Abstract

Background:

Under-five children in India continue to die from causes that can either be treated or prevented. The data regarding causes of death, community care-seeking practices, and events prior to death are needed to guide and refine health policies for achieving national goals and targets.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional survey covering rural areas of 16 districts from eight states across India was conducted to understand the causes of deaths and the health-seeking patterns of caregivers prior to the death of such children. Mothers of the deceased children were interviewed. The physician review process was used to assign cause of death. The qualitative data were analyzed as per standard methods, while STATA version 10 was used for analysis of quantitative data.

Findings:

A total of 1,488 death histories were captured through verbal autopsy. Neonatal etiologies, acute respiratory infection (ARI), and diarrhea accounted for approximately 63.1% of all deaths in the under-five age group. The causes of death in neonates showed that birth asphyxia, prematurity, and neonatal infections contributed to more than 67.5% of all neonatal deaths, while in children aged 29 days to 59 months, ARI and diarrhea accounted for 54.3% of deaths. Care providers of 52.6% of the neonates and 21.7% of infants and under-five children did not seek any medical care before the death of the child. Substantial delays in seeking care occurred at home and during transit. For those who received medical care, there was an apparent amongst in their caregivers toward private health providers.

Conclusion:

The deaths of neonates and postneonates taken to any health facilities highlight the need for providing equitable and high-quality health services in India. The findings could be used for policy planning and program refinement in India.

Keywords: Care seeking preceding death, causes of death, child survival, health policy, universal health coverage

Introduction

In the last two decades, the majority of efforts to accelerate child survival have centered around identifying the causes of morbidity and mortality and understanding care-seeking behaviors, and then using that information to scale up interventions to prevent and treat illnesses.(1,2,3,4) Reliable data to guide health policies and programs are needed at least at the state level; however, the countries with the highest child morbidities and mortalities have very limited information available and have weak health information systems.(4,5,6) India contributes to nearly one-fifth of global under-five deaths; the rate of decline is slower and that of mortality much higher than those in countries with similar level of economic development such as Russia, China, Brazil, and South Africa.(7) Very limited recent data are available on the causes of child deaths in India.(8,9) Moreover, the use of causes-of-deaths statistics in India are questionable in view of poor coverage and poor compliance with guidelines (for cause-of-death reporting, coding, and classification)(10) and comparability of various data sources.

This article presents findings from a population-based cross-sectional survey and social autopsy with the objectives to understand the characteristics and determinants and the causes and distribution of child deaths, and to understand the pathway of health seeking adopted by caregivers in the eight states of India.

Materials and Method

This article reports findings from a baseline assessment of the Integrated Management of Neonatal and Childhood Illnesses (IMNCI) program in India. The detailed methodology for this study has been published previously,(11) and relevant information related to this work is summarized in the following paragraphs.

This study was conducted in 16 districts from eight states (two districts per state) across India (Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Odisha, Karnataka, Haryana, Maharashtra, and Meghalaya), using cross-sectional design. These states have a total of 265 districts and a population of about 493 million, which is approximately 45% of all districts and 48% of the total population in India.(12) A total of approximately 6% of the districts and 3.5% of the total population in these states were covered in this study. A sample size of 1500 live births was planned for each district. This sample size was based on the National Family Health Survey-2 (NFHS-2) data to detect under-five mortality rate, infant mortality rate (IMR), and neonatal mortality rate (NMR) with an admissible error of 1% at 95% confidence level. Over 12,800 households (at an estimated average of 6 individuals per household) were expected to be covered per district to capture 1500 live births. All under-five deaths that occurred between April 1, 2005 and March 31, 2006 were identified during household screening and included in the study.

At every study site, two physicians were trained to undertake verbal autopsy along with social autopsy by the members of the Central Coordinating Team (CCT) in a 3-day workshop including hands-on activities in the field. Site visit by CCT members and overseeing during actual data collection was organized as part of quality assurance. The International Clinical Epidemiology Network (INCLEN) Verbal autopsy instrument was adapted from the World Health Organization (WHO) and Population Health Matrix (Johns Hopkins University and Harvard University, USA) verbal autopsy tools available in the public domain.(13) Components for tracking of events before death and social autopsy were added to the verbal autopsy tool. The physician review process [supplementary Figure 1 (342.8KB, tif) ] was used to assign cause of death. Two national experts who were also master trainers for the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) verbal autopsy study trained 10 pediatricians in assigning cause of death. Each death record was reviewed independently by two trained pediatricians. The pediatricians assigned direct and underlying causes based on the International Classification of Diseases Version 10 (ICD-10).(14) The two master trainers played the roles of adjudicators and the third as reviewer. The adjudicator was called upon for opinion in case of disagreement between two primary reviewers and when both primary reviewers labeled the case as “not classified” despite a complete verbal autopsy form. For the first situation, if an adjudicator came up with a cause of death different from the two primary reviewers, the case was labeled as “not classified” cause of death. In the second situation, the adjudicator's cause was accepted as the final diagnosis; however, if he/she also failed to assign a cause of death like both the primary reviewers, such cases were also assigned “not classified” cause of death.

