Abstract

We explored patterns of self-reported personality trait change across late childhood through young adulthood in a sample assessed up to 4 times on the lower-order facets of Positive Emotionality (PEM), Negative Emotionality (NEM), and Constraint (CON). Multilevel modeling analyses were used to describe both group- and individual-level change trajectories across this time span. There was evidence for nonlinear age-related change in most traits, and substantial individual differences in change for all traits. Gender differences were detected in the change trajectories for several facets of NEM and CON. Findings add to the literature on personality development by demonstrating robust nonlinear change in several traits across late childhood to young adulthood, as well as deviations from normative patterns of maturation at the earliest ages.

Introduction

Although personality traits have traditionally been described as enduring patterns of thinking, feeling, and behaving (Costa & McCrae, 1997), contemporary theories espouse a dynamic perspective that conceptualizes traits as developmental constructs subject to change and adaptation throughout the lifespan (Caspi, Roberts, & Shiner, 2005; Fraley & Roberts, 2005). Recent efforts to capture these processes have focused on describing patterns of personality maturation that characterize the transition from late adolescence to young adulthood (Blonigen, Carlson, Hicks, Krueger, & Iacono, 2008; Donnellan, Conger, & Burzette, 2007; Hopwood et al., 2011; Roberts, Caspi, & Moffitt, 2001). Many prior studies of personality change during this developmental period have focused on describing group-level change rather than exploring the presence or predictors of individual differences in change trajectories (for notable exceptions, see Johnson et al., 2007; Branje, van Lieshout, & Gerris, 2007; Klimstra et al., 2010; deHaan et al., 2013). Additionally, most have focused on higher-order traits rather than those at the facet level, and were limited in their ability to detect nonlinear change owing to their analytic framework or use of only two or three waves of assessment. Theories of the processes that may underlie personality development could be improved by more precise knowledge about the pacing of mean-level changes with age (i.e., linear versus nonlinear), their degree of consistency across different facets of higher-order traits, and the extent to which individuals differ from mean-level trajectories at the population level. Moreover, less is known about whether the maturational trends characteristic of late adolescence and young adulthood are unique to these particular developmental periods, or begin to emerge at even earlier ages.

We used a large longitudinal sample to delineate trajectories of personality change from late childhood (age 11) through young adulthood (age 30). Across four waves of assessment, data were gathered using the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire (MPQ; Tellegen & Waller, 2008), an omnibus measure of normal-range personality that assesses both broad and specific levels of the trait hierarchy. Data were analyzed using multilevel modeling (MLM) to test for nonlinear patterns of change, quantify change parameters at both the group and individual levels, and test for sex differences in these parameters. These design features allowed for a uniquely fine-grained analysis of trait change across a critical developmental window.

Personality development across late adolescence and young adulthood

Young adulthood is the period of the life-course in which the greatest amount of normative change in personality occurs (Roberts, Walton, & Viechtbauer, 2006). Prospective research has consistently revealed mean-level decreases in traits associated with negative emotionality (stress reactivity, neuroticism, aggression, alienation) and increases in traits associated with behavioral constraint (self-control, conscientiousness) across this period (Blonigen et al., 2008; Donnellan et al., 2007; Hopwood et al., 2011; Johnson, Hicks, McGue, & Iacono, 2007; Roberts et al., 2001; Robins, Fraley, Roberts, & Trzesniewski, 2001). By comparison, mean-levels of traits associated with positive emotionality (well-being, extraversion) remain relatively stable.

These findings have been described as reflecting the “maturity principle” of personality development (Caspi et al., 2005), which states that during young adulthood most individuals become more cautious and self-controlled and less prone to negative emotions. The social investment principle (Roberts et al., 2005) proposes that this maturation process begins with taking on new social roles (committed relationships, work, community responsibilities; Arnett, 2000) that prompt changes in identity and behavior that increasingly match role expectations. Individuals who take on these roles, such as entering into committed intimate relationships, do tend to exhibit subsequent increases in trait maturation (i.e., decreases in NE, increases in CN; Neyer & Asendorpf, 2001; Lehnart, Neyer, & Eccles, 2010), although these effects are less consistent when accounting for pre-existing trait differences among those who do and do not begin romantic partnerships (Wagner, Becker, Ludtke, & Trautwein, 2015). Other important psychosocial and biological changes occur during this period, including consolidation and commitment to an identity (Erikson, 1968), the solidification of life story (McAdams & Olson, 2010), and pruning and structural maturation of the prefrontal cortex (Segalowitz & Davies, 2004). Thus, trait change may emerge as a consequence of the developmental challenges of young adulthood, along with psychological mechanisms that supports the ability to navigate this period’s role transitions in ways consistent with unfolding life plans.

Personality development in early to middle adolescence

Recent evidence suggests that the nature of personality development in the early adolescent years is distinct from the maturational trends evident in emerging adulthood. Multiple studies have documented declines in Conscientiousness in early and middle adolescence (Allik et al., 2004; McCrae et al., 2002; Soto et al., 2011; Klimstra et al., 2009), with one exception in females only (Branje et al., 2007). Changes in Neuroticism and Extraversion across adolescence are less consistent across studies (Branje et al., 2007; Allik et al., 2004; Klimstra et al., 2009; McCrae et al., 2002; Pullmann et al., 2006), and a few studies indicating trait change differed across males and females (Soto et al., 2011; McCrae et al., 2002; Klimstra et al., 2009).

In contrast to the role changes that typify young adulthood, adolescence is a period characterized by developmental challenges that may provoke movement away from adjustment. For example, youngsters are more likely to experience reduced positive mood and self-esteem, increased negative mood and risk-taking, and greater conflict with parents during adolescence than in either childhood or young adulthood (Larson, Moneta, Richards, & Wilson, 2002; Arnett, 1999; Hall, 1904). Early adolescence is a time of increasing autonomy from the family and intensification of the impact of peer relationships on self-worth (Parker et al., 2006), as well as growing pressures from socializing agents for youngsters to demonstrate competency at more challenging tasks. The uncertainty of success in response to these pressures may destabilize early trait patterns, produce trait changes that are different than those characterizing later adolescence.

Less is known about personality development during early adolescence than during late adolescence/emerging adulthood, some studies were cross-sectional, and few captured the earliest ages of adolescence or preadolescence or covered the entirety of adolescence through emerging adulthood. Thus, we aim to provide important information regarding longitudinal change in traits across late childhood through young adulthood (for a cross-sectional investigation of mean-level differences over this time period, see (Soto et al., 2011).

Understanding personality development from late childhood through young adulthood

Any effort to provide a comprehensive examination of personality development across this formative period must address several factors. First, linear change models are likely insufficient to describe trajectories across very different developmental periods. Specifically, the normative pattern of maturation of traits seen in young adulthood may not extend backward to adolescence in a linear fashion. Consistent with the notion of adolescence as a time when increasing developmental pressures act on individuals who have yet to develop adult levels of competence, depression and low self-esteem (correlates of low positive emotionality and high negative emotionality) as well as risk-taking and criminality (markers of low behavioral constraint) are elevated in adolescence in comparison to either childhood or young adulthood (Arnett, 1999). Thus, during adolescence these traits may exhibit trends that are the opposite of the pattern of maturation observed in young adulthood. Consistent with this, a meta-analysis of 14 studies with samples aged 10 to 20 years found that early adolescence was associated with declines in conscientiousness, openness, extraversion, and emotional stability (Denissen, van Aken, Penke, & Wood, 2013), confirming findings of earlier studies (Allik et al., 2004; Harden & Tucker-Drob, 2011; Johnson et al., 2007; McCrae et al., 2002)(Soto et al., 2011). Decreases in agreeableness and conscientiousness across late childhood to middle adolescence were recently replicated in yet another study (van den Akker, Dekovic, Asscher, & Prinzie, 2014). The present study extended this work by testing for nonlinear trends in a longitudinal design with four waves of assessment, providing a fine-grained analysis of change in personality traits from late childhood through young adulthood.

Second, findings regarding sex differences have been less consistent than those for general maturational trends. Some evidence suggests the changes in higher-order traits in young adulthood are fairly uniform across sex (Blonigen et al., 2008; Donnellan et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2001). However, others have found sex differences in trait development. Specifically, some have reported that females increased on negative emotionality traits during adolescence, whereas such traits tended to remain stable or decrease in males (McCrae et al., 2002; Soto et al., 2011). During late adolescence and young adulthood, traits associated with behavioral constraint (e.g., conscientiousness) have been found to increase at a faster rate in females than males (Blonigen et al., 2008; Branje et al., 2007; Donnellan et al., 2007; Klimstra et al., 2009; Roberts et al., 2001; Soto et al., 2011). These differences in trait development may be due to sex differences in maturational processes, socialization, the extent and timing of their exposure to normative transitions, or the psychological meaning of those transitions.

