Abstract

Embryo implantation requires that the uterus differentiate into the receptive state. Failure to attain uterine receptivity will impede blastocyst attachment and result in a compromised pregnancy. The molecular mechanism by which the uterus transitions from the prereceptive to the receptive stage is complex, involving an intricate interplay of various molecules. We recently found that mice with uterine deletion of Msx genes (Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d) are infertile because of implantation failure associated with heightened apicobasal polarity of luminal epithelial cells during the receptive period. However, information on Msx’s roles in regulating epithelial polarity remains limited. To gain further insight, we analyzed cell-type–specific gene expression by RNA sequencing of separated luminal epithelial and stromal cells by laser capture microdissection from Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d and floxed mouse uteri on d 4 of pseudopregnancy. We found that claudin-1, a tight junction protein, and small proline-rich (Sprr2) protein, a major component of cornified envelopes in keratinized epidermis, were substantially up-regulated in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uterine epithelia. These factors also exhibited unique epithelial expression patterns at the implantation chamber (crypt) in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f females; the patterns were lost in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelia on d 5, suggesting important roles during implantation. The results suggest that Msx genes play important roles during uterine receptivity including modulation of epithelial junctional activity.—Sun, X., Park, C. B., Deng, W., Potter, S. S., Dey, S. K. Uterine inactivation of muscle segment homeobox (Msx) genes alters epithelial cell junction proteins during embryo implantation.

Keywords: uterus, receptivity, adhesion, claudin, Sprr2

Successful implantation depends on the uterus’ attaining a state of receptivity and the embryo at the blastocyst stage’s becoming implantation competent (1, 2). In mice, the uterus is nonresponsive to blastocyst implantation on d 1–3 of pregnancy (the prereceptive phase). However, under the direction of the ovarian steroid hormones progesterone and estrogen, the uterus enters the receptive phase on d 4 of pregnancy (window of receptivity) and engages in bidirectional molecular interactions with the blastocyst throughout the apposition, attachment, and penetration stages of implantation (3, 4). The onset of receptivity is accompanied by changes in the cellular structure of the uterine luminal epithelium, including a transition from high to low apicobasal polarity and loss of apical microvilli and surface glycocalyx (5, 6). Failure to achieve the physiologic, cellular, and microstructural properties of uterine receptivity will result in failure of or defective implantation (7). Although several signaling pathways and intracellular factors are known to be essential for implantation, the definitive molecular mechanisms by which the uterus transitions from a nonreceptive to a receptive state remain unclear (2, 7).

Msx genes encode highly conserved transcription factors in the muscle segment homeobox gene family (8). The murine Msx family comprises 3 members and, like many homeobox transcription factors, they play critical roles in organogenesis. Systemic deletion of Msx1 in mice results in craniofacial abnormalities and perinatal lethality, whereas Msx2 deficiency causes defective bone and tooth morphogenesis, ectodermal organ malformations, and seizures (9, 10). Msx3’s function is not well understood in mice and is absent in the human genome (11). Msx1 and -2 mediate critical epithelial–mesenchymal interactions in multiple tissues during development, such as tooth morphogenesis, wherein epithelial bone morphogenetic protein (Bmp)-4 induces Msx1 expression in the dental mesenchyme, which in turn guides the overlying epithelium during enamel knot formation (12). At the molecular level, Msx proteins are thought to function primarily as transcriptional repressors and negative regulators of differentiation through an interaction with TATA-binding proteins (13).

We recently showed that Msx1 and -2 play an essential role in facilitating implantation by altering the cellular architecture of the uterine luminal epithelium (6). During pregnancy, Msx1 is expressed in the luminal and glandular epithelium on d 3 and 4, but is markedly down-regulated in the evening of d 4 in mice, coinciding with the time of blastocyst attachment (6, 14). Msx2 exhibits a compensatory function in uterine Msx1 deleted mice (Msx1d/d); however, uterine deletion of Msx1 and Msx2 (Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d) result in infertility because of implantation failure. Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelia fail to transition from a highly polarized, columnar state with tight cellular adherence to a less polar, cuboidal state that is conducive to blastocyst attachment (6). This heightened polarity in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri correlates with increased Wnt5a-mediated E-cadherin/β-catenin complex formation at adherens junctions during the receptive phase (6). Although transgenic mice with constitutive up-regulation of uterine Wnt5a exhibits defective implantation crypt formation and severe subfertility, the observed phenotype does not entirely replicate the infertility observed in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d females, suggesting that Msx genes have other roles in early pregnancy events (15).

To identify cell-type–specific downstream targets of Msx during uterine receptivity, we performed RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) in epithelial and stromal cells isolated by laser capture microdissection (LCM) from Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f (control) and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d females during the receptive phase in pseudopregnant mice on d 4. Pseudopregnancy was chosen to circumvent the influence of the blastocyst, but to keep the hormonal uterine milieu similar to pregnancy. In Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri, genes encoding cellular junction proteins were highly up-regulated in the epithelium, whereas genes encoding extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins were up-regulated in the stroma. Conversely, immune-related genes were down-regulated in both Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelium and stroma. We further confirmed and characterized the spatiotemporal expression patterns of claudin-1 protein, a component of tight junctions, and Sprr2, a gene associated with the cornification of keratinized epidermal cells, in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri throughout the peri-implantation period (d 1–5). In addition to aberrant expression patterns during the peri-implantation period in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri, we observed previously unidentified patterns of claudin-1 and Sprr2 in the antimesometrial epithelium around the implantation chamber at the time of implantation. Taken together, these results suggest that Msx genes have multiple roles during pregnancy that are critical for uterine receptivity and implantation success.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

All mice were housed in the Cincinnati Children’s Animal Care Facility according to institutional and U. S. National Institutes of Health Guidelines for the Use of Laboratory Animals (Bethesda, MD, USA). All protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Mice were provided with autoclaved rodent LabDiet 5010 (Nestlé Purina, St. Louis, MO, USA) and UV light–sterilized water ad libitum and were maintained under a 12-h light/dark cycle. Msx1loxP/loxP/Msx2loxP/loxP;Pgr+/+ (Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f) and Msx1loxP/loxP/Msx2loxP/loxP;PgrCre/+ (Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d) mice on a C57Bl/6 background were generated as previously described with the floxed Msx1/Msx2 (Msx1loxP/loxP/Msx2loxP/loxP) and progesterone receptor-Cre (PgrCre/+) mouse strains (6, 16). Wnt5aGOF and Wnt5ad/d (15), Stat3d/d (17), and Klf5d/d (18) transgenic mouse strains were generated as has been reported. Adult females were mated with fertile males to induce pregnancy or with vasectomized males to induce pseudopregnancy, and the morning of vaginal plug visualization was designated as d 1. For experiments using pregnant uteri, oviducts on d 1–3 or contralateral uterine horns (d 4) were flushed to verify pregnancy by the presence of fertilized embryos.

LCM

Pseudopregnant Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d mice were culled on d 4 (1030 h) and uterine pieces from 3–4 mice in each genotype were flash frozen and stored in cryovials at −80°C. Uterine cryosections were cut at 12 µm onto Arcturus PEN Membrane slides (Thermo Scientific–Applied Biosystems, Grand Island, NY, USA) and dehydrated with an ethanol gradient (70, 85, 95, and 2 × 100%; 30 s) and xylenes (5 min) and incubated in a desiccation jar for 30 min. The luminal epithelial and stroma cells were separately cut with the Veritas 704 Microdissection system and captured onto Arcturus CapSure HS LCM caps. RNA from pooled tissues was isolated with the Arcturus PicoPure kit, according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Thermo Scientific–Applied Biosystems). RNA quality and quantity were measured with the 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) before sequencing.

