Abstract

Three studies examined the implications of a model of affect as information in persuasion. According to this model, extraneous affect may have an influence when message recipients exert moderate amounts of thought, because they identify their affective reactions as potential criteria but fail to discount them as irrelevant. However, message recipients may not use affect as information when they deem affect irrelevant or when they do not identify their affective reactions at all. Consistent with this curvilinear prediction, recipients of a message that either favored or opposed comprehensive exams used affect as a basis for attitudes in situations that elicited moderate thought. Affect, however, had no influence on attitudes in conditions that elicited either large or small amounts of thought.

Persuasive communications can have an impact on the attitudes of a recipient not only when they present compelling arguments in support of the message’s recommendation but also when they trigger nonelaborative mechanisms (Petty & Cacioppo, 1986; for other models of information processing, see Fazio, 1990; Fiske & Neuberg, 1990; Wilson, Lindsey, & Schooler, 2000). For example, pleasant music in a commercial may be objectively irrelevant to the merits of a product but can still generate favorable attitudes toward the product provided the positive affect it induces biases recipients’ judgments (for a comprehensive review of the influences of affect, see Clore, Schwarz, & Conway, 1994; Eagly & Chaiken, 1993). The mechanisms that underlie the influence of affect in persuasion involve, in part, the use of affect as information (see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; DeSteno, Petty, Wegener, & Rucker, 2000; Ottati & Isbell, 1996). According to Schwarz and Clore (1983), people use affect as information just as they use any other criterion. In doing so, they attempt to determine the informational value of their affective reactions to the judgment at hand. If they believe that their feelings are a sound basis for judgment, they use them in forming their attitudes. If they believe that these feelings are irrelevant, they exclude them from consideration.

Clore et al. (1994) as well as Petty, Schumann, Richman, and Strathman (1993) assumed that people use affect as information (particularly extraneous affect) when they lack the ability and motivation to think about the issues being considered. There are two explanations for this prediction. First, people may consider affect when they are unable or unwilling to process more complex information, such as the arguments contained in the persuasive message (see Petty & Wegener, 1999). In addition, people with low motivation and ability may fail to determine that their extraneous affective reactions are irrelevant to the judgment they are about to make, and, consequently, affect may have an influence. In any event, this prediction assumes that the use of affect as information involves a single stage of relevance assessment.

It seems likely, however, that the use of affect as information involves (a) identification of the affective reactions and (b) determination that these reactions are pertinent or not pertinent for a given judgment. People must first direct attention to the affect they experience, and only then may they decide whether their affect is relevant to their attitudes concerning the behavior the message advocates (for related hypotheses, see Gasper & Clore, 2000; Gilbert & Hixon, 1991; Gohm & Clore, 2000). Conceptualizing the use of affect as information as a two-stage process has important implications for our understanding of the influences of extraneous affect in persuasion. For example, it suggests that extraneous affect may have an influence when people become sensitive to their affective states but fail to discount them as a basis for judgment. However, affect is unlikely to have an influence when people identify their affective reactions and discount them or, alternatively, when they do not identify these reactions in the first place.

Conceptualizing affect as information as a two-stage process also has implications for the influence of ability and motivation to think about the issues being considered. Because decreases in ability and motivation disrupt affect identification as well as discounting, they have antagonistic influences on the impact of affect. That is, up to a point, increases in ability and motivation increase the influence of affect because they facilitate affect identification. Beyond that point, however, decreases in ability and motivation decrease the influence of affect because they prevent people from identifying the affect to begin with. Consequently, people use affect as information to a greater extent when their ability and motivation to think about their affect are moderate rather than high or low. No other model of attitude change or affect makes this nonmonotonic prediction. We examined the plausibility of this model in a series of persuasion experiments in which ability and motivation were manipulated to achieve several levels of amount of thought (high, moderate, and low).

It is important to note that the present article restricts consideration to inferential influences of extraneous affect in the context of a judgment about the issue a message advocates. However, affect may have other, more automatic influences as well. For example, some researchers propose that affect can bias encoding and recall of information in persuasion and other types of information processing (see Petty et al., 1993). In addition, affective reactions often trigger automatic, reflex-like responses of approach or avoidance (Doob, 1947). Our work does not concern these processes but instead focuses on affect as information.

The Proposed Model

Schwarz and Clore (1983; see also Clore, Gasper & Garvin, 2001; Wyer & Carlston, 1979; Wyer, Clore, & Isbell, 1999) have long argued that affective states serve as information when judgments are made and are a relatively direct basis for attitudes. For example, when people are asked to report how much they like a product, they may base their judgment on their feelings about the product instead of reviewing its specific features (J. B. Cohen, 1990). More generally, individuals may make judgments of virtually any target by assessing their feelings at that time and using those feelings as a basis for their attitudes (Wyer et al., 1999). In doing so, they may identify affect coming from extraneous sources and assume that their feelings were elicited by the target under consideration.

People’s attitudes toward the behavior advocated in a persuasive message may be informed by affect from two sources. For example, the mere mention of the behavior being advocated may spontaneously elicit affect, and this affect may contribute to one’s reported attitude toward the behavior independently of the implications of the message content. Both Bargh (1997) and Fazio (1990) reported evidence that mere exposure to an attitude object (e.g., the behavior the message recommends) can be sufficient to stimulate a spontaneous evaluative reaction to it. Transitory situational factors that are objectively irrelevant to the message may elicit affect that recipients experience and attribute to the behavior the message advocates. As several studies by Schwarz and his colleagues indicate (for reviews, see Clore et al., 1994; Schwarz, Bless, & Bohner, 1991; Schwarz & Clore, 1996), people cannot always distinguish between the affect that is elicited by a particular referent and the affect they happen to be experiencing for other reasons (e.g., the weather, music, or a recalled past experience). In those situations, affect can inform attitudes and be reflected in behavioral intentions and actual behavior decisions as well (see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001).

In this research, participants experiencing positive or negative affect read a strong or weak persuasive message that either supported or opposed the institution of comprehensive exams. Messages in support of the exams argued that the institution of the policy would bring about positive outcomes, whereas messages opposing the policy argued that the exams would trigger unfavorable consequences and that recipients should veto them in an upcoming referendum. To examine the consequences of ability and motivation, we first systematically varied the distraction participants experienced at the time they read the persuasive message as well as the personal relevance of the persuasive message. Participants read the persuasive message while listening to distracting or nondistracting material (low- vs. high-ability conditions). Some participants were told that the topic of the message was relevant to them (high motivation) and were thus motivated to think about the issues at hand, whereas others believed the policy would have no impact on their life (low motivation). Consequently, the two levels of ability and the two levels of motivation in combination allowed us to examine the effects of affect as information as a function of high, moderate, and low degrees of thinking (respectively, high ability and motivation; low ability and high motivation or high ability and low motivation; and low ability and motivation; for other uses of multiple variables that have additive effects on processing, see Wyer, 1974). In a supplementary experiment, we also manipulated ability (distraction) over three levels (low, moderate, and high) while keeping motivation (relevance) constant at a moderate level. When one manipulates both ability and motivation to generate several levels of amount of thought, a curvilinear influence of amount of thought on the use of affect as information should be apparent in a significant statistical interaction among affect, ability, and motivation. When one manipulates ability over three levels, a curvilinear influence of amount of thought on the use of affect as information should be reflected in a main effect of ability. In sum, both a combination of two levels of ability and two levels of motivation as well as a manipulation of ability over several levels are useful to obtain three different levels of amount of thought.

