Abstract

Objective: To evaluate patients affected by osteochondral fractures of the talus who were treated surgically by means of arthroscopy-assisted microperforation. Methods: A retrospective study was carried out on 24 patients with osteochondral lesions of the talus who underwent microperforation assisted by videoarthroscopy of the ankle. They were evaluated using the American Orthopaedic Foot and Ankle Society (AOFAS) score system before and after the operation. Results: There were 19 men and 5 women, with a mean age of 35.3 years (minimum of 17 years and maximum of 54 years). The minimum follow-up was two years (maximum of 39 months). All the patients showed an improvement in AOFAS score after surgery, with an average improvement of around 22.5 points. Conclusion: Videoarthroscopy-assisted microperforation is a good option for treating osteochondral lesions of the talus and provides good functional results.

Keywords: Osteochondral, Talus/injuries, Talus/surgery, Arthroscopy, Ankle

INTRODUCTION

The evolution of orthopedics produced the development of minimally invasive surgical techniques for the diagnosis and treatment of orthopedic pathologies. Arthroscopic surgery of the ankle allows the approach to intra-articular structures without extensive incisions, increasing the diagnostic capacity and allowing the execution of less aggressive surgical correction techniques.

Munro(1), in 1856, was the first author to describe the existence of free bodies in the ankle joint. Barth(2), in 1898, considered the osteochondral lesion of the talus as being an intra-articular fracture. Kappis(3) used the term “osteochondritis dissecans of the talus” for the first time in 1922. Berndt and Harty(4) suggested that the name “transchondral fracture” would be the best definition, both from the etiological and from the pathophysiological point of view. Ferkel et al(5) introduced the term “osteochondral lesions of the talus” (OLT) as the most appropriate for describing chondral lesions that involve the articular surface of the talus.

There is a difference of opinion among the authors regarding the location and frequency of chondral lesions of the talus. Berndt and Harty(4) and Roach and Frost(6) suggest that osteochondral lesions of the talus occur in two areas of the talar dome: the anterolateral region and the posteromedial region. Elias et al(7) divided the talar dome into nine zones and suggested that the most severely affected zones would be zone 4 (medial and central) and, in second place, zone 6 (mid-lateral). Medial lesions, besides being more frequent, are also larger and deeper than lateral lesions. Fractures of the lateral portion of the talar dome occur when inversion force affects the foot in dorsiflexion, while fractures of the medial portion are produced upon inversion on the foot in equinus(4).

Clinically, patients with osteochondral lesions of the talus refer to nonspecific pains of low intensity involving the ankle joint. They also report edema, clicking, blocks and a buckling sensation in the affected ankle. A previous history of traumatism involving the ankle joint is common in most cases. Regarding the physical examination, patients generally present medial or lateral hypersensitivity in the ankle accompanied by limitation of range of motion and edema, and may present signs of ankle instability(8).

The diagnosis of osteochondral lesions of the talus requires a high suspicion rate. The period between the onset of symptoms and the definitive diagnosis can range from four months to up to two years9, 10. In many cases, the radiological alterations are slight and only appear some months after the onset of the symptoms. Nowadays, computed tomography and particularly nuclear magnetic resonance of the ankle are essential in the early diagnosis of osteochondral lesions of the talus8, 11, 12. The osteochondral lesion is classified radiologically, according to Berndt and Harty(4), in four stages: I – small area of compression of subchondral bone; II – partially detached osteochondral fragment; III – completely detached osteochondral fragment; IV – displaced osteochondral fragment(4).

The treatment of osteochondral lesion of the talus can be a major challenge due to the low intrinsic reparability of the articular damage(13). Most authors defend surgical treatment as the most appropriate means of treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus9, 14, 15, 16, while some still believe that the conservative treatment is the best conduct to be employed(17). In this context, videoarthroscopy of the ankle offers an adequate treatment with lower morbidity and an accelerated return to sports and daily activities(8), besides offering the chance of a careful articular inspection and lavage after the procedure for removal of loose debris(18).

