Abstract

The influences of strand twisting and bending (applied at room temperature) on the critical current densities, Jc, and n-values of MgB2 multifilamentary strands were evaluated at 4.2 K as function of applied field strength, B. Three types of MgB2 strand were evaluated: (i) advanced internal magnesium infiltration (AIMI)-processed strands with 18 filaments (AIMI-18), (ii) powder-in-tube (PIT) strands processed using a continuous tube forming and filling (CTFF) technique with 36 filaments (PIT-36) and (iii) CTFF processed PIT strands with 54 filaments (PIT-54). Transport measurements of Jc(B) and n-value at 4.2 K in fields of up to 10 T were made on: (i) PIT-54 after it was twisted (at room temperature) to twist pitch values, Lp, of 10–100 mm. Transport measurements of Jc(B) and n-value were performed at 4.2 K; (ii) PIT-36 and AIMI-18 after applying bending strains up to 0.6% at room temperature.

PIT-54 twisted to pitches of 100 mm down to 10 mm exhibited no degradation in Jc(B) and only small changes in n-value. Both the Jc(B) and n-value of PIT-36 were seen to be tolerant to bending strain of up to 0.4%. On the other hand, AIMI-18 showed ±10% changes in Jc(B) and significant scatter in n-value over the bending strain range of 0–0.6%.

1 Introduction

With a transition temperature Tc of 39 K, MgB2 offers the possibility of helium-free operation [1]. This, together with the fact that MgB2 is available as a round, multifilamentary, twisted strand presents it as a promising superconductor for 20 K application. Several different methods have been developed to fabricate MgB2 strands: (i) the in situ, powder-in-tube (PIT) process [2], (ii) the ex situ PIT process [3]; (iii) the in situ reactive magnesium infiltration process [4] and its recent variants. Recent years have seen significant developments of MgB2 strands [5–12]. The best transport properties so far have been seen in “advanced internal Mg infiltration” method (AIMI) strands with their 10 T, 4.2 K Jcs of over 104 A/cm2 [13]. Much developmental effort has focused on improving the critical current density, Jc, with less attention to n-values especially in the 10–30 K range, even though a high n-value is important for practical applications. Given the potential of MgB2 for liquid helium free applications, the values of Jc and n-value in the 5–30 K range is of substantial interest. Accordingly we report here on the Jcs and n-values of an 18-filament AIMI strand at fields of up to 12 T and at temperatures of from 4.2 K–30 K.

In addition to the high Jc and n-value requirements practical superconducting strands need to be both multifilamentary and twisted in the interests of flux jump stability and AC-loss reduction. The twisting process generates strain accompanied by the possibility of reduced Jc [14–18] and n-value. However, recent developments at HyperTech Research Inc (HTR) have led to strands with high filament counts and a satisfactory tolerance to pre-reaction twisting. Here we present a study of the twist-pitch dependence of Jc and n-value of a HTR processed PIT conductor.

In addition to satisfactory current transport and twist properties, the ability of a strand, and indeed a conductor assembled from it, to withstand bending strain is of interest for applications. It is of course possible to construct magnets using a wind-and-react technique, in which case bending strain is not a consideration, but insulation and the heat treatment of the coil former become issues. Magnets can also be constructed using a react-and-wind approach, which allows more flexibility in insulation, but requires that the strands be tolerant to post reaction bending during magnet winding. This type of strain is distinct from that experienced by the strand during magnet excitation in which case well-defined tensile, compressive, or transverse pressure induced strains will be applied at the operating temperature (4–30 K for MgB2). Such effects, resulting for example from thermal cycling stresses and Lorentz forces generated in MgB2 strands during magnet operation have been investigated [19–23]. In this study we focus on the effect of bending strain applied to reacted strands at room temperature, the relevant parameter for developing magnet winding procedures, cabling, and the spooling and re-spooling of reacted strands.

