Abstract

A high incidence of breast and ovarian cancers has been linked to mutations in the BRCA1 gene. BRCA1 has been shown to be involved in both positive and negative regulation of gene activity as well as in numerous other processes such as DNA repair and cell cycle regulation. Since modulation of the RNA polymerase II carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) phosphorylation levels could constitute an interface to all these functions, we wanted to directly test the possibility that BRCA1 might regulate the phosphorylation state of the CTD. We have shown that the BRCA1 C-terminal region can negatively modulate phosphorylation levels of the RNA polymerase II CTD by the Cdk-activating kinase (CAK) in vitro. Interestingly, the BRCA1 C-terminal region can directly interact with CAK and inhibit CAK activity by competing with ATP. Finally, we demonstrated that full-length BRCA1 can inhibit CTD phosphorylation when introduced in the BRCA1−/− HCC1937 cell line. Our results suggest that BRCA1 could play its ascribed roles, at least in part, by modulating CTD kinase components.

The tumor suppressor gene BRCA1 encodes a protein of 1,863 amino acids that can interact with a plethora of factors involved in transcription, DNA repair, cell cycle regulation, apoptosis, genome integrity, and ubiquitination (16). Theses interactions underlie the extensive implication of BRCA1 in crucial processes related to tumorigenesis. However, how it can precisely ensure those functions still remains unclear. It has been suggested that BRCA1 could exert its tumor suppressor functions, particularly in DNA repair and cell cycle regulation, via its transcriptional activity (39, 53). Interestingly, various BRCA1 target genes carry out functions that could largely account for its involvement in DNA repair and cell cycle control. BRCA1 induces the expression of the DNA-damage-responsive genes p21WAF1/CIP1 (54) and GADD45 (24), the nucleotide excision repair (NER) genes DDB2 and XPC (26), and the cell cycle arrest genes p27 (62) and 14-3-3σ (5), while it represses the expression of the cell cycle-promoting gene cyclin B1 (35).

Transcriptional activators generally possess a DNA binding domain that binds specific sequences on promoters and an activating region known to interact with general transcription factors, the RNA polII holoenzyme, and chromatin remodeling machines to recruit the transcriptional machinery to a target promoter (34, 47). In contrast to those activators, BRCA1 has been shown to bind DNA only in a nonspecific fashion (46, 64) and has been shown to be a component of RNA polII holoenzyme (4, 51). Moreover, we have previously shown that at high concentration, the BRCA1 C-terminal region (amino acids 1528 to 1863) can stimulate transcription in vivo and in vitro without the requirement for a DNA-tethering function (41). That evidence suggests that BRCA1 can stimulate transcription by a mechanism alternative to recruitment, for example, by modulating an enzymatic activity. In vitro transcription assays using a highly purified system have demonstrated that the activation by Gal4-BRCA1, in contrast to Gal4-VP16, is highly influenced by TFIIH concentrations (23). Furthermore, immunopurification of BRCA1 complexes copurifies with transcriptionally active RNA polymerase II and TFIIH (51), suggesting functional and physical links between BRCA1 and TFIIH. Interestingly, TFIIH plays important roles in DNA repair and cell cycle regulation in addition to transcription (14), much like BRCA1.

TFIIH bears helicase and kinase activities required for open complex formation and promoter escape, respectively, during transcription initiation (17). The Cdk-activating kinase (CAK) subcomplex of TFIIH, formed by Cdk7, cyclin H, and MAT1 subunits, is responsible for the kinase activity (18). CAK can be found either in a free form or associated with TFIIH, and these states are believed to influence its substrate preference (65). Free CAK preferentially phosphorylates Cdk2, whereas TFIIH-associated CAK mainly phosphorylates the RNA polII carboxy-terminal domain (CTD) (50).

The mammalian RNA polII CTD is composed of 52 repeats of the heptapeptide YSPTSPS that can be highly phosphorylated. Moreover, the CTD phosphorylation state varies along with the transcriptional cycle (15). The hypophosphorylated form of RNA polII (IIa) is preferentially recruited to a target promoter to form a stable preinitiation complex (PIC), while the hyperphosphorylated form (IIo) is usually associated with the coding region of a gene (31). The Cdk7 subunit of TFIIH phosphorylates the CTD on serine 5 at the early stages of the transcriptional cycle, just after PIC formation (2). Cdk9, a member of the elongation factor P-TEFb, phosphorylates the CTD to render RNA polII more processive during elongation (38). Cdk8, a component of the RNA polII holoenzyme, is thought to phosphorylate the CTD prior to the binding of RNA polII to DNA and, by doing so, reduce the number of RNA polII molecules competent for initiation (55). It is therefore evident that the regulation of RNA polII phosphorylation constitutes an important step to modulate gene expression.

The RNA polII CTD phosphorylation status and activity are also modulated during the cell cycle (43). For example, the CTD becomes hyperphosphorylated during mitosis (3), and it was found that CTD phosphorylation by the mitogen-promoting factor in vitro results in the dissociation of transcription complexes (68). Furthermore, transcription and cell cycle regulation share common modulators of CTD phosphorylation, such as the CAK subcomplex of TFIIH. CAK has also been shown to function as a CAK in metazoans by phosphorylating cyclin-dependent kinases (see above) and therefore promotes cell cycle progression (57). In addition to being involved in transcription and cell cycle progression, CTD phosphorylation is believed to play an important role in transcription-coupled DNA repair and RNA polII ubiquitination (8, 48).

In an attempt to elucidate the mechanism by which BRCA1 could modulate gene expression as well as being involved in other processes such as DNA repair and cell cycle control, we investigated whether BRCA1 could directly modulate the RNA polII CTD phosphorylation levels. We found that the BRCA1 C-terminal region (herein BRCA1-C) can strongly inhibit CTD phosphorylation elicited by a HeLa nuclear extract. We have shown that BRCA1-C can inhibit free and TFIIH-associated CAK activity with respect to the RNA polII CTD as well as other substrates such as Cdk2 and TFIIE. We also found that BRCA1-C can directly interact with Cdk7 and compete with ATP. Finally, we have shown that full-length BRCA1 is able to inhibit CTD phosphorylation in a transient transfection assay.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

HeLa nuclear extract preparation and immunoprecipitation.

HeLa cell culture and nuclear extracts were prepared as previously described (41). Immunoprecipitations were performed as described previously (59) except that we used T75 flasks of HEK 293 cells to immunoprecipitate TFIIH and 300 μg of HeLa nuclear extract to immunoprecipitate Rpb1. Antibodies raised against the TFIIH p62 subunit (Q19) and RNA polymerase II N-terminal domain (N20) were obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Plasmids.

BRCA1 derivatives were amplified from the pcBRCA1-385 vector (gift of M. Erdos). PCR products were cloned into pET30a, pGEX-6P1, and pcDNA3. BRCA1 1646-1859 (gift of M. Glover) was subcloned into pET30a and pGEX-6P1. Cdk7, cyclin H, MAT1, and CTF- and Sp1-activating regions were amplified by PCR from a human cDNA library and cloned into pET30a. All PCR-amplified inserts have been sequenced. TFIIE-expressing vectors were gifts of B. Coulombe. Glutathione S-transferase (GST)-CTD-expressing vector was a gift of A. Barberis. Details on plasmid constructions are available upon request.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins from Escherichia coli.

