Abstract

This review highlights the influence of oxygen (O2) availability on cerebral blood flow (CBF). Evidence for reductions in O2 content (CaO2) rather than arterial O2 tension (PaO2) as the chief regulator of cerebral vasodilation, with deoxyhemoglobin as the primary O2 sensor and upstream response effector, is discussed. We review in vitro and in vivo data to summarize the molecular mechanisms underpinning CBF responses during changes in CaO2. We surmise that 1) during hypoxemic hypoxia in healthy humans (e.g., conditions of acute and chronic exposure to normobaric and hypobaric hypoxia), elevations in CBF compensate for reductions in CaO2 and thus maintain cerebral O2 delivery; 2) evidence from studies implementing iso- and hypervolumic hemodilution, anemia, and polycythemia indicate that CaO2 has an independent influence on CBF; however, the increase in CBF does not fully compensate for the lower CaO2 during hemodilution, and delivery is reduced; and 3) the mechanisms underpinning CBF regulation during changes in O2 content are multifactorial, involving deoxyhemoglobin-mediated release of nitric oxide metabolites and ATP, deoxyhemoglobin nitrite reductase activity, and the downstream interplay of several vasoactive factors including adenosine and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. The emerging picture supports the role of deoxyhemoglobin (associated with changes in CaO2) as the primary biological regulator of CBF. The mechanisms for vasodilation therefore appear more robust during hypoxemic hypoxia than during changes in CaO2 via hemodilution. Clinical implications (e.g., disorders associated with anemia and polycythemia) and future study directions are considered.

Keywords: cerebral blood flow, cerebral oxygen delivery, hypoxia, nitric oxide, adenosine triphosphate

relative to other species, the human brain has evolved to be approximately three times larger than expected for body size due to increases in the frontal lobe, temporal lobe, and cerebellum (164). The increase in brain volume occurred during the early evolution of the genus Homo and was especially pronounced in Homo erectus due to selection pressures associated with greater social complexity, enhanced ecological demands on cognition, and increased physical activity (76, 154, 170). As a consequence, the brain has evolved into a highly oxidative organ accounting for a disproportionate 20% of the basal oxygen budget which is 10 times higher than what would be expected from its weight (153). The ability to process large amounts of O2 over a relatively small tissue mass is required to support the high rate of ATP production to maintain an electrically active state for the continual transmission of neuronal signals (reviewed in 7). However, this obligatory high rate of cerebral O2 consumption is associated with a commensurately high “vulnerability for failure.” In light of this vulnerability, adequate delivery of O2 to the brain via precise regulation of cerebral blood flow (CBF) is therefore vital to maintaining optimal function and avoid cellular damage and/or death. Describing the influence of oxygen (O2) availability on CBF and brain metabolism is an essential step toward a better understanding of brain energy homeostasis and associated clinical implications.

An appropriate and commonly employed model to investigate the acute and chronic cerebrovascular effects of reduced O2 availability involves exposure to normobaric hypoxia or ascent to high altitude (HA; over 3,000 m above sea level). It has been well documented that CBF increases in response to the severity of hypoxic stimuli in humans via cerebral vasodilation (2–5, 166, 199, 202). These compensatory increases in CBF upon exposure to normo- and hypobaric (sea level and HA, respectively) hypoxia are adequate to maintain cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2, reviewed in Ref. 5). The mechanisms underlying the influence of hypoxia upon CBF are complex and involve interactions of many physiological, metabolic, and biochemical processes. For example, potential mechanisms of cerebrovascular dilation likely change depending on the magnitude and duration of exposure to hypoxia, the degree of acid-base adjustment, intrinsic cerebral reactivity to changes in O2, CO2, and pH, as well as release of local vasoactive factors [e.g., nitric oxide (127) and adenosine (22, 135) to name but a few].

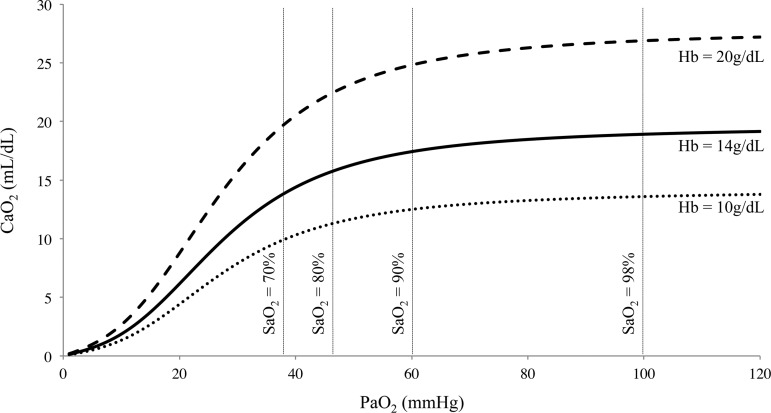

The partial pressure of arterial oxygen (PaO2) dissolved in the plasma contributes little to the total content of arterial oxygen (CaO2; Fig. 1); however, because the partial pressure gradient between arterial blood and tissue facilitates diffusion of O2 into the cell, PaO2 is often presumed to be the cerebral vascular stimulus during hypoxia. Yet, blood flow to contracting skeletal muscles is regulated by CaO2, not PaO2 (61), with deoxyhemoglobin (deoxyHb) being both the primary O2 sensor and upstream response effector; there are data in humans indicating the same might be true for CBF regulation. Moreover, in clinical and environmental (HA) conditions where CaO2 is elevated, there is evidence that CBF is reduced (84, 128).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the relationship between oxygen content (CaO2) and the partial pressure of oxygen in arterial blood (PaO2). Reduced hemoglobin (Hb) concentration during anemia or following hemodilution (bottom dotted curve) decreases CaO2. Increased hemoglobin as would occur in polycythemia (top dashed curve) increases CaO2. The middle solid line denotes normal resting values. Figure derived from Eq. 3: CaO2 (ml/dl) = [Hb]·1.36·(%SaO2/100) + 0.003·PaO2.

Herein, for both physiological and to a lesser extent pathophysiological settings, we review the current knowledge of CBF regulation with changes in PaO2 and/or CaO2. Emerging evidence suggests that deoxyhemoglobin is the primary biological regulator of CBF, and therefore consequently CDO2 and ultimately brain tissue oxygenation, during changes in CaO2 originating from alterations in O2 tension (i.e., hypoxemic hypoxia), hemodilution, and anemia. First, we provide an overview of how CBF is regulated under acute (seconds to hours), chronic (days to years), and lifetime conditions of hypoxemic hypoxia, and examine the evidence supporting the sufficient maintenance of CDO2. Second, we review the studies to date that have examined (directly or indirectly) the relationship between CaO2 and CBF in the absence of changes in PaO2 (hemodilution), and contrast the CBF response with those where PaO2 is reduced (hypoxemic hypoxia). Further, we consider the varying levels of deoxyhemoglobin produced between these different experimental paradigms. Finally, we provide an overview of the molecular underpinnings that regulate CBF during hypoxemia or during independent changes in CaO2.

RESPONSE CHARACTERISTICS OF CBF TO HYPOXEMIC HYPOXIA

It is well established that inhalation of hypoxic gas mixtures causes dilation of the pial vessels, a reduction in cerebral vascular resistance, and increases CBF in humans (29, 108). However, while hypoxia per se is a cerebral vasodilator, reflected in a rise in CBF in proportion to the severity of isocapnic hypoxia (reviewed in 5, 202), in normal conditions the hypoxia-induced activation of peripheral chemoreceptor activity leads to hyperventilatory-induced lowering of the partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) and subsequent cerebral vasoconstriction. Over time, metabolic compensation occurs in response to the respiratory alkalosis and CBF is normalized to the lowered PaCO2 (200). Although often viewed in isolation, the interaction between PaCO2 and PaO2 dramatically alters the CBF response, and varies with exposure time.

Acute hypoxemic hypoxia (seconds to hours).

The cerebral vasculature is responsive to hypoxia, but only below a PaO2 of ∼50 mmHg. This response is dependent on the prevailing PaCO2: hypercapnia increases and hypocapnia decreases the vasodilatory response to a hypoxic stimulus (121) due to the independent vasoactive effects of PaCO2/pH on CBF (202). For a given severity of isocapnic hypoxia, studies incorporating a range of techniques to quantify CBF report a 0.5–2.5% increase in CBF per percent reduction in arterial oxyhemoglobin saturation (SaO2; 29, 75, 95, 150, 151, 157, 169, 199). However, this response is not uniform across the brain. For example, for a given severity of isocapnic hypoxia, blood flow to the brain stem increases more than that to the middle and anterior regions, as assessed by flow through the vertebral and internal carotid arteries, respectively (75, 116, 139, 199). Data collected using congruous PET scan during isocapnic hypoxia also indicate that cortical blood flow is less responsive to hypoxia than phylogenetically older areas of the brain (18). Although the cerebral areas responsible for increased blood flow to hypoxia were traditionally thought to fall exclusively at the small pial vessels (207), recent data now indicate that cerebral vasodilation also occurs at the larger intracranial cerebral (e.g., MCA) (88, 201, 203) and extracranial cerebral vessels (e.g., internal carotid artery and vertebral artery) (116). This dilation has been observed when SaO2 falls to ∼80% for both the large intracranial (88) and extracranial (116) cerebral vessels.

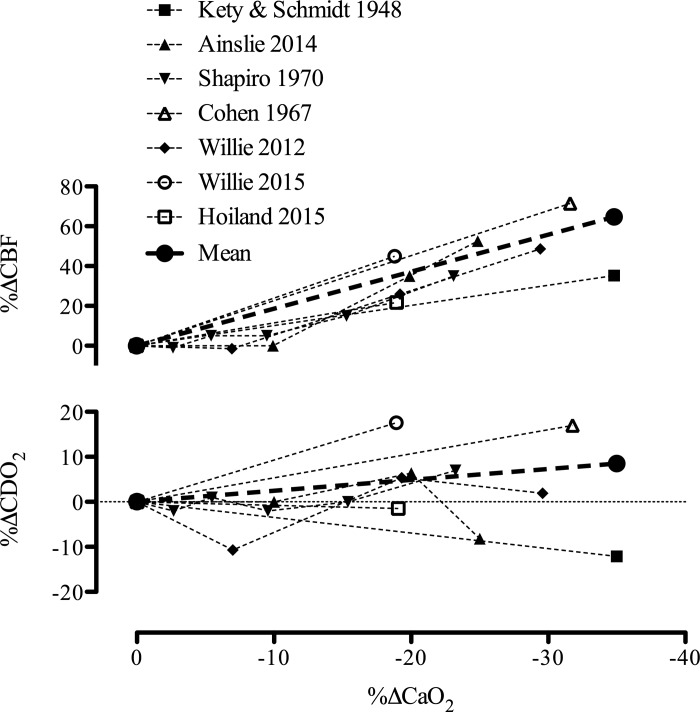

Although the underlying mechanisms have not been fully elucidated in awake humans (see signaling pathways in the regulation of cbf during hypoxia), upon reanalysis of the key studies to date (see Fig. 2), the elevation in CBF in response to acute hypoxemic hypoxia seems to be entirely appropriate to maintain CDO2. When CDO2 is maintained, both cerebral oxygen extraction (%) and CMRO2 are also unchanged (4). However, if CDO2 were to become reduced, then oxygen extraction has the capacity to almost double to compensate. The CDO2 and cerebral oxygen extraction fraction can be calculated as per Eqs. 1 and 2:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where CDO2 represents cerebral oxygen delivery, gCBF represents global cerebral blood flow, CaO2 represents the arterial content of oxygen, and CjvO2 represents the jugular venous content of oxygen.

