Abstract

Kidneys critically contribute to the maintenance of whole-body homeostasis by governing water and electrolyte balance, regulating extracellular fluid volume, plasma osmolality and blood pressure. Renal function is regulated by numerous systemic endocrine and local mechanical stimuli. Kidneys possess a complex network of membrane receptors, transporters and ion channels which allows responding to this wide array of signaling inputs in an integrative manner. Transient receptor potential (TRP) channel family members with diverse modes of activation, varied permeation properties and capability to integrate multiple downstream signals are pivotal molecular determinants of renal function all along the nephron. This review summarizes experimental data on the role of TRP channels in a healthy mammalian kidney and discusses their involvement in renal pathologies.

INTRODUCTION

Kidneys are the master regulators of the internal milieu of the body. In spite of greatly varying dietary intake of water and electrolytes, these paired organs adjust urinary volume and composition in a discrete but synchronous manner to achieve systemic homeostasis. Through a direct interaction with cardiovascular system at the site of numerous glomeruli, around 40x plasma volume (~180 Liters in humans) is filtered on a daily basis, whereas only <1% of the filtrate is excreted with urine. To accomplish this ultimate physiological function, kidneys possess complex and highly structurally organized molecular cascades to perform vectorial movement (i.e. transport) of water and solutes, such as all electrolytes, glucose, amino acids, etc., across epithelial monolayers in renal tubules. The bulk of filtered plasma is reabsorbed in the proximal tubule (PT) and the loop of Henle in a constitutive manner and the distal nephron segments, including the distal convoluted tubule (DCT), the connecting tubule (CNT) and the collecting duct (CD) operate at a much lower capacity and are responsible for fine-tuning of water and electrolyte balance in response to dietary and endocrine inputs [1-4]. In addition, glomeruli serve as a reliable barrier preventing a loss of blood cells and large plasma proteins, such as albumins and immunoglobulins, with urine. Even subtle alterations in kidney function due to genetic defects can have profound pathophysiological consequences resulting in systemic imbalance of electrolytes and blood pressure distortions [5]. Extensive experimental and clinical effort during the last several decades drastically improved our understanding molecular nature of the transporting and signaling mechanisms underlying the processes of filtration, reabsorption and secretion of water and solutes by the kidney. Serving as conduits for facilitated movement of cations through otherwise virtually impermeable plasma membrane of cells and being activated in response to variety of environmental signals, many transient receptor potential (TRP) channels are now becoming recognized as essential components of both transport and sensory/signaling processes in the kidney tissue.

Superfamily of TRP channels consists of 28 proteins sharing six-transmembrane domain homology with a remarkable diversity of gating properties, selectivity and activation in response to various stimuli, including temperature, chemical agents, and mechanical forces [6]. TRP channels can be further divided into TRPC (canonical; 7 members), TRPV (vanilloid; 6 members), TRPM (melastatin; 8 members), TRPP (polycystin; 3 members), TRPA (ankyrin; 1 member), TRPML (mucolipin; 3 members), and TRPN (no mechanoreceptor potential C; 1 member, not found in mammals) subfamilies [6]. The majority of the TRP channels are abundantly expressed along the renal nephron starting from glomerulus to the inner medullary CD [7, 8]. Of interest, the expression patterns are usually restricted to one (such as TRPM6) or a couple of (as TRPV4, TRPV5 and TRPC6, for instance) nephron segments [7-10]. Such spatial separation and distinct activation mechanisms likely underlie the specific function of a particular TRP channel in the kidney. In this review, we discuss recent experimental evidence revealing physiological roles of TRP channels in the kidney epithelia and emphasize hereditary Mendelian disorders resulting from TRP channels malfunctioning as well as novel insights into TRP functions obtained from genetic animal models.

TRPC6 and glomerular health

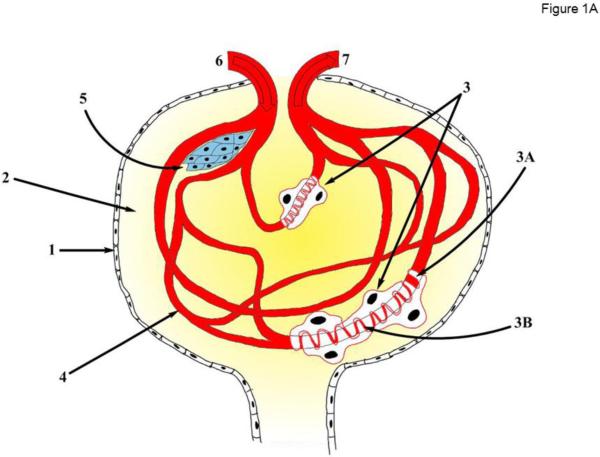

A glomerulus is a dense capillary network contained within Bowman’s (or glomerular) capsule at the beginning of the tubular component of the nephron (Figure 1A). It serves as the initial basic filtration unit of the kidney. Glomerular filtration barrier is a complex and highly specialized apparatus consisting of three major components: the fenestrated endothelium of the glomerular capillaries; the glomerular basement membrane (GBM) formed by the fused basal laminas of the capillary endothelium and podocytes – visceral epithelial cells enveloping the capillaries, and, finally, by the slit diaphragms of the podocytes. Another specialized cell type of smooth muscle origin – the intraglomerular mesangial cells, provide structural support for the glomerular capillaries and regulate blood flow by their contractile activity. Intrinsically high hydrostatic pressure in the glomerular capillaries drives the process of filtration allowing free movement of water and relatively small solutes to the Bowman capsule, while restricting penetration of blood cells and large macromolecules, such as plasma albumins and immunoglobulins. Podocytes are highly specialized epithelial cells with a limited regenerative ability in the inner part of the Bowman capsule, which form the slit diaphragms between their foot processes attached to the GBM to govern the final step of filtration process [11] (see Figure 1A).

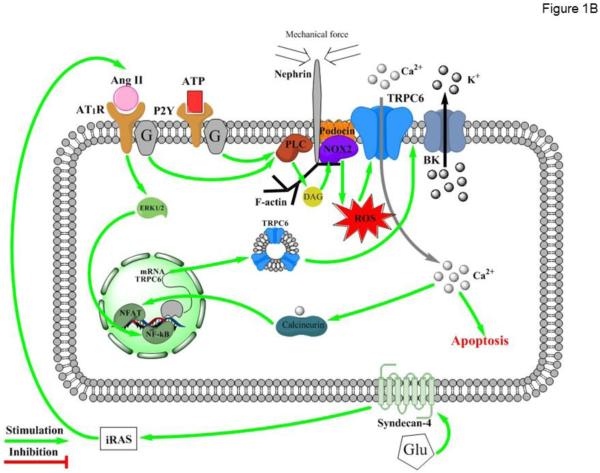

Figure 1. TRPC6 function in glomerulus.

(A) Principal scheme of glomerular structure. 1 - Bowman's capsule; 2 - Bowman's space; 3 – Podocyte; 3A - Foot processes; 3B - Slit diaphragm; 4 - Glomerulus capillaries; 5 - Mesangial cells; 6 - Afferent arteriole; 7 - Efferent arteriole. (B) Regulation of TRPC6 activity in podocytes. Ang II – Angiotensin II; AT1R – Angiotensin II receptor type 1; ATP – Adenosine triphosphate; P2Y – purinergic receptor type Y; ERK1/2 - extracellular-signal-regulated kinases (also known as MAPK kinases) PLC –phospholipase C; DAG – diacylglycerol; NOX2 – NADPH oxidase isoform 2; ROS – reactive oxygen species; BK – Ca2+-activated big conductance K+ channel; NFAT - nuclear factor of activated T-cells; NF-kB - nuclear factor kappa-light-chain-enhancer of activated B cells; Glu – glucose; iRAS – intrarenal Renin Angiotensin System.

Podocytes are widely recognized to play a key role in normal glomerular function as increased GBM permeability is restricted to the area of podocytes damage [12-17]. Podocytes are known to sense dynamically changing hydrostatic pressure by contracting and elevating intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) [18, 19]. Indeed, real-time multiphoton imaging of the intact rat kidney in vivo reveals that [Ca2+]i elevations and contractions in podocytes coincide with afferent arteriole contraction when intraglomerular capillary pressure is at its lowest [16]. Several Ca2+-permeable TRP channels, such as TRPC1, TRPC2, TRPC3, TRPC5, and TRPC6; are expressed in either native or immortalized podocytes [7, 20, 21]. As will be detailed below, TRPC6 plays a dominant role in these [Ca2+]i elevations in podocytes. The contribution of other TRPC channels is less clear, but recent genetic animal knockout studies also demonstrate a critical role for TRPC5 in [Ca2+]i signaling in podocytes [22, 23].