All His-BRCA1 derivatives, His-Cdk7, His-cyclin H, His-MAT1, His-Sp1, and His-CTF were expressed in E. coli with the pET30a-expressing vector and purified on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose according to directions of the manufacturer (QIAGEN) in ATF buffer (20 mM Tris-acetate [pH 7.9], 150 mM potassium acetate, 20% glycerol, 0.2 mM EDTA [pH 8], 1 mM dithiothreitol). His-BRCA1 derivatives were further chromatographed by anion exchange on a MonoQ column (Amersham Biosciences) in ATF buffer. GST derivatives were expressed in E. coli and affinity purified on glutathione-Sepharose according to standard procedures. Expression and purification of TFIIE have been previously described (45). Gal4-p53 was obtained from K. Lemieux.

Expression and purification of recombinant proteins from Hi5 insect cells.

His-cyclin H, HA-Cdk7, and MAT1 baculoviruses were kind gifts of R. P. Fisher. Baculoviruses were amplified in Sf9 cells and proteins were expressed in Hi5 cells according to the directions of the manufacturer (Invitrogen). Cells were harvested and lysed as described previously (49). CAK and Cdk7/cycline H complexes were purified on Ni-nitrilotriacetic acid agarose followed by a gel filtration using a Superdex 200 HR 10/30 column (Amersham Biosciences).

Kinase assays.

All kinase assays were performed in 20 μl of kinase buffer (59) at 30°C for 30 min after addition of 10 μCi of [γ32-P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol). Kinases and substrates were added together along with 0, 12, or 24 pmol of BRCA1 derivatives for 5 min of preincubation at 30°C. We used 0.5 pmol of CAK, Cdk7/cyclin H, casein kinase II (from Roche), heart muscle kinase (gift of R. Blouin), and GST-CTD, 1.5 pmol of TFIIE and Cdk2/cyclin A (from Upstate), and 22 pmol of (YSPTSPS)3 (synthesized by Service de synthèse de peptide de l'est du Québec). Reactions were analyzed by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and detected with a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). (YSPTSPS)3 was run on a 20% SDS-tricine gel.

Kinase assays within PICs.

Biotinylated template was generated by PCR from G5E4T (10) and immobilized to M-280 streptavidin Dynabeads (Dynal Biotech) as previously described (67). A total of 500 ng of template was incubated with 60 μg of HeLa nuclear extracts in 50 μl of mix B (30 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 12 mM MgCl2, 60 mM potassium glutamate, 10 mM sodium butyrate, 2% polyvinylalcohol, 0.05% NP-40) for 45 min at 30°C and then washed three times with mix B and two times with kinase buffer (see above). PICs were resuspended in 30 μl of kinase buffer and incubated in the presence of 0, 12, or 24 pmol of BRCA1 derivatives and 1 μM ATP containing or lacking 10 μCi of [γ32-P]ATP (3,000 Ci/mmol) for 30 min at 30°C. Reactions were run by SDS-PAGE and revealed by phosphorimaging or immunoblotting with antibodies raised against the CTD (8WG16) and serine 5-phosphorylated CTD (H14) purchased from BabCO.

Protein-protein interaction assays.

GST-BRCA1 derivatives (48 pmol) were mixed with 24 pmol of E. coli-expressed His-Cdk7, His-cyclin H, or His-MAT1 in interaction buffer (750 mM potassium acetate, 20 mM HEPES [pH 7.9], 20% glycerol, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA [pH 8.0], 1 mM dithiothreitol) and incubated at 4°C for 2 h. Beads were washed four times in the same buffer, and proteins were analyzed by immunoblotting with antibodies raised against Cdk7 (C-19), cyclin H (C-18), or MAT1 (FL-309) from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Measurement of kinetic parameters.

Kinase assays were carried out in the buffer conditions described above with 25 nM of CAK-75 μM of GST-CTD-24 pmol of BRCA1-C with a constant [γ32-P]ATP/ATP ratio and the following ATP concentrations: 0.05, 0.5, 2, 5, 10, 20, 40, 100, and 200 μM. Each assay was carried out in triplicate for 10 min at 30°C. Reactions were analyzed by SDS-PAGE and detected by a PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). [γ32-P]ATP incorporation was quantified with ImageQuant software and determined using a standard curve and various concentrations of [γ32-P]ATP. Apparent Km and Vmax values were calculated by fitting the data to the Michaelis-Menten equation with SigmaPlot software.

HCC1937 transfections and small-scale nuclear extract preparation.

HCC1937 cell culture and transient transfections were performed as previously described (41) except that we used 4 μg of DNA per 100-mm-diameter dish with the BRCA1 C-terminal constructs and 8 μg with the full-length BRCA1 constructs. Nuclear extracts were prepared as described by Krum et al. (32). A total of 100 μg of proteins from nuclear extracts was run by SDS-PAGE and revealed by immunoblotting with antibodies raised against serine 5-phosphorylated CTD (H14; BabCO) and Rpb1 (N20; Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

RESULTS

The BRCA1 C-terminal region can inhibit RNA polymerase II CTD phosphorylation in vitro.

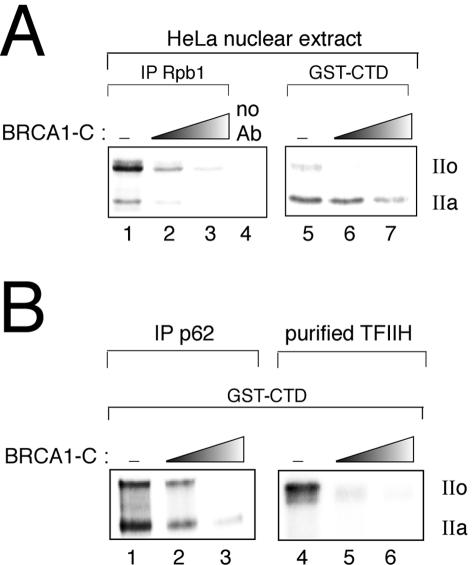

To determine whether BRCA1-C can influence CTD phosphorylation levels, we first performed in vitro kinase assays using a HeLa nuclear extract as a kinase source (Fig. 1A). To analyze the RNA polII CTD phosphorylation state, we immunoprecipitated Rpb1, the largest subunit of RNA polII, from nuclear extracts by use of the N20 antibody raised against the N-terminal region of the protein. Figure 1A, left panel, shows that the presence of BRCA1 strongly inhibits CTD phosphorylation of both the hypophosphorylated (IIa) and the hyperphosphorylated (IIo) forms of RNA polII. A similar experiment was then performed by adding the fusion protein GST-CTD, which contains the 52 repeats of the heptapeptide YSPTSPS from mouse CTD, as a substrate for nuclear extract-containing kinases (Fig. 1A, right panel). As seen with Rpb1, the phosphorylation level of GST-CTD was negatively affected by the addition of BRCA1. This inhibition was not observed when BSA was added instead of BRCA1-C; furthermore, the effect is not due to a phosphatase activity, since BRCA1 does not have any effect in a phosphatase assay using prephosphorylated GST-CTD (data not shown). Taken together, these results suggest that BRCA1 can negatively regulate CTD phosphorylation by at least one nuclear kinase.

FIG. 1.

The BRCA1 C-terminal region can inhibit RNA polymerase II CTD phosphorylation in vitro. (A) Kinase assays using a HeLa nuclear extract as a kinase source. (Left panel) Rpb1 was immunoprecipitated from HeLa nuclear extracts by use of the N20 antibody or beads alone as a negative control prior to being used as a substrate for nuclear extract kinases. (Right panel) GST-CTD was added to a nuclear extract as a substrate. (B) Kinase assay on GST-CTD by an immunoprecipitation using the p62 subunit of TFIIH or a highly purified TFIIH preparation as a kinase source. IP, immunoprecipitation; Ab, antibody; IIa and IIo, hypo- and hyperphosphorylated forms of the CTD, respectively.

