rain, i.e. from January 2010-March 2013 (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Vector abundance and linear decrease in abundance of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus and Cx. gelidus.

The average annual mean temperature showed an escalating trend of 48.81-69.22. At the same time the PMD decreased at the rate of 2 PMD per year. Monthly analysis showed that PMD of Cx. gelidus was at its minimum during the summer months of May to July. The mean temperature was negatively correlated with MIR for Cx. tritaeniorhynchus and positively correlated with MIR for Cx. gelidus (P<0.05).

In the month-wise analysis of MIR, a total of 403 pools constituting 17,678 specimens were tested and 12 pools were positive for Cx. gelidus by ELISA, which included two pools during April 2010 (MIR 8.230), one pool during February 2011 (MIR 1.616), one pool during September 2011(MIR 3.333), three pools during April 2012 (MIR 8.28), four pools during May 2012 (13.986) and one pool positive during June 2012 (MIR 3.745). The PMD of Cx. gelidus did not show any correlation with MIR. For Cx. tritaeniorhynchus, a total of 309 pools constituting 14,358 specimens were tested, of which 14 pools were found positive for JEV. The MIR of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus was highest during May 2012 (27.03) followed by September 2010 (13.33). None of the pools tested were positive for JE virus in the other suspected vectors (Table II).

Table II.

JE virus detection from Cuddalore district from January 2010 to March 2013

Minimum infection rate (MIR) with respect to Cx. gelidus ranged from 0.235 to 1.284 and varied during different seasons in the three years. The mean temperature was significant (P<0.05), while other variables viz. relative humidity, rainfall and wind speed were inversely related to MIR (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Vector abundance of Cx. tritaeniorhynchus and Cx. gelidus with meterological parameters.

Although Cx. gelidus is highly zoophagic, it may play an important role in the transmission of JEV22. The seasonal distribution of Cx. gelidus varied with time and space depending on the environmental conditions and availability of breeding habitats. Culex gelidus was more abundant during the post monsoon season (January-March) due to the availability of rain water stagnant pool, manure pits mixed with contaminated water, ground water pool. Most of the paddy fields were converted into sugarcane fields in this area due to reduced rainfall, creating puddles of polluted water in the fields, formed by the mixture of decaying sugarcane leaves and other debris. This changing pattern of cultivation could be the reason for higher abundance of Cx. gelidus recorded during the hot seasons (Apr – Sep), when the virus infection in them was also higher.

Cx. tritaeniorhynchus and Cx. gelidus were the two main mosquito species collected abundantly during the three years of the study, demonstrating their significant role in JEV transmission. During the JE season (October-December), PMD and MIR for Cx. tritaeniorhynchus were observed to be higher than Cx. gelidus. The pattern was almost similar in the subsequent season (Jan-Mar). However, in the two hot seasons (Apr-Jun and Jul-Sep), higher PMD as well as virus infectivity were observed in Cx. gelidus. Thus, the JE virus was observed to be maintained during all the seasons by these two species in this area.

It seems from the present investigation that the changes in agricultural practice and changes in the environmental conditions facilitated the proliferation of the breeding of Cx. gelidus in Cuddalore district of Tamil Nadu. Since the density of Cx. gelidus and virus infection were highest recorded during the hot dry seasons, during the July-January, paddy cultivation was done more in this region when the Cx. tritaeniorhynchus was found more abundant and JE virus infection was enhanced, it is suggested that effective vector control measures during this period would be an ideal strategy to curtail the transmission of JE virus.

Acknowledgment

The authors acknowledge the staff members of the Centre for Research in Medical Entomology, Madurai, Field Station Vridhachalam, for technical assistance in laboratory and field works.

Footnotes

Conflicts of Interest: None.

