Abstract

The oxytocin (OT) and vasopressin (VP) neurons of the supraoptic nucleus (SON) demonstrate characteristics of “metabolic sensors”. They express insulin receptors and glucokinase (GK). They respond to an increase in glucose and insulin with an increase in intracellular [Ca2+] and increased OT and VP release that is GK dependent. Although this is consistent with the established role of OT as an anorectic agent, how these molecules function relative to the important role of OT during lactation and whether deficits in this metabolic sensor function contribute to obesity remain to be examined. Thus, we evaluated whether insulin and glucose-induced OT and VP secretion from perifused explants of the hypothalamo-neurohypophyseal system are altered during lactation and by diet-induced obesity (DIO). In explants from female day 8 lactating rats, increasing glucose (Glu, 5 mM) did not alter OT or VP release. However, insulin (Ins; 3 ng/ml) increased OT release, and increasing the glucose concentration in the presence of insulin (Ins+Glu) resulted in a sustained elevation in both OT and VP release that was not prevented by alloxan, a GK inhibitor. Explants from male DIO rats also responded to Ins+Glu with an increase in OT and VP regardless of whether obesity had been induced by feeding a high-fat diet (HFD). The HFD-DIO rats had elevated body weight, plasma Ins, Glu, leptin, and triglycerides. These findings suggest that the role of SON neurons as metabolic sensors is diminished during lactation, but not in this animal model of obesity.

Keywords: oxytocin, lactation, obesity, insulin, glucokinase

oxytocin (ot) is an anorectic agent in rodents and humans (40, 42, 60, 61), and deficits in OT are associated with obesity in humans (9, 26, 44) and mice (7, 39, 52, 53). Studies on the role of OT in appetite regulation have largely focused on the parvocellular OT neurons in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) (14, 23, 40, 41), but magnocellular neurons (MCNs) in the supraoptic nucleus (SON) and PVN are also a major source of OT in the brain, as well as the circulation (28). Since these neurons express glucokinase [GK (51)] and insulin receptors [InsR (24, 59)], they have an appropriate molecular footprint to function as “metabolic sensors” (32). GK (hexokinase IV) is recognized as the molecule underlying glucose sensing in pancreatic β-cells (27). In contrast to other mammalian hexokinases (HKI, HKII, and HKIII), GK has two important characteristics that allow it to function as a glucose sensor: 1) its affinity for glucose is at least 20 times lower than other mammalian HKs that are fully saturated at plasma glucose concentrations, and 2) it is not inhibited by glucose-6-phosphate, the product of hexokinase-mediated glycolysis, as is the case for other HKs (27). Neurons in the ventromedial nucleus that have been characterized as “metabolic sensors” also express GK and InsR (32). In those neurons, glucose induces depolarization via GK-mediated inactivation of ATP-sensitive K+ channels (KATP), and insulin promotes glucose uptake by glucose transporter 4 (GLUT4) (32). The SON OT and VP neurons also appear to function as metabolic sensors, because increases in insulin and glucose induce increases in intracellular [Ca2+] and stimulate OT and VP release from explants of the hypothalamo-neurohypophyseal system (HNS) from male rats in a GK-dependent manner (51). However, while functioning as metabolic sensors is consistent with an anorectic role for OT, OT also plays a distinct and critical role during lactation by acting on the mammary glands to induce milk let-down (49). During lactation, large amounts of OT are released in response to suckling (20, 64), but simultaneously increased food intake is required to meet the metabolic needs of milk production (15). This may result in a diminished role for SON neurons as metabolic sensors during lactation. Also, during lactation, increased glycolysis may be required to meet the increased energy demands associated with suckling-induced hormone secretion. Thus, we postulated that during lactation, SON neurons switch from using GK-mediated glycolysis to monitor body nutrient status to relying on insulin-mediated glucose uptake and glycolysis mediated by hexokinases with higher affinities for glucose than GK (27) to support the metabolic demands associated with suckling-induced OT secretion. To test this hypothesis, we examined whether insulin plus glucose-induced OT and VP release remains GK-dependent in HNS explants from lactating females.

Since deficits in OT are associated with obesity (9, 26, 44), we also postulated that decreased glucose sensitivity and/or insulin resistance in the OT neurons could result in a reduction in OT-mediated anorexia leading to obesity. We tested this hypothesis by evaluating the OT and VP response to insulin and glucose in HNS explants obtained from rats either susceptible or resistant to diet-induced obesity (DIO) (35). We chose this animal model of obesity because of its relevance to human obesity (35): 1) since some humans are more susceptible to DIO than others, the existence of related strains of diet-resistant (DR) and susceptible rats (DIO) is relevant to humans; 2) the higher-fat/palatable diet used to induce obesity in this strain is relevant to humans; and 3) insulin-induced anorexia is reduced in this model (8). Furthermore, DIO is associated with deficits in lactation (62), and in humans, obesity is associated with difficulties in initiating and maintaining breastfeeding (1, 2, 6, 45). Thus, evaluation of the metabolic sensor role of SON neurons in obesity may be relevant to understanding the association between obesity and problems with lactation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethical Approval

All animal protocols were performed in accordance with the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Colorado School of Medicine.

Animals

Lactating female rats.

Sprague-Dawley rats were purchased with their litters (10 pups/mother) from Charles River Laboratories. They were 4–6 days postpartum on arrival. On postpartum day 8, the lactating mothers were decapitated, their brains were removed, and HNS explants were dissected and prepared for perifusion (see Perifusion protocol). The pups were either euthanized or reassigned to another approved animal protocol. On postpartum day 8, the lactating mothers weighed 370 ± 23 g.

DIO and DR male rats.

Male rats from the DIO or DR strains developed by Dr. Barry Levin (Newark, NJ) (31) were obtained from Taconic Biosciences [TacLevin:CD(SD)DIO; TacLevin:CD(SD)DR]. The DIO and DR lines have the same Sprague-Dawley genetic background, but they have been selectively inbred over many generations for their differential response to an obesogenic diet. The polygenic predisposition for obesity or leanness has been extensively characterized (31, 33, 35, 43). The rats were 5 or 6 wk of age upon arrival. They were allowed to equilibrate on normal rat chow (6% fat), and at 9 wk of age, they were either continued on 6% fat chow or switched to a defined high-energy diet (Research Diets D12266B; 31% fat, 58% carbohydrate) for 6 wk. Body weights were monitored weekly, and food intake was measured after 6 wk on the specified diet. Body fat content was determined at 1, 3, 4, and 6 wk on the diet, as described previously (38). At 15 wk of age (6 wk of diet), animals were decapitated, HNS explants were prepared for perifusion (see Perifusion protocol), and trunk blood was collected for determination of plasma insulin, leptin, glucose, cholesterol, triglycerides, and nonesterified fatty acid concentrations, as described previously (18, 34). Animals were fasted for 4 h prior to death.

