Abstract

Purpose

We aim to determine the incidence rates (IR) of first ever PTSD and depression in a population-based cohort of US Reserve and National Guard service members.

Methods

We used data from the US Reserve and National Guard Study (N = 2003) to annually investigate incident and recurrent PTSD and depression symptoms from 2010 to 2013. We estimated the IR and recurrence rate over 4 years and according to several sociodemographic and military characteristics.

Results

From 2010 to 2013, incidence rates were 4.7 per 100 person-years for both PTSD and depression symptoms using the sensitive criteria, 2.9 per 100 person-years using the more specific criteria, recurrence rates for both PTSD and depression were more than 4 times as high as IRs, and IRs were higher among those with past-year civilian trauma, but not past-year deployment.

Conclusions

The finding that civilian trauma, but not past-year military deployment, is associated with an increased risk of PTSD and depression incidence suggest that RNG psychopathology could be driven by other, non-military, traumatic experiences.

Keywords: Stress Disorder, Post-traumatic, Stress, Psychological, Depression, Mental Disorders, Incidence, Military Personnel, Cohort Studies, Prospective Studies

Introduction

Mental illness is a major health concern in the US armed forces, particularly among the Reserves and National Guard (reserve component) (1). The reserve component includes more than 1.2 million Army and Air Nation Guardsmen and members of the Army, Navy, Marine, Air Force, and Coast Guard Reserve. Whereas the active component deploy worldwide at the command of the President or Congress, the National Guard largely supports individual states and reserves are a trained operational force in reserve ready to augment active component forces when required. After the Vietnam War, however, the Department of Defense adopted the Total Force Policy that treated the 2 components (i.e., active and reserve component) as a single operational force. Thus, during the height of mobilization in Operation Enduring Freedom and Operation Iraqi Freedom and (OEF/OIF), reserve component forces constituted about 40% of deployed service members in combat operations.

Investigations to date have indicated that the reserve component suffers a greater burden of psychiatric disorders compared to the active component, specifically depression and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (1–4). Studies have shown that the combined prevalence of depression and PTSD is about 20% in the general reserve population (3, 5) and more than 30% in postdeployment reservists (2, 6, 7). Incidence estimates are much harder to come by and absent incidence estimates our understanding of the contribution to this prevalence of new onset disease compared to disease duration remains unknown. Furthermore, there are no studies that have considered incidence among Reserve and National Guard service members, which leaves a substantial data-gap that can inform approaches to try to minimize the development of mental illness among this population.

Three gaps exist in understanding the risk of depression and PTSD in the military. First, extant military studies have reported either the cross-sectional prevalence or proportion of “new-onset” cases. New-onset cases are qualified only by the absence of a disorder at the baseline interview and disorder diagnosis at a later interview, rather than absence of a lifetime history of disorder at baseline. Because depression and PTSD can be chronic and recurrent disorders (8, 9) and new-onset estimates conflate first incidence disorders with recurrent disorders (i.e., disorders absent at baseline interview but present at later wave), new-onset estimates are likely to overestimate first onset incidence rates. Therefore, the accurate assessment of mental disorder risk during military services requires that lifetime symptoms be assessed at baseline. Second, much of what we know about the risk of and burden for depression and PTSD in the military comes from active duty personnel. Generalizability of risk estimates derived from active duty forces to reservists may be limited given reservists' unique experiences as citizen-soldiers. Specifically, reservists are part-time soldiers—generally serving one weekend a month and 15 days annually; however, this dual role as citizen-soldiers also contributes to unique stressors not experienced by active-duty forces (e.g., cycling between civilian employment and military deployments, limited access to mental health services). Finally, much of what we do know about reservists mental illness burden is based on highly localized samples (10). As previous civilian studies have documented that mental disorder prevalence varies by state, a nation-wide sample of Reserve and National Guard service members is needed to estimate incidence rates in this population.

We aimed to determine incidence and recurrence rates of PTSD and depression in a population-based cohort study of US Reserve and National Guard service members. To this end we used the Reserve National Guard (RNG) study to document first incidence rates of PTSD and depression, and their predictors.