2 Experimental

2.1 Strand Fabrication

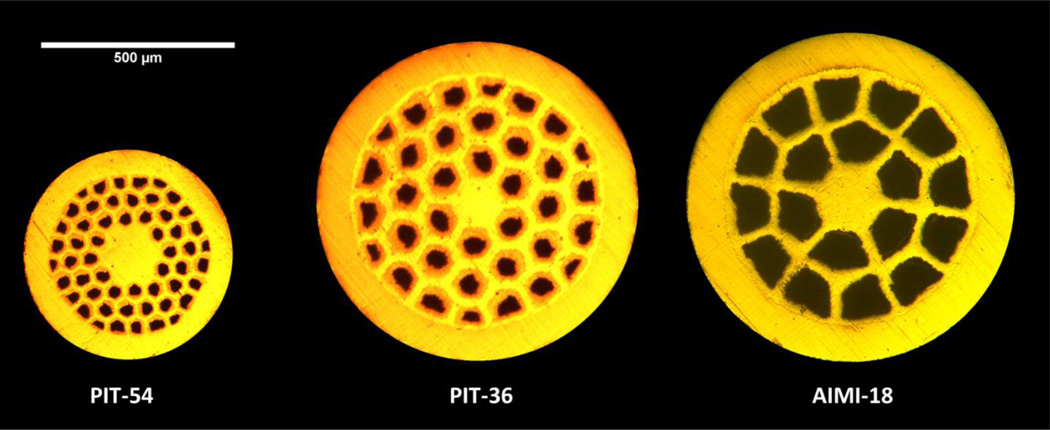

Specifications of the three types of MgB2 multifilamentary strands that were fabricated by HTR are given in Table I. Optical images of the strand cross sections are shown in Figure 1. One of the PIT strand, PIT-54, was fabricated using the continuous tube forming and filling (CTFF) process [11] in which the precursor powder mixture is continuously dispensed onto a Nb strip prior to its being formed into a tube. This filled Nb tube was then placed in a Cu10Ni tube to form a filament. These filaments, along with a central Cu10Ni filament, were bundled and placed in a Cu10Ni tube and the composite was drawn to 0.55 mm. In the fabrication of the other PIT strand, PIT-36, the same process was used, except that (i) the filled Nb tube was placed inside a Cu tube, (ii) a Cu central filament was used, (iii) a Monel® tube was used as the outer sheath and (iv) the strand was drawn to 0.83 mm. The AIMI strand, AIMI-18, had 18 sub-filaments, each of which made by placing a Mg rod along the axis of a B-power-filled Nb tube. These filaments, along with a central Nb filament, were bundled and placed inside a Nb/Monel® bi-layer tube. The composite was then drawn to an OD of 0.83 mm. Commercial Mg powder, 99%, 20–25 µm particle size, was used for the PIT strands. The B powder, manufactured by Specialty Metals Inc., was mostly amorphous, 50–100 nm in size. Undoped B was used in PIT-54, and 2% C pre-doped B was used in PIT-36 and AIMI-18. For all strands, a heat treatment of 675 °C for 60 min under flowing Ar was applied. Before heat treatment, a standard twisting process applied to the PIT-54 strand provided twist pitches, Lp, of from 10 mm to 100 mm. Bending of PIT-36 and AIMI-18 was applied after the HT.

Table I.

Specifications and properties of the strands

| Name | Filament No. |

Chemical Barrier |

Outer sheath |

Central filament |

B source |

Mg:B ratio |

OD, mm |

% area under Nb barrier |

Jc(4.2K,5T) 105 A/cm2 |

Test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PIT-54 | 54 | Nb | Cu10Ni | Cu10Ni | SMI | 1:2 | 0.55 | 14.5 | 0.6 | twist |

| PIT-36 | 36 | Nb | Monel® | Cu | 2%C SMI | 1:2 | 0.84 | 12.9 | 2 | bend |

| AIMI-18 | 18 | Nb | Monel® | Nb | 2%C SMI | 1.37:2 | 0.83 | 28.2 | 2 | bend |

Figure 1.

Optical cross section images of PIT-54, PIT-36 and AIMI-18 after reaction for 675 °C/60 min.

2.2 Transport Property Measurements

Critical current density, Jc, and n-value measurements were made on samples of strand about 5 cm long, voltage tap separation about 5 mm, at 4.2 K in transverse magnetic fields B of up to 10 T. The Jc criterion was 1 µV/cm. Reported here is the “non-barrier Jc” defined as the critical current normalized to the area within the Nb tube (the barrier). This measure, different from the layer Jc cited in materials optimization studies, is more appropriate for conductor performance comparisons. Two sample probes were used: (i) a “short-sample probe” in which the sample was immersed in pool-boiling liquid He, (ii) a “varitemp probe” in which the sample was cooled by exchange gas and a heater enabled variation of temperature up to 30 K [13,25].

