Abstract

Fluorine-18 (18F, T 1/2=109.7 min) is a positron-emitting isotope that has found extensive application as a radiolabel for positron emission tomography (PET). Although gaseous 11C-CO2 and 11C-CH4 are practically transported from cyclotron to radiochemistry processes, 18F-fluoride is routinely transported in aqueous solution because it is commonly produced by proton irradiation of 18O-enriched water. In most cases, subsequent dry-down steps are necessary to prepare reactive 18F-fluoride for radiofluorination. In this work, a simple module was designed to generate gaseous 18F-acyl fluorides from aqueous 18F-fluoride solution by solid phase 18F-radiofluorination of acyl anhydride. The gaseous 18F-acyl fluorides were purified through a column containing Porapak Q/Na2SO4, resulting in high yields (>86%), purities (>99%) and specific activities (>1200 GBq/μmol). Prototypic 18F-acetyl fluoride (18F-AcF) was readily transported through 15 m of 0.8 mm ID polypropylene tubing with low (0.64 ± 0.12 %) adsorption to the tubing. Following dissolution of 18F-AcF in solvent containing base, highly reactive 18F-flouride was generated immediately and used directly for 18F-labeling reactions. These data indicate that 18F-acyl fluorides represent a new paradigm for preparation and transport of anhydrous, reactive 18F-fluoride for radiofluorinations.

Keywords: positron emission tomography, Fluorine-18, 18F-fluorination, radiochemistry, acyl fluoride, radiofluorination

Graphical Abstract Synopsis

Gaseous 18F-acetyl fluoride is prepared by 18F-radiofluorination of acetic anhydride, purified through a column containing Porapak Q/Na2SO4, and transported to radiochemistry apparatuses in nitrogen as a 18F-labeling synthon.

1. Introduction

Positron emitting fluorine-18 (18F, T1/2=109.7 min) is the most commonly employed radioisotope for positron emission tomography (PET) imaging[1]. Its favorable physical decay properties include low positron energy (β+max = 0.635 MeV) and a high positron decay abundance (99%), which afford high resolution PET images. The favorable 109.7 min half-life allows multistep syntheses, extended imaging procedures and transport of 18F-flouride or 18F-labeled tracers between sites. Furthermore, the size of fluorine often allows replacement of hydrogen and hydroxyl groups on molecules with acceptable changes to their biochemical behaviors in important physiological processes. The physical decay properties result in superior spatial resolution of PET images after administration of 18F-labeled compounds in humans and animals [2]. For example, the glucose analog 2-[18F]fluoro-2-deoxy-D-glucose (FDG) is by far the most utilized PET radiotracer. FDG-PET provides noninvasive assessment of regional rates of glucose transport and hexokinase-mediated phosphorylation in body tissues, thus it has diagnostic utility in a wide array of diseases[3].

Although electrophilic fluorination with highly reactive gaseous 18F-F2 or its derivatives played an important historic role in the development of 18F-labeled molecules, it is less favored nowadays because of limits on specific activity caused by added 19F carrier and poor regioselectivity of labeling position. Currently, high specific activity 18F-flouride is routinely produced up to multi-Curie levels by proton irradiation of enriched 18O-water. The aqueous 18F-flouride solution is transported through tubing to the hot-cell for the following radiofluorinations. The current transport method has two major limitations: 1) there is obvious activity loss in the tubing with delivery of 1.5-2.5 mL target solution, which is unfavorable for longer distance deliveries (>10 m). Rinsing of the transport lines with deionized water is helpful to recover the adherent 18F-flouride, but will dilute the isotopic enrichment of recovered 18O-enriched water and results in more time delay; 2) impurities will gradually accumulate in the tubing with time, requiring transport lines to be replaced regularly depending on the usage. Although gaseous 11C-CO2/CH4 transport technologies have obvious advantages over the addressed drawbacks, there is no practical gaseous 18F-carrier available.

