Abstract

Background

Technological advances now make it feasible to administer cognitive assessments at-home on mobile and touch-screen devices such as an iPad or tablet computer. Validation of these techniques is necessary to assess their utility in clinical trials.

Objectives

We used a Computerized Cognitive Composite for Preclinical Alzheimer’s Disease (C3-PAD) developed for iPad 1) to determine the feasibility of performing the C3-PAD at home by older individuals without the presence of a trained psychometrician; 2) to explore the reliability of in-clinic compared to at-home C3-PAD performance and 3) to examine the comparability of C3-PAD performance to standardized neuropsychological tests.

Design, Setting, Participants

Forty-nine cognitively normal older individuals (mean age, 71.467.7 years; 20% non-Caucasian) were recruited from research centers at the Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Participants made two in-clinic visits one-week apart and took five 30-minute alternate versions of the C3-PAD at-home measuring episodic memory, reaction time and working memory.

Measurements

A reliability analysis explored equivalence of the six alternate C3-PAD test versions. A feasibility assessment calculated the percentage of individuals who completed all at-home tests correctly, in contrast to incomplete assessments. Correlational analyses examined the association between C3-PAD-clinic compared to C3-PAD-home assessments and between C3-PAD performance and standardized paper and pencil tests.

Results

Excellent reliability was observed among the 6 C3-PAD alternate versions (Cronbach alpha coefficient=0.93). A total of 28 of 49 participants completed all at-home sessions correctly and 48 of 49 completed four out of five correctly. There were no significant differences in participant age, sex or education between complete and incomplete at-home assessments. A single in-clinic C3-PAD assessment and the at-home C3-PAD assessments were highly associated with each other (r2=0.508, p<0.0001), suggesting that at-home tests provide reliable data as in-clinic assessments. There was also a moderate association between the at-home C3-PAD assessments and the in-clinic standardized paper and pencil tests covering similar cognitive domains (r2= 0.168, p< 0.003).

Conclusions

Reliable and valid cognitive data can be obtained from the C3-PAD assessments in the home environment. With initial in-clinic training, a high percentage of older individuals completed at-home assessments correctly. At-home cognitive testing shows promise for inclusion into clinical trial designs.

Keywords: home-based assessment, computerized assessment of cognitive function, prevention trials

INTRODUCTION

Increasing numbers of older individuals now utilize electronic devices such as smartphones and tablet computers that provide a means to record, track and transmit information about health such as physical activity, sleep, and blood pressure through downloadable applications. Given these advances, there is a potential for researchers and clinicians to record, track, and transmit information about cognitive functioning in the context of clinical trials, observational research and/or clinical care.

From a clinical and research perspective, implementation of home-based technologies would reduce the burden of in-clinic visits, particularly for more geographically remote groups. The ease of at-home administration would also allow for more automated and frequent assessments of cognitive change in the individual’s natural environment, potentially increasing the reliability of cognitive endpoints, thus yielding more sensitive measurements of change over time [1]. On-line registries might capture individuals’ health-related conditions, allow them to take cognitive screening tests and potentially provide information that may facilitate entry into clinical care or more rapid recruitment into clinical trials.

To examine feasibility, reliability and validity of unsupervised at-home cognitive assessments, we used the iPad Computerized Cognitive Composite (C3) assessment [2] that was developed for the Anti-Amyloid Treatment in Asymptomatic Alzheimer’s Disease (A4) study. This iPad battery, referred to here as the C3-PAD, was designed to include tests that would be sensitive to preclinical Alzheimer’s disease [3] and selected for this study because it is being used, on an exploratory basis, in the A4 clinical trial. The objective of this study was to examine the utility of iPad-based cognitive testing among older adults in the home environment to determine 1) the feasibility of taking cognitive tests without supervision; 2) the reliability of the test data between at-home and in-clinic assessments and 3) the comparability of at-home performance to standardized neuropsychological tests administered by a trained psychometrician.

