Abstract

EDD is the mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila melanogaster hyperplastic disc gene (hyd), which is critical for cell proliferation and differentiation in flies through regulation of hedgehog and decapentaplegic signaling. Amplification and overexpression of EDD occurs frequently in several cancers, including those of the breast and ovary, and truncating mutations of EDD are also observed in gastric and colon cancer with microsatellite instability. EDD has E3 ubiquitin ligase activity, is involved in regulation of the DNA damage response, and may control hedgehog signaling, but a definitive biological role has yet to be established. To investigate the role of Edd in vivo, gene targeting was used to generate Edd knockout (EddΔ/Δ) mice. While heterozygous mice had normal development and fertility, no viable Edd-deficient embryos were observed beyond E10.5, with delayed growth and development evident from E8.5 onward. Failed yolk sac and allantoic vascular development, along with defective chorioallantoic fusion, were the primary effects of Edd deficiency. These extraembryonic defects presumably compromised fetal-maternal circulation and hence efficient exchange of nutrients and oxygen between the embryo and maternal environment, leading to a general failure of embryonic cell proliferation and widespread apoptosis. Hence, Edd has an essential role in extraembryonic development.

EDD is the mammalian ortholog of the Drosophila melanogaster hyperplastic disc gene (hyd) (5). Hyd has a critical role in control of cell proliferation during development. Null mutations of hyd are lethal at the pupal or larval stage, whereas temperature-sensitive point mutations cause imaginal disc hyperplasia or male and female infertility (24). Human EDD mRNA is ubiquitously expressed (5), and within the testis rat Edd (RAT100) is expressed specifically in germ cells and precisely regulated during spermatogenesis (27, 29). EDD family genes (Edd, hyd, and Rat100) encode highly conserved, large, predominantly nuclear proteins (approximately 300 kDa) that contain a number of putative protein-protein interaction domains, suggesting multiple functions (14).

EDD appears to function as an E3 ubiquitin protein ligase via its conserved carboxy-terminal HECT (for homologous to E6-AP carboxy terminus) domain. Indeed, a number of EDD-associating proteins have recently been described whose binding is mediated via the HECT domain. Calcium- and integrin-binding protein (CIB/KIP/calmyrin) was identified as a binding partner of EDD in our laboratory (14). CIB associates with a number of proteins, including integrin αIIbβ3 (28), the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase (39), and the polo-like kinases PLK-1 and PLK-3 (33, 40). DNA topoisomerase IIβ-binding protein 1 (TopBP1) has also been identified as an EDD-interacting protein (16). TopBP1 was ubiquitinylated by EDD in vitro and degraded by the proteasome, but this degradation diminished following X irradiation of cells, suggesting that EDD may modulate TopBP1 in the DNA damage response. A number of unidentified high-molecular-weight proteins are ubiquitinylated by RAT100, and this function may be important for male germ cell development (29). Like some other HECT domain proteins (e.g., E6-AP and Rsp5), EDD is also a coactivator of progesterone receptor transcriptional activity (14). Interestingly, EDD was originally identified as a progestin-regulated gene in T-47D human breast cancer cells (5), indicating a possible positive-feedback loop which might be of significance in steroid-dependent tissues.

In addition to a HECT domain, EDD possesses a RING-like zinc finger domain and a UBA domain, which have both been identified as protein-protein interaction domains in other proteins involved in ubiquitinylation cascades (14, 21, 38). Another protein-protein interaction domain of interest is the poly(A)-binding protein (PABP)-like domain near the C terminus, which mediates binding to Paip1 (PABP-interacting protein). The proximity of this domain to the HECT domain suggests a possible contribution to the specificity of the ubiquitin ligase activity of EDD in regulation of PABP function during protein synthesis (9). Further complicating the identification of a definitive biological role for EDD, it has recently been identified as an in vivo substrate of ERK2 (11).

Although several biochemical activities have been demonstrated for EDD in vitro, its precise role in vivo has yet to be established. Ubiquitin-mediated proteolysis is essential for the regulation of many key cellular pathways, and the likely involvement of EDD in regulation of DNA damage responses, progesterone receptor signaling, and protein synthesis suggests several potential roles in the control of cellular proliferation. The tumor suppressor properties of Hyd suggest the potential involvement of EDD in tumorigenesis. A recent study reported that EDD was one of the most frequently mutated loci of the 154 examined in microsatellite-unstable gastric and colorectal cancers. Truncating mutations of EDD (resulting from coding-region frameshift mutations) were observed in 27.8 and 23.3% of gastric and colorectal cancers, respectively (26). In contrast, we have extensive data from other tumor types that may be more consistent with an oncogenic role for EDD. The EDD locus was identified as a specific area of amplification in ovarian cancer, hepatocellular carcinoma, breast cancer, and metastatic melanoma. Furthermore, overexpression of EDD was observed in a significant proportion of breast and ovarian tumors (6, 12). Hence, there is strong evidence that EDD may play a role in tumorigenesis, although the nature of this role is not clear. We therefore sought to assess the functional role of EDD in normal mammalian development by generation of a knockout mouse model.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cloning and targeted disruption of murine Edd.

The murine Edd gene was cloned from a 129SV/J lambda FIX II mouse genomic library (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) and a 129SV/J BAC mouse ES cell library (Genome Systems, St. Louis, Ma). Isolated clones were mapped to determine intron/exon boundaries and restriction sites. A targeting vector was designed to delete 3.4 kb of Edd genomic DNA containing 60 bp of exon 1 (amino acids 2 to 21) and approximately 3.3 kb from the following intron and to replace it with a 6.5-kb β-galactosidase (βGal)-green fluorescent protein (GFP)-Neor expression cassette (see Fig. 1A). The targeting vector was linearized at the unique NotI site, and electroporated into 129SV/J embryonic stem (ES) cells, and neomycin-resistant (Neor) clones were isolated and screened for disruption of the Edd gene by Southern blotting. DNA prepared from ES cell clones was digested with BamHI, transferred to Zeta Probe membrane (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, Calif.), and subjected to hybridization with the 0.4-kb HindIII-BamHI Edd probe (see Fig. 1B). Targeted ES cell clones were used to generate chimeric mice by injection into blastocyst stage C57BL/6 embryos. Chimeras were backcrossed with C57BL/6 mice to generate F1 animals heterozygous for the mutated Edd allele (EddΔ/−), and germ line transmission was confirmed by Southern blot analysis. ES cell transfection and screening, chimera generation, and initial backcrossing were performed by Ozgene P/L (Perth, Australia).

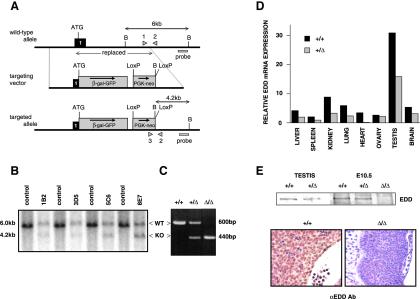

FIG. 1.

