Abstract

We sought to determine 1) the influence of adiposity on thermoregulatory responses independently of the confounding biophysical factors of body mass and metabolic heat production (Hprod); and 2) whether differences in adiposity should be accounted for by prescribing an exercise intensity eliciting a fixed Hprod per kilogram of lean body mass (LBM). Nine low (LO-BF) and nine high (HI-BF) body fat males matched in pairs for total body mass (TBM; LO-BF: 88.7 ± 8.4 kg, HI-BF: 90.1 ± 7.9 kg; P = 0.72), but with distinctly different percentage body fat (%BF; LO-BF: 10.8 ± 3.6%; HI-BF: 32.0 ± 5.6%; P < 0.001), cycled for 60 min at 28.1 ± 0.2°C, 26 ± 8% relative humidity (RH), at a target Hprod of 1) 550 W (FHP trial) and 2) 7.5 W/kg LBM (LBM trial). Changes in rectal temperature (ΔTre) and local sweat rate (LSR) were measured continuously while whole body sweat loss (WBSL) and net heat loss (Hloss) were estimated over 60 min. In the FHP trial, ΔTre (LO-BF: 0.66 ± 0.21°C, HI-BF: 0.87 ± 0.18°C; P = 0.02) was greater in HI-BF, whereas mean LSR (LO-BF 0.52 ± 0.19, HI-BF 0.43 ± 0.15 mg·cm−2·min−1; P = 0.19), WBSL (LO-BF 586 ± 82 ml, HI-BF 559 ± 75 ml; P = 0.47) and Hloss (LO-BF 1,867 ± 208 kJ, HI-BF 1,826 ± 224 kJ; P = 0.69) were all similar. In the LBM trial, ΔTre (LO-BF 0.82 ± 0.18°C, HI-BF 0.54 ± 0.19°C; P < 0.001), mean LSR (LO-BF 0.59 ± 0.20, HI-BF 0.38 ± 0.12 mg·cm−2·min−1; P = 0.04), WBSL (LO-BF 580 ± 106 ml, HI-BF 381 ± 68 ml; P < 0.001), and Hloss (LO-BF 1,884 ± 277 kJ, HI-BF 1,341 ± 184 kJ; P < 0.001) were all greater at end-exercise in LO-BF. In conclusion, high %BF individuals demonstrate a greater ΔTre independently of differences in mass and Hprod, possibly due to a lower mean specific heat capacity or impaired sudomotor control. However, thermoregulatory responses of groups with different adiposity levels should not be compared using a fixed Hprod in watts per kilogram lean body mass.

Keywords: adiposity, biophysics, heat balance, sweating, temperature regulation

according to the world health organization (WHO), a person with excess body fat is more susceptible to greater levels of heat strain during exercise relative to a leaner individual by virtue of the insulative properties of fat tissue reducing heat dissipation from the skin (27). As such, it is proposed that less heat can be produced per unit body mass before core temperature increases by a given magnitude (27). While this notion has important public health implications since some physical activity guidelines potentially discourage exercise in overweight/obese individuals during bouts of warm weather, it is also an essential consideration for physiologists wishing to assess the independent influence of factors such as age (13, 36), injury (31), and disease (10, 22, 39) on changes in core temperature and sweating during exercise. As these study types almost always adopt a between-group experimental design, it must be ensured that the selected exercise intensity does not lead to systematic differences in thermoregulatory responses between groups secondary to disparities in metabolic heat production (Hprod) and/or the evaporative requirement for heat balance (Ereq) (7).

A recent series of studies from our laboratory has demonstrated that changes in core temperature should be compared between groups of dissimilar body size using an exercise intensity that elicits a fixed Hprod per unit total body mass (in W/kg TBM) (8), whereas whole body sweat losses (in g/min) and local sweat rates (in mg·cm−2·min−1) should be compared using a fixed Hprod (in W and W/m2, respectively) (8, 15, 38), due to its predominant contribution to Ereq (23). The observation of any subsequent differences in core temperature and/or sweating between groups can then be confidently attributed to an independent influence of the factor under investigation as opposed to an underlying bias arising from the experimental design. However, whether Hprod should be further adjusted to account for any differences in body fat that often occur between experimental groups, particularly those with different diseases, has not yet been determined.

While the lower specific heat of fat (2.97 kJ·kg−1·°C−1) relative to lean mass (3.66 kJ·kg−1·°C−1) should theoretically lead to a greater temperature change for a given amount of heat energy stored inside the body, a 20% difference in fat mass only leads to a minor difference (∼3-5%) in mean specific heat of the total body (17). However, it is also possible that due to its low thermal conductivity, fat mass may not fully contribute to the total body mass “heat sink” (16). The insulative properties of subcutaneous fat could also impair skin surface heat loss (3), but probably only in cooler environments (19). And while “core-to-shell” heat transfer primarily occurs convectively via the bloodstream, there appears little reason to suspect body fat interferes with sweat production and/or evaporation.

All previous studies examining the role of body fatness on thermoregulatory responses during exercise in a compensable environment are apparently confounded by differences in total body mass, Hprod, and/or Ereq between lean and obese groups. For example, Limbaugh et al. (29) recently reported similar changes in core temperature between groups with a low (11%) and moderate (23%) percentage body fat (%BF) cycling at a fixed external workload (66 W) and therefore presumably very similar absolute rates of Hprod. However, since total body mass was vastly different (78.5 ± 9.4 vs. 91.9 ± 14.9 kg) between groups (29), Hprod in watts per kilogram would have been lower in the higher body fat group, which potentially masked any thermoregulatory impairments in the higher fat group. A classic study by Bar-Or et al. (4) reported a “higher heat strain” in obese (31% BF) compared with lean (15% BF) women during treadmill walking at 4.8 km/h with a 5% grade, after observing a greater whole body sweat rate despite similar changes in rectal temperature. However, the additional energetic cost of carrying the much greater body mass of the obese group (90.5 vs. 51.6 kg) would have elicited a greater Ereq and therefore a greater biophysical requirement for whole body sweating unrelated to fat per se.

It has been proposed that the supposed confounding influence of %BF on thermoregulatory responses can be eliminated by selecting an exercise intensity that elicits the same Hprod per unit lean body mass (W/kg LBM) (16). However, if %BF does not substantially influence the maintenance of core body temperature during exercise, such an approach would inadvertently lead to systematically greater sweat rates in lean individuals due to a greater Ereq (8, 15, 24), and greater changes in core temperature due to a greater Hprod per kilogram total body mass (8).

