Abstract

Background and study aims: Current evidence supporting the efficacy of peroral cholangioscopy (POC) in the evaluation and management of difficult bile duct stones and indeterminate strictures is limited. The aims of this systematic review and meta-analysis were to assess the following: the efficacy of POC for the therapy of difficult bile duct stones, the diagnostic accuracy of POC for the evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures, and the overall adverse event rates for POC.

Patients and methods: Patients referred for the removal of difficult bile duct stones or the evaluation of indeterminate strictures via POC were included. Search terms pertaining to cholangioscopy were used, and articles were selected based on preset inclusion and exclusion criteria. Quality assessment of the studies was completed with a modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale. After critical literature review, relevant outcomes of interest were analyzed. Meta-regression was performed to examine potential sources of between-study variation. Publication bias was assessed via funnel plots and Egger’s test.

Results: A total of 49 studies were included. The overall estimated stone clearance rate was 88 % (95 % confidence interval [95 %CI] 85 % – 91 %). The accuracy of POC was 89 % (95 %CI 84 % – 93 %) for making a visual diagnosis and and 79 % (95 %CI 74 % – 84 %) for making a histological diagnosis. The estimated overall adverse event rate was 7 % (95 %CI 6 % – 9 %).

Conclusions: POC is a safe and effective adjunctive tool with endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) for the evaluation of bile duct strictures and the treatment of bile duct stones when conventional methods have failed. Prospective, controlled clinical trials are needed to further elucidate the precise role of POC during ERCP.

Introduction

During the last several decades, many advances in technology have rendered peroral cholangioscopy (POC) a useful diagnostic and therapeutic technique. POC is conducted during endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) in one of three ways: with a dual-operator dedicated (“mother – daughter”) cholangioscopic system, with a single-operator catheter-based cholangioscopic system (SOC), or directly with an ultraslim endoscope or slim gastroscope. The procedures vary with respect to number of operators, maneuverability, image quality, and method of access, resulting in variable success rates.

POC is most commonly used for treating difficult bile duct stones with electrohydraulic lithotripsy or laser lithotripsy or for directly visualizing and/or sampling indeterminate biliary strictures. Other indications and reported uses for POC include, but are not limited to, placing a guidewire during ERCP, monitoring primary sclerosing cholangitis, facilitating stent placement for biliary drainage, assessing the extent of biliary malignancy before surgery, and staging and ablating biliary tumors 1 2 3 4. POC is a safe procedure associated with a low adverse event rate. Variable results have been published in regard to its efficacy and safety for these indications 5. As such, the aim of this study was to perform a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess (i) the overall clinical efficacy of POC for the therapy of difficult bile duct stones, (ii) the accuracy of POC for diagnosing indeterminate biliary strictures, and (iii) the overall adverse event rate of POC.

Patients and methods

This review and meta-analysis was performed in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement 6.

Information sources and medical literature search

A search for eligible publications was conducted via Ovid Medline, the Cochrane Library, and Scopus with the following key words: cholangiopancreatoscopy, choledochoscopy, pancreatocholangioscopy, cholangioscopy, and pancreatoscopy. Two authors (P. K. and S. K.) independently conducted a medical literature search and screened the resulting studies for inclusion. One reviewer (P. K.) extracted data from all studies that met inclusion criteria and stored relevant data in an Excel (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington, USA) database, and a second reviewer (S. K.) performed a second pass of data entry. A third reviewer (S. W.) resolved any discrepancies. EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, New York, New York, USA) was used for reference management.

Eligibility criteria

For the systematic review, our search included all clinical studies evaluating POC until December 2014.

Inclusion criteria were as follows: (i) studies that investigated POC for the removal of difficult bile duct stones, (ii) studies that investigated POC and its ability to help diagnose indeterminate biliary strictures, (iii) studies that enrolled more than 10 participants, and (iv) full-text articles in English. Notably, difficult bile duct stones were most often defined as stones that could not be removed via conventional methods (ERCP with standard extraction balloons, baskets, or lithotriptors; large endoscopic papillary balloon dilation). Indeterminate biliary strictures were most often defined as strictures that could not be definitively diagnosed with conventional ERCP sampling techniques (brushings, intraductal biopsy).

Exclusion criteria were as follows: (i) case reports, (ii) abstracts, (iii) reviews, (iv) letters to authors or editors, (v) studies evaluating percutaneous cholangioscopy, (vi) animal studies, and (vii) studies evaluating pancreatoscopy only.

Quality assessment

A modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale 7 was employed to assess the methodological quality of each study included in this review. The studies were divided into two groups: those in which biliary stone removal was an indication for POC and those in which POC was used for the diagnosis of indeterminate strictures; it should be noted that these two groups of studies are not mutually exclusive.

The scale assessed the following for “Selection” criteria: (i) representativeness of the exposed cohort, (ii) ascertainment of exposure, and (iii) demonstration that the outcome of interest was not present at the start of the study. The scale also assessed the following for “Outcome” criteria: (i) assessment by record linkage; (ii) follow-up length, which was determined to be an average follow-up in the study of at least 6 months for both the evaluation of recurrent stones and clinical follow-up for indeterminate strictures; and (iii) percentage of patients lost to follow-up, which was determined to be less than 15 %. Follow-up length and percentage of patients who were lost to follow-up were not used for studies evaluating biliary stone clearance because these factors are not commonly assessed in patients after stone removal.

Thus, according to the modified Newcastle-Ottawa Scale that was used, studies evaluating outcomes of POC for difficult bile duct stones could receive a maximum of four points, and studies evaluating outcomes of POC for indeterminate strictures could receive a maximum of six points. Any question regarding the allocation of points for each study was discussed by three reviewers (P. K., S. K., and S. W.).

List of items and data collected

The following data elements were extracted (if available) from each study included in the review: (i) publication year; (ii) number of centers involved (single center or multicenter); (iii) setting (university, multicenter, or community); (iv) study design (prospective, retrospective, or randomized controlled trial); (v) type of cholangioscopy (peroral dual-operator dedicated cholangioscope, peroral catheter-based cholangioscope [SpyGlass; Boston Scientific, Natick, Massachusetts, USA], direct peroral cholangioscope or ultraslim endoscope); (vi) study focus (stones, strictures, or both); (vii) sample size; (viii) number of POC procedures attempted; (ix) POC technical success rate (i. e., number of successful POC procedures divided by number attempted POC procedures); (x) adverse event rate; (xi) number of patients lost to follow up; and (xii) follow-up period (mean).

For studies evaluating the outcomes of POC for difficult bile duct stones, additional data included the following: (i) number of patients undergoing stone removal (denominator for stone clearance rate); (ii) stone clearance rate (rate of complete stone clearance, not including partial clearance); (iii) average number of stones per patient (mean); (iv) average stone size in millimeters (mean); (v) location of more than 75 % of stones (extrahepatic, intrahepatic, cystic, or mixed); (vi) stone removal technique (cholangioscopy-assisted basket or balloon, electrohydraulic lithotripsy, laser lithotripsy, or multiple methods); and (vii) stone recurrence rate.

For studies in which the outcomes of POC for indeterminate strictures were determined by visual impression only, additional relevant data included the following: (i) number of patients involved in the diagnostic study (denominator for accuracy), (ii) number of patients with true malignant disease (denominator for sensitivity), (iii) number of patients with true benign disease (denominator for specificity), (iv) sensitivity, (v) specificity, (vi) positive predictive value, (vii) negative predictive value, and (viii) accuracy.