Fig. 2.

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) and oxygen delivery (CDO2) during acute hypoxemic hypoxia in humans. Data taken from five studies during hypoxemic hypoxia with concurrent measures of CBF and arterial blood gases. As exceptions we used data from Refs. 75 and 169, where Eq. 3 was used to calculate CaO2 with SaO2 estimated using the Severinghaus equation (167). Data from 55 healthy subjects are depicted; i.e., n = seven (108), ten (4), six (169), nine (29), ten (199), nine (200), and four (75). The mean lines for both CBF and CDO2 have been calculated as the linear slope from the mean data of each study weighted for sample size. All studies were conducted under isocapnic conditions except for Ref. 108, where PaCO2 was reduced by 4 mmHg during the hypoxic exposure.

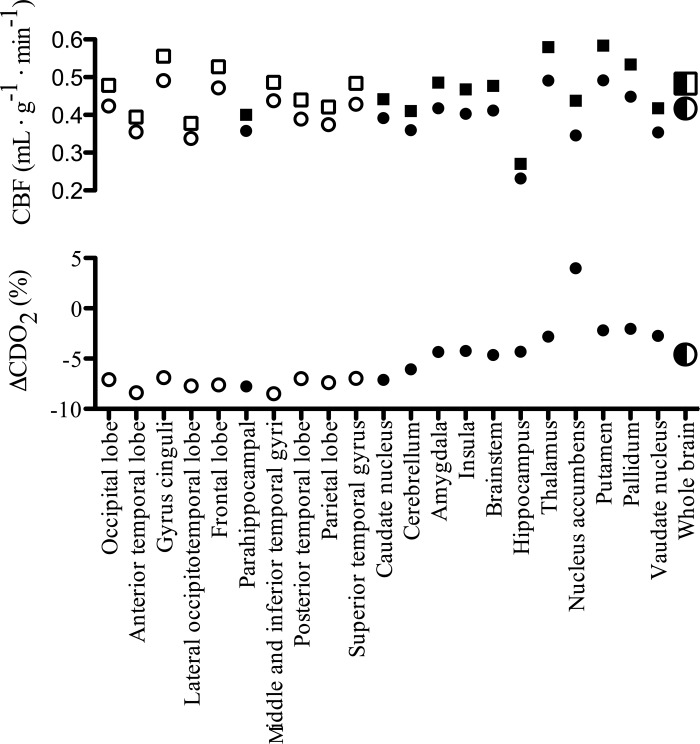

While global CDO2 is maintained during hypoxemic hypoxia, there appears to be a moderately heterogeneous response throughout the brain, related to regional disparities in CBF and hypoxic reactivity (Fig. 3) and an overall drop in tissue Po2 (as inferred from jugular venous Po2) (4). These disparities in the maintenance of CDO2, and thus specific regional variations in tissue Po2, in concert with selective vulnerability of specific regions (i.e., selective neuronal vulnerability) to hypoxia (149) are likely implicated in cerebral dysfunction (e.g., reduced cognitive capacity). Additionally, independent of CDO2, tissue Po2 levels can directly regulate neuronal ion channel function (98) and alter neurotransmitter production (e.g., glutamate, serotonin, acetylcholine) due to a low Km for oxygen (60, 65). Cerebral dysfunction in hypoxia has been reviewed in detail elsewhere (7, 60).

Fig. 3.

Regional disparities in cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) relative to the whole brain during isocapnic hypoxia. The top panel depicts regional cerebral blood flow during normoxia (circles) and hypoxia (FiO2* = 0.10; squares) in phylogenetically new (open symbols) and old (closed symbols) brain regions as measured by positron emission tomography. These values can be compared with their respective whole brain flow values (half-filled symbols). The lower panel highlights the heterogeneous changes in CDO2 relative to the whole brain (half-filled circle), and a trend for CDO2 of newer brain regions to be less impacted by hypoxia then phylogenetically older regions. CDO2 was calculated assuming a uniform [Hb] of 15 g/dl and O2 affinity of 1.36. Data adapted from Ref. 18.

Chronic hypoxemic hypoxia (days to years): evidence from studies at high altitude.

The influence of CaO2 on CBF is contingent on the balance between the degree and duration of hypoxia and ensuing hypocapnia. In turn, the extent to which the cerebrovasculature responds to HA is dependent upon four key integrated reflexes: 1) hypoxic cerebral vasodilation; 2) hypocapnic cerebral vasoconstriction; 3) the hypoxic ventilatory response; and 4) the hypercapnic ventilatory response (reviewed in detail elsewhere; 5). Indeed, because pH and CaO2 change throughout the acclimatization process to hypoxia (i.e., metabolic compensation for the respiratory alkalosis, which returns pH towards baseline, and progressive increases CaO2 from hemoconcentration), the CBF response to hypoxia will follow accordingly.

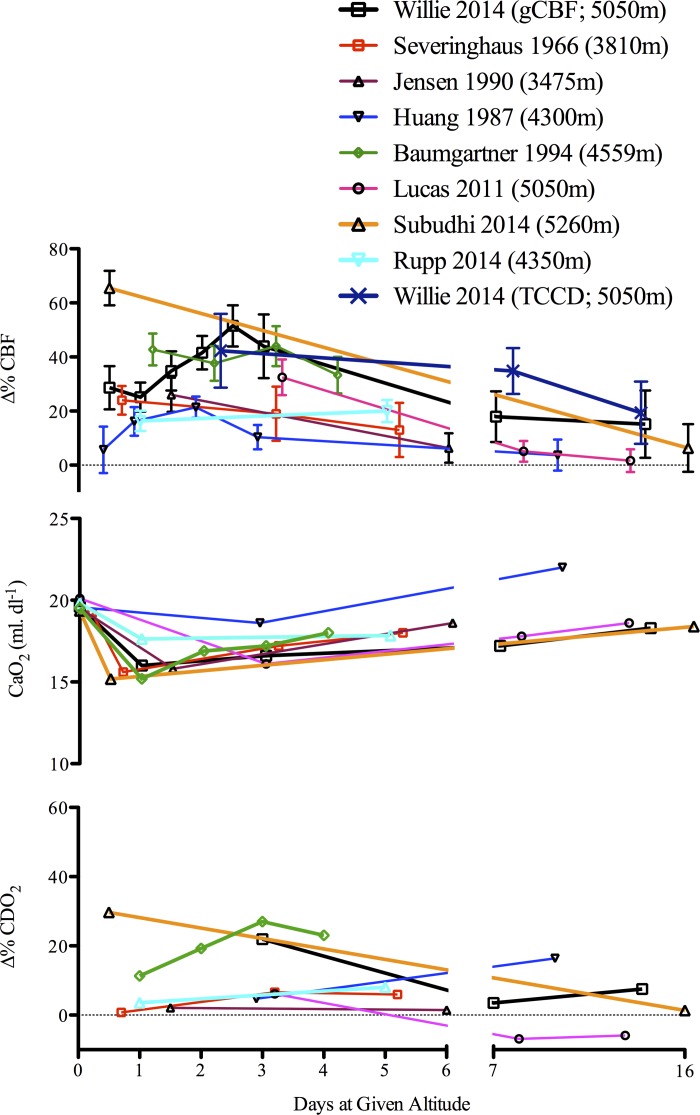

At least eight studies have measured CBF during acclimatization to HA (>3,400 m) using a variety of techniques (e.g., Kety Schmidt, 133Xe, vascular ultrasound, transcranial, and transcranial color-coded Doppler; for review of measurement techniques, see 171, 185) to identify consistent increases in CBF following exposure to HA; however, the degree of hypoxia and duration of time at altitude is inconsistent and variable (11, 79, 96, 119, 158, 166, 175, 201). What is noteworthy, as illustrated in Fig. 4, is that the ∼20–60% increase in CBF in each of the cited studies is closely matched to the reduction in CaO2 in a reciprocal manner; CDO2 is therefore well maintained across acclimatization.

Fig. 4.

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) and oxygen delivery (CDO2) at high altitude. Percent change in cerebral blood flow (Δ%CBF) during acclimation (>4 days above 3,400 m) in the eight studies at various altitudes reviewed in Ref. 5 (11, 79, 96, 119, 158, 166, 175, 201), and one recent investigation following 5 days at 4,350 m (158). As depicted, CDO2 is maintained at high-altitude due to the compensatory increase in CBF. As all studies were conducted during hypobaric hypoxia, PaCO2 was not controlled. TCCD, transcranial color-coded Doppler; gCBF, global cerebral blood flow. [Adapted from Ainslie and Subudhi (5) with permission. Copyright Mary Ann Liebert, Inc.]

Considering the importance of PaCO2 on the cerebrovascular response to normobaric (29, 139, 199) and hypobaric hypoxia (200), the elevated CBF during initial exposure to HA, at first glance, appears paradoxical and variable (166). However, it is well established that individual variability in hypoxic and hypercapnic ventilatory sensitivities influences the onset of ventilatory acclimatization (i.e., degree of increased PaO2 and decreased PaCO2) (37). A recent study demonstrated that the onset of ventilatory acclimatization combined with metabolic compensation of the respiratory alkalosis over time results in a normalization of the CBF response despite the prevailing hypocapnia due to metabolic compensation of the respiratory alkalosis (200).

Another important factor that has been largely ignored in the regulation of CBF at HA is changes in CaO2 and blood viscosity. As outlined in Fig. 4, CaO2 is progressively increased after approximately the first week at HA due to ventilatory acclimatization, hemoconcentration, and acid-base changes. Hematocrit (Hct) is increased by 10–15% over the first few weeks at altitude (119) and therefore, due to the consequent elevation in CaO2, also tends to lower CBF. Acute changes in blood viscosity may also affect endothelial functioning via changes in shear stress, and research has indeed shown that the cerebral vasculature exhibits a degree of autoregulation in response to both acute increases and decreases in plasma viscosity (131). The magnitude and direction of the change in viscosity may therefore affect the capacity of the blood vessel to respond to further changes in CaO2. Alternatively, in conditions where viscosity is chronically increased (e.g., chronic mountain sickness, sickle cell disease), endothelial functioning is often blunted as increases in shear stress are offset by secondary complications such as heightened sympathetics and systemic inflammation (8).

