1. Introduction

Hip fracture is a painful orthopedic emergency associated with significant morbidity and mortality in elderly patients [1,2]. Uncontrolled pain from a hip fracture can induce anxiety, fear and delirium [3,4]. In patients with a hip fracture, delirium is associated with poor functional recovery and increased mortality [5–7].

Patients with acute hip fracture are often initially evaluated in the Emergency Department (ED), where treatment with systemic opioids is commonly employed for pain relief. However, opioid-related side effects including nausea, hypotension and altered mentation occur with increased frequency in elderly patients. Concern for these adverse effects may lead to under-dosing of systemic analgesics in this patient population. Oligoanalgesia may lead to continued pain for these patients, as they await definitive surgical repair [8–10].

Regional anesthesia offers a viable alternative to systemic opioids and is strongly endorsed for preoperative pain control in patients with hip fracture by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons [11]. Specifically, femoral nerve block (FNB) has been established as an effective method for pain control in patients who have sustained this type of injury [12]. A recent review described the enhanced efficacy of regional nerve blocks when compared to standard analgesic practices in patients with hip fracture [13]. In addition, patients in these studies who received regional analgesia required a smaller amount of opioids for pain relief.

Sonographic guidance of nerve blocks is associated with a lower incidence of inadvertent intravascular injection, a faster time to onset of pain relief, and a smaller amount of local anesthetic required for pain relief [14–16]. Multiple studies have specifically demonstrated that sonographic guidance of FNB is associated with improved safety of this procedure by allowing the visualization of neurovascular structures, which ensures accurate placement of injectate [17–21].

The use of point-of-care ultrasonography is a mandatory component of Emergency Medicine residency training, and Emergency Physicians are increasingly utilizing this technology for procedural guidance. USFNB has been specifically studied, and it was demonstrated that the technique to perform this procedure can be successfully taught to first year Emergency Medicine residents [23]. In addition, previous studies have effectively used USFNB to control pain from hip fracture in the emergency department [17–18].

The hip is a complex joint which is innervated anteriorly by branches of the femoral and obturator nerves and posteriorly by branches of the sciatic and superior gluteal nerves. The skin overlying the hip joint receives sensory innervation from the lateral femoral cutaneous nerve. Hip fractures are classified as intracapsular (IC), composed of subcapital, transcervical, and basicervical fractures, or extracapsular (EC), which consists of intertrochanteric and subtrochanteric fractures. Different branches of the nerves which provide sensory innervation of the hip may be affected depending on whether the patient has an IC vs. EC hip fracture. To our knowledge, no study has investigated whether ultrasound guided FNB (USFNB) is effective in both EC and IC hip fractures. In this subgroup analysis, we used data from a multicenter, prospective, randomized, clinical trial to examine the differences in pain relief provided by USFNB in these two types of hip fractures. We hypothesized that USFNB would be equally effective in providing pain relief in IC and EC hip fractures.

2. Materials and Methods

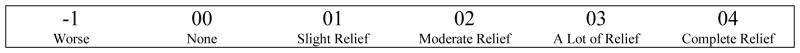

This was a subgroup analysis of a multicenter, prospective, randomized, clinical trial comparing USFNB to routine analgesic care (i.e. no USFNB) in patients presenting with pain due to hip fracture at three academic medical centers. The study enrolled a convenience sample of patients aged 60 or older presenting with a hip fracture and was approved by each institution’s IRB. Patients were randomized after radiographic confirmation of fracture into one of two treatment arms: USFNB or standard analgesic care. Investigators used 20ml of 0.5% bupivacaine to perform the femoral nerve block. All participants were asked to assess their pain using an 11-point numerical rating scale (NRS). Baseline NRS were recorded at study enrollment and 2 and 3 hours subsequently. In addition, participants evaluated their degree of pain relief using a 6-point numeric rating scale (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Pain relief numeric rating scale.

In this analysis, we analyzed data for patients enrolled into the USFNB arm only. The primary outcome was the difference in pain reduction provided by USFNB between two types of hip fractures at the 2 and 3 hour time points. We used an independent sample t-test to assess the difference in pain scores between the two groups of fractures at each time point and a paired t-test to assess the difference from baseline to each time point within both groups.