For studies in which the outcomes of POC for indeterminate strictures were determined by directed tissue sampling, additional relevant data included the following: (i) number of patients or biopsy samples involved in the diagnostic study (denominator for accuracy), (ii) mean number of biopsy samples per patient/procedure, (iii) number of patients with true malignant disease (denominator for sensitivity), (iv) number of patients with true benign disease (denominator for specificity), (v) sensitivity, (vi) specificity, (vii) positive predictive value, (viii) negative predictive value, and (ix) accuracy.

Outcomes measured

The primary outcomes for studies evaluating POC for difficult bile duct stone included the following: (i) technical success rate (ability to achieve selective bile duct access), (ii) stone clearance rate, and (iii) stone recurrence rate. The primary outcomes for studies evaluating POC for indeterminate strictures included the following: (i) technical success rate (ability to achieve selective bile duct access), (ii) accuracy (both visual and directed tissue sampling), (iii) sensitivity (both visual and directed tissue sampling), and (iv) specificity (both visual and directed tissue sampling). The overall adverse event rate related to POC was determined.

Statistical analysis and summary measures

Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Software v2.0 (Biostat, Englewood, New Jersey, USA) was used for all formal meta-analyses (when the number of studies was more than five) to obtain summary estimates of proportions (stone clearance rate, technical success rates, stone recurrence rate, adverse event rates, sensitivities, specificities, and accuracy rates). Because of the assumption of inherently different study scenarios and study populations, a random effects model for all analyses was assumed. Heterogeneity across studies via a chi-squared test on the Q-statistic with appropriate degrees of freedom (dependent on outcome because not all studies uniformly reported all outcomes of interest) and the estimated measure of excess-to-total variation (I 2) across studies for each outcome of interest were also calculated. In instances in which the degrees of freedom were sufficiently large and there was significant evidence of between-study variation (i. e., heterogeneity), meta-regression to examine potential sources of between-study variation was performed.

Publication bias was assessed via funnel plots and Egger’s test on the regression intercept for these plots. In instances of significant evidence of publication bias (P < 0.05), imputed studies were used to create adjusted summary estimates for each measure. Other factors, such as differences in trial quality and true study heterogeneity, could produce asymmetry in funnel plots.

Results

Literature search and included studies

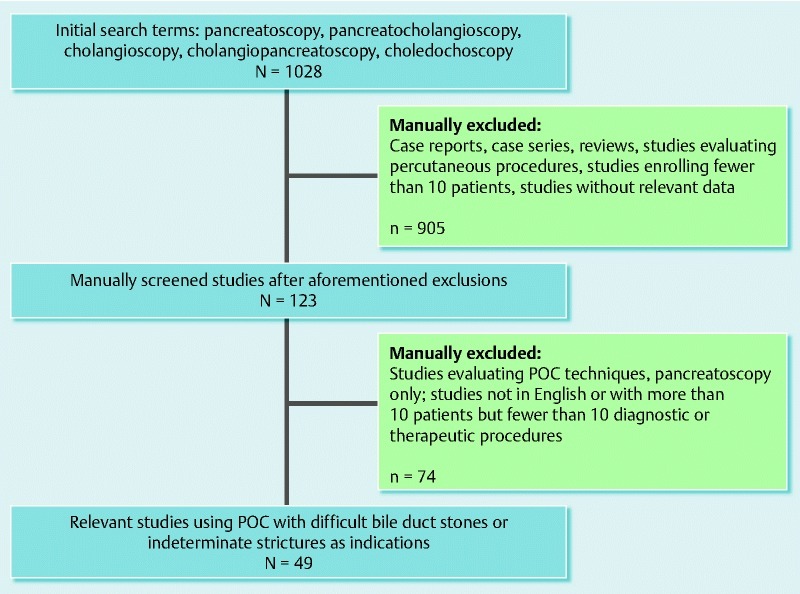

The outlined search strategy resulted in the identification of a total of 1028 studies. Based on the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria, a total of 49 studies 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 were included in the analysis (Fig. 1). Of the 49 studies evaluated, 33 contained data on difficult bile duct stones ( Table 1) and 29 studies contained data on indeterminate strictures (Table 2); there were 20 studies focusing only on difficult bile duct stones, 16 studies only on indeterminate strictures, and 13 studies on both.

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the selection of relevant studies. POC, peroral cholangioscopy.

Table 1. Characteristics of the stone studies included in a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of peroral cholangioscopy for difficult bile duct stones and indeterminate strictures.

| First author | Year | Setting | Study design | Type of POC | Sample size, n | Technical success rate | Patients undergoing stone removal, n | Stone clearance rate | Stones per patient, mean, n | Stone size, mean, mm | Location of > 75 % of stones | Stone removal method | Stone recurrence rate | Complication/adverse event rate | Patients lost to follow-up, n | NOS score |

| Akerman | 2012 | Single | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 34 | 0.97 | 11 | 0.64 | NR | NR | NR | EHL | NR | 0 | NR | 4 |

| Alameel | 2013 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 30 | NR | 10 | 0.9 | NR | NR | NR | EHL | NR | 0.05 | 0 | 4 |

| Arya | 2004 | Multicenter | Retrospective | Mother – daughter | 94 | NR | 94 | 0.9 | 1.92 | 0 | Mixed | EHL | 0.04 | 0.18 | NR | 4 |

| Awadallah | 2006 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 41 | NR | 9 | 0.78 | NR | NR | Mixed | EHL | NR | 0.05 | 1 | 4 |

| Chen | 2011 | Multicenter | Prospective | Catheter-based | 297 | 0.983 | 66 | 0.92 | NR | NR | Extrahepatic | Laser lithotripsy | NR | 0.075 | 20 | 4 |

| Chen | 2007 | Multicenter | Prospective | Catheter-based | 35 | NR | 9 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | Multiple methods | NR | 0.06 | 0 | 4 |

| Draganov | 2011 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 75 | 0.933 | 26 | 0.923 | 3.55 | 16.52 | NR | EHL | NR | 0.048 | 0 | 4 |

| Farnik | 2014 | Multicenter | Retrospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 89 | 0.885 | 23 | NR | NR | NR | NR | Multiple methods | NR | 0.077 | NR | 3 |

| Farrell | 2005 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 75 | NR | 26 | 1 | NR | 20 | Mixed | EHL | NR | 0 | NR | 4 |

| Fishman | 2009 | Single | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 128 | NR | 41 | 0.87 | NR | NR | NR | EHL | NR | 0 | NR | 4 |

| Huang | 2013 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 22 | 0.82 | 5 | 1 | NR | 13.4 | NR | POC-assisted basket | 0.182 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Itoi | 2012 | Single | Retrospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 24 | NR | 8 | 1 | NR | 12 | Intrahepatic | POC-assisted basket | NR | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Itoi | 2010 | Single | Retrospective | Mother – daughter | 108 | NR | 26 | 1 | 2.4 | 14.6 | NR | Multiple methods | NR | 0 | NR | 4 |

| Itoi | 2014 | Multicenter | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 41 | 0.83 | 8 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | Multiple methods | NR | 0.048 | NR | 4 |

| Jakobs | 2007 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 89 | NR | 17 | 0.824 | NR | 22 | NR | Laser lithotripsy | NR | 0 | NR | 3 |

| Jakobs | 1996 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 30 | NR | 10 | 0.83 | 2.7 | 18 | Mixed | Laser lithotripsy | NR | NR | NR | 4 |

| Kalaitzakis | 2012 | Multicenter | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 165 | 0.95 | 33 | 0.73 | NR | 18 | Extrahepatic | Multiple methods | NR | 0.09 | 4 | 4 |

