Abstract

Background

Leishmania infantum is the most widespread etiological agent of visceral leishmaniasis (VL) in the world, with significant mortality rates in human cases. In Latin America, this parasite is primarily transmitted by Lutzomyia longipalpis, but the role of Lutzomyia migonei as a potential vector for this protozoan has been discussed. Laboratory and field investigations have contributed to this hypothesis; however, proof of the vector competence of L. migonei has not yet been provided. In this study, we evaluate for the first time the susceptibility of L. migonei to L. infantum.

Methods

Females of laboratory-reared L. migonei were fed through a chick-skin membrane on rabbit blood containing L. infantum promastigotes, dissected at 1, 5 and 8 days post-infection (PI) and checked microscopically for the presence, intensity and localisation of Leishmania infections. In addition, morphometric analysis of L. infantum promastigotes was performed.

Results

High infection rates of both L. infantum strains tested were observed in L. migonei, with colonisation of the stomodeal valve already on day 5 PI. At the late-stage infection, most L. migonei females had their cardia and stomodeal valve colonised by high numbers of parasites, and no significant differences were found compared to the development in L. longipalpis. Metacyclic forms were found in all parasite-vector combinations since day 5 PI.

Conclusions

We propose that Lutzomyia migonei belongs to sand fly species permissive to various Leishmania spp. Here we demonstrate that L. migonei is highly susceptible to the development of L. infantum. This, together with its known anthropophily, abundance in VL foci and natural infection by L. infantum, constitute important evidence that L. migonei is another vector of this parasite in Latin America.

Keywords: Lutzomyia migonei, Leishmania infantum, Vector competence

Background

Visceral leishmaniasis (VL) caused by protozoa of the genus Leishmania (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) is a vector-borne neglected disease transmitted by phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) [1]. Leishmania infantum (syn. Leishmania chagasi) is the most widespread etiological agent of VL in the world, including Latin America, with significant mortality rates in human cases [2]. Approximately 56 phlebotomine sand fly species are supposed, or have been proved, to be involved in the transmission of Leishmania spp. in the Americas [1]. Unfortunately, control strategies against vectors as well as reservoirs of leishmaniasis have been ineffective [3].

In Latin America, L. infantum is primarily transmitted by Lutzomyia longipalpis [4]. This sand fly species fulfils all criteria of a proven vector, which includes the ability of the insect to support the development of the parasite during and after bloodmeal digestion, as well as to transmit them to a susceptible host [5]. On the other hand, information about the vector competence of other Lutzomyia spp. to L. infantum is lacking, despite field data suggesting their possible involvement in the circulation of this parasite.

The vectorial role of Lutzomyia migonei has been discussed in areas with a record of human and canine cases of VL but where the proven vector is absent [6–9]. In a study conducted in southeast Brazil, the absence of L. longipalpis in six endemic areas provided circumstantial evidence for the participation of L. migonei in the transmission of L. infantum [6], and more recent studies have reinforced this hypothesis [7, 9]. In VL foci in northeast Brazil and northeast Argentina, L. migonei was reported as a predominant species associated with human and canine cases in the peridomicile environment [7, 9]. Additionally, some investigations have reported the detection of L. infantum DNA in this sand fly species [8, 10], highlighting the need for additional evidence in order to confirm L. migonei as a vector of L. infantum.

Lutzomyia migonei is widespread in South America, including Brazil, and shows adaptability to modified environments, being found in human dwellings and animal shelters [11, 12]. This sand fly species displays anthropophilic behaviour and has opportunistic feeding habits, including on dogs, chickens, equines and wild animals [11, 13]. Furthermore, L. migonei has been implicated as a vector of L. (V.) braziliensis, the etiological agent of cutaneous leishmaniasis in different Brazilian regions [11, 14, 15].

Despite the epidemiological and behavioural characteristics that indicate the participation of L. migonei in the transmission cycle of L. infantum, no studies have assessed the ability of this species to support the full development of the parasite. From this perspective, therefore, we evaluate for the first time the susceptibility of freshly colonised specimens of L. migonei to experimental infection by L. infantum.

Methods

Sand fly colonies and Leishmania strains

A colony of Lutzomyia migonei was established at Charles University in Prague from specimens captured in Baturité municipality, Ceará state, northeast Brazil (04°19′41″S, 38°53′05″W). An already-established laboratory colony of Lutzomyia longipalpis (from Jacobina, Brazil) with well-known susceptibility to L. infantum [16–18] was used as a control. Both colonies were maintained under standard conditions as previously described [19].