Targeted disruption of mouse Edd. (A) Structure of the WT Edd locus (top), targeting vector (middle), and mutated locus following homologous recombination (bottom). Edd exon 1 is indicated as a black box, with the position of the ATG codon shown. BamHI restriction sites are denoted by B. Genotyping was performed by PCR using primers, 1, 2 and 3 (arrowheads) and by Southern blot analysis with a 3′ probe as shown. Expected sizes of PCR products and BamHI fragments that hybridize with the probe on Southern analysis are indicated. (B) Southern blot analysis of genomic DNA from targeted ES cell clones. Genomic DNA from four neomycin-resistant ES cell clones, 1B2, 3D5, 5C6, and 8E7, was digested with BamHI and hybridized with the 3′ probe. The 6.0-kb fragment corresponding to the WT allele (top) and the 4.2-kb fragment corresponding to the mutated (KO) allele (bottom) are indicated. (C) PCR genotype analysis of E10.5 embryos. DNA samples were subjected to PCR using primers 1, 2, and 3. PCR amplification of the WT allele by primers 1 and 2 produces a 600-bp fragment (top), and PCR amplification of the KO allele by primers 2 and 3 produces a 440-bp fragment (bottom). (D) Northern blot analysis of tissues from WT and Edd+/Δ mice. Total RNA was extracted and hybridized to a 32P-labeled mouse Edd cDNA probe. Densitometry was performed, and values were corrected for loading by comparison to the blot after reprobing with GAPDH cDNA. (E) Western blot analysis and IHC showing EDD expression in WT (+/+), heterozygote (+/Δ), and knockout (Δ/Δ) tissues. EDD Western blots were performed with lysates from testes of adult WT (+/+) and Edd+/Δ (+/Δ) mice and from E10.5 WT, Edd+/Δ, and EddΔ/Δ (Δ/Δ) embryos. IHC was performed on E9.5 WT (left panel) and E9.5 knockout (Δ/Δ, right panel) embryo sections, with a region of neural epithelium shown.

Tail biopsy or embryo yolk sac DNA was routinely genotyped by PCR using 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 60°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 45 s, with the following primers (see Fig. 1A): primer 1, 5′-CTAGGGAAGTGCATTAGGTAAG-3′; primer 2, 5′-TAAGGGCAGGTGTTCCTCTG-3′; and primer 3, 5′-GTACTGTGGTTTCCAAATGTGTCAG-3′.

Northern blotting.

Total RNA was extracted from frozen tissues by homogenization with a polytron in TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, Calif.). Chloroform extraction and isopropanol precipitation of the RNA was performed as specified by the manufacturer and further purified using an RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Clifton Hill, Australia). Northern blotting was performed as described elsewhere (17). Blots were hybridized to a [32P]dCTP-labeled mouse Edd cDNA fragment or mouse glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) cDNA as a loading control.

Western blotting.

Protein was isolated from tissues and whole embryos in lysis buffer (50 mM HEPES [pH 7.5], 150 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 1% Triton X-100, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM pyrophosphate, 20 mM NaF, 1 mM dithiothreitol) containing complete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche Diagnostics Australia P/L, Castle Hill, Australia). Protein concentrations were determined using a protein assay (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Following sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE), proteins were transferred to as Immobilon-P membrane (Millipore, Sydney, Australia) in prechilled Tris-glycine transfer buffer plus 0.02% SDS at 85 V for 1 h 15 min or 30 V overnight. Nonspecific binding sites on the membrane were blocked in 5% skim milk powder in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)-0.05% Tween for 1 h at room temperature, and the membrane was incubated in primary antibody EDD M19 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.), diluted in 1% bovine serum albumin-0.05% Tween-TBS for 1 h at room temperature or 4°C overnight, washed, and incubated for 1 h in horseradish peroxidase-conjugated protein G (Zymed Laboratories Inc., San Francisco, Calif.). Binding was detected with enhanced chemiluminescence substrates (Pierce, Rockford, Ill.).

Embryo dissection and genotyping.

Edd+/Δ mice were bred to obtain wild-type (Edd+/+), heterozygote (Edd+/Δ), and homozygous mutant (EddΔ/Δ) embryos. Mice were kept on a 12-h light-dark cycle, and the morning of the day on which a vaginal plug was detected was designated E0.5. Embryos were dissected from the uterus in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and yolk sacs were kept for genotyping. Yolk sacs were digested overnight at 37°C in TP lysis buffer (50 mM Tris [pH 7.5], 0.1 M NaCl, 0.5% SDS, 5 mM EDTA) containing 5 μg of proteinase K (Promega Corp., Annandale, Australia) and boiled for 5 min before being subjected to PCR (as above).

Histological analysis and immunohistochemistry.

Embryos dissected in PBS were fixed for 1 h in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA), dehydrated, and embedded in paraffin, and 4-μm sections were cut and mounted on Superfrost Plus adhesion slides (Lomb Scientific P/L, Taren Point, Australia). For histological analysis, sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin. For EDD immunohistochemistry (IHC), sections were dewaxed and rehydrated before being unmasked in target retrieval solution (high pH; Dako, Botany, Australia). Sections were incubated for 30 min with 1:200-diluted anti-EDD (M19) antibody (Santa Cruz Biotechnology) antibody and then for 15 min with 1:200-diluted biotinylated horse anti-goat antibody (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, Calif.). A streptavidin-biotin peroxidase detection system was used as specified by the manufacturer instructions (Vectastain Elite kit; Vector Laboratories) with 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB) as substrate. Counterstaining was performed with Whitlock's hematoxylin (BDH Laboratory Supplies, Poole, United Kingdom). For IHC detection of bromodeoxyuridine (BrdU) in labeled sections, antigen retrieval was performed using target retrieval solution (pH 6.0; Dako) before the sections were incubated with biotinylated anti-BrdU (Dako) at 1:50 for 30 min. Detection and counterstaining were identical to those used for EDD IHC. To analyze apoptosis in embryo sections, IHC detection of cleaved (active) caspase-3 was performed. Sections were dewaxed and rehydrated before antigen retrieval in 10 mM trisodium citrate buffer. Embryo sections were incubated with 1:6,000-diluted anti-active caspase-3 antibody (R & D Systems, Minneapolis, Minn.) for 30 min and then with 1:300-diluted biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antiserum (Amersham Biosciences, Little Chalfort, Buckinghamshire, England) for 15 min. Detection and counterstaining were identical to those used for EDD IHC. Stained cells were counted and scored by two blinded independent observers.

For whole-mount immunochemistry, embryos were fixed in 1% PFA and processed using standard protocols (8, 20). Anti-platelet endothelial cell adhesion molecule (PECAM) primary antibody (Pharmingen no. 553370) was diluted at 1:150, and peroxidase-conjugated anti-goat immunoglobulin G (Jackson Immunochemical no. 112-035-003) was used as a secondary reagent.