| Kim | 2011 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 13 | 0.923 | 13 | 0.923 | 2.4 | 20.9 | NR | Laser lithotripsy | NR | 0.077 | 0 | 4 |

| Lee TY | 2012 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 10 | NR | 10 | 0.9 | 2.3 | 19 | Extrahepatic | Laser lithotripsy | NR | 0.1 | 0 | 4 |

| Lee YN | 2012 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 48 | 0.958 | 13 | 0.846 | 2.6 | 16.7 | Extrahepatic | POC-assisted basket | NR | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Maydeo | 2011 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 64 | NR | 60 | 1 | 1.5 | 23.4 | Extrahepatic | Laser lithotripsy | NR | 0.133 | 0 | 4 |

| Meves | 2014 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 84 | 0.87 | 11 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | Multiple methods | NR | 0.12 | NR | 4 |

| Moon | 2009 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 18 | 0.944 | 18 | 0.89 | 2.3 | 23.2 | Extrahepatic | Multiple methods | NR | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| Moon | 2009 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 29 | 0.78 | 4 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | Multiple methods | NR | 0 | NR | 4 |

| Mori | 2012 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 40 | 0.925 | 13 | 1 | NR | NR | NR | Multiple methods | NR | 0 | NR | 4 |

| Neuhaus | 1993 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 35 | NR | 12 | 0.83 | NR | 20 | Extrahepatic | Laser lithotripsy | NR | 0 | NR | 4 |

| Patel | 2014 | Multicenter | Prospective | Catheter-based | 69 | NR | 69 | 0.97 | NR | NR | Extrahepatic | Laser lithotripsy | NR | 0.041 | 0 | 4 |

| Piraka | 2007 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 32 | NR | 32 | 0.81 | NR | 12 | Mixed | EHL | 0.18 | 0.038 | 4 | 4 |

| Pohl | 2013 | Single | RCT | Mixed | 60 | 0.88 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | Multiple methods | NR | 0.117 | 0 | 3 |

| Sauer | 2013 | Single | Retrospective | Mixed | 20 | NR | 20 | 0.9 | 2.2 | 22 | Extrahepatic | Laser lithotripsy | NR | 0.25 | NR | 4 |

| Sepe | 2012 | Single | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 13 | NR | 13 | 0.769 | NR | 8 | Cystic | EHL | 0.077 | 0 | NR | 4 |

| Tsuyuguchi | 2011 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 122 | NR | 122 | 0.959 | 2.9 | 17 | NR | Multiple methods | 0.161 | NR | 6 | 3 |

| Tsuyuguchi | 2000 | Single | Retrospective | Mother – daughter | 25 | 0.92 | 22 | 0.82 | NR | 20 | NR | Multiple methods | 0.18 | 0.16 | 1 | 4 |

POC, peroral cholangioscopy; NR, not reported; EHL, electrohydraulic lithotripsy; NOS, Newcastle – Ottawa Scale.

Table 2. Characteristics of the stricture studies included in a systematic review and meta-analysis of the efficacy of peroral cholangioscopy for difficult bile duct stones and indeterminate strictures.

| First author | Year | Setting | Study design | Type of POC | Sample size | Technical success rate | Patients involved (VISUAL), n | Stricture sensitivity (VISUAL) | Stricture specificity (VISUAL) | Stricture accuracy (VISUAL) | Patients involved (BIOPSY), n | Biopsy samples per patient, mean, n | Stricture sensitivity (BIOPSY) | Stricture specificity (BIOPSY) | Stricture accuracy (BIOPSY) | Complication/adverse event rate | Patients lost to follow-up, n | Duration of follow-up, mean, mo | NOS score |

| Akerman | 2012 | Single | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 34 | 0.97 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | 0 | 3 |

| Alameel | 2013 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 30 | NR | 19 | 0.83 | 0.84 | 0.84 | 16 | NR | 0.4 | 1 | 0.81 | 0.05 | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Albert | 2011 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 22 | 0.88 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.045 | NR | 0 | 3 |

| Awadallah | 2006 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 41 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.05 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| Chen | 2011 | Multicenter | Prospective | Catheter-based | 297 | 0.983 | 95 | 0.78 | 0.82 | 0.8 | 95 | 3 | 0.49 | 0.98 | 0.75 | 0.075 | 20 | > 6 | 6 |

| Chen | 2007 | Multicenter | Prospective | Catheter-based | 35 | NR | 20 | 1 | 0.77 | 0.85 | 20 | 4.5 | 0.71 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.06 | 0 | > 6 | 6 |

| Draganov | 2011 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 75 | 0.933 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.048 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Draganov | 2012 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 26 | 1 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 26 | NR | 0.765 | 1 | 0.846 | 0.077 | 0 | 21.78 | 6 |

| Farnik | 2014 | Multicenter | Retrospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 89 | 0.885 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.077 | NR | 0 | 3 |

| Fishman | 2009 | Single | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 128 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | 0 | 3 |

| Fukuda | 2005 | Single | Retrospective | Mother – daughter | 97 | 1 | 76 | 1 | 0.87 | 0.934 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.02 | NR | > 12 | 6 |

| Hartman | 2012 | Single | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 89 | NR | 15 | 0.88 | 0.86 | 0.87 | 29 | 3 | 0.57 | 1 | 0.78 | NR | 3 | 23 | 5 |

| Itoi | 2014 | Multicenter | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 41 | 0.83 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.048 | NR | 0 | 3 |

| Itoi | 2010 | Multicenter | Retrospective | Mother – daughter | 144 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | 1.6 | NR | NR | NR | 0.07 | 0 | > 12 | 6 |

| Kalaitzakis | 2012 | Multicenter | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 165 | 0.95 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 49 | 3 | 0.62 | 1 | 0.84 | 0.09 | 4 | 15 | 5 |

| Khan | 2013 | Single | Retrospective | NA | 66 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 66 | NR | 0.487 | 0.963 | 0.68 | NR | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Liu | 2014 | Multicenter | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 25 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | 0 | 4 |

| Manta | 2013 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 52 | 1 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 42 | NR | 0.88 | 0.94 | 0.9 | 0.038 | 0 | 24 | 6 |

| Meves | 2014 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 84 | 0.87 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 26 | NR | 0.895 | NR | NR | 0.12 | NR | 0 | 4 |

| Moon | 2009 | Single | Prospective | Ultraslim endoscope | 29 | 0.78 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | 0 | 3 |

| Nguyen | 2013 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 40 | 0.947 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 18 | NR | NR | NR | 0.89 | 0.05 | 0 | 22 | 6 |

| Nishikawa | 2013 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 33 | 1 | 33 | 1 | 0.917 | 0.97 | 33 | 2.39 | 0.381 | 1 | 0.606 | 0.06 | 0 | > 12 | 6 |

| Osanai | 2013 | Multicenter | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 87 | 1 | 38 | 0.964 | 0.8 | 0.921 | 35 | 2.4 | 0.815 | 1 | 0.857 | 0.069 | 0 | > 12 | 6 |

| Pohl | 2013 | Single | RCT | Mixed | 60 | 0.88 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.117 | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Ramchandani | 2011 | Single | Prospective | Catheter-based | 36 | 1 | 36 | 0.95 | 0.79 | 0.89 | 33 | 3.5 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.82 | 0.083 | 0 | > 6 | 6 |

| Shah | 2006 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 62 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0.056 | 4 | 12.4 | 6 |

| Siddiqui | 2012 | Single | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 30 | NR | 0 | NR | NR | NR | 30 | NR | 0.77 | NR | NR | 0.033 | 0 | > 6 | 6 |

| Tischendorf | 2006 | Single | Prospective | Mother – daughter | 53 | 1 | 53 | 0.92 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0 | NR | NR | NR | NR | 0 | 0 | 37 | 6 |

| Woo | 2014 | Single | Retrospective | Catheter-based | 32 | NR | 31 | 1 | 0.9 | 0.967 | 19 | 2.84 | 0.642 | 1 | 0.736 | 0.094 | 0 | > 6 | 6 |

POC, peroral cholangioscopy; NR, not reported; NA, not applicable; NOS, Newcastle – Ottawa Scale.