Chronic adaptation to high altitude.

Although hypoxia is a major physiological stress, several human populations have survived for millennia at HA, suggesting they have adapted to hypoxic conditions. Three successful patterns of human adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia have been documented (14): Andean (i.e., “classic adaptation,” erythrocytosis with arterial hypoxemia) (15); Tibetan (i.e., marginally elevated venous hemoglobin concentration with arterial hypoxemia) (14); and the recently identified Ethiopian—Amhara highlanders living at ∼3,500 m—pattern [i.e., normal venous hemoglobin concentration and arterial oxygen saturation within the normal range of sea level populations (14)]. Of note, the Amhara pattern of adaptation exhibits higher O2 saturation and less erythrocytosis than their Omotic Ethiopian counterparts (171).

Early studies have reported that native Andeans living at HA (∼4,200 m) have 20% lower CBF values compared with sea-level natives (reviewed in 5). The main mechanism underpinning the ∼20% lower CBF of high-altitude residents is the reported elevation in Hct and consequently increased CaO2. These conclusions are largely based on the inverse relationship between CaO2 and CBF that has been demonstrated with carbon monoxide exposure or hemodilution (122; see arterial oxygen content and cerebral blood flow: hypoxemic hypoxia vs. hemodilution). The lower CBF in high-altitude residents may also be attributed to the passive changes in blood viscosity associated with increased Hct (128) and active cerebral vasoconstriction (155, 156). For example, the cerebral arteriovenous oxygen content difference is approximately proportional to the Hct level in high-altitude natives (128). However, via theoretical corrections in CBF for the elevations in Hct, it is calculated that CBF is still ∼5% lower in high-altitude Andean natives (91). Whether the reduction in CBF in Andean high-altitude residents is a function of increased blood viscosity, increased arterial-venous oxygen content difference, or augmented oxidative-nitrosative stress (8), has yet to be resolved. Nevertheless, it appears, at least at sea level, that blood viscosity does not affect CBF and that the observed reductions are simply due to the corresponding elevation in CaO2 (see arterial oxygen content and cerebral blood flow: hypoxemic hypoxia vs. hemodilution). Therefore, increased CaO2 is likely the primary factor governing the reduction in CBF noted in high-altitude natives.

Although CBF in Tibetan high-altitude residents at ∼4,200 m seems 5–10% lower than lowlanders, these data are limited and based on blood velocity indices of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) (92–94). Jansen and Basnyat (91) contended that velocities in the internal carotid artery and MCA were 11.7% and 3.4% (mean 6.2%) higher, respectively, compared with lowlanders, yet still within the range of expected variation at sea level reported by others (162, 163). Also, Hct and CaO2 in Tibetan (Sherpa) high-altitude residents (206) are slightly increased compared with sea-level (by roughly 10%) but comparable to well-acclimatized lowlanders (52, 56, 119, 152). Despite the need for experimental evidence, an increased nitric oxide availability in Himalayans has been speculated to explain differences in CBF between Tibetan and Andean populations (13, 44). Likewise, although the cerebral circulation of Ethiopian HA dwellers seems to be insensitive to hypoxia and may represent a positive adaptation (unlike Andean HA dwellers), this is also solely based on MCA velocity (28). Since the MCA has been demonstrated to dilate in hypoxia (88, 201, 203), past indices of CBF at altitude based on MCA velocity need to be interpreted with caution.

ARTERIAL OXYGEN CONTENT AND CEREBRAL BLOOD FLOW: HYPOXEMIC HYPOXIA VS. HEMODILUTION

The magnitude of the CBF response is proportional to the severity of hypoxic stimuli and is appropriate to maintain CDO2 and hence offset the hypoxemic hypoxia-induced reductions in CaO2 (2–5, 166, 199, 202). However, an important prevailing question in human cerebrovascular physiology is whether the primary regulator of CBF is the total amount of O2 (i.e., CaO2) or the O2 dissolved in plasma (i.e., PaO2). The amount of oxygen bound to hemoglobin and PaO2 determine CaO2, as per Eq. 3:

| (3) |

where [Hb] is the arterial hemoglobin concentration, 1.36 is the affinity for O2 to hemoglobin, and 0.003 is the solubility of O2 dissolved in blood.

Although PaO2 (dissolved O2) only minimally contributes to the total CaO2 when breathing room air, because it facilitates diffusion of oxygen into the cell, PaO2 is often presumed to be the cerebral vascular stimulus. Yet, as previously discussed, CBF does not decrease until a PaO2 of ∼50 mmHg, the point whereby the reduction in CaO2 (and SaO2) accelerates with further decreases in PaO2 (Fig. 1). Reductions in CaO2 with maintained PaO2 resulting from either carbon monoxide exposure (142), acute or chronic anemia (24, 67), and hemodilution (142), all increase CBF. Moreover, CBF varies inversely with Hct in many species in both acute (e.g., acute anemia) and chronic experimental conditions (e.g., erythropoiesis/polycythemia). While all three of these experimental paradigms (anemia, hemodilution, and carbon monoxide exposure) highlight the coupling of CBF to CaO2, it is important to consider their biological differences. For example, carbon monoxide is a cerebral vasodilator independent of inhibiting the formation of oxyhemoglobin (113), and elicits a greater increase in CBF for a given reduction in CaO2 than hemodilution (142). Therefore, comparing the differences in vasodilation mediated by hypoxemic hypoxia (i.e., ↓PaO2) and isovolumic hemodilution (simulated acute anemic hypoxia) represents a more robust model than using carbon monoxide. As the underlying mechanism(s) remain largely theoretical, it has been speculated that 1) the hemorheologic consequences of reductions in blood viscosity (which is derived from plasma viscosity, Hct, and mechanical properties of red blood cells) mediate the increases in CBF noted during hemodilution (e.g., 177, 178); and 2) reductions in CaO2 elicit vasodilatory responses to maintain CDO2 (e.g., 24, 26). The following sections highlight the relationship between CaO2 and CBF in the presence and absence of changes in PaO2. The potential governing mechanisms are discussed.

The majority of animal studies have indicated that viscosity is an important regulator of CBF during hemodilution (80, 109, 183); however, this is not a universal finding (195). Moreover, studies in humans provide evidence against an appreciable role of viscosity. Indeed, despite the initial few human studies supporting that viscosity is a primary regulator of CBF during changes in Hct (64, 83, 84, 178), the potential implications of changes in CaO2, and its consequent effects on CDO2 were ignored. To partition the influence of blood viscosity independently of Hct and CaO2 Humphrey et al. (82) investigated the difference in CBF between paraproteinemic (patients with high plasma protein concentration and elevated plasma viscosity) and nonparaproteinemic patients (82). However, both Hct and PaCO2 differed between groups. If the average CBF difference between paraproteinemic and nonparaproteinemic groups are corrected for the differences in Hct (assumed to be indicative of differences in CaO2), and PaCO2 [using the linear slope presented in Fig. 5 and the known ∼7% increase in volumetric CBF per mmHg change in PaCO2 above eupneic levels (108, 199), respectively], the observed difference in CBF is abolished. The limitations of this study were addressed in a later study by Brown and Marshall (26); here, changes in viscosity failed to alter CBF when CaO2 and PaCO2 remained constant. In turn, the authors suggested that independently viscosity is an insignificant factor in CBF regulation after accounting for changes in CaO2 (24). This finding has been replicated in other clinical populations possessing intact cerebrovascular function and normal Hct during isovolumic conditions (25) as well as during hemodilution-mediated hypoxia in animals using high- and low-viscosity replacement fluids (195). Therefore, it seems the impact of viscosity may be negligible in the hypoxic brain at rest, and relative to hypoxic CBF reactivity where the vascular bed becomes vasodilated. Nevertheless, theoretically, Poiseuille's law demonstrates that changes in viscosity will have pronounced effects on flow, as per Eq. 4:

| (4) |

where P represents perfusion pressure, r represents vessel radius, η represents blood viscosity, and l represents vessel length.

Fig. 5.

Cerebral blood flow (CBF) and oxygen delivery (CDO2) during hemodilution in humans. Data taken from five studies utilizing hemodilution and concurrent measures of CBF and arterial blood gases. The subject samples include 20 anesthetized tumor resection patients prior to surgery (filled circle) (33), eight patients with vasospasm following aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage (filled square) (47), eight young healthy volunteers (upwards triangle) (73), five patients with unilateral internal carotid artery occlusion in addition to previous stroke or transient ischemic attacks (downwards triangle) (211), and 11 healthy young volunteers (filled diamond) (130), totaling 47 subjects [as all of the data collected in clinical patients, except for that of Ref. 211 (circled data point), followed the same trend as the studies using healthy patients, the data from Ref. 211 have been excluded from our representation of mean data]. Indeed, the unilateral internal carotid artery occlusion would have influenced CBF regulation and in turn likely explains the larger increase in CBF (on the patent side). The mean lines for both the CBF and CDO2 graphs have been calculated as the linear slope from the mean data of each study weighted for sample size.

Therefore, according to Poiseuille's law, viscosity is directly and inversely related to flow. The disparity between physiological conditions (turbulent flow and non-Newtonian fluid) and those that define Poiseuille's law likely explains the negative findings regarding an effect of viscosity on CBF during hemodilution, and hypoxia in humans (24). Moreover, if viscosity was the primary factor regulating CBF during hemodilution, one might expect that blood flow to all organs would increase to the same magnitude. The greater blood flow increase to the cerebral circulation relative to other organs indicates a selective active regulation (21). Collectively, analysis of 20 studies shows that CaO2 is inversely related to CBF (Fig. 6).

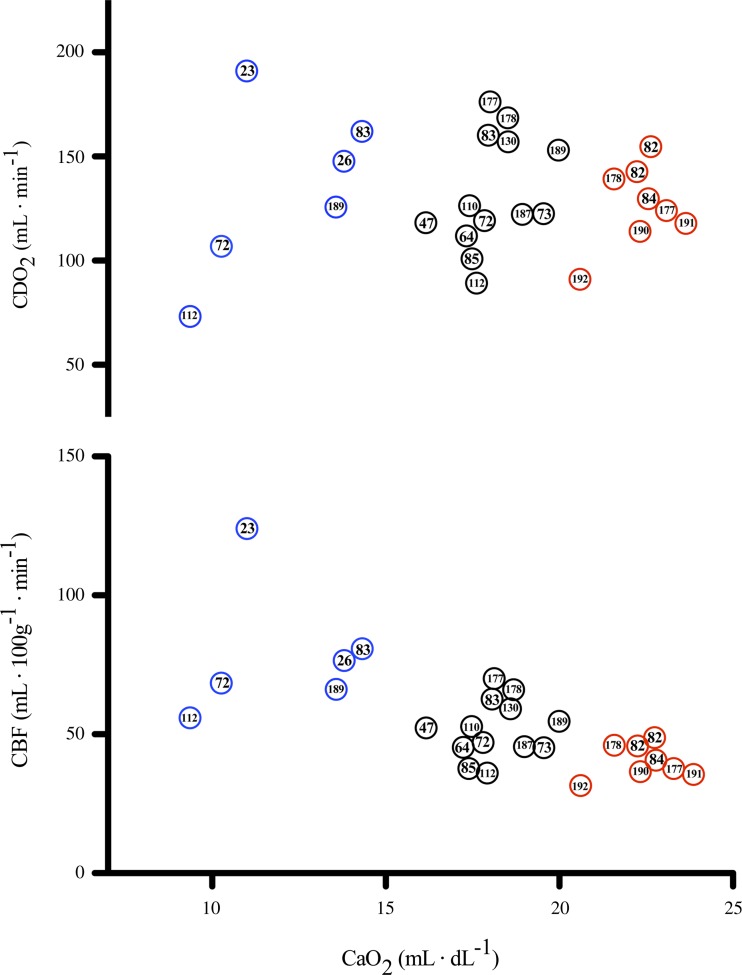

Fig. 6.