Hormone Release Experiments

Explant preparation.

HNS explants were obtained from decapitated day 8 lactating female Sprague-Dawley (SD) rats, 48 h water-deprived male SD rats, or male DIO or DR rats fed a high-fat or normal diet for 6 wk. The explants included the OT and VP neurons of the SON with their axonal projections extending through the median eminence and terminating in the neural lobe. The explants also included the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis, the suprachiasmatic nucleus, and the arcuate nucleus. PVN was not included.

Perifusion protocol.

The explants were placed in individual perifusion chambers and perifused at ∼2.0 ml/h with F12 nutrient mixture supplemented with 20% FCS, 100 U/ml penicillin, 100 μg/ml streptomycin and 1×104 M bacitracin. Bacitracin is added to prevent hormone degradation. The medium was warmed (37°C) and gassed (95% O2-5% CO2) immediately before entering the chamber. Outflow from the chambers was collected in 20-min fractions. The explants were perifused for 4 h in basal medium (1 mM Glu) before beginning the experiment to allow hormone release from the explants to stabilize. VP and OT concentrations in the perifusate fractions were determined by radioimmunoassay, as described previously (63). Basal hormone release for each explant was determined during the last hour of equilibration, and hormone release in response to experimental manipulations is expressed as a percentage of this basal release.

Statistical Analysis

In the perifusion experiments, ANOVA with repeated measures followed by post hoc simple main effects analysis was performed to evaluate changes in VP and OT release and to compare responses between experimental groups. Time control explants were included in each experiment. In the DIO/DR experiment, two-way ANOVA was used to evaluate diet and strain effects on body composition and plasma components.

RESULTS

Effect of Insulin and Glucose on OT and VP Release During Lactation

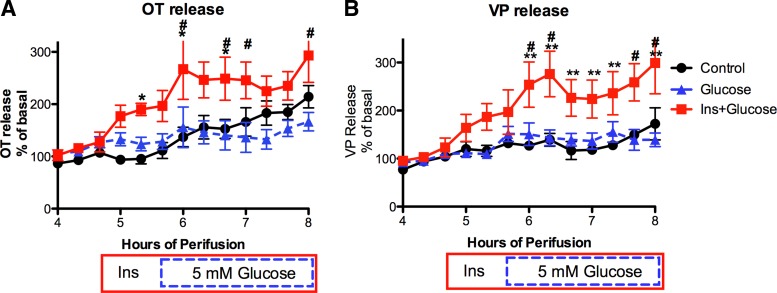

Following the 4-h equilibration period, HNS explants from 8-day postpartum, lactating rats were exposed to one of the following conditions during the subsequent perifusion period: 1) basal conditions (Control) for 4 h; 2) basal conditions for an hour followed by 5 mM glucose (Glucose); or 3) insulin (3 ng/ml) alone for 1 h followed by insulin (3 ng/ml) + 5 mM glucose (Ins+Glucose) for the remainder of the perifusion. As shown in Fig. 1, increasing the glucose concentration from 1 to 5 mM did not alter OT or VP release. However, insulin (3 ng/ml) significantly increased OT release, and increasing the glucose concentration in the presence of insulin resulted in a sustained elevation in both OT and VP release. This response differed from that previously reported in explants from male rats, in which glucose alone significantly increased VP (but not OT) release (51).

Fig. 1.

Oxytocin (OT) and vasopressin (VP) release from hypothalamo-neurohypophyseal system (HNS) explants from lactating rats in response to 1) an increase in the glucose concentration from 1 to 5 mM (glucose; blue dashed line with triangles); 2) insulin alone (3 ng/ml) followed by increasing the glucose concentration in the continued presence of insulin (Ins+Glucose; red solid line with squares); or 3) maintaining the basal insulin (70 pg/ml from FBS) and glucose (1 mM) concentrations throughout the experiment (Control; black line with circles). In the Ins+Glucose group, 3 ng/ml insulin was present from 4.67 h to the end of the perifusion (red solid box). In all except the Control group, the glucose concentration was 5 mM from 5.67 h through the end of the perifusion (blue dashed box). Increasing the glucose concentration (at 5.67 h) did not alter OT or VP release. However, insulin alone increased OT release, and the subsequent increase in the glucose concentration resulted in a sustained elevation in both OT and VP release. Two-way ANOVA: OT release: Ftime = 17.17, P < 0.0001; Ftreatment = 7.57, P = 0.0055; Finteraction = 2.72, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.01 control vs. Ins+Glucose; #P < 0.01 Glu vs. Ins+Glucose. VP release: Ftime = 26.14, P < 0.0001; Ftreatment = 8.826, P = 0.0029; Finteraction = 5.35, P < 0.0001. **P < 0.001 control vs. Ins+Glucose; #P < 0.01 Glu vs. Ins+Glucose. Basal release: 344 ± 42 pg OT/ml and 607 ± 78 pg VP/ml perifusion medium. n = 6/group.

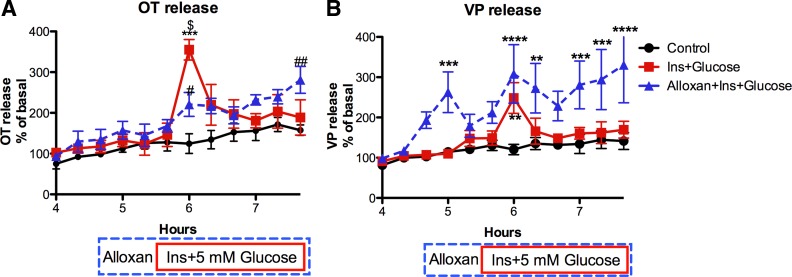

Role of GK in OT and VP Release During Lactation

To test the hypothesis that during lactation, glycolysis in SON neurons becomes less dependent on GK-mediated glycolysis to support the metabolic demands associated with suckling-induced OT secretion, HNS explants from 8-day postpartum, lactating rats were exposed to insulin (3 ng/ml) and an increase in glucose (from 1 to 5 mM) in the presence or absence of alloxan (4 mM), an inhibitor of GK. As shown in Fig. 2, both OT and VP release were increased by insulin plus 5 mM glucose in the presence of alloxan. Thus, during lactation, the increases in OT and VP release induced by elevated glucose in the presence of insulin is not GK dependent. This is in contrast to male rats, in which alloxan blocked the response to insulin plus glucose (51). The difference in the time course of the response to insulin plus glucose in Figs. 1 and 2 probably reflects the difference in the exposure pattern. In Fig. 2, insulin and glucose were added simultaneously and resulted in an abrupt increase in OT and VP release. In contrast, in Fig. 1, the slow and sustained increase in OT and VP release resulted from an initial exposure to insulin followed by an increase in glucose. The abrupt increase in OT and VP release in response to the simultaneous addition of insulin and glucose may have diminished the availability of readily releasable hormone, resulting in rapid termination of the response rather than a sustained response. Similar responses were observed to the simultaneous addition of insulin and glucose in our prior publication (51).