The first aim of the present study was to assess for the first known time whether large differences in %BF truly alter changes in core temperature and thermoregulatory sweating during exercise in a compensable environment by recruiting two independent groups matched for total body mass and body surface area but vastly different in %BF, and prescribing an exercise intensity to elicit the same absolute Hprod and therefore simultaneously the same Hprod in watts per kilogram, and Ereq in watts and watts per square meter. The second aim was to assess the utility of a fixed Hprod per unit lean body mass (in W/kg LBM) for the comparison of thermoregulatory responses between groups differing greatly in %BF. It was hypothesized that after matching low (∼10%) and high (>30%) body fat participants for total body mass, BSA, age, and sex, changes in core temperature and sweating during exercise would be 1) similar, at an absolute fixed Hprod (550 W) despite large differences in Hprod per unit lean body mass, and 2) significantly greater in the low body fat group at the same Hprod per lean body mass (7.5 W/kg LBM) due to a greater total Hprod per unit total mass and greater corresponding Ereq.

METHODS

Participants

Using G*Power 3 software [Heinrich-Heine-Universität Düsseldorf, Germany (14)], a power calculation was performed with an α of 0.05, a β of 0.20, and an effect size of 1.10, determined from the smallest significant difference in the primary outcome variable (ΔTre) from previous studies employing a similar protocol (8, 24, 38). A minimum sample size of 9 individuals per group was determined; therefore, 18 [9 low BF, 10.7 ± 4.1% (LO-BF group); and 9 high BF, 32.2 ± 6.5% (HI-BF group)] healthy, nonsmoking, and normotensive Caucasian males volunteered for the study. Participants from the LO-BF and HI-BF group were specifically matched in pairs for total body mass (group means: LO-BF 87.8 ± 8.5 kg; HI-BF 89.4 ± 7.8 kg). All participants were similar in age (LO-BF 24 ± 2 yr; HI-BF 25 ± 6 yr) and refrained from the consumption of caffeine or alcohol and any form of strenuous exercise 24 h prior to the experimental trials. Prior to testing, the Research Ethics Board at the University of Ottawa and the University of Sydney approved the experimental protocol. The eligible participants completed a Physical Activity Readiness Questionnaire (PAR-Q), American Heart Association questionnaire (AHA), and informed consent form before experimentation and were excluded if they had cardiovascular or metabolic health disorders. The first seven LO-BF/HI-BF pairs of participants (pairs 1–7; Table 1) were tested at the University of Ottawa, and an additional two LO-BF/HI-BF pairs of participants (pairs 8–9; Table 1) were tested in the Thermal Ergonomics Laboratory at the University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia, using the identical experimental protocol and instrumentation as described below.

Table 1.

Mean physical characteristics for low (LO-BF) and high (HI-BF) body fat participants matched in pairs for body mass

| Body Mass, kg |

Body Fat, % |

LBM, kg |

BSA, m2 |

Cp, kJ·kg−1·°C−1 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pair No. | LO-BF | HI-BF | LO-BF | HI-BF | LO-BF | HI-BF | LO-BF | HI-BF | LO-BF | HI-BF |

| 1 | 94.8 | 94.7 | 9.1 | 37.8 | 86.2 | 58.9 | 2.19 | 2.18 | 3.66 | 3.43 |

| 2 | 100.0 | 99.5 | 15.3 | 32.6 | 84.7 | 67.9 | 2.25 | 2.09 | 3.67 | 3.50 |

| 3 | 83.6 | 85.2 | 8.5 | 27.0 | 76.5 | 62.2 | 2.06 | 1.97 | 3.62 | 3.52 |

| 4 | 80.6 | 84.2 | 4.9 | 24.4 | 77.0 | 63.6 | 2.07 | 2.02 | 3.69 | 3.54 |

| 5 | 83.9 | 85.1 | 14.8 | 42.8 | 71.5 | 48.7 | 2.02 | 2.00 | 3.63 | 3.41 |

| 6 | 94.5 | 97.5 | 14.2 | 28.0 | 81.1 | 71.0 | 2.18 | 2.19 | 3.62 | 3.51 |

| 7 | 77.3 | 79.3 | 7.8 | 33.0 | 71.3 | 53.1 | 1.90 | 1.98 | 3.63 | 3.48 |

| 8 | 98.8 | 100.4 | 12.0 | 31.9 | 86.9 | 68.4 | 2.25 | 2.20 | 3.65 | 3.50 |

| 9 | 84.6 | 84.8 | 10.2 | 30.9 | 76.0 | 58.6 | 2.09 | 1.94 | 3.65 | 3.52 |

| Mean | 88.7 | 90.1 | 10.8 | 32.0* | 79.0* | 61.4 | 2.11 | 2.06 | 3.65* | 3.49 |

| SD | 8.4 | 7.9 | 3.6 | 5.6 | 6.0 | 7.4 | 0.12 | 0.10 | 0.02 | 0.04 |

| P value | 0.72 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.36 | <0.001 | |||||

Body surface area (BSA) estimated using the equation of DuBois and DuBois (11a). Body fat % and lean body mass (LBM) were measured using dual-energy X-ray absorptiometry (DXA). Mean specific heat of the body (Cp) was subsequently estimated by assigning different specific heat capacity values to the various components of lean mass (i.e., muscle, skin, blood, white matter, gray matter, eye, nerve, lens, and cartilage), fat mass, and bone mass (17).

Significantly greater value (P ≤ 0.05). See Protocol for specific description of FHP trial and LBM trial.

Instrumentation

Thermometry.

Rectal temperature (Tre) was measured with a pediatric thermistor probe (Mon-a-therm General Purpose Temperature Probe; Mallinckrodt Medical) inserted to a minimum of 12 cm past the anal sphincter. Skin temperatures (Tsk) were measured at eight separate sites: forehead (Tfh), triceps (Ttri), shoulder (Tsh), scapula (Tscap), chest (Tchest), back of the hand (Thand), thigh (Tquad), and calf (Tcalf), using T-type (copper/constantan) thermocouples. Mean Tsk was calculated using a weighted average of each site (35):

| (1) |

Whole body sweat rate.

Whole body sweat rate (WBSR) was estimated by measuring the participant's body mass in triplicate with a platform scale (Sartorius, New York) immediately before the start of exercise, then immediately after completing the 15th, 30th, 45th, and 60th minute of exercise. The changes in body mass between each weigh-in, minus saliva, and respiratory and metabolic mass losses, were divided by 15 min, yielding WBSR values in grams per minute.