Third, most prospective studies of personality development in either adolescence or young adulthood have focused on changes at the higher-order level of the trait hierarchy – Big 5 or Big 3 domains (Allik et al., 2004; Branje et al., 2007; De Fruyt et al., 2006; Hopwood et al., 2011; McCrae et al., 2002; Pullmann et al., 2006). However, in their cross-sectional study, Soto et al. (2011) observed different age trends for several facets from the same domain. Differences are most pronounced across facets of neuroticism/negative emotionality and conscientiousness/ behavioral constraint (Jackson et al., 2009). Similarly, in an epidemiological sample of youth assessed from ages 12 to 24, Harden and Tucker-Drob (2011) reported divergent patterns of change for facets of behavioral constraint. Mean levels of impulsivity exhibited a monotonic decline, whereas levels of sensation-seeking displayed a nonlinear pattern – increasing during early adolescence then gradually declining over late adolescence and young adulthood. Collectively, these findings suggest that lower-order traits may reveal a more complex picture of the rate and timing of personality maturation.

The present study

Using data from large community-epidemiological samples assessed up to four time points, we modeled individual differences in personality trait trajectories from late childhood through the entirety of young adulthood. Several studies have reported significant individual-level changes for traits during adolescence (McCrae et al., 2002; Shiner & Caspi, 2003) and young adulthood using reliable change indices (Blonigen et al., 2008; Donnellan et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2001; Robins et al., 2001). We extended this prior research through the use of multilevel modeling (MLM) to test for nonlinear as well as linear change, and to quantify individual differences in the parameters of change.

Method

Sample

Participants were members of three ongoing longitudinal studies conducted at the Minnesota Center for Twin and Family Research (Iacono, McGue, & Krueger, 2006): the Minnesota Twin Family Study (MTFS; Iacono, Carlson, Taylor, Elkins, & McGue, 1999), the Minnesota Twin Family Study Enrichment Sample (MTFS-ES; (Keyes et al., 2009), and the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS; (McGue et al., 2007). For all studies, families that met the biological relationship conditions were eligible if they lived within a day’s drive of the University of Minnesota laboratories and neither target child had a mental or physical disability that would preclude participating in the day-long assessment. The MTFS and MTFS-ES are community-based studies of twins born in Minnesota from 1972-1984 and 1988-1994, respectively. Eligible families were identified using public birth records and located using other publically available databases. The MTFS used an accelerated cohort design with families recruited to participate the year the twins turned either 11 (n=1517) or 17 years old (n=1252). For the MTFS-ES (n=998), all families were recruited the year the twins turned 11 years old. All twin pairs were same-sex. For any given birth year, over 90% of twin families were located and over 80% agreed to participate. For the MTFS-ES, an additional screening procedure was used to ensure that for one-half of the participating families, at least one twin exhibited elevated conduct problems. No significant differences were observed between participating and non-participating families on self-reported history of mental health problems or SES, so that the final sample was representative of the Minnesota population for the target birth years on key demographic variables (Iacono et al., 1999; Keyes et al., 2009). The sample included slightly more female (51.9%) than male (48.1%) participants, with 96% of the sample being of European American ancestry. Twins were invited to participate in follow-up assessments at 3-4 year intervals.

The SIBS is an adoption study that included 409 adoptive families and 208 non-adoptive control families (n = 1232). All families included two siblings within 5 years of age of one another, each between the ages of 11 and 21 years old at the intake assessment. Adoptive families were ascertained from private adoption agencies in Minnesota, and included two biologically-unrelated siblings (though one sibling could be a biological child of the parents). The mean age of placement for all adopted siblings was 4.7 months (SD = 3.4 months). Non-adoptive families were identified from public birth records and selected to include a pair of full biological siblings comparable in age and gender to the adoptive sibling pairs. Siblings pairs were either same-sex (60.8%) or opposite-sex (39.2%) with slightly more female (54.9%) than male (45.1%) participants overall. About two-thirds of adoptions were international, such that for the total sample 55.8% of participants were of European-American ancestry and 44.2% were of non-European (primarily East Asian) ancestry.

Participation rates were 63.2% for adoptive and 57.3% for non-adoptive families. Demographic information including parental education and occupation, rates of remarriage in the parents, and behavioral problems in the offspring was obtained from 73% of non-participating families to assess any recruitment bias. The only significant difference was greater educational attainment for mothers of the non-adoptive families, suggesting families were broadly representative of their respective populations. Siblings were invited to participate in two follow-up assessments at 3-4 year intervals.

Table 1 lists the age distribution and number of participants for each assessment wave, or time point. Wave 1 refers to the intake assessment, and so includes the total number of participants across all studies. The declining number of participants with increasing time points is a function of attrition, ongoing assessments, and study design. Only the Wave 2 (1st follow-up) assessment is completed for all studies, with an overall retention rate of 92.1% across all studies. Ongoing assessments include Wave 3 (2nd follow-up) for the MTFS-ES and SIBS and Wave 4 for the MTFS-ES. Participants of the age 17 cohort of the MTFS have completed all scheduled assessments. The SIBS sample is currently only scheduled to complete three waves of assessment. Despite the ongoing and unequal number of assessments across participants, when data were aggregated across all samples and all time points, there was sufficient coverage of every age to model developmental trends from ages 11 to 30 (see Table 1; Ns ranged from 43 (at age 27) to 1947 (at age 17), with a mean N of 592 at each chronological year between 11 and 30). The mean true retention rate was about 90% across all completed follow-up assessments for the SIBS and different age and gender cohorts of the MTFS and MTFS-ES.

Table 1.

Number of participants of each age at each assessment wave

| Age | Assessment wave 1 |

Assessment wave 2 |

Assessment wave 3 |

Assessment wave 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 10 | 6 | |||

| 11 | 104 | |||

| 12 | 119 | |||

| 13 | 255 | 5 | ||

| 14 | 1047 | 82 | 1 | |

| 15 | 878 | 110 | ||

| 16 | 762 | 153 | ||

| 17 | 1152 | 795 | ||

| 18 | 479 | 742 | ||

| 19 | 99 | 375 | 49 | |

| 20 | 32 | 465 | 14 | |

| 21 | 16 | 238 | 23 | |

| 22 | 2 | 41 | 19 | |

| 23 | 20 | 127 | 97 | |

| 24 | 38 | 335 | 530 | |

| 25 | 83 | 408 | 423 | 15 |

| 26 | 17 | 90 | 76 | 3 |

| 27 | 8 | 15 | 19 | 1 |

| 28 | 3 | 25 | 131 | 99 |

| 29 | 23 | 117 | 453 | 376 |

| 30 | 8 | 38 | 100 | 119 |

| 31 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 13 |

| 31 | 4 | 4 | 13 | 13 |

| 32 | 1 |

Personality Assessment

The MPQ assesses an individual’s typical affective and behavioral styles relevant to 11 trait constructs. The MPQ scales are listed in Table 2 with descriptions of high scorers for each and estimates of internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) for the most common assessment ages (14, 17, 20, 24, 29). Correlations among the 11 primary scales exhibit either 3- or 4-factor higher-order structures that include Positive Emotionality (PEM), Negative Emotionality (NEM), and Constraint (CON), with PEM splitting into Agentic and Communal-PEM for the 4-factor structure (Patrick, Curtin, & Tellegen, 2002). Achievement and social potency scales define Agentic-PEM, with higher scorers described as enjoying working hard, reaching goals, and being dominant and persuasive in social contexts. Social closeness and well-being scales define Communal-PEM; high scorers value intimate interpersonal ties and have optimistic and cheerful dispositions. Stress reaction, alienation, and aggression scales define NEM with high scorers described as experiencing elevated levels of negative emotions, sensitivity to stress and interpersonal slights, and having antagonistic and hostile interpersonal styles. Control, harm avoidance, and traditionalism define CON with high scorers described as planful and cautious, risk aversive, and endorsing conservative moral and ethical values. Absorption is a primary scale that does not load principally on a single factor; high scorers are described as experiencing vivid and compelling images and readily becoming easily engrossed in sensory stimuli.

Table 2.

