Abstract

Inflammatory diseases of the respiratory system such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease are increasing globally and remain poorly understood conditions. Although attention has long focused on the activation of type 1 and type 2 helper T cells of the adaptive immune system in these diseases, it is becoming increasingly apparent that there is also a need to understand the contributions and interactions between innate immune cells and the epithelial lining of the respiratory system. Cigarette smoke predisposes the respiratory tissue to a higher incidence of inflammatory disease, and here we have used zebrafish gills as a model to study the effect of cigarette smoke on the respiratory epithelium. Zebrafish gills fulfill the same gas-exchange function as the mammalian airways and have a similar structure. Exposure to cigarette smoke extracts resulted in an increase in transcripts of the proinflammatory cytokines TNF-α, IL-1β, and MMP9 in the gill tissue, which was at least in part mediated via NF-κB activation. Longer term exposure of fish for 6 wk to cigarette smoke extract resulted in marked structural changes to the gills with lamellar fusion and mucus cell formation, while signs of inflammation or fibrosis were absent. This shows, for the first time, that zebrafish gills are a relevant model for studying the effect of inflammatory stimuli on a respiratory epithelium, since they mimic the immunopathology involved in respiratory inflammatory diseases of humans.

Keywords: zebrafish gills, inflammation, cigarette smoke

mucosal inflammatory diseases of the airways such as severe asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or of the lung parenchyma and alveolar epithelium such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis are increasing globally and remain areas of considerable unmet medical need. Although these pulmonary inflammatory diseases have long been attributed to dysregulation of type 1 and type 2 helper T cell (Th1 and Th2) responses, it is becoming increasingly apparent that interactions between innate immune cells and the epithelium of the lung play key roles in the initiation of these conditions (28). Currently, there are no treatments available that go beyond symptomatic relief and that could stop the progressive course of COPD or fibrosis. Thus there is a need for a better understanding of the initiation and the mechanisms within different cellular components of mucosal tissues that drive mucosal inflammation and for the development of new in vivo models to enable generation of new treatments that could help to prevent mucosal inflammatory conditions. Cigarette smoking is one of the main risk factors associated with inflammatory diseases of the lung including asthma (22), COPD (2), and idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (4). Cigarette smoke (CS) exposure leads to induction of proinflammatory genes that drive cellular infiltration and pathology; however, the exact cellular mediators and mechanisms underlying the pathogenesis of CS-induced lung inflammatory diseases remain unclear. There is some evidence for a role for the transcription factor nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) pathway in the pathogenesis of COPD and asthma (8, 11), since NF-κB activation regulates the production of proinflammatory mediators associated with these diseases (3). NF-κB activation within epithelial cells has been implicated in the responses to mucosal infections (34) and house dust mite exposure (45), yet the role of NF-κB activation within epithelial cells in the orchestration of inflammatory signals during CS-induced inflammation remains controversial (37).

The zebrafish (Danio rerio) is a model that offers unique experimental opportunities to study mechanisms of inflammation in vivo. Zebrafish possess both innate (developing between 0–5 days postfertilization; dpf) and adaptive (developing 3–6 wk postfertilization) immune responses and, like other vertebrates, possess a variety of immune cells including macrophages, granulocytic cells, T cells with markers for Th1 and Th2, and B cells (40). The main signaling pathways of the innate immune system such as NF-κB, Toll-like receptors (TLRs), and Nod-like receptors (NLRs) are conserved in zebrafish (27, 43, 46) and the behavior and activity of macrophages and neutrophils, cell types of particular importance in pulmonary inflammatory disease, are strikingly similar in human and zebrafish (32, 38). To study the involvement of these signaling pathways and different cell types in mucosal inflammation in vivo, many fluorophore-expressing transgenic zebrafish lines are available (13, 20, 21, 25, 39). The gills of zebrafish fulfill the same gas-exchange function and have a similar structure to the mammalian airways, with a mucus-covered respiratory epithelium scattered with immune cells and smooth muscle cells at the base of the lamella. From 14 dpf zebrafish fully depend on their gills to fulfill their oxygen requirements (42), considerably earlier than mice (23). A major experimental advantage is that the gill tissue is directly exposed to ambient water, which facilitates direct targeting with any waterborne substance without using invasive procedures. These features suggest that the gills of zebrafish are a potentially useful model to study acute pulmonary inflammation and the pathways involved.

Here we have used zebrafish as a model to study the effect of inflammatory stimuli such as CS on the gill tissue and recapitulated some of the basic features of the pathophysiological responses observed in human. We find that an acute exposure to CS extracts induces transcriptional upregulation of NF-κB-dependent proinflammatory gene expression in the gills of zebrafish and that a longer term exposure leads to structural changes of the gill tissue. This shows that zebrafish gills reproduce important aspects of the immunopathology previously characterized in respiratory inflammatory diseases of humans. Therefore, they provide an alternative model for understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying immunity within a respiratory epithelium induced by inflammatory stimuli delivered in a noninvasive fashion.

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Zebrafish care.

Wild-type and transgenic zebrafish strains used in this study were maintained according to standard practices, and all procedures conformed to UK Home Office requirements (ASPA 1986 under the project licence PPL 70/7472). Fish were reared and maintained at 28.5°C on a 14-h light:10-h dark cycle. The transgenic zebrafish lines Tg(mpx:GFP) [Tg(mpx:GFP)i114] (39) and Tg(NFkB:EGFP) [Tg(pNF-kB:EGFP)sh235] (25) were used.

Exposure to CS extracts.

Water containing CS extract was freshly prepared for each experiment by bubbling smoke from one standard reference research cigarette (3R4F; cigarette filter removed, Kentucky Tobacco Research & Development Center) through 5 ml system water using an electrical pump (at a rate of 1 cigarette/2 min; 2 s on, 10 s off) to standardize the pressure applied as previously described (10). The solution was filtered through a 0.2-μm filter (Nalgene). The resulting concentration of CS was 0.2 cigarettes/ml (c/ml). CS was then further diluted in system water to obtain concentrations described elsewhere. Adult zebrafish were randomly assigned to the various treatment groups.

Whole-mount staining of zebrafish gill tissue.

Zebrafish adults were euthanized with a lethal dose of MS222 (4 mg/ml; Sigma), and gills were dissected and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight at 4°C. Following fixation gills were washed twice in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and deionized water (dH2O), transferred to acetone for 7 min at −20°C, rinsed in dH2O, and then incubated in blocking solution (5% donkey serum and/or 5% goat serum, 1% DMSO, and 0.1% Tween in PBS) for 30 min. All the following steps were performed in blocking solution: gill tissues were incubated with a polyclonal chicken anti-zebrafish l-plastin antibody (1:500, kind gift from Paul Martin, University of Bristol, UK) or a polyclonal rabbit anti-GFP antibody (1:1,000, Life Technologies, A-11122) at 4°C overnight, washed four times for 20 min, incubated with a goat anti-chicken-AF555 antibody (1:500, Life Technologies, A-2137) or a donkey anti-rabbit-AF488 antibody (1:500, Life Technologies, A-21206) for 4 h at room temperature, washed four times for 20 min, rinsed briefly with PBS-Tween (0.1%; PBS-T), and imaged. Gill tissues were then imaged via a confocal microscope, and cell numbers were counted in a blinded manner.

