Abstract

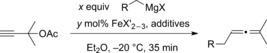

Presented herein is a mild, facile, and efficient iron‐catalyzed synthesis of substituted allenes from propargyl carboxylates and Grignard reagents. Only 1–5 mol % of the inexpensive and environmentally benign [Fe(acac)3] at −20 °C was sufficient to afford a broad range of substituted allenes in excellent yields. The method tolerates a variety of functional groups.

Keywords: allenes, chirality, cross-coupling, Grignard reagents, iron

The formation of carbon–carbon or carbon–heteroatom bonds by transition‐metal‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reactions has become one of the most important tools in organic chemistry,1 and it has been used in a plethora of total syntheses.2a–2c The transition‐metal‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reaction is appreciated by academia as well as in industry.3 Despite its usefulness, the catalysts employed are mostly based on expensive noble metals such as palladium. Regardless of the undeniably practical properties of these noble metals, iron has favorable features. In addition to the environmental and toxicological aspects, iron catalysts perform well in C−C cross‐couplings, especially when it comes to sp3‐carbon centers. Also, in the last quarter‐century the iron‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reaction has witnessed a great revival and research interest has been growing ever since.4a–4d

Given the vast range of methodologies developed in our group, such as carbocyclization of enallenes,5a–5f allenynes,6 and arylallenes,7 as well as the dynamic kinetic resolution (DKR) of 2,3‐allenols,8 new methods for the preparation of substituted allenes are necessary. Allenes are cumulated unsaturated hydrocarbons found in over 150 natural compounds and in marketed drugs.9 Allenes are also employed in many other areas, such as total synthesis,9, 10a–10c and have become indispensable building blocks in organic chemistry.11a–11f Therefore, we considered the development of an iron‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reaction of propargyl carboxylates and Grignard reagents for the synthesis of allenes to be of general interest.

One of the oldest and most common routes to obtain an allene is by cross‐coupling between organometallic compounds, for example, a Grignard reagent, and propargylic derivatives, such as halides,12 sulfonates,13 acetates,14 or epoxides,15 with the use of copper as either catalyst or mediator. The copper‐catalyzed reactions have generally been performed in a stoichiometric fashion but catalytic variants have also emerged.16a–16e However, the latter catalytic methods are rather limited in their substrate scope and terminal acetylenes remain challenging under these reaction conditions. For a more general approach it is still common to use the conservative noncatalytic route to prepare starting materials17a–17c or intermediates in organic synthesis.18a–18c Hence, the prior preparation of cuprates render this method less practical.

Since iron readily forms highly reactive species, even at temperatures below 0 °C,19 we found it fit to be used as a nonprecious metal for the cross‐coupling of Grignard reagents with propargylic substrates. Little is known for this type of iron‐catalyzed reaction. A literature search revealed only a few reports regarding propargylic substrates with leaving groups such as, sulfonates20 and halides.21a,21b Also, a recent method utilized an alkynyl epoxide with its high ring strain as a convenient nucleofuge.22

As we wished to employ an easily accessible and more stable starting material than those previously used, we decided to use a carboxylate, for example, acetate, as a suitable leaving group. This type of leaving group has recently been used in an iron‐catalyzed vinylation23a,23b and allylation24 reaction with Grignard reagents. A wide variety of propargyl acetates are readily accessible either directly from commercially available propargyl alcohols or by one‐pot procedures through the addition of either a lithium or magnesium acetylide to either an aldehyde or ketone with subsequent esterification.

Our investigations began with optimization of the two types of Grignard reagents (Table 1), that is, benzylmagnesium chloride (R=Ph), having no β‐hydrogen atoms, and 2‐phenylethylmagnesium chloride (R=Bn), possessing β‐hydrogen atoms. The 2‐phenylethylmagnesium chloride was chosen solely for optimization because it is a difficult substrate as a result of its tendency to undergo β‐hydride elimination.

Table 1.

Optimization of coupling conditions.[a]

| R | Equiv | Iron cat. | mol % of cat. | Additive | Yield [%][a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ph[b] | 1.25 | none | – | – | 0 |

