Abstract

To evaluate the results from patients who underwent arthroscopic debridement of extensive irreparable rotator cuff injuries. Methods: 27 patients were operated between 2003 and 2007, and 22 of them were evaluated. The surgical procedure consisted of arthroscopic debridement of the stumps of the tendons involved, bursectomy, removal of acromial osteophytes and, possibly, biceps tenotomy and tuberoplasty. Results: All the patients showed involvement of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons at the preoperative stage. In the postoperative evaluation, 14 patients had a complete teres minor muscle, and three had partial tears of the subscapularis tendon. There was an improvement in the UCLA criteria, from 15 preoperatively to 31 postoperatively. There was no improvement in muscle strength, but there was a reduction in the pain. Conclusion: Arthroscopic debridement is a recommended procedure for elderly patients with irreparable rotator cuff tears, good range of motion and low functional demand, when the main objective is to diminish pain.

Keywords: Debridement, Arthroscopy, Rotator Cuff, Bursitis

INTRODUCTION

Arthroscopic treatment of rotator cuff tears has been evolving over the years, not only through better knowledge of the physiopathology but also through more refined surgical methods. Nonetheless, there is still much controversy regarding situations of extensive irreparable rotator cuff lesions.

Extensive lesions are defined as those that are larger than 5 cm, with involvement of at least two tendons(1). They are irreparable when they cannot be repaired during that surgical procedure, either because of major retraction of the stumps or because of the poor quality of the tendons(2).

The literature offers a veriety of choices for treating these lesions, such as conservative treatment with analgesics, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, infiltration of corticosteroids, physiotherapy to strengthen anterior deltoid and active and assisted exercises3, 4, 5. The surgical options include subacromial debridement with or without tenotomy or tenodesis of the long head of the biceps6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, partial repair14, 15, myotendinous transfers16, 17, 18 and prosthetic replacement19, 20.

Arthroscopic debridement is indicated for patients with extensive and irreparable tears and for elderly individuals with low functional demands whose preoperative shoulder mobility was good. In addition, this is a surgical procedure in which improvements in pain are sought, but without improvements in strength.

The aim of this study was to functionally evaluate patients who had undergone arthroscopic debridement of extensive irreparable rotator cuff lesions, with or without tenotomy of the long head of the biceps, and in some cases, with tuberoplasty as recommended by Fenlin et al(21).

MATERIAL AND METHODS

Between 2003 and 2007, 27 patients with extensive irreparable rotator cuff tears underwent operations, and 22 of these were evaluated in this study (seven men and 15 women, with a mean age of 69 years (range: 50 to 84). The dominant side was involved in 17 patients.

Patients who had previously undergone surgery on the affected shoulder, those with clinical and imaging signs of glenohumeral arthrosis and those who underwent partial or total repair of the rotator cuff during the surgical procedure were excluded.

Prior conservative treatment was performed for at least six months, consisting of physiotherapy, analgesics and anti-inflammatory drugs, along with corticosteroid infiltration when indicated. The diagnosis of extensive irreparable tear was made by means of clinical examination, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and incapacity to repair these lesions during the surgical procedure. During the clinical examination, all the patients presented signs of impact and diminished strength in the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, without muscle atrophy but with hypotrophy of the suprascapular and infrascapular fossa in some patients. We used the UCLA evaluation criteria.

MRI was performed on all the patients before the operation and on 16 patients after the operation. We evaluated the degrees of atrophy, fatty degeneration and tendon retraction, in accordance with Thomazeau et al(22), Goutallier et al(23) and Patte(2), respectively.

The arthroscopy procedure followed the usual patterns, with viewing through a posterior port and instrumentation through anterior and lateral ports. Firstly, the glenohumeral joint was evaluated with the aim of identifying labral or degenerative abnormalities of the joint itself, rotator cuff tears and the quality of the long head of the biceps. Tenotomy was performed when one of the following criteria was fulfilled: synovitis, lesion greater than 50% of the total thickness, subluxation or dislocation. Tenodesis was not performed in any case.

In the subacromial space, the following were then performed: bursectomy, partial synovectomy, viewing of the lesions, debridement of the avascular area of the tendons involved and excision of the subacromial spur when present. Acromioplasty was not performed in any of the patients, since it was important to maintain the coracoacromial arch for this type of lesion, thereby impeding further ascension of the humeral head. Resection of the distal clavicle was also not performed in any case.

All the tendons were previously tested regarding their reducibility and whether they were friable. Only after this procedure were they classified as irreparable. Tuberoplasty was performed when there were signs of subacromial impact, exostosis on the greater tuberosity and significant reduction of the subacromial space.