The relationship between CaO2, CBF, and CDO2 in anemic, hematologically normal, and polycthemic humans. Data were collated from 20 separate studies to highlight the relationship between CaO2 and CBF. Top: across studies there appears to be a relatively linear inverse relationship between CaO2 and CBF, with higher CaO2 concomitant to a reduced CBF, and lower CaO2 concomitant to increased CBF. Bottom: despite reductions in CaO2, the CBF increase is adequate to maintain CDO2. Across the presented studies there appears to be variability in CDO2 at any given CaO2; however, there is no distinct relationship between changes in CaO2 and CDO2. Thus it seems that CDO2 is preserved in anemic hypoxia and maintains a normal level during polycythemia due to a reduced CBF. Data are referenced by study number and collated from (23, 26, 47, 64, 72, 73, 82–85, 110, 112, 130, 177, 178, 187, 189–192).

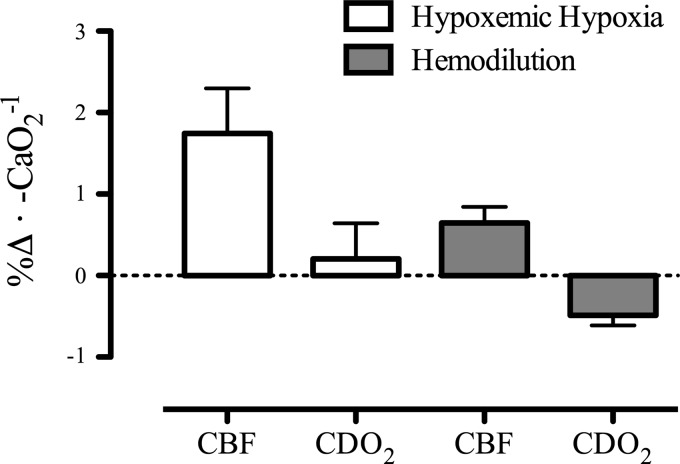

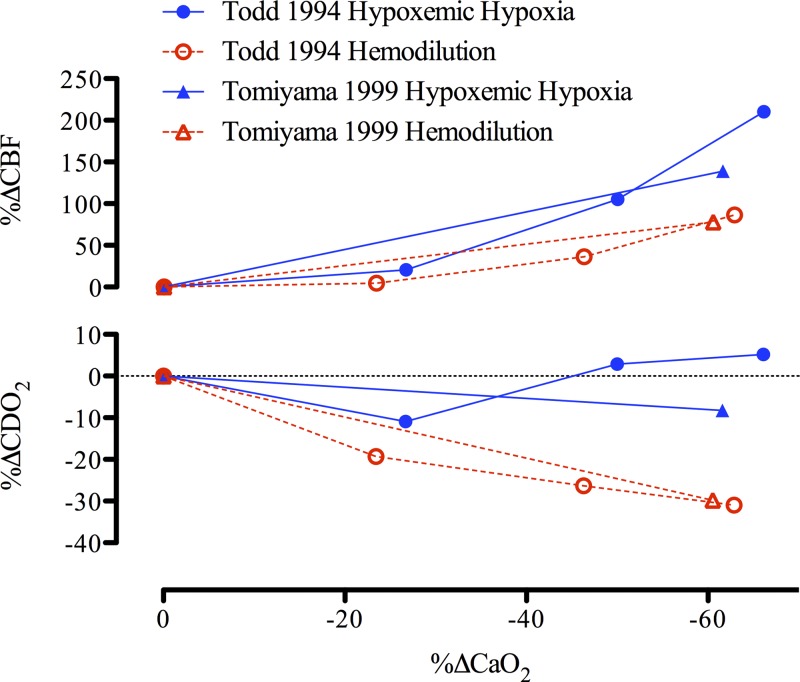

The CBF response during hemodilution and hypoxemic hypoxia is tightly coupled to reductions in CaO2 [e.g., for isovolumic hemodilution (33, 47, 73, 130, 211) and for hypoxemic hypoxia (4, 29, 108, 199); see Figs. 2 and 5]. Thus, in both otherwise healthy individuals and those with pathology (e.g., polycythemia, paraproteinemia), with normal (26) or high Hct (84), isovolumic hemodilution leads to an increase in CBF. Of note, the slope increase in CBF during isovolumic hemodilution is markedly (3-fold) reduced compared with during hypoxemic hypoxia (Fig. 7). The mean slope increase in CBF during isovolumic hemodilution is 0.66% CBF/−%CaO2, whereas the mean slope increase in CBF during hypoxemic hypoxia is 1.85% CBF/−%CaO2 (see Figs. 2 and 5 legends for explanation of calculations). The blunted cerebrovascular response to hemodilution compared with hypoxemic hypoxia results in a lowered CDO2 (Fig. 7). When assessing the long-term influence of CaO2 from altered hemoglobin mass in anemia and polycythemia, it is apparent that CDO2 is not impaired (Fig. 6). Indeed, patients with anemia possess a relatively high CBF that maintains CDO2 despite reduced CaO2, and the reduction in CBF that is typical of polycythemic patients is not large enough to reduce CDO2, which appears to remain normal in these patients.

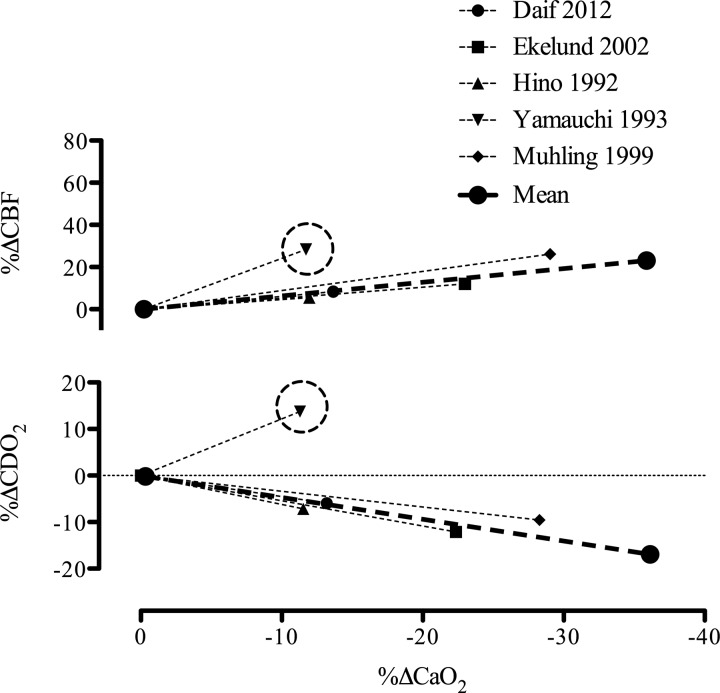

Fig. 7.

Change in cerebral blood flow (CBF) and oxygen delivery (CDO2) during reductions in arterial oxygen content (CaO2) induced by hypoxemic hypoxia and hemodilution. The mean slope increase in CBF is 0.66%CBF/−%CaO2 during hemodilution and 1.85%CBF/−%CaO2 during hypoxemic hypoxia. During hypoxemic hypoxia CDO2 is maintained with a 0.24%CDO2/−%CaO2 slope response, whereas during hemodilution, CDO2 is compromised with a −0.47%CDO2/−%CaO2 slope decrease with reduced CaO2. Error bars represent SD of the mean slopes from each study used in Figs. 2 and 5.

In the study by Daif et al. (33), where jugular venous samples were collected, an approximate 10% reduction in CMRO2 during hemodilution was estimated (33). This is in contrast to the multiple studies assessing CMRO2 during hypoxemic hypoxia, where a ≤35% reduction in CaO2 does not result in an altered CMRO2 (4, 29, 108). Whether the reduction in estimated CMRO2 calculated by Daif et al. (33) is due to the impaired CDO2 following hemodilution, or simply confounded by the concurrent anesthesia, is unknown (140). The remainder of human (73, 142) and animal (181) data indicate that CMRO2 remains unchanged during hemodilution despite a CaO2 reduction of ≤30%, due to a compensatory increase in cerebral O2 extraction (73, 181).

While within-subject manipulation of CaO2 through various methods (e.g., hemodilution vs. hypoxemic hypoxia) to assess cerebral vascular regulation to hypoxia has yet to be done in healthy human subjects, we speculate that the supposed differential response between hemodilution and hypoxemic hypoxia (that is, greater CBF increase with hypoxemic hypoxia compared with hemodilution) is due to the fundamental mechanisms governing hypoxic cerebral vasodilation. The mechanisms governing cerebrovascular vasodilation to hypoxia are now discussed, with speculation as to how they contribute to the response characteristics of hemodilution and hypoxemic hypoxia-mediated increases in CBF.