Among the various CTD kinases, TFIIH is of particular interest for our study because the in vitro transcriptional activity of BRCA1 has been linked to TFIIH (23). We therefore assessed the effect of BRCA1 on TFIIH kinase activity by performing a kinase assay on GST-CTD by use of an immunoprecipitation with the TFIIH p62 subunit as a kinase source. Figure 1B, left panel, shows that BRCA1-C is able to inhibit GST-CTD phosphorylation under those conditions. Although we cannot eliminate the possibility that CTD kinases other than Cdk7 remain associated with our TFIIH immunoprecipitate, this result suggests that BRCA1 can negatively regulate TFIIH kinase activity.

To ensure that the inhibitory effect of BRCA1-C on CTD phosphorylation is due to the TFIIH activity, we tested a highly purified TFIIH preparation from HeLa cells (kindly provided by Jean-Marc Egly) in a kinase assay. The right panel of Fig. 1B shows that highly purified TFIIH efficiently phosphorylates GST-CTD and leads mainly to the hyperphosphorylated form of the CTD. The figure further shows that BRCA1-C strongly inhibits that phosphorylation event. The kinetic differences between the immunoprecipitated and highly purified TFIIH are probably due to a difference in the amount of Cdk7 and to the presence of proteins that coimmunoprecipitate with TFIIH. This result suggests that the negative effect that BRCA1-C has on CTD phosphorylation by a HeLa nuclear extract (Fig. 1A) may be due to the inhibition of the TFIIH kinase activity. However, our results do not exclude the possibility that BRCA1 might inhibit other CTD kinases.

BRCA1 can inhibit CTD phosphorylation in a transcription PIC in vitro.

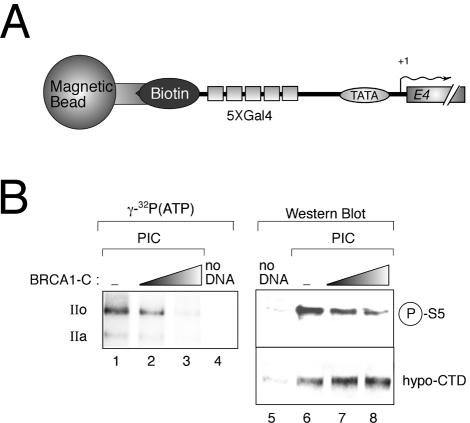

Once assembled into a PIC, the transcriptional machinery must leave the promoter to ensure RNA synthesis, a step called “promoter escape” that requires the TFIIH kinase activity (17). We thus assessed the effect of BRCA1-C on a CTD kinase activity within a PIC by use of a DNA template bearing five Gal4 binding sites upstream of the adenoviral E4 promoter and immobilized to streptavidin-conjugated magnetic beads (Fig. 2A). Figure 2B, lanes 1 to 4, shows the negative effect of BRCA1-C on the global phosphorylation state of Rpb1 within a PIC. In lanes 5 to 8 of Fig. 2B, CTD phosphorylation levels were revealed by immunoblotting using an antibody raised against the phosphorylated form of serine 5 in the consensus heptapeptide YSPTSPS (upper panel). The 8WG16 antibody raised against the CTD was used as a loading control (lanes 5 to 8, lower panel). This assay shows that BRCA1-C can inhibit CTD phosphorylation of a TFIIH target residue within a PIC context.

FIG. 2.

The BRCA1 C-terminal region inhibits CTD phosphorylation in transcription PICs in vitro. (A) Schematic representation of the template DNA used in this experiment. Gal4, Gal4 binding sites; +1, transcription start site. (B) Kinase assays with PICs. Lanes 1 to 4 represent global RNA polII CTD phosphorylation levels, and lanes 5 to 8 represent phosphoserine 5 (upper panel) and hypophosphorylated RNA polII (lower panel). IIa and IIo, hypo- and hyperphosphorylated forms of the CTD, respectively.

BRCA1 inhibits CAK-mediated phosphorylation of the CTD and other substrates.

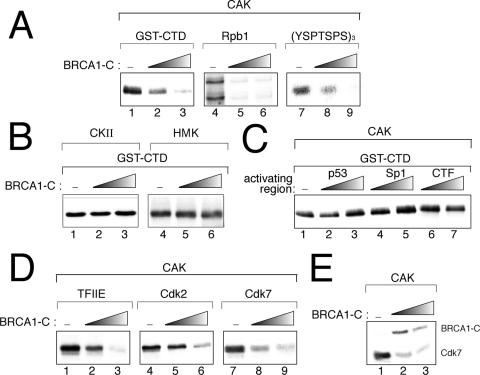

To provide further insight on the inhibitory effect of BRCA1 on CTD phosphorylation, we next decided to investigate the effect of BRCA1-C on CAK, which is the TFIIH subcomplex responsible for the kinase activity. We thus purified recombinant CAK from a baculoviral expression system. As previously reported (65), we only observe the hypophosphorylated form of GST-CTD in kinase assay with CAK, in contrast to the results seen with TFIIH. This is in accord with previous results reporting that the CTD is a better substrate for TFIIH than for free CAK (50). Figure 3A first shows that BRCA1-C inhibits CAK activity using GST-CTD (lanes 1 to 3) and that Rpb1 immunoprecipitated from a HeLa nuclear extract (lanes 4 to 6) as substrates. Whereas we only obtained the IIa form with GST-CTD, we observed the IIa and IIo forms of the CTD when visualizing Rpb1 (lanes 4 to 6). This could be explained by the fact that the immunoprecipitation was performed with the N-terminal portion of the protein and thus brought both forms of Rpb1 or that Rpb1 is a better substrate than GST-CTD for CAK. In vertebrates, the 52nd heptapeptide of the RNA polII CTD is followed by a conserved 10-amino-acid sequence that is involved in splicing and poly(A) site cleavage (20) and contains interaction sites for c-Abl and casein kinase II (13). To verify whether all the 52 heptapeptides and the 10-amino-acid sequence are required for the inhibitory effect of BRCA1-C on CTD phosphorylation by CAK, a triheptapeptide (YSPTSPS)3 has been used as a substrate. Figure 3A, lanes 7 to 9, shows that the phosphorylation of a peptide bearing only three repeats of the heptapeptide YSPTSPS is inhibited by the presence of BRCA1-C. To investigate the specificity of BRCA1-C toward CTD kinases, we performed kinase assays with casein kinase II (lanes 1 to 3), which phosphorylates the CTD in the 10-amino-acid sequence only (13), and the heart muscle kinase (lanes 4 to 6), which is commonly used for nonspecific phosphorylation in vitro. Figure 3B clearly shows that BRCA1-C does not have any significant effect on those kinases when GST-CTD is used as a substrate. Given the fact that certain acidic activators interact with TFIIH (7), we wanted to determine whether CAK inhibition is specific to BRCA1-C or whether it could also be common to other types of activating regions. We therefore tested three types of activating regions, acidic, glutamine rich, and proline rich, that are exemplified by the p53-, Sp1-, and CTF-activating regions, respectively. Figure 3C shows that the p53 (lanes 2 to 3)-, Sp1 (lanes 4 to 5)-, and CTF (lanes 6 to 7)-activating regions are unable to reduce GST-CTD phosphorylation levels by CAK.

FIG. 3.