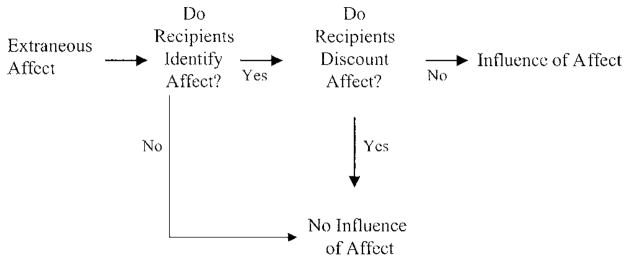

A model for understanding the influence of affect in persuasion appears in Figure 1. As mentioned earlier, affect may be used as information when people attribute their feelings to the persuasive message (Petty et al., 1993). However, as shown in Figure 1, extraneous affect is unlikely to inform judgments unless people identify or direct attention to it before they make a judgment.1 In the context of our research, there are three conditions that may allow people to identify their feelings as a potential criterion. First, people who have both ability and motivation to think about their attitudes are likely to direct their attention to the affect they experience. Second, recipients who are distracted by environmental information may need considerable motivation to assess their affective states but may nevertheless do so successfully (for evidence on how motivation can compensate for inability, see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001). 2 Third, recipients who have ability may identify their affective reactions even in the absence of motivation, as their reactions are likely to capture attention (Adolphs & Damasio, 2001; Clore et al., 1994, 2001).

Figure 1.

Stages in the use of affect as information.

Whether recipients who identify their affective reactions as potential bases for judgment actually use these reactions as information may also depend on whether they discount these reactions as irrelevant (see Figure 1). For example, people’s attempts to determine the informational value of the affect they experience are likely to be more successful when these people have ability and motivation than when they do not. Consequently, they are likely to discount affect as a legitimate basis for their attitudes. However, when the same recipients have low motivation, they may perform this analysis less carefully and fail to determine the extraneous source of their feelings. Similarly, people who have motivation but lack ability may be interested in determining the informational value of their affective reactions but may nevertheless fail to discount their affect.3

Of course, processes like the ones in Figure 1 can model the formation of attitudes on other bases as well. For example, the arguments contained in a persuasive message can also generate affective or evaluative reactions that are considered as potential bases for attitudes. Unlike irrelevant affect, however, the arguments in the message are likely to be subjectively relevant criteria for most recipients who have ability and motivation to think about them (see, e.g., Petty & Cacioppo, 1986). Therefore, the more recipients identify or direct attention to the arguments in the persuasive message as potential criteria and the more they assess the relevance of these arguments, the higher the impact of these arguments should be. Correspondingly, reductions in ability and motivation that hinder identification of the arguments contained in the message and judgments that these arguments are relevant should monotonically decrease the impact of the message arguments. In contrast, the influence of ability and motivation on the use of other, less relevant information is likely to be curvilinear. We manipulated argument strength in our experiments to explore these patterns and to examine the influence of affect across different types of persuasive messages.

The Present Research

Participants in three experiments read a persuasive communication that either favored or opposed the institution of comprehensive exams at the university in the context of an upcoming university referendum. Messages were either strong or weak and were presented in conditions that either were distracting (low ability) or allowed participants to concentrate (high ability). Half of the messages described comprehensive exams as relevant to participants (high motivation), whereas the other half presented the issue as unlikely to have an impact on their life (low motivation).

Our prediction about the curvilinear influence of extraneous affect required us to induce recipients of a persuasive message to experience an affective state. We used an omnibus manipulation of affect that included recalling past memories and drinking beverages that elicited either positive or negative affect. The first two experiments examine the influence of affect as a function of ability and motivation (a) when participants received communications that presented attitude-consistent information about the benefits of instituting the new policy (Experiment 1) and also (b) when the message arguments were redundant with prior knowledge and thus unlikely to have an influence (Experiment 2). We specifically predicted that, regardless of the use of a pro- or a counterattitudinal advocacy, affect would bias attitudes when ability or motivation was low but not when they both were low or both were high.

In the first two experiments of the series (see also Albarracín, 2002; Albarracín & Wyer, 2001), after reading the message, participants reported both their perception that the policy would lead to the outcomes described in the message (i.e., outcome beliefs) and their evaluations of the desirability of these events (i.e., outcome evaluations). They also reported their beliefs and evaluations of outcomes that recipients of the messages were likely to generate spontaneously on the basis of prior knowledge and attitudes. Intentions and actual voting behavior in support of the policy were also measured in the first two experiments.

The influence of affect as information may be evident in cognitions about the outcomes of one’s behavior as well as attitudes, because people may assess their affective reactions to decide whether the outcomes described in the message are credible and desirable (for related claims on the influence of affect on the individual components that go into a global judgment, see Wyer et al., 1999). That is, people who experience positive affect may form stronger beliefs in positive behavioral outcomes and weaker beliefs in negative behavioral outcomes as well as more favorable evaluations of all the behavioral outcomes.4 Alternatively, people may use affect as a criterion for more global attitudes because attitudes are often an expression of people’s affective reactions toward the behavior or issue being considered. The inclusion of measures of cognitions about outcomes allows us to examine these possibilities. Regardless of whether the influence of affect on attitudes toward the message advocacy is direct or mediated by cognitions about behavioral outcomes, we expected affect as information to manifest when ability or motivation was low but not when both were high or both were low.5

In Experiment 3 we manipulated affect focus among unmotivated recipients of a persuasive message. We designed this manipulation to accelerate the processes in which participants spontaneously engage (for the same rationale, see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001). Thus, when ability is high and motivation is low, participants who are forced to think about their affective reactions may be able to discount these reactions because they are already able to identify these reactions. In contrast, when both ability and motivation are low, participants who are forced to process their affective reactions may be able to identify their mood but still may not be capable of discounting these reactions. To the extent that the affect-focus manipulation induces participants in high-ability–low-motivation conditions to discount affect just as participants spontaneously do in high-ability–high-motivation situations, the instructional set should decrease the use of affect as information in the former conditions. Correspondingly, the affect-focus manipulation may induce participants in low-ability–low-motivation situations to identify affect in the same way as participants spontaneously do in high-ability–low-motivation situations, although the manipulation may be insufficient to increase affect discounting. Consequently, the instructions to focus on affect may increase the use of affect as information when both ability and motivation are low.

Experiment 1

Method

Overview and Design

As in Albarracín and Wyer (2001), participants were told that the experiment concerned the way people give and receive information in natural settings, such as a coffee shop. On this pretense, depending on random assignment to positive- or negative-affect conditions, participants wrote a letter to a friend describing either a happy or a frustrating personal experience and were served either a pleasant- or an unpleasant-tasting drink. Then participants read a newsletter containing either strong or weak arguments in favor of instituting comprehensive exams at the university. We manipulated their ability and motivation to think carefully about the arguments, by varying the situational distraction that existed while they were reading it, as well as the personal relevance of the message. After reading the newsletter, participants indicated their intentions to vote in favor of advocating comprehensive exams in a forthcoming referendum, their attitudes toward voting in favor of the policy, and their beliefs and evaluations associated with the policy’s specific consequences. Finally, at the end of the experiment, participants took part in a straw vote to decide whether the examinations should be instituted.

Participants in the experiment were 48 male and 114 female introductory psychology students who participated for course credit. Between 8 and 14 persons were randomly assigned to each combination of induced affect (positive vs. negative), argument strength (strong vs. weak), ability (high vs. low), and motivation (high vs. low). Participants were run in groups of up to 8 participants.6

Procedure

Participants were assigned to separate cubicles to prevent communication. They were introduced to the study with instructions that it concerned the way people process information in natural settings (e.g., a restaurant or coffee shop). At this point, the tape was turned on and continued playing throughout the entire experiment. In high-ability conditions, this noise consisted of low-volume, content-free sounds that were recorded at a local coffee shop. These background sounds were presented in low-ability conditions as well. In the latter case, however, the background noise at the time participants read the message was accompanied by a high-volume conversation in which a male student approached a female student for the purpose of getting acquainted. The conversation touched on school issues, the personal history of the characters, and life in a small town. (The low-ability material was played during the time allocated for participants to read the message. In all other parts of the experiment, the background noise was the same as in high-ability conditions).