During the videoarthroscopy procedure, Van Bergen et al(18) suggest that the treatment of osteochondral lesion defects smaller than 15 mm be executed by debridement and stimulation of the spongy bone. For cystic lesions, retrograde drilling associated with bone graft is a good alternative. Osteochondral autograft or autologous chondrocyte implantation are recommended for secondary cases, as well as for larger lesions. Takao et al(19) propose the same procedure. Giza et al(13) also use the autologous chondrocyte graft, but in the treatment of patients who do not respond to curettage of the cyst and subsequent microperforations. Nery and Carneiro(15) carry out the same procedure as an alternative method in cases in which the patient continues with complaints after the conservative or surgical treatment, also with good results.

More recently, Nery et al(20) analyzed the results of autologous chondrocyte implantation in patients submitted to previous surgical treatment without the obtainment of satisfactory results in terms of healing of the lesion and the remission of symptoms. The authors noted that autologous chondrocyte implantation is a safe and effective method for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Cohen et al(21) also present autologous chondrocyte implantation as a promising technique for chondral lesions of the knee and of the talus. Other authors still advocate the use of mosaicplasty(22) or fresh talus allograft(23). Gras et al(24) propose the use of navigation in association with arthroscopy aiming to improve the accuracy of the retrograde perforation of cystic osteochondral lesions.

The objective of this study is to evaluate patients with osteochondral lesion of the talus treated with videoarthroscopy-guided microperforations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A retrospective study was conducted with 24 patients affected by osteochondral lesion of the talus submitted to ankle arthroscopy-assisted microperforations between August 2007 and December 2009. All the patients were operated by the same surgeon at the Instituto de Ortopedia e Traumatologia de Passo Fundo, Rio Grande do Sul. The preoperative evaluation was based on the review of medical records and on interviews with the patients in routine reviews in the postoperative period. All the patients presented a profile of pain in the ankle and limitation of their daily and sports activities for more than three months, prior to the surgical treatment, and they all reported previous trauma.

All the patients were evaluated through anteroposterior, lateral and oblique radiographies (Figure 1) and by nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) (Figure 2). The scoring system of the American Orthopaedic Foot & Ankle Society (AOFAS)(25)was used for the functional evaluation of results.

Figure 1.

Anteroposterior, lateral and oblique radiographies showing minimum alteration of the medial portion of the talus.

Figure 2.

Magnetic resonance imaging in coronal and sagittal to axial cross sections showing the osteochondral lesion in the mid-medial aspect of the talus.