2.1 Selection of Participants

Patients were eligible to be included in the clinical trial if they were aged 60 or older, had a confirmed radiographic diagnosis of hip fracture and were able to demonstrate understanding of informed consent. Exclusion criteria included the following: the patient was less than 60 years old, the patient was not communicative, or the patient had an allergy to opioids or local anesthetics. See Table 1 for a full list of exclusion criteria.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics.

| Intracapsular | Extracapsular | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| N(%)/Mean(SD) | N(%)/Mean(SD) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 11 (35.48%) | 7 (18.92%) | 0.12 |

| Female | 20 (64.52%) | 30 (81.08%) | |

|

| |||

| Age (mean) | 79.71 (7.79) | 85.08 (6.89) | 0.004 |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| White | 25 (80.65%) | 34 (91.89%) | 0.27 |

| Black | 4 (12.90%) | 1 (2.70%) | |

| More than 1 Race | 2 (6.45%) | 2 (5.41%) | |

|

| |||

| Ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic/Latino | 3 (9.68%) | 1 (2.70%) | 0.49 |

| Not Hispanic/Latino | 27 (87.10%) | 34 (91.89%) | |

| Unknown | 1 (3.23%) | 2 (5.41%) | |

|

| |||

| Length of Stay (mean) | |||

| 7.77 (4.97) | 7.81 (8.06) | 0.43 | |

2.2 Interventions

Study investigators used a Zonare z.one ultrasound machine (Zonare, Mountain View, California) with a high-frequency linear transducer. With the patient in a supine position, the probe was first placed along the femoral crease to view the fascia iliaca and the femoral artery. The femoral nerve was then identified as a hyperechoic structure, positioned lateral to the pulsating artery and deep to the fascia iliaca. After the skin was prepped with antiseptic solution and using sterile technique, a 22-gauge spinal needle was advanced using an out-of-plane technique. The advancement of the needle was visualized in order to decrease the risk of inadvertent vascular puncture and to ensure the proper placement of local anesthetic. Every study patient had a physical examination, including a neurovascular assessment, performed either by the Emergency Physician, the Orthopedist, or both, prior to performing the nerve block.

3. Results

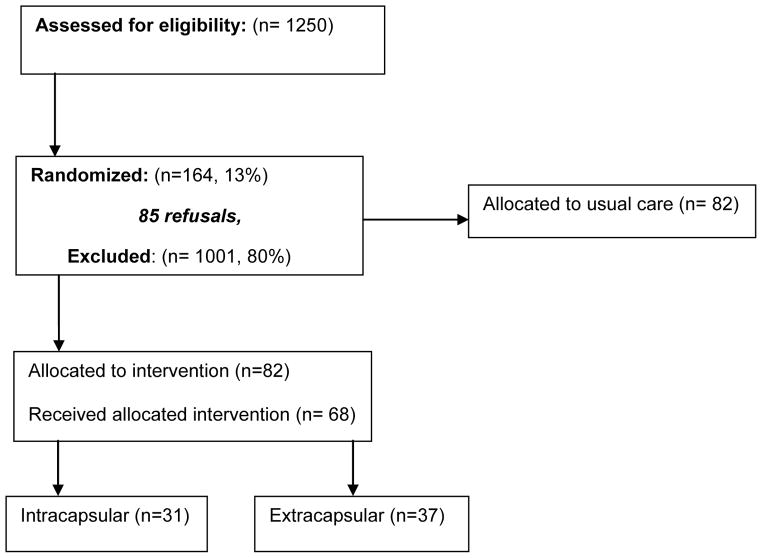

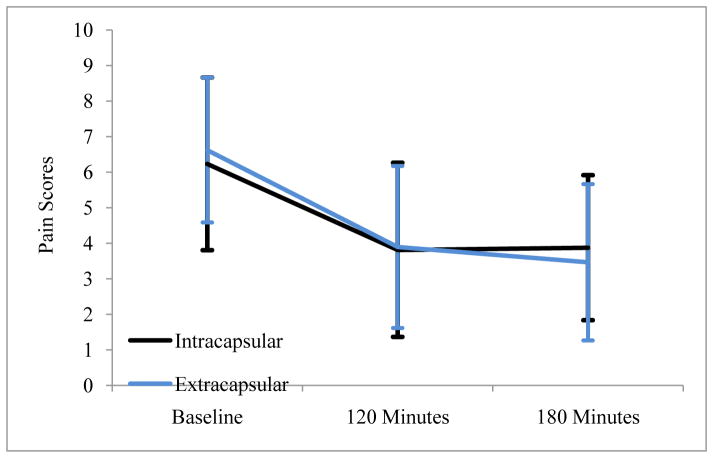

Of the 77 participants who were enrolled to receive USFNB, 36 were diagnosed with IC fracture and 41 with EC hip fracture (Figure 2). We included the 31 IC and 37 EC patients with pain assessments completed at all 3 points. On average, patients with IC fractures were younger than patients with EC fractures (79.71 vs. 85.08, P < 0.005). Besides age, there were no significant demographic differences between the two groups (Table 2). In both groups, reductions in pain scores were clinically and statistically significant at 2 and 3 hours post baseline (Table 3). These differences were similar between EC and IC groups at 2 hours (P = 0.92), and at 3 hours (P = 0.58), thus demonstrating similar reduction in pain in the two groups (Figure 3). The differences in pain relief between IC and EC groups were also similar: 1.61 (1.14, 2.08) vs. 1.35 (0.96, 1.75) at 2 hours (P = 0.39) and 1.68 (1.21, 2.15) vs. 1.38 (0.89, 1.87) at 3 hours (P = 0.38). Based on post-intervention chart review and daily patient assessments by clinical interviewers, none of the patients who received a USFNB developed an infection due to this procedure.