Material and methods

Study population

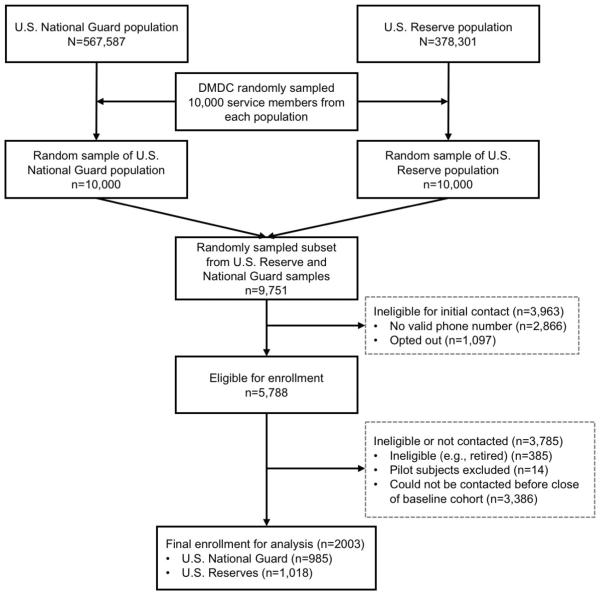

Launched in 2009, the RNG study was a 4-year prospective cohort study that aimed to collect and evaluate population-based data on psychiatric health in the reserve component. To obtain a nationally representative sample of reservists, a stratified random sample was selected in 2 distinct phases. First, the Defense Manpower Data Center (DMDC) provided a random sample of Reserve (n=10,000) and National Guard (n=10,000) soldiers serving as of June 2009. Second, we selected a random sample of 9,751 service-members (4,788 National Guard; 4,963 Reserve) and mailed information about the study along with an opt-out letter and 1,097 opted-out. Next, we excluded 2,866 with incorrect/non-working telephone numbers, 385 who were not eligible (e.g., hearing problem, retired), 1,097 who did not wish to participate, 14 who only completed pilot surveys, and 3,386 who had not yet been contacted when we reached our target sample size (N ≥ 2,000) (Fig. 1). A total of 2,003 Reserve and National Guard service members were interviewed at baseline (January–July 2010). Using American Association for Public Opinion Research definitions (11), the overall cooperation rate was 68.2%, and the response rate was 34.1%.; both rates are comparable to other population-based military cohort studies, such as Army STARRS (65.1% and 49.8%, respectively; 8). Complex survey weights were constructed to account for sampling design, demographic factors associated with baseline non-response, and poststratification adjustments based on the characteristics of the entire population at time of sampling in 2009. Weights for waves 2, 3, and 4 were adjusted for follow-up interview non-response. A more detailed description of the RNG study and weighting procedures is presented elsewhere (12).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for a cohort of U.S. National Guard and Reserve, 2010 to 2013. DMDC, Defense Manpower Data Center.

Study procedures and measures

Study trained interviewers obtained informed consent, administered a 60-minute telephone interview using computer assisted telephone interview (CATI) technology, and offered $25 compensation. The Human Research Protection Office at the U.S. Army Medical Research and Materiel Command (MRMC) and institutional review boards at both Columbia University and Uniformed Service University of the Health Sciences approved all study protocols.

Assessment of posttraumatic stress disorder

The PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) (13) is a 17-item measure that is validated to assess the severity of symptoms related to any lifetime stressor (i.e., self-selected “worst” trauma experienced), which maps onto the 17 Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) symptoms. While the PCL is structured to solicit past-month symptoms, we asked participants to answer with respect to lifetime symptoms they experienced at baseline and past-year symptoms at each subsequent wave. In a similar sample of National Guard soldiers (14), past-year telephone diagnosis of PTSD using the PCL was found to have moderate sensitivity (.54) and high specificity (.92) and negative predictive value (.97) compared to the “gold standard” Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS)(15).

The PCL was administered to participants endorsing any of the traumatic experiences in the traumatic events questionnaire. Participants answered a questionnaire to assess potentially traumatic events, first outside the context of their most recent deployment, and then within the context of their most recent deployment. Non-deployment related traumatic events were assessed using a list compiled from the Life Events Checklist (16), and events from Breslau and colleagues (17); the deployment-related traumatic events were assessed using that same list, asked in reference to their most recent deployment, and also added items from the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (18). Participants were offered an opportunity to describe any other traumatic event that was not listed on the 2 scales. Lifetime traumatic events were asked about at the first wave, whereas subsequent waves asked exclusively about events occurring since the last interview. Any potentially traumatic events that was not related to a respondent's most recent deployment was captured in a single item on the Life Events Checklist that asked whether they had ever “Experienced combat or exposure to a war zone”. At the baseline interview, 95% of respondents endorsed ≥ 1 trauma and completed the PCL.

Because of the differences in previously reported diagnostic criteria for PTSD (1), we calculated a sensitive and specific criteria for symptoms. Among participants who experienced a traumatic event, participants were classified dichotomously as having PTSD or not having PTSD symptoms on the sensitive criteria based on DSM-IV criteria alone, whereas the specific criteria required DSM-IV symptoms and a score of 50 or more on the checklist (range: 17–85) (19). The survey asked respondents to choose their self-reported worst traumatic event and endorse “how much you were ever bothered by each of these problems in relation to this stressful experience.” Respondents had to endorse that a symptom bothered them “Moderately” or more for it to count as positive towards the diagnosis. To be classified as having PTSD symptoms according to DSM-IV, participants had to endorse ≥ 1 criterion B symptom, ≥ 3 criterion C symptoms, ≥ 2 criterion D symptoms (13). Criterion A2 was dropped based on the DSM-5 classification criteria statement and recent research in veteran populations indicating the criterion is not helpful for diagnosing PTSD (20, 21). In our sample the scale had an internal consistency reliability (Cronbach's Alpha) of 0.94.

Assessment of depression

The Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ) consists of 9 DSM-IV major depression symptoms (22). Participants endorsing any depression items rated the severity of that symptom from 1 (several days) to 3 (nearly every day). In our sample the scale had an internal consistency reliability of 0.92. We assessed a sensitive and specific criterion for depression symptoms. The sensitive criteria of depression symptoms required a sum of 10 or more on a scale from 0 to 27 points, whereas the specific criteria of depression symptoms used the DSM-IV criteria, such that respondents had to endorse ≥ 5 symptoms, plus anhedonia or depressed mood, more than half the days over the course of a two-week period in their lifetime at baseline and over the past-year in subsequent waves.

Assessment of covariates

From the baseline questionnaire, we obtained data on previously recognized sociodemographic and military correlates of mental health, including: age, race/ethnicity, education, gender, marital status, military rank (junior enlisted [E1-E3], junior NCO [E4-E6], senior NCO [E7-E9], officer [W1-5/O1-O10]), lifetime deployment, and past-year deployment. In accordance with the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) Directive 15 (23), race and ethnicity was self-reported using a self-identified two-question format for race and ethnicity, allowing for multiple race categories. These questions were reduced to a single 4 level summary variable (Non-Hispanic white, Non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, Other). Weighted distributions of sociodemographic and military characteristics were compared to the distributions in the overall Guard and Reserve population and found comparable with the target population (Table 1).