TRPC6 is a heterotetrameric, non-selective (relative permeability of Ca2+ to Na+ as 2:1) cation channel that can be activated in response to G protein signaling specifically via a diacylglycerol (DAG)-dependent pathway [24, 25]. TRPC6 basal activity is very low in podocytes, but can be greatly potentiated in response to post-translational modifications (i.e. glycosylation and phosphorylation) as well as mechanical pressure [26-28]. While the channel itself is not intrinsically mechanosensitive, it was proposed that TRPC6 can interact with podocin, a podocyte-specific protein, to acquire mechanosensitive properties [29, 30]. It is viewed that this interaction might be a part of a large mechanosensitive multiprotein channel complex, also including nephrin [21, 31], NOX2 [32], phospholipase C (PLC)-γ1 [33], F-actin [18, 34] and probably other proteins, responding to extracellular pressure and activating calcium influx through TRPC6 (see Figure 1B). It has been well described that long-term increases in hydrostatic pressure in the glomerular capillaries can cause podocyte damage, leading to proteinuria [35]. It is logical to assume that [Ca2+]i-dependent process and cytoskeleton reorganization contribute to the pathology. Indeed, the field was electrified by the relatively recent discovery that gain-of-function mutations in N- and C-termini of the TRPC6 cause Focal and Segmental Glomerulosclerosis (FSGS) in humans [17, 21]. FSGS symptoms include renal insufficiency, proteinuria, hypoalbuminemia, and hypertension eventually leading to kidney failure. FSGS-causing mutations associated with both increases in surface channel expression and single channel TRPC6 activity have been reported [17, 21, 36]. These mutations result in a slow onset FSGS (16-61 years) and the severity and progression of the disease seem to depend on the magnitude of TRPC6 potentiation (reviewed in [37]). The general mechanism is that sustained hyper-activation of podocyte TRPC6 channels results in [Ca2+]i overload, foot process effacement, podocyte detachment, and glomerulosclerosis. Coherent experimental evidence have been also obtained in animal genetic models where podocyte-specific over-expression of wild-type or FSGS causing mutations of TRPC6 was sufficient to induce glomerular lesions and proteinuria similar to that of FSGS, although the phenotype was mild and had a late onset [38]. Furthermore, in cultured podocytes transiently over-expressing TRPC6, cell processes were remarkably reduced in association with the derangement of cytoskeleton demonstrated by the abnormal distribution of intracellular F-actin [34]. However, this phenomenon has not been observed in TRPC6-overexpressing native podocytes [39]. While only a minor portion of the described hereditary FSGS (5 out of 71 families) is caused by TRPC6 malfunction, FSGS can also be caused by mutations and deletions in multiple genes encoding proteins associated with TRPC6, such as podocin [40]. Of interest, knockdown of podocin markedly increased stretch-evoked activation of TRPC6 in cultured podocytes, thus mimicking gain-of-function state of the channel [41]. Overall, the existing experimental evidence so far support the concept that pharmacological inhibition of TRPC6 or signaling pathways causative for the channel activation has potential to treat various proteinuric pathologies in the clinic.

Elevated blood pressure, particularly associated with increased circulating Angiotensin II (Ang II) levels is detrimental to glomerular health leading to glomerulosclerosis and proteinuria in patients and in numerous experimental animal models (reviewed in [42]). Several research groups documented a marked upregulation of single channel TRPC6 activity and channel expression in response to Ang II leading to elevated [Ca2+]i [43-46]. TRPC6 ablation drastically attenuated Ang II-induced [Ca2+]i elevations in native podocytes [43]. The signaling pathway likely involves AT1R-Gq/11-PLC dependent generation of DAG, which can either directly or indirectly via stimulation of NOX2 and production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) stimulate TRPC6 activity [44] (Figure 1B). TRPC6-mediated Ca2+ entry into podocytes activates Ca2+-dependent serine/threonine phosphatase, calcineurin to stimulate the nuclear factor NFAT through an unknown mechanism [46]. NFAT is capable to increase TRPC6 mRNA levels leading to a long term increase in TRPC6 expression, Ca2+ overload, and apoptosis of podocytes [45]. In addition, Ang II can also promote TRPC6 expression in an ERK1/2-NF-κB dependent manner [45]. Consistently, inhibition of AT1R with losartan have a beneficial role on reducing proteinuria and podocyte injury via downregulation of TRPC6 expression in podocytes [47].

Diabetes mellitus commonly leads to diabetic nephropathy associated with podocyte loss and compromised slit diaphragm, causing overt proteinuria and kidney function decline [48, 49]. Elevated glucose levels specifically increase TRPC6 protein and mRNA expression and TRPC6-dependent Ca2+ influx in cultured podocytes [50]. Similarly, TRPC6 expression is increased in podocytes from STZ-treated rats, a well-accepted model of Diabetes Mellitus Type I [50]. Interestingly, this upregulation occurs in an Ang II-dependent manner, since AT1R blockade and inhibition of local Ang II production through angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition prevents glucose-mediated increases in TRPC6 expression [50]. Exposure to high glucose also upregulates renin mRNA expression in podocytes and increases the relative proportion of renin-positive cells leading to increased Ang I production [51]. Thus, it appears that high glucose activates the intrarenal renin-angiotensin system, promoting local Ang II production, generation of ROS and augmented TRPC6 activity [50-52]. The complete pathway has yet to be established, but a critical role of Syndecan-4 (SDC-4), a member of the type I transmembrane heparan sulfate proteoglycan superfamily has been recently proposed [52] (Figure 1B). Interestingly, high glucose downregulates TRPC6 protein expression and impairs TRPC6-dependent Ca2+ entry in response to ANG II in contractile mesangial cells, which are located within glomerular capillary loops to regulate glomerular hemodynamics [53]. The mechanism of this downregulation is unknown but it is proposed that TRPC6 deficiency and impaired contractility of the mesangial cells might be an underlying mechanism for the hyperfiltration seen in the early stages of diabetes.

In addition to Ang II, purinergic signaling cascade also plays a critical role in upregulation of TRPC6-mediated Ca2+ influx. ATP is a ubiquitous extracellular signaling molecule and augmented ATP release/secretion in response to mechanical stress have been described for kidney epithelial cells [54]. Sustained ATP signaling via stimulation of P2Y receptors and subsequently TRPC6 activity could contribute to foot process effacement, Ca2+-dependent changes in gene expression, and/or detachment of podocytes [55]. Interestingly, augmented TRPC6 activity in response to ATP also depends on generation of ROS [55]. It is possible that the close association of the channel with NOX cascade (likely NOX2) makes TRPC6 particularly susceptible to local ROS production (see Figure 1B). Indeed, ROS are known to be deleterious for podocyte function and glomerular health [56] and ROS scavengers, such as tempol, have prominent anti-proteinuric effects [57].

While pathophysiological consequences of TRPC6 over-activation in podocytes are beyond doubts, the significance of the channel during the normal physiology is less clear. TRPC6 channels have been suggested to physically and functionally interact with large conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BK) channels in podocytes [32] (Figure 1B). This coupling might be important for controlling membrane voltage in podocytes and for fine-tuning mechanosensitive Ca2+ influx in these cells. However, no alterations in glomeruli morphology and filtration properties have been reported in TRPC6 knockout mice [58]. One possibility could be that the lack TRPC6 expression can be compensated by other mechanisms, most notably TRPC5 [22]. However, genetic deletion of either pore forming α or Ca2+-modulatory β subunits of BK also do not result in appreciable alterations of glomerular structure/function despite moderate hypertension and hyperaldosteronism [59, 60]. Alternatively, a purinergic P2X4 channel, capable of permeating both Ca2+ and K+, can exert a mechanotransductory function in podocytes independently of TRPC channels [61]. Apparently, future studies are required to fully delineate the physiological relevance of TRPC6 and other TRPC channels in glomeruli.

Importance of TRPM6 and TRPV5 for controlled renal handling of divalent cations

Divalent cations, such as Mg2+ and Ca2+, participate in a variety of physiologically relevant processes ranging from protein and DNA synthesis, intracellular signaling to neurotransmission, hormone secretion, vascular contractility, and bone formation [62, 63]. Both ions are kept within tightly defined limits in the plasma (~1 mM for ionized Ca2+ and ~0.5 mM for ionized Mg2+) due to coordinated intestinal absorption and renal reabsorption regulated by several endocrine factors, most notably parathyroid hormone (PTH), vitamin D, and epidermal growth factor (EGF), as will be detailed below. Systemic Mg2+ and Ca2+ imbalance results in numerous severe pathologies associated with arrhythmias, seizures, etc. [64].

Approximately 90% of the filtered amount of Mg2+ and Ca2+ ions is reabsorbed in the PT and the thick ascending limb (TAL) in a passive manner through paracellular diffusion secondary to the NaCl transport. The remaining ~10% is reabsorbed exclusively by transcellular route in the DCT and the initial part of the CNT (only for Ca2+). Since no Mg2+ and Ca2+ can be reabsorbed in the downstream segments, divalent transport in the DCT directly determines urinary excretion of these electrolytes and its disruption alone is sufficient to elicit profound aberrations at the level of whole organism [65-67]. It appears that TRPM6 and TRPV5 channels serve as conduits for magnesium and calcium influx across the apical membrane, respectively.