Induction of affect

As in Albarracín and Wyer’s (2001) research, participants’ affective state was manipulated by means of two procedures that had the same objectives. First, we adopted a procedure developed by Schwarz and Clore (1983). That is, participants were told to write a letter to a friend recalling a personal experience that had made them either extremely happy or extremely angry. (Anger was used instead of sadness because anger has been reported to produce processing effects similar to those for happiness; see Bodenhausen, 1993.) After writing the letter, participants were offered 3 oz of a soda with instructions to drink it all at once. In the positive affect condition, Coke was served. In the negative affect condition, tonic was served, which is bitter and had been rated as unpleasant during pretesting.7

Presentation of message

The persuasive message was presented in the form of a newsletter that had ostensibly been written in anticipation of a student referendum to decide whether comprehensive exams should be instituted for university undergraduates (see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001). The message was based on materials developed by Petty and Cacioppo (1986). It consisted of an introduction to the problem followed by either four strong arguments or four weak arguments in favor of such exams. The messages were about equal in length (mean words = 657), but each contained a different set of arguments. There were two newsletters containing strong arguments and two newsletters containing weak arguments. For example, one strong-argument newsletter asserted that if comprehensive exams were instituted, the starting salary of the graduates would increase and the reputation of the university and its alumni would be elevated. It further argued that senior final exams would be eliminated as a result of comprehensive exams and that faculty would teach more effectively. In contrast, one of the weak-argument newsletters stated that exams would lead to better student performance as a result of an increase in anxiety and would discriminate less against undergraduates given that graduate students were already able to take comprehensive exams.

We manipulated motivation by introducing differences in relevance in the presentation of the message. Participants in high-motivation conditions were told that that they would have to take the comprehensive examinations if the plan were adopted. Participants in low-motivation conditions were led to believe that the proposed plan would apply only to future students and therefore that they would personally not be affected by it.

Participants were then given the newsletter and told to read it as they would if they wanted to describe its contents to a friend and discuss its implications. These instructions served to make the experiment more meaningful. Furthermore, we indicated that if the background material seemed interesting, participants could pay attention to that material as well. To ensure that participants in low-ability conditions would not compensate by taking extra time, however, we requested that all participants read through the message only once. All participants were given a maximum of 10 min to read the newsletter and were supervised to make sure that they complied with the instructions. Most participants took 3 min to read the newsletter.

Dependent Measures

After reading the newsletter, participants completed a questionnaire that included measures of attitudes, beliefs, evaluations, and intentions (see Albarracín & Wyer, 2000, 2001).

Attitudes

We assessed attitudes (see Thurstone, 1959; Wyer & Srull, 1989) by asking participants to rate “voting in favor of comprehensive exams on the referendum” along scales from −5 to 5 (something I like vs. something I don’t like; pleasant vs. unpleasant; something that makes me feel bad vs. something that makes me feel good; something that makes me angry vs. something that doesn’t make me angry; something that makes me feel happy vs. something that makes me feel unhappy; something that ruins my mood vs. something that improves my mood). The reliability of the scale (as inferred from Cronbach’s alpha) was .95. Scale items were therefore averaged and used as a summary index of attitude.

Intentions

The measure of intentions included two items (i.e., “I will vote yes in the referendum” and “I intend to vote yes in the referendum”). Judgments of these items, which were reported along scales from −5 (not at all likely) to 5 (extremely likely), were correlated at .98. These judgments were therefore averaged to provide a single index of behavioral intentions.

Beliefs and evaluations of behavioral outcomes

We constructed statements about each of the 16 policy outcomes the message described (see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; see also Wegener, Petty, & Klein, 1994). Some statements referred to outcomes specified in arguments contained in the persuasive messages that we used. Eight items pertained to weak arguments (e.g., “Instituting comprehensive examinations will lead students’ parents to feel good because they are the ones who pay for the education”), and 8 pertained to strong arguments (e.g., “Instituting comprehensive exams will result in a salary increase for college graduates”). Of these, 4 pertained to the specific arguments contained in the newsletter that participants had read, whereas the remaining items concerned arguments contained in the newsletters participants did not read. In addition to statements about outcomes mentioned in the messages, we included statements about outcomes based on prior knowledge about the policy and exams in general (see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001). We elicited these outcomes based on prior knowledge from an independent group of nondistracted message recipients who were required to list the advantages and disadvantages of instituting comprehensive exams at their university. The seven most frequent outcomes participants mentioned, which were all negative, were included in the questionnaire. The 23 statements we created were distributed in the questionnaire in a manner to be described.

Participants reported their beliefs in each of the 23 outcomes along a scale from 0 (not at all likely) to 10 (extremely likely). In addition, they evaluated each outcome along a scale from −5 (dislike) to 5 (like). Each belief in the outcomes discussed in the message a given recipient read was multiplied by the evaluation corresponding to the same outcome, and these products were averaged to construct an index of cognitions about outcomes mentioned in the message (for the use of similar indices, see Albarracín & Wyer, 2000; Fishbein & Ajzen, 1975):

| (1) |

where A is the attitude toward the behavior, bi is the belief that outcome i will occur, and ei is the evaluation of that outcome. We used the same procedures to create an average measure of cognitions about outcomes suggested by prior knowledge, which included the outcomes that the independent group of participants generated in response to the messages used in the study. The internal consistency of the measures of cognitions about policy outcomes was satisfactory (Cronbach’s α = 92 and .74 for outcomes mentioned in the message and derived from prior knowledge, respectively).

Validity of indices of cognitions about outcomes

According to Fishbein and Ajzen (1975), participants’ attitudes toward the behavior being advocated should be predictable from Equation 1. It was unclear, however, whether participants, in computing their attitudes, would take into account the outcomes specified in the message they received, unmentioned consequences that they spontaneously recalled and thought about, or both. Predicted attitudes based on Equation 1 were computed under low-distraction conditions on the basis of (a) participants’ estimates of the likelihood and desirability of the four outcomes specified in the message they read (i.e., message-based outcomes) and (b) their judgments of the seven outcomes that pretest participants had generated spontaneously on the basis of their prior knowledge (i.e., knowledge-based outcomes). The attitudes participants actually reported were correlated at .35 (n = 40, p = .01) with predicted values based on cognitions about message-based outcomes but only .02 (ns) with predicted values based on cognitions about knowledge-generated outcomes. These differences must be evaluated in relation to analogous data from an independent group of participants who have not read the persuasive message. To permit these comparisons, we asked 21 participants who had not been exposed to the message or to any other experimental manipulations to complete the same dependent variable questionnaire that experimental participants were administered. Attitudes reported by these participants were correlated only .18 (ns) with predicted values based on beliefs and evaluations of the consequences discussed in the messages we presented, but they were correlated .47 (p < .05) with predicted values based on cognitions about consequences that were likely to come to mind spontaneously. Thus, relative to message recipients, participants who had not read a persuasive message based their attitudes primarily on beliefs and evaluations concerning outcomes that came to mind spontaneously when they thought about comprehensive examinations. In sum, these findings suggest that our measures (see also Ajzen & Fishbein, 1980; Ajzen & Madden, 1986; Albarracín & Wyer, 2000, 2001) reflect processing of the persuasive message.8

Order of presentation

To control for the order of presentation of our measures, we constructed four versions of the questionnaire. In each case, intentions were assessed first to minimize the possibility that they would be artifactually influenced by participants’ reports of the cognitions that theoretically mediate intentions. However, the questionnaires differed in the order in which attitudes, outcome beliefs, and outcome evaluations were reported (specifically, attitude–evaluations–beliefs, attitudes–beliefs –evaluations, beliefs–evaluations–attitudes, and evaluations–beliefs–attitudes). Questionnaire versions were administered a similar proportion of times in each experimental condition. Finally, outcome belief and evaluation items were interspersed in each questionnaire so that the mean serial position of items that concerned (a) the 4 outcomes mentioned in the message participants received, (b) the 12 outcomes mentioned in the messages that participants did not read, and (c) the 7 negative outcomes suggested by prior knowledge was about the same.