Fig. 2.

Effect of alloxan (4 mM), an inhibitor of glucokinase (GK), on OT (A) and VP (B) release from HNS explants from lactating rats in response to increasing the insulin (3 ng/ml) and glucose (5 mM) concentrations at 5.67 h of perifusion. In the alloxan group, alloxan was present from 4.7 h until the end of the perifusion (blue dashed box). Insulin and glucose were present from 5.67 h until the end of the perifusion in all except the basal group (shown by the red solid box). Alloxan did not prevent the increase in OT or VP release induced by Ins+Glucose. Alloxan alone (from 4.6–5.6 h) did not alter OT release, but significantly increased VP release. Two-way ANOVA: OT release: Ftime = 19.18, P < 0.0001; Ftreatment = 13.87, P = 0.0004; Finteraction = 3.97, P < 0.0001. ***P < 0.0001 control vs. Ins+Glucose; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 control vs. Alloxan+Ins+Glucose. $P < 0.0001 Ins+Glucose vs. Alloxan+Ins+Glucose. VP release: Ftime = 12.03, P < 0.0001; Ftreatment = 16.42, P = 0.0002; Finteraction = 2.88, P < 0.0001. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001 vs. control. Basal release: 298 ± 37 pg OT/ml and 476 ± 63 pg VP/ml perifusion medium. n = 6/group.

GK Dependence of Insulin and Glucose Response in Dehydration

To determine whether other extended stimuli for OT and VP release altered the GK dependence of insulin plus glucose stimulation of OT and VP release similar to lactation, the effect of dehydration was evaluated. HNS explants from 48-h water-deprived male rats were exposed to insulin (3 ng/ml) and an increase in glucose (from 1 to 5 mM) in the presence or absence of alloxan (4 mM). As shown in Fig. 3, in the absence of alloxan, OT and VP release was stimulated by exposure to insulin plus glucose, but this was completely blocked by alloxan. Thus, in contrast to lactation, the OT and VP responses to insulin plus glucose remain GK dependent following 48 h of dehydration. Dehydration is another chronic stimulus for OT and VP release.

Fig. 3.

Effect of dehydration on alloxan inhibition of Ins+Glucose stimulation of OT (A) and VP (B) release from male HNS explants. The drug delivery protocol is the same as in Fig. 2. Ins+glucose increased OT and VP release, but this was not observed in the presence of alloxan. Two-way ANOVA: OT release: Ftime = 2.8, P = 0.0022; Ftreatment = 7.77, P = 0.0048; Finteraction = 3.93, P < 0.0001. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 Ins+Glucose vs. Alloxan+Ins+Glucose. VP release: Ftime = 9.4, P < 0.0001; Ftreatment = 8.16, P = 0.004; Finteraction = 2.93, P = 0.001. **P < 0.01 Ins+Glucose vs. Control and Alloxan+Ins+Glucose. Basal release: 137 ± 17 pg OT/ml and 180 ± 23 pg VP/ml perifusion medium. n = 6/group.

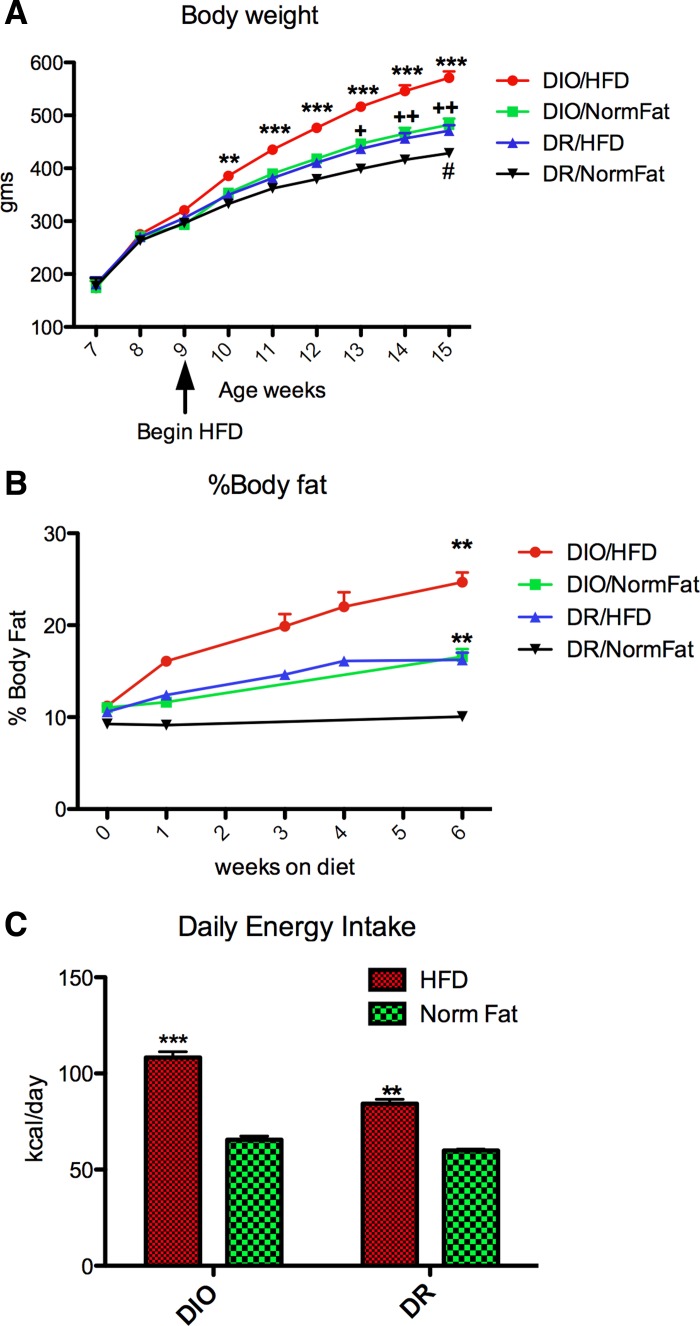

Induction of Obesity in DIO Rats

As shown in Fig. 4, 6 wk on the HFD induced an increase in body weight and body fat content in both DIO and DR rats. However, the DIO rats fed the HFD gained more weight and more body fat than the DR rats fed the HFD, and they had higher energy intake. Both DIO and DR rats on the HFD ate more and had higher energy intake than either DIO or DR rats fed the normal fat diet (NFD). DIO rats fed NFD gained more weight than the DR rats fed NFD, although energy intake was similar after 6 wk. This reflects the higher “feed efficiency” and lower metabolic requirements in DIO rats (31). However, it is worth noting that energy intake was measured after 6 wk on the diet and could have been higher in DIO rats at an earlier time point. As shown in Table 1, the DIO rats fed the HFD also had significantly elevated plasma glucose, insulin, leptin, and triglycerides. Thus, 6 wk on the HFD was adequate to induce obesity in the DIO strain. Although the DR rats fed the HFD also gained more weight than DR rats fed NFD, their weight did not exceed that of the DIO rats fed the NFD.