Histology.

Whole zebrafish heads were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin overnight at room temperature. Samples were then washed in PBS and decalcified in ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (EDTA) solution containing 8% EDTA and 0.8% sodium hydroxide for 7–10 days. After decalcification, specimens were washed with tap water, dehydrated, and paraffin wax embedded. Sections (4 μm) were cut on a Leica rotary microtome RM2235 and mounted on slides. Slides were dried, deparaffinized in xylol, rehydrated, and stained with either hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), Alcian blue/periodic acid-Schiff (PAS), trichrome, or picrosirius red (PSR). Staining and coverslipping was performed on a Leica ST5020-CV5030 workstation. Lamellar fusion of gill tissue was quantified by a qualitative score ranging from 0 to 3 whereby severe lamellar fusion affecting all lamella was scored with 3 and the absence of lamellar fusion was scored with 0.

Flow cytometry.

For analysis of neutrophils, gill tissues from adult Tg(mpx:GFP) were dissected, dissociated into single-cell suspensions by digestion for 15 min at 37°C with PBS containing 0.25% trypsin, 1 mM EDTA, and 5 mg/ml collagenase P (Roche), and subjected to flow cytometry in presence of 1 μg/ml DAPI (Sigma) for live/dead cell discrimination. Samples were processed on a LSRFortessa (BD Biosciences) and analyzed by use of FlowJo software (Tree Star).

qRT-PCR.

Dissected gill tissues from adult zebrafish were homogenized by using a pestle in lysis buffer and processed for RNA by using the MagMAX-96 Total RNA Isolation Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions. The quantity and quality of RNA were assessed spectrophotometrically by using a Thermo Scientific NanoDrop 1000, and 125 ng of total RNA were used for reverse transcription by using a High-Capacity cDNA Archive Kit (Applied Biosystems) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed with 2% of complementary DNA generated by using Taq Fast Universal 2× PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and TaqMan primer and probes assays for 18S, zebrafish il1b (Dr03114368_m1), tnfa (Dr03126850_m1), tnfb (Dr03122586_m1), mmp9 (Dr03139882_m1), il10 (Dr03103209_m1), il15 (Dr03077605_m1), ifnphi1 (Dr03100938_m1), mpeg1 (Dr03439207_g1), lyz (Dr03099436_m1), mpx (Dr03075659_m1), lcp1 (Dr03099284_m1), col1a1a (Dr03150834_m1), ctgf (Dr03135190_g1), acta2 (Dr03088509_mH), and SYBR Green Fast Universal 2× PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) with the following primers: cxcl8-l1 (forward TGTGTTATTGTTTTCCTGGCATTTC, reverse CTGTAGATCCACGCTGTCGC), cxcl8-l2 (forward GCTGGATCACACTGCAGAAA, reverse TGATGAAAGGACAATTCAGTGG), lck (forward ACGCCGAAGAAGATCTC, reverse GCTTGGGGCAGTTACA) and il6 (forward TCAACTTCTCCAGCGTGATG, reverse TCTTTCCCTCTTTTCCTCCTG).

All reactions were performed in duplicate using a 7500 Fast Real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). Cycle threshold (Ct) values obtained were normalized to 18S and calibrated to the median control fish gill sample for relative quantification by the comparative Ct method.

Statistical analysis.

All statistical analysis was carried out with GraphPad Prism 4.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Normality distribution was tested with the D'Agostino-Pearson omnibus test. When comparing two groups, unpaired two-tailed t-tests (followed by Welch's correction test for nonequal standard deviations) and Mann-Whitney tests were used for parametric and nonparametric datasets, respectively. When comparing more than two groups, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's or Bonferroni's multiple-comparison test and Kruskal-Wallis test followed by a Dunn's multiple-comparison test were used for parametric and nonparametric datasets, respectively. P values of less than 0.05 were deemed statistically significant with ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, and *P < 0.05. Error bars represent standard error of the mean (SE).

RESULTS

CS exposure induces increased transcript levels of proinflammatory cytokines in the gills.

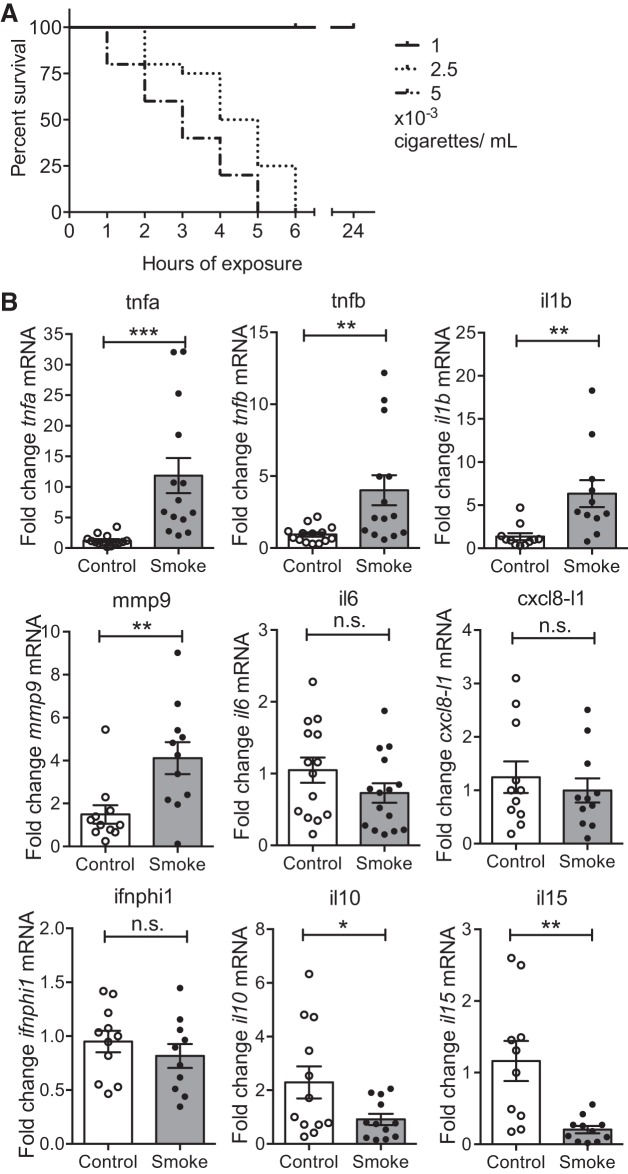

To investigate the effects of CS on the gills, adult zebrafish were exposed to CS water extracts prepared in the same manner as that used in tissue culture experiments (10). First a survival titration was established, and we found that fish tolerated a concentration of 1 × 10−3 cigarettes/ml (c/ml) in system water over 24 h whereas higher concentrations were toxic, leading rapidly to death (Fig. 1A). Consequently, all following experiments were performed at a concentration of 1 × 10−3 c/ml of smoke extracts.

Fig. 1.