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and military characteristics of the Reserve and National Guard Study Sample and the target population of all comparable US Reserve and National Guard service membersa

| National Guard |

Reserves |

Total Sample |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Weighteda |

Populationb |

Weighteda |

Populationb |

Weighteda |

Populationb |

||||

| Characteristic | % | SE | % | % | SE | % | % | SE | % |

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 17–24 | 32.4 | 1.7 | 30.9 | 26.1 | 1.6 | 27.3 | 29.3 | 1.2 | 29.2 |

| 25–34 | 32.1 | 1.6 | 32.2 | 31.5 | 1.6 | 31.3 | 31.8 | 1.1 | 31.9 |

| 35+ | 35.5 | 1.6 | 36.9 | 42.4 | 1.6 | 41.4 | 38.9 | 1.1 | 38.9 |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 85.6 | 1.2 | 84.9 | 78.8 | 1.4 | 78.7 | 82.2 | 0.9 | 82.2 |

| Female | 14.4 | 1.2 | 15.1 | 21.3 | 1.4 | 21.3 | 17.8 | 0.9 | 17.8 |

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Never married | 40.2 | 1.7 | 45.1 | 37.7 | 1.7 | 43.3 | 39.0 | 1.2 | 44.2 |

| Married | 47.4 | 1.7 | 47.9 | 50.3 | 1.7 | 48.9 | 48.9 | 1.2 | 48.5 |

| Previously married | 12.3 | 1.1 | 7.0 | 12.0 | 1.1 | 7.6 | 12.2 | 0.8 | 7.3 |

| Branch | |||||||||

| Air National Guard | 17.8 | 0.4 | 23.4 | 9.0 | 0.2 | 12.8 | |||

| Army National Guard | 82.2 | 0.4 | 76.6 | 41.6 | 0.5 | 42.0 | |||

| Air Force Reserves | 17.1 | 0.5 | 17.6 | 8.4 | 0.3 | 8.0 | |||

| Army Reserves | 53.3 | 0.7 | 53.2 | 26.3 | 0.4 | 24.1 | |||

| Marine Reserve | 11.9 | 0.3 | 10.0 | 5.9 | 0.2 | 4.5 | |||

| Navy Reserve | 17.8 | 0.5 | 17.2 | 8.8 | 0.3 | 7.8 | |||

| Rank | |||||||||

| Junior Enlisted (E1-E3) | 14.9 | 1.3 | 20.2 | 14.1 | 1.3 | 20.1 | 14.5 | 0.9 | 20.1 |

| Non-Commissioned Officers (E4-E9) | 76.1 | 1.4 | 68.1 | 69.7 | 1.5 | 61.7 | 72.9 | 1.0 | 65.2 |

| Officer (W1-W5/O1-O6) | 9.0 | 0.7 | 11.8 | 16.3 | 1.0 | 18.2 | 12.6 | 0.6 | 14.7 |

Figures for the Reserve and National Guard Study are based on a weighted sample of 2,003. All values are from the baseline wave.

Selected Guard/Reserve Profile as of September 30, 2009 from Reserve Common Component Personnel Data System (RCCPDS). GED, General Education Development; E, Enlisted rank; W, Warrant officer rank; O, Commissioned officer rank.

Data analysis

We calculated persons at risk, new cases, and person-years at risk of developing each PTSD and depression at both the sensitive and the specific criteria. Persons at risk were calculated as the number of respondents who were disease-free (i.e., without lifetime prevalent disorder) at baseline. New cases were the number of respondents without a prevalent diagnosis at baseline that received a diagnosis of the examined disorder during follow-up. Person-years at risk of developing each disorder were calculated from the baseline survey date to either the date of disorder onset, loss to follow-up, or end of the study period. To calculate the recurrence rates, persons at risk were calculated as the number of respondents who had disease (i.e., with lifetime prevalent disorder) at baseline; recurrent cases were the number of respondents with a prevalent diagnosis at baseline that received a diagnosis of the examined disorder during follow-up; and person-years at risk of developing each disorder were calculated from the baseline survey date to either the date of disorder onset, loss to follow-up, or end of the study period.

All rates were calculated by dividing the total number of new cases for each category by the number of person-years at-risk of developing each disorder. Sociodemographic and military specific rates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were based on the Poisson distribution. All bivariate associations were estimated using weighted χ2tests (two-sided α level ≤ 0.05), and all analyses were conducted in SAS-callable SUDAAN.

Results

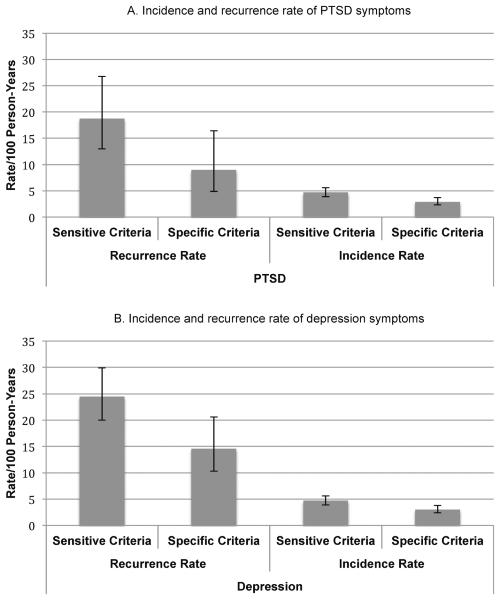

Figure 1 shows the overall incidence and recurrence rates for PTSD and depression symptoms by scoring method. The overall first incidence rate of PTSD for the sensitive and specific criteria was 4.7 (95%CI, 3.9-5.6) and 2.9 (95% CI, 2.3–3.7) per 100 person-years respectively, whereas the recurrence rate was 18.7 (95%CI, 13–26.8) and 9.0 (95% CI, 4.9–16.4) per 100-person years for respectively the sensitive and specific criteria. Likewise, the overall first incidence rate of depression for the sensitive and specific criteria was 4.7 (95% CI, 3.9-5.6) and 3.0 (95% CI, 2.4–3.7) per 100 person-years respectively, whereas the recurrence rate was 24.5 (95% CI, 20.0–29.9) and 14.6 (95% CI, 10.3–20.6) per 100-person years for respectively the sensitive and specific criteria.