Local sweat rate.

Local Sweat Rate (LSR) was estimated by placing a ventilated sweat capsule on the forearm and upper back. Anhydrous air at a flow rate of 1.80 l/min passed through the capsules and over the skin surface. A factory-calibrated capacitance hygrometer (HMT333, Vaisala, Vantaa, Finland) was used to measure the effluent air expressed as relative humidity (%). The LSR, expressed as milligrams per centimeters squared per minute, was calculated using flow rate (l/min), ambient air temperature (°C), and relative humidity (%) of the effluent air, and sweat capsule surface area (4.0 cm2).

Partitional calorimetry.

Partitional calorimetry was used to calculate heat balance values as per convention (in W/m2), but are presented in watts or watts per kilogram as appropriate. Due to minimal clothing (i.e., light cotton shorts and running shoes and cotton socks), dry insulation and the evaporative resistance of clothing were considered negligible.

Metabolic energy expenditure (M) was estimated using indirect calorimetry throughout exercise. Minute-average values for oxygen consumption (V̇o2) in liters per minute and respiratory exchange ratio (RER) were measured using a Metabolic Cart (Vmax Encore Carefusion). Values for M were estimated using (33):

| (2) |

where ec is the caloric energy equivalent per liter of oxygen for the oxidation of carbohydrates (21.13 kJ) and ef is the caloric energy equivalent per liter of oxygen for the oxidation of fat (19.62 kJ).

The rate of external work (W) was regulated directly with a semirecumbent cycle ergometer (Corival Recumbent, Lode, Groningen, Netherlands). Metabolic heat production (Hprod) was subsequently calculated by subtracting W (in W/m2) from M.

Convective heat exchange (C) was estimated using:

| (3) |

where Tsk is the weighted mean temperature of the skin surface (in°C) and Ta is the mean air temperature (in°C) equal to surrounding air temperature; and hc is the convective heat transfer coefficient (in W·m−2K−1) for a seated individual facing an air velocity (v) between 0.2 and 4.0 m/s (32):

| (4) |

Radiative (R) heat exchange at the skin surface was calculated using:

| (5) |

where Tr is mean radiant temperature (in°C; assumed to be equal to Ta since there were no radiant heat sources present), and hr is the radiant heat transfer coefficient:

| (6) |

where ε is the emissivity of the body (∼1.0); σ is the Stefan-Boltzmann constant (5.67·10−8 W·m2·K−4); BSAr/BSA is the effective radiant surface area (ND), equal to 0.70 (27); and Tr is the mean radiant temperature, assumed to be equivalent to Ta (°C).

Respiratory heat loss by convection (Cres) and evaporation (Eres) were calculated using:

| (7) |

where Hprod is metabolic heat production, Pa is the partial pressure of water vapor in ambient air (in kPa), and ta is the air temperature in (°C).

The evaporative requirement for heat balance (Ereq) was determined using:

| (8) |

where each heat balance parameter was converted (from W/m2 to W) by multiplying by BSA.

Net cumulative heat loss (Hloss) during the 60-min exercise bout was estimated using:

| (9) |

where each heat balance parameter was converted (from W to kJ) by multiplying by 3,600; and the cumulative amount of evaporative heat loss from the skin (Esk) was estimated using:

| (10) |

where WBSL is the cumulative whole body sweat loss over the 60-min exercise period (in g) after corrections for saliva, and metabolic and respiratory mass losses; and 2.426 is the latent heat of vaporization of sweat (in kJ per g of sweat) (40). Saliva was captured by the mouthpiece assembly, which was then emptied and weighed at the end of the trial. Respiratory mass loss was calculated by first estimating respiratory heat loss via evaporation (Eres) (see Eres component of Eq. 7). Eres was converted (to W), then multiplied by the number of seconds in the exercise bout (3,600 s) and divided by the latent heat of vaporization of water (40) to yield respiratory mass loss (in g). Metabolic mass loss (mr) was calculated using (26):

| (11) |

where t is time in seconds, V̇o2 is oxygen consumption in liters per minute, and RER is the respiratory exchange ratio.

Experimental Design

All participants completed one preliminary trial and two experimental trials. All paired participants completed the experimental trials at the same time of day to prevent any influence of circadian rhythm variation. It is assumed that all participants were not heat acclimatized. For the first 7 LO-BF/HI-BF pairs of participants tested in Ottawa, no seasonal acclimatization is evident for individuals of this age residing in this geographical region (3). For the additional 2 LO-BF/HI-BF pairs of participants tested in Sydney, these data were collected in the southern hemisphere winter (July/August) during which time the average daily maximum ambient temperature was ∼17°C. To confirm participants were euhydrated prior to each experimental trial, they were instructed to drink plenty of fluids the night before. On the day of testing, participants ingested an additional 500 ml of water and prior to exercise participants provided a urine sample, which was analyzed for urine specific gravity (USG) using a refractometer (Reichert TS 400, Depew, NY). All participants were required to have a USG below 1.020 to ensure euhydration before exercise (2, 34).

Environmental conditions during each experimental trial were an air temperature (Ta) of 28.1 ± 0.2°C, relative humidity (RH) of 26 ± 8% and an air velocity (v) of 0.8 m/s. The ambient conditions and the target rates of heat production were selected to ensure that the level of heat strain was physiologically compensable and the full evaporation of sweat was permitted in all participants. All participants exercised seminude in standardized shorts (dry insulation and evaporative resistance of clothing were considered negligible).

Protocol

In the preliminary trial, total body mass and height were measured with a platform scale and stadiometer, respectively. Body fat percentage (BF%) and lean body mass (LBM) were also measured using a Dual-Energy X-Ray Absorptiometry (DXA). Mean specific heat of the body (Cp) was estimated by assigning different specific heat capacity values to the various components of lean mass (i.e., muscle, skin, blood, white matter, gray matter, eye, nerve, lens, and cartilage), fat mass, and bone mass (17). Body surface area (BSA) was estimated using the equation of DuBois and DuBois (5). Subsequently, peak oxygen consumption (V̇o2 peak) was measured using a semirecumbent cycle ergometer involving a graded 16 min warm-up to determine the individualized workload required for each target heat production (8), which was followed by a short break, and then a maximal test where the external workload increased by 20 W every minute until physical exhaustion. The V̇o2 peak protocol followed the Canadian Society of Exercise Physiology guidelines (9).