SURGICAL TECHNIQUE

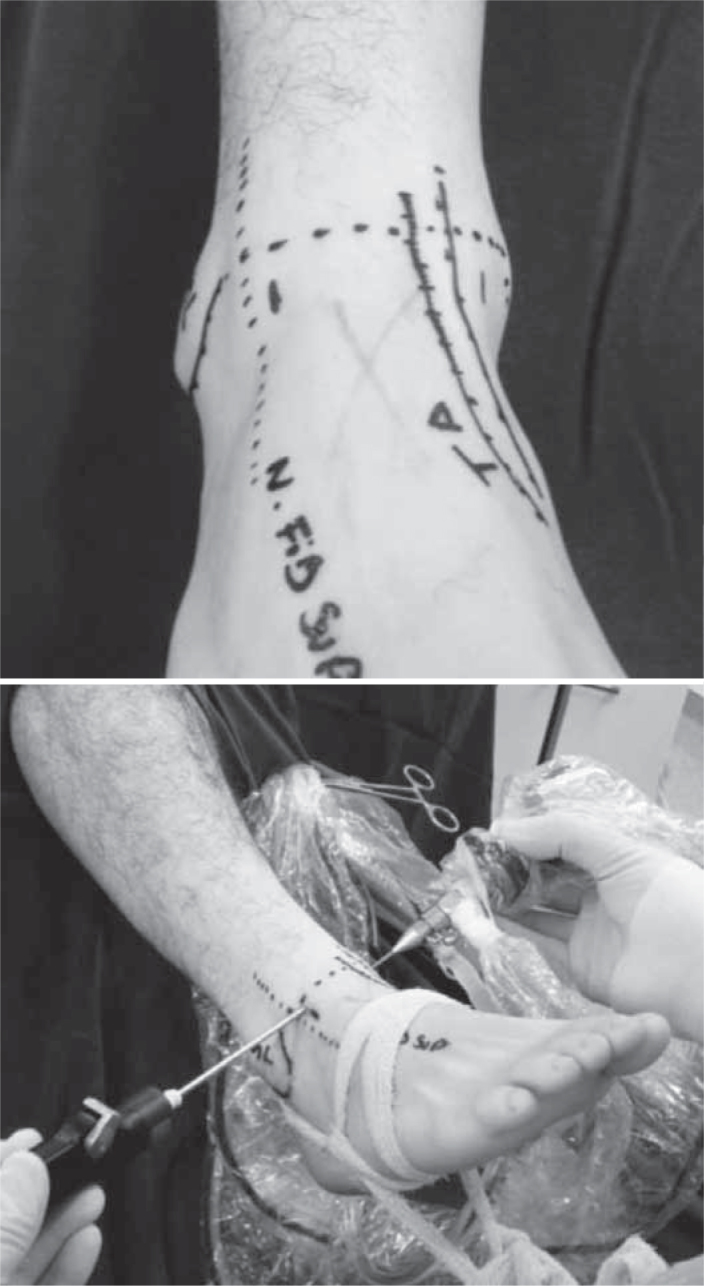

As regards anesthesia, the patients were submitted to epidural block or general anesthesia. A tourniquet was applied in the proximal region of the thigh and the lower limb was positioned in a leg holder. The ankle arthroscopy was executed through the anteromedial and anterolateral portals (Figure 3)(14). The surgeon used a scope with a diameter of 2.9 mm and 30° of angulation, accompanied by a compatible cannula for visualization of the articular compartment. The evaluation of the cartilage condition was performed by direct visualization and through the use of a probe for palpation and evaluation of its integrity. A grasper is used to remove fragments and articular debris. The procedure was executed with cutaneous traction, without a distractor, performed by manual traction.

Figure 3.

Positioning of the anteromedial and anterolateral portals.

