Abstract

Monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapeutics are revolutionizing cancer treatment; however, not all tumors respond, and agent optimization is essential to improve outcome. It has become clear over recent years that isotype choice is vital to therapeutic success with agents that work through different mechanisms, direct tumor targeting, agonistic receptor engagement, or receptor-ligand blockade, having contrasting requirements. Here we summarize how isotype dictates mAb activity and discuss ways in which this information can be used for the development of enhanced therapeutics.

Introduction

Monoclonal antibody (mAb) drugs have transformed cancer therapy over the last 3 decades,1 with a plethora of recent examples where established and previously untreatable tumors have been eradicated.2 Unmodified, “naked” mAbs can be harnessed to deliver therapy through a number of mechanisms including direct targeting of tumor to elicit immune cell-mediated clearance; agonistic receptor engagement to stimulate tumor immunity or effect tumor cell apoptosis; and blocking of receptor:ligand interactions important for tumor survival or suppression of antitumor immunity. Target specificity, imparted by the mAb variable domains, is clearly of paramount importance in each of these scenarios. However, it is also apparent that the mAb constant region plays a crucial role, much of which is mediated through interaction of the mAb Fc with Fcγ receptors (FcγRs). In this review, we describe how mAb isotype, which dictates FcγR binding specificity and other structural characteristics, critically influences mAb activity and discuss how this knowledge can be used to improve therapeutic efficacy.