A viscerotropic Leishmania infantum strain (MHOM/BR/76/M4192) [20] and dermotropic L. infantum strain (ITOB/TR/2005/CUK3) [21] were maintained at 23 °C on Medium 199 (Sigma) supplemented with 10 % foetal calf serum (Gibco), 1 % BME vitamins (Sigma), 2 % human urine and 250 μg/ml amikin (Amikin, Bristol-Myers Squibb).

Experimental infections of sand flies

Sand fly females (2 to 6 days old) were fed through a chick-skin membrane on heat-inactivated rabbit blood containing 106 promastigotes/ml. The experiments were conducted with three sand fly-Leishmania combinations: L. migonei-CUK3, L. migonei-M4192, and L. longipalpis-M4192. A fourth combination, the CUK3 strain in L. longipalpis, was previously studied in detail [18]. Engorged females were separated and maintained in the same conditions as the colony and dissected on days 1, 5 and 8 post-infection (PI). Individual guts were placed into a drop of saline and examined microscopically for the localisation and intensity of Leishmania infections. Parasite loads were graded according to Myskova et al. [22] as light (<100 parasites per gut), moderate (100 to 1000 parasites per gut) and heavy (>1000 parasites per gut). The experiment was repeated five times. Data were evaluated statistically by means of the Fisher’s exact or Chi-square (χ2) tests using SPSS statistics 23 software.

Morphometry of parasites

Smears from midguts of L. migonei and L. longipalpis infected with L. infantum on days 5 and 8 PI were fixed with methanol, stained with Giemsa, examined under a light microscope with an oil-immersion objective and photographed with an Olympus D70 camera. Body length, body width and flagellar length of 240 randomly selected promastigotes from six females/smears were measured for each sand fly species and time interval using Image-J software. The morphological forms were distinguished according to Walters [23] and Cihakova & Volf [24]: (i) short nectomonads: body length < 14 μm and flagellar length < 2 times body length; (ii) long nectomonads: body length ≥14 μm; (iii) metacyclic promastigotes: body length < 14 μm and flagellar length ≥2 times body length. Data were evaluated statistically by analysis of variance using SPSS statistics 23 software.

Ethical approval

Animals were maintained and handled in the animal facility of Charles University in Prague in accordance with institutional guidelines and Czech legislation (Act No. 246/1992 and 359/2012 coll. on Protection of Animals against Cruelty in present statutes at large), which complies with all relevant EU guidelines for experimental animals. All experiments were approved by the Committee on the Ethics of Laboratory Experiments of the Charles University in Prague and were performed under the Certificate of Competency (Registration Number: CZ 03069).

Results

Susceptibility of Lutzomyia migonei and L. longipalpis to Leishmania infantum

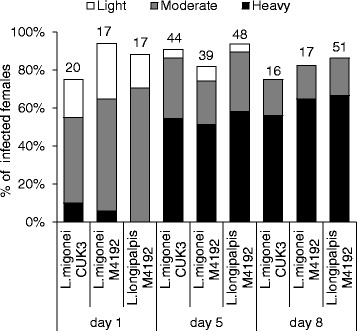

The development of two strains of L. infantum was studied in L. migonei and L. longipalpis from day 1 to day 8 PI. On day 1 PI, midgut infection rates were high in all parasite-vector combination (75–95 %), with parasites located in the endoperitrophic space within the bloodmeal surrounded by the peritrophic matrix (PM). The parasites developed similarly and no significant differences were found in infection rates (χ2 = 2.84, df = 2, P = 0.24) or intensities of infection (χ2 = 5.7, df = 6, P = 0.45; Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Development of L. infantum in Lutzomyia spp. Rates and intensities of infections in Lutzomyia migonei and Lutzomyia longipalpis were evaluated microscopically on days 1, 5 and 8 PI, and were classified into three categories: light (<100 parasites/gut), moderate (100–1000 parasites/gut), or heavy (>1000 parasites/gut). Numbers of dissected females are shown above the bars