METHODS

Participants

Forty-nine cognitively normal, older, community-dwelling subjects from the Boston area were recruited from an existing longitudinal volunteer cohort at the Massachusetts Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center (MADRC) at Massachusetts General Hospital and from the Center for Alzheimer Research and Treatment (CART) at the Brigham and Women’s Hospital. These subjects either responded positively to a questionnaire indicating an interest in participating in an iPad study or responded to advertisements for the A4 study but did not qualify based on medical exclusions. While some subjects (~12 to15 subjects) had prior experience with an iPad, subjects were not required to have computer knowledge, Internet access or prior use of an iPad to participate. All subjects underwent informed consent procedures approved by the Partners Human Research Committee, which is the Institutional Review Board for Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School. Subjects were deemed normal if they met the following inclusion criteria, 1) performed greater than a score of 31 on the Telephone Interview of Cognitive Status (TICS) [4], 2) scored above age and education-adjusted cutoffs on the Mini Mental State Exam [5, 6] 3) performed within the normal range on the 30-Minute Delayed Recall of the Logical Memory Story (LMIIa) [7] based on ADNI cut-offs (http://www.adni-info.org) and 4) were diagnosed as normal by clinicians from the MADRC and CART. Subjects were excluded if they had a history of alcoholism, drug abuse, head trauma, or current serious medical or psychiatric illness.

Subjects ranged in age from 60 to 87 years with eight subjects being age 80 or older. While the sample was highly educated (mean education = 15.8) there was a good educational range with 17 completing high school, 13 completing college and 19 with advanced degrees. The majority of the sample was Caucasian (38 of 49 subjects) but 11 subjects were African American. Sample demographics are described in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographics of sample n=49

| Mean (sd) | Range | |

|---|---|---|

| Age | 71.2 (7.6) | 60–87 |

| Education | 15.8 (2.7) | 12–20 |

| AMNART VIQ | 122.5 (8.4) | 101–132 |

| % Male | 36% | 18M/ 31F |

| % non-Caucasian | 22% | 11 African American/38 Caucasian |

AMNART VIQ= American National Adult Reading Test Verbal Intelligence Quotient

Procedures

Subjects were required to make two in-clinic visits, one week apart and to take five alternate test versions daily at home on an iPad. During the first in-clinic visit, subjects were administered standard neuropsychological tests including the American National Adult Reading Test [8], Trailmaking Test [9], Visual Form Discrimination Test [10], the Geriatric Depression Scale [11] and the Alzheimer’s Disease Cooperative Study Preclinical Alzheimer Cognitive Composite (ADCS PACC) [12] that included an alternate paragraph story [13], the Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test [14], Mini Mental State Exam [5] and Digit Symbol [15]. They also completed Version A of the C3-PAD assessment, which included two novel tests of episodic memory: the Face Name Associative Memory Exam (FNAME) [16] and the Behavioral Pattern Separation-Object Task [17], as well as four Cogstate® tests of reaction time and working memory that constitute the Cogstate Brief Battery™ [18, 19]: the Detection Task, the Identification Task, One Card Learning Task and the One-Back Task.

At the end of the first visit, subjects were taught how to use the iPad and how to select the alternate test versions of the C3-PAD battery (B through F), which are equivalent versions of the C3-PAD (i.e., utilizing the same tests but varying the test stimuli). They were also provided with an instruction manual and emergency telephone numbers should they require assistance. On days two through six (between the two in-clinic visits) participants completed one alternate test version each day at home at approximately the same time of day. On day seven, subjects returned to the clinic with the iPad, and were re-administered Version A of the C3-PAD battery.