In addition to the potential advantages for transportation of 18F-radioactivity in gaseous form, conversion of 18F-flouride to a gaseous, anhydrous form may lead to increases in reactivity in subsequent radiofluorinations. The highly hydrated 18F-flouridein water is a poor nucleophile. The removal of water is proven to be crucial in improving the reactivity in the nucleophilic substitution. 18F-flouride is routinely trapped on solid-phase extraction cartridge, followed by elution with a solution of phase-transfer catalyst crypt and K2.2.2/K2CO3 and successive azeotropic evaporations with acetonitrile. Variations on the Hamacher method have remained the predominant approach for preparation of reactive 18F-fluoride [4]. Anhydrous or “naked” 18F-fluoride may prove useful for certain radiofluorinations. DiMagno et al.[5] reported a method to make anhydrous tetrabutylammonium fluoride by the reaction of hexafluorobenzene with tetrabutylammonium cyanide in the polar aprotic solvents. The anhydrous fluoride showed remarkable reactivity towards a variety of substrates with high yields under mild conditions. However, extension of this technique to 18F was discouraged because the high levels of nonradioactive fluorine would result in poor specific radioactivity of the resultant 18F-labeled compounds. Tewson[6] preliminarily reported a method to make anhydrous 18F-fluoride by reacting highly-purified hexabromobenzene with potassium 18F-fluoride prepared via the dry-down method in acetonitrile followed by passage of the resultant 18F-fluoropentabromobenzene solution over alumina. By reacting with tetrabutylammonium salt, anhydrous 18F tetrabutylammonium fluoride was formed. However, no further investigation was reported.

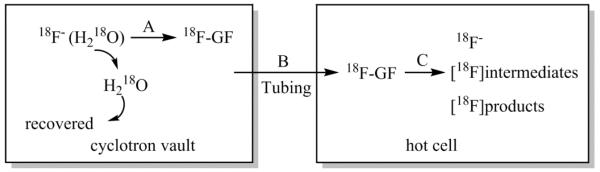

To address the current limitations mentioned above, we have investigated the production and transport of gaseous 18F-labeled acyl fluorides[7] as novel 18F-synthons for preparation of anhydrous 18F-fluoride (Fig. 1). The anhydrous, gaseous 18F-acyl fluorides can be produced in high yield near the cyclotron and transferred rapidly and with negligible radioactivity losses through long delivery lines to radiochemistry hot cells where they can be efficiently converted back to reactive 18F-fluoride salts. This approach is applicable to both vaulted cyclotrons and self-shielded cyclotrons. For self-shielded cyclotrons, a small hot cell is placed near the cyclotron for housing the apparatus to make 18F-acyl fluoride.

Fig. 1.

Concept for production and transfer of gaseous 18F-fluoride (18F-GF, 18F-acyl fluoride) from cyclotron to radiochemistry hot cell. The two steps involved are A) production of 18F-GF in close proximity to the cyclotron, B) transfer to the hot cell, and C) conversion of the 18F-acyl fluoride back to reactive 18F-fluoride for radiofluorinations.