Fig. 4.

Effect of a high-fat diet (HFD) and normal-fat diet (NFD) on body weight (A), % body fat (B), and energy intake (C) in diet-induced obesity (DIO) and diet-resistant (DR) strains of rats. The HFD induced an increase in body weight and percentage of body fat in both DIO and DR rats, but the DIO/HFD group gained more weight and more body fat than the DR/HFD group. Two-way ANOVA in A: Ftime = 17.87, P < 0.0001; Fstrain/diet = 13.9, P < 0.0001, Finteraction = 17.55, P < 0.0001. **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.0001 DIO/HFD vs. DR/NFD; +P < 0.01, ++P < 0.001 DIO/NFD vs. DR/NFD, #P < 0.05 DR/HFD vs. DR/NFD. B: Fdiet = 77.09, P < 0.0001; Fstrain = 85.16, P < 0.0001, Finteraction = 1.5, NS. **P < 0.0001, HFD vs. NFD in both strains. C: 24-h energy intake after 6 wk on HFD or NFD. Two-way ANOVA: Fdiet = 249.7, P < 0.0001; Fstrain = 48.66, P < 0.0001; Finteraction = 18.69, P < 0.0001. ***P < 0.0001 vs. all other groups; **P < 0.0001 vs. both NFD groups. n = 12/group.

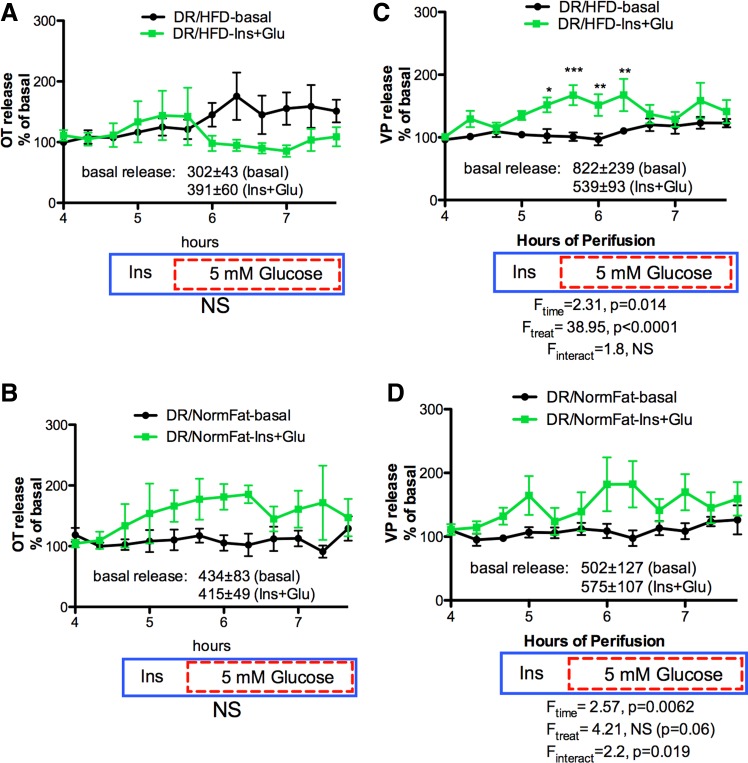

Fig. 6.

Effect of HFD and NFD on Ins+Glucose stimulated OT (A and B) and VP (C and D) release from HNS explants from DR explants. The drug delivery protocol is as described in Fig. 5. OT release was not significantly stimulated by Ins+Glucose in explants from DR rats on either diet (A and B). VP release was significantly elevated by Ins+Glucose in the DR/HFD explants (Ftreatment = 38.95, P < 0.0001) and slightly increased in the DR/NFD explants (Finteraction = 2.2, P = 0.019). *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. n = 5 in DR/NormFat-basal group; n = 6 in all other groups.

Table 1.

Plasma values in DIO and DR rats fed HFD or NFD for 6 wk

| Strain | Diet | Glucose, mmol/l | Insulin, ng/ml | Leptin, ng/ml | Cholesterol, mg/dl | Triglycerides, mg/dl | NEFA, mmol/l |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DIO | HFD: n = 10 | 9.67 ± 0.45 | 2.11 ± 0.26 | 7.30 ± 0.59 | 78.49 ± 4.69 | 176.52 ± 13.46 | 1.32 ± 0.11 |

| NFD: n = 10 | 8.21 ± 0.34 | 0.91 ± 0.21 | 2.54 ± 0.41 | 59.44 ± 3.18 | 140.10 ± 13.94 | 1.25 ± 0.06 | |

| DR | HFD: n = 10 | 8.87 ± 0.32 | 1.32 ± 0.36 | 2.51 ± 0.30 | 85.96 ± 6.69 | 139.71 ± 12.27 | 1.03 ± 0.04 |

| NFD: n = 10 | 7.46 ± 0.27 | 0.73 ± 0.10 | 1.1 ± 0.20 | 62.04 ± 3.69 | 79.10 ± 12.40 | 0.98 ± 0.04 | |

| Two-way ANOVA | Diet | P = 0.0002 | P = 0.0005 | P < 0.0001 | P < 0.0001 | P = 0.0007 | NS |

| Strain | P = 0.03 | P = 0.04 | P < 0.0001 | NS | P = 0.0006 | P < 0.0001 | |

| Interaction | NS | NS | P = 0.0002 | NS | NS | NS |

Values are expressed as means ± SE. DIO, diet-induced obesity; DR, diet-resistant; HFD, high-fat diet; NFD, normal-fat diet; NEFA, nonesterified fatty acids; NS, not significant.