Statistical Plan

Composite z-scores were created for each of the six subtests of the C3-PAD battery and summed together to constitute each C3-PAD alternate version. A reliability analysis [20, 21] using was performed using Cronbach’s alpha (Intraclass correlation coefficients for a two-way mixed model for consistency: ICC(3,k)) to determine the consistency between the alternate C3-PAD test versions and between the individual subtests within each version. A factor analysis was used to explore the loadings of each test version to examine equivalence. Feasibility assessment consisted of calculating the percentage of individuals who were able to complete all five at-home versions correctly (B through F), in contrast to those at-home assessments that were incomplete (i.e., missing a C3-PAD test version). Differences in age, sex and education between complete and in-complete at-home assessments were explored. An average at-home score was calculated by summing the z-scores of all assessments divided by the subjects’ number of correct completions. A sum at-home score constituted the sum of z-scores from all assessments but only in those subjects who completed all five at-home assessments correctly. A single in-clinic score consisted of the C3-PAD Version A at the baseline visit. Paired Samples T-tests and correlational analyses using linear regressions (R2) examined the association between in-clinic vs. at-home C3-PAD assessments and between the ADCS-PACC composite and the C3-PAD computerized tests.

RESULTS

Reliability Assessment

There was excellent reliability between alternate versions A through F on the composite C3-PAD tests with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of 0.93. A factor analysis of versions A through F revealed the loadings were all of similar magnitude and in the same direction which further indicates good alignment between the different test versions and no evidence that individuals performed significantly better on any one version. For each of the six individual subtests that constitute the C3-PAD across all alternate parallel versions A through F, the reliability was also good with all Cronbach alpha coefficients greater than 0.85.

Feasibility Assessment

Feasibility analysis revealed that 28 of the 49 subjects completed all five at-home sessions correctly, 48 completed four out of the five sessions correctly and all 49 subjects completed three of the five sessions correctly. There were no significant differences in age, sex, education or estimated IQ between complete and in-complete at-home assessments. Of the 20 subjects who had incomplete data, 18 had trouble selecting the appropriate test version each day. Only two subjects had trouble with the iPad itself and required additional help over the telephone.

In-Clinic and At-Home iPad Performance

Comparing subjects’ single in-clinic C3-PAD assessment (Version A, baseline) to the average at-home scores (i.e., successfully completed four or five assessments of Versions B through F), there was no significant difference in performance between environments (p=0.360) (see Figure 2A). There was also a significant association between the single in-clinic C3-PAD assessment and the initial at-home C3-PAD assessment (r2 =0.486, p<0.001) as well as with the average at-home C3-PAD scores for all successfully completed assessments (r2=0.508, p<0.001). This finding suggests that at-home testing could provide comparable results to an in-clinic C3-PAD assessment (see Figure 2B). When comparing the single in-clinic C3-PAD assessment with the sum at-home score (i.e., those individuals who successfully completed all five test versions correctly), there was also a significant association (r2=0.474, p<0.001), suggesting that incomplete assessments would provide similar information as complete assessments.

Figure 2.

A and B Pairwise comparisons between in-clinic and average at-home C3-PAD assessments were not significant suggesting at-home assessments provide comparable data as the in-clinic assessment. The single in-clinic C3-PAD assessment and the C3-PAD Average at-home assessment were strongly associated suggesting that at-home testing could provide comparable results to an in-clinic C3-PAD assessment