Table 2 presents the sociodemographic- and military-specific PTSD incidence rates by scoring criterion. Men and NCOs had significantly higher (p<0.05) rates than comparison groups. Applying the more sensitive criteria, no sociodemographic or military characteristic was found to have statistically significant differences in incidence, albeit NCOs had a marginally higher incidence rate than respondents that were junior enlisted or officers. Incidence rates were substantially higher among respondents with past-year civilian trauma (6.5 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 5.2–8.1) than those without civilian trauma (2.9 per 100 person-years; 95% CI, 2.1–4.0). When applying the specific criteria, incidence rates were significantly different by sex, rank, baseline deployments, service branch, and civilian trauma.

Table 2.

Weighted incidence rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) per 100 person-years, by sensitive and specific criterion, US Reserve and National Guard service members, 2010–2013

| Incidence of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder at Follow-up |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive Criteriona | Specific Criterionb | |||||

|

|

||||||

| Risk Factor | Incidence per 100 person-years | 95% CI | p | Incidence per 100 person-years | 95% CI | p |

| Age (years) | .90 | .40 | ||||

| 18–24 | 4.8 | 3.0–7.5 | 1.9 | 0.8–4.3 | ||

| 25–34 | 4.4 | 3.2–6.1 | 2.9 | 1.9–4.4 | ||

| 35+ | 4.9 | 3.8–6.3 | 3.4 | 2.5–4.7 | ||

| Sex | .82 | .02 | ||||

| Male | 4.6 | 3.8–5.7 | 3.2 | 2.5–4.2 | ||

| Female | 4.9 | 3.2–7.4 | 1.4 | 0.7–2.8 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | .41 | .10 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | 4.3 | 3.4–5.3 | 2.4 | 1.8–3.3 | ||

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 6.4 | 4.0–10.2 | 4.6 | 2.6–8.2 | ||

| Hispanic | 5.5 | 3.3–9.1 | 4.3 | 2.4–7.6 | ||

| Other | 5.3 | 3.0–9.1 | 3.8 | 2.0–7.2 | ||

| Education | .22 | .26 | ||||

| < High school & GED | 4.2 | 1.0–16.6 | 7.9 | 2.1–29.1 | ||

| High school | 6.1 | 3.9–9.4 | 3.6 | 2.0–6.4 | ||

| Some college | 4.8 | 3.7–6.2 | 2.8 | 2.0–3.8 | ||

| College graduate + | 3.5 | 2.6–4.8 | 2.3 | 1.6–3.4 | ||

| Marital status | .32 | .10 | ||||

| Never married | 3.9 | 2.7–5.7 | 2.3 | 1.3–4.0 | ||

| Married | 4.9 | 3.8–6.2 | 2.9 | 2.1–4.0 | ||

| Previously married | 6.1 | 3.9–9.5 | 4.8 | 3.0–7.6 | ||

| Rank | .07 | .006 | ||||

| Junior enlisted (E1-E3) | 4.4 | 2.2–8.8 | 1.2 | 0.4–3.4 | ||

| Non-Commissioned Officers (E4-E9) | 5.1 | 4.1–6.2 | 3.4 | 2.6–4.4 | ||

| Officer (W1-W5/O1-O6) | 3.0 | 2.0–4.5 | 1.4 | 0.8–2.5 | ||

| Number of baseline deployments | .67 | .04 | ||||

| 0 | 3.9 | 2.5–5.9 | 1.4 | 0.7–2.5 | ||

| 1 | 4.8 | 3.4–6.7 | 3.9 | 2.6–5.9 | ||

| 2 | 5.1 | 3.7–7.0 | 3.5 | 2.4–5.0 | ||

| 3+ | 5.5 | 3.6–8.3 | 2.9 | 1.6–5.4 | ||

| Past-year deployment | .22 | .65 | ||||

| Yes | 7.2 | 4.6–11.2 | 3.0 | 1.4–6.3 | ||

| No | 5.3 | 4.4–6.5 | 3.6 | 2.8–4.6 | ||

| Past-year deployment trauma | .58 | .31 | ||||

| Yes | 5.3 | 3.2–8.7 | 2.0 | 0.9–4.4 | ||

| No | 4.6 | 3.7–5.6 | 3.1 | 2.4–4.0 | ||

| Past-year civilian trauma | .0001 | .0003 | ||||

| Yes | 6.5 | 5.2–8.1 | 4.2 | 3.1–5.6 | ||

| No | 2.9 | 2.1–4.0 | 1.6 | 1.0–2.5 | ||

| Component | .13 | .81 | ||||

| Reserve | 4.0 | 3.0–5.3 | 3.0 | 2.1–4.2 | ||

| National Guard | 5.3 | 4.2–6.8 | 2.8 | 2.0–4.0 | ||

| Branch | .24 | .004 | ||||

| Air Force Reserve | 2.7 | 1.3–5.6 | 1.1 | 0.3–3.5 | ||

| Army Reserve | 4.2 | 2.8–6.3 | 4.2 | 2.7–6.6 | ||

| Marine Reserve | 5.3 | 3.0–9.7 | 2.5 | 1.1–5.5 | ||

| Navy Reserve | 4.0 | 2.2–7.2 | 1.9 | 0.9–4.0 | ||

| Air National Guard | 3.4 | 1.9–6.1 | 0.4 | 0.1–1.4 | ||

| Army National Guard | 5.9 | 4.5–7.7 | 3.6 | 2.4–5.0 | ||

Sensitive Criterion (DSM): respondents endorsing at least 1 intrusion, 3 avoidance symptoms, and 2 hyperarousal symptoms at the moderate level on the PTSD checklist (PCL).

