Aging is associated with changes to the biomechanical properties of parenchymal arterioles and posterior cerebral arteries; this could compromise cerebrovascular health and increase the risk of stroke and dementia. Our studies are novel because of the advanced age of the mice studied and the analysis of the parenchymal arterioles.

Keywords: aging, cerebrovascular circulation, remodeling, vasculature

Abstract

Artery remodeling, described as a change in artery structure, may be responsible for the increased risk of cardiovascular disease with aging. Although the risk for stroke is known to increase with age, relatively young animals have been used in most stroke studies. Therefore, more information is needed on how aging alters the biomechanical properties of cerebral arteries. Posterior cerebral arteries (PCAs) and parenchymal arterioles (PAs) are important in controlling brain perfusion. We hypothesized that aged (22–24 mo old) C57bl/6 mice would have stiffer PCAs and PAs than young (3–5 mo old) mice. The biomechanical properties of the PCAs and PAs were assessed by pressure myography. Data are presented as means ± SE of young vs. old. In the PCA, older mice had increased outer (155.6 ± 3.2 vs. 169.9 ± 3.2 μm) and lumen (116.4 ± 3.6 vs. 137.1 ± 4.7 μm) diameters. Wall stress (375.6 ± 35.4 vs. 504.7 ± 60.0 dyn/cm2) and artery stiffness (β-coefficient: 5.2 ± 0.3 vs. 7.6 ± 0.9) were also increased. However, wall strain (0.8 ± 0.1 vs. 0.6 ± 0.1) was reduced with age. In the PAs from old mice, wall thickness (3.9 ± 0.3 vs. 5.1 ± 0.2 μm) and area (591.1 ± 95.4 vs. 852.8 ± 100 μm2) were increased while stress (758.1 ± 100.0 vs. 587.2 ± 35.1 dyn/cm2) was reduced. Aging also increased mean arterial and pulse pressures. We conclude that age-associated remodeling occurs in large cerebral arteries and arterioles and may increase the risk of cerebrovascular disease.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY

Aging is associated with changes to the biomechanical properties of parenchymal arterioles and posterior cerebral arteries; this could compromise cerebrovascular health and increase the risk of stroke and dementia. Our studies are novel because of the advanced age of the mice studied and the analysis of the parenchymal arterioles.

aging is characterized by a decline in many physiological and vascular functions (5). Artery dysfunction (23) is an important factor in cardiovascular diseases such as hypertension, atherosclerosis, and cerebral artery disease, which are major causes of mortality in the elderly (36). The incidence of cardiovascular and cerebrovascular disease increases significantly with age; this is especially true for stroke and heart failure (24, 25). The remodeling of arteries that occurs with age may contribute to this association between age and cardiovascular disease (31). The term “artery remodeling” refers to stable changes in artery diameter and wall structure; inward remodeling is a reduction in lumen diameter while outward remodeling refers to an increase in lumen diameter. Hypertrophic remodeling occurs when wall area is increased, while hypotrophic remodeling is a reduction in wall area (41, 59). Age-related cerebral artery remodeling could increase the risk of cerebrovascular accidents especially in situations where other risk factors, such as hypertension, are present (48). Therefore it is important to fully understand the effects of aging on cerebral artery structure.

The Stroke Treatment Academic Industry Roundtable (12a) recommendations for preclinical testing state that potential neuroprotective agents should be tested in aged animals. The effects of aging on peripheral arteries have been documented (25, 26). Aged atherosclerotic mice exhibit outward remodeling of the aorta compared with young mice (39). Artery stiffness increases with age in the rat aorta and small mesenteric arteries (27, 31). Hypertrophy of the artery wall has also been observed in small mesenteric arteries from aged rats (1, 27, 35). Aging also causes endothelial dysfunction in arteries from different vascular beds. Endothelial function is impaired in aorta, carotid, and basilar arteries from 18- and 24-mo-old mice (6, 10, 34). Interestingly, the basilar artery had the most impaired function and the authors attributed this to increased reactive oxygen species production and oxidative stress (34, 47). These studies suggest that the effects of aging on the peripheral and cerebral circulation are different; therefore we cannot assume that the effects of aging in the periphery will translate to the brain.

Cerebral artery autoregulation is an important mechanism to maintain cerebral blood flow within a normal range. The effects of aging on autoregulation are controversial. Recent studies in 24 mo C57Bl/6 mice show that aging impairs the ability of the cerebral arteries to autoregulate (52). This has also been observed in clinical studies (8). However, other studies suggest aging has no effect on autoregulation. A recent study in elderly people with mild cognitive impairment showed that low blood pressure was not associated with reduced cerebral blood flow (15). This suggests that in these patients autoregulation is normal. Similar findings have also been made in a younger population (54).

Cerebral arterioles interact with neurons, astrocytes, and glial cells to form the neurovascular unit, which coordinates coupling between neural activity and local cerebral flow. Therefore cerebral arteries may behave differently from arteries in the peripheral circulation (28). The goal of our study was to characterize the effects of aging on the biomechanical properties of the posterior cerebral artery (PCA) and parenchymal arterioles (PAs) and to assess the differential effects of aging on the microcirculation and the large pial arteries. We hypothesized that aging would impair the biomechanical properties of the PCA and the PAs resulting in outward artery remodeling and increased artery stiffness. The PCA regulates blood flow and pressure to the posterior cerebral circulation. The PCAs arise from the basilar artery and supply the midbrain, basal nucleus, and thalamus, among other structures (22). The PCA is used as a model of a large pial artery. It is frequently studied in mice because it is more amenable to pressure myography studies than the middle cerebral artery (MCA), which is highly branched. The PAs arise from the pial arteries, via the penetrating arterioles, which are located in the Virchow-Robin space. PAs studied were branching off the MCA and were 1–2 mm downstream the Virchow-Robin space; these arterioles are in direct contact with the brain parenchyma. Unlike the MCA or PCA, the PAs have few branches. The PAs play a critical role in controlling blood flow and pressure in the cerebral microcirculation and are important in determining overall cerebrovascular resistance (12). PAs are composed of endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells, but they are different from pial arteries and arteries in peripheral vascular beds in that they lack extrinsic innervation (9).

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal model.

All experimental protocols were approved by the Michigan State University Animal Care and Use Committee and were performed in accordance with the American Physiological Society's Guiding Principles in the Care and Use of Animals. Male C57Bl/6 mice purchased from the National Institute of Aging at Charles River Laboratories were housed on 12:12-h light/dark cycle with food and water ad libitum. Mice were studied at 3–5 mo (young) and 22–24 mo (old) of age. For pressure myography studies, mice were euthanized by CO2 asphyxiation followed by cervical dislocation and decapitation.

Telemetry.