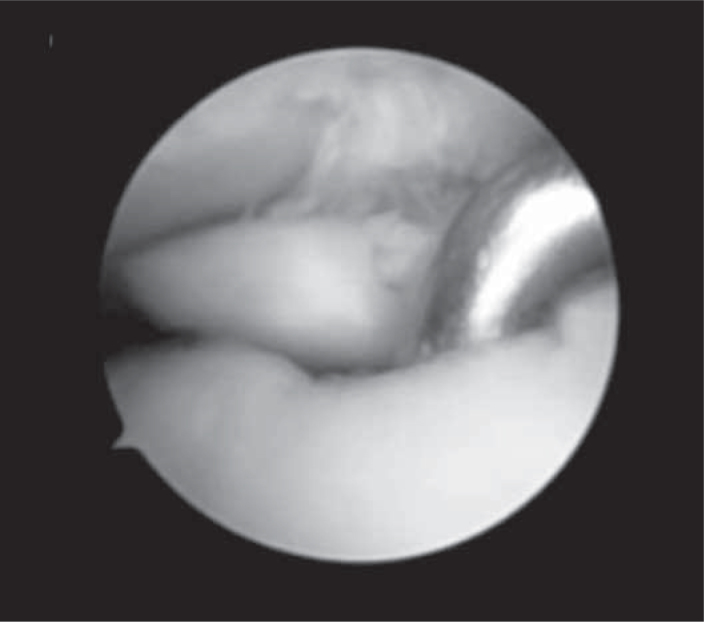

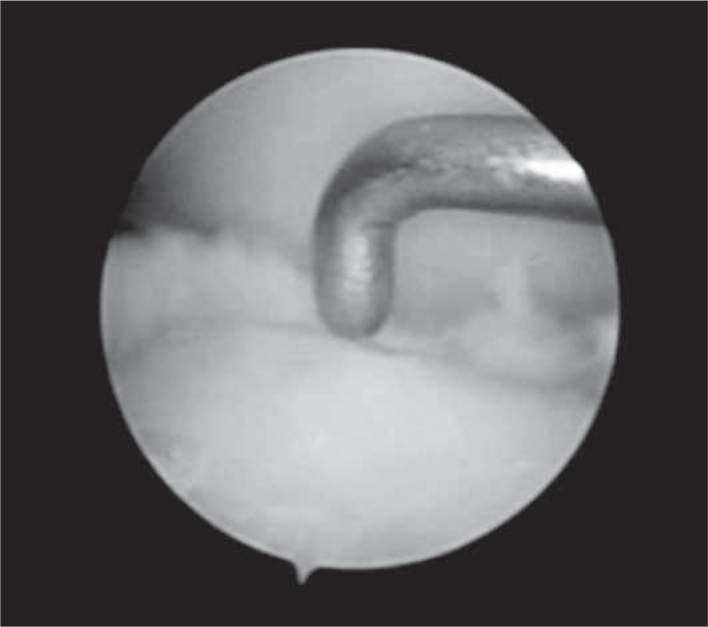

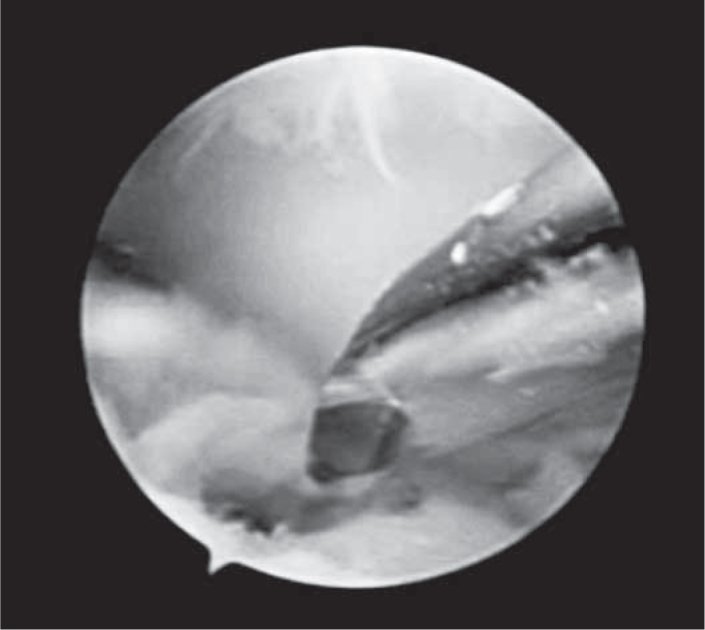

Introduction of the arthroscopy instruments was followed by an inspection of the ankle joint and an analysis of the conditions of the articular cartilage adjoining the lesion (Figure 4). After drying all the loose cartilage fragments, the surgeon performed the curettage of the lesion (Figure 5). The microperforations were made with the help of a Kirschner wire or 1.5 mm drill at low rotation (Figure 6). The tourniquet was released after the complete performance of perforations to visualize whether the bleeding at the lesion site was satisfactory (Figure 7). After closing the portals, an occlusive dressing was applied in all the cases. The patients were kept without load for 45 days, but with early mobility through passive and active exercises since the immediate postoperative period.

Figure 4.

Osteochondral lesion.

Figure 5.

Osteochondral lesion after debridement.

Figure 6.

Perforations of the lesion.

Figure 7.

Final appearance after perforations.

RESULTS

The study group consisted of 19 men and five women, with mean age of 35.3 years (minimum of 17 and maximum of 54), with minimum follow-up of two years (maximum of 39 months). Nineteen patients (79.2%) reported ankle sprain, but were unable to define the sprain mechanism. The right side was the most affected (70.8%) (Table 1). None of the patients presented type I lesion according to the classification of Berndt and Harty(4), while 50.0% presented type II, 41.7% type III and 8.3% type IV.