Radiographs were performed after the operation in true AP view and lateral scapular view in order to observe whether there was any glenohumeral arthrosis or ascension of the humeral head, in accordance with the criteria of Hamada et al(24). Postoperative MRI had the aim of evaluating the involvement of other tendons and whether there was any increase in atrophy and in the degree of fatty degeneration.

During the immediate postoperative period, the patients' affected arm was kept in a Velpeau sling for comfort and pain relief. Self-administered passive exercises for the shoulder and elbow were started 24 hours after the surgery and the stitches were removed seven days after the surgery. Muscle strengthening with physiotherapeutic guidance was started two weeks after the surgery. All the patients were asked to give their subjective assessment of the degree of satisfaction: they were asked whether they were very satisfied, satisfied, disappointed or dissatisfied.

RESULTS

After a mean follow-up of 27 months (range: eight to 60 months), 22 out of the 27 patients were evaluated (Tables 1 and 2). There was an improvement in the UCLA criteria, going from a mean of 15 before the operation to 31 after the operation; 81.81% of the results were excellent and good, 18.19% were reasonable and none were poor.

Table 1.

Patients evaluated.

| Range of motion |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number | Biceps tenotomy | Muscle strength | Satisfaction | Postoperative Hamada | Magnetic resonance imaging – teres minor | Type of acromion | EA | External rotation | Internal rotation |

| 1 | Yes | R | Very satisfied | 1 | Normal | Straight | 180 | 45 | T7 |

| 2 | No | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Normal | Curved | 160 | 60 | T10 |

| 3 | Yes | R | Satisfied | 2 | Normal | Curved | 150 | 40 | T11 |

| 4 | No | R | Very satisfied | 1 | Normal | Hooked | 180 | 30 | T10 |

| 5 | Yes | R | Satisfied | 3 | Normal | Curved | 130 | 50 | L1 |

| 6 | No | R | Satisfied | 2 | Slight degeneration and atrophy | Hooked | 170 | 60 | T10 |

| 7 | No | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Hooked | 160 | 40 | T12 | |

| 8 | No | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Normal | Curved | 150 | 30 | T7 |

| 9 | Yes | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Normal | Hooked | 170 | 50 | T7 |

| 10 | Yes | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Normal | Curved | 120 | 40 | L4 |

| 11 | Yes | R | Satisfied | 2 | Normal | Curved | 180 | 90 | T7 |

| 12 | No | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Normal | Curved | 150 | 60 | T10 |

| 13 | Yes | Equal | Very satisfied | 1 | Curved | 180 | 60 | T7 | |

| 14 | No | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Normal | Hooked | 180 | 50 | T7 |

| 15 | Yes | Equal | Very satisfied | 3 | Normal | Straight | 180 | 60 | T12 |

| 16 | Yes | Equal | Very satisfied | 2 | Atrophy and fatty degeneration | Curved | 180 | 50 | T9 |

| 17 | No | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Normal | Curved | 180 | 30 | T7 |

| 18 | Yes | R | Disappointed | 2 | Normal | Curved | 150 | 50 | L2 |

| 19 | No | R | Very satisfied | 1 | Straight | 180 | 60 | T7 | |

| 20 | Yes | R | Very satisfied | 2 | Curved | 120 | 10 | T7 | |

| 21 | Yes | R | Very satisfied | 3 | Curved | 180 | 45 | T7 | |

| 22 | Nao | D | Very satisfied | 1 | Straight | 180 | 10 | T7 | |

Table 2.

Patients evaluated

| Number | Age | Sex | Occupation | Side affected/dominant side | Tendons involved | Follow-up (months) | Preoperative UCLA | Postoperative UCLA | Popeye |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 57 | M | Retired | R / R | SE / IE | 8 | 9 | 34 | Yes |