2.3 Twist and Bend Testing

Twist-tolerance tests were performed on pre-reacted PIT-54. Bend-tolerance tests were performed on PIT-36 and AIMI-18 strands after reaction. The strands were straight during reaction. Afterwards they were uniformly bent at room temperature, a set of arc-shape dies made with G-10 material being used to control the bending process, Fig. 2. Assuming the neutral axis was at the geometric centre of the strands, the maximum bending strain is given by:

| (1) |

where Rw is the strand radius and RB is the radius of G-10 die. The values of RB and the corresponding maximal bending strains experienced by a 0.83 mm OD strand are listed in Table II. The strand was then allowed to relax mechanically, mounted onto the Jc test probe (without straightening even if deformation remained), cooled to temperature, and measured. In contrast to previous bend test measurements in which application of bending in-situ after cool down or the application of bending at room temperature and its retention during cool down [20, 21, 23], the present tests were designed to evaluate the tolerance of the strand to bending during react-and-wind coil fabrication or cable winding followed by operation at cryogenic temperatures.

Figure 2.

Apparatus used to apply a bending strain at room temperature. The wire to be bent is run between two pulleys, with weights used to apply a constant force. A shaped piece of G-10 in then raised until the bent wire lays along its whole curvature. The G10 piece is then retracted and the wire removed.

Table II.

Bending radius and bending strain for a 0.8 mm OD strand

| Bending radius, RB, mm |

Maximum bending strain, % |

|---|---|

| Inf.. | 0 |

| 379.3 | 0.1 |

| 180 | 0.2 |

| 125.5 | 0.3 |

| 94.6 | 0.4 |

| 76.3 | 0.5 |

| 63.1 | 0.6 |

3 Results of the Measurements

3.1 Transport Properties of the Starting Strands

Figure 3 represents the 4.2 K transport Jc(B)s for (a) strand PIT-54 and (b) strand PIT-36. The temperature dependence of transport Jc(B) for strand AIMI-18 is presented in Figure 3 (c). At 4.2 K, 5T, the Jc of PIT-36 was more than three times that of PIT-54 the increase being attributable to the effect of C doping. The 4.2 K, 5 T Jcs of PIT-36 and AIMI-18 were fortuitously about equal. However, increases in the latter’s MgB2-layer area would lead to superior performance, as discussed in [13].

Figure 3.

Transport properties of the starting strands: Jc vs B for (a) PIT-54, (b) PIT-36, and (c) AIMI-18. The n-value vs B of AIMI-18 is also represented in (d). Lines in (c) are fitting curves based on a modified percolation model for MgB2 strands [25]. Lines in (d) are fits to n ∝ e−m×B.

At 20 K, the non-barrier transport Jc of AIMI-18 is ≈ 104A/cm2 at 5 T. Even at 25 K a transport Jc of 104A/cm3 was obtained at 2 T. It is worth noting that these results for a multifilamentary AIMI strand offer promise for applications in the 20 K regime. A modified Eisterer percolation model [24–26] was used to fit the Jc vs B curves for various temperatures, Figure 3 (c). Figure 3 (d) displays vs the n vs B curves at various temperatures. The n-value is observed to follow

| (2) |

3.2 Influence of Twisting on Transport Properties

Figure 4 (a) shows the Jc-B behaviors of a series of twisted PIT-54 strands. PIT-54, with an OD of 0.55 mm and a sub-filament size of ~20 µm (left in Figure 1), was twisted to pitches of from 100 mm to 10 mm, a range useful for practical applications. Over the whole range of Lp values this strand exhibited no degradation in Jc at any field. Even the strand with a twist pitch as small as 10 mm exhibited Jc(B) behavior very close to that of the untwisted control. The n-values vs B for the PIT-54 are plotted in Figure 4 (b), where little influence of Lp on n-value is seen over the range investigated.

Figure 4.

4.2 K Transport properties of PIT-54 in response to twist pitch: (a) Jc vs B, and (b) n-value vs B.

3.3 Influence of Bending on Transport Properties

Figure 5 shows the 4.2 K transport results for PIT-36 in response to initial bending strains of 0 to 0.4% followed by release in terms of: (a) Jc(B) as function of applied field up to 10 T; (b) the relative change of Jc(B) as function of bending strain, defined as ; (c) n-value vs bending strain at various B up to 10 T. Figure 5 (b) shows that bending strains of up to 0.4% have only a small influence (< 5%) on Jc(B) is very small (<5%).