Manipulation Checks

After reporting their beliefs and attitudes, participants reported their reactions to various aspects of the experimental procedures. These reactions included (a) the extent to which they felt happy at the time they drank the soda and wrote the letter to a friend and the extent to which they felt angry at those times, (b) the extent to which they could concentrate while reading the message, (c) the extent to which the message was relevant to them personally, and (d) the extent to which the message was convincing. Responses to all items were made along a scale from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely).

Behavior

To obtain an indication of whether participants would actually perform the behavior advocated in the message they had read, we added a final page to the questionnaire. On this page, we indicated that the fact that participants had read a newsletter about comprehensive exams gave us the opportunity to see how informed students might vote on the referendum. The instructions went on to indicate that to ensure fair voting, the experimenter had signed the ballots and stapled them to the last page of the questionnaire. Participants were asked to select the slip that represented their choice and to place it in a ballot box that was in the room. Thus, their votes were ostensibly anonymous. Nevertheless, we were able to infer each participant’s vote on the basis of the slip that was left in the questionnaire. A favorable vote was scored as 1, and an unfavorable vote was scored as 0.

Results

Manipulation Checks

Our experimental manipulations of affect, ability, motivation, and argument strength were successful. Participants reported greater happiness while writing about a happy experience than while writing about a frustrating one (Ms = 6.7 vs. 3.9), F(1, 143) = 78.03, p < .001, and reported more anger in the latter conditions than in the former (Ms = 5.3 vs. 1.9), F(1, 143) = 77.57, p < .001. Correspondingly, they reported feeling happier while drinking a pleasant-tasting soda than while drinking the unpleasant drink (Ms = 5.8 vs. 2.2), F(1, 143) = 80.85, p < .001, and angrier in the latter conditions than in the former (Ms = 5.3 vs. 1.9), F(1, 143) = 38.71, p < .001.9

Participants also reported being less able to concentrate while reading the passage under low-ability than under high-ability conditions (Ms = 4.0 vs. 7.0), F(1, 143) = 77.49, p < .001. They also rated the newsletter they read as more personally relevant when it concerned examinations they would have to take themselves than when it concerned examinations they would not have to take (Ms = 6.4 vs. 3.3), F(1, 143) = 39.85, p < .01. Moreover, although the ability manipulation had an influence regardless of the relevance of the persuasive message, the influence of ability on reported concentration was greater when relevance was high than when it was low (Mdiff = 3.4 vs. 2.0). The interaction between ability and motivation on perceived concentration was statistically significant, F(1, 143) = 3.85, p < .05.

Finally, participants rated the communication as more convincing when it contained strong arguments than when it contained weak arguments (Ms = 5.4 vs. 4.2), F(1, 143) = 11.05, p < .001. Perceptions of argument strength did not significantly depend on either participants’ ability or their motivation (F < 1.00).

Test of Hypotheses

We used mean analyses of variance to examine the influence of extraneous affect, ability, motivation, and argument strength on attitudes, intentions, and behaviors as well as cognitions about the outcomes of the policy. Because the four-way interaction was not significant for any measure (F < 1.00), we describe the influence of affect and argument strength separately in Table 1.10

Table 1. Influence of Affect and Argument Strength as a Function of Ability and Motivation: Experiment 1.

| Effect of affect

|

Effect of argument strength

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Positive affect | Negative affect | Difference | Strong arguments | Weak arguments | Difference |

| Attitudes toward voting in favor of the advocacy (−5 to 5) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | −0.9 | 0.3 | −1.2* | 0.3 | −1.0 | 1.3* |

| Low motivation | −0.8 | −2.0 | 1.2* | −0.8 | −2.2 | 1.4* |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | −0.3 | −1.6 | 1.3* | −0.3 | −1.5 | 1.2* |

| Low motivation | −0.4 | 0.3 | −0.7 | 0.1 | −0.3 | 0.4 |

|

| ||||||

| Intentions to vote in favor of the advocacy (−5 to 5) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | −0.9 | −0.2 | −0.7 | 0.8 | −1.9 | 2.7* |

| Low motivation | −0.4 | −2.2 | 1.8* | 0.2 | −2.3 | 2.5* |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | −0.9 | −1.4 | 0.5 | 0.4 | −2.6 | 3.0* |

| Low motivation | 0.2 | −0.2 | 0.4 | 0.5 | −0.6 | 1.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Actual behavior in favor of the advocacya (0 vs. 1) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 0.3 | 0.5 | −0.2 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.5* |

| Low motivation | 0.5 | 0.2 | 0.3* | 0.4 | 0.2 | 0.2* |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 0.4 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.1 | 0.5* |

| Low motivation | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.0 | 0.6 | 0.3 | 0.3* |

|

| ||||||

| Cognitions about the outcomes of the advocacy suggested in the message (−25 to 25) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 7.9 | 8.8 | −0.9 | 18.5 | −1.8 | 20.3* |

| Low motivation | 6.3 | 4.2 | 2.1 | 11.4 | −0.9 | 12.3* |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 10.0 | 6.5 | 3.5 | 17.3 | −0.8 | 18.1* |

| Low motivation | 8.8 | 7.9 | 0.9 | 14.6 | 2.1 | 12.5* |

|

| ||||||

| Cognitions about the outcomes of the advocacy suggested by prior knowledge (−25 to 25) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | −19.6 | −9.7 | −9.9* | −14.9 | −14.3 | −0.6 |

| Low motivation | −13.4 | −15.4 | 2.0 | −8.4 | −20.9 | 12.5* |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | −14.2 | −14.1 | −0.1 | −12.1 | −16.2 | 4.1 |

| Low motivation | −16.0 | −15.5 | −0.5 | −15.0 | −17.0 | 2.0 |

Note. We computed difference scores to represent the influence of affect by subtracting the mean of a given variable when affect was negative from the mean of the same variable when affect was positive. We computed difference scores to represent the influence of argument strength by subtracting the mean of a given variable when arguments were weak from the mean of the same variable when arguments were strong. a Behavior is expressed as the proportion of participants who voted in favor of the policy.

p < .05.

Influence of affect

The data presented in Table 1 provide strong support for the hypothesis that affect informs attitudes in the curvilinear pattern we predicted. That is, affect had a positive influence on attitudes in conditions in which only ability or only motivation was low but not when both factors were low. However, the influence of affect was significantly negative when ability and motivation were both high (for similar reports, see Isbell & Wyer, 1999) and was nonsignificant when they were both low. The interaction among affect, ability, and motivation that bears on this contingency was statistically significant for attitudes, F(1, 144) = 12.45, p < .001,11 and the pattern for intentions and behaviors was similar, F(1, 144) = 2.58 and 3.99, ns and p < .05, respectively.

An important question was whether the influence of affect on attitudes was mediated by cognitions about policy outcomes. Consider the effects of affect on the composite indices of outcome beliefs and evaluations that appear on the bottom section of Table 1. The index based on the message content is generally positive because it indicates agreement with the message, whereas the index based on prior knowledge is generally negative because it comprises counterarguments. The findings in Table 1 indicate that affect had no significant influence on cognitions about policy outcomes suggested by the message regardless of level of ability and motivation. Moreover, in high-ability–high-motivation conditions, the index of outcome beliefs and evaluations based on prior knowledge was significantly more negative when participants experienced positive affect than when they experienced negative affect (see Table 1). As judged by the interaction among affect, ability, and motivation, this negative influence of affect on cognitions about outcomes suggested by prior knowledge did not differ significantly from the influence of affect in the other conditions, F(1, 144) = 1.55, ns.