Blood pressure was measured by telemetry as described previously (62). Mice were anesthetized with 3% isoflurane/1% oxygen for implantation of a catheter attached to a radiotelemetry transmitter (Data Sciences International, St Paul, MN) in the abdominal aorta via the femoral artery; the transmitter body was placed subcutaneously. Mice were allowed to recover for 3 days and then mean, systolic, and diastolic arterial pressures were measured continuously (10 s averages collected every 10 min, 24 h/day). Data were expressed as the 1- or 24-h averages of systolic, diastolic, mean arterial pressure, and pulse pressure (systolic pressure − diastolic pressure). We report the latter because it is an independent risk factor for cardiovascular disease.

Pressure myography.

The brain was collected at euthanasia and the biomechanical properties of isolated PCA and PAs were assessed by pressure myography as described previously (42–45). To dissect the PAs, a 5 × 3 mm section of brain containing the MCA was isolated. Then the pia with the MCA was separated from the brain and the PAs branching from the MCA were used for experiments (43). The PAs we studied were branching off the MCA and were located 1–2 mm downstream the Virchow-Robin space. PCAs and PAs were mounted between two glass micropipettes in a custom-made cannulation chamber (61). A servo-null system was used to pressurize the arteries and arterioles. Arteries and arterioles were equilibrated in physiological salt solution (PSS) containing (in mM) 141.9 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 1.12 KH2PO4, 1.7 MgSO4·7H2O, 10 HEPES, and 5 dextrose under zero-flow conditions at 37°C. Ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA; 2 mM) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP; 10−5 M) were added to maintain the smooth muscle in a relaxed state. A leak-test was performed prior to each experiment; any artery that could not maintain its intraluminal pressure (60 mmHg for the PCA and 40 mmHg for the PAs) was discarded. A pressure-response curve was constructed by increasing the intraluminal pressure from 0 to 120 mmHg at 20-mmHg increments. The PCAs and PAs were equilibrated at each pressure for 5 min, then lumen and outer diameters were measured using a 10× objective (Nikon Plan objective; Numerical Aperture: 0.25) with a Nikon Eclipse TS100 microscope. The average of the outer and lumen diameter at each pressure was recorded using MyoVIEW II 2.0 software (Danish Myo Technology, Aarhus, Denmark). These measures were compared and used to calculate wall thickness (outer diameter − lumen diameter). Wall cross-sectional area was calculated using the formula “artery area − lumen area”. The wall-to-lumen ratio, wall stress, strain, and distensibility were calculated as described previously (4). Wall stiffness was quantified using the β-coefficient calculated from the individual stress-strain curves using the model (y = aeβx), where y is wall stress, x is wall strain, a is the intercept and β is the slope of the exponential fit; a higher β-coefficient represents a stiffer vessel.

Immunofluorescence.

Quantification of artery and capillary numbers in young and aged mice was performed by immunofluorescence (IF) staining of the endothelial cell marker isolectin GS-IB4. Mice were transcardially perfused with 100 ml of PSS containing 2.8 mM calcium plus 1,000 UI/ml heparin sodium salt, 10−4 M SNP, and 10−5 M diltiazem to maximally dilate the cerebral vasculature. The perfusion pressure was maintained at 60 mmHg. Following perfusion with PSS, mice were perfusion-fixed with 60 ml of 4% formaldehyde. Brains were removed and postfixed in 4% formaldehyde for 48 h. Brains were then washed twice in 0.01 M phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and placed in 20% sucrose-PBS solution for cryosectioning. Cryosections (20 μm thick) were incubated overnight in 0.01 mg/ml isolectin GS-IB4 Alexa Fluo-568 conjugate (Invitrogen, Cambridge, CA) at 4°C. This is a conjugated lectin; therefore incubation with a secondary antibody was not necessary. The next day, sections were washed 4× in 0.01 M PBS (5 min each wash) and coverslips were mounted using Prolong antifade reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) (21). Two fields of the premotor cortex, one in each hemisphere, more specifically in the second and third layers of the neocortex, were acquired using a 20× objective (UPLSAPO 20X NA: 0.75) coupled to an inverted Olympus Confocal Laser Scanning microscope (Olympus America, Central Valley, PA) with Olympus Fluoview FV1000 (Olympus America). All images were acquired using the red fluorescent dye Alexa Fluor 568 that has an excitation wavelength of 578 nm and an emission wavelength of 603 nm. Sections without the isolectin served as negative controls. For the quantification of the vessel density 3D volume reconstruction of the z-stacks were made. We rotated the 3D volume reconstruction to better visualize when a vessel started and where it ended to make sure we were not counting the same vessel twice. We also used a grid to make sure we were counting the vessel correctly and not twice. We did not have software available to do the quantification of the vessels; therefore all the quantifications were done manually by the investigator using ImageJ (46).

Calcium and collagen staining.

The Investigative Histology Laboratory at Michigan State University performed staining for calcium and collagen in the cerebral arteries. Calcification of the intraparenchymal arteries was assessed using the Von Kossa stain (33). Six random fields were acquired to count the number of positive vessels that contained calcium deposits. Masson's Trichrome stain was used to stain collagen in the cerebral arteries (7). Six fields were acquired to quantify the amount of collagen deposition in the vessels. Images were acquired using an Axioskop 40 (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany) coupled to a camera (AxioCam MRc5 Carl Zeiss) with the AxioVision Rel 4.6 software (Carl Zeiss Imaging Solutions, Gottingen, Germany). A blinded investigator analyzed images.

Statistical analyses.

All data are presented as means ± SE. Body weight, blood pressure, calcium and collagen deposition, and vessel quantification data were analyzed by Student's t-test. For analysis of artery structure, two-way analysis of variance was utilized followed by Bonferroni t-test for post hoc comparison of the means. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 6.0 software (GraphPad, San Diego, CA). In all cases statistical significance was denoted by P < 0.05.

Drugs and chemicals.

All drugs and chemicals were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) unless otherwise stated.

RESULTS

Physiological measures.