Physician review process for “cause of death” assignment

In addition to causal assignment, information was also obtained for events taking place prior to death including care-seeking practices, treatment obtained, difficulties faced, and place of death. The data were analyzed for delays occurring at home, in transit, and at the health facility. Delay at home was considered if the child:

Did not receive any home remedy and was not taken to any health facility;

Received home remedy and was not taken to health facility; and

Received home remedy and was later taken to a health facility.

Delay during transit was considered to occur in the case of children whose parents enumerated difficulties in reaching the health facility. Delay at health facility was not possible to estimate reliably from the available data and therefore was determined on the basis of three parameters: Deaths occurring at the first health facility; children taken to second and subsequent health facilities; and children who were taken back from the first health facility and who died at home. To obtain the information on events prior to death and care seeking, open-ended questions were also asked to the respondent in addition to the standardized verbal autopsy questions (www.inclentrust.org).

The data were analyzed separately for neonate (1-28 days), postneonate (29 days to 11 months), and childhood (12-59 months) deaths to identify any practices (related to care seeking and sickness management) specifically associated with the particular age groups. Qualitative data analysis was done by a team of social scientists and anthropologists. Key themes emerging from the responses were identified and converted into quantitative variables to link with the cause-of-death data. STATA® version 10 (Stata Corporation 2007) was used for quantitative data analysis. The quality assurance measures and other data analysis process has been published previously.(11)

The ethical approval for the study was obtained from the India-CLEN Institutional Review Board (IRB). The India-CLEN IRB was formed in the year 1999 (FWA No. IRB00004940, in the assurance name of IORG0004172-International Clinical Epidemiology Network, Inc., IRB # 1). In addition, the study was approved by the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), Government of India and written informed consent was obtained from each caretaker before commencing the verbal autopsy interview.