Figure 2.

Participant flow diagram.

Table 2.

Patient outcomes.

| Outcomes | Mean (95% CI) | p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Intracapsular [n= 31] | within p-value | Extracapsular [ n= 37 ] | within p-value | between p-value | |

| Mean pain scores at baseline | 6.23 (5.01, 7.44) | 6.62 (5.60, 7.64) | 0.61 | ||

| Pain scores at 2 hours | 3.81 (2.58, 5.03) | 3.89 (2.75, 5.03) | 0.92 | ||

| Pain scores at 3 hours | 3.87 (2.73, 4.77) | 3.46 (2.36, 4.56) | 0.58 | ||

| Pain Relief 2 Hours | 1.61 (1.14, 2.08) | 1.35 (0.96, 1.75) | 0.39 | ||

| Pain Relief 3 Hours | 1.68 (1.21, 2.15) | 1.38 (0.89, 1.87) | 0.38 | ||

| Pain difference 2 hrs vs. Baseline | 2.42 (1.29, 3.55) | <0.0001 | 2.73 (1.65, 3.81) | <0.0001 | 0.69 |

| Pain difference 3 hrs vs. Baseline | 2.35 (1.35, 3.36) | <0.0001 | 3.16 (2.11, 4.21) | <0.0001 | 0.27 |

Table 3.

Exclusion criteria.

| EXCLUSION CRITERIA |

|---|

| a. The patient is less than 60 years old. |

| b. The patient does not speak English |

| c. The patient has been transferred from the inpatient service of another hospital after the surgical repair of a hip fracture. |

| d. The patient experienced major internal injuries to the chest, abdomen, or pelvis concurrently with the hip fracture. |

| e. Pathologic fracture due to malignancy that is suspected on the basis of either pathologic, radiologic, or other diagnostic tests and accompanies a known or newly diagnosed cancer. |

| f. The fracture is limited to the pelvis or acetabulum. |

| g. The fracture is in the shaft of the femur only. |

| h. The fracture of the proximal femur starts more than 2 cm below the lesser trochanter. |

| i. The patient has bilateral hip fractures. |

| j. The patient had a previous hip fracture on the same side. |

| k. The patient has undergone surgery on the same hip prior to this fracture. |

| l. The patient is non-communicative. |

| m. The patient has an allergy to opioids, bupivicaine or local anesthetics. |

| n. The patient was admitted to the emergency department > 72 hours from the onset of symptoms or fall. |

| o. There is documentation of drug or alcohol abuse. |

| p. There is documentation of medical history of a bleeding problem. |

| q. The patient scored less than 4 on the Six Item Screener. |

Figure 3.

Patient Reported pain with 95% Confidence Interval bars.

4. Discussion

The incidence of hip fractures is expected to rise as the population continues to age [22]. Pain caused by a hip fracture can be severe and therefore requires safe and effective treatment. Failure to treat pain in elderly patients is associated with development of delirium, which can impede treatment and recovery [4]. Morphine or other opiates remain a commonly utilized analgesic class for patients in pain from hip fracture in the ED. However, untoward side effects of these medications can be exacerbated in the elderly. US-guided regional analgesia has been demonstrated to be safe and effective in treating pain from hip fracture [17–19].

This is the first study to demonstrate that USFNB provides equivalent pain relief in both EC and IC hip fractures. One of the major limitations of the analysis is that data was obtained only at the 2 and 3 hour time points. It is difficult to predict whether similar reductions in pain relief would continue after 3 hours. The focus of this analysis was on pain relief during the initial treatment, while patients were still in the ED. USFNB serves as an excellent alternative to traditional opioid treatment, thus presenting a means to improve care in this patient population.

5. Conclusion

USFNB is equally effective in reducing pain from hip fracture in both IC and EC subtypes. Health care providers offering emergency care to elderly patients who have sustained an IC or EC hip fracture should strongly consider using USFNB to treat pain.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: The study was funded by grant from National Institute on Aging (R01 AG030141-05).