DCT, located immediately after the TAL and macula densa, is an important site of controlled transport of Na+, Cl-, K+, Mg2+, and Ca2+ [68]. Despite being the shortest tubular segment of the renal nephron, DCT can be further divided into two functionally different parts: DCT1 (also often termed as early DCT) and DCT2 (late DCT) based on their responsiveness to mineralocorticosteroid aldosterone. DCT1, being insensitive to aldosterone, is the major place of TRPM6-dependent Mg2+ reabsorption by the renal nephron, whereas transcellular Ca2+ transport here is minimal [69]. In contract, DCT2 responds to aldosterone due to expression of the enzyme 11-β hydroxycorticosteroid dehydrogenase protecting mineralocorticosteroid receptors from circulating cortisol, and along with the initial part of CNT constitute the site of regulated Ca2+ reabsorption via TRPV5 [9]. DCT2 can still reabsorb Mg2+, whilst to a lesser extend due to a lower concentration gradient for the ion (Figure 2).

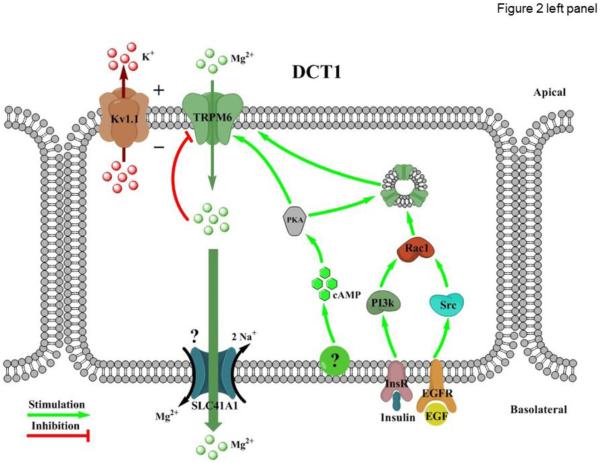

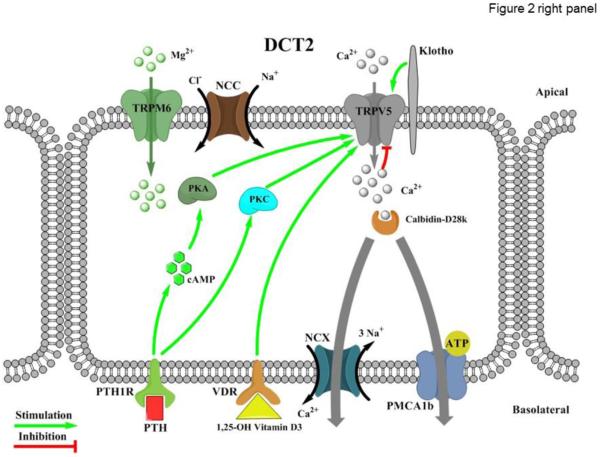

Figure 2. Divalent cation transport in the distal convoluted tubule (DCT).

Left and right panels represent regulation of TRPM6-dependent Mg2+ reabsorption in the DCT1 (early DCT) and TRPV5-dependent Ca2+ reabsorption in the DCT2 (late DCT), respectively. Left panel: Kv1.1 - Potassium voltage-gated channel subfamily A member 1; PKA – protein kinase A; Rac1 - Ras-related C3 botulinum toxin substrate 1; cAMP – cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PI3K - Phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate 3-kinase; Src - proto-oncogene encoding tyrosine kinase; SLC41A1 – solute carrier Mg2+ transporter family 41 member 1; InsR – insulin receptor; EGF - epidermal growth factor; EGFR - epidermal growth factor receptor. Right panel: NCC – sodium chloride cotransporter; PKA – protein kinase A; PKC – protein kinase C; cAMP - cyclic adenosine monophosphate; PTH – parathyroid hormone; PTH1R – parathyroid hormone receptor type 1; VDR – vitamin D receptor; NCX – Na+/Ca2+ exchanger; PMCA1b – plasma membrane Ca2+ ATPase type 1b; ATP - Adenosine triphosphate.

TRPM6 channel has now been recognized as the dominant pathway for Mg2+ entry across the apical membrane in DCT1 and DCT2 [70]. In the kidney, TRPM6 expression is restricted to the DCT, and the channel is also present in intestinal epithelium where its activity is critical for Mg2+ transport [10]. Genetic ablation of TRPM6 is embryonically lethal in mice. TRPM6 +/− animals display mild hypomagnesemia but urinary Mg2+ excretion was unaffected [65]. Furthermore, the importance of TRPM6 for Mg2+ homeostasis was emphasized by the recent discovery that loss-of-function mutations in the channel cause hereditary hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia (HSH) in humans [71-73]. The pathology is characterized by reduced intestinal Mg2+ absorption, increased urinary Mg2+ levels, and hypoparathyroidism causing hypocalcemia. Other symptoms usually involve convulsions, seizures, and tetany. Dietary Mg2+ supplementation, while cannot completely restore normal plasma Mg2+ levels, partially mitigates the symptoms of HSH [74, 75]

Similar to other TRPs, TRPM6 is a voltage-insensitive, cation-permeable channel consisting of four 6-transmembrane domain subunits [76]. The distinctive feature of TRPM6 is that the channel is capable of conducting Mg2+ at much higher rate than Ca2+ (the ratio is 5:1) [10] enabling TRPM6 to serve as an effective conduit for the apical Mg2+ entry in the DCT. The basolateral Mg2+ exit could possibly be mediated by the recently discovered magnesium/sodium exchanger SLC41A1 family [77, 78], while other undefined mechanisms may also exist. TRPM6 activity is inhibited when intracellular Mg2+ concentration is high [10]. The mechanism likely involves a direct regulation of C-terminal kinase activity of the channel by Mg-ATP [79]. It is possible that this negative feedback protects DCT cells from over-activation of TRPM6. Since TRPM7, another Mg2+-permeable channel, is also expressed in DCT, it remains debatable whether TRPM6 exists primarily as a homotetramer or TRPM6/7 heterotetramer [80, 81]. Embryonic lethality of TRPM7 knockout mice [82] precludes further investigations of the importance of the channel in systemic Mg2+ balance. It should be noted though that deletion of Trpm7 in T cells did not affect acute uptake of Mg2+, arguing against a role of TRPM7 [82]. Furthermore, TRPM7-causing pathologies of systemic Mg2+ balance have not been described in humans.

Relatively little is known about mechanisms controlling TRPM6 activity and TRPM6-mediated Mg2+ transport in the DCT. Only a minimal concentration gradient exists between extracellular and intracellular Mg2+ and the transport seems to greatly depend on trans-epithelial voltage existing in the DCT. In support of this concept, a loss-of-function mutation in the apically localized voltage gated Kv1.1 channel in the DCT causes autosomal dominant hypomagnesemia in humans [83, 84]. It is proposed that Kv1.1 by secreting K+ into tubular lumen provides a favorable electrochemical driving force for TRPM6-dependent Mg2+ influx (Figure 2). Similarly, mutations in Kir4.1 (KCNJ10) channel, mediating basolateral K+ recycling and basolateral membrane voltage, lead to EAST/SESAME syndrome also associated with renal Mg2+ wasting and hypomagnesemia [85, 86], at least partially due to disruption of basolateral Mg2+ exit in DCT.

TRPM6 activity and expression are under control of several endocrine factors, most notably estrogen, insulin and EGF [87-89]. Estrogen has been proposed to stimulate TRPM6 through a mechanism involving disassociation of the repressive estrogen responsive protein [90]. EGF through its basolaterally localized receptors (EGFR) increases TRPM6 activity and surface expression through both the Src family of tyrosine kinases and the downstream effector Rac1 [88]. Insulin also augments TRPM6 activity via a phosphoinositide 3-kinase and Rac1-mediated elevation of cell surface expression of TRPM6 [89]. Of clinical relevance, renal magnesium wasting is a common side effect during anti-cancer chemotherapy involving inhibitors of EGFR, such as cetuximab [91]. Consistently, cisplatin downregulates the EGF and TRPM6 mRNA levels and increases the fractional excretion Mg2+, suggesting that cisplatin treatment results in a diminished renal Mg2+ reabsorption via TRPM6 [92]. Adenylyl Cyclase 3 (AC3)-PKA signaling pathway A also increases TRPM6 abundance at the apical plasma membrane and channel activity, but the upstream extracellular signal was not defined [93]. In addition to hormonal control, renal TRPM6 expression is under control of other systemic factors. Thus, dietary Mg2+ restriction upregulates TRPM6 expression, while Mg2+ supplementation resulted in a significant decrease in protein levels [94]. TRPM6 activity also depends on pH status. Systemic acidosis decreases TRPM6 abundance and promotes urinary Mg2+ wasting [95-97], whereas alkalosis leads to renal magnesium retention [97, 98]