Results

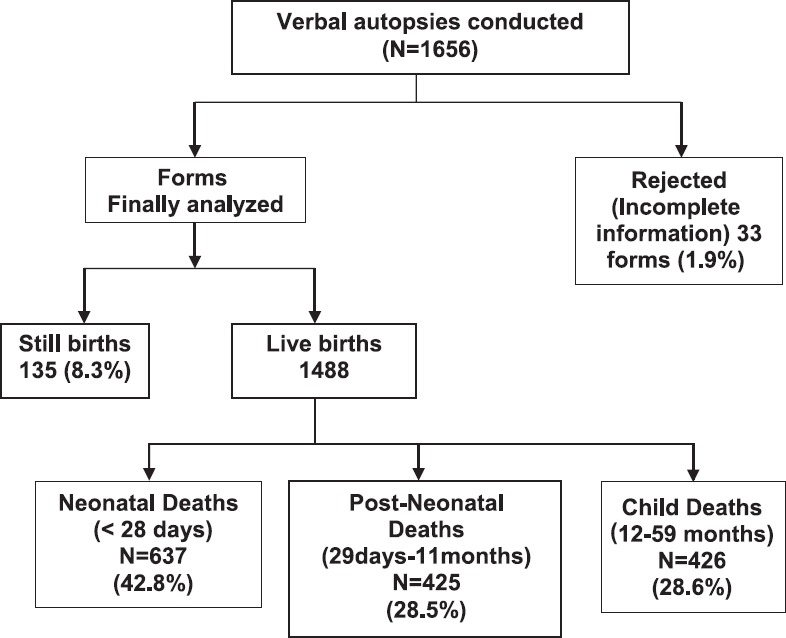

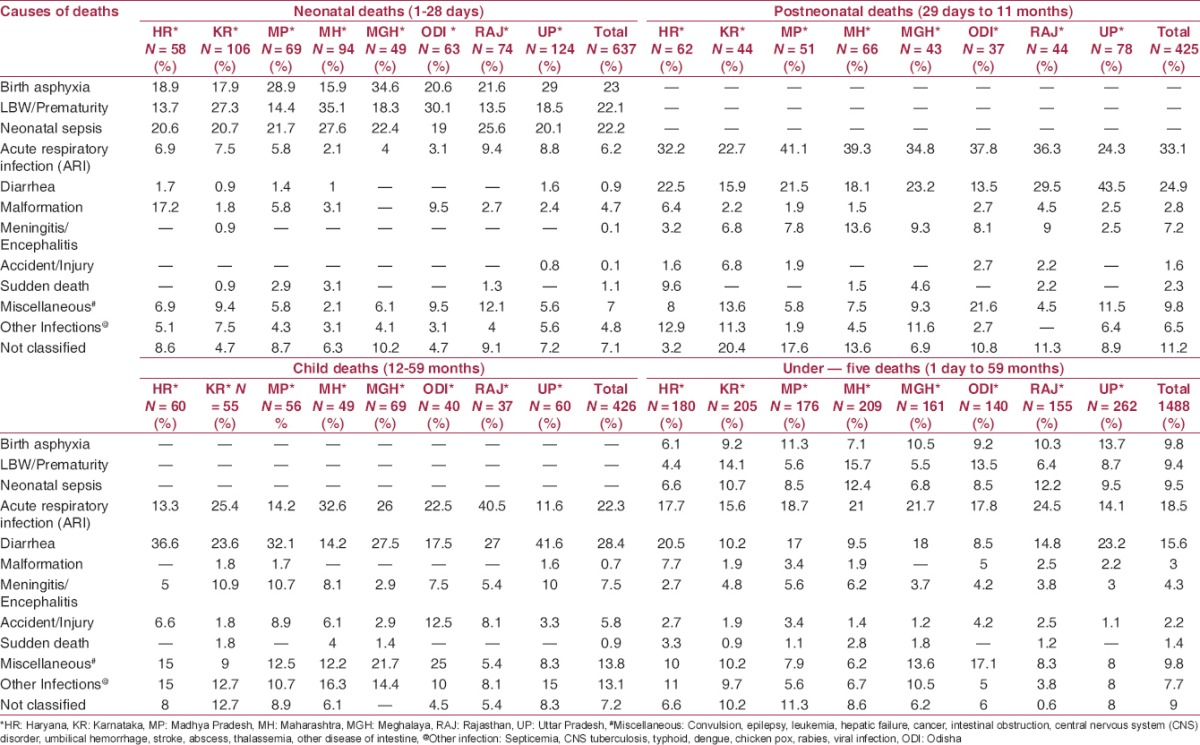

A total of 216,794 households were surveyed, and 1,656 under-five deaths were reported in the study period. A total of 1,488 (91.6%) deaths regarding which there was complete information were included in the final analysis [Figure 1]. For the causes of deaths in the neonatal period, birth asphyxia (23.1%), prematurity/low birth weight (LBW) (22.1%), and sepsis/infections (22.3%) were the top three causes of death, and among the postneonatal deaths (29 days to 11 months), acute respiratory infections (ARI) (33.1%) and diarrhea (24.9%) accounted for the majority of deaths. In children aged 12-59 months, too, ARI (22.3%) and diarrhea (28.4%) were the leading causes [Supplementary Figure 1 (498.3KB, tif) ]. More than half of neonatal deaths (58.7%) occurred in the first 3 days after birth and 44.1% died within 24 h of birth. The cause-of-death data were also analyzed by study state as well [Table 1]. There were variations among the states, in the proportion of deaths caused by each of the top three causes of death in different age subgroups.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of verbal autopsies conducted

Table 1.

State-wise distribution of cause of death among children

Subgroup-wise cause of death among children

Considering that there has been no published study on the prevalence of sudden infant deaths in India, we analyzed data for sudden unexplained deaths. Sudden deaths accounted for 1.4% (21 out of 1488; 7/637 neonates; 10/425 aged between 29 days and 11 months; 4/426 aged 12 months and above) of all deaths. Children with sudden unexplained deaths were reported to be otherwise healthy before death. Only 6 out of 21 children could be taken to a health facility before death.

It was observed that amongst all study subjects in this study, more than half (52.6%) of the neonates were not taken to any health facility; 24.2% infants (29 days to 11 months) and 19.4% children (12-59 months) were also not taken to a health facility or presented to a health provider outside their homes before death. The regression analysis was done for the factors affecting care seeking and it was found that male neonates [adjusted odds ratio (OR) 1.60; 95% confidence interval (CI): 1.14-2.24; P = 0.006], postneonates with diarrhea and pneumonia (adjusted OR 2.05; 95% CI: 1.2-3.2; P = 0.003), and children having mothers with >5 years of schooling (adjusted OR 2.6; 95% CI: 1.1-5.7; P = 0.017) increased the odds of a child being taken to a care provider [Supplementary Table 1 (616KB, tif) ].