2. Results

2.1. Production, analysis and transport of 18F-Acyl fluorides

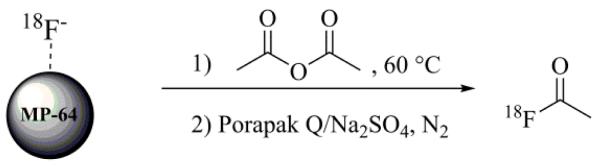

The smallest molecular prototype chosen for application of this concept was 18F-acetyl fluoride (18F-AcF, Bp = 21 °C). 18F-AcF was produced by reaction of 18F-fluoride with acetic anhydride on an anion-exchange column (Scheme 1). 18F-fluoride in 18O-enriched water was efficiently trapped on a column of Lewatit ® MP-64 anion-exchange resin (100 mg in 30 mm × 3 mm ID polypropylene tube) that was previously prepared by rinsing with 1 M K2CO3 (10 mL) and water (10 mL), and then dried under nitrogen. The MP-64 column was maintained at 60 °C within a heated aluminum block. After trapping of the 18F-fluoride, the 18O-enriched water was recovered for recycling. The column was rinsed with 10 mL acetone and dried under nitrogen for 90 s. Acetic anhydride (0.25 mL) was added to the column and allowed to react for 3 min. The resultant gaseous 18F-AcF was swept by nitrogen flow (~25 mL/min) from the MP-64 column through a purification column containing Porapak Q resin (1 g) and sodium sulfate (1 g) and maintained at 30 °C (Fig. 2). The purified 18F-AcF was easily trapped in anhydrous polar organic solvents such as acetonitrile, on solid-phase extraction cartridges such as Oasis WAX, or in a cooled tubing loop at − 40 °C to − 80°C. Radiochemical yields (RCY) of 18F-AcF were 78% ± 3% (n=10) uncorrected for decay over an un optimized synthesis time of 15 min. Corrected yields were 87 ± 3%. Radiochemical and chemical purities were confirmed as >99% by GC-FID (Fig. 3). Chemical purity and radiochemical stability to at least 4 h was demonstrated (Fig. 3). The specific activity of 18F-AcF was determined by quantification of fluoride ions after trapping and decomposition of entire batches of 18F-AcF in 1 mL of 1.75 mM aqueous KOH solution. Flouride quantification was performed the following day using anion chromatography HPLC (Dionex IC-2100). Starting with 18F-fluoride radio activities of approximately 74 GBq, specific activities were found in the range 1210 – 2886 GBq/μmol (n=3). A similar synthetic process was used to produce 18F-propanoyl fluoride (18F-PrF, Bp = 43 °C) from propanoyl anhydride, also in highly efficient and reproducible yields. In the case of 18F-PrF, the temperature of the Porapak Q/sodium sulfate purification column was maintained at 40 °C.

Scheme 1.

Production of 18F-AcFas prototypic gaseous 18F-fluoride.

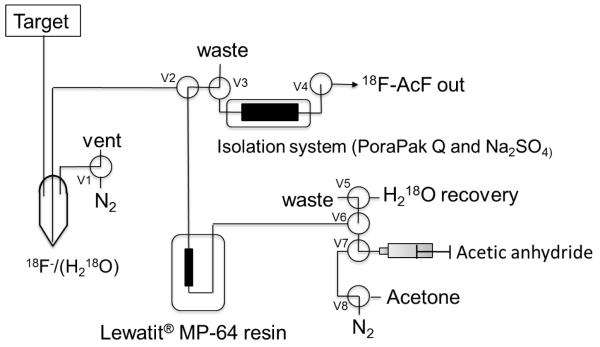

Fig. 2.

Diagram for the production apparatus for 18F-AcF.

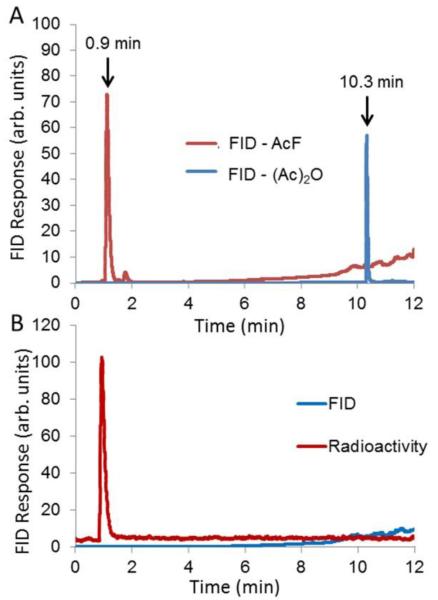

Fig. 3.

A) Gas chromatographs of acetic anhydride (FID) and non radioactive AcF (FID) standards. Acetic anhydride (10 uL) was mixed in 1 mL water immediately before injection. B) Gas chromatograph of 18F-AcF product at4 h after production. The radioactivity peak coincided with the AcF standard peak at 0.9 min. No mass peaks were observed by the FID detector.

18F-AcF was found to be the ideal acyl fluoride to be transported through tubing. 18F-AcF was transported through 15 m of polypropylene (PP) tubing (0.8 mm ID) with 0.64 ±0.12% (n=3) loss. Adsorption of 18F-PrF to 15 m PP tubing was slightly higher (1.4±0.2 %, n=3), while adsorption of 18F-fluoride in water was found to be 5.8±2.0% (n=3) within the same length of tubing. 18F-AcF was easily and efficiently trapped in polar organic solvents such as acetonitrile or on certain solid-phase extraction cartridges as a first step in radiochemical processing. Notably, 18F-AcF was trapped on as little as 5 mg Oasis WAX resin with >98 % efficiency, allowing it to be potentially eluted from the resin in less than 0.1 mL of organic solvents. By this means, anhydrous 18F-AcF is practically concentrated for potential applications in microfluidic radiochemistry.