Figure 5.

4.2K transport results for PIT-36 in response to applied bending strain plus release: (a) Jc-B behavior, (b) the relative change of Jc vs bending strain, and (c) n-value vs bending strain at various B.

4 Discussion

4.1 Influence of Twisting

The Jc(B) degradation of twisted four-core MgB2 strands, made by an ex situ and in situ process, was reported by appeared at Lp < 71mm [14]. With Lp = 30 mm, a 30% Jc (5 T) decrease after twisting was also observed in the in situ strand and a 60% degradation in Jc(5 T) for the ex situ strand [14]. Kováč et al reported no degradation in Jc(B) of a 19-filementary MgB2 strand with Lp > 25 mm, claiming the high resistance to twisting was due predominantly to reinforcement by a stainless steel outer sheath [16, 17]. Compared to the MgB2 strands in [14–17], PIT-54 has a smaller OD, a smaller sub-filament size, and a higher filament-number. Our observations of no degradations of Jc(B) and n-value with Lp ≥ 10 mm augur well for the damage-free reduction of AC loss by twisting in MgB2 strands.

4.2 Influence of Bending

A linear increase in Jc of PIT MgB2 strands response to increasing tension has been reported by Kováč [18] and Nishijima[21]. Over 10% increases in 4.2 K Jc obtain at 6.5 T with 0.4% – 0.6% strain [19] and at 10 T with 0.54% strain [21], while the compression has been reported to reduce the Jc performance of MgB2[21]. In our case, the outer portion of the MgB2 strand is in tension while the inner portion is under compression during bending. The bending-strain independent Jc(B) of PIT-36 can be an average of the effect of tension and compression. Katagiri [23] reported a field-independent critical bending strain of a single-core PIT strand to be 0.45%. Although our PIT strand is 36-core, our results are quite consistent with Katagiri’s observation. The n-values of PIT-36 are insensitive to bend strain at field up to 10 T, as seen in Figure 5 (c). All these three figures indicate that the transport properties of PIT-36 are independent of bending strain up to 0.4% at 4.2 K and 4–10 T.

Figures 6(a), (b), and (c) show that this AIMI-18 does exhibit some measurable bending strain sensitivity, in particular: (i) Figure 6(a) indicates a small shift in Jc(B) in response to strain; (ii) Figure 6 (b) shows ΔJc to be weakly bend-strain dependent. For example at 8 T Jc rises by about 12% from 6.7 to 7.5×104 A/cm2 at 0.3% strain, drops to the starting value at 0.5% strain and continues to decreases to 6.2×104 A/cm2 at experimental bend-strain limit of 0.6%; (iii) Figure 6(c) depicts the strain dependence of n-value at selected applied fields; only in fields of 8 T and above is any approximation to a trend observable. The Jc(B) is relatively unchanged at 0.1% bending strain, which is probably due to the absence of plastic deformation at this stage; an increase in Jc with a further increased bending strain up to 0.3% indicates the strand is plastically deformed and the internal strain state of the MgB2 filaments starts to release; a further increase in bending strain gradually decreased the Jc(B) is due to the breakage of MgB2 grain connection. All these bending strain influences on Jc(B) are field-independent. Compared to the results of PIT-36, AIMI-18 represents a much larger pre-strain, which cannot be completely cancelled by the negative effect from the compression portion. Nishijima [21] found the reversible tensile strain of a single-filamentary IMD strand at 4.2 K and 10 T to be 0.67%, and the value for a single-core PIT strands to be 0.54%. Kováč [22] showed the reversible tensile strain of a four-filamentary IMD strand to be 0.43% at 4.2 K and 5 T, higher than the value of four-filamentary PIT strand (0.38%). An increase in the transport performances of AIMI-type strand of up to 10% as the bending strain increased to 0.3% was followed by a monotonic decrease with further increases in strain.

Figure 6.

4.2K transport results for AIMI-18 in response to applied bending strain plus release: (a) Jc-B behavior, (b) the relative change of Jc vs bending strain, and (c) n-value vs bending strain at various B.