Odds ratios for seeking care from any care providers (0=Not visited health facility; 1= Visited health facility) in neonatal and Infant and child deaths

Among those who did seek care from a health provider, government and private health facilities were equally preferred for neonates as the first choice, but for children older than 28 days, there was some preference for a private (42.7%) facility as the first provider over the government (31%). The private facilities became increasingly the preferred choice as parents moved from the first to the second and then the third facility in all age subgroups. Accessibility of the facility (convenience, physical distance, and availability of doctors) and prescriber characteristics (trust and prior experience) emerged as the most important reasons for seeking treatment, followed by quality of care provided from a particular health facility/provider. Arranging transport and social support to take children outside their homes were the consistent challenges faced by the care providers of children in all age categories (data not included in the tables).

Subgroup analysis of causes of death in children taken to health facilities versus those not taken to health facilities [Supplementary Figure 3 (548.2KB, tif) ] was also done. More than half of the neonates who later on died due to birth asphyxia and prematurity were not taken to a health facility prior to death. During the postneonatal period, though the majority of children were taken to health providers, nearly one-fifth of sick children with preventable causes such as diarrhea and ARI were never taken to any health provider, and when the family did decide to take the child to a health provider, the parents frequently visited informal prescribers. There were state-wise differences in the pattern of care seeking; informal private providers were accessed in Uttar Pradesh and Haryana more frequently as compared to other states, and in Odisha, government facilities and providers were preferred over others across age subgroups [Supplementary Table 2 (876.5KB, tif) ].

Causes of deaths and children taken to any health facility and those not taken to health facility

State wise care seeking for type of health facility

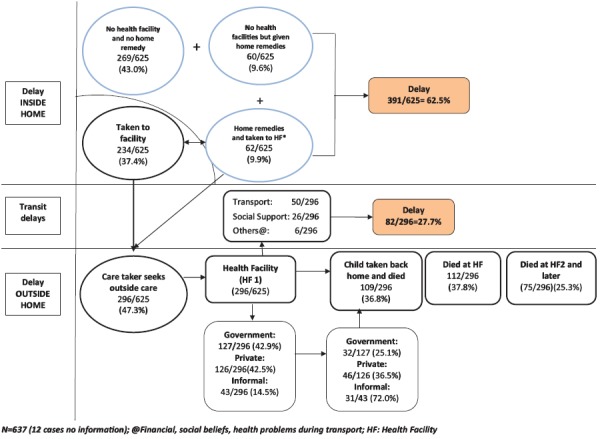

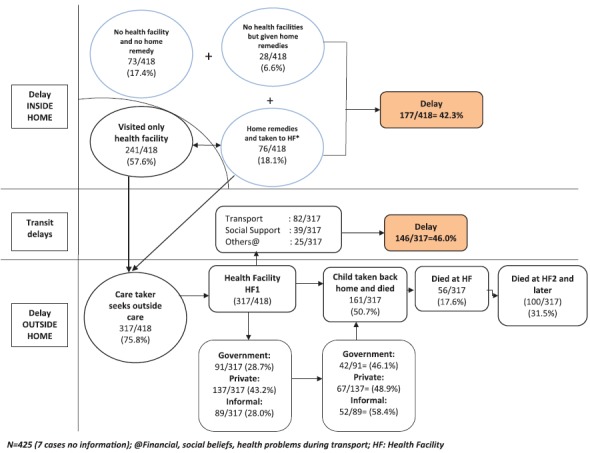

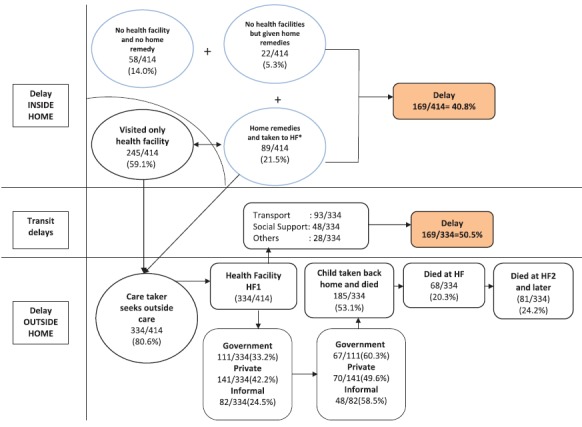

The data were analyzed for delays occurring at home, in transit, and at the health facility, and analyzed for all age groups [Figure 2a–c]. In the neonatal deaths [Figure 2a], delay at home had occurred in 62.5% of cases. Out of 296 newborns who were taken to a health facility, the parents of 82 (27.7%) informed of difficulties in transit. For the postneonatal deaths [Figure 2b], delay at home occurred in 42.3% (177/418) of children; in the majority of these, the delay was due to waiting for the home remedies to have their effect (104/177; (58.7%)). Delay and difficulties in transit (46%) were primarily due to transport problems and lack of social support for carrying the sick child. A similar pattern was noticed for children 12-59 months of age [Figure 2c].