Cell proliferation assay.

Cellular proliferation in developing embryos was assayed by measuring the incorporation of BrdU. Pregnant females at E8.5, E9.5, and E10.5 were injected intraperitoneally with 100 μg of BrdU per g 1 h before sacrifice. Embryos were collected, fixed in 4% PFA for 1 h, and processed for IHC as above. Alternatively, embryos were dissected in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) and labeled in vitro by incubation in 100 μg of BrdU/ml of DMEM for 2 h at 37°C prior to processing as above. Slides were scored by two independent observers, and a mitotic index was calculated as the percentage of total cells with BrdU-positive nuclei.

TUNEL assay.

Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated dUTP-biotin nick end labeling (TUNEL) staining was used to detect apoptotic DNA fragmentation and quantify the apoptotic cells in sections of E8.5 to E10.5 embryos. Staining was performed using the DeadEnd colorimetric TUNEL system (Promega) as specified by the manufacturer. Briefly, slides were dewaxed and rehydrated before the tissue was pretreated in 20 μg of proteinase K per ml for 10 min at 37°C. After incubation for 10 min at room temperature in equilibration buffer, sections were labeled with TUNEL reaction mixture in a humidified chamber for 60 min at 37°C. Biotinylated nucleotides incorporated into DNA fragments were detected using 1:500 horseradish peroxidase-labeled streptavidin and a DAB substrate. Positive control slides were prepared by treating cells, after permeabilization, with 0.5 μg of DNase I in DNase I buffer (40 mM Tris HCl [pH 7.9], 10 mM NaCl, 6 mM MgCl2, 10 mM CaCl2) and staining them as above.

Nucleotide sequence accession number.

The complete cDNA sequence of murine EDD has been deposited in GenBank under accession number AY550908.

RESULTS

Generation of EddΔ/Δ mice.

Disruption of Edd was achieved by in-frame insertion of a 6.5-kb βGal-GFP-Neor expression cassette (Fig. 1A). This replacement was designed to produce an effectively null Edd allele and express a βGal-GFP fusion protein under control of the normal Edd gene upstream regulatory elements. Neomycin-resistant ES clones were isolated and screened for disruption of the Edd gene by Southern blot analysis (Fig. 1B). Restriction of wild-type (WT) genomic DNA with BamHI produced a 6-kb fragment. Following homologous recombination with the targeting vector and replacement of the 5′ BamHI site, a smaller (4.2-kb) hybridizing fragment was generated following restriction. Therefore, a correctly targeted ES cell clone produced 6- and 4.2-kb fragments following digestion with BamHI, representing the WT type and mutated alleles, respectively (Fig. 1B). Two independently targeted ES cell clones (1B2 and 5C6) were used to generate chimeric mice, and following backcrossing with C57BL/6 mice, F1 animals were again analyzed by Southern blotting to confirm germ line transmission of the mutated Edd allele. Routine genotyping of adult tail and embryo yolk sac DNA by PCR generated an amplicon of 600 bp from WT DNA (using primers 1 and 2). However, the primer 1 recognition sequence is deleted following insertion of the targeting vector, and hence the mutated allele is detected as a 440-bp amplicon (using primers 2 and 3) (Fig. 1C).

Northern blot analysis showed expression of Edd mRNA in a wide range of WT adult mouse tissues, similar to the expression pattern of human EDD (14). Reduced Edd mRNA expression was observed in most tissues analyzed from heterozygous (Edd+/Δ) animals (Fig. 1D). However, Western blot analysis showed only slightly decreased Edd protein expression in Edd+/Δ adult testis and E10.5 embryonic tissue (Fig. 1E). Edd expression was not detected in tissue from EddΔ/Δ E10.5 embryos by either Western blotting or IHC (Fig. 1E), confirming the efficacy of the targeting strategy. Edd was detectable by IHC in most cells of developing WT embryos. Neither GFP nor LacZ expression was detectable in Edd+/Δ or EddΔ/Δ embryos, most probably due to either very low β-Gal/GFP expression or production of a nonfunctional fusion protein.

Phenotype of heterozygous (Edd+/Δ) mice.

Both male and female Edd+/Δ mice on a mixed 129SV/J × C57BL/6 background were allowed to grow for 80 weeks and showed no obvious phenotype, with comparable fertility and growth rates to those of WT controls. No difference in tumor incidence was observed between WT and Edd+/Δ mice.

Edd deficiency results in midgestation embryonic death.

When Edd+/Δ mice were interbred, homozygous mutant (EddΔ/Δ) animals were absent from 274 offspring analyzed, indicating that complete Edd deficiency (homozygosity for the Edd null mutation) causes embryonic death (Table 1). To characterize the developmental stage at which Edd deficiency caused embryonic death we analyzed embryos from heterozygous intercrosses at various stages of gestation (Table 1). Mendelian ratios of WT, Edd+/Δ, and EddΔ/Δ embryos were observed up to E10.5. No viable EddΔ/Δ embryos were observed beyond E10.5. Some EddΔ/Δ embryos were present in litters at E11.5, but these were partially resorbed and scored as nonviable. A number of empty decidua were observed at E11.5 to E12.5, and these may have arisen from resorption of EddΔ/Δ embryos at earlier stages of gestation. These data demonstrate that homozygosity for the Edd null mutation results in embryonic death before E11.5 and indicate that Edd is essential for postimplantation embryonic development.

TABLE 1.

Genotypic analysis of offspring from Edd+/Δ intercrossesa

| Genotype | No. (%) of embryos observed atb:

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E8.5 | E9.5 | E10.5 | E11.5 | E12.5 | Weaning | |

| WT | 19 (32) | 17 (25) | 39 (27) | 9 (27) | 9 (31) | 92 (34) |

| Edd+/Δ | 27 (46) | 38 (57) | 64 (44) | 15 (46) | 20 (69) | 182 (66) |

| EddΔ/Δ | 13 (22) | 12 (18) | 42 (29) | 9c (27) | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 59 | 67 | 145 | 33 | 29 | 274 |

Embryos were collected at E8.5 to E12.5 from Edd+/Δ intercrosses, and genotypes were determined by PCR amplification using DNA extracted from the whole embryo or from the yolk sac. Pups at weaning (3 weeks of age) were genotyped using DNA extracted from tail biopsy specimens, using the same PCR protocol.

Numbers in parentheses indicate the percentage of total offspring. By E12.5 and at weaning no EddΔ/Δ embryos were observed, indicating embryonic death of the Edd knockout phenotype.

Embryos were partially resorbed and scored as nonviable.

Heterozygous mice and EddΔ/Δ embryos generated from the two independently targeted ES cell lines showed identical phenotypes (data not shown). Furthermore, no difference was observed in EddΔ/Δ embryos following excision of the neomycin resistance (Neor) gene from the targeted allele by crossing EddΔ/+ mice with mice transgenic for Cre recombinase.