5 Summary

The starting transport properties of PIT-54 and PIT-36 were measured in applied fields of up to 10 T at 4.2 K and in the case of AIMI-18 at temperatures up to 30 K. The 4.2 K, 5 T, non-barrier Jcs of PIT-54, PIT-36, and AIMI-18 were, respectively, 0.6, 2.0, and 2.0×105 A/cm2. Given that PIT-36 and AIMI-18 have the same strand ODs and non-barrier 4.2 K, 5 T Jcs but differing non-barrier areas for critical current normalization (13% and 28%, respectively), implies that AIMI-type strands have the potential, on an equal non-barrier-area basis for twice the Jc performance of PIT. AIMI-18 has a Jc of 104A/cm2 at 20 K and 5 T, as well as at 25 K and 2 T. Such a Jc for a multifilamentary AIMI strand augurs well for applications in the high temperature regime.

PIT-54 twisted to pitches of 100 mm down to 10 mm (duplicating a practically useful range) showed no degradation in Jc(B); even the strand with an Lp as small as 10 mm exhibited Jc(B) behavior very close to that of the untwisted control. Furthermore, little influence of Lp on n-value is seen over the range investigated. The absence of degradations in Jc(B) and n-value with Lp ≥ 10 mm enable a reduction in loss without damaging the transport properties of MgB2 strand.

In examinations of bend strain tolerance bending strains of up to 0.6% (corresponding to a bend of radius 63.1 applied to a 0.8 mm OD strand) were applied at room temperature to PIT-36 and AIMI-18. After bend relaxation the transport properties were measured at 4.2 K in applied fields of up to 10 T. For PIT-36 both Jc(B) and n(B) were found to be independent of bend strain within the above limit. AIMI-18 can be regarded as bend-strain tolerant up to about 0.5% strain. For example at 8 T Jc rises from 6.7 to 7.5×104 A/cm2 at 0.3% strain, drops to the starting value at 0.5% strain and continues to decreases to 6.2×104 A/cm2 at experimental bend-strain limit of 0.6%. The strain dependence of n-value shows considerable scatter.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the NIH, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, under R01EB018363, NASA Phase II SBIR and an NIH Bridge grant.

