Abstract

Background:

It is often challenging to distinguish tuberculous pleural effusion (TPE) from malignant pleural effusion (MPE); thoracoscopy is among the techniques with the highest diagnostic ability in this regard. However, such invasive examinations cannot be performed on the elderly, or on those in poor physical condition. The aim of this study was to explore the differential diagnostic value of carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), carbohydrate antigen 199 (CA199), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) associated antigen in patients with TPE and MPE.

Methods:

Using electrochemiluminescence, we measured the concentration of tumor markers (TMs) in the pleural effusion and serum of patients with TPE (n = 35) and MPE (n = 95). We used receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis to evaluate the TMs and differentiate between TPE and MPE.

Results:

The cut-off values for each TM in serum were: CA125, 151.55 U/ml; CA199, 9.88 U/ml; CEA, 3.50 ng/ml; NSE, 13.27 ng/ml; and SCC, 0.85 ng/ml. Those in pleural fluid were: CA125, 644.30 U/ml; CA199, 12.08 U/ml; CEA, 3.35 ng/ml; NSE, 9.71 ng/ml; and SCC, 1.35 ng/ml. The cut-off values for the ratio of pleural fluid concentration to serum concentration (P/S ratio) of each TM were: CA125, 5.93; CA199, 0.80; CEA, 1.47; NSE, 0.76; and SCC, 0.90. The P/S ratio showed the highest specificity in the case of CEA (97.14%). ROC curve analysis revealed that, for all TMs, the area under the curve in pleural fluid (0.95) was significantly different from that in serum (0.85; P < 0.001).

Conclusions:

TMs in TPE differ significantly from those in MPE, especially when detected in pleural fluid. The combined detection of TMs can improve diagnostic sensitivity.

Keywords: Malignant Pleural Effusion, Tuberculous Pleural Effusion, Tumor Marker

INTRODUCTION

It is often challenging to differentiate tuberculous pleural effusion (TPE) from malignant pleural effusion (MPE). In this regard, cytological examination of pleural effusion (PE) is a simple and common method. The technique has 100% specificity, but its sensitivity is between 43% and 83%; this is far from satisfactory.[1,2,3] In cases of negative cytological PE, diagnosis is based on invasive procedures such as thoracoscopy. Although this method has 90% sensitivity,[4] it may be too invasive for patients in poor physical condition.

By way of a solution to these problems, measuring the concentration of various tumor markers (TMs) in PE is a useful and noninvasive procedure for distinguishing between benign PE and MPE.[5,6,7] The TMs concerned are carbohydrate antigen 125 (CA125), carbohydrate antigen 153, carbohydrate antigen 199 (CA199), carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), cytokeratin 19 fragment, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), and squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) associated antigen. However, their cut-off values and sensitivities in identifying MPE are not well understood.

This retrospective study aimed to assess the diagnostic capability of each of the following TMs: CA125, CA199, CEA, NSE, and SCC. Their levels were measured in both serum and the pleural fluid to differentiate between TPE and MPE. Furthermore, the ratio of pleural fluid concentration to serum concentration (P/S ratio) for each TM was also assessed.

METHODS

Patients and classification of pleural effusion

We enrolled 130 consecutive patients who had been treated at the Department of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine of the Beijing Chao-Yang Hospital between January 2013 and December 2013.

A diagnosis of MPE (n = 95) or TPE (n = 35) was made based on thoracoscopy. The origin and histological types of MPE were lung adenocarcinoma (n = 62), lung SCC (n = 5), small cell lung carcinoma (n = 9), pleural mesothelioma (n = 12), breast cancer (n = 3), ovarian cancer (n = 1), hepatic cancer (n = 1), lymphoma (n = 1), and leukemia (n = 1).

Clinical radiological characteristics

The following clinical and radiological characteristics were considered [Tables 1 and 2]: (1) PE size (three categories: <1/3 of the hemithorax; ≥1/3, but ≤2/3 of the hemithorax; >2/3 of the hemithorax),[6] and (2) simple X-ray or computed tomography images suggestive of malignancy (lung masses, pulmonary atelectasis, lung nodules, infiltrated shadow, cavity, pleural nodules, and pleural thickening).