Specific Criterion (DSM+50): respondents meeting DSM criteria and total score of at least 50. PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder; GED, Graduate equivalence diploma; E, Enlisted rank; O, Commissioned officer rank; W, Warrant officer rank.

Table 3 shows that applying the specific criteria, marital status, rank, military branch, and civilian trauma were the four characteristics with significantly (p<0.05) different incidence rates for depression; incidence was higher among previously married, NCOs, Marine Reserves, and those with civilian trauma than comparison groups. Similar to the specific criteria, previously married (9.9 per 100 person-years) respondents had a significantly (p<0.05) higher incidence of depression compared to never married (3.6 per 100 person-years) and married (4.4 per 100 person-years) respondents. Depression incidence rates were significantly (p<0.05) different by education and rank, whereas rates were marginally different by sex (p=0.07) and branch (p=0.08).

Table 3.

Weighted incidence rates of depression per 100 person-years, by sensitive and specific criterion, US Reserve and National Guard service members, 2010–2013

| Incidence of Depression at Follow-up |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sensitive Criteriona |

Specific Criterionb |

|||||

| Risk Factor | Incidence per 100 person-years | 95% CI | p | Incidence per 100 person-years | 95% CI | p |

| Age (years) | .34 | .14 | ||||

| 18–24 | 3.3 | 1.9–5.7 | 2.6 | 1.5–4.7 | ||

| 25–34 | 5.2 | 3.9–7.0 | 3.9 | 2.8–5.4 | ||

| 35+ | 4.7 | 3.6–6.2 | 2.5 | 1.7–3.5 | ||

| Sex | .07 | .24 | ||||

| Male | 4.3 | 3.5–5.4 | 2.8 | 2.2–3.7 | ||

| Female | 6.3 | 4.4–9.1 | 3.9 | 2.5–6.1 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | .26 | .39 | ||||

| Non-Hispanic, White | 4.2 | 3.4–5.3 | 2.8 | 2.1–3.6 | ||

| Non-Hispanic, Black | 6.9 | 4.5–10.6 | 3.6 | 2.0–6.6 | ||

| Hispanic | 5.2 | 2.9–9.1 | 4.5 | 2.7–7.4 | ||

| Other | 4.7 | 2.1–10.4 | 2.9 | 1.2–7.0 | ||

| Education | .007 | .36 | ||||

| < High school & GED | 9.7 | 3.8–24.5 | 4.5 | 1.1–18.2 | ||

| High school | 5.5 | 3.6–8.6 | 3.2 | 1.8–5.5 | ||

| Some college | 5.2 | 4.1–6.7 | 3.4 | 2.5–4.6 | ||

| College graduate + | 2.9 | 2.0–4.0 | 2.2 | 1.5–3.3 | ||

| Marital status | .0002 | .04 | ||||

| Never married | 3.6 | 2.5–5.3 | 2.4 | 1.6–3.7 | ||

| Married | 4.4 | 3.4–5.6 | 2.9 | 2.2–4.0 | ||

| Previously married | 9.9 | 6.8–14.5 | 5.5 | 3.4–8.8 | ||

| Rank | .04 | .03 | ||||

| Junior enlisted (E1-E3) | 3.2 | 1.3–7.8 | 2.4 | 0.9–6.4 | ||

| Non-Commissioned Officers (E4-E9) | 5.2 | 4.2–6.4 | 3.4 | 2.7–4.3 | ||

| Officer (W1-W5/O1-O6) | 3.0 | 2.0–4.5 | 1.6 | 0.9–2.6 | ||

| Number of baseline deployments | .39 | .26 | ||||

| 0 | 4.9 | 3.4–6.9 | 3.0 | 1.9–4.6 | ||

| 1 | 3.6 | 2.5–5.2 | 2.4 | 1.6–3.6 | ||

| 2 | 5.3 | 3.8–7.5 | 4.1 | 2.8–6.0 | ||

| 3+ | 5.5 | 3.6–8.4 | 2.5 | 1.4–4.6 | ||

| Past-year deployment | .26 | .30 | ||||

| Yes | 7.0 | 4.7–10.6 | 2.7 | 1.4–5.2 | ||

| No | 5.4 | 4.4–6.6 | 3.9 | 3.0–4.9 | ||

| Past-year deployment trauma | .83 | .16 | ||||

| Yes | 4.9 | 3.0–8.0 | 1.8 | 0.8–4.0 | ||

| No | 4.6 | 3.8–5.7 | 3.3 | 2.6–4.1 | ||

| Past-year civilian trauma | .002 | .009 | ||||

| Yes | 6.1 | 4.8–7.7 | 3.9 | 2.9–5.2 | ||

| No | 3.3 | 2.5–4.5 | 2.2 | 1.5–3.0 | ||

| Component | .11 | .30 | ||||

| Reserve | 4.0 | 3.1–5.2 | 2.7 | 1.9–3.7 | ||

| National Guard | 5.4 | 4.2–6.9 | 3.4 | 2.5–4.6 | ||

| Branch | .08 | .01 | ||||

| Air Force Reserve | 2.1 | 1.0–4.2 | 0.7 | 0.2–1.8 | ||

| Army Reserve | 4.3 | 3.0–6.1 | 2.7 | 1.7–4.4 | ||

| Marine Reserve | 7.4 | 4.1–13.1 | 5.4 | 2.9–10.1 | ||

| Navy Reserve | 3.3 | 1.6–6.8 | 2.8 | 1.3–6.0 | ||

| Air National Guard | 5.1 | 3.0–8.8 | 2.2 | 1.0–4.8 | ||

| Army National Guard | 5.4 | 4.1–7.2 | 3.7 | 2.7–5.1 | ||

Sensitive Criterion: 10 or more on PHQ9 screener

Specific Criterion: PHQ9 DSM-requires that one or both of depressed mood or loss of interest be endorsed at the “most days” level and that a total of 5 items be scored at this level. One exception is that a suicidal ideation item can be counted towards the required 5 symptoms even if it is only endorsed at the “several days” level. PTSD, Posttraumatic stress disorder; PHQ, Patient Health Questionnaire; GED, Graduate Equivalence Diploma; E, Enlisted rank; O, Commissioned officer rank; W, Warrant officer rank.