Footnotes

Presentation of Results: Oral presentation at the SAEM Mid-Atlantic Regional meeting on February 28th, 2015 in Washington, DC. Oral presentation at New York ACEP on July 7th, 2015 in Sagamore, NY.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Keene GS, Parker MJ, Pryor GA. Mortality and morbidity after hip fractures. BMJ. 1993;307:1248–50. doi: 10.1136/bmj.307.6914.1248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Roberts HC, Eastwood H. Pain and its control in patients with fractures of the femoral neck while awaiting surgery. Injury. 1994;25:237–9. doi: 10.1016/0020-1383(94)90070-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Layzell MJ. Use of femoral nerve blocks in adults with hip fractures. Nursing Standard. 2013;27:49–56. doi: 10.7748/ns2013.08.27.52.49.e7390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morrison RS, Magaziner J, Gilbert M, Koval KJ, McLaughlin MA, Orosz G, Strauss E, Siu AL. Relationship between pain and opioid analgesics on the development of delirium following hip fracture. J Gerontol A: Biol Med Sci. 2003;58:M76–M81. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.1.m76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Marcantonio ER, Flacker JM, Michaels M, et al. Delirium is independently associated with poor functional recovery after hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:618–624. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb04718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dolan MM, Hawkes WG, Zimmerman SI, et al. Delirium on hospital admission in aged hip fracture patients: prediction of mortality and 2-year functional outcomes. J Gerontol Med Sci. 2000;55A:M527–M534. doi: 10.1093/gerona/55.9.m527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rockwood K. Delays in the discharge of elderly patients. J Clin Epidemiol. 1990;43:971–975. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(90)90080-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Platts-Mills TF, Esserman DA, Brown DL, Bortsov AV, Sloane PD, McLean SA. Older US emergency department patients are less likely to receive pain medication than younger patients: results from a national survey. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60:199–206. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.09.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jones JS, Johnson K, McNinch M. Age as a risk factor for inadequate emergency department analgesia. Am J Emerg Med. 1996;14:157–60. doi: 10.1016/S0735-6757(96)90123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang U, Richardson LD, Sonuyi TO, Morrison RS. The effect of emergency department crowding on the management of pain in older adults with hip fracture. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54:270–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2005.00587.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. [Accessed on: Jun 1st, 2015];Management of Hip Fractures in the Elderly: Evidence- Based Clinical Practice Guideline. 2014 Available from: http://www.aaos.org/research/guidelines/HipFxGuideline.pdf.

- 12.Parker MJ, Griffiths R, Appadu B. Nerve blocks (subcostal, lateral cutaneous, femoral, triple, psoas) for hip fractures. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(1):CD001159. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Riddell M, Ospina M, Holroyd-Leduc J. Use of Femoral Nerve Blocks to Manage Hip Fracture Pain among Older Adults in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review. CJEM. 2015;10:1–8. doi: 10.1017/cem.2015.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marhofer P, Schrögendorfer K, Koinig H, Kapral S, Weinstabl C, Mayer N. Ultrasonographic guidance improves sensory block and onset time of three-in-one blocks. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:854–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marhofer P, Schrögendorfer K, Wallner T, Koinig H, Mayer N, Kapral S. Ultrasound guidance reduces the amount of local anesthetic for 3-in-1 blocks. Reg Anesth Pain. 1998;23:584–8. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(98)90086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barrington MJ1, Kluger R. Ultrasound guidance reduces the risk of local anesthetic systemic toxicity following peripheral nerve blockade. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2013;38:289–97. doi: 10.1097/AAP.0b013e318292669b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Beaudoin FL, Nagdev A, Merchant RC, Becker BM. Ultrasound-guided femoral nerve blocks in elderly patients with hip fractures. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28:76–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beaudoin FL, Haran JP, Liebmann O. A comparison of ultrasound-guided three-in-one femoral nerve block versus parenteral opioids alone for analgesia in emergency department patients with hip fractures: a randomized controlled trial. Acad Emerg Med. 2013;20:584–91. doi: 10.1111/acem.12154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marhofer P, Schrogendorfer K, Wallner T, Koinig H, Mayer N, Kapral S. Ultrasonographic guidance reduces the amount of local anesthetic for 3-in-1 blocks. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 1998;23:584–8. doi: 10.1016/s1098-7339(98)90086-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Marhofer P, Schrogendorfer K, Koinig H, Kapral S, Weinstabl C, Mayer N. Ultrasonographic guidance improves sensory block and onset time of three-in one blocks. Anesth Analg. 1997;85:854–7. doi: 10.1097/00000539-199710000-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reid N, Stella J, Ryan M, Ragg M. Use of ultrasound to facilitate accurate femoral nerve block in the emergency department. Emerg Med Australas. 2009;21:124–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-6723.2009.01163.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gullberg B, Johnell O, Kanis JA. World-wide projections for hip fracture. Osteoporosis International. 1997;7:407–13. doi: 10.1007/pl00004148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Akhtar S, Hwang U, Dickman E, Nelson BP, Morrison RS, Todd KH. A brief educational intervention is effective in teaching the femoral nerve block procedure to first-year emergency medicine residents. J Emerg Med. 2013;45:726–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.04.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]