Abstract

This study investigates the association between sterilization and socioeconomic status in comparative context, using data from the 2006–10 National Survey of Family Growth and the 2004–10 Generations and Gender Surveys. We first confirm that longstanding patterns of association between socioeconomic status and sterilization persist in the contemporary United States. Specifically, female sterilization is associated with economic disadvantage whereas male sterilization is associated with economic advantage. We next show that female sterilization is similarly associated with disadvantage in most study countries, whereas a positive association between socioeconomic advantage and male sterilization is largely unique to the United States. However, while basic demographic background factors such as early childbearing and parity can explain the observed associations in most study countries, a strong gendered association between sterilization and socioeconomic status remains in the U.S. and Belgium even when adjusting for these factors.

More than one-third of married and cohabiting female contraceptive users of reproductive age rely on sterilization for fertility control, making sterilization the most commonly practised method of contraception in the world (United Nations 2013). Among U.S. women using contraception, the share relying on female or male sterilization is a remarkable 47.3% of married women and 28.0% of cohabiting women (Jones et al. 2012). Although comparative information on contraceptive use is limited by inconsistent sampling and study designs, existing research suggests that levels of sterilization are similarly high in Oceanic countries such as Australia, but tend to be lower and more variable across Europe (Mosher and Jones 2010; United Nations 2013).

Sterilization is a cost-effective, highly effective, ‘forgettable’ method of contraception (Grimes 2009). Yet there are a number of reasons to closely monitor trends and differentials in reliance on sterilization for fertility control. For example, contraceptive sterilization must be considered permanent, as procedures are not necessarily reversible if childbearing preferences change. More than one-quarter of U.S. women with unreversed tubal ligations in 2006–10 reported that they desire a reversal of the procedure, with desire for reversal most common among economically disadvantaged women (Grady et al. 2013). Moreover, sterilization carries an ominous history of abuse in many countries across the globe. Recent media coverage has shed renewed light on the history of coerced and forced sterilization in the United States, which disproportionately affected poor women and women of colour (Stern 2005; Severson 2011). Other notable examples of countries with past histories of involuntary sterilization include Nazi Germany, the countries of Scandinavia, Canada, and more recently, India, the Czech Republic, and Slovakia (Broberg and Roll-Hansen 1996; Schoen 2005; Zampas and Lamačková 2011; Hansen and King 2013). Considered within this context, and given that contemporary long-acting reversible contraceptive methods can offer similar levels of protection against unintended pregnancy (Trussell 2011), the fact that female sterilization remains most common among socioeconomically disadvantaged women in the United States (Jones et al. 2012) requires careful investigation. Vasectomy, on the other hand, has long been most common among the most socioeconomically advantaged men in the United States (e.g., Bumpass 1987; Anderson et al. 2012). Reasons for these associations remain insufficiently understood, nor do we know the extent to which similar socioeconomic differentials in patterns of contraceptive sterilization are shared by other low-fertility countries.

We addressed three specific questions in this research. First, what is the place of sterilization in the contemporary contraceptive regimes of low-fertility countries? In addition to the United States, we focused on nine countries which gathered data on contraceptive use as part of the Generations and Gender Programme: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Georgia, Germany, Romania, and Russia. All nine are low-fertility countries, though with widely different contraceptive histories and contemporary contraceptive regimes offering a diverse comparative context. Second, do socioeconomic gradients in sterilization tend to follow a similar pattern across countries? Specifically, is an association between female sterilization and socioeconomic disadvantage, and an association between male sterilization and socioeconomic advantage, observed broadly across our study countries? Finally, can basic demographic background factors explain observed associations between sterilization and socioeconomic status? We aimed to rigorously describe patterns of sterilization, because social scientists too often jump to explaining phenomena which have not been first clearly described (see also Landale et al. 2010; Sweeney and Raley 2014). Yet we were also interested in whether a disproportionate reliance on sterilization among disadvantaged women is primarily an artefact of accelerated childbearing schedules, higher achieved parity, or less stable union histories. Throughout the research, we relied on data from female as well as male respondents to examine if results were sensitive to using female versus male reports of contraceptive use or women’s versus men’s background characteristics. Because of potential endogeneity between own education and reproductive outcomes, we also considered multiple indicators of socioeconomic status, including both a respondent’s own education level and that of his or her mother.

Background

Historical context of contraceptive sterilization

Use of voluntary sterilization for fertility control became widespread only during the second half of the twentieth century (Ross et al. 1986). In the United States and Australia, contraceptive sterilization increased mainly during the 1970s (Santow 1991; Chandra 1998). The common law system in these (and other) Anglophone countries generally did not restrict use of voluntary sterilization (EngenderHealth 2002). The civil law system in Continental Europe, conversely, has historically considered sterilization an offence involving serious bodily injury—unless stipulated otherwise. Contraceptive sterilization was formally legalized in the 1970s in Austria and West-Germany and in 2001 in France, yet—while commonplace—its legal status remains unclear in Belgium (EngenderHealth 2002). Although the ‘contraceptive revolution’ of the 1960s and 1970s resulted in high contraceptive prevalence and nearly universal use of modern methods (Frejka 2008), use of sterilization in these countries tends to be lower and more variable than in the United States and Australia (Mosher and Jones 2010; United Nations 2013).

Levels of sterilization have historically been even lower in the countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (EngenderHealth 2002; Serbanescu et al. 2005). The Soviet Union became the first country in the region to legalize abortion in 1920, and abortion became freely available before the introduction of modern contraceptives in most countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union (David and Skilogianis 1999; Serbanescu et al. 2010). Combined use of withdrawal and abortion was thus established in the region well before the contraceptive revolution got under way, after the collapse of the authoritarian regimes (Westoff 2005; Frejka 2008). Romania is a peculiar exception, as it was characterized by an exceptionally strict pronatalist policy (Serbanescu et al. 1995, p. 76), which in practice prohibited nearly all use of abortion and modern contraceptives (including contraceptive sterilization) until the revolution of 1989. In Russia and Georgia, contraceptive sterilization became legal shortly after the 1991 dissolution of the Soviet Union, whereas the legal status of sterilization remains unclear in Bulgaria (EngenderHealth 2002).

Variability in contemporary sterilization patterns

Differences in study and sampling designs limit the utility of published results from individual country studies for drawing comparative conclusions about contemporary contraceptive use patterns (Bachrach et al. 2012). For example, the United Nations’ ‘World Contraceptive Use’ series—among the most widely used international resources on contraceptive use patterns—draws on individual country studies which vary in period of data collection, age limitations placed on samples, and union status of women included. As shown in Table 1, some country samples include all women at risk of pregnancy, regardless of union status, whereas others are limited to married or cohabiting women or include married women only. Some country samples are limited to women ages 15–44, whereas others include relatively older women and/or exclude relatively younger women.

Table 1.

The prevalence of contraceptive sterilization in 10 countries, various years, 1991–2008

| Country | Sample | Prevalence of sterilization

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | ||

| Australia | 2005 HILDA, women aged 18–44 ‘at risk of pregnancy,’ regardless of marital / union status | 6.6 % | 9.3 % |

| Austria | 1995–96 FFS, women in marriage or union aged 20–49 | N.A. | 0.5 % |

| Belgium | 1991–92 FFS, Flemish women in marriage or union aged 21–391 | 10.9 % | 7.0 % |

| Bulgaria2 | 1997–98 FFS, women aged 20–44 | N.A. | N.A. |

| France3 | 1994 FFS, women in marriage or union aged 20–49 | 8.0 % | N.A. |

| Georgia | 2005 RHS, married women aged 15–44 | 2.2 % | 0.0 % |

| Germany | 1992 FFS, women in marriage or union aged 20–39 | 5.5 % | 0.5 % |

| Romania | 2004 RHS, women in marriage or union aged 15–44 | 2.8 % | N.A. |

| Russia2 | 2007 Parents and Children, Men and Women in Family and Society, women aged < 50 | N.A. | N.A. |

| U.S.A. | 2006–08 NSFG, married women aged 15–44 | 23.6 % | 12.7 % |

Includes some cases of sterilization for non-contraceptive reasons.

