Abstract

How a large number of cytokines differentially signal through a small number of signal transduction pathways is not well resolved. This is particularly true for IL-6 and IL-10, which act primarily through STAT3 yet induce dissimilar transcriptional programs leading alternatively to pro- and anti-inflammatory effects. Kinetic differences in signaling, sustained to IL-10 and transient to IL-6, are critical to this in macrophages. T cells are also key targets of IL-6 and IL-10, yet how differential signaling here leads to divergent cellular fates is unclear. We show that, unlike for macrophages, signal duration cannot explain the distinct effects of these cytokines in T cells. Rather, naïve, activated, activated-rested, and memory CD4+ T cells differentially express IL-6 and IL-10 receptors in an activation state-dependent manner, and this impacts downstream cytokine effects. We show a dominant role for STAT3 in IL-6-mediated Th17 subset maturation. IL-10 cannot support Th17 differentiation due to insufficient cytokine receptivity rather than signal quality. Enforced expression of IL-10Rα on naïve T cells permits an IL-10 generated STAT3 signal equivalent to that of IL-6 and equally capable of promoting Th17 formation. Similarly, naïve T cell IL-10Rα expression also allows IL-10 to mimic the effects of IL-6 on both Th1/Th2 skewing and Tfh cell differentiation. Our results demonstrate a key role for the regulation of receptor expression rather than signal quality or duration in differentiating the functional outcomes of IL-6 and IL-10 signaling, and identify distinct signaling properties of these cytokines in T cells compared with myeloid cells.

INTRODUCTION

IL-10 is a predominantly anti-inflammatory cytokine that inhibits antigen presentation and can modulate T cell responses (1–4). As a single example, pro-inflammatory Th17 cells present during intestinal inflammation express high levels of IL-10Rα and are suppressed by IL-10 producing regulatory T cells (5). IL-10 signals through a heterodimeric receptor that is a member of the IFN receptor superfamily (6, 7). IL-10Rβ is broadly expressed and shared by several cytokines. IL-10Rα expression is restricted and confers IL-10 specificity (7, 8). Although lymphocytes are responsive to IL-10, our understanding of IL-10 signaling is largely derived from studies in primary macrophages and cell lines. STAT3 is the key downstream mediator in these cells, and is phosphorylated by receptor-bound JAK1 and TYK2 (9–11). IL-10 also has the potential to activate both STAT1 and STAT5 (10–12).

Like IL-10, IL-6 signaling is primarily transduced through STAT3 (13). However, unlike IL-10, IL-6 is a key mediator of many pro-inflammatory responses. Notably, IL-6 in concert with TGFβ and TCR signaling is a primary driver of naïve CD4+ T cell differentiation into inflammatory Th17 cells. IL-6 simultaneously suppresses TGF-β-mediated Foxp3+ regulatory T cell (Treg) formation (14, 15), while IL-10, conversely, sustains Tregs. The IL-6 specific receptor, IL-6Rα, lacks intracellular signaling domains but forms a signaling complex with the shared common signaling receptor gp130 (13). While gp130 is ubiquitously expressed, IL-6Rα expression is restricted primarily to leukocytes and hepatocytes. Receptor engagement triggers activation of JAK1, JAK2 and Tyk2, which phosphorylate and activate STAT3 (16).

JAK/STAT signaling is common to over 50 cytokines and uses only a few STAT family members. Indeed, a central question in cytokine biology is how relatively few STAT proteins can induce the diverse cellular programs initiated by different cytokines. IL-6 and IL-10 represent two cytokines that share STAT3 as a key signaling mediator, and yet promote divergent biological outcomes. A leading hypothesis for the distinct effects of IL-6 and IL-10 is that they are differentially regulated by SOCS3. SOCS3 binds to the SHP2 site on the shared receptor gp130, blocking the IL-6-induced STAT3 response (17–20). Studies in primary human macrophages indicate that while SOCS3 is induced by both IL-6 and IL-10, it is not a substantive feedback inhibitor of the IL-10 STAT3 signal. (21, 22). STAT3 activation in macrophages is better sustained in response to IL-10 than IL-6 due to lack of negative regulation by SOCS3, and this prolonged signal is necessary to generate an anti-inflammatory cellular program (22).

Although differences in IL-6 and IL-10 induced STAT3 signaling have been studied extensively in macrophages and macrophage cell lines, little is known about these signaling events in T cells. To study this, we first examined IL-6 and IL-10 receptor expression and found that receptor levels fluctuate dramatically with T cell activation state. Further, the level of STAT3 signaling in CD4+ T cell subsets by IL-6 and IL-10 is dependent on the level of cognate receptor. Analysis of the Th17 differentiation program demonstrates that IL-10’s inability to induce Th17 cells does not result from qualitative differences in IL-6 and IL-10 signaling, but rather from diminished cytokine receptivity. Enforced expression of IL-10Rα on naïve CD4+ T cells, which are normally minimally responsive to IL-10, enables IL-10 to fully replace IL-6 in promoting Th17 differentiation. Furthermore, this effect is not specific to Th17 differentiation, as IL-10Rα expression on naïve T cells also allows IL-10 to replicate effects of IL-6 on Th1/Th2 skewing and Tfh differentiation. These findings indicate that in T cells at various states of activation, differential effects of IL-6 and IL-10 can result from distinct receptor expression patterns, rather than fundamental differences in signal quality.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice

Foxp3 YFP cre (23) and C57BL/6 mice were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. All animal experiments were performed in American Association for the Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care-accredited, specific-pathogen-free facilities in the St. Jude Animal Resource Center following national, state and institutional guidelines. Animal protocols were approved by the St Jude Animal Care and Use Committee.

Antibodies and cytokines

Antibodies for surface staining and cell sorting against mouse CD4 (clone RM4–5), CD62L (clone MEL-14) and CD44 (clone IM7) were all obtained from ebioscience. Rat anti-mouse antibodies against IL-6Rα CD126 (clone D7715A7), IL-10Rα CD210 (clone 1B1.3a), CCR6 (clone G034E3) and rat IgG1 (clone RTK2071) and IgG2b (clone RTK4530) isotype controls were obtained from Biolegend. Polyclonal rabbit antibodies against mouse pSTAT1 and mouse STAT1, monoclonal rabbit antibody against pSTAT3 (Y705) (clone D3A7), monoclonal mouse antibody against mouse STAT3 (clone 14H6), anti-rabbit HRP and anti-mouse HRP secondary antibodies, and anti-Histone H3 antibody were all obtained from Cell Signaling. Antibodies for intracellular staining of IL-17A (clone 17B7), IL-17F (clone 18F10), IL-22 (clone 1H8PWSR), IFNγ (clone XMG1.2), IL-10 (clone JES5-16E3), RORγt (clone B2D), and Foxp3 (clone FJK-16S) were all obtained from ebioscience. IL-23R and CCR6Low endotoxin, azide-free neutralizing anti-mouse IL-4 (clone 11B11) and anti-mouse IFN-γ (XMG1.2) were obtained from Biolegend. Anti-IL-23R antibody (clone O78-1208) was obtained from BD Pharmingen. All cytokines were obtained from PeproTech.

T cell isolation and activation

Spleens and lymph nodes of Foxp3 YFP cre mice were harvested and stained for flow cytometric sorting of naïve T cells (CD4+ Foxp3-YFP− CD62Lhi CD44lo) and memory T cells (CD4+ Foxp3-YFP− CD62Llo CD44hi). To generate activated T cells, naïve T cells were cultured with plate bound anti-CD3 (2 µg/ml) and soluble anti-CD28 (2 µg/ml) for 3 days in complete Click’s medium (Gibco). To generate activated-rested cells, naïve T cells were activated for 2 days as above and then rested and expanded in 10x volume of media plus 50 U/ml rIL-2 for 5 days.

IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα receptor staining

CD4+ T cells (directly ex-vivo or activated as described above) were resuspended in FACS buffer (PBS + 2% FBS), blocked with anti-Fc receptor, washed, and stained with the indicated antibodies or isotype controls for 60 minutes on ice. Cells were washed, resuspended in FACS buffer, and analyzed on a LSR Fortessa (BD Biosciences).