In the experimental trials, after instrumentation, participants entered the climate-controlled room and were first seated for a 30-min baseline period. Afterwards, participants cycled for 60 min at an external workload that elicited 1) a fixed absolute heat production of 500 W (FHP trial), or 2) a fixed metabolic heat production of 7.5 W per kilogram of lean body mass (LBM trial). The initial workload was determined based on the target Hprod using the procedure described previously (8), with external workload adjusted slightly throughout if necessary. At 15-min intervals, the participant briefly (60 s) stopped to be weighed. Participants were not toweled down prior to each body mass measurement to avoid an overestimation of evaporative heat loss. Participants did not drink any fluid throughout exercise.

Statistical Analysis

All data were expressed as means ± SD and analyzed within exercise trials (i.e., FHP trial and LBM trial). A two-way mixed ANOVA was used to analyze the data, with the repeated factor of “time” [at five levels: 0, 15, 30, 45, and 60 min of exercise for ΔTre, Tsk, LSR (mean of upper-back and forearm); and at four levels: 0–15, 15–30, 30–45, 45–60 min of exercise for WBSR]; and the nonrepeated factor of “body fat group” (2 levels: high body fat and low body fat). Any significant interaction or main effect was subjected to an independent sample t-test to identify individual differences between body fat groups. Statistical significance was set at an alpha level of 0.05, and the probability of a Type 1 error was maintained at 5% for all post hoc comparisons using a Bonferroni correction. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism (v6.0, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Physical Characteristics

Mean participant characteristics for each mass-matched LO/HI-BF pair are presented in Table 1. By design, no differences in total body mass (P = 0.72) or body surface area (P = 0.36) were observed between LO-BF and HI-BF groups, but a significantly greater %BF was observed in the HI-BF group (P < 0.001). Consequently, lean body mass (P < 0.001) and specific heat capacity (P < 0.001) were greater in the LO-BF group. V̇o2 peak was also greater (P = 0.003) in the LO-BF (47.7 ± 7.2 ml·kg−1·min−1) compared with the HI-BF (37.8 ± 5.8 ml·kg−1·min−1) group.

External Workload, Heat Production, and Evaporative Requirements for Heat Balance (Ereq)

Average Hprod, Ereq, and external workload values for both trials are presented in Table 2. In the FHP trial, Hprod was, as intended, similar between groups in watts (P = 0.73), and therefore similar in watts per kilogram TBM (P = 0.89). However, Hprod in watts per kilogram LBM was significantly (P < 0.001) greater in the HI-BF group. Ereq was similar between LO-BF and HI-BF in watts (P = 0.92), and watts per square meter (P = 0.57). In parallel, external workload was the same between groups (P = 0.13).

Table 2.

Average external workload, metabolic heat production, evaporative heat balance requirements (Ereq) and relative exercise intensities for low (LO-BF) and high (HI-BF) body fat participant groups for exercise in the FHP trial and LBM trial

| Metabolic Heat Production |

Ereq |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| External Work, W | W/kg TBM | W/kg LBM | W | W/m2 | Relative Intensity, %V̇o2peak | |

| FHP trial | ||||||

| LO-BF | 99 ± 16 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 6.9 ± 0.7 | 420 ± 61 | 199 ± 24 | 44.1 ± 5.7 |

| HI-BF | 113 ± 22 | 6.1 ± 0.7 | 9.1 ± 1.3* | 423 ± 45 | 206 ± 25 | 58.4 ± 9.0* |

| P value | 0.13 | 0.89 | <0.001 | 0.92 | 0.57 | <0.001 |

| LBM trial | ||||||

| LO-BF | 111 ± 17* | 6.7 ± 0.7* | 7.5 ± 0.7 | 464 ± 42* | 220 ± 17* | 48.8 ± 7.0 |

| HI-BF | 80 ± 17 | 5.1 ± 0.6 | 7.6 ± 0.9 | 350 ± 62 | 169 ± 26 | 46.5 ± 4.4 |

| P value | 0.002 | <0.001 | 0.88 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.21 |

Values given are means (± SD) in watts (W), watts per unit total body mass (W/kg TBM), watts per unit lean body mass (W/kg LBM), and watts per unit surface area (W/m2). V̇o2peak, peak oxygen consumption.

Significantly greater value (P ≤ 0.05).

In the LBM trial, Hprod in watts per kilogram LBM was successfully maintained the same for both groups (P = 0.88). In parallel, external workload was significantly greater in the LO-BF group (P = 0.002), as were Hprod in watts and watts per kilogram TBM, and Ereq in watts and watts per square meter (all P < 0.001).

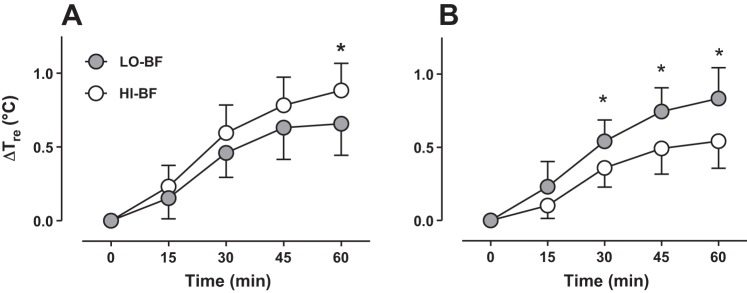

Core Temperature

In the FHP trial, after 60 min of exercise the change in Tre in the HI-BF (0.88 ± 0.18°C) group was greater (P = 0.022) compared with the LO-BF (0.66 ± 0.21°C) group (Fig. 1A). On the other hand, in the LBM trial, the change in Tre from rest to the end of exercise was greater (P < 0.001) in the LO-BF group (0.82 ± 0.18°C) compared with the HI-BF group (0.54 ± 0.19°C). A difference was observed between LO-BF and HI-BF after 30 min of exercise, which was subsequently sustained for the remainder of exercise (Fig. 1B).

Fig. 1.

Changes of rectal temperature (Tre) for low (gray symbols) and high (white symbols) body fat groups matched for total body mass and body surface area (BSA) during 60 min of exercise in the FHP trial (A) and the LBM trial (B). Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0.05 after Bonferroni correction. See Protocol for specific description of FHP trial and LBM trial.

Mean Skin Temperature

In the FHP trial, mean skin temperature throughout the 60-min exercise bout was similar (P = 0.64) between the HI-BF group (33.03 ± 0.92°C) and the LO-BF group (32.79 ± 1.17°C). Likewise, in the LBM trial mean skin temperature in the HI-BF group (32.59 ± 0.85°C) was not different (P = 0.53) from the LO-BF group (32.37 ± 0.57°C).