The UN Report does not include estimates of female or male sterilization for Bulgaria or Russia. Serbanescu and colleagues (2005) do offer estimates for female sterilization in Bulgaria (0.0 % of women in marriage or union aged 15–44, 1997–98 DHS and RHS data), and in three urban areas in Russia (2.0 % of women in marriage or union aged 15–44, 1999 DHS and RHS data).

Bajos and colleagues (2012) reported a similarly low prevalence of sterilization for metropolitan France in 2010 (< 5 % of all sexually-active women not seeking pregnancy use male or female method—combined into a single category).

Notes: HILDA = Household, Income, and Labour Dynamics in Australia; RHS = Reproductive Health Survey; FFS = Fertility and Family Survey; DHS = Demographic Health Survey; NSFG = National Survey of Family Growth.

Source: United Nations ‘World Contraceptive Use 2012’ report.

These concerns aside, Table 1 suggests that recent levels of contraceptive sterilization are somewhat lower in Australia and Belgium than the United States, and considerably lower than the United States in our other study countries. Levels of sterilization appear especially low in the countries of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union. In addition, the prevalence of female sterilization considerably outweighs that of male sterilization in the United States (Chandra 1998; Jones et al. 2012; Bertotti 2013). This imbalance in the use of female versus male sterilization has long puzzled social scientists (e.g., Bumpass et al. 2000), as vasectomy has many advantages over tubal ligation; it is simpler, more effective, less often regretted, more economical, and has lower rates of minor and major complications (Rind 1989; Shih et al. 2011). Table 1 suggests that the contemporary dominance of female over male sterilization in the United States also extends to many of our other study countries, with the exception of Australia.

Although the ‘World Contraceptive Use’ series (and similar compilations of individual country studies) offer an important resource to researchers, policymakers, and clinicians, they lack the standardization that can be achieved when comparisons are made within the common framework of a single study. The recent release of standardized data on contraceptive use provides a unique opportunity to overcome problems of comparability and update our knowledge of the place of sterilization in contemporary contraceptive regimes of low-fertility countries. This could be important in light of changes in education, gender roles, and fertility, such as the reversal of the gender gap in education (Buchmann and DiPrete 2008) and changes in the level and timing of childbearing (Adserà 2004), as these changes may have profoundly affected contraceptive patterns in recent decades. In addition, several countries have undergone considerable societal transformations during the past decades (e.g., the countries of the former Soviet Union), which have affected the availability and legal status of contraceptives.

The perplexing links between sterilization and (dis)advantage

Dramatic growth in the prevalence of contraceptive sterilization in the United States in the 1970s signalled a profound change in family planning attitudes and practices (Bumpass and Presser 1972; Bumpass 1987). At the same time, it did not substantially alter the links between contraceptive sterilization and socioeconomic status. U.S. studies since the mid-twentieth century have almost unanimously reported a strong negative association between socioeconomic status and female contraceptive sterilization but a strong positive association between socioeconomic status and male contraceptive sterilization (Bumpass and Presser 1972; Presser and Bumpass 1972; Shapiro et al. 1983; Philliber and Philliber 1985; Chandra 1998; Bumpass et al. 2000; Godecker et al. 2001; Borrero et al. 2009; Chan and Westhoff 2010; Anderson et al. 2012; Bertotti 2013).

Surprisingly little is known about the socioeconomic patterning of sterilization in other low-fertility countries, because the limited studies in Australia and Europe on this topic differ in time period considered, sample design, and analytic approach. Moreover, most studies examining the links with socioeconomic status have failed to make the distinction between female and male sterilization, often combining the two methods together in a single ‘sterilization’ category. For example, studies report a negative association between women’s education and the likelihood of relying on either male or female sterilization (combined into a single category) for Australia in the mid-2000s (Gray and McDonald 2010), and for France, Great Britain, Spain and West-Germany in the mid-1980s (Riphagen and Lehert 1989). Lodewijckx (2000, 2002) reported the odds for female or male sterilization (again, combined into a single category) to be lowest among couples where at least one partner had completed higher education in Northern Belgium (Flanders) in the mid-1990s. Other studies have taken a similar approach to the analysis of sterilization in a number of other countries, including Georgia, Italy, and Sweden (Oddens 1996; Oddens and Milsom 1996; Serbanescu et al. 2000). Distinguishing male from female sterilization seems important, however, particularly given findings of very different associations between these two procedures and socioeconomic status in the United States, as described above.

Only a handful of recent studies of Europe or Australia differentiate between female and male sterilization when examining the links with socioeconomic status. In their analyses of women at risk of unintended pregnancy in early-1990s Great Britain and Germany, Oddens and colleagues report a negative relationship between women’s education and both female sterilization and male sterilization (considered as separate outcomes) (Oddens et al. 1994a,b; Oddens and Lehert 1997). In more recent studies of early-2000s Australia, Richters and colleagues (2003) report highly educated women to be least likely to rely on female sterilization, but they found no significant association with male sterilization. Yusuf and Siedlecky (2007), in contrast, report highly educated women to be least likely to rely on female sterilization and male sterilization (again, considered as separate outcomes), although the association with male sterilization was non-linear.

The role of demographic background factors?

Even in the United States, where the most attention has been paid to socioeconomic gradients in contraceptive sterilization, surprisingly little is known about whether these socioeconomic gradients are an artefact of socioeconomic differentials in demographic background factors, or whether they result from the broader context of contraceptive practices and policies. A number of demographic background factors are associated with the likelihood of sterilization, namely parity, early childbearing, union status, and union history. These background factors could mediate the association between socioeconomic status and sterilization.

Early childbearing is positively associated with a woman’s likelihood of sterilization (Chandra 1998). This has been connected to the length of a woman’s reproductive lifespan during which pregnancy must be avoided (Bumpass 1987) and its association with parity of the last wanted birth (Bumpass et al. 2000). A particularly strong association with sterilization has been noted for parity (Bumpass et al. 2000; Borrero et al. 2007), with the prevalence of both male and female sterilization generally increasing with higher parity (Bean et al. 1987; Bumpass 1987; Forste et al. 1995; Chandra 1998; Bumpass et al. 2000; Godecker et al. 2001; Anderson et al. 2010, 2012).

A number of studies also investigate the association between union status and contraceptive sterilization. Stable partnerships are generally expected to increase the attractiveness of sterilization, as individuals—especially women—are thought less motivated to maintain the potential for childbearing with a future partner (Eeckhaut 2015). In line with this, research has found that being unmarried is associated with a lower risk of sterilization for men, whereas being never-married single—but not being in a cohabitation—is associated with a lower risk of sterilization for women (Godecker et al. 2001; Eeckhaut 2015). Mixed results have been reported for union history, however, as Barone and colleagues (2004) found separated and divorced men to be underrepresented in their sample of vasectomized men, whereas Bumpass and colleagues (2000) found husband’s prior divorce to be positively associated with the likelihood of sterilization for men and women. Wife’s prior divorce appears to be negatively associated with the likelihood of male sterilization, but matters little for a woman’s own risk of sterilization (Bumpass et al. 2000).

Despite these documented associations between contraceptive sterilization and parity, early childbearing, union status, and union history, only a handful of studies consider the contribution of such demographic background factors to observed socioeconomic gradients in contraceptive use patterns. In the United States, limited evidence suggests that socioeconomic differentials in parity contribute to, but do not fully explain, associations between the prevalence of surgical sterilization and education or income at the time of interview (e.g., Chandra 1998; Eisenberg et al. 2009; Anderson et al. 2012). In Australia, Gray and McDonald (2010) found the negative link between a woman’s education and her reliance on contraceptive sterilization (male or female methods, combined) to become non-significant when adding controls for factors such as parity and relationship status. In Northern Belgium (Flanders), Lodewijckx (2002) found that relatively lower levels of sterilization (again, male or female methods combined) among couples where at least one partner had completed higher education persist even after controlling for background factors such as parity and age at last birth. In short, additional research is sorely needed, both in the United States and abroad, on the demographic underpinnings of socioeconomic gradients in male and female sterilization.