Immunoblotting

CD4+ T cells (naïve and memory cells directly ex-vivo or cells activated as described above) were incubated in serum free medium at 37°C for 2 hours, then stimulated for the indicated amount of time with 25 ng/ml IL-6 or 50 ng/ml IL-10 in serum free medium at 37°C. Cytokine concentrations were selected based on dosing experiments identifying minimal concentrations yielding optimal responses. Cells were harvested, centrifuged and immediately lysed in whole cell lysis buffer (20mM Tris-HCL pH7.8, 50mM EDTA, 1% NP-40, 1% Tween-20) supplemented with HALT protease and phosphatase inhibitor cocktail (Thermo). Denatured samples were run on SDS-PAGE and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. Membranes were blocked for 1 hour at room temperature in 4% non-fat dried milk, and then incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Membranes were washed in TBS + 0.5% Tween-20, incubated with anti-rabbit-HRP or anti-mouse-HRP conjugated secondary antibody for 1 hour at room temperature, and washed again. Chemiluminescent substrate (Pierce SuperSignal) was added to membranes and films were exposed and developed. For pSTAT blots, phospho-proteins were detected first. Membranes were then stripped (Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer, Thermo) and re-probed for total STAT protein.

Real Time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from naïve, memory, or activated T cells using Trizol reagent (Ambion), and cDNA was synthesized using the high-capacity reverse transcriptase kit (Applied Biosystems). Quantitative PCR was performed with SOCS3 and GAPDH primers using SYBR green select master mix (Applied Biosystems). Samples were assayed in triplicate using the 7900HT Fast qPCR system (Applied Biosystems) and SOCS3 expression levels were normalized to GAPDH. Relative mRNA expression was determined using SDS software (Applied Biosystems) and normalizing to an unstimulated control. Primer sequences were: SOCS3 forward – 5’ CGGAGATTTCGCTTCGGGAC 3’; SOCS3 reverse – 5’ AACTTGCTGTGGGTGACCATGG 3’; GAPDH forward – 5’ AGGTCGGTGTGAACGGATTTG 3’; GAPDH reverse – 5’ TGTAGACCATGTAGTTGAGGTCA 3’.

In-vitro Th17 differentiation

Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated as described above. Cells were incubated for 5 days in a flat bottom 96 well plate under Th17 conditions as previously described (24). Briefly, plates were pre-coated with 10 µg/ml anti-CD3 and 2 µg/ml anti-CD28. For “Th17 IL-6” conditions, cells were incubated at a concentration of 1x104 cells per well in 200 µl total volume with 25 ng/ml IL-6, 5 ng/ml TGF-β, 10 µg/ml anti-IL-4 and 10 µg/ml anti-IFNγ. For “Th-17 IL-10” conditions, the same conditions as above were used, except 50 ng/ml IL-10 was added instead of IL-6. For “Th17 IL-6 + IL10” conditions, both IL-6 and IL-10 were added to the cultures. For “Th0” conditions, cells were added to wells with plate bound anti-CD3/anti-CD28 with no added cytokines or neutralizing antibodies.

Intracellular staining

Cells were washed and restimulated with cytokine stimulation cocktail containing PMA, ionomycin and brefeldin A (Cell Stimulation Cocktail, ebioscience) for 5 hours at 37°C. Cells were washed and stained for indicated cytokines or transcription factors using Foxp3/transcription factor staining buffer set according to instructions (ebioscience).

Retrogenic mice

MSCV-GFP vector and MSCV-IL-10Rα-GFP retrovirus, in which the GFP is linked through an IRES to generate a polycistronic construct, were used to generated GPE86 viral producer cells lines, and viral supernatants used to transduce hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) from B6 mice as previously described (25, 26). Transduced cells were injected into lethally irradiated B6 recipient mice retro-orbitally. Mice were bled at 4 weeks to verify reconstitution of transduced (GFP+) cells and used for experiments 8 weeks after bone marrow transfer.

Adoptive transfers and in-vivo Th17 conversion

Sorted CD4+ CD45RBhi GFP+ cells from IL-10Rα or vector-control retrogenic mice were transferred i.v. into Rag1−/− mice (5×105 cells/mouse). Spleen, mesenteric lymph node (MLN), and colon were isolated from recipient mice at 8 weeks post-transfer. Lamina propria cells were isolated from colons as previously described (27). Samples were restimulated with cytokine stimulation cocktail for 5 hours, stained with antibodies against CD4 and IL-17A, and analyzed by flow cytometry.

Th1 and Th2 differentiation

Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated as described above. Cells were incubated with plate-abound anti-CD3 and soluble anti-CD28. For Th1 differentiation, cultures included 10 ng/ml IL-12. For Th2 differentiation, cultures included 10 ng/ml IL-4. Where indicated, IL-6, IL-10, or both were also added. Cells were cultured for 5 days, restimulated, and stained for IFNγ and IL-4 as described above.

Tfh differentiation

Naïve CD4+ T cells were isolated as described above. Cells were incubated with irradiated splenocytes from TCRβ−/− mice at a 5:1 APC to T cell ratio, anti-CD3, 10 µg/ml anti-IL-4, 10 µg/ml anti-IFNγ. Cytokines were added as indicated at the following concentrations: 100 ng/ml IL-6; 50 ng/ml IL-21; 50 ng/ml IL-10.

Statistical Analysis

Mean and standard deviation were calculated with Graphpad PRISM software. Significance between two groups was calculated by two-tailed unpaired t-test. When >2 groups were simultaneously compared, significance was determined by ANOVA using a Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons. A p ≤ 0.05 was considered significant.

RESULTS

IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα expression in primary T cell populations

To establish IL-6 and IL-10 signaling capacity in primary T cells, we first analyzed IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα expression in different cell populations. IL-6Rα was well expressed in naïve T cells (CD4+ Foxp3− CD62Lhi CD44lo; Fig. 1A, B). This dropped significantly with activation, reaching a minimum after 2 days. IL-10Rα showed reciprocal expression kinetics. Expression was undetectable on naïve T cells, but increased markedly after activation. Increases began 2 days post-stimulation, when IL-6Rα expression was already low. The decline in IL-6Rα rebounded after activated T cells were rested, whereas the increased IL-10Rα expression was maintained. Memory T cells (CD4+ Foxp3− CD62Llo CD44hi) likewise showed moderate to high level expression of both IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα (Fig. 1A). Thus IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα expression differs among primary T cell sub-populations and is highly dependent on activation state.

Figure 1. IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα expression on T cell populations.

(A) Histograms - naïve, activated, activated-rested, and memory T cells stained with IL-6Rα (left) or IL-10Rα (right) and corresponding isotype control antibodies (shaded histograms). Bar graphs - plotted MFI values of isotype staining (filled bars) or receptor staining (open bars) for indicated cell populations from 3 individual mice stained in triplicate. Results are representative of 3 experiments. ** p≤ 0.01; **** p≤ 0.0001. (B) Sorted naïve T cells were activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for indicated number of days and IL-6Rα or IL-10Rα expression was assessed by flow cytometry. Results were normalized to the maximal MFI value for each receptor.

STAT3 activation by IL-6 and IL-10 in primary T cell populations

To further characterize the differential impact of IL-6 and IL-10 on T cell populations, we compared cytokine-induced STAT3 phosphorylation in purified naïve, activated, activated-rested, and memory T cell populations (Fig. 2A). Minimal doses of IL-6 and IL-10 capable of inducing maximal pSTAT3 for each cytokine (data not shown) were used as stimuli. Phosphorylation of STAT3 (Y705) induced by IL-6 was greatest in naïve T cells. After T cell activation, low levels of pSTAT3 were apparent in the absence of exogenous cytokine, likely reflecting signaling due to endogenously produced cytokine. However, signal magnitude in response to IL-6 was decreased by 75% compared with naïve T cells.

Figure 2. STAT3 signaling in T cells stimulated with IL-6 or IL-10.

(A) Naïve, activated, activated-rested or memory T cells were stimulated with IL-6 or IL-10 as indicated for 20 minutes and pSTAT3 (Y705) and total STAT3 levels were assessed by Western blot. Bar graph represents quantified data pooled from at least 2 independent experiments and normalized to percent of maximal pSTAT3 signal for naïve T cells stimulated with IL-6. (B) Naïve sorted T cells were isolated and activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 for the indicated number of days. Cells were then stimulated with IL-6 or IL-10 as indicated for 20 minutes and pSTAT3 (Y705) and total STAT3 levels were assessed by Western blot. Bar graph represents pooled data from at least 2 independent experiments, normalized to maximal pSTAT3 signal for either IL-6 or IL-10 independently.