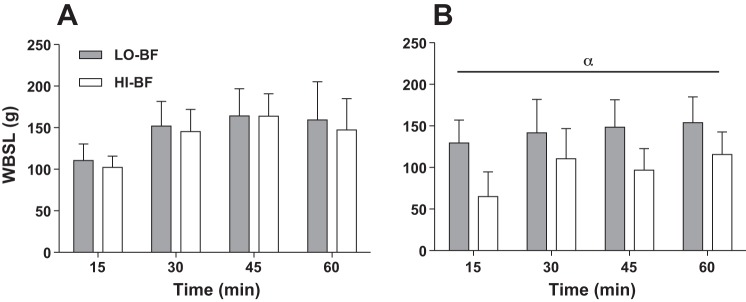

Whole Body Sweating

In the FHP trial, whole body sweat loss (WBSL) after 60 min of exercise in the LO-BF group (586 ± 82 ml) was very similar (P = 0.47) to the HI-BF group (559 ± 75 ml). Likewise, whole body sweat rate (WBSR) was similar (P = 0.93) between LO-BF and HI-BF groups throughout exercise (Fig. 2A). In the LBM trial, WBSL after 60 min of exercise in the LO-BF group (580 ± 106 ml) was much greater (P < 0.001) than the HI-BF group (381 ± 68 ml). Correspondingly, WBSR was greater in the LO-BF group throughout exercise (P < 0.001) relative to the HI-BF group (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Whole body sweat loss (WBSL) for low (gray bars) and high (white bars) body fat groups matched for total body mass and BSA during 60 min of exercise in the FHP trial (A) and the LBM trial (B). Error bars indicate SD. Alpha (α) indicates a main effect of %BF (P < 0.05).

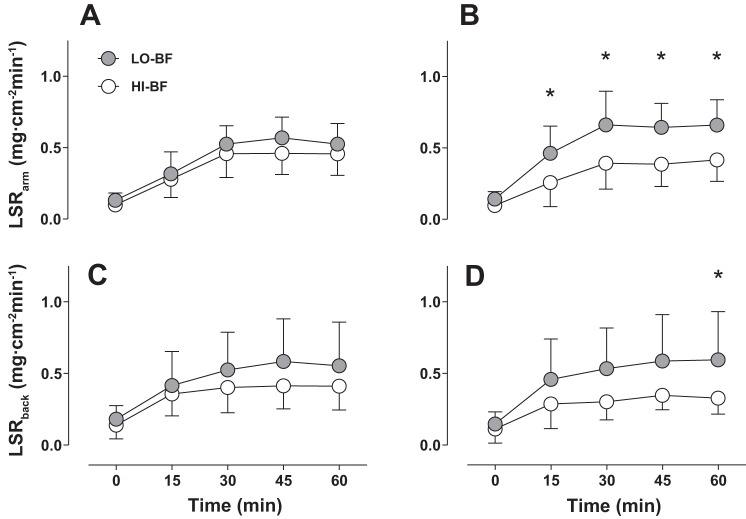

Local Sweat Rate (LSR)

In the FHP trial, LSR of both the forearm (P = 0.25) and upper back (P = 0.22) were similar between HI-BF and LO-BF groups throughout exercise (Fig. 3, A and B). At end-exercise, a similar upper back LSR of 0.55 ± 0.31 mg·cm−2·min−1 was observed in the LO-BF group compared with 0.41 ± 0.17 mg·cm−2·min−1 in the HI-BF group (P = 0.85). Similarly, end-exercise forearm LSR was not different between the LO-BF (0.52 ± 0.14 mg·cm−2·min−1) and HI-BF (0.46 ± 0.15 mg·cm−2·min−1) group (P = 0.99). In the LBM trial, LSR of the forearm and upper back were significantly greater in the LO-BF group after 15 min and 60 min of exercise, respectively (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3, C and D). At end-exercise, upper back LSR in the LO-BF group was 0.60 ± 0.34 mg·cm−2·min−1, compared with 0.33 ± 0.11 mg·cm−2·min−1 in the HI-BF group (P = 0.05). Likewise, end-exercise LSR of the forearm was 0.66 ± 0.18 mg·cm−2·min−1 in the LO-BF group compared with 0.42 ± 0.15 mg·cm−2·min−1 in the HI-BF group (P = 0.01)

Fig. 3.

Local sweat rate of the upper back and forearm for low (gray bars) and high (white bars) body fat groups matched for total body mass and BSA during 60 min of exercise in the FHP trial (A, C) and the LBM trial (B, D). Error bars indicate SD. *P < 0.05. n = 16 (8 HI-BF, 8 LO-BF).

Partitional Calorimetry

Mean heat balance parameters estimated using partitional calorimetry are given in Table 3. In the FHP trial, after 60 min of exercise, both cumulative Hprod (P = 0.73) and the cumulative sum (Hloss) of dry, evaporative and respiratory heat losses (i.e., C + R, Esk, and Cres + Eres) (P = 0.69) were similar between the LO-BF and HI-BF group (Table 3). In the LBM trial, after 60 min of exercise, cumulative Hprod (P < 0.001) and Hloss (P < 0.001) were greater in the LO-BF group compared with the HI-BF group. These differences in Hloss primarily arose due to differences in the potential evaporative heat loss from the skin (Esk); however, respiratory heat loss (Cres + Eres) was also greater in the LO-BF group due to the higher minute ventilation associated with the greater absolute V̇o2 required to sustain a fixed Hprod of 7.5 W/kg LBM in the leaner group.

Table 3.

Cumulative heat balance parameters estimated using partitional calorimetry for low (LO-BF) and high body fat (HI-BF) participant groups for 60-min exercise in the FHP trial and LBM trial

| Hprod, kJ | C + R, kJ | Cres + Eres, kJ | Esk, kJ | Hloss, kJ | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FHP trial | |||||

| LO-BF | 1,959 ± 224 | 282 ± 29 | 163 ± 19 | 1,421 ± 200 | 1,867 ± 208 |

| HI-BF | 1,994 ± 188 | 300 ± 46 | 171 ± 20 | 1,355 ± 183 | 1,826 ± 224 |

| P value | 0.73 | 0.34 | 0.42 | 0.47 | 0.69 |

| LBM trial | |||||

| LO-BF | 2,145 ± 213* | 296 ± 56 | 179 ± 27* | 1,408 ± 258* | 1,884 ± 277* |

| HI-BF | 1,676 ± 261 | 273 ± 48 | 143 ± 13 | 925 ± 166 | 1,341 ± 187 |

| P value | <0.001 | 0.33 | 0.02 | <0.001 | <0.001 |

Values given are means (± SD) in kilojoules (kJ). Hprod, metabolic heat production; C + R, sum of convective and radiative heat loss from the skin; Cres + Eres, combined heat loss via convection and evaporation from the respiratory tract; Esk, evaporative heat loss from the skin; Hloss, is the cumulative sum of all heat loss avenues [i.e.,(C + R)+ Cres + Eres + Esk].