Cigarette smoke (CS) exposure induces proinflammatory cytokines in zebrafish gills. A: zebrafish juveniles and adults were exposed to CS and their survival (%) was monitored over 6 or 24 h. Median ± SE is shown for each concentration, 3 experimental replicates, total number of fish n ≥ 17. B: quantitative RT-PCR (qRT-PCR) analysis of indicated transcript levels in gill tissue samples after 6 h of smoke exposure. Dot plots show relative expression values obtained for individual fish (n ≥ 10), which were normalized to 18S and expressed as fold change relative to the median control sample. Three experimental replicates were performed and data were pooled (each experiment following the same trend). Mean ± SE for each group is shown. Mann-Whitney test. n.s., Nonsignificant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

qRT-PCR analysis was used to assess the effect on the transcript levels of proinflammatory cytokines previously reported to be affected in mammals following CS exposure (9). Continuous exposure of adult zebrafish to CS extracts for 6 h resulted in a significant increase in tnfa, tnfb, il1b, and mmp9 transcripts in the gill tissue (Fig. 1B). A time-course experiment revealed that the increase in transcript levels of tnfa and il1b transcripts following smoke exposure was transient, i.e., the transcript levels peaked at 9 h of exposure followed by a return to baseline expression levels present in control fish gills by as early as 24 h (data not shown).

Further qRT-PCR analysis after 6 h of exposure showed no change in il6, cxcl8-l1 transcripts (cxcl8-l2 transcripts were not detectable) or ifnphi1 transcripts, while a decrease in il10 and il15 transcripts was detected (Fig. 1B).

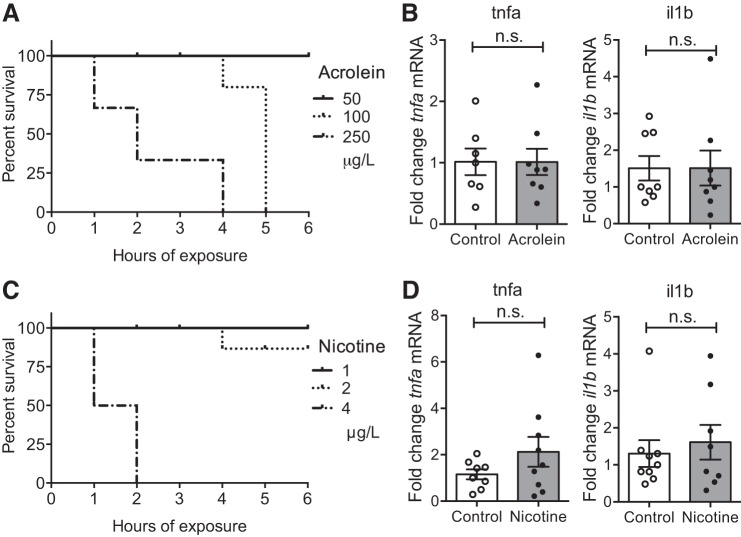

Smoke extracts consist of about 4,000 different compounds, which are generally inhaled together by smokers. Among those are acrolein, a toxicant that induces oxidative stress, and nicotine, also a component of most e-cigarettes. To test whether the increase in proinflammatory cytokines was specific to the complex mixture of compounds or could be recapitulated by individual components, zebrafish adults were exposed to sublethal concentrations of acrolein and nicotine (Fig. 2, A and B) and their gill tissues were analyzed by qRT-PCR. Zebrafish survived a maximum concentration of 50 μg/l (=0.9 μM) of acrolein over a 6-h exposure, which is about 100-fold lower than the concentration of acrolein (∼80 μM) that has been estimated to reach the human lung (12), indicating that zebrafish are highly sensitive to this compound. Exposure to 50 μg/l acrolein did not induce changes in the transcript levels of tnfa or il1b (Fig. 2C). The sublethal concentration of nicotine for an exposure of 6 h was found to be 2 mg/l (=12 μM), which did not induce changes in the transcript levels of tnfa or il1b (Fig. 2D). Two additional concentrations of nicotine were tested based on those used in rats to reflect the concentration of nicotine found in the blood of moderate smokers (17). No difference was found in the transcript levels of tnfa or il1b following 6 h of exposure to nicotine at 0.2 μg/l (n = 4) and 20 μg/l (n = 4) compared with control levels (data not shown).

Fig. 2.

Characterization of inflammatory response in the gills of zebrafish upon exposure to acrolein and nicotine. A and C: zebrafish adults were exposed to acrolein (A) or nicotine (C) and their survival (%) was monitored over 6 h. Median ± SE is shown for each concentration. Total number of fish n ≥ 7. B and D: dissected gill tissues from fish exposed to 50 μg/l acrolein (B) or 2 mg/l nicotine (D) were subjected to qRT-PCR analysis for analysis of indicated transcript levels. Dot plots show relative expression values obtained for individual fish (n ≥ 7), which were normalized to 18S and expressed as fold change relative to the median control sample for each gene analyzed. Means ± SE are shown for 2 independent experiments. n.s., Nonsignificant.

Together, these data suggest that exposure to the complex mixture of CS extract induces an acute increase in proinflammatory cytokines in zebrafish gills that is not recapitulated by exposure to the individual components acrolein or nicotine.

Decreased number of neutrophils in gill tissue following exposure to CS.

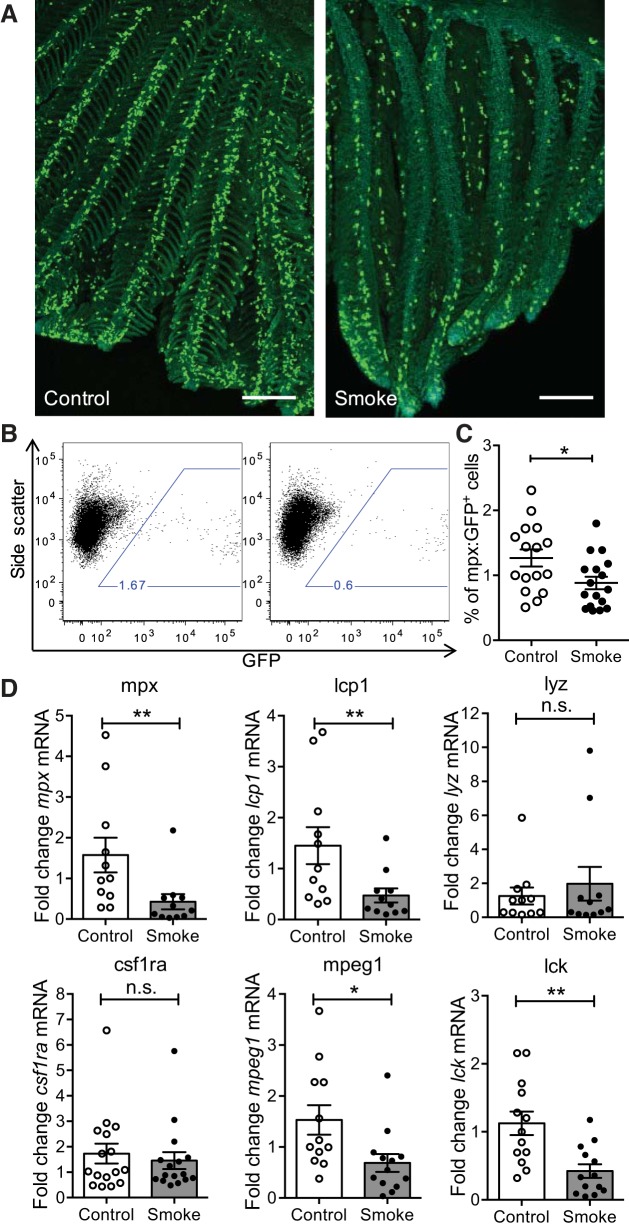

The effect of CS on neutrophils was investigated in the transgenic zebrafish line Tg(mpx:GFP) in which GFP expression is driven by the myeloperoxidase (mpx) promoter (39).