Table 1.

Distribution of the analyzed patients.

| N□ | Sex | Age | Side | Lesion mechanism | Lesion site (zone) | Classification | Follow-up (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | M | 38 | Right | Sprain | 4 | II | 38 |

| 2 | M | 33 | Left | Sprain | 4 | III | 24 |

| 3 | F | 35 | Right | Sprain | 3 | II | 39 |

| 4 | M | 26 | Right | Sprain | 7 | III | 24 |

| 5 | M | 47 | Left | Sprain | 4 | III | 30 |

| 6 | M | 28 | Left | Sprain | 6 | IV | 25 |

| 7 | M | 36 | Right | Sprain | 4 | II | 38 |

| 8 | M | 34 | Right | Sprain | 6 | III | 24 |

| 9 | M | 42 | Right | Fracture | 6 | II | 24 |

| 10 | M | 47 | Right | Sprain | 4 | II | 24 |

| 11 | M | 24 | Right | Sprain | 4 | III | 24 |

| 12 | M | 39 | Right | Sprain | 7 | II | 20 |

| 13 | M | 56 | Left | Sprain | 4 | II | 24 |

| 14 | F | 20 | Right | Sprain | 4 | II | 24 |

| 15 | F | 54 | Right | Sprain | 4 | III | 24 |

| 16 | M | 38 | Right | Sprain | 4 | II | 29 |

| 17 | F | 35 | Left | Sprain | 3 | III | 33 |

| 18 | F | 20 | Left | Sprain | 4 | III | 24 |

| 19 | M | 38 | Right | Sprain | 4 | IV | 26 |

| 20 | M | 17 | Right | Fracture | 6 | III | 24 |

| 21 | M | 29 | Left | Sprain | 4 | III | 24 |

| 22 | M | 36 | Right | Fracture | 6 | II | 32 |

| 23 | M | 40 | Right | Sprain | 6 | II | 24 |

| 24 | M | 36 | Right | Sprain | 4 | II | 24 |

Mean follow-up – 27 months; Mean age – 35 years; Women – 20.8%, Men – 79.2% Right side – 70.8%; Left side – 29.2%

Lesion: zone 3 (8.3%), 4 (58.4%), 6 (25.0%), 7 (8.3%)

Classification: II (50.0%), III (41.7%), IV (8.3%)

Considering the matrix described by Elias et el(7), we observed 14 patient (58.4%) with lesions in zone 4 (mid-medial), six patients (25.0%) in zone 6 (mid-lateral), two patients (8.3%) in zone 3 (anterolateral) and two patients (8.3%) in zone 7 (posteromedial). The affected surface was never larger than 1.2 mm.

Table 2 contains the data referring to the results through an evaluation of the AOFAS score, obtained in the pre- and postoperative period of the osteochondral lesion of the talus. All 24 patients evaluated in the study presented a rise in the AOFAS score, averaging 22.4 points (± 11.4 standard deviation), changing the mean preoperative score from 73.6 (± 12.5) (minimum: 44/maximum: 87 points) to 96.1 points (± 5.96) (minimum: 81/maximum: 100). In the patients free from complications (22 patients), there was a rise in the AOFAS score of 23.9 (± 10.6) points. Two patients exhibited superficial infection in one of the surgical portals. The diagnosis was made two weeks after surgery and resolved with the used of oral antibiotics for seven days. No patient required an additional surgical procedure.

Table 2.