Significantly greater value (P ≤ 0.05).

DISCUSSION

The present study assessed for the first known time the truly independent influence of large (3-fold) differences in body fat on thermoregulatory responses during exercise by eliminating any potential confounding effects of body mass, body surface area (BSA), and metabolic heat production (Hprod). The first primary finding was that at a fixed Hprod (FHP trial) of 550 W (6 W/kg TBM), high body fat levels (>30%BF) lead to significantly greater increases in core temperature relative to lower body fat levels (<12%BF), whereas no independent influence of adiposity was observed on time-dependent changes in whole body or local sweating responses. The second primary finding was that a fixed Hprod per unit lean body mass (LBM trial) of 7.5 W/kg LBM led to systematically greater changes in core temperature and whole body and local sweating in the LO-BF participant group due to large differences in Hprod per unit total body mass and concurrent evaporative heat balance requirements. This observation clearly demonstrates that the previously held concept that differences in body fat between independent groups should be accounted for by prescribing an exercise intensity that elicits a fixed Hprod per unit lean body mass, is flawed.

Despite the greater core temperature change in the HI-BF group in the FHP trial, similar whole body and local sweating responses (Figs. 2 and 3) were observed between groups. In parallel, the potential for net heat dissipation from the skin (Hloss) was also similar between HI-BF and LO-BF groups (Table 3). Since heat storage is the cumulative difference between heat production and heat dissipation, and heat production was fixed in the FHP trial (Table 2), the amount of heat energy stored inside the body during exercise would also have been similar. It therefore appears that from a biophysical perspective, the lower mean specific heat capacity in the HI-BF group (Table 1) may have been at least partially responsible for their greater change in core temperature. The fact that similar sweat rates were observed alongside dissimilar changes in core temperature also implies that large differences in %BF potentially disrupt the physiological control of sudomotor control. However, as we were unable to collect a full set of esophageal temperature data, we are unable to determine whether this arose due to a prolonged onset threshold and/or a blunted thermosensitivity. It has also been recently proposed that due to its low conductivity, fat mass may not contribute fully to an individual's “heat sink” (16). It follows that such a mechanism may also explain the greater rise in core temperature in the HI-BF group in the FHP trial. However, in view of the relatively small differences in core temperature despite large differences in fat mass (∼9 vs. ∼29 kg), this does not seem likely. Furthermore, if fat mass did not contribute to a person's heat sink, similar changes in core temperature would have been expected in the LBM trial, whereas lower values were observed in the HI-BF group. Nevertheless, future research should measure changes in fat tissue temperature to examine the extent of heat storage in this intermediate compartment.

Arguably the most important finding of the present study was that the relatively small influence of %BF on core temperature changes during exercise should clearly not be countered by prescribing a fixed Hprod in watts per kilogram LBM. This traditionally held notion (16, 28) is based on the rationale that during non-weight-bearing exercise (e.g., cycling), fat tissue functions primarily as surplus mass because it is not actively producing heat, so it is assumed that a rate of heat production based on lean body mass (i.e., metabolically active tissue) would remove any confounding influence of body fat differences. However, the LBM trial shows that large systematic differences in core temperature changes, and sweating responses, are generated by the much greater Hprod in watts per kilogram TBM (8) and Ereq (15, 24, 38) in the LO-BF group. While differences in specific heat capacity (Cp) secondary to differences in body composition may be responsible for the greater change in core temperature during exercise in the HI-BF group at fixed Hprod in watts per kilogram TBM (Fig. 1A), using a watts per kilogram LBM approach seems to overcorrect Hprod to a far greater extent (∼28%; Table 3) relative to differences in Cp (∼4–5%; Table 1). It follows that any studies fixing Hprod in watts per kilogram LBM may incorrectly conclude that individuals with a high %BF have a blunted sweating response relative to their leaner counterparts, whereas a lower sweat rate would simply be due to a systematic bias arising from the experimental design.

Several previous studies have concluded that adiposity influences thermoregulatory responses during exercise; however, all previous investigations have been apparently confounded by large differences in total body mass and/or Hprod between lean and nonlean (or obese) groups (1, 4, 12, 21). For example, Eijsvogels et al. (12) reported a greater core temperature in an obese (100.4 kg) compared with lean (69.6 kg) group, but any influence of differences in average specific heat between groups was likely masked by concomitant differences in Hprod in watts per kilogram TBM (which was not measured). On the other hand, the seminal study by Bar-Or et al. (4) reported a “higher heat strain” in their obese group by virtue of a greater sweat rate (obese 238 ± 33 ml·m−2·h−1, lean 207 ± 22 ml·m−2·h−1) during a weight-bearing exercise (walking), but Hprod and parallel evaporative heat balance requirements would have been much greater in the obese group as they had to carry a much greater mass (90 vs. 52 kg). Historically, some authors have contended that heat dissipation from the skin (Hloss) in obese individuals is impaired due to insulative properties (17) of adipose tissue (3, 5, 27, 30); however, the FHP trial in the present study demonstrates that this is not the case (Table 3). Indeed, peripheral vasodilation during exercise in the heat increases skin blood flow, and with internal core-to-skin heat transfer occurring mainly via the bloodstream, the subcutaneous layer of adipose tissue is likely bypassed, rendering its insulation properties in this case inconsequential (20).

In the present study, aerobic capacity (V̇o2 peak) was the only characteristic, in addition to %BF, that was different between LO-BF (47.7 ± 7.2 ml·kg−1·min−1) and HI-BF (37.8 ± 5.8 ml·kg−1·min−1) groups. However, we recently demonstrated similar changes in core temperature and sweating between aerobically fit (>60 ml·kg−1·min−1) and unfit (40–45 ml·kg−1·min−1) participants matched for total body mass and body surface area exercising at a fixed heat production in a physiologically compensable environment during both cycling (24) and treadmill running (38), despite large differences in relative exercise intensity (%V̇o2 peak). As such, the difference in core temperature between the HI-BF and LO-BF groups in the present study can only be ascribed to differences in adiposity, and not fitness or relative intensity.