In contrast with IL-6, IL-10 induced little pSTAT3 in naïve T cells. After activation, pSTAT3 was strongly induced, though the maximum signal was only 50% of that induced by IL-6 in naïve T cells. Although we were unable to detect IL-10Rα on the surface of naïve T cells and IL-6Rα on the surface of 3-day activated T cells, low levels of pSTAT3 were observed with these respective cytokines and populations, likely reflecting limitations in detecting low receptor levels by flow cytometry. Nevertheless, these results indicate an overall correspondence between IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα surface expression and signal magnitude.

Consistent with this, the relatively strong expression of both IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα on memory T cells was associated with the induction of high and nearly equivalent levels of pSTAT3 by both IL-6 and IL-10 (Fig. 2A). However, in activated-rested T cells where receptor expression is comparable to that of memory T cells, both IL-6 and IL-10 induced only very low levels of pSTAT3. Therefore in this population, cytokine sensitivity appears to be downregulated by mechanisms independent of receptor expression. We repeated the experiment above using Histone-H3 as a loading control, and saw equivalent relative levels of pSTAT3 in each cell type when normalized either to total STAT3 or Histone H3 (Supplemental Figure 1).

We next examined STAT3 responses temporally after TCR stimulation (Fig. 2B). STAT3 phosphorylation in response to IL-6 increased after one day of activation, despite a decline in receptor levels by 75% (Fig. 1B). However, this subsequently decreased and was undetectable by day 4. IL-10 demonstrated inverted kinetics, with minimal detectable STAT3 phosphorylation until day 3 after stimulation. Thus IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα expression and capacity to phosphorylate STAT3 is strongly dependent on T cell activation state, rendering naïve T cells primarily responsive to IL-6 and fully activated T cells more responsive to IL-10. These results overall conform to the directionality of IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα surface expression (Fig. 1), suggesting that the regulation of receptor surface expression with activation impacts signaling capacity and cytokine responsiveness. Variations in temporal sensitivity are overlaid on this and indicate the presence of additional controls.

STAT3 signal kinetics in response to IL-6 and IL-10

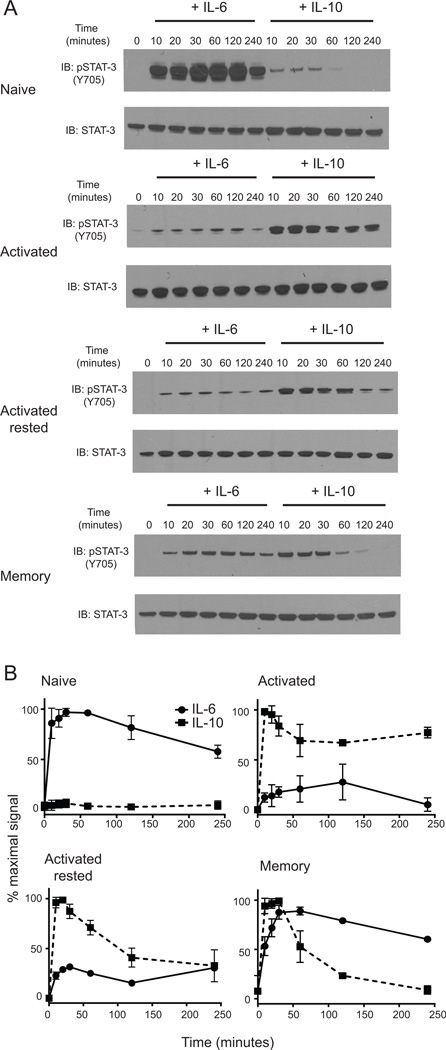

In macrophages, the pSTAT3 signal induced by IL-10 is prolonged compared with that induced by IL-6, and while both cytokines induce the negative regulator SOCS3, only IL-6Rα is subject to its regulation (22, 28). This has led to the concept that differential SOCS3 sensitivity restricts pSTAT3 signaling by IL-6 and distinguishes the pro- and anti-inflammatory effects of IL-6 and IL-10 respectively. To identify a similar pattern in T cells, we examined STAT3 phosphorylation kinetics in naïve, activated, activated-rested, and memory populations (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. STAT3 signaling kinetics in T cells stimulated with IL-6 or IL-10.

(A) Naïve, activated, activated-rested, or memory T cells were stimulated with IL-6 or IL-10 for the indicated time and pSTAT3 (Y705) and total STAT3 levels were assessed by Western blot. Blots are representative of at least 2 independent experiments. (B) Quantified blots were normalized to both total STAT3 levels and percent maximal signal. Plots represent data from at least 2 independent experiments where T cells were stimulated with IL-6 (•) or IL-10 (▪).

As above, naïve T cells were highly responsive to IL-6, but showed minimal STAT3 phosphorylation in response to IL-10. The pSTAT3 signal in response to IL-6 peaked after 30 minutes of stimulation, was sustained over 60 minutes and reduced to ~50% of maximum after 4 hours. Activated T cells responded weakly to IL-6, and this signal did not peak until later time points (60–120 minutes). In contrast, activated T cells responded strongly to IL-10, and reached maximal pSTAT3 levels after only 10 minutes. As with IL-6, this was sustained at about 75% of maximal signal through the 4 hour experimental time course (Fig. 3A and 3B).

Activated-rested T cells phosphorylated STAT3, although weakly (Fig. 2), in response to both IL-6 and IL-10. The magnitude was higher for IL-10, and both signals peaked within 20–30 minutes (Fig. 3). IL-10 induced pSTAT3 was reduced to 25% of the peak signal by 4 hours, while the IL-6 signal was sustained at near its maximum throughout the 4 hour time course. As in figure 2, memory T cells responded equivalently to IL-6 and IL-10 and these signals peaked at 20–30 minutes for both cytokines. However pSTAT3 induced by IL-10 was reduced to near basal levels after 4 hours, while the signal from IL-6 was maintained.

We further analyzed the induction of SOCS3 mRNA by IL-6 and IL-10 stimulation in naïve, activated, and memory T cells (Suppl. Fig. 2A–C). SOCS3 was upregulated in naive T cells in response to IL-6, and in memory T cells to IL-6 and IL-10, corresponding to overall signaling patterns and intensities. Interestingly, activated T cells did not demonstrate detectable cytokine-induced SOCS3 induction above basal levels, which were themselves diminished compared with those found in naïve or memory T cells (Suppl. Fig. 2C). Overall, these results indicate that the kinetics of pSTAT3 activation vary depending on T cell activation state. Contrasting with data from macrophages, the IL-10 induced pSTAT3 signal is attenuated more rapidly than that of IL-6 for naïve, activated-rested, and memory T cell populations and does not substantially differ from IL-6 in activated T cells. This implies that signal duration does not act in T cells as in macrophages to distinguish pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokine effects, and SOCS3’s role is distinct in these populations. Signal magnitude does differ markedly based on cytokine type in cells at a particular activation state.

STAT1 activation by IL-6 and IL-10 in T cell populations

In addition to STAT3, IL-10 has been shown to induce STAT1 and STAT5 phosphorylation in some macrophage cells lines (11, 12). We therefore investigated the phosphorylation of these additional STAT proteins in T cells. None of the assayed T cell populations induced pSTAT1 in response to IL-10 stimulation at doses ranging from 5 to 50 ng/ml and time points ranging from 5 minutes to 2 hours (Fig. 4A and data not shown). We also did not detect STAT5 phosphorylation in response to IL-10 in any T cell population under the same conditions (data not shown).

Figure 4. IL-6 induced STAT1 activation is not required for Th17 differentiation.

(A) Naïve, activated, activated-rested or memory T cells were stimulated with IL-6 or IL-10 as indicated for 20 minutes and pSTAT1 (Y701) and total STAT1 levels were assessed by western blot. Bar graph represents quantified data pooled from at least 2 independent experiments and normalized to percent of maximal pSTAT1 signal (naïve T cells stimulated with IL-6). (B) Sorted naïve T cells from STAT1 KO mice or B6 control mice were cultured under Th0 or Th17 differentiating conditions for 5 days, restimulated with PMA/ionomycin/brefeldin A, and stained for intracellular IL-17A. Dot plots and bar graph show percent of CD4+ gated IL-17A+ cells. Bar graph represents data pooled from 3 independent experiments each containing at least 3 mice per group.

Stimulation of naïve T cells with IL-6 induced a strong pSTAT1 response, consistent with previous findings (29). However, added IL-6 failed to promote significant STAT1 phosphorylation in activated, activated-rested, or memory T cells. Overall these data indicate differential STAT1 phosphorylation in response to IL-6 and IL-10. Further, the STAT1 and STAT3 responses to IL-6 are activation state dependent and uncoupled from each other, with only naïve cells sensitive to IL-6-induction of STAT-1 phosphorylation.

