Abstract

Objectives

Patients with Multiple Endocrine Neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) have mutations in the RET protooncogene and virtually all of them will develop medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC). Family members identified by genetic testing are candidates for preventive thyroidectomy. Management of the parathyroids during thyroidectomy is controversial; some experts advocate total parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation, while others recommend preserving the parathyroids in situ.

Methods

Between 1993 and 2000 we performed preventive thyroidectomies on 50 patients with MEN2A (Group A). All patients had a central neck dissection (CND) combined with total parathyroidectomy and autotransplantation of parathyroid slivers to the non-dominant forearm or to the neck. Between 2003 and the present, we performed 102 preventive thyroidectomies attempting to preserve the parathyroid glands in situ with an intact vascular pedicle (Group B). Individual parathyroids were autotransplanted only if they appeared non-viable or could not be preserved intact. Central neck dissection was done only if the serum calcitonin was greater than 40 pg/mL

Results

Permanent hypoparathyroidism occurred in 3 (6%) of 50 patients in group A, compared to 1 (1%) of 102 patients in group B (p = 0.1). Following total thyroidectomy, no patient in either group developed permanent recurrent laryngeal nerve injury, or hyperparathyroidism. Immediate postoperative serum calcitonin levels were in the normal range (<5 pg/ml) in 100 of 102 patients in group B. No patients in either group have died. Oncologic follow-up of patients in Group B is in progress.

Conclusions

In patients with MEN2A treated by preventive total thyroidectomy routine total parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation and CND gives excellent long-term results. However, preservation of the parathyroids in situ during preventive thyroidectomy combined with selective CND based on preoperative basal serum calcitonin levels is an effective and safe alternative that results in a very low incidence of hypoparathyroidism.

INTRODUCTION

In 1993, the identification of the RET oncogene as the predisposition gene for the multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 (MEN2) syndromes ushered in a new era of surgical intervention for patients with hereditary diseases.1,2 Virtually all patients with MEN2 develop medullary thyroid carcinoma (MTC) and direct DNA analysis of MEN2 family members identifies those who have inherited a mutated RET allele. Such affected family members are candidates for preventive thyroidectomy.3,4 In patients with MEN2B the MTC develops in infancy while in patients with MEN2A it usually develops in later in childhood or in young adults.

In 2005 our group published a series of 50 consecutive patients with MEN2A who were evaluated 5 or more years after preventative thyroidectomy (Group A).4 All patients were treated by total thyroidectomy, central neck dissection, (CND), and four-gland parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation of parathyroid slivers either to a muscle bed in the nondominant forearm or in the neck. The rationale for parathyroid transplantation related to the difficulty of preserving parathyroid glands during total thyroidectomy and CND. Also, many patients with MEN2A develop hyperparathyroidism and transplantation of parathyroid tissue to a distant site obviates the need for a repeat neck exploration. On postoperative evaluation 6 (12%) patients had persistent or recurrent MTC evidenced by an elevated basal or stimulated serum calcitonin level. Three (6%) patients had persistent hypoparathyroidism and required continued calcium and calcitriol replacement therapy. Since the 2005 report, it has become clear that CND is unnecessary in all cases of preventative thyroidectomy for MTC, primarily because there is a very low incidence of lymph node metastases in the central neck when the preoperative basal serum calcitonin level is less than 40 pg/mL.4-7

This report describes results in 102 patients with MEN2A or MEN2B who were treated by total thyroidectomy from 2003 to the present (Group B). Central neck dissection was not performed unless the basal preoperative serum calcitonin level was greater than 40 pg/mL. Attempts were made to preserve viable parathyroids in situ. Parathyroid tissue was only transplanted if they appeared nonviable or could not be preserved. This strategy is similar to that practiced by other groups who perform thyroidectomy for patients with MEN2.8-10