| 1.25 | [Fe(acac)2] | 5 | – | 63 | |

| 1.25 | [Fe(acac)3] | 5 | – | 94 | |

| 1.5 | [Fe(acac)3] | 5 | – | 93 | |

| 1.25 | FeCl3 | 5 | – | 82 | |

| 1.25 | [Fe(acac)3] | 5 | NMP[e] | 53 | |

| 1.25 | [Fe(acac)3] | 5 | TMEDA[e] | 25 | |

| Bn[c] | 1.25 | none | – | – | 0 |

| 1.25 | [Fe(acac)2] | 5 | – | 50 | |

| 1.25 | [Fe(acac)3] | 1 | – | 66 | |

| 2.5 | [Fe(acac)3] | 1 | – | 67 | |

| 1.25[d] | [Fe(acac)3] | 1 | – | 47 | |

| 1.25 | [Fe(acac)3] | 1 | NMP[e] | 49 |

[a] Reaction conditions: 0.2 m solution of propargyl acetate (1 mmol) in Et2O with dropwise addition of Grignard reagent during 5 min. Yield was determined by NMR spectroscopy. [b] X=Cl. [c] X=Br. [d] Addition during 30 sec. [e] Used 0.5 equivalents of additive. acac=acetylacetonate.

During the optimization of the cross‐coupling reaction, the Grignard reagents with β‐hydrogen atoms required a catalyst loading of 1 mol %, whereas for the ones without β‐hydrogen atoms a loading of 5 mol % was required (Table 1).25 The reaction did not benefit from additives, such as N‐methylmorpholine (NMP) and N,N,N,N‐tetramethylethylenediamine (TMEDA). The β‐hydride elimination is an intrinsic problem, which could not be completely circumvented. Even the application of an N‐heterocyclic carbene ligand did not suppress the β‐hydride elimination.23a

However, the striking beauty of the iron‐catalyzed preparation of substituted allenes described herein is the simplicity, the mild reaction conditions, and the general applicability.

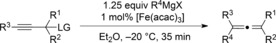

Once we established a workable procedure for both classes of substrates, the steric effect of the substituents on the propargyl ester was investigated. For Grignard reagents without β‐hydrogen atoms we found that the more substituted substrates afforded the expected product in good to high yields (Table 2, entries 1–9) whereas less substituted substrates gave poor yields (entries 10 and 11). The reaction conditions allow the presence of not only terminal acetylenes but also functional groups such as cyclopropyl, acetal, silyl ether, and ethyl carboxylate (entries 2–4 and 8).

Table 2.

Grignard reagents without β‐hydrogen atoms.

| Entry | Carboxylate | Grignard reagent | Allene | Yield [%][a] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

94 |

| 2 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

86 |

| 3 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

86 |

| 4 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

77 |

| 5 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

92 |

| 6 |

|

|

|

99 |

| 7 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

97 |

| 8 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

64 |

| 9 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

79[b] (67)[c] |

| 10 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

33 |

| 11 |

|

BnMgCl |

|

14 |

[a] Yield of product isolated from the reaction run using a 0.2 M solution of propargyl carboxylate (1–2 mmol) in Et2O, with dropwise addition of the Grignard reagent during 5 min. [b] From 0.5 mmol of substrate (R=Ac); by‐product not isolated. For a reaction run with 0.25 mmol of substrate (R=Ac): 71 % yield with SN2 by‐product isolated (12 %). [c] From 0.5 mmol of substrate (R=Piv) with 13 % of the isolated SN2 by‐product. Cy=cyclohexyl, LG=leaving group, Piv=pivaloyl, TBS=tert‐butyldimethylsilyl.

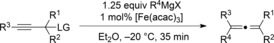

Magnesium organyls, containing β‐hydrogen atoms (Table 3), performed well with Grignard reagents, such as phenylpropylmagnesium chloride, which are less prone than 2‐phenylethylmagnesium chloride to undergo β‐hydride elimination. Also both cyclohexyl and unsaturated magnesium reagents performed well in this reaction (entries 6, 7, and 10). For less substituted propargyl substrates different carboxylates were employed (entry 14) but no significant improvement was achieved. However, it was shown that, for example, pivalate was a suitable leaving group, and especially practical for more volatile substrates (entries 13 and 14).

Table 3.

Grignard reagents with β‐hydrogen atoms.

| Entry | Carboxylate | Grignard reagent | Allene | Yield [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

|

93 |

| 2 |

|

|

|

68 |

| 3 |

|

|

|

64 |

| 4 |

|

|

|

75 |

| 5 |

|

|

|

78 |

| 6 |

|

CyMgCl |

|

71 |

| 7 |

|

|

|

63 |

| 8 |

|

|

|

90 |

| 9 |

|

|

|

70 |

| 10 |

|

|

|

61 |

| 11 |

|

|

|

61 |

| 12 |

|

|

|

31[b] (24)[c] 44[b] (34)[c] |

| 13 |

|

|

|

39 |

| 14 |

|

|

|

25(Bz) 24(Piv) 14(Ac) |

[a] Yield of product isolated from the reaction run with a 0.2 m solution of propargyl carboxylate (1–2 mmol) in Et2O, with dropwise addition of the Grignard reagent during 5 min. [b] From 0.25 mmol of substrate (R=Piv). [c] From 0.5 mmol of substrate (R=Ac).