As detected by confocal microscopy of whole gill tissue samples, the majority of GFP+ neutrophils were located along the filaments at the bottom of each lamella, whereas only very few neutrophils were detected within the lamellar epithelium at steady state (Fig. 3A). Exposure to CS resulted in a reduction in the number of neutrophils in the gills mainly along the filament (Fig. 3A). Flow cytometry of single cell suspensions prepared from gill tissue samples confirmed the decrease in percentage of neutrophils present in the gill after exposure to CS (Fig. 3, B and C).

Fig. 3.

Reduction in the number of neutrophils in zebrafish gills following CS exposure. All fish were exposed to CS for 6 h. A: representative images of whole gill tissues from adult transgenic zebrafish Tg(mpx:GFP) labeled with an anti-green fluorescent protein (GFP) antibody (green) and DRAQ5 (cyan). Scale bars: 100 μm. B: representative flow cytometry dot plots of dissected and enzymatically digested gill tissue of adult Tg(mpx:GFP) transgenic zebrafish. C: quantification of % of GFP+ cells of Tg(mpx:GFP) zebrafish gills obtained by flow cytometry. Each single dot represents the % of GFP+ cells obtained for 1 individual (n = 16). Three experimental replicates were performed and data were pooled (each experiment following the same trend). Means ± SE are shown. Two-tailed t-test. D: qRT-PCR analysis of indicated transcript levels in gill tissue samples. Dot plots show relative expression values obtained for individual fish (n ≥ 10), which were normalized to 18S and expressed as fold change relative to the median control sample. Three experimental replicates were performed and data were pooled (each experiment following the same trend). Means ± SE. Mann-Whitney test. n.s., Nonsignificant, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

To further confirm this finding, qRT-PCR analysis of transcripts of immune cell markers was performed on whole gill tissues harvested from adult zebrafish exposed to CS or not. Figure 3D shows that mpx (neutrophils) and lcp1 (leukocytes) transcripts were also decreased in the gills following CS exposure. Time-course analysis revealed that, in contrast to tnfa and il1b, the decrease in transcript levels of mpx and lcp1 was not transient but remained low compared with those of control samples over a 24-h period (data not shown). Analysis of lyz transcripts, marking neutrophils in zebrafish embryos (21) and potentially a more macrophage-like cell type in zebrafish adults (41), revealed no differences between control and smoke-exposed zebrafish gills (Fig. 2D). There was also no change in transcript levels of macrophage marker gene csf1ra (20) following exposure to smoke, but a decrease in transcripts of mpeg1, another macrophage marker gene in zebrafish (13). A decrease in lck transcripts (T cells) was also observed (Fig. 3D). All together these results indicate that exposure to CS did not induce accumulation of immune cells but rather that less immune cells were present in the gill tissue after CS exposure.

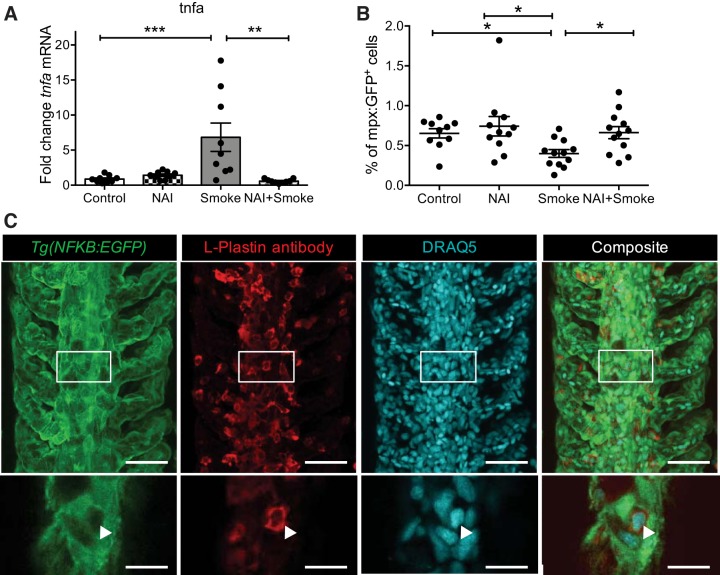

NF-κB pathway activation within the gill tissue contributes to acute inflammatory response in zebrafish gills induced by CS exposure.

NF-κB-mediated TNF-α release has been implicated in CS-induced pathologies of the lung (11). To interrogate the role NF-κB in CS-induced responses in gills, adult zebrafish were pretreated with the inhibitor of NF-κB activation (NAI) (44) for 24 h before being exposed to CS for 6 h. qRT-PCR analysis revealed that treatment with NAI abrogated the increase in tnfa transcript levels consequent to CS exposure (Fig. 4A). Flow cytometry analysis performed on Tg(mpx:GFP) zebrafish gills showed that NAI treatment also blocked the reduction in GFP+ neutrophils following CS exposure (Fig. 4B). Together these results suggest inflammatory responses in zebrafish gills are mediated by NF-κB activation.

Fig. 4.

NF-κB pathway activation in zebrafish gill tissue contributes to CS-induced inflammation. A and B: zebrafish were pretreated with 25 nM NF-κB activation (NAI) for 24 h before exposure to CS for 6 h. A: qRT-PCR analysis of tnfa transcript levels in gill tissue samples. Dot plots show relative expression values obtained for individual fish (n = 9), which were normalized to 18S and expressed as fold change relative to the median control sample. B: quantification of % of GFP+ cells of Tg(mpx:GFP) zebrafish gills obtained by flow cytometry. Each single dot represents the % of GFP+ cells obtained for 1 individual (n ≥ 10). Three experimental replicates were performed and data were pooled. Means ± SE. Mann-Whitney test. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. C: representative images (maximum projection of confocal z-stack) of whole gill tissues at steady state from adult transgenic zebrafish Tg(NFkB:EGFP) labeled with an anti-GFP antibody (green), an anti-L-plastin antibody (red), and DRAQ5 (cyan). Insets depict single slice of confocal z-stack. Triangles indicate a single L-plastin+ cell. Scale bars: 25 μm (top), 5 μm (insets).