The EddΔ/Δ phenotype is p53 independent.

Given the potential role of Edd in the DNA damage response (14, 16) and the ability of p53 deficiency to partially rescue lethal phenotypes of knockout models of other genes involved in DNA damage response (e.g., Brca1, and Brca2), we attempted to ascertain whether a genetic relationship exists between Edd and p53. Edd+/Δ mice were crossed with mice heterozygous for a truncating mutation in p53 (18), and Edd/p53 double heterozygous animals were subsequently produced. Embryos from intercrosses of these double heterozygotes were examined, and no difference was observed in the survival of EddΔ/Δ embryos on a p53Δ/Δ background (Table 2). EddΔ/Δ/p53Δ/Δ embryos at E10.5 showed similar morphology to EddΔ/Δ/p53+/+ embryos, indicating that the molecular defects leading to embryonic death in EddΔ/Δ embryos are p53 independent.

TABLE 2.

Genotypic analysis of offspring from Edd+/Δ/p53+/Δ double heterozygous intercrossesa

| Genotype | No. of embryos observed at:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|

| E9.5 | E10.5 | E11.5 | |

| p53+/+ | |||

| Edd+/+ | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Edd+/Δ | 3 | 8 | 4 |

| EddΔ/Δ | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| p53+/Δ | |||

| Edd+/+ | 4 | 4 | 3 |

| Edd+/Δ | 4 | 12 | 11 |

| EddΔ/Δ | 1 | 4 | 1 |

| p53Δ/Δ | |||

| Edd+/+ | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| Edd+/Δ | 2 | 4 | 2 |

| EddΔ/Δ | 1 | 2 | 6b |

| Total | 22 | 40 | 32 |

Edd+/Δ/p53+/Δ mice were mated, and embryos were collected at E9.5 to E11.5. Genotypes were determined by PCR using DNA extracted from the whole embryo or from the yolk sac. Double-knockout EddΔ/Δ/p53Δ/Δ embryos were observed at all stages but were partially resorbed at E11.5 and displayed a similar phenotype to EddΔ/Δ embryos, indicating that EddΔ/Δ lethality is p53 independent.

Embryos were partially resorbed and scored as nonviable.

Morphology of EddΔ/Δ embryos.

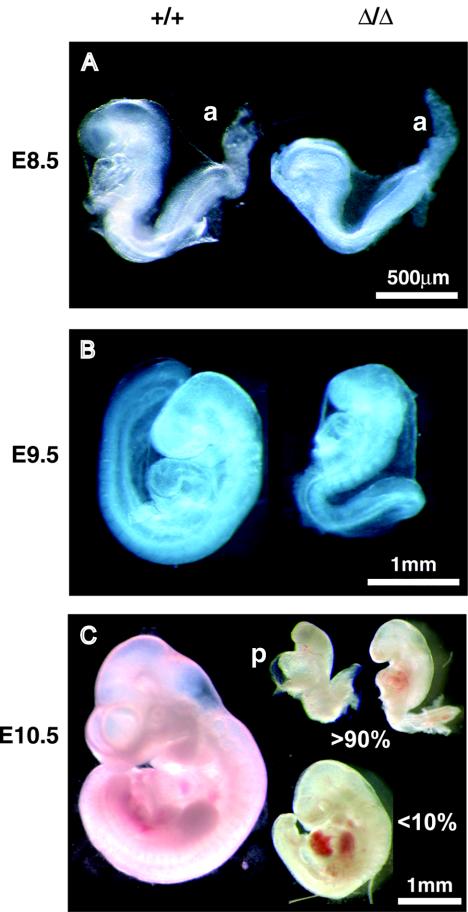

At E8.5, EddΔ/Δ embryos were clearly developmentally retarded, lagging at least 0.5 day behind the development of WT and Edd+/Δ littermates (Fig. 2A). By E9.5 and E10.5, EddΔ/Δ embryos displayed severe growth defects, the most apparent being significant size reduction in all embryos and an absence of turning in >90% of embryos (Fig. 2B and C). In addition, the head and branchial arches were significantly underdeveloped. EddΔ/Δ embryos appeared to contain far less neural epithelium than WT embryos, and the epithelial structure was disorganized. Defects were also apparent in EddΔ/Δ extraembryonic tissue, with immature allantois and pale, fragile yolk sacs compared to those of WT littermates (described in detail below). In short, defects in EddΔ/Δ embryonic tissue were widespread and did not appear to be restricted to a specific organ system or cell type.

FIG. 2.

Morphology of WT and knockout (EddΔ/Δ) embryos at E8.5 to E10.5. Photographs showing freshly dissected WT embryos and EddΔ/Δ embryos are presented. (A) Clear growth retardation is obvious in EddΔ/Δ embryos compared to WT embryos at E8.5. (B) From E9.5 onward, EddΔ/Δ embryos are markedly smaller than WT embryos, and almost all fail to turn, a process which occurs in WT embryos around E9. (C) A number of E10.5 EddΔ/Δ embryos are shown, to demonstrate the range of morphologies observed. Many EddΔ/Δ embryos with pericardial effusion (p) at E10.5 were observed, an indication of cardiovascular failure. Despite the obvious presence of an allantois (a) at E8.5, chorioallantoic fusion does not occur in the majority (>90%) of EddΔ/Δ embryos. In the few EddΔ/Δ embryos that exhibit chorioallantoic fusion, development appears to proceed to a slightly more advanced stage, with turning occasionally observed. However, these embryos are still significantly smaller and less well developed than WT littermates and do not survive beyond E10.5.

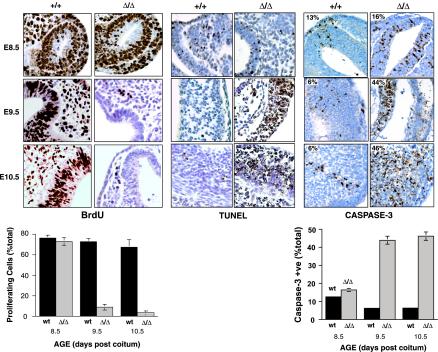

Cellular proliferation in developing embryos was examined by measuring BrdU incorporation into DNA during S phase. At E8.5, the earliest stage at which a clear defect is observed in EddΔ/Δ embryos, there was no significant difference in proliferation between WT (76% ± 2.9%) and EddΔ/Δ (73% ± 3.8%) embryos (Fig. 3). By E9.5, a marked decrease in cell proliferation was observed in EddΔ/Δ embryos; by E10.5, and almost no proliferation was detected (Fig. 3). No significant difference was observed in the number of TUNEL-positive nuclei between WT and EddΔ/Δ embryos at E8.5 (Fig. 3). However, significantly larger numbers of TUNEL-positive cells were visible in EddΔ/Δ embryos at E9.5 and E10.5 (Fig. 3). IHC staining for the cleaved (i.e., active) form of caspase-3 was also performed, and, consistent with TUNEL staining, no significant difference was observed between WT and EddΔ/Δ embryos at E8.5 (13 and 16%, respectively). However, significantly higher staining for active caspase-3 was observed in EddΔ/Δ embryos from E9.5 onward (44 and 6% for EddΔ/Δ and WT, respectively, at E9.5; 46 and 6%, respectively, at E10.5) (Fig. 3). Hence, the retarded development observed at E9.5 to E10.5 results from a combination of decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis throughout the entire embryo. However, these defects are almost certainly secondary effects resulting from inadequate nutrient and oxygen exchange between fetal and maternal circulations due to the critical defects observed in extraembryonic tissues (described below).