METHODS

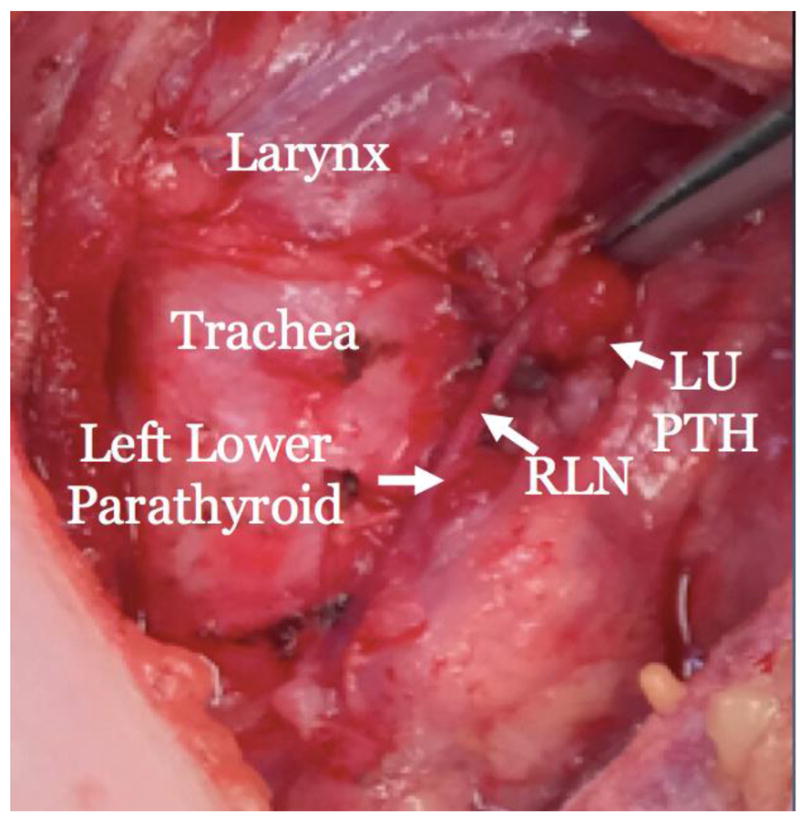

All patients in Group B had a germline RET mutation detected by direct DNA analysis that was performed prior to any interventional procedure (Table 1). The preoperative workup included determination of basal serum or plasma levels of calcitonin, metanephrines, and calcium. Calcitonin levels were measured by automated immunochemiluminometric assay manufactured by Siemens and performed on the Immulite 2000 (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN). Ultrasound of the neck was performed if the basal serum calcitonin was greater than 40 pg/mL (normal <16 pg/ml) . Ten patients in Group B had evidence of primary MTC or lymph node metastases on ultrasound. Informed consent was obtained on all patients. All thyroid tissue was removed including the posterior capsule and pyramidal lobe. All parathyroid glands were identified. The viable parathyroids were preserved in situ (Fig. 1), and those that appeared nonviable or could not be preserved were autotransplanted to a muscle bed in the sternocleidomastoid or the non-dominant forearm. Parathyroid transplants were also performed in patients with a strong family history of hyperparathyroidism and a RET mutation associated with a high incidence of hyperparathyroidism. Our group has described previously the technique of parathyroid autotransplantation.4 Central neck dissection was performed if the preoperative basal serum calcitonin was greater than 40 pg/mL. An appropriate compartment oriented dissection was performed in patients with neck metastases evident on clinical examination or on preoperative ultrasound. Postoperatively, all patients were placed on 1 gram of calcium by mouth three times a day. Patients who had multiple glands transplanted were also placed on calcitriol, 0.25 μg per day for 6 weeks. All patients were monitored with postoperative serum calcium levels and medications were adjusted accordingly. A physician evaluated each patient two weeks post operatively, and if the serum calcium level was normal the calcium supplementation was stopped. The lead author followed the patients, unless they were from a distant part of the country, in which case their local primary care physician, pediatrician or endocrinologist followed them. If long-term postoperative evaluation at Washington University was not possible the patients were followed by telephone contact.

Table 1.