Discussion

In this study of US Reserve and National Guard, incidence rates were 4.7 per 100 person-years for both PTSD and depression symptoms using the sensitive criteria and about 2.9 per 100 person-years using the specific criteria. Recurrence rates for both PTSD and depression were more than 4 times as high as incidence rates. There was heterogeneity in risk of PTSD and depression symptoms in terms of both sociodemographic and military characteristics. Notably, in respondents with past-year civilian trauma, the incidence rates of both PTSD and depression symptoms were about twice as high as those without civilian trauma, whereas respondents with past-year deployment trauma had similar incidence rates for both disorders. In addition, incidence rates of both PTSD and depression were higher in NCOs, compared to junior enlisted and officers, and previously married respondents had a higher risk of depression symptoms than single and married respondents, but PTSD risk did not differ by marital status.

Our study yielded incidence rates comparable to new-onset rates presented by others in representative military populations, but lower than rates in post-deployment samples. In our study the incidence rate of first-ever depression was 3.0 per 100 person-years, or 3.0% of reservists per year, using the sensitive criteria, whereas the Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) employed the same diagnostic criteria in Reserve and National Guard and documented new-onset depression in 4.0% of nondeployed reservists, 2.2% of those deployed without combat exposure, and 6.5% of those deployed with combat exposure (24). Notably, incidence rate of depression in nondeployed respondents were comparable in both studies, about 4.0% of respondents. In addition, our incidence rate in past-year deployed respondents (7.0%) was similar to deployed respondents with combat exposures in the MCS study (6.5%). To some extent, previous studies that report higher new-onset rates (10, 25) is explained by population differences, specifically studies that have investigated the effect of deployment on psychopathology have restricted sampling to recently deployed or deploying service members, which is likely to overestimate the risk of PTSD and depression in the general reservists population, which includes both deployed and non-deployed service members. Moreover, the selection of respondents based on deployment status removes the comparison population from the study, as such the effect of deployment itself on PTSD and depression risk cannot be investigated. Thus, our study that sampled the general reservists population is likely to be better equipped to assess deployment as a risk factor for PTSD and depression than previous studies that excluded a comparison group, particularly non-deployed personnel.

That we found a higher incidence rate in respondents with past-year civilian trauma, but not deployment, is explained by previous studies excluding comparison groups, particularly non-deployed personnel. Several studies (2, 4, 26) have documented an increase in PTSD and depression symptoms among deployed military personnel, but these studies exclude a comparison population (i.e., non-deployed personnel), which prevents estimation of the effect of deployment itself on PTSD and depression. Studies have documented that specific combat experiences, not deployment in general, has an adverse effect on mental health (24, 27). Moreover, PTSD and depression risk is the consequence of pre-deployment experiences and combat exposures, such that those with early life sexual and violent assault are documented to be at an increased risk of post-deployment PTSD symptoms compared to those without prior assaults (28). Insofar as recent military personnel are more likely to experience early life traumatic experiences than civilians (8), the study of the consequences of military trauma should focus on predeterminants of those consequences over the life course (29).

Two other findings merit discussion: PTSD and depression incidence were higher among NCOs and depression incidence was higher among previously married respondents. First, NCOs, similar to officers, generally have a substantial responsibility for the well-being of junior enlisted service members (31), yet often lack the influence over policy and resources available to officers. Under the job demands-resources model (32), personnel who have high demands and minimal control in their work environment are hypothesized to be at greater risk of developing psychopathology. As an alternative explanation for NCOs having a higher risk of PTSD compared to other groups, NCOs might have had more prior deployment-related traumatic events, which served to create a cumulative effect. This explanation can be supported by our observation of a higher rate of PTSD (sensitive criteria) among persons with more baseline deployments. Second, in previously married respondents compared with single or married respondents, the incidence of depression symptoms was higher, but rates of PTSD were not different by marital status. Because interpersonal problems can cause marital separation and divorce (35) and decades of research have shown that relationship problems predict depression (36), the higher risk for depression in previously married respondents is anticipated. Moreover, marital status may be a predictor for depression and consequence of PTSD. Recent studies have proposed a mediation model whereby the association between military trauma and marital problems is mediated by screening positive for PTSD (37–39), whereas other studies suggest an synergistic effect among PTSD, alcohol misuse, intimate partner violence, and relationship problems among combat veterans (38, 40, 41). The relationship among marital problems, PTSD, and depression remains unclear, but trauma-exposed populations can benefit from interventions that aim to maintain healthy relationships following trauma exposure.

Three central limitations of our study should be noted when interpreting results. First, lay interviewers may be less consistent and systematic than study-trained clinician interviewers. To counter this limitation, we employed computer assisted telephone interview (CATI) technology that is shown to improve data quality (42), reduce missing responses (43), and increase participant response rates over paper and pencil mail surveys (44). Moreover, we employed highly reliable measures of PTSD and depression that have been recommended to assess symptomatology in military samples (1). Second, since the DSM-IV PTSD diagnosis required a traumatic event that represented threat to the respondent's life or integrity, symptoms were assessed specific to a single event; this could have led to an underestimation of PTSD incidence. Third, our measure of PTSD was modified to collect past year, compared to past-month, symptoms; however, these methods have proved specific with moderate sensitivity (14), which suggests that our sensitive PTSD criteria might have underestimated the true incidence. Lastly, the low incidence of PTSD and depression could have resulted in nonsignificant statistical tests when heterogeneity of incidence rates existed. Furthermore, the available sample size and numbers of incident cases did not allow an examination of multivariable models of the independence of predictive relationship from confounders. We acknowledge this is an important next step for future studies.