FIG. 3.

Cell proliferation and apoptosis in WT and EddΔ/Δ embryos at E8.5 to E10.5. BrdU incorporation was used to measure cell proliferation in WT and EddΔ/Δ embryos, and BrdU positive cells were detected by IHC. Cells positive for BrdU stain with brown nuclei. While there are equivalent numbers of proliferating cells in EddΔ/Δ and WT embryos at E8.5, by E9.5 the majority of cells in EddΔ/Δ embryos have stopped proliferating and do not incorporate BrdU. Apoptosis was measured in embryo sections by using the TUNEL assay and by staining for active caspase-3. TUNEL-positive nuclei and cells in which active caspase-3 is present stained brown. At E8.5, similar levels of TUNEL and caspase-3 staining can be seen in both WT (+/+) and EddΔ/Δ (Δ/Δ) embryos. At E9.5 and 10.5, EddΔ/Δ embryos show dramatically increased levels of TUNEL and caspase-3 staining compared to WT embryos, which have very few stained cells. The graph shows the percentage of stained cells (mean and standard error [n = 3]). Sections of cranial tissue illustrating neural epithelium and mesenchyme are shown as representative of the whole embryo.

Defective yolk sac vascularization in EddΔ/Δ embryos.

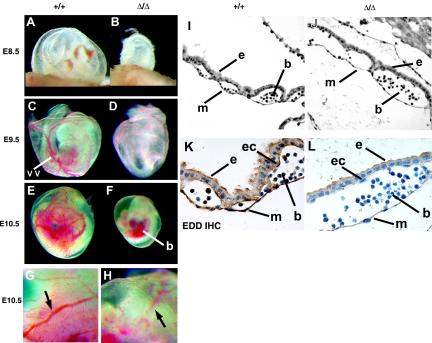

Many EddΔ/Δ embryos were observed with pericardial effusion at E10.5 (Fig. 2C), an indication of osmotic imbalance and a common manifestation of disrupted yolk sac blood flow (7). At E8.5, a primitive vasculature (containing blood cells) was clearly visible in the yolk sac of WT embryos (Fig. 4A) whereas EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs were pale and fragile (Fig. 4B). The large vitelline vessel and numerous smaller vessels were clearly seen in WT yolk sacs at E9.5 (Fig. 4C). In contrast, numerous small pools of blood cells were present in EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs, with no organized vessel formation (Fig. 4D). At E10.5, numerous large, branching vessels were present in WT yolk sacs (Fig. 4E and G) whereas only primitive vascular development was apparent in EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs. Vessels in EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs were smaller and disorganized, with many dead-ended sprouts (Fig. 4F and H). Hence, it appears that vasculogenesis was occurring in the the yolk sac in the absence of Edd but that angiogenesis may have been impaired.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of yolk sac vascular development. (A to F) Morphology of E8.5 to E10.5 WT and EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs. EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs display significantly less vasculature than their WT littermates, suggesting a defect in yolk sac vascular development. The large vitelline vessel (vv) is clearly visible in the WT yolk sac at E9.5 (C), whereas EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs at the same stage appear blistered, with no organized vessel formation. In addition, blood pooling (b) can be seen within the EddΔ/Δ embryos at E10.5 (F). (G) Large, well-organized vessels (arrow) are visible in WT yolk sacs at E10.5 under high magnification. (H) Some primitive vascular development is apparent in EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs, but these vessels appear smaller and disorganized. (I to L) Histological analysis of E9.0 yolk sacs shows a clear difference in morphology between WT and EddΔ/Δ tissue. Individual vessels are clearly visible in WT tissue (I), whereas the visceral endoderm (e) and mesoderm (m) layers are more widely separated in EddΔ/Δ tissue (J). IHC staining indicates the expression of Edd in cells of both the visceral endoderm and mesoderm. Edd is also expressed in blood and hematopoietic cells (b) in the vessels (K). Endothelial cells (ec) are visible in EddΔ/Δ tissue (L).

Histological analysis of E8.5 to E9.5 yolk sacs showed a clear difference in morphology between WT and EddΔ/Δ tissue. Individual vessels were clearly visible in WT tissue, with numerous regularly spaced attachments between the visceral endoderm and mesoderm layers (Fig. 4I). Visceral endoderm and mesoderm were more widely separated in EddΔ/Δ tissue, with occasional attachments forming numerous large spaces that were sparsely populated with blood cells (Fig. 4J). Endothelial cells could be seen in sections from EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs. IHC staining showed expression of Edd in cells of both the visceral endoderm and mesoderm (Fig. 4K), supporting a role for Edd in yolk sac vascular development. Interestingly, Edd was also highly expressed in some primitive hematopoietic cells.

Failure of chorioallantoic fusion in EddΔ/Δ embryos.

Despite the presence of an allantois in EddΔ/Δ embryos at E8.5 (Fig. 5A), failure of chorioallantoic attachment was observed in more than 90% of EddΔ/Δ embryos. By E10.5, in the absence of fusion, the allantois of EddΔ/Δ embryos formed a large, blood-filled mass near the hindgut region, connected by a large blood vessel (Fig. 5A, arrowhead). On the few occasions when chorioallantoic attachment was observed in EddΔ/Δ embryos, the attachment was only weak and placentation was not observed. Development proceeded to a slightly more advanced stage in these embryos, with turning observed, but they were still significantly smaller and developmentally retarded compared to WT littermates and did not survive beyond E10.5 (Fig. 2).

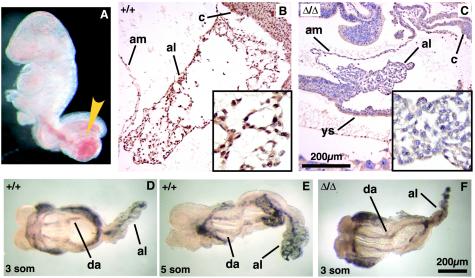

FIG. 5.