Efficacy of peroral cholangioscopy for difficult bile duct stones

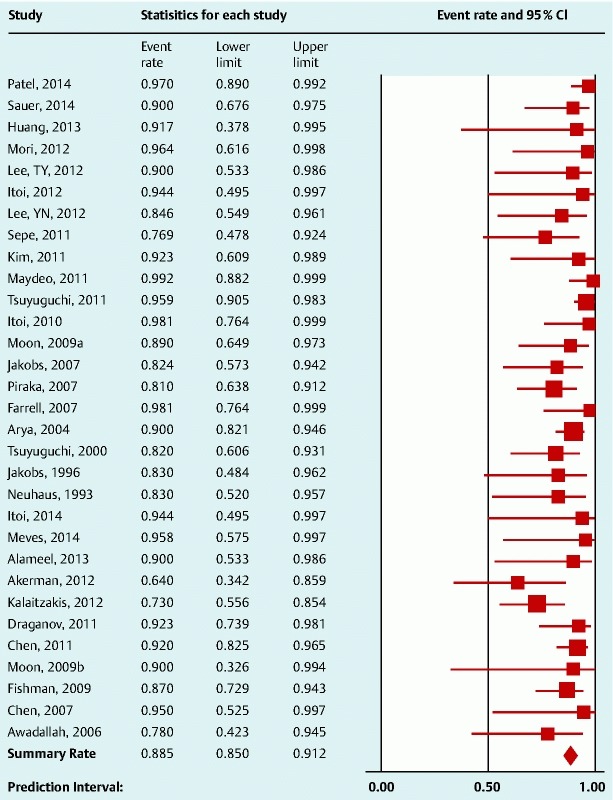

The overall estimated stone clearance rate (n = 31 studies) was 88 % (95 % confidence interval [95CI] 85 % – 91 %), without significant evidence of heterogeneity (P = 0.09, I 2 = 26.14) (Fig. 2). There was evidence of publication bias (P = 0.0466) in this analysis. Imputed values would fall below the estimated mean rate with larger standard errors, and the adjusted stone clearance rate according to the trim and fill method of Duval and Tweedie 57 is 85 % (95 %CI 82 % – 88 %). Study year, study design, stone size, stone location, number of stones, and type of POC had no impact on stone clearance rates based on meta-regression analysis with regard to stone clearance.

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of studies reporting bile duct stone clearance rate with peroral cholangioscopy. Pooled clearance rate was 88 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 85 % – 91 %).

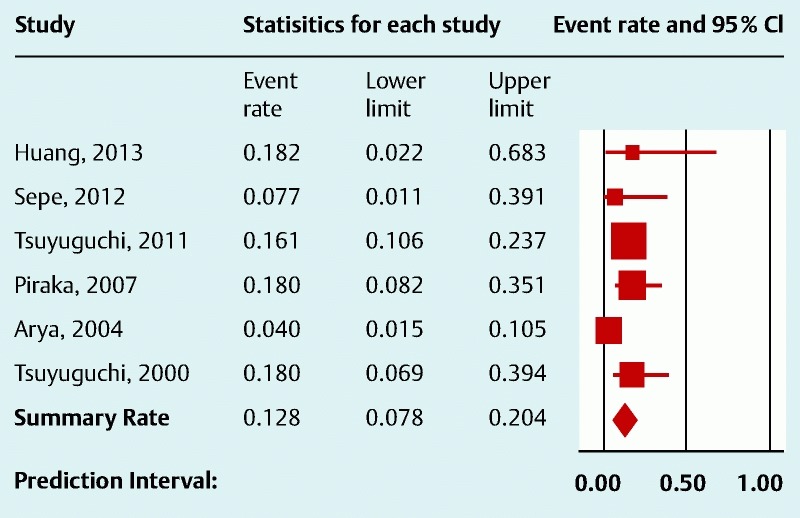

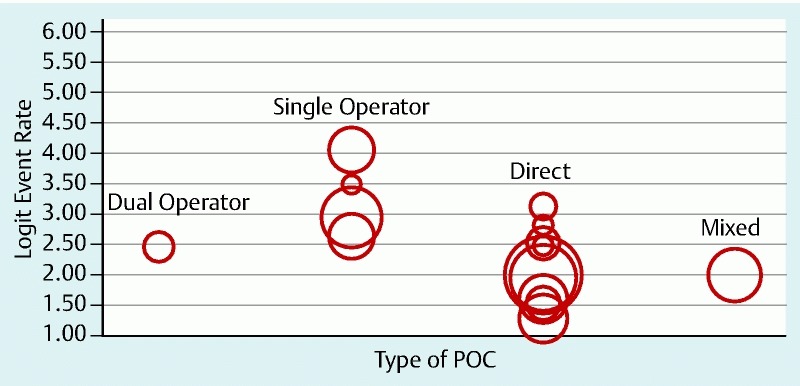

The estimated stone recurrence rate (n = 6 studies) was 13 % (95 %CI 7 % – 20 %) ( Fig. 3) with no evidence of heterogeneity (P = 0.13, I 2 = 40.09) or publication bias (P = 0.55). The estimated technical success rate (n = 15 studies) was 91 % (95 %CI 88 % – 94 %) ( Fig. 4), with evidence of heterogeneity (P < 0.01, I 2 = 61.72). Meta-regression identified a significant association between the type of POC used and technical success rates, with SOC demonstrating higher technical success rates compared with other methods (P < 0.01) (Fig. 5).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of studies reporting stone recurrence rate after clearance by peroral cholangioscopy. Pooled recurrence rate was 13 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 7 % – 20 %).

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of studies reporting technical success rate of peroral cholangioscopy for stone-related indications. Pooled success rate was 91 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 88 % – 94 %).

Fig. 5.

Relationship between technical success rate for stone-related indications and type of peroral cholangioscopy (POC). Single-operator catheter-based cholangiography had a higher rate of technical success for stone-related indications compared with other methods.