2.2. Model radiofluorinations using18F-AcF

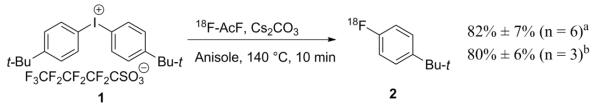

To test the reactivity of gaseous 18F-AcF in radiofluorination, bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium perfluoro-1-butanesulfonate was radiofluorinated with anhydrous 18F-CsF (generated from 18F-AcF and 20 mg Cs2CO3) in 0.3 mL anisole (Scheme 2). The radiochemical yield, assessed by r-TLC (MeOH) and HPLC (Supplemental Data), was found to be 82% ± 7% (n = 6). The results supported the high reactivity for 18F-fluoride derived from 18F-AcF, although radiochemical yield was not significantly improved over the conventional dry-down method. Some other common 18F-radiopharmaceutical precursors were also tested and similar results were obtained (Supplemental Data).

Scheme 2.

Model radiofluorination of diaryliodonium salt with 18F-AcF. aRadiochemical yields from the 18F-AcF method. bRadiochemical yields from the conventional Cs18F/Cs2CO3 dry-down method.

3. Discussion

Anhydrous, gaseous 18F-acyl fluorides were produced conveniently in high yield and transferred rapidly and with negligible radioactivity losses through delivery tubing to radiochemistry hot cells. The gaseous property of acetyl fluoride (Bp = 21 °C) at room temperature is especially suitable to be an anhydrous gaseous 18F-carrier. Using the same radiochemistry conditions presented here, we have recently developed an automated module with the ability to produce up to 12 sequential batches of 18F-acetyl fluoride in 93±5% radiochemical yields[8]. We anticipate such a module can be installed in close proximity to the cyclotron to allow for minimal loss of 18F-fluoride delivered to the module from an aqueous 18F-fluoride target. Batches of gaseous 18F-acyl fluorides could be produced and distributed through stainless tubing to radiochemistry hot cells for radiofluorinations in analogy to distribution of 11C-CO2/CH4 to 11C radiosynthesis units. The gaseous nature of 18F-AcF may allow transfer distances from the cyclotron to radiochemistry hot cell that are unfeasible using liquid transfers, increasing flexibility of siting the cyclotron and radiochemistry laboratory in existing hospital spaces. Transport of purified 18F-acyl fluoride in carrier nitrogen gas may allow use of permanent stainless steel lines rather than polymer 18F-flouride delivery lines that must be replaced every 3 to 12 months, depending on usage levels. Thus, significant savings in labor and cost can be realized. The gaseous form of 18F-acyl fluorides, together with their excellent stability and transportability, also make them suitable for novel short-term storage and use-on-demand scenarios that would not be as practical with 18F-fluoride in aqueous solution. Thus, one production of 18F-acyl fluoride may serve as precursor to several radiofluorinations without the need for separate 18F-fluoride dry-down steps within each process. Furthermore, since 18F-acyl fluorides are practically trapped and released from resins, distribution can be considered from a cyclotron facility to satellite imaging centers equipped only with radiochemistry hot cells and radiochemistry synthesizers that can produce 18F-radiopharmaceuticals on a use-on-demand model. A decentralized model for 18F-radiotracer production has been previously suggested by Keng et al. [9] whereby 18F-fluoride is centrally produced and distributed to various hospital and imaging facilities that are each equipped with automated 18F-processing modules for on-site production of a wide array of 18F-radiopharmaceuticals to meet specific imaging demands. The 18F-acyl fluoride methodology may work well with a decentralized distribution model since it provides 18F in a form that is immediately ready for the radiofluorination reaction and easily fractionated to multiple processes. Finally, the ability to trap 18F-acyl fluorides on small quantities of resins may enable highly efficient preparation of reactive 18F-fluoride in small solution volumes for entry into microfluidic processes and eliminate the need for a separate 18F-fluoride concentrator.