| 2 | 77 | F | Retired | R / R | SE / IE | 44 | 22 | 32 | No |

| 3 | 76 | F | Retired | R / R | SE / IE | 44 | 5 | 29 | No |

| 4 | 50 | F | Housewife | R / R | SE / IE | 22 | 15 | 31 | No |

| 5 | 79 | F | Housewife | R / R | SE / IE | 51 | 12 | 25 | Yes |

| 6 | 78 | F | Retired | R / R | SE / IE | 58 | 15 | 32 | No |

| 7 | 65 | F | Auxiliary | R / R | SE / IE | 24 | 16 | 26 | No |

| 8 | 66 | F | Auxiliary | R / R | SE / IE | 27 | 22 | 30 | No |

| 9 | 51 | M | Driver | R / R | SE / IE | 11 | 16 | 34 | Yes |

| 10 | 71 | M | Retired | L / R | SE / IE | 8 | 12 | 27 | Yes |

| 11 | 63 | M | Driver | L / R | SE / IE | 10 | 11 | 34 | Yes |

| 12 | 70 | F | Retired | R / R | SE / IE | 60 | 10 | 25 | No |

| 13 | 78 | F | Housewife | L / R | SE / IE | 29 | 15 | 35 | No |

| 14 | 69 | F | Seamstress | L / R | SE / IE | 35 | 15 | 30 | No |

| 15 | 60 | M | Small trader | R / R | SE / IE | 11 | 27 | 35 | No |

| 16 | 70 | F | Housewife | R / R | SE / IE | 8 | 12 | 32 | No |

| 17 | 80 | F | Retired | R / R | SE / IE | 45 | 17 | 34 | No |

| 18 | 67 | M | Retired | L / R | SE / IE | 23 | 16 | 28 | No |

| 19 | 65 | M | Retired | R / R | SE / IE | 27 | 17 | 29 | No |

| 20 | 80 | F | Housewife | R / R | SE / IE | 12 | 8 | 29 | No |

| 21 | 59 | F | Housewife | R / R | SE / IE | 10 | 15 | 34 | No |

| 22 | 80 | F | Housewife | R / R | SE / IE | 18 | 18 | 34 | No |

We did not find any difference in the results in evaluations on the patients in relation to age, sex or profession. The dominant side was involved in 17 patients.

With regard to the degree of satisfaction, 21 patients were satisfied or very satisfied and none of them were dissatisfied, although one patient was disappointed.

Muscle strength was diminished in 19 patients and maintained in three, while there were no cases of increased muscle strength.

The mean external rotation was 47° and the mean anterior elevation was 164°. A postoperative view of a patient's right shoulder is shown in (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Postoperative view of a patient's right shoulder.

Twelve tenotomy procedures were performed on the long head of the biceps, and the Popeye deformity was present in five cases, but without complaints relating to this deformity or loss of strength.

The suprascapular tendon was torn in all the patients, presenting grade 3 retraction, according to Patte. The infrascapular tendon was also involved in all patients.

MRI before the surgery did not identify any lesions in the subscapularis or teres minor, but the postoperative MRI evaluation showed seven cases of tendinopathy and three partial tears of the subscapularis. There were also two patients with slight atrophy and fatty degeneration of the teres minor.

We also found fatty degeneration in the 16 patients evaluated using MRI, of whom nine presented Goutalier

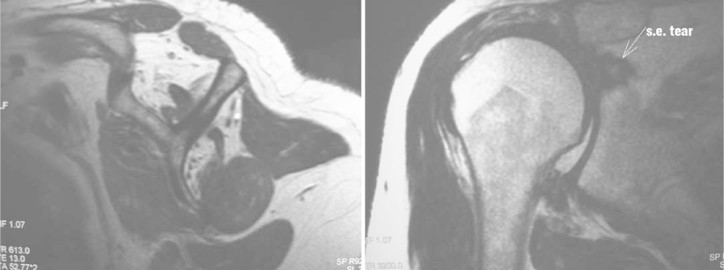

IV and seven, Goutalier III. In addition, we also found atrophy of the muscle belly of the suprascapularis of Thomazeau type C in 10 patients and type B in six, in preoperative MRI (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Sagittal and coronal sections from magnetic resonance imaging showing atrophy of the suprascapular tendon with fatty infiltration and complete tear, with retraction at the level of the glenoid and ascension of the humeral head.

Using the Hamada criteria, the radiographs showed five patients with grade 1, 14 with grade 2 and three with grade 3. We did not find any cases of grade 4 or 5.

DISCUSSION

Rotator cuff injuries usually occur in elderly patients, either traumatically or non-traumatically. They are generally asymptomatic and do not cause much functional limitation. When symptomatic, they started to be a major problem for these patients, since they interfere particularly with sleep and with activities of daily living.

The initial treatment should always be conservative, with pain control, stretching exercises and muscle strengthening exercises, as recommended by Rockwood in his classic rehabilitation program known as “orthotherapy”(8).

Specifically for extensive lesions, conservative treatment with rehabilitation and strengthening of the anterior deltoid should be attempted before implementing any surgical procedure, as advised very well by Levy et al(3).

If this treatment fails, surgical treatment will be indicated. Specifically for the elderly age group, there are some particular features relating to rotator cuff injuries and to the patients themselves: the tears presented are generally chronic, with a high degree of tendon retraction, very friable tissue, muscle atrophy and fatty replacement, which generally leads to non-consolidation of these lesions.