SIGNALING PATHWAYS IN THE REGULATION OF CBF DURING HYPOXIA

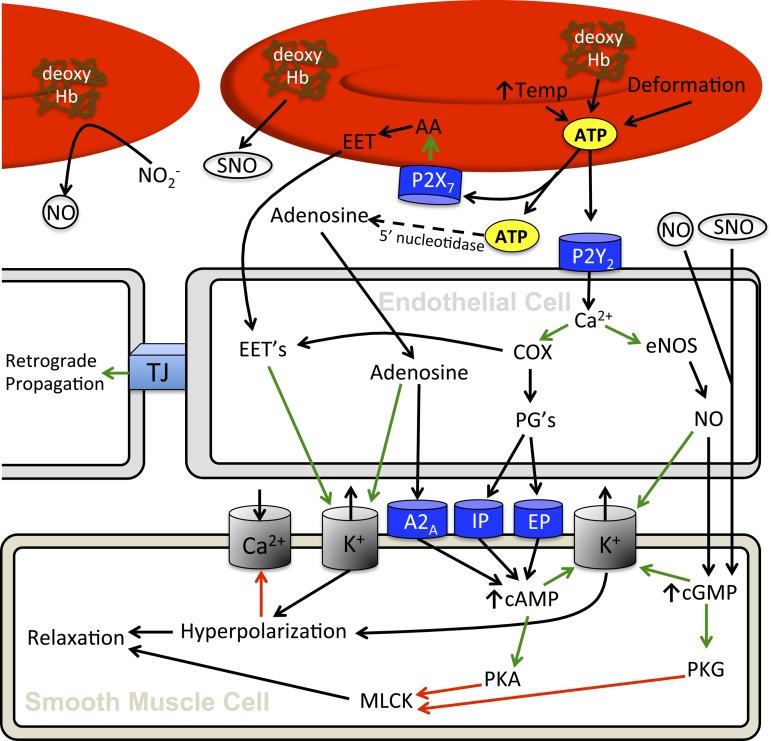

Although the cerebrovascular responses to acute and chronic hypoxia during both normobaria and hypobaria have been well characterized in humans, there remains a paucity of data related to the cellular mechanisms that govern it. Ultimately, it seems that hemoglobin in the erythrocyte functions as the primary O2 sensor and upstream response effector governing the regulation of vascular tone in hypoxia. Three principal mechanisms have been proposed for erythrocyte-dependent hypoxic vasodilation and include: 1) ATP release and subsequent activation of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS); 2) nitrite reduction to NO by deoxyhemoglobin, and 3) S-nitrosohemoglobin (SNOHb)-mediated bioactivity. Ultimately, it seems that hypoxic vasodilation hinges upon deoxyhemoglobin-mediated release of nitric oxide (i.e., S-nitrosothiols) and ATP, as well as NO reductase activity, which are all dependent on transition of hemoglobin from the relaxed (R) state to tense (T) state. These processes have direct vasomotor effects and influence release and/or formation of specific signaling molecules that are integral to the vasodilatory response. Candidate mechanisms (see Fig. 8) responsible for vasodilation downstream of deoxyhemoglobin include nitric oxide, adenosine, prostaglandins, and expoxyeicosatrienoic acids.

Fig. 8.

Putative pathways regulating cerebral blood flow during hypoxia. Increased temperature, erythrocyte deformation, and the conformational change concomitant to transition of oxy- to deoxyhemoglobin all signal erythrocyte mediated release of ATP (16, 49, 104, 173). Released ATP can then bind to the erythrocyte P2X7 receptor in an autocrine fashion to induce erythrocyte mediated EET release (101), which will increase vascular smooth muscle cell K+ channel conductance (59). The released ATP also binds endothelial P2Y2 receptors to initiate a signal cascade involving NO and potentially PGs (212). Moreover, ATP will break down into AMP and subsequently adenosine (58) that will also exert a vasodilatory effect on vascular smooth muscle through binding adenosine A2A receptors (71, 103), increasing cAMP levels (136, 161) and also through increasing inward rectify potassium channel conductance (71). Prostaglandins, if implicated, bind IP and EP receptors (35) which increases intracellular cAMP (133). NO, derived from the endothelium, through the nitrite reductase activity of erythrocytes (30), and S-nitrosohemoglobin (117, 174) will lead to increased guanylate cyclase activity and cGMP (145) as well as directly increase K+ channel conductance (20). Cyclic nucleotides will upregulate cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) and cGMP-dependent protein kinase (PKG) activity, which act to inhibit myosin light chain kinase (MLCK; 1), and therefore, reduce smooth muscle tone (107). Cyclic nucleotides will also increase potassium channel conductance (172), with increased potassium efflux hyperpolarizing cells and reducing activity of voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (134). Overall, ATP leads to vasodilation that can be conducted through gap junctions (41, 102). Green arrows represent activation of a downstream factor, and red arrows represent inhibition of downstream factors.

The site of hemoglobin deoxygenation (R → T allosteric shift) is not exclusive to the capillaries as over 66% of blood oxygen can be removed in the upstream cerebral arterial circulation prior to reaching the capillaries (46, 185). This highlights that erythrocyte release of ATP, SNO, and nitrite reductase activity can mediate dilation throughout the cerebral arterial tree. Moreover, these signals can be propagated (40, 41, 49, 102), and therefore, likely impact further upstream resistance vessels that only see oxygenated blood. Indeed, hypoxia has been shown to dilate the MCA (88, 201, 203), internal carotid artery (116), and vertebral artery (116) in humans.

Deoxyhemoglobin-Mediated Signal Transduction Pathways

S-nitrosohemoglobin release from erythrocytes during hypoxia.

Transport to and release of NO in the microvasculature are achieved in part through S-nitrosylation of hemoglobin. Formation of S-nitrosohemoglobin (SNO-Hb) in the lung occurs due to covalent bonding of NO or S-nitrosothiol (SNO) with the β-chain of β93 cysteine (Cys β93) of the Hb molecule (97). S-nitrosylation of Hb to form S-nitrosohemoglobin occurs most effectively in the R-state (i.e., in the lungs; Ref. 84) and allows for transport of vasoactive NO to the cerebral vasculature, where SNO is released upon deoxygenation of hemoglobin and transition to the T-state (174). When released, S-nitrosothiol provides the chemical stability required for NO to reach the endothelium as free NO would be scavenged too quickly to elicit vasodilation (186). The presence of a negative arterial to jugular venous SNO gradient indicates its transport and release in the rat brain (97). Moreover, it seems that the oxygenation state of cerebral tissue Po2 affects the vasodilatory influence of SNO (174), and regulates its role across physiological oxygen gradients.

Nitrite reduction via hemoglobin.

Nitrite (NO2−) acts as a storage pool for NO. There is accumulating evidence that its reduction by hemoglobin during hypoxia is an integral component of NO-mediated vasodilation (30, 43). The time course for NO2− reduction by hemoglobin is on the order of seconds to minutes (43), and thus likely contributes primarily to steady-state CBF vs. that of the initial upslope upon hypoxic exposure. In humans, after 9 h of passive exposure to normobaric hypoxia, the arterial delivery of NO2− to the brain was reduced indicating that it was either reduced by deoxyhemoglobin to increase circulating NO, reapportioned towards erythrocyte-bound species that also display bioactivity (NO2−, Hb-SNO, or HbNO), and/or in part scavenged by oxidizing free radical species (9). Of note, circulating nitrite anions may also participate in direct vasodilation (36). However, the specific role of direct cerebral vasodilation from circulating nitrite in hypoxia remains undetermined.

ATP liberation from erythrocytes during hypoxia.

Hypoxia induces ATP release from the erythrocyte (16, 48, 49). In isolated single cerebral arterioles, reduction of tissue Po2 in the presence of erythrocytes results in both vessel dilation and marked increases in effluent [ATP]; however, hypoxia without the presence of erythrocytes possesses no dilatory effect, while effluent [ATP] remains unchanged (39). The importance of deoxyhemoglobin in this response is further highlighted in that the presence of oxyhemoglobin in isolated rat penetrating arterioles significantly inhibits both dilation to low-dose [ATP] in a tissue bath, and the propagated dilation to intraluminally applied ATP (102). Moreover, hypoxia induced via carbon monoxide inhalation, which precludes the conformational change associated with offloading O2, does not change ATP levels (90). Yet, data assessing cerebral efflux of ATP during hypoxia are scarce, and collectively difficult to interpret. Concurrent to arterial hypoxemia there are several physiological factors that may affect erythrocyte release of ATP: 1) temperature, both in vitro and in vivo (104); and 2) shear stress and erythrocyte deformation (173, 194). How each of these components regulates erythrocyte-mediated ATP release and may be linked to the regulation of CBF during hypoxia is discussed below.

temperature and atp release. The liberation of ATP from deoxyhemoglobin is positively related to temperature (104). However, acute hypoxia alone at rest does not independently change core temperature; therefore the role of temperature on the CBF response to hypoxia alone is likely negligible. Nevertheless, any increase in CBF will increase the local cerebral heat loss (10, 70, 137). Theoretically, assuming a constant cerebral metabolic rate and arterial temperature, a 50% increase in CBF (e.g., with hypoxia) would increase heat removal from the brain by 50%. An extra 0.33 J·g−1·min−1 (209) of heat dissipated would result in a cerebral temperature reduction of ∼0.09°C/min (assuming a tissue specific heat capacity of 3.6 J·g−1·°C−1). However, a notable reduction in cerebral temperature would result in a reduction of the cerebral metabolic rate (10), and current evidence indicates that the cerebral metabolic rate of oxygen during isocapnic hypoxemic hypoxia is not reduced (4). In turn, it is unlikely that the liberation of ATP from deoxyhemoglobin is altered by potential changes in cerebral temperature with hypoxia.

shear stress and atp release. Shear stress and deformation of red blood cells facilitate the release of ATP from erythrocytes in vitro (173, 194). Increased blood velocity during hypoxia will lead to increased shear and thus lead to increased ATP release from erythrocytes. Shear is therefore likely an important factor mediating ATP release from red blood cells during hypoxia.

Downstream Signaling Molecules

ATP.

ATP is a potent cerebral vasodilator. Intraluminal ATP dilates the MCA of rats in vitro (32, 78, 212, 213), while in vivo intracarotid infusion of ATP increases pial vessel diameter in cats and global CBF in baboons (55). This ATP-mediated dilation is endothelium dependent (212, 213) through binding of P2Y2 purinoceptors (40, 123), is capable of retrograde propagation (41, 102), and acts through initiating downstream signal cascades. The candidate downstream signals responsible for ATP-mediated changes in vascular tone include NO (212), adenosine (58), EETs (40, 101), and prostaglandins (114, 124). Collectively, these vasoactive factors increase K+ channel conductance (77, 87), hyperpolarize the vascular smooth muscle (40, 102, 213), and/or decrease smooth muscle cell calcium sensitivity (1, 107). Evidence for an important role of these factors downstream of ATP binding to endothelial P2Y2 receptors, which we propose as the initial step mediating the CBF response to hypoxia (see ATP liberation from erythrocytes during hypoxia) is discussed, with particular focus on data in humans.

Adenosine.

Extravascular adenosine application leads to in vitro dilation of animal (41) and human (180) cerebral vessels and in vivo (17, 129, 193) dilation of animal cerebral vessels. This dilatory response is capable of retrograde propagation (102) and is mediated in part through increases in NO, inward rectifying potassium channel conductance (71), and increased cAMP levels (136, 161).

Hypoxia leads to an increase in the endogenous cerebral production of adenosine (17, 147, 204, 205). Production of adenosine in cerebral tissue is vital as negligible amounts of adenosine are thought to cross the blood-brain barrier and thus intravascular adenosine likely plays a limited role in CBF regulation during hypoxia (17). Administration of adenosine receptor antagonists (e.g., theophylline) abolishes the CBF increase to moderate hypoxia (i.e., PaO2 = 40–50 mmHg), and all but one study in animals—albeit CBF was still moderately reduced (148)—indicate a reduced CBF increase to severe hypoxia (i.e., PaO2 = 20–30 mmHg) by ∼50% (50, 74, 129). This effect of attenuating CBF during hypoxia by adenosine receptor antagonism is reflected in reductions of pial arteriolar dilation to hypoxia subsequent to administration of adenosine deaminase (6) and theophylline (6, 146). However, this latter finding is not universal (66) and may depend on the severity of hypoxia. Adenosine A2A receptor knockout mice possess a markedly attenuated CBF response to acute hypoxia (126), while A2B receptor antagonism has no effect on CBF, highlighting the predominant role of A2A receptors in mediating hypoxic vasodilation by adenosine (118). Adenosine-mediated regulation of CBF in humans is also likely mediated by A2 receptors (103); however, a distinction between A2A and A2B receptors in mediating this response is still vague.