As anticipated, Grignard reagents which undergo β‐hydride elimination (Table 3) performed less well than Grignard reagents without β‐hydrogen atoms (Table 2). Grignard reagents with β‐hydrogen atoms are more likely to give SN2 regioisomers with nonterminal disubstituted propargylic carboxylates (Table 3, entry 12).

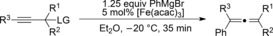

The catalytic conditions which were optimized for propargyl substrates lacking β‐hydrogen atoms also worked well for PhMgBr (Table 4). While the trisubstituted propargyl carboxylate gave a high yield (entry 1), the trisubstituted allene (entry 3) was obtained in a moderate yield. Overall, the trend shows that tri‐ and tetrasubstituted allenes are obtained in excellent yields whereas yields decreased rather rapidly for less substituted allenes.

Table 4.

Iron‐catalyzed arylation.

| Entry | Carboxylate | Allene | Yield [%][a] |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

|

|

92 |

| 2 |

|

|

84 |

| 3 |

|

|

56 |

| 4 |

|

|

41 |

[a] Yield of product isolated from reaction run with a 0.2 m solution of propargyl carboxylate (1–2 mmol) in Et2O, with dropwise addition of the Grignard reagent during 5 min.

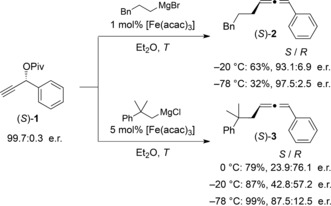

To assess the transfer of chirality from an enantiomerically enriched substrate, (S)‐3‐phenylpropynyl pivalate [(S)‐1] was synthesized by kinetic resolution and esterification and obtained with an enantiomeric ratio (e.r.) of 99.7:0.3. A Grignard reagent of each type, one with and one without a β‐hydrogen atom, was employed (Scheme 1). At a temperature of −20 °C a relatively high e.r. value of 93.1:6.9 of (S)‐2 was achieved with the β‐hydrogen‐atom‐containing 3‐phenylpropylmagnesium bromide. Performing the experiments at −78 °C led to a considerable improvement in chirality transfer (97.5:2.5 e.r.). Remarkably, 2‐methyl‐2‐phenylpropyl Grignard causes a reversal of the e.r. value between the reaction temperatures of 0 °C and −78 °C. At 0 °C the R‐configured enantiomer is predominantly formed whereas at −78 °C the S‐configured enantiomer [(S)‐3] is formed in 87.5:12.5 e.r. Moreover, it is notable that the copper‐mediated reactions of both Grignard reagents at −20 °C performed comparably to that of the corresponding iron‐catalyzed reactions run at −78 °C.26

Scheme 1.

Experiment to evaluate the transfer of chirality (for determination of absolute stereochemistry see the Supporting Information).

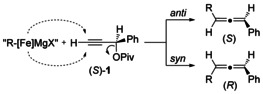

Ever since Kochi's studies in the early 1970s,27 many different mechanisms for iron‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reactions have been put forward, and they are either based on radical28a–28e or polar19, 29a–29e intermediates. Different oxidation states of the catalytically active species, down to Fe−2,19 have also been proposed.30 It has been found that substrates with β‐hydrogen atoms behave differently from those lacking β‐hydrogen atoms.19, 30 Iron‐catalyzed cross‐coupling reactions often show radical character, as determined by either radical probes31 or the transfer of chirality. The cross‐coupling involving a cyclopropyl‐substituted propargyl acetate (entry 2 of both Tables 2 and 4) showed no product resulting from the radical ring‐opening of the cyclopropane, thus ruling out the formation of a radical intermediate from the propargyl ester. Only in the case of phenylpropyl Grignard, having β‐hydrogen atoms (Table 3, entry 2), is a mixed fraction of several products (10 %) observed, and thus might result from a partial opening of the cyclopropane ring. Furthermore, employing 5‐hexenylmagnesium bromide (Table 3, entry 7) did not result in the formation of a cyclopentyl moiety as would be expected from an intermediate radical species. These results seem to either rule out a radical intermediate or point towards an extremely short‐lived radical species (Scheme 1).