Isotype and activatory FcγRs

Direct targeting mAbs

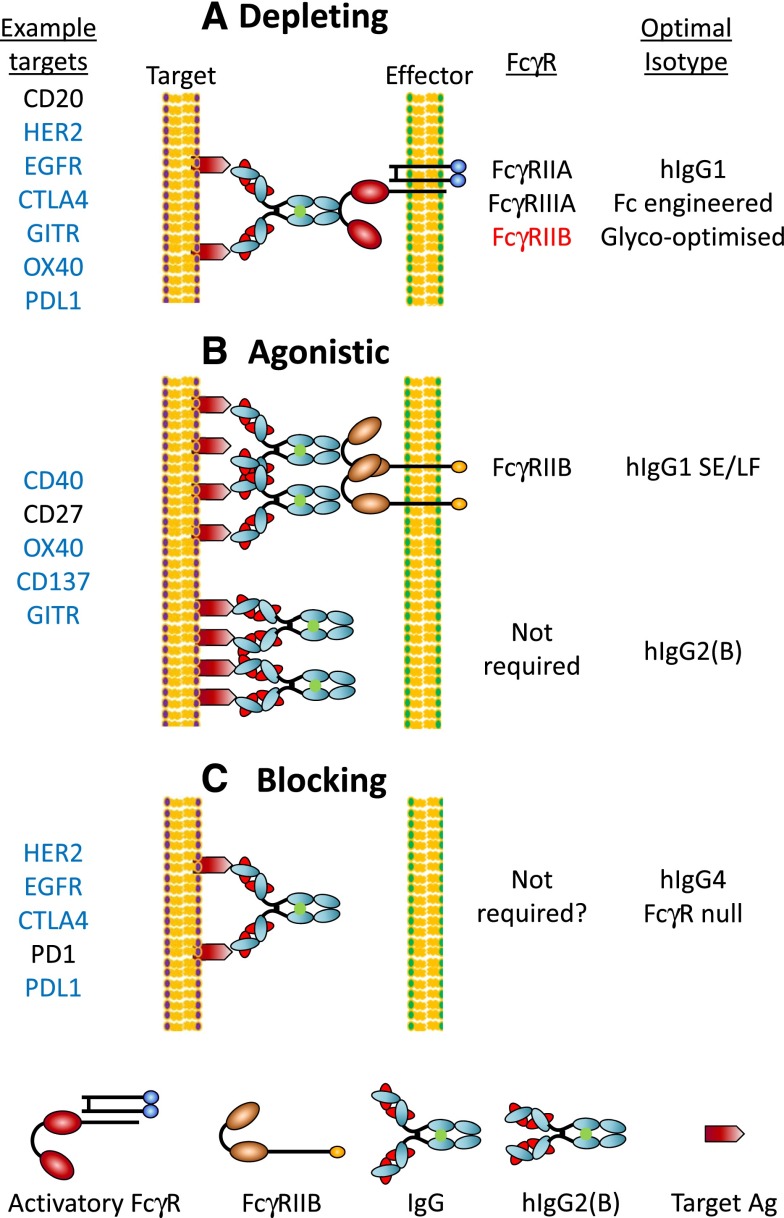

The first demonstrations of the importance of isotype selection in therapeutic activity was in studies with mAbs that directly engage their tumor cell targets, such as clinical rituximab (anti-CD20) and trastuzumab (anti-HER2). Early findings observed the impact of isotype on mAb therapy where particular mouse and human isotypes were seen to offer protection in xenograft models, and efficacy was dependent on FcγR and effector cells.3,4 One of the principal killing mechanisms of these agents is recruitment of activatory FcγR-expressing immune effectors that mediate target cell deletion (Figure 1A). In seminal mouse studies in 2000, Clynes et al5 demonstrated that rituximab and trastuzumab required functional activatory FcγR expression for therapeutic activity, whereas, in contrast, the presence of the inhibitory FcγRIIB reduced mAb efficacy.5 Later, detailed syngeneic studies were carried out where it was observed that mouse immunoglobulin (Ig)G2a MAbs that engage activatory FcγR with relatively high affinity6 provided effective therapy, whereas isotypes with lower affinities were much less effective.7 Through these studies, the paradigm was established that a preference for activatory vs inhibitory FcγR engagement (high activatory:inhibitory [A:I] FcγR binding ratio) was critical for therapeutic mAb activity.6,8 Since these initial observations, many studies using a variety of agents including rituximab, trastuzumab, and cetuximab (anti-EGFR), have demonstrated an absolute requirement in vivo for activatory FcγR interactions to facilitate depletion of both normal and malignant target cells.7,9-12 Similar to mouse IgG2a, the human IgG1 isotype selected for clinical reagents has a high A:I FcγR binding ratio.

Figure 1.

Role of isotype and FcγR interactions in therapeutic mAb function. Multiple mechanisms can mediate mAb therapeutic efficacy, influenced differentially by mAb isotype and FcγR interactions. (A) Direct targeting (depleting) mAbs mediate clearance of cells expressing their Ag target by recruitment of activatory FcγR (FcγRIIA or FcγRIIIA)-expressing cytotoxic immune effectors. Interaction of the mAb Fc with inhibitory FcγRIIB can prevent this process. Thus, hIgG1 and Fc- or glyco-engineered forms of mAb with a high activatory:inhibitory FcγR binding ratio are optimal. (B) Agonistic mAbs are designed to stimulate signaling through their receptor targets, typically TNFR, through receptor clustering. This can be achieved either by crosslinking of the mAb Fc by FcγRIIB on adjacent cells enhanced by the SE/LF mutation in hIgG1 (top) or through the unique configuration of human IgG2(B) (bottom; see also Figure 2). (C) Blocking mAbs are designed to block receptor-ligand interactions mediating immune suppression (eg, CTLA4, PD-1) or required for tumor cell growth/survival (eg, HER2, epidermal growth factor receptor [EGFR]). Recent preclinical data suggest that optimal activity, at least for PD1 mAbs, is achieved in the absence of FcγR engagement.37 Isotypes with minimal FcγR binding, such as hIgG4 or “FcγR null” mAbs engineered to prevent FcγR engagement, may therefore be optimal. For each mechanism, example targets are listed on the left, with those in blue demonstrated to engage multiple mechanisms in preclinical models. The roles of FcγR (black, positive role; red, negative role) and optimal isotypes are listed on the right and are detailed in the text.

In preclinical mouse models, circulating monocytes7,13,14 and tissue macrophages7,9,11,12,15-18 have been demonstrated to be the primary effector cells involved in mAb-induced cell killing, although debate still exists regarding which has the dominant role, and this may vary dependent on target cell and location. Roles for natural killer (NK) cells19 and neutrophils20,21 have been demonstrated in some models; however, they have not generally been found to be important for efficacy. In humans, the effector populations are less clear. In vitro experiments with blood-borne effectors suggest NK cells play a predominant role.22 However, these assays do not necessarily reflect the situation in tissues, especially as the absence of macrophages in blood is likely to underestimate their role. The association between functionally relevant FcγR polymorphisms and clinical response to therapy underscores the critical role of FcγR in mAb activity in humans and also supports a role for macrophages. Cartron et al23 first demonstrated that inheritance of an F to V amino acid change at position 158 in FcγRIIIA, which increases affinity for human IgG1, a receptor expressed on macrophages and NK cells, was associated with enhanced responses to rituximab in follicular lymphoma patients. Subsequently, >40 similar investigations with a range of mAbs in a variety of hematologic and solid cancer settings have been reported,24,25 and although findings are mixed and sometimes conflicting, many do support a role of FcγR in clinical activity. Negative findings in some studies may be explained by small patient numbers, combined treatment with chemotherapy, or the presence of additional mAb mechanisms (eg, direct inhibitory or cytotoxic effects) that confound the results.