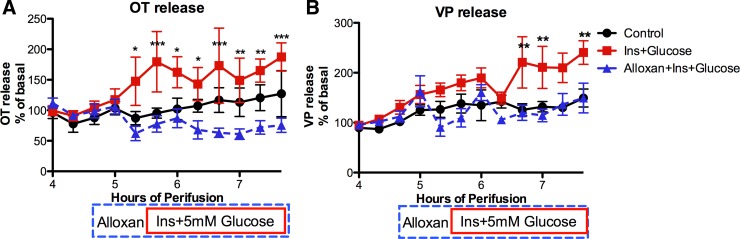

Effect of DIO on OT and VP Responses to Insulin Plus Glucose

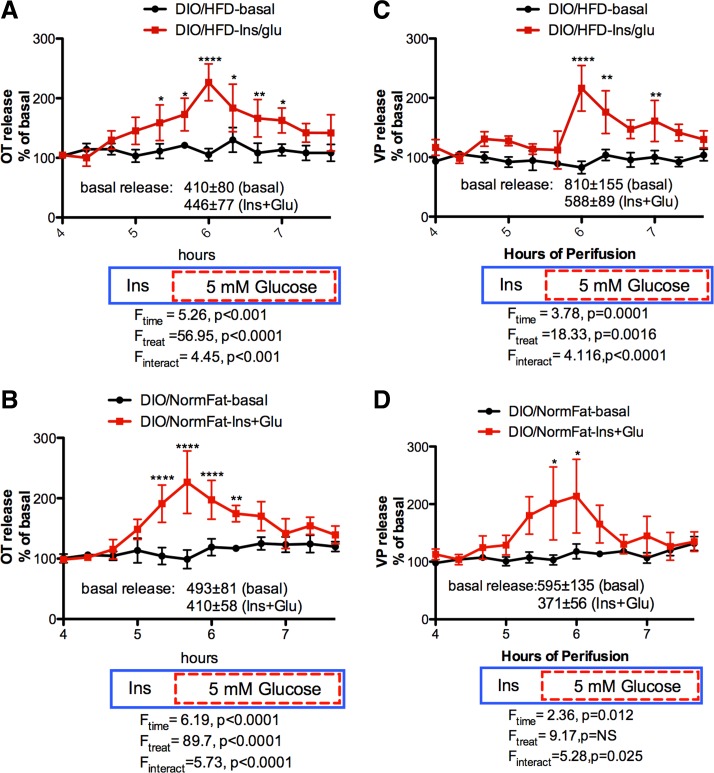

As shown in Fig. 5, explants from DIO rats fed either the HFD or NFD showed robust OT and VP responses to increasing the glucose concentration in the presence of insulin. The response was not significantly different between DIO rats on the HFD compared with the NFD. In addition, a significant increase in OT was observed in response to insulin alone independent of diet (Fig. 5, A and B). However, the increase in VP release was delayed in explants from DIO rats on the HFD (Fig. 5C), indicating that insulin alone did not increase VP release from these explants. Thus, induction of obesity in the DIO strain with a HFD did not alter the effect of insulin and insulin plus glucose on OT release, but may have induced insulin resistance in the VP neurons.

Fig. 5.

Effect of HFD and NFD on Ins+Glucose stimulated OT (A and B) and VP (C and D) release from HNS explants from DIO rats. In the Ins+Glucose group, 3 ng/ml insulin was present from 4.67 h to the end of the perifusion (blue solid box), and except in the control, the glucose concentration was 5 mM from 5.67 h through the end of the perifusion (red dashed box). Ins+Glucose significantly increased both OT and VP release from DIO explants independent of diet. Insulin alone significantly increased OT release from DIO explants independent of diet at 5.33 h of perifusion, but not VP release. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001; n = 6/group.

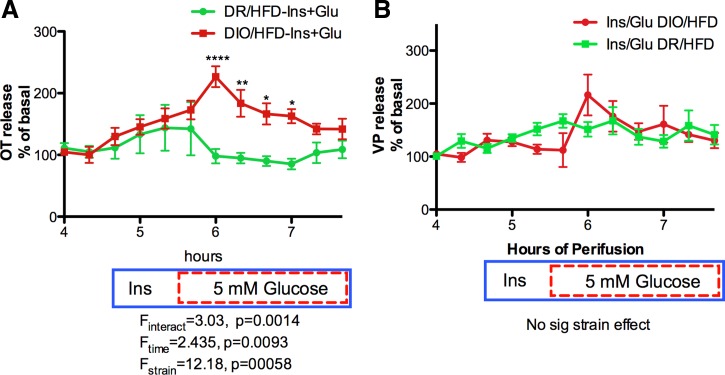

In contrast, in explants from the DR strain (Fig. 6, A–D), OT and VP release in response to insulin plus glucose was reduced compared with the response in DIO explants (Fig. 5), and only the VP response to insulin plus glucose in DR rats on the HFD reached statistical significance (Fig. 6C). The absence of any OT response in the DR/HFD explants resulted in a significant strain difference in OT release (Fig. 7A), but there is no significant strain difference in VP release (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Strain comparison of Ins+Glucose stimulated OT (A) and VP (B) responses. The drug delivery protocol is as described in Fig. 5. The absence of an OT response to Ins+Glucose in the DIO/HFD explants resulted in a significant strain difference between DIO/HFD and DIO/NFD explants (Fstrain = 12.18, P = 0.00058) in the OT response (A), but this was not present in the VP response (B) *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ****P < 0.0001.

DISCUSSION

Although OT is recognized as an anorectic agent (40, 42, 60, 61), it has other important roles in the body. Classically, it is recognized for its role in stimulating uterine contraction during parturition (48, 49). Similarly, it causes contraction of smooth muscles in the mammary glands, an action that is essential for milk let-down during lactation (49). Its actions on the mammary glands and uterus require release of large amounts of OT from the posterior pituitary into the general circulation to ensure that OT is delivered to these peripheral tissues in sufficient concentrations to induce smooth muscle contraction (30). Because of the extended nature of lactation and its dependence on OT release, this requires sustained production of large quantities of OT with associated heightened energy demands on the OT-producing neurons. Thus, it is plausible that during lactation, these neurons maximize glucose metabolism to meet the energy demands associated with heightened OT synthesis at the expense of monitoring glucose as a metabolic signal by increasing their reliance on hexokinase isoenzymes (hexokinases I, II, or III) that have higher affinities for glucose compared with GK (hexokinase IV) (27, 46). Our findings support this hypothesis, because although alloxan, a GK inhibitor, prevented the insulin plus glucose-induced increase in OT and VP release in male rats (51), it did not prevent this response in explants from lactating rats. In addition, the attenuation of GK dependence appears to be lactation specific rather than being common to conditions of chronic stimulation of hormone release, because the insulin plus glucose-induced increase in OT and VP release remained GK dependent in explants from 48-h dehydrated rats. The ability of insulin and insulin plus glucose, but not glucose alone, to induce increases in OT and VP release in explants from lactating rats suggests that insulin-mediated glucose uptake is required to meet the energy requirements associated with hormone release during lactation. Although other neurons rely on lactate provided through the “astrocyte-neuron lactate shuttle” to meet activity-related energy demands (36), this mechanism may be compromised in MCNs during lactation, because during lactation, astrocytes withdraw from OT MCNs (54, 55) to allow increased synapse formation for efficient and simultaneous activation of the OT MCN population (22, 57, 58). This may explain the reliance of MCNs on insulin-mediated glucose uptake to meet energy requirements during lactation.