The current research

Taken together, results from prior studies suggest a great potential for comparative research to shed fresh light on socioeconomic differentials in sterilization. Using recently released data on contraceptive use, we considered socioeconomic differentials in contraceptive sterilization in ten low-fertility countries. We first investigated the overall place of sterilization in the contemporary contraceptive regimes of our study countries. We next investigated if an association between female sterilization and socioeconomic disadvantage, and an association between male sterilization and socioeconomic advantage, existed broadly across our study countries. Finally, we investigated whether associations between contraceptive sterilization and socioeconomic status can be explained by socioeconomic differentials in basic demographic background factors such as parity, early childbearing, union status, and union history. Throughout the research, we considered results from both female and male samples. Previous sterilization research has relied mainly on female samples or has limited samples to men who are currently married (e.g., Anderson et al. 2010, 2012). Including male samples better allows us to also examine the link between, for example, male sterilization and men’s own education level. Finally, to address concerns about potential endogeneity between socioeconomic standing and reproductive outcomes, we considered multiple measures of socioeconomic status, including respondent’s own education as well as the education completed by the respondent’s mother.

Data and methods

Data

Data for this study were drawn from the 2006–10 National Survey of Family Growth (NSFG) and the Generations and Gender Programme (GGP, 2004–10). The NSFG and GGP are particularly appropriate for the current project because recent and detailed information is gathered on contraceptive method use, as well as key background factors such as education, parity, age at first birth, union histories, race/ethnicity (in the NSFG), and nativity.

The NSFG data are representative of the U.S. civilian non-institutionalized population ages 15–44 when properly weighted, and include oversamples of respondents who are black or Hispanic. Face-to-face interviews were conducted with a total of 12,279 women and 10,403 men. Response rates in the 2006–10 NSFG were 75% for men and 78% for women (Martinez et al. 2012). All analyses and descriptive statistics were adjusted for the NSFG’s complex sample design.

The GGP is a cross-national, comparative, multidisciplinary, retrospective and prospective study of the dynamics of family relationships in contemporary industrialized countries (United Nations 2005). Face-to-face interviews were conducted in 19 countries with an average of 9,000 respondents per country, but only nine countries gathered data on contraceptive method use: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, France, Georgia, Germany, Romania, and Russia. The survey is considered to be representative of the 18–79 year old resident population in each participating country. Analyses and descriptive statistics based on GGP data were also adjusted using sampling weights. Response rates in the GGP ranged from 41.8% in Belgium to 97.0% in Romania.

We placed a number of common restrictions on our analytic samples for the current study. Information on contraceptive use is provided in the harmonized GGP data only for individuals in marriages, cohabiting unions, or other ‘intimate partnerships.’ Because of concerns about variability across individual respondents and across GGP countries in the meaning of ‘intimate partnerships’ (e.g., do intimate partnerships refer to any ongoing sexual partnership or only more committed unions?), and to enhance comparability between the GGP and NSFG analyses, we limited the analytic samples to respondents using contraception who are married or cohabiting with an opposite-sex partner. To increase comparability across our data sets, we did not consider respondents who are pregnant, who have a partner who is pregnant, or who indicate that it would not be physically possible for themselves or their partner to have a child of their own for reasons other than surgical sterilization. Finally, because of the NSFG’s upper age limit, and the fact that sterilization is universally rare at younger ages within our study countries, we limited the analytic samples to respondents aged 25–44.

Variables

In comparative research such as ours, it is essential to construct measures in a similar way across study samples. Our dependent variable in this research was current contraceptive use status (see Table 2). We distinguished among couples relying on female sterilization, male sterilization, highly-effective reversible (HER) methods (e.g., hormonal pill, patch, ring, injection, and IUD), male condoms, or other less effective methods. In both the GGP and NSFG data, we first identified respondents who are themselves surgically sterilized, or whose spouse/co-residential partner is surgically sterilized, at the time of the survey. For non-sterilized couples, we then considered reports of ‘current’ contraceptive use gathered in both sets of surveys. In the GGP, this was based on a question regarding whether the respondent or his/her partner are using one or more specific contraceptive methods to prevent pregnancy ‘at this time.’ In the NSFG, we relied on reports of contraceptive use at last sex in the past three months. In cases where multiple methods are reported, we selected the most effective method used, prioritizing methods in the following order based on documented differentials in failure rates (e.g., Trussell 2011): sterilization, highly-effective reversible methods, condoms, other less effective methods. The small number of couples in which both partners were reported being sterilized were omitted from the analysis.

Table 2.

Number of respondents aged 25–44 in a heterosexual cohabitation or marriage who are currently using contraception and percent distribution by method in ten low-fertility countries, various years 2004–10: Female (F) and male samples (M)

| Reference period | Sample | N | Using any method | Sterilization

|

HER method1 | Condom | Other less effective method2 | Summary measures

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female | Male | % of total using sterilization | Of sterilized, % using female sterilization | ||||||||

| U.S.A. | 2006–10 | F | 3,406 | 100 | 31.8 | 16.3 | 28.5 | 13.8 | 9.6 | 48.1 | 66.1 |

| M | 2,171 | 100 | 27.0 | 16.0 | 32.1 | 15.8 | 9.0 | 43.0 | 62.8 | ||

| Australia | 2005–06 | F | 660 | 100 | 16.0 | 23.6 | 38.1 | 19.1 | 3.2 | 39.6 | 40.4 |

| M | 475 | 100 | 11.0 | 17.3 | 43.6 | 25.3 | 2.8 | 28.3 | 38.8 | ||

| Belgium | 2008–10 | F | 715 | 100 | 8.3 | 9.5 | 71.1 | 6.3 | 4.9 | 17.7 | 46.7 |

| M | 579 | 100 | 7.4 | 7.5 | 70.0 | 10.2 | 4.9 | 14.9 | 49.7 | ||

| Austria | 2008–09 | F | 1,266 | 100 | 8.9 | 7.7 | 59.2 | 19.5 | 4.7 | 16.6 | 53.6 |

| M | 691 | 100 | 6.7 | 6.9 | 53.8 | 28.1 | 4.6 | 13.6 | 49.2 | ||

| Germany | 2005 | F | 989 | 100 | 9.0 | 3.7 | 71.9 | 8.1 | 7.3 | 12.7 | 71.0 |

| M | 590 | 100 | 8.2 | 3.8 | 71.8 | 9.8 | 6.4 | 12.0 | 68.2 | ||

| Georgia | 2006 | F | 781 | 100 | 10.9 | 0.3 | 42.7 | 13.8 | 32.5 | 11.1 | 97.6 |

| M | 423 | 100 | 10.3 | 0.7 | 44.6 | 25.1 | 19.3 | 11.0 | 93.9 | ||

| France | 2005 | F | 1,067 | 100 | 4.8 | 0.9 | 84.2 | 7.5 | 2.6 | 5.7 | 84.5 |

| M | 776 | 100 | 3.7 | 0.1 | 85.1 | 8.5 | 2.6 | 3.8 | 97.4 | ||

| Russia | 2004 | F | 1,134 | 100 | 5.5 | 0.0 | 48.9 | 23.1 | 22.5 | 5.5 | 100.0 |

| M | 840 | 100 | 3.8 | 0.1 | 46.1 | 31.2 | 18.8 | 3.9 | 97.4 | ||

| Romania | 2005 | F | 1,217 | 100 | 5.0 | 0.1 | 40.5 | 26.8 | 27.6 | 5.1 | 98.0 |

| M | 1,152 | 100 | 3.1 | 0.3 | 42.1 | 27.9 | 26.6 | 3.4 | 92.6 | ||

| Bulgaria | 2004 | F | 1,812 | 100 | 3.4 | 0.1 | 28.4 | 25.2 | 42.9 | 3.5 | 96.9 |

| M | 1,076 | 100 | 1.1 | 0.0 | 25.2 | 32.7 | 41.0 | 1.1 | 100.0 | ||

Highly-effective reversible (HER) contraceptives include hormonal pill, patch, ring, injection, and IUD (only in Belgium this also includes the morning-after pill).

Other less-effective contraception includes methods such as periodic abstinence, morning-after pill (all but Belgium), diaphragm, foam, cream, jelly, suppository, withdrawal, and Persona (GGP countries only).

Notes: Countries listed in order of overall total prevalence of sterilization.

Source: 2006–10 NSFG and 2004–10 GGP.