Histological analysis of allantoic development and vascularization. (A) In the absence of chorioallantoic fusion in EddΔ/Δ embryos, the allantois forms a large, blood-filled mass connected to a large blood vessel by E10.5 (yellow arrowhead). (B and C) IHC analysis of WT (B) and EddΔ/Δ (C) allantois at ∼E9.0, showing Edd expression throughout WT tissue. EddΔ/Δ tissue is relatively dense and lacks the numerous vessel lumen visible in the WT allantois (inset). (D to F) Whole-mount PECAM staining of WT (D and E) and EddΔ/Δ (F) embryos at E8.5 shows the presence of a well-defined vascular network in the WT allantois. Endothelial cells are present in the EddΔ/Δ allantois but do not form an organized vascular network. PECAM expression was observed in the dorsal aorta of both WT and EddΔ/Δ embryos. Abbreviations: am, amnion; al, allantois; ch, chorion; ys, yolk sac; da, dorsal aorta.

More detailed analysis at E8.5 showed that allantoic development was already compromised in the majority of EddΔ/Δ embryos prior to attachment with the chorion. Although the allantois initially extended normally in EddΔ/Δ embryos, it failed to expand and remained narrow and uneven (Fig. 5F). Histological sections showed that the tissue remained dense, without the numerous vessel lumens seen in WT littermates (Fig. 5B and C). Poor development of the allantoic vasculature was confirmed by whole-mount immunochemical analysis of PECAM expression, a marker of vascular endothelial cells. In the robust WT allantois, a central vessel running along the entire length was already evident by three somites, with numerous vessel branches then forming in a matter of hours (Fig. 5D and E). In stark contrast, only isolated islands of endothelial cells that failed to coalesce were observed in the allantois of EddΔ/Δ embryos (Fig. 5F). Supporting a role for Edd in allantoic development, IHC analysis showed that Edd is expressed throughout the developing allantois of E8.5 WT embryos (Fig. 5B). PECAM expression was observed in the two dorsal aortae of EddΔ/Δ embryos, suggesting that early development of the embryonic vasculature was normal in the absence of Edd. The intensity of PECAM expression in the yolk sac, however, was consistently reduced in EddΔ/Δ embryos at this stage.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that targeted disruption of the E3 ubiquitin ligase Edd gene in mice results in midgestation embryonic death, demonstrating a key role for Edd in mammalian development. Yolk sac vascular development and chorioallantoic fusion were severely compromised in Edd-deficient embryos. Accordingly, retarded embryonic growth was clearly visible in EddΔ/Δ embryos at E8.5, and from E9.5 onward there was a severe retardation of development compared with WT and Edd+/Δ littermates (Fig. 1).

Greatly reduced DNA synthesis, as determined by decreased BrdU incorporation, was observed in Edd-deficient embryos from E9.5 onward. This decreased cell proliferation in EddΔ/Δ embryos at E9.5 was accompanied by widespread caspase-3-mediated apoptosis. The combined effect of dramatically decreased cell proliferation and increased apoptosis manifests as severe defects in many of the developing organ systems of EddΔ/Δ embryos at E9.5 to E10.5 (Fig. 2). However, changes in cell proliferation and apoptosis appear to be secondary effects of Edd deficiency. Gross differences in morphology between WT and EddΔ/Δ embryos are already apparent from E8.5 onward, without any significant decrease in cell proliferation or increased apoptosis apparent at this stage in EddΔ/Δ embryos (Fig. 2).

The development of embryos during early organogenesis (E8.5 to E11.5) is critically dependent on the formation of functional yolk sac circulation and the establishment of a chorioallantoic placenta. The yolk sac consists of an outer endoderm and inner mesoderm layer, with EDD expressed in both of these. At E7.0, blood islands (lined with endothelium) form between the endoderm and mesoderm. These fuse to form a primary vascular plexus (vasculogenesis), which then undergoes remodeling (angiogenesis) to produce an extensive vascular network. At ∼E8.5, the yolk sac vasculature fuses with the embryonic vasculature, and until the chorioallantoic placenta is established the yolk sac functions as a primitive placenta. The chorioallantoic placenta develops following interaction between vascularized allantois and the chorionic plate (known as chorioallantoic fusion). If interaction does not occur or cannot be maintained, the fetal and maternal circulations do not come into contact. Failure to establish adequate fetal-maternal circulation prevents efficient exchange of nutrients and oxygen between the embryo and maternal environment and leads to embryonic death before E11.5 (7). Abnormal vasculogenesis or disrupted chorioallantoic fusion causes embryonic death around E10.5 in several other knockout mouse models (e.g., VCAM-1, α4 integrin, Brachyury, TGFβ1, Smad5, α5 integrin, and flt-1) (reviewed in reference 31). Many EddΔ/Δ embryos were observed with pericardial effusion, a classic hallmark of osmotic imbalance within the embryo and a common manifestation of disrupted yolk sac blood flow (7). Detailed examination showed that EddΔ/Δ yolk sacs had severe defects in vascular development. Endothelial cells were observed (Fig. 4J and L), but any vasculature that did form was disorganized. Edd was highly expressed in visceral mesoderm and was also detected in visceral endoderm, tissues with critical roles in primitive hematopoietic and vascular development (1).

Chorioallantoic attachment did not proceed in the large majority (>90%) of EddΔ/Δ embryos, and severe vascular defects were observed in the EddΔ/Δ allantois. Consequently, many of these embryos displayed a malformed bulbous allantois at later stages of development. Abnormal vascularization of the allantois is unlikely due to lack of contact with the chorion, since it has previously been shown that contact with the chorion is not required for vascularization (10). PECAM staining showed the presence of endothelial cells, but these failed to form a well-organized vascular network in EddΔ/Δ allantois. Defects in allantoic attachment and vasculogenesis preclude placental formation and prevent the formation of a functional umbilical circulation. Hence, nutrient deprivation caused by defective yolk sac and allantoic vascular development is the most likely primary cause of embryonic death in EddΔ/Δ embryos. This hypothesis could be tested by employing tetraploid rescue or through generation of conditional knockout animals in which Edd expression is disrupted only in embryonic tissue (19, 35).

The nature of the underlying molecular mechanisms disrupted by Edd deficiency poses a critical question. These mechanisms may well be complex since Edd is a very large protein with several functional domains, making it highly likely that Edd has multiple activities. Hence, the developmental failure of Edd-deficient embryos may be the result of an accumulation of defects resulting from dysregulation of a number of biochemical pathways. Based on the identification of EDD-associating proteins and elegant studies with the Drosophila homolog Hyd, candidate pathways that may be disrupted in EddΔ/Δ embryos include DNA damage response, hedgehog signaling, and cell-cell interaction.

Many of the EDD-interacting proteins identified to date strongly suggest a role in cellular DNA damage response pathways. EDD has recently been found in association with BRCA2 (data not shown), and Brca2-null embryos die at mid-gestation as a result of p53-dependent cell proliferation defects (3, 23). We observed no attenuation of the EddΔ/Δ phenotype on a p53 null background. Hence, it is highly unlikely that an aberrant DNA damage response is the primary molecular defect in EddΔ/Δ embryos.