Perspectives

The most immediate application of the present study is to the design of experiments assessing the influence of a between-group factor (e.g., age, disease, injury, etc.) on differences in thermoregulatory responses during exercise. In addition to our previous contributions to this topic (8, 24, 25, 38), we now demonstrate that a difference in body fat percentage of 20% between experimental groups may lead to systematically greater changes in core temperature in the group with a higher %BF unrelated to any other independent factor. For groups of unequal body mass and BSA, we have previously shown that the biophysical influence of these characteristics on changes in core temperature and local sweat rate can be eliminated by adjusting Hprod in watts per kilogram TBM and watts per square meter, respectively (7, 8). However, the present study clearly demonstrates that fixing Hprod in watts per kilogram LBM to account for any differences in %BF is not advisable since it will generate systematic differences in core temperature and both whole body and local sweating responses. Future studies should ensure that differences in %BF between groups are within ∼10%, as a disparity of this magnitude has been previously demonstrated to not alter thermoregulatory responses (24).

One implication of the higher adiposity in HI-BF group is a parallel difference in body volume and therefore estimated BSA values using the DuBois and DuBois formula of height and weight (5) secondary to the lower density of fat (0.9 kg/l) relative to muscle (1.1 kg/l). A ∼20% greater body fat would yield a BSA that is greater by ∼3% (18); therefore BSA in the HI-BF group is probably underestimated. However, since mean estimated BSA using the DuBois formula was slightly smaller in the HI-BF group (Table 1), a tissue density-related adjustment of BSA of ∼3% would actually bring mean group BSA values closer together.

Limitations and Future Studies

Cutaneous vascular conductance was not measured in the present study; as such potential differences in vascular control could not be assessed. Nevertheless, our partitional calorimetry estimations suggest that if any differences in skin blood flow control did arise as a function of %body fat, they were insufficient to alter skin surface heat transfer (Table 3). The present study assessed males between 4.9% to 42.8% body fat and 18 to 36 yr of age. Therefore, all findings are only relevant to males within that range, and may not apply to females, a more obese population (i.e., >40% body fat), or younger and older individuals. Future studies should consider examining potential interactions between sex, age, and adiposity on thermoregulatory responses to exercise. Another limitation is that the present study was conducted under physiologically compensable conditions, with the parameters selected to ensure the full evaporation of all sweat secreted onto the skin surface (thus permitting heat storage estimations via partitional calorimetry) and steady-state core temperatures toward the end of exercise. The completely independent influence of fat on thermoregulatory responses during uncompensable heat stress has not yet been determined. Under such conditions, Selkirk and McLellan (37) reported a greater heat tolerance in fitter and leaner individuals; however, differences in body mass and heat production existed between their groups in addition to the differences in fat mass and aerobic fitness. Furthermore, Deren et al. (11) reported that maximum skin wettedness may be altered due to a lower sweating efficiency arising from a lower sweat gland density in very high BSA individuals (∼2.7 m2) with a high fat percentage (∼28%). However, the exclusive roles of BSA and fat mass are unknown. Skin surface heat loss was not directly measured, but estimated via partitional calorimetry. While the environmental conditions were precisely measured and specifically selected to limit inaccuracies (i.e., high air flow and low ambient humidity to maximize the likelihood of complete evaporation of sweat from the skin surface), these calculations remain limited by inherent assumptions. However, it is known that evaporative efficiency is determined by the Ereq:Emax ratio (6), which was similar between groups in the present study (HI-BF 0.61 ± 0.29; LO-BF 0.57 ± 0.27; P = 0.79). Due to the exercise mode employed (i.e., semirecumbent cycling), a small proportion of BSA (∼0.15 m2) was covered by the ergometer seat, and while maximum evaporative heat loss would have consequently been reduced by ∼5–7%, this reduction would have been similar between the HI-BF and LO-BF groups as they were matched for body size and the conditions therefore remained similarly compensable. Finally, we cannot be certain there were no differences in heat acclimatization status between groups. However, this seems unlikely given our previous observation of no physiological heat adaptation in individuals within this age cohort (i.e., healthy college-aged males) attributed to the prevalent use of air conditioning in homes as well as work and exercise spaces (3).

Conclusions

At a fixed metabolic heat production, a greater change in core temperature was observed in nonlean participants (>30%BF) relative to a group of mass-matched lean individuals (<12%BF). However, whole body and local sweating responses as well as skin surface heat dissipation to the surrounding environment, estimated using partitional calorimetry, were not independently altered by large differences in adiposity. Furthermore, when prescribing an exercise intensity that generated a fixed heat production per unit lean body mass, as previously suggested in the literature to eliminate the supposed influence of fat mass on thermoregulatory responses, systematically greater changes in core temperature and sweating were observed in the lean group. Collectively, our findings further inform between-group experimental design demonstrating that when comparing thermoregulatory responses between independent groups, differences in %BF of more than 10%, which have been previously demonstrated to not alter thermoregulatory responses (24), should be avoided. Moreover, comparing thermoregulatory responses using a fixed heat production per unit lean mass, as opposed to per unit total body mass, is not advised as such an approach will potentially generate systematic differences in core temperature and sweating.