Scale Descriptions and Internal Consistency Reliability Estimates for the MPQ Scales

| MPQ Scale | Age 14 | Age 17 | Age 20 | Age 24 | Age 29 | Description of a High Scorer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Well-being | .89 | .88 | .92 | .90 | .90 | Has a cheerful disposition; tends to be optimistic, lives an active and exciting life |

| Social Potency | .87 | .90 | .89 | .90 | Prefers to take charge; is persuasive; enjoys influencing people; decisive |

|

| Achievement | .87 | .88 | .87 | .88 | Enjoys demanding projects; will put work ahead of their activities; diligent |

|

| Social Closeness | .87 | .88 | .89 | .89 | Sociable; enjoys the company of others; values close interpersonal ties |

|

| Stress Reaction | .87 | .87 | .89 | .89 | .90 | Prone to worry; sensitive; easily upset or irritable; guilt prone |

| Alienation | .88 | .87 | .87 | .91 | .92 | Suspicious of others’ motives; feels they are often treated unfairly; sees self as victim |

| Aggression | .91 | .90 | .87 | .88 | .88 | Competitive; will intimidate others; may seek revenge for a perceived wrongdoing |

| Control | .86 | .84 | .88 | .87 | .88 | Reflective and rational; likes to plan ahead; cautious |

| Harm Avoidance | .84 | .84 | .84 | .87 | .87 | Would prefer safe and tedious to potentially risky and exciting tasks |

| Traditionalism | .78 | .85 | .81 | .79 | Values high moral standards and a conservative social order; rarely challenges authority |

|

| Absorption | .86 | .87 | .88 | .89 | Easily engrossed in sensory experiences; may think in terms of images |

The full set of 11 primary scales was assessed using the 198-item version of the MPQ at the age 17, 24, and 29 assessments of the MTFS and MTFS-ES. An abbreviated version with items for six scales only (well-being, stress reaction, alienation, aggression, control, and harm avoidance) was administered to twins at the age 14 assessment. Female twins from the age 17 cohort also completed these 6 scales only at the age 20 assessment. For the SIBS, all participants 16 years of age and older completed all scales, while all participants younger than 16 years old completed the abbreviated 6-scale version. For any given assessment, 83% to 93% of participants had MPQ data. 632 participants had personality data at 4 assessments and an additional 1340 had personality data for 3 assessments. Thus, analyses focused on individual differences in nonlinear trajectories are based on a smaller subset of participants with three or more completed assessments (N = 1972). The total sample (N = 5001) contributed to analyses describing the form of change in the sample as a whole (both linear and nonlinear change) and individual differences in linear change. We tested for patterns of missingness separately for the 6 scales that were administered at all waves (well-being, stress reaction, alienation, aggression, control, and harm avoidance) and those that were deliberately administered only at some waves (social closeness, achievement, social potency, traditionalism, harm avoidance). For the first set of scales, data were missing completely at random, Little’s MCAR Chi-square (82) = 101.94, p = .067. For the second set, data were missing completely at random, Little’s MCAR Chi-square (27) = 33.31, p = .187.

Data analysis

For each MPQ scale, age-related change was evaluated using MLM with full information maximum likelihood estimation. Each model included three levels to account for the nesting of assessments within participants and participants within families. The highest level was family (twin pairs, adoptive siblings; level-3), followed by participant (level-2), and repeated observations within participant across time (level-1). For each scale, a series of models was employed to (1) quantify the overall degree of age-related change, (2) describe the shape of change in the sample (linear, nonlinear), (3) test whether males and females exhibited differential change trajectories; and (4) quantify individual differences in change. Significant fixed effects indicate those parameters that capture the shape of change across the entire sample, and significant variance components indicate those parameters for which there were individual differences across participants. Because participants varied in chronological age at the time of each assessment, change was modeled as a function of participants’ actual ages at each assessment, rather than by assessment wave, allowing for more precise estimates of change parameters over time.

To explore the simplest form of change that might characterize the sample and for comparison to other studies that have reported on linear change, we first tested whether personality scales exhibited linear change by comparing unconditional means models to unconditional growth models. The unconditional means model included only an intercept term reflecting the overall elevation of the scale, but no linear slope coefficient. The unconditional growth model added a slope parameter. To facilitate interpretation of the intercept parameter, we centered the intercept such that it reflected the earliest age at which that particular scale was collected (specifically, 11 years for well-being, stress reaction, alienation, aggression, control, and harm avoidance; 14 years for social potency, achievement, social closeness, traditionalism, and absorption). Thus, the intercept reflected the model-derived scale score at age 11 or 14 and the slope coefficients reflected the degree of linear and nonlinear change in that scale as a function of increasing age after 11 or 14 years. Models were compared to one another by reference to their AIC; models with smaller AIC models provide a better ft to the data.

We evaluated one potential predictor of individual differences in change—participant sex— by incorporating it as a level-2 predictor of individual differences in change parameters, added to the best-fitting model for each scale. For example, for traditionalism, we tested the following model:

In this example, the first term, B00 + B01*(SEX) + R0, models the intercept of traditionalism at age 11, with B01 representing the effect of being male on the intercept (B00) and R0 error. The second term, AGE *(B10 + B11*(SEX) + (R1), models the effect of being male (B11) on the linear slope for age (B10), along with an error term. Models for scales with significant nonlinear effects also included sex as a predictor of the quadratic and cubic age parameters. Finally, to test for individual differences in level-1 change parameters, we added variance components to the best fitting fixed effects model (i.e., the one with the lowest AIC value). Because each additional variance component at level-1 added several parameters to the model, we were limited to exploring individual differences in up to 3 parameters in any one model (i.e., intercept, linear change, quadratic change). In all models, only one random effect (on the intercept) was estimated at level-3, as it included only two observations (twins, siblings).

Results

Linear change in personality scales as a function of age

For 9 of 11 MPQ scales, there were significant fixed effects of age in the unconditional growth models. Decreases were evident for social potency, stress reaction, alienation, aggression, and absorption, and achievement, control, harm avoidance, and traditionalism all increased with age. Well-being and social closeness did not exhibit linear change. Table 3 shows the MLM linear growth parameters and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) for the scales. The ICC provides an index of trait stability, indicating the proportion of total variance in scale scores, including within-person variability across time, attributable to between-person differences. The scales with the least stability across time were traditionalism, alienation, and aggression, while the greatest temporal stability was evident for social potency. Table 4 shows descriptive statistics for estimated intercept and linear slope parameters for the linear change models. Consistent with the significant variance components for all scales, these estimates demonstrate considerable individual deviation from the sample mean trajectories.

Table 3.

Unconditional growth models for each MPQ personality subscale

| Fixed effects | Variance components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Intercept coeff (SE) |

Linear Age coeff (SE) |

Intercept | Linear Age | ICC |

| Well-being | 55.64 (0.17)a | 0.00 (0.01) | 27.20a | 0.09a | .34 |

| Social potency | 46.30 (0.21)a | −0.07 (0.02)a | 37.10a | 0.20a | .50 |

| Achievement | 47.75 (0.18)a | 0.28 (0.02)a | 44.38a | 0.20a | .41 |

| Social closeness | 54.31 (0.18)a | 0.01 (0.02) | 40.08a | 0.21a | .43 |

| Stress reaction | 43.89 (0.20)a | −0.24 (0.02)a | 39.19a | 0.15a | .40 |

| Alienation | 38.30 (0.19)a | −0.50 (0.02)a | 39.11a | 0.14a | .29 |

| Aggression | 41.48 (0.21)a | −0.61 (0.01)a | 55.53a | 0.10a | .30 |

| Control | 44.95 (0.16)a | 0.39 (0.01)a | 38.85a | 0.12a | .43 |

| Harm avoidance | 45.38 (0.22)a | 0.30 (0.02)a | 50.26a | 0.21a | .41 |

| Traditionalism | 50.45 (0.16)a | 0.10 (0.01)a | 17.88a | 0.12a | .28 |

| Absorption | 44.41 (0.20)a | −0.36 (0.02)a | 41.57a | 0.25a | .35 |

Note. ICC = proportion of the variance in the trait due to between subjects differences (vs. within subjects variation across time).

= p < .0001, with no adjustments for multiple testing. Intercept values reflect scores at age 11 for the well-being, stress reaction, alienation, aggression, control, and harm avoidance scales, and for age 14 for social potency, achievement, social closeness, traditionalism, and absorption.

Table 4.