Efficacy of peroral cholangioscopy for indeterminate strictures

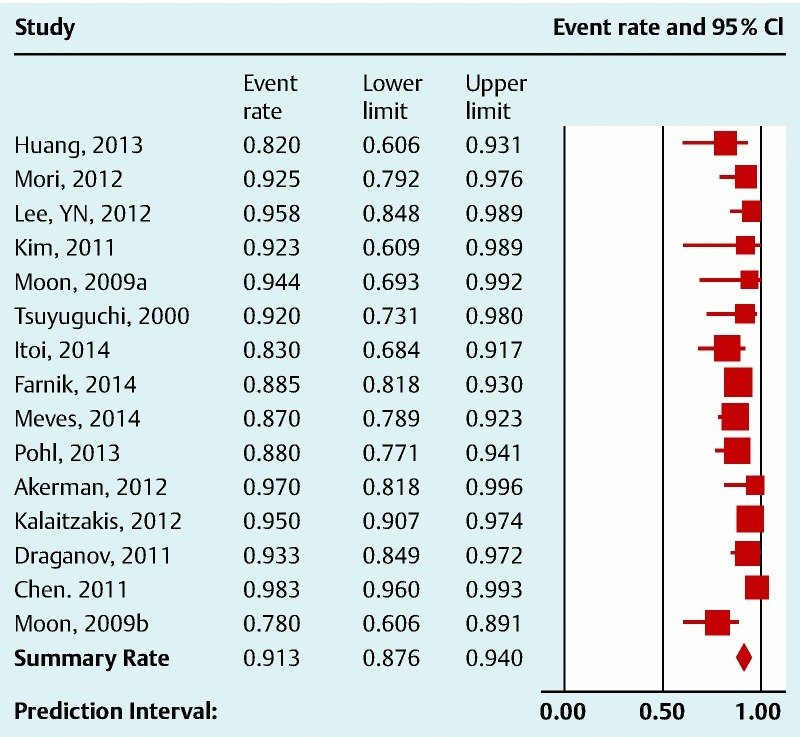

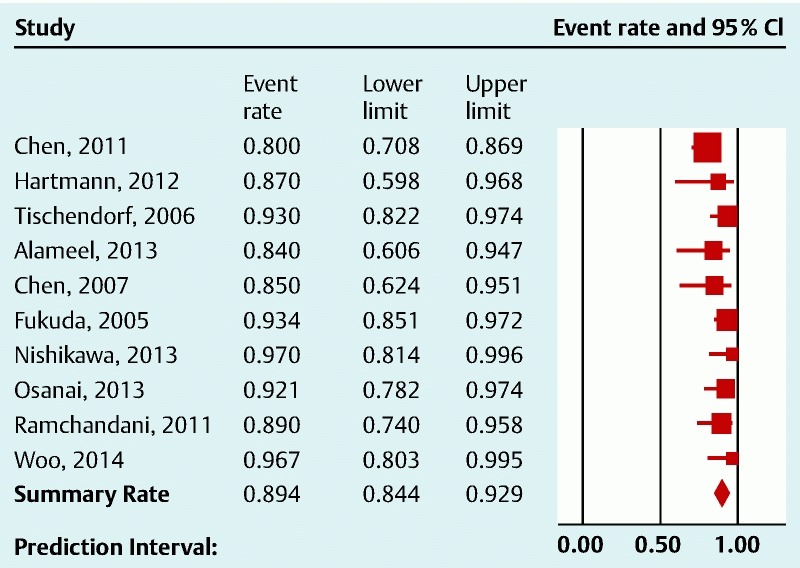

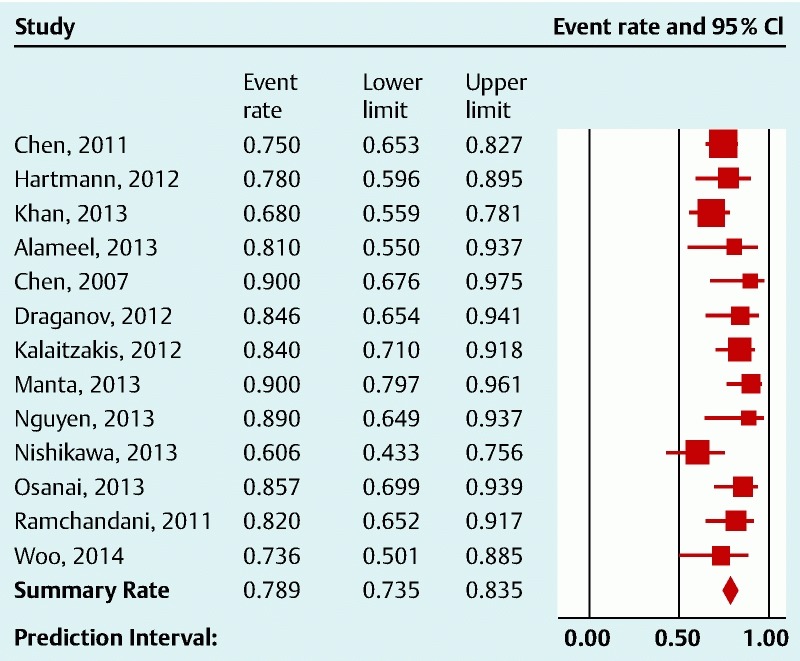

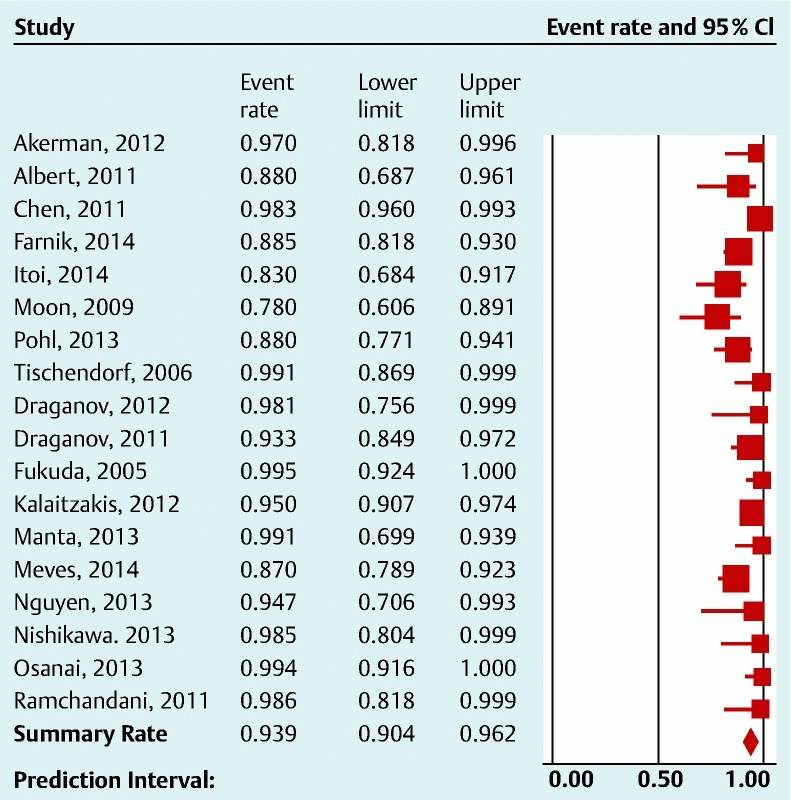

The diagnostic characteristics of POC for visual impression were as follows (Table 3): accuracy (n = 10 studies), 89 % (95 %CI 84 % – 93 %) (Fig. 6); sensitivity (n = 9 studies), 93 % (95 %CI 85 % – 97 %); specificity (n = 9 studies), 85 % (95 %CI 79 % – 89 %). In each case, there was no significant evidence of heterogeneity. The diagnostic characteristics of POC for directed tissue sampling were as follows (Table 3): accuracy (n = 13 studies), 79 % (95 %CI 74 % – 84 %) ( Fig.7); sensitivity (n = 12 studies), 69 % (95 %CI 57 % – 78 %); specificity (n = 10 studies), 94 % (95 %CI 89 % – 97 %). Meta-regression identified a significant association between the type of POC used and visual accuracy (P < 0.01) and between the type of POC used and visual sensitivity (P = 0.01), with dual-operator cholangioscopy having higher rates compared with SOC. There was a potential trend toward an association between the number of biopsies and accuracy (P = 0.077) such that an increased number of biopsies was associated with increased accuracy. The estimated technical success rate (n = 18 studies) was 94 % (95 %CI 90 % – 96 %) (Fig. 8), with significant evidence of heterogeneity (P < 0.011, I 2 = 67.39).