STAT1 activation by IL-6 is not required for Th17 differentiation

IL-6 driven Th17 formation requires STAT3 (30), and IL-10 cannot replace IL-6. The role of STAT1 in Th17 differentiation has not been directly determined, and differential STAT1 activation is one possible explanation for the disparate capabilities of these cytokines in this regard. To test this, naïve T cells from wild type or STAT1-deficient mice were cultured in Th0 or Th17 conditions. STAT1-deficiency did not significantly influence the level of Th17 cell induction (Fig. 4B). Therefore IL-6 induced phosphorylation of STAT1, in contrast to STAT3 (30), does not play a role in IL-6-mediated Th17 differentiation in-vitro.

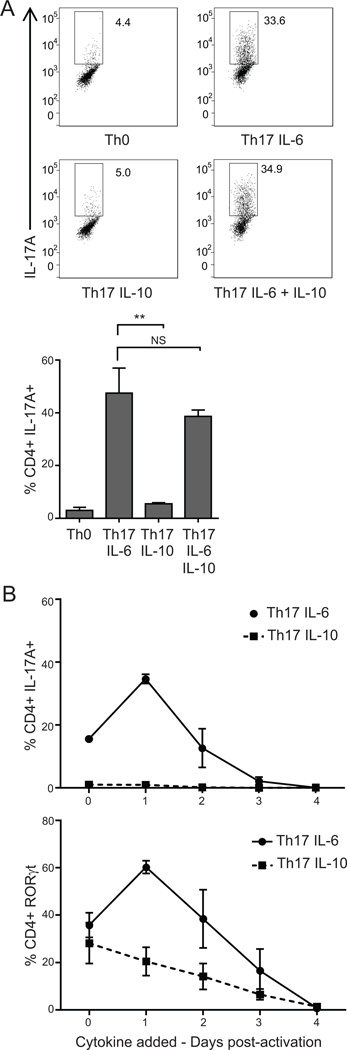

IL-10 does not impact Th17 differentiation in-vitro

To determine the effect of IL-10 on the in-vitro differentiation of Th17 cells, naïve T cells were cultured in Th0 conditions, Th17 conditions (Th17 IL-6), Th17 conditions in which IL-10 replaced IL-6 (Th17 IL-10), and Th17 conditions with both IL-6 and IL-10 (Th17 IL-6 + IL-10). As expected, IL-10 was unable to replace IL-6 as a source of the STAT3 signal needed for Th17 differentiation (Fig. 5A). In addition, IL-10 did not diminish the extent of Th17 differentiation. Thus while IL-10 has previously been reported to negatively influence the pathologic functions of Th17 cells in-vivo, it does not detectably alter Th17 differentiation itself.

Figure 5. IL-10 does not promote in-vitro Th17 differentiation.

(A) Sorted naïve T cells were cultured under Th0 conditions, Th17 conditions (Th17 IL-6), Th17 conditions in which IL-10 replaced IL-6 (Th17 IL-10), or Th17 conditions with both IL-6 and IL-10 (Th17 IL-6 + IL-10) for 5 days. Cells were restimulated with PMA/ionomycin/brefeldin A, and stained for intracellular IL-17A. Dot plots and bar graph show percent of CD4+ gated IL-17A+ cells. Bar graph represents data pooled from 3 independent experiments containing at least 3 mice per group. ** p≤ 0.01 (B) Sorted naïve T cells were activated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 and cytokines for either Th17 IL-6 conditions, or Th17 IL-10 conditions were added on the indicated day. Cells were harvested after 5 days, restimulated with PMA/ionomycin/brefeldin A and stained for intracellular IL-17A and RORγt.

Naïve T cells do not express appreciable levels of IL-10Rα, and pSTAT3 induced by IL-10 is minimal until day 2–3 after TCR activation. In contrast, pSTAT3 induced by IL-6 is greatest prior to this time (Fig. 1, 2). To assess the role of T cell activation state on IL-6 and IL-10 responsiveness during Th17 differentiation, naïve T cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/CD28 using Th17 IL-6 or Th17 IL-10 conditions except IL-6 or IL-10 were added at different time points after stimulation. Cultured cells were then analyzed for IL-17 and RORγt expression at day 5 (Fig. 5B). Under Th17 IL-6 conditions, Th17 differentiation was detectable with the addition of IL-6 up to 2 days post-TCR stimulation, with levels peaking with IL-6 addition at day 1. Beyond this time, Th17 differentiation was not detected. This is not surprising given the above observations that IL-6Rα levels and IL-6 induced pSTAT3 are markedly decreased by day two. Th17 IL-10 conditions were unable to generate IL-17 producing cells, even if cytokines were added several days after T cell activation when IL-10Rα levels are increased. Similar results were obtained for RORγt expression. However, RORγt was not as dependent on IL-6 as IL-17 production, reflecting the role of TGF-β in this transcription factor’s induction (31, 32). These analyses were replicated on cultures at days 7 and 9 post-TCR stimulation, but no differences in the induction patterns were seen at these later time points (data not shown). Thus IL-10 cannot support the pSTAT3 signaling required for in-vitro Th17 cell differentiation, even in pre-activated cells with high IL-10Rα receptor expression. IL-6, likewise, becomes ineffective at promoting Th17 differentiation in cells that have been previously activated. This indicates that naïve T cell susceptibility to Th17 conversion is temporally restricted to a period in which IL-10 STAT3 signaling is impaired.

Retrogenic expression of IL-10Rα on naïve T cells supports Th17 differentiation in response to IL-10

The above findings suggest that the failure of IL-10 to induce Th17 cells is a result of weak or absent IL-10Rα expression, and hence an inadequate IL-10 signal, during the window of sensitivity for Th17 differentiation. However, these data do not exclude possible qualitative differences in signaling between IL-10 and IL-6. To assess this, we transduced hematopoietic progenitor cells (HPCs) with retrovirus incorporating IL-10Rα and GFP or only GFP (vector control) driven by the MSCV LTR, and used these to generate retroviral transgenic (retrogenic) mice. CD4+ GFP+ T cells derived from HPCs transduced with IL-10Rα retrovirus displayed increased IL-10Rα surface expression relative to the non-transduced CD4+ GFP− cells in the same mice (Fig. 6A). Naïve CD4+ GFP+ and GFP− T cells were stimulated with IL-6 or IL-10, and assessed for pSTAT3 induction (Fig. 6B). Consistent with previous results (Fig. 2), naïve CD4+ GFP− T cells produced high levels of pSTAT3 when stimulated with IL-6, but not IL-10. GFP+ T cells from mice transduced with vector only showed similar results. In contrast, naïve CD4+ GFP+ T cells from the IL-10Rα retrogenics produced similarly high levels of pSTAT3 in response to either IL-10 or IL-6 (Fig. 6B). Thus naïve T cells are not intrinsically refractory to STAT3 phosphorylation in response to IL-10. Rather, inadequate IL-10Rα expression restricts IL-10 signaling.

Figure 6. IL10R expression on naive cells allows for in-vitro induction of Th17 cells via IL-10-derived pSTAT-3.

(A) Left: Splenocytes from IL-10Rα retrogenic mice gated on CD4+ GFP− and CD4+ GFP+. Right: IL-10Rα expression of CD4+ GFP− cells (shaded) and CD4+ GFP+ cells (heavy line). (B) CD4+ cells from spleen and lymph nodes of IL-10Rα and vector retrogenic mice were sorted based on GFP expression. Cells were stimulated with IL-6 or IL-10 for 20 minutes and pSTAT3 (Y705) and total STAT3 levels were assessed by western blot. Blot is representative of at least 2 independent experiments. (C) CD4+ cells from spleen and lymph nodes of IL-10Rα and vector retrogenic mice were sorted based on GFP expression and cultured under indicated conditions for 5 days, restimulated with PMA/ionomycin/brefeldin A, and stained for intracellular IL-17A. Dot plots (C) and bar graph (D) show percent of CD4+ gated IL-17A+ cells. Bar graph represents data pooled from 3 independent experiments containing at least 3 mice per group.