Descriptive statistics for model-derived participant-specific growth curve parameters

| Intercept coefficient | Slope coefficient | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Trait | Mean | SD | Min | Max | Mean | SD | Min | Max |

| Well-being | 55.65 | 5.33 | 30.37 | 69.73 | 0.00 | 0.11 | −0.44 | 0.56 |

| Social potency | 46.36 | 6.45 | 23.80 | 67.59 | −0.07 | 0.20 | −1.23 | 1.17 |

| Achievement | 47.77 | 6.36 | 24.18 | 67.32 | 0.28 | 0.21 | −1.65 | 1.40 |

| Social closeness | 54.30 | 6.30 | 26.14 | 69.47 | 0.01 | 0.21 | −1.10 | 1.01 |

| Stress reaction | 43.89 | 6.45 | 25.01 | 66.15 | −0.24 | 0.15 | −0.94 | 0.44 |

| Alienation | 38.29 | 6.46 | 23.17 | 63.36 | −0.50 | 0.16 | −1.28 | 0.20 |

| Aggression | 41.47 | 8.22 | 22.44 | 71.12 | −0.61 | 0.19 | −1.33 | 0.05 |

| Control | 44.95 | 5.61 | 25.88 | 65.75 | 0.39 | 0.14 | −0.22 | 1.10 |

| Harm avoidance | 45.40 | 8.25 | 17.75 | 66.91 | 0.30 | 0.20 | −0.47 | 1.31 |

| Traditionalism | 50.50 | 5.17 | 28.84 | 67.15 | 0.10 | 0.14 | −0.65 | 0.73 |

| Absorption | 44.41 | 6.80 | 25.07 | 70.01 | −0.36 | 0.22 | −1.46 | 1.24 |

Nonlinear changes in personality traits across late childhood through young adulthood

Individual deviations from sample-based change trajectories could also indicate misfit of the linear change model. As we had up to four assessments, we were able to test for nonlinear change (quadratic and cubic terms). We sequentially added a quadratic and then a cubic age term as fixed effects in models for each trait, while fixing the variance in all parameters except the intercept. We evaluated model fit by comparing the AICs across models with additional change parameters.

For all scales except traditionalism and absorption, the best fitting model included both quadratic and cubic change terms; model coefficients are shown in Table 5. For comparison, we also report the best fitting models for the higher-order MPQ scales. These results demonstrate the utility of exploring personality trait change at the facet level, as the results for the broader dimensions did not entirely parallel that for the narrower facets within PEM, NEM, and Constraint. For social closeness, although the AIC for the model including a cubic term was the smallest, it differed only marginally from that with only linear and quadratic age terms (56263.80 versus 56265.83), and the coefficient for the cubic term was nonsignificant (p = .058). Therefore, in subsequent analyses, we considered the quadratic model to be the best fitting model for social closeness. Finally, we tested whether model parameters varied across the different samples (twin and adoption samples) by entering a dummy code for sample as a level-2 predictor of each change parameter. Of the 40 sample dummy code effects estimated, none were significant.

Table 5.

Best-fitting models incorporating nonlinear (quadratic, cubic) effects of age on personality traits

| Fixed Effects | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Intercept coeff (SE) |

Age coeff (SE) |

Age2

coeff (SE) |

Age3

coeff (SE) |

Model fit AIC |

| Well-being | 58.07 (0.49)a | −0.80 (0.16)b | 0.07 (0.02)a | −0.002 (0.0005)a |

76744.34 |

| Social potency | 34.67 (2.67)a | 3.21 (0.62)a | −0.27 (0.05)a | 0.007(0.001)a | 55842.24 |

| Achievement | 37.01 (2.42)a | 2.81 (0.67)a | −0.19 (0.06)b | 0.004(0.001)b | 55921.78 |

| Social closeness | 48.66 (2.48)a | 1.49 (0.68)c | −0.12 (0.06)c | 0.003(0.001) | 56367.04 |

| Stress reaction | 40.08 (0.55)a | 1.04 (0.18)a | −0.12 (0.02)a | 0.003 (0.0005)a | 79716.24 |

| Alienation | 37.02 (0.56)a | 0.12 (0.18) | −0.08 (0.02)a | 0.003 (0.001)a | 78490.50 |

| Aggression | 38.66 (0.56)a | 0.59 (0.18)b | −0.14 (0.02)a | 0.005 (0.0005)a | 79000.17 |

| Control | 47.20 (0.48)a | −0.51(0.16)b | 0.10 (0.02)a | −0.003 (0.0005)a |

76594.40 |

| Harm avoidance | 53.13 (0.61)a | −2.22 (0.20)a | 0.22 (0.02)a | −0.006 (0.0006)a |

81311.51 |

| Traditionalism | 50.43 (0.16)a | 0.10 (0.02)a | -- | -- | 52751.09 |

| Absorption | 44.40 (0.20)a | −0.35 (0.02)a | -- | -- | 58001.29 |

| PEM | 116.45 (1.42)a | 2.91 (0.59)a | −0.32 (0.07)a | 0.01 (0.002)a | 62466.01 |

| NEM | 100.94 (0.91)a | −2.14 (0.16)a | 0.05 (0.006)a | -- | 63228.56 |

| CON | 128.46 (0.58)a | 1.24 (0.14)a | −0.02 (0.007)b | -- | 65083.17 |

Note.

= p < .001;

= p < .01;

= p < .05;

no adjustments for multiple testing. Intercept values reflect scores at age 11 for the well-being, stress reaction, alienation, aggression, control, and harm avoidance scales, and for age 14 for social potency, achievement, social closeness, traditionalism, and absorption. Random effects are estimated for the intercept; all other parameters (age, age2, and age3) were fixed.

To ensure that the mean-level changes we detected were not primarily due to a lack of measurement invariance across different ages (i.e., differential loading of MPQ items on their respective latent scales across different developmental periods) rather than true developmental change, we fit confirmatory factor analytic models assessing measurement invariance using item-level data for each scale at ages 17 and 24. We examined these two ages because they anchored the period wherein we detected the greatest amount of change and because we had the most observations at these two points, allowing for maximal power to detect invariance. Because the sample size would yield a significant difference in the chi square fit index for even well-fitting models, we focused on differences in the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), and the RMSEA and SRMR for indices of overall fit. None of the scales exhibited a decline in fit when item loadings were constrained to equality across ages 17 and 24, as indexed by the RMSEA; the change in the SRMR ranged from 0.000 to 0.003 across scales, indicating a trivial change in model fit. With one exception (aggression), for each MPQ scale the BIC was lower (indicating better fit) after constraining the factor loadings to be the same at ages 17 and 24. For the aggression scale, the BIC values increased when the factor loadings were constrained, but the RMSEA values did not change (0.048; indicative of good model fit), and the SRMR increased by only 0.005 while maintaining a good overall fit (0.054). Thus, the changes we detected were likely due to developmental changes in trait levels rather than differences in measurement properties of the scales at different ages.

Below, we describe the form of change for each trait from models including all participants, as well as sex differences in these trajectories.

Individual differences in personality trait change

To evaluate individual differences in age-related change, we compared the best fitting models described above (shown in Table 5), which included a variance component only for the intercept parameter, to ones in which we also allowed the linear effect of age to vary. For every trait, the model in which both the intercept and linear age parameter were allowed to vary across persons provided a superior fit. Thus, there was evidence of individual differences in the degree of linear age-related change for all traits. Because we were limited by degrees of freedom to a maximum of two level-1 variance components per model, we were not able to include variance components for all of the change parameters in models that included quadratic and cubic age effects. However, to provide some preliminary tests of the presence of individual differences in nonlinear age-related change, we ran models in which variance was estimated for the linear and quadratic effects of age (intercept and cubic terms were fixed). These models were estimated for all traits except traditionalism and absorption, which did not exhibit nonlinear change. For all traits tested, these models revealed significant variance components for both the linear and quadratic age effects. However, the AICs were uniformly larger (i.e., model fit was worse) for these models than those in which the intercept and linear age effects were freely estimated, suggesting that the bulk of individual differences were evident in initial elevation of traits, with less (but significant) variance evident in linear and nonlinear age-related change.

Sex differences in personality trait trajectories

We evaluated one potential predictor of individual differences in developmental trajectories —participant sex— by incorporating it as a level-2 predictor of individual differences in change parameters (intercept, linear, nonlinear change), added to the best-fitting model for each scale. Table 6 shows the coefficients for all level-1 growth parameters and the level-2 effects of sex on each parameter. Because sex was coded as 0 = female and 1 = male, the coefficients for the level-1 parameters reflect the values for females, while the level-2 coefficients reflect the difference between males and females on these parameters. For 6 of the 11 scales there were significant effects of sex on at least one parameter.

Table 6.