Briefly, the data in Table 1 provide strong support for the possibility that recipients of a persuasive message use affect as a basis for attitudes. That is, participants in the experiment formed attitudes on the basis of extraneous affect in conditions that permitted moderate amounts of thought but not when both ability and motivation were low or high. These informational effects of affect, however, did not appear to be mediated by participants’ thoughts about the outcomes of the policy.

Influence of argument strength

The data in the right panel of Table 1 clearly convey that recipients processed the content of the message and that this content had an impact on the beliefs and evaluations of the outcomes the message discussed. As can be seen from Table 1, the index of cognitions about outcomes described in the message was more favorable when participants received strong arguments than when they received weak arguments (Ms = 15.6 vs. −0.4), F(1, 144) = 93.17, p < .01. Similarly, the index based on outcomes suggested by prior knowledge was less negative when participants received strong arguments than when they received weak arguments (Ms = −12.7 vs. −17.3), F(1, 144) = 3.5, p < .06.12 Moreover, the influence of argument strength on the message-based index was stronger when motivation was high thanwhen it was low (Mdiff = 19.2 vs. 12.0), which was confirmed by a significant interaction between argument strength and motivation, F(1, 144) = 4.41, p < .04. The interaction between argument strength and motivation, however, was not significant for the index based on prior knowledge (Mdiff = 1.8 vs. 1.3), F(1, 144) = 1.72, ns, and neither index was contingent on the higher order interaction among argument strength, ability, and motivation (F < 1.00 in each case).

The data in Table 1 also suggest that participants used the information contained in the message arguments as a basis for attitudes and intentions and that the vote they cast followed the message’s recommendation to a greater extent when the message was strong than when it was weak. That is, participants who read strong messages generally manifested attitudes, intentions, and voting behavior that were more consistent with the message advocacy than those of participants who read weak messages (Ms = 1.1, 2.3, and 0.4, respectively), F(1, 144) = 11.28, p < .001, in each case.

Although the influence of argument strength on attitudes and intentions did not interact significantly with either ability or motivation, F(1, 144) < 1.68, ns, in each case, an examination of the means indicated that the impact of argument strength on attitudes and intentions was not significant when both ability and motivation were low (Mdiff = 0.4 and 1.1, respectively). Because this pattern was not at all apparent for cognitions about behavioral outcomes, it suggests that participants did not integrate these cognitions into their attitudes in conditions in which both ability and motivation were low (for identical findings on the disruption of attitude by distraction, see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001).

Discussion

The results of Experiment 1 are consistent with the hypothesis that recipients of persuasive messages use extraneous affect as a basis for attitudes. As suggested by the analysis of variance, extraneous affect informed attitudes in conditions in which only ability or motivation was low and presumably stimulated only moderate amounts of thought. However, it had no influence when participants’ ability and motivation were both low.13

We conducted Experiment 2 to confirm some of the conclusions from Experiment 1. That is, the earlier results are consistent with the possibility that people who receive a counterattitudinal message rely on their subjective feelings as a basis for attitudes. One could argue, however, that this process may only occur because counterattitudinal messages can stimulate greater amounts of processing than can proattitudinal communications (see Eagly, Kulesa, Brannon, Shaw, & Huston-Comeaux, 2000). Unlike participants in Experiment 1, participants in Experiment 2 were exposed to a message that opposed the institution of comprehensive exams rather than favoring it. The arguments presented were based on typical recipients’ expectations about the negative outcomes of comprehensive exams and were therefore unlikely to result in a revision of participants’ attitudes. Thus, Experiment 2 provides evidence concerning the robustness of the affect-as-information hypothesis (see Figure 1) and its generalizability to the processing of proattitudinal communications.

Experiment 2

Method

As in Experiment 1, the design was a 2 (argument strength: high vs. low) × 2 (affect: positive vs. negative) × 2 (ability: high vs. low) × 2 (motivation: high vs. low) factorial. A total of 164 participants (36 men and 128 women) were randomly assigned to each of the 16 conditions in the study. Between 8 and 12 participants were run in each cell.

Message Content

We used two versions of messages (i.e., one weak and one strong) that contained arguments against the institution of comprehensive exams organized in the form of a newsletter. We constructed the arguments to represent beliefs in the outcomes that participants were likely to generate spontaneously, as suggested by the elicitation study described before. We wrote both weak and strong arguments in a style that closely resembled that of Petty and Cacioppo’s (1986) arguments in favor of comprehensive exams. For example, one of the strong arguments we used described how prestigious graduate schools place little emphasis on the exams because they do not reflect true potential for achievement among students. One of the weak newsletters stated that members of a fraternity believed that comprehensive exams prevented students from learning about real life. The selection of these arguments was based on a larger pool of 14 arguments that people rated as either persuasive, strong, likely to be true, and logically valid or not persuasive, weak, unlikely to be true, and logically invalid.

Dependent Measures

As in Experiment 1, we measured outcome beliefs and evaluations, attitudes, intentions, and behavior. The measures of attitudes, intentions, and behavior were identical to the ones used in Experiment 1. We reverse scored them to reflect agreement with the message advocacy. The measures of beliefs and evaluations included four negative outcomes summarizing

The questionnaires used in this study included 16 orders, in which outcome beliefs, outcome evaluations, attitudes, and intentions each appeared first, second, third, and last an equal number of times. (As before, order had no significant influence on the cognitions and behavior that participants manifested.)

Results

Manipulation Checks

Recipients of strong arguments perceived the message as more convincing than did recipients of weak messages (Ms = 5.5 vs. 4.5), F(1, 141) = 8.73, p < .01. Thus, recipients of messages that were redundant with their prior knowledge can nevertheless distinguish arguments that are strong from those that are weak.

As in the earlier study, participants who wrote a letter about a happy event and drank the pleasant drink reported feeling happier (Ms = 7.3 and 6.2 at the time of the letter and the drink) and less angry (Ms = 1.2 and 1.8 at each time) than did participants who wrote a letter about a frustrating event and drank the unpleasant drink (Ms = 3.8 and 2.3 for happiness at each time, and 4.2 and 5.0 for anger at each time), F(1, 141) = 34.72, p < .01, in all cases.

The manipulations of motivation and ability also had the desired effects. That is, participants who were told that they would have to take the exams if the policy was instituted perceived the message as more relevant than did participants who were told they would not have to take the exams (Ms = 6.9 vs. 3.3), F(1, 141) = 62.67, p < .01. Similarly, participants in high-ability conditions reported being more able to concentrate than did participants in low-ability conditions (Ms = 6.5 vs. 3.7), F(1, 141) = 69.49, p < .01. As before, participants in high-ability conditions reported that the newsletter was more relevant relative to participants in low-ability conditions (Ms = 5.8 vs. 4.5), F(1, 141) = 8.17, p < .01. No other effects reached significance.

Test of Hypotheses

As in Experiment 1, we conducted analyses of variance of cognitions about policy outcomes, attitudes, intentions, and behavior as a function of affect, ability, motivation, and argument strength. The data pertaining to these analyses appear in Table 2.

Table 2.