We next analyzed whether increased IL-10Rα expression on naïve T cells can support Th17 differentiation in response to IL-10. Naïve CD4+ GFP+ and CD4+ GFP− T cells were sorted from IL-10Rα retrogenic mice or control mice generated with vector-transduced HPCs. Cells were cultured in Th0 conditions, Th17 IL-6 conditions, or Th17 IL-10 conditions. As expected, little Th17 differentiation was observed for each of the T cell types in the absence of added cytokine and robust Th17 differentiation was seen in the presence of added IL-6. Likewise, GFP− cells from IL-10Rα retrogenic animals and GFP+ cells from vector-control mice were unable to generate Th17 cells when cultured with IL-10. In contrast, naïve GFP+ T cells from IL10Rα retrogenic mice efficiently generated IL-17+ cells (Fig. 6C and 6D); there was no significant difference in the percent of IL-17+ cells produced with IL-10 compared with IL-6 (Fig. 6D). Thus IL-10Rα expression on naïve T cells is sufficient to allow Th17 differentiation in response to IL-10.

While IL-17A is the primary cytokine associated with Th17 cells, other cytokines and transcription factors can also be expressed during Th17 cell development and contribute to their various inflammatory functions (33), and we therefore analyzed a panel of different markers. The Th17 cells generated from IL-10 and IL-6 did not show significantly different expression of Foxp3, IFN-γ, or IL-10 (Fig. 7A, C). Likewise, there was no difference in the percent of cells expressing the Th17 cytokine IL-17F (Fig. 7B, C). There was a decrease in the percent of cells co-expressing IL-17A and IL-22, though this was modest. Furthermore, Th17 surface markers IL-23R and CCR6 were also induced by both IL-6 and IL-10 to a similar degree (Figure 7D). Overall, these findings indicate that Th17 cells generated with IL-10 are highly comparable to those generated with IL-6.

Figure 7. Th17 cells derived from IL-6 and IL-10 are similar.

(A) CD4+ GFP+ cells from spleen and lymph nodes of IL-10Rα retrogenic mice were cultured under the indicated conditions for 5 days, restimulated with PMA/ionomycin/brefeldin A, and stained for intracellular cytokines and transcription factors. Plots are representative of two independent experiments with at least 3 mice per experiment. (B) Same as (A) except plots are gated on CD4+ IL-17A+ cells. (C) Bar graphs represent data pooled from 2 independent experiments containing at least 3 mice per group. ** p≤ 0.01. (D) Relative IL-23R and CCR6 expression of Th0 cells (shaded), Th17 IL-6 cells (solid line), and Th17 IL-10 cells (dotted line).

We next examined whether retrogenic IL-10Rα expressing naïve T cells would also be associated with preferential Th17 cell formation in-vivo. Naïve CD4+ GFP+ T cells from vector and IL-10Rα retrogenic mice were transferred into Rag1−/− recipients. IL-10 has been demonstrated to play a key role in intestinal homeostasis, and is widely expressed in the colon (34, 35). Spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes, and colons of recipient mice were isolated and assessed for numbers of CD4+ IL-17+ cells by flow cytometric analysis. Mice that received the IL-10Rα retrogenic cells had significantly more CD4+ IL-17+ cells in the colon, as compared to mice that received CD4+ GFP+ cells from vector-control retrogenic donors (Fig. 8A and 8B). A trend in the same direction was also observed in mesenteric lymph nodes and spleen, though was not significant. This suggests that IL-10Rα retrogenic cells are better able to form Th17 cells in-vivo.

Figure 8. High IL10Rα expression results in increased numbers of Th17 cells in a T cell transfer model.

(A) CD4+ CD45Rbhi GFP+ cells from vector or IL-10Rα retrogenic mice were injected into Rag 1 KO mice. Spleen, mesenteric lymph nodes (MLN) and colon of recipient mice were harvested 8 weeks later and stained for IL-17A. (B) Percent of CD4+ IL-17A+ cells (left) and CD4+ Foxp3+ cells (right) from spleen, MLN, and colons of recipient mice pooled from 2 independent experiments with at least 5 mice per group. * p≤ 0.05; *** p≤ 0.005. (C) T cell transfer colitis weight loss. Mice were weighed prior to the experiment and weight loss was monitored for 7 weeks post-transfer of either IL-10R GFP+ or vector GFP+ cells.

Interestingly, mice that received IL-10Rα GFP+ cells developed less severe colitis than mice that received vector GFP+ cells (Figure 8C). This may be explained by a significant increase in Foxp3+ regulatory T cells, which are protective in this model, in the mesenteric lymph node (Figure 8B). No difference in Th1 cell formation was observed (not shown). Thus, an enhanced Th17 conversion is observed in the retrogenic mice despite the diminished inflammatory disease. IL-10Rα GFP+ cells were more likely to convert to a regulatory phenotype, and the increase in this protective cell population likely accounts for the reduced severity of disease.

Retrogenic expression of IL-10Rα on naïve T cells supports IL-6-like effects on Th1/Th2 and Tfh differentiation in response to IL-10

While IL-6 is most notably involved in Th17 differentiation, it can also alter the Th1/Th2 balance by increasing T cell production of IL-4 and skewing effector cells toward a Th2 response (36, 37). We therefore assessed whether the presence of IL-10Rα on naïve T cells would enable IL-10 to replicate these effects of IL-6, as it did during Th17 differentiation. As expected, addition of IL-6 to Th0, Th1, or Th2 cultures significantly increased the amount of IL-4 producing cells in all cases (Supplemental Figure 3a). With increased Th2 formation, a reduction in the number of IFNγ producing cells was also observed. This decrease was most apparent under Th1 conditions, and thus we chose to use these conditions, whereby IL-6 enhanced Th2 and inhibited Th1 generation, for further experiments on IL-10Rα retrogenic cells (Supplemental Figure 3b). As with wild type T cells, addition of IL-6 during Th1 differentiation reduced the number of IFN-γ+ cells and increased the number of IL-4+ cells for both IL-10Rα GFP− and vector GFP− cells, as well as vector GFP+ cells. IL-10 had no effect on the Th1 cultures under normal circumstances where IL-10Rα is not expressed. However in the IL-10Rα GFP+ cells, IL-10 was able to replicate the effect of IL-6 on Th1/Th2 skewing, suppressing the production of IFNγ+ cells while enhancing IL-4+ cell formation (Figure 9A, Supplemental Figure 3b).

Figure 9. IL-10 replicates IL-6 mediated Th1/Th2 skewing and IL-21 expression in IL-10Rα expressing cells.

(A) CD4+ cells from spleens and lymph nodes of IL-10Rα and vector retrogenic mice were sorted based on GFP expression and cultured under the indicated conditions for 5 days, restimulated with PMA/ionomycin/brefeldin A, and stained for intracellular IFN-γ (top) and IL-4 (bottom). Graphs are representative of 3 or more independent experiments and normalized to the maximal percent of cytokine-expressing cells. (B) CD4+ cells from spleen and lymph nodes of IL-10Rα retrogenic mice were sorted based on GFP expression and cultured in the presence of irradiated APCs and anti-CD3 antibody with the indicated cytokines for 4 days. Media containing added cytokines was removed by washing and replaced with fresh media for 24 hours. Supernatants were assayed for IL-21 by ELISA. ** p≤ 0.01; *** p≤ 0.005; **** p≤ 0.0001.

Another functional role for IL-6 during T cell differentiation is promotion of Tfh cell differentiation and IL-21 production, either independently or in conjunction with IL-21. This pathway is active when IL-6 signals in the absence of TGF-β. We again utilized our retrogenic system to assess the ability of IL-10 to replicate this effect in the presence of IL-10Rα. As expected, both IL-6 and IL-21 induced IL-21 production under Tfh conditions, while IL-10 had no effect on IL-21 production by IL-10Rα GFP− cells. Conversely, treatment of IL-10Rα GFP+ cells with IL-10 induced IL-21 expression similar to that of IL-6 (Figure 9B). We also observed a significant increase in IL-21 production by IL-10Rα GFP+ over that of IL-10Rα GFP− cells in the presence of IL-21, which is likely due to the ability of IL-21 to induce IL-10 expression and a cumulative response of IL-10Rα GFP+ cells to both cytokines (38).

DISCUSSION

Identifying how a large numbers of cytokines with diverse biological effects differentially signal into cells through a restricted number of STAT proteins has been an ongoing challenge in cytokine biology. Many hematopoietic cell types respond to both IL-6 and IL-10, with pro- and anti-inflammatory effects respectively. The hallmarks of signaling and regulation of these cytokines have largely been established using macrophages and macrophage cell lines. Given that T cell differentiation and activation state can play an important role in cytokine responsiveness, we sought to determine the role of these processes on receptor level, cytokine signaling, and functional effect in T cells.