References

- 1.Sabesan S, Raju Konuganti HK, Perumal V. Spatial delimitation, forecasting and control of Japanese encephalitis: India - A case study. Open Parasitol J. 2008;2:59–63. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Konishi E, Kitai Y, Nishimura K, Harada S. Follow up survey of Japanese encephalitis virus infection in kumamoto prefecture South-West Japan: status during 2009-2011. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2012;65:448–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kari K, Liu W, Gautama K, Mammen MP, Jr, Clemens JD, Nisalak A, et al. A hospital-based surveillance for Japanese encephalitis in Bali, Indonesia. BMC Med. 2006;4:8. doi: 10.1186/1741-7015-4-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Changbunjong T, Weluwanarak T, Taowan N, Suksai P, Chamsai T, Sedwisai P. Seasonal abundance and potential of Japanese encephalitis virus infection in mosquitoes at the nesting colony of ardeid birds Thailand. Asian Pac J Trop Biomed. 2013;3:207–10. doi: 10.1016/S2221-1691(13)60051-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Misra UK, Kalita J. Overview: Japanese encephalitis. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;91:108–20. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kabilan L, Rajendran R, Arunachalam N, Ramesh S, Srinivasan S, Samuel PP, et al. Japanese encephalitis in India: an overview. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71:609–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02724120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kanojia PC. Ecological study on mosquito vectors of Japanese encephalitis virus in Bellary district, Karnataka. Indian J Med Res. 2007;126:152–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thenmozhi V, Paramasivan R, Samuel PP, Kamaraj T, Balaji T, Dhananjayan KJ, et al. Japanese encephalitis virus isolation from mosquitoes during an outbreak in 2011 in Alappuzha district, Kerala. J Vector Borne Dis. 2013;50:229–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bram RA. Contributions to the mosquito fauna of southeast Asia-II. The genus Culex in Thailand (Diptera: Culicidae) Contrib Am Entomol Inst. 1967;2:1–296. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Barraud PJ. London: Taylor and Francis; 1934. The fauna of British India including Cylon and Burma, Diptera. Vol. V. Family Culicidae. Tribes Megarhinini and Culicini; pp. 1–463. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Whelan P, Hayes G, Carter J, Wilson A, Haigh B. Detection of the exotic mosquito Culex gelidus in the Northern Territory. Commun Dis Intell. 2000;24(Suppl):74–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van den Hurk A, Ritchie SA, Montgomery B. Queensland, Austvalia: Queensland Health, Queensland Government; 1996. The mosquitoes of North Queensland: Identification and biology, includes common midges; p. 174. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gajanana A, Rajendran R, Samuel PP, Thenmozhi V, Tsai TF, Kimura-Kuroda J, et al. Japanese, encephalitis in South Arcot district, Tamil Nadu, India: a three-year longitudinal study of vector abundance and infection frequency. J Med Entomol. 1997;34:651–9. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/34.6.651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Vector Borne Disease Control Programme, Directorate General of Health Services, Ministry of Health and Family Welfare. [accessed on December 5, 2015]. Available from: www.http://nvbd.gov.in .

- 15.Sirivanakarn S. Medical Entomology Studies-III. A revision of the subgenus Culex in the Oriental region (Diptera: Culicidae) Contrib Am Entomol Inst. 1976;12:1–272. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gajanana A, Rajendran R, Thenmozhi V, Samuel PP, Tsai TF, Reuben R. Comparative evaluation of bioassay and ELISA for detection of Japanese encephalitis virus in field collected mosquitoes. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1995;26:91–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hildreth SW, Beaty BJ. Detection of eastern equine encephalomyelitis virus and highlands J virus antigens within mosquito pools by enzyme immunoassay (EIA). 1. A laboratory study. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 1984;33:965–72. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.1984.33.965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sithiprasasna R, Strickman D, Innis BL, Linthicum KJ. ELISA for detecting dengue and Japanese encephalitis viral antigen in mosquitoes. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1994;88:397–404. doi: 10.1080/00034983.1994.11812882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Arunachalam N, Murty US, Narahari D, Balasubramanian A, Samuel PP, Thenmozhi V, et al. Longitudinal studies of Japanese encephalitis virus infection in vector mosquitoes in KurnooI district, Andhra Pradesh, South India. J Med Entomol. 2009;46:633–9. doi: 10.1603/033.046.0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gajanana A, Rajendran R, Thenmozhi V, Samuel PP, Tsai TF, Reuben R. Comparative evaluation of bioassay and ELISA for detection of Japanese encephalitis virus in field collected mosquitoes. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1995;26:91–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rajendran R, Thenmozhi V, Tewari SC, Balasubramanian A, Ayanar K, Manavalan R, et al. Longitudinal studies in South Indian villages on Japanese encephalitis virus infection in mosquitoes and seroconversion in goats. Trop Med Int Health. 2003;8:174–81. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2003.01003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Geevarghese G, Mishra AC, Jacob PG, Bhat HR. Studies on the mosquito vectors of Japanese encephalitis virus in Mandya district, Karnataka, India. Southeast Asian J Trop Med Public Health. 1994;25:378–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]