Germline RET codon mutations in patients in group B.

| Codon | Patients n (%) | Median Age at Surgery (y) |

|---|---|---|

| MEN 2A | 97 (97) | |

| 609 | 48 (47) | 17 |

| 611 | 1 (1) | 6 |

| 618 | 10 (10) | 9 |

| 620 | 6 (6) | 6 |

| 634 | 15 (15) | 5 |

| 666 | 2 (2) | 6 |

| 790 | 2 (2) | 12 |

| 791 | 2 (2) | 5 |

| 804 | 9 (9) | 18 |

| 891 | 2 (2) | 35 |

| MEN 2B | 5 (5) | |

| 918 | 5 (5) | 0.5 |

Figure 1.

Operative bed of 2-1/2 year old MEN 2A patient following total thyroidectomy with removal of the posterior capsule, and parathyroid preservation. RLN-recurrent laryngeal nerve, LU PTH-Left upper parathyroid.

RESULTS

Demographics

The patients were from previously established MEN 2 families followed at Washington University, or they were referred from other parts of the country including Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Florida, Illinois, New Mexico, California, Oregon, Washington State, and Alaska.

Patient Characteristics

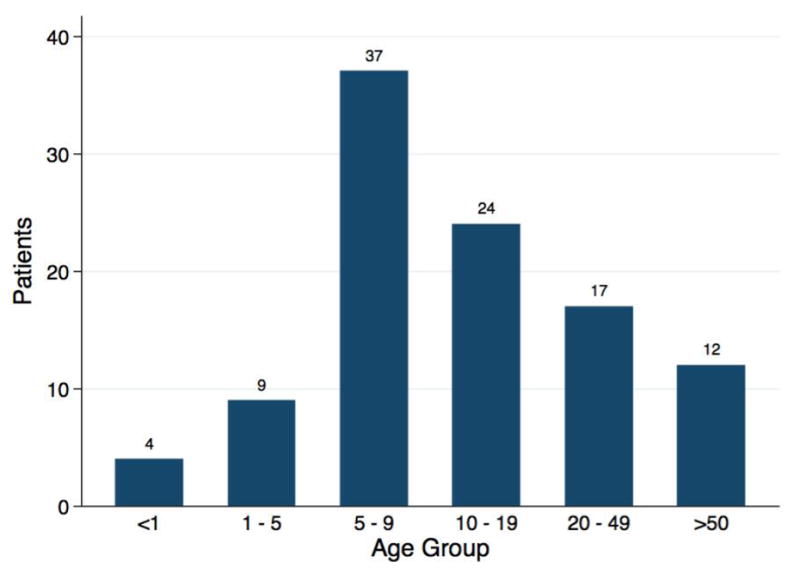

In Group B there were 44 females and 58 males ranging in age from 4 months to 81 years (median age 9 years; mean age 17.6) (Fig. 2). It is important to note that four patients were under 4 years of age and thirteen were under 5 years of age. The parathyroid glands are difficult to locate in children in this age range, and the risk of hypoparathyroidism is greater in them compared to older youngsters and adults. There were 97 patients with MEN 2A and 5 patients with MEN 2B. Germline RET mutations included heterozygous missense point mutations in codons 609, 611, 618, 620, 634, 666, 791, 804, or 918 (Fig. 3). One patient had a homozygous mutation in codon 791. Preoperative basal serum calcitonin levels ranged from undetectable to 6000 pg/mL. Prior to thyroidectomy, two patients had an adrenalectomy for pheochromocytoma. Hyperparathyroidism in two patients was treated at the time of the thyroidectomy.

Figure 2.

A Bar graph demonstrating the age distribution of patients in Group B.

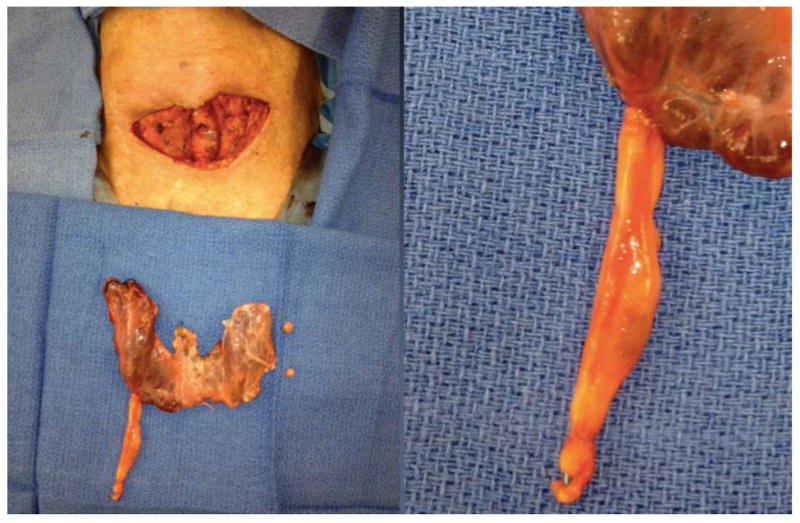

Figure 3.