TRPV5 (originally named as ECaC1, the epithelial Ca2+ channel) has been identified as the dominant conduit mediating Ca2+ influx across the apical plasma membrane in the DCT and CNT [9]. The transcellular Ca2+ transport cascade also involves Calbindin-D28k which rapidly captures Ca2+ transported through TRPV5 and shuttles it to the basolateral membrane where Ca2+ is exported through the Na+/Ca2+ exchanger (NCX1) and the plasma membrane calcium-ATPase PMCA1b [99, 100] (Figure 2). Unlike other TRP channels, TRPV5 is highly selective to Ca2+ (permeability Ca2+ to Na+ as 100:1) [101, 102]. TRPV5 is constitutively active, when [Ca2+]i is low. Calbindin-D28K translocates towards the plasma membrane and directly associates with TRPV5 at low [Ca2+]i levels to augment TRPV5-dependent Ca2+ influx [100]. In contrast, TRPV5 activity rapidly decreases when [Ca2+]i raises [103], likely protecting the cells from Ca2+ poisoning. Structurally and functionally similar to TRPV5, TRPV6 (originally termed as CaT1 and ECaC2) may also play a role in the transcellular Ca2+ reabsorption in the distal nephron. In rodents, TRPV6 mRNA can be detected starting from the DCT2 to the medullary collecting ducts [104], whilst to a much lower level than TRPV5 [105, 106]. TRPV5 −/− mice demonstrate drastic urinary Ca2+ wasting and exhibit significant disturbances in bone structure, including reduced trabecular and cortical bone thickness [66]. Similarly, TRPV6 −/− are hypercalciuric, and exhibit a mild reduction in bone mineral density [67]. To some disappointment, there are no up-to-date clinical reports for disease-causing mutations of TRPV5 and TRPV6 in patients with hypercalciuria. It has been speculated that higher allele frequencies of TRPV5 and TRPV6 SNPs in African population when compared to Caucasians might contribute to a lower urinary Ca2+ excretion, the risk of developing kidney stones, and lower incidence of osteoporosis-related fractures (reviewed in [107]). However, epidemiological studies have yet to be carried out. Overall, despite the unequivocal experimental evidence in animals, the relevance of TRPV5/6 channels in clinic has not been directly established.

Thiazide diuretics, one of the most commonly prescribed antihypertensive drug classes to inhibit sodium reabsorption in the DCT by blocking sodium chloride cotransporter (NCC), are known to cause hypocalciuria (reviewed in [68]). The mechanism is not defined and both increased passive Ca2+ reabsorption in the proximal tubule and altered distal nephron TRPV5-dependent Ca2+ transport may contribute to calcium retention by the kidneys in response to thiazides [104, 108-110]. The controversies in experimental results may be at least partially explained by the ability of the DCT to become hypertrophic or hypotrophic depending on the extracellular fluid volume status [68].

Distal nephron calcium reabsorption is regulated by parathyroid hormone (PTH), which is released in response to decreased extracellular Ca2+ levels [64]. Upon binding to its receptor (PTH1R) in the DCT, PTH stimulates active Ca2+ reabsorption via the adenylyl cyclase–cAMP–protein kinase A (PKA) pathway to directly phosphorylate TRPV5 (but not TRPV6), thereby increasing single channel open probability [111]. The same signaling pathway has been recently reported to play a role in regulation of TRPV5 activity by β1-adrenergic receptor signaling [112], however, anti-calciuretic effects of adrenergic signaling in the kidney are not well described in clinic. In addition, PTH has been reported to affect TRPV5 function via other molecular mechanisms likely involving phosphorylation of the channel by PKC [113-115]. Activation of PKC was demonstrated to diminish the constitutive caveolae-mediated endocytosis of TRPV5, resulting in an increased channel abundance on the plasma membrane [115].

The vitamin D and specifically its most active form, 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3, is known to play a key role in controlling systemic Ca2+ homeostasis [64]. In the kidney, vitamin D receptor (VDR) expression is most prominent in the DCT and CNT, where it stimulates TRPV5-dependent Ca2+ reabsorption [9, 70, 99, 116]. Mice deficient for VDR have increased urinary Ca2+ levels and reduced TRPV5 expression [106]. Impaired vitamin D production and loss-of-function mutations in VDR lead to vitamin D-deficient rickets associated with compromised Ca2+ balance and hypocalcemia [117, 118]. Ca2+ supplementation has been proved to be beneficial in not only restoring Ca2+ balance but also in treating rickets [117]. Thus, it is quite possible that pharmacological potentiation of TRPV5 (as well as TRPV6) might be of clinical importance to manage this pathology.

Significant experimental effort was devoted to investigation of the anti-aging single transmembrane glycoprotein Klotho in the renal calcium handling [119, 120]. Of interest, the pattern of Klotho expression in the kidney coincides with the expression of TRPV5 [121]. Klotho exerts complex upregulation of TRPV5 activity from both the inside and outside of cells [122]. The intracellular action of Klotho is likely due to enhanced forward trafficking of channel proteins, whereas the extracellular action is due to inhibition of endocytosis by hydrolyzing extracellular sugar residues on TRPV5, entrapping the channel in the plasma membrane [121, 122]. Klotho −/− mice exhibit renal Ca2+ wasting due a failure to absorb Ca2+ in the DCT/CNT via TRPV5 [123].

TRPP2/TRPV4 complexes and mechanosensitivity of the renal tubule

Dynamic alterations in tubular flow produce mechanical pressure (also termed the shear stress) on the apical membrane [124]. The ability of cells to recognize and respond to these mechanical stimuli plays an important role in a variety of processes ranging from transport of water and solutes to cellular growth and differentiation [124, 125]. Epithelial cells respond to mechanical stimuli, in part, by elevating [Ca2+]i [124, 126-133]. Recent studies identified a critical role for a special cellular organelle, the primary cilium in mechanosensitivity in the renal tubule cells. The cilium protrudes into the tubular lumen and bends when tubular flow gets high [134-136]. This mechanical distortion activates the G-protein coupled receptor polycystin 1 (PC1) and the non-selective Ca2+-permeable channel from TRP family, TRPP2 (also known as polycystin 2; PC2). This induces Ca2+ influx at the base of the primary cilium triggering subsequent release of Ca2+ from the endoplasmic reticulum intracellular stores [134]. It should be noted though that intercalated cells in the CD, known to have no cilium [137], respond to elevated flow with a similar rise in [Ca2+]i [8, 126, 138], suggesting that the primary cilium is not an absolute requirement for mechanosensitivity.

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) encompasses a broad group of hereditary renal pathologies which are characterized by development and progressive growth of cysts filled with fluid (reviewed in [139]). PKD often progresses to the end-stage renal disease and sharp decline in GFR [139]. The most two common forms: autosomal dominant PKD (ADPKD) and autosomal recessive PKD (ARPKD), are caused by genetic mutations in genes encoding PC1/TRPP2 and fibrocystin, respectively [140, 141]. In both cases, renal cysts predominantly (in ADPKD patients) [142, 143] or exclusively (individuals with ARPKD) [144, 145] develop in the distal renal tubule, notably the CD. Multiple studies support the concept that de-differentiation and augmented cAMP-driven cellular proliferation observed during PKD is related to the inability to sense mechanical stimuli, such as elevated flow, and decreased basal [Ca2+]i levels, [134, 139, 146-153]. However, a direct mechanical activation of polycystins has never been demonstrated. Instead, TRPP2 heteromerizes with another mechanosensitive channel from TRP family, TRPV4, to gain mechanosensitive properties [154-156]. Indeed, disrupted activity of either TRPP2 [134] or TRPV4 [8] leads to inability of the renal tubule cells to respond to elevated flow with an increased [Ca2+]i. PC1 and fibrocystin also directly interact with TRPP2, [157-160], thereby forming a multiprotein mechanosensitive complex (Figure 3). It is interesting that TRPP2 mutations lead to ADPKD, whereas TRPV4 −/− mice and zebra fish have normal kidneys [155, 161]. This suggests that the relation between cystogenesis and disruption of mechanosensitivity is not straightforward. Recent effort of our group demonstrated that the genetic defect in fibrocystin in a rat model of ARPKD does not lead to immediate disruption of TRPV4-dependent mechanosensitive [Ca2+]i elevations in non-transformed tubules and loss of mechanosensitivity occurs just prior to or as an early event during cyst development [133]. We further demonstrated that prolonged systemic pharmacological stimulation of TRPV4 markedly blunted renal ARPKD manifestations by reducing cyst size and decreasing kidney/total body weight ratio, pointing to potential therapeutic and clinical relevance of this treatment [133]. However, the efficiency of this strategy in other forms of PKD (most notably ADPKD) has not been tested yet.

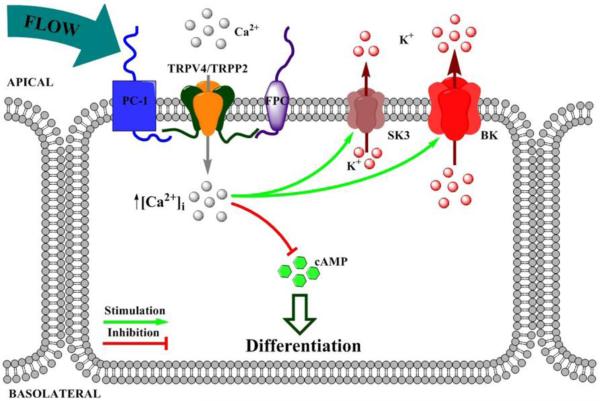

Figure 3. Functional coupling between mechanosensitivity and flow-dependent potassium secretion.