Table for evaluation of patients by the AOFAS system.

| Patient no. | Preoperative score | Postoperative score | Rise in score |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 87 | 90 | 3 |

| 2 | 84 | 100 | 16 |

| 3 | 86 | 100 | 14 |

| 4 | 52 | 90 | 38 |

| 5 | 61 | 87 | 26 |

| 6 | 85 | 100 | 15 |

| 7 | 86 | 100 | 14 |

| 8 | 69 | 100 | 31 |

| 9 | 73 | 87 | 14 |

| 10 | 81 | 90 | 9 |

| 11 | 44 | 100 | 56 |

| 12 | 73 | 100 | 27 |

| 13 | 81 | 100 | 19 |

| 14 | 85 | 100 | 15 |

| 15 | 70 | 100 | 30 |

| 16 | 65 | 97 | 32 |

| 17 | 48 | 81 | 33 |

| 18 | 84 | 100 | 16 |

| 19 | 82 | 100 | 18 |

| 20 | 74 | 100 | 26 |

| 21 | 84 | 100 | 16 |

| 22 | 65 | 97 | 32 |

| 23 | 75 | 100 | 25 |

| 24 | 74 | 87 | 13 |

| Mean | 73.6 | 96.1 | 22.4 |

| Standard deviation | 12.5 | 5.96 | 11.4 |

DISCUSSION

Osteochondral lesions of the talus are hard to diagnose and treat(6). The symptoms are usually nonspecific with late radiological findings. The use of computed tomography (CT) and of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) for the investigation of cases of pain in the ankle without a defined cause is essential for the diagnosis and early treatment of lesions. In the usual radiological views it is often difficult to locate a lateral or medial lesion, and to determine whether it is anterior, medial or posterior. NMR allows multiplanar evaluation and offers the advantage of visualizing the articular cartilage and the subchondral bone of the talus, besides evaluating the edema and the surrounding soft tissues(8).

The analysis of age bracket, distribution between left and right sides, sex and the greater incidence in the medial talar dome in our sample coincide with the observations of other authors14, 17, 26, 27. A clinical history involving ankle inversion followed by persistent chronic pain in the tibiotalar joint is the classical presentation of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Ferkel et al(8) found a previous history of trauma involving the ankle joint in 37 of the 50 patients reported in their study. Anderson et al(26) reported osteochondral fractures of the talus in 57% of the patients with ankle sprain. In our study, all the patients referred to a history of trauma in the origin of the osteochondral fracture of the talus.

Intra-articular lesions of the talus of any origin present a reserved prognosis14, 17. Invariably they cause pain, functional limitation and deterioration in the quality of life of patients. The option for arthroscopic treatment for osteochondral lesions of the talus is due to the relative ease and low morbidity of this procedure. Although having imaging resources, at present there are not criteria able to predict the development of each case. It is known that there is progression of fractures from the less severe to the most severe stages28, 29 and strong correlation between the size of the lesion and its prognosis30, 31. In this survey there was homogeneity in relation to the size of the lesions, which ranged between 0.8 and 1.2 mm. Most patients presented an improvement of symptoms, seen on the AOFAS scale.

Parisien(32) obtained 88% of good results after arthroscopic treatment in 18 patients with osteochondral lesions of the talus. The treatment consisted of partial synovectomy, debridement of the osteochondral lesion and microperforations. Even after the short follow-up period, which varied from three months to three years, Parisien recommends arthroscopic excision due to the reduced morbidity, short hospitalization period and faster recovery. In another study, Ogilvie-Harris and Sarrosa(27) described significant improvement of pain, edema and claudication after arthroscopic treatment in 33 patients, consisting of the removal of the cartilaginous fragments, debridement and abrasion of the base until bleeding occurs in the subchondral bone. Nevertheless, the study reports persistence of pain in 24% of the patients due to loose chondral and osteochondral residual dendrites at the lesion site(27).

Various studies demonstrate good and excellent results after arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. However, it was observed that most studies present a short postoperative follow-up period10, 29, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37. The importance of the follow-up period after the arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus is emphasized in the study by Hunt and Sherman(35), in which 54% of the patients presented unsatisfactory results after 66 months of follow-up.

The increase of the mean AOFAS score obtained in this study is equivalent to most of the results encountered in literature. The choice of the AOFAS table for evaluation allows us to evaluate the evolution of pain and of functions (distance walked, gait abnormalities, limitation of activities and need for support etc.)(25).