Furthermore, since these are patients with low functional demands, good surgical results are mainly measured in terms of pain relief. Thus, arthroscopic debridement becomes a good surgical option for such patients, particularly with this tear pattern, since it is a rapid procedure with low morbidity that does not deinsert the deltoid. It presents low infection rates and allows rehabilitation to start early.

Our clinical results showed that the patients presented a good response to treatment, with a significant improvement in the UCLA criteria. Only one patient was disappointed with the surgical result, because in that case there was no improvement in the state of pain and the range of motion presented was not good.

One important finding that we noted, which is also in agreement with the literature except for the study by Liem et al(25), was that muscle strength was not recovered in 19 patients. This was an expected result, because of the injury pattern and the patients' ages, and therefore all the patients were informed before the surgery that this could occur.

In view of the low functional demands of these patients, we consider that the results were satisfactory, since what was proposed through the treatment was achieved, i.e. there were improvements in all the parameters analyzed. We agree with some authors' affirmations that they did not know how long these good results would be maintained.

On the other hand, we could see during the follow-up that some patients were being monitored for 60 months without any deterioration in their clinical condition. Zvijac et al(7) showed in their study that there was a worsening of the clinical condition with the passing of the years. This is a point that still deserves to be analyzed and discussed.

Twelve tenotomy procedures were performed on the long head of the biceps, following the criteria described earlier. We observed that the Popeye deformity was present in less than 50% of the cases. This confirms that even in cases of extensive lesions, auto-tenodesis of the long head of the biceps may occur in the bicipital groove, provided that the transverse humeral ligament is complete, since the groove is usually narrower than the intra-articular portion of the tendon.

We did not observe any clinical changes to the elbow supination and flexion strength of these patients who had undergone tenotomy, compared with those without tenotomy. Moreover, there were also no complaints regarding esthetics among the patients who presented the Popeye deformity, perhaps because of their age or because cosmetic appearance was unimportant for their aims in life.

We took great care in comparing MRI before and after the surgery, especially in relation to the tendons involved. We think that our sample may have presented some bias, given that all the patients only presented suprascapular or infrascapular lesions before the operation. However, comparing our sample with that of Fenlin et al(21), we observed that their sample also only presented suprascapular and infrascapular lesions in 18 of the 19 patients evaluated using MRI.

On the other hand, this allowed us to give emphasis to evaluating the teres minor, since we agree with the hypothesis described by Burkhart(26), who stated that provided that the anterior rotator cuff (subscapular) and the posterior rotator cuff (infrascapular and teres minor) were counterbalanced, it would be possible to have an “anatomically deficient yet biomechanically intact lesion”.

Since there was an infrascapular lesion in all the patients evaluated, the external rotator consisted only of the teres minor. Nonetheless, the mean external rotation observed after the operation was 47°.

Thus, Burkhart's theory was in line with the good results, since we treated the extensive lesions and their respective causes of pain (synovitis, unstable edges of the rotator cuff, bursitis, bicipital tendinitis and free bodies) only by means of arthroscopic debridement, and we made use of the biomechanical stability of the lesion to implement good rehabilitation, through a well guided and directed program for deltoid strengthening.

We produced radiographs after the operation to evaluate whether the patients had evolved with arthropathy of the rotator cuff and subsequently with arthrosis of the glenohumeral joint, given that this was quite likely to occur because the tendons were torn and the joint was theoretically unstable.

None of the patients evolved with arthrosis or necrosis of the humeral head, which would be, respectively, Hamada grades 4 and 5. The maximum observed was Hamada grade 3.

This observation serves to confirm again that provided that the shoulders are biomechanically stable and even in situations of extensive lesions, there is no overload or harm to the joint.

Tuberoplasty as described by Fenlin was not performed on all the patients. The best indication for this procedure is among patients who present a greatly reduced subacromial space because of ascension of the humeral head, for whom it is desired to create congruence between the acromion and the greater tuberosity. Thus, we only performed tuberoplasty on two of the three patients presenting Hamada grade 3.

CONCLUSION

Elderly patients with low functional demands, who present a main complaint of pain and have not responded to conservative treatment for their condition of extensive irreparable rotator cuff injury, yet present a biomechanically stable shoulder, are good candidates for arthroscopic debridement. Subsequent assessment to ascertain whether the good immediate response is maintained over the long term is necessary.

Footnotes

Work performed at Hospital Mater Dei and IPSEMG, Belo Horizonte, MG.