Sex differences in personality trait trajectories

| Level-1 fixed effects | Level-2 fixed effects of sex | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trait | Intercept coeff (SE) |

age coeff (SE) |

age2

coeff (SE) |

age3

coeff (SE) |

Intercept coeff (SE) |

age coeff (SE) |

age2

coeff (SE) |

age3

coeff (SE) |

AIC |

| Well-being | 58.27a

(0.66) |

−0.74b

(0.22) |

0.06c

(0.02) |

−0.002c

(0.0007) |

−0.71 (0.95) |

0.05 (0.31) |

0.02 (0.03) |

−0.0007 (0.001) |

76743.20 |

| Social potency | 41.90a

(1.22) |

1.81a

(0.51) |

−0.23a

(0.06) |

0.008a

(0.002) |

−0.02 (1.66) |

0.02 (0.69) |

0.05 (0.08) |

−0.003 (0.003) |

55744.62 |

| Achievement | 44.21a

(1.22) |

1.56b

(0.50) |

−0.14c

(0.06) |

0.004c

(0.002) |

−0.86 (1.79) |

0.55 (0.75) |

−0.03 (0.09) |

0.0003 (0.003) |

55882.84 |

| Social closeness |

54.95a

(0.43) |

0.20 (0.10) |

−0.006 (0.006) |

-- | −2.14b

(0.61) |

−0.19 (0.15) |

0.003 (0.008) |

-- | 56191.17 |

| Stress reaction | 39.37a

(0.71) |

1.75a

(0.24) |

−0.19a

(0.02) |

0.005a

(0.0007) |

2.32c

(2.28) |

−1.78a

(0.35) |

0.15a

(0.04) |

−0.004a

(0.001) |

79543.72 |

| Alienation | 35.54a

(0.72) |

0.35 (0.24) |

−0.10a

(0.02) |

0.003a

(0.007) |

4.24a

(1.11) |

−0.78c

(0.36) |

0.06 (0.04) |

−0.001 (0.001) |

78454.37 |

| Aggression | 35.93a

(0.67) |

0.35 (0.22) | −0.12a

(0.02) |

0.004a

(0.0006) |

6.85a

(1.17) |

0.32 (0.37) |

−0.03 (0.04) |

0.001 (0.001) |

78207.11 |

| Control | 48.70a

(0.59) |

−0.79a

(0.20) |

0.14a

(0.02) |

−0.004a

(0.0006) |

−3.43a

(0.99) |

0.68c

(0.32) |

−0.09b

(0.03) |

0.003b

(0.009) |

76465.41 |

| Harm avoidance |

55.06a

(0.74) |

−2.10a

(0.24) |

0.23a

(0.02) |

−0.006a

(0.0007) |

−2.81c

(1.25) |

−0.44 (0.40) |

−0.03 (0.04) |

0.002 (0.001) |

80676.06 |

| Traditionalism | 51.11a

(0.22) |

0.06b

(0.02) |

-- | -- | −1.44a

(0.31) |

0.08c

(0.03) |

-- | -- | 52730.22 |

| Absorption | 45.13a

(0.29) |

−0.46a

(0.03) |

-- | -- | −1.45a

(0.40) |

0.19a

(0.04) |

-- | -- | 57968.76 |

| Absorption | 45.13a

(0.29) |

−0.46a

(0.03) |

-- | -- | −1.45a

(0.40) |

0.19a

(0.04) |

-- | -- | 57968.76 |

Note.

= p < .0001;

= p < .001;

= p < .05;

no adjustments for multiple testing. Sex coded as 0 = female, 1 = male. Intercept values reflect scores at age 11 for the well-being, stress reaction, alienation, aggression, control, and harm avoidance scales, and for age 14 for social potency, achievement, social closeness, traditionalism, and absorption.

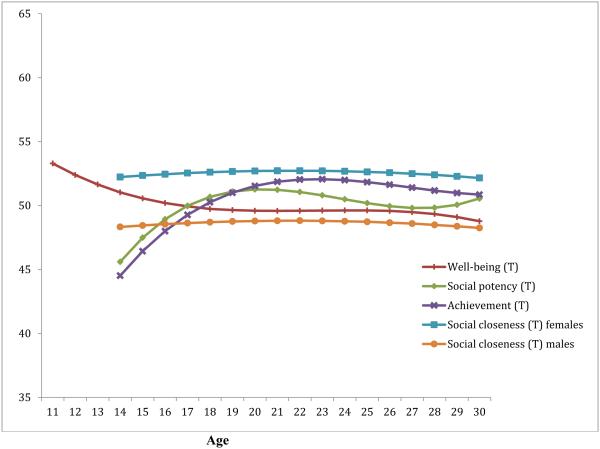

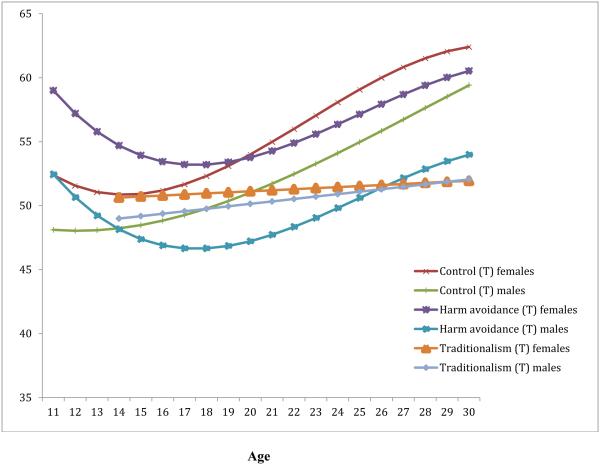

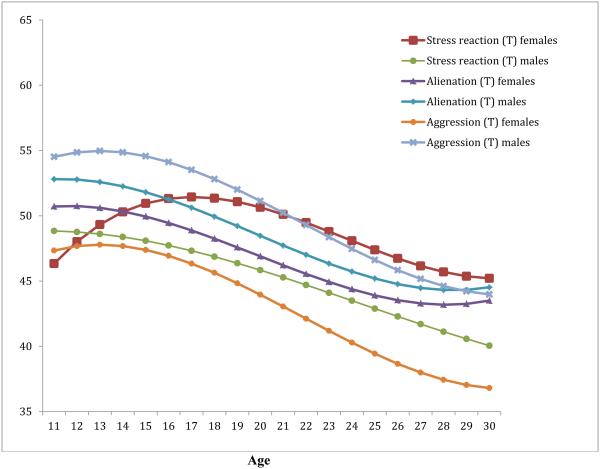

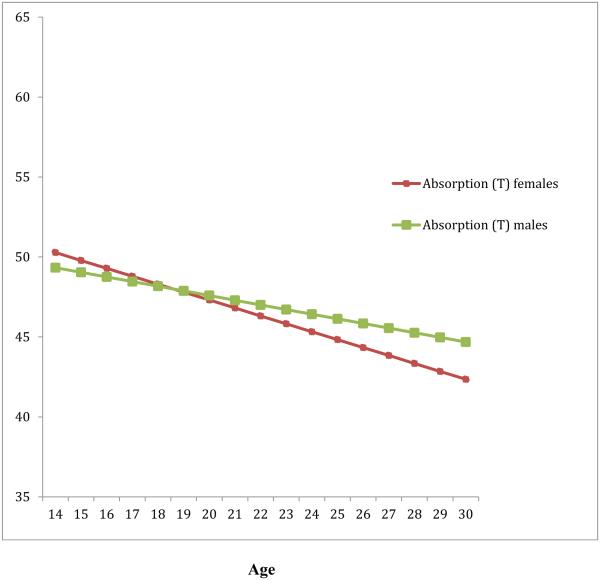

Figures 1-3 show the model-derived change trajectories for males and females on each scale. Thus, they do not represent the observed values, but rather the predicted scale values calculated by entering different age values for each sex into the MLM equation from the best-fitting change models for each scale. Model-derived estimates were transformed by placing each on a T-scale so that the values were consistent across different scales.

Figure 1.

Model-derived change trajectories for PEM traits (T scores) in males and females

Figure 3.

Model-derived change trajectories for CON traits (T scores) in males and females

Males and females did not differ in change trajectories for any PEM scale, although they did differ on their overall level of social closeness. However, the four PEM scales did exhibit distinct developmental trajectories. The two components of communal PEM (well-being and social closeness) demonstrated only modest change. Aspects of agentic PEM exhibited more pronounced nonlinear change. Social potency exhibited a striking increase across mid to late adolescence, with a more modest subsequent decline in the 20s. Achievement increased substantially across adolescence through early adulthood, the period most typified by developmental challenges to establish educational and occupational credentials.

For the NEM scales, both the overall magnitudes of change and sex differences in these patterns were more striking than those observed for PEM traits. The simplest pattern of sex differences was in aggression, for which males and females differed only on the elevation of the trajectory, but not on age-related change parameters. Overall, the sample increased slightly in aggression through middle adolescence, then declined to a marked degree across the remainder of the study period. Thus, while the press towards maturation on this trait was clearly evident in adolescence and early adulthood, it was preceded by a period in late childhood to early adolescence in which the sample deviated from maturation.