The increased hormone release induced by insulin and insulin plus glucose is thought to reflect neuronal depolarization induced by inactivation of KATP in response to glycolytic ATP production. This is supported by earlier work demonstrating that the KATP channels, Kir6.1 and Kir6.2, are expressed in SON (11, 56), and our prior findings that the glucose increased intracellular calcium in SON neurons is dependent on KATP channels, and closure of KATP channels results in OT and VP release from HNS explants (51). Insulin is thought to mediate membrane insertion of GLUT4, thereby providing increased substrate for GK- or HK-mediated glycolysis. Insulin-responsive GLUT4 has been detected in SON (12, 13).

Our findings did not support our hypothesis that DIO results from a reduction in OT-mediated anorexia due to decreased glucose sensitivity and/or insulin resistance in the OT neurons. Although the DIO rats became obese (gained more weight and body fat) on the HFD and demonstrated characteristics of insulin resistance (e.g., had elevated plasma glucose, insulin, leptin, cholesterol, and triglycerides) compared with those on the NFD, OT release remained responsive to insulin and insulin plus glucose. Evidence for insulin resistance was limited to VP release with no increase in VP release in response to insulin alone in explants from DIO-HFD rats. Also in contrast to our hypothesis, it was the DR strain rather than the DIO strain that showed blunted OT and VP responses to insulin and insulin plus glucose. Thus, although there was a significant strain difference in the OT response, it was due to an absence of response in the DR-HFD explants rather than the DIO-HFD explants. Although these findings did not support our hypothesis, it is possible that after 6 wk on the HF diet, the DIO were approaching a new state of energy balance. Thus, evaluating their responses to glucose and insulin before the onset of obesity would be useful. Also, we may have missed differences in the in vivo sensitivity of DIO animals to increases in glucose and insulin by allowing all explants to equilibrate for 4 h to the same ex vivo concentration of glucose and insulin. Furthermore, it would be useful to assess this hypothesis in other animal models of obesity, because body weight regulation is complex, and obesity has a polygenetic basis. Genetic variation in the mechanisms regulating release of anorectic agents is substantiated by the reduced responsiveness of OT release to insulin and glucose in the DR strain, and others have reported that obesity in Zucker rats correlates with hypooxytocinemia, resulting from enhanced tissue oxytocinase activity and altered OT receptor expression (16, 17). Also, OT treatment produces weight loss in nonhuman primates with DIO as well as in humans (5, 29, 65).

Several aspects of the experimental design of these experiments warrant discussion. First, the changes in OT and VP release measured in the current experiments reflect hormonal OT and VP that is synthesized by magnocellular neurons (MCNs) in the supraoptic nucleus and released from the neural lobe. Although OT and VP are released from other sources in HNS explants (e.g., dendrites, suprachiasmatic nucleus), those sources account for less than one-tenth of that released from the neural lobe (19) and, thus, could not account for the responses observed in response to insulin and insulin plus glucose in these studies. Second, an important aspect of these studies is that the glucose and insulin concentrations tested are physiologically relevant. Hypothalamic glucose concentrations range from 0.5 mM in fasted rats to 5 mM in severely hyperglycemic rats, with 2.5 mM representing postingestive normoglycemia (50). Thus, the changes in glucose used in these experiments represented the physiological range from fasting to hyperglycemia. Insulin is transported into the brain by a saturable transport mechanism that is physiologically and regionally regulated, and hypothalamic levels are among the highest in the brain (3, 4). Thus, given the diffusion barriers present in in vitro preparations, it is plausible that the glucose and insulin concentrations used in these experiments resulted in exposure of SON neurons to concentrations they might encounter in vivo. Third, results from explants from lactating female rats were not compared with explants from nonlactating female rats, because the hormonal status of postpartum, lactating rats is not comparable to nonlactating females at any stage of the estrous cycle. Given the recognized impact of gonadal steroids on appetite regulation, it would be interesting to evaluate the effect of gonadal steroids on the metabolic sensor function of SON neurons in males and nonlactating females. However, this is beyond the scope of the current investigation. Also, the factors responsible for the altered metabolic profile observed during lactation go beyond gonadal steroids to include other hormones (e.g., relaxin, prolactin), as well as numerous appetite and metabolic signals (e.g., CCK, leptin, and ghrelin).

OT MCNs are uniquely situated for roles in nurturing the offspring and body weight regulation, because OT MCNs project to areas of the brain involved in motivated behaviors [e.g., amygdala and nucleus accumbens (28, 47)], such as hunger, attachment, and maternal behavior, as well as the neural lobe. This dual involvement of MCN OTs in peripheral and central release of OT is relevant to both body weight regulation and lactation. Lactation and nursing are simultaneously associated with providing life-sustaining nutrition and development of maternal attachment and other nurturing behaviors. Peripheral OT release is required for the milk let-down necessary for the young to obtain milk, while central OT release activates portions of the motivated behavior/reward circuitry involved in maternal behavior. Thus, the dual involvement of MCN OTs in the peripheral and central release of OT is crucial for survival of the offspring. Similar to lactation and maternal behavior, simultaneous control of peripheral and central release of OT from MCNs is advantageous in regulation of food intake and body weight, because the MCNs release OT into the peripheral circulation in response to anorectigenic stimuli (37), as well as into the motivated behavior and other circuitry involved in appetite regulation (21, 28). In addition, peripheral release of OT has been shown to induce anorexia via actions on central OT receptors (25), and OT has direct effects on adipose tissue metabolism, causing increased lipolysis and fatty acid oxidation (10).

Perspectives and Significance

Maternal OT is critical for survival of offspring in mammals through its action on the mammary glands to cause milk let-down and its central action to induce maternal behaviors consistent with survival of the young (e.g., nest building, swaddling, and cuddling). However, this role is not essential in males and nonlactating females. Thus, the system is available to integrate with other homeostatic responses, such as appetite and body weight regulation and reproduction. Therefore, the expression of mechanisms that allow the OT MCNs to function as metabolic sensors in males and nonlactating females appears to represent an efficient use of existing biology. However, since obesity is associated with reduced serum OT (9, 26, 44) and deficits in lactation occur in DIO animal models (62), it is likely that a combination of the central and peripheral actions of oxytocin contribute to the difficulties that obese mothers experience with breastfeeding (1, 2, 6, 45). Thus, while the MCN OT neurons are uniquely situated for promoting health and development of the offspring, as well as for participating in energy metabolism and body weight regulation, this dual role may compromise efficient lactation in obesity.