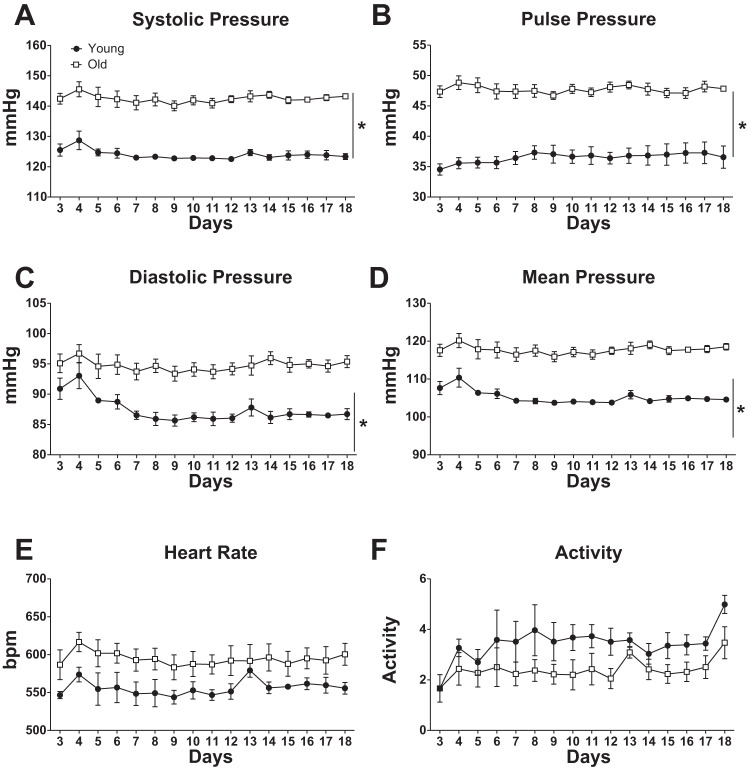

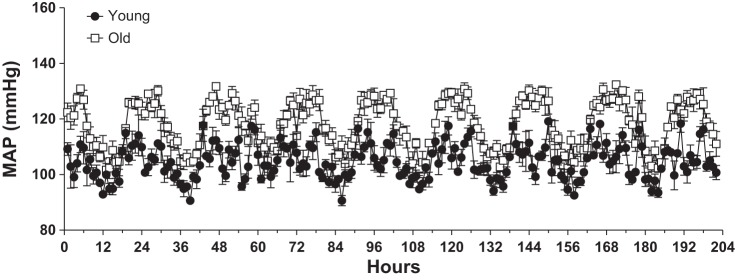

Old mice were significantly heavier than the young mice (31.02 ± 1.57 vs. 34.79 ± 1.09 g; young vs. old). Blood pressure, measured by telemetry, showed that in our cohort of mice, advanced age was associated with higher systolic, diastolic, mean, and pulse pressures (Fig. 1, A–D). However, we observed no significant effect of age on heart rate or activity (Fig. 1, E and F). The higher blood pressure in older mice resulted mainly from substantial differences in blood pressure during the night-time when the animals are most active (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Aging increases blood pressure with no change in heart rate. Data are means ± SE (n = 4 for Young and n = 3 for Old) of 24-h averages of blood pressure or heart rate, as indicated, measured by telemetry. Two-way ANOVA indicated significant effects of age for all blood pressures (A–D) (*P < 0.05), but not for heart rate (E) or activity (F) (P > 0.05). Blood pressure data recording started on day 3 after telemeter implantation.

Fig. 2.

Night-time blood pressures are elevated in aged mice. Data are means ± SE (n = 4 for Young and n = 3 for Old) of 1-h averages of mean arterial pressure (MAP) for the last 8 days of the data shown in Fig. 1 showing substantially elevated night-time blood pressures in the aged mice. The 0-h time point represents the first midnight of the time period shown. Two-way ANOVA indicated significant effects of time and age, with a significant interaction term (P < 0.05 for each).

Biomechanical properties of the posterior cerebral artery and penetrating arterioles.