The importance of a high A:I FcγR binding ratio has stimulated considerable efforts to optimize FcγR interaction, particularly with FcγRIIIA, through amino acid substitution or glycoengineering of mAb Fc.16,26-28 The most clinically advanced agent is the glycoengineered anti-CD20 obinutuzumab (GA101),29 which, in combination with chlorambucil, was recently shown to nearly double progression-free survival in chronic lymphocytic leukemia patients compared with rituximab.30 The ability to augment mAb activity by increasing A:I ratio while maintaining FcRn association and biological half-life31-33 is likely to be limited, however. Moreover, there are potential negative impacts such as enhanced antigen shaving/trogocytosis,34 an FcγR-dependent process whereby mAb/Ag complexes are removed from the target cells by effectors, thus leaving the target cells invisible to effector mechanisms. In addition to these approaches, other strategies may be possible to enhance efficacy such as that recently suggested by Kinder et al,35 where specific manipulation of FcγRI engagement was used to modulate effector cell cytokine production to allow manipulation of the tumor microenvironment without effects on direct cell killing. In addition, other classes of immunoglobulin molecules, such as IgA and IgE, have been shown to mediate therapeutic effects through engagement of Fcα and Fcε receptors on immune effector cells, respectively.36,37 Future studies will be required to determine the relative efficacy of these agents compared with Fc engineered IgG.

Immunomodulatory mAbs

An unexpected role for activatory FcγR was also suggested in recent studies of immunomodulatory mAbs that provide therapy by stimulating antitumor immunity. Immunomodulatory mAbs are designed to either block key inhibitory pathways suppressing effector T cells (checkpoint blockers) or to agonistically engage costimulatory immune receptors (immunostimulatory). Recent preclinical data suggest that checkpoint blocking anti-CTLA4 and anti-PDL1 and immunostimulatory anti-GITR and anti-OX40 mAbs actually deliver much of their therapeutic effect through deletion of intratumoural T regulatory (Treg) cells, thus releasing CD8 T cell-mediated antitumoral immunity.38-42 In this context, the mAb function as classical deletors, much as the direct targeting mAbs discussed above, requiring activatory FcγR engagement on effector cells in the tumor microenvironment (Figure 1A). In the case of CTLA-4, these were FcγRIV-expressing intratumoral macrophages.41

There is some supporting evidence that similar mechanisms may operate in human patients. Ipilimumab, a human IgG1 anti-CTLA4, was recently shown to mediate FcγR-mediated cytotoxicity of human Tregs ex vivo.43 In addition, in a small clinical study, melanoma patients responding to ipilimumab had significantly higher baseline frequency of nonclassical monocytes and more activated tumor-associated macrophages expressing FcγRIII, which correlated with lower intratumoral Treg numbers after therapy, suggesting Treg deletion may also occur in patients.43 In contrast, other checkpoint blockers, such as nivolumab and pembrolizumab (both anti-PD1), are IgG4 isotypes selected for minimal FcγR interactions. Recent preclinical data,42 as well as the association of their efficacy with PDL-1 expression in at least some studies,44 suggest that these mAbs may work as true blockers. It is important to note, however, that even the nonfunctional isotypes IgG2 and IgG4 are able to bind human FcγR as immune complexes,45,46 and their activity can be influenced by FcγR as recently demonstrated for the IgG4 TGN1412.47 Thus, further work is needed to fully elucidate the in vivo mechanisms of action of these mAbs.

Vaccine effect

A further potential role for activatory FcγR in therapeutic anticancer mAb activity is a described vaccine effect with direct targeting mAbs. It has been appreciated for some time that passively administered neutralizing antiviral mAbs can potentiate viral CD8 T-cell immunity.48 Two recent studies have demonstrated a similar vaccine effect in mice challenged with human CD20-expessing tumor cells treated with anti-CD20 mAbs,49,50 with induced immunity dependent on interaction of the CD20 mAb with activatory FcγR on dendritic cells.50 It will be important to confirm this effect in models using endogenously expressed (and thus less immunogenic) target antigens; however, these studies highlight the multiple and sometimes unexpected effects that activatory FcγR interaction can have on therapeutic mAb activity.

Role for inhibitory FcγRIIB

Both positive and negative roles for the inhibitory receptor, FcγRIIB, have also been established with therapeutic mAbs. Early studies demonstrated that the presence of FcγRIIB was detrimental to the therapeutic activity of direct targeting agents, such as rituximab.5 Subsequent studies showed that the FcγRIIB interaction can inhibit target cell killing through competition for Fc engagement or by promoting antigenic modulation10 where opsonizing mAb Fc interacts in cis with FcγRIIB on target B cells, leading to enhanced internalization of mAb/Ag complexes. This process compromises mAb efficacy as it both consumes the mAb and downregulates the target so that cells become invisible to effector mechanisms.51-53