Our focal independent variable is educational attainment. To again maximize comparability, we based our measure of education on the 1997 International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED97) system. We grouped respondents into the following three categories: (1) less than high school education, (2) high school/post-secondary non-tertiary/some college, and (3) tertiary/Bachelor’s degree.

We also considered a number of other background measures which may be associated with contraceptive use. These included education of the respondent’s mother (less than high school education; high school/post-secondary non-tertiary/some college; tertiary/Bachelor’s degree), respondent’s age (25–29 years; 30–34 years; 35–39 years; 40–44 years), respondent’s current union status (married; cohabiting), respondent’s union history (no previous co-residential union; previous cohabitation(s) only; any previous marriage), respondent’s parity (0; 1; 2; 3+), respondent’s early childbearing (had a first birth between ages 15–19 years; first birth between ages 20–24 years; no first birth before age 25), and whether the respondent was born in the current country of residence. Because of the well-documented importance of racial and ethnic background to contraceptive use patterns in the United States (Mosher and Jones 2010), we also added a control for race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white; non-Hispanic black; Hispanic; other) to the regression analyses for this country. Descriptive statistics for key independent variables are displayed in Appendix 1.

Analysis technique

Our analysis proceeded in two stages. First, we described the place of sterilization in the contraceptive regimes of our study countries, as well as the associations between education and patterns of female and male sterilization. We considered results based on female as well as male samples in each country, and verified that conclusions are broadly robust to whether socioeconomic status is operationalized by own education or mother’s education. Here, and throughout the analysis, own education and mother’s education refer to characteristics of the main respondent.

Second, to better understand if demographic background factors can explain observed associations between education and sterilization patterns, we estimated a series of country-specific regression models. For countries with meaningful levels of male sterilization (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Germany, and the United States), contraceptive use was analysed using multinomial logistic regression and the outcome categories of female sterilization, male sterilization, a reversible method:

| (1) |

| (2) |

where Pij represents the probability that respondent i is situated in outcome category j of the dependent variable (i.e., ‘female sterilization,’ ‘male sterilization,’ or ‘use of any reversible method’), Өij represents the log odds that respondent i is situated in this category j, and k indexes the independent variables included in the model. For countries with trivial levels of male sterilization (<1% of contraceptors, including Bulgaria, France, Georgia, Romania, and Russia), we considered only those cases relying on female sterilization or a reversible method and instead rely on binary logistic regression:

| (3) |

| (4) |

where Pij represents the probability that respondent i is situated in the outcome category ‘using a reversible method’ of the dependent variable, Өij represents the log odds that respondent i is situated in this category j, and k indexes the independent variables included in the model.

For both sets of models, we first regressed contraceptive use on education, age, and nativity (Model 1). We then added controls for current union status, union history, parity, and early childbearing to these baseline models (Model 2). Because of the importance of racial and ethnic background to contraceptive use patterns in the United States (Mosher and Jones 2010), we also adjusted for race/ethnicity in all models for this country, as previously noted.

Results

The prevalence of sterilization

We began by broadly considering the place of sterilization in the contemporary contraceptive regimes of our study countries. As shown in Table 2, overall levels of sterilization are highest in the United States and Australia. Moderate levels of sterilization are observed in Belgium, Austria, Germany, and Georgia. Lowest levels of sterilization are observed in France, Russia, Romania, and Bulgaria. Interestingly, reported levels of both female and male sterilization are generally lower in the male than female samples. This difference is particularly apparent for reports of female sterilization in the United States and Australia. Limiting the male sample by the age of the partner (e.g., male respondents with female partners ages 25–44 years) explains some but not all of these differences (results available upon request).

Our study countries also vary considerably in the prevalence of female versus male sterilization. The prevalence of male sterilization is negligible (below 1%) in Georgia, France, Russia, Romania, and Bulgaria. Consistent with previous findings presented in Table 1, female sterilization is much more common than male sterilization in Germany and the United States. Only Australia, Belgium, and Austria do not conform to the widespread dominance of female sterilization. Male sterilization is more common than female sterilization in Australia, and the two sterilization methods are roughly equally prevalent in Austria and Belgium.

The perplexing links between sterilization and (dis)advantage

We next considered how patterns of sterilization vary across educational groups in our ten study countries. Consistent with prior research, data from the female and male samples of the 2006–10 NSFG indicate a strong negative association between female sterilization and women’s and men’s education, and a strong positive association between male sterilization and women’s and men’s education for the United States (Table 3, top panel). We see a largely similar pattern of results when socioeconomic status is operationalized as mother’s education rather than the primary respondent’s own education (Table 3, bottom panel).

Table 3.

Percentage of married or cohabiting contraceptors aged 25–44 who are relying on sterilization, by own education and by mother’s education in ten low-fertility countries, various years 2004–10: Female (F) and male samples (M)

| U.S.A. | Australia | Belgium | Austria | Germany | Georgia | France | Russia | Romania | Bulgaria | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | |

| By own education | ||||||||||||||||||||

| % relying on female sterilization | ||||||||||||||||||||

| < High school | 53.6 | 42.7 | 25.1 | 12.8 | 20.0 | 14.3 | 19.6 | 13.7 | 8.5 | 11.8 | 19.2 | 33.1 | 12.3 | 5.9 | 9.4 | 7.9 | 4.4 | 1.9 | 4.8 | 2.0 |

| High school / Some college | 36.3 | 31.1 | 12.9 | 12.1 | 11.4 | 8.1 | 8.3 | 6.7 | 9.9 | 9.5 | 9.9 | 9.9 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 6.3 | 4.1 | 5.1 | 3.7 | 3.5 | 0.9 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 14.8 | 9.7 | 11.7 | 9.0 | 3.2 | 4.3 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 6.6 | 4.0 | 11.2 | 8.4 | 2.4 | 2.7 | 4.5 | 2.4 | 5.7 | 1.9 | 2.6 | 1.4 |

| pCh2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||||

| % relying on male sterilization | ||||||||||||||||||||

| < High school | 6.5 | 5.6 | 30.7 | 24.2 | 7.4 | 2.3 | 6.3 | 2.6 | 1.7 | 2.1 | ||||||||||

| High school / Some college | 16.8 | 15.5 | 26.9 | 20.4 | 12.0 | 12.2 | 8.6 | 7.7 | 4.5 | 3.2 | ||||||||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 20.0 | 23.8 | 16.4 | 10.8 | 8.4 | 5.3 | 5.7 | 5.5 | 2.2 | 5.9 | ||||||||||

| pCh2 | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||||||

| By mother’s education | ||||||||||||||||||||

| % relying on female sterilization | ||||||||||||||||||||

| < High school | 43.5 | 40.6 | 19.7 | 11.8 | 9.5 | 10.4 | 12.6 | 6.6 | 9.9 | 12.8 | 15.9 | 12.6 | 5.3 | 5.2 | 9.2 | 4.4 | 4.8 | 3.9 | 5.0 | 1.7 |

| High school / Some college | 31.5 | 26.1 | 12.3 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 3.2 | 5.5 | 6.1 | 8.7 | 5.7 | 9.6 | 10.4 | 4.4 | 0.5 | 3.6 | 2.7 | 4.8 | 1.1 | 2.4 | 0.2 |

| Bachelor’s degree | 15.6 | 9.8 | 8.2 | 4.8 | 4.2 | 5.4 | 0.0 | 2.4 | 7.6 | 2.5 | 7.9 | 5.4 | 1.0 | 2.8 | 1.9 | 2.4 | 7.2 | 0.0 | 1.1 | 1.1 |

| pCh2 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | ||||||||||

| % relying on male sterilization | ||||||||||||||||||||

| < High school | 10.6 | 6.6 | 26.1 | 20.6 | 11.5 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 6.8 | 4.2 | 4.2 | ||||||||||

| High school / Some college | 18.2 | 20.1 | 22.6 | 16.2 | 9.5 | 8.9 | 8.2 | 8.4 | 3.4 | 4.0 | ||||||||||

| Bachelor’s degree | 18.7 | 15.2 | 13.6 | 11.2 | 4.0 | 4.6 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 4.6 | 0.0 | ||||||||||

| pCh2 | * | * | * | |||||||||||||||||

Notes: Countries listed in order of overall total prevalence of sterilization. ‘Own education’ refers to the attainment of the primary respondent (e.g., female partner for the female sample). In Australia, the variable mother’s education contains an additional category ‘Other.’ pCh2 = Results of Chi-squared test of null hypothesis that there is no association between education and sterilization (* p < 0.05).