For stress reaction, males and females differed on each change parameter. While males exhibited steady declines in stress reaction across late childhood and early adulthood, females had a period of increasing stress reaction from late childhood through adolescence before finally exhibiting their own decline on stress reaction that did not begin until late adolescence. The sex difference in change parameters was so substantial that it reversed the sex difference on this trait that was evident at age 11, when girls had lower levels than boys, to the opposite pattern by age 30, when women were higher than men on stress reaction.

For alienation, substantial declines were evident for both males and females from late childhood to adulthood, though this decrease was somewhat greater for males. For both sexes, declines were most dramatic across mid-adolescence to the mid-twenties.

Sex differences were evident for all CON scales. The simplest pattern was for traditionalism, which included only linear effects of age; there were significant sex differences on both the intercept and linear slope for this scale. Males had a lower mean than females at 14, but they increased twice as much over time than females, such that the sexes did not differ on their levels of traditionalism by age 30. The increases for both sexes on this trait were quite modest across this wide developmental period, suggesting that it was subject to weaker developmental pressures than many other traits we examined.

For control, the male and female trajectories had similar shapes, though changes were more dramatic for females (in addition to a higher overall level of control among females). For males, the trajectory was flat across early adolescence, followed by an increase across the remainder of the developmental period. For females, their scores decreased slightly across the earliest ages, then increased over the remainder of the ages assessed. Males and females differed only on the intercept for harm avoidance; the patterns of nonlinear change in that trait were similar for both sexes. For both sexes, harm avoidance decreased from late childhood to age 18, after which the trajectory reversed, such that this trait increased substantially late adolescence to age 30. Thus, for two aspects of Constraint (control, harm avoidance), the sample exhibited deviations from maturation at the earliest ages.

Finally, for absorption, the best fitting change model included only a linear effect of age. Males had a lower mean than females at age 14, but females declined more rapidly than males from ages 14 to 30. By age 30, females had lower average scores than males, reversing the mean level sex difference evident in late childhood.

Discussion

If we are to understand the dynamics of personality development, we must first precisely document its natural course, including both normative trends and the extent of individual variation around these trends. Though previous research has made considerable progress in doing this, the present study advanced this project in several important ways. First, we delineated normative patterns and individual differences in personality change across the critical developmental time frame from late childhood (age 11) through young adulthood (age 30), thus linking development across all of adolescence with that across young adulthood. Second, we used a measure of normal-range personality that assesses lower levels of the trait hierarchy, making it possible to identify distinct developmental patterns in aspects of personality that are typically collapsed together in many studies. Finally, we used a statistical technique that allowed us to identify nonlinear patterns of change and test for sex differences in these patterns. Though the results of our analyses broadly confirmed those from prior studies, the long time-span of observation and fine level of detail available to us made possible some new observations as well as clarifications of prior findings that will inform future theorizing about the nature of personality development from late childhood through early adulthood.

Implications of examining development over a long time-span

For 9 of the 11 MPQ scales, models including quadratic and cubic terms provided significantly better fit than those including only linear terms. This highlights the importance of using multiple assessments (necessary for detecting nonlinear changes) and of considering a long period of developmental time. Although the trajectories for some traits were clearly consistent with overall trends toward personality maturation, there were many for which the patterns we observed in late childhood and early adolescence were not consistent with maturation (alienation, aggression, and harm avoidance). Our findings are consistent with evidence from other samples indicating deviation from trait maturation in early adolescence (e.g., Denissen et al., 2013; Soto et al., 2011; van den Akker et al., 2014). Thus, theories of the processes underlying personality development, such as biological maturation (Costa & McCrae, 2006), identity consolidation (Roberts & Caspi, 2003), and investment in social roles (Roberts & Wood, 2006) appear less relevant to understanding the changes these traits underwent during the early adolescent period. Of course, it is also possible that studies using multiple assessment waves tightly spaced within a shorter developmental interval might also detect previously unanticipated nonlinear age effects.

Several developmental processes could potentially account for the patterns of deviation from maturation we detected in adolescence. Early adolescent personality development may be influenced by mechanisms that are themselves nonlinear, such as fluctuations in identity development processes of commitment versus explorations of different decisions and roles (Klimstra et al., 2010), or the experience of normative and nonnormative life events (Ludtke, Roberts, Trautwein, & Nagy, 2011). The new challenges evident in this period may interact with pre-existing individual differences to produce movement away from maturation in some youth, specifically those who are unprepared in terms of their existing skills and experience (e.g., Denissen et al., 2013) or intrinsic motivation (e.g., van den Akker et al., 2014) to respond ‘maturely’ to new challenges that first emerge in early adolescence. This is consistent with Caspi and Moffitt’s (1993) accentuation hypothesis, which posits that during times of environmental change characterized by less clear norms about how to respond to such change, pre-existing individual differences are intensified (e.g., more disinhibited youth deviate even further from maturation of conscientiousness). In particular, social changes prominent in this period may be particularly important sources of such challenges. The early adolescent period is often characterized by the onset of dating, increasing complexity and turmoil in peer relationships (Parker et al., 2006), and broadening of peer networks to include mixed-sex friendships (Molloy, Gest, Feinberg, & Osgood, 2014). These social changes come with considerable uncertainty regarding how best to respond and how to judge one’s success, and likely lean heavily on youth entering these challenges with relative deficits in personality maturation compared to their peers. Alternatively, changing norms among the peer group may influence trait development during this adolescent period towards engaging in less conscientious behaviors (Reitz et al., 2014).

Consistency with prior evidence regarding personality development

Previous studies have generally found aspects of positive emotionality to be relatively stable in adolescence (Blonigen et al., 2008; Donnellan et al., 2007; Johnson et al., 2007; Hopwood et al., 2011; Roberts et al., 2001; Robins et al., 2001). Our results generally corroborated the broad observation of overall mean-level stability of PEM traits across the late adolescent-to-early adulthood transition. However, they also revealed that mean-level change was more apparent for some facets of PEM than others; thus, our study contrasts with other studies conducted in other countries that report more modest change for changes in measures emphasizing sociability aspects of Extraversion (e.g., Klimstra et al., 2009). Well-being was the only PEM facet to exhibit an overall decline from ages 11 to 30, with the largest losses occurring from late childhood to middle adolescence. By contrast, adolescence appeared to be marked by increasing saliency of both social potency and achievement motivation, after which these traits exhibited much less mean-level change. Though achievement is a PEM scale in the MPQ, it is also linked with several aspects of conscientiousness in the five-factor model, so its increases from childhood through young adulthood were consistent with other studies that have shown increasing conscientiousness across this age range.

Prior studies have found that facets of NEM declined from adolescence to young adulthood (e.g., Donnellan et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2001), and our results place these observations in a somewhat broader developmental context. We found nonlinear change in NEM across that window, as well as different patterns of change in earlier developmental periods. Contrary to prior findings (e.g., Klimstra et al. 2009), stress reaction increased from late childhood to late adolescence for females before declining, whereas males declined rather smoothly from late childhood to age 30. Our findings are consistent, however, with evidence that internalizing problems increase in girls during this same developmental period (Costello et al., 2006). We replicated earlier findings of normative decreases in alienation and aggression.

We also uncovered more nuanced patterns of change for aspects of CON, while generally replicating the findings of prior studies that this trait increased across adolescence and early adulthood. First, for control and harm avoidance, the bulk of these increases occurred in the 20’s. By contrast, harm avoidance actually declined in from late childhood to late adolescence, consistent with evidence of increases in risk-taking and thrill-seeking behaviors during this period (Steinberg, 2007). Females also declined in control from late childhood to mid-adolescence and in the late 20’s; they increased on this scale only from late adolescence to young adulthood. Our results could be summarized as indicating that the observations of prior studies that CON increased from late adolescence to early adulthood were reasonably isolated to that period, as the trajectory of CON traits is different in other periods. Our observations of changes in CON traits in the early adolescent period were generally consistent with the studies that have focused on this particular period (Allik et al., 2004; Harden & Tucker-Drob, 2011; Johnson et al., 2007; McCrae et al., 2002).