Table 3. Efficacy and safety of peroral cholangioscopy for the removal of bile duct stones and the diagnosis of indeterminate strictures.

| Estimated | 95 % CI | I2 |

Heterogeneity?

(P value) |

Publication bias?

(P value) |

|

| Stones | |||||

| Clearance rate | 88 % | 85 % – 91 % | 26.14 | No (0.09) | Yes (0.05) |

| Recurrence rate | 13 % | 7 % – 20 % | 40.09 | No (0.14) | No (0.56) |

| Technical success rate | 91 % | 88 % – 94 % | 61.72 | Yes ( < 0.01) | No (0.32) |

| Strictures | |||||

| Visual accuracy | 89 % | 84 % – 93 % | 35.21 | No (0.13) | Yes (0.01) |

| Visual sensitivity | 93 % | 85 % – 97 % | 38.46 | No (0.11) | Yes ( < 0.01) |

| Visual specificity | 85 % | 79 % – 89 % | 0 | No (0.84) | No (0.50) |

| Biopsy accuracy | 79 % | 74 % – 84 % | 19.12 | No (0.09) | Yes (0.01) |

| Biopsy sensitivity | 69 % | 57 % – 78 % | 97.97 | Yes ( < 0.01) | No (0.07) |

| Biopsy specificity | 94 % | 89 % – 97 % | 0 | No (0.88) | No (0.18) |

| Technical success rate | 94 % | 90 % – 96 % | 67.39 | Yes ( < 0.01) | Yes ( < 0.01) |

| Adverse event rate | |||||

| Overall | 7 % | 6 % – 9 % | 32.36 | Yes (0.02) | Yes ( < 0.01) |

| Pancreatitis | 2 % | 2 % – 3 % | 0 | No (0.99) | Yes ( < 0.01) |

| Cholangitis | 4 % | 3 % – 5 % | 25.55 | No (0.06) | Yes ( < 0.01) |

| Perforation | 1 % | 1 % – 2 % | 0 | No (0.99) | No (0.73) |

| Other events | 3 % | 2 % – 4 % | 37.74 | Yes (0.01) | Yes ( < 0.01) |

| Serious events | 1 % | 1 % – 2 % | 0 | No (0.99) | No (0.28) |

CI, confidence interval.

Fig. 6.

Forest plot of studies reporting visual accuracy of peroral cholangioscopy in diagnosing indeterminate biliary strictures. Pooled accuracy rate was 89 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 84 % – 93 %).

Fig. 7.

Forest plot of studies reporting biopsy accuracy of peroral cholangioscopy in diagnosing indeterminate biliary strictures. Pooled accuracy rate was 79 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 74 % – 94 %).

Fig. 8.

Forest plot of studies reporting technical success rate of peroral cholangioscopy for stricture-related indications. Pooled success rate was 94 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 90 % – 96 %).

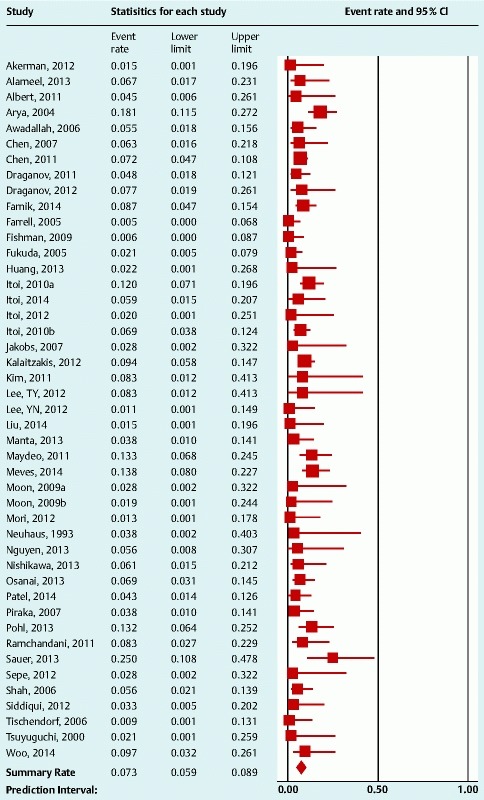

Adverse events of peroral cholangioscopy

The estimated overall adverse event rate was 7 % (95 %CI 6 % – 9 %) ( Fig.9). The estimated rates of pancreatitis, cholangitis, perforation, and other adverse events were 2 % (95 %CI 2 % – 3 %), 4 % (95 %CI 3 % – 5 %), 1 % (95 %CI 1 % – 2 %), and 3 % (95 %CI 2 % – 4 %), respectively. The estimated rate of severe adverse events was 1 % (95 %CI 1 % – 2 %).

Fig. 9.

Forest plot of studies reporting overall adverse event rates of peroral cholangioscopy. Pooled event rate was 7 % (95 % confidence interval [CI] 6 % – 9 %).

Discussion

POC has become a valuable tool for the treatment of difficult bile duct stones and the evaluation of indeterminate strictures. Despite increasing clinical use, there are very limited composite data evaluating its efficacy and safety. The aims of this study were to systematically review and analyze the efficacy of POC for difficult bile duct stones and indeterminate biliary strictures. The results of this systematic review and meta-analysis demonstrate a high stone clearance rate with the use of POC for difficult bile duct stones (88 %, 95 %CI 85 % – 91 %). Similarly, POC showed an accuracy of 89 % (95 %CI 84 % – 93 %) for visual impression of indeterminate biliary strictures and of 79 % (95 %CI 74 % – 84 %) for directed tissue sampling. Finally, POC was noted to have an overall low adverse event rate (7 %, 95 %CI 6 % – 9 %).

This analysis found that the accuracy of the visual impression was greater than biopsy-related accuracy, likely because of the high sensitivity of visual impression and poor sensitivity of biopsies. Currently, there is no standardized classification system used to help make a visual diagnosis of malignancy. However, studies evaluating POC for visual impression used characteristics such as the presence of irregular mucosa, an intraductal mass, or a tumor vessel to qualify a lesion as malignant, as these findings are often suggestive of malignancy 9 14 20 43 44 48 53 56. It should be noted, however, that the data on the diagnostic characteristics of these individual characteristics are limited at the present time. Given the low specificity of visual impression, it cannot be used alone to confirm a diagnosis. This analysis also found that SOC systems had a significantly reduced sensitivity for visual impression when compared with dual-operator cholangioscopes. This is likely due to the fact that SOC systems provide a fiberoptic image that is of poorer quality than the digital image obtained with dual-operator cholangioscopes.

The suboptimal biopsy-related accuracy of POC was attributed to low overall sensitivity. This highlights the technical challenges of sampling indeterminate biliary strictures and calls for an improvement in tissue acquisition techniques. Our analysis found a statistically insignificant but potential trend toward greater accuracy with an increased number of biopsies. As suggested by Kalaitzakis et al. 29, taking more biopsy samples may result in an increased sensitivity (and potentially accuracy) for making a histological diagnosis. The high sensitivity of visual impression and high specificity of POC-directed biopsy make a combined approach, rather than the individual use of each, likely the most helpful method for making a diagnosis of malignancy.