A disadvantage of the 18F-acyl fluoride approach is the added cost and complexity of introducing an 18F-acyl fluoride generating module and distribution system in the radiochemistry laboratory. If the demand for 18F-fluorideis currently met within the cyclotron operating schedule, there may be insufficient incentive to implement a change. Also, most 18F-radiochemistry modules assume input of 18F-fluoride in aqueous solution, so adaptations in the labeling protocol would need to be implemented to eliminate the dry-down procedure and instead trap the 18F-acyl fluoride in a solution containing the labeling precursor and appropriate base. Finally, changes in synthesis procedures may have impact on regulatory aspects for 18F-radiopharmaceuticals being manufactured under governmental approvals.

4. Conclusions

In conclusion, 18F-acyl fluorides were facilely generated from cyclotron-produced 18F-fluoride solution with high yields, purities and specific activities. The prototype molecule, 18F-AcF, was efficiently transported through 15 m of polypropylene tubing. 18F-acyl fluorides are conveniently trapped in organic solvent and converted back to reactive 18F-fluoride for radiofluorination. The beneficial properties 18F-acyl fluorides may enable new paradigms in 18F-radiochemistry, including decentralized production of 18F-radiopharmaceuticals and microfluidics applications.

5. Experimental

5.1. General procedures

Lewatit® MP-64 chloride form resin used for trapping of 18F-fluoride was procured from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, Mo) preconditioned by rinsing with 1 M K2CO3 (10 mL) and water (10 mL), and then dried under nitrogen before use. Acetone, acetic anhydride, propionic anhydride, bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium perfluoro-1-butanesulfonate, sodium sulfate and potassium carbonate were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. Kryptofix2.2.2, were purchased from ABX (Radeberg, Germany). Oasis wax resin was ordered from Waters. The non-radioactive acetyl fluoride cylinder was purchased from Synquest labs. The radiochemical yields of 18F-AcF were calculated from the starting radioactivity and final trapped radioactivity after trapping in appropriate solvents. The radiochemical yields for the other products were measured using silica-gel TLC and a Mini-scan radio-TLC scanner (Bioscan) and the radiochemical identity of the products were confirmed by HPLC with radioactivity detector (Shimadzu-AV20, Phenomenex Luna C-18 analytical column: 4.7 × 250 mm).

5.2. Chemical/radiochemical purity and specific activity of 18F-acetyl fluoride (18F-AcF)

Gas chromatography with flame-ionization detection (GC-FID) was performed using an SRI 8610C GC (SRI Instruments, Torrence, CA) with helium carrier gas flow at 10 cc/min through an MXT-WAX column (Restek, Bellefonte, PA, 0.53 mm ID, 30 m length). The temperature program was 3 min at 30 °C, followed by a temperature ramp of 10 °C per min to a maximum of 250 °C. Since no mass peaks were observed on GC-FID of the product 18F-AcF (Fig. 3), we estimated a lower limit of the specific activity by determination of the minimum detection limit of nonradioactive AcF. AcF (0.5 mL) was diluted into 2.19 L of nitrogen. The detection limit of AcF on GC-FID was determined by gradually decreasing the injection volume until no AcF peak was detected. We found the detection limit to be 1.057 × 10−5 umol using a 10 uL injection. Second, with starting 18F-radioactivity of 1.5 GBq, 0.85 GBq 18F-AcF was obtained and trapped in a 60 mL syringe. After 4 h decay, 10 uL sample from the syringe was injected onto the GC. No AcF or impurity peaks were found (Fig. 3). Radiochemical purity was determined by addition of a flow-through radiation detector at the end of the GC column (Carroll and Ramsey Associates, Berkeley, CA). A single radioactivity peak was observed at approximately the same time as the GC-FID peak for nonradioactive AcF (0.9 min), accounting for the added delay to pass through the radioactivity monitor. To measure the specific activity of 18F-AcF, 2.5 mL 18O-H2O was irradiated at 65 uA for 30 min and the 18F-flouride solution (approximately 74 GBq) was delivered to the radiochemistry module. 18F-AcF was produced as the procedures above and quenched directly into a KOH aqueous solution (1 mL, 1.75 mM) to release 18F-flouride. The resulting solution was allowed to decay overnight and then analyzed byanion chromatography HPLC with radioactivity detector (Dionex IC-2100, AS19 analytical column: 4.7 × 150 mm; eluent: 1.75 mM KOH; sample volume: 25 μL; flow rate: 1 mL/min; retention times: 5.8 min for 19F-flouride, 6 min for 18F-flouride).