The EDD-interacting protein CIB also interacts with a number of proteins involved in cell-cell contact and signaling. These interactions may be informative when considering the phenotype of Edd-deficient embryos, particularly in light of the defective vascular development observed. For example, CIB interacts with the small GTPase Rac3 (13) and can bind and activate integrin αIIbβ3 (CD41/CD61) (28, 32, 36), suggesting a role for Edd in regulation of integrin-mediated cytoskeletal reorganization during cell adhesion and spreading. Furthermore, CIB binds and inhibits the transcriptional activity of the homeodomain protein PAX-3 (15), which plays a fundamental role in embryonic development through regulation of intercellular adhesion (37). Disorganized vascular endothelium (identified by distinct changes in PECAM staining) in the EddΔ/Δ yolk sac and allantois and apparent morphological changes in the nature of some epithelial and mesenchymal tissue in Edd-deficient embryos may be indicative of defects in cell-cell contact. Integrin-mediated intercellular adhesion and signaling plays a definitive role in chorioallantoic fusion (31) and may play a role in vascular endothelial cell differentiation and establishment of a functional yolk sac circulation (31). Edd is expressed in the allantois and in the yolk sac endoderm and mesoderm. Hence, it is possible that the death of Edd-deficient embryos may be due to disruptions in these pathways.

A recent study has identified a role for hyd in independent negative regulation of hedgehog (hh) and decapentaplegic (dpp) expression (22). Mutations of hyd in the eye imaginal disc caused nonautonomous overgrowth and premature photoreceptor differentiation through independent activation of hh and dpp, and this phenotype could be partially suppressed by mutation of hh. These findings raise the intriguing possibility that Edd may regulate mammalian hedgehog signaling and provide a potential explanation for the phenotype of Edd-deficient embryos. Various components of the hedgehog pathway in mammals play critical roles in development and tumorigenesis (30). In particular, Indian Hedgehog (Ihh) plays a critical role in yolk sac vasculogenesis (4). Thus, disrupted hedgehog signaling may be a primary underlying molecular defect resulting from absence of Edd and hence may be a major contributor to the phenotype of Edd-deficient embryos. This is currently under investigation.

In summary, a severe defect in yolk sac/allantoic vascular development and failure of chorioallantoic fusion, leading to inadequate nutrient exchange, is the most likely cause of death of Edd-deficient embryos, demonstrating an essential role for Edd in extraembryonic development. The underlying molecular defects leading to embryonic death in Edd-deficient embryos are still unclear. However, several lines of evidence suggest that Edd may be involved in the regulation of hedgehog signaling and cell-cell interactions, which, if substantiated, may provide further insight into the role of Edd in development and tumorigenesis.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command Breast Cancer Research Program (grants DAMD17-00-1-253 and DAMD17-03-1-0410), The Cancer Council of New South Wales, Cure Cancer Australia Foundation, and the Association for International Cancer Research. S.L.W. is a Wellcome Trust International Postdoctoral Fellow. S.L.D. is a Pharmacia Foundation Australia Senior Research Fellow.

Animal experiments were carried out under the authority of the Garvan Institute Animal Experimentation Ethics Committee (approvals 00/13 and 03/15).