These findings represent the first to assess incidence rates for first ever PTSD and depression in any representative military cohort, specifically a representative US Reserve and National Guard cohort. Our findings that civilian trauma, but not past-year military deployment, is associated with an increased risk of PTSD and depression incidence suggest that military psychopathology could be as much derived from other, non-military, traumatic experiences as it is a function of deployment related trauma. Thus, future studies that compare psychopathology risk following different types of trauma are necessary in this population. Moreover, cross-component epidemiological studies of psychopathology are needed to examine these rates and risk factors among all forces (i.e., both the active and the reserve component forces).

Fig. 2.

Incidence and recurrence rates and 95% confidence intervals of (a) Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and (b) Depression per 100 person-years, by sensitive and specific criterion, US Reserve and National Guard service members, 2010–2013

a Sensitive Criterion: 10 or more on the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) depression screener.

b Specific Criterion: PHQ9 DSM-requires that one or both of depressed mood or loss of interest be endorsed at the “most days” level and that a total of 5 items be scored at this level. One exception is that a suicidal ideation item can be counted towards the required 5 symptoms even if it is only endorsed at the “several days” level.

c Sensitive Criterion (DSM): respondents endorsing at least 1 intrusion, 3 avoidance symptoms, and 2 hyperarousal symptoms at the moderate level on the PTSD checklist (PCL).

d Specific Criterion (DSM+50): respondents meeting DSM criteria and total score of at least 50 on the PCL.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) (S.G., grant number R01MH082729), by the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA) (D.S.F., grant number T32DA031099), and by the Department of Defense (S.G., R.J.U., grant numbers W81XWH-08-02-0204, W81XWH-08-2-0650). Funding sources had no role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Cohen GH, Fink DS, Sampson L, Galea S. Mental Health Among Reserve Component Military Service Members and Veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015 Jan 16;37(1) doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxu007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas JL, Wilk JE, Riviere LA, McGurk D, Castro CA, Hoge CW. Prevalence of mental health problems and functional impairment among active component and National Guard soldiers 3 and 12 months following combat in Iraq. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010 Jun;67(6):614–23. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iowa Persian Gulf Study Group Self-reported illness and health status among Gulf War veterans. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1997;277(3):238–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Milliken CS, Auchterlonie JL, Hoge CW. Longitudinal assessment of mental health problems among active and reserve component soldiers returning from the Iraq war. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 2007 Nov 14;298(18):2141–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.18.2141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Riddle JR, Smith TC, Smith B, Corbeil TE, Engel CC, Wells TS, et al. Millennium Cohort: the 2001–2003 baseline prevalence of mental disorders in the U.S. military. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007 Feb;60(2):192–201. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shea MT, Vujanovic AA, Mansfield AK, Sevin E, Liu F. Posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms and functional impairment among OEF and OIF National Guard and Reserve veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(1):100–7. doi: 10.1002/jts.20497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kehle SM, Reddy MK, Ferrier-Auerbach AG, Erbes CR, Arbisi PA, Polusny MA. Psychiatric diagnoses, comorbidity, and functioning in National Guard troops deployed to Iraq. J Psychiatr Res. 2011 Jan;45(1):126–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kessler RC, Heeringa SG, Stein MB, Colpe LJ, Fullerton CS, Hwang I, et al. Thirty-Day Prevalence of DSM-IV Mental Disorders Among Nondeployed Soldiers in the US Army: Results from the Army Study to Assess Risk and Resilience in Servicemembers (Army STARRS) JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 Mar 5; doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenen KC, Stellman JM, Stellman SD, Sommer JF., Jr Risk factors for course of posttraumatic stress disorder among Vietnam veterans: a 14-year follow-up of American Legionnaires. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2003;71(6):980. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.71.6.980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Marshall BD, Prescott MR, Liberzon I, Tamburrino MB, Calabrese JR, Galea S. Coincident posttraumatic stress disorder and depression predict alcohol abuse during and after deployment among Army National Guard soldiers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012 Aug 1;124(3):193–9. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Research AAfPO . Standard Definitions: Final Dispositions of Case Codes and Outcome Rates for Surveys. American Association for Public Opinion Research; Lenexa, KS: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Russell DW, Cohen GH, Gifford R, Fullerton CS, Ursano RJ, Galea S. Mental health among a nationally representative sample of United States Military Reserve Component Personnel. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2014:1–13. doi: 10.1007/s00127-014-0981-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Blanchard EB, Jones-Alexander J, Buckley TC, Forneris CA. Psychometric properties of the PTSD Checklist (PCL) Behav Res Ther. 1996;34(8):669–73. doi: 10.1016/0005-7967(96)00033-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Prescott MR, Tamburrino M, Calabrese JR, Liberzon I, Slembarski R, Shirley E, et al. Validation of lay-administered mental health assessments in a large Army National Guard cohort. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2014 Mar;23(1):109–19. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Blake D, Weathers FW, Nagy L, Kaloupek D, Klauminzer G, Charney D, et al. Instruction Manual: Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale. National Center for Postraumatic Stress Disorder, Behavioral Science Division; Boston, MA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray MJ, Litz BT, Hsu JL, Lombardo TW. Psychometric properties of the life events checklist. Assessment. 2004;11(4):330–41. doi: 10.1177/1073191104269954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breslau N, Kessler RC, Chilcoat HD, Schultz LR, Davis GC, Andreski P. Trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder in the community: the 1996 Detroit Area Survey of Trauma. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998 Jul;55(7):626–32. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.7.626. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.King LA, King DW, Vogt DS, Knight J, Samper RE. Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory: a collection of measures for studying deployment-related experiences of military personnel and veterans. Mil Psychol. 2006;18(2):89. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brewin CR. Systematic review of screening instruments for adults at risk of PTSD. J Trauma Stress. 2005 Feb;18(1):53–62. doi: 10.1002/jts.20007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adler AB, Wright KM, Bliese PD, Eckford R, Hoge CW. A2 diagnostic criterion for combat-related posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2008;21(3):301–8. doi: 10.1002/jts.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Osei-Bonsu PE, Spiro A, Schultz MR, Ryabchenko KA, Smith E, Herz L, et al. Is DSM-IV criterion A2 associated with PTSD diagnosis and symptom severity? J Trauma Stress. 2012;25(4):368–75. doi: 10.1002/jts.21720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kroenke K, Spitzer RL, Williams JB. The PHQ-9: validity of a brief depression severity measure. J Gen Intern Med. 2001 Sep;16(9):606–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.016009606.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Office of Management and Budget Revisions to the Standards for the Classification of Federal Data on Race and Ethnicity. 1997 Contract No.: Statistical Policy Directive No. 15.