The BRCA1 C-terminal region specifically inhibits CAK-mediated phosphorylation of the CTD and other substrates. (A) Kinase assays with CAK expressed from recombinant baculoviruses. CAK-mediated CTD phosphorylation was assessed using GST-CTD, Rpb1 immunoprecipitated from a HeLa nuclear extract using the N20 antibody, or the synthetic triheptapeptide (YSPTSPS)3 as a substrate. (B) Kinase assays using GST-CTD performed with commercially available casein kinase II or heart muscle kinase. (C) Kinase assays on GST-CTD performed with CAK and activating regions of transcriptional activators. p53, p53 amino acids 1 to 93 fused to Gal4 DNA binding domain; Sp1, Sp1 amino acids 263 to 499; CTF, CTF amino acids 399 to 499. (D) CAK kinase assays using TFIIEα or Cdk2 as a substrate. The right panel shows the autophosphorylation of Cdk7. (E) Kinase assay with CAK and BRCA1 (amino acids 1528 to 1863), showing the CAK-mediated phosphorylation of BRCA1 and the Cdk7 autophosphorylation.

CAK possesses many substrates in addition to the CTD, such as transcription factors and cyclin-dependent kinases (50). To verify whether BRCA1-C acts on CAK activity in a CTD-specific manner, we performed kinase assays using various CAK substrates. Figure 3D shows the ability of BRCA1-C to inhibit CAK-dependent phosphorylation of TFIIE, Cdk2, and Cdk7 itself. CAK autophosphorylation on the Cdk7 subunit has been reported previously (22), but the importance of its enzymatic activity or stability remains unknown. Another interesting observation is that BRCA1-C is phosphorylated in our kinase assays with CAK. In fact, we observed that in the absence of another substrate, BRCA1 can be strongly phosphorylated by CAK and can inhibit its own phosphorylation (Fig. 3E, top bands). Interestingly, the latter results suggest that BRCA1 might inhibit CAK activity in cell cycle progression as well as in the transcription cycle.

MAT1 is not a target of BRCA1-mediated CAK inhibition in vitro.

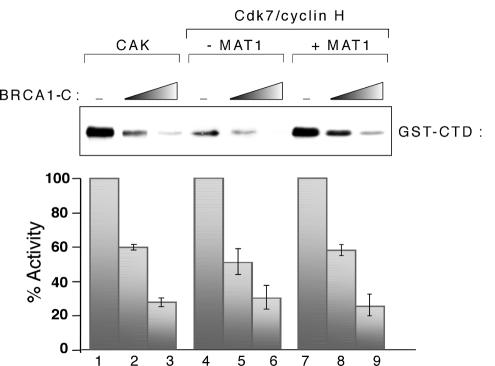

MAT1 plays important roles within the CAK complex, as it confers stability and substrate specificity (19, 65) and is involved in protein-protein interactions with core TFIIH, substrates, and regulators (9, 29, 30, 56). To directly address the requirement of MAT1 in BRCA1-mediated inhibition of CAK, we expressed a Cdk7/cyclin H complex from baculoviruses and purified it as described for CAK. The absence of endogenous MAT1 from the binary complex has been verified by Western blot analysis (data not shown). The graphic representation of Fig. 4 shows that the kinase activity of the Cdk7/cyclin H complex is inhibited by BRCA1-C as efficiently as that of CAK. Moreover, supplementing the Cdk7/cyclinH complex with an equimolar amount of the MAT1 subunit stimulates the kinase activity but does not significantly influence the negative effect of BRCA1-C on GST-CTD phosphorylation (compare lanes 4 to 6 and 7 to 9). Thus, MAT1 is not necessary for BRCA1-C-mediated inhibition of CAK activity in vitro and its presence does not alter the negative effect of BRCA1-C on CAK-dependent phosphorylation.

FIG. 4.

MAT1 is not required for BRCA1-mediated CAK inhibition in vitro. Kinase assays of GST-CTD show the inhibitory effect of BRCA1-C on CAK and Cdk7/cyclin H complex without MAT1 or supplemented with MAT1. The lower panel shows a quantification of the experiment. Inhibition of the CTD phosphorylation was expressed as the percentage of the control without BRCA1.

Amino acids 1528 to 1646 of BRCA1 are sufficient for CAK inhibition.

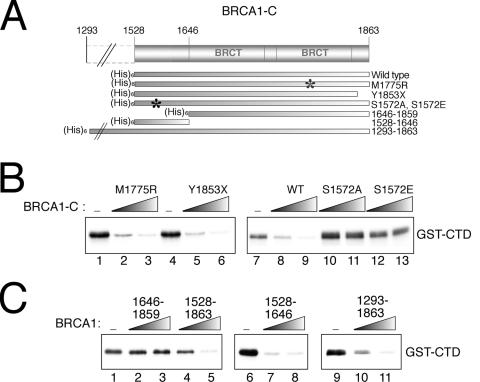

In all the experiments described above, we used a BRCA1-C derivative comprised of amino acids 1528 to 1863 to be consistent with previous studies that used this precise region to test the transcriptional activity of the BRCA1 C-terminal region (12, 41). As shown in Fig. 5A, that region of BRCA1 contains two sequence repeats called BRCT (for “BRCA1 C terminal”). BRCT domains are thought to be involved in protein-protein interactions with other BRCT repeats or with unrelated protein domains (16) and have recently been identified as phosphopeptide binding domains (37, 66). The BRCT domain has been shown to be important for the transcriptional activity (11) and tumor suppressor function (58) of BRCA1. We thus wanted to assess the importance of BRCT in BRCA1-C-mediated inhibition of CAK activity. To address that issue, we first verified the ability of the mutant BRCA1-C derivatives Y1853X and M1775R, which show transcription defects and possess an unstable BRCT folding function (40, 60, 61), to inhibit CAK activity. Surprisingly, both mutants retain the ability to inhibit CAK-dependent phosphorylation of GST-CTD (Fig. 5B, lanes 1 to 6), suggesting that the BRCT folding is not required for that BRCA1 function. We had previously generated BRCA1-C derivatives mutated at serine 1572, which is a target residue for phosphorylation by casein kinase II in vivo (42), to study the importance of the phosphorylation state of BRCA1-C for its functions. Since serine 1572 is located outside the BRCT domain, we were curious to investigate the effect of BRCA1-C mutants S1572A and S1572E on CAK activity. Unexpectedly, both mutants lose the ability to inhibit CAK activity (Fig. 5B, lanes 10 to 13). Since BRCA1-C derivatives mutated inside the BRCT domain maintain the ability to inhibit CAK activity and derivatives bearing a mutation upstream of the BRCT lose it, we wanted to directly assess the requirement for the BRCT domain, compared to that for the region upstream to it, in the inhibition of CAK activity. We generated a BRCA1 derivative carrying amino acids 1646 to 1859, which encompasses the BRCT domain and a few more residues in the C-terminal region, as well as a BRCA1 derivative carrying the upstream part of the protein (amino acids 1528 to 1646). Figure 5C, lanes 1 to 3, clearly shows that BRCA1 (amino acids 1646 to 1859) alone fails to inhibit CAK activity when GST-CTD is used. In contrast, BRCA1 (amino acids 1528 to 1646) is able to inhibit CAK activity when the same substrate is used and with efficiency equal to that seen with BRCA1-C (Fig. 5C, lanes 6 to 8 and 1, 4, and 5). These results are consistent with part B of the figure and thus reveal the importance of BRCA1 amino acids 1528 to 1646 in the inhibition of CAK activity. In fact, BRCA1 amino acids 1528 to 1646 are sufficient to confer that specific function to BRCA1-C, at least under our conditions. To verify whether the inhibitory activity ascribed to amino acids 1528 to 1646 is not strictly observed in a N-terminal context, we tested a BRCA1 derivative comprising amino acids 1293 to 1863. Figure 5C, lanes 9 to 11, shows that the CAK inhibition effect can also be observed when BRCA1 amino acids 1293 to 1863 are used.