Figure 2a.

Pathway of care seeking preceding death (Neonatal deaths: 1-28 days)

Figure 2b.

Pathway of care seeking preceding death (Postneonatal deaths: 29 days to 11 months)

Figure 2c.

Pathway of care seeking preceding death (Child deaths: 12-59 months)

Discussion

In this study it was noticed that children in India were dying of causes for which life-saving interventions are available.(15,16,17) While the focus of reduction of the under-five mortality rate has generally been on high-burden states in India such as Bihar, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Uttar Pradesh, and Andhra Pradesh,(15) preventable causes of death do prevail in other states too, as identified in the results of our study. The proportion of deaths due to common causes differed significantly between the states. LBW and prematurity were the leading causes of neonatal mortality in Karnataka, Maharashtra, and Odisha. In Uttar Pradesh and Haryana, more children in the postneonatal period died due to diarrhea as compared to ARI; this proportion was reversed in other study states. The majority of these deaths could have been prevented with the interventions offered in primary and secondary care.(18) In the last few years, there has been increasing attention on the presence of skilled birth attendants and institutional delivery through Janani Suraksha Yojna(19) and by setting up sick newborn care units (SNCUs) in all districts of India.(20) Although these interventions have contributed to reduction, the NMRs remain relatively high in India. The same causes of death have variable proportionate contribution to mortality across the states. These observations indicate the possibility of inequitable access and inconsistent quality of available services. This is an area of major programmatic significance, action, and which requires additional research.

This study validated the commonly known facts that female newborns, those born at home, those born in the presence of unskilled workers and those whose caregivers have had less than primary education are at high probability of not being taken to a health facility or a provider for treatment.(21) The government and policy makers should consider strategies under existing initiatives to identify such children for targeted initiatives to improve their survival.

This is probably the first study from India that provides information on rates of Sudden Unexplained Death Syndrome (SUDS), which is an established cause of death in young children.(22) Recently, the issue has attracted wide attention as an adverse event following immunization (AEFI), when new vaccines were introduced into the national programs.(23) In this study, we came across 1.4% deaths that were classified as sudden unexplained deaths and most of them could not be taken to a health facility. We did not have the vaccination history for these children, but according to the Brighton Criteria these children were at level 3 of certainty for unexplained sudden deaths.(22,24) The findings from this study could serve as a baseline for future assessment of SUDS in Indian children and could be used for analysis and in contextualizing SUDS and AEFI deaths in India, which have been often wrongly attributed to new vaccines in the lay press.(25,26) It is equally important not to overlook other causes of death, such as convulsion, cancer, hepatic failure, abscess, and umbilical hemorrhage, which contributed to over 10% of all under-five deaths in our study. Recently, the researchers have emphasized the growing importance of this category of deaths.(27)

The findings in this study suggests that care seeking outside the home gradually increased as age advanced (newborn: 47%; infants beyond neonatal period: 76%; 1-5 years old: 81% P = 0.000). The studies from other developing countries have also reported that the majority of newborns either died at home or on the way to the hospital or in the care of traditional birth attendant (TBA).(28,29) In a recent systematic review of care seeking for neonatal illness in low- and middle-income countries (LMIC), median of 59% care providers sought care outside the home.(29) A survey from India suggested that children aged 1–2 years had higher odds of being taken to any of the health care providers for treatment of diarrhea as compared to children aged <1 year.(30) Multiple factors may delay a caregiver's decision to seek care for their sick children. The delay in care seeking appeared to be due to the inability of the care provider to recognize the child's illness.(31) Several studies have found that the more severe the caregivers perceived the child's illness to be, the more likely they were to seek care.(32,33,34) Therefore, communication strategies for community education on disease severity have the potential to improve care seeking and this deserves serious program attention.

Arranging for transport and social support for accompanying and deciding health care needs are interlinked and were reported to be the major difficulties faced at the household level by families.(35,36,37) During the past decade under the National Health Mission, 108/102 ambulance services have been started to address the transport challenges, particularly for rural and remote areas.(38) We found that the main reasons given for choosing a particular health provider/facility were access (physical distance and availability of health personnel) to that health facility and the prescriber characteristics (trust in service provider). In health care, the patient may trust providers because of their personal relationship, interaction with the health provider, previous experience, and perception of the quality of care provided.(39,40) A consistent pattern in this study was greater confidence in private providers, and several of those who had first approached government facilities moved to private providers. This occurred in spite of the fact that health services are available free of cost at public health facilities.(41,42,43,44) This care-seeking behavior was likely due to the perception of the quality of care and confidence in the private provider over public sector institutions for seriously sick children. The other reason could be lack of diagnostic facilities, or unavailability of qualified personnel at all times, or lack of and low quality of drugs available.(45)