In-Clinic and At-Home iPad Performance and Standardized Cognitive Tests

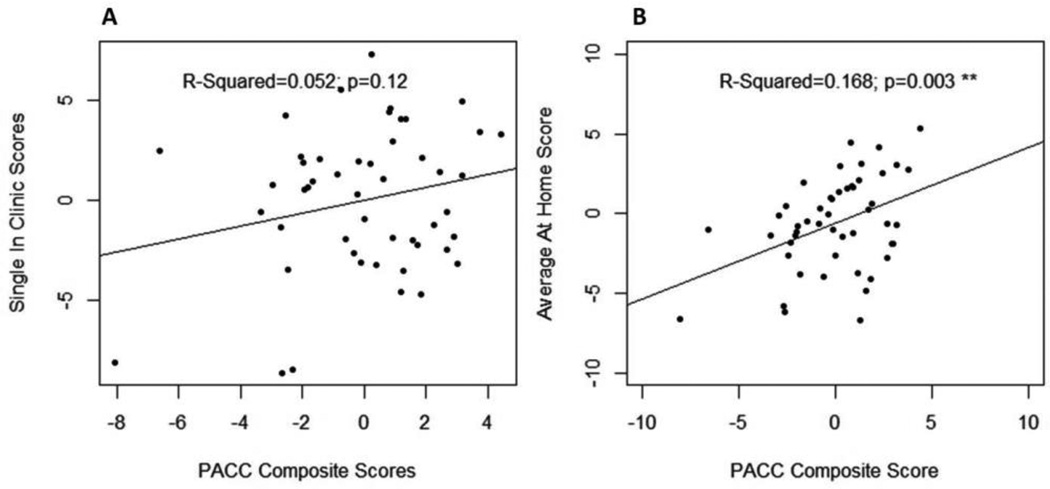

While there was only a trend association between the PACC composite and the single in-clinic C3-PAD assessment at baseline (r2=0.052, p<0.12) (See Figure 3A), the PACC composite and the average at-home assessments were moderately associated (r2=0.168, p<0.003) (See Figure 3B). A slightly stronger association occurred for those in whom all five at-home iPad assessments were completed correctly (r2=0.298, p<0.002). These findings suggest that at-home computerized assessments provide reliable data comparable to the administration of in-clinic standardized cognitive tests.

Figures 3.

A and B There was a correlational trend for a single in-clinc C3-PAD assessment and the PACC composite but a modest correlation between the PACC Composite and the Average at-home assessments suggesting that at-home computerized assessments provide comparable data to in-clinic standardized tests.

DISCUSSION

We found that reliable and valid cognitive data can be obtained from computerized cognitive assessments completed by older adults in their home environment. Data from the computerized tests collected at home compared with computerized tests collected in the clinic were highly associated, indicating that certain aspects of cognitive function can be measured reliably at home. Furthermore, performance on the computer-administered tests was also associated with performance on standardized paper and pencil tests of equivalent cognitive functions. Taken together, these data suggest that computer-administered tests taken unsupervised and at home, provide valid and reliable data about memory, attention and executive function in older adults.

These findings are consistent with a multicenter pilot study that explored the feasibility of home-based assessments in people over the age of 75 [22]. While that study employed a more antiquated computer technology compared with the iPad, the authors of the earlier study concluded that the Internet-based kiosk emerged as being more time-efficient compared with mail-in questionnaires or telephone-based systems. However, the initial implementation required more time-intensive participant training, (i.e., approximately two to three hours) compared with what was required in the current study (i.e., approximately 30 minutes) and 33% of the participants in that prior study withdrew. In our study, the iPad was easier to import into the home environment because it involved no set-up time. However, most participants required some level of training on how to operate the device and access the cognitive test application. Even with support, one person was dropped from the study, because of incomplete assessments and a reluctance to return the iPad. This experience exposes the possibility that mobile devices can be lost, broken or stolen, a factor affecting attrition and a potential additional cost that needs to be considered if implemented into clinical trials. The very low drop out rate in the current study suggests that technological advances, as well as greater levels of familiarity with computers among older adults, have increased both the usability and acceptability of in-home, computer-based assessments.

The most common error made by 20 of the participants was repeating Version A (the in-clinic assessment) on the second assessment at home, rather than selecting the parallel Version B. This error could be ameliorated with more detailed instructions regarding which version should be completed at home first and/or program modifications to reduce the likelihood of incorrect test selection. We also observed that two of the participants had difficulty with the iPad and required additional help over the telephone. In all cases except the one mentioned above, these difficulties were resolved with the telephone support. We can surmise that even with user-friendly devices, some level of training and on-call support may be necessary in order to implement cognitive testing in the home environment. While it is unclear how well these older individuals would have performed without the initial in-clinic instruction, future in-home implementation may require that on-screen instructions be simple, clear and large enough to read so that older individuals would not need prior training to take the tests correctly.