FIG. 5.

A region upstream of the BRCT domain is important for BRCA1-mediated inhibition of CAK activity. (A) Schematic representation of the BRCA1 derivatives tested for their ability to inhibit CAK activity. The asterisks represent the location of the mutation. (B) Kinase assays with CAK of GST-CTD showing the effect of the presence of BRCA1-C mutants M1775R, Y1853X, S1572A, and S1572E compared to that of the wild-type (WT) protein. (C) Kinase assays with CAK on GST-CTD comparing the inhibition activity of the BRCT domain (amino acids 1646 to 1859) with that of a region upstream to the BRCT (amino acids 1528 to 1646). The right panel shows that a BRCA1 fragment bearing amino acids 1293 to 1863 has an effect similar to that of BRCA1-C.

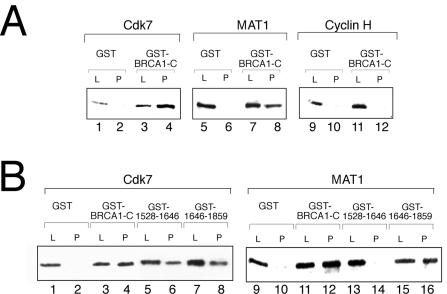

The BRCA1 C-terminal region interacts with CAK.

To gain further insight into the mechanism by which BRCA1-C inhibits CAK activity, we investigated potential interactions between BRCA1-C and CAK subunits. Pulldown assays were performed by incubating GST-BRCA1-C with Cdk7, cyclin H, or MAT1. Figure 6A shows that GST-BRCA1-C directly and strongly interacts with both the Cdk7 (lanes 1 to 4) and MAT1 subunits (lanes 5 to 8) but not with cyclin H (lanes 9 to 12). We then assayed GST-BRCA1 (amino acids 1646 to 1859) and GST-BRCA1 (1528 to 1646) for their interaction with both Cdk7 and MAT1. Figure 6B demonstrates that BRCA1 (amino acids 1646 to 1859), which bears the BRCT domain, interacts with both proteins (lanes 7 to 8 and 15 to 16), whereas BRCA1 (1528 to 1646) only interacts with Cdk7 (lanes 5 to 6 and 13 to 14). To summarize, the BRCT domain interacts with both Cdk7 and MAT1 but does not inhibit CAK activity, whereas the BRCA1 (amino acids 1528 to 1646) derivative only interacts with Cdk7 and is sufficient to inhibit CAK-mediated phosphorylation. Taken together, these results suggest that CAK inhibition by BRCA1-C requires an interaction between Cdk7 and the BRCA1 amino acids 1528 to 1646 whereas the interactions involving MAT1 and the BRCT domain are dispensable for that activity in vitro. This idea is consistent with the results shown in Fig. 4 that suggest a dispensable role for MAT1 in the inhibition of CAK-dependent phosphorylation by BRCA1-C in vitro.

FIG. 6.

The BRCA1 C-terminal region directly interacts with the Cdk7 and MAT1 subunits of CAK. (A) GST pulldown assays performed with GST-BRCA1-C in the presence of bacterially expressed Cdk7, MAT1, or cyclin H subunits. (B) GST pulldown assays performed with GST-BRCA1 derivatives bearing amino acids 1528 to 1863, 1528 to 1646, or 1646 to 1859 in the presence of bacterially expressed Cdk7 or MAT1. CAK subunits were revealed by immunoblotting with the appropriate antibody as indicated on top of each panel. L, load (5% total input); P, pellet.

BRCA1 inhibits CAK activity by competing with ATP.

The inhibition of CTD phosphorylation by BRCA1-C does not appear to be the consequence of a competition between BRCA1 and GST-CTD, since increasing GST-CTD concentrations in kinase assays does not influence the level of CAK inhibition by BRCA1-C (data not shown). However, we observed that increasing ATP concentrations in our kinase assays significantly decreases the ability of BRCA1-C to inhibit CAK-dependent GST-CTD phosphorylation (data not shown). We thus determined the kinetic parameters of CAK for ATP by performing kinase assays using a saturating concentration of GST-CTD and increasing ATP concentrations. We obtained a Km(ATP) of 2.88 ± 0.34 μM in the absence of BRCA1-C compared to 9.65 ± 0.75 μM in the presence of BRCA1-C, while the Vmax is 1.36 ± 0.036 pmol of Pi/min in the absence of BRCA1-C and does not significantly change in the presence of BRCA1-C (1.24 ± 0.042 pmol of Pi/min). Our Vmax value is very similar to the value previously obtained by another group (1.6 pmol/min) (33). Our Km(ATP) value is quite different from the 40 μM value previously published (52); however, this can easily be explained by the differences in enzyme preparation and activity measurement procedures. The kinetic changes observed in the presence of BRCA1-C are typical of competitive inhibitors, which do not change the Vmax value but increase the Km value (27). One could argue that this competition effect is a consequence of BRCA1-C phosphorylation by CAK, but this is not likely because the S1572A and S1572E mutants are dramatically more phosphorylated than wild-type BRCA1 and yet they are unable to inhibit CTD phosphorylation (data not shown and Fig. 5).

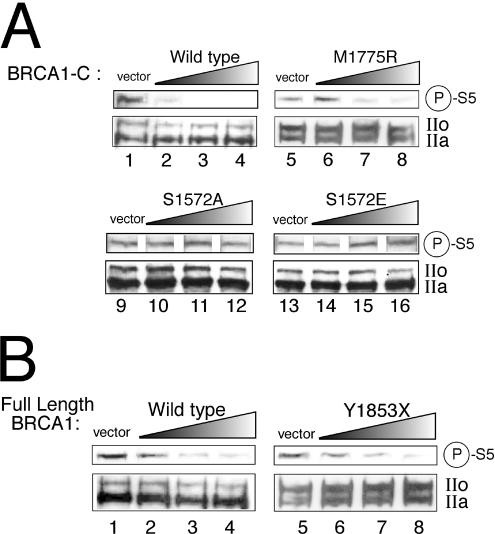

Overexpressed BRCA1 can inhibit CTD phosphorylation in vivo.

We next wanted to investigate the ability of BRCA1 to inhibit CTD phosphorylation in a cellular context. We first analyzed the phosphorylation state of the RNA polymerase II CTD in the BRCA1−/− HCC1937 cell line transfected with constructs expressing the BRCA1 C-terminal region. Nuclear proteins were extracted, and CTD phosphorylation levels were revealed by immunoblotting using an antibody raised against the phosphorylated form of serine 5 in the heptapeptide. As shown in Fig. 7A, wild-type BRCA1-C (lanes 1 to 4) and the BRCA1-C M1775R mutant (lanes 5 to 8) both inhibit serine 5 phosphorylation when overexpressed in HCC1937 cells whereas the S1572A (lanes 9 to 12) and S1572E (lanes 13 to 16) mutants do not. Reverse transcription PCR experiments have been performed to ensure that the wild-type and mutant constructs were similarly expressed (data not shown). We next wanted to determine whether full-length BRCA1 could also perform that inhibitory function on CTD phosphorylation. Panel B of Fig. 7 shows that full-length wild-type BRCA1 and the Y1853X mutant both efficiently inhibit serine 5 phosphorylation when introduced into HCC1937 cells (lanes 1 to 4 for the wild type and lanes 5 to 8 for Y1853X). The IIo and IIa forms of the RNA polII were revealed with the N20 antibody raised against the N-terminal portion of Rpb1. As can be seen on the lower panels of Fig. 7A and B, BRCA1 does not modify the ratio between the IIo and IIa forms. Similar results were also obtained when MCF7 cells were used (data not shown).