In contrast, FcγRIIB engagement has been shown to be requisite for the activity of agonistic mAbs. These agents stimulate signaling through their target receptors, typically members of the tumor necrosis factor receptor (TNFR) superfamily. As cancer therapeutics, they are designed to enhance tumor immunity by engaging costimulatory receptors such as CD40, 4-1BB, or OX40, on APC or T-effector cells, or to promote apoptosis by stimulating death receptors (DRs) such as DR4, DR5, or Fas (CD95) on cancer cells.54 In contrast to direct targeting agents, the agonistic activity of these mAbs is dependent on their ability to engage inhibitory FcγRIIB,55-59 and mAbs with high A:I ratios (eg, mouse IgG2a, human IgG1) are largely inactive in preclinical models, whereas those with low A:I ratios (eg, mouse IgG1 and rat IgG2a) are highly agonistic.55-60 Signaling through FcγRIIB is not required to confer activity; rather, it provides a crosslinking scaffold for the mAbs to facilitate TNFR clustering and activation57,61-63 (Figure 1B). Activatory FcγR can also mediate crosslinking in vitro57 or in vivo when sufficiently expressed at the target location58,63; thus, the predominant role of FcγRIIB in vivo may, in part, reflect its bioavailability.

The dependence of agonistic mAb on FcγRIIB presents a challenge when developing therapeutics, as human IgGs have low affinity for this receptor.45 Fc engineering of human IgG1 to enhance FcγRIIB affinity increases therapeutic activity of CD40 and DR5 mAbs in human FcγRIIB transgenic mice.64,65 A potential downside to this approach, however, is the resulting dependence on local FcγRIIB expression for activity.

FcγR-independent effects

Not all therapeutic effects require Fc receptor interactions. For example, a recent study from Dahan et al42 demonstrated greater efficacy with blocking anti-PD1 mAbs engineered to prevent FcγR engagement (Figure 1C). Moreover, human IgG2 agonistic anti-TNFR mAbs also do not require FcγR interaction for agonistic activity60 (Figure 1B). ChiLob 7/4, a CD40 mAb that has recently completed a phase 1 clinical trial,66 is agonistic in human CD40 transgenic mice as IgG2 in the absence of FcγR expression and even as a F(ab′)2 fragment.60 FcγR-independent activity has also been demonstrated for another IgG2 CD40 mAb in a clinical trial: CP870-893.67

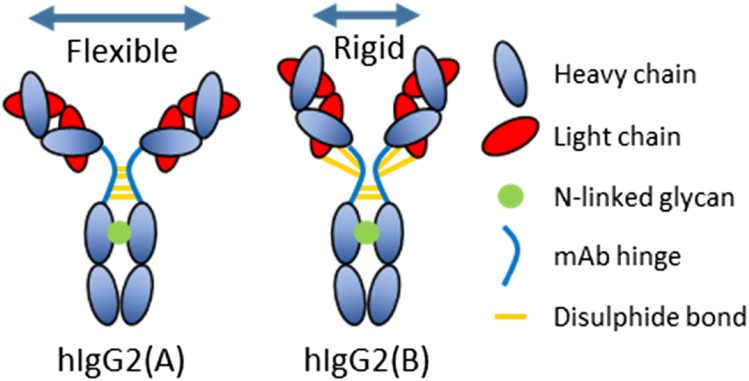

The key to IgG2 agonistic activity lies in the unique configuration of its hinge region,60 which can adopt alternative conformations through disulphide rearrangement.68-70 IgG2 is believed to be synthesized with all 4 heavy chain (HC) hinge cysteines involved in parallel inter-HC disulphide bonds, a conformation designated as IgG2(A). Over time, these bonds rearrange, and a portion of the mAb eventually achieves a more compact conformation, IgG2(B), in which both Fab arms are disulphide linked to the hinge (Figure 2). Using single cys-ser substitutions to “lock” IgG2 into IgG2(A)-like or IgG2(B)-like conformations,69,71 ChiLob 7/4 IgG2B was found to be highly agonistic, whereas IgG2A was nonagonistic or even antagonistic.60 The more compact conformation of IgG2B may promote close packing of TNFR molecules, already present as preformed dimers or trimers,72,73 initiating signaling. Thus, fine differences in structure induced by single amino acid changes can have profound effects on mAb activity. A key aspect of future work will be to determine whether FcγR-dependent vs -independent mechanisms of agonistic activity are associated with different levels of toxicity and therapeutic efficacy.

Figure 2.

Disulphide shuffling in human IgG2 produces alternative hinge configurations. Disulphide bonds in the hinge and CH1 domains of hIgG2 can rearrange. hIgG2 is thought to be synthesized in its IgG2(A) format where all 4 hinge cysteines are involved in parallel inter-heavy chain disulphide bonds (left). Over time, as it circulates in the blood, these bonds can rearrange and the protein passes through a series of intermediates with a portion achieving a conformation [IgG2(B)] in which both Fab arms are disulphide linked to the hinge. IgG2(A) is thought to have a more open and flexible conformation than the more compact and rigid IgG2(B) (see main text for details and references).