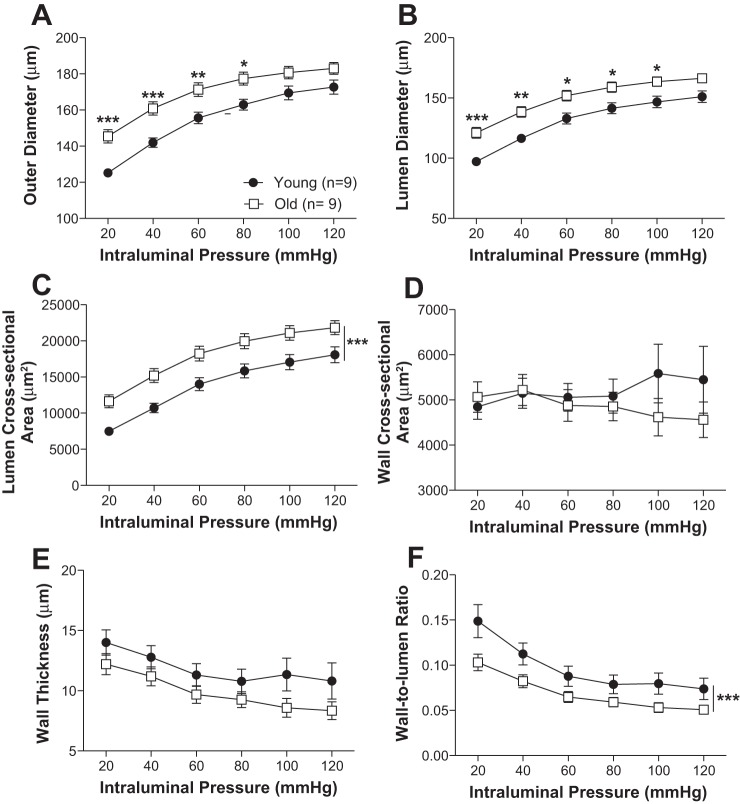

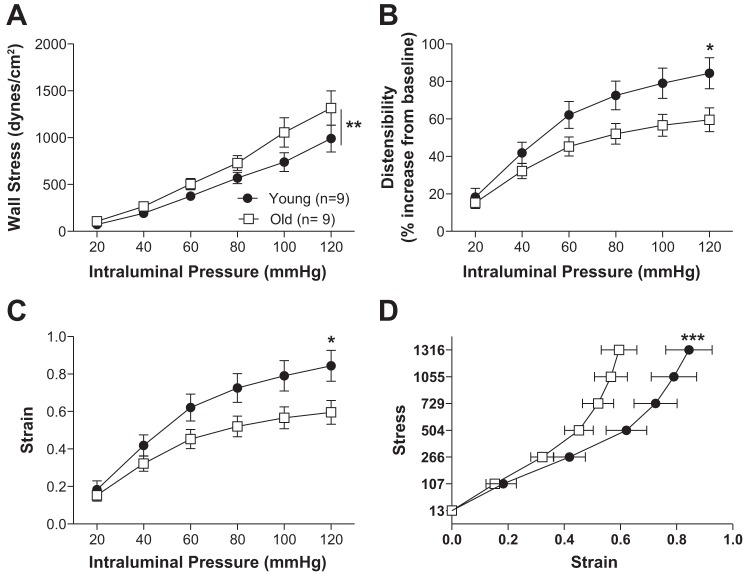

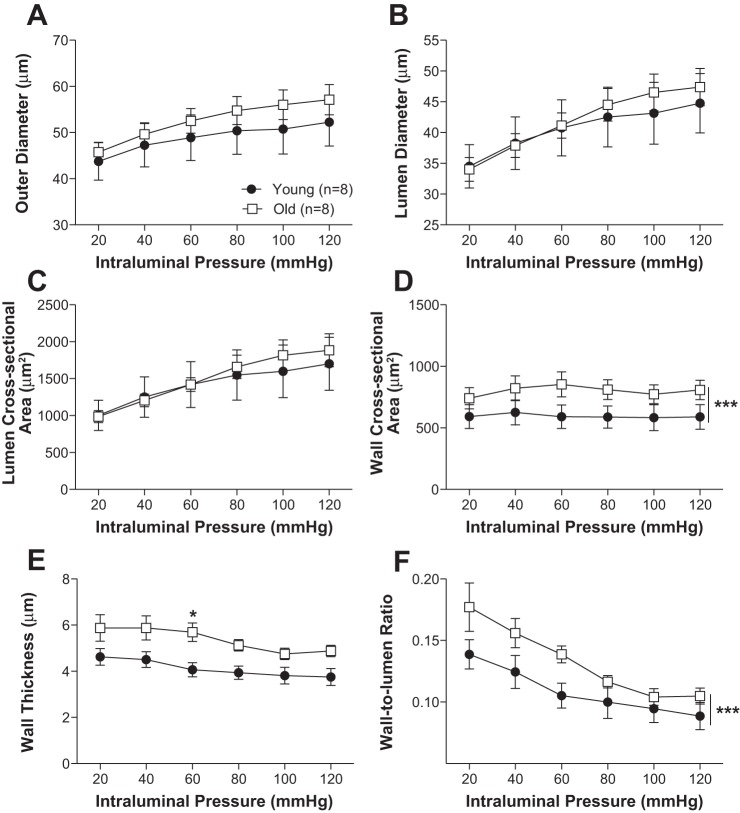

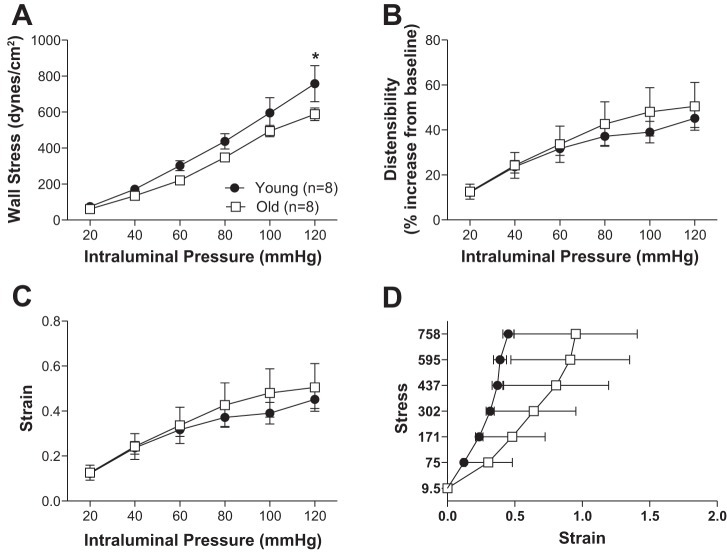

Older mice had increased PCA outer and lumen diameter (Fig. 3, A and B). Lumen cross-sectional area was also larger in the old mice (Fig. 3C). No significant differences between young and old mice were observed in the wall thickness and cross-sectional area (Fig. 3, D and E). Older mice showed decreased wall-to-lumen ratio (Fig. 3F). The mechanical properties of the arteries differed with age. Wall stress was higher in old mice (Fig. 4A) while wall strain, distensibility, and stress vs. strain were lower in PCAs from old mice (Fig. 4, B–D).

Fig. 3.

Aging results in posterior cerebral artery remodeling. Outer diameter (A), lumen diameter (B), and lumen area (C) were increased with age. Wall cross-sectional area and thickness were not changed (D, E). Aging did decrease wall-to-lumen ratio (F). Data are presented as means ± SE. ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni for post hoc comparisons.

Fig. 4.

Posterior cerebral artery (PCA) mechanical properties were changed with aging. Wall stress was increased (A) with age. Aging also decreased strain in the PCA (C). The PCA was less distensible with age (B). Wall stress vs. strain was reduced in the older mice (D). Data are presented as mean ± SE; ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni for post hoc comparisons. Data from Fig. 3 were used to calculate the mechanical properties of the PCA.

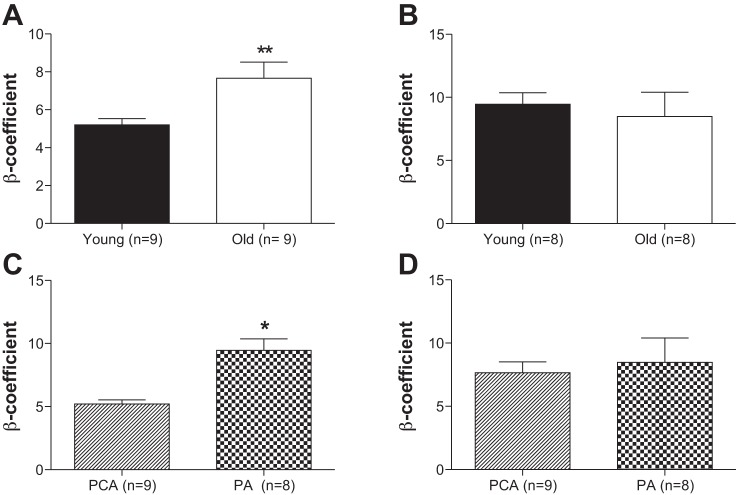

Aging was also associated with PA remodeling (Figs. 5 and 6). Wall thickness, cross-sectional area, and wall-to-lumen ratio were larger in PAs from old mice compared with young. No other significant differences in artery structure were observed. Older mice had greater wall stiffness in the PCAs (Fig. 7A) but not the PAs (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 5.

Aging increases wall thickness in the penetrating arterioles. Outer diameter (A), lumen diameter (B), and lumen area (C) of the penetrating arterioles were not significantly changed with aging. Wall cross-sectional area (D), wall thickness (E), and wall-to-lumen ratio (F) were increased with age. Data are presented as means ± SE. ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA.

Fig. 6.

Aging resulted in changes to the mechanical properties of the penetrating arterioles. At 120 mmHg, wall stress was increased with age (A). Wall strain (C), distensibility (B), and stress-strain (D) were unchanged. Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni for post hoc comparisons. Data from Fig. 5 were used to calculate the mechanical properties of the PCA.

Fig. 7.

Aging increases vascular stiffness in the posterior cerebral artery, and vascular stiffness is different depending on the type of artery. Wall stiffness is increased with aging in the posterior cerebral artery (A) but not in the penetrating arterioles (B). An increased β-coefficient represented increased wall stiffness. In young mice vascular stiffness is increased in the small arteries compared with large arteries (C). This was not the case in old mice (D). PA, parenchymal arterioles. Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, Student's t-test. Data from Fig. 4 and 7 were used to calculate the mechanical properties of the PCA.

We compared arterial stiffening between the PCA and PAs in young and old mice separately. In the young mice, the PAs were stiffer than the PCAs (Fig. 7C). No differences in stiffness were observed between the PCAs and PAs from the old mice (Fig. 7D).