RNA-sequencing and analyses

RNA sequencing was performed at the Cornell University Institute of Biotechnology Genomics Facility (Ithaca, NY, USA). Template cDNA library was generated using the TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Sample Prep kit with Ribo-Zero Deplete treatment (Illumina, San Diego, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Sequencing was performed with the Illumina HiSeq1500 system in the high-output mode, with single-end 50 bp reads averaging 50 million reads per sample. Cufflinks software (University of California, Berkeley, CA, USA) was used to measure transcript abundance in reads per kilobyte of exon per million mapped reads (RPKM) as has been detailed (19). Genomic alignment of reads for genes of interest were visualized with the Integrative Genomics Viewer (Broad Institute, Cambridge, MA, USA), and gene ontology analyses were conducted with 2-fold up-regulated and down-regulated genes (FC > 2 and RPKM > 10 cutoff) using the ToppFun analysis to detect functional enrichment (ToppGene Suite, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, https://toppgene.cchmc.org).

RT-PCR

Uteri were isolated from d 4 (1030 h) pseudopregnant Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f (n = 3) and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d (n = 4) mice. RNA was prepared from homogenized uterine tissue using TRIzol reagent and cDNA was generated with the SuperScript II reverse transcriptase kit (Thermo Scientific-Invitrogen, Carlsbad CA, USA). PCR amplification was performed with the following primers: Col1a1 (5′-ACATGTTCAGCTTTGTGGACC-3′, 5′-TAGGCCATTGTGTATGCAGC-3′); Col6a4 (5′-TGACTGATGTTGCGAAGGAC-3′, 5′-TGGCACTGCTAAAGTCCTCA-3′); A2m (5′-TCTAAATGACGAGGCTGTGC-3′, 5′-TCACAGGCAGAACGTGAGTC-3′); claudin-1 (Cldn1) (5′-AGCACCGGGCAGATACAGT-3′, 5′-ATGCCAATTACCATCAAGGC-3′); Sprr2f (5′-CTCCTGGTACACACGTCCTG-3′, 5′-GTTGCTTGCACTGCTGTTCT-3′); Sprr2g (5′-CCTACACTACGTTGGAGAAGCTG-3′, 5′-CACTTTGGTGGTGGGCATAC-3′); Sprr2k (5′-TCAAGCCTTGGACTACAGAGAA-3′, 5′-CACAGGAAGAGGCTGACACA-3′); and Gapdh (5′- TCCATGACAACTTTGGCATTG-3′, 5′-CAGTCTTCTGGGTGGCAGTGA-3′).

Quantitative PCR

Quantitative (q)PCR was performed using the StepOnePlus Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Scientific-Applied Biosciences) and Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) according to manufacturer’s instructions using the cDNA template and primers shown above. All quantifications were normalized to Gapdh as an internal control. Statistical analyses were performed using the 2-tailed Student’s t test and GraphPad software, with P < 0.05 considered statistically significant.

Immunofluorescence

Uterine tissues were isolated from pseudopregnant (d 4; 1030 h) and pregnant (d 1–5; 1030 h) Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d females, flash frozen, and stored in cryovials at −80°C. Cryosections were cut at 12 µm onto poly-l-lysine-coated slides, rehydrated with PBS, and fixed with ice-cold acetone for 10 min. Sections were blocked with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA)/10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) solution and incubated with rabbit anti-claudin-1 (Thermo Scientific-Life Technologies) and mouse anti-ZO-1 (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX, USA) primary antibodies overnight at 4°C in a humidified chamber. Sections were washed and incubated with mouse Cy2-conjugated and rabbit Cy3-conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Grove, PA, USA) in addition to Hoechst 33342 nucleic acid stain. Tissue from control and experimental uteri were processed on the same slide.

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization was performed as published (20). In brief, uterine cryosections were rehydrated in PBS and postfixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA)/PBS at 4°C. Sections were acetylated and hybridized with digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probes overnight at 65°C. DIG-labeled probes for Sprr2f, Sprr2g, and pan-Sprr2 were generated according to the manufacturer's protocol (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN, USA) using TOPO vectors (Thermo Fisher Scientific) cloned with inserts isolated from Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d d 4 uterine cDNA (Sprr2f, 5′-AAGTAATGAATTTGCCCGAGA-3′, 5′-CCTGCTCAAGTGACAGAGAGA-3′; Sprr2g, 5′-GGGAAGGCATTTTTCTGAGAC-3′, 5′-GGAACATCCGTGACACACAG-3′; and pan-Sprr2, 5′-TCATTCCAGCAGAAATGC-3′, 5′-CCTGCTCAAGTGACAGAGAGA-3′). Slides were treated with RNase A, blocked in saturated casein solution, and incubated overnight at 4°C with anti-DIG antibody diluted in blocking solution (Roche Diagnostics). Sections were washed in appropriate buffers, developed with a nitro blue tetrazolium/5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (NBT/BCIP kit; Promega, Madison, WI, USA), and counterstained with eosin.

RESULTS

Gene expression is dysregulated in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri during the receptive phase

To elucidate the role of Msx during receptivity and to assess cell-type–specific alterations of transcription, we used LCM to isolate luminal epithelial and stroma cells from Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d and Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f females on d 4 of pseudopregnancy (Supplemental Fig. S1A). Pseudopregnant uteri exhibit similar receptivity as in normal pregnancy on d 4 while avoiding any potential influence from preimplantation blastocysts. After RNA-seq (detailed in Materials and Methods), we confirmed efficient isolation of targeted cells by assessing known epithelial and stromal cell markers (Supplemental Fig. S1B) and further verified deletion of the floxed region (exon 2) of Msx1 and Msx2 genes in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d samples (Supplemental Fig. S1C).We observed that deletion of Msx1 exon 2 resulted in an 8.8-fold increase in transcript abundance from exon 1 in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelium. Furthermore, the a 650 kb genomic 3′ region of the Msx1 promoter showed highly elevated transcription, and transcripts from exon 1 were spliced to novel cryptic downstream exons (Supplemental Fig. S1D). A similar pattern of elevated expression in exon 1 and downstream of the promoter was observed in the Msx2 gene in the Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelium. These findings could be the result of a feedback inhibition of Msx1 and Msx2 expression that is disrupted with Msx1/Msx2 deficiency.