As regards the postoperative period, there is no consensus concerning the turnaround time required for the complete reestablishment of the osteochondral lesion. The information obtained through the simple radiological study during the clinical reviews is questionable, since full repair of the bone defect is very slow and often fails to occur17, 32. Hyer et al(38) mention that rehabilitation should be individualized by patient according to the physiotherapist, and can start after healing, which occurs between six and seven weeks for microperforation or internal fixation procedures, and the patient should remain without support in this period. The physiotherapy includes active and passive exercises for gain of mobility, control of edema, stretching and proprioceptive training.

CONCLUSION

The videoarthroscopy-assisted microperforation technique consists of a good option for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus and provides good functional results with an increase in the mean AOFAS score.

Footnotes

Study conducted at the Instituto de Ortopedia e Traumatologia de Passo Fundo, RS.

The authors declare that there was no conflict of interest in conducting this work

This article is available online in Portuguese and English at the websites:www.rbo.org.brandwww.scielo.br/rbort

REFERENCES

- 1.Munro A. Microgeologie. The Billroth; Berlin, Germany: 1856. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barth A. Die Enstenhung und das Wachsthum der freien Gelenkkorper. Arch Klin Chir. 1898;56:507–573. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kappis M. WeitereBeitrage zu tramatish-mechanischen Enstenhung der “spontanen” Knorpelalblosungen (sogen. Osteochondritis dissecans) Dtsch Z Chir. 1922;171:13–29. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berndt AL, Harty M. Transchondral fractures of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1959;41:988–1020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ferkel RD, Sgaglione NA, Del Pizzo W. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus: techinque and results. Orthop Trans. 1990;14:172–173. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Roach R, Frost A. Osteochondral injuries of the foot and ankle. Sports Med Arthrosc. 2009;17(2):87–93. doi: 10.1097/JSA.0b013e3181a3d7a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Elias I, Zoga AC, Morrison WB, Besser MP, Schweitzer ME, Raikin SM. Osteochondral lesions of the talus: localization and morphologic data from 424 patients using a novel anatomical grid scheme. Foot Ankle Int. 2007;28(2):154–161. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2007.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferkel DR, Zanotti MR, Komenda AG. Arthoscopic Treatment of chronic osteochondral lesions of the talus: long-term results. Am J Sports Med. 2008;36(9):1750–1762. doi: 10.1177/0363546508316773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Loomer R, Fischer C, Loyd-Smith R, Sisler J, Cooney T. Osteochondral Lesions of the talus. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21(1):13–19. doi: 10.1177/036354659302100103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pritsch M, Horoshovski H, Farine I. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68(6):862–865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Van Bergen CJA, De Leeuw PAJ, Van Dijk CN. Treatment of osteochondral defects of the talus. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 2008;94(8 Suppl):398–408. doi: 10.1016/j.rco.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amendola A, Panarella L. Osteochondral lesions: medial versus lateral, persistent pain, cartilage restoration options and indications. Foot & Ankle Clin North Am. 2009;14(2):215–227. doi: 10.1016/j.fcl.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giza E, Sullivan M, Ocel D, Lundeen G, Mitchell ME, Veris L, Walton J. Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation of talus articular defects. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31(9):747–753. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferkel RD. Artroscopy of the ankle and foot. In: Mann RA, Coughlim MJ, editors. Sugery of the foot and ankle. 8th ed. Mosby/Elsevier; Philadelphia: 2007. pp. 1643–1683. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nery CAS, Carneiro MF. Tratamento artroscópico das fraturas osteocondrais do talo. Rev Bras Ortop. 1995;30(8):567–574. [Google Scholar]