Engaging multiple mechanisms

The precise mechanisms through which a particular mAb provides therapy are not necessarily clear. CD40 mAbs, for example, can promote tumor rejection through immune stimulation; however, they can also act as direct targeting agents to mediate lymphoma cell depletion or apoptosis or even as antagonistic agents to reduce inflammation.74 Similarly, rituximab (anti-CD20) and trastuzumab (anti-HER2) may have therapeutic benefit by promoting target cell death or by blocking receptor function, respectively.75,76 The optimal FcγR interactions and therefore isotype for each of these mechanisms are likely to differ. In some cases, it may be advantageous to combine different functions. A good example is the bi-functional nature of immunomodulatory mAbs, which potentially deliver immune agonism or blockade via antigen engagement while simultaneously interacting with FcγR-expressing cells to promote target cell deletion. The latter may be advantageous (deletion of Tregs) or deleterious (deletion of effectors). Whether these apparently competitive functions can be combined to good effect in the same mAb, eg, IgG1/2 chimeras that contain an IgG2 hinge/CH1 with an FcγR binding IgG1 Fc,60 remains to be seen. Combinations of agents can also be beneficial, such as the use of agonistic mAb to potentiate the effects of direct targeting agents, through activation of immune effector cells involved in target cell clearance.19 How potential competition for FcγR binding may influence the dynamics of these relationships is unclear. However, defining the role of FcγR is crucial to better understand mechanisms of action and to define effective combination strategies.

In summary, appropriate isotype selection is crucial for therapeutic mAb activity not only because of its influence on FcγR interactions but also through subtle effects on mAb structure that, in the case of agonistic mAbs, can have profound effects on function. Intricate knowledge of the mechanisms by which mAbs deliver therapy will lead us toward the goal of designing agents capable of delivering curative responses in the majority of cancer patients.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from Cancer Research UK and Bloodwise and an EU Framework HEALTH-2013-INNOVATION grant.

Authorship

Contribution: S.A.B. and A.L.W. wrote the manuscript; and M.J.G. edited the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Correspondence: Ann L. White, Antibody and Vaccine Group, Cancer Sciences Unit MP88, General Hospital, Tremona Rd, Southampton SO16 8AA, United Kingdom; e-mail: a.l.white@soton.ac.uk.