Table 1.

Carbohydrate antigen 125, carbohydrate antigen 199, carcinoembryonic antigen, neuron-specific enolase and squamous cell carcinoma in patients with tuberculous pleural effusion and malignant pleural effusion

| Histological types | Tuberculosis | Adenocarcinoma | SCC | Small cell carcinoma | Mesothelioma |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | |||||

| CA125 (U/ml) | 74.42 (28.91–120.95) | 92.47 (35.27–197.03) | 171.40 (114.40–277.40) | 106.10 (55.64–152.90) | 47.30 (19.72–81.27) |

| A199 (U/ml) | 6.03 (3.04–10.79) | 15.99 (10.16–51.59) | 38.19 (28.87–39.34) | 17.49 (14.28–29.17) | 6.27 (5.68–15.60) |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 1.60 (1.10–2.15) | 6.35 (3.40–23.43) | 5.10 (4.30–26.90) | 2.60 (1.40–8.10) | 1.85 (1.50–2.50) |

| NSE (ng/ml) | 13.23 (11.99–17.27) | 14.34 (11.79–17.91) | 19.62 (16.53–21.12) | 52.25 (23.77–112.40) | 14.48 (13.18–15.89) |

| SCC (ng/ml) | 0.60 (0.40–0.80) | 0.60 (0.50–0.90) | 3.70 (3.10–5.10) | 1.00 (0.70–1.70) | 0.90 (0.60–1.10) |

| Pleural fluid | |||||

| CA125 (U/ml) | 277.00 (104.73–561.15) | 1172.00 (508.43–2244.75) | 616.90 (177.30–1108.00) | 932.00 (500.60–1590.00) | 383.30 (316.62–651.05) |

| CA199 (U/ml) | 2.93 (1.62–4.85) | 36.99 (6.97–198.17) | 8.55 (4.04–17.39) | 22.70 (6.01–129.40) | 3.39 (2.66–6.11) |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 1.20 (0.70–1.50) | 82.05 (15.17–487.30) | 3.90 (3.50–7.50) | 6.10 (2.00–48.00) | 1.10 (1.00–1.75) |

| NSE (ng/ml) | 8.57 (6.80–9.61) | 9.62 (7.57–10.93) | 10.72 (8.12–10.72) | 58.67 (21.64–132.17) | 8.62 (8.09–9.82) |

| SCC (ng/ml) | 0.70 (0.35–1.00) | 0.80 (0.70–1.37) | 15.10 (11.40–67.10) | 1.60 (1.00–2.50) | 1.00 (0.40–2.10) |

| P/S ratio | |||||

| CA125 | 3.07 (1.17–6.22) | 10.70 (4.78–22.50) | 2.76 (0.83–5.39) | 8.74 (3.65–16.66) | 11.90 (6.97–18.65) |

| CA199 | 0.53 (0.38–0.74) | 1.00 (0.41–3.89) | 0.46 (0.30–0.48) | 1.29 (0.44–3.20) | 0.50 (0.27–0.62) |

| CEA | 0.70 (0.55–0.91) | 7.52 (2.16–22.54) | 0.76 (0.75–0.81) | 3.36 (0.95–4.36) | 0.60 (0.44–0.74) |

| NSE | 0.56 (0.44–0.70) | 0.63 (0.49–0.80) | 0.51 (0.49–0.68) | 0.95 (0.87–1.12) | 0.60 (0.52–0.74) |

| SCC | 0.85 (0.68–1.34) | 1.36 (1.00–2.41) | 3.69 (3.08–4.70) | 1.47 (0.90–3.33) | 0.78 (0.50–2.17) |

Values are expressed as median and 25th–75th percentiles in parenthesis. CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; NSE: Neuron-specific enolase; SCC: Squamous cell carcinoma; CA125: Carbohydrate antigen 125; CA199: Carbohydrate antigen 199; P/S: Pleural fluid concentration to serum concentration.