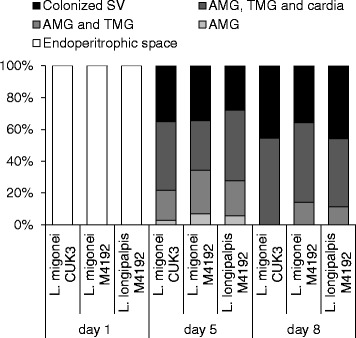

On day 5 PI, when the bloodmeal was digested and remnants defecated in both species, infection rates remained high (above 80 %) and most infections were heavy in all parasite-vector combinations evaluated. Parasites migrated anteriorly to colonise the thoracic midgut and cardia region in 43 % of L. migonei-CUK3, 31 % of L. migonei-M4192 and 44 % of L. longipalpis-M4192. The colonisation of the stomodeal valve was observed most frequently in L. migonei-CUK3 (35 % of infected females), followed by L. migonei-M4192 (34 % of infected females) and L. longipalpis-M4192 (27 % of infected females). Statistical analysis did not show any significant differences in the localisation of infections between the experimental groups (χ2 = 2.3, df = 6, P = 0.88; Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Localisation of L. infantum in Lutzomyia spp. Localisation of infections in Lutzomyia migonei and Lutzomyia longipalpis was evaluated microscopically on days 1, 5 and 8 PI. Abdominal midgut (AMG), thoracic midgut (TMG) and stomodeal valve (SV)

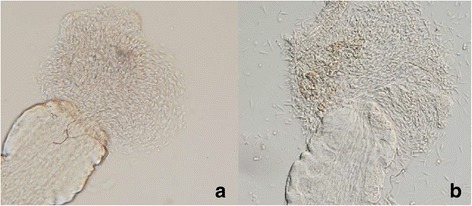

On day 8 PI, both L. infantum strains continued to develop successfully in L. migonei and L. longipalpis. In all parasite-vector combinations, infection rates were above 75 % and parasites developed heavy late-stage infections in the majority of infected females. The colonisation of the stomodeal valve was observed in 45 % of L. migonei-CUK3 and L. longipalpis-M4192 and 35 % of L. migonei-M4192. Similarly, no significant differences were observed in the localisation of infections (χ2 = 1.9, df = 4, P = 0.74). Light microscopy showed a mass of Leishmania promastigotes in the cardia region and attached to the stomodeal valve of females. In dissected midguts, this parasite mass accompanied by promastigote-secretory gel erupted from the valve (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Thoracic midgut with cardia section and stomodeal valve of Lutzomyia migonei females. a Infection of L. infantum CUK3 on day 5 PI. b Infection of L. infantum M4192 on day 8 PI

Morphometric analysis of L. infantum promastigotes in L. migonei and L. longipalpis

Morphological analysis was performed on L. infantum parasites from L. migonei and L. longipalpis on days 5 and 8 PI. Differences in all parameters analysed, i.e. body length, body width and flagellar length, from all parasite-vector combinations are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Dimensions of the morphological forms of L. infantum described in Fig. 4 during development in L. migonei and L. longipalpis on days 5 and 8 PI

| Body length | Body width | Flagellar length | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day PI | Parasite-vector combination | Morphological form | n | Mean (SD) (μm) | Range (μm) | Mean (SD) (μm) | Range (μm) | Mean (SD) (μm) | Range (μm) |

| 5 | L. migonei-CUK3 | LN | 78 | 15.8 (1.4) | 14.0–19.1 | 2.4 (0.4) | 1.6–3.7 | 17.6 (3.5) | 7.0–26.1 |

| SN | 155 | 10.4 (2.0) | 5.9–13.8 | 2.3 (0.5) | 1.2–3.7 | 13.7 (3.4) | 5.5–24.2 | ||

| MP | 7 | 8.2 (1.2) | 6.4–9.9 | 2.6 (0.5) | 1.9–3.6 | 19.0 (4.5) | 13.8–24.8 | ||

| Total | 240 | 12.1 (3.1) | 5.9–19.1 | 2.4 (0.5) | 1.2–3.7 | 15.1 (3.9) | 5.5–26.1 | ||

| L. migonei-M4192 | LN | 125 | 16.1 (1.5) | 14.0–20.9 | 2.6 (0.5) | 1.7–4.2 | 18.1 (4.5) | 6.1–31.7 | |

| SN | 107 | 11.7 (1.7) | 6.8–13.9 | 2.6 (0.6) | 1.4–5.9 | 15.7 (4.8) | 6.8–27.7 | ||

| MP | 8 | 8.5 (0.6) | 7.7–9.8 | 2.7 (1.1) | 1.4–5.2 | 20.3 (3.5) | 15.4–25.1 | ||

| Total | 240 | 13.9 (2.8) | 6.8–20.9 | 2.6 (0.6) | 1.4–5.9 | 17.1 (4.8) | 6.1–31.7 | ||