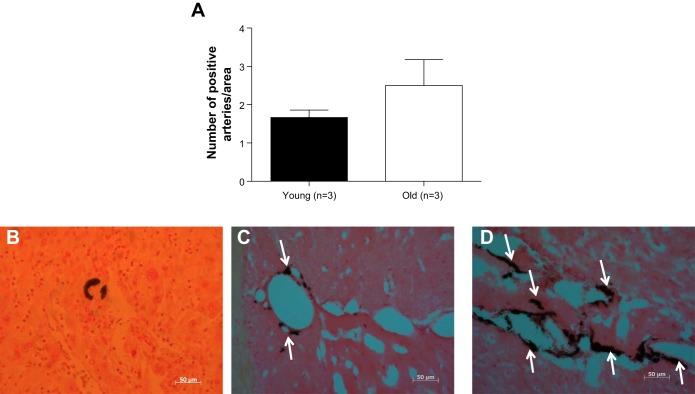

Calcium and collagen in the arterial wall.

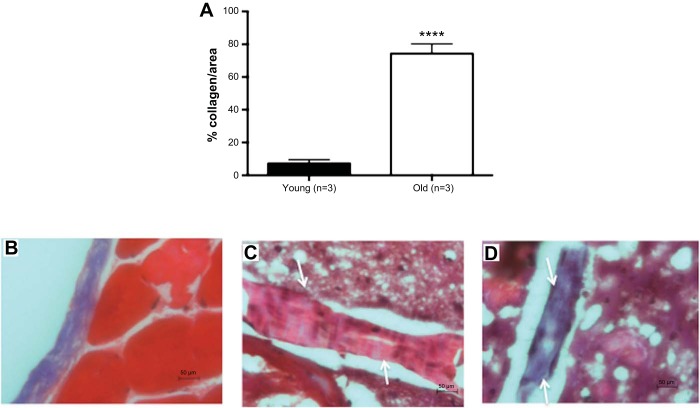

In a small cohort of mice, we observed that older mice did not have a significantly greater number of cerebral arteries with increased calcium deposits in the wall (P = 0.3) (Fig. 8A). However, as shown in the representative images, it appears that the percentage of calcification in the individual cerebral arteries from old mice is greater (Fig. 8, C and D). Arteries from old mice had more collagen deposition (Fig. 9A). Representative images are shown (Fig. 9, B–D).

Fig. 8.

Aging may increase calcium content in the wall of cerebral arteries. In a small cohort of mice, arteries with calcium deposits were counted in young and old mice. The amount of vessel with calcium deposits or the increase in the percentage of calcification (data not shown) was not significantly different between both groups (A). Representative images at 40× magnification are shown (B: positive control; C: young mouse; D: old mouse). The arrows indicate the arteries. Data are presented as means ± SE. P = 0.3 by Student's t-test; n = 3.

Fig. 9.

Aging increases the percent of collagen deposition in cerebral arteries. In a small cohort of mice, the percentage of collagen deposits in the wall of young and old mice was quantified. Aging resulted in a significant increase in collagen deposition (A). Representative images at 40× magnification are shown (B: positive control; C: young mouse; D: old mouse). The arrows indicate the artery. An artery with increase collagen content will be stained purple. Data are presented as means ± SE. ****P < 0.001 by Student's t-test; n = 3.

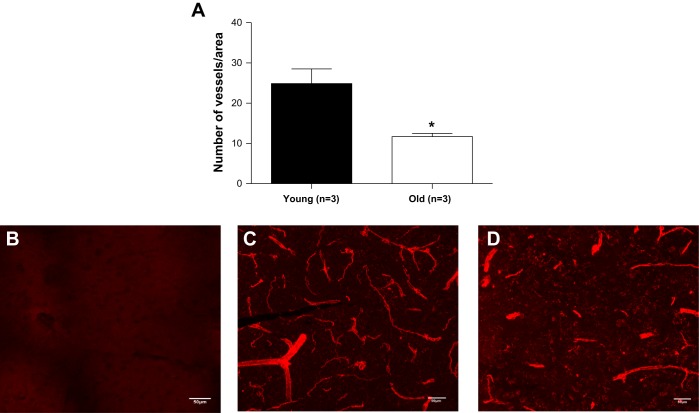

Artery and capillary density in the cerebral cortex.

Artery and capillary density was quantified using the endothelial cell marker Isolectin IB-4. Two fields of the neocortex, one in each hemisphere, were acquired. In a small cohort of mice, we observed that old mice had significantly fewer arteries and capillaries in the cerebral cortex (Fig. 10).

Fig. 10.

Aging decreases artery density. In a small cohort of mice, the amount of arteries and capillary number was quantified using Isolectin-IB4. In each animal, two images were acquired in the neocortex, one per hemisphere. Representative images are shown above. B: control; C: young; D: old. Data are presented as means ± SE. *P < 0.05, Student's t-test; n = 3.

DISCUSSION

The novel finding of our study is that aging is associated with changes in the biomechanical properties of the PCA and PAs. The effects of aging on the biomechanical properties of the posterior cerebral circulation and smaller cerebral arterioles have not been widely characterized (29). The PCA was utilized as a model of a large pial artery. The PCA is important for regulating the blood flow to the posterior cerebral circulation. The PAs serve as a bottleneck for perfusion of the neocortex (41). PAs also play an important role in determining the outcome of ischemia; however, these arterioles have not been well characterized (9, 21, 43) and the effects of aging have not been assessed. In the PCAs, aging was associated with an increase in the outer and lumen diameter and a decrease in wall-to-lumen ratio. Aging was also associated with increased wall stress and stiffness. However, wall strain and distensibility were decreased with age in the PCAs. In the PAs, no changes in the size of the artery were observed but aging was associated with changes to the wall structure. The wall area, wall thickness, and wall-to-lumen ratio of the PAs were increased with age while wall stress was reduced.

The increase in the lumen diameter of the PCA we observed with age could increase cerebral blood flow and cause hyperemia. This could be compensated for by increased myogenic tone. We did not measure myogenic tone in this study, but studies in aged mice treated with angiotensin II show age, combined with hypertension, causes a loss of myogenic tone and autoregulation in the MCA (52). Loss of myogenic tone in a large artery such as the MCA increases the risk of rupture of the PAs with fluctuations in blood pressure. In the PAs, the increased wall thickness without changes in wall stress we observed could be a positive adaptation to protect these arterioles from rupture and vascular damage.