Four-month-old MEN 2B patient prior to surgery, and operative specimen (right). The parathyroids were not identified in the abundant thymic and nodal tissue surrounding the thyroid. The thyroid had multifocal medullary thyroid carcinoma. The patient did not develop hypoparathyroidism after surgery.

Operations Performed

The lead author performed all total thyroidectomies, except for one each performed by WEG and TCL (Fig. 4). Central neck dissection was done if the basal serum calcitonin was greater than 40 pg/mL. Lateral neck dissection was done if patients had a serum calcitonin level greater than 200 pg/mL or evidence of lateral compartment metastases on imaging. Parathyroids were identified and if possible preserved on an intact vascular pedicle (Fig. 1). Parathyroid glands that appeared non-viable or could not be preserved were removed, placed in cold saline, minced into 1×1mm fragments, and parathyroid slivers were then transplanted into individual muscle pockets either in the sternocleidomastoid or the non-dominant forearm. In patients with hyperparathyroidism, and in 3 patients with a strong family history of hyperparathyroidism, all 4 glands were autotransplanted to a muscle pocket in the non-dominant forearm. Parathyroid transplants were grafted to the sternocleidomastoid muscle in all other cases.

Figure 4.

Photographs of thyroidectomy/parathyroidectomy specimen from an 81-year-old man with MEN2A found to have hyperparathyroidism on pre-operative workup. The right upper and lower parathyroid glands were hypercellular. The right lower gland (right) was in the thyrmus in the upper mediastinum.

In 2 infants, both MEN 2B patients ages 3 months (11 pounds) and 4 months (20 pounds), we were unable to identify parathyroid glands. This was due to the tiny size of the thyroid and parathyroids, and the presence of abundant thymic and lymph node tissue surrounding the thyroid. In both of these cases, the thyroid was removed under magnification, staying very close to the capsule and leaving all fat, thymus and nodal tissue behind. Both patients had elevated calcitonin pre-operatively and the surgeon would have liked to do a central neck dissection, but was unable to because the parathyroids were not identified. Post-operative calcitonin levels have remained undetectable (< 5 pg/ml).

All 50 patients in Group A had a total thyroidectomy with CND and four-gland parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation either to the forearm or to the sternocleidomastoid muscle. The present study is evaluation of parathyroid function following thyroidectomy in patients in Group A compared to patients in Group B. The incidence of persistent or recurrent MTC following thyroidectomy is not compared between the two groups, because of the different lengths of follow-up (5 or more years in Group A patients compared to less than 5 years in Group B patients [Table 2]) and differing methods of serum calcitonin determination (combined calcium and pentagastrin stimulation in Group A patients, compared to determination of only basal serum calcitonin levels in Group B patients).

Table 2.

Operations performed, and parathyroid management of patients in group B. TT-total thyroidectomy, CND-central neck dissection, PTH parathyroid gland.

| Patients | |

|---|---|

| n (%) | |

| Thyroidectomy (TT) only | 33/102 (32%) |

| TT, 1-4 PTH transplant | 52/102 (50%) |

| TT, CND, 1-4 PTH transplant | 17/102 (17%) |

| All PTH autotransplants: | 69/102 (66%) |

| Autograft site | |

| Forearm | 13/69 (18%) |

| SCM | 56/69 (82%) |

| Glands transplanted | |

| One | 34/69 (50%) |

| Two | 18/69 (27%) |

| Three | 6/69 (9%) |

| Four | 11/69 (15%) |

Post-operative course

Patients in Group B patients have been evaluated from 4 weeks to 12 years following thyroidectomy. Postoperative parathyroid function was assessed in all patients (Table 3). Significant temporary hypocalcemia, defined as hypocalcemia with symptoms requiring the transient administration of intravenous calcium, occurred in 3 patients, 7, 7, and 11 years of age.