Out of the sick children who were taken to a health facility, 36.8% newborns and 53.1% postneonates were taken back home and died at home. The initial choice of the health provider (formal public, private formal, or informal) did not seem to significantly influence this behavior. Kallander et al. in their study observed that 13% did not receive any treatment from the first provider and 10% did not receive treatment from either the first or the last provider. Of the 40% referred to another health facility, only half adhered to the referral advice.(46) The reasons reported for nonadherence to referral advice included lack of supportive family members to accompany the mother, bad weather, dislike for hospital care, and the infant being too small to be taken outside for care.(47) Factors among caregivers for bringing back their critically sick children after going initially to a health provider are likely to be complex; and requires detailed research.(48)

This study has a number of strengths. First, this is one of the first studies to use similar methods to compare and analyze neonatal, postneonatal, and child deaths. This gives a more reliable comparison than when these are studied by separate researchers or in populations. The second strength is the overall sample size which is one of the largest in India for such studies. Third, never before has such a large sample size been used in a pathway of care in health seeking for children in India. Nonetheless, there are a few limitations as well. The data for this study were collected for the period of 2005-2006, and a few things have changed since then. However, if additional studies are done now, this study could serve as a robust baseline. Another limitation is linked to the method of verbal autopsy being biased by misclassification of causes of death; however, it has been documented that for common causes of death, verbal autopsy does provide reasonable accuracy.(43)

Conclusion

This study based upon data from eight states of India concludes that whether taken to a health provider or not, neonates, infants, and children in India continue to die from preventable causes. The survival of children having the same illness varies between different states, indicating that it is linked to equitable access and consistent availability of services in those states. Private providers and, at times, nonqualified providers are preferred by caregivers over the public sector for their sick children. There are indications that the situation of child health has been showing improvement in the last few years. However, considering that neonatal, infant, and child mortality in India continues to remain high, there is need to consider the following: to design state-specific solutions; to design communication strategies to modify health-seeking behavior, particularly identification of severe illness; to work on quality of care at public health facilities; and increase access to health services in India. The findings are extremely relevant at this point of time when India is drafting a new national health policy and strategies for improving health outcomes. In the times when sustainable development goals are being finalized and the discourse is centered on providing access to quality health services at affordable costs (in other words, universal health coverage), it is imperative that policy makers in India take note of the findings from this study. Appropriate learning and adoption of these findings have the potential to place India on the right trajectory for accelerated child survival and to achieve universal health coverage.

Financial support and sponsorship

The funding for this study was provided by USAID, UNICEF, and The Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Disclaimer

One of the authors, Chandrakant Lahariya was with The INCLEN Trust International as Program Consultant and then as Assistant Professor, Dept. of Community Medicine, GR Medical College, Gwalior, India; during the period when this study was conducted.

The views expressed are personal and do not necessarily represents the decisions, policies or views of the institutions or organizations, they have been affiliated in the past and present.

References

- 1.Geneva (Switzerland): 2010. [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 14]. World Health Organization Statistical Information System (WHO-SIS). Causes of death among children aged less than 5 years. Available from: http://www.who.int/whosis/indicators/mortcauseslessthan5years/en/index.html . [Google Scholar]

- 2.Black RE, Morris SS, Bryce J. Where and why are 10 million children dying every year? Lancet. 2003;361:2226–34. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13779-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lopez AD. Commentary: Estimating the causes of child deaths. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1052–3. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruzicka LT, Lopez AD. The use of cause-of-death statistics for health situation assessment: National and international experiences. World Health Stat Q. 1990;43:249–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perry HB, Ross AG, Fernand F. Assessing the causes of under-five mortality in the Albert Schweitzer Hospital Service area of rural Haiti. Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2005;18:178–86. doi: 10.1590/s1020-49892005000800005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freeman JV, Christian P, Khatry SK, Adhikari RK, LeClerq SC, Katz J, et al. Evaluation of neonatal verbal autopsy using physician review versus algorithm-based cause-of-death assignment in rural Nepal. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2005;19:323–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2005.00652.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joint statistical publication by BRIC countries: Brazil, Russia, India, China/IBGE, 2010. Instituto Brasileiro de Geografiae Estatística- IBGE. Brazil. [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 14]. ISBN 978-85-240-4116-7. Available from: http://www.ibge.gov.br/home/presidencia/noticias/pdf/BRIC.pdf .