Source: As for Table 2.

We next investigated whether similar gendered associations between sterilization and educational attainment characterize our other study countries. First turning to female sterilization, we note that a general association between educational disadvantage and reliance on female sterilization exists in nine of our ten study countries (see Table 3). Only in the case of Romania are women with less than high school education not more likely than those with a Bachelor’s degree to rely on female sterilization. The overall nature of the associations between female sterilization and socioeconomic status remains largely consistent when gradients are considered with respect to men’s education or mother’s education, rather than women’s education.

We next turned our attention to patterns of male sterilization. Data presented in Table 3 indicate that, among the countries with meaningful levels of male sterilization, only Australia displays a clear monotonic relationship between education and rates of male sterilization. But here it is the women and men with less than high school education who are most likely to rely on male sterilization. In Germany, we see some evidence of a positive educational gradient in male sterilization when relying on the male sample and men’s own education, but no similar pattern when results are based on the female sample or on mother’s education in either sample. In the other countries with meaningful levels of male sterilization, we observe a generally similar pattern of associations when looking at estimates based on men’s education or mother’s education, rather than women’s education.

The role of demographic background factors

In the final stage of our analysis, we turned to regression models to determine if the previously described bivariate associations between education and sterilization (see Table 4) are explained by basic demographic background factors. We focused on four basic demographic background factors that could mediate the association between socioeconomic status and sterilization, including parity, early childbearing, union status, and union history.

Table 4.

Exponentiated coefficients for own education (< high school = ref. category) in multinomial or binary logistic regression analyses of contraceptive use (female sterilization = ref. category) in ten low-fertility countries, various years 2004–10: Female (F) and male samples (M)

| United States | Australia | Belgium | Austria | Germany | Georgia | France | Russia | Romania | Bulgaria | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | M | F | F | F | F | F | |

| Model 1: Education, age, nativity status,1 race2 | |||||||||||||||

| Male sterilization | |||||||||||||||

| High school / some college | 3.51 | 2.90 | 1.87 | 1.10 | 3.04 | 9.35 | 3.06 | 2.77 | 2.52 | 1.07 | |||||

| Bachelor’s | 9.12 | 13.17 | 1.23 | 0.71 | 7.66 | 7.76 | 4.84 | 2.55 | 1.81 | 4.51 | |||||

| Reversible method | |||||||||||||||

| High school / some college | 2.13 | 1.66 | 2.14 | 1.08 | 2.36 | 1.19 | 2.41 | 1.79 | 1.09 | 2.10 | 2.98 | 2.20 | 2.61 | 0.92 | 1.44 |

| Bachelor’s | 7.34 | 7.57 | 2.65 | 1.55 | 9.00 | 3.06 | 6.08 | 2.50 | 1.95 | 5.89 | 2.36 | 3.25 | 3.61 | 0.81 | 1.84 |

| pEduc | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |||||||

| Model 2: Model 1 + age, nativity status,1 race,2 parity,3 early childbearing,34 current union status, union history56 | |||||||||||||||

| Male sterilization | |||||||||||||||

| High school / some college | 2.30 | 2.39 | 1.70 | 0.85 | 2.24 | 9.87 | 2.28 | 2.66 | 1.61 | 0.96 | |||||

| Bachelor’s | 3.65 | 8.51 | 0.86 | 0.58 | 3.67 | 6.34 | 2.79 | 2.28 | 0.83 | 3.45 | |||||

| Reversible method | |||||||||||||||

| High school / some college | 1.22 | 1.44 | 1.64 | 1.08 | 1.65 | 1.14 | 1.52 | 1.43 | 0.82 | 1.71 | 2.72 | 2.00 | 2.09 | 0.78 | 1.62 |

| Bachelor’s | 2.23 | 5.10 | 1.40 | 1.15 | 3.91 | 2.67 | 2.82 | 1.83 | 1.13 | 4.57 | 2.03 | 2.55 | 2.51 | 0.69 | 1.96 |

| pEduc | * | * | * | * | |||||||||||

| N | 3,406 | 2,171 | 660 | 475 | 715 | 579 | 1,266 | 691 | 989 | 590 | 779 | 1,060 | 1,134 | 1,216 | 1,810 |

In the analyses for Bulgaria, Georgia, and Romania, the variable nativity is omitted due to a lack of variation (nearly all respondents were native-born).

The variable race is included only in the analyses for the United States.

Due to data limitations, measures of parity and early childbearing refer to both biological and adoptive children in the Australian GGP.

In the analyses of the male samples (M) for Australia, Austria, Belgium, and Germany, the categories ‘15–19 years’ and ‘20–24 years’ of the variable early childbearing are combined due to small representation in the former category.

In the analyses for Bulgaria, Georgia, and Romania, the categories ‘previous cohabitation’ and ‘previous marriage’ of the variable union history are combined due to small representation in the former category.

In the analyses for Belgium, the variable union history includes an additional category ‘Missing.’

Notes: Countries listed in order of overall total prevalence of sterilization. As described in the text, multinomial logistic regression models (female sterilization vs. male sterilization, reversible method) are estimated for the United States, Australia, Belgium, Austria, and Germany. Binary logistic regression models (female sterilization vs. reversible method) are estimated for Georgia, Russia, France, Romania, and Bulgaria. Boldface indicates coefficient differs significantly from zero, at p < 0.05 level. pEduc = Results of Wald test of null hypothesis that full set of education coefficients in a particular model are jointly equal to zero (* p < 0.05).

Source: As for Table 2.

First, we regressed contraceptive use on education, age, nativity, and, only for the United States, race/ethnicity (Model 1). Among countries with a significant overall association between education and contraceptive use we note that education is associated with differences in the odds of male sterilization versus female sterilization in three countries: the United States, Belgium, and Austria (female data only). In all three countries, respondents with a high school level of education, and—in general even more so—those with a Bachelor’s degree, are more likely to rely on male versus female sterilization than respondents with less than high school education. We see a similar relationship between education and the odds of using a reversible method rather than female sterilization in the United States, Australia (female data only), Belgium, Austria (female data only), Georgia, and France. Again, results show a positive relationship between education and the likelihood of relying on a reversible method for contraception rather than female sterilization.

Next, we added controls for parity, early childbearing, current union status, and union history to our baseline models (Model 2). We find that these basic demographic background factors can largely explain the association between education and contraceptive use patterns in some countries (Australia, Austria, Georgia, and France) but not in others (United States and Belgium). More specifically, early childbearing can fully explain the association between education and contraceptive use patterns in all four countries (see Appendix 2, Model 3). In Australia and Georgia, the association can also be fully explained by parity (see Appendix 2, Model 2).

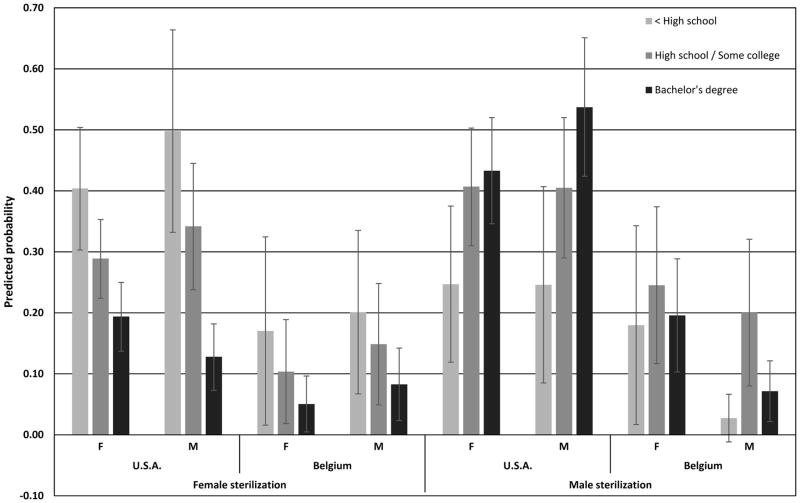

A strong association between sterilization and socioeconomic status remains in the United States, and to a lesser extent in Belgium, even once all controls are entered into the model. Figure 1 shows the predicted probabilities of relying on female sterilization or male sterilization, computed for (white) married contraceptive users aged 40–44 with two children who were born in the study country and had no early birth or previous co-residential partnership. These results illustrate that a strong relationship between the use of female sterilization and disadvantage persists in the United States. Our models also point to some remaining association between female sterilization and disadvantage in Belgium net of our control variables, although the confidence intervals displayed in Figure 1 overlap in the case of Belgium. The predicted probabilities of relying on male sterilization also reveal that a positive relationship remains in the United States after adjusting for these demographic background factors, whereas a non-linear relationship remains in Belgium.