To try and localize NF-κB activation in the adult zebrafish gills, the Tg(NFkB:EGFP) fish line in which cells express EGFP following NF-κB pathway activation (25) was used, which bears a transgene containing a synthetic enhancer element consisting of six repeats of a NF-κB binding site from the human κ light chain immunoglobulin gene, thereby allowing NF-κB-dependent gene transcription to be investigated. As shown in Fig. 4C, there was a high number of EGFP+ cells lining the gills at steady state, which we interpret to be gill epithelial cells. Because of the absence of a gill-epithelial cell marker, we performed costaining with an L-plastin antibody, a pan-leukocyte marker (33), to determine whether immune cells exhibit NF-κB activation. The distribution of L-plastin+ leukocytes within the gill tissue is similar to that of neutrophils (Fig. 3A) where only a few cells are located within the lamella and most cells are found along the filament at the bottom of each lamella (Fig. 4A). Higher resolution imaging and manual quantification showed that only a small percentage of L-plastin+ immune cells (5.7 ± 1.3 of cells per lamellae and corresponding area of the filament) showed EGFP expression, suggesting that mainly gill epithelial cells displayed NF-κB activation at steady state.

Next, we tested whether CS exposure would increase EGFP fluorescence intensity in the gill tissue as a readout for CS-induced NF-κB activation. Tg(NFkB:EGFP) zebrafish were exposed to CS and gills were harvested for quantification of EGFP fluorescence intensity by flow cytometry (following 6 or 8 h of exposure) and EGFP mRNA levels by qRT-PCR (following 6 h of exposure). We did not detect any further significant increase in either EGFP fluorescence or mRNA levels in the gills following exposure to CS, suggesting that high EGFP levels reflecting high steady-state levels of NF-κB activation prevented such detection. Interestingly, the percentage of L-plastin+ leukocytes displaying EGFP fluorescence was unchanged following exposure to CS (5.5 ± 1 of cells per lamellae and corresponding area of the filament), suggesting that NF-κB activation following CS does not occur in leukocytes in this model.

Long-term exposure to CS induces extensive, but reversible, structural changes and no collagen deposition.

Since acute exposure of zebrafish gills to CS resulted in similar inflammatory responses to those seen in mammalian lungs, it was reasoned that long-term exposure to CS, associated with tissue remodeling in humans, could give similar fibrotic responses in zebrafish gills. To examine this, adult zebrafish were repeatedly exposed to CS for 6 h/day, 3 days/wk, for 6 wk. After 6 wk, half the group of exposed fish was harvested for analysis while the other half was left to recover, i.e., in system water only, for 4 wk.

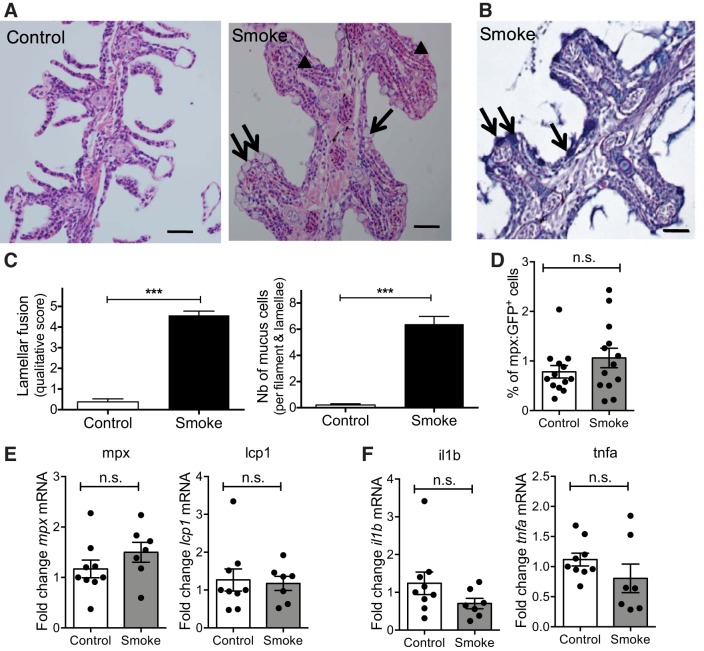

Histological analysis revealed dramatic morphological changes in gills after exposure to CS for 6 wk. CS-exposed gills displayed lamellar fusion and epithelial cell hyperplasia together with an increase in the number of mucus cells as confirmed by Alcian blue/PAS staining (Fig. 5, A–C). Analysis of adult Tg(mpx:GFP) zebrafish gills after 6 wk of exposure to CS showed no changes in the percentage of GFP+ neutrophils compared with control exposed animals (Fig. 5D). This observation was confirmed by qRT-PCR analysis of mpx and lcp1 transcript levels, which were also unchanged following long-term exposure to CS (Fig. 5E). Furthermore, qRT-PCR analysis of proinflammatory cytokines showed that there was no significant change in tnfa and il1b transcript levels following 6 wk of exposure to CS (Fig. 5F). Together, these data suggest that long-term exposure to CS, at least in the conditions assessed in this study, does not induce chronic inflammation as defined by accumulation of immune cells and proinflammatory cytokines.

Fig. 5.

Structural changes to the gills following longer term exposure to CS. Fish were exposed to 0.75 × 10−3 c/ml CS extracts for 6 h/day, 3 days/wk, for 6 wk. A and B: representative images of coronal sections of zebrafish heads stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) (A) and Alcian blue/periodic acid (PAS) (B) showing the gills. Triangles indicate lamellar fusion (A) and arrows indicate mucus cells (A and B) observed in smoke-exposed fish. Three independent experiments. Scale bars: 50 μm. C: quantification of the number (Nb) of mucus cells (right) and the degree of lamellar fusion (left) of the gill tissue within the area of a filament. Bar charts are means ± SE of n ≥ 18. Data are pooled from 3 independent experiments. Kruskal-Wallis test. D: quantification of % of GFP+ cells in Tg(mpx:GFP) zebrafish gills obtained by flow cytometry. Each single dot represents the % of GFP+ cells obtained for 1 individual (n ≥ 12). Three experimental replicates were performed and data were pooled. E and F: qRT-PCR analysis of indicated transcript levels. Data are relative expression values obtained for individual fish (n ≥ 7), which were normalized to 18S and expressed as fold change relative to the median control sample. Means ± SE. Two independent experiments. n.s., Nonsignificant, ***P < 0.001.