Previous data has indicated that T cell IL-6Rα levels are reduced after activation while IL-10Rα expression is increased (39, 40). We more fully define the regulation of cytokine receptors in CD4+ T cells here, further characterizing the modulation of their expression and the functional consequences of this. With activation, diminished IL-6Rα corresponds with a decline in the signal response to IL-6. Reciprocal expression and signaling are seen for IL-10. Memory T cells have moderate to high levels of IL-6Rα and IL-10Rα, and strong signals are observed to their respective cytokines. Thus in naïve CD4+ T cells undergoing activation and in memory T cells, responsiveness to IL-6 and IL-10 correlated well with surface receptor levels. Previously activated and then rested T cells exhibited receptor levels nearly equivalent to those of memory cells yet attenuated STAT3 activation to both cytokines, indicating the involvement of alternative regulatory mechanisms.

While we describe selective surface expression of IL-10 receptor as a means to regulate cytokine responsiveness and specificity, little is known about the regulatory mechanisms contributing to IL-10 receptor expression itself. IL-10 receptor is expressed on a wide variety of hematopoetic cells, although often at very low levels, and upregulated upon activation. IL-10 receptor can also be induced on other cell types by a variety of compounds, including LPS in fibroblasts (41) and glucocorticoids (42) and vitamin D3 (43) in epidermal cells. It also undergoes phosphorylation-dependent ubiquitinylation, endocytosis, and degradation as a means of signal attenuation (44). Further investigation of the factors that regulate the expression of IL-10 receptor on T cells in particular is of interest, given our results indicating that receptor expression is an important means of regulating cytokine receptivity.

Differential STAT homodimer and heterodimer formation has also been suggested to be a means by which cytokines that signal via shared STAT pathways can invoke distinct transcriptional programs (45). In addition to STAT3, IL-10 has been shown to activate STAT1 and STAT5 in macrophage cell lines. STAT1 phosphorylation can also be induced by IL-6 in T cells, although to a lesser extent than STAT3 (10–12, 46). We observed production of pSTAT1 with IL-6 stimulation in naïve CD4+ T cells alone, whereas neither pSTAT1 nor pSTAT5 were detected with IL-10 stimulation in any T cell population analyzed. Importantly, STAT1 phosphorylation was not required for Th17 induction, and therefore in regard to this critical developmental role of IL-6, differential STAT recruitment does not appear to distinguish IL-6 and IL-10. It is important to note that although we did not observe a difference in in-vitro Th17 differentiation in STAT1 deficient T cells, many studies have seen exaggerated Th17 phenotypes in STAT1 deficient mouse models, and individuals with STAT1 gain-of-function mutations often display defective Th17 responses. The mechanism that leads to impaired Th17 responses in these situations is not clear. For example, STAT1 signaling in patients with gain of function alleles also leads to enhanced responses to type 1 and type 2 interferons, which are inhibitors of Th17 cell development (47). In addition, STAT1 hyper-phosphorylation can lead to impaired IL-23 signaling, which can in turn result in defective Th17 T cell responses (48). Thus while STAT1 signaling can modulate Th17 responses, this may depend on the presence of additional cell types and cytokines in-vivo and so was not apparent in the in-vitro assays used here.

We also examined the kinetics of STAT3 phosphorylation, as the suppressive properties of IL-10 have been linked to sustained STAT3 phosphorylation in macrophages. Macrophages from Socs3-deficient mice have no defect in IL-10 signaling, and SOCS3 overexpression in monocytes does not negatively regulate IL-10 induced STAT3 activation, even at excessively high levels (18, 49). Indeed, constitutively active STAT3 is sufficient to transmit the cytokine suppressive activities of IL-10 in macrophages, and in the absence of SOCS3 IL-6 induces sustained STAT3 activation and an anti-inflammatory response similar to that mediated by IL-10 (28, 50). Microarray studies in human DCs showed that the transcriptional programs induced by IL-6 and IL-10 are similar at early time points and diverge later, when IL-10 signaling results in sustained STAT3 activation. As in macrophages, abrogating STAT3 activation after IL-10 stimulation in DCs results in an IL-6-like response (51). In contrast to myeloid cells, here we show that in T cells, IL-10 STAT3 signaling is actually attenuated more rapidly than that of IL-6. As a single exception, we did see a better sustained pSTAT3 signal in response to IL-10 than IL-6 in activated T cells at a 4 hr time point, but were unable to detect the induction of SOCS3 by either IL-6 or IL-10 in these cells. These findings indicate a distinct mechanism of regulation of these cytokines’ signaling in T cells compared with macrophages.

Other mediators have also been implicated in IL-10 and IL-6 regulation. IL-10 upregulates SOCS1, which may inhibit both IL-6 and IL-10 mediated STAT3 activation (52, 53). IL-10 may also have STAT-independent effects and has been shown to induce SOCS3 mRNA in the absence of STAT3 activation in human neutrophils (54). Finally, adenosine differentially regulates IL-10 and IL-6 induced STAT3 activation in M2c macrophages (55). While this study is focused on the roles of receptor expression in cytokine signaling, and pSTAT3 induction and kinetics, it does not preclude the simultaneous presence of these other regulatory mechanisms in T cells.

Several cytokines signal through STAT3 along with other STAT proteins. Although we did not identify differential signaling effects due to IL-6 and IL-10 phosphorylating alternative STATs with regards to T cell subset differentiation here, the pattern of STAT activation is important for other cytokine-mediated effects. For example, IL-21 and IL-27 signal through STAT3, but also induce STAT1 phosphorylation. A recent study found that the relative ratios of pSTAT3 to pSTAT1 were important in determining functional outcome, and that IL-27 can also induce Th17 differentiation in the absence of STAT1 signaling (56). Another recent study found that in the case of IL-6 and IL-27, STAT3 activation is responsible for the overall transcriptional program, while STAT1 expression helps control cytokine specificity (57). Thus while receptor expression may be an important regulator of cytokine specificity, a cytokine’s pattern of STAT activation will in circumstances play an important role in its functional effects. Supporting this, in preliminary analyses, we observed differential effects on memory cells of IL-6 and IL-10, neither of which activate STAT1 in this cell type (Fig. 4), versus IL-21, which activates STAT1 and STAT3, in modulating IL-2 and IL-17 production (data not shown).

Given our observation that naïve T cells do not express IL-10Rα and respond only weakly to IL-10, we used retrogenic mice to more directly investigate the role of receptor expression in STAT3 signaling. We found that naïve cells transduced with IL-10Rα can utilize IL-10 as effectively as IL-6 in supporting Th17 differentiation, skewing Th1/Th2, and inducing IL-21 expression. This result is notable in indicating that there is no functional difference in the STAT3 signal that is transduced by the receptors in response to IL-6 or IL-10. Rather, the critical difference in biological functions mediated by the cytokines reflects the differential regulation of the timing of receptor expression in response to T cell activation and subsequent receptor responsiveness.

We also found that constitutive T cell expression of IL-10R in a T cell transfer colitis model led to an increase in Th17 cells. Enhanced numbers of Foxp3+ Treg were also observed. Mice that received IL-10Rα GFP+ cells developed less severe disease, even in the presence of increased numbers of Th17 cells. The diminished disease is not surprising, as IL-10 signaling supports Treg activity, and Tregs are potent suppressors of Th17-mediated colitis (58). While the increased formation of Foxp3+ cells is an interesting result, it does preclude an independent analysis of the relative pathogenicity of the IL-10Rα+ and wild-type Th17 populations in this system. The development of systems to more definitively compare the in vivo pathogenicity of IL-10- and IL-6-induced Th17 cells will be important. In preliminary studies, we adoptively transferred myelin-oligodendroglial glycoprotein specific 2D2 TCR transgenic that were IL-10Rα-retrogenic and Th17-IL-10 differentiated into Rag1−/− mice to induce EAE. These cells showed equivalent presence in the CNS and disease pathogenicity as control non-IL-10Rα-retrogenic Th17-IL-6 or IL-10Rα-retrogenic Th17 IL-6 populations. However, all populations demonstrated a preponderance of IFN-γ producing CNS-infiltrating cells, and the relative impact of the Th17 and Th1 populations could not be ascertained through these analyses (data not shown).