We thank Douglas Hilton (Walter and Eliza Hall Institute, Melbourne, Australia) for providing the targeting vector, Andreas Strasser and Alan Harris (Walter and Eliza Hall Institute) for providing p53+/Δ mice, and Patrick Tam (Children's Medical Research Institute, Sydney, Australia) for very helpful discussions. We also thank Julie Ferguson and staff of the Biological Testing Facility (GIMR) for assistance with animal experiments, and we thank Rebecca Morton for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baron, M. 2001. Induction of embryonic hematopoietic and endothelial stem/progenitor cells by hedgehog-mediated signals. Differentiation 68:175-185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartek, J., J. Falck, and J. Lukas. 2001. Chk2 kinase - a busy messenger. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2:877-886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brugarolas, J., and T. Jacks. 1997. Double indemnity: p53, BRCA and cancer. p53 mutation partially rescues developmental arrest in Brca1 and Brca2 null mice, suggesting a role for familial breast cancer genes in DNA damage repair. Nat. Med. 3:721-722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Byrd, N., S. Becker, P. Maye, R. Narasimhaiah, B. St-Jacques, X. Zhang, J. McMahon, A. McMahon, and L. Grabel. 2002. Hedgehog is required for murine yolk sac angiogenesis. Development 129:361-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callaghan, M. J., A. J. Russell, E. Woollatt, G. R. Sutherland, R. L. Sutherland, and C. K. W. Watts. 1998. Identification of a human HECT family protein with homology to the Drosophila tumor suppressor gene hyperplastic discs. Oncogene 17:3479-3491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Clancy, J. L., M. J. Henderson, A. J. Russell, D. W. Anderson, R. J. Bova, I. G. Campbell, D. Y. Choong, G. A. Macdonald, G. J. Mann, T. Nolan, G. Brady, O. I. Olopade, E. Woollatt, M. J. Davies, D. Segara, N. F. Hacker, S. M. Henshall, R. L. Sutherland, and C. K. Watts. 2003. EDD, the human orthologue of the hyperplastic discs tumour suppressor gene, is amplified and overexpressed in cancer. Oncogene 22:5070-5081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Copp, A. J. 1995. Death before birth: clues from gene knockouts and mutations. Trends Genet. 11:87-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Davis, C. A. 1993. Whole-mount immunohistochemistry. Methods Enzymol. 225:502-516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Deo, R. C., N. Sonenberg, and S. K. Burley. 2001. X-ray structure of the human hyperplastic discs protein: an ortholog of the C-terminal domain of poly(A)-binding protein. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:4414-4419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Downs, K. M. 2002. Early placental ontogeny in the mouse. Placenta 23:116-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eblen, S. T., N. V. Kumar, K. Shah, M. J. Henderson, C. K. Watts, K. M. Shokat, and M. J. Weber. 2003. Identification of novel ERK2 substrates through use of an engineered kinase and ATP analogs. J. Biol. Chem. 278:14926-14935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fuja, T. J., F. Lin, K. E. Osann, and P. J. Bryant. 2004. Somatic mutations and altered expression of the candidate tumor suppressors CSNK1 epsilon, DLG1, and EDD/hHYD in mammary ductal carcinoma. Cancer Res. 64:942-951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Haataja, L., V. Kaartinen, J. Groffen, and N. Heisterkamp. 2002. The small GTPase Rac3 interacts with the integrin-binding protein CIB and promotes integrin alpha(IIb)beta(3)-mediated adhesion and spreading. J. Biol. Chem. 277:8321-8328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henderson, M. J., A. J. Russell, S. Hird, M. Munoz, J. L. Clancy, G. M. Lehrbach, S. T. Calani, D. A. Jans, R. L. Sutherland, and C. K. W. Watts. 2002. EDD, the human hyperplastic discs protein, is a nuclear protein with a role in progesterone receptor coactivation and a potential involvement in DNA damage. J. Biol. Chem. 277:26468-26478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hollenbach, A. D., C. J. McPherson, I. Lagutina, and G. Grosveld. 2002. The EF- hand calcium-binding protein calmyrin inhibits the transcriptional and DNA-binding activity of Pax3. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1574:321-328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Honda, Y., M. Tojo, K. Matsuzaki, T. Anan, M. Matsumoto, M. Ando, H. Saya, and M. Nakao. 2002. Cooperation of HECT-domain ubiquitin ligase hHYD and DNA topoisomerase II-binding protein for DNA damage response. J. Biol. Chem. 277:3599-3605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hui, R., A. L. Cornish, R. A. McClelland, J. F. Robertson, R. W. Blamey, E. A. Musgrove, R. I. Nicholson, and R. L. Sutherland. 1996. Cyclin D1 and estrogen receptor messenger RNA levels are positively correlated in primary breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 2:923-928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacks, T., L. Remington, B. Williams, E. Schmitt, S. Halachmi, R. Bronson, and R. Weinberg. 1994. Tumor spectrum analysis in p53-mutant mice. Curr. Biol. 4:1-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.James, R. M., A. H. Klerkx, M. Keighren, J. H. Flockhart, and J. D. West. 1995. Restricted distribution of tetraploid cells in mouse tetraploid⇔diploid chimaeras. Dev. Biol. 167:213-226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kume, T., H. Jiang, J. M. Topczewska, and B. L. Hogan. 2001. The murine winged helix transcription factors, Foxc1 and Foxc2, are both required for cardiovascular development and somitogenesis. Genes Dev. 15:2470-2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kwon, Y., Y. Reiss, V. Fried, A. Hershko, J. Yoon, D. Gonda, P. Sangan, N. Copeland, N. Jenkins, and A. Varshavsky. 1998. The mouse and human genes encoding the recognition component of the N-end rule pathway. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 95:7898-7903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee, J. D., K. Amanai, A. Shearn, and J. E. Treisman. 2002. The ubiquitin ligase Hyperplastic discs negatively regulates hedgehog and decapentaplegic expression by independent mechanisms. Development 129:5697-5706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim, D. S., and P. Hasty. 1996. A mutation in mouse rad51 results in an early embryonic lethal that is suppressed by a mutation in p53. Mol. Cell. Biol. 16:7133-7143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mansfield, E., E. Hersperger, J. Biggs, and A. Shearn. 1994. Genetic and molecular analysis of hyperplastic discs, a gene whose product is required for regulation of cell proliferation in Drosophila melanogaster imaginal discs and germ cells. Dev. Biol. 165:507-526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McGowan, C. H. 2002. Checking in on Cds1 (Chk2): a checkpoint kinase and tumor suppressor. Bioessays 24:502-511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mori, Y., F. Sato, F. M. Selaru, A. Olaru, K. Perry, M. C. Kimos, G. Tamura, N. Matsubara, S. Wang, Y. Xu, J. Yin, T. T. Zou, B. Leggett, J. Young, T. Nukiwa, O. C. Stine, J. M. Abraham, D. Shibata, and S. J. Meltzer. 2002. Instabilotyping reveals unique mutational spectra in microsatellite-unstable gastric cancers. Cancer Res. 62:3641-3645. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muller, D., M. Rehbein, H. Baumeister, and D. Richter. 1992. Molecular characterization of a novel rat protein structurally related to poly(A) binding proteins and the 70K protein of the U1 small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle (snRNP). Nucleic Acids Res. 20:1471-1475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naik, U. P., P. M. Patel, and L. V. Parise. 1997. Identification of a novel calcium- binding protein that interacts with the integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic domain. J. Biol. Chem. 272:4651-4654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oughtred, R., N. Bedard, O. A. Adegoke, C. R. Morales, J. Trasler, V. Rajapurohitam, and S. S. Wing. 2002. Characterization of rat100, a 300-kilodalton ubiquitin-protein ligase induced in germ cells of the rat testis and similar to the Drosophila hyperplastic discs gene. Endocrinology 143:3740-3747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ruiz i Altaba, A., P. Sanchez, and N. Dahmane. 2002. Gli and hedgehog in cancer: tumours, embryos and stem cells. Nat. Rev. Cancer 2:361-372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sapin, V., L. Blanchon, A. F. Serre, D. Lemery, B. Dastugue, and S. J. Ward. 2001. Use of transgenic mice model for understanding the placentation: towards clinical applications in human obstetrical pathologies? Transgenic Res. 10:377-398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shock, D. D., U. P. Naik, J. E. Brittain, S. K. Alahari, J. Sondek, and L. V. Parise. 1999. Calcium-dependent properties of CIB binding to the integrin alphaIIb cytoplasmic domain and translocation to the platelet cytoskeleton. Biochem. J. 342:729-735. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smits, V. A., R. Klompmaker, L. Arnaud, G. Rijksen, E. A. Nigg, and R. H. Medema. 2000. Polo-like kinase-1 is a target of the DNA damage checkpoint. Nat. Cell Biol. 2:672-676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Takai, H., K. Naka, Y. Okada, M. Watanabe, N. Harada, S. Saito, C. W. Anderson, E. Appella, M. Nakanishi, H. Suzuki, K. Nagashima, H. Sawa, K. Ikeda, and N. Motoyama. 2002. Chk2-deficient mice exhibit radioresistance and defective p53- mediated transcription. EMBO J. 21:5195-5205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tallquist, M. D., and P. Soriano. 2000. Epiblast-restricted Cre expression in MORE mice: a tool to distinguish embryonic vs. extra-embryonic gene function. Genesis 26:113-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tsuboi, S. 2002. Calcium integrin-binding protein activates platelet integrin alpha IIb beta 3. J. Biol. Chem. 277:1919-1923. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wiggan, O., M. P. Fadel, and P. A. Hamel. 2002. Pax3 induces cell aggregation and regulates phenotypic mesenchymal-epithelial interconversion. J. Cell Sci. 115:517-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wilkinson, C. R., M. Seeger, R. Hartmann-Petersen, M. Stone, M. Wallace, C. Semple, and C. Gordon. 2001. Proteins containing the UBA domain are able to bind to multi-ubiquitin chains. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:939-943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wu, X., and M. R. Lieber. 1997. Interaction between DNA-dependent protein kinase and a novel protein, KIP. Mutat. Res. 385:13-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie, S., H. Wu, Q. Wang, J. P. Cogswell, I. Husain, C. Conn, P. Stambrook, M. Jhanwar-Uniyal, and W. Dai. 2001. Plk3 functionally links DNA damage to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis at least in part via the p53 pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 276:43305-43312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]