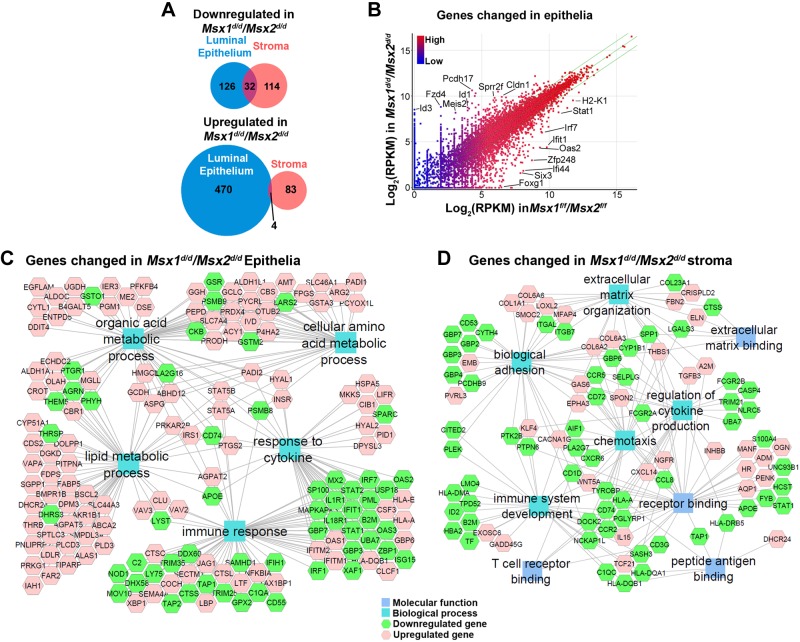

RNA-seq revealed that in the Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium, 474 genes were up-regulated and 282 genes were down-regulated by >2-fold, whereas 87 genes were up-regulated and 146 were down-regulated in TMsx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma (Fig. 1A). The more pronounced influence of Msx1 and Msx2 deletion on epithelial gene transcription is not unexpected as their expression is restricted to the luminal and glandular epithelium and maximum expression is observed on d 4 (6). In addition, the higher number of up-regulated compared to down-regulated genes in the Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium (474 vs. 282) could be attributable to Msx’s primary function as a transcriptional repressor (13). Among the differentially expressed genes, 4 up-regulated and 36 down-regulated genes were common in the epithelium and stroma (Fig. 1A). Scatter plots illustrating the fold change (by position) and absolute level of transcripts detected (by color) demonstrated the greater influence of Msx1 and Msx2 deletion on luminal epithelial expression (Fig. 1B). Some genes with most changes between floxed and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelia including Cldn1, Sprr2f, and Stat1, were labeled. All 2-fold up-regulated and down-regulated genes in each cellular compartment of Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri and the complete RNA-seq data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO; National Center for Biotechnology Information, Bethesda, MD, USA), accession number, GSE57680.

Figure 1.

RNA-seq and GO analyses of Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium and stroma. A) Venn diagrams of genes at least 2-fold up- and down-regulated in the luminal epithelium and stroma of the pseudopregnant d 4 Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uterus. B) Scatter plots of all Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d genes mapped according to fold change (distance from the diagonal) and the absolute level of RPKMs detected (blue, low; red, high). Diagonal: no change; green lines: 2-fold change. C, D) Network diagrams of GO analysis of genes changed at ≥2-fold in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelia (C) and stroma (D).

Gene ontology analyses in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri

Gene ontology analyses were performed for each cell type. For genes that showed changes of at least 2-fold in the Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium (756 total), ontology analysis identified that these genes are mainly enriched in immune response-related functions and organic acid/lipid metabolic processes (Fig. 1C). Genes changed in the Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma were mainly enriched in biologic processes related to the composition, synthesis, and maintenance of the ECM components, as well as immune function (Fig. 1D). The complete lists of biologic process and molecular function identified by analyzing genes in either luminal epithelium or stroma have been deposited in the GEO (accession number, GSE57680). Many genes related to immune response were changed in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d tissue, and most of them were down-regulated. To rule out the possibility that the decreased expression of genes related to immune responses in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri is not because of a lower number of recruited leukocytes, we compared the populations of total leukocytes and macrophages in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri on d 4. The populations of these cells were comparable in the 2 strains (Supplemental Fig. S2A).

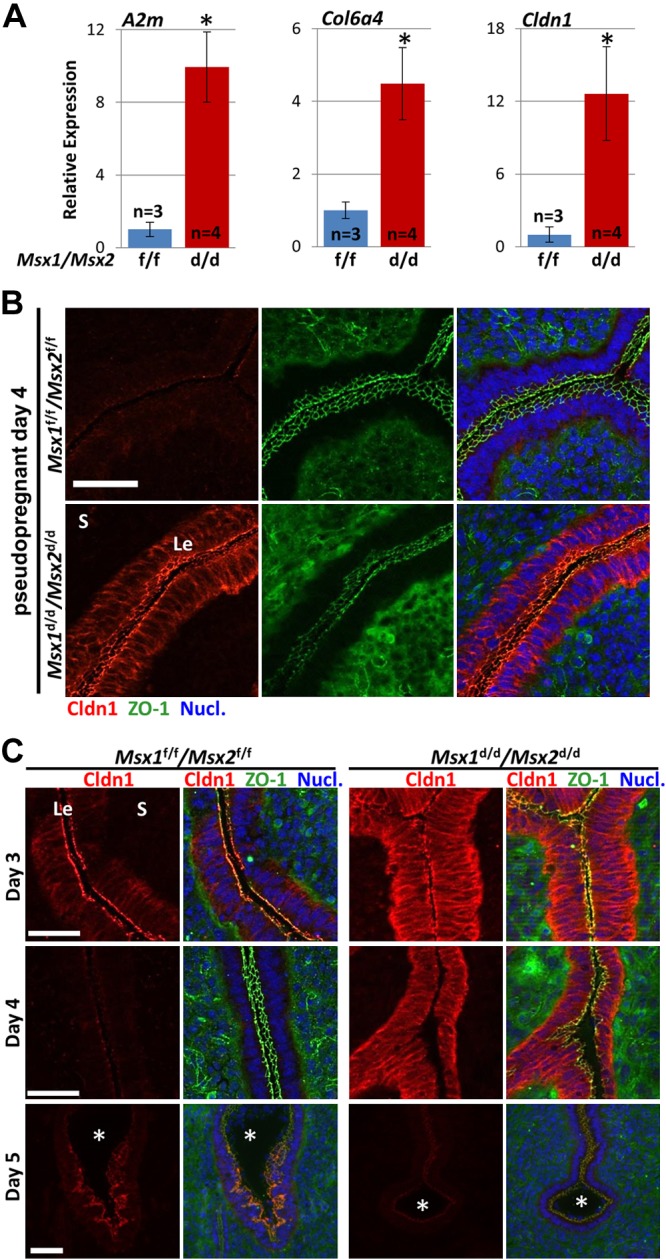

ECM genes are up-regulated in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma

The increased ECM components and enzymes in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma are noteworthy, as endometrial tissue remodeling is necessary for embryo implantation (21). The complete list of Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d up-regulated genes (19 total) that contributed to the ECM-related ontologies is presented in Table 1. This group includes 4 of the 6 type VI collagen subunits (Col6a2, -3, -4, and -6), in addition to the matricellular components fibrillin 2 (Fbn2), microfibrillar-associated protein 4 (Mfap4), osteoglycin (Ogn), spondin 2 (Spon2), and thrombospondin 1 (Thbs1). Moreover, several proteins that promote ECM retention or synthesis were up-regulated in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma. These include the protease inhibitor α-2-macroglobulin (A2m), which blocks matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-mediated matrix digestion; lysyl oxidase-like 2 (Loxl2); known to catalyze the formation of crosslinks for collagen and elastin biosynthesis, and SPARC-related modular calcium binding 2 (Smoc2), which has been observed to promote matrix assembly and is highly expressed during wound healing (Table 1) (22–24). To validate the RNA-seq data, we quantified mRNAs for A2m and Col6a4, which were up-regulated in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma by qPCR of independent d 4 samples (Fig. 2A). The result of qPCR confirmed our RNA-seq data: A2m and Col6a4 were consistently and significantly (P < 0.05) up-regulated in all Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d samples.

TABLE 1.