GRANTS

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health [NIH R21 HD-073428 (to C. D. Sladek), NIH PO1 HD-038129 (to P. S. MacLean), NIH P30 DK-48520 (to P. S. MacLean)], as well as a G. Edgar Folk Award from the American Physiological Society to C. D. Sladek.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.D.S., Z.S., and P.S.M. conception and design of research; C.D.S., W.S., and G.C.J. performed experiments; C.D.S., W.S., G.C.J., and P.S.M. analyzed data; C.D.S. and P.S.M. interpreted results of experiments; C.D.S. prepared figures; C.D.S. drafted manuscript; C.D.S., W.S., Z.S., G.C.J., and P.S.M. edited and revised manuscript; C.D.S., W.S., Z.S., G.C.J., and P.S.M. approved final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Amir LH, Donath S. A systematic review of maternal obesity and breastfeeding intention, initiation and duration. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 7: 9, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baker JL, Michaelsen KF, Sorensen TI, Rasmussen KM. High prepregnant body mass index is associated with early termination of full and any breastfeeding in Danish women. Am J Clin Nutr 86: 404–411, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Banks WA. The source of cerebral insulin. Eur J Pharmacol 490: 5–12, 2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baskin DG, Porte D Jr, Guest K, Dorsa DM. Regional concentrations of insulin in the rat brain. Endocrinology 112: 898–903, 1983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blevins JE, Graham JL, Morton GJ, Bales KL, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG, Havel PJ. Chronic oxytocin administration inhibits food intake, increases energy expenditure, and produces weight loss in fructose-fed obese rhesus monkeys. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 308: R431–R438, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Butte NF, Garza C, Stuff JE, Smith EO, Nichols BL. Effect of maternal diet and body composition on lactational performance. Am J Clin Nutr 39: 296–306, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Camerino C. Low sympathetic tone and obese phenotype in oxytocin-deficient mice. Obesity (Silver Spring) 17: 980–984, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Clegg DJ, Benoit SC, Reed JA, Woods SC, Dunn-Meynell A, Levin BE. Reduced anorexic effects of insulin in obesity-prone rats fed a moderate-fat diet. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R981–R986, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coiro V, Passeri M, Davoli C, d'Amato L, Gelmini G, Fagnoni F, Schianchi L, Bentivoglio M, Volpi R, Chiodera P. Oxytocin response to insulin-induced hypoglycemia in obese subjects before and after weight loss. J Endocrinol Invest 11: 125–128, 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Deblon N, Veyrat-Durebex C, Bourgoin L, Caillon A, Bussier AL, Petrosino S, Piscitelli F, Legros JJ, Geenen V, Foti M, Wahli W, Di Marzo V, Rohner-Jeanrenaud F. Mechanisms of the anti-obesity effects of oxytocin in diet-induced obese rats. PloS One 6: e25565, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dunn-Meynell AA, Rawson NE, Levin BE. Distribution and phenotype of neurons containing the ATP-sensitive K+ channel in rat brain. Brain Res 814: 41–54, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.El Messari S, Ait-Ikhlef A, Ambroise DH, Penicaud L, Arluison M. Expression of insulin-responsive glucose transporter GLUT4 mRNA in the rat brain and spinal cord: an in situ hybridization study. J Chem Neuroanat 24: 225–242, 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El Messari S, Leloup C, Quignon M, Brisorgueil MJ, Penicaud L, Arluison M. Immunocytochemical localization of the insulin-responsive glucose transporter 4 (Glut4) in the rat central nervous system. J Comp Neurol 399: 492–512, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Flanagan LM, Olson BR, Sved AF, Verbalis JG, Stricker EM. Gastric motility in conscious rats given oxytocin and an oxytocin antagonist centrally. Brain Res 578: 256–260, 1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fleming AS. Control of food intake in the lactating rat: role of suckling and hormones. Physiol Behav 17: 841–848, 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gajdosechova L, Krskova K, Olszanecki R, Zorad S. Differential regulation of oxytocin receptor in various adipose tissue depots and skeletal muscle types in obese Zucker rats. Horm Metab Res 47: 600–604, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gajdosechova L, Krskova K, Segarra AB, Spolcova A, Suski M, Olszanecki R, Zorad S. Hypooxytocinaemia in obese Zucker rats relates to oxytocin degradation in liver and adipose tissue. J Endocrinol 220: 333–343, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Giles ED, Jackman MR, Johnson GC, Schedin PJ, Houser JL, MacLean PS. Effect of the estrous cycle and surgical ovariectomy on energy balance, fuel utilization, and physical activity in lean and obese female rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 299: R1634–R1642, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gregg CM, Sladek CD. A compartmentalized, organ-cultured hypothalamo-neurohypophysial system for the study of vasopressin release. Neuroendocrinology 38: 397–402, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grewen KM, Davenport RE, Light KC. An investigation of plasma and salivary oxytocin responses in breast- and formula-feeding mothers of infants. Psychophysiology 47: 625–632, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Griffin GD, Ferri-Kolwicz SL, Reyes BA, Van Bockstaele EJ, Flanagan-Cato LM. Ovarian hormone-induced reorganization of oxytocin-labeled dendrites and synapses lateral to the hypothalamic ventromedial nucleus in female rats. J Comp Neurol 518: 4531–4545, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hatton GI, Wang YF. Neural mechanisms underlying the milk ejection burst and reflex. Prog Brain Res 170: 155–166, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Helmreich DL, Thiels E, Sved AF, Verbalis JG, Stricker EM. Effect of suckling on gastric motility in lactating rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 261: R38–R43, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hill JM, Lesniak MA, Pert CB, Roth J. Autoradiographic localization of insulin receptors in rat brain: prominence in olfactory and limbic areas. Neuroscience 17: 1127–1138, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ho JM, Anekonda VT, Thompson BW, Zhu M, Curry RW, Hwang BH, Morton GJ, Schwartz MW, Baskin DG, Appleyard SM, Blevins JE. Hindbrain oxytocin receptors contribute to the effects of circulating oxytocin on food intake in male rats. Endocrinology 155: 2845–2857, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoybye C, Barkeling B, Espelund U, Petersson M, Thoren M. Peptides associated with hyperphagia in adults with Prader-Willi syndrome before and during GH treatment. Growth Horm IGF Res 13: 322–327, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iynedjian PB. Molecular physiology of mammalian glucokinase. Cell Mol Life Sci 66: 27–42, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knobloch HS, Charlet A, Hoffmann LC, Eliava M, Khrulev S, Cetin AH, Osten P, Schwarz MK, Seeburg PH, Stoop R, Grinevich V. Evoked axonal oxytocin release in the central amygdala attenuates fear response. Neuron 73: 553–566, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lawson EA, Marengi DA, DeSanti RL, Holmes TM, Schoenfeld DA, Tolley CJ. Oxytocin reduces caloric intake in men. Obesity (Silver Spring) 23: 950–956, 2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leng G, Brown D. The origins and significance of pulsatility in hormone secretion from the pituitary. J Neuroendocrinol 9: 493–513, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Levin BE, Dunn-Meynell AA, Balkan B, Keesey RE. Selective breeding for diet-induced obesity and resistance in Sprague-Dawley rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 273: R725–R730, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Levin BE, Magnan C, Dunn-Meynell A, Le Foll C. Metabolic sensing and the brain: who, what, where, and how? Endocrinology 152: 2552–2557, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Levin BE, Magnan C, Migrenne S, Chua SC Jr., and Dunn-Meynell AA. F-DIO obesity-prone rat is insulin resistant before obesity onset. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 289: R704–R711, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.MacLean PS, Higgins JA, Jackman MR, Johnson GC, Fleming-Elder BK, Wyatt HR, Melanson EL, Hill JO. Peripheral metabolic responses to prolonged weight reduction that promote rapid, efficient regain in obesity-prone rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 290: R1577–R1588, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Madsen AN, Hansen G, Paulsen SJ, Lykkegaard K, Tang-Christensen M, Hansen HS, Levin BE, Larsen PJ, Knudsen LB, Fosgerau K, Vrang N. Long-term characterization of the diet-induced obese and diet-resistant rat model: a polygenetic rat model mimicking the human obesity syndrome. J Endocrinol 206: 287–296, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Magistretti PJ. Neuron-glia metabolic coupling and plasticity. J Exp Biol 209: 2304–2311, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McCann MJ, Verbalis JG, Stricker EM. LiCl and CCK inhibit gastric emptying and feeding and stimulate OT secretion in rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 256: R463–R468, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Morris EM, Jackman MR, Johnson GC, Liu TW, Lopez JL, Kearney ML, Fletcher JA, Meers GM, Koch LG, Britton SL, Rector RS, Ibdah JA, MacLean PS, Thyfault JP. Intrinsic aerobic capacity impacts susceptibility to acute high-fat diet-induced hepatic steatosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 307: E355–E364, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nishimori K, Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Kasahara Y, Young LJ, Kawamata M. New aspects of oxytocin receptor function revealed by knockout mice: sociosexual behaviour and control of energy balance. Progr Brain Res 170: 79–90, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Olson BR, Drutarosky MD, Chow MS, Hruby VJ, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Oxytocin and an oxytocin agonist administered centrally decrease food intake in rats. Peptides 12: 113–118, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Olson BR, Drutarosky MD, Stricker EM, Verbalis JG. Brain oxytocin receptor antagonism blunts the effects of anorexigenic treatments in rats: Evidence for central oxytocin inhibition of food intake. Endocrinology 129: 785–791, 1991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ott V, Finlayson G, Lehnert H, Heitmann B, Heinrichs M, Born J, Hallschmid M. Oxytocin reduces reward-driven food intake in humans. Diabetes 62: 3418–3425, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Paulsen SJ, Jelsing J, Madsen AN, Hansen G, Lykkegaard K, Larsen LK, Larsen PJ, Levin BE, Vrang N. Characterization of β-cell mass and insulin resistance in diet-induced obese and diet-resistant rats. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18: 266–273, 2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Qian W, Zhu T, Tang B, Yu S, Hu H, Sun W, Pan R, Wang J, Wang D, Yang L, Mao C, Zhou L, Yuan G. Decreased circulating levels of oxytocin in obesity and newly diagnosed type 2 diabetic patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 99: 4683–4689, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rasmussen KM. Association of maternal obesity before conception with poor lactation performance. Ann Rev Nutrit 27: 103–121, 2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Roncero I, Alvarez E, Vazquez P, Blazquez E. Functional glucokinase isoforms are expressed in rat brain. J Neurochem 74: 1848–1857, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ross HE, Cole CD, Smith Y, Neumann ID, Landgraf R, Murphy AZ, Young LJ. Characterization of the oxytocin system regulating affiliative behavior in female prairie voles. Neuroscience 162: 892–903, 2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russell JA, Leng G. Sex, parturition, and motherhood without oxytocin? J Endocrinol 157: 343–359, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Russell JA, Leng G, Douglas AJ. The magnocellular oxytocin system, the fount of maternity: adaptations in pregnancy. Front Neuroendocrinol 24: 27–61, 2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Silver IA, Erecinska M. Extracellular glucose concentration in mammalian brain: continuous monitoring of changes during increased neuronal activity and upon limitation in oxygen supply in normo-, hypo-, and hyperglycemic animals. J Neurosci 14: 5068–5076, 1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Song Z, Levin BE, Stevens W, Sladek CD. Supraoptic oxytocin and vasopressin neurons function as glucose and metabolic sensors. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 306: R447–R456, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takayanagi Y, Kasahara Y, Onaka T, Takahashi N, Kawada T, Nishimori K. Oxytocin receptor-deficient mice developed late-onset obesity. Neuroreport 19: 951–955, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, Nishimori K. Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 16,096–16,101, 2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Theodosis DT, Chapman DB, Montagnese C, Poulain DA, Morris JF. Structural plasticity in the hypothalamic supraoptic nucleus at lactation affects oxytocin-, but not vasopressin-secreting neurones. Neuroscience 17: 661–678, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Theodosis DT, Poulain DA. Evidence for structural plasticity in the supraoptic nucleus of the rat hypothalamus in relation to gestation and lactation. Neuroscience 11: 183–194, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Thomzig A, Laube G, Pruss H, Veh RW. Pore-forming subunits of K-ATP channels, Kir6.1 and Kir62, display prominent differences in regional and cellular distribution in the rat brain. J Comp Neurol 484: 313–330, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Tweedle CD, Hatton GI. Synapse formation and disappearance in adult rat supraoptic nucleus during different hydration states. Brain Res 309: 373–376, 1984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tweedle CD, Smithson KG, Hatton GI. Rapid synaptic changes and bundling in the supraoptic dendritic zone of the perfused rat brain. Exp Neurol 124: 200–207, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Unger J, McNeill TH, Moxley IIIRT, White M, Moss A, Livingston JN. Distribution of insulin receptor-like immunoreactivity in the rat forebrain. Neuroscience 31: 143–157, 1989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Verbalis JG, Blackburn RE, Olson BR, Stricker EM. Central oxytocin inhibition of food and salt ingestion: A mechanism for intake regulation of solute homeostasis. Regul Pept 45: 149–154, 1993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Verbalis JG, McCann MJ, McHale CM, Stricker EM. Oxytocin secretion in response to cholecystokinin and food: differentiation of nausea from satiety. Science 232: 1417–1419, 1986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Wahlig JL, Bales ES, Jackman MR, Johnson GC, McManaman JL, Maclean PS. Impact of high-fat diet and obesity on energy balance and fuel utilization during the metabolic challenge of lactation. Obesity (Silver Spring) 20: 65–75, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yagil C, Sladek CD. Osmotic regulation of vasopressin and oxytocin release is rate sensitive in hypothalamoneurohypophysial explants. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 258: R492–R500, 1990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yokoyama Y, Ueda T, Irahara M, Aono T. Releases of oxytocin and prolactin during breast massage and suckling in puerperal women. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 53: 17–20, 1994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zhang H, Wu C, Chen Q, Chen X, Xu Z, Wu J, Cai D. Treatment of obesity and diabetes using oxytocin or analogs in patients and mouse models. PloS One 8: e61477, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]