It is somewhat surprising that we do not observe suppression of Th17 differentiation or IL-17 production in the presence of IL-10, given that IL-10 has been shown to suppress Th17 responses in-vivo (5). However our results do not preclude additional roles for IL-10 on APCs and costimulation that we would not observe in our studies. Several groups have looked at the effect of IL-10 on Th17 cells and IL-17 production in-vitro. One study found that while IL-10 can suppress IL-17 production, this inhibition was APC dependent and not observed when cells were stimulated with anti-CD3/anti-CD28 (59). Another study suggested that IL-10 can directly inhibit IL-17 production in-vitro, and that this effect was enhanced in the presence of APCs (60). It should be noted, however, that IL-23 was included in Th17 cultures in the latter study, and was omitted from the former study as well as our own.

In summary, our data indicate that timing of receptor expression and T cell activation status regulate IL-6-mediated Th17 differentiation and prevent similar responses to IL-10. Furthermore they indicate that, for Th17 differentiation, Th1/Th2 skewing, and Tfh production, the lack of IL-10Rα receptor expression alone, rather than a fundamental difference in the quality or kinetics of the STAT3 signal induced by IL-6 and IL-10, account for differences in cytokine signaling and responsiveness.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Richard Cross, Grieg Lennon and Parker Ingle for assistance with flow cytometry and flow cytometric sorting.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health Grant AI056153 and AI06600 (to TLG) and by ALSAC/SJCRH (to all authors).