Influence of Affect and Argument Strength as a Function of Ability and Motivation: Experiment 2

| Effect of affect

|

Effect of argument strength

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Positive affect | Negative affect | Difference | Strong arguments | Weak arguments | Difference |

| Attitudes toward voting in favor of the advocacy (−5 to 5) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 2.5 | 2.9 | −0.4 | 2.9 | 2.6 | 0.3 |

| Low motivation | 2.4 | 1.3 | 1.1* | 2.1 | 1.6 | 0.5 |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 2.4 | 1.6 | 0.8* | 2.0 | 2.0 | 0.0 |

| Low motivation | 2.1 | 2.4 | −0.3 | 2.3 | 2.2 | 0.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Intentions to vote in favor of the advocacy (−5 to 5) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 4.3 | 3.5 | 0.8* | 4.0 | 3.8 | 0.2 |

| Low motivation | 4.4 | 3.0 | 1.4* | 3.9 | 3.0 | 0.9 |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 3.8 | 2.5 | 1.3* | 3.1 | 3.2 | −0.1 |

| Low motivation | 3.4 | 3.7 | −0.3 | 3.4 | 3.7 | −0.3 |

|

| ||||||

| Actual behavior in favor of the advocacya (0 vs. 1) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.1 | 0.9 | 1.0 | −0.1 |

| Low motivation | 1.0 | 0.8 | 0.2* | 0.9 | 0.9 | 0.0 |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 0.9 | 0.7 | 0.2* | 0.8 | 0.8 | 0.0 |

| Low motivation | 0.9 | 1.0 | −0.1 | 1.0 | 0.9 | 0.1 |

|

| ||||||

| Cognitions about the outcomes of the advocacy (−25 to 25) | ||||||

| High ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 17.2 | 4.4 | 12.8* | 14.0 | 7.6 | 6.4* |

| Low motivation | 6.9 | 5.6 | 1.3 | 8.7 | 3.9 | 4.8* |

| Low ability | ||||||

| High motivation | 9.2 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 8.3 | 9.4 | −1.1 |

| Low motivation | 7.6 | 9.8 | −2.2 | 3.2 | 10.2 | −7.0 |

Behavior is expressed as the proportion of participants who voted against the policy.

p < .05.

Influence of affect

Once again, we found support for the prediction that affect influences attitudes when only ability or motivation is low but not when both are high or both are low. The relevant data appear on the left half of Table 2. As in Experiment 1, the affect participants experienced influenced the attitudes they formed when only ability or motivation was low but not otherwise. This pattern was supported by a marginal interaction among affect, ability, and motivation, F(1, 145) = 3.48, p < .06.14 As shown in Table 2, participants who had only high ability or only high motivation formed attitudes more in line with the message when they were in a positive mood than when they were in a negative mood. However, when ability and motivation were both high or both low, affect had no influence on attitudes. The interaction among affect, ability, and motivation was evident in intentions and behaviors as well, F(1, 145) = 2.40 and 5.29, ns and p < .02, in each case, and was confirmed by a significant overall interaction for the three variables considered simultaneously ( p < .01).

As in Experiment 1, we were able to examine whether affect biased cognitions about the policy outcomes. These data appear in the last section of Table 2. In conditions of high ability and high motivation, these cognitions were more consistent in direction with the message advocacy when participants experienced positive affect than when they experienced negative affect. Although the interaction among affect, ability, and motivation was not significant (F < 1.00), the consistency of this finding with Petty et al.’s (1993) reports suggests that in these conditions, affect influenced encoding or recall of material related to the message.

Influence of argument strength

The messages we used in this experiment contained arguments that participants could retrieve spontaneously in thinking about comprehensive exams and were therefore not expected to produce attitude change. The data in Table 2 are consistent with this possibility. When ability was high, recipients of strong arguments reported cognitions about the behavior outcomes that were more in line with the message than those of participants who received weak arguments (Ms = 11.4 vs. 5.8). Although the overall effect of argument strength on these cognitions was not significant (F < 1.00), the interaction between argument strength and ability was reliable, F(1, 145) = 6.54, p < .01. However, the strength of the arguments presented in the communication had no effect at all on attitudes, intentions, or actual behavior, F(1, 145) < 1.09, in each case (see Table 2). The interaction among argument strength, ability, and motivation was not significant for any of the dependent measures (F < 1.00). Given these data, we concluded that affect had an influence when participants processed proattitudinal arguments as well as counterattitudinal messages.

Discussion

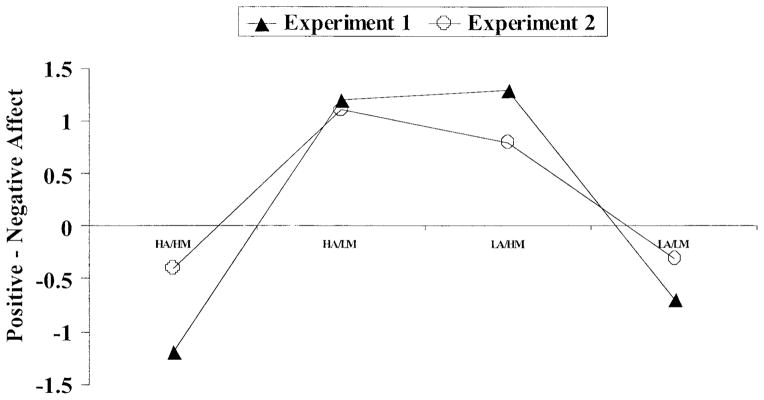

Experiments 1 and 2 examine the influence of affect on attitudes and allow us to reach some conclusions about the role of extraneous affect as information. A summary of the effects of affect on attitudes in the two studies appears in Figure 2. As can be seen from the figure, the influence of irrelevant affect on attitudes was remarkably similar in the two studies and was in line with our predictions. First, when only ability or motivation was low, participants used affect to assess their agreement with the policy advocated in the persuasive message. We can presume that participants in these conditions considered the affect they experienced but were nevertheless unable or unmotivated to discount their affective reactions as a legitimate basis for judgment (see Figure 1). Second, when ability and motivation were both high, affect had either a negative influence or no influence at all. These findings are consistent with the possibility that participants identified their affective reactions but later determined that the informational value of these reactions was low and discounted them at the time of judgment. Finally, when ability and motivation were both low, affect had no influence whatsoever. This finding is consistent with the hypothesis that, in these situations, participants did not identify their affective reactions as a criterion for judgment, and, consequently, affect had no influence. Experiment 3 validates these assumptions.

Figure 2.

Summary of findings from Experiments 1 and 2. Values represent the impact of affect, which we computed by subtracting the mean of attitudes when affect was negative from the mean of attitudes when affect was positive. HA = high ability; HM = high motivation; LM = low motivation; LA = low ability.

Experiment 3

To provide further support for our model of affect identification and discounting, we induced a mood in an independent group of participants and then presented them with the persuasive messages used in Experiment 1. In this experiment, we kept motivation constant at the low level used in the earlier experiments and manipulated ability over two levels (high vs. low). According to our model, participants in low-motivation–high-ability conditions should identify but not discount their affective reactions, which should result in evidence of affective bias in those conditions. In contrast, participants in conditions of low ability and motivation should be unable to identify the affect they experience when they read the communication, and this inability should result in a lack of impact of affect.

The critical change in this experiment, however, was to introduce instructions to manipulate the amount of affect-relevant thought participants engage in at the time of the reception of the message. We examined past research on affect as information to decide what procedures would work best. For example, Schwarz and Clore (1983) induced discounting of weather-related mood by means of two manipulations. They asked one group to report how the weather was at that time, and this manipulation removed the effects of weather on judgments of life satisfaction. Similarly, they told another group of participants that the weather could influence their life satisfaction, an explanation that also removed the influence of the weather on judgments. Similarly, Gasper and Clore (1998) asked participants to report their mood prior to reporting risk estimates, and this procedure reversed the influence of mood on judgments because participants presumably discounted the influence of this mood. In sum, both increasing attention to the irrelevant source of one’s affective reactions and inducing participants to identify mood appear to trigger discounting of that mood when participants have the ability and motivation to discount that mood.15

In our experiment, we told some participants to read the message while trying to become sensitive to the affect and emotions they experienced at the time and to attempt to separate their mood from their reactions to the persuasive communication. We designed this manipulation to accelerate the processes in which participants spontaneously engage (for the same rationale, see Albarracín & Wyer, 2001). Presumably, when ability is high and motivation is low, participants who are forced to think about their affect may be able to discount their affective reactions because they are already able to identify affect. In contrast, when both ability and motivation are low, participants who are forced to focus on their affective reactions may be able to identify their mood but may still not be capable of discounting these reactions. To the extent that the affect-focus manipulation induces participants in high-ability–low-motivation conditions to process information like participants did in the high-ability–high-motivation situations of the earlier experiments, the instructional set should decrease the use of affect as information in these conditions. Conversely, the affect-focus manipulation may induce participants in low-ability–low-motivation situations to process information in the same way as did participants in the high-ability–low-motivation conditions of the earlier studies. Consequently, the instructions to focus on affect should increase the use of affect as information when both ability and motivation are low. We examined these possibilities by comparing the impact of the affect induction on the attitudes of unmotivated participants as a function of instructional set (affect focus vs. control) and ability (low vs. high).