FIG. 7.

BRCA1 inhibits CTD phosphorylation in HCC1937 transfected cells. HCC1937 cells transiently transfected with the wild type or mutant BRCA1-C derivatives (A) or full-length BRCA1 (B) were analyzed by immunoblotting using antibodies raised against the serine 5-phosphorylated form of the CTD (upper panels) and the N-terminal region of Rpb1 (lower panels). IIo and IIa, the hyper- and the hypophosphorylated forms of RNA polII, respectively. Two, 3, and 4 μg of BRCA1-C constructs and 4, 6, and 8 μg of full-length BRCA1 constructs were used.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we investigated whether BRCA1 could influence RNA polII CTD phosphorylation levels. We first found that BRCA1-C could inhibit CTD phosphorylation in vitro when a HeLa nuclear extract was used. In more-purified systems, we observed that BRCA1-C inhibited TFIIH kinase activity in solution and within the context of a PIC. We also demonstrated that BRCA1-C inhibited CAK-dependent phosphorylation of GST-CTD, (YSPTSPS)3, TFIIE, and Cdk2 and that MAT1 was dispensable for this inhibition. We defined a BRCA1 region comprised of amino acids 1528 to 1646 that is sufficient for that activity and showed that it directly interacted with Cdk7. Furthermore, we found that BRCA1-C inhibited CAK by competing with ATP. Finally, we demonstrated that the BRCA1 C-terminal region, as well as full-length BRCA1, could inhibit CTD phosphorylation when overexpressed in HCC1937 cells.

BRCA1 is found in a form of RNA polII holoenzyme that is transcriptionally active and that contains transcription factors TFIIE, TFIIF, and TFIIH (51). Furthermore, BRCA1 has recently been shown to interact specifically with hyperphosphorylated RNA polII in preference to hypophosphorylated RNA polII (32). Consistent with these data, we described functional interactions between BRCA1-C, the RNA polII CTD, TFIIH, and TFIIE. It is conceivable that BRCA1 could inhibit CTD phosphorylation within a “soluble holoenzyme” context to maintain the RNA polII in a hypophosphorylated form and therefore increase the number of RNA polII molecules competent for promoter binding. Accordingly, we found that BRCA1-C was able to inhibit RNA polII CTD phosphorylation when a semipurified holoenzyme preparation was used (data not shown). After PIC formation, CTD phosphorylation is achieved by TFIIH to allow promoter clearance. Note that this phosphorylation event induces a conformational change that could lead to PIC dissociation (69). To support this idea, in vitro experiments using yeast nuclear extracts showed that addition of ATP to PICs resulted in their dissociation and loss of their activity in a TFIIH-dependent manner (67). Therefore, it is reasonable to think that the inhibition of the TFIIH kinase activity in a PIC context could help maintain its stability until promoter escape is ultimately required to initiate RNA synthesis. Since positive regulators of CAK such as TFIIE (44) exist within the holoenzyme and the PIC, negative regulators could be important to ensure fine tuning of CTD phosphorylation levels. In consistency with that possibility, we also observed that BRCA1-C could antagonize the stimulatory effect of TFIIE on CAK activity when GST-CTD was used as a substrate in an in vitro kinase assay (data not shown).

Since BRCA1-C Y1853X and M1775R mutants usually show transcription defects and since they are associated with cancer predisposition, we were surprised to observe their ability to inhibit CAK activity as efficiently as the wild-type protein. This result revealed that this novel property of BRCA1 could be distinct from previously described activities observed when studies using the BRCA1 C-terminal region were performed (12, 23, 28). Indeed, we noticed that the BRCT domain seems to be dispensable for the CAK inhibition activity under our in vitro conditions and when overexpressed in cell lines, since the 1528-to-1646 BRCA1 derivative that lacks the entire BRCT domain is sufficient for in vitro inhibition and the Y1853X and M1775R mutants inhibit serine 5 phosphorylation in transient transfection assays. Nonetheless, considering the previously ascribed roles for BRCT domains in interactions with other protein domains and phosphopeptides (16, 37, 66), it is conceivable that the BRCT domain might be of greater relevance for that novel BRCA1 function in vivo to establish extensive contacts with functional partners. In consistency, we also reported that although MAT1 is not necessary for BRCA1-mediated inhibition of CAK activity in vitro, it directly interacted with its BRCT domain.

Kinetic experiments led us to propose that BRCA1-C inhibited CAK activity by competing with ATP. In fact, BRCA1-C significantly increases the apparent Km(ATP) value but did not significantly affect the Vmax of the reaction. Usually, such competitive inhibitors act by binding to the same site on the enzyme (27). Since we have shown that BRCA1-C directly bound to Cdk7, we can speculate that it interferes with ATP binding to CAK. We and others reported a Km(ATP) of CAK in the micromolar range (52), whereas cellular ATP levels are predicted to be in the millimolar range (63). Nevertheless, we have shown that BRCA1-C could still inhibit CTD phosphorylation when introduced in the HCC1937 breast cancer cell line. Furthermore, we showed that full-length BRCA1 was also able to efficiently inhibit CTD phosphorylation in transfected cells, supporting the idea that BRCA1 can inhibit CAK activity in a cellular context. Thus, BRCA1-mediated inhibition of CAK activity might be regulated by ATP levels in vivo and might be of great relevance in situations where ATP levels could be locally or temporally decreased, for example, under conditions of cellular proliferation, apoptosis, or heat shock (36).

The apparent competition between BRCA1-C and ATP is consistent with the ability of BRCA1-C to inhibit CAK activity with respect to different substrates in vitro. This suggests that BRCA1-mediated inhibition of CAK activity might not be limited to the regulation of transcription but might be extended to other cellular processes. In fact, we showed that BRCA1-C inhibits CAK-dependent phosphorylation of Cdk2, an important positive regulator of cell cycle progression (21). Cdks are tightly regulated by association with their cognate cyclin and by phosphorylation by CAK. Our results could suggest a putative role for BRCA1 in cell cycle control in which it acts as a negative regulator of CAK. A previous report has described a negative role for CAK kinase activity in NER of DNA damage in vitro (6). In contrast to the results seen with CAK, BRCA1 positively contributes to NER and transcription-coupled repair (1, 25, 26). Given the ability of BRCA1 to inhibit CAK-dependent phosphorylation of different substrates, one might speculate that BRCA1 could contribute to enhance NER and/or transcription-coupled repair by inhibiting CAK activity at sites of DNA damage where both proteins would be recruited.

Acknowledgments

We thank A. Barberis, R. Blouin, B. Coulombe, M. Erdos, R. P. Fisher, and M. Glover for expression plasmids and baculoviruses and J.-M. Egly for TFIIH. We are grateful to Nadia Boufaied for the original idea of an implication of BRCA1 in the modulation of phosphorylation and to Joëlle Brodeur, Marco Di Fruscio, Benoît Leblanc, Karine Lemieux, and Sébastien Rodrigue for critical comments on the manuscript.