Figure 1.

Predicted probabilities (and 95% confidence intervals) of relying on female or male sterilization for (white) married contraceptive users aged 40–44 with two children who were born in the study country and had no early birth or previous co-residential partnership: Female (F) and male (M) samples

Source: 2006–10 NSFG and 2008–10 GGP.

Conclusions and discussion

This study took a fresh look at the perplexing links between sterilization and socioeconomic status. We extended previous research in several ways. First, we took on a comparative perspective, gaining fresh insights by considering a diverse group of low-fertility countries. Next, we included both female and male samples, advancing the study of sterilization to its links with both women’s and men’s characteristics. Finally, we defined socioeconomic background according to mother’s education, in addition to respondent’s education, to account for the possibility of endogeneity between socioeconomic status and reproductive outcomes.

We addressed three broadly comparative questions in this research. First, what is the place of contraceptive sterilization in contemporary contraceptive regimes of our study countries? We showed that levels of sterilization vary widely across these low-fertility countries. The United States displayed the highest levels of sterilization, followed by Australia. Moderate levels of sterilization were found in Belgium, Austria, Germany, and Georgia. In these latter countries, married and cohabiting female contraceptors were most likely to rely on highly-effective reversible (HER) methods, such as pills and IUDs (see Table 2). Lower use of HER methods (particularly IUDs) in the United States and Australia (Eeckhaut, Sweeney, and Gipson 2014) may be related to the poor reputation and subsequent distrust of IUDs after reports of serious safety concerns with the Dalkon Shield IUD in the 1970s (Hubacher and Cheng 2004; Gray and McDonald 2010). As the Dalkon Shield was seldom used in Europe, the safety scare associated with this device likely had less of an impact on contraceptive use patterns in Europe (Sonfield 2007). Finally, lowest levels of sterilization were reported in the Eastern European and ex-Soviet countries (Bulgaria, Romania, and Russia—though not in Georgia), but also in France, where sterilization has been legal for contraceptive purposes only since 2001 (Bajos et al. 2012).

Variability in the contraceptive regimes of contemporary low-fertility countries is also reflected in the relative prevalence of female versus male sterilization. Whereas female sterilization dominates in France and in the Eastern European and ex-Soviet countries and, to a lesser extent, in the United States and Germany, male sterilization is more, or roughly equally common in Australia, Austria, and Belgium. Reasons for these sizeable differences in the prevalence of female versus male sterilization remain poorly understood, but are likely shaped by the broader context of sterilization practices and policies, including differences in the availability, accessibility, and affordability of female versus male sterilization services and information, social and cultural attitudes toward female versus male sterilization, as well as individuals’ and providers’ perceptions of female versus male methods. Additional research on the specific factors contributing to the relative prevalence of male versus female sterilization is sorely needed.

Our second research question focused on the gendered links between socioeconomic status and sterilization: Do socioeconomic gradients in sterilization tend to follow a similar pattern across low-fertility countries? We found that the U.S. association between female sterilization and disadvantage extends to other low-fertility countries, whereas the positive gradient in male sterilization was largely specific to the U.S. context.

Finally, we asked whether basic demographic background factors mediate observed associations between sterilization and socioeconomic status. In short, we found that differences in demographic background factors largely explain the differentials in female and male sterilization in Australia, Austria, Georgia, and France. Key factors linking education and sterilization in these countries include early childbearing and, to a lesser extent, parity. The central role of early childbearing suggests that less educated women in these countries rely more heavily on (female) sterilization because the period in the reproductive lifespan during which they have to avoid pregnancy tends to be longer than for women with higher levels of education (Bumpass 1987). Early childbearing may also matter because of its links with parity (Bumpass et al. 2000), especially in those countries (Australia and Georgia) in which parity independently accounts for the associations between education and sterilization.

Yet a clear association between socioeconomic status and sterilization persisted in the United States and Belgium, even after adjusting for these demographic background factors. We see clear educational patterns in female sterilization in both countries and male sterilization in the United States. In the United States, educational patterns are likely shaped by insurance practices, as research has shown that female sterilization is relatively common among women relying on Medicaid or without insurance (Bass and Warehime 2009; Anderson et al. 2012), whereas male sterilization is most common among men with private insurance or a health maintenance organization (HMO) plan (Barone et al. 2004; Anderson et al. 2012). Less is known about potential explanations for educational patterns of sterilization in Belgium. Recent work suggests that the initial costs of obtaining the birth control pill—the country’s most popular reversible method—are relatively high in Belgium as compared to its European neighbors (Bachrach et al. 2012). These costs may be relevant to consider, and may pose a greater barrier to pill use among the least educated. Yet the array of factors shaping contraceptive cost and access is complex (Donadio 2013). Educational groups may also differ in views regarding the safety of sterilization procedures, attitudes towards health care providers, or differences in attitudes of health care providers towards their more versus less well educated patients (Lodewijckx 2000, 2002). Individual preferences may also play a role, as educational attainment is positively associated with men’s willingness to share contraceptive responsibility—at least in the United States (Grady et al. 1996). Men who are more educated than their partners may also feel less of a need to protect their masculinity by avoiding a vasectomy (e.g., Bertotti 2013). Investigating these diverse explanations for sterilization differentials in the United States and Belgium will be an important direction for future research on this topic.

The results of the analysis allow for two additional conclusions. By including both female and male samples, we examined the possibility that patterns of sterilization may differ depending on whether we consider male versus female reports of contraceptive use or women’s versus men’s background characteristics. We find some evidence that overall reports of both male and female sterilization tend to be somewhat lower in data provided by men, and particularly so for Australia. The underlying reasons for these differences require further attention, as they were not fully explained by differences in the age composition of female partners in the female versus male samples. However, broader conclusions regarding socioeconomic differentials in sterilization are largely robust across the male and female samples. Our conclusions were also broadly robust to operationalization of socioeconomic status using own versus mother’s education.

These conclusions are based on recently available comparative data on contraceptive use, which offered a unique opportunity to overcome problems in terms of comparability. A challenge of the comparative perspective is the need for uniform samples. The uniformity of our samples was enhanced by restricting our focus to respondents in a heterosexual marriage or cohabitation, and dropping respondents in other ‘intimate partnerships.’ This approach avoided problems with variability across individual respondents and across GGP countries in the meaning of ‘intimate partnerships,’ and enhanced comparability between the GGP and NSFG analyses. Yet, it also limited the generalizability of our conclusions to individuals in co-residential relationships. This restriction needs to be kept in mind, especially when focusing on the U.S. context in which sterilization is relatively prevalent among never-married women (Jones et al. 2012). The generalizability of our findings is also limited to individuals using contraception. Possible reasons for not using contraception are diverse (e.g., cost of contraceptives, access to contraceptives, pregnancy wish, infertility, breastfeeding), and the relative importance of these reasons, as well as their links with education, may differ across countries. Excluding couples who are currently not using contraception avoided problems with variability across countries in the reasons underlying non-use of contraception, and enhanced the uniformity of our samples. Finally, as the GGP countries did not allow respondents to differentiate between surgical sterilization procedures undertaken for contraceptive versus other (medical) purposes, our measures of sterilization could include operations that occurred for non-contraceptive reasons. Yet individuals often have multiple motivations for surgical sterilization, blurring the distinction between procedures performed for medical versus contraceptive purposes (Rindfuss and Liao 1988). Moreover, sensitivity analyses for the U.S. data, which does allow for this distinction based on respondents’ retrospective reports, suggest that this issue did not affect our substantive conclusions.