Table 3.

Post-operative hypoparathyroidism in 4 patients from Group B. Three patients had temporary hypocalcemia requiring the administration of intravenous calcium. One patient has persistent hypoparathyroidism 4 years after thyroidectomy.

| Patient ID | Age (Y) | MEN/Mutation | Operation | Duration of Ca++ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Temporary Hypocalcemia (n = 3) | ||||

| 36 | 7 | MEN2A/609 | TT, LL SCM tx | 6 weeks |

| 85 | 11 | MEN2A/790 | TT, CND, 4 gland FA tx | 6 weeks |

| 99 | 7 | MEN2A/609 | TT, RU/RL/LL FA tx | 8 weeks |

| Permanent Hypocalcemia (n = 1) | ||||

| 53 | 10 | MEN2A/618 | TT | Permanent |

TT: Total thyroidectomy; LL: Left lower; RU: Right upper; RL: Right lower; SCM: sternocleidomastoid muscle; FA: forearm; CND: central neck dissection

One other patient was 10 years of age at the time of thyroidectomy and is on permanent calcium supplements for hypoparathyroidism. His growth and development are normal and he is asymptomatic even though is serum calcium level is 7.5 mg/dL on 1500 mg/day of calcium carbonate and was recently placed on calcitriol. Thus, the rate of permanent hypoparathyroidism in Group B patients is 1% (1/101), compared to 6% (2/50) in Group A patients (p = 0.1062, Fisher’s Exact test)

Two of the patients in Group B, 13 and 43 years of age, had transient unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve injury documented by laryngoscopy. In both patients the injury resolved after one month. There were no permanent recurrent nerve injuries, although postoperative laryngoscopy was done only in patients with post-operative hoarseness. Immediate post-operative basal calcitonin level was less than 5 pg/ml in 100 of 102 patients in Group B. Postoperative serum calcitonin levels were elevated in 3 patients in Group B. One patient with a 4.4 cm primary MTC and 15 of 26 positive lymph nodes had a preoperative basal serum calcitonin of 6000 pg/mL that decreased to 140 pg/mL immediately after thyroidectomy, CND, and left lateral neck dissection. In a second patient with multifocal MTC and 2 of 27 positive lymph nodes the preoperative basal serum calcitonin of 2000 pg/mL decreased to 300 pg/mL following thyroidectomy, CND, and left lateral neck dissection. In a third patient with a 0.4 cm primary MTC and 2 of 4 positive lymph nodes the preoperative basal serum calcitonin level of 147 pg/mL decreased to 77 pg/mL following thyroidectomy, CND and R lateral neck lymph node biopsy.

As of the present date, all patients in both groups are alive and asymptomatic. No patient has developed post-operative hyperparathyroidism whether the parathyroid glands were preserved or transplanted.

DISCUSSION

Hypoparathyroidism is a feared complication of thyroidectomy, as patients require calcium and calcitriol replacement therapy, and are at substantial risk for developing kidney stones and bone disease. Recently, other groups have reported rates of permanent hypoparathyroidism of 1.6% to 6.3% after thyroidectomy alone, and 1.6% to 16.2% after thyroidectomy and CND.11,12 The complication is particularly problematic in children. In infants who cannot communicate their symptoms of hypocalcemia the onset of hypocalcemia could be disastrous. In two small infants, the lead author was unable to identify any parathyroid tissue, and had to remove the thyroid without a central neck dissection, in such a way as to preserve surrounding structures by dissection on the thyroid capsule. It is extremely important that only experienced endocrine surgeons with expertise in management of the parathyroids perform these operations.