- 24.Smith TC, Ryan MA, Wingard DL, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, Kritz-Silverstein D. New onset and persistent symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder self reported after deployment and combat exposures: prospective population based US military cohort study. BMJ. 2008 Feb 16;336(7640):366–71. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39430.638241.AE. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Polusny MA, Erbes CR, Murdoch M, Arbisi PA, Thuras P, Rath MB. Prospective risk factors for new-onset post-traumatic stress disorder in National Guard soldiers deployed to Iraq. Psychol Med. 2011 Apr;41(4):687–98. doi: 10.1017/S0033291710002047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hoge CW, Castro CA, Messer SC, McGurk D, Cotting DI, Koffman RL. Combat duty in Iraq and Afghanistan, mental health problems and barriers to care. N Engl J Med. 2004;351(1):13–22. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wells TS, LeardMann CA, Fortuna SO, Smith B, Smith TC, Ryan MA, et al. A prospective study of depression following combat deployment in support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Am J Public Health. 2010 Jan;100(1):90–9. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.155432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Smith TC, Wingard DL, Ryan MA, Kritz-Silverstein D, Slymen DJ, Sallis JF, et al. Prior assault and posttraumatic stress disorder after combat deployment. Epidemiology. 2008;19(3):505–12. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31816a9dff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fink DS, Galea S. Life Course Epidemiology of Trauma and Related Psychopathology in Civilian Populations. Current Psychiatry Reports. 2015;17(5):566. doi: 10.1007/s11920-015-0566-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blosnich JR, Dichter ME, Cerulli C, Batten SV, Bossarte RM. Disparities in Adverse Childhood Experiences Among Individuals With a History of Military Service. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 Sep 1;71(9):1041–8. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dolan CA, Ender MG. The coping paradox: Work, stress, and coping in the US Army. Mil Psychol. 2008;20(3):151–69. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bakker AB, Demerouti E. The job demands-resources model: State of the art. Journal of managerial psychology. 2007;22(3):309–28. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Muntaner C, Borrell C, Benach J, Pasarín MI, Fernandez E. The associations of social class and social stratification with patterns of general and mental health in a Spanish population. Int J Epidemiol. 2003;32(6):950–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyg170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muntaner C, Eaton W, Diala C, Kessler R, Sorlie P. Social class, assets, organizational control and the prevalence of common groups of psychiatric disorders. Soc Sci Med. 1998;47(12):2043–53. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(98)00309-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Karney BR, Bradbury TN. The longitudinal course of marital quality and stability: A review of theory, methods, and research. Psychol Bull. 1995;118(1):3. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin N, Dean A, Ensel WM. Social support, life events, and depression. Academic Press; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Allen ES, Rhoades GK, Stanley SM, Markman HJ. Hitting home: relationships between recent deployment, posttraumatic stress symptoms, and marital functioning for Army couples. J Fam Psychol. 2010;24(3):280. doi: 10.1037/a0019405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meis LA, Erbes CR, Polusny MA, Compton JS. Intimate relationships among returning soldiers: The mediating and moderating roles of negative emotionality, PTSD symptoms, and alcohol problems. J Trauma Stress. 2010;23(5):564–72. doi: 10.1002/jts.20560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Galovski T, Lyons JA. Psychological sequelae of combat violence: A review of the impact of PTSD on the veteran's family and possible interventions. Aggression and Violent Behavior. 2004;9(5):477–501. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Savarese VW, Suvak MK, King LA, King DW. Relationships among alcohol use, hyperarousal, and marital abuse and violence in Vietnam veterans. J Trauma Stress. 2001;14(4):717–32. doi: 10.1023/A:1013038021175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kessler RC, Sonnega A, Bromet E, Hughes M, Nelson CB. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the National Comorbidity Survey. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1995 Dec;52(12):1048–60. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1995.03950240066012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gwaltney CJ, Shields AL, Shiffman S. Equivalence of electronic and paper-and-pencil administration of patient-reported outcome measures: a meta-analytic review. Value Health. 2008;11(2):322–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2007.00231.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Feveile H, Olsen O, Hogh A. A randomized trial of mailed questionnaires versus telephone interviews: response patterns in a survey. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2007;7(1):27. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-7-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fowler FJ, Jr, Gallagher PM, Stringfellow VL, Zaslavsky AM, Thompson JW, Cleary PD. Using telephone interviews to reduce nonresponse bias to mail surveys of health plan members. Med Care. 2002;40(3):190–200. doi: 10.1097/00005650-200203000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]