Expression levels of ECM genes up-regulated in d 4 Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma

|

Msx1/Msx2 stroma |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Gene name | f/f RPKM | d/d RPKM | FC (Increase) |

| A2m | α-2-mcroglobulin | 2.848 | 43.929 | 15.423 |

| Adamts7 | ADAM metallopeptidase, thrombospondin 1, 7 | 26.539 | 81.880 | 3.085 |

| Col1a1 | Collagen, type I, α 1 | 336.812 | 709.140 | 2.105 |

| Col6a2 | Collagen, type VI, α 2 | 148.398 | 321.316 | 2.165 |

| Col6a3 | Collagen, type VI, α 3 | 79.941 | 240.153 | 3.004 |

| Col6a4 | Collagen, type VI, α 4 | 120.587 | 464.690 | 3.854 |

| Col6a6 | Collagen, type VI, α 6 | 9.437 | 43.891 | 4.651 |

| Crispld2 | Cysteine-rich secretory protein LCCL domain containing 2 | 10.274 | 23.473 | 2.285 |

| Eln | Elastin | 7.697 | 15.481 | 2.011 |

| Fbn2 | Fibrillin 2 | 6.383 | 15.184 | 2.379 |

| Htra1 | HtrA serine peptidase 1 | 60.633 | 120.113 | 1.981 |

| Loxl2 | Lysyl oxidase-like 2 | 47.085 | 119.687 | 2.542 |

| Mfap4 | Microfibrillar-associated protein 4 | 20.411 | 54.503 | 2.670 |

| Ogn | Osteoglycin | 18.341 | 75.456 | 4.114 |

| Smoc2 | SPARC-related modular calcium binding 2 | 11.506 | 34.331 | 2.984 |

| Spon2 | Spondin 2, extracellular matrix protein | 16.654 | 36.795 | 2.209 |

| Tgfb3 | Transforming growth factor, β 3 | 7.145 | 14.178 | 1.984 |

| Thbs1 | Thrombospondin 1 | 35.551 | 81.533 | 2.293 |

| Wnt5a | Wingless-type MMTV integration site family, member 5A | 46.631 | 97.147 | 2.083 |

Up-regulated genes (2-fold) in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma that contributed to the ECM GO: Cellular Components (19 unique genes).

Figure 2.

Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d mice exhibit aberrant claudin-1 localization during pregnancy. A) Validation of select genes by qPCR on whole uterine mRNA extracts from pseudopregnant d 4 Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f mice (n = 3) and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d mice (n = 4). Expression values are normalized to Gapdh. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test. Data are means ± sem. B) Immunofluorescence of CLDN1 and ZO-1 demonstrated increased CLDN1 protein in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium in pseudopregnant (psp) d 4 uteri. C) Spatiotemporal analysis of CLDN1. Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri exhibit increased CLDN1 in the epithelia on d 3 to 4. CLDN1 is expressed in the antimesometrial side of the crypt epithelium in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f implantation sites on d 5, but is absent in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d implantation sites. Nucl., nuclear stain with Hoechst 33342. *Embryos. Le, luminal epithelium S, stroma. Scale bars, 50 µm.

Genes associated with uterine receptivity are dysregulated in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri

Using the genome-wide dataset, we next assessed genes that have been implicated in uterine receptivity and implantation (Supplemental Table S1). Of the 45 genes that were expressed in d 4 Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f or Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d samples, 9 exhibited >2-fold change of expression, including Indian hedgehog (Ihh), adrenomedullin (Adm), leukemia-inhibitory factor (Lif), leukemia-inhibitory factor receptor-α (Lifra), and prostaglandin-synthase 2 (Ptgs2 encoding COX2) (Table 2). The up-regulation of Ihh was recently described in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri, whereas dysregulated Lifr is consistent with an Lif-Msx1 interaction (6, 15). Lif is essential for implantation in mice and is expressed in uterine glands on d 4 and in the stroma surrounding the blastocyst on the night of d 4 and into the morning of d 5 (25, 26). We recently demonstrated that Lif down-regulates Msx1 during implantation. Although LIF administration rescues implantation failure in Lif−/− mice, it fails to do so in Lif−/−/Msx1d/d or Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d females, suggesting that LIF responsiveness in deleted uteri was disturbed (6). Ptgs2 expression is also notable because of its roles at multiple stages during pregnancy. We have observed decreased expression around the Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d implantation site on d 5 by in situ hybridization; therefore, Ptgs2 expression appears to be dysregulated at multiple stages during the peri-implantation period in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri (6).

TABLE 2.

Expression levels of genes associated with uterine receptivity

| Luminal epithelium |

Stroma |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Gene name | f/f RPKM | d/d RPKM | FC | f/f RPKM | d/d RPKM | FC |

| Adm | Adrenomedullin | 0.77 | 0.21 | 0.27 | 5.15 | 10.57 | 2.05 |

| Areg | Amphiregulin | 44.49 | 54.27 | 1.22 | 0.00 | 0.00 | N/A |

| Bmp2 | Bone morphogenetic protein 2 | 0.00 | 0.08 | N/A | 1.76 | 2.41 | 1.37 |

| Fkbp4 | FK506 binding protein 4 (a.k.a. FKBP52) | 187.01 | 294.25 | 1.57 | 77.40 | 122.10 | 1.58 |

| Hbegf | Heparin-binding EGF-like growth factor | 1.35 | 6.19 | 4.60 | 1.11 | 0.70 | 0.63 |

| Hoxa10 | Homeobox A10 | 3.04 | 2.36 | 0.78 | 148.38 | 168.41 | 1.13 |

| Hoxa11 | Homeobox A11 | 2.13 | 2.12 | 1.00 | 122.70 | 113.13 | 0.92 |

| Ihh | Indian hedgehog | 18.38 | 45.61 | 2.48 | 0.00 | 0.30 | N/A |

| Klf5 | Kruppel-like factor 5 | 20.96 | 23.05 | 1.10 | 0.46 | 0.72 | 1.55 |

| Lif | Leukemia inhibitory factor | 0.79 | 5.91 | 7.50 | 0.00 | 0.77 | N/A |

| Lifr | Leukemia inhibitory factor receptor α | 6.54 | 32.25 | 4.93 | 7.64 | 7.32 | 0.96 |

| Lpar3 | Lysophosphatidic acid receptor 3 | 125.95 | 142.86 | 1.13 | 0.22 | 0.37 | 1.66 |

| Mki67 | Antigen identified by Ki-67 antibody | 3.90 | 4.15 | 1.06 | 92.51 | 79.91 | 0.86 |

| Nog | Noggin | 1.10 | 0.25 | 0.22 | 4.33 | 2.20 | 0.51 |

| Pla2g4a | Phospholipase A2, group IVA | 146.97 | 156.38 | 1.06 | 4.55 | 3.23 | 0.71 |

| Ptgs1 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 1 | 92.84 | 187.58 | 2.02 | 9.14 | 9.63 | 1.05 |

| Ptgs2 | Prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 | 3.10 | 33.26 | 10.72 | 0.13 | 0.04 | 0.33 |

| Sgk1 | Serum/glucocorticoid regulated kinase 1 | 52.25 | 142.06 | 2.72 | 8.20 | 8.13 | 0.99 |

| Smo | Smoothened | 3.39 | 6.33 | 1.86 | 35.48 | 52.09 | 1.47 |

| Wnt5a | Wingless-type MMTV int. site fam mem 5A | 53.38 | 94.40 | 1.77 | 46.63 | 97.15 | 2.08 |

| Wnt7a | Wingless-type MMTV int. site fam mem 7A | 20.16 | 40.91 | 2.03 | 0.00 | 0.00 | N/A |

Compilation of genes associated with uterine receptivity or embryo implantation. Expression levels with FC >2.0 are underlined. An expanded list is presented in Supplemental Table S1.