REFERENCES

- 1.Murray PJ. Understanding and exploiting the endogenous interleukin-10/STAT3-mediated anti-inflammatory response. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2006;6:379–386. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2006.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lang R, Patel D, Morris JJ, Rutschman RL, Murray PJ. Shaping gene expression in activated and resting primary macrophages by IL-10. J Immunol. 2002;169:2253–2263. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.5.2253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiorentino DF, Zlotnik A, Mosmann TR, Howard M, O’Garra A. IL-10 inhibits cytokine production by activated macrophages. J Immunol. 1991;147:3815–3822. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.D’Andrea A, Aste-Amezaga M, Valiante NM, Ma X, Kubin M, Trinchieri G. Interleukin 10 (IL-10) inhibits human lymphocyte interferon gamma-production by suppressing natural killer cell stimulatory factor/IL-12 synthesis in accessory cells. J Exp Med. 1993;178:1041–1048. doi: 10.1084/jem.178.3.1041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huber S, Gagliani N, Esplugues E, O’Connor W, Jr, Huber FJ, Chaudhry A, Kamanaka M, Kobayashi Y, Booth CJ, Rudensky AY, Roncarolo MG, Battaglia M, Flavell RA. Th17 cells express interleukin-10 receptor and are controlled by Foxp3(−) and Foxp3+ regulatory CD4+ T cells in an interleukin-10-dependent manner. Immunity. 2011;34:554–565. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kotenko SV, Krause CD, Izotova LS, Pollack BP, Wu W, Pestka S. Identification and functional characterization of a second chain of the interleukin-10 receptor complex. EMBO J. 1997;16:5894–5903. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.19.5894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Liu Y, Wei SH, Ho AS, de Waal Malefyt R, Moore KW. Expression cloning and characterization of a human IL-10 receptor. J Immunol. 1994;152:1821–1819. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Donnelly RP, Sheikh F, Kotenko SV, Dickensheets H. The expanded family of class II cytokines that share the IL-10 receptor-2 (IL-10R2) chain. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:314–321. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0204117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams L, Bradley L, Smith A, Foxwell B. Signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 is the dominant mediator of the anti-inflammatory effects of IL-10 in human macrophages. J Immunol. 2004;172:567–576. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.1.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber-Nordt RM, Riley JK, Greenlund AC, Moore KW, Darnell JE, Schreiber RD. Stat3 recruitment by two distinct ligand-induced, tyrosine-phosphorylated docking sites in the interleukin-10 receptor intracellular domain. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:27954–27961. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Finbloom DS, Winestock KD. IL-10 induces the tyrosine phosphorylation of tyk2 and Jak1 and the differential assembly of STAT1 alpha and STAT3 complexes in human T cells and monocytes. J Immunol. 1995;155:1079–1090. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wehinger J, Gouilleux F, Groner B, Finke J, Mertelsmann R, Weber-Nordt RM. IL-10 induces DNA binding activity of three STAT proteins (Stat1, Stat3, and Stat5) and their distinct combinatorial assembly in the promoters of selected genes. FEBS Lett. 1996;394:365–370. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(96)00990-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kishimoto T. IL-6: from its discovery to clinical applications. Int Immunol. 2010;22:347–352. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bettelli E, Carrier Y, Gao W, Korn T, Strom TB, Oukka M, Weiner HL, Kuchroo VK. Reciprocal developmental pathways for the generation of pathogenic effector TH17 and regulatory T cells. Nature. 2006;441:235–238. doi: 10.1038/nature04753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Veldhoen M, Hocking RJ, Atkins CJ, Locksley RM, Stockinger B. TGFbeta in the context of an inflammatory cytokine milieu supports de novo differentiation of IL-17-producing T cells. Immunity. 2006;24:179–189. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Haan S, Hermanns HM, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F. Principles of interleukin (IL)-6-type cytokine signalling and its regulation. Biochem J. 2003;374:1–20. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Croker BA, Krebs DL, Zhang JG, Wormald S, Willson TA, Stanley EG, Robb L, Greenhalgh CJ, Forster I, Clausen BE, Nicola NA, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Roberts AW, Alexander WS. SOCS3 negatively regulates IL-6 signaling in vivo. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:540–545. doi: 10.1038/ni931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lang R, Pauleau AL, Parganas E, Takahashi Y, Mages J, Ihle JN, Rutschman R, Murray PJ. SOCS3 regulates the plasticity of gp130 signaling. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:546–550. doi: 10.1038/ni932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schmitz J, Weissenbach M, Haan S, Heinrich PC, Schaper F. SOCS3 exerts its inhibitory function on interleukin-6 signal transduction through the SHP2 recruitment site of gp130. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:12848–12856. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.17.12848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nicholson SE, De Souza D, Fabri LJ, Corbin J, Willson TA, Zhang JG, Silva A, Asimakis M, Farley A, Nash AD, Metcalf D, Hilton DJ, Nicola NA, Baca M. Suppressor of cytokine signaling-3 preferentially binds to the SHP-2-binding site on the shared cytokine receptor subunit gp130. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6493–6498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.100135197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams L, Jarai G, Smith A, Finan P. IL-10 expression profiling in human monocytes. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:800–809. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Niemand C, Nimmesgern A, Haan S, Fischer P, Schaper F, Rossaint R, Heinrich PC, Muller-Newen G. Activation of STAT3 by IL-6 and IL-10 in primary human macrophages is differentially modulated by suppressor of cytokine signaling 3. J Immunol. 2003;170:3263–3272. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.6.3263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubtsov YP, Rasmussen JP, Chi EY, Fontenot J, Castelli L, Ye X, Treuting P, Siewe L, Roers A, Henderson WR, Jr, Muller W, Rudensky AY. Regulatory T cell-derived interleukin-10 limits inflammation at environmental interfaces. Immunity. 2008;28:546–558. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pappu BP, Dong C. Measurement of interleukin-17. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/0471142735.im0625s79. Chapter 6: Unit 6 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bettini ML, Bettini M, Nakayama M, Guy CS, Vignali DA. Generation of T cell receptor-retrogenic mice: improved retroviral-mediated stem cell gene transfer. Nat Protoc. 2013;8:1837–1840. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holst J, Szymczak-Workman AL, Vignali KM, Burton AR, Workman CJ, Vignali DA. Generation of T-cell receptor retrogenic mice. Nat Protoc. 2006;1:406–417. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2006.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li B, Alli R, Vogel P, Geiger TL. IL-10 modulates DSS-induced colitis through a macrophage-ROS-NO axis. Mucosal Immunol. 2014;7:869–878. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Williams LM, Sarma U, Willets K, Smallie T, Brennan F, Foxwell BM. Expression of constitutively active STAT3 can replicate the cytokine-suppressive activity of interleukin-10 in human primary macrophages. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:6965–6975. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M609101200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Choi YS, Eto D, Yang JA, Lao C, Crotty S. Cutting edge: STAT1 is required for IL-6-mediated Bcl6 induction for early follicular helper cell differentiation. J Immunol. 2013;190:3049–3053. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang XO, Panopoulos AD, Nurieva R, Chang SH, Wang D, Watowich SS, Dong C. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9358–9363. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hebel K, Rudolph M, Kosak B, Chang HD, Butzmann J, Brunner-Weinzierl MC. IL-1beta and TGF-beta act antagonistically in induction and differentially in propagation of human proinflammatory precursor CD4+ T cells. J Immunol. 2011;187:5627–5235. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1003998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Rutz S, Noubade R, Eidenschenk C, Ota N, Zeng W, Zheng Y, Hackney J, Ding J, Singh H, Ouyang W. Transcription factor c-Maf mediates the TGF-beta-dependent suppression of IL-22 production in T(H)17 cells. Nat Immunol. 2011;12:1238–1245. doi: 10.1038/ni.2134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murai M, Turovskaya O, Kim G, Madan R, Karp CL, Cheroutre H, Kronenberg M. Interleukin 10 acts on regulatory T cells to maintain expression of the transcription factor Foxp3 and suppressive function in mice with colitis. Nat Immunol. 2009;10:1178–1184. doi: 10.1038/ni.1791. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Feagins LA. Role of transforming growth factor-beta in inflammatory bowel disease and colitis-associated colon cancer. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:1963–1968. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Dienz O, Rincon M. The effects of IL-6 on CD4 T cell responses. Clin Immunol. 2009;130:27–33. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rincon M, Anguita J, Nakamura T, Fikrig E, Flavell RA. Interleukin (IL)-6 directs the differentiation of IL-4-producing CD4+ T cells. J Exp Med. 1997;185:461–469. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Spolski R, Kim HP, Zhu W, Levy DE, Leonard WJ. IL-21 mediates suppressive effects via its induction of IL-10. J Immunol. 2009;182:2859–2867. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0802978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ye Z, Huang H, Hao S, Xu S, Yu H, Van Den Hurk S, Xiang J. IL-10 has a distinct immunoregulatory effect on naive and active T cell subsets. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2007;27:1031–1038. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.0144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Betz UA, Muller W. Regulated expression of gp130 and IL-6 receptor alpha chain in T cell maturation and activation. Int Immunol. 1998;10:1175–1184. doi: 10.1093/intimm/10.8.1175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Weber-Nordt RM, Meraz MA, Schreiber RD. Lipopolysaccharide-dependent induction of IL-10 receptor expression on murine fibroblasts. J Immunol. 1994;153:3734–3744. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Michel G, Mirmohammadsadegh A, Olasz E, Jarzebska-Deussen B, Muschen A, Kemeny L, Abts HF, Ruzicka T. Demonstration and functional analysis of IL-10 receptors in human epidermal cells: decreased expression in psoriatic skin, down-modulation by IL-8, and up-regulation by an antipsoriatic glucocorticosteroid in normal cultured keratinocytes. J Immunol. 1997;159:6291–6297. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Michel G, Gailis A, Jarzebska-Deussen B, Muschen A, Mirmohammadsadegh A, Ruzicka T. 1,25-(OH)2-vitamin D3 and calcipotriol induce IL-10 receptor gene expression in human epidermal cells. Inflamm Res. 1997;46:32–34. doi: 10.1007/s000110050042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jiang H, Lu Y, Yuan L, Liu J. Regulation of interleukin-10 receptor ubiquitination and stability by beta-TrCP-containing ubiquitin E3 ligase. PLoS One. 2011;6:e27464. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0027464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Delgoffe GM, Vignali DA. STAT heterodimers in immunity: A mixed message or a unique signal? JAKSTAT. 2013;2:e23060. doi: 10.4161/jkst.23060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Heinrich PC, Behrmann I, Muller-Newen G, Schaper F, Graeve L. Interleukin-6-type cytokine signalling through the gp130/Jak/STAT pathway. Biochem J. 1998;334(Pt 2):297–314. doi: 10.1042/bj3340297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu L, Okada S, Kong XF, Kreins AY, Cypowyj S, Abhyankar A, Toubiana J, Itan Y, Audry M, Nitschke P, Masson C, Toth B, Flatot J, Migaud M, Chrabieh M, Kochetkov T, Bolze A, Borghesi A, Toulon A, Hiller J, Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Gulacsy V, Chernyshova L, Chernyshov V, Bondarenko A, Grimaldo RM, Blancas-Galicia L, Beas IM, Roesler J, Magdorf K, Engelhard D, Thumerelle C, Burgel PR, Hoernes M, Drexel B, Seger R, Kusuma T, Jansson AF, Sawalle-Belohradsky J, Belohradsky B, Jouanguy E, Bustamante J, Bue M, Karin N, Wildbaum G, Bodemer C, Lortholary O, Fischer A, Blanche S, Al-Muhsen S, Reichenbach J, Kobayashi M, Rosales FE, Lozano CT, Kilic SS, Oleastro M, Etzioni A, Traidl-Hoffmann C, Renner ED, Abel L, Picard C, Marodi L, Boisson-Dupuis S, Puel A, Casanova JL. Gain-of-function human STAT1 mutations impair IL-17 immunity and underlie chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1635–1648. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smeekens SP, Plantinga TS, van de Veerdonk FL, Heinhuis B, Hoischen A, Joosten LA, Arkwright PD, Gennery A, Kullberg BJ, Veltman JA, Lilic D, van der Meer JW, Netea MG. STAT1 hyperphosphorylation and defective IL12R/IL23R signaling underlie defective immunity in autosomal dominant chronic mucocutaneous candidiasis. PLoS One. 2011;6:e29248. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Prele CM, Keith-Magee AL, Yerkovich ST, Murcha M, Hart PH. Suppressor of cytokine signalling-3 at pathological levels does not regulate lipopolysaccharide or interleukin-10 control of tumour necrosis factor-alpha production by human monocytes. Immunology. 2006;119:8–17. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2006.02383.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yasukawa H, Ohishi M, Mori H, Murakami M, Chinen T, Aki D, Hanada T, Takeda K, Akira S, Hoshijima M, Hirano T, Chien KR, Yoshimura A. IL-6 induces an anti-inflammatory response in the absence of SOCS3 in macrophages. Nat Immunol. 2003;4:551–556. doi: 10.1038/ni938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Braun DA, Fribourg M, Sealfon SC. Cytokine response is determined by duration of receptor and signal transducers and activators of transcription 3 (STAT3) activation. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:2986–2993. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.386573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Chen XP, Losman JA, Rothman P. SOCS proteins, regulators of intracellular signaling. Immunity. 2000;13:287–290. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)00028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Ding Y, Chen D, Tarcsafalvi A, Su R, Qin L, Bromberg JS. Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 inhibits IL-10-mediated immune responses. J Immunol. 2003;170:1383–1391. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.170.3.1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cassatella MA, Gasperini S, Bovolenta C, Calzetti F, Vollebregt M, Scapini P, Marchi M, Suzuki R, Suzuki A, Yoshimura A. Interleukin-10 (IL-10) selectively enhances CIS3/SOCS3 mRNA expression in human neutrophils: evidence for an IL-10-induced pathway that is independent of STAT protein activation. Blood. 1999;94:2880–2889. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Koscso B, Csoka B, Kokai E, Nemeth ZH, Pacher P, Virag L, Leibovich SJ, Hasko G. Adenosine augments IL-10-induced STAT3 signaling in M2c macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2013;94:1309–1315. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0113043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Peters A, Fowler KD, Chalmin F, Merkler D, Kuchroo VK, Pot C. IL-27 Induces Th17 Differentiation in the Absence of STAT1 Signaling. J Immunol. 2015;195:4144–4153. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1302246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hirahara K, Onodera A, Villarino AV, Bonelli M, Sciume G, Laurence A, Sun HW, Brooks SR, Vahedi G, Shih HY, Gutierrez-Cruz G, Iwata S, Suzuki R, Mikami Y, Okamoto Y, Nakayama T, Holland SM, Hunter CA, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ. Asymmetric Action of STAT Transcription Factors Drives Transcriptional Outputs and Cytokine Specificity. Immunity. 2015;42:877–889. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2015.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chaudhry A, Samstein RM, Treuting P, Liang Y, Pils MC, Heinrich JM, Jack RS, Wunderlich FT, Bruning JC, Muller W, Rudensky AY. Interleukin-10 signaling in regulatory T cells is required for suppression of Th17 cell-mediated inflammation. Immunity. 2011;34:566–578. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Naundorf S, Schroder M, Hoflich C, Suman N, Volk HD, Grutz G. IL-10 interferes directly with TCR-induced IFN-gamma but not IL-17 production in memory T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1066–1077. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Gu Y, Yang J, Ouyang X, Liu W, Li H, Yang J, Bromberg J, Chen SH, Mayer L, Unkeless JC, Xiong H. Interleukin 10 suppresses Th17 cytokines secreted by macrophages and T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1807–1813. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.