One of the strengths of our study is the advanced age of the mice in the aged group. At 24 mo old the mice used in this study were close to the end of their natural lifespan; therefore these mice truly model the geriatric population. The use of telemetric blood pressure recording in this study also is a strength because it is a more accurate technique to measure blood pressure than tail-cuff plethysmography. We also avoided the carotid catheterization approach used in many mouse telemetry studies because it may artificially alter blood pressure by affecting baroreflex function. Our studies show that mean arterial pressure and pulse pressure were increased with age. This is in contrast to studies using tail-cuff plethysmography which suggest that aging does not affect (52) or reduces (19) blood pressure. However, our studies are in agreement with clinical studies showing that blood pressure increases with age (20, 40, 58, 55). Pulse pressure was markedly increased in the aged mice; this could lead to vascular cognitive impairment (17, 32, 56).

The higher day-night blood pressure ratio that we observed in older mice (Fig. 2) is notable because this ratio is known to be an independent predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in humans even after adjustment for 24 h average blood pressure (11). A caveat to our study is that we do not know when blood pressure became elevated in the aged mice because blood pressure was only measured at the 24-mo time point. Age alters the ability of cerebral arteries to adapt to hypertension. Cerebral arteries from young mice have the ability to functionally and structurally adapt to hypertension (38, 52). However, the MCAs from 24-mo-old mice have an impaired ability to respond to hypertension (51). Our studies show that age results in high blood pressure. Therefore, it is possible that the ability of the PCA and PAs from old mice to adapt to hypertension is impaired. It is also important to note that in our study we observed outward remodeling which is the opposite of what we would expect with hypertension (41). It should be noted that angiotensin II-induced hypertension is likely to have a more rapid onset than an aging-associated blood pressure change; with a more gradual increase in blood pressure the mechanisms of artery remodeling may be different.

Our preliminary studies of a small cohort of mice suggest that the ageing process also resulted in artery rarefaction, that is, a decrease in the vessel density in the brain. Cerebral artery rarefaction has been observed in some models of hypertension (37, 49) and aging (52). A reduction in the number of vessels in the brain could lead to chronic hypoperfusion (28). We also show that aging increases pulse pressure and this has been associated with artery rarefaction (50, 52). However, we do not know if the changes in PCA and PA structure observed are a causative factor in the artery rarefaction or if remodeling and rarefaction occur independent of each other.

We observed increased stiffness in the PCA but not in the PAs, suggesting that age-associated changes in stiffness are different in small arterioles and large cerebral arteries. The increases in stiffness in the PCA could have been a result of higher mean arterial pressure or pulse pressure in the older mice rather than aging per se. In rat models of essential hypertension, the large cerebral arteries remodel first; this presumably serves to protect the smaller downstream arteries from the increased pressure (28). The small arteries remodel after a prolonged period of hypertension (28). It is possible that the same pattern of remodeling occurs with aging and that the cerebral artery remodeling we observed was a consequence of both aging and increased blood pressure. Further studies will be required to determine if cerebral artery stiffness in the aged mice is caused by aging itself or by increased blood pressure. Increased arterial stiffness is a hallmark of artery dysfunction and an independent predictor of cardiovascular disease (16). In peripheral arteries, aging has been associated with changes in the composition and organization of the arterial wall that increase artery stiffness (13). We observed an increase in stiffness of the PCA without an increase in wall thickness suggesting that increased stiffness is the result of changes in extracellular matrix composition.

Collagen and elastin are important components of the extracellular matrix (14), and they play key roles in maintaining the strength and elasticity of the arterial wall. With normal aging, collagen and elastin expression is differentially regulated (13) such that the increased stiffness in large arteries is associated with increased collagen and reduced elastin deposition (30, 53). The increase in collagen deposition could alter the mechanical properties of the artery wall resulting in stiffening. Mandala et al. (29) showed that in adult normotensive rats the amount of elastin in the PCA was reduced compared with young rats but no changes in collagen were observed. Our findings suggest that collagen deposition is increased with aging in the penetrating arterioles. The discrepancy between these studies can be attributed to the age and strain of the animals; Mandala et al. studied 11- to 12-mo-old Sprague Dawley rats, while we studied mice that better represent the geriatric population (22–24 mo old). The elastin fragmentation that occurs with increased age is associated with increased expression of the matrix metalloproteases (MMP) (18, 53, 57). MMP-2 and -9 in particular have been associated with elastin calcification (2, 3). The ageing process also increases the amount of calcium and phosphate in the wall (63, 64). This is associated with the calcification of the elastic fibers and could contribute to artery wall stiffness. We found that the amount of calcium in the wall and the number of arteries with calcium deposits might be increased with ageing but our data did not reach statistical significance. We recognize that these studies were underpowered (n = 3) but the number of aged mice was limited; therefore further studies will be required.

Liu et al. (28) showed that aged mice have smaller infarct size after an ischemic stroke than young mice. Interestingly, however, the functional impairments in old mice post-stroke were much worse. Post-stroke the cerebral arteries are maximally dilated such that flow is proportional to the lumen diameter. Our studies showed that advancing age is associated with increased lumen and artery cross-sectional area of the PCA. This could be the cause of the smaller infarct observed in aged rats. The magnitude of the increase between the outer and lumen diameter was different. The change with aging was greater for the outer diameter of the PCA and this is likely the cause of the increase in artery stiffness. Wall thickness of the PCA was not changed with age but it was increased in the PAs. This difference implies that missing protection from high intraluminal pressure in pial arteries is associated with increased wall thickness of the downstream arterioles. In the PAs, wall thickening with age is probably a result of smooth muscle cell hypertrophy (30). Our results are consistent with previous findings showing that in human conduit arteries such as the aorta, iliac arteries and carotid arteries, aging is associated with increased lumen area and wall thickening (53). Our studies also show that aged mice have higher wall cross-sectional area in the PCA and PAs than do young mice. In contrast, in aged Fischer rats the wall cross-sectional area of the pial arteries was less than in young animals (19). Aging also altered the mechanical properties of the PCA resulting in a less distensible artery and decreased wall strain. This is consistent with the work of Hadju et al. (19), in the pial arteries of 24-mo-old Fischer rats. However, in another study the distensibility of the MCA from 24-mo-old mice was not changed (50). The reduced distensibility we observed may be also associated with alterations of the artery stiffness.

A limitation to our study is that we did not study the development of spontaneous myogenic tone or endothelial dysfunction with age. However, it is known that aging is associated with endothelial dysfunction in the basilar artery through a reactive oxygen species-dependent mechanism (34, 47). Aging also impairs the ability of the MCA to generate tone in response to static (52) and pulsatile pressure (50). Another limitation of our studies is that we did not assess the mechanism of artery remodeling; this is a topic for future study. Possible mechanisms involve changes in the arrangement of the smooth muscle cells, increases in the expression of MMPs such as MMP-2 and -9, and elastin fragmentation. We did show that the cerebral arteries of aged mice have increased collagen that could have an important role in the changes in the artery wall observed.