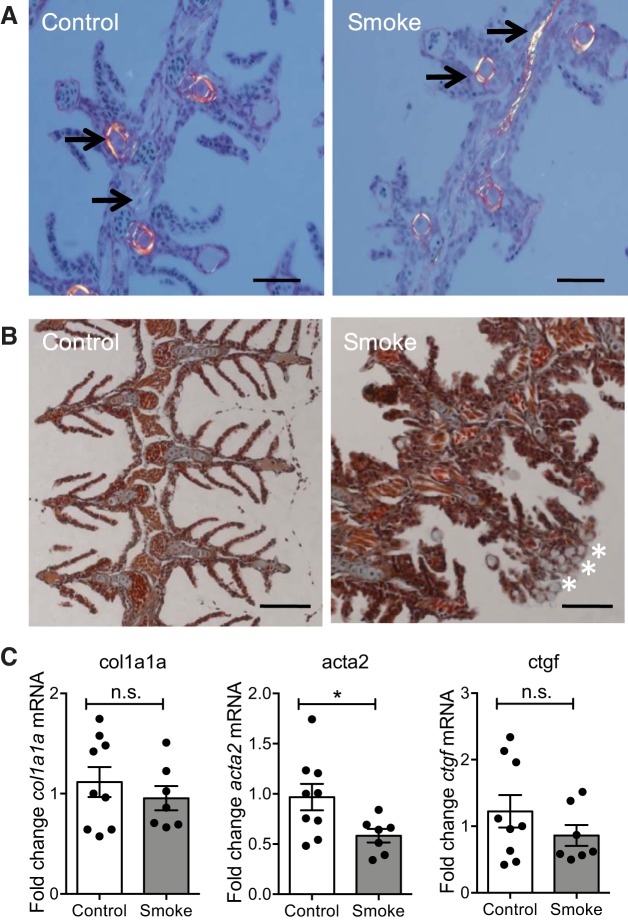

The hallmark of scarring and fibrosis is the deposition of extracellular matrix proteins, with collagen type 1 being the main collagen type found in mammals and zebrafish (18, 41, 48). Histological analysis was performed to identify the presence of collagen protein by the collagen-specific PSR stain under polarized light. As shown in Fig. 6A, collagenous structures within the gill tissue were readily detectable; however, no differences between fish exposed to CS compared with control were observed. In addition to PSR, trichrome staining was performed, but no differences between CS-exposed fish could be observed (Fig. 6B). qRT-PCR analysis on zebrafish gill tissue exposed to CS for 6 wk confirmed these findings, since no changes in transcript levels of genes associated with fibrosis, such as col1a1a, acta2 (α-smooth muscle actin), and ctgf (connective tissue growth factor), were detected (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Longer term exposure to CS does not induce fibrosis in zebrafish gills. Fish were exposed to 0.75 × 10−3 c/ml smoke extracts for 6 h/day, 3 days/wk, for 6 wk. A and B: representative images of coronal sections of zebrafish heads stained with picrosirius red (A) and trichrome (B). Arrows indicate collagenous structures, and asterisks indicate mucus cells. Three independent experiments. Scale bars: 50 μm. B: qRT-PCR analysis of indicated transcript levels. Data are relative expression values obtained for individual fish (n ≥ 7), which were normalized to 18S and expressed as fold change relative to the median control sample. Means ± SE. Two independent experiments. n.s., Nonsignificant.

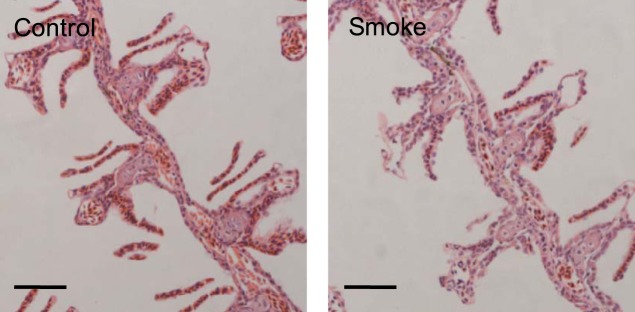

Analysis of fish that were left to recover in system water for 4 wk following exposure to CS showed completely restored gill architecture with no epithelial damage nor lamellar fusion remaining (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Histological analysis of gill tissue after recovery following long-term exposure to CS. Representative images of coronal sections of zebrafish heads stained with H&E showing the gills. Fish were exposed to 0.75 × 10−3 c/ml smoke extracts for 6 h/day, 3 days/wk, for 6 wk and subsequently left to recover in system water for 4 wk. Representative images of 3 experiments are shown. Scale bars: 50 μm.

Together, these results indicate that, despite structural changes of the gill tissue following long-term exposure to CS, zebrafish have mechanisms in place to avoid collagen deposition and fibrosis.

DISCUSSION

To date, there is only a limited understanding of the initiation of inflammatory conditions of the lung, making asthma, COPD, and pulmonary fibrosis still impossible to cure. Although rodent models have undoubtedly provided much of the conceptual framework regarding the involvement of adaptive immune responses as critical drivers of these conditions, modulation of these responses is not sufficient to effectively treat mucosal inflammatory disease in humans. Thus a better understanding of the exact disease etiology especially with regards to the contribution of innate immune responses and the epithelium is needed (28). Here, we describe the zebrafish gill as a new powerful model to study the inflammatory effect of stimuli delivered noninvasively to a respiratory mucosal epithelium, offering a replacement to rodent models that rely on invasive techniques such as intratracheal administration of stimuli and bronchoalveolar lavage. CS as a compound implicated in the risk of human pulmonary inflammatory conditions was investigated for its ability to trigger inflammation, tissue remodeling, and fibrosis.

We found that the zebrafish model shares key aspects of pulmonary inflammation of mouse and human, including the upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α and IL-1β. Our data further indicate that CS-induced increase in tnfa transcripts is dependent on NF-κB, suggesting that CS-induced inflammation might be similar to mouse lung dependence on TLR/IL1R signaling (9). To further confirm this notion, the zebrafish myd88 mutant (47) could be used to assess whether CS-mediated inflammation in zebrafish gills requires the adapter protein Myd88. CS exposure induces neutrophil accumulation in the bronchoalveolar space and pulmonary parenchyma of mice (9). In contrast, zebrafish gills show a decrease in the number and transcripts of tissue neutrophils. There is a possibility that CS is toxic and induces neutrophil apoptosis or death. This idea is supported by recent findings, suggesting that smoke exposure can induce the inflammatory form of cell death, termed pyroptosis, that is caspase 1 dependent (15). Furthermore, CS has been shown to induce the release of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in vitro (7), suggesting that the disappearance of neutrophils following CS exposure in zebrafish gills could be explained by NETosis, a unique form of cell death induced by NET release (5).

Our data suggest a role for NF-κB in the acute responses to CS as pretreatment with NAI-abrogated induction of tnfa transcripts and neutrophil disappearance. Since EGFP was highly and mainly expressed in the gill epithelium compared with immune cells, it is likely that NF-κB activation triggering these responses occurs in the epithelium. Nevertheless we could not detect an increase in EGFP fluorescence following exposure to CS. This is possibly due to the fact that activation is already maximal and the reporter is unable to display further enhancement of this pathway. The fact that CS exposure leads to an increase in proinflammatory cytokines but a decrease in the number of leukocytes further supports the notion that the epithelium might be the cellular origin of these inflammatory mediators. Indeed, the respiratory epithelium is capable of producing inflammatory cytokines, and the immune signaling machinery within the epithelium contributes to inflammatory responses in the respiratory tract (1). The recently published Tg(tnfa:GFP) line could provide further insights into the cellular origin of CS-induced responses (31).