Declaramos inexistência de conflito de interesses neste artigo

REFERENCES

- 1.DeOrio JK, Cofield RH. Results of a second attempt at surgical repair of a failed initial rotator-cuff repair. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(4):563–567. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Patte D. Classification of rotator cuff lesions. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(254):254–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levy O, Mullett H, Roberts S, Copeland S. The role of anterior deltoid reeducation in patients with massive irreparable degenerative rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(6):863–870. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lech O, Valenzuela NC, Severo A. Tratamento conservador das lesões parciais e completas do manguito rotador. Acta Ortop Bras. 2000;8(3):144–156. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zingg PO, Jost B, Sukthankar A, Buhler M, Pfirrmann CW, Gerber C. Clinical and structural outcomes of nonoperative management of massive rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(9):1928–1934. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.01073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burkhart SS. Arthroscopic treatment of massive rotator cuff tears. Clinical results and biomechanical rationale. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1991 Jun;(267):45–56. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zvijac JE, Levy HJ, Lemak LJ. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression in the treatment of full thickness rotator cuff tears: a 3- to 6-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(5):518–523. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rockwood CA, Jr, Williams GR, Jr, Burkhead WZ., Jr Débridement of degenerative, irreparable lesions of the rotator cuff. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77(6):857–866. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199506000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Levy HJ, Gardner RD, Lemak LJ. Arthroscopic subacromial decompression in the treatment of full-thickness rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1991;7(1):8–13. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90071-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Scheibel M, Lichtenberg S, Habermeyer P. Reversed arthroscopic subacromial decompression for massive rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2004;13(3):272–278. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Boileau P, Baqué F, Valerio L, Ahrens P, Chuinard C, Trojani C. Isolated arthroscopic biceps tenotomy or tenodesis improves symptoms in patients with massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(4):747–757. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.01097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Checchia SL, Doneux PS, Miyazaki AN, Fregoneze M, Silva LA, Oliveira FM. Tenotomia artroscópica do bíceps nas lesões irreparáveis do manguito rotador. Rev Bras Ortop. 2003;38(9):513–521. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zoppi AF, Kikuta FK, Pereira LAR, Zan RA. Treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears by arthroscopy dèbridement. In: 10th International Congress of Shoulder and Elbow Surgery. Brazil, Setembro, 2007

- 14.Burkhart SS, Nottage WM, Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Kohn HS, Pachelli A. Partial repair of irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(4):363–370. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80186-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duralde XA, Bair B. Massive rotator cuff tears: the result of partial rotator cuff repair. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2005;14(2):121–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warner JJ. Management of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears: the role of tendon transfer. Instr Course Lect. 2001;50:63–71. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iannotti JP, Hennigan S, Herzog R, Kella S, Kelley M, Leggin B. Latissimus dorsi tendon transfer for irreparable posterosuperior rotator cuff tears. Factors affecting outcome. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(2):342–348. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.D.02996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerber C, Maquieira G, Espinosa N. Latissimus dorsi transfer for the treatment of irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(1):113–120. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.E.00282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frankle M, Levy JC, Pupello D, Siegal S, Saleem A, Mighell M. The reverse shoulder prosthesis for glenohumeral arthritis associated with severe rotator cuff deficiency. a minimum two-year follow-up study of sixty patients surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88(Suppl 1 Pt 2):178–190. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wall B, Nové-Josserand L, O'Connor DP, Edwards TB, Walch G. Reverse total shoulder arthroplasty: a review of results according to etiology. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89(7):1476–1485. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fenlin JM, Jr, Chase JM, Rushton SA, Frieman BG. Tuberoplasty: creation of an acromiohumeral articulation-a treatment option for massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11(2):136–142. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.121764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thomazeau H, Boukobza E, Morcet N, Chaperon J, Langlais F. Prediction of rotator cuff repair results by magnetic resonance imaging. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997;(344):344–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goutallier D, Postel JM, Bernageau J, Lavau L, Voisin MC. Fatty muscle degeneration in cuff ruptures. Pre- and postoperative evaluation by CT scan. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;(304):304–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hamada K, Fukuda H, Mikasa M, Kobayashi Y. Roentgenographic findings in massive rotator cuff tears. A long-term observation. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1990;(254):254–256. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liem D, Lengers N, Dedy N, Poetzl W, Steinbeck J, Marquardt B. Arthroscopic debridement of massive irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(7):743–748. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Burkhart SS. Reconciling the paradox of rotator cuff repair versus debridement: a unified biomechanical rationale for the treatment of rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy. 1994;10(1):4–19. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(05)80288-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]