In summary, aging is associated with structural changes that increase the wall stiffness of the PCA and wall stress and wall thickness of the PAs; combined, these changes could result in a dysregulation of cerebral blood flow that would increase the risk of stroke and dementia. The vasculature is a potential therapeutic target for stroke, and potential neuroprotective or neurorestorative therapies need a functioning vasculature to deliver the drug to the site of injury. Therefore, it is important to fully understand the mechanisms of age-associated cerebral artery remodeling to improve cerebrovascular health. For practical reasons all of our studies were conducted in male mice; therefore, further studies should be conducted in female mice to evaluate sex differences. In future studies we should assess if aging impairs vascular tone of the cerebral arteries and if the age-associated changes in cerebral artery structure are caused by the increased blood pressure or aging itself.

GRANTS

This study was supported by National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant PO1-HL-070687 to G. D. Fink and W. F. Jackson and American Heart Association Grant 13GRNT17210000 to A. M. Dorrance. J. M. Diaz-Otero was supported by National Institutes of Health Grant 5T32-GM-092715-04.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: J.M.D.-O. and H.G. performed experiments; J.M.D.-O. and W.F.J. analyzed data; J.M.D.-O., G.D.F., W.F.J., and A.M.D. interpreted results of experiments; J.M.D.-O. and W.F.J. prepared figures; J.M.D.-O. drafted manuscript; J.M.D.-O., G.D.F., W.F.J., and A.M.D. edited and revised manuscript; J.M.D.-O., H.G., G.D.F., W.F.J., and A.M.D. approved final version of manuscript; A.M.D. conception and design of research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge the Investigative Histology Laboratory at Michigan State University for technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adrian M, Laurant P, Berthelot A. Effect of magnesium on mechanical properties of pressurized mesenteric small arteries from old and adult rats. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 31: 306–313, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Atkinson J. [Aging of arterial extracellular matrix elastin: etiology and consequences]. Pathol Biol (Paris) 46: 555–559, 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bailey M, Pillarisetti S, Jones P, Xiao H, Simionescu D, Vyavahare N. Involvement of matrix metalloproteinases and tenascin-C in elastin calcification. Cardiovasc Pathol 13: 146–155, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baumbach GL, Hajdu MA. Mechanics and composition of cerebral arterioles in renal and spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 21: 816–826, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bonomini F, Rodella LF, Rezzani R. Metabolic syndrome, aging and involvement of oxidative stress. Aging Dis 6: 109–120, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown KA, Didion SP, Andresen JJ, Faraci FM. Effect of aging, MnSOD deficiency, and genetic background on endothelial function: evidence for MnSOD haploinsufficiency. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 27: 1941–1946, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Calderon LE, Liu S, Su W, Xie Z, Guo Z, Eberhard W, Gong MC. iPLA2beta overexpression in smooth muscle exacerbates angiotensin II-induced hypertension and vascular remodeling. PLoS One 7: e31850, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Castellani S, Bacci M, Ungar A, Prati P, Di Serio C, Geppetti P, Masotti G, Neri Serneri GG, Gensini GF. Abnormal pressure passive dilatation of cerebral arterioles in the elderly with isolated systolic hypertension. Hypertension 48: 1143–1150, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cipolla MJ, Chan SL, Sweet J, Tavares MJ, Gokina N, Brayden JE. Postischemic reperfusion causes smooth muscle calcium sensitization and vasoconstriction of parenchymal arterioles. Stroke 45: 2425–2430, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Didion SP, Kinzenbaw DA, Schrader LI, Faraci FM. Heterozygous CuZn superoxide dismutase deficiency produces a vascular phenotype with aging. Hypertension 48: 1072–1079, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fagard RH, Thijs L, Staessen JA, Clement DL, De Buyzere ML, De Bacquer DA. Night-day blood pressure ratio and dipping pattern as predictors of death and cardiovascular events in hypertension. J Hum Hypertens 23: 645–653, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Faraci FM, Heistad DD. Regulation of large cerebral arteries and cerebral microvascular pressure. Circ Res 66: 8–17, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12a.Fisher M, Feuerstein G, Howells DW, Hurn PD, Kent TA, Savitz SI, Lo EH; STAIR Group . Update of the stroke therapy academic industry roundtable preclinical recommendations. Stroke 40: 2244–2250, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fleg JL, Strait J. Age-associated changes in cardiovascular structure and function: a fertile milieu for future disease. Heart Fail Rev 17: 545–554, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fornieri C, Quaglino D Jr, Mori G. Role of the extracellular matrix in age-related modifications of the rat aorta. Ultrastructural, morphometric, and enzymatic evaluations. Arterioscler Thromb 12: 1008–1016, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Foster-Dingley JC, Moonen JE, de Craen AJ, de Ruijter W, van der Mast RC, van der Grond J. Blood pressure is not associated with cerebral blood flow in older persons. Hypertension 66: 954–960, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franklin SS. Beyond blood pressure: Arterial stiffness as a new biomarker of cardiovascular disease. J Am Soc Hypertens 2: 140–151, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, Iadecola C, Launer LJ, Laurent S, Lopez OL, Nyenhuis D, Petersen RC, Schneider JA, Tzourio C, Arnett DK, Bennett DA, Chui HC, Higashida RT, Lindquist R, Nilsson PM, Roman GC, Sellke FW, Seshadri S, American Heart Association Stroke Council, Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Council on Cardiovascular Nursing, Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention, and Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke 42: 2672–2713, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenwald SE. Ageing of the conduit arteries. J Pathol 211: 157–172, 2007.17200940 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hajdu MA, Heistad DD, Siems JE, Baumbach GL. Effects of aging on mechanics and composition of cerebral arterioles in rats. Circ Res 66: 1747–1754, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harvey A, Montezano AC, Touyz RM. Vascular biology of ageing-Implications in hypertension. J Mol Cell Cardiol 83: 112–121, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iddings JA, Kim KJ, Zhou Y, Higashimori H, Filosa JA. Enhanced parenchymal arteriole tone and astrocyte signaling protect neurovascular coupling mediated parenchymal arteriole vasodilation in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35: 1127–1136, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Krishnaswamy A, Klein JP, Kapadia SR. Clinical cerebrovascular anatomy. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 75: 530–539, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kusuda K, Ibayashi S, Sadoshima S, Ishitsuka T, Fujishima M. Brain ischemia following bilateral carotid occlusion during development of hypertension in young spontaneously hypertensive rats—importance of morphologic changes of the arteries of the circle of Willis. Angiology 47: 455–465, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lakatta EG. So! What's aging? Is cardiovascular aging a disease? J Mol Cell Cardiol 83: 1–13, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises. I. Aging arteries: a “set up” for vascular disease. Circulation 107: 139–146, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lakatta EG, Levy D. Arterial and cardiac aging: major shareholders in cardiovascular disease enterprises. II. The aging heart in health: links to heart disease. Circulation 107: 346–354, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laurant P, Adrian M, Berthelot A. Effect of age on mechanical properties of rat mesenteric small arteries. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 82: 269–275, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu F, Yuan R, Benashski SE, McCullough LD. Changes in experimental stroke outcome across the life span. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 29: 792–802, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mandala M, Pedatella AL, Morales Palomares S, Cipolla MJ, Osol G. Maturation is associated with changes in rat cerebral artery structure, biomechanical properties and tone. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 205: 363–371, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mirea O, Donoiu I, Plesea IE. Arterial aging: a brief review. Rom J Morphol Embryol 53: 473–477, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mitchell GF. Effects of central arterial aging on the structure and function of the peripheral vasculature: implications for end-organ damage. J Appl Physiol (1985) 105: 1652–1660, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mitchell GF, van Buchem MA, Sigurdsson S, Gotal JD, Jonsdottir MK, Kjartansson O, Garcia M, Aspelund T, Harris TB, Gudnason V, Launer LJ. Arterial stiffness, pressure and flow pulsatility and brain structure and function: the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility—Reykjavik study. Brain 134: 3398–3407, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizobuchi M, Finch JL, Martin DR, Slatopolsky E. Differential effects of vitamin D receptor activators on vascular calcification in uremic rats. Kidney Int 72: 709–715, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Modrick ML, Didion SP, Sigmund CD, Faraci FM. Role of oxidative stress and AT1 receptors in cerebral vascular dysfunction with aging. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 296: H1914–H1919, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moreau P, d'Uscio LV, Luscher TF. Structure and reactivity of small arteries in aging. Cardiovasc Res 37: 247–253, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ohanian J, Liao A, Forman SP, Ohanian V. Age-related remodeling of small arteries is accompanied by increased sphingomyelinase activity and accumulation of long-chain ceramides. Physiol Rep 2: 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Paiardi S, Rodella LF, De Ciuceis C, Porteri E, Boari GE, Rezzani R, Rizzardi N, Platto C, Tiberio GA, Giulini SM, Rizzoni D, Agabiti-Rosei E. Immunohistochemical evaluation of microvascular rarefaction in hypertensive humans and in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Clin Hemorheol Microcirc 42: 259–268, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Paulson OB, Strandgaard S, Edvinsson L. Cerebral autoregulation. Cerebrovasc Brain Metab Rev 2: 161–192, 1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pereira TM, Nogueira BV, Lima LC, Porto ML, Arruda JA, Vasquez EC, Meyrelles SS. Cardiac and vascular changes in elderly atherosclerotic mice: the influence of gender. Lipids Health Dis 9: 87, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Pinto E. Blood pressure and ageing. Postgrad Med J 83: 109–114, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pires PW, Dams Ramos CM, Matin N, Dorrance AM. The effects of hypertension on the cerebral circulation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H1598–H1614, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pires PW, Girgla SS, McClain JL, Kaminski NE, van Rooijen N, Dorrance AM. Improvement in middle cerebral artery structure and endothelial function in stroke-prone spontaneously hypertensive rats after macrophage depletion. Microcirculation 20: 650–661, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pires PW, Jackson WF, Dorrance AM. Regulation of myogenic tone and structure of parenchymal arterioles by hypertension and the mineralocorticoid receptor. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H127–H136, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Rigsby CS, Ergul A, Portik Dobos V, Pollock DM, Dorrance AM. Effects of spironolactone on cerebral vessel structure in rats with sustained hypertension. Am J Hypertens 24: 708–715, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rigsby CS, Pollock DM, Dorrance AM. Spironolactone improves structure and increases tone in the cerebral vasculature of male spontaneously hypertensive stroke-prone rats. Microvasc Res 73: 198–205, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Schneider CA, Rasband WS, Eliceiri KW. NIH Image to ImageJ: 25 years of image analysis. Nat Methods 9: 671–675, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shi Y, Savarese G, Perrone-Filardi P, Luscher TF, Camici GG. Enhanced age-dependent cerebrovascular dysfunction is mediated by adaptor protein p66Shc. Int J Cardiol 175: 446–450, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sierra C. Cerebral small vessel disease, cognitive impairment and vascular dementia. Panminerva Med 54: 179–188, 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sokolova IA, Manukhina EB, Blinkov SM, Koshelev VB, Pinelis VG, Rodionov IM. Rarefication of the arterioles and capillary network in the brain of rats with different forms of hypertension. Microvasc Res 30: 1–9, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Springo Z, Toth P, Tarantini S, Ashpole NM, Tucsek Z, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Koller A, Ungvari ZI. Aging impairs myogenic adaptation to pulsatile pressure in mouse cerebral arteries. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35: 527–530, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Toth P, Csiszar A, Tucsek Z, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Koller A, Schwartzman ML, Sonntag WE, Ungvari Z. Role of 20-HETE, TRPC channels, and BKCa in dysregulation of pressure-induced Ca2+ signaling and myogenic constriction of cerebral arteries in aged hypertensive mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305: H1698–H1708, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Toth P, Tucsek Z, Sosnowska D, Gautam T, Mitschelen M, Tarantini S, Deak F, Koller A, Sonntag WE, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Age-related autoregulatory dysfunction and cerebromicrovascular injury in mice with angiotensin II-induced hypertension. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 33: 1732–1742, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsamis A, Rachev A, Stergiopulos N. A constituent-based model of age-related changes in conduit arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1286–H1301, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.van Laar PJ, van der Graaf Y, Mali WP, van der Grond J, Hendrikse J, Group SS. Effect of cerebrovascular risk factors on regional cerebral blood flow. Radiology 246: 198–204, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vasan RS, Beiser A, Seshadri S, Larson MG, Kannel WB, D'Agostino RB, Levy D. Residual lifetime risk for developing hypertension in middle-aged women and men: The Framingham Heart Study. JAMA 287: 1003–1010, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Waldstein SR, Rice SC, Thayer JF, Najjar SS, Scuteri A, Zonderman AB. Pulse pressure and pulse wave velocity are related to cognitive decline in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Hypertension 51: 99–104, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang M, Lakatta EG. Altered regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 in aortic remodeling during aging. Hypertension 39: 865–873, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wang M, Monticone RE, Lakatta EG. Arterial aging: a journey into subclinical arterial disease. Curr Opin Nephrol Hypertens 19: 201–207, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ward MR, Pasterkamp G, Yeung AC, Borst C. Arterial remodeling. Mechanisms and clinical implications. Circulation 102: 1186–1191, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Westcott EB, Jackson WF. Heterogeneous function of ryanodine receptors, but not IP3 receptors, in hamster cremaster muscle feed arteries and arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H1616–H1630, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Xu H, Garver H, Galligan JJ, Fink GD. Large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel beta1-subunit knockout mice are not hypertensive. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H476–H485, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yu SY, Blumenthal HT. The calcification of elastic fibers. I. Biochemical studies. J Gerontol 18: 119–126, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yu SY, Blumenthal HT. The calcification of elastic fibers. II. Ultramicroscopic characteristics. J Gerontol 18: 127–134, 1963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]