This work was supported by the Cancer Research Society Inc. of Canada to L.G. L.G. holds a Canada Research Chair on mechanisms of gene transcription. A.M. and B.G. are recipients of a fellowship from the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott, D. W., M. E. Thompson, C. Robinson-Benion, G. Tomlinson, R. A. Jensen, and J. T. Holt. 1999. BRCA1 expression restores radiation resistance in BRCA1-defective cancer cells through enhancement of transcription-coupled DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 274:18808-18812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Akoulitchev, S., T. P. Makela, R. A. Weinberg, and D. Reinberg. 1995. Requirement for TFIIH kinase activity in transcription by RNA polymerase II. Nature 377:557-560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Akoulitchev, S., and D. Reinberg. 1998. The molecular mechanism of mitotic inhibition of TFIIH is mediated by phosphorylation of CDK7. Genes Dev. 12:3541-3550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson, S. F., B. P. Schlegel, T. Nakajima, E. S. Wolpin, and J. D. Parvin. 1998. BRCA1 protein is linked to the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme complex via RNA helicase A. Nat. Genet. 19:254-256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aprelikova, O., A. J. Pace, B. Fang, B. H. Koller, and E. T. Liu. 2001. BRCA1 is a selective co-activator of 14-3-3 sigma gene transcription in mouse embryonic stem cells. J. Biol. Chem. 276:25647-25650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Araujo, S. J., F. Tirode, F. Coin, H. Pospiech, J. E. Syvaoja, M. Stucki, U. Hubscher, J. M. Egly, and R. D. Wood. 2000. Nucleotide excision repair of DNA with recombinant human proteins: definition of the minimal set of factors, active forms of TFIIH, and modulation by CAK. Genes Dev. 14:349-359. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blau, J., H. Xiao, S. McCracken, P. O'Hare, J. Greenblatt, and D. Bentley. 1996. Three functional classes of transcriptional activation domain. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:2044-2055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bregman, D. B., R. Halaban, A. J. van Gool, K. A. Henning, E. C. Friedberg, and S. L. Warren. 1996. UV-induced ubiquitination of RNA polymerase II: a novel modification deficient in Cockayne syndrome cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:11586-11590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Busso, D., A. Keriel, B. Sandrock, A. Poterszman, O. Gileadi, and J. M. Egly. 2000. Distinct regions of MAT1 regulate cdk7 kinase and TFIIH transcription activities. J. Biol. Chem. 275:22815-22823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carey, M., Y. S. Lin, M. R. Green, and M. Ptashne. 1990. A mechanism for synergistic activation of a mammalian gene by GAL4 derivatives. Nature 345:361-364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carvalho, M. A., B. Billack, E. Chan, T. Worley, C. Cayanan, and A. N. Monteiro. 2002. Mutations in the BRCT domain confer temperature sensitivity to BRCA1 in transcription activation. Cancer Biol. Ther. 1:502-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chapman, M. S., and I. M. Verma. 1996. Transcriptional activation by BRCA1. Nature 382:678-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chapman, R. D., B. Palancade, A. Lang, O. Bensaude, and D. Eick. 2004. The last CTD repeat of the mammalian RNA polymerase II large subunit is important for its stability. Nucleic Acids Res. 32:35-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Coin, F., and J. M. Egly. 1998. Ten years of TFIIH. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 63:105-110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dahmus, M. E. 1996. Phosphorylation of mammalian RNA polymerase II. Methods Enzymol. 273:185-193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deng, C. X., and S. G. Brodie. 2000. Roles of BRCA1 and its interacting proteins. Bioessays 22:728-737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dvir, A., J. W. Conaway, and R. C. Conaway. 2001. Mechanism of transcription initiation and promoter escape by RNA polymerase II. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 11:209-214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feaver, W. J., J. Q. Svejstrup, N. L. Henry, and R. D. Kornberg. 1994. Relationship of CDK-activating kinase and RNA polymerase II CTD kinase TFIIH/TFIIK. Cell 79:1103-1109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fisher, R. P., P. Jin, H. M. Chamberlin, and D. O. Morgan. 1995. Alternative mechanisms of CAK assembly require an assembly factor or an activating kinase. Cell 83:47-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fong, N., G. Bird, M. Vigneron, and D. L. Bentley. 2003. A 10 residue motif at the C-terminus of the RNA pol II CTD is required for transcription, splicing and 3′ end processing. EMBO J. 22:4274-4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garrett, M. D., and A. Fattaey. 1999. CDK inhibition and cancer therapy. Curr. Opin. Genet. Dev. 9:104-111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Garrett, S., W. A. Barton, R. Knights, P. Jin, D. O. Morgan, and R. P. Fisher. 2001. Reciprocal activation by cyclin-dependent kinases 2 and 7 is directed by substrate specificity determinants outside the T loop. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21:88-99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haile, D. T., and J. D. Parvin. 1999. Activation of transcription in vitro by the BRCA1 carboxyl-terminal domain. J. Biol. Chem. 274:2113-2117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harkin, D. P., J. M. Bean, D. Miklos, Y. H. Song, V. B. Truong, C. Englert, F. C. Christians, L. W. Ellisen, S. Maheswaran, J. D. Oliner, and D. A. Haber. 1999. Induction of GADD45 and JNK/SAPK-dependent apoptosis following inducible expression of BRCA1. Cell 97:575-586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hartman, A. R., and J. M. Ford. 2003. BRCA1 and p53: compensatory roles in DNA repair. J. Mol. Med. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Hartman, A. R., and J. M. Ford. 2002. BRCA1 induces DNA damage recognition factors and enhances nucleotide excision repair. Nat. Genet. 32:180-184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Horton, H. R., L. A. Moran, R. S. Ochs, J. D. Rawn, and K. G. Scrimgeour. 1994. (ed.) Principes de biochimie. DeBoeck Université ed., Brussels, Belgium.