Hence, the mechanism is proposed to proceed by either syn or anti SN2′ attack by an organoiron intermediate (Scheme 2, dashed arrows), in analogy to the related copper‐mediated reaction.32a–32c The final allene product is then formed by reductive elimination. The partial loss of enantiomeric excess is thought to result from both pathways acting simultaneously, as in the case of epoxy leaving groups in iron catalysis.22 Notably, in the particular case of the 2‐methyl‐2‐phenylpropyl Grignard reagent, a temperature‐dependent syn versus anti attack was observed, thus reversing the e.r. value (S/R) from 23.9:76.1 at 0 °C to 87.4:12.6 at −78 °C (Scheme 1). For the remaining loss in e.r., a radical intermediate cannot be completely ruled out.

Scheme 2.

Proposed mechanism for transfer of chirality.

In conclusion, we have developed a mild and convenient iron‐catalyzed synthesis of substituted allenes from propargyl carboxylates and Grignard reagents. We showed the applicability of various substituted propargyl carboxylates, different types of Grignard reagents, and the functional‐group tolerance. Moreover, we explored the radical character and mechanism of the reaction by using radical probes and observing the transfer of chirality.

Dedicated to Professor Andreas Pfaltz

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary

Acknowledgements

Financial support from the European Research Council (ERC AdG 247014), the Swedish Research Council (621‐2013‐4653), and the Berzelii Centre EXSELENT is gratefully acknowledged.

S. N. Kessler, J.-E. Bäckvall, Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 3734.

References

- 1. Metal-Catalyzed Cross-Coupling Reactions and More (Eds.: A. de Meijere, S. Bräse, M. Oestreich), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.

- 2a. Nicolaou K. C., Bulger P. G., Sarlah D., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 4442; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2005, 117, 4516; [Google Scholar]

- 2b. Standley E. A., Tasker S. Z., Jensen K. L., Jamison T. F., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1503; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2c. Kapdi A. R., Prajapati D., RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 41245. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Transition Metal-Catalyzed Couplings in Process Chemistry (Eds.: J. Magano, J. R. Dunetz), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 4.

- 4a. Bolm C., Legros J., Le Paih J., Zani L., Chem. Rev. 2004, 104, 6217; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4b. Iron Catalysis in Organic Chemistry (Ed.: B. Plietker), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2008; [Google Scholar]

- 4c. Bauer I., Knölker H.-J., Chem. Rev. 2015, 115, 3170; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4d. Enthaler S., Junge K., Beller M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008, 47, 3317; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2008, 120, 3363. [Google Scholar]

- 5.

- 5a. Franzén J., Bäckvall J.-E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2003, 125, 6056; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5b. Persson A. K. Å., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010, 49, 4624; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2010, 122, 4728; [Google Scholar]

- 5c. Persson A. K. Å., Jiang T., Johnson M. T., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 6155; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2011, 123, 6279; [Google Scholar]

- 5d. Deng Y., Bartholomeyzik T., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 6283; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 6403; [Google Scholar]

- 5e. Jiang T., Bartholomeyzik T., Mazuela J., Willersinn J., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6024; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 6122; [Google Scholar]

- 5f. Zhu C., Yang B., Jiang T., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 9066; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 9194. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Deng Y., Bartholomeyzik T., Persson A. K. Å., Sun J., Bäckvall J.-E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 2703; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 2757. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Mazuela J., Banerjee D., Bäckvall J.-E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 9559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Deska J., del Pozo Ochoa C., Bäckvall J.-E., Chem. Eur. J. 2010, 16, 4447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hoffmann-Röder A., Krause N., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 1196; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 1216. [Google Scholar]

- 10.

- 10a. Yu S., Ma S., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 51, 3074; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2012, 124, 3128; [Google Scholar]

- 10b. Villa R. A., Xu Q., Kwon O., Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 4634; [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10c. Meng F., McGrath K. P., Hoveyda A. H., Nature 2014, 513, 367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.

- 11a. Hashmi A. S. K., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000, 39, 3590; [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2000, 112, 3737; [Google Scholar]

- 11b. Ma S., Acc. Chem. Res. 2003, 36, 701; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11c. Ma S., Chem. Rev. 2005, 105, 2829; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11d. Brummond K., DeForrest J., Synthesis 2007, 795; [Google Scholar]

- 11e. Yu S., Ma S., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 5384; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11f.Issue 9 Chem. Soc. Rev 2014, 43, 2879.

- 12. Pasto D. J., Chou S.-K., Fritzen E., Shults R. H., Waterhouse A., Hennion G. F., J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 1389. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Vermeer P., Meijer J., Brandsma L., Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas 2010, 94, 112. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rona P., Crabbe P., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1968, 90, 4733. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Herr R. W., Wieland D. M., Johnson C. R., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1970, 92, 3813. [Google Scholar]

- 16.