5.3. Experimental procedures for 18F-fluorination

5.3.1. 18F-Flourination with conventional method (method A)

18F-fluoride (30 to 111 MBq) in 18O-enriched water was trapped on the QMA light cartridge (46 mg). The QMA cartridge was eluted with a solution of cesium carbonate (20 mg), in 0.15 mL water and 0.85 mL acetonitrile. After initial dry down of the solution, further drying was performed by azeotropic drying after additions of acetonitrile (0.4 mL × 2) at 90 °C under a flow of N2. To the residue was added 0.3 mL anisole and the labeling precursor, then the mixture was heated at different temperatures and reaction times to match the fluorination conditions used for 18F-AcF. Bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium perfluoro-1-butanesulfonate (15 mg) in anisole (0.3 mL) were used and the mixture was heated at 140 °C for 10 min. The reaction mixture was cooled and monitored with TLC (methanol) and identified by HPLC (80% AcN/ 20% water, flow = 1 ml/min). The radiochemical yields were 80% ± 6% (n = 3).

5.3.2. 18F-Flourination with 18F-AcF method (method B)

18F-AcF (30 to 111 MBq), synthesized as above, was trapped in anisole. Bis(4-tert-butylphenyl)iodonium perfluoro-1-butanesulfonate (15 mg) and cesium carbonate (20 mg) in anisole (0.3 mL) were used and the mixture was heated at 140 °C for 10 min. The reaction mixture was cooled and monitored with TLC (methanol) and HPLC (Supplemental Data). The radiochemical yields were 82% ± 7% (n = 6).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

18F-acyl fluorides are developed to serve as gaseous radiofluorination synthons.

Prototypic 18F-acetyl fluoride (18F-AcF) is prepared in high radiochemical yield (>86%).

Specific radioactivities of >1200 GBq/μmol for 18F-AcF are achieved.

18F-AcF is transported in polypropylene tubing with low adsorption (~0.6% in 15 m).

18F-AcF is a successful synthon for 18F-radiofluorinations.

Acknowledgements

The work was supported by the Department of Radiology, Mayo Clinic and by the Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering of the National Institutes of Health under award number R01 EB015536. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. SGD is a shareholder in Ground Fluor Pharmaceuticals, Inc., of Lincoln, NE (GFP). GFP has licensed US patent # 8,604,213 (Fluorination of Aromatic Ring Systems) from the University of Nebraska.

Footnotes

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary data associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at [to be completed by editor]

References

- [1](a).Ametamey SM, Honer M, Schubiger PA. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:1501–1516. doi: 10.1021/cr0782426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Miller PW, Long NJ, Vilar R, Gee AD. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:8998–9033. doi: 10.1002/anie.200800222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Phelps ME. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:9226–9233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.16.9226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hoh CK. Nucl. Med. Biol. 2007;34:737–742. doi: 10.1016/j.nucmedbio.2007.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4](a).Cai L, Lu S, Pike VW. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2008;17:2853–2873. [Google Scholar]; (b) Li Z, Conti PS. Adv. Drug. Del. Rev. 2010;62:1031–1051. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Lee E, Kamlet AS, Powers DC, Neumann CN, Boursalian GB, Furuya T, Choi DC, Hooker JM, Ritter T. Science. 2011;334:639–642. doi: 10.1126/science.1212625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5](a).Sun H, DiMagno SG. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:2050–2051. doi: 10.1021/ja0440497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Sun H, DiMagno SG. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:2720–2725. doi: 10.1002/anie.200504555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6](a).Tewson T. 18th International Symposium on Radiopharmaceutical Sciences; Edmonton, Alberta. July 2009. [Google Scholar]; (b) Tewson T. American Chemical Society Meeting; Boston, Massachusetts. August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- [7].Jiang H, DeGrado TR. J. Nucl. Med. 2014;55:S1, 161. [Google Scholar]

- [8].DeGrado TR, Nathan G, Jiang H, Label J. Compd. Radiopharm. 2015;58:S200. [Google Scholar]

- [9].Keng PY, Esterby M, Van Dam RM. Emerging technologies for decentralized production of PET tracers. Positron Emission Tomography-Current Clinical and Research Aspects [Online] In: Hsieh Chia-Hung., editor. InTech. 2012. pp. 153–182. ISBN: 978-953-307-824-3. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.