References

- 1.Sliwkowski MX, Mellman I. Antibody therapeutics in cancer. Science. 2013;341(6151):1192–1198. doi: 10.1126/science.1241145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Postow MA, Callahan MK, Wolchok JD. Immune Checkpoint Blockade in Cancer Therapy. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(17):1974–1982. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.4358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Herlyn D, Koprowski H. IgG2a monoclonal antibodies inhibit human tumor growth through interaction with effector cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79(15):4761–4765. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.15.4761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Isaacs JD, Greenwood J, Waldmann H. Therapy with monoclonal antibodies. II. The contribution of Fc gamma receptor binding and the influence of C(H)1 and C(H)3 domains on in vivo effector function. J Immunol. 1998;161(8):3862–3869. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Clynes RA, Towers TL, Presta LG, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fc receptors modulate in vivo cytotoxicity against tumor targets. Nat Med. 2000;6(4):443–446. doi: 10.1038/74704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nimmerjahn F, Bruhns P, Horiuchi K, Ravetch JV. FcgammaRIV: a novel FcR with distinct IgG subclass specificity. Immunity. 2005;23(1):41–51. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Uchida J, Hamaguchi Y, Oliver JA, et al. The innate mononuclear phagocyte network depletes B lymphocytes through Fc receptor-dependent mechanisms during anti-CD20 antibody immunotherapy. J Exp Med. 2004;199(12):1659–1669. doi: 10.1084/jem.20040119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nimmerjahn F, Ravetch JV. Divergent immunoglobulin g subclass activity through selective Fc receptor binding. Science. 2005;310(5753):1510–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.1118948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Minard-Colin V, Xiu Y, Poe JC, et al. Lymphoma depletion during CD20 immunotherapy in mice is mediated by macrophage FcgammaRI, FcgammaRIII, and FcgammaRIV. Blood. 2008;112(4):1205–1213. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-135160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beers SA, French RR, Chan HT, et al. Antigenic modulation limits the efficacy of anti-CD20 antibodies: implications for antibody selection. Blood. 2010;115(25):5191–5201. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-01-263533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Butchar JP, Mehta P, Justiniano SE, et al. Reciprocal regulation of activating and inhibitory Fcgamma receptors by TLR7/8 activation: implications for tumor immunotherapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16(7):2065–2075. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shi Y, Fan X, Deng H, et al. Trastuzumab triggers phagocytic killing of high HER2 cancer cells in vitro and in vivo by interaction with Fcγ receptors on macrophages. J Immunol. 2015;194(9):4379–4386. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1402891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biburger M, Aschermann S, Schwab I, et al. Monocyte subsets responsible for immunoglobulin G-dependent effector functions in vivo. Immunity. 2011;35(6):932–944. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schwab I, Lux A, Nimmerjahn F. Pathways Responsible for Human Autoantibody and Therapeutic Intravenous IgG Activity in Humanized Mice. Cell Reports. 2015;13(3):610–620. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2015.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gong Q, Ou Q, Ye S, et al. Importance of cellular microenvironment and circulatory dynamics in B cell immunotherapy. J Immunol. 2005;174(2):817–826. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.2.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Montalvao F, Garcia Z, Celli S, et al. The mechanism of anti-CD20-mediated B cell depletion revealed by intravital imaging. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5098–5103. doi: 10.1172/JCI70972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gül N, Babes L, Siegmund K, et al. Macrophages eliminate circulating tumor cells after monoclonal antibody therapy. J Clin Invest. 2014;124(2):812–823. doi: 10.1172/JCI66776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tipton TR, Roghanian A, Oldham RJ, et al. Antigenic modulation limits the effector cell mechanisms employed by type I anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies. Blood. 2015;125(12):1901–1909. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-07-588376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kohrt HE, Houot R, Goldstein MJ, et al. CD137 stimulation enhances the antilymphoma activity of anti-CD20 antibodies. Blood. 2011;117(8):2423–2432. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-08-301945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 20.Albanesi M, Mancardi DA, Jönsson F, et al. Neutrophils mediate antibody-induced antitumor effects in mice. Blood. 2013;122(18):3160–3164. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-497446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hernandez-Ilizaliturri FJ, Jupudy V, Ostberg J, et al. Neutrophils contribute to the biological antitumor activity of rituximab in a non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma severe combined immunodeficiency mouse model. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9(16 Pt 1):5866–5873. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Golay J, Manganini M, Facchinetti V, et al. Rituximab-mediated antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity against neoplastic B cells is stimulated strongly by interleukin-2. Haematologica. 2003;88(9):1002–1012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cartron G, Dacheux L, Salles G, et al. Therapeutic activity of humanized anti-CD20 monoclonal antibody and polymorphism in IgG Fc receptor FcgammaRIIIa gene. Blood. 2002;99(3):754–758. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.3.754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dahal LN, Roghanian A, Beers SA, Cragg MS. FcγR requirements leading to successful immunotherapy. Immunol Rev. 2015;268(1):104–122. doi: 10.1111/imr.12342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hargreaves CE, Rose-Zerilli MJJ, Machado LR, et al. Fcγ receptors: genetic variation, function, and disease. Immunol Rev. 2015;268(1):6–24. doi: 10.1111/imr.12341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Redman JM, Hill EM, AlDeghaither D, Weiner LM. Mechanisms of action of therapeutic antibodies for cancer. Mol Immunol. 2015;67(2 Pt A):28–45. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2015.04.