In keeping with animal data, aminophylline—an adenosine receptor antagonist—reduces CBF both at rest (62, 120, 196) and during hypoxia in humans; however, the slope of the CBF response to hypoxia does not seem to differ pre- and post-aminophylline infusion (22, 135). This would suggest there is no effect of adenosine on the cerebrovascular response to hypoxia in humans, yet the methodological limitations of the xenon-133 technique (138) used by Bowton et al. (22) and indirect quantification of CBF by Nishimura et al. (135) precludes a definitive conclusion. In summary, it remains possible, yet unconfirmed in humans, that adenosine contributes to the hypoxic cerebrovascular response.

Nitric oxide.

The potent vasodilatory and cardiovascular properties of nitric oxide are well documented (19), and likely extend into hypoxic CBF regulation. Nitric oxide induces vasodilation through increases in cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) (145) and directly mediated increases in K+ channel conductance (20). Notionally, hypoxia increases neuronal nitric oxide synthase activity (12, 81, 160), releases NO from NO2− (30) and SNO-Hb (117) (discussed in previous sections), and leads to endothelial NO release downstream of ATP signaling (212). In turn, NO is consistently involved with in vivo and in vitro animal cerebral hypoxic vasodilation (111, 143, 146, 176). In awake humans, intravenous infusion of NG-monomethyl-l-arginine (l-NMMA), a NOS inhibitor, reduces the hypoxic CBF response, as assessed via MRI (127). In contrast, Ide et al. (86) reported that NOS inhibition with l-NMMA does not influence the CBF response to acute hypoxia, as assessed by MCA velocity measures. The latter finding, however, is confounded by recent MRI and ultrasound evidence demonstrating that the MCA dilates in normobaric hypoxia (88, 203). As previously highlighted in Eq. 4, even the slightest changes in MCA diameter will have a profound effect on flow, due to their exponential relationship. Increases in shear stress via increased velocity through cerebral vessels during hypoxia likely provide an additional stimulus to upregulate endothelial NOS (42) and modulate NO signaling. Experiments implementing pharmacological blockade of NOS (e.g., via l-NMMA) do not however provide indication of the vasoactive influence of NO from Hb-SNO and NO2− reduction and require parsimonious interpretation. While both animal and human data provide evidence for NO as an important regulator of the hypoxic CBF response, they relate only to NO derived locally from NOS and likely underestimate the true contribution of NO to hypoxic cerebral vasodilation.

Prostaglandins.

Indomethacin (INDO), a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug that nonselectively and reversibly inhibits cyclooxygenase activity, and consequent prostaglandin synthesis, has no effect on the CBF response to severe hypoxia (PaO2 = 25 mmHg) in vivo in rats (159) and newborn pigs (31, 114), despite abolishing hypoxic dilation in vitro (57). Further evidence highlights that prostaglandins are not one of the endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors released downstream of ATP binding P2Y2 receptors (40, 77). However, hypoxia increases cerebral 6-keto-PGF1α (a stable prostacyclin metabolite), which is indicative of increased prostaglandin production (114, 124).

In humans, one study (75), but not all (53, 69), reports that INDO reduces MCA velocity reactivity to hypoxia. However, volumetric flow reactivity of the internal carotid artery during hypoxia is unaffected (75). In contrast, hypoxic reactivity seems to be reduced in the posterior circulation, assessed by vertebral artery blood flow, following cyclooxygenase inhibition with INDO (75). While these data indicate that cyclooxygenase may be selectively mediating hypoxic dilation in the posterior cerebral circulation, they are not conclusive. For example, INDO selectively reduces cerebral reactivity to hypercapnia (elevated arterial CO2) whereas other cyclooxygenase inhibitors such as aspirin and naproxen have no effect (51, 122). These findings suggest INDO may influence CBF responses via a prostaglandin-independent mechanism. Indeed, INDO inhibits cAMP-dependent protein kinase activity (63, 105), which will directly impact smooth muscle tone (1, 107). More work is required to establish a role (if any) of prostaglandins in the cerebral hypoxic vasodilatory response in humans.

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids.

Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids dilate cerebral blood vessels (59) and are released from erythrocytes both spontaneously (100) and by ATP binding of P2X7 receptors (101). Notably, this ATP binding also inhibits erythrocyte release of the vasoconstrictor 20-hydroxyeicosatrienoic acid (99, 101). During hypoxia, both inhibition of EET synthesis and EET antagonism markedly reduces the CBF response to hypoxia in rats (118) and newborn pigs (115). While epoxyeicosatrienoic acids may represent an endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factor that is a relevant regulator of CBF during hypoxia, this has not been verified in humans.

Cellular Regulation of Vascular Smooth Muscle Tone

Fundamentally, there are two primary ways in which smooth muscle tone is regulated: 1) through changes in intracellular calcium concentration, and 2) through changes in vascular smooth muscle cell calcium sensitivity. Calcium entry into cells is governed largely by voltage-gated calcium channels. Hyperpolarization of the vascular smooth muscle cells by potassium efflux will downregulate calcium channel activity, making potassium channel conductance an important factor in the regulation of smooth muscle tone (134). Calcium sensitivity is dependent upon the phosphorylation (activation) of myosin, by myosin light chain kinase, which itself is dependent on cyclic nucleotide activity (cAMP and cGMP; 1).

Potassium channels.

Increased conductance of potassium channels hyperpolarizes cells, decreases membrane potential and ultimately inhibits activity of voltage-gated calcium channels (54, 134). Several vasoactive factors affect potassium channel conductance during hypoxia. Adenosine, through binding of smooth muscle A2A receptors, and vasodilator prostaglandins (e.g., PGI2 and PGE2) through binding of smooth muscle IP and EP receptors (35), increase intracellular cAMP concentrations (71, 133), which results in increased potassium channel conductance. Moreover, EETs mediate cerebrovascular dilation through modulation of calcium-activated potassium channel conductance (59). In keeping, hypoxia reduces calcium influx in rabbit basilar arteries (144) and bovine middle cerebral arteries (188). The functional importance of potassium channels is further evidenced following KATP channel blockade with glibenclamide, which reduces both pial vessel dilation (168) and the overall CBF response to hypoxia (118, 182). However, inhibition of potassium channels does not completely inhibit the CBF response to hypoxia, indicating that they are not the only regulator of CBF downstream of vasoactive agents (e.g., adenosine, NO, PGs, and EETs).

Cyclic nucleotides.

Cyclic nucleotides (cAMP and cGMP) exert vasodilatory (184) effects primarily via two pathways; 1) by increasing conductance through potassium channels (172), and 2) by decreasing vascular smooth muscle cell calcium sensitivity. Cyclic nucleotides reduce smooth muscle cell calcium sensitivity by phosphorylating myosin light chain kinase, which leads to its deactivation, and a consequent reduced myosin-actin binding (1, 107).

Mechanisms Leading to a Compromise in Cerebral O2 Delivery During Hemodilution

In contrast to during hypoxemic hypoxia, data in humans (33, 47, 73, 130) and animals (181, 182) (Fig. 9) indicate that CDO2 is impaired during reductions in CaO2 via hemodilution. This may be due to a reduced signal transduction of processes originating from the erythrocyte, due to: 1) a reduction of total hemoglobin levels during hemodilution compared with hypoxemic hypoxia, and 2) a reduction of deoxyhemoglobin produced from gas exchange with cerebral tissue during hemodilution compared with hypoxemic hypoxia (i.e., smaller percentage of deoxyhemoglobin). In humans, during hemodilution, jugular venous saturation is not appreciably reduced (<3% change) compared with baseline (33, 142), whereas during hypoxemic hypoxia jugular venous saturation is reduced progressively (up to ∼20%) with increases in severity (4). The higher SaO2 during hemodilution would result in reduced deoxyhemoglobin-mediated ATP release, nitrite reductase activity, and NO release from SNO (117). Furthermore, Tomiyama et al. (182) showed in a rat model that a majority of the difference in the CBF response between hypoxemic hypoxia and hemodilution is due to increased conductance of KATP channels (182), which are largely responsible for ATP-mediated dilation through vascular smooth muscle hyperpolarization (40, 102, 213). The CBF response during hemodilution may also be blunted in part from the reduced blood viscosity, and therefore the reduced shear (106), which could hinder endothelium-mediated NO release (34, 141, 197, 208).

Fig. 9.

Differential changes in cerebral blood flow (CBF) during hypoxemic hypoxia and hemodilution and the impact on cerebral oxygen delivery (CDO2) in animals. The CBF response to both hypoxemic hypoxia and hemodilution in animals is presented (181, 182). Despite similar reductions in CaO2 between conditions, the CBF response (%Δ from baseline) is ∼100% greater during hypoxemic hypoxia than hemodilution. Consequently, CDO2 is reduced during hemodilution but not hypoxemic hypoxia.

Although the CBF response to a reduced CaO2 is impaired during hemodilution, it is not abolished; thus it seems that some regulatory mechanisms remain intact. Animal studies suggests that NO is a primary factor mediating the CBF response to hemodilution predominantly through upregulation of neuronal nitric oxide synthase (81, 125). Moreover, in the face of reductions in CaO2, there would likely be compensatory increases in oxygen extraction, which may further compensate for the compromise in CDO2 (181).

Clinical Implications and Future Directions

During or following major surgery (e.g., cardiac artery bypass, grafts, transplant, etc.), patients often become acutely hemodiluted and are at risk of suffering acute neurological injury and long-term neurological impairment (132, 165). Indeed, evidence from animal models indicates that hemodilution reduces tissue oxygenation during cardiopulmonary bypass (45) and increases neuronal and mitochondrial injury (38). For example, in patients refusing blood transfusion during surgery (for religious reasons), preoperative [Hb] < 8 g/dl increased the risk of death 16-fold compared with those of higher [Hb] (27). During anesthesia, hemodilution leads to a reduction in CMRO2 (33), which may be indicative that CDO2 is not adequate to maintain metabolic homeostasis, as would normally occur during hypoxemic hypoxia (4). Moreover, the occurrence of tissue hypoxia in traumatic brain injury patients with a tissue oxygenation probe was greater in patients with [Hb] of 7 g/dl vs. [Hb] of 10 g/dl (210). Whether the reduced vasomotor response and thus impaired maintenance of CDO2 during hemodilution is implicated in risk for neurological injury in humans during major surgeries requires further investigation (68). In addition to the implications for various surgical interventions, elucidation of these mechanistic CBF relationships is paramount to our comprehension of myriad pathologies associated with arterial hypoxemia (e.g., sleep apnea, chronic lung diseases, and heart failure) and/or alterations in blood viscosity or hemoglobin levels (e.g., anemic or polycythemic pathologies including von Hippel-Landau or Chuvash diseases). Uncovering the molecular basis of hypoxic adaptation in humans will both inform understanding of hematological and other adaptations involved in hypoxia tolerance and form the basis of novel methods for treating conditions of pathological brain hypoxia. Optimizing CDO2 via multi-modal imaging and/or molecular approaches may provide new insight into the treatment of many hypoxemic, anemic, or polycythemic pathologies and that associated with cerebrovascular complications.