As our focus was on aggregate comparisons among countries, we paid little attention to regional or racial and ethnic diversity within countries in the place and patterning of contraceptive sterilization. By examining patterns of sterilization cross-nationally, we aimed to provide a comparative perspective on patterns of contraceptive sterilization. Another part of the story, however, lies at the country-level, as regional or racial and ethnic diversity within countries is potentially substantial as well. For example, research in the United States has reported sizeable racial and ethnic differences in the patterning of sterilization (Mosher and Jones 2010; Bertotti 2013), whereas in countries such as Georgia and Romania, urban versus rural differences appear vital in determining contraceptive use patterns (Serbanescu et al. 1995, 2000). Mapping this diversity is essential to understanding the meaning of socioeconomic differentials in contraceptive sterilization, and the potential role of community-level resources and policy, especially in those countries in which socioeconomic differentials in sterilization are more than just the result of differences in demographic background factors between socioeconomic groups (e.g., the United States and Belgium). This will be an important direction for future research on this topic. In addition, we paid little attention to the role of individuals’ childbearing intentions for contraceptive decision-making. Future work may benefit from a careful examination of sterilization only among those who do not intend future births. Finally, as most research analysing nationally representative data on sterilization, we relied on a measure of socioeconomic status at the time of interview (i.e., education at the time of interview), despite the fact that sterilization in all cases occurred at some earlier point in time and early reproductive outcomes may contribute to socioeconomic standing later in life (e.g., Kane et al. 2013; Sweeney and Raley 2014). Future research could benefit from data collection efforts aimed at measuring respondent’s (and partner’s) characteristics at the time of sterilization—in addition to at the time of the interview—in nationally representative surveys on sterilization.

In conclusion, the current research sheds much-needed light on a side of the ‘contraceptive revolution’ which often remains overlooked: sterilization. Use of a comparative perspective both improves our understanding of broad patterns of contraceptive use among low-fertility countries and illuminates what may be more unique to the context of the United States. Too often social scientists rush to explain phenomena which have not been adequately described. This work provides a critical descriptive foundation for deepening our understanding of gender, social class, and contraceptive sterilization, and highlights a number of important questions for future research. What about the U.S. context can explain an apparently exceptional positive association between education and vasectomy? What factors, other than those considered here, can explain the persistent association between female sterilization and low education in the United States and Belgium? In addition to considering aggregate country-level differences in reproductive health policies, future work on contraceptive sterilization in the United States may gain useful leverage on these questions from careful attention to variability across states in policies relevant to contraceptive choice, including mandates for coverage of contraceptive devices and services by private insurance, state receipt of Medicaid waivers for family planning, and access by men as well as women to public funding for contraception more broadly defined.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Acknowledgements: A previous version of this paper was presented at the 2013 annual meeting of the Population Association of America. This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number F32–HD078037 to M. Eeckhaut and by the California Center for Population Research at UCLA, which receives core support (R24–HD041022) from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. Correspondence should be addressed to the first author.

References

- Adserà Alicia. Changing fertility rates in developed countries. The impact of labor market institutions. Journal of Population Economics. 2004;17(1):17–43. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson John E, Warner Lee, Jamieson Denise J, Kissin Dmitry M, Nangia Ajay K, Macaluso Maurizio. Contraceptive sterilization use among married men in the United States: Results from the male sample of the National Survey of Family Growth. Contraception. 2010;82(3):230–235. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson John E, Jamieson Denise J, Warner Lee, Kissin Dmitry M, Nangia Ajay K, Macaluso Maurizio. Contraceptive sterilization among married adults: National data on who chooses vasectomy and tubal sterilization. Contraception. 2012;85(6):552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bachrach Christine, Compernolle Lou P, Helfferich Cornelia, Lindahl Katarina, Van der Vlugt Ineke. [Accessed 14 November 2013];Unplanned Pregnancy and Abortion in the United States and Europe: Why So Different? 2012 http://www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/pdf/pubs/international-comparisons.pdf.

- Bajos Nathalie, Bohet Aline, Guen Mireille Le, Moreau Caroline the Fecond Survey Team. Contraception in France: New context, new practices? Population & Societies. 2012;492:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- Barone Mark A, Johnson Christopher H, Luick Melanie A, Teutonico Daria L, Magnani Robert J. Characteristics of men receiving vasectomies in the United States, 1998–1999. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2004;36(1):27–33. doi: 10.1363/psrh.36.27.04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bass Loretta E, Nicole Warehime M. Do health insurance and residence pattern the likelihood of tubal sterilization among American women? Population Research and Policy Review. 2009;28(2):237–249. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Williams Dorie G, Opitz Wolfgang, Burr Jeffrey A, Trent Katherine. Sociodemographic and marital heterogamy influences on the decision for voluntary sterilization. Journal of Marriage and Family. 1987;49(2):465–476. [Google Scholar]

- Bertotti Andrea M. Gendered divisions of fertility work: Socioeconomic predictors of female versus male sterilization. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2013;75(1):13–25. [Google Scholar]

- Borrero Sonya, Schwarz Eleanor B, Reeves Matthew F, Bost James E, Creinin Mitchell D, Ibrahim Said A. Race, insurance status, and tubal sterilization. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2007;109(1):94–100. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000249604.78234.d3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borrero Sonya, Moore Charity G, Qin Li, Schwarz Eleanor B, Akers Aletha, Creinin Mitchell D, Ibrahim Said A. Unintended pregnancy influences racial disparity in tubal sterilization rates. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 2009;25(2):122–128. doi: 10.1007/s11606-009-1197-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broberg Gunnar, Roll-Hansen Nils., editors. Eugenics and the Welfare State: Sterilization Policy in Denmark, Sweden, Norway, and Finland. East Lansing (MI): Michigan State University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Buchmann Claudia, DiPrete Tom A. The growing female advantage in college completion: The role of family background and academic achievement. American Sociological Review. 2008;71(4):515–541. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass Larry L, Presser Harriet B. Contraceptive sterilization in the U.S.: 1965 and 1970. Demography. 1972;9(4):531–548. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass Larry L. The risk of an unwanted birth: The changing context of contraceptive sterilization in the U.S. Population Studies. 1987;41(3):347–363. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass Larry L, Thomson Elizabeth, Godecker Amy L. Women, men, and contraceptive sterilization. Fertility and Sterility. 2000;73(5):937–946. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(00)00484-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan Lolita M, Westhoff Carolyn L. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertility and Sterility. 2010;94(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2010.03.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandra Anjani. Surgical sterilization in the United States: Prevalence and characteristics, 1965–95. Vital and Health Statistics. 1998;23(20):1–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- David Henry P, Skilogianis Joanna., editors. From Abortion to Contraception: A Resource to Public Policies and Reproductive Behaviour in Central and Eastern Europe from 1917 to the Present. Westport (CT): Greenwood Publishing Group; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Donadio Irene. The barometer of women’s access to modern contraceptive choice in ten European Union (EU) countries. Entre-Nous. 2013;79:20–21. [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhaut Mieke C W. Marital status and female and male contraceptive sterilization in the United States. Fertility & Sterility. 2015;130(6):1509–1515. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2015.02.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eeckhaut Mieke C W, Sweeney Megan M, Gipson Jessica D. Who is using long-acting reversible contraceptive methods? Findings from nine low-fertility countries. Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2014;46(3):149–155. doi: 10.1363/46e1914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg Michael L, Henderson Jillian T, Amory John K, Smith James F, Walsh Thomas J. Racial differences in vasectomy utilization in the United States: Data from the National Survey of Family Growth. Urology. 2009;74(5):1020–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2009.06.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- EngenderHealth. [Accessed 1 March 2013];Contraceptive Sterilization: Global Issues and Trends. 2002 http://www.engenderhealth.org/pubs/family-planning/contraceptive-sterilization-factbook.php.