| L. longipalpis-M4192 | LN | 171 | 17.5 (3.0) | 14.0–26.8 | 2.4 (0.5) | 1.0–3.8 | 22.0 (6.0) | 4.5–36.8 | |

| SN | 68 | 11.2 (1.8) | 7.0–13.9 | 2.4 (0.5) | 1.1–3.8 | 14.8 (4.5) | 7.9–24.1 | ||

| MP | 1 | 13.7 | 2.3 | 28.0 | |||||

| Total | 240 | 15.7 (3.9) | 7.0–26.8 | 2.4 (0.5) | 1.0–3.8 | 20.0 (6.5) | 4.5–36.8 | ||

| 8 | L. migonei-CUK3 | LN | 48 | 16.0 (2.0) | 14.0–22.1 | 2.4 (0.5) | 1.5–3.8 | 16.2 (2.7) | 9.6–21.7 |

| SN | 180 | 10.2 (2.0) | 5.0–13.9 | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.0–4.4 | 13.5 (3.2) | 5.4–24.1 | ||

| MP | 12 | 6.6 (1.4) | 3.6–8.8 | 1.8 (0.5) | 1.1–3.0 | 15.7 (2.9) | 8.7–19.2 | ||

| Total | 240 | 11.2 (3.2) | 3.6–22.1 | 2.1 (0.6) | 1.0–4.4 | 14.2 (3.3) | 5.4–24.1 | ||

| L. migonei-M4192 | LN | 35 | 15.4 (1.1) | 14.0–18.1 | 2.2 (0.4) | 1.4–3.3 | 16.1 (4.1) | 8.0–24.0 | |

| SN | 187 | 9.8 (2.1) | 5.4–13.9 | 2.4 (0.5) | 1.1–4.1 | 13.4 (3.5) | 3.7–24.0 | ||

| MP | 18 | 6.9 (1.2) | 5.0–10.3 | 2.1 (0.7) | 1.2–3.8 | 16.4 (2.0) | 13.5–22.2 | ||

| Total | 240 | 10.4 (2.9) | 5.0–18.1 | 2.3 (0.5) | 1.1–4.1 | 14.0 (3.7) | 3.7–24.0 | ||

| L. longipalpis-M4192 | LN | 56 | 15.9 (1.3) | 14.0–19.2 | 2.2 (0.4) | 1.6–3.4 | 18.1 (4.1) | 8.2–28.4 | |

| SN | 152 | 10.5 (1.9) | 6.4–13.9 | 2.2 (0.6) | 1.1–4.6 | 14.4 (3.1) | 7.3–22.8 | ||

| MP | 32 | 7.3 (1.3) | 5.1–12.2 | 2.1 (0.8) | 1.1–5.6 | 16.4 (2.5) | 12.7–26.3 | ||

| Total | 240 | 11.3 (3.2) | 5.1–19.2 | 2.2 (0.8) | 1.1–5.6 | 15.5 (3.6) | 7.3–28.4 | ||

LN Long nectomonads, SP short promastigotes MP metacyclic promastigotes

Promastigotes from gut smears were measured under light microscopy with an oil-immersion objective

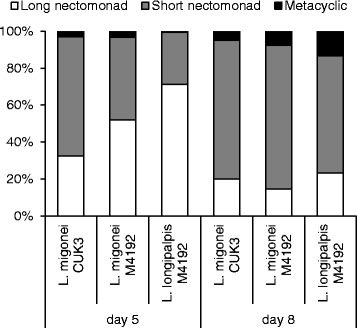

On day 5 PI, slight differences were found between the development of various parasite strains: in L. migonei (52 %) and L. longipalpis (71 %) infected by L. infantum M4192 the majority of parasites were long nectomonads, while in L. migonei infected by L. infantum CUK3, 64 % of the parasites were short nectomonads. The metacyclic forms were found in all parasite-vector combinations but in low numbers, from 1 to 3 %. Differences in promastigote stages between Leishmania-vector combinations were statistically significant (χ2 = 74.5, df = 4, P < 0.001; Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Morphological forms of L. infantum during development in Lutzomyia spp. Morphological forms of Leishmania parasites in Lutzomyia migonei and Lutzomyia longipalpis were evaluated microscopically on days 5 and 8 PI. Differences between the morphological forms were significant on days 5 (χ 2 = 74.5, df = 4, P < 0.001) and 8 (χ 2 = 19, df = 4, P = 0.001) PI