In this study, seven of the eight individuals over the age of 80 were able to perform the C3-PAD without support and 14 of the 49 subjects performed all of the assessments correctly. We also found no significant difference in age, education, sex or IQ between those who were able to complete all assessments correctly from those who did not. This finding is similar to other studies exploring the feasibility of computerized assessment tools in older individuals [22–24], including those that required individuals to complete multiple assessments on a laptop or PC computer [25]. Combined, these studies suggest that older adults of all ages, sex and ability who volunteer for research can successfully perform computerized tests at home. Further work is necessary to determine if this finding is generalizable to the wider population who may be less technologically motivated compared with volunteer research populations.

An additional concern about older individuals using smartphones and tablet computers to perform research testing / clinical care is whether the lack of familiarity with these devices would influence test results, particularly at older age ranges. In order to ensure that the participants could use a touch screen, we had a practice session at the beginning of the C3-PAD assessment to teach people to “touch” rather than “poke” at the screen. We found that some women with long fingernails had more difficulty. While there have been concerns that reaction time on a touch-screen may not be as sensitive as using a handheld mouse, a recent study reported that reaction times between touch screen and mouse were equivalent [26]. Closer examination of the reaction timed tests in this study revealed a high degree of reliability on the individual timed subtests (i.e., the Detection Task and the Identification Task) (Cronbach alpha coefficients ranging from 0.90 to 0.92), suggesting that the touch screen technology could produce reliable results across different test sessions among older adults.

An important limitation not addressed in this study was the feasibility of using the Internet to access the cognitive application or to upload the test results. We did not require subjects to have Internet connectivity because we did not want to limit the feasibility of using the iPad to only those individuals who had Internet access at home. Instead, we set up the iPad with the C3-PAD application already installed and uploaded the data upon their return to the clinic. However, if at-home computerized testing is implemented in clinical trials, subjects will likely need Internet access to both take the cognitive tests and upload their test data.

A recent Pew Research Center Report indicated that 86% of all older individuals ages 65–80+ are Internet users. While there are some people from this generation were early adopters of computer technology, these older individuals tended to be more affluent and more highly educated than non-users. With advancing age, the percentage drops from 74% between the ages of 65–69; 68% between 70–74; 47% between 75–79 and 37% for those over the age of 80. Reassuringly, the percentage of people who become Internet users has increased by six percent every year since 2012, suggesting that Internet use will become more widespread over time. Among older individuals who have not adopted the Internet, reading difficulties or other physical and mental conditions were cited as to the reasons why these newer technologies were not embraced. Financial concerns and skeptical attitudes were also cited, as older individuals did not believe the Internet was necessary for their lives (www.pewinternet.org/2014/04/03/older-adults-and-technology-use/).

Another important limitation to clinical trial implementation involves the accurate identification of the person taking the tests via the device. Fingerprint or other biometric verification technology will be useful to confirm the identity of the subject. Also, simplification of the software that controls the cognitive tests will be necessary so as to avoid inaccurate test selection.

In summary, the findings of this study suggest that with selected iPad / tablet modifications, along with the automation of test version selection and the eventual development of bio-secure access, the feasibility of doing at-home cognitive assessments has promise for inclusion into multicenter clinical trial designs.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge all of the volunteers who participated in the study.

FUNDING: This study was funded by grants from the 21st Century BrainTrust®, (Geoffrey Beene Foundation Alzheimer's Initiative, BrightFocus Foundation, USAgainstAlzheimer), the Alzheimer Association (SG COG-13-282201) and Fidelity Biosciences Research Initiative.

Role of Funder/ Sponsor: The funding sources had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest Disclosure:

Dr. Paul Maruff, Dr. Adrian Schembri and Tanya Chenhall are employees of Cogstate.