Individual differences in personality development

Studies of personality development have tended to focus on mean-level changes over time (for exceptions, see Blonigen et al., 2008, Johnson et al., 2007, and Branje, van Lieshout, & Gerris, 2007). Our study showed clearly, however, that these mean-level changes do not apply to all individuals. For each scale, we found evidence for substantial individual variability in both the initial elevations of each trait and linear age-related change. Moreover, all scales had participants who displayed positive change and others who displayed negative change. This suggests that in addition to normative processes acting upon mean-level personality traits, other static or dynamic factors that differentiate among individuals act to produce deviation from the normative trends. The occurrence of important life events are one likely influence on these individual differences (Johnson et al., 2007; Roberts et al., 2003), such that differential timing, context, or psychological meaning of important transitional moments or developmental tasks (Hutteman et al., 2014) may act to produce different patterns of personality changes across individuals. Future research should focus on identifying which common life events are most powerful in this respect, as well as whether any show specificity for change in particular traits. Moreover, it will be important to understand whether common events or life transitions are associated with the same pattern of subsequent personality changes regardless of the timing of those events (e.g., early versus late pubertal onset), or if their impact on personality varies with timing. Finally, analytic models testing such questions must be able to provide evidence that such life events are causally impacting subsequent personality change, rather than reflecting pre-existing trait differences between those who do and do not experience the event(s) or trait change that occurs prior to and perhaps facilitates entry into the life event (Luhmann et al., 2014). In addition to exploring life events, it is possible that dynamic contextual influences in the social environment, as well as static individual difference factors, may help to account for differential personality development trajectories.

Sex differences in personality development

Contrary to earlier claims that there are no sex differences in patterns of mean-level personality change (Caspi et al., 2005), we found differential age-related change for males and females on many traits, although this varied across traits. First, there were no indications of sex differences in development of any of the four PEM scales. Our findings for social potency are in contrast to meta-analytic work showing that adult males score higher than females on assertiveness facets of PEM (McCrae & Costa, 1987; Lynn & Martin, 1997). Second, for the scales reflecting NEM, there were substantial sex differences in both the overall level and pattern of change. At age 11, females showed slightly lower stress reaction than males, but they increased rapidly while males remained relatively stable, a difference that persisted even when both sexes increased again in the late 20’s. These findings are consistent with evidence that adult women are higher than men on self-reported NEM, especially its anxiety elements (e.g., McCrae & Costa, 1987; Lynn & Martin, 1997). Thus, there appeared to be factors unique to females that acted to increase their levels of negative mood in adolescence and early adulthood. At age 11, males were higher than females in alienation, but decreased more rapidly, suggesting greater developmental press on males to decline in their mistrust and distance from others. There were no differences in change parameters for aggression, but males exhibited large elevations relative to females in aggression across the entire developmental period from childhood through young adulthood, suggesting that the factors accounting for the large sex differences in aggression across the lifespan are already present in late childhood.

Finally, for CON traits, the most marked sex differences were in overall elevation, as the differences in change parameters we observed were modest in comparison to those for NEM traits. Females had higher mean levels of CON traits across the entire developmental window covered by our assessments, with one exception. Males were slightly lower than females at age 11 in traditionalism, but they increased more rapidly, so the difference had disappeared by age 30. It appears that sex differences in CON traits were largely influenced by factors acting prior to age 11, with a modest influence of general maturational processes or new influences that became apparent later in the lifespan.

Study Limitations

Some aspects of our study design warrant caution in the degree to which our findings can be extrapolated to other methods and samples. First, personality was assessed using a self-report questionnaire only, and thus was subject to the well-known limitations of such measures. Very little is known about the extent to which the normative developmental changes documented for self-report measures of personality traits are corroborated by other measures of those constructs, including informant reports, behavioral samples, or laboratory/observational methods. Moreover, the interpretation of longitudinal trends is complicated when different informants or observations are used at different assessment points, making self-reports the most obvious method of choice for such questions. However, we acknowledge that confirmation from studies using other approaches would provide important additional information about the nature of personality development.

Second, our sample consisted of twin pairs and adoptive and biological siblings drawn from a particular geographic region and cohort (people born in Minnesota from the 1970’s to the 1990’s). Though it was quite representative of this population, it was primarily of European-American descent. Those participants who were adopted also had rather restricted demographic characteristics, as most were born in South Korea. Thus, we cannot speculate as to how our results would generalize to broader populations or those with different demographic characteristics. However, there is little evidence of personality trait differences between twins and non-twins (Johnson, Kruger, Bouchard, & McGue, 2002) or adoptees and non-adoptees (Keyes, Legrand, Iacono, & McGue, 2008).

Our analyses of individual differences in nonlinear change parameters were based on a smaller subset of the larger sample (approximately 2000 of the 5000 participants). Although this subset is still rather large in an absolute sense, the results of these analyses should be interpreted more cautiously than those that deal with the general pattern of nonlinear change evident in the sample as a whole. Finally, some scales were not assessed until age 14 (social potency, achievement, social closeness, traditionalism, absorption). Thus, we were unable to explore trait change in the earliest developmental period (ages 11 to 14) for these facets.

Conclusions and future directions

In this study, we evaluated personality development in specific (lower-order) aspects of personality over the critical developmental period from late childhood through early adulthood. Our results showed the importance of being able to model nonlinear as well as linear change in order to describe personality change accurately. Our findings corroborated, extended, and refined our previous understanding of personality development and emphasized the individual variability that surrounds the overall developmental patterns. Future research should investigate more fully the factors involved in producing nonlinear trends, as well as individual variability about these trajectories. Although we explored one such factor (sex), it is likely that an array of dynamic influences (e.g., socio-contextual factors) and discrete and normative life events (e.g., the onset of puberty; dating) may shed light on the contexts that impinge on individuals to constrain or expand their patterns of personality functioning.

Supplementary Material

Figure 2.

Model-derived change trajectories for NEM traits (T scores) in males and females

Figure 4.

Model-derived change trajectories for Absorption (T scores) in males and females

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by USPS grants R01 DA034606, R37 DA005147, R01 DA013240, R01 AA09367, and R01 MH066140. Brian M. Hicks was supported by K01 DA025868. Daniel M. Blonigen was supported by a Career Development Award-2 from the VA Office of Research and Development (Clinical Sciences Research & Development). Wendy Johnson holds a Research Council of the United Kingdom fellowship.

Contributor Information

C. Emily Durbin, Michigan State University.

Brian M. Hicks, University of Michigan

Daniel M. Blonigen, Department of Veterans Affairs, Palo Alto Health Care System

Wendy Johnson, University of Edinburgh.

William G. Iacono, University of Minnesota

Matt McGue, University of Minnesota.

References

- Allik J, Laidra K, Realo A, Pullmann H. Personality development from 12 to 18 years of age: Changes in mean levels and structure of traits. European Journal of Personality. 2004;18(6):445–462. doi: 10.1002/per.524. [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Adolescent storm and stress, reconsidered. American Psychologist. 1999;54(5):317–326. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.5.317. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.54.5.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnett JJ. Emerging adulthood - A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist. 2000;55(5):469–480. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.55.5.469. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Carlson MD, Hicks BM, Krueger RF, Iacono WG. Stability and change in personality traits from late adolescence to early adulthood: A longitudinal twin study. Journal of Personality. 2008;76(2):229–266. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00485.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00485.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Branje SJT, Van Lieshout CFM, Gerris JRM. Big Five personality development in adolescence and adulthood. European Journal of Personality. 2007;21(1):45–62. doi: 10.1002/per.596. [Google Scholar]

- Buhrmester D. Need fulfilment, interpersonal competence, and the developmental contexts of early adolescent friendship. In: Bukowski WM, Newcomb AF, Hartup WW, editors. The company they keep: Friendship in childhood and adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 158–185. [Google Scholar]

- Caspi A, Roberts BW, Shiner RL. Personality development: Stability and change. Annual Review of Psychology. 2005;56:453–484. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Stability and change in personality assessment: The Revised NEO Personality Inventory in the year 2000. Journal of Personality Assessment. 1997;68(1):86–94. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_7. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa6801_7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa PT, McCrae RR. Age changes in personality and their origins: Comment on Roberts, Walton, and Viechtbauer (2006) Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(1):26–28. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.26. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costello EJ, Erkanli A, Angold A. Is there an epidemic of child or adolescent depression? Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2006;47:1263–1271. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01682.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Fruyt F, Bartels M, Van Leeuwen KG, De Clercq B, Decuyper M, Mervielde I. Five types of personality continuity in childhood and adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2006;91(3):538–552. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.538. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.91.3.538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Haan AD, Deković M, den Akker AL, Stoltz SE, Prinzie P. Developmental personality types from childhood to adolescence: Associations with parenting and adjustment. Child Development. 2013;84(6):2015–2030. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denissen JJA, van Aken MAG, Penke L, Wood D. Self-regulation underlies temperament and personality: An integrative developmental framework. Child Development Perspectives. 2013;7(4):255–260. [Google Scholar]