On day 8 PI, parasites developed similarly and the percentage of metacyclic forms increased in all three combinations studied. There were no significant differences in the morphological forms of L. infantum M4192 and CUK3 in L. migonei females (χ2 = 3.3, df = 2, P = 0.18). As expected, the percentage of long nectomonads decreased, while the short nectomonad forms increased to 78 % and 75 %, respectively. The metacyclic forms were found in 7.5 % and 5 % for M4192 and CUK3, respectively. In L. longipalpis, the proportion of morphological forms differed: the proportion of short nectomonads was lower while metacyclic forms were more numerous (23 % long nectomonads, 63 % short nectomonads and 13 % metacyclic forms; χ2 = 19.0, df = 4, P = 0.001).

Discussion

Although Leishmania-vector interaction studies are crucial for understanding the parasite transmission and epidemiology of leishmaniases, only a limited number of New World sand fly species have been evaluated experimentally for susceptibility to Leishmania spp. The development of L. infantum has been studied repeatedly in L. longipalpis (e.g. [16, 18, 25, 26], but information about the vector competence of other species of Lutzomyia to this parasite remain unclear.

Here we show for the first time the high susceptibility of L. migonei to viscerotropic (M4192) and dermotropic (CUK3) strains of L. infantum. The parasites survived bloodmeal digestion, avoided expulsion during the defecation process, established late-stage infections in the midgut, and colonised the thoracic midgut and stomodeal valve of sand fly females, which is the prerequisite for successful transmission by bite [26–28]. Furthermore, the development of both L. infantum strains in L. migonei was similar, and no significant differences were found in comparison with the development in L. longipalpis. The parasites developed relatively quickly, with the presence of metacyclic promastigotes and colonisation of the stomodeal valve already on day 5 PI. At the late-stage infection (on day 8 PI), high numbers of the parasites colonised the midgut cardia and stomodeal valve in females of both species.

In L. migonei, the dermotropic CUK3 strain morphologically transformed slightly faster than the viscerotropic M4192 strain, with a slightly higher percentage of short nectomonads in CUK3 observed on day 5 PI. However, similar numbers of metacyclic promastigotes were found in both parasite-vector combinations. The percentage of metacyclic forms (5–7.5 %) observed in L. migonei on day 8 is comparable to the percentage of metacyclics previously reported for the L. infantum-L. longipalpis combination [29, 30].

According to Maroli et al. [1], incriminating a sand fly species as a vector must be based on an epidemiological context and there must exist a relationship between the geographical distribution of the vector and the record of human cases of the disease, as well as proof of the anthropophily of the species and the vector’s ability to support infection with the same parasite species occurring in humans. Lutzomyia migonei is well-known for its opportunistic feeding habits and anthropophilic behaviour [11, 13] and has repeatedly been found to be naturally infected by L. infantum in Brazil [8] and Argentina [10]. In this context, our demonstration of the high susceptibility of L. migonei to infection by L. infantum M4192 is crucial for the epidemiology of VL in Latin America, since this L. infantum strain was isolated in northeast Brazil from a patient with VL.

Sand flies have been classified as permissive or specific vectors on account of their capability to support the development of either a wide or limited spectrum of Leishmania spp., respectively [27, 28, 31]. Since it has been reported that L. migonei supports the development of other species of Leishmania, namely L. braziliensis and L. amazonensis [32], we propose that this sand fly species is a permissive vector.

Conclusions

This study provides experimental evidence that L. infantum develops late-stage infections in L. migonei. These results contribute to a better understanding of the role of this sand fly species in the epidemiology of VL caused by L. infantum, and allows estimations of the risk of new VL foci in South America. Furthermore, this knowledge is critical for the development of more specific and effective control strategies in endemic areas.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to Pietra Costa, Débora Miranda and Fernando Silva for their support with the field work and to Kyldman Silva for her assistance with L. migonei colony in Brazil. This research was supported by PVE-CsF/CNPq grant 400699/2014-1 and UNCE (University Research Centre) 204017/2012.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interest.