GRANTS

This research was supported by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) of Canada (no. 86143-2010, held by O. Jay). Funding for the metabolic cart and dew point sensor were provided by a Canadian Foundation for Innovation (CFI) Infrastructure Grant (co-applicant: O. Jay). G. B. Coombs was supported by a University of Ottawa Master's Scholarship. D. Filingeri was supported by Government of Australia Endeavour Postdoctoral Fellowship.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: S.M.D. and O.J. conception and design of research; S.M.D., G.B.C., G.K.C., D.F., and J.S. performed experiments; S.M.D., G.B.C., G.K.C., D.F., and O.J. analyzed data; S.M.D., G.B.C., G.K.C., D.F., and O.J. interpreted results of experiments; S.M.D., J.S., and O.J. drafted manuscript; S.M.D., G.B.C., G.K.C., D.F., J.S., and O.J. approved final version of manuscript; G.B.C., G.K.C., D.F., and O.J. edited and revised manuscript; O.J. prepared figures.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the participants who volunteered for this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adams JD, Ganio MS, Burchfield JM, Matthews AC, Werner RN, Chokbengboun AJ, Dougherty EK, LaChance AA. Effects of obesity on body temperature in otherwise-healthy females when controlling hydration and heat production during exercise in the heat. Eur J Appl Physiol 115: 167–176, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American College of Sports Medicine, Sawka MN, Burke LM, Eichner ER, Maughan RJ, Montain SJ, Stachenfeld NS. American College of Sports Medicine position stand: Exercise and fluid replacement. Med Sci Sports Exerc 39: 377–390, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bainbridge FA. The Physiology of Muscular Exercise. London: Longmans, Green, 1919. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bar-Or O, Lundegren HM, Buskirk ER. Heat tolerance of exercising obese and lean women. J Appl Physiol 26: 403–409, 1969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bergeron MF, McKeag DB, Casa DJ, Clarkson PM, Dick RW, Eichner ER, Horswill CA, Luke AC, Mueller F, Munce TA, Roberts WO, Rowland TW. Youth football: heat stress and injury risk. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37: 1421–1430, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Candas V, Libert JP, Vogt JJ. Human skin wettedness and evaporative efficiency of sweating. J Appl Physiol 46: 522–528, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheuvront SN. Match maker: how to compare thermoregulatory responses in groups of different body mass and surface area. J Appl Physiol 116: 1121–1122, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cramer MN, Jay O. Selecting the correct exercise intensity for unbiased comparisons of thermoregulatory responses between groups of different mass and surface area. J Appl Physiol 116: 1123–1132, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.CSEP. Canadian Society for Exercise Physiology: Certified Fitness Appraiser Resource Manual. Ottawa, Ontario, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Davis SL, Wilson TE, White AT, Frohman EM. Thermoregulation in multiple sclerosis. J Appl Physiol 109: 1531–1537, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Deren TM, Coris EE, Bain AR, Walz SM, Jay O. Sweating is greater in NCAA football linemen independently of heat production. Med Sci Sports Exerc 44: 244–252, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11a.DuBois D, Dubois E. A formula to estimate surface area if height and weight are known. Arch Intern Med 17: 863, 1916. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eijsvogels TM, Veltmeijer MT, Schreuder TH, Poelkens F, Thijssen DH, Hopman MT. The impact of obesity on physiological responses during prolonged exercise. Int J Obes (Lond) 35: 1404–1412, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Falk B, Dotan R. Children's thermoregulation during exercise in the heat: a revisit. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 33: 420–427, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, Buchner A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 39: 175–191, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gagnon D, Jay O, Kenny GP. The evaporative requirement for heat balance determines whole-body sweat rate during exercise under conditions permitting full evaporation. J Physiol 591: 2925–2935, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ganio MS, Adams JD. Response. Eur J Appl Physiol 115: 1603–1604, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Geddes LA, Baker LE. The specific resistance of biological material—a compendium of data for the biomedical engineer and physiologist. Med Biol Eng 5: 271–293, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Havenith G. Individual Heat Stress Response (PhD Thesis). Katholieke Universiteit Nijmegen, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Havenith G, Coenen JM, Kistemaker L, Kenney WL. Relevance of individual characteristics for human heat stress response is dependent on exercise intensity and climate type. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 77: 231–241, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Havenith G, van Middendorp H. The relative influence of physical fitness, acclimatization state, anthropometric measures and gender on individual reactions to heat stress. Eur J Appl Physiol Occup Physiol 61: 419–427, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haymes EM, McCormick RJ, Buskirk ER. Heat tolerance of exercising lean and obese prepubertal boys. J Appl Physiol 39: 457–461, 1975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang M, Jay O, Davis SL. Autonomic dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: implications for exercise. Auton Neurosci 188: 82–85, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jay O. Unravelling the true influences of fitness and sex on sweating during exercise. Exp Physiol 99: 1265–1266, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jay O, Bain AR, Deren TM, Sacheli M, Cramer MN. Large differences in peak oxygen uptake do not independently alter changes in core temperature and sweating during exercise. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 301: R832–R841, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jay O, Cramer MN. A new approach for comparing thermoregulatory responses of subjects with different body sizes. Temperature 2: 42–43, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kerslake DM. The stress of hot environments. Monogr Physiol Soc 1–312, 1972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Koppe C, Kovats S, Jendritzky G, Menne B. Heat Waves: Risks and Responses. WHO, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leites GT, Sehl PL, Cunha Gdos S, Detoni Filho A, Meyer F. Responses of obese and lean girls exercising under heat and thermoneutral conditions. J Pediatr 162: 1054–1060, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Limbaugh JD, Wimer GS, Long LH, Baird WH. Body fatness, body core temperature, and heat loss during moderate-intensity exercise. Aviat Space Environ Med 84: 1153–1158, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McArdle WD, Katch FI, Katch VL. Exercise Physiology: Nutrition, Energy, and Human Performance. Philadelphia, PA: Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams and Wilkins, 2015, p. lix, 1028 p. [Google Scholar]

- 31.McEntire SJ, Chinkes DL, Herndon DN, Suman OE. Temperature responses in severely burned children during exercise in a hot environment. J Burn Care Res 31: 624–630, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell D. Convective heat loss from man and other animals. In: Heat Loss from Animals and Man, edited by Monteith JL, Mount LE. London: Butterworths, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishi Y. Measurement of thermal balance in man In: Bioengineering, Thermal Physiology and Comfort, edited by Cena K, Clark J. New York: Elsevier, 1981, p. 29–39. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oppliger RA, Magnes SA, Popowski LA, Gisolfi CV. Accuracy of urine specific gravity and osmolality as indicators of hydration status. Int J Sport Nutr Exerc Metab 15: 236–251, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parsons KC. Human Thermal Environments. London: Taylor and Francis, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rowland T. Thermoregulation during exercise in the heat in children: old concepts revisited. J Appl Physiol 105: 718–724, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Selkirk GA, McLellan TM. Influence of aerobic fitness and body fatness on tolerance to uncompensable heat stress. J Appl Physiol 91: 2055–2063, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smoljanic J, Morris NB, Dervis S, Jay O. Running economy, not aerobic fitness, independently alters thermoregulatory responses during treadmill running. J Appl Physiol 117: 1451–1459, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Stachenfeld NS, Yeckel CW, Taylor HS. Greater exercise sweating in obese women with polycystic ovary syndrome compared with obese controls. Med Sci Sports Exerc 42: 1660–1668, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wenger CB. Heat of evaporation of sweat: thermodynamic considerations. J Appl Physiol 32: 456–459, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]