It is important to note that, in designing this experiment, we excluded detailed consideration of the processes that take place when people receive a persuasive communication in conditions of high ability and motivation. There are two reasons for this decision. First, we thought that the current design would illuminate the processes that take place in high-ability–high-motivation conditions, because the affect-focus manipulation should induce participants in high-ability–low-motivation conditions to act like our earlier participants in low-ability–low-motivation situations. Second, the processes that take place when people discount affect have been examined by Isbell and Wyer (1999). Other literatures also speak to the processes that take place when people discount affect, including research by Ottati and Isbell (1996) as well as Wegener and Petty (1995). We therefore decided to concentrate on conditions of moderate and low amount of thought, which are key to our nonmonotonic predictions.

Method

Participants

The design was a 2 (affect: positive vs. negative) × 2 (argument strength: strong vs. weak) × 2 (instructional set: affect focus vs. control) × 2 (ability: low vs. high) factorial. Participants in this experiment were 140 introductory psychology and marketing students (71% women) randomly distributed across conditions. Between 7 and 12 participants were assigned to each group.

Procedures

The procedures to manipulate affect were identical to the ones used in the earlier experiments. In addition, like in Experiment 1, after the mood induction, participants were given up to 10 min to read strong or weak messages advocating the institution of comprehensive exams and then reported their attitudes toward voting in favor of the policy using the same measures from the earlier studies.

To manipulate affect focus, we instructed half of the participants to read the message while trying to become sensitive to their emotional feelings and to separate their feelings about the message from their mood for other reasons, using only their reactions to the message as a basis for judging the validity of the message. The other half of the participants read the communication without any instruction.

Dependent Measures

After reading the persuasive communication, all participants reported their attitudes concerning the policy using the procedures described before. In addition, participants judged the extent to which they had performed two cognitive strategies using items modified from scales developed by Swinkels and Giuliano (1995). To measure identification of affect as a potential source of information in the context of the attitude judgment, we asked participants whether, while reading the newsletter, they (a) were sensitive to changes in their mood, (b) did not pay much attention to their mood (reversed scored), and (c) tuned in to their emotions. To determine whether participants discounted affect, we asked them whether, while reading the newsletter, they (a) kept thinking that their mood should not matter, (b) tried to determine whether they were happy or upset because of the newsletter or because of the episode they wrote about, (c) tried very hard not to be influenced by their mood, and (d) thought that their mood should not be a factor in deciding whether they agreed with the message. Participants responded to each of these questions on scales from 0 (not at all) to 10 (extremely) or from 0 (false) to 1 (true). We standardized and averaged the questions assessing affect identification and discounting to create composite indices (αs = .84 and .64).

Results and Discussion

Manipulation Checks

Manipulations of affect, ability, and argument strength

As in the earlier experiments, our experimental manipulations of affect, ability, and argument strength were successful. Thus, participants reported greater happiness while writing about a happy experience than while writing about a frustrating one (Ms = 6.5 vs. 3.0), F(1, 139) = 63.07, p < .001, and reported more anger in the latter conditions than in the former (Ms = 5.0 vs. 1.1), F(1, 139) = 56.33, p < .001. They also reported feeling happier while drinking a pleasant-tasting soda than while drinking the unpleasant drink (Ms = 5.6 vs. 2.2), F(1, 139) = 57.29, p < .001, and angrier in the latter conditions than in the former (Ms = 3.3 vs. 1.1), F(1, 139) = 26.60, p < .001. The affect participants experienced did not depend on distraction, argument strength, or affect focus (F < 1.00 in all cases).

Participants also reported being less able to concentrate while reading the passage under low-ability conditions than under high-ability conditions (Ms = 3.8 vs. 6.5), F(1, 139) = 39.94, p < .001, and rated the communication as more convincing when it contained strong arguments than when it contained weak arguments (Ms = 5.4 vs. 3.9), F(1, 139) = 14.53, p < .001. No higher order interactions were significant.

Manipulation of affect focus

According to manipulation checks, our manipulation of affect focus was successful. Overall, participants in control conditions reported less identification than did participants in affect-focus conditions (Ms = 0.2 vs. −0.2), F(1, 139) = 8.11, p < .001. Furthermore, participants in control conditions reported less discounting than did participants in affect-focus conditions (Ms = 0.1 vs. −0.1), F(1, 139) = 6.19, p < .001. Important higher order interactions in line with predictions are discussed presently in the context of analyses of pairwise differences.

Test of Theoretical Hypotheses

We analyzed attitudes as a function of affect, argument strength, instructional set, and ability. As before, the four-way interaction was not significant (F < 1.00), which justified consideration of the impact of affect independently of that of argument strength. In addition, we examined reports of identification and discounting with planned comparisons and included these reports as covariates in supplementary analyses of the influence of affect and instructional set on attitudes.

Influence of affect

The influence of affect on attitudes appears in Table 3. In line with our hypotheses, participants in control conditions formed attitudes on the basis of the affect they experienced only when ability was high and motivation was low but not when both were low. Thus, we replicated the pattern observed in Experiments 1 and 2. In contrast, when participants were instructed to focus on their affective reactions, they used affect as a basis of attitudes only when ability and motivation were both low but not when ability was high and motivation was low. The three-way interaction involving affect, instructional set, and ability was significant, F(1, 139) = 4.68, p < .03. This pattern is consistent with the prediction that forcing participants in conditions of high ability and low motivation to focus on affect led them to discount affect, decreasing the influence of this affect. In contrast, forcing participants in conditions of low ability and motivation to focus on affect allowed them to identify affect but was insufficient to induce affect discounting. Consequently, the instructions to focus on affect increased the use of affect as information when both ability and motivation were low.

Table 3.

Effects of Ability and Motivation on the Influence of Affect on Attitudes: Experiment 3 (Low Motivation)

| Effect of affect

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | Positive affect | Negative affect | Difference |

| High ability | |||

| Control | 0.6 | −0.7 | 1.3* |

| Affect focus | −0.7 | 0.3 | −1.0 |

| Low ability | |||

| Control | −0.1 | 0.1 | −0.2 |

| Affect focus | 0.3 | −1.2 | 1.5* |

Note. Differences represent the influence of affect on attitudes, which we represent by subtracting mean attitudes when affect was negative from mean attitudes when affect was positive.

p < .05.

Influence of argument strength

We also considered the influence of argument strength on participants’ attitudes. As in Experiment 1, participants who received strong arguments had more favorable attitudes toward the policy than did participants who received weak arguments (Mdiff = 0.7 vs. −1.1), F(1, 139) = 15.31, p < .001. The impact of affect was nonsignificant when ability was low and participants were in control conditions (Mdiff = 0.9) and significant in all other conditions (Mdiff = 2.2). However, the interaction among argument strength, ability, and instructional set was not significant, F(1, 139) < 1.00.

Influence of instructional set and ability on reported identification and discounting

Planned comparisons showed that the cognitive activities that participants reported were contingent on the level of ability and motivation they experienced as well as the instructions they received. These contrasts are summarized in Table 4 and were consistent with the predictions from the model in Figure 1. Participants who were instructed to focus on their affective reactions and had high ability reported greater discounting and similar identification relative to high-ability participants in control conditions. Furthermore, participants in low-ability conditions who focused on their affect reported greater amounts of identification than did their control counterparts. This latter finding implies that the affect-focus instructions allowed participants with low ability to process affect further than did participants in control conditions. However, low-ability participants reported similar levels of discounting regardless of the instructions they received, which suggests that focusing on affect did not completely compensate for the low ability and motivation these participants had.