- 16a. Wan Z., Nelson S. G., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 10470; [Google Scholar]

- 16b. Tang X., Woodward S., Krause N., Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009, 2836; [Google Scholar]

- 16c. Ohmiya H., Yokobori U., Makida Y., Sawamura M., Org. Lett. 2011, 13, 6312; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16d. Nakatani A., Hirano K., Satoh T., Miura M., Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 2586; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16e. Uehling M. R., Marionni S. T., Lalic G., Org. Lett. 2012, 14, 362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.

- 17a. Mukai C., Ohta Y., Oura Y., Kawaguchi Y., Inagaki F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134, 19580; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17b. Diaf I., Lemière G., Duñach E., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 4177; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 4261; [Google Scholar]

- 17c. Kawaguchi Y., Yasuda S., Kaneko A., Oura Y., Mukai C., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2014, 53, 7608; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2014, 126, 7738. [Google Scholar]

- 18.

- 18a. Gao Z., Li Y., Cooksey J. P., Snaddon T. N., Schunk S., Viseux E. M. E., McAteer S. M., Kocienski P. J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009, 48, 5022; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 5122; [Google Scholar]

- 18b. Kobayakawa Y., Nakada M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 7569; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2013, 125, 7717; [Google Scholar]

- 18c. Rao N. N., Cha J. K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137, 2243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fürstner A., Martin R., Krause H., Seidel G., Goddard R., Lehmann C. W., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130, 8773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Hashmi A. S. K., Szeimies G., Chem. Ber. 1994, 127, 1075. [Google Scholar]

- 21.

- 21a. Pasto D. J., Hennion G. F., Shults R. H., Waterhouse A., Chou S.-K., J. Org. Chem. 1976, 41, 3496; [Google Scholar]

- 21b. Pasto D. J., Chou S.-K., Waterhouse A., Shults R. H., Hennion G. F., J. Org. Chem. 1978, 43, 1385. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fürstner A., Méndez M., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003, 42, 5355; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2003, 115, 5513. [Google Scholar]

- 23.

- 23a. Li B.-J., Xu L., Wu Z.-H., Guan B.-T., Sun C.-L., Wang B.-Q., Shi Z.-J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 14656; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23b. Gärtner D., Stein A. L., Grupe S., Arp J., Jacobi von Wangelin A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 10545; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2015, 127, 10691. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mayer M., Czaplik W. M., Jacobi von Wangelin A., Adv. Synth. Catal. 2010, 352, 2147. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Control experiments ruled out that traces of copper (0.5 ppm) in [Fe(acac)3] could be the active catalyst (see the Supporting Information).

- 26.The corresponding copper-mediated reaction at −20 °C gave an e.r. value of 95.8:4.2 for (S)-2 and 86.6:13.4 for (S)-3 (see the Supporting Information).

- 27. Tamura M., Kochi J. K., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1971, 93, 1487. [Google Scholar]

- 28.

- 28a. Nakamura M., Matsuo K., Ito S., Nakamura E., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004, 126, 3686; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28b. Bedford R. B., Bruce D. W., Frost R. M., Hird M., Chem. Commun. 2005, 4161; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28c. Guérinot A., Reymond S., Cossy J., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 6521; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 6641; [Google Scholar]

- 28d. Noda D., Sunada Y., Hatakeyama T., Nakamura M., Nagashima H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 6078; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28e. Hedström A., Izakian Z., Vreto I., Wallentin C.-J., Norrby P.-O., Chem. Eur. J. 2015, 21, 5946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.

- 29a. Fürstner A., Leitner A., Méndez M., Krause H., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002, 124, 13856; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29b. Fürstner A., Leitner A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2002, 41, 609; [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2002, 114, 632; [Google Scholar]

- 29c. Martin R., Fürstner A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004, 43, 3955; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2004, 116, 4045; [Google Scholar]

- 29d. Fürstner A., Martin R., Chem. Lett. 2005, 34, 624; [Google Scholar]

- 29e. Cahiez G., Habiak V., Duplais C., Moyeux A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2007, 46, 4364; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. 2007, 119, 4442. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Bedford R. B., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 1485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Newcomb M. in Radicals in Organic Synthesis (Eds.: P. Renaud, M. P. Sibi), Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2001, pp. 316–336. [Google Scholar]

- 32.

- 32a. Elsevier C. J., Vermeer P., J. Org. Chem. 1989, 54, 3726; [Google Scholar]

- 32b. Alexakis A., Marek I., Mangeney P., Normant J. F., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990, 112, 8042; [Google Scholar]

- 32c. Alexakis A., Pure Appl. Chem. 1992, 64, 387. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supplementary