Spatiotemporal expression of claudin-1 is dysregulated in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri

Tight junctions are a type of cell–cell adhesion between adjacent epithelial cells that physically bind cells together and form a selectively permeable barrier between tissue compartments (27, 28). Claudin-1 (Cldn1) is a critical tight junction protein, as Cldn1−/− pups die shortly after birth because of defective cellular adhesion and barrier functions in epithelial sheets, leading to a rapid dehydration through the epidermis (29). Based on our prior observation of heightened apicobasal polarity of luminal epithelial cells during the receptive phase in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri, we were intrigued that Cldn1 was shown by RNA-seq to be among the top up-regulated genes in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelium (∼14-fold) (6). We confirmed up-regulation of Cldn1 in uterine RNA by qPCR (Fig. 2A). Of the additional claudin family members, transcripts for claudin-3, -4, -7, and -23 were detected in the Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f control sample on d 4 by RNA-seq, with only claudin-23 exhibiting a moderate increase in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d (3-fold) (Table 3). Other components implicated in tight junction formation, such as occludin, junctional adhesion molecules (Jam), and zonula occludens (ZO/Tjp) showed various degrees of expression but with no significant differences between floxed and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d samples.

TABLE 3.

Expression of claudin and tight junction genes in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri on d 4 of pregnancy

| Luminal epithelium |

Stroma |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gene | Gene name | f/f RPKM | d/d RPKM | FC | f/f RPKM | d/d RPKM | FC |

| Cdh1 | Cadherin 1, E-cadherin | 162.85 | 173.33 | 1.06 | 2.63 | 0.52 | 0.20 |

| Cgn | Cingulin | 20.26 | 27.77 | 1.37 | 0.18 | 0.03 | 0.17 |

| Cldn1 | Claudin-1 | 7.53 | 104.89 | 13.93 | 6.41 | 6.58 | 1.03 |

| Cldn23 | Claudin-23 | 53.26 | 167.25 | 3.14 | 0.15 | 0.60 | 3.98 |

| Cldn3 | Claudin-3 | 815.57 | 669.46 | 0.82 | 6.14 | 1.16 | 0.19 |

| Cldn4 | Claudin-4 | 75.57 | 75.70 | 1.00 | 0.46 | 0.10 | 0.22 |

| Cldn7 | Claudin-7 | 142.41 | 199.02 | 1.40 | 0.76 | 0.25 | 0.33 |

| Ctnna1 | Catenin-α | 56.42 | 96.18 | 1.70 | 58.16 | 58.19 | 1.00 |

| Ctnnb1 | Catenin-β1 | 201.16 | 193.58 | 0.96 | 180.90 | 186.14 | 1.03 |

| Ctnnd1 | Catenin-δ1 | 55.38 | 73.63 | 1.33 | 51.36 | 48.36 | 0.94 |

| Jam2 | Junctional adhesion molecule-2 | 300.70 | 259.57 | 0.86 | 7.45 | 5.83 | 0.78 |

| Jam3 | Junctional adhesion molecule-3 | 0.85 | 0.36 | 0.43 | 29.21 | 32.78 | 1.12 |

| Ocln | Occludin | 42.89 | 52.42 | 1.22 | 0.63 | 0.39 | 0.63 |

| Tjp1 | Tight junction protein-1 (ZO-1) | 42.54 | 39.54 | 0.93 | 46.17 | 39.04 | 0.85 |

| Tjp2 | Tight junction protein-2 (ZO-2) | 73.08 | 100.72 | 1.38 | 29.62 | 21.37 | 0.72 |

| Tjp3 | Tight junction protein-3 (ZO-3) | 36.16 | 27.60 | 0.76 | 0.70 | 0.26 | 0.37 |

List of the select claudin family members and genes associated with tight junction complexes. Expression levels with FC >2.0 are underlined.

We next investigated the subcellular localization of claudin-1 and ZO-1 protein by immunofluorescence on d 4 of pseudopregnancy. Claudin-1 was undetectable in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f uterine sections; however, intense staining was observed along the apical, lateral, and basal surfaces of luminal epithelial cells in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri (Fig. 2B). ZO-1 was detected in endothelial cells of blood vessels in the stroma and localized on the apical surface of luminal epithelia with a similar level of intensity in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d samples.

We also examined claudin-1 localization during the peri-implantation period (d 3–5) of pregnancy in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d females. Claudin-1 was mainly observed at the apical membrane of Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f epithelia, with lower signal in basolateral regions (Fig. 2C). It was not detected in d 4 uteri or in d 5 interimplantation sites (not shown) of Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f females; however, it was observed on the apical surface of epithelial cells surrounding the antimesometrial aspect of implanting blastocysts on d 5. The signal was restricted to the epithelial cells adjacent to the embryonic mural trophectoderm, whereas epithelium adjacent to the polar trophectoderm and uterine lumen were devoid of signal. In contrast, claudin-1 showed intense staining in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri on d 3 and 4, with a distinct subcellular pattern as compared to control counterparts in which claudin-1 accumulated along all surfaces of Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelia. In addition, claudin-1 protein declined substantially by d 5 in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri. Of note, the antimesometrial signal was lost in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d implantation sites that formed a rudimentary implantation crypt before pregnancy failure. The relative level of claudin-1 localization in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri throughout pregnancy is summarized in Supplemental Fig. S2B. Changes in Cldn1 expression during uterine receptivity appears to be specific to Msx1/Msx2 transcription factors, as other mutant mouse lines that experience implantation failure had no effect on claudin-1 levels. Mice overexpressing uterine Wnt5a (Wnt5aGOF) and mice with uterine-specific deletions of Wnt5a (Wnt5ad/d), Stat3 (Stat3d/d), or Klf5 (Klf5d/d) had no detectable claudin-1 protein on d 4, similar to that observed in wild-type (WT) Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f females (Supplemental Fig. S2D).

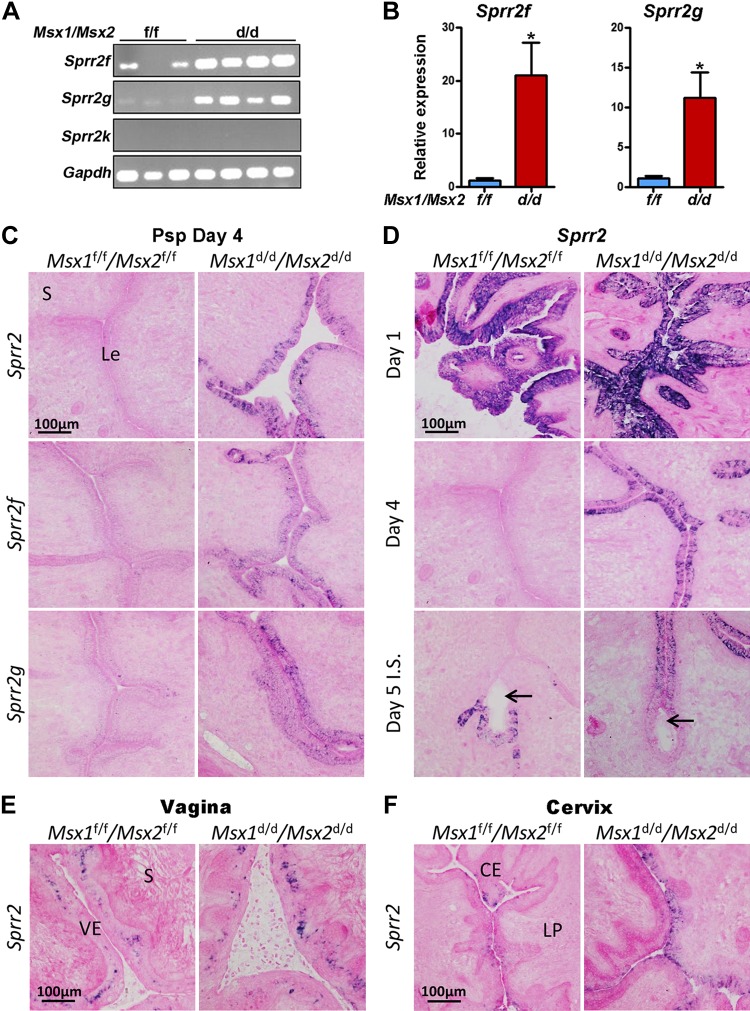

Sprr2f and Sprr2g are aberrantly expressed in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri during the peri-implantation period

Among the highly up-regulated genes in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium were 2 Sprr genes, Sprr2f (12-fold) and Sprr2g (31-fold), for which the physiologic function in the uterus remains unknown. Aside from Sprr2f and Sprr2g in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d, most of the Sprr transcripts were undetected in d 4 Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f or Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium or stroma (Supplemental Table S2). These observations were confirmed by RT-PCR and qPCR on whole uterine extracts (Fig. 3A, B). Sprr2f and Sprr2g expression was substantially up-regulated in all Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri (n = 4), as shown by qPCR, but variability among individual mice rendered the results statistically insignificant, as Sprr2f levels ranged from 15.3-fold to 102.6-fold up-regulated and Sprr2g ranged from 17.8- to 177.7-fold up-regulated. To examine the cell-specific up-regulation of epithelial Sprr2f and Sprr2g, we performed in situ hybridization with gene-specific probes and a pan-Sprr2 probe on uterine sections from Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d pseudopregnant d 4 uteri. Expression was observed in the luminal and glandular epithelium of Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uterine sections for all 3 probes, whereas Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f tissues did not show detectable signals (Fig. 3C). The aberrant expression of Sprr2f and Sprr2g is unique to Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uterine epithelia, as no distinguishable differences were observed between Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d or Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f vagina or cervix on d 4 of pseudopregnancy with the pan-Sprr2 (Fig. 3E, F) or Sprr2f and Sprr2g probes (not shown).

Figure 3.

Sprr2f and Sprr2g are overexpressed in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri during pregnancy. A) RT-PCR of Sprr2f, -2g, and -2k and Gapdh on whole uterine mRNA extracts from Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f (n = 3) and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d (n = 4) females on d 4 of pseudopregnancy. B) qPCR for Sprr2f and Sprr2g on pseudopregnant d 4 Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uterine extracts. Expression values are normalized to Gapdh. *P < 0.05, Student’s t test. Data are means ± sem. C) In situ hybridization on transverse uterine sections from pseudopregnant (psp) d 4 females for pan-Sprr2, -Sprr2f, and -Sprr2g indicate expression was significantly increased in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelium. D) In situ hybridization indicated that pan-Sprr2 expression was normally highest in d 1 luminal epithelium and in the antimesometrial epithelium of the d 5 implantation chamber. Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri exhibited increased expression throughout the peri-implantation period (d 2–4) and a loss of the antimesometrial-specific expression at the implantation site (d 5). Arrows: the location of the embryo. E) Vagina and (F) cervix with pan-Sprr2 probe. Le, luminal epithelium; S, stroma; VE, vaginal epithelium; CE, cervical epithelium; LP, lamina propria.

We next generated expression profiles in the Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri during the peri-implantation period of normal pregnancy (d 1–5), with the pan-Sprr2 probe. In floxed mice, abundant Sprr2 transcripts were detected in the luminal epithelium on d 1, but expression was undetectable in d 3 (not shown), d 4 (Fig. 3D) uteri and in d 5 interimplantation sites (data not shown). However, Sprr2 expression was observed in epithelial cells lining the antimesometrial side of the implantation chamber on d 5 in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f females. Our observation of high Sprr2 expression on d 1 with substantially reduced levels on d 2–5 are consistent with previously published data obtained by Northern blot analysis of whole uterine extracts; however, Sprr2 expression at the implantation sites had not been reported, which may be because of a difference in the timing of collection (d 4 2200 h vs. d 5, 1030 h) (30). In Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri, in situ hybridization of Sprr2 showed strong signal on d 1 that was indistinguishable from WT levels. Although Sprr2 expression was decreased on d 3 (not shown) and d 4 in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri, expression remained markedly higher than Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f uteri at corresponding time points. On d 5, Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium maintained Sprr2 expression but epithelia surrounding the implantation sites had no detectable expression and therefore lacked the antimesometrial localization observed around the implantation chambers in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f females. The relative level of Sprr2 expression in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f and Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri during pregnancy is summarized in Supplemental Fig. S2C.

DISCUSSION

The results of this study reveal new insight into the potential roles of Msx during pregnancy, by identifying the compartment-specific transcriptional network and cellular aberrations that resulted from Msx1/Msx2 deletion. These alterations include immune response genes, components of the ECM, and factors that determine epithelial adherence. Furthermore, we describe unique patterns of claudin-1, a tight junction protein, and of Sprr2, a small proline-rich protein, during implantation that became aberrant in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d females, which have implantation failure and infertility.

Functional enrichment analyses of down-regulated genes in both Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d luminal epithelium and stroma revealed that most altered genes are related to immunologic responses. Genes contributing to these ontologies vary in specific function and include major histocompatibility complexes (MHC/H2 genes), chemokines, IL receptors, IFN-induced proteins (Ifit), Stat transducers (Stat1/Stat2), and oligoadenylate synthetases (Oas), which defend against viral infection. Tight regulation of host immunity is an important aspect of pregnancy establishment and success. We had observed a similar down-regulation of immune response genes by microarray when comparing activated with delayed implanting uteri (31). Msx1 expression persists in the epithelium of delayed uteri, but becomes undetectable after initiation of implantation in floxed mice (6, 32); therefore, Msx may regulate immune response genes in both delayed and normal receptive-stage uteri before implantation. However, the underlying mechanism by which Msx genes influence immunologic responses during receptivity and implantation remains to be determined.

The up-regulation of factors involved in the synthesis and maintenance of ECM in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d stroma is noteworthy as ECM remodeling is necessary for embryo implantation (21). The RNA-seq data suggest that Msx expression on d 4 of pregnancy initiates the remodeling of ECM before implantation; however, it remains unclear how Msx factors that are expressed primarily in the epithelium alters stromal ECM. In one possibility, this process is mediated indirectly via downstream paracrine signaling between the luminal epithelium and stroma. It was recently shown that constitutive activation of uterine smoothened (Smo), a transducer of Indian Hedgehog (Ihh) signaling that is primarily expressed in the epithelium, leads to increased ECM synthesis and female infertility (33). As Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri show up-regulated Ihh in the epithelium (Table 2), it is possible that the ECM synthesis is a downstream effect of increased epithelial Ihh secretion and Smo activation in the stroma. This scenario is reminiscent of the epithelial–mesenchymal interactions characteristic of Msx genes during craniofacial development (9).

In addition to the GO analysis, an important observation of the present study was significant increases of the tight junction protein, claudin-1 in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelium. Tight junctions are composed of transmembrane proteins on adjacent cells that are physically linked, forming a continuous adherence complex that circumscribes the lateral border of the cell near the apical surface (27, 34). Tight junctions regulate selective permeability of solutes between cellular compartments and thereby maintain distinct microenvironments within a tissue (27, 28, 35). Claudin-1 is a defining tight junction component, as transfection of L-fibroblasts with claudin-1 alone promotes cell aggregation with a high concentration of claudin localization along cell–cell contact surfaces; however, transfection of other tight junction genes, such as occludin, does not result in cellular aggregation (27, 36). In WT Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f uteri, the level of claudin-1 appears highest on d 3, which may indicate a role in regulating luminal fluid composition as the uterus prepares for blastocyst arrival. It is also apparent that claudin-1 localization in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelial cells on d 3 and 4 is more intense, but mislocalized compared with that of d 3 Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f control uteri, indicating that up-regulation is a result of dysregulation and is not merely a result of retained expression or a delay in disassembling epithelial adhesions. It is therefore possible that aberrant claudin-1, along contact surfaces would obstruct physiologic changes in epithelial morphology and contribute to the heightened polarity in Msx1/Msx2-deleted mice (6). In addition, increased claudin-1 may modify tight junction composition and alter the selective permeability of solutes across the epithelial plane during the receptive phase. This altered permeability would disrupt the controlled passage of water, signaling molecules, ions regulating pH, or histotrophic factors into the lumen.

The observation of claudin-1 at the basal site of the crypt epithelium surrounding the blastocyst in the WT mice on d 5 is significant compared with the lack of claudin-1 expression on d 4. Given that the blastocyst trophectoderm normally makes attachment with the epithelium at the lateral side, but not at the bottom, of the crypt (37), it is possible that claudin-1 accumulation at the base of the crypt epithelium prevents trophectoderm attachment at that site. Nonetheless, determining the physiologic role of claudin-1 within the crypt necessitates the uterine-specific deletion of claudin-1. Homozygous Cldn1−/− mice die 1 d after birth, and a floxed Cldn1 strain has not yet been developed (29).

The Sprrs were first identified in epidermal keratinocytes as precursor molecules of the insoluble cornified envelope, which acts as a barrier against pathogens while providing water retention, elasticity, and tensile strength to the skin (38, 39). The inclusion of Sprr2f and Sprr2g among the top up-regulated genes in the d 4 Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d epithelium is interesting, as their physiologic function in noncornified epithelium remains unknown. We observed that the expression of Sprr2 genes was highest on d 1 before declining during the peri-implantation period, which corroborates previous studies showing that uterine Sprr2 genes are induced by estrogen and estrogenic compounds (40, 41). Based on their timing of expression and known association with insoluble layers, epithelial Sprr2 on d 1 may function in fluid retention as the uterus exhibits substantial fluid retention on this day. Although Sprr2 levels decline after d 1 in Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f, expression remains high in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri. It is unclear how aberrant Sprr2 expression could contribute to Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d-associated infertility. Disruption of compartmentalization of luminal fluid is a distinct possibility. Determining the function of Sprr2 in uterine biology warrants further investigation.

In Msx1f/f/Msx2f/f mice, Sprr2 expression was restricted to the crypt epithelium around the implantation chamber in a pattern very similar to that observed for claudin-1. Notably, claudin-1 and Sprr2 were both compromised in d 5 Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d uteri. Although known to have separate functions at the molecular level, this pattern may underlie a common physiologic objective under the direction of Msx, which, when disrupted, contributes to implantation failure in Msx1d/d/Msx2d/d mice. These factors may work in tandem to create differential microenvironments in the antimesometrial vs. mesometrial subepithelial stroma during embryo apposition or attachment. Ultimately, determining the role and upstream regulation of claudin-1 and Sprr2 remain important next steps in fully elucidating the function of uterine Msx. Chromatin immunoprecipitation experiments with MSX1 in myoblast cells have shown MSX1 binding enrichment in the regulatory regions of claudin-1 and Sprr2 (42). Furthermore, the genomic binding sites contain MSX1/2 binding consensus sequences (i.e., CTAATTG) (43). However, the functional binding of MSX1 in uterine epithelial cells would require chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-Seq) analysis.

Although it is clear that Msx genes are indispensable for reproductive success, the cell type–specific genome-wide analysis in this study has demonstrated that Msx plays a multifactorial role during uterine receptivity. Uterine deletion of Msx genes altered maternal immunologic responses in both the epithelium and stroma, disrupted ECM composition in the stroma, and influenced the expression of several genes implicated in receptivity. Furthermore, Msx transcription factors appear to modulate epithelial tight junctions during early pregnancy which, when mutated, leads to excessive claudin-1, which potentially obstructs the restructuring of the epithelium during the receptive stage. Attaining a deeper understanding of the fundamental mechanisms that define uterine receptivity remains a necessary step toward improving assisted reproductive technologies and combating infertility in women.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank J. Lydon and F. DeMayo (Baylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA) for initially providing the PgrCre/+ mice, and R. Maxson (University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA, USA) for the Msx1loxP/loxP/Msx2loxP/loxP mice. This study was supported in part by U.S. National Institutes of Health (NIH) National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Grant HD068524, NIH National Cancer Institute Grant P01-CA77839, and March of Dimes Grants 3-FY12-127 and 3-FY13-543 (to S.K.D). C.B.P. was supported by a fellowship from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Glossary

- A2m

α-2-macroglobulin

- Adm

adrenomedullin

- Bmp

bone morphogenetic protein

- Cldn1

claudin-1

- Col6a4

collagen 6a4

- DIG

digoxigenin

- ECM

extracellular matrix

- FC

fold change

- GEO

Gene Expression Omnibus

- GO

Gene Ontology

- Ihh

Indian hedgehog

- Klf

Kruppel-like factor

- LCM

laser capture microdissection

- Lif

leukemia inhibitory factor

- Lifr

leukemia inhibitory factor receptor

- Mfap

microfibrillar-associated protein

- Msx

muscle segment homeobox

- Pgr

progesterone receptor

- Ptgs

prostaglandin-synthase

- RPKM

reads per kilobyte of exon per million mapped reads

- qPCR

quantitative PCR

- Seq

sequencing

- Smo

smoothened

- Sprr

small proline-rich proteins

- Stat

signal transducer and activator of transcription

- WT

wild-type

- ZO

zonula occludens

Footnotes

This article includes supplemental data. Please visit http://www.fasebj.org to obtain this information.

REFERENCES

- 1.Carson D. D., Bagchi I., Dey S. K., Enders A. C., Fazleabas A. T., Lessey B. A., Yoshinaga K. (2000) Embryo implantation. Dev. Biol. 223, 217–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wang H., Dey S. K. (2006) Roadmap to embryo implantation: clues from mouse models. Nat. Rev. Genet. 7, 185–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dey S. K. (2004) Focus on implantation. Reproduction 128, 655–656 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Paria, B. C., Reese, J., Das, S. K., and Dey, S. K. (2002) Deciphering the cross-talk of implantation: advances and challenges. Science 296, 2185–2188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Murphy C. R. (2004) Uterine receptivity and the plasma membrane transformation. Cell Res. 14, 259–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Daikoku T., Cha J., Sun X., Tranguch S., Xie H., Fujita T., Hirota Y., Lydon J., DeMayo F., Maxson R., Dey S. K. (2011) Conditional deletion of Msx homeobox genes in the uterus inhibits blastocyst implantation by altering uterine receptivity. Dev. Cell 21, 1014–1025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cha J., Sun X., Dey S. K. (2012) Mechanisms of implantation: strategies for successful pregnancy. Nat. Med. 18, 1754–1767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Finnerty J. R., Mazza M. E., Jezewski P. A. (2009) Domain duplication, divergence, and loss events in vertebrate Msx paralogs reveal phylogenomically informed disease markers. BMC Evol. Biol. 9, 18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Satokata I., Maas R. (1994) Msx1 deficient mice exhibit cleft palate and abnormalities of craniofacial and tooth development. Nat. Genet. 6, 348–356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satokata I., Ma L., Ohshima H., Bei M., Woo I., Nishizawa K., Maeda T., Takano Y., Uchiyama M., Heaney S., Peters H., Tang Z., Maxson R., Maas R. (2000) Msx2 deficiency in mice causes pleiotropic defects in bone growth and ectodermal organ formation. Nat. Genet. 24, 391–395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhong Y. F., Holland P. W. (2011) The dynamics of vertebrate homeobox gene evolution: gain and loss of genes in mouse and human lineages. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 169 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alappat S., Zhang Z. Y., Chen Y. P. (2003) Msx homeobox gene family and craniofacial development. Cell Res. 13, 429–442 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang H., Catron K. M., Abate-Shen C. (1996) A role for the Msx-1 homeodomain in transcriptional regulation: residues in the N-terminal arm mediate TATA binding protein interaction and transcriptional repression. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93, 1764–1769 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daikoku, T., Song, H., Guo, Y., Riesewijk, A., Mosselman, S., Das, S. K., and Dey, S. K. (2004) Uterine Msx-1 and Wnt4 signaling becomes aberrant in mice with the loss of leukemia inhibitory factor or Hoxa-10: evidence for a novel cytokine-homeobox-Wnt signaling in implantation. Mol. Endocrinol. 18, 1238–1250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cha J., Bartos A., Park C., Sun X., Li Y., Cha S. W., Ajima R., Ho H. Y., Yamaguchi T. P., Dey S. K. (2014) Appropriate crypt formation in the uterus for embryo homing and implantation requires Wnt5a-ROR signaling. Cell Reports 8, 382–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Soyal S. M., Mukherjee A., Lee K. Y., Li J., Li H., DeMayo F. J., Lydon J. P. (2005) Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis 41, 58–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun, X., Bartos, A., Whitsett, J. A., and Dey, S. K. (2013) Uterine deletion of Gp130 or Stat3 shows implantation failure with increased estrogenic responses. Mol. Endocrinol.27, 1492–1501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sun X., Zhang L., Xie H., Wan H., Magella B., Whitsett J. A., Dey S. K. (2012) Kruppel-like factor 5 (KLF5) is critical for conferring uterine receptivity to implantation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 1145–1150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Trapnell C., Roberts A., Goff L., Pertea G., Kim D., Kelley D. R., Pimentel H., Salzberg S. L., Rinn J. L., Pachter L. (2012) Differential gene and transcript expression analysis of RNA-seq experiments with TopHat and Cufflinks. Nat. Protoc. 7, 562–578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simmons D. G., Rawn S., Davies A., Hughes M., Cross J. C. (2008) Spatial and temporal expression of the 23 murine prolactin/placental lactogen-related genes is not associated with their position in the locus. BMC Genomics 9, 352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Das S. K., Yano S., Wang J., Edwards D. R., Nagase H., Dey S. K. (1997) Expression of matrix metalloproteinases and tissue inhibitors of metalloproteinases in the mouse uterus during the peri-implantation period. Dev. Genet. 21, 44–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Borth W. (1992) Alpha 2-macroglobulin, a multifunctional binding protein with targeting characteristics. FASEB J. 6, 3345–3353 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Frantz C., Stewart K. M., Weaver V. M. (2010) The extracellular matrix at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 123, 4195–4200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Maier S., Paulsson M., Hartmann U. (2008) The widely expressed extracellular matrix protein SMOC-2 promotes keratinocyte attachment and migration. Exp. Cell Res. 314, 2477–2487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Song H., Lim H., Paria B. C., Matsumoto H., Swift L. L., Morrow J., Bonventre J. V., Dey S. K. (2002) Cytosolic phospholipase A2alpha is crucial [correction of A2alpha deficiency is crucial] for ‘on-time’ embryo implantation that directs subsequent development. Development 129, 2879–2889 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stewart C. L., Kaspar P., Brunet L. J., Bhatt H., Gadi I., Köntgen F., Abbondanzo S. J. (1992) Blastocyst implantation depends on maternal expression of leukaemia inhibitory factor. Nature 359, 76–79 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tsukita S., Furuse M., Itoh M. (2001) Multifunctional strands in tight junctions. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 285–293 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Furuse M. (2010) Molecular basis of the core structure of tight junctions. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a002907 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furuse M., Hata M., Furuse K., Yoshida Y., Haratake A., Sugitani Y., Noda T., Kubo A., Tsukita S. (2002) Claudin-based tight junctions are crucial for the mammalian epidermal barrier: a lesson from claudin-1-deficient mice. J. Cell Biol. 156, 1099–1111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tan Y. F., Sun X. Y., Li F. X., Tang S., Piao Y. S., Wang Y. L. (2006) Gene expression pattern and hormonal regulation of small proline-rich protein 2 family members in the female mouse reproductive system during the estrous cycle and pregnancy. Reprod. Nutr. Dev. 46, 641–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reese J., Das S. K., Paria B. C., Lim H., Song H., Matsumoto H., Knudtson K. L., DuBois R. N., Dey S. K. (2001) Global gene expression analysis to identify molecular markers of uterine receptivity and embryo implantation. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 44137–44145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cha J., Sun X., Bartos A., Fenelon J., Lefèvre P., Daikoku T., Shaw G., Maxson R., Murphy B. D., Renfree M. B., Dey S. K. (2013) A new role for muscle segment homeobox genes in mammalian embryonic diapause. Open Biol. 3, 130035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Franco H. L., Lee K. Y., Rubel C. A., Creighton C. J., White L. D., Broaddus R. R., Lewis M. T., Lydon J. P., Jeong J. W., DeMayo F. J. (2010) Constitutive activation of smoothened leads to female infertility and altered uterine differentiation in the mouse. Biol. Reprod. 82, 991–999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Madara J. L. (1988) Tight junction dynamics: is paracellular transport regulated? Cell 53, 497–498 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gumbiner B. M. (1993) Breaking through the tight junction barrier. J. Cell Biol. 123, 1631–1633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Furuse M., Sasaki H., Fujimoto K., Tsukita S. (1998) A single gene product, claudin-1 or -2, reconstitutes tight junction strands and recruits occludin in fibroblasts. J. Cell Biol. 143, 391–401 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enders A. C. (1975) The implantation chamber, blastocyst and blastocyst imprint of the rat: a scanning electron microscope study. Anat. Rec. 182, 137–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Candi E., Schmidt R., Melino G. (2005) The cornified envelope: a model of cell death in the skin. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 328–340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kartasova T., van de Putte P. (1988) Isolation, characterization, and UV-stimulated expression of two families of genes encoding polypeptides of related structure in human epidermal keratinocytes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 8, 2195–2203 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong S. H., Nah H. Y., Lee J. Y., Lee Y. J., Lee J. W., Gye M. C., Kim C. H., Kang B. M., Kim M. K. (2004) Estrogen regulates the expression of the small proline-rich 2 gene family in the mouse uterus. Mol. Cells 17, 477–484 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hong S. H., Lee J. E., Jeong J. J., Hwang S. J., Bae S. N., Choi J. Y., Song H. (2010) Small proline-rich protein 2 family is a cluster of genes induced by estrogenic compounds through nuclear estrogen receptors in the mouse uterus. Reprod. Toxicol. 30, 469–476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang J., Kumar R. M., Biggs V. J., Lee H., Chen Y., Kagey M. H., Young R. A., Abate-Shen C. (2011) The Msx1 homeoprotein recruits polycomb to the nuclear periphery during development. Dev. Cell 21, 575–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Catron K. M., Wang H., Hu G., Shen M. M., Abate-Shen C. (1996) Comparison of MSX-1 and MSX-2 suggests a molecular basis for functional redundancy. Mech. Dev. 55, 185–199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.