PC1 – polycystin 1; FPC – fibrocystin; SK3 - small conductance calcium-activated potassium channel 3; BK – Ca2+-activated big conductance K+ channel; cAMP - cyclic adenosine monophosphate.

It is well-established that increases in tubular flow, for example during treatment with diuretics, such as furosemide, produces marked kaliuresis [162, 163]. Inability of the kidney to exert a so-called flow-dependent potassium secretion leads to hyperkalemia and aldosteronism [60]. The activity of the Ca2+-dependent large conductance K+ (BK) channel in the CNT and CD plays a critical role in this process [162, 164-167]. The modulatory β1 subunit greatly potentiates sensitivity of the channel to increases in [Ca2+]i, with its ablation leading to compromised flow-induced K+ secretion [60]. In addition to BK, we have recently documented that the Ca2+-dependent small conductance SK3 (KCa2.3) channel [168] is also expressed at the apical border of both the CNT and CD [169]. Importantly, it has much higher affinity for Ca2+ over that observed for the BK channel [170, 171] and, hence, is well posed to play a key role in flow-dependent K+ secretion. Future studies are required to probe interplay and supremacy between these channels. Ca2+-permeable mechanosensitive TRPP2/TRPV4 complexes are ideally suited to regulate and control the process of flow-induced K+ secretion serving as a source of elevated [Ca2+]i (Figure 3). Genetic ablation of TRPV4 prevents flow-dependent elevations in K+ secretion in perfused CDs and blunts furosemide-induced kaliuresis, whereas pharmacological stimulation of TRPV4 recapitulates the effect of flow on potassium transport in wild type animals [165]. However, the physiological relevance of the regulation of flow-dependent potassium secretion by mechanosensitive TRPP2/TRPV4 complexes on systemic K+ balance has not been directly demonstrated.

Concluding remarks

TRP channels are abundantly expressed in the kidney where they play a critical role in many physiological processes, including maintenance of glomerular barrier and regulation of electrolyte transport by renal epithelium. High propensity to heteromerize allows TRP channels to form macromolecular associations with unique set of features and functions, such as mechanosensitive complex of PC1, TRPP2 and TRPV4. Genetic defects in TRPC6, TRPM6 and TRPP2 channels underlie clinically relevant channelopathies having renal origin. TRP channels are becoming increasingly appreciated as converging points and end-effectors of numerous endocrine pathways. This provides a strong impetus for the development of novel therapeutic approaches targeting TRP family members. At the same time, existing experimental evidence suggests that many more TRP channels with unknown or much less understood function exist in the renal tissue. While they do not play a role in kidney function at the baseline, these channels might be critical for adaptation to a particular stress condition. Future studies are granted to reveal their yet undefined physiological and pathophysiological relevance.

Acknowledgements

The research program in Dr. Pochynyuk’s lab is supported by NIH-NIDDK DK095029 (to O. Pochynyuk), and by AHA-15SDG25550150 (to M. Mamenko).