Table 4.

Effects of Ability and Instructional Set on Reported Identification and Discounting: Experiment 3 (Low Motivation)

| Condition | High ability | Low ability |

|---|---|---|

| Identification | ||

| Control | −0.03a | −0.30b |

| Affect focus | 0.12a | 0.31c |

| Discounting | ||

| Control | −0.01a | −0.20b |

| Affect focus | 0.33c | −0.05b |

Note. For each variable, different subscripts indicate statistically significant differences.

General Discussion

As has other research in the area of persuasion (Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; Petty et al., 1993), this work demonstrates that extraneous affect can influence people’s attitudes about the issues the message advocates. That is, people develop attitudes in line with the message to a greater extent when they experience positive affect than when they experience negative affect. Specifically, participants who read a message that favored comprehensive exams formed more favorable attitudes toward the policy when they were in a positive mood than when they were in a negative mood. In contrast, people who read a message opposing the policy had more unfavorable attitudes about the policy when they experienced positive affect than when they experienced negative affect.

Although the agreement effect of affect has been reported previously (see, e.g., Razran, 1940), the work we present advances our understanding of the mechanisms that underlie the influence of affect in persuasion. The data from all three experiments were used to validate our assumption that people who receive a persuasive message must first become sensitive to the affect they experience at the time they form an attitude. If message recipients do not identify extraneous affect or identify it but discount it, affect has no influence on their attitudes. If they do identify extraneous affect as a potential criterion but fail to discount this affect as irrelevant to the judgment they are about to make, this affect is likely to inform attitudes toward the message recommendation. The mechanisms of identification and discounting predict a curvilinear impact of amount of thought that is not implied in traditional assumptions about persuasion or affect as information.

Experiments 1 and 2 provide support for the stage model we proposed. They show that recipients of the persuasive message aligned their attitudes with their affective reactions independently of the direction of the advocacy (see Figure 2). These experiments also provide evidence that the influence of affect on attitudes was not mediated by corresponding influences on participants’ cognitions about the policy outcomes. The absence of effects of affect on cognitions about the policy outcomes when either ability or motivation was low is important because it suggests that the effects of affect as information are not localized at the level of judging the likelihood and desirability of events that were just encoded. Instead, message recipients in our experiments used affect as a basis for more global attitudes about the policy they were considering (see also Albarracín & Wyer, 2001).

It is important to consider one alternative interpretation of our findings. Specifically, readers may wonder whether participants in conditions of high ability and motivation may have concentrated on the message intensely, thus not identifying affect as a potential criterion. This alternative interpretation is plausible. However, the data from Experiment 3 suggest that the processes we proposed mediate the use of affect as information, thus rendering support for our interpretation of the findings under high-amount-of-thought conditions. In addition, past research by Isbell and Wyer (1999) found support that people who have high motivation to think about a political candidate apply naive theories of mood influences on judgments and consequently correct for the influence of affect. Although this evidence is not conclusive, it implies that lack of affect identification is unlikely to explain the influence of mood in high-amount-of-thought conditions.

Prior Work on Affect as Information

The data presented in our article suggest that people’s ability and motivation at the time they receive a persuasive message have a curvilinear impact on the influence of irrelevant affect. An analysis of findings reported by Albarracín (1997) and Albarracín and Wyer (2001) leads to the same conclusion. A description of the conditions and results of interest appears in Table 5. In these two reports, the researchers induced a positive or negative mood among participants and then presented strong or weak messages advocating the institution of comprehensive examinations under conditions of high or low ability (i.e., low and high distraction). However, the motivation participants had when they read the messages varied across the experiments in the two series. In Experiment 1 of Albarracín’s (1997) work, motivation was confounded with ability. That is, participants in high-ability conditions were told that they would have to take the exams if instituted (high motivation), whereas participants in conditions of low ability were told that they would not have to take the exams if instituted (low motivation). In contrast, in Albarracín and Wyer’s series of experiments, all participants were told that they would have to vote in a referendum to decide on the institution of comprehensive exams, although they would not have to take the exams if the policy were instituted (moderate motivation). Because of the different levels of motivation across the three experiments, these data offer evidence about the influence of affect over various levels of amount of thought.

Table 5.

Effects of Affect on Attitudes: Albarracín (1997) and Albarracín and Wyer (2001)

| Distribution of conditions along amount of thought continuum

|

Effect of affect

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Condition | High | Moderate | Low | High thought | Moderate thought | Low thought |

| Albarracín’s (1997) Experiment 1 | ||||||

| High ability (high motivation) | X | −0.40 | ||||

| Low ability (low motivation) | X | 0.20 | ||||

| Albarracín & Wyer’s (2001) Experiment 1 (moderate motivation) | ||||||

| High ability | X | −0.73 | ||||

| Low ability | X | 1.79* | ||||

| Albarracín & Wyer’s (2001) Experiment 3 | ||||||

| (moderate motivation) | ||||||

| High ability | X | −0.28 | ||||

| Low ability | X | 1.16* | ||||

Note. Conditions were classified as high thought when ability was high and motivation was either high or moderate. Conditions were classified as moderate thought when ability was low and motivation was moderate. Conditions were classified as low thought when ability was low and motivation was low. The effect of affect is represented with the difference between attitudes when affect was positive and attitudes when affect was negative. X indicates the amount of thought a given condition represents.

p < .05.

A possible post hoc arrangement of the conditions from the three experiments along the continuum of amount of thought appears in Table 5. The high level of thought comprises (a) the high-ability condition of Albarracín’s (1997) Experiment 1 (high ability, high motivation), (b) the high-ability condition of Albarracín and Wyer’s (2001) Experiment 1 (high ability, moderate motivation) and (c) the high-ability condition of Albarracín and Wyer’s Experiment 3 (high ability, moderate motivation). The moderate level of thought includes the low-ability conditions of Albarracín and Wyer’s (2001) Experiments 1 and 3 (low ability, moderate motivation). The low ability condition of Albarracín’s (1997) Experiment 1 represents the low level of thought (low ability, low motivation). A summary of the effects of affect across these three levels appears in Table 5. The mean differences represent the level of affect (see Table 1) and again suggest a quadratic effect of amount of thought on the influence of affect.

Suitability of Past Work to Detect Curvilinear Influences of Ability and Motivation on Affect

Prior research suggests that people consistently use affect as information when their ability and motivation to think about the issues are limited. For example, Petty et al. (1993) found that affect had direct influences on the attitudes of low-need-for-cognition participants but not on the attitudes of high-need-for-cognition individuals. Similarly, Ottati and Isbell (1996; see also Isbell & Wyer, 1999) found that participants with low motivation to process political information used affect as a basis for attitudes to a greater extent than did motivated participants, and Albarracín and Wyer (2001) observed an influence of affect on attitudes when distraction was higher but not when distraction was lower.

Nevertheless, past findings that affect as information emerges when ability or motivation are low are not inconsistent with the model in Figure 1, in part because past research has been ill suited to detect curvilinear patterns. For example, experiments in which only ability or only motivation are manipulated over two levels (e.g., Albarracín & Wyer, 2001; Petty et al., 1993) can serve to identify linear patterns but not quadratic trends. Likewise, dichotomizing need for cognition or other measures of motivation (see Isbell & Wyer, 1999; Ottati & Isbell, 1996; Petty et al., 1993; Wegener et al., 1994) is guaranteed to obscure any curvilinear impact of motivation on the influence of affect or any other variable. In contrast, our research manipulated both ability and motivation (as well as ability over three levels), thus allowing for a test of nonlinearity.