Preservation of parathyroid function during thyroidectomy in patients with MEN 2 is especially difficult because of the need to remove all thyroid tissue to prevent persistent or recurrent MTC. In Group A all patients had a total thyroidectomy and CND with 4-gland parathyroidectomy and autotransplantation regardless of the preoperative serum calcitonin level. Because of data showing that central lymph node metastases are unlikely in patients with basal calcitonin level less than 40 pg/mL, and because of the occurrence of hypoparathyroidism in 6% of children in Group A, the lead author instituted a different operative strategy. Since 2003, we attempted to preserve parathyroids in situ and transplant only those that appeared non-viable or could not be preserved during thyroidectomy. We performed CND only in patients with basal calcitonin levels greater than 40 pg/mL. This strategy has been effective in preventing hypoparathyroidism in the vast majority of patients. Recent data from Germany indicates that central neck lymph node metastases, though rare, may occur when the pre-operative basal calcitonin is between 20-40 pg/ml. The updated 2015 ATA guidelines (in press) will reflect this. It may be reasonable to consider central neck dissection in patients with basal calcitonin greater than 20 pg/ml.

The present report does not attempt to compare the incidence of persistent or recurrent MTC following thyroidectomy in patients in Groups A and patients in Group B. All patients in Group A had 5–10-year follow-up with determination of serum calcitonin levels following combined calcium and pentagastrin stimulation. Patients in Group B had a shorter period of follow-up post thyroidectomy. Also, pentagastrin is no longer available in the United States. There are several patients with elevated calcitonin levels in Group B and their follow-up is needed to assess the incidence of progressive MTC. Our results indicate that in patients with MEN2, total thyroidectomy and parathyroid preservation in situ, with selective autotransplantation, is an acceptable alternative compared to routine 4-gland parathyroidectomy with autotransplantation to the forearm or the neck. Extended follow-up and measurement of basal and stimulated calcitonin levels will be necessary to assess the incidence of persistent or recurrent MTC.

Footnotes

The authors have nothing to disclose.

References

- 1.Mulligan LM, Eng C, Healey CS, et al. Specific mutations of the RET proto-oncogene are related to disease phenotype in MEN 2A and FMTC. Nat Genet. 1994;6:70–74. doi: 10.1038/ng0194-70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Donis-Keller H, Dou S, Chi D, et al. Mutations in the RET proto-oncogene are associated with MEN 2A and FMTC. Hum Mol Genet. 1993;2:851–856. doi: 10.1093/hmg/2.7.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wells SA, Jr, Chi DD, Toshima K, et al. Predictive DNA testing and prophylactic thyroidectomy in patients at risk for multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. Ann Surg. 1994;220:237–247. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199409000-00002. discussion 247-250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Skinner MA, Moley JA, Dilley WG, et al. Prophylactic thyroidectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1105–1113. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Machens A, Niccoli-Sire P, Hoegel J, et al. European multiple endocrine neoplasia study, early malignant progression of hereditary medullary thyroid cancer. N Engl J Med. 2003;349:1517–1525. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ogilvie JB, Kebebew E. Indication and timing of thyroid surgery for patients with hereditary medullary thyroid cancer syndromes. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2006;4:139–147. doi: 10.6004/jnccn.2006.0014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Machens A, Dralle H. Biomarker-based risk stratification for previously untreated medullary thyroid cancer. J Clin Endrocrinol Metab. 2010;95:2655–2663. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-2368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lips CJ, Landsvater RM, Hoppener JW, et al. Clinical screening as compared with DNA analysis in families with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:828–835. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409293311302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Frilling A, Dralle H, Eng C, et al. Presymptomatic DNA screening in families with multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2 and familial medullary thyroid carcinoma. Surgery. 1995;118:1099–1103. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6060(05)80120-5. discussion 1103-1104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Decker RA, Geiger JD, Cox CE, et al. Prophylactic surgery for multiple endocrine neoplasia type IIa after genetic diagnosis: is parathyroid transplantation indicated? World J Surg. 1996;20:814–820. doi: 10.1007/s002689900124. discussion 820-821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shan CX, Zhang W, Jiang DZ, et al. Routine central neck dissection in differentiated thyroid carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:797–804. doi: 10.1002/lary.22162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giordano D, Valcavi R, Thompson GB, et al. Complications of central neck dissection in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma: results of a study on 1087 patients and review of the literature. Thyroid. 2012;22:911–917. doi: 10.1089/thy.2012.0011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]