- Donnellan MB, Conger RD, Burzette RG. Personality development from late adolescence to young adulthood: Differential stability, normative maturity, and evidence for the maturity-stability hypothesis. Journal of Personality. 2007;75(2):237–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00438.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2007.00438.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson EH. Identity: Youth and crisis. Norton; New York: 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Fraley RC, Roberts BW. Patterns of continuity: A dynamic model for conceptualizing the stability of individual differences in psychological constructs across the life course. Psychological Review. 2005;112(1):60–74. doi: 10.1037/0033-295X.112.1.60. doi: 10.1037/0033-295x.112.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall GS. Adolescence: Its psychology and its relations to physiology, anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education. 1-2. Appleton-Century-Crofts; New York: 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Hamburg BA. Early adolescence: A specific and stressful stage of the life cycle. In: Coelho DA, Hamburg DA, Adams JE, editors. Coping and adaption. Basic Books; New York: 1974. pp. 102–124. [Google Scholar]

- Harden KP, Tucker-Drob EM. Individual differences in the development of sensation seeking and impulsivity during adolescence: Further evidence for a dual systems model. Developmental Psychology. 2011;47(3):739–746. doi: 10.1037/a0023279. doi: 10.1037/a0023279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood CJ, Donnellan MB, Blonigen DM, Krueger RF, McGue M, Iacono WG, Burt SA. Genetic and environmental influences on personality trait stability and growth during the transition to adulthood: A three-wave longitudinal study. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100(3):545–556. doi: 10.1037/a0022409. doi: 10.1037/a0022409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutteman R, Henneke M, Orth U, Reitz AK, Specht J. Developmental tasks as a framework to study personality development in adulthood and old age. European Journal of Personality. 2014;28:267–278. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JJ, Bogg T, Walton KE, Wood D, Harms PD, Lodi-Smith J, Roberts BW. Not all Conscientiousness scales change alike: A multimethod, multisample study of age differences in the facets of Conscientiousness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96(2):446–459. doi: 10.1037/a0014156. doi: 10.1037/a0014156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Hicks BM, McGue M, Iacono WG. Most of the girls are alright, but some aren't: Personality trajectory groups from ages 14 to 24 and some associations with outcomes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;93(2):266–284. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.266. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.93.2.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson W, Krueger RF, Bouchard TJ, Jr., McGue M. The personalities of twins: Just ordinary folks. Twin Research. 2002;5:125–131. doi: 10.1375/1369052022992. doi: 10.1375/136905202292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes MA, Malone SM, Elkins IJ, Legrand LN, McGue M, Iacono WG. The Enrichment Study of the Minnesota Twin Family Study: Increasing the Yield of Twin Families at High Risk for Externalizing Psychopathology. Twin Research and Human Genetics. 2009;12(5):489–501. doi: 10.1375/twin.12.5.489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keyes M, Legrand LN, Iacono WG, McGue M. The mental health of US adolescents adopted in infancy. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2008;162(5):419–425. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.5.419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra TA, Hale WW, III, Raaijmakers AW, Branje SJT, Meeus WHJ. Maturation of personality in adolescence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2009;96(4):898–912. doi: 10.1037/a0014746. doi: 10.1037/a0014746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra TA, Hale WW, Raaijmakers QA, Branje SJ, Meeus WH. A developmental typology of adolescent personality. European Journal of Personality. 2010;24(4):309–323. [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra TA, Luyckx K, Hale WW, Frigns T, van Lier PAC, Meeus WHJ. Short-term fluctuations in identity: Introducing a micro-level approach to identity formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2010;99:191–202. doi: 10.1037/a0019584. doi: 10.1037/a0019584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson RW, Moneta G, Richards MH, Wilson S. Continuity, stability, and change in daily emotional experience across adolescence. Child Development. 2002;73(4):1151–1165. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00464. doi 10.1111/1467-8624.00464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehnart J, Neyer FJ, Eccles J. Long-term effects of social investment: The case of partnering in young adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2010;78(2):639–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-6494.2010.00629.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ludtke O, Roberts BW, Trautwein U, Nagy G. A random walk down university avenue: Life paths, life events, and personality trait change at the transition to university life. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;101(3):620–637. doi: 10.1037/a0023743. doi 10.1037/a0023743. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luhmann M, Orth U, Specht J, Kandler C, Lucas RE. Studying changes in life circumstances and personality: It’s about time. European Journal of Personality. 2014;28:256–266. [Google Scholar]

- Marshall WA, Tanner JM. Puberty. In: Falkner F, Tanner JM, editors. Human growth. II. Postnatal growth. Plenum Press; New York: 1986. pp. 171–209. [Google Scholar]

- McAdams DP, Olson BD. Personality development: Continuity and change over the life course. Annual Review of Psychology. 2010;61:517–542. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.093008.100507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrae RR, Costa PT, Terracciano A, Parker WD, Mills CJ, De Fruyt F, Mervielde I. Personality trait development from age 12 to age 18: Longitudinal, cross-sectional, and cross-cultural analyses. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2002;83(6):1456–1468. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.83.6.1456. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGue M, Keyes M, Sharma A, Elkins I, Legrand L, Johnson W, Iacono WG. The environments of adopted and non-adopted youth: Evidence on range restriction from the Sibling Interaction and Behavior Study (SIBS) Behavior Genetics. 2007;37(3):449–462. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. doi: 10.1007/s10519-007-9142-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molloy LE, Gest SD, Feinberg ME, Osgood DW. Emergence of mixed-sex friendship groups during adolescence: Developmental associations with substance use and delinquency. Developmental Psychology. 2014;50(11):2449–2461. doi: 10.1037/a0037856. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neyer FJ, Asendorpf JB. Personality-relationship transaction in young adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81(6):1190–1204. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker JG, Rubin KH, Erath SA, Wojslawowicz JC, Buskirk AA. Peer relationships, child development, and adjustment: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology, Vol 1: Theory and method. 2nd Wiley & Sons; Hoboken, N.J.: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Patrick CJ, Curtin JJ, Tellegen A. Development and validation of a brief form of the Multidimensional Personality Questionnaire. Psychological Assessment. 2002;14:150–163. doi: 10.1037//1040-3590.14.2.150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullmann H, Raudsepp L, Allik J. Stability and change in adolescents' personality: A longitudinal study. European Journal of Personality. 2006;20(6):447–459. doi: 10.1002/per.611. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR. The young adult years: Diversity, structural change, and feritility. Demography. 1991;28(4):493–512. doi: 10.2307/2061419. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitz AK, Zimmerman J, Hutteman R, Specht J, Neyer FJ. How peers make a difference: The role of peer groups and peer relationships in personality development. European Journal of Personality. 2014;28:279–288. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Caspi A. The cumulative continuity model of personality development: Striking a balance between continuity and change in personality traits across the life course. In: Staudinger RM, Lindenberger U, editors. Understanding Human Development: Lifespan Psychology in Exchange with Other Disciplines. Kluwer Academic Publishers; Dordrecht, NL: 2003. pp. 183–214. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Caspi A, Moffitt TE. The kids are alright: Growth and stability in personality development from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2001;81(4):670–683. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.81.4.670. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Walton KE, Viechtbauer W. Patterns of mean-level change in personality traits across the life course: A meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychological Bulletin. 2006;132(1):1–25. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.132.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts BW, Wood D. Personality development in the context of the neo-socioanalytic model of personality. In: Mroczek DK, Little TD, editors. Handbook of personality development. Erlbaum; Mahwah, NJ: 2006. pp. 11–39. [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RW, Wood D, Smith JL. Evaluating Five-Factor theory and social investment perspectives on personality trait development. Journal of Research in Personality. 2005;39:166–184. [Google Scholar]

- Robins RW, Fraley RC, Roberts BW, Trzesniewski KH. A longitudinal study of personality change in young adulthood. Journal of Personality. 2001;69(4):617–640. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.694157. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.694157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segalowitz SJ, Davies PL. Charting the maturation of the frontal lobe: An electrophysiological strategy. [Article] Brain and Cognition. 2004;55(1):116–133. doi: 10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00283-5. doi: 10.1016/s0278-2626(03)00283-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiner R, Caspi A. Personality differences in childhood and adolescence: measurement development, and consequences. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines. 2003;44(1):2–32. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00101. doi: 10.1111/1469-7610.00101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soto CJ, John OP, Gosling SD, Potter J. Age differences in personality traits from 10 to 65: Big Five domains and facets in a large cross-sectional sample. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2011;100(2):330–348. doi: 10.1037/a0021717. doi: 10.1037/a0021717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steinberg L. Risk taking in adolescence: New perspectives from brain and behavioral science. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2007;16:55–59. [Google Scholar]