- 28.Hu, Y. F., Z. L. Hao, and R. Li. 1999. Chromatin remodeling and activation of chromosomal DNA replication by an acidic transcriptional activation domain from BRCA1. Genes Dev. 13:637-642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Inamoto, S., N. Segil, Z. Q. Pan, M. Kimura, and R. G. Roeder. 1997. The cyclin-dependent kinase-activating kinase (CAK) assembly factor, MAT1, targets and enhances CAK activity on the POU domains of octamer transcription factors. J. Biol. Chem. 272:29852-29858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ko, L. J., S. Y. Shieh, X. Chen, L. Jayaraman, K. Tamai, Y. Taya, C. Prives, and Z. Q. Pan. 1997. p53 is phosphorylated by CDK7-cyclin H in a p36MAT1-dependent manner. Mol. Cell. Biol. 17:7220-7229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Komarnitsky, P., E. J. Cho, and S. Buratowski. 2000. Different phosphorylated forms of RNA polymerase II and associated mRNA processing factors during transcription. Genes Dev. 14:2452-2460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krum, S. A., G. A. Miranda, C. Lin, and T. F. Lane. 2003. BRCA1 associates with processive RNA polymerase II. J. Biol. Chem. 278:52012-52020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Larochelle, S., J. Chen, R. Knights, J. Pandur, P. Morcillo, H. Erdjument-Bromage, P. Tempst, B. Suter, and R. P. Fisher. 2001. T-loop phosphorylation stabilizes the CDK7-cyclin H-MAT1 complex in vivo and regulates its CTD kinase activity. EMBO J. 20:3749-3759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee, T. I., and R. A. Young. 2000. Transcription of eukaryotic protein-coding genes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 34:77-137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.MacLachlan, T. K., K. Somasundaram, M. Sgagias, Y. Shifman, R. J. Muschel, K. H. Cowan, and W. S. El-Deiry. 2000. BRCA1 effects on the cell cycle and the DNA damage response are linked to altered gene expression. J. Biol. Chem. 275:2777-2785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mallouk, Y., M. Vayssier-Taussat, J. V. Bonventre, and B. S. Polla. 1999. Heat shock protein 70 and ATP as partners in cell homeostasis. Int. J. Mol. Med. 4:463-474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manke, I. A., D. M. Lowery, A. Nguyen, and M. B. Yaffe. 2003. BRCT repeats as phosphopeptide-binding modules involved in protein targeting. Science 302:636-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Marshall, N. F., and D. H. Price. 1995. Purification of P-TEFb, a transcription factor required for the transition into productive elongation. J. Biol. Chem. 270:12335-12338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Monteiro, A. N. 2002. Participation of BRCA1 in the DNA repair response via transcription. Cancer Biol. Ther. 1:187-188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Monteiro, A. N., A. August, and H. Hanafusa. 1996. Evidence for a transcriptional activation function of BRCA1 C-terminal region. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:13595-13599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nadeau, G., N. Boufaied, A. Moisan, K. M. Lemieux, C. Cayanan, A. N. Monteiro, and L. Gaudreau. 2000. BRCA1 can stimulate gene transcription by a unique mechanism. EMBO Rep. 1:260-265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.O'Brien, K. A., S. J. Lemke, K. S. Cocke, R. N. Rao, and R. P. Beckmann. 1999. Casein kinase 2 binds to and phosphorylates BRCA1. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 260:658-664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Oelgeschlager, T. 2002. Regulation of RNA polymerase II activity by CTD phosphorylation and cell cycle control. J. Cell Physiol. 190:160-169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ohkuma, Y., S. Hashimoto, C. K. Wang, M. Horikoshi, and R. G. Roeder. 1995. Analysis of the role of TFIIE in basal transcription and TFIIH-mediated carboxy-terminal domain phosphorylation through structure-function studies of TFIIE-α. Mol. Cell. Biol. 15:4856-4866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Okamoto, T., S. Yamamoto, Y. Watanabe, T. Ohta, F. Hanaoka, R. G. Roeder, and Y. Ohkuma. 1998. Analysis of the role of TFIIE in transcriptional regulation through structure-function studies of the TFIIEbeta subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 273:19866-19876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paull, T. T., D. Cortez, B. Bowers, S. J. Elledge, and M. Gellert. 2001. Direct DNA binding by Brca1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:6086-6091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ptashne, M., and A. Gann. 1997. Transcriptional activation by recruitment. Nature 386:569-577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ratner, J. N., B. Balasubramanian, J. Corden, S. L. Warren, and D. B. Bregman. 1998. Ultraviolet radiation-induced ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of the large subunit of RNA polymerase II. Implications for transcription-coupled DNA repair. J. Biol. Chem. 273:5184-5189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rickert, P., J. L. Corden, and E. Lees. 1999. Cyclin C/CDK8 and cyclin H/CDK7/p36 are biochemically distinct CTD kinases. Oncogene 18:1093-1102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rossignol, M., I. Kolb-Cheynel, and J. M. Egly. 1997. Substrate specificity of the cdk-activating kinase (CAK) is altered upon association with TFIIH. EMBO J. 16:1628-1637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Scully, R., S. F. Anderson, D. M. Chao, W. Wei, L. Ye, R. A. Young, D. M. Livingston, and J. D. Parvin. 1997. BRCA1 is a component of the RNA polymerase II holoenzyme. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 94:5605-5610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Solomon, M. J., J. W. Harper, and J. Shuttleworth. 1993. CAK, the p34cdc2 activating kinase, contains a protein identical or closely related to p40MO15. EMBO J. 12:3133-3142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Somasundaram, K. 2003. Breast cancer gene 1 (BRCA1): role in cell cycle regulation and DNA repair—perhaps through transcription. J. Cell Biochem. 88:1084-1091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Somasundaram, K., H. Zhang, Y. X. Zeng, Y. Houvras, Y. Peng, G. S. Wu, J. D. Licht, B. L. Weber, and W. S. El-Deiry. 1997. Arrest of the cell cycle by the tumour-suppressor BRCA1 requires the CDK-inhibitor p21WAF1/CiP1. Nature 389:187-190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sun, X., Y. Zhang, H. Cho, P. Rickert, E. Lees, W. Lane, and D. Reinberg. 1998. NAT, a human complex containing Srb polypeptides that functions as a negative regulator of activated transcription. Mol. Cell 2:213-222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Talukder, A. H., S. K. Mishra, M. Mandal, S. Balasenthil, S. Mehta, A. A. Sahin, C. J. Barnes, and R. Kumar. 2003. MTA1 interacts with MAT1, a cyclin-dependent kinase-activating kinase complex ring finger factor, and regulates estrogen receptor transactivation functions. J. Biol. Chem. 278:11676-11685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wallenfang, M. R., and G. Seydoux. 2002. cdk-7 is required for mRNA transcription and cell cycle progression in Caenorhabditis elegans embryos. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:5527-5532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Welcsh, P. L., M. K. Lee, R. M. Gonzalez-Hernandez, D. J. Black, M. Mahadevappa, E. M. Swisher, J. A. Warrington, and M. C. King. 2002. BRCA1 transcriptionally regulates genes involved in breast tumorigenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 99:7560-7565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Whitmarsh, A. J., and R. J. Davis. 2001. Analyzing JNK and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase activity. Methods Enzymol. 332:319-336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Williams, R. S., D. Chasman, D. Hau, B. Hui, A. Lau, and J. N. Glover. 2003. Detection of protein folding defects caused by BRCA1-BRCT truncation and missense mutations. J. Biol. Chem. 278:53007-53016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Williams, R. S., R. Green, and J. N. Glover. 2001. Crystal structure of the BRCT repeat region from the breast cancer-associated protein BRCA1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8:838-842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Williamson, E. A., F. Dadmanesh, and H. P. Koeffler. 2002. BRCA1 transactivates the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27(Kip1). Oncogene 21:3199-3206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Xu, X., T. Nakano, S. Wick, M. Dubay, and L. Brizuela. 1999. Mechanism of Cdk2/Cyclin E inhibition by p27 and p27 phosphorylation. Biochemistry 38:8713-8722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yamane, K., and T. Tsuruo. 1999. Conserved BRCT regions of TopBP1 and of the tumor suppressor BRCA1 bind strand breaks and termini of DNA. Oncogene 18:5194-5203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Yankulov, K. Y., and D. L. Bentley. 1997. Regulation of CDK7 substrate specificity by MAT1 and TFIIH. EMBO J. 16:1638-1646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yu, X., C. C. Chini, M. He, G. Mer, and J. Chen. 2003. The BRCT domain is a phospho-protein binding domain. Science 302:639-642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Yudkovsky, N., J. A. Ranish, and S. Hahn. 2000. A transcription reinitiation intermediate that is stabilized by activator. Nature 408:225-229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zawel, L., H. Lu, L. J. Cisek, J. L. Corden, and D. Reinberg. 1993. The cycling of RNA polymerase II during transcription. Cold Spring Harbor Symp. Quant. Biol. 58:187-198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhang, J., and J. L. Corden. 1991. Phosphorylation causes a conformational change in the carboxyl-terminal domain of the mouse RNA polymerase II largest subunit. J. Biol. Chem. 266:2297-2302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]