Persistent exposure to tissue irritants is implicated in chronic inflammation and the pathogenesis of pulmonary lung fibrosis (49). Despite an acute inflammatory response following exposure to CS, we found that long-term exposure leads to structural changes of the gill tissue in the absence of chronic inflammation or collagen deposition, i.e., fibrosis. These data suggest that zebrafish gills have mechanisms in place to avoid detrimental chronic inflammatory processes following exposure to irritants. They also are consistent with previous studies in which scar-free healing in zebrafish was the outcome of inflammation and wound healing in different organs such as the brain, the heart, the skin, and the tail fin (16, 26, 35, 36, 41). We therefore believe that our established model can benefit the study of mammalian respiratory fibrosis by comparative analysis of mechanisms involved in inflammation of a respiratory epithelium that result in detrimental pulmonary fibrosis in mammals but not in zebrafish. As-yet-unknown mechanisms that drive resolution of inflammation or differences in the composition of cellular infiltration following exposure to CS might be responsible for preventing zebrafish gills from chronic inflammation and therefore potentially detrimental fibrosis. Studies in zebrafish in the field of heart and tail regeneration have uncovered the contribution of Fgf (29, 30, 35) and TGF-β/activin (6, 24) signaling pathways in the prevention of fibrosis following tissue injury, which might be also relevant for our gill injury model. Interestingly, despite the fact that both pathways have been shown to be essential for tissue regeneration following heart injury, inhibition of fgfr1 resulted in a persistent collagen-rich scar whereas interference with the TGF-β/activin signaling pathway resulted in the failure to deposit a collagenous matrix (6). Similar approaches could be used to characterize the involvement of these signaling pathways in processes that prevent the development of fibrosis in zebrafish gills.

Our model extends the possibilities for the use of zebrafish in studies of mucosal inflammation and immunity from the recently established models of a swim bladder infection (19) and CS condensate toxicity (14) in zebrafish larvae, which possess only an innate immune system, to adult zebrafish, which possess both an innate and adaptive immune system. This use of adults further allows the study of mucosal inflammatory responses upon exposure to respiratory stimuli in a gas-exchanging organ. It will also enable the effect of other respiratory irritants on a mucosal epithelial-immune cell interface in a live intact physiologically relevant system to be investigated. Zebrafish gills are readily exposed to the outside environment and therefore accessible for direct visualization of innate immune-epithelial cell interactions, which appear to recapitulate inflammatory events in mammalian respiratory inflammation.

Here, we demonstrate adult zebrafish gills as a versatile model to study the effect of respiratory stimuli on a mucosal epithelium in a noninvasive manner, which offers exciting future opportunities to observe innate immune-epithelial cell interactions in vivo.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the BBSRC and the NC3Rs. F. Progatzky was funded by a BBSRC CASE studentship supported by Boehringer Ingelheim.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