- Forste Renata, Tanfer Koray, Tedrow Lucky. Sterilization among currently married men in the United States, 1991. Family Planning Perspectives. 1995;27(3):100–107(+122). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frejka Tomas. Birth regulation in Europe: Completing the contraceptive revolution. Demographic Research. 2008;19(5):73–84. [Google Scholar]

- Godecker Amy L, Thomson Elizabeth, Bumpass Larry L. Union status, marital history and female contraceptive sterilization in the United States. Family Planning Perspectives. 2001;33(1):35–41(+49). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady Cynthia D, Schwarz Eleanor B, Emeremni Chetachi A, Yabes Jonathan, Akers Aletha, Zite Nikki, Borrero Sonya. Does a history of unintended pregnancy lessen the likelihood of desire for sterilization reversal? Journal of Women’s Health. 2013;22(6):501–506. doi: 10.1089/jwh.2012.3885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grady William R, Tanfer Koray, Billy John OG, Lincoln-Hanson Jennifer. Men’s perceptions of their roles and responsibilities regarding sex, contraception and childrearing. Family Planning Perspectives. 1996;28(5):221–226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray Edith, McDonald Peter. Using a reproductive life course approach to understand contraceptive method use in Australia. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2010;42(1):43–58. doi: 10.1017/S0021932009990381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimes David A. Forgettable contraception. Contraception. 2009;80(6):497–499. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2009.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen Randall, King Desmond S. Sterilized by the State: Eugenics, Race, and the Population Scare in Twentieth-Century North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Hubacher David, Cheng Diana. Intrauterine devices and reproductive health: American women in feast and famine. Contraception. 2004;69(6):437–446. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2004.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones Jo, Mosher William, Daniels Kimberly. Current contraceptive use in the United States, 2006–2010, and changes in patterns of use since 1995. National Health Statistics Reports. 2012;60:1–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane Jennifer B, Philip Morgan S, Harris Kathleen M, Guilkey David K. The educational consequences of teen childbearing. Demography. 2013;50(6):2129–2150. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0238-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landale Nancy S, Schoen Robert, Daniels Kimberly. Early family formation among white, black, and Mexican American women. Journal of Family Issues. 2010;31(4):445–474. doi: 10.1177/0192513X09342847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lodewijckx Edith. Vrijwillige sterilisatie in Vlaanderen rond het jaar 2000 [Voluntary sterilization in Flanders around the year 2000] Tijdschrift voor Geneeskunde. 2000;56(17):1247–1257. [Google Scholar]

- Lodewijckx Edith. Voluntary sterilization in Flanders. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2002;34(1):29–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinez Gladys, Daniels Kimberly, Chandra Anjani. National Health Statistics Reports, no. 51. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2012. Fertility of men and women aged 15–44 years in the United States: National Survey of Family Growth, 2006–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mosher William D, Jones Jo. Vital and Health Statistics, Series 23, no. 29. Hyattsville (MD): National Center for Health Statistics; 2010. Use of contraception in the United States: 1982–2008. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddens Björn J, Visser Adriaan P, Vemer Hans M, Everaerd Walter TAM. Contraceptive use and attitudes in reunified Germany. European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1994a;57(3):201–208. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(94)90301-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddens Björn J, Visser Adriaan P, Vemer Hans M, Everaerd Walter TAM, Lehert Philippe. Contraceptive use and attitudes in Great Britain. Contraception. 1994b;49(1):73–86. doi: 10.1016/0010-7824(94)90110-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddens Björn J. Contraceptive use and attitudes in Italy 1993. Human Reproduction. 1996;11(3):533–539. doi: 10.1093/humrep/11.3.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddens Björn J, Milsom Ian. Contraceptive practice and attitudes in Sweden 1994. Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 1996;75(10):932–940. doi: 10.3109/00016349609055031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oddens Björn J, Lehert Philippe. Determinants of contraceptive use among women of reproductive age in Great Britain and Germany I: Demographic factors. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1997;29(4):415–435. doi: 10.1017/s002193209700415x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philliber Susan G, Philliber William W. Social and psychological perspectives on voluntary sterilization: A review. Studies in Family Planning. 1985;16(1):1–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Presser Harriet B, Bumpass Larry L. The acceptability of contraceptive sterilization among U.S. couples: 1970. Family Planning Perspectives. 1972;4(4):18–26. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richters Juliet, Grulich Andrew E, de Visser Richard O, Smith Anthony MA, Rissel Chris E. Contraceptive practices among a representative sample of women. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 2003;27(2):210–216. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-842x.2003.tb00810.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rind Patricia. Vasectomy proves to be preferable to female sterilization. Family Planning Perspectives. 1989;21(4):191. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss Ronald R, Liao Futing. Medical and contraceptive reasons for sterilization in the United States. Studies in Family Planning. 1988;19(6):370–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riphagen FE, Lehert Philippe. A survey of contraception in five West European countries. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1989;21(1):23–46. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000017703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross John A, Huber Douglas H, Hong Sawon. Worldwide trends in voluntary sterilization. International Family Planning Perspectives. 1986;12(2):34–39. [Google Scholar]

- Santow Gigi. Trends in contraception and sterilization in Australia. The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. 1991;31(3):201–208. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-828x.1991.tb02781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoen Johanna. Choice and Coercion: Birth Control, Sterilization, and Abortion in Public Health and Welfare. Chapel Hill & London: The University of North Carolina Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Severson Kim. Thousands sterilized, a state weighs restitution. [Accessed 21 September 2012];The New York Times. 2011 Dec 9; http://www.nytimes.com/2011/12/10/us/redress-weighed-for-forced-sterilizations-in-north-carolina.html.

- Serbanescu Florina, Morris Leo, Stupp Paul, Stanescu Alin. The impact of recent policy changes on fertility, abortion, and contraceptive use in Romania. Studies in Family Planning. 1995;26(2):76–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serbanescu Florina, Morris Leo, Nutsubidze Nick, Imnadze Paata, Shaknazarova Marina. Reproductive Health Survey Georgia, 1999–2000. Atlanta (GA): Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Serbanescu Florina, Goldberg Howard, Morris Leo. Reproductive health in the transition countries of Europe. In: Macura M, MacDonald AL, Haug W, editors. The New Demographic Regime: Population Challenges and Policy Responses. New York & Geneva: United Nations; 2005. pp. 177–198. [Google Scholar]

- Serbanescu Florina, Stupp Paul, Westoff Charles. Contraception matters: Two approaches to analyzing evidence of the abortion decline in Georgia. International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 2010;36(2):99–110. doi: 10.1363/ipsrh.36.099.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro Thomas M, Fisher William, Diana Augusto. Family planning and female sterilization in the United States. Social Science & Medicine. 1983;17(28):1847–1855. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(83)90161-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shih Grace, Turok David K, Parker Willie J. Vasectomy: The other (better) form of sterilization. Contraception. 2011;83(4):310–315. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2010.08.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonfield Adam. Popularity disparity: Attitudes about the IUD in Europe and the United States. Guttmacher Policy Review. 2007;10(4):19–24. [Google Scholar]

- Stern Alexandra M. Sterilized in the name of public health: Race, immigration, and reproductive control in modern California. American Journal of Public Health. 2005;95(7):1128–1138. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.041608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sweeney Megan M, Raley R Kelly. Race, ethnicity, and the changing context of childbearing in the United States. Annual Review of Sociology. 2014;40:539–558. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-071913-043342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trussell James. Contraceptive failure in the United States. Contraception. 2011;83(5):397–404. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2011.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Generations & Gender Programme: Survey Instruments. New York & Geneva: United Nations; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. [Accessed 22 March 2013];World Contraceptive Use 2012. 2012 http://www.un.org/esa/population/publications/WCU2012/MainFrame.html.

- United Nations. [Accessed 12 May 2014];World Contraceptive Use 2013. 2013 http://www.un.org/en/development/desa/population/publications/family/contraceptive-wallchart-2013.shtml.

- Westoff Charles F. Recent Trends in Abortion and Contraception in 12 Countries. Calverton (MD): ORC Macro; 2005. DHS Analytical Studies No. 8. [Google Scholar]

- Yusuf Farhat, Siedlecky Stefania. Patterns of contraceptive use in Australia: Analysis of the 2001 National Health Survey. Journal of Biosocial Science. 2007;39(5):735–744. doi: 10.1017/S0021932006001738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zampas Christina, Lamačková Adriana. Forced and coerced sterilization of women in Europe. International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics. 2011;114(2):163–166. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.