- 8.Jha P, Gajalakshmi V, Gupta PC, Kumar R, Mony P, Dhingra N, et al. RGI-CGHR Prospective Study Collaborators. Prospective study of one million deaths in India: Rationale, design, and validation results. PLoS Med. 2006;3:e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.0030018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lichtenthal WG, Neimeyer RA, Currier JM, Roberts K, Jordan N. Cause of death and the quest for meaning after the Loss of a child. Death Stud. 2013;37:311–42. doi: 10.1080/07481187.2012.673533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Morris SS, Black RE, Tomaskovic L. Predicting the distribution of under-five deaths by cause in countries without adequate vital registration systems. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32:1041–51. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lahariya C, Dhawan J, Pandey RM, Chaturvedi S, Deshmukh V, Dasgupta R, et al. Inter-district variations in child health status and health services utilization: Lessons for health sector priority setting and planning from a cross-sectional survey in rural India. Natl Med J India. 2012;25:137–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New Delhi: Office of the Registrar General of India and Census Commissioner India; 2006. Office of Registrar General of India. Census of India 2001: Population projections for India and states 2001-2026: Report of the technical group on population projections constituted by the National Commission on population; pp. 80–198. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Murray CJ, Lopez AD, Black R, Ahuja R, Ali SM, Baqui A, et al. Population health matrics research consortium gold standard verbal autopsy validation study: Design, implementation, and development of analysis datasets. Popul Health Metr. 2011;9:27. doi: 10.1186/1478-7954-9-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Geneva (Switzerland): World Health Organization; 1994. [Last accessed on 2014 Apr 14]. World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. Ten revisions (ICD-10) Available from: http://www.who.int/classifications/icd/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lahariya C, Paul VK. Burden, differential, and causes of child deaths in India. Indian J Pediatr. 2010;77:1312–21. doi: 10.1007/s12098-010-0185-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bassani DG, Kumar R, Awasthi S, Morris SK, Paul VK, Shet A, et al. Million Death Study Collaborators. Causes of neonatal and child mortality in India: A nationally representative mortality Survey. Lancet. 2010;376:1853–60. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61461-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lawn JE, Cousens S, Zupan J. Lancet Neonatal Survival Steering Team. 4 million neonatal deaths: When? Where? Why? Lancet. 2005;365:891–900. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhandari N, Mazumder S, Taneja S, Sommerfelt H, Strand TA. IMNCI Evaluation Study Group. Effect of implementation of integrated management of neonatal and childhood illness (IMNCI) programme on neonatal and infant mortality: Cluster randomized controlled trial. BMJ. 2012;344:e1634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Randive B, Diwan V, De Costa A. India's conditional cash transfer programme (the JSY) to promote institutional birth: Is there an association between institutional birth proportion and maternal mortality? PLoS One. 2013;8:e67452. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0067452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sen A, Mahalanabis D, Singh AK, Som TK, Bandyopadhyay S, Roy S. Newborn aides: An innovative approach in sick newborn care at a district-level special care unit. J Health Popul Nutr. 2007;25:495–501. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghosh N, Chakrabarti I, Chakraborty M, Biswas R. Factors affecting the healthcare-seeking behavior of mothers regarding their children in a rural community of Darjeeling district, west Bengal. International J Med Public Health. 2013;3:12–6. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jorch G, Tapianinen T, Bonhoeffer J, Fischer TH, Heininger U, Hoet B, et al. Brighton Collaboration Unexplained Sudden Death Working Group. Unexplained sudden death, including sudden death syndrome (SIDS), in the first and second years of life: Case definition and guidelines for collection, analysis and presentation of immunization safety data. Vaccine. 2007;25:5707–16. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2007.02.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Adverse event following immunization (AEFI). Surveillance and response: Operational guidelines. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. 2010. [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.pbhealth.gov.in/Immunization/AEFI_Guidelines.pdf .