F.P., H.T.C., J.R.L., L.B., and M.J.D. conception and design of research; F.P. performed experiments; F.P. analyzed data; F.P., H.T.C., J.R.L., L.B., and M.J.D. interpreted results of experiments; F.P. prepared figures; F.P., L.B., and M.J.D. drafted manuscript; F.P., L.B., and M.J.D. edited and revised manuscript; F.P., H.T.C., J.R.L., L.B., and M.J.D. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Steve Renshaw for the Tg(NFkB:EGFP) and Paul Martin for the L-plastin antibody. We thank Lorraine Lawrence for help and expertise with histological techniques, Stephen Rothery and Debora Keller from the Imperial College FILM facility for expertise with confocal microscopy, Jane Srivastava and Catherine Simpson for expertise with flow cytometry, and the Imperial College Central Biological Services unit for care and support of our animal work. A special thanks to Hugh W. Ferguson for advice on gill histopathology and to Mark A. Birrell and Maria G. Belvisi for providing 3R4F research cigarettes and constructive discussions.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allen IC, Scull MA, Moore CB, Holl EK, McElvania-TeKippe E, Taxman DJ, Guthrie EH, Pickles RJ, Ting JPY. The NLRP3 inflammasome mediates in vivo innate immunity to influenza A virus through recognition of viral RNA. Immunity 30: 556–565, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barnes PJ. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Clin Chest Med 35: 71–86, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barnes PJ, Karin M. Nuclear factor-kappaB: a pivotal transcription factor in chronic inflammatory diseases. N Engl J Med 336: 1066–1071, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumgartner KB, Samet JM, Stidley CA, Colby TV, Waldron JA. Cigarette smoking: a risk factor for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 155: 242–248, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brinkmann V, Zychlinsky A. Neutrophil extracellular traps: is immunity the second function of chromatin? J Cell Biol 198: 773–783, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chablais F, Jazwinska A. The regenerative capacity of the zebrafish heart is dependent on TGFbeta signaling. Development 139: 1921–1930, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chrysanthopoulou A, Mitroulis I, Apostolidou E, Arelaki S, Mikroulis D, Konstantinidis T, Sivridis E, Koffa M, Giatromanolaki A, Boumpas DT, Ritis K, Kambas K. Neutrophil extracellular traps promote differentiation and function of fibroblasts. J Pathol 233: 294–307, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Di Stefano A, Caramori G, Oates T, Capelli A, Lusuardi M, Gnemmi I, Ioli F, Chung KF, Donner CF, Barnes PJ, Adcock IM. Increased expression of nuclear factor-kappaB in bronchial biopsies from smokers and patients with COPD. Eur Respir J 20: 556–563, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doz E, Noulin N, Boichot E, Guenon I, Fick L, Le Bert M, Lagente V, Ryffel B, Schnyder B, Quesniaux VFJ, Couillin I. Cigarette smoke-induced pulmonary inflammation is TLR4/MyD88 and IL-1R1/MyD88 signaling dependent. J Immunol 180: 1169–1178, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edirisinghe I, Yang SR, Yao H, Rajendrasozhan S, Caito S, Adenuga D, Wong C, Rahman A, Phipps RP, Jin ZG, Rahman I. VEGFR-2 inhibition augments cigarette smoke-induced oxidative stress and inflammatory responses leading to endothelial dysfunction. FASEB J 22: 2297–2310, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edwards MR, Bartlett NW, Clarke D, Birrell M, Belvisi M, Johnston SL. Targeting the NF-kappaB pathway in asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Pharmacol Ther 121: 1–13, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Eiserich JP, van der Vliet A, Handelman GJ, Halliwell B, Cross CE. Dietary antioxidants and cigarette smoke-induced biomolecular damage: a complex interaction. Am J Clin Nutr 62: 1490S–1500S, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellett F, Pase L, Hayman JW, Andrianopoulos A, Lieschke GJ. mpeg1 promoter transgenes direct macrophage-lineage expression in zebrafish. Blood 117: e49–e56, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ellis LD, Soo EC, Achenbach JC, Morash MG, Soanes KH. Use of the zebrafish larvae as a model to study cigarette smoke condensate toxicity. PLoS One 9: e115305, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Franklin BS, Bossaller L, De Nardo D, Ratter JM, Stutz A, Engels G, Brenker C, Nordhoff M, Mirandola SR, Al-Amoudi A, Mangan MS, Zimmer S, Monks BG, Fricke M, Schmidt RE, Espevik T, Jones B, Jarnicki AG, Hansbro PM, Busto P, Marshak-Rothstein A, Hornemann S, Aguzzi A, Kastenmuller W, Latz E. The adaptor ASC has extracellular and ‘prionoid’ activities that propagate inflammation. Nat Immunol 15: 727–737, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gemberling M, Bailey TJ, Hyde DR, Poss KD. The zebrafish as a model for complex tissue regeneration. Trends Genet 29: 611–620, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.George O, Grieder TE, Cole M, Koob GF. Exposure to chronic intermittent nicotine vapor induces nicotine dependence. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 96: 104–107, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gonzalez-Rosa JM, Peralta M, Mercader N. Pan-epicardial lineage tracing reveals that epicardium derived cells give rise to myofibroblasts and perivascular cells during zebrafish heart regeneration. Dev Biol 370: 173–186, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gratacap RL, Rawls JF, Wheeler RT. Mucosal candidiasis elicits NF-kappaB activation, proinflammatory gene expression and localized neutrophilia in zebrafish. Dis Model Mech 6: 1260–1270, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gray C, Loynes CA, Whyte MKB, Crossman DC, Renshaw SA, Chico TJA. Simultaneous intravital imaging of macrophage and neutrophil behaviour during inflammation using a novel transgenic zebrafish. Thromb Haemost 105: 811–819, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall C, Flores MV, Storm T, Crosier K, Crosier P. The zebrafish lysozyme C promoter drives myeloid-specific expression in transgenic fish. BMC Dev Biol 7: 42, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hansel TT, Johnston SL, Openshaw PJ. Microbes and mucosal immune responses in asthma. Lancet 381: 861–873, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holinka CF, Tseng YC, Finch CE. Prolonged gestation, elevated preparturitional plasma progesterone and reproductive aging in C57BL/6J mice. Biol Reprod 19: 807–816, 1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jazwinska A, Badakov R, Keating MT. Activin-betaA signaling is required for zebrafish fin regeneration. Curr Biol 17: 1390–1395, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kanther M, Sun X, Muhlbauer M, Mackey LC, Flynn EJ 3rd, Bagnat M, Jobin C, Rawls JF. Microbial colonization induces dynamic temporal and spatial patterns of NF-kappaB activation in the zebrafish digestive tract. Gastroenterology 141: 197–207, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kyritsis N, Kizil C, Zocher S, Kroehne V, Kaslin J, Freudenreich D, Iltzsche A, Brand M. Acute inflammation initiates the regenerative response in the adult zebrafish brain. Science 338: 1353–1356, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laing KJ, Purcell MK, Winton JR, Hansen JD. A genomic view of the NOD-like receptor family in teleost fish: identification of a novel NLR subfamily in zebrafish. BMC Evol Biol 8: 42, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lambrecht BN, Hammad H. Asthma: the importance of dysregulated barrier immunity. Eur J Immunol 43: 3125–3137, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lee Y, Grill S, Sanchez A, Murphy-Ryan M, Poss KD. Fgf signaling instructs position-dependent growth rate during zebrafish fin regeneration. Development 132: 5173–5183, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lepilina A, Coon AN, Kikuchi K, Holdway JE, Roberts RW, Burns CG, Poss KD. A dynamic epicardial injury response supports progenitor cell activity during zebrafish heart regeneration. Cell 127: 607–619, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marjoram L, Alvers A, Deerhake ME, Bagwell J, Mankiewicz J, Cocchiaro JL, Beerman RW, Willer J, Sumigray KD, Katsanis N, Tobin DM, Rawls JF, Goll MG, Bagnat M. Epigenetic control of intestinal barrier function and inflammation in zebrafish. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 112: 2770–2775, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Martin JS, Renshaw SA. Using in vivo zebrafish models to understand the biochemical basis of neutrophilic respiratory disease. Biochem Soc Trans 37: 830–837, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mathias JR, Dodd ME, Walters KB, Yoo SK, Ranheim EA, Huttenlocher A. Characterization of zebrafish larval inflammatory macrophages. Dev Comp Immunol 33: 1212–1217, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moyes DL, Runglall M, Murciano C, Shen C, Nayar D, Thavaraj S, Kohli A, Islam A, Mora-Montes H, Challacombe SJ, Naglik JR. A biphasic innate immune MAPK response discriminates between the yeast and hyphal forms of Candida albicans in epithelial cells. Cell Host Microbe 8: 225–235, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Poss KD, Shen J, Nechiporuk A, McMahon G, Thisse B, Thisse C, Keating MT. Roles for Fgf signaling during zebrafish fin regeneration. Dev Biol 222: 347–358, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Poss KD, Wilson LG, Keating MT. Heart regeneration in zebrafish. Science 298: 2188–2190, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rastrick JMD, Stevenson CS, Eltom S, Grace M, Davies M, Kilty I, Evans SM, Pasparakis M, Catley MC, Lawrence T, Adcock IM, Belvisi MG, Birrell MA. Cigarette smoke induced airway inflammation is independent of NF-kappaB signalling. PLoS One 8: e54128, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Renshaw SA, Loynes CA, Elworthy S, Ingham PW, Whyte MKB. Modeling inflammation in the zebrafish: how a fish can help us understand lung disease. Exp Lung Res 33: 549–554, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Renshaw SA, Loynes CA, Trushell DMI, Elworthy S, Ingham PW, Whyte MKB. A transgenic zebrafish model of neutrophilic inflammation. Blood 108: 3976–3978, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Renshaw SA, Trede NS. A model 450 million years in the making: zebrafish and vertebrate immunity. Dis Model Mech 5: 38–47, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Richardson R, Slanchev K, Kraus C, Knyphausen P, Eming S, Hammerschmidt M. Adult zebrafish as a model system for cutaneous wound-healing research. J Invest Dermatol 133: 1655–1665, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rombough P. Gills are needed for ionoregulation before they are needed for O2 uptake in developing zebrafish, Danio rerio. J Exp Biol 205: 1787–1794, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stein C, Caccamo M, Laird G, Leptin M. Conservation and divergence of gene families encoding components of innate immune response systems in zebrafish. Genome Biol 8: R251, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tobe M, Isobe Y, Tomizawa H, Nagasaki T, Takahashi H, Fukazawa T, Hayashi H. Discovery of quinazolines as a novel structural class of potent inhibitors of NF-kappa B activation. Bioorg Med Chem 11: 383–391, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tully JE, Hoffman SM, Lahue KG, Nolin JD, Anathy V, Lundblad LKA, Daphtary N, Aliyeva M, Black KE, Dixon AE, Poynter ME, Irvin CG, Janssen-Heininger YMW. Epithelial NF-kappaB orchestrates house dust mite-induced airway inflammation, hyperresponsiveness, and fibrotic remodeling. J Immunol 191: 5811–5821, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.van der Vaart M, Spaink HP, Meijer AH. Pathogen recognition and activation of the innate immune response in zebrafish. Adv Hematol 2012: 159807, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.van der Vaart M, van Soest JJ, Spaink HP, Meijer AH. Functional analysis of a zebrafish myd88 mutant identifies key transcriptional components of the innate immune system. Dis Model Mech 6: 841–854, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wynn TA. Common and unique mechanisms regulate fibrosis in various fibroproliferative diseases. J Clin Invest 117: 524–529, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wynn TA. Integrating mechanisms of pulmonary fibrosis. J Exp Med 208: 1339–1350, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]