Conclusions

During hypoxemic hypoxia at both sea level and high altitude in healthy humans, elevations in CBF are intimately matched to reductions in CaO2 to maintain CDO2. Studies employing hemodilution, and those of patients with anemia and polycythemia, support the notion that CaO2 has an independent influence on CBF; yet, in the majority of cases when CaO2 is reduced by hemodilution, CDO2 is compromised. The mechanisms regulating CBF during changes in CaO2 are multifactorial but primarily triggered by deoxygenation of hemoglobin (R → T allosteric shift) and consequent erythrocyte release of ATP and SNO, and deoxyhemoglobin nitrite reductase activity. Downstream of this initial process, additional chemical mediators include adenosine, nitric oxide, and epoxyeicosatrienoic acids. The relatively lower CBF increase with hemodilution compared with hypoxemic hypoxia (due to ↓[Hb] and higher jugular venous O2 saturation) provides strong evidence for the role of deoxyhemoglobin as the primary regulator of CBF in hypoxia. Although studies to date support the role of CaO2 as a biological regulator of CBF, due to the dependence of key regulatory mechanisms on the oxygenation state of hemoglobin, maintenance of O2 delivery via CBF is better established during hypoxemic hypoxia, compared with hemodilution.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: R.L.H., M.R., and P.N.A. prepared figures; R.L.H. and P.N.A. drafted manuscript; R.L.H., A.R.B., M.R., D.M.B., and P.N.A. edited and revised manuscript; R.L.H., A.R.B., M.R., D.M.B., and P.N.A. approved final version of manuscript; A.R.B. and D.M.B. interpreted results of experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Adelstein R, Conti M. Phosphorylation of smooth muscle myosin catalytic subunit of adenosine 3′,5′-monophosphate-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem 253: 8347–8350, 1978. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ainslie PN, Ogoh S. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in mammals during chronic hypoxia: a matter of balance. Exp Physiol 95: 251–262, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ainslie PN, Poulin MJ. Ventilatory, cerebrovascular, and cardiovascular interactions in acute hypoxia: regulation by carbon dioxide. J Appl Physiol 97: 149–159, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ainslie PN, Shaw AD, Smith KJ, Willie CK, Ikeda K, Graham J, Macleod DB. Stability of cerebral metabolism and substrate availability in humans during hypoxia and hyperoxia. Clin Sci (Lond) 126: 661–670, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ainslie PN, Subudhi AW. Cerebral blood flow at high altitude. High Alt Med Biol 15: 133–140, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Armstead WM. Role of nitric oxide, cyclic nucleotides, and the activation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in the contribution of adenosine to hypoxia-induced pial artery dilation. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 17: 100–108, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bailey DM, Bärtsch P, Knauth M, Baumgartner RW. Emerging concepts in acute mountain sickness and high-altitude cerebral edema: from the molecular to the morphological. Cell Mol Life Sci 66: 3583–3594, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bailey DM, Rimoldi SF, Rexhaj E, Pratali L, Salmòn CS, Villena M, McEneny J, Young IS, Nicod P, Allemann Y, Scherrer U, Sartori C. Oxidative-nitrosative stress and systemic vascular function in highlanders with and without exaggerated hypoxemia. Chest 143: 444–451, 2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bailey DM, Taudorf S, Berg RMG, Jensen LT, Lundby C, Evans KA, James PE, Pedersen BK, Moller K. Transcerebral exchange kinetics of nitrite and calcitonin gene-related peptide in acute mountain sickness: evidence against trigeminovascular activation? Stroke 40: 2205–2208, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bain AR, Nybo L, Ainslie PN. Cerebrovascular control and metabolism in heat stress. Compr Physiol 5: 1345–1380, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baumgartner RW, Bartsch P, Maggiorini M, Waber U, Oelz O. Enhanced cerebral blood flow in acute mountain sickness. Aviat Space Environ Med 65: 726–729, 1994. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bauser-Heaton HD, Bohlen HG. Cerebral microvascular dilation during hypotension and decreased oxygen tension: a role for nNOS. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 293: H2193–H2201, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beall CM, Laskowski D, Erzurum SC. Nitric oxide in adaptation to altitude. Free Radic Biol Med 52: 1123–1134, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Beall CM. Andean, Tibetan, and Ethiopian patterns of adaptation to high-altitude hypoxia. Integr Comp Biol 46: 18–24, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Beall CM. Two routes to functional adaptation: Tibetan and Andean high-altitude natives. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104, Suppl: 8655–8660, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergfeld GR, Forrester T. Release of ATP from human erythrocytes in response to a brief period of hypoxia and hypercapnia. Cardiovasc Res 26: 40–47, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Berne RM, Rubio R, Curnish RR. Release of adenosine from ischemic brain: effect on cerebral vascular resistance and incorporation into cerebral adenine nucleotides. Circ Res 35: 262–271, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Binks AP, Cunningham VJ, Adams L, Banzett RB. Gray matter blood flow change is unevenly distributed during moderate isocapnic hypoxia in humans. J Appl Physiol 104: 212–217, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bohlen HG. Nitric oxide and the cardiovascular system. Compr Physiol 5: 808–823, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bolotina VM, Najibi S, Palacino JJ, Pagano PJ, Cohen RA. Nitric oxide directly activates calcium-dependent potassium channels in vascular smooth muscle. Nature 368: 850–853, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.van Bommel J, Trouwborst A, Schwarte L, Siegemund M, Ince C, Henny CP. Intestinal and cerebral oxygenation during severe isovolemic hemodilution and subsequent hyperoxic ventilation in a pig model. Anesthesiology 97: 660–670, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bowton DL, Haddon WS, Prough DS, Adair N, Alford PT, Stump DA. Theophylline effect on the cerebral blood flow response to hypoxemia. Chest 94: 371–375, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brass L, Prohovnik I, Pavlakis S, DeVivo D, Piomelli S, Mohr J. Middle cerebral artery blood velocity and cerebral blood flow in sickle cell disease. Stroke 22: 27–30, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Brown M, Wade J, Marshall J. Fundamental importance of arterial oxygen content in the regulation of cerebral blood flow in man. Brain 108: 81–93, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brown MM, Marshall J. Effect of plasma exchange on blood viscosity and cerebral blood flow. Br Med J 284: 1733–1736, 1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brown MM, Marshall J. Regulation of cerebral blood flow in response to changes in blood viscosity. Lancet 1: 604–609, 1985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carson JL, Poses RM, Spence RK, Bonavita G. Severity of anaemia and operative mortality and morbidity. Lancet 1: 727–729, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Claydon VE, Gulli G, Slessarev M, Appenzeller O, Zenebe G, Gebremedhin A, Hainsworth R. Cerebrovascular responses to hypoxia and hypocapnia in Ethiopian high altitude dwellers. Stroke 39: 336–342, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen PJ, Alexander SC, Smith TC, Reivich M, Wollman H. Effects of hypoxia and normocarbia on cerebral blood flow and metabolism in conscious man. J Appl Physiol 23: 183–189, 1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cosby K, Partovi KS, Crawford JH, Patel RP, Reiter CD, Martyr S, Yang BK, Waclawiw MA, Zalos G, Xu X, Huang KT, Shields H, Kim-Shapiro DB, Schechter AN, Cannon RO, Gladwin MT. Nitrite reduction to nitric oxide by deoxyhemoglobin vasodilates the human circulation. Nat Med 9: 1498–1505, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Coyle MG, Oh W, Stonestreet BS. Effects of indomethacin on brain blood flow and cerebral metabolism in hypoxic newborn piglets. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 264: H141–H149, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crossland RF, Durgan DJ, Lloyd EE, Phillips SC, Reddy AK, Marrelli SP, Bryan RM. A new rodent model for obstructive sleep apnea: effects on ATP-mediated dilations in cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 305: R334–R342, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Daif AAA, Hassan YMAEM, Ghareeb NAEG, Othman MM, Mohamed SAM. Cerebral effect of acute normovolemic hemodilution during brain tumor resection. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol 24: 19–24, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Davis ME, Grumbach IM, Fukai T, Cutchins A, Harrison DG. Shear stress regulates endothelial nitric-oxide synthase promoter activity through nuclear factor kappaB binding. J Biol Chem 279: 163–168, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davis RJ, Murdoch CE, Ali M, Purbrick S, Ravid R, Baxter GS, Tilford N, Sheldrick RLG, Clark KL, Coleman RA. EP4 prostanoid receptor-mediated vasodilatation of human middle cerebral arteries. Br J Pharmacol 141: 580–585, 2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Demoncheaux EAG, Higenbottam TW, Foster PJ, Borland CDR, Smith APL, Marriott HM, Bee D, Akamine S, Davies MB. Circulating nitrite anions are a directly acting vasodilator and are donors for nitric oxide. Clin Sci 102: 77–83, 2002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dempsey JA, Forster HV. Mediation of ventilatory adaptations. Physiol Rev 62: 262–346, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dian-San S, Xiang-Rui W, Yongjun Z, Yan-Hua Z. Low hematocrit worsens cerebral injury after prolonged hypothermic circulatory arrest in rats. Can J Anaesth 53: 1220–1229, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Dietrich HH, Ellsworth ML, Sprague RS, Dacey RG. Red blood cell regulation of microvascular tone through adenosine triphosphate. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1294–H1298, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dietrich HH, Horiuchi T, Xiang C, Hongo K, Falck JR, Dacey RG. Mechanism of ATP-induced local and conducted vasomotor responses in isolated rat cerebral penetrating arterioles. J Vasc Res 46: 253–264, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dietrich HH, Kajita Y, Dacey RG. Local and conducted vasomotor responses in isolated rat cerebral arterioles. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 271: H1109–H1116, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dimmeler S, Fleming I, Fisslthaler B, Hermann C, Busse R, Zeiher MA. Activation of nitric oxide synthase in endothelial cells by Akt-dependent phosphorylation. Nature 399: 601–605, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Doyle MP, Pickering RA, DeWeert TM, Hoekstra JW, Pater D. Kinetics and mechanism of the oxidation of human deoxyhemoglobin by nitrites. J Biol Chem 256: 12393–12398, 1981. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Droma Y, Hanaoka M, Basnyat B, Arjyal A, Neupane P, Pandit A, Sharma D, Miwa N, Ito M, Katsuyama Y, Ota M, Kubo K. Genetic contribution of the endothelial nitric oxide synthase gene to high altitude adaptation in sherpas. High Alt Med Biol 7: 209–220, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Duebener LF, Sakamoto T, Hatsuoka S, Stamm C, Zurakowski D, Vollmar B, Menger MD, Schäfers HJ, Jonas RA. Effects of hematocrit on cerebral microcirculation and tissue oxygenation during deep hypothermic bypass. Circulation 104: I260–I264, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Duling BBR, Berne RM. Longitudinal gradients in periarteriolar oxygen tension. Circ Res 27: 669–678, 1970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ekelund A, Reinstrup P, Ryding E, Andersson AM, Molund T, Kristiansson KA, Romner B, Brandt L, Säveland H. Effects of Iso- and hypervolemic hemodilution on regional cerebral blood flow and oxygen delivery for patients with vasospasm after aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Acta Neurochir (Wien) 144: 703–713, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ellsworth ML, Ellis CG, Goldman D, Stephenson AH, Dietrich HH, Sprague RS. Erythrocytes: oxygen sensors and modulators of vascular tone. Physiology (Bethesda) 24: 107–116, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ellsworth ML, Forrester T, Ellis CG, Dietrich HH. The erythrocyte as a regulator of vascular tone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 269: H2155–H2161, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Emerson TE, Raymond RM. Involvement of adenosine in cerebral hypoxic hyperemia in the dog. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 241: H134–H138, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eriksson S, Hagenfeldt L, Law D, Patrono C, Pinca E, Wennmalm A. Effect of prostaglandin synthesis inhibitors on basal and carbon dioxide stimulated cerebral blood flow in man. Acta Physiol Scand 117: 203–211, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fan JL, Burgess KR, Basnyat R, Thomas KN, Peebles KC, Lucas SJE, Lucas RAI, Donnelly J, Cotter JD, Ainslie PN. Influence of high altitude on cerebrovascular and ventilatory responsiveness to CO2. J Physiol 588: 539–549, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Fan JL, Burgess KR, Thomas KN, Peebles KC, Lucas SJE, Lucas RAI, Cotter JD, Ainslie PN. Influence of indomethacin on the ventilatory and cerebrovascular responsiveness to hypoxia. Eur J Appl Physiol 111: 601–610, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Faraci FM, Sobey CG. Role of potassium channels in regulation of cerebral vascular tone. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 18: 1047–1063, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Forrester T, Harper AM, MacKenzie ET, Thomson EM. Effect of adenosine triphosphate and some derivatives on cerebral blood flow and metabolism. J Physiol 296: 343–355, 1979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Foster GE, Ainslie PN, Stembridge M, Day TA, Bakker A, Lucas SJE, Lewis NCS, MacLeod DB, Lovering AT. Resting pulmonary haemodynamics and shunting: a comparison of sea-level inhabitants to high altitude Sherpas. J Physiol 592: 1397–1409, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Fredricks KT, Liu Y, Rusch NJ, Lombard JH. Role of endothelium and arterial K+ channels in mediating hypoxic dilation of middle cerebral arteries. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 267: H580–H586, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fuentes E, Palomo I. Extracellular ATP metabolism on vascular endothelial cells: A pathway with pro-thrombotic molecules. Vascul Pharmacol 75: 1–6, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gebremedhin D, Ma YH, Falck JR, Roman RJ, VanRollins M, Harder DR. Mechanism of action of cerebral epoxyeicosatrienoic acids on cerebral arterial smooth muscle. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 263: H519–H525, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gibson GE, Pulsinelli W, Blass JP, Duffy TE. Brain dysfunction in mild to moderate hypoxia. Am J Med 70: 1247–1254, 1981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.González-Alonso J, Richardson RS, Saltin B. Exercising skeletal muscle blood flow in humans responds to reduction in arterial oxyhaemoglobin, but not to altered free oxygen. J Physiol 530: 331–341, 2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gottstein U, Paulson OB. The effect of intracarotid aminophylline infusion on the cerebral circulation. Stroke 3: 560–565, 1972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Goueli SA, Ahmed K. Indomethacin and inhibition of protein kinase reactions. Nature 287: 171–172, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Grotta J, Ackerman R, Correia J, Fallick G, Chang J. Whole blood viscosity parameters and cerebral blood flow. Stroke 13: 296–301, 1982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hackett PH. The cerebral etiology of high-altitude cerebral edema and acute mountain sickness. Wilderness Environ Med 10: 97–109, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Haller C, Kuschinsky W. Moderate hypoxia: reactivity of pial arteries and local effect of theophylline. J Appl Physiol 63: 2208–2215, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Hare GMT. Anaemia and the brain. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 17: 363–369, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hare GMT. At what point does hemodilution harm the brain? Can J Anaesth 53: 1171–1174, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Harrell JW, Schrage WG. Cyclooxygenase-derived vasoconstriction restrains hypoxia-mediated cerebral vasodilation in young adults with metabolic syndrome. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 306: H261–H269, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Hayward JN, Baker MA. Role of cerebral arterial blood in the regulation of brain temperature in the monkey. Am J Physiol 215: 389–403, 1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hein TW, Xu W, Ren Y, Kuo L. Cellular signalling pathways mediating dilation of porcine pial arterioles to adenosine A 2A receptor activation. Cardiovasc Res 99: 156–163, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Heyman BA, Patterson JL, Duke TW. Cerebral circulation and metabolism in sickle cell and other chronic anemias, with observations on the effects of oxygen inhalation. J Clin Invest: 824–828, 1952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Hino A, Ueda S, Mizukawa N, Imahori Y, Tenjin H. Effect of hemodilution on cerebral hemodynamics and oxygen metabolism. Stroke 23: 423–426, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Hoffman WE, Albrecht RF, Miletich DJ. The role of adenosine in CBF increases during hypoxia in young vs. aged rats. Stroke 15: 124–129, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hoiland RL, Ainslie PN, Wildfong KW, Smith KJ, Bain AR, Willie CK, Foster G, Monteleone B, Day TA. Indomethacin-induced impairment of regional cerebrovascular reactivity: implications for respiratory control. J Physiol 593: 1291–1306, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holloway RL. The human brain evolving: a personal retrospective. Annu Rev Anthropol 37: 1–19, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Horiuchi T, Dietrich HH, Hongo K, Dacey RG. Comparison of P2 receptor subtypes producing dilation in rat intracerebral arterioles. Stroke 34: 1473–1478, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Horiuchi T, Dietrich HH, Tsugane S, Dacey RG. Analysis of purine- and pyrimidine-induced vascular responses in the isolated rat cerebral arteriole. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H767–H776, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Huang SY, Moore LG, McCullough RE, McCullough RG, Micco AJ, Fulco C, Cymerman A, Manco-Johnson M, Weil JV, Reeves JT. Internal carotid and vertebral arterial flow velocity in men at high altitude. J Appl Physiol 63: 395–400, 1987. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Hudak ML, Koehler C, Rosenberg AA, Traystman RJ, Jones MD. Effect of hematocrit on cerebral blood flow. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 251: H63–H70, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hudetz GA, Shen H, Kampine JP. Nitric oxide from neuronal NOS plays critical role in cerebral capillary flow response to hypoxia. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 274: H982–H989, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Humphrey PR, du Boulay GH, Marshall J, Pearson TC, Russell RW, Slater NG, Symon L, Wetherley-Mein G, Zilkha E. Viscosity, cerebral blood flow and haematocrit in patients with paraproteinaemia. Acta Neurol Scand 61: 201–209, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Humphrey PR, Du Boulay GH, Marshall J, Pearson TC, Russell RW, Symon L, Wetherley-Mein G, Zilkha E. Cerebral blood-flow and viscosity in relative polycythaemia. Lancet 2: 873–877, 1979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Humphrey PR, Michael J, Pearson TC. Management of relative polycythaemia: studies of cerebral blood flow and viscosity. Br J Haematol 46: 427–433, 1980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ibaraki M, Shinohara Y, Nakamura K, Miura S, Kinoshita F, Kinoshita T. Interindividual variations of cerebral blood flow, oxygen delivery, and metabolism in relation to hemoglobin concentration measured by positron emission tomography in humans. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 30: 1296–1305, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Ide K, Worthley M, Anderson T, Poulin MJ. Effects of the nitric oxide synthase inhibitor l-NMMA on cerebrovascular and cardiovascular responses to hypoxia and hypercapnia in humans. J Physiol 584: 321–332, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ikeuchi Y, Nishizaki T. ATP activates the potassium channel and enhances cytosolic Ca2+ release via a P2Y purinoceptor linked to pertussis toxin-insensitive G-protein in brain artery endothelial cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 215: 1022–1028, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Imray C, Chan C, Stubbings A, Rhodes H, Patey S, Wilson MH, Bailey DM, Wright AD; Birmingham Medical Research Expeditionary Society. Time course variations in the mechanisms by which cerebral oxygen delivery is maintained on exposure to hypoxia/altitude. High Alt Med Biol 15: 21–27, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Jagger JE, Bateman RM, Ellsworth ML, Ellis CG. Role of erythrocyte in regulating local O2 delivery mediated by hemoglobin oxygenation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2833–H2839, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Jansen GFA, Basnyat B. Brain blood flow in Andean and Himalayan high-altitude populations: evidence of different traits for the same environmental constraint. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 31: 706–714, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Jansen GFA, Krins A, Basnyat B, Bosch A, Odoom JA. Cerebral autoregulation in subjects adapted and not adapted to high altitude. Stroke 31: 2314–2318, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Jansen GFA, Krins A, Basnyat B, Odoom JA, Ince C. Role of the altitude level on cerebral autoregulation in residents at high altitude. J Appl Physiol 103: 518–523, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Jansen GFA, Krins A, Basnyat B. Cerebral vasomotor reactivity at high altitude in humans. J Appl Physiol 86: 681–686, 1999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Jensen JB, Sperling B, Severinghaus JW, Lassen NA. Augmented hypoxic cerebral vasodilation in men during 5 days at 3,810 m altitude. J Appl Physiol 80: 1214–1218, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Jensen JB, Wright a D, Lassen NA, Harvey TC, Winterborn MH, Raichle ME, Bradwell AR. Cerebral blood flow in acute mountain sickness. J Appl Physiol 69: 430–433, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Jia L, Bonaventura C, Bonaventura J, Stamler JS. S-nitrosohaemoglobin: a dynamic activity of blood involved in vascular control. Nature 380: 221–226, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Jiang C, Haddad GG. A direct mechanism for sensing low oxygen levels by central neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 91: 7198–7201, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Jiang H, Anderson GD, Mcgiff JC. Red blood cells (RBCs), epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs) and adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Pharmacol Reports 62: 468–474, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]