- 24.Kohl KS, Bonhoeffer J, Braun MM, Chen RT, Duclos P, Heijbel H, et al. The Brighton Collaboration: Creating a Global Standard for Case Definitions (and Guidelines) for Adverse Events Following Immunization. [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 10];Advances in Patient Safety. 2:18–102. Available from: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/quality-patient-safety/patient-safety-resources/resources/advances-in-patient-safety/vol2/Kohl.pdf . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Puliyel J. AEFI and the pentavalent vaccine: Looking for a composite picture. Indian J Med Ethics. 2013;10:142–6. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2013.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vol. 88. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2013. Weekly epidemiological record; pp. 301–12. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu L, Oza S, Hogan D, Perin J, Rudan I, Lawn JE, et al. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000-13, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: An updated systematic analysis. Lancet. 2015;385:430–40. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mrisho M, Schellenberg D, Manzi F, Tanner M, Mshinda H, Shirima K, et al. Neonatal deaths in rural southern Tanzania: Care-seeking and causes of death. ISRN Pediatr 2012. 2012:953401. doi: 10.5402/2012/953401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Waiswa P, Kallander K, Peterson S, Tomson G, Pariyo GW. Using the three delays model to understand why newborn babies die in eastern Uganda. Trop Med Int Health. 2010;15:964–72. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2010.02557.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sreeramareddy CT, Sathyanarayana TN, Kumar HN. Utilization of health care services for childhood morbidity and associated factors in India: A national cross sectional household survey. PLos One. 2012;7:e51904. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Upadhyay RP, Rai SK, Krishnan A. Using three delays model to understand the social factors responsible for neonatal deaths in rural Haryana, India. J Trop Pediatr. 2013;59:100–5. doi: 10.1093/tropej/fms060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yoder PS, Hornik RC. Perception of severity of diarrhea and treatment choice: A comparative study of Health-Com sites. J Trop Med Hyg. 1994;97:1–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Babaniyi OA, Maciak BJ, Wambai Z. Management of diarrhea at the household level: A population-based survey in Suleja, Nigeria. East Afr Med J. 1994;71:531–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Langsten R, Hill K. Treatment of childhood diarrhea in rural Egypt. Soc Sci Med. 1995;40:989–1001. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)00163-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Syed U, Khadka N, Khan A, Wall S. Care-seeking practices in South Asia: Using formative research to design program interventions to save newborns lives. J Perinatol. 2008;28(Suppl 2):S9–13. doi: 10.1038/jp.2008.165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sutrisna B, Reingold A, Kresno S, Harrison G, Utomo B. Care-seeking for fatal illnesses in young children in Indramayu, West Java, Indonesia. Lancet. 1993;342:787–9. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)91545-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warren C. Care of the newborn: Community perceptions and health seeking behavior. Ethiop J Health Dev. 2010;24:110–4. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Framework for implementation. National Health Mission 2012-2017. Ministry of health and family welfare, Government of India. [Last accessed on 2015 Oct 10]. Available from: http://www.nrhm.gujarat.gov.in/Images/pdf/nhm_framework_for_implementation.pdf .

- 39.Ozawa S, Walker DG. Comparison of trust in public vs private health care providers in rural Cambodia. Health Policy Plan. 2011;26(Suppl 1):i20–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czr045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gautham M, Binnendijk E, Koren R, Dror DM. First we go to small doctor:First contact for curative health care sought by rural communities in Andhra Pradesh and Orissa, India. Indian J Med Res. 2011;134:627–38. doi: 10.4103/0971-5916.90987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.De Costa A, Diwan V. Where is the public health sector. Public and private sector healthcare provision in Madhya Pradesh, India? Health Policy. 2007;84:269–76. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kumar C, Prakash R. Public-Private Dichotomy in Utilization of Health Care Services in India. Consilience: J Sustainable Dev. 2011;5:25–52. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peters DH, Sharma RR, Ramana NV, Pritchett LH, Wagstaff A. Washington DC (USA): World Bank; 2002. [Last accessed on 2013 Apr 14]. Better health systems for India's poor: Findings, analysis, and options. Available from: http://www-wds.worldbank.org/servlet/WDSContentServer/WDSP/IB/2002/05/30/000094946_02051604053640/Rendered/PDF/multi0page.pdf . [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bhatia J, Cleland J. Health care of female outpatients in south-central India: Comparing public and private sector provision. Health Policy Plan. 2004;19:402–9. doi: 10.1093/heapol/czh055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kahabuka C, Kvale G, Moland KM, Hinderaker SG. Why caretakers bypass primary health care facilities for child care- a case from rural Tanzania. BMC Health Serv Res. 2011;11:15. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-11-315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Källander K, Hildenwall H, Waiswa P, Galiwango E, Peterson S, Pariyo G. Delayed care seeking for fatal pneumonia in children aged under five years in Uganda: A case-series study. Bull World Health Organ. 2008;86:332–8. doi: 10.2471/BLT.07.049353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bari S, Mannan I, Rahman MA, Darmstad GL, Serajil MH, Baqui AH, et al. Bangladesh Projahnmo-II Study Group. Trends in use of referral hospital services for care of sick newborns in a community based intervention in Tangail District, Bangladesh. J Health Popul Nutr. 2006;2:519–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.de Zoysa ID, Bhandari N, Akhtari N, Bhan MK. Careseeking for illness in young infants in an urban slum in India. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47:2101–11. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00275-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Physician review process for “cause of death” assignment

Subgroup-wise cause of death among children

Odds ratios for seeking care from any care providers (0=Not visited health facility; 1= Visited health facility) in neonatal and Infant and child deaths

Causes of deaths and children taken to any health facility and those not taken to health facility

State wise care seeking for type of health facility