Authors’ contributions

VCFVG collected the sand flies, carried out the morphometry of parasites and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. KP carried out the sand fly infections and dissections, contributed to data analysis, interpretation and revision of the manuscript. VCFVG and JM participated in the sand fly dissections. VV established the L. migonei colony. JS participated in colony maintenance and carried out the statistical analysis. SPBF and PV participated in the design of the study and contributed with revision of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Contributor Information

Vanessa Cristina Fitipaldi Veloso Guimarães, Email: vanessa@cpqam.fiocruz.br.

Katerina Pruzinova, Email: katerina.pruzinova@gmail.com.

Jovana Sadlova, Email: jovanas@seznam.cz.

Vera Volfova, Email: Veravolf@seznam.cz.

Jitka Myskova, Email: jpeck@seznam.cz.

Sinval Pinto Brandão Filho, Email: sinval@cpqam.fiocruz.br.

Petr Volf, Email: volf@cesnet.cz.

References

- 1.Maroli M, Feliciangeli MD, Bichaud L, Charrel RN, Gradoni L. Phlebotomine sandflies and the spreading of leishmaniases and other diseases of public health concern. Med Vet Entomol. 2013;27:127–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.2012.01034.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alvar J, Velez ID, Bern C, Herrero M, Desjeux P, Cano J, et al. Leishmaniasis worldwide and global estimates of its incidence. PLoS One. 2012;7:e3567. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035671. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romero GA, Boelaert M. Control of visceral leishmaniasis in Latin America - a systematic review. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2010;4:e584. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lainson R, Rangel EF. Lutzomyialongipalpis and the eco-epidemiology of American visceral leishmaniasis, with particular reference to Brazil: a review. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2005;100:811–27. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762005000800001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Killick-Kendrick R. Phlebotomine vectors of the leishmaniases: a review. Med Vet Entomol. 1990;4:1–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2915.1990.tb00255.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Souza MB, Marzochi MC, Carvalho RW, Ribeiro PC, Pontes CS, Caetano JM, et al. Ausência de Lutzomyia longipalpis em algumas áreas de ocorrência de leishmaniose visceral no município do Rio de Janeiro. Cad Saude Publica. 2003;19:109–18. doi: 10.1590/s0102-311x2003000600033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carvalho MR, Lima BS, Marinho-Júnior JF, Silva FJ, Valença HF, Almeida FA, et al. Phlebotomine sandfly species from an American visceral leishmaniasis area in the Northern Rainforest Region of Pernambuco State. Brazil Cad Saude Publica. 2007;23:1227–32. doi: 10.1590/S0102-311X2007000500024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carvalho MR, Valença HF, Silva FJ, Pita-Pereira D, Araújo Pereira T, Britto C, et al. Natural Leishmania infantum infection in Migonemyia migonei (Franca, 1920) (Diptera: Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) the putative vector of visceral leishmaniasis in Pernambuco State, Brazil. Acta Trop. 2010;116:108–10. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Salomon OD, Quintana MG, Bezzi G, Morán ML, Betbeder E, Valdéz DV. Lutzomyia migonei as putative vector of visceral leishmaniasis in La Banda, Argentina. Acta Trop. 2010;113:84–7. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2009.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moya SL, Giuliani MG, Manteca MA, Salomón OD, Liotta DJ. First description of Migonemyia migonei (França) and Nyssomyia whitmani (Antunes & Coutinho) (Psychodidae: Phlebotominae) natural infected by Leishmania infantum in Argentina. Acta Trop. 2015;152:181–4. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 11.Rangel EF, Lainson R. Proven and putative vectors of American cutaneous leishmaniasis in Brazil: aspects of their biology and vectorial competence. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:937–54. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762009000700001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guimarães VCFV, Costa PL, Silva FJ, Silva KT, Silva KG, Araújo AI, et al. Phlebotomine sand flies (Diptera: Psychodidae) in São Vicente Férrer, a sympatric area to cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis in Pernambuco, Brazil. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2012;45:66–70. doi: 10.1590/S0037-86822012000100013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aguiar GM, Vilela ML, Lima RB. Ecology of the sandflies of Itaguai, an area of cutaneous leishmaniasis in State of Rio de Janeiro. Food preferences (Diptera, Psychodidae, Phlebotominae) Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1987;82:583–4. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761987000400020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carvalho BM, Maximo M, Costa WA, Santana AL, Costa SM, Costa Rego TA, et al. Leishmaniasis transmission in an ecotourism area: potential vectors in Ilha Grande, Rio de Janeiro State, Brazil. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:325. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Guimarães VCFV, Costa PL, Silva FJ, Melo FL, Dantas-Torres F, Rodrigues EH, et al. Molecular detection of Leishmania in phlebotomine sand flies in a cutaneous and visceral leishmaniasis endemic area in northeastern Brazil. Rev Inst Med Trop Sao Paulo. 2014;56:357–60. doi: 10.1590/S0036-46652014000400015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maia C, Seblova V, Sadlova J, Votypka J, Volf P. Experimental transmission of Leishmania infantum by two major vectors: a comparison between a viscerotropic and a dermotropic strain. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2011;5:e1181. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0001181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sadlova J, Dvorak V, Seblova V, Warburg A, Votypka J, Volf P. Sergentomyia schwetzi is not a competent vector for Leishmania donovani and other Leishmania species pathogenic to humans. Parasit Vectors. 2013;6:186. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-6-186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Seblova V, Myskova J, Hlavacova J, Votypka J, Antoniou M, Volf P. Natural hybrid of Leishmania infantum/L.donovani: development in Phlebotomus tobbi, P. perniciosus and Lutzomyia longipalpis and comparison with nonhybrid strains differing in tissue tropism. Parasit Vectors. 2015;8:605. doi: 10.1186/s13071-015-1217-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Volf P, Volfova V. Establishment and maintenance of sand fly colonies. J Vector Ecol. 2011;36(Suppl 1):S1–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1948-7134.2011.00106.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Noyes H, Chance M, Ponce C, Ponce E, Maingon R. Leishmania chagasi: Genotypically similar parasites from Honduras cause both visceral and cutaneous leishmaniasis in humans. Exp Parasitol. 1997;85:264–73. doi: 10.1006/expr.1996.4133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Svobodova M, Alten B, Zidkova L, Dvorak V, Hlavackova J, Myskova J, et al. Cutaneous leishmaniasis caused by Leishmania infantum transmitted by Phlebotomus tobbi. Int J Parasitol. 2009;39:251–56. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2008.06.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Myskova J, Votypka J, Volf P. Leishmania in sand flies: Comparison of quantitative polymerase chain reaction with other techniques to determine the intensity of infection. J Med Entomol. 2008;45:133–8. doi: 10.1093/jmedent/45.1.133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walters LL. Leishmania differentiation in natural and unnatural sand fly hosts. J Eukaryot Microbiol. 1993;40:196–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1993.tb04904.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cihakova J, Volf P. Development of different Leishmania major strains in the vector sandflies Phlebotomus papatasi and P. duboscqi. Ann Trop Med Parasitol. 1997;91:267–79. doi: 10.1080/00034989761120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lainson R, Shaw JJ. Observations on the development of Leishmania (L.) chagasi Cunha and Chagas in the midgut of the sandfly vector Lutzomyia longipalpis (Lutz and Neiva) Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1988;63:134–45. doi: 10.1051/parasite/1988632134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rogers ME, Bates PA. Leishmania manipulation of sand fly feeding behavior results in enhanced transmission. PLoS Pathog. 2007;3:e91. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0030091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kamhawi S. Phlebotomine sand flies and Leishmania parasites: friends or foes? Trends Parasitol. 2006;22:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dostalova A, Volf P. Leishmania development in sand flies: parasite-vector interactions overview. Parasit Vectors. 2012;5:276. doi: 10.1186/1756-3305-5-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Elnaiem DA, Ward RD, Young PE. Development of Leishmania chagasi (Kinetoplastida: Trypanosomatidae) in the second blood-meal of its vector Lutzomyia longipalpis (Diptera: Psychodidae) Parasitol Res. 1994;80:414–9. doi: 10.1007/BF00932379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Freitas VC, Parreiras KP, Duarte AP, Secundino NF, Pimenta PF. Development of Leishmania (Leishmania) infantum chagasi in its natural sandfly vector Lutzomyialongipalpis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2012;86:606–12. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Volf P, Myskova J. Sand flies and Leishmania: specific versus permissive vectors. Trends Parasitol. 2007;23:91–92. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2006.12.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nieves E, Pimenta PF. Development of Leishmania (Viannia) braziliensis and Leishmania (Leishmania) amazonensis in the sand fly Lutzomyia migonei (Diptera: Psychodidae) J Med Entomol. 2000;37:134–40. doi: 10.1603/0022-2585-37.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]