Ethical Standards:

The Partners Human Research Committee approved this study. All subjects underwent informed consent procedures.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kaye J. Home-based technologies: a new paradigm for conducting dementia prevention trials. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4(1 Suppl 1):S60–S66. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2007.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sperling RA, et al. The A4 study: stopping AD before symptoms begin? Sci Transl Med. 2014;6(228):228fs13. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3007941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rentz DM, et al. Promising developments in neuropsychological approaches for the detection of preclinical Alzheimer's disease: a selective review. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2013;5(6):58. doi: 10.1186/alzrt222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brandt JSM, Folestein M. The Telephone Interview for Cognitive Status. Neuropsychiatry, Neuropsychology, and Behavioral Neurology. 1988;1(2):111–117. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. Mini-Mental State: A practical method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1975;12:189–198. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(75)90026-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mungas D, et al. Age and education correction of Mini-Mental State Examination for English and Spanish-speaking elderly. Neurology. 1996;46(3):700–706. doi: 10.1212/wnl.46.3.700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wechsler D. WMS-R Wechsler Memory Scale-Revised Manual. San Antonio: The Psychological Corporation, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc.; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ryan A, Paolo J. A screening procedure for estimating premorbid intelligence in the elderly. The Clinical Neuropsychologist. 1992;6:53–62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reitan RM. Manual for Administration of Neuropsychological Test Batteries for Adults and Children. Tuscon: Reitan Neuropsychology Laboratories, Inc.; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benton AL, et al. Contributions to neuropsychological assessment. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yesavage JA, et al. Development and validation of a geriatric depression screening scale. Journal of Psychiatric Research. 1983;17(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/0022-3956(82)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Donohue MC, et al. The preclinical Alzheimer cognitive composite: measuring amyloid-related decline. JAMA Neurol. 2014;71(8):961–70. doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2014.803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jedynak BM, et al. Longitudinal normalization of multiple biomarkers predicts the timing of biomarker changes in Alzheimer's disease progression. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. in press. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grober E. The Free and Cued Selective Reminding Test: evidence of psychometric adequacy. Psychology Science Quarterly. 2009;2009(3):266–282. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wechsler D. WAIS-R Manual: Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale-Revised. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich: The Psychological Corporation; 1981. pp. 1–156. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rentz DM, et al. Face-name associative memory performance is related to amyloid burden in normal elderly. Neuropsychologia. 2011;49(9):2776–2783. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2011.06.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stark SM, et al. A task to assess behavioral pattern separation (BPS) in humans: Data from healthy aging and mild cognitive impairment. Neuropsychologia. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2012.12.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lim YY, et al. Use of the Cogstate Brief Battery in the assessment of Alzheimer's disease related cognitive impairment in the Australian Imaging, Biomarkers and Lifestyle (AIBL) study. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2012;34(4):345–58. doi: 10.1080/13803395.2011.643227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maruff P, et al. Validity of the Cogstate Brief Battery: relationship to standardized tests and sensitivity to cognitive impairment in mild traumatic brain injury, schizophrenia, and AIDS dementia complex. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;24(2):165–178. doi: 10.1093/arclin/acp010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.George DMP. SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference. Vol. 11.0. Boston: Allyn & Bacon; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cortina JM. What is Coefficient Alpha? An Examination of Theory and Applications. Journal of Applied Psychology. 1993;78(1):98–104. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sano M, et al. Pilot study to show the feasibility of a multicenter trial of home-based assessment of people over 75 years old. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2010;24(3):256–263. doi: 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181d7109f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kaye J, et al. Unobtrusive measurement of daily computer use to detect mild cognitive impairment. Alzheimers Dement. 2014;10(1):10–17. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2013.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kaye JA, et al. Intelligent Systems For Assessing Aging Changes: home-based, unobtrusive, and continuous assessment of aging. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2011;66(Suppl 1):i180–i190. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbq095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fredrickson J, et al. Evaluation of the usability of a brief computerized cognitive screening test in older people for epidemiological studies. Neuroepidemiology. 2010;34(2):65–75. doi: 10.1159/000264823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Canini M, et al. Computerized neuropsychological assessment in aging: testing efficacy and clinical ecology of different interfaces. Comput Math Methods Med. 2014;2014:804723. doi: 10.1155/2014/804723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]