Two meta-analyses 58 59 have assessed the efficacy and diagnostic performance of SOC for indeterminate biliary strictures. One study 58 concluded that visual impression is useful for detecting a malignant lesion, and the other 59 that SOC biopsies have a moderate sensitivity for diagnosing malignant strictures. Both studies revealed that SOC is useful in confirming a malignant diagnosis because of its high specificity. One notable difference in this meta-analysis is that the studies involved looked at all types of POC and were not limited to SOC. However, the data from this meta-analysis are in concordance with those of the aforementioned meta-analyses in that they reveal a high sensitivity of visual impression for the detection of malignant strictures and a high specificity associated with biopsy that can be useful in the confirmation of a malignant diagnosis.

POC appears to be a relatively safe procedure with a very low rate of serious events (1 %, 95 %CI 1 % – 2 %). The data obtained in this systematic review and meta-analysis provide point estimates of adverse events that may be used in discussions with patients before a procedure. Notably, the patients undergoing POC have failed ERCP; this may be because they have more difficult anatomy or unusual lesions that require more manipulation. As such, there is a component of selection bias when patients are chosen to undergo POC. A recent study 60, completed in Sweden based on a national registry, reported that the risk for intra- and post-procedural adverse events is significantly increased when a patient undergoes POC in conjunction with ERCP, as opposed to ERCP alone. However, the study also noted that in a multivariate analysis that adjusted for confounders, the risk for pancreatitis and cholangitis was not increased. Of note, a systematic survey evaluating the incidence rates of post-ERCP complications 61 revealed an ERCP complication rate of approximately 6.85 %, with a severe event rate of approximately 1.67 %. These figures are comparable with the adverse event rates for POC estimated in this meta-analysis. Overall, it is clear that further research and data comparing POC with ERCP alone or with EUS are needed to compare the rates of adverse events and determine whether there is an increased adverse event rate with POC.

Limitations to this analysis included study heterogeneity and variability in the type of POC used. The studies had various patient populations, and the procedures were completed by using various methods of POC as well as differing instruments within each method. Furthermore, interoperator variability cannot be accounted for. Also, the definition of adverse event varied from study to study and accounted only for what was reported by the authors of each study. For example, some studies documented minor bleeding and considered it an adverse event, whereas others did not. It should also be noted that are various types of difficult stones – large stones, confluence stones, impacted stones, etc. Although the meta-regression found no association between the size and location of stones, confluence stones and impacted stones were not specifically addressed in most studies. Therefore, they could not be distinctly evaluated in this analysis. Finally, it is important to make a distinction between filling defects caused by malignant strictures and filling defects caused by extrinsic compression/factors. Unfortunately, information on the latter was often very limited and not made distinct in the literature. Thus, the use of POC for detecting malignancy in filling defects caused by external compression or other factors could not be analyzed in this study.

POC is a safe and effective adjunctive tool with ERCP for the evaluation of bile duct strictures and for the treatment of bile duct stones when conventional methods have failed. Despite the increasing utilization of POC and technical advances such as the recently introduced digital single-operator cholangioscope, the current systematic review and meta-analysis confirm the paucity of high level evidence supporting the use of POC. Prospective, controlled clinical trials are needed to further elucidate the precise role of POC and develop criteria that can be used to standardize the diagnosis and treatment of pancreaticobiliary diseases.

Footnotes

Competing interests: V. Raman Muthusamy, MD, and Srinadh Komanduri, MD, are consultants for Boston Scientific.

References

- 1.Brauer B C, Shah R J. Cholangioscopy in liver disease. Clin Liver Dis. 2014;18:927–944. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2014.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moon J H, Terheggen G, Choi H J. et al. Peroral cholangioscopy: diagnostic and therapeutic applications. Gastroenterology. 2013;144:276–282. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.10.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parsi M A. Peroral cholangioscopy in the new millennium. World J Gastroenterol. 2011;17:1–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v17.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waxman I, Chennat J, Konda V. Peroral direct cholangioscopic-guided selective intrahepatic duct stent placement with an ultraslim endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:875–878. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shah R J Cholangioscopy and pancreatoscopyIn: Howell DA, ed. UpToDate.Waltham, MA: UpToDate; Last updated August 3, 2015

- 6.Liberati A, Altman D G, Tetzlaff J. et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. Ann Intern Med. 2009;151:W65–W94. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-4-200908180-00136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wells G A, Shea B, Peterson J EA, Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Ottawa Hospital Research Institute; 2014. The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analyses.