References

- 1.Nagamatsu J, Nakagawa N, Muranaka T, Zenitani Y, Akimitsu J. Superconductivity at 39 K in magnesium diboride. Nature. 2001;410:63. doi: 10.1038/35065039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collings EW, Sumption MD, Bhatia M, Susner MA, Bohnenstiehl SD. Prospects for improving the intrinsic and extrinsic properties of magnesium diboride superconducting strands. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2008;21:103001. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grasso G, Malagoli A, Modica M, Tumino A, Ferdeghini C, Siri A, Vignola C, Martini L, Previtali V, Volpini G. Fabrication and Properties of Monofilamentary MgB2 Superconducting Tapes. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2003;16:271–275. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giunchi G, Ripamonti G, Perini E, Cavallin T, Bassani E. Advancements in the Reactive Liquid Mg Infiltration Technique to Produce Long Superconducting MgB2 Tubular Strands. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2007;17:2761–2765. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Glowacki B, Majoros M, Vickers M, Evetts JE, Shi Y, McDougall I. Superconductivity of Powder-in-Tube MgB2 Strands. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2001;14:193–199. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soltanian S, Wang X, Kusevic I, Babic E, Li AH, Qin MJ, Horvat J, Liu HK, Colling EW, Lee E, Sumption MD, Dou SX. High-Transport Critical Current Density above 30 K in Pure Fe-clad MgB2 Tape. Physica C. 2001;361:84–90. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Susner MA, Sumption MD, Bhati M, Peng X, Tomsic MJ, Rindfleisch M, Collings EW. Influence of Mg/B Ratio and SiC Doping on Microstructure and High Field Transport Jc in MgB2 Strands. Physica C. 2007;456:180–187. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mahmud M, Susner MA, Sumption MD, Rindfleisch MA, Tomsic M, Yue J, Collings EW. Comparison of Critical Current Density in MgB2 with Different Boron Sources and Nano-Particle Dopant Additions. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2009;19:2756–2759. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen SK, Yates KA, Blamire MG, MacManus-Driscol JL. Strong Influence of Boron Precursor Powder on the Critical Current Density of MgB2. Supercond. Sci. and Tech. 2005;18:1473–1477. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dou SX, Shcherbakova O, Yeoh WK, Kim JH, Soltanian S, Wang XL, Senatore C, Flukiger R, Dhalle M, Husnjak O, Babic E. Mechanism of Enhancement in Electromagnetic Properties of MgB2 by Nano SiC Doping. Phys Rev Lett. 2007;98:097002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.98.097002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Collings EW, Lee E, Sumption MD, Tomsic M. Transport and Magnetic Properties of Continuously Processed MgB2. Rare Metal Mat. Eng. 2002;31:406–409. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Susner MA, Sumption MD, Rindfleisch M, Tomsic M, Collings EW. Influence of strand design, boron type, and carbon doping method on the transport properties of powder-in-tube MgB2-xCx strands. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2012;22:6200110. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li GZ, Sumption MD, Susner MA, Yang Y, Reddy KM, Rindfleisch MA, Tomsic MJ, Thong CJ, Collings EW. The critical current density of advanced internal-Mg-diffusion-processed MgB2 wires. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2012;25:115023. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kováč P, Hušek I, Melišek T, Martinez E, Dhalle M. Properties of doped ex and in situ MgB2 multi-filament superconductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2006;19:1076–1082. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malagoli A, Bernini C, Braccini V, Fanciulli C, Romano G, Vignolo M. Fabrication and superconducting properties of multifilamentary MgB2 conductors for AC purposes: twisted tapes and strands with very thin filaments. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2009;22:105017. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kováč P, Hušek I, Melišek T, Kopera L, Reissner M. Stainless steel reinforced multi-core MgB2 wire subjected to variable deformations, heat treatments and mechanical stressing. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2010;23:065010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kováč P, Hušek I, Melišek T, Kopera L. Filamentary MgB2 wires twisted before and after heat treatment. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2011;24:115006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kováč P, Kopera L, Melišek T, Rindfleisch M, Haessler W, Hušek I. Behaviour of filamentary MgB2 strands subjected to tensile stress at 4.2 K. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2013;26:105028. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kitaguchi H, Kumakura H, Togano K. Strain effect in MgB2/stainless steel superconducting tape. Physica C. 2001;363:198–201. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kitaguchi H, Kumakura H. Superconducting and mechanical performance and the strain effects of a multifilamentary MgB2/Ni tape. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2005;18:S284. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishijima G, Ye SJ, Matsumoto A, Togano K, Kumakura H, Kitaguchi H, Oguro H. Mechanical properties of MgB2 superconducting wires fabricated by internal Mg diffusion process. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2012;25:054012. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kováč P, Hušek I, Melišek T, Kopera L, Kováč J. Critical currents Ic-anisotropy and stress tolerance of MgB2 wires made by internal magnesium diffusion. Supcond. Sci. Technol. 2014;27:065003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katagiri K, Takaya R, Kasaba K, Tachikawa K, Yamada Y, Shimura S, Koshizuka N, Watanabe K. Stress–strain effects on powder-in-tube MgB2 tapes and wires. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2005;18:351–355. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eisterer M, Krutzler C, Weber HW. Influence of the upper critical-field anisotropy on the transport properties of polycrystalline MgB2. J Appl. Phys. 2005;98:033906. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eisterer M, Zehetmayer M, Weber HW. Current Percolation and Anisotropy in Polycrystalline MgB2. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2003;90:247002. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.90.247002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Susner MA. Diss. The Ohio State University; 2012. Influences of crystalline anisotropy, doping, porosity, and connectivity on the critical current densities of superconducting magnesium diboride bulks, strands, and thin film. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Martínez E, Martínez-López M, Millán A, Mikheenko P, Bevan A, Abellx JS. Temperature and Magnetic Field Dependence of the n-values of Superconductors. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2007;17:2738. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lezza P, Abächerli V, Clayton N, Senatore C, Uglietti D, Suo HL, Flükiger R. Transport properties and exponential n-values of Fe/MgB2 tapes with various MgB2 particle sizes. Physica C. 2003;401:305. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Martínez E, Angural A, Schlachter S, Kováč P. Transport and magnetic critical currents of Cu-stabilized monofilamentary MgB2 conductors. Supercond. Sci. Technol. 2009;22:015014. [Google Scholar]