- 16.White KS, Sands AK. Osteochondral lesions of the talus. Cur Orthop Pract. 2009;20(2):123–129. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mukherjee SK, Young AB. Dome fractures of the talus a report of ten cases. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1973;55(2):319–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Van Bergen CJA, Leeuw PAJ, Van Dijk CN. Potential pitfall in the microfracturing technique during the arthroscopic treatment of an osteochondral lesion. Knee Surg. Sports Traumat Arthrosc. 2009;17(2):184–187. doi: 10.1007/s00167-008-0594-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takao M, Innami K, Komatsu F, Matsushita T. Retrograde cancellous bone plug transplantation for the treatment of advanced osteochondral lesions with large subchondral lesions of the ankle. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(8):1653–1660. doi: 10.1177/0363546510364839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nery C, Lambello C, Réssio C, Asaumi I. Implante autólogo de condrócitos no tratamento das lesões osteocondrais do talo. Rev ABTPe. 2010;4(2):113–123. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cohen M, Nery C, Pecin MS, Réssio CR, Asaumi ID, Lombello CB. Implante autólogo de condrócitos para o tratamento de lesão do côndilo femoral e talo. Einstein. 2008;6(1):37–41. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kiliç A, Kabukçuoglu Y, Gül M, Ozkaya U, Sökücü S. Early results of open mosaicoplasty in osteochondral lesions of the talus. Acta Orthop. Traumatol. Turc. 2009;43(3):235–242. doi: 10.3944/AOTT.2009.235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hahn DB, Aanstoos ME, Wilkins RM. Osteochondral lesions of the talus treated with fresh talar allografts. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31(4):277–282. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gras F, Marintschev I, Müller M, Klos K, Lindner R, Mückley T, Hofmann GO. Arthroscopic-controlled navigation for the retrograde drilling of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Int. 2010;31(10):897–904. doi: 10.3113/FAI.2010.0897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kitaoka HB, Alexander IJ, Adelar RS. AOFAS Clinical Rating Systems for the ankle-hindfoot, hallux and lesser toes. Foot Ankle Int. 1994;15(7):135–149. doi: 10.1177/107110079401500701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anderson LF, Crichton MB, Grattan-Smith MB, Cooper RA, Brazie D. Osteochondral Fractures of the dome of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71(8):1143–1152. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ogilvie-Harris DJ, Sarrosa EA. Arthroscopic Treatment of Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. Arthroscopy. 1999;15(8):805–808. doi: 10.1053/ar.1999.v15.0150801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.O'Farrell TA, Costello BG. Osteochondritis dissecans of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1982;64(4):494–497. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.64B4.7096430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robinson DE, Wilson IG, Harris WJ, Kelly AJ. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(7):989–993. doi: 10.1302/0301-620x.85b7.13959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chuckpaiwong B, Berkson EM, Theodore GH. Microfracture for osteochondral lesions of the ankle: outcome analysis and outcome predictors of 105 cases. Arthroscopy. 2008;24(1):106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2007.07.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Choi WJ, Park KK, Kim BS, Lee JW. Osteochondral lesion of the talus. Is there a critical defect size for poor outcome? Am J Sports Med. 2009;37(10):1974–1980. doi: 10.1177/0363546509335765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Parisien JS. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Sports Med Am. 1986;14(3):211–217. doi: 10.1177/036354658601400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baker CL, Andrews JR, Ryan JB. Arthroscopic treatment of transchondral talar dome fractures. Arthroscopy. 1986;2(2):82–87. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(86)80017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Frank A, Cohen P, Beaufils P, Lamare J. Atrhroscopic treatment of osteochondral talar dome. Arthroscopy. 1989;5(1):57–61. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(89)90093-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hunt SA, Sherman O. Arthroscopic treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus with corelation of outcome scoring systems. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(4):360–367. doi: 10.1053/jars.2003.50047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kumai T, Takakura Y, Higashiyama I, Tami S. Arthroscopic drilling for the treatment of osteochondral lesions of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81(9):1229–1235. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199909000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Van Buecken K, Barrack RL, Alexander AH, Ertl JP. Arthroscopic treatment of transchondral talar dome fratctures. Am J Sports Med. 1989;17(3):350–356. doi: 10.1177/036354658901700307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hyer CF, Berlet GC, Philloin TM, Lee TH. Retrograde drilling of osteochondral lesions of the talus. Foot Ankle Spec. 2008;1(4):207–209. doi: 10.1177/1938640008321653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]