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Umana P, Moessner E, Bruenker P, et al. Novel 3rd generation humanized type II CD20 antibody with glycoengineered Fc and modified elbow hinge for enhanced ADCC and superior apoptosis induction. ASH Annu Mtg Abstr. 2006;108(11):229. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Herter S, Birk MC, Klein C, Gerdes C, Umana P, Bacac M. Glycoengineering of therapeutic antibodies enhances monocyte/macrophage-mediated phagocytosis and cytotoxicity. J Immunol. 2014;192(5):2252–2260. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1301249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mössner E, Brünker P, Moser S, et al. Increasing the efficacy of CD20 antibody therapy through the engineering of a new type II anti-CD20 antibody with enhanced direct and immune effector cell-mediated B-cell cytotoxicity. Blood. 2010;115(22):4393–4402. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-06-225979. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Goede V, Fischer K, Engelke A, et al. Obinutuzumab as frontline treatment of chronic lymphocytic leukemia: updated results of the CLL11 study. Leukemia. 2015;29(7):1602–1604. doi: 10.1038/leu.2015.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Presta LG, Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, Meng YG. Engineering therapeutic antibodies for improved function. Biochem Soc Trans. 2002;30(4):487–490. doi: 10.1042/bst0300487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shields RL, Lai J, Keck R, et al. Lack of fucose on human IgG1 N-linked oligosaccharide improves binding to human Fcgamma RIII and antibody-dependent cellular toxicity. J Biol Chem. 2002;277(30):26733–26740. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M202069200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shields RL, Namenuk AK, Hong K, et al. High resolution mapping of the binding site on human IgG1 for Fc gamma RI, Fc gamma RII, Fc gamma RIII, and FcRn and design of IgG1 variants with improved binding to the Fc gamma R. J Biol Chem. 2001;276(9):6591–6604. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009483200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Beum PV, Kennedy AD, Williams ME, Lindorfer MA, Taylor RP. The shaving reaction: rituximab/CD20 complexes are removed from mantle cell lymphoma and chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells by THP-1 monocytes. J Immunol. 2006;176(4):2600–2609. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.4.2600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinder M, Greenplate AR, Strohl WR, Jordan RE, Brezski RJ. An Fc engineering approach that modulates antibody-dependent cytokine release without altering cell-killing functions. MAbs. 2015;7(3):494–504. doi: 10.1080/19420862.2015.1022692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Boross P, Lohse S, Nederend M, et al. IgA EGFR antibodies mediate tumour killing in vivo. EMBO Mol Med. 2013;5(8):1213–1226. doi: 10.1002/emmm.201201929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Josephs DH, Spicer JF, Karagiannis P, Gould HJ, Karagiannis SN. IgE immunotherapy: a novel concept with promise for the treatment of cancer. MAbs. 2014;6(1):54–72. doi: 10.4161/mabs.27029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bulliard Y, Jolicoeur R, Windman M, et al. Activating Fc γ receptors contribute to the antitumor activities of immunoregulatory receptor-targeting antibodies. J Exp Med. 2013;210(9):1685–1693. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bulliard Y, Jolicoeur R, Zhang J, Dranoff G, Wilson NS, Brogdon JL. OX40 engagement depletes intratumoral Tregs via activating FcγRs, leading to antitumor efficacy. Immunol Cell Biol. 2014;92(6):475–480. doi: 10.1038/icb.2014.26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Selby MJ, Engelhardt JJ, Quigley M, et al. Anti-CTLA-4 antibodies of IgG2a isotype enhance antitumor activity through reduction of intratumoral regulatory T cells. Cancer Immunol Res. 2013;1(1):32–42. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Simpson TR, Li F, Montalvo-Ortiz W, et al. Fc-dependent depletion of tumor-infiltrating regulatory T cells co-defines the efficacy of anti-CTLA-4 therapy against melanoma. J Exp Med. 2013;210(9):1695–1710. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Dahan R, Sega E, Engelhardt J, Selby M, Korman AJ, Ravetch JV. FcγRs Modulate the Anti-tumor Activity of Antibodies Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 Axis. Cancer Cell. 2015;28(3):285–295. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Romano E, Kusio-Kobialka M, Foukas PG, et al. Ipilimumab-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxicity of regulatory T cells ex vivo by nonclassical monocytes in melanoma patients. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2015;112(19):6140–6145. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1417320112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bruhns P, Iannascoli B, England P, et al. Specificity and affinity of human Fcgamma receptors and their polymorphic variants for human IgG subclasses. Blood. 2009;113(16):3716–3725. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-09-179754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lux A, Yu X, Scanlan CN, Nimmerjahn F. Impact of immune complex size and glycosylation on IgG binding to human FcγRs. J Immunol. 2013;190(8):4315–4323. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1200501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hussain K, Hargreaves CE, Roghanian A, et al. Upregulation of FcγRIIb on monocytes is necessary to promote the superagonist activity of TGN1412. Blood. 2015;125(1):102–110. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-593061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Michaud HA, Gomard T, Gros L, et al. A crucial role for infected-cell/antibody immune complexes in the enhancement of endogenous antiviral immunity by short passive immunotherapy. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6(6):e1000948. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Abès R, Gélizé E, Fridman WH, Teillaud JL. Long-lasting antitumor protection by anti-CD20 antibody through cellular immune response. Blood. 2010;116(6):926–934. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-10-248609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.DiLillo DJ, Ravetch JV. Differential Fc-Receptor Engagement Drives an Anti-tumor Vaccinal Effect. Cell. 2015;161(5):1035–1045. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.04.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lim SH, Vaughan AT, Ashton-Key M, et al. Fc gamma receptor IIb on target B cells promotes rituximab internalization and reduces clinical efficacy. Blood. 2011;118(9):2530–2540. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-01-330357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Roghanian A, Teige I, Mårtensson L, et al. Antagonistic human FcγRIIB (CD32B) antibodies have anti-tumor activity and overcome resistance to antibody therapy in vivo. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(4):473–488. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vaughan AT, Iriyama C, Beers SA, et al. Inhibitory FcγRIIb (CD32b) becomes activated by therapeutic mAb in both cis and trans and drives internalization according to antibody specificity. Blood. 2014;123(5):669–677. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-04-490821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Croft M, Benedict CA, Ware CF. Clinical targeting of the TNF and TNFR superfamilies. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2013;12(2):147–168. doi: 10.1038/nrd3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Li F, Ravetch JV. Inhibitory Fcγ receptor engagement drives adjuvant and anti-tumor activities of agonistic CD40 antibodies. Science. 2011;333(6045):1030–1034. doi: 10.1126/science.1206954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.White AL, Beers SA, Cragg MS. FcγRIIB as a key determinant of agonistic antibody efficacy. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;382:355–372. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-07911-0_16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.White AL, Chan HT, Roghanian A, et al. Interaction with FcγRIIB is critical for the agonistic activity of anti-CD40 monoclonal antibody. J Immunol. 2011;187(4):1754–1763. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1101135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson NS, Yang B, Yang A, et al. An Fcγ receptor-dependent mechanism drives antibody-mediated target-receptor signaling in cancer cells. Cancer Cell. 2011;19(1):101–113. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xu Y, Szalai AJ, Zhou T, et al. Fc gamma Rs modulate cytotoxicity of anti-Fas antibodies: implications for agonistic antibody-based therapeutics. J Immunol. 2003;171(2):562–568. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.2.562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.White AL, Chan HT, French RR, et al. Conformation of the human immunoglobulin G2 hinge imparts superagonistic properties to immunostimulatory anticancer antibodies. Cancer Cell. 2015;27(1):138–148. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li F, Ravetch JV. Antitumor activities of agonistic anti-TNFR antibodies require differential FcγRIIB coengagement in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2013;110(48):19501–19506. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1319502110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.White AL, Chan HT, French RR, et al. FcγRΙΙB controls the potency of agonistic anti-TNFR mAbs. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2013;62(5):941–948. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1398-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.White AL, Dou L, Chan HT, et al. Fcγ receptor dependency of agonistic CD40 antibody in lymphoma therapy can be overcome through antibody multimerization. J Immunol. 2014;193(4):1828–1835. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li F, Ravetch JV. Apoptotic and antitumor activity of death receptor antibodies require inhibitory Fcγ receptor engagement. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(27):10966–10971. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208698109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Smith P, DiLillo DJ, Bournazos S, Li F, Ravetch JV. Mouse model recapitulating human Fcγ receptor structural and functional diversity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(16):6181–6186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203954109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Johnson P, Challis R, Chowdhury F, et al. Clinical and biological effects of an agonist anti-CD40 antibody: a Cancer Research UK phase I study. Clin Cancer Res. 2015;21(6):1321–1328. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-14-2355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Richman LP, Vonderheide RH. Role of crosslinking for agonistic CD40 monoclonal antibodies as immune therapy of cancer. Cancer Immunol Res. 2014;2(1):19–26. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-13-0152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dillon TM, Ricci MS, Vezina C, et al. Structural and functional characterization of disulfide isoforms of the human IgG2 subclass. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):16206–16215. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709988200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Martinez T, Guo A, Allen MJ, et al. Disulfide connectivity of human immunoglobulin G2 structural isoforms. Biochemistry. 2008;47(28):7496–7508. doi: 10.1021/bi800576c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Wypych J, Li M, Guo A, et al. Human IgG2 antibodies display disulfide-mediated structural isoforms. J Biol Chem. 2008;283(23):16194–16205. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M709987200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Allen MJ, Guo A, Martinez T, et al. Interchain disulfide bonding in human IgG2 antibodies probed by site-directed mutagenesis. Biochemistry. 2009;48(17):3755–3766. doi: 10.1021/bi8022174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Chan FK, Chun HJ, Zheng L, Siegel RM, Bui KL, Lenardo MJ. A domain in TNF receptors that mediates ligand-independent receptor assembly and signaling. Science. 2000;288(5475):2351–2354. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5475.2351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Smulski CR, Beyrath J, Decossas M, et al. Cysteine-rich domain 1 of CD40 mediates receptor self-assembly. J Biol Chem. 2013;288(15):10914–10922. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.427583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Remer M, White A, Glennie M, Al-Shamkhani A, Johnson P. The use of anti-CD40 mAb in cancer [published online ahead of print February 5, 2015]. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_427. doi:10.1007/83_2014_427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pedersen IM, Buhl AM, Klausen P, Geisler CH, Jurlander J. The chimeric anti-CD20 antibody rituximab induces apoptosis in B-cell chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells through a p38 mitogen activated protein-kinase-dependent mechanism. Blood. 2002;99(4):1314–1319. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.4.1314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Yakes FM, Chinratanalab W, Ritter CA, King W, Seelig S, Arteaga CL. Herceptin-induced inhibition of phosphatidylinositol-3 kinase and Akt Is required for antibody-mediated effects on p27, cyclin D1, and antitumor action. Cancer Res. 2002;62(14):4132–4141. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]