- 8.Akerman S, Rahman M, Bernstein D E. Direct cholangioscopy: the North Shore experience. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:1406–1409. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e328357eb1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alameel T, Bain V, Sandha G. Clinical application of a single-operator direct visualization system improves the diagnostic and therapeutic yield of endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Can J Gastroenterol. 2013;27:15–19. doi: 10.1155/2013/278758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Albert J G, Friedrich-Rust M, Elhendawy M. et al. Peroral cholangioscopy for diagnosis and therapy of biliary tract disease using an ultra-slim gastroscope. [Erratum appears in Endoscopy 2011; 43: 1009] Endoscopy. 2011;43:1004–1009. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1256623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arya N, Nelles S E, Haber G B. et al. Electrohydraulic lithotripsy in 111 patients: a safe and effective therapy for difficult bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:2330–2334. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.40251.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Awadallah N S, Chen Y K, Piraka C. et al. Is there a role for cholangioscopy in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis? Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:284–291. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00383.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Y K, Parsi M A, Binmoeller K F. et al. Single-operator cholangioscopy in patients requiring evaluation of bile duct disease or therapy of biliary stones (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:805–814. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen Y K, Pleskow D K. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832–841. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Draganov P V, Chauhan S, Wagh M S. et al. Diagnostic accuracy of conventional and cholangioscopy-guided sampling of indeterminate biliary lesions at the time of ERCP: a prospective, long-term follow-up study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:347–353. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Draganov P V, Lin T, Chauhan S. et al. Prospective evaluation of the clinical utility of ERCP-guided cholangiopancreatoscopy with a new direct visualization system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;73:971–979. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farnik H, Weigt J, Malfertheiner P. et al. A multicenter study on the role of direct retrograde cholangioscopy in patients with inconclusive endoscopic retrograde cholangiography. Endoscopy. 2014;46:16–21. doi: 10.1055/s-0033-1359043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Farrell J J, Bounds B C, Al-Shalabi S. et al. Single-operator duodenoscope-assisted cholangioscopy is an effective alternative in the management of choledocholithiasis not removed by conventional methods, including mechanical lithotripsy. Endoscopy. 2005;37:542–547. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-861306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fishman D S. Management of pancreaticobiliary disease using a new intra-ductal endoscope: the Texas experience. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:1353–1358. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.1353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fukuda Y, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y. et al. Diagnostic utility of peroral cholangioscopy for various bile-duct lesions. Gastrointest Endosc. 2005;62:374–382. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.04.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hartman D J, Slivka A, Giusto D A. et al. Tissue yield and diagnostic efficacy of fluoroscopic and cholangioscopic techniques to assess indeterminate biliary strictures. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10:1042–1046. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang S W, Lin C H, Lee M S. et al. Residual common bile duct stones on direct peroral cholangioscopy using ultraslim endoscope. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:4966–4972. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i30.4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Itoi T, Reddy N D, Sofuni A. et al. Clinical evaluation of a prototype multi-bending peroral direct cholangioscope. Dig. 2014;26:100–107. doi: 10.1111/den.12082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Itoi T, Osanai M, Igarashi Y. et al. Diagnostic peroral video cholangioscopy is an accurate diagnostic tool for patients with bile duct lesions. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2010;8:934–938. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.06.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F. et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic peroral direct cholangioscopy in patients with altered GI anatomy (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:441–449. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.09.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Itoi T, Sofuni A, Itokawa F. et al. Evaluation of residual bile duct stones by peroral cholangioscopy in comparison with balloon-cholangiography. Digestive Endoscopy. 2010;22:S85–S89. doi: 10.1111/j.1443-1661.2010.00954.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakobs R, Maier M, Kohler B. et al. Peroral laser lithotripsy of difficult intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile duct stones: laser effectiveness using an automatic stone-tissue discrimination system. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:468–473. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jakobs R, Pereira-Lima J C, Schuch A W. et al. Endoscopic laser lithotripsy for complicated bile duct stones: is cholangioscopic guidance necessary? Arq Gastroenterol. 2007;44:137–140. doi: 10.1590/s0004-28032007000200010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kalaitzakis E, Webster G J, Oppong K W. et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic utility of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy for indeterminate biliary lesions and bile duct stones. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:656–664. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283526fa1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Khan A H, Austin G L, Fukami N. et al. Cholangiopancreatoscopy and endoscopic ultrasound for indeterminate pancreaticobiliary pathology. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:1110–1115. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2471-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim H I, Moon J H, Choi H J. et al. Holmium laser lithotripsy under direct peroral cholangioscopy by using an ultra-slim upper endoscope for patients with retained bile duct stones (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1127–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee T Y, Cheon Y K, Choe W H. et al. Direct cholangioscopy-based holmium laser lithotripsy of difficult bile duct stones by using an ultrathin upper endoscope without a separate biliary irrigating catheter. Photomed Laser Surg. 2012;30:31–36. doi: 10.1089/pho.2011.3094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee Y N, Moon J H, Choi H J. et al. Direct peroral cholangioscopy using an ultraslim upper endoscope for management of residual stones after mechanical lithotripsy for retained common bile duct stones. Endoscopy. 2012;44:819–824. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Liu R, Cox Rn K, Siddiqui A. et al. Peroral cholangioscopy facilitates targeted tissue acquisition in patients with suspected cholangiocarcinoma. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2014;60:127–133. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Manta R, Frazzoni M, Conigliaro R. et al. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in the evaluation of indeterminate biliary lesions: a single-center, prospective, cohort study. Surg Endosc. 2013;27:1569–1572. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2628-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Maydeo A, Kwek B E, Bhandari S. et al. Single-operator cholangioscopy-guided laser lithotripsy in patients with difficult biliary and pancreatic ductal stones (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:1308–1314. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Meves V, Ell C, Pohl J. Efficacy and safety of direct transnasal cholangioscopy with standard ultraslim endoscopes: results of a large cohort study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:88–94. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moon J H, Ko B M, Choi H J. et al. Intraductal balloon-guided direct peroral cholangioscopy with an ultraslim upper endoscope (with videos) Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;70:297–302. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moon J H, Ko B M, Choi H J. et al. Direct peroral cholangioscopy using an ultra-slim upper endoscope for the treatment of retained bile duct stones. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2729–2733. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.435. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mori A, Ohashi N, Nozaki M. et al. Feasibility of duodenal balloon-assisted direct cholangioscopy with an ultrathin upper endoscope. Endoscopy. 2012;44:1037–1044. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1309467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Neuhaus H, Hoffmann W, Zillinger C. et al. Laser lithotripsy of difficult bile duct stones under direct visual control. Gut. 1993;34:415–421. doi: 10.1136/gut.34.3.415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen N Q, Schoeman M N, Ruszkiewicz A. Clinical utility of EUS before cholangioscopy in the evaluation of difficult biliary strictures. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:868–874. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishikawa T, Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y. et al. Comparison of the diagnostic accuracy of peroral video-cholangioscopic visual findings and cholangioscopy-guided forceps biopsy findings for indeterminate biliary lesions: a prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;77:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Osanai M, Itoi T, Igarashi Y. et al. Peroral video cholangioscopy to evaluate indeterminate bile duct lesions and preoperative mucosal cancerous extension: a prospective multicenter study. Endoscopy. 2013;45:635–642. doi: 10.1055/s-0032-1326631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Patel S N, Rosenkranz L, Hooks B. et al. Holmium-yttrium aluminum garnet laser lithotripsy in the treatment of biliary calculi using single-operator cholangioscopy: a multicenter experience (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79:344–348. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.07.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Piraka C, Shah R J, Awadallah N S. et al. Transpapillary cholangioscopy-directed lithotripsy in patients with difficult bile duct stones. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:1333–1338. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2007.05.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pohl J, Meves V C, Mayer G. et al. Prospective randomized comparison of short-access mother-baby cholangioscopy versus direct cholangioscopy with ultraslim gastroscopes. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013;78:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2013.04.177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramchandani M, Reddy D N, Gupta R. et al. Role of single-operator peroral cholangioscopy in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary lesions: a single-center, prospective study. Gastrointest Endosc. 2011;74:511–519. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.04.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sauer B G, Cerefice M, Swartz D C. et al. Safety and efficacy of laser lithotripsy for complicated biliary stones using direct choledochoscopy. Dig Dis Sci. 2013;58:253–256. doi: 10.1007/s10620-012-2359-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sepe P S, Berzin T M, Sanaka S. et al. Single-operator cholangioscopy for the extraction of cystic duct stones (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2012;75:206–210. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shah R J, Langer D A, Antillon M R. et al. Cholangioscopy and cholangioscopic forceps biopsy in patients with indeterminate pancreaticobiliary pathology. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;4:219–225. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(05)00979-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Siddiqui A A Mehendiratta V Jackson W et al. Identification of cholangiocarcinoma by using the Spyglass Spyscope system for peroral cholangioscopy and biopsy collection Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 201210466–471.; quiz e48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tischendorf J J, Kruger M, Trautwein C. et al. Cholangioscopic characterization of dominant bile duct stenoses in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis. [Erratum appears in Endoscopy 2006; 38: 852] Endoscopy. 2006;38:665–669. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-925257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsuyuguchi T, Saisho H, Ishihara T. et al. Long-term follow-up after treatment of Mirizzi syndrome by peroral cholangioscopy. Gastrointest Endosc. 2000;52:639–644. doi: 10.1067/mge.2000.108971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tsuyuguchi T, Sakai Y, Sugiyama H. et al. Long-term follow-up after peroral cholangioscopy-directed lithotripsy in patients with difficult bile duct stones, including Mirizzi syndrome: an analysis of risk factors predicting stone recurrence. Surg Endosc. 2011;25:2179–2185. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1520-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Woo Y S, Lee J K, Oh S H. et al. Role of SpyGlass peroral cholangioscopy in the evaluation of indeterminate biliary lesions. Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59:2565–2570. doi: 10.1007/s10620-014-3171-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duval S, Tweedie R. Trim and fill: a simple funnel-plot-based method of testing and adjusting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Biometrics. 2000;56:455–463. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.2000.00455.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun X, Zhou Z, Tian J. et al. Is single-operator peroral cholangioscopy a useful tool for the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary lesion? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Navaneethan U, Hasan M K, Lourdusamy V. et al. Single-operator cholangioscopy and targeted biopsies in the diagnosis of indeterminate biliary strictures: a systematic review. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:79–87. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lubbe J, Arnelo U, Lundell L. et al. ERCP-guided cholangioscopy using a single-use system: nationwide register-based study of its use in clinical practice. Endoscopy. 2015;47:802–807. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andriulli A, Loperfido S, Napolitano G. et al. Incidence rates of post-ERCP complications: a systematic survey of prospective studies. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1781–1788. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01279.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]