REFERENCES

- [1].Curthoys NP, Moe OW. Proximal tubule function and response to acidosis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014;9:1627–1638. doi: 10.2215/CJN.10391012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Mount DB. Thick ascending limb of the loop of Henle. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014;9:1974–1986. doi: 10.2215/CJN.04480413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Staruschenko A. Regulation of transport in the connecting tubule and cortical collecting duct. Comprehensive Physiology. 2012;2:1541–1584. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c110052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Subramanya AR, Ellison DH. Distal convoluted tubule. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014;9:2147–2163. doi: 10.2215/CJN.05920613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Lifton RP, Gharavi AG, Geller DS. Molecular mechanisms of human hypertension. Cell. 2001;104:545–556. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00241-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Venkatachalam K, Montell C. TRP channels. Annu Rev Biochem. 2007;76:387–417. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.103004.142819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Goel M, Sinkins WG, Zuo CD, Estacion M, Schilling WP. Identification and localization of TRPC channels in the rat kidney. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2006;290:F1241–1252. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00376.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Berrout J, Jin M, Mamenko M, Zaika O, Pochynyuk O, O'Neil RG. Function of TRPV4 as a mechanical transducer in flow-sensitive segments of the renal collecting duct system. JBiolChem. 2012;287:8782–8791. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.308411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hoenderop JG, van der Kemp AW, Hartog A, van de Graaf SF, van Os CH, Willems PH, et al. Molecular identification of the apical Ca2+ channel in 1, 25-dihydroxyvitamin D3-responsive epithelia. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1999;274:8375–8378. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.13.8375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Voets T, Nilius B, Hoefs S, van der Kemp AW, Droogmans G, Bindels RJ, et al. TRPM6 forms the Mg2+ influx channel involved in intestinal and renal Mg2+ absorption. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:19–25. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311201200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Pollak MR, Quaggin SE, Hoenig MP, Dworkin LD. The glomerulus: the sphere of influence. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2014;9:1461–1469. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09400913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tanner GA, Rippe C, Shao Y, Evan AP, Williams JC., Jr Glomerular permeability to macromolecules in the Necturus kidney. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2009;296:F1269–1278. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00371.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Neal CR, Crook H, Bell E, Harper SJ, Bates DO. Three-dimensional reconstruction of glomeruli by electron microscopy reveals a distinct restrictive urinary subpodocyte space. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2005;16:1223–1235. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004100822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Kim YH, Goyal M, Kurnit D, Wharram B, Wiggins J, Holzman L, et al. Podocyte depletion and glomerulosclerosis have a direct relationship in the PAN-treated rat. Kidney international. 2001;60:957–968. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2001.060003957.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mundel P, Reiser J. Proteinuria: an enzymatic disease of the podocyte? Kidney international. 2010;77:571–580. doi: 10.1038/ki.2009.424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Peti-Peterdi J, Sipos A. A high-powered view of the filtration barrier. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2010;21:1835–1841. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010040378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Winn MP, Conlon PJ, Lynn KL, Farrington MK, Creazzo T, Hawkins AF, et al. A mutation in the TRPC6 cation channel causes familial focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Science. 2005;308:1801–1804. doi: 10.1126/science.1106215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Endlich N, Kress KR, Reiser J, Uttenweiler D, Kriz W, Mundel P, et al. Podocytes respond to mechanical stress in vitro. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2001;12:413–422. doi: 10.1681/ASN.V123413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Friedrich C, Endlich N, Kriz W, Endlich K. Podocytes are sensitive to fluid shear stress in vitro. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2006;291:F856–865. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00196.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Kim EY, Alvarez-Baron CP, Dryer SE. Canonical transient receptor potential channel (TRPC)3 and TRPC6 associate with large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels: role in BKCa trafficking to the surface of cultured podocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2009;75:466–477. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.051912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Reiser J, Polu KR, Moller CC, Kenlan P, Altintas MM, Wei C, et al. TRPC6 is a glomerular slit diaphragm-associated channel required for normal renal function. Nature genetics. 2005;37:739–744. doi: 10.1038/ng1592. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Greka A, Mundel P. Balancing calcium signals through TRPC5 and TRPC6 in podocytes. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2011;22:1969–1980. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2011040370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Schaldecker T, Kim S, Tarabanis C, Tian D, Hakroush S, Castonguay P, et al. Inhibition of the TRPC5 ion channel protects the kidney filter. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2013;123:5298–5309. doi: 10.1172/JCI71165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Estacion M, Sinkins WG, Jones SW, Applegate MA, Schilling WP. Human TRPC6 expressed in HEK 293 cells forms non-selective cation channels with limited Ca2+ permeability. The Journal of physiology. 2006;572:359–377. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.103143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Shi J, Mori E, Mori Y, Mori M, Li J, Ito Y, et al. Multiple regulation by calcium of murine homologues of transient receptor potential proteins TRPC6 and TRPC7 expressed in HEK293 cells. The Journal of physiology. 2004;561:415–432. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.075051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Dietrich A, Mederos y Schnitzler M, Emmel J, Kalwa H, Hofmann T, Gudermann T. N-linked protein glycosylation is a major determinant for basal TRPC3 and TRPC6 channel activity. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:47842–47852. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302983200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hisatsune C, Kuroda Y, Nakamura K, Inoue T, Nakamura T, Michikawa T, et al. Regulation of TRPC6 channel activity by tyrosine phosphorylation. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:18887–18894. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311274200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Spassova MA, Hewavitharana T, Xu W, Soboloff J, Gill DL. A common mechanism underlies stretch activation and receptor activation of TRPC6 channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:16586–16591. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0606894103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Huber TB, Schermer B, Muller RU, Hohne M, Bartram M, Calixto A, et al. Podocin and MEC-2 bind cholesterol to regulate the activity of associated ion channels. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2006;103:17079–17086. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607465103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Huber TB, Schermer B, Benzing T. Podocin organizes ion channel-lipid supercomplexes: implications for mechanosensation at the slit diaphragm. Nephron Exp Nephrol. 2007;106:e27–31. doi: 10.1159/000101789. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Huber TB, Kottgen M, Schilling B, Walz G, Benzing T. Interaction with podocin facilitates nephrin signaling. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:41543–41546. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100452200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Kim EY, Anderson M, Wilson C, Hagmann H, Benzing T, Dryer SE. NOX2 interacts with podocyte TRPC6 channels and contributes to their activation by diacylglycerol: essential role of podocin in formation of this complex. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C960–971. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00191.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kanda S, Harita Y, Shibagaki Y, Sekine T, Igarashi T, Inoue T, et al. Tyrosine phosphorylation-dependent activation of TRPC6 regulated by PLC-gamma1 and nephrin: effect of mutations associated with focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:1824–1835. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-12-0929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jiang L, Ding J, Tsai H, Li L, Feng Q, Miao J, et al. Over-expressing transient receptor potential cation channel 6 in podocytes induces cytoskeleton rearrangement through increases of intracellular Ca2+ and RhoA activation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2011;236:184–193. doi: 10.1258/ebm.2010.010237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Endlich N, Endlich K. The challenge and response of podocytes to glomerular hypertension. Seminars in nephrology. 2012;32:327–341. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Heeringa SF, Moller CC, Du J, Yue L, Hinkes B, Chernin G, et al. A novel TRPC6 mutation that causes childhood FSGS. PloS one. 2009;4:e7771. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0007771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Dryer SE, Reiser J. TRPC6 channels and their binding partners in podocytes: role in glomerular filtration and pathophysiology. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2010;299:F689–701. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00298.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Krall P, Canales CP, Kairath P, Carmona-Mora P, Molina J, Carpio JD, et al. Podocyte-specific overexpression of wild type or mutant trpc6 in mice is sufficient to cause glomerular disease. PloS one. 2010;5:e12859. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Kistler AD, Singh G, Altintas MM, Yu H, Fernandez IC, Gu C, et al. Transient receptor potential channel 6 (TRPC6) protects podocytes during complement-mediated glomerular disease. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:36598–36609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.488122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Woroniecki RP, Kopp JB. Genetics of focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Pediatric nephrology. 2007;22:638–644. doi: 10.1007/s00467-007-0445-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Anderson M, Kim EY, Hagmann H, Benzing T, Dryer SE. Opposing effects of podocin on the gating of podocyte TRPC6 channels evoked by membrane stretch or diacylglycerol. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2013;305:C276–289. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00095.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Ma L, Fogo AB. Role of angiotensin II in glomerular injury. Seminars in nephrology. 2001;21:544–553. doi: 10.1053/snep.2001.26793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Ilatovskaya DV, Palygin O, Chubinskiy-Nadezhdin V, Negulyaev YA, Ma R, Birnbaumer L, et al. Angiotensin II has acute effects on TRPC6 channels in podocytes of freshly isolated glomeruli. Kidney international. 2014;86:506–514. doi: 10.1038/ki.2014.71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Anderson M, Roshanravan H, Khine J, Dryer SE. Angiotensin II activation of TRPC6 channels in rat podocytes requires generation of reactive oxygen species. J Cell Physiol. 2014;229:434–442. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Zhang H, Ding J, Fan Q, Liu S. TRPC6 up-regulation in Ang II-induced podocyte apoptosis might result from ERK activation and NF-kappaB translocation. Exp Biol Med (Maywood) 2009;234:1029–1036. doi: 10.3181/0901-RM-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Nijenhuis T, Sloan AJ, Hoenderop JG, Flesche J, van Goor H, Kistler AD, et al. Angiotensin II contributes to podocyte injury by increasing TRPC6 expression via an NFAT-mediated positive feedback signaling pathway. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:1719–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.06.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Chi X, Hu B, Yu SY, Yin L, Meng Y, Wang B, et al. Losartan treating podocyte injury induced by Ang II via downregulation of TRPC6 in podocytes. J Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone Syst. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1470320315573682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Diez-Sampedro A, Lenz O, Fornoni A. Podocytopathy in diabetes: a metabolic and endocrine disorder. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58:637–646. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Jefferson JA, Shankland SJ, Pichler RH. Proteinuria in diabetic kidney disease: a mechanistic viewpoint. Kidney international. 2008;74:22–36. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Sonneveld R, van der Vlag J, Baltissen MP, Verkaart SA, Wetzels JF, Berden JH, et al. Glucose specifically regulates TRPC6 expression in the podocyte in an AngII-dependent manner. Am J Pathol. 2014;184:1715–1726. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Durvasula RV, Shankland SJ. Activation of a local renin angiotensin system in podocytes by glucose. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2008;294:F830–839. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00266.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Thilo F, Lee M, Xia S, Zakrzewicz A, Tepel M. High glucose modifies transient receptor potential canonical type 6 channels via increased oxidative stress and syndecan-4 in human podocytes. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2014;450:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2014.05.116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Graham S, Ding M, Sours-Brothers S, Yorio T, Ma JX, Ma R. Downregulation of TRPC6 protein expression by high glucose, a possible mechanism for the impaired Ca2+ signaling in glomerular mesangial cells in diabetes. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2007;293:F1381–1390. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00185.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Vallon V. P2 receptors in the regulation of renal transport mechanisms. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2008;294:F10–27. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00432.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Roshanravan H, Dryer SE. ATP acting through P2Y receptors causes activation of podocyte TRPC6 channels: role of podocin and reactive oxygen species. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2014;306:F1088–1097. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00661.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Chen S, Meng XF, Zhang C. Role of NADPH oxidase-mediated reactive oxygen species in podocyte injury. BioMed research international. 2013;2013:839761. doi: 10.1155/2013/839761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Luan J, Li W, Han J, Zhang W, Gong H, Ma R. Renal protection of in vivo administration of tempol in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. J Pharmacol Sci. 2012;119:167–176. doi: 10.1254/jphs.12002fp. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Eckel J, Lavin PJ, Finch EA, Mukerji N, Burch J, Gbadegesin R, et al. TRPC6 enhances angiotensin II-induced albuminuria. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2011;22:526–535. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Rieg T, Vallon V, Sausbier M, Sausbier U, Kaissling B, Ruth P, et al. The role of the BK channel in potassium homeostasis and flow-induced renal potassium excretion. Kidney international. 2007;72:566–573. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Grimm PR, Irsik DL, Settles DC, Holtzclaw JD, Sansom SC. Hypertension of Kcnmb1−/− is linked to deficient K secretion and aldosteronism. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:11800–11805. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904635106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Forst AL, Olteanu VS, Mollet G, Wlodkowski T, Schaefer F, Dietrich A, et al. Podocyte Purinergic P2X4 Channels Are Mechanotransducers That Mediate Cytoskeletal Disorganization. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014111144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Hebert SC, Brown EM. The scent of an ion: calcium-sensing and its roles in health and disease. Current opinion in nephrology and hypertension. 1996;5:45–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Konrad M, Schlingmann KP, Gudermann T. Insights into the molecular nature of magnesium homeostasis. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2004;286:F599–605. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00312.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Blaine J, Chonchol M, Levi M. Renal Control of Calcium, Phosphate, and Magnesium Homeostasis. Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2015;10:1257–1272. doi: 10.2215/CJN.09750913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Woudenberg-Vrenken TE, Sukinta A, van der Kemp AW, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Transient receptor potential melastatin 6 knockout mice are lethal whereas heterozygous deletion results in mild hypomagnesemia. Nephron Physiology. 2011;117:p11–19. doi: 10.1159/000320580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Hoenderop JG, van Leeuwen JP, van der Eerden BC, Kersten FF, van der Kemp AW, Merillat AM, et al. Renal Ca2+ wasting, hyperabsorption, and reduced bone thickness in mice lacking TRPV5. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2003;112:1906–1914. doi: 10.1172/JCI19826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Bianco SD, Peng JB, Takanaga H, Suzuki Y, Crescenzi A, Kos CH, et al. Marked disturbance of calcium homeostasis in mice with targeted disruption of the Trpv6 calcium channel gene. Journal of bone and mineral research : the official journal of the American Society for Bone and Mineral Research. 2007;22:274–285. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.061110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].McCormick JA, Ellison DH. Distal convoluted tubule. Comprehensive Physiology. 2015;5:45–98. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c140002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Loffing J, Zecevic M, Feraille E, Kaissling B, Asher C, Rossier BC, et al. Aldosterone induces rapid apical translocation of ENaC in early portion of renal collecting system: possible role of SGK. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2001;280:F675–682. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.2001.280.4.F675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Woudenberg-Vrenken TE, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. The role of transient receptor potential channels in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2009;5:441–449. doi: 10.1038/nrneph.2009.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Schlingmann KP, Weber S, Peters M, Niemann Nejsum L, Vitzthum H, Klingel K, et al. Hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia is caused by mutations in TRPM6, a new member of the TRPM gene family. Nature genetics. 2002;31:166–170. doi: 10.1038/ng889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Walder RY, Landau D, Meyer P, Shalev H, Tsolia M, Borochowitz Z, et al. Mutation of TRPM6 causes familial hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia. Nature genetics. 2002;31:171–174. doi: 10.1038/ng901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Lainez S, Schlingmann KP, van der Wijst J, Dworniczak B, van Zeeland F, Konrad M, et al. New TRPM6 missense mutations linked to hypomagnesemia with secondary hypocalcemia. European journal of human genetics : EJHG. 2014;22:497–504. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2013.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Schlingmann KP, Waldegger S, Konrad M, Chubanov V, Gudermann T. TRPM6 and TRPM7--Gatekeepers of human magnesium metabolism. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1772:813–821. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2007.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Quamme GA. Recent developments in intestinal magnesium absorption. Current opinion in gastroenterology. 2008;24:230–235. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e3282f37b59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Chubanov V, Gudermann T. Trpm6. Handbook of experimental pharmacology. 2014;222:503–520. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-54215-2_20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Goytain A, Quamme GA. Functional characterization of human SLC41A1, a Mg2+ transporter with similarity to prokaryotic MgtE Mg2+ transporters. Physiological genomics. 2005;21:337–342. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.00261.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Kolisek M, Launay P, Beck A, Sponder G, Serafini N, Brenkus M, et al. SLC41A1 is a novel mammalian Mg2+ carrier. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:16235–16247. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707276200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Thebault S, Cao G, Venselaar H, Xi Q, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Role of the alpha-kinase domain in transient receptor potential melastatin 6 channel and regulation by intracellular ATP. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:19999–20007. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800167200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Li M, Jiang J, Yue L. Functional characterization of homo- and heteromeric channel kinases TRPM6 and TRPM7. The Journal of general physiology. 2006;127:525–537. doi: 10.1085/jgp.200609502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Schmitz C, Dorovkov MV, Zhao X, Davenport BJ, Ryazanov AG, Perraud AL. The channel kinases TRPM6 and TRPM7 are functionally nonredundant. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:37763–37771. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509175200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Jin J, Desai BN, Navarro B, Donovan A, Andrews NC, Clapham DE. Deletion of Trpm7 disrupts embryonic development and thymopoiesis without altering Mg2+ homeostasis. Science. 2008;322:756–760. doi: 10.1126/science.1163493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Glaudemans B, van der Wijst J, Scola RH, Lorenzoni PJ, Heister A, van der Kemp AW, et al. A missense mutation in the Kv1.1 voltage-gated potassium channel-encoding gene KCNA1 is linked to human autosomal dominant hypomagnesemia. The Journal of clinical investigation. 2009;119:936–942. doi: 10.1172/JCI36948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].van der Wijst J, Glaudemans B, Venselaar H, Nair AV, Forst AL, Hoenderop JG, et al. Functional analysis of the Kv1.1 N255D mutation associated with autosomal dominant hypomagnesemia. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2010;285:171–178. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.041517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Bockenhauer D, Feather S, Stanescu HC, Bandulik S, Zdebik AA, Reichold M, et al. Epilepsy, ataxia, sensorineural deafness, tubulopathy, and KCNJ10 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;360:1960–1970. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0810276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Scholl UI, Choi M, Liu T, Ramaekers VT, Hausler MG, Grimmer J, et al. Seizures, sensorineural deafness, ataxia, mental retardation, and electrolyte imbalance (SeSAME syndrome) caused by mutations in KCNJ10. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:5842–5847. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0901749106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Groenestege WM, Hoenderop JG, van den Heuvel L, Knoers N, Bindels RJ. The epithelial Mg2+ channel transient receptor potential melastatin 6 is regulated by dietary Mg2+ content and estrogens. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006;17:1035–1043. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Thebault S, Alexander RT, Tiel Groenestege WM, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. EGF increases TRPM6 activity and surface expression. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20:78–85. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008030327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Nair AV, Hocher B, Verkaart S, van Zeeland F, Pfab T, Slowinski T, et al. Loss of insulin-induced activation of TRPM6 magnesium channels results in impaired glucose tolerance during pregnancy. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2012;109:11324–11329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1113811109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Cao G, van der Wijst J, van der Kemp A, van Zeeland F, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Regulation of the epithelial Mg2+ channel TRPM6 by estrogen and the associated repressor protein of estrogen receptor activity (REA) The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:14788–14795. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M808752200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Schrag D, Chung KY, Flombaum C, Saltz L. Cetuximab therapy and symptomatic hypomagnesemia. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2005;97:1221–1224. doi: 10.1093/jnci/dji242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Ledeganck KJ, Boulet GA, Bogers JJ, Verpooten GA, De Winter BY. The TRPM6/EGF pathway is downregulated in a rat model of cisplatin nephrotoxicity. PloS one. 2013;8:e57016. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Blanchard MG, Kittikulsuth W, Nair AV, de Baaij JH, Latta F, Genzen JR, et al. Regulation of Mg2+ Reabsorption and Transient Receptor Potential Melastatin Type 6 Activity by cAMP Signaling. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2015 doi: 10.1681/ASN.2014121228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Mastrototaro L, Trapani V, Boninsegna A, Martin H, Devaux S, Berthelot A, et al. Dietary Mg2+ regulates the epithelial Mg2+ channel TRPM6 in rat mammary tissue. Magnesium research : official organ of the International Society for the Development of Research on Magnesium. 2011;24:S122–129. doi: 10.1684/mrh.2011.0291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Lennon EJ, Piering WF. A comparison of the effects of glucose ingestion and NH4Cl acidosis on urinary calcium and magnesium excretion in man. The Journal of clinical investigation. 1970;49:1458–1465. doi: 10.1172/JCI106363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Blumberg D, Bonetti A, Jacomella V, Capillo S, Truttmann AC, Luthy CM, et al. Free circulating magnesium and renal magnesium handling during acute metabolic acidosis in humans. American journal of nephrology. 1998;18:233–236. doi: 10.1159/000013342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Nijenhuis T, Renkema KY, Hoenderop JG, Bindels RJ. Acid-base status determines the renal expression of Ca2+ and Mg2+ transport proteins. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006;17:617–626. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005070732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Wong NL, Quamme GA, Dirks JH. Effects of acid-base disturbances on renal handling of magnesium in the dog. Clinical science. 1986;70:277–284. doi: 10.1042/cs0700277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Lambers TT, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. Coordinated control of renal Ca2+ handling. Kidney international. 2006;69:650–654. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Lambers TT, Mahieu F, Oancea E, Hoofd L, de Lange F, Mensenkamp AR, et al. Calbindin-D28K dynamically controls TRPV5-mediated Ca2+ transport. The EMBO journal. 2006;25:2978–2988. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Vennekens R, Hoenderop JG, Prenen J, Stuiver M, Willems PH, Droogmans G, et al. Permeation and gating properties of the novel epithelial Ca(2+) channel. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:3963–3969. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.6.3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Yue L, Peng JB, Hediger MA, Clapham DE. CaT1 manifests the pore properties of the calcium-release-activated calcium channel. Nature. 2001;410:705–709. doi: 10.1038/35070596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Hoenderop JG, van der Kemp AW, Hartog A, van Os CH, Willems PH, Bindels RJ. The epithelial calcium channel, ECaC, is activated by hyperpolarization and regulated by cytosolic calcium. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 1999;261:488–492. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.1059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Nijenhuis T, Hoenderop JG, van der Kemp AW, Bindels RJ. Localization and regulation of the epithelial Ca2+ channel TRPV6 in the kidney. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2003;14:2731–2740. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000094081.78893.e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Song Y, Peng X, Porta A, Takanaga H, Peng JB, Hediger MA, et al. Calcium transporter 1 and epithelial calcium channel messenger ribonucleic acid are differentially regulated by 1,25 dihydroxyvitamin D3 in the intestine and kidney of mice. Endocrinology. 2003;144:3885–3894. doi: 10.1210/en.2003-0314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Van Cromphaut SJ, Dewerchin M, Hoenderop JG, Stockmans I, Van Herck E, Kato S, et al. Duodenal calcium absorption in vitamin D receptor-knockout mice: functional and molecular aspects. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:13324–13329. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231474698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Peng JB. TRPV5 and TRPV6 in transcellular Ca(2+) transport: regulation, gene duplication, and polymorphisms in African populations. Advances in experimental medicine and biology. 2011;704:239–275. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-0265-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Jang HR, Kim S, Heo NJ, Lee JH, Kim HS, Nielsen S, et al. Effects of thiazide on the expression of TRPV5, calbindin-D28K, and sodium transporters in hypercalciuric rats. Journal of Korean medical science. 2009;24(Suppl):S161–169. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2009.24.S1.S161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Nijenhuis T, Hoenderop JG, Loffing J, van der Kemp AW, van Os CH, Bindels RJ. Thiazide-induced hypocalciuria is accompanied by a decreased expression of Ca2+ transport proteins in kidney. Kidney international. 2003;64:555–564. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Lee CT, Shang S, Lai LW, Yong KC, Lien YH. Effect of thiazide on renal gene expression of apical calcium channels and calbindins. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2004;287:F1164–1170. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00437.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].de Groot T, Lee K, Langeslag M, Xi Q, Jalink K, Bindels RJ, et al. Parathyroid hormone activates TRPV5 via PKA-dependent phosphorylation. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20:1693–1704. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008080873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [112].van der Hagen EA, Tudpor K, Verkaart S, Lavrijsen M, van der Kemp A, van Zeeland F, et al. beta1-Adrenergic receptor signaling activates the epithelial calcium channel, transient receptor potential vanilloid type 5 (TRPV5), via the protein kinase A pathway. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:18489–18496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.491274. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Hoenderop JG, De Pont JJ, Bindels RJ, Willems PH. Hormone-stimulated Ca2+ reabsorption in rabbit kidney cortical collecting system is cAMP-independent and involves a phorbol ester-insensitive PKC isotype. Kidney international. 1999;55:225–233. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.00228.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Friedman PA, Coutermarsh BA, Kennedy SM, Gesek FA. Parathyroid hormone stimulation of calcium transport is mediated by dual signaling mechanisms involving protein kinase A and protein kinase C. Endocrinology. 1996;137:13–20. doi: 10.1210/endo.137.1.8536604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Cha SK, Wu T, Huang CL. Protein kinase C inhibits caveolae-mediated endocytosis of TRPV5. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2008;294:F1212–1221. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00007.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Kumar R, Schaefer J, Grande JP, Roche PC. Immunolocalization of calcitriol receptor, 24-hydroxylase cytochrome P-450, and calbindin D28k in human kidney. The American journal of physiology. 1994;266:F477–485. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.266.3.F477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Malloy PJ, Feldman D. Vitamin D resistance. The American journal of medicine. 1999;106:355–370. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Durmaz E, Zou M, Al-Rijjal RA, Bircan I, Akcurin S, Meyer B, et al. Clinical and genetic analysis of patients with vitamin D-dependent rickets type 1A. Clinical endocrinology. 2012;77:363–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2012.04394.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Kuro-o M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, et al. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. Nature. 1997;390:45–51. doi: 10.1038/36285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Torres PU, Prie D, Molina-Bletry V, Beck L, Silve C, Friedlander G. Klotho: an antiaging protein involved in mineral and vitamin D metabolism. Kidney international. 2007;71:730–737. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5002163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Chang Q, Hoefs S, van der Kemp AW, Topala CN, Bindels RJ, Hoenderop JG. The beta-glucuronidase klotho hydrolyzes and activates the TRPV5 channel. Science. 2005;310:490–493. doi: 10.1126/science.1114245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Wolf MT, An SW, Nie M, Bal MS, Huang CL. Klotho up-regulates renal calcium channel transient receptor potential vanilloid 5 (TRPV5) by intra- and extracellular N-glycosylation-dependent mechanisms. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2014;289:35849–35857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M114.616649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Alexander RT, Woudenberg-Vrenken TE, Buurman J, Dijkman H, van der Eerden BC, van Leeuwen JP, et al. Klotho prevents renal calcium loss. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20:2371–2379. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008121273. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Weinbaum S, Duan Y, Satlin LM, Wang T, Weinstein AM. Mechanotransduction in the renal tubule. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2010;299:F1220–1236. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00453.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Satlin LM, Carattino MD, Liu W, Kleyman TR. Regulation of cation transport in the distal nephron by mechanical forces. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2006;291:F923–931. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00192.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Liu W, Xu S, Woda C, Kim P, Weinbaum S, Satlin LM. Effect of flow and stretch on the [Ca2+]i response of principal and intercalated cells in cortical collecting duct. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2003;285:F998–F1012. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00067.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Woda CB, Leite M, Jr., Rohatgi R, Satlin LM. Effects of luminal flow and nucleotides on [Ca(2+)](i) in rabbit cortical collecting duct. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2002;283:F437–446. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00316.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Geyti CS, Odgaard E, Overgaard MT, Jensen ME, Leipziger J, Praetorius HA. Slow spontaneous [Ca2+] i oscillations reflect nucleotide release from renal epithelia. Pflugers Arch. 2008;455:1105–1117. doi: 10.1007/s00424-007-0366-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Praetorius HA, Leipziger J. Released nucleotides amplify the cilium-dependent, flow-induced [Ca2+]i response in MDCK cells. Acta Physiol (Oxf) 2009;197:241–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.2009.02002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Sipos A, Vargas SL, Toma I, Hanner F, Willecke K, Peti-Peterdi J. Connexin 30 deficiency impairs renal tubular ATP release and pressure natriuresis. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20:1724–1732. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008101099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Mamenko M, Zaika OL, Boukelmoune N, Berrout J, O'Neil RG, Pochynyuk O. Discrete control of TRPV4 channel function in the distal nephron by protein kinases A and C. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2013;288:20306–20314. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.466797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Mamenko M, Zaika O, Jin M, O'Neil RG, Pochynyuk O. Purinergic Activation of Ca-Permeable TRPV4 Channels Is Essential for Mechano-Sensitivity in the Aldosterone-Sensitive Distal Nephron. PLoSOne. 2011;6:e22824. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Zaika O, Mamenko M, Berrout J, Boukelmoune N, O'Neil RG, Pochynyuk O. TRPV4 dysfunction promotes renal cystogenesis in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2013;24:604–616. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2012050442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Nauli SM, Alenghat FJ, Luo Y, Williams E, Vassilev P, Li X, et al. Polycystins 1 and 2 mediate mechanosensation in the primary cilium of kidney cells. Nature genetics. 2003;33:129–137. doi: 10.1038/ng1076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Praetorius HA, Spring KR. Removal of the MDCK cell primary cilium abolishes flow sensing. J Membr Biol. 2003;191:69–76. doi: 10.1007/s00232-002-1042-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Praetorius HA, Spring KR. A physiological view of the primary cilium. Annual review of physiology. 2005;67:515–529. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.67.040403.101353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Rice WL, Van Hoek AN, Paunescu TG, Huynh C, Goetze B, Singh B, et al. High resolution helium ion scanning microscopy of the rat kidney. PloS one. 2013;8:e57051. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Mamenko M, Zaika O, O'Neil RG, Pochynyuk O. Ca2+ Imaging as a tool to assess TRP channel function in murine distal nephrons. Methods Mol Biol. 2013;998:371–384. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-351-0_29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Harris PC, Torres VE. Polycystic kidney disease. AnnuRevMed. 2009;60:321–337. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.60.101707.125712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Rossetti S, Consugar MB, Chapman AB, Torres VE, Guay-Woodford LM, Grantham JJ, et al. Comprehensive molecular diagnostics in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2007;18:2143–2160. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2006121387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Ward CJ, Hogan MC, Rossetti S, Walker D, Sneddon T, Wang X, et al. The gene mutated in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease encodes a large, receptor-like protein. Nature genetics. 2002;30:259–269. doi: 10.1038/ng833. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Torres VE, Wang X, Qian Q, Somlo S, Harris PC, Gattone VH., 2nd Effective treatment of an orthologous model of autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Nat Med. 2004;10:363–364. doi: 10.1038/nm1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Verani RR, Silva FG. Histogenesis of the renal cysts in adult (autosomal dominant) polycystic kidney disease: a histochemical study. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc. 1988;1:457–463. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Verani R, Walker P, Silva FG. Renal cystic disease of infancy: results of histochemical studies. A report of the Southwest Pediatric Nephrology Study Group. Pediatric nephrology. 1989;3:37–42. doi: 10.1007/BF00859623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Zerres K, Rudnik-Schoneborn S, Steinkamm C, Becker J, Mucher G. Autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Journal of molecular medicine. 1998;76:303–309. doi: 10.1007/s001090050221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Gallagher AR, Germino GG, Somlo S. Molecular advances in autosomal dominant polycystic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2010;17:118–130. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2010.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Nauli SM, Rossetti S, Kolb RJ, Alenghat FJ, Consugar MB, Harris PC, et al. Loss of polycystin-1 in human cyst-lining epithelia leads to ciliary dysfunction. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006;17:1015–1025. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005080830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Yamaguchi T, Hempson SJ, Reif GA, Hedge AM, Wallace DP. Calcium restores a normal proliferation phenotype in human polycystic kidney disease epithelial cells. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2006;17:178–187. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2005060645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Yang J, Zhang S, Zhou Q, Guo H, Zhang K, Zheng R, et al. PKHD1 gene silencing may cause cell abnormal proliferation through modulation of intracellular calcium in autosomal recessive polycystic kidney disease. Journal of biochemistry and molecular biology. 2007;40:467–474. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2007.40.4.467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Xu C, Shmukler BE, Nishimura K, Kaczmarek E, Rossetti S, Harris PC, et al. Attenuated, flow-induced ATP release contributes to absence of flow-sensitive, purinergic Cai2+ signaling in human ADPKD cyst epithelial cells. American journal of physiology Renal physiology. 2009;296:F1464–1476. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90542.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]