Table 2.

Clinical and radiological characteristics of patients with pleural effusion

| Characteristics | TPE (n = 35) | MPE (n = 95) | P | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | Percentage | n | Percentage | ||

| Smoking | 15 | 42.86 | 41 | 43.16 | 0.975 |

| Dyspnea | 25 | 71.43 | 80 | 84.21 | 0.101 |

| Chest pain | 14 | 40.00 | 27 | 28.42 | 0.208 |

| Cough | 25 | 71.43 | 67 | 70.53 | 0.920 |

| Phlegm | 14 | 40.00 | 36 | 37.89 | 0.827 |

| Hemoptysis | 0 | 0.00 | 8 | 8.42 | 0.076 |

| Fever | 16 | 45.71 | 10 | 10.53 | <0.001 |

| Weight loss | 7 | 20.00 | 25 | 26.32 | 0.458 |

| Pulmonary atelectasis | 0.413 | ||||

| Obstructive atelectasis | 5 | 14.29 | 16 | 16.84 | |

| Compression atelectasis | 17 | 48.57 | 34 | 35.79 | |

| Mass | 1 | 2.86 | 1 | 1.05 | 0.458 |

| Single nodule | 0 | 0.00 | 38 | 40.00 | <0.001 |

| Multiple nodule | 2 | 5.71 | 16 | 16.84 | 0.103 |

| Infiltrated shadow | 6 | 17.14 | 28 | 29.47 | 0.156 |

| Cavity | 23 | 65.71 | 66 | 69.47 | 0.682 |

| Pleural nodules | 0 | 0.00 | 25 | 26.32 | <0.001 |

| Pleural thickening | 0.006 | ||||

| Local | 11 | 31.43 | 59 | 62.11 | |

| Diffusion | 11 | 31.43 | 13 | 13.68 | |

| Lymphadenectasis | 0.027 | ||||

| ≤1 cm | 17 | 48.57 | 38 | 40.00 | |

| >1 cm | 4 | 11.43 | 33 | 34.74 | |

| Laterality | 0.866 | ||||

| Left | 15 | 42.86 | 37 | 38.95 | |

| Right | 14 | 40.00 | 43 | 45.26 | |

| Bilateral | 6 | 17.14 | 15 | 15.79 | |

| Quantity | 0.683 | ||||

| <1/3 | 1 | 2.86 | 1 | 1.05 | |

| 1/3–2/3 | 7 | 20.00 | 16 | 16.84 | |

| >2/3 | 27 | 77.14 | 78 | 82.11 | |

TPE: Tuberculous pleural effusion; MPE: Malignant pleural effusion.

Tumor markers assay

Pleural fluid and blood were collected before any treatment. Both serum and pleural fluid were centrifuged at 3000 r/min for 15 min. TM assays were performed using electrochemiluminescence kits (Abbott Laboratories i2000™; Abbott Park, USA for CA125, CA199, CEA, and SCC; Cobas 6000™; Roche, Mannheim, Germany for NSE).

Statistical analysis

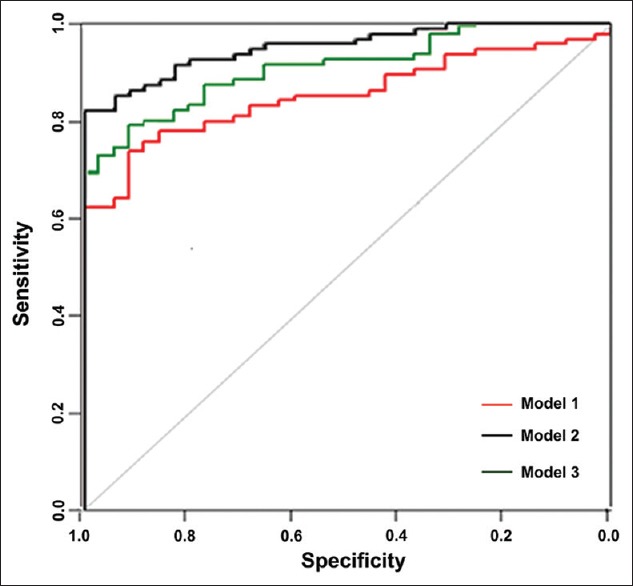

SPSS statistical software 17.0 (IBM, USA) was used for data processing. The data were mostly expressed as the median and interquartile range (IQR). Concentration differences between the TPE and MPE groups were evaluated for statistical significance using the nonparametric Mann–Whitney U-test. The optimal sensitivity and specificity points were selected as the critical values using the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve; in this way, we calculated, for each of the TMs, the sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value for diagnosing TPE and MPE. In addition, we evaluated the ability of a combination of all five TMs to distinguish between TPE and MPE. Three prognostic models were constructed: Model 1 involved the serum level of TMs, Model 2 the pleural fluid level, and Model 3 the P/S ratio. P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

General clinical data

The study included 23 men and 12 women with TPE (median age = 66 years, range = 19–93 years), and 54 men and 41 women with MPE (median age = 67 years, range = 20–99 years). The two groups did not differ significantly in terms of age or sex.

Table 2 shows the main clinical and radiological characteristics of the patients. A greater percentage of patients in the TPE group than in the MPE group experienced fever (45.71%; P < 0.001). The two groups also showed significant differences in terms of imaging parameters; namely, single nodules, pleural nodules, localized pleural thickening, and mediastinal hilum lymph node enlargement, which is defined as a node diameter >1 cm (P < 0.05 in all cases).

Detection of the five tumor markers in pleural fluid and serum

Table 1 shows the median concentrations and IQRs of the five TMs examined – in both serum and pleural fluid. All five TMs were detected in the pleural fluid and serum of all patients; however, the concentrations were significantly different between the two groups (P < 0.05).

Receiver operating characteristic analysis of the tumor markers to differentiate between tuberculous pleural effusion and malignant pleural effusion

Table 3 shows the diagnostic value of the five TMs in serum and pleural fluid, as well as the P/S ratio for discriminating between TPE and MPE. The cut-off values for each TM in serum were: CA125, 151.55 U/ml; CA199, 9.88 U/ml; CEA, 3.50 ng/ml; NSE, 13.27 ng/ml; and SCC, 0.85 ng/ml. CA125 showed the highest specificity (88.57%) for distinguishing between TPE and MPE, but it had low sensitivity (33.68%). The cut-off values for the TMs in pleural fluid were: CA125, 644.30 U/ml; CA199, 12.08 U/ml; CEA, 3.35 ng/ml; NSE, 9.71 ng/ml; and SCC, 1.35 ng/ml. Those of the P/S ratio for each TM were: CA125, 5.93; CA199, 0.80; CEA, 1.47; NSE, 0.76; and SCC, 0.90. Moreover, the P/S ratio of CEA had the highest specificity (97.14%) and sensitivity (61.05%).

Table 3.

Diagnostic value of five tumour markers in serum, pleural effusion and the ratio of pleural effusion and serum for the discrimination between tuberculous pleural effusion and malignant pleural effusion

| TM | Cut-off value | AUC | Specificity (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Accuracy (%) | PLR | NLR | LR | PPV (%) | NPV (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum | ||||||||||

| CA125 (U/ml) | 151.55 | 0.58 | 88.57 | 33.68 | 48.46 | 2.95 | 0.75 | 3.94 | 88.89 | 32.98 |

| CA199 (U/ml) | 9.88 | 0.76 | 74.29 | 67.37 | 69.23 | 2.62 | 0.44 | 5.96 | 87.67 | 45.61 |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 3.50 | 0.79 | 80.00 | 58.95 | 64.62 | 2.95 | 0.51 | 5.74 | 88.89 | 41.79 |

| NSE (ng/ml) | 13.27 | 0.58 | 54.29 | 70.53 | 66.15 | 1.54 | 0.54 | 2.84 | 80.72 | 40.43 |

| SCC (ng/ml) | 0.85 | 0.57 | 77.14 | 36.84 | 47.69 | 1.61 | 0.82 | 1.97 | 81.40 | 31.03 |

| Pleural fluid | ||||||||||

| CA125 (U/ml) | 644.3 | 0.78 | 82.86 | 61.05 | 66.92 | 3.56 | 0.47 | 7.58 | 90.62 | 43.94 |

| CA199 (U/ml) | 12.08 | 0.81 | 97.14 | 53.68 | 65.38 | 18.79 | 0.48 | 39.41 | 98.08 | 43.59 |

| CEA (ng/ml) | 3.35 | 0.86 | 94.29 | 74.74 | 80.00 | 13.08 | 0.27 | 48.81 | 97.26 | 57.89 |

| NSE (ng/ml) | 9.71 | 0.66 | 77.14 | 52.63 | 59.23 | 2.30 | 0.61 | 3.75 | 86.21 | 37.50 |

| SCC (ng/ml) | 1.35 | 0.69 | 91.43 | 36.84 | 51.54 | 4.30 | 0.69 | 6.22 | 92.11 | 34.78 |

| P/S ratio | ||||||||||

| CA125 | 5.93 | 0.75 | 74.29 | 67.37 | 69.23 | 2.62 | 0.44 | 5.96 | 87.67 | 45.61 |

| CA199 | 0.80 | 0.64 | 82.86 | 51.58 | 60.00 | 3.01 | 0.58 | 5.15 | 89.09 | 38.67 |

| CEA | 1.47 | 0.79 | 97.14 | 61.05 | 70.77 | 21.37 | 0.40 | 53.30 | 98.31 | 47.89 |

| NSE | 0.76 | 0.64 | 85.71 | 38.95 | 51.54 | 2.73 | 0.71 | 3.83 | 88.10 | 34.09 |

| SCC | 0.90 | 0.69 | 60.00 | 75.79 | 71.54 | 1.89 | 0.40 | 4.70 | 83.72 | 47.73 |

TM: Tumor marker; AUC: Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; PLR: Positive likelihood ratio; NLR: Negative likelihood ratio; PPV: Positive predictive value; NPV: Negative predictive value; LR: Likelihood ratio; CA125: Carbohydrate antigen 125; CA199: Carbohydrate antigen 199; CEA: Carcinoembryonic antigen; NSE: Neuron-specific enolase; SCC: Squamous cell carcinoma; P/S: Pleural fluid concentration to serum concentration.

We evaluated the diagnostic value of a combination of all five TMs in serum and pleural fluid; we analyzed the P/S ratio in the same regard. To this end, we established the following diagnostic models: Model 1 involved the serum level of all TMs; Model 2 the pleural fluid level; Model 3 the P/S ratio:

Model 1 = −2.597 + 0.001 (CA125) + 0.058 (CA199) + 0.353 (CEA) + 0.073 (NSE) + 0.388 (SCC); cut-off value = 0.934

Model 2 = −4.243 + 0.002 (CA125) + 0.103 (CA199) + 0.360 (CEA) + 0.122 (NSE) + 0.512 (SCC); cut-off value = 1.592

Model 3 = −4.048 + 0.135 (CA125) + 0.309 (CA199) + 1.108 (CEA) + 2.592 (NSE) + 0.367 (SCC); cut-off value = 0.984.

Table 4 shows the predicted outcome: The accuracy of Model 2 (88.15%) was higher than that of the other models (P < 0.001). The ROC curves are shown in Figure 1.

Table 4.

Diagnostic value of combination of five tumor markers in serum, pleural effusion and the ratio of pleural effusion and serum for achieving the best diagnostic accuracy

| TM | Cut-off value | AUC | Specificity (%) | Sensitivity (%) | Accuracy (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.93 | 0.85 | 91.43 | 73.68 | 78.46 |

| Model 2 | 1.59 | 0.95 | 100.00 | 82.11 | 86.92 |

| Model 3 | 0.98 | 0.91 | 91.43 | 78.95 | 82.31 |

In Model 1: We evaluated all of five TMs in serum; in Model 2: We evaluated five TMs in pleural fluid; in Model 3: We evaluated all of the TMs in the P/S ratio. TM: Tumor marker; AUC: Area under the receiver operating characteristic curve; P/S: Pleural fluid concentration to serum concentration.

Figure 1.

In Model 1, we evaluated all five tumor markers in serum. In Model 2, we evaluated the five tumor markers in pleural fluid. In Model 3, the ratio of the tumor marker concentration in pleural fluid to that in serum was analyzed.

DISCUSSION

PE can be caused by more than 50 diseases, including primary lung disease, systemic disease, organ dysfunction, drug-induced PE, and tumor metastasis. It is important in clinical practice to analyze both the cause and clinical features in patients with PE; for this purpose, cytological examination is routinely performed. However, the positive diagnostic rate of this technique is about 50% in patients with MPE.[8] Even though adenocarcinoma is the most common cause of MPE, a significant number of hematological and nonhematological causes also exist. To ensure an accurate diagnosis, cytopathologists, and clinicians must keep these uncommon phenomena in mind during routine practice.[9]

The currently available data indicate that, in cases where aspiration cytology reveals negativity for exudative PE, thoracoscopy under local anesthetic is among the techniques with the highest diagnostic ability; the method has about 88–96% diagnostic sensitivity for malignant pleural disease.[10,11,12] However, such invasive examinations cannot be performed in the elderly, or in those in poor physical condition. Uncontrollable coughing from pleural irritation also contraindicates thoracoscopy, as it is hazardous to access and visualize the whole pleura in such cases.[13]

Currently, the cause of PE is unclear in nearly 20% of patients,[14] and many researchers have shown that TMs may help differentiate TPE from MPE. Furthermore, a combination of several TMs may improve the diagnostic power for MPE.[5,8,15,16,17,18] The choice of TMs in this study was based on those used in clinical practice to detect ovarian cancer (CA125), gastrointestinal and lung cancer (CA199), digestive and lung cancer (CEA), nonsmall cell lung cancer (SCC), and small cell lung cancer (NSE). The serum and pleural fluid concentrations of CA125, CA199, CEA, and NSE were significantly higher in MPE than in TPE (P < 0.05); similar results have been reported in other studies.[2,19,20]

We reviewed studies addressing the level of TMs in serum and pleural fluid, but only a few described P/S ratio.[21,22] In this study, we found that the P/S ratios of CEA and CA125 were lower in TPE than in MPE. Korczynski et al.[23] reported a similar result regarding CEA, although the P/S ratio of CA125 was not significantly different. Li et al.[24] found that higher CA125 levels are associated with an increased risk of coronary heart disease in elderly Chinese individuals, and that CEA exhibited 70% sensitivity and 100% specificity for adenocarcinoma cells in PE.[3]

We believe that these differences may be due to the number of pooled patients, as well as to the etiology of the analyzed PE in the two studies. Using ROC analysis, we determined the cut-off values of CA125, CA199, CEA, NSE, and SCC in serum and pleural fluid. However, their specificities in diagnosing MPE varied. Model 2 had better accuracy (86.92%) in terms of MPE diagnosis. Pleural fluid cut-off values for differential diagnosis were generally higher than those of serum; however, this finding does not justify routinely measuring classic TMs in the workup of PEs.

There were several limitations to our research. For instance, only a small number of patients were enrolled, especially in the case of TPE. Furthermore, the majority of primary tumors were in the lung; much fewer occurred in other organs. In future, we will enroll a larger number of patients with PE and design a randomized controlled trial to research the differential diagnosis between TPE and MPE.

An ideal diagnostic combination of TMs would have high specificity and sensitivity. In cases where MPE is suspected, but cytological findings are negative, the level of TMs in serum and pleural fluid, as well as the P/S ratio, should be evaluated before performing invasive procedures; this would help optimize the cost-benefit ratio. First, pleural CEA measurement is likely to be useful in diagnosing MPE, just as it is in the differentiation of malignant pleural mesothelioma from metastatic lung cancer – a high level of pleural CEA seems to rule out malignant mesothelioma. Second, CA125, CA199, NSE, and SCC are highly specific, but insufficiently sensitive to diagnose MPE, although the combination of more TMs appears to increase the diagnostic sensitivity.

The present study describes a diagnostic model that involves five TMs in serum and pleural fluid. In particular, since the detection of TMs in pleural fluid has high specificity (100%) and accuracy (86.92%), it may be useful in distinguishing MPE from TPE. The results of TM assays should be interpreted in parallel with clinical findings, and with the results of conventional tests.

Financial support and sponsorship

This work was supported by grants from National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 91442109, No. 31470883, and No. 81270149).

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Edited by: Li-Min Chen

REFERENCES

- 1.Alemán C, Sanchez L, Alegre J, Ruiz E, Vázquez A, Soriano T, et al. Differentiating between malignant and idiopathic pleural effusions: The value of diagnostic procedures. QJM. 2007;100:351–9. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm032. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcm032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hackbarth JS, Murata K, Reilly WM, Algeciras-Schimnich A. Performance of CEA and CA19-9 in identifying pleural effusions caused by specific malignancies. Clin Biochem. 2010;43:1051–5. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.05.016. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2010.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yahya ZM, Ali HH, Hussein HG. Evaluation of the sensitivity and specificity of immunohistochemical markers in the differential diagnosis of effusion cytology. Oman Med J. 2013;28:410–6. doi: 10.5001/omj.2013.117. doi: 10.5001/omj.2013.117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rozman A, Camlek L, Kern I, Malovrh MM. Semirigid thoracoscopy: An effective method for diagnosing pleural malignancies. Radiol Oncol. 2014;48:67–71. doi: 10.2478/raon-2013-0068. doi: 10.2478/raon-2013-0068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang XF, Wu YH, Wang MS, Wang YS. CEA, AFP, CA125, CA153 and CA199 in malignant pleural effusions predict the cause. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2014;15:363–8. doi: 10.7314/apjcp.2014.15.1.363. doi: 10.7314/APJCP.2014.15.1.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valdés L, San-José E, Ferreiro L, González-Barcala FJ, Golpe A, Álvarez-Dobaño JM, et al. Combining clinical and analytical parameters improves prediction of malignant pleural effusion. Lung. 2013;191:633–43. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9512-2. doi: 10.1007/s00408-013-9512-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Choi WI, Qama D, Lee MY, Kwon KY. Pleural cancer antigen-125 levels in benign and malignant pleural effusions. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2013;17:693–7. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0635. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.12.0635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hsieh TC, Huang WW, Lai CL, Tsao SM, Su CC. Diagnostic value of tumor markers in lung adenocarcinoma-associated cytologically negative pleural effusions. Cancer Cytopathol. 2013;121:483–8. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21283. doi: 10.1002/cncy.21283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cakir E, Demirag F, Aydin M, Erdogan Y. A review of uncommon cytopathologic diagnoses of pleural effusions from a chest diseases center in Turkey. Cytojournal. 2011;8:13. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.83026. doi: 10.4103/1742-6413.83026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman NM, Ali NJ, Brown G, Chapman SJ, Davies RJ, Downer NJ, et al. Local anaesthetic thoracoscopy: British Thoracic Society Pleural Disease Guideline 2010. Thorax. 2010;65(Suppl 2):ii54–60. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.137018. doi: 10.1136/thx.2010.137018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nattusamy L, Madan K, Mohan A, Hadda V, Jain D, Madan NK, et al. Utility of semi-rigid thoracoscopy in undiagnosed exudative pleural effusion. Lung India. 2015;32:119–26. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.152618. doi: 10.4103/0970-2113.152618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gao BA, Zhou G, Guan L, Zhang LY, Xiang GM. Effectiveness and safety of diagnostic flexi-rigid thoracoscopy in differentiating exudative pleural effusion of unknown etiology: A retrospective study of 215 patients. J Thorac Dis. 2014;6:438–43. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.02.09. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2014.02.09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dixon G, de Fonseka D, Maskell N. Pleural controversies: Image guided biopsy vs. thoracoscopy for undiagnosed pleural effusions? J Thorac Dis. 2015;7:1041–51. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.01.36. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2015.01.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gu Y, Zhang M, Li GH, Gao JZ, Guo L, Qiao XJ, et al. Diagnostic values of vascular endothelial growth factor and epidermal growth factor receptor for benign and malignant hydrothorax. Chin Med J. 2015;128:305–9. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.150091. doi: 10.4103/0366-6999.150091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shi HZ, Liang QL, Jiang J, Qin XJ, Yang HB. Diagnostic value of carcinoembryonic antigen in malignant pleural effusion: A meta-analysis. Respirology. 2008;13:518–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1843.2008.01291.x. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-18.43.2008.01291.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu P, Huang G, Chen Y, Zhu C, Yuan J, Sheng S. Diagnostic utility of pleural fluid carcinoembryonic antigen and CYFRA 21-1 in patients with pleural effusion: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Lab Anal. 2007;21:398–405. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20208. doi: 10.1002/jcla.20208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang QL, Shi HZ, Qin XJ, Liang XD, Jiang J, Yang HB. Diagnostic accuracy of tumour markers for malignant pleural effusion: A meta-analysis. Thorax. 2008;63:35–41. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.077958. doi: 10.1136/thx.2007.077958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wu Q, Li M, Zhang S, Chen L, Gu X, Xu F. Clinical diagnostic utility of CA 15-3 for the diagnosis of malignant pleural effusion: A meta-analysis. Exp Ther Med. 2015;9:232–8. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2039. doi: 10.3892/etm.2014.2039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang WW, Tsao SM, Lai CL, Su CC, Tseng CE. Diagnostic value of Her-2/neu, Cyfra 21-1, and carcinoembryonic antigen levels in malignant pleural effusions of lung adenocarcinoma. Pathology. 2010;42:224–8. doi: 10.3109/00313021003631320. doi: 10.3109/00313021003631320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wu GP, Ba J, Zhao YJ, Wang EH. Diagnostic value of CEA, CYFRA 21-1, NSE and CA 125 assay in serum and pleural effusion of patients with lung cancer. Acta Cytol. 2007;51:679–80. doi: 10.1007/s12032-013-0543-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Moriwaki Y, Kohjiro N, Itoh M, Nakatsuji Y, Okada M, Ishihara H, et al. Discrimination of tuberculous from carcinomatous pleural effusion by biochemical markers: adenosine deaminase, lysozyme, fibronectin and carcinoembryonic antigen. Jpn J Med. 1989;28:478–84. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine1962.28.478. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine1962.28.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wagner IC, Guimarães MJ, da Silva LK, de Melo FM, Muniz MT. Evaluation of serum and pleural levels of the tumor markers CEA, CYFRA21-1 and CA 15-3 in patients with pleural effusion. J Bras Pneumol. 2007;33:185–91. doi: 10.1590/s1806-37132007000200013. doi: 10.1590/S1806-37132007000200013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Korczynski P, Krenke R, Safianowska A, Gorska K, Abou Chaz MB, Maskey-Warzechowska M, et al. Diagnostic utility of pleural fluid and serum markers in differentiation between malignant and non-malignant pleural effusions. Eur J Med Res. 2009;14(Suppl 4):128–33. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-S4-128. doi: 10.1186/2047-783X-14-S4-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li X, He M, Zhu J, Yao P, Li X, Yuan J, et al. Higher carbohydrate antigen 125 levels are associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease in elderly chinese